Summary

Herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) causes lifelong recurrent pathologies without a cure. How infection by HSV-1 triggers disease processes, especially in the immune-privileged avascular human cornea, remains a major unresolved puzzle. It has been speculated that a cornea-resident molecule must tip the balance in favor of pro-inflammatory and pro-angiogenic conditions observed with herpetic as well as non-herpetic ailments of the cornea. Here, we demonstrate that heparanase (HPSE), a host enzyme, is the molecular trigger for multiple pathologies associated with HSV-1 infection. In human corneal epithelial cells, HSV-1 infection upregulates HPSE in a manner dependent on HSV-1 infected cell protein 34.5. HPSE then relocates to the nucleus to regulate cytokine production, inhibits wound closure, enhances viral spread, and thus generates a toxic local environment. Overall, our findings implicate activated HPSE as a driver of viral pathogenesis, and call for further attention to this host protein in infection and other inflammatory disorders.

Keywords: cornea, cytokines, heparan sulfate, heparanase, herpes simplex virus, inflammation, interferon, ophthalmology, transcription factors, wound healing

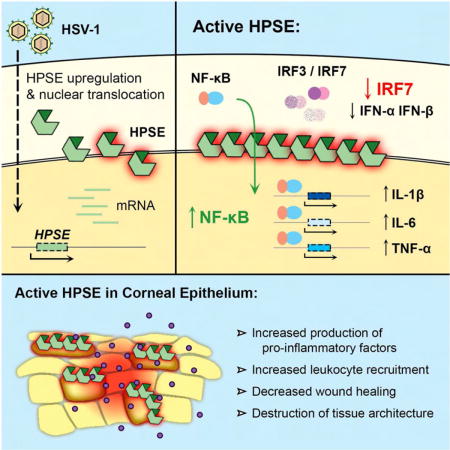

Graphical abstract

Agelidis et al. demonstrate that herpes simplex virus type-1 (HSV-1) infection activates the host protein heparanase (HPSE), which drives key processes in herpes pathogenesis. These results shed light on the mechanisms by which HSV-1 disrupts homeostasis and breaks immune tolerance in the case of the human cornea.

Introduction

Heparanase (HPSE) is an endoglycosidase with the unique ability of degrading heparan sulfate (HS), an evolutionarily conserved glycosaminoglycan present ubiquitously at the cell surface and extracellular matrix (ECM) of a wide range of cell types. HPSE catalyzes cleavage of the β-(1,4)-glycosidic bond between glucuronic acid and glucosamine residues of HS, and thus through ECM remodeling is involved in several important biological functions (Vlodavsky and Friedmann, 2001; Goldberg et al., 2013; Xu and Esko, 2014). While HS is known to be an important attachment receptor for a wide variety of human pathogens (Aquino et al., 2010; Tiwari et al., 2012; Park and Shukla, 2013), very little understanding exists on the significance of host-encoded HPSE in infection. We recently reported that host-encoded HPSE is upregulated upon infection by multiple herpesviruses, and facilitates release of viral progeny from parent cells after herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection (Hadigal et al., 2015). Herpesviruses are among the most prevalent human infections worldwide, with an estimated 90 percent of individuals worldwide infected with HSV-1 or -2 (Farooq and Shukla, 2012). HSV-1, a prototypic DNA virus, enters cells via multiple well-characterized receptors (Agelidis and Shukla, 2015), and is known to cause distressing infection of the human cornea, with HSV keratitis as the leading cause of infectious blindness in developed nations (Farooq and Shukla, 2012). Current therapies, including acyclovir and its analogs, are limited by their inability to prevent permanent establishment of viral latency and reactivation of clinical disease later in life (Remeijer et al., 2004). Infection of the corneal epithelium by HSV can trigger keratitis, which often continues to progress even long after the infection has subsided, suggesting that local yet poorly understood innate host factors can provide the signals necessary for continued inflammation and influx of pro-inflammatory cells in the immune privileged cornea. ECM damage is thought to be important in the induction of pro-inflammatory conditions in the cornea, but HPSE has never been directly implicated (Carlson et al., 2010). An understanding of innate host factors that directly contribute to this blinding disease and other inflammatory disorders is critical for developing new and more effective interventions against HSV-driven tissue damage and disease development (Hendricks and Tumpey, 1990; Knickelbein et al., 2010). In this work, we show that active HPSE translocates to the nucleus upon HSV infection, regulates transcription of key host molecules and initiates several signaling programs that are unfavorable to the host, and is thus an important driver of pathologies seen with HSV-1 infection.

Results and Discussion

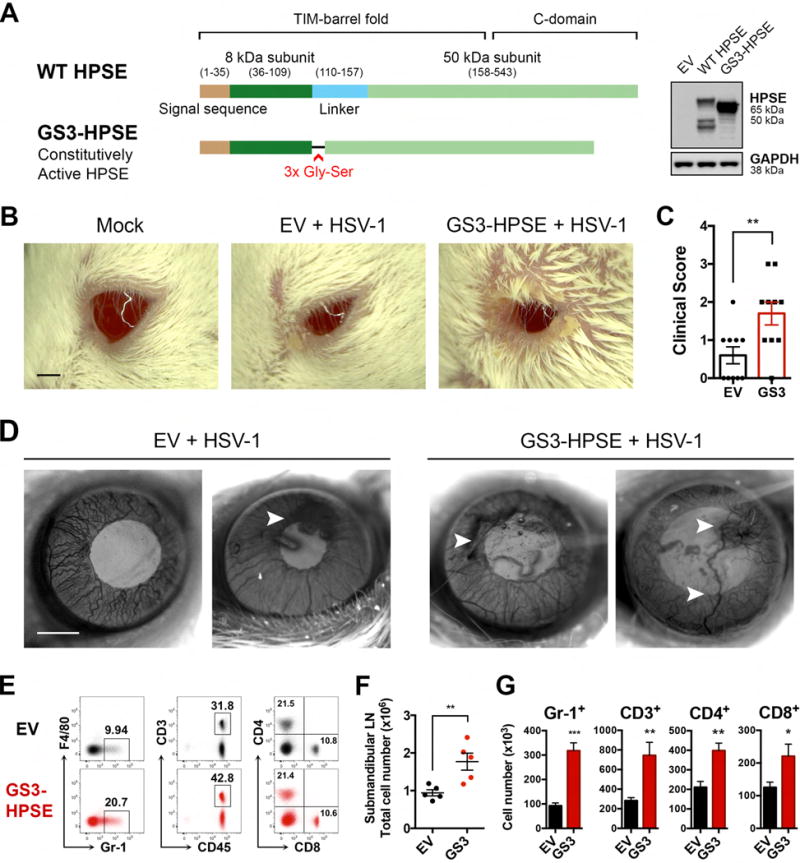

Overexpression of HPSE worsens herpetic disease in corneal infection in vivo

With our discovery that HPSE is upregulated and activated in corneal HSV infection (Hadigal et al., 2015), we sought to understand what roles enzymatically active HPSE could have in promoting ocular pathogenesis. Because of the complex nature of HPSE biogenesis and activation, we took advantage of an expression construct encoding constitutively active HPSE (GS3-HPSE) to more directly investigate the functions of this enzyme (Figure 1A, Figure S1) (Fux et al., 2009). Our initial observation that corneal overexpression of active GS3-HPSE worsens herpetic disease in vivo is shown in Figure 1. GS3-HPSE transfected mice displayed increased periorbital edema and erythema, as well as increased ocular discharge, all signs of worse herpetic disease reflected in the higher clinical scores (Figure 1B,C). An independent experiment with a different HSV-1 strain showed markedly increased ulcer formation and angiogenesis at 14 dpi in mice corneas transfected with GS3-HPSE (Figure 1D). Furthermore, flow cytometry analysis showed that ipsilateral draining lymph nodes (DLNs) of GS3-HPSE transfected mice contained significantly increased numbers of total cells after infection, indicating a heightened inflammatory response (Figure 1E–G). GS3-HPSE transfected mice DLNs also displayed increased proportions (and thus increased absolute numbers) of Gr-1+ neutrophils and CD3+ T cells. Absolute numbers of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were also significantly increased, although proportions of these cells remained similar. Flow gating strategies and efficiency of corneal transfection are displayed in Figure S2. HS involvement in migration of neutrophils and other immune cells has been documented previously (Wang et al., 2005; Parish, 2006), but HPSE has never been directly implicated in the context of infection. Together these findings indicate that aberrant HPSE expression in the cornea is a virally exploited innate trigger that drives worsened pathological responses to ocular infection.

Figure 1. Overexpression of constitutively active HPSE worsens disease in corneal HSV-1 infection.

A, Schematic showing GS3-HPSE expression variant, in which the linker of the inactive 65-kDa form is replaced with a triple repeat of Gly-Ser to produce a constitutively active HPSE. Protein expression confirmed in HCE cell line with anti-HPSE PT-16673. B, Representative micrographs of mice 7 days post HSV-1 (McKrae 106 pfu) corneal infection. Scale bar, 1 mm. C, Clinical scores based on corneal opacity of mice in B. D, Representative micrographs of corneal surface of mice 14 days post HSV-1 (KOS 106 pfu) corneal infection. Scale bar, 1 mm. E–G, Analysis of ipsilateral draining (submandibular) lymph nodes of mice 7 days post HSV-1 (McKrae) infection. E, Representative flow cytometry data showing surface staining of F4/80 vs Gr-1, CD3 vs CD45, and CD4 vs CD8. Percentages of parent gates are labeled on each plot. F, Total numbers of cells in each mouse lymph node. G, Numbers of each cell type present in the draining lymph node. Asterisks denote a significant difference as determined by Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant. See also Figure S1, S2, S6.

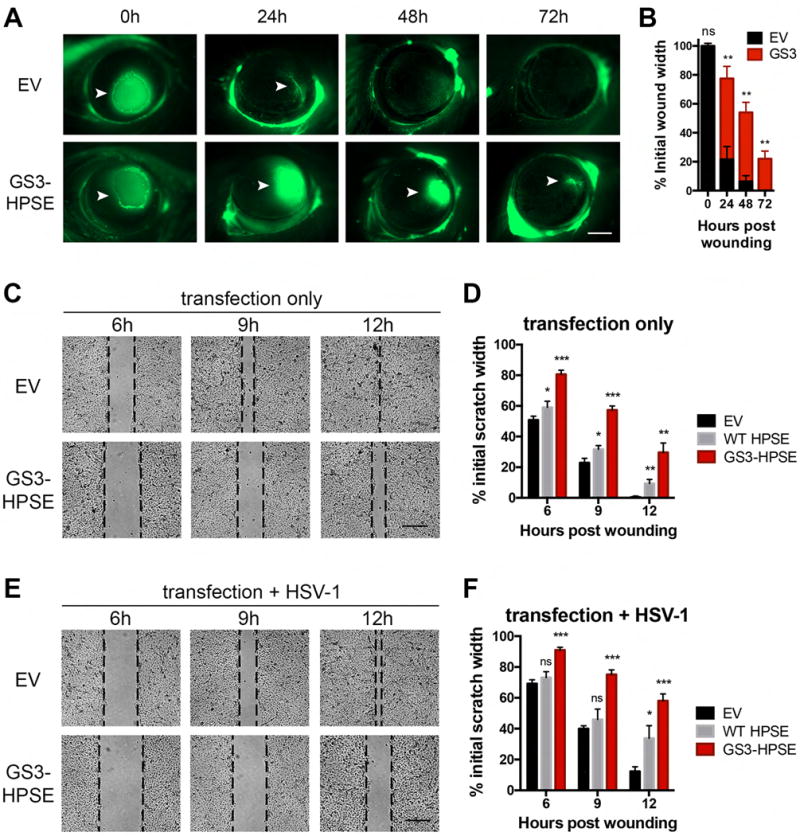

Wound healing is defective in presence of active HPSE

Exacerbated ulcer and blood vessel development are key symptoms of advanced herpetic keratitis and numerous other inflammatory pathologies, possibly due in part to defects in the process of wound healing (Remeijer et al., 2004). We therefore performed an in vivo corneal wound healing assay to further address this aspect of herpetic disease. GS3-HPSE overexpression in the absence of infection prevented proper closure of a circular defect introduced in the corneal epithelium (Figure 2A,B). Along similar lines, in an in vitro scratch assay, HPSE delayed wound healing of monolayers of human corneal epithelial (HCE) (Figure 2C–F) and HeLa cells (Figure S3A,B). Similar findings were observed in the absence and presence of HSV-1, with infection causing a further delay in wound healing. Additional support comes from recent work showing that genetic depletion of heparan sulfate caused impaired corneal wound healing in mice (Coulson-Thomas et al., 2015). As such, our observations indicate that HPSE has a previously unknown role in epithelial cell migration and corneal pathology.

Figure 2. Active HPSE delays corneal wound healing in vivo and in vitro.

A, Representative micrographs of in vivo corneal wound healing assay in murine corneas previously transfected with the GS3-HPSE or empty vector, in absence of infection. At specified timepoints post application of the circular wound, fluorescein was applied to highlight tissue damage (arrowheads), and corneas were imaged. Scale bar, 1 mm. B, Mean ± SEM of extent of wound healing in A. C, Representative micrographs of in vitro wound healing assay showing closure of HCE cellular defect over specified times after scratching. Before wound application, cells were transfected with empty vector, WT HPSE (not depicted) or GS3-HPSE. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, Quantification of extent of wound healing in D. Pixel distances between wound fronts in each panel were measured, and percentages of initial wound widths are plotted. E–F, The same procedure described in C and D was performed with the exception that HCE cells were infected with HSV-1 (KOS MOI 0.1) at the time of wound application. Asterisks denote a significant difference as determined by Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant. See also Figure S3.

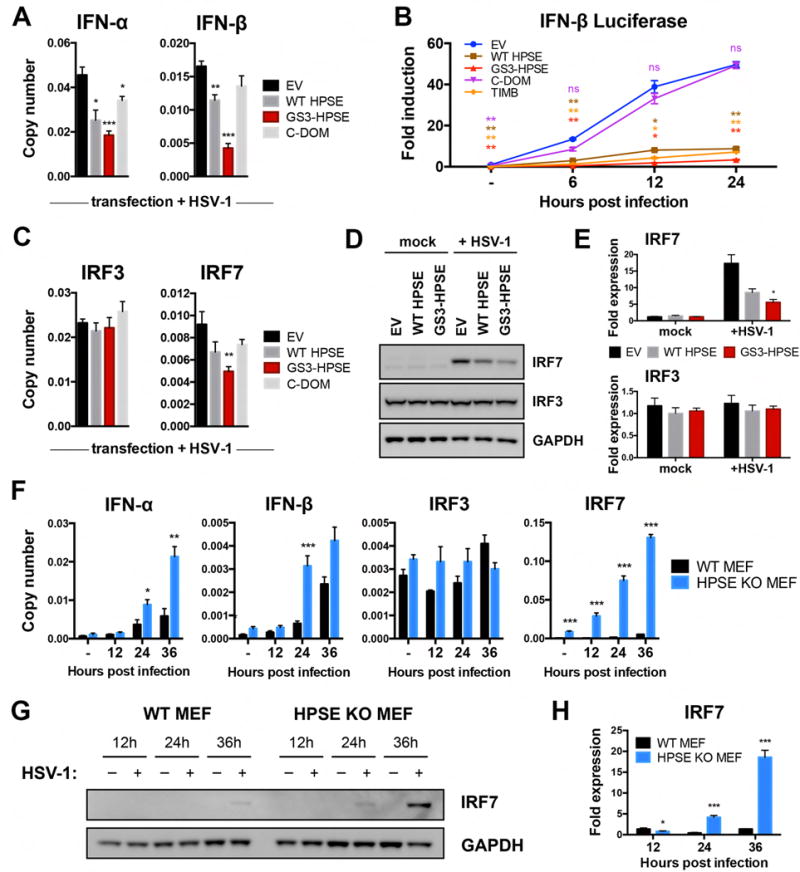

Active HPSE dampens type I interferon responses

As another hallmark of herpetic disease is dysregulation of cytokine production (Remeijer et al., 2004; Kaye and Choudhary, 2006; Knickelbein et al., 2010), we investigated whether HPSE is involved in this process as well. We found in HCE cells that overexpression of WT HPSE and GS3-HPSE produced significantly reduced type I interferon responses to HSV-1 infection, with this effect being greatest in GS3-HPSE overexpressing cells (Figure 3A). Additionally, cells overexpressing the C-terminal domain HPSE mutant produced a partial rescue, supporting a role for active HPSE in regulation of interferon production and suggesting a localization of this signaling inhibition to the TIM-barrel domain (Figure S1). A TIM-barrel variant of HPSE was previously shown to lack HS-degrading activity (Fux et al., 2009), therefore it appears that the suppressive effect of the TIM-barrel domain on interferon signaling is due to some non-enzymatic activity of HPSE. Interferon (IFN)-α and -β are known to initiate antiviral signaling pathways in neighboring cells and prevent spread of infection (Levy et al., 2011), so decreased interferon expression in the context of active HPSE is consistent with our in vivo findings. These results were further confirmed with time course luciferase assays in HCE cells (Figure 3B) and HeLa cells (Figure S3C) in which plasmids containing the IFN-β promoter region fused to luciferase gene were co-transfected with the aforementioned HPSE plasmids. Given these findings, we probed further into the mechanism of this regulation by focusing on interferon regulatory factors (IRFs)-3 and -7, the two major transcription factors responsible for type I interferon stimulation. Our results suggest that active HPSE dampens interferon responses through transcriptional suppression of IRF7 mRNA, resulting in a corresponding decrease in IRF7 protein produced with infection (Figure 3C–E). In contrast, IRF3 mRNA and protein were not significantly altered by HPSE expression. In HPSE-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (HPSE KO MEFs) (Zcharia et al., 2009), we observed significantly increased IFN-α and IFN-β production, further verifying that HPSE has a role in regulation of type I interferon responses (Figure 3F). Furthermore, IRF7 mRNA and protein production were dramatically increased in HPSE KO MEFs, complementing the finding of the previous overexpression assays. Future work will aim to characterize the nature of the interaction between HPSE and IRF7, as this previously unknown association may have important consequences in host responses to infection.

Figure 3. HPSE inhibits type I interferon signaling.

A, Transcript copy numbers relative to GAPDH from HCE cells transfected with specified HPSE variants and HSV-1 infected. B, Luciferase assay results from HCE cells co-transfected with HPSE variants and pIFNb-luc, and infected for specified timepoints. C, Transcript copy numbers relative to GAPDH obtained as described in A. D, Representative western blot analysis of whole cell lysates of HCE cells transfected with specified HPSE variants in absence or presence of HSV-1. E, Densitometry analysis of D. F, Transcript copy numbers relative to GAPDH from wildtype and HPSE-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts in the absence or presence of HSV-1 for specified timepoints. G, Representative western blot analysis of whole cell lysates of wildtype and HPSE-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts in absence or presence of HSV-1 for specified timepoints. H, Densitometry analysis of G. All results are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n=3). Asterisks denote a significant difference compared to EV, or WT MEF where applicable, for each timepoint, as determined by Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant. See also Figure S3, S6.

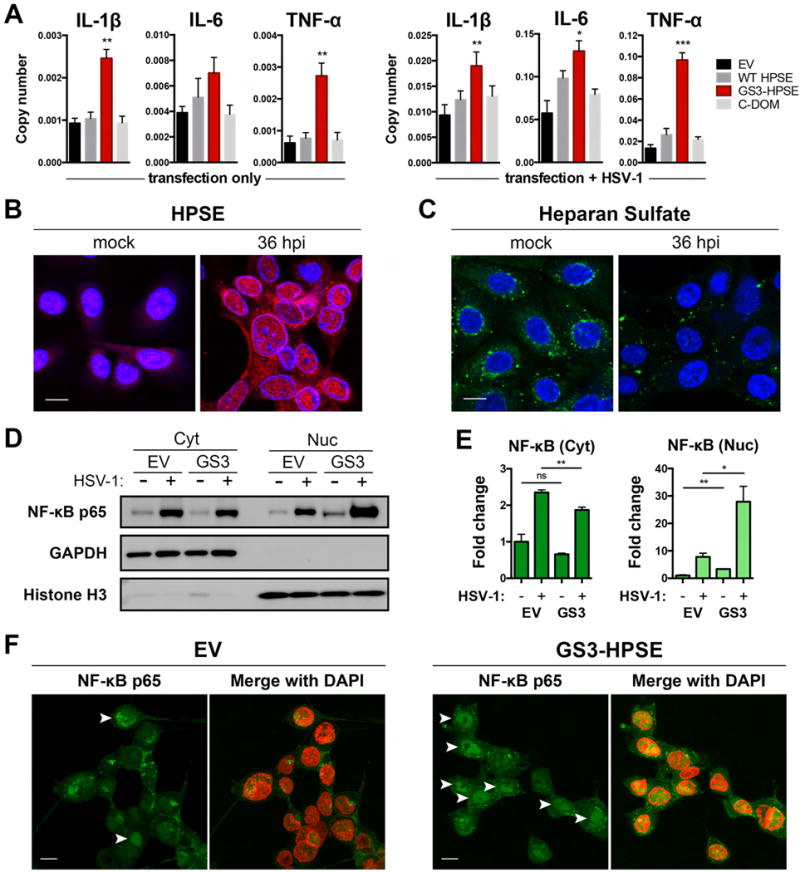

Active HPSE increases pro-inflammatory signaling in corneal cells through enhancement of NF-κB nuclear translocation

Given known roles of HPSE in promotion of inflammation in other systems (Vlodavsky and Friedmann, 2001; Goldberg et al., 2013), we sought to understand whether HPSE alters pro-inflammatory factor production in the context of corneal infection. We found in HCE cells that overexpression of GS3-HPSE increased interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α mRNA responses to HSV-1 infection, with this effect being greatest for TNF-α (Figure 4A). Of note, GS3-HPSE overexpression also caused significant increases in IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA production even in the absence of infection. WT HPSE overexpression trended toward higher production of these cytokines but no significant differences were observed. In our search to elucidate the cytokine regulatory functions of HPSE, we repeatedly observed that HPSE is upregulated in the nucleus and at the nuclear rim upon HSV-1 infection (Figure 4B). A corresponding decrease in nuclear heparan sulfate further confirms this observation (Figure 4C). Bearing in mind previous suggestions of the ability of HPSE to localize to the nucleus (Schubert et al., 2004; Nobuhisa et al., 2007), bind to DNA (Yang et al., 2015), and regulate chromatin modifications (He et al., 2012; Hong et al., 2012), we hypothesized that HPSE influences cytokine signaling by interaction with transcription factors. Indeed, western blot analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from HCE cells (Figure 4D,E) and HeLa cells (Figure S3D) overexpressing GS3-HPSE showed significantly enhanced translocation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB to the nucleus upon infection. Additionally, we found by immunofluorescence microscopy that HCE cells overexpressing GS3-HPSE showed enhanced NF-κB nuclear translocation (Figure 4F). Interestingly, our previous work showed that one mechanism by which HSV-1 upregulates HPSE is through NF-κB activation (Hadigal et al., 2015). Together with the observation here that HPSE influences NF-κB translocation, these studies are consistent with the notion that these two proteins act in a positive feedback loop (Goldberg et al., 2013), which remains to be fully understood.

Figure 4. HPSE translocates to nucleus upon infection and drives pro-inflammatory factor production and nuclear translocation of NF-κB.

A, Transcript copy numbers of HCE cells transfected with specified HPSE variants, or transfected and HSV-1 infected for 24 h. B–C, Representative immunofluorescence micrographs of HCE cells mock treated or HSV-1 infected for 36 h. B, HPSE (red) and C, Heparan sulfate (green) are shown with respect to DAPI stain of nucleus (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm. D, Representative western blot analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of HCE cells transfected with empty vector or GS3-HPSE. GAPDH and Histone H3 reflect cytoplasmic and nuclear content, respectively. E, Densitometry analysis expressed as fold change compared to EV mock samples, mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n=3). F, Representative immunofluorescence micrographs of HCE cells transfected with empty vector or GS3-HPSE and HSV-1 infected for 24h. Nuclear translocation (arrowheads) of NF-κB p65 (green) is shown relative to DAPI (pseudocolored red). Scale bar, 10 μm. Asterisks denote a significant difference compared to EV for each timepoint, as determined by Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant.

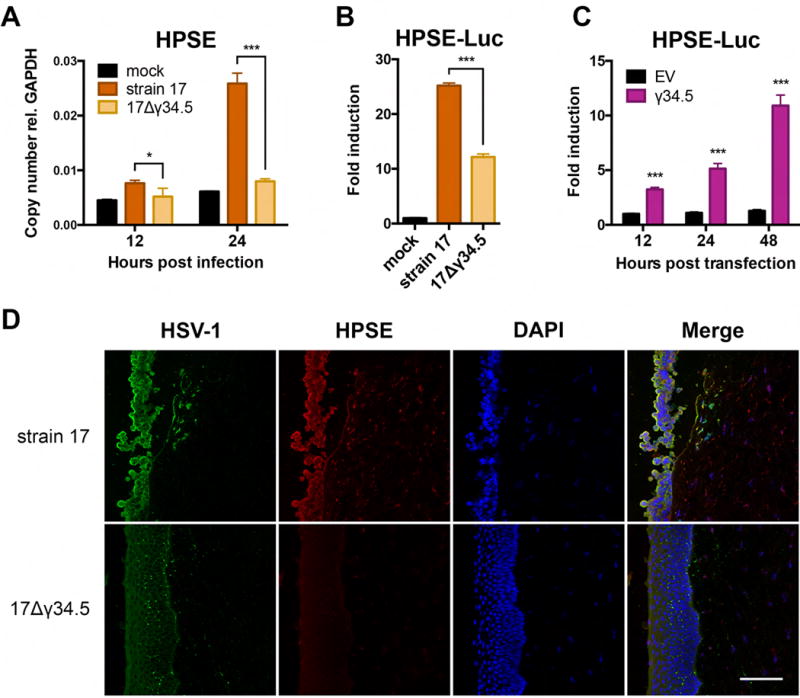

Upregulation of cellular HPSE can be driven by HSV-1 ICP34.5

HSV-1 is capable of increasing expression and activation of cellular HPSE (Hadigal et al., 2015), and we have been interested in understanding which specific viral factors are involved in this upregulation. Given evidence that HSV-1 infected cell protein (ICP) 34.5 is involved in regulation of the interferon system and viral egress (Jing et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2016), we investigated whether this protein could serve as a viral activator of HPSE. Infection of HCE cells with a mutant virus lacking the γ 34.5 gene was markedly impaired in its ability to upregulate HPSE mRNA expression (Figure 5A). Likewise, infection of HCE cells transfected with a plasmid containing the HPSE promoter region fused to luciferase gene (HPSE-Luc) produced decreased luciferase signal at 24 hpi in the absence of ICP34.5 (Figure 5B). Moreover, co-transfection of γ 34.5 gene and HPSE-Luc plasmids in HCE cells was sufficient to increase expression of luciferase driven by the HPSE promoter (Figure 5C). These results were also confirmed in a more physiological corneal tissue setting. Infection of ex vivo cultured porcine corneas showed dramatically increased expression of HPSE in strain 17 versus 17Δγ34.5, with co-localization of HSV-1 and HPSE in tissue (Figure 5D). Mock-infected controls and secondary antibody only stains are shown in Figure S4. This is a well-established and clinically relevant model to study corneal physiology and infection (Alekseev et al., 2012; Thakkar et al., 2017). γ 34.5 is a “gamma” gene, expressed late in a lytic infection, so it makes sense that a late gene product would play a role in the upregulation of HPSE, which is also seen during the later stages of infection (Hadigal et al., 2015).

Figure 5. Viral upregulation of cellular HPSE can be driven by HSV-1 ICP34.5.

A, Copy number of HPSE transcripts relative to GAPDH in HCE cells infected with HSV-1 (17) parental strain or 17Δγ34.5 mutant virus lacking ICP34.5 expression, or mock treated. B, Luciferase induction in HCE cells transfected with HPSE-luc plasmid and then infected for 24 h with HSV-1 (17) parental strain or 17Δγ34.5 mutant virus, or mock treated. C, Luciferase induction in HCE cells co-transfected with HPSE-luc plasmid and EV or γ34.5 plasmid, then assayed at specified timepoints. D, Representative immunofluorescence micrographs of porcine corneas infected for 24 h with HSV-1 (17) parental strain or 17Δγ34.5 mutant virus, then stained for HSV-1 (green), HPSE (red), and DAPI (blue). Antibody staining controls are presented in Figure S4. Scale bar, 100 μm. All plotted results are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n=3). Asterisks denote a significant difference as determined by Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant.

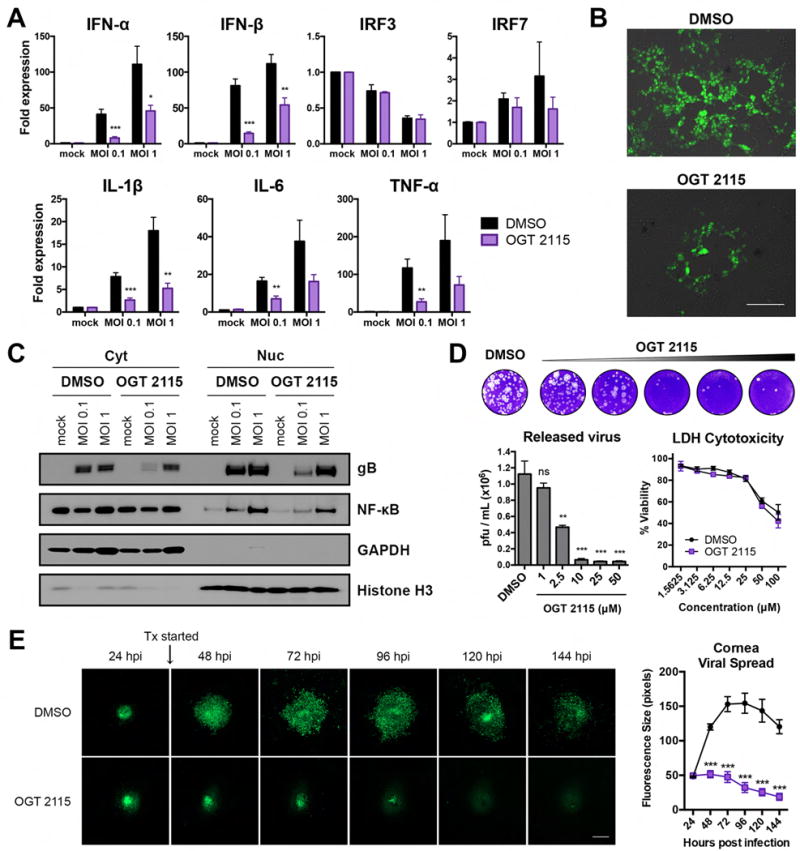

Pharmacological inhibition of HPSE by OGT 2115 blocks spread of HSV-1 infection

To further verify that the control of interferon and pro-inflammatory factor expression described above is specific to HPSE, and that HPSE can be an effective new target for antiviral therapy, we employed a previously characterized and commercially available HPSE inhibitor, OGT 2115. This compound functionally blocks HPSE activity (Courtney et al., 2005), and does not significantly modulate its expression. Treatment of HCE cells at 2 hpi with OGT 2115 resulted in decreased expression of pro-inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Figure 6A). Coincidentally, type I interferons were decreased by OGT 2115 treatment, as observed with GS3-HPSE overexpression. We also noticed that OGT 2115 effectively decreased spread of HSV-1 in HCE monolayers, as visualized with infection by GFP-HSV-1 (K26-GFP) (Figure 6B). Size of typical plaque formations was substantially decreased, suggesting that inhibition of HPSE led to decreased passage of virus from infected to uninfected neighboring cells. Western blot analysis of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from HCE cells also showed decreased total gB and decreased NF-κB nuclear translocation with OGT 2115 treatment (Figure 6C). Western blot quantification is presented in Figure S5A, and full-length western blots are shown in Figure S6. OGT 2115 also markedly restricted virus release from HCE cells into the culture supernatant, as quantified by plaque assay on Vero cells (Figure 6D, Figure S5B). Dose titration confirmed this effect peaked at 10 μM, after which higher concentrations of the DMSO vehicle became toxic to cells. There was no discernable difference in cellular toxicity between OGT 2115 and DMSO at each concentration. Finally, in the ex vivo porcine cornea infection model, spread of GFP-HSV-1 (17-GFP) from a single puncture inoculation site was monitored with addition of treatment (Tx) or vehicle at 24 hpi. OGT 2115 addition to culture media arrested spread of infectious virus and resulted in eventual clearance of virus, whereas vehicle treated lesions continued to expand with time. Representative fluorescence images and quantification are shown in Figure 6E. Thus, therapeutic administration of OGT 2115 may be a promising approach to curb growth and dissemination of herpesviral lesions of the cornea.

Figure 6. Pharmacological inhibition of HPSE by OGT 2115 blocks progression of HSV-1 infection.

A, Transcript fold expression relative to DMSO mock, normalized to GAPDH, in HCE cells mock treated or infected with HSV-1 (KOS) for 24 h. B, Representative fluorescence micrographs of HCE cells infected with GFP-HSV-1 (K26-GFP MOI 0.1) in the presence of DMSO or OGT 2115. Scale bar, 50 μm. C, Representative western blot of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts of HCE cells mock treated or infected for 24 h with HSV-1 (KOS) in the presence of DMSO or OGT 2115. GAPDH and Histone H3 reflect cytoplasmic and nuclear content, respectively. D, Representative plaque assay and quantification of virus released into supernatants of HCE cells infected with HSV-1 (KOS MOI 0.1) in the presence of DMSO or OGT 2115 at the specified concentrations. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) cytotoxicity assay results are shown at right. E, Representative fluorescence micrographs of ex vivo porcine corneas infected with GFP-HSV-1 (17-GFP) in the presence of DMSO or OGT 2115; quantification of fluorescence at right. Scale bar, 200 μm. All results are presented as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments (n=3). Asterisks denote a significant difference as determined by Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant. See also Figure S5, S6.

Conclusion

By using viral infection as a tool to study host cell biology, we have defined new roles for HPSE in maintenance of cellular homeostasis and pathogenesis. With our approach of HPSE overexpression, we have amplified the effect of the HPSE upregulation seen in HSV infection to understand the contributions of this enzyme to disease progression. It is clear from our work that active HPSE has profound effects on pathogenesis, acting through multiple mechanisms. Viral upregulation of HPSE at the nucleus results in decreased interferon signaling and increased NF-κB activation. Inhibition of type I interferon signaling would make neighboring cells more susceptible to infection, thus promoting viral spread. Increased NF-κB activation and pro-inflammatory factor production and secretion could account for increased recruitment of immune cells and endothelial cells to the disease site. In the case of the eye, this could lead to corneal opacification, neovascularization, and potentially blindness. Moreover, these pro-inflammatory conditions may explain the defect in wound healing, as increased levels of cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α have been associated with non-healing wounds (Trengove et al., 2000). We suspect that inhibition of viral HPSE upregulation or removal of the protein altogether will produce large reductions in virulence and manifestations of disease. Recently, HPSE has been shown to be upregulated and activated in multiple viral infections (Hadigal et al., 2015; Puerta-Guardo et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2017), suggesting that our findings will likely also apply to other pathogens outside of the herpesvirus family. With several HPSE-blocking agents currently in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials for various cancers, targeting HPSE in infection could be an effective and attainable strategy for which there already exists a wealth of clinical information. Overall, our work highlights the importance of HPSE as a host-encoded pathogenic factor, and calls for further attention to this enzyme and other host factors in the treatment of viral infection and other inflammatory conditions.

Experimental Procedures

Cells and viruses

Human corneal epithelial (HCE) cell line (RCB1834 HCE-T) was obtained from Kozaburo Hayashi (National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD) and was cultured in MEM (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies). HCE cell identity was confirmed by short tandem repeat analysis. HeLa cells were obtained from Dr. Patricia G. Spear (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL) and cultured in DMEM (Life Technologies) with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Wildtype and heparanase-knockout mouse embryonic fibroblasts (WT and HPSE KO MEFs) were provided by Dr. Israel Vlodavsky (Rappaport Instititute, Haifa, Israel) (Zcharia et al., 2009). All cells were maintained in a Heracell VIOS 160i CO2 incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and have been confirmed negative for mycoplasma contamination. HSV-1 viruses used in this study, KOS-WT and McKrae strains, were provided by Dr. Patricia G. Spear (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL). 17Δγ34.5 and parental strain 17 viruses were obtained from Dr. Richard Thompson (University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH) (Bolovan et al., 1994). All virus stocks were propagated in Vero cells and stored at −80°C. All infections were performed with HSV-1 KOS-WT at multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1 unless mentioned otherwise.

Antibodies, plasmids, and reagents

HPSE antibody (AB-476, Advanced Targeting Systems, San Diego, CA) and Heparan Sulfate-FITC antibody (H1890-10, US Biological, Salem, MA) were used for immunofluorescence studies (1:100). The following antibodies and dilutions were used for western blot: HPSE 1:200 (sc-25825, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), HPSE 1:200 (16673-AP-1, Proteintech Group, Inc., Rosemont, IL), NF-κB p65 1:500 (sc-372, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), IRF3 1:500 (11904, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), IRF7 1:500 (4920, Cell Signaling), gB 1:10,000 (ab6505, Abcam) Histone H3 1:1000 (4499, Cell Signaling), GAPDH 1:1000 (sc-25778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Human HPSE expression constructs WT-HPSE, GS3-HPSE, C-DOM, and TIMB were a gift of Dr. Israel Vlodavsky (Rappaport Institute, Haifa, Israel) (Fux et al., 2009). All in vitro overexpression transfections were performed using Lipofectamine-2000 transfection reagent (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s specifications. OGT 2115 was purchased from Tocris Biosciences and has been previously described as a HPSE inhibitor (Courtney et al., 2005). OGT 2115 was used at 10 μM unless otherwise specified. LDH cytotoxicity assay (Thermo Fisher 88953) was performed according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

Mouse cornea nucleic acid delivery and ocular infection

Animal care and procedures were performed in accordance with the institutional and NIH guidelines, and approved by the Animal Care Committee at University of Illinois at Chicago. 6–8 week old male and female BALB/c mice from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) were used for animal experiments. Mice were randomly chosen to receive one of two corneal transfection treatments. Plasmids containing human GS3-HPSE or empty vector were introduced into the epithelium of one cornea per mouse using a previously established protocol (Stechschulte et al., 2001; Hadigal et al., 2015). Briefly, mice were anaesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg), and proparacaine (Bausch & Lomb, Tampa, FL) was applied for 3 min to achieve local anaesthesia. A superficial nick in the corneal epithelium and anterior stroma of mouse eyes was made 0.5 mm inward from the temporal limbus with a 30-gauge needle to create a track for nucleic acid injection. DNA (1 μg in 2 μL) was injected into the stroma using a 33-gauge Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV). The next day, anaesthetized mouse corneas were infected according to a previously described protocol (Babu et al., 1996). Mouse eyes were infected 24 h post transfection with KOS or McKrae HSV-1 strains (106 pfu in 5 μL) after scarification of the cornea in a 3×3 grid with a 30-gauge needle. All images of the corneal surface were acquired with SteREO Discovery.V20 (Zeiss, Germany).

Clinical scoring of corneal keratitis

Seven days post ocular infection, a blinded observer applied fluorescein dye strips to the sclera of mouse eyes, examined corneas with a handheld slit-lamp biomicroscope and scored the severity of epithelial lesions according to the following established criteria: 0, no epithelial lesion or punctate epithelial erosion; 1, stellate keratitis or residue of dendritic keratitis; 2, dendritic keratitis occupying less than one quarter of the cornea; 3, dendritic keratitis occupying one quarter to one half of the cornea; 4, dendritic keratitis extending over more than one half of the cornea (Inoue et al., 2000).

Flow cytometry

Submandibular lymph nodes were extracted from BALB/c mice after euthanasia. Lymph node tissues were treated with 2 mg/mL collagenase (Sigma C0130) for 1 hr at 37°C and triturated with a pipet tip. Cell suspensions were filtered through a 70 um mesh, resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS, 5% FBS, 0.05% sodium azide), and counted by hemocytometer. 106 cells from each sample were aliquoted into V-bottom 96-well plates for subsequent staining. FC-receptors were blocked using TruStain fcX (101319, Biolegend, San Diego, CA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The following conjugated primary antibodies from Biolegend were used for cell surface staining: APC anti-mouse CD3e (100311), FITC anti-mouse CD25 (101907), FITC anti-mouse CD45 (103107), APC anti-mouse Ly-6G/Ly-6C (108411), PE anti-mouse F4/80 (123109). The following conjugated primary antibodies from Tonbo Biosciences (San Diego, CA) were used for cell surface staining: PE anti-mouse CD4 (50-0042), APC anti-mouse CD8a (20-1886). Cells were immunolabeled, washed, and analyzed with a SH800S Cell Sorter (Sony Biotechnology Inc., San Jose, CA).

In vitro wound healing assay

HCE, HeLa, or WT/HPSE KO MEFs at 80–90% confluency were transfected using Lipofectamine-2000, according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and incubated for 16 h. A 10 μL pipet tip was then dragged across the surface of the dish to create a cellular defect, and washed twice with PBS before applying virus or mock treatment. At specified timepoints, brightfield images were captured with an Axiovert 200 microscope (Zeiss). Reference lines were marked to ensure the same locations were imaged at each timepoint.

In vivo corneal wound healing assay

Naïve BALB/c mice corneas were transfected according to the aforementioned protocol (one eye per mouse). The following day, a portion of the corneal epithelium was debrided, following a previously established protocol (Miyazaki et al., 2008). Briefly, a circular defect was produced in the central corneal epithelium by using a 1.5 mm diameter trephine (Miltex 33-31A, Integra, York, PA) and a dull microsurgery blade (Swann-Morton SM69, UK). Fluorescein stained corneal wounds were imaged on GFP channel of SteREO Discovery.V20 (Zeiss) immediately following the initial injury and every 24h.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was then transcribed to cDNA using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Life Technologies). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies) using QuantStudio 7 Flex (Life Technologies).

The following human-specific primers were used in this study:

GAPDH fwd 5′-CACCACCAACTGCTTAGCAC-3′ and rev 5′-CCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAAT-3′,

IFNA fwd 5′-GATGGCAACCAGTTCCAGAAG-3′ and rev 5′-AAAGAGGTTGAAGATCTGCTGGAT-3′,

IFNB fwd 5′-CTCCACTACAGCTCTTTCCAT-3′ and rev 5′-GTCAAAGTTCATCCTGTCCTT-3′,

IRF3 fwd 5′-TCTTCCAGCAGACCATCTCC-3′ and rev 5′-TGCCTCACGTAGCTCATCAC-3′,

IRF7 fwd 5′-TGGTCCTGGTGAAGCTGGAA-3′ and rev 5′-GATGTCGTCATAGAGGCTGTTGG-3′,

IL1B fwd 5′-TCGCCAGTGAAATGATGGCT-3′ and rev 5′-TGGAAGGAGCACTTCATCTGTT-3′,

IL6 fwd 5′-AACTCCTTCTCCACAAGCGCC-3′ and rev 5′-GTGGGGCGGCTACATCTTT-3′,

TNFA fwd 5′-AGCCCATGTTGTAGCAAACCC-3′ and rev 5′-GGACCTGGGAGTAGATGAGGT-3′.

The following mouse-specific primers were used in this study:

GAPDH fwd 5′- TTCACCACCATGGAGAAGG-3′ and rev 5′- AGAAGGGGCGGAGATGAT-3′,

IFNA fwd 5′-CCTGCTGGCTGTGAGGAAAT-3′ and rev 5′-GACAGGGCTCTCCAGACTTC-3′,

IFNB fwd 5′-TGTCCTCAACTGCTCTCCAC-3′ and rev 5′-CATCCAGGCGTAGCTGTTGT-3′,

IRF3 fwd 5′-GACAAAGAAGGGGGTTGCGT-3′ and rev 5′-CTCTAGCCAGGGGAGGAATTG-3′,

IRF7 fwd 5′-CCAGGAGCAAGACCGTGTTT-3′ and rev 5′-ATGGTCACATCCAGGAACCC-3′.

Luciferase assay

pIFNb-Luc plasmid expressing firefly luciferase driven by the promoter region of IFN-β was provided by Dr. Biao He (University of Georgia) (Luthra et al., 2011). Cells were co-transfected with experimental (HPSE variant or empty vector) plasmids and luciferase plasmid using Lipofectamine-2000, according to the manufacturer’s specifications. At specified timepoints, cells were lysed in Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI). Lysates were incubated with luciferin substrate (Promega), and luciferase activity was immediately measured using Berthold Luminometer. pGL3-Basic was used as a control for transfection efficiency. pHep1-luc plasmid expressing firefly luciferase driven by the 0.7-kb promoter area upstream of the transcription start site of human HPSE was provided by Dr. Xiulong Xu (Rush University) (Jiang et al., 2002). Cells were co-transfected with pHep1-luc and γ134.5-Flag or empty vector, provided by Dr. Bin He (University of Illinois at Chicago) (Ma et al., 2012), and processed as described above.

Western blot

Proteins samples were collected using radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 4X LDS sample loading buffer (Life Technologies) and 5% beta-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) were added to cell lysates, and these samples were denatured at 95°C for 8 min. After gel electrophoresis, membranes were blocked in 5% milk/TBS-T for 1h followed by incubation with primary antibody overnight. After washes and incubation with respective horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-mouse 1:10,000 or anti-rabbit 1:20,000) for 1 h, protein bands were visualized using the SuperSignal West Femto maximum sensitivity substrate (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) with Image-Quant LAS 4000 biomolecular imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). The densities of protein bands were quantified using ImageJ.

Nuclear/cytoplasmic protein extraction

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were collected following Thermo Scientific’s Nuclear Extraction Protocol. Briefly, cells were washed with cold PBS and collected using a cell scraper. Cells were then treated with hypotonic buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2) and a final concentration of 0.5% NP-40, then centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Cytoplasmic fractions were collected, and the pellet was treated with Cell Extraction Buffer (Thermo Scientific) with added Halt Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific) to collect nuclear fractions. Samples were mixed with 4X LDS sample buffer (Life Technologies) and 5% beta-mercaptoethanol (Bio-Rad) and denatured at 95°C for 8 min and run on SDS-PAGE.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

HCE cells were cultured in glass bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA) or 8-well μ-slides (iBidi, Madison, WI). Cells were fixed in 10% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X for 10 min at room temperature for intracellular labeling. This was followed by incubation with primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. When a secondary antibody was needed, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit 1:100 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were examined under LSM 710 confocal microscope (Zeiss) using a 63× oil immersion objective. Fluorescence intensity of images was calculated using ImageJ.

Plaque assay

Monolayers of HCE cells were infected with HSV-1 (KOS MOI 0.1) in Opti-MEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 2 h incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2, inoculation solution was aspirated, cells were washed once with PBS, and complete MEM containing 10 μM DMSO or specified concentration of OGT 2115 (Tocris Biosciences) was added for 24 h. Culture supernatants were then collected, centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 1 min, serially diluted in Opti-MEM, and overlayed on confluent monolayers of Vero cells in 24-well plates. After 2 h incubation, cells were washed, and complete DMEM containing 0.5% methylcellulose (Fisher Scientific) was added to cells for 48 to 72 h. To visualize and count plaques, cells were fixed with 100% methanol and stained with crystal violet solution.

Ex vivo porcine cornea infection

All work involving ex vivo porcine cornea infection model was performed as previously described, with minor modifications (Alekseev et al., 2012; Thakkar et al., 2017). Briefly, whole pig eyes were obtained from Park Packing, Inc., Chicago, IL, immediately after sacrificing. Corneal tissues were excised from the whole eye, rinsed in PBS containing 5% antibiotic-antimycotic (Gibco), cut into two equal halves, poked once with a 27-gauge needle, and incubated epithelial side up in 12-well plates containing serum-free MEM supplemented with 5% antibiotic-antimycotic and 1% insulin-transferrin-sodium selenite (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C, 5% CO2. Each excised half cornea was inoculated with 106 pfu of 17-GFP in 1 mL of the above media and incubated for 24 h. The inoculation solution was then removed, corneas were washed with PBS, and fresh culture media containing 10 mM DMSO or 10 mM OGT 2115 was added to each respective half cornea. At 24 h intervals after infection, the same locations on each cornea were imaged on GFP channel of SteREO Discovery.V20 (Zeiss) at 100× magnification to observe infection. Fresh media containing DMSO or OGT 2115 was added every 24 h.

Immunohistochemistry

Porcine corneas were obtained and handled as described above. After excising and 1 h incubation in cornea media, each half cornea was infected with 106 pfu of strain 17 or 17Δγ34.5 mutant virus in 1 mL of media. At 48 hpi, corneas were washed in PBS and embedded in Tissue-Tek OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and stored at −80°C. 10 μm sections were cut using Cryostar NX50 microtome (Thermo Scientific). Sections were air dried at room temperature for 10 min and then fixed in ice-cold acetone for 15 min. Two 10 min washing steps were performed in TBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) before blocking with 1% BSA in TBS-T for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with a cocktail of mouse anti-HPSE (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology sc-293205) and rabbit anti-HSV (1:100, Abcam ab9533) overnight at 4°C. As a control, sections were incubated without primary antibodies. After subsequent washes in TBS-T sections were incubated with a cocktail of anti-mouse Cy5 (1:200, Abcam ab6563) and anti-rabbit FITC (1:200, Sigma F9887) for 1 h at room temperature. Following washes in TBS-T, sections were mounted in Vectashield mounting media containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and imaged at 20× magnificiation on LSM 710 confocal microscope (Zeiss).

Statistics

Error bars of all figures represent SEM of three independent experiments (n=3), unless otherwise specified. Asterisks denote a significant difference as determined by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ns, not significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

HPSE, activated virally or non-virally, triggers pro-inflammatory disease conditions

Active HPSE, rather than the proenzyme, can generate disease-like conditions

HPSE upregulation requires HSV-1 infected cell protein 34.5

Pharmacological inhibition of HPSE activity thwarts viral pathogenesis

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants R01EY024710 and R21AI128171, and fellowship F30EY025981, a core grant (P30EY001792), and unrestricted funds from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc. We thank Dr. Patricia G. Spear (Northwestern University) for providing viruses used in this study. We are grateful to Ruth Zhelka and Tara Nguyen for their expertise with departmental imaging and animal facilities. We also thank Dr. Israel Vlodavsky (Rappaport Institute) for sharing HPSE variant expression plasmids used in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions

A.M.A. and D.S. designed experiments; A.M.A., S.R.H. and D.J. performed experiments; A.M.A., S.R.H., D.J. and D.S. analyzed the data; A.M.A. and D.S. wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- Agelidis AM, Shukla D. Cell entry mechanisms of HSV: what we have learned in recent years. Future Virol. 2015;10:1145–1154. doi: 10.2217/fvl.15.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alekseev O, Tran AH, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Ex Vivo Organotypic Corneal Model of Acute Epithelial Herpes Simplex Virus Type I Infection. JoVE. 2012 doi: 10.3791/3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino RS, Lee ES, Park PW. Diverse functions of glycosaminoglycans in infectious diseases. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2010;93:373–394. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(10)93016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu JS, Thomas J, Kanangat S, Morrison LA, Knipe DM, Rouse BT. Viral replication is required for induction of ocular immunopathology by herpes simplex virus. J Virol. 1996;70:101–107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.101-107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolovan CA, Sawtell NM, Thompson RL. ICP34.5 mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 strain 17syn+ are attenuated for neurovirulence in mice and for replication in confluent primary mouse embryo cell cultures. J Virol. 1994;68:48–55. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.1.48-55.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EC, Sun Y, Auletta J, Kao WWY, Liu CY, Perez VL, Pearlman E. Regulation of corneal inflammation by neutrophil-dependent cleavage of keratan sulfate proteoglycans as a model for breakdown of the chemokine gradient. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:517–522. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0310134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulson-Thomas VJ, Chang SH, Yeh LK, Coulson-Thomas YM, Yamaguchi Y, Esko J, Liu CY, Kao W. Loss of corneal epithelial heparan sulfate leads to corneal degeneration and impaired wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:3004–3014. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney SM, Hay PA, Buck RT, Colville CS, Phillips DJ, Scopes DIC, Pollard FC, Page MJ, Bennett JM, Hircock ML, et al. Furanyl-1,3-thiazol-2-yl and benzoxazol-5-yl acetic acid derivatives: novel classes of heparanase inhibitor. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:2295–2299. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448–462. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux L, Feibish N, Cohen-Kaplan V, Gingis-Velitski S, Feld S, Geffen C, Vlodavsky I, Ilan N. Structure-function approach identifies a COOH-terminal domain that mediates heparanase signaling. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1758–1767. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg R, Meirovitz A, Hirshoren N, Bulvik R, Binder A, Rubinstein AM, Elkin M. Versatile role of heparanase in inflammation. Matrix Biol. 2013;32:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Zhu Z, Guo Y, Wang X, Yu P, Xiao S, Chen Y, Cao Y, Liu X. Heparanase upregulation contributes to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus release. J Virol. 2017 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00625-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadigal SR, Agelidis AM, Karasneh GA, Antoine TE, Yakoub AM, Ramani VC, Djalilian AR, Sanderson RD, Shukla D. Heparanase is a host enzyme required for herpes simplex virus-1 release from cells. Nature Communications. 2015;6:6985. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He YQ, Sutcliffe EL, Bunting KL, Li J, Goodall KJ, Poon IKA, Hulett MD, Freeman C, Zafar A, McInnes RL, et al. The endoglycosidase heparanase enters the nucleus of T lymphocytes and modulates H3 methylation at actively transcribed genes via the interplay with key chromatin modifying enzymes. Transcription. 2012;3:130–145. doi: 10.4161/trns.19998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks RL, Tumpey TM. Contribution of virus and immune factors to herpes simplex virus type I-induced corneal pathology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:1929–1939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong X, Nelson K, Lemke N, Kalkanis SN. Heparanase expression is associated with histone modifications in glioblastoma. Int J Oncol. 2012;40:494–500. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Inoue Y, Nakamura T, Yoshida A, Takahashi K, Inoue Y, Shimomura Y, Tano Y, Fujisawa Y, Aono A, et al. Preventive effect of local plasmid DNA vaccine encoding gD or gD-IL-2 on herpetic keratitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:4209–4215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Kumar A, Parrillo JE, Dempsey LA, Platt JL, Prinz RA, Xu X. Cloning and characterization of the human heparanase-1 (HPR1) gene promoter: role of GA-binding protein and Sp1 in regulating HPR1 basal promoter activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8989–8998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105682200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing X, Cerveny M, Yang K, He B. Replication of herpes simplex virus 1 depends on the gamma 134.5 functions that facilitate virus response to interferon and egress in the different stages of productive infection. J Virol. 2004;78:7653–7666. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7653-7666.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye S, Choudhary A. Herpes simplex keratitis. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2006;25:355–380. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickelbein JE, Buela KA, Hendricks RL. Herpes stromal keratitis: erosion of ocular immune privilege by herpes simplex virus. Future Virol 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Levy DE, Marié IJ, Durbin JE. Induction and function of type I and III interferon in response to viral infection. Current Opinion in Virology. 2011;1:476–486. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthra P, Sun D, Silverman RH, He B. Activation of IFN-β expression by a viral mRNA through RNase L and MDA5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2118–2123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012409108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Jin H, Valyi-Nagy T, Cao Y, Yan Z, He B. Inhibition of TANK binding kinase 1 by herpes simplex virus 1 facilitates productive infection. J Virol. 2012;86:2188–2196. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05376-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki KI, Okada Y, Yamanaka O, Kitano A, Ikeda K, Kon S, Uede T, Rittling SR, Denhardt DT, Kao WWY, et al. Corneal wound healing in an osteopontin-deficient mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:1367–1375. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobuhisa T, Naomoto Y, Okawa T, Takaoka M, Gunduz M, Motoki T, Nagatsuka H, Tsujigiwa H, Shirakawa Y, Yamatsuji T, et al. Translocation of heparanase into nucleus results in cell differentiation. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:535–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish CR. The role of heparan sulphate in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nri1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park PJ, Shukla D. Role of heparan sulfate in ocular diseases. Experimental Eye Research. 2013;110:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puerta-Guardo H, Glasner DR, Harris E. Dengue Virus NS1 Disrupts the Endothelial Glycocalyx, Leading to Hyperpermeability. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005738. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remeijer L, Osterhaus A, Verjans G. Human herpes simplex virus keratitis: the pathogenesis revisited. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2004;12:255–285. doi: 10.1080/092739490500363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert SY, Ilan N, Shushy M, Ben-Izhak O, Vlodavsky I, Goldshmidt O. Human heparanase nuclear localization and enzymatic activity. Lab Invest. 2004;84:535–544. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stechschulte SU, Joussen AM, Recum von HA, Poulaki V, Moromizato Y, Yuan J, D’Amato RJ, Kuo C, Adamis AP. Rapid ocular angiogenic control via naked DNA delivery to cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:1975–1979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar N, Jaishankar D, Agelidis A, Yadavalli T, Mangano K, Patel S, Tekin SZ, Shukla D. Cultured corneas show dendritic spread and restrict herpes simplex virus infection that is not observed with cultured corneal cells. Sci Rep. 2017:1–12. doi: 10.1038/srep42559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari V, Maus E, Sigar IM, Ramsey KH, Shukla D. Role of heparan sulfate in sexually transmitted infections. Glycobiology. 2012;22:1402–1412. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cws106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trengove NJ, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Stacey MC. Mitogenic activity and cytokine levels in non-healing and healing chronic leg ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8:13–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2000.00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlodavsky I, Friedmann Y. Molecular properties and involvement of heparanase in cancer metastasis and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:341–347. doi: 10.1172/JCI13662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Fuster M, Sriramarao P, Esko JD. Endothelial heparan sulfate deficiency impairs L-selectin- and chemokine-mediated neutrophil trafficking during inflammatory responses. Nature Immunology. 2005;6:902–910. doi: 10.1038/ni1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Yang Y, Wu S, Pan S, Zhou C, Ma Y, Ru Y, Dong S, He B, Zhang C, et al. p32 is a novel target for viral protein ICP34.5 of herpes simplex virus type 1 and facilitates viral nuclear egress. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2014;289:35795–35805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.603845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Pan S, Zhang L, Baines J, Roller R, Ames J, Yang M, Wang J, Chen D, Liu Y, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus 1 Induces Phosphorylation and Reorganization of Lamin A/C through the γ134.5 Protein That Facilitates Nuclear Egress. J Virol. 2016;90:10414–10422. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01392-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Esko JD. Demystifying heparan sulfate-protein interactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 2014;83:129–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Gorzelanny C, Bauer AT, Halter N, Komljenovic D, Bäuerle T, Borsig L, Roblek M, Schneider SW. Nuclear heparanase-1 activity suppresses melanoma progression via its DNA-binding affinity. Oncogene. 2015;34:5832–5842. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zcharia E, Jia J, Zhang X, Baraz L, Lindahl U, Peretz T, Vlodavsky I, Li JP. Newly Generated Heparanase Knock-Out Mice Unravel Co-Regulation of Heparanase and Matrix Metalloproteinases. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.