Abstract

Semi-quantitative neuroradiologic studies, quantitative neuron density studies and immunocytochemistry markers of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation indicate neuronal injury and deficits in young patients with chronic poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Present data suggest that pathogenesis of the neuronal deficits in young patients, who die as the result of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and brain edema (BE), does not involve apoptosis, a prominent form of regulated cell death in many disease states. To further address this we studied mediators of macroautophagy, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and apoptosis. In all areas studied we demonstrated increased levels of macroautophagy-associated proteins including light chain-3 (LC3) and autophagy related protein-4 (Atg4), as well as increased levels of the ER-associated glucose-regulated protein78/binding immunoglobulin protein (GRP78/BiP) in T1DM. In contrast, cleaved caspase-3 was rarely detected in any T1DM brain regions. These results suggest that chronic metabolic instability and oxidative stress may cause alterations in the autophagy-lysosomal pathway but not apoptosis, and macroautophagy-associated molecules may serve as useful candidates for further study in the pathogenesis of early neuronal deficits in T1DM.

Keywords: Autophagic gene-4, Cleaved caspase-3, Diabetic encephalopathy, Diabetic ketoacidosis, Glucose-regulated protein78, Light chain-3, Oxidative stress

Introduction

The metabolic instability of suboptimally controlled T1DM includes extremes of hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia and ketonuria, events that can recur from the time of diagnosis. Each of these perturbations of stability can mediate systemic oxidative stress and inflammation, even at an early age (Ceriello, 2006; Esposito et al., 2002; Flores et al., 2004; Gogitidze et al., 2010; Jain et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2004). The treatment of severe diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), a life-threatening form of metabolic instability, is associated with the paradoxical effects of increasing oxidative stress and systemic inflammation (Dalton et al., 2003; Hoffman et al., 2003a,b; Jerath et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2002; Turk et al., 2006) during the time that subclinical brain edema (BE) is progressing, clinical BE is most likely to occur (Edge et al., 2001; Glaser et al., 2001; Hoffman et al., 1988) and metabolic correction is occurring. These oxidative and immunologic stresses compromise neuronal homeostasis (Duarte et al., 2006), neuronal polarity (Sosa et al., 2006) and neurotrophic support (Hoffman et al., 2010, 2011; Sima and Li, 2005).

Neuronal deficits, markers of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation have been reported in the brains of diabetic rat models (Li et al., 2002), in neurodegenerative diseases (Sayre et al., 2008), and in young patients with chronic poorly controlled T1DM resulting in the fatal BE/DKA (Hoffman et al., 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011). Of importance, metabolic dysfunction and oxidative stress have been suggested to be major factors in the onset of Alzheimer disease (AD) (Casadesus et al., 2007). Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation are also involved in the pathogenesis of neuronal deficits of acute trauma (Clark et al., 2008; Sadasivan et al., 2008). However, despite the similarities of the markers there are apparent differences in the pathogenesis of the neuronal death in young patients with poorly controlled T1DM. These include normal neuronal morphology (Hoffman et al., 2011), the absence of TUNEL (Hoffman et al., 2006), and several other immunocytochemical markers of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (Hoffman et al., 2011), the most prominent form of regulated cell death in neurodegenerative diseases (Szegezdi et al., 2006). These dissimilarities suggest the involvement of alternative forms of cell death (Ferraro and Cecconi, 2007; Hoffman et al., 2011; Maiuri et al., 2007; Tan et al., 1998).

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a major metabolic organelle and a nutrient sensor (Mandl et al., 2009). In addition to misfolded proteins triggering the unfolded protein response (UPR) (Raghubir et al., 2011), compensatory ER mechanisms reduce the stress of protein misfolding (Zhang and Kaufman, 2006). Other triggers of UPR include the metabolic factors of hyperglycemia (Inagi, 2011; Sheikh-Ali et al., 2010), hypoglycemia (Ikesugi et al., 2006), lipids (Pineau et al., 2009) and C5b-9, the membrane attack complex (Cybulsky et al., 2002). If compensation is not adequate, continued ER stress can lead to apoptosis (Fribley et al., 2009; Szegezdi et al., 2006) and/or the autophagy-lysosomal pathway, an important lysosome mediated degradation pathway (Bernales et al., 2006). Autophagy plays a major role in cellular homeostasis, serving as 1) a degradation pathway of damaged proteins and organelles that result from oxidative/nitrosative stress (Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007); 2) an adaptive response to metabolic challenges (Kaushik et al., 2010); and 3) possibly a neurotoxic role in neurodegenerative diseases (Cherra and Chu, 2008; Hoozemans et al., 2005).

Two major types of autophagy are macroautophagy (Ravikumar et al., 2010) and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) (Kaushik et al., 2008), both constitutively expressed with the lysosome being their common endpoint. However, they differ in the conditions of activation, their targeted substrate, and regulation. Macroautophagy is the major form of autophagy, and is involved in tissue homeostasis and innate and adaptive immunity (Schmid and Munz, 2007). It has a non-selective response to various forms of stress, is regulated by autophagy-related (Atg) genes and is involved in bulk sequestration of cytosolic components. CMA is dependent on the constitutively expressed heat-shock cognate70 (hsc70), shares 80% homology with the heat-shock protein70 (HSP70), and identifies peptide sequences of cytoplasmic substrates, thus being more selective in its degradation. CMA serves to balance dysregulated energy and is maximally activated by nutrient/metabolic (Cuervo, 2010) and oxidative/nitrosative stresses. Cross-talk has also been established between these two forms of autophagy (Kaushik et al., 2008; Massey et al., 2008; Mehrpour et al., 2010).

We investigated whether the milieu of chronic suboptimal metabolic control in T1DM and the resulting oxidative stress induced markers of macroautophagy in non-dividing differentiated cells (Cuervo, 2004), and is thus a candidate for early neuronal death and diabetic encephalopathy (Nijholt et al., 2011; Pivtoraiko et al., 2009). We addressed this by studying: 1) microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain-3 (LC3/ Atg8), a well-accepted marker of autophagic vacuoles (Tanida et al., 2008); 2) autophagic-related gene-4 (Atg4), a target of oxidative stress (Scherz-Shouval et al., 2007) and an essential protease required for cleavage of LC3; 3) glucose-regulated protein 78/binding immunoglobulin protein chaperone (GRP78/BiP) (Rao et al., 2002) an ER-associated protein that is induced by changes in cellular redox and by hyperglycemia (Liu et al., 2010), and is a regulator of stress-induced UPR and CMA (Li et al., 2008), with a primary function to bind misfolded proteins, and 4) cleaved caspase-3, a key enzyme activated by ER stress (Hitomi et al., 2004) and a critical late stage regulator of both extrinsic (death receptor-mediated) and intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptosis (Stennicke and Salvesen, 2000).

Materials and methods

Case 1

An adolescent girl with a 4-year history of poorly controlled T1DM, which resulted in recurrent hospitalizations for DKA. There was no history of other medical conditions or microvascular disease. There was no history of recurrent fever or enteritis. The final admission was preceded by a 12-h history of abdominal pain and several episodes of emesis. On physical examination, she was oriented but drowsy. Her height was 163 cm; weight was 68.5 kg; blood pressure was 140/70 mm Hg; pulse was 140/min; respirations were 30/min; and temperature was 98.5 F. There were no signs of infection. The mucous membranes were dry, the abdomen was diffusely tender, and bowel pattern sounds were hypoactive. Tanner stage was the-larche stage 3 and pubarche stage 2 (Marshall and Tanner, 1969). Admission laboratory tests consisted of pH 7.10; pCO2, 15 mm Hg; pO2, 106 mm Hg; glucose, 810 mg/dl; Na, 132 meq/L; K, 5.7 meq/L; Cl, 93 meq/L; HCO3, 5 meq/L; BUN, 30 mg/dl; and calculated effective plasma osmolality, 309 Osm. Treatment was in a pediatric intensive care unit, and correction of the hyperglycemia and metabolic acidosis was unremarkable. Twelve hours into treatment, she developed a sudden onset of labored respirations and within 20 min, had a cardio-respiratory arrest. An emergency CT scan showed sulcal effacement and cerebral and pontine edema with evidence of herniation. Efforts at resuscitation were unsuccessful, and she was pronounced dead 1.5 h after the cardiorespiratory arrest.

Case 2

An adolescent girl had an 8-year history of poorly controlled T1DM, which had resulted in recurrent hospitalizations for DKA. There was no history of other medical conditions or microvascular disease. The final admission was preceded by an 18-h history of capillary blood glucoses of over 300 mg/dl, ketonuria, a 4-h history of headache, and several episodes of emesis. There was no history of fever or enteritis. On physical examination, she was slightly confused and lethargic. Her height was 154 cm; weight was 45 kg; blood pressure was 135/68 mm Hg; pulse was 132/min; respirations were 26/min; and temperature was 97 F. There were no signs of infection. Diffuse abdominal tenderness and decreased bowel sounds were present. The Tanner stage was thelarche stage 2 and pubarche stage 1 (Marshall and Tanner, 1969). Admission laboratory tests consisted of pH 7.16; pCO2, 17 mm Hg; pO2, 100 mm Hg; blood glucose, 581 mg/dl; Na, 130 meq/L; K, 4.8 meq/L; Cl, 89 meq/ L; HCO3, 6 meq/L; BUN, 28 mg/dl; and calculated effective plasma 292 Osm. Treatment was in a pediatric intensive care unit, and correction of the hyperglycemia and metabolic acidosis was unremarkable. Ten hours into treatment, she became unresponsive and was treated with mannitol and hyperventilation and placed on mechanical ventilation. A CT head scan showed diffuse cerebral edema and decreased intercaudate diameter. She was pronounced dead approximately 10 h after the cardiorespiratory arrest.

Control brain tissue consisted of two age matched, non-diabetic cases.

Immunostaining

Brain tissue samples were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin wax by conventional techniques. The paraffin blocks were then cut into 5 μm thick sections that were subsequently mounted. The slides were deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated through a descending ethanol series (100%, 95%, 70%, 50%, 3 min each) and washed in Tris-buffered saline for 2–5 min. Antigen retrieval was achieved by immersing slides in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6) and microwaving at 800 W for 3–5 min, followed by a 20 minute rest period. The slides were then incubated in blocking solution [5% normal goat serum (NGS), 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% TritionX-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] for 30 min at room temperature to prevent non-specific background staining. For double-labeling immunofluorescence experiments the samples were exposed to either mouse anti-human β-III-tubulin, mouse anti-Iba1 (Abcam, MA) or mouse anti-GFAP (Sigma Aldrich, MO) at 4 °C overnight, and visualized with either FITC- or Texas Red-conjugated secondary anti-mouse antibody (Vector Laboratory, CA). The sections were then incubated overnight with either rabbit anti-human GRP78, LC3A/B or sheep-anti human Atg4C antibody (all from Abcam, MO), followed by incubation with either FITC or Texas Red-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-sheep antibody (Vector Laboratory, CA). The sections were mounted in Vectashield Mounting Medium (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, CA) and viewed on a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 510 Zeiss, Germany, objective 40×1.3 NA). Negative controls included sections that were treated in the same manner with omission of the primary antibody as well as controls treated with mouse, sheep or rabbit IgG isotype control.

Chromogenic in situ detection of cleaved caspase-3

Sections from paraffin-embedded brains were deparaffinized and subjected to antigen retrieval in citrate buffer with heat, then incubated for 5 min with 3% H2O2 in PBS to reduce endogenous peroxidase activity. Sections were incubated in PBS blocking buffer (PBSBB; 1% BSA, 0.2% evaporated milk, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 30 min, followed by overnight (4C) incubation in PBSBB with rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technologies). After PBS washes, slides were incubated with HRP-cojugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (SuperPicture, Zymed) followed by PBS wash. Antibody localization was detected via Tyramide Signal Amplification (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences) using biotin-conjugated tyramide (30 min, RT followed by PBS wash), Vectastain ABC (Vector Labs; 30 min, RT followed by PBS wash) and DAB chromogen (Pierce, Rockford, IL; 10–15 min, RT followed by distilled H2O wash). Slides were counter-stained with hematoxylin, de-colorized with acid-ethanol and incubated with bluing reagents (1% ammoniumhydroxide), dehydrated in increasing percentages of ethanol, cleared in xylene and then coverslipped with Cytoseal 60TM.

Evaluation of immunostaining

For quantification of immunostaining intensity brain images were taken at 20× magnification using identical camera settings so that the number and intensity of pixels would reflect the differences in their protein expression. The protein level of GRP78, LC3 and Atg4 was determined by measuring the area (number of pixels) and fluorescent intensity (average intensity of pixels) of the staining from twenty four images captured randomly in the brain parenchyma from DKA and control sections. The unit area of each image was 0.172 mm2. Analysis was performed using the Image J program (NIH software program). The relative expression was calculated by multiplying the number of pixels (area) by the average intensity of pixels.

The number of neurons, astrocytes and microglial cells that expressed GRP78, LC3 and Atg4, were evaluated by counting the number of βIII-tubulin+, GFAP+, or Iba1+ which were GRP78+, LC3+ or Atg4+, in five randomly chosen microscopic fields (at 10× magnification per section). A mean of the percentage βIII-tubulin+, GFAP+, or Iba1++/−SD was computed by dividing the number of these cells in the DKA cases by the number in the controls multiplied by 100.

Statistics

All values are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Unpaired t test was performed to identify the differences between the two groups. A probability value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Prism software (Graph Pad Prism 3.0, San Diego, CA) was used for statistics.

Results

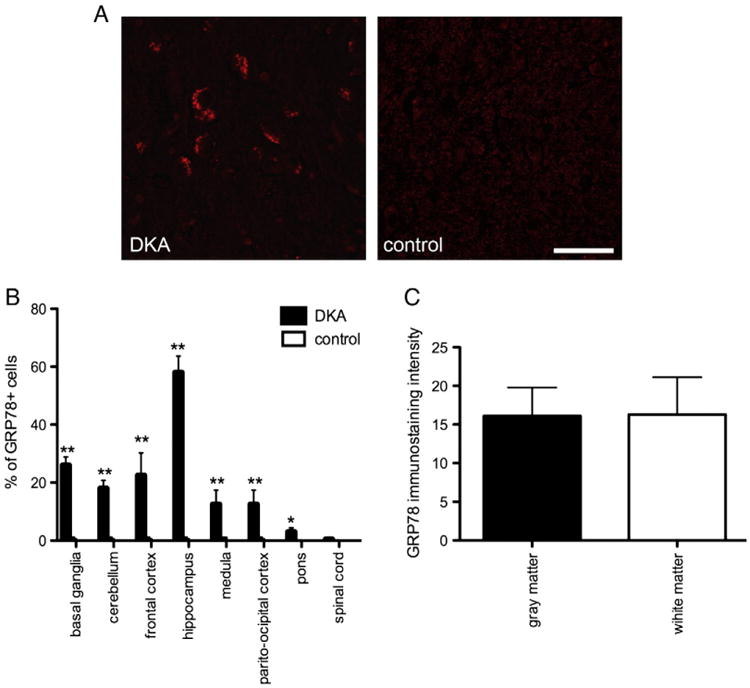

GRP78 levels in neurons

Immunocytochemistry of brain sections showed that GRP78, localized primarily to the cytoplasm of cells in basal ganglia, cerebellum, frontal cortex, hippocampus, parieto-occipital cortex, pons and medulla. Diffuse cytoplasmic staining was predominantly present in neurons (βIII tubulin+cells), (Fig. 1A) while sporadic expression of GRP78 was seen in microglia and astrocytes. Quantitative immunohistochemical analysis showed a specific distribution pattern for GRP78+ neurons. The majority of neurons in the hippocampus (59±4.3%) of the DKA cases were GRP78+ while the basal ganglia, cerebellum, frontal cortex, parieto-occipital cortex and medulla had GRP78+neurons in the range of 24± 3.2%, 18±3.5%, 22±5, 15±4%, 15±3%, respectively (Fig. 1B). Sporadic expression of GRP78 was present in the neurons of the pons and spinal cord. In contrast the correspondent areas of the control brain samples showed very weak or absent GRP78+ staining, in neurons and glial cells and quantitative analysis indicated significantly less GRP78+ staining compared with DKA brains (p<0.001). The analysis of the GRP78 immunostaining in gray (cerebral cortex, subcortical gray matter, cerebellar cortex, brain stem nuclei, and spinal central gray matter) and white matter did not show any differences in the intensity for GRP78 staining in the DKA brains (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

(A) Representative images of GRP78+ neurons in the hippocampus of DKA brains and control cases. Scale bar=20 μm. (B) Percentage of GRP78+ immunostaining neurons in the indicated areas of DKA and control cases. Error bars indicate +/−SD. (**) P<0.001 (C) Quantification of GRP78 fluorescence intensity in the gray and white matter of DKA brains. Data represent average of +/−SD of five chosen microscopic fields per section at 10× magnification.

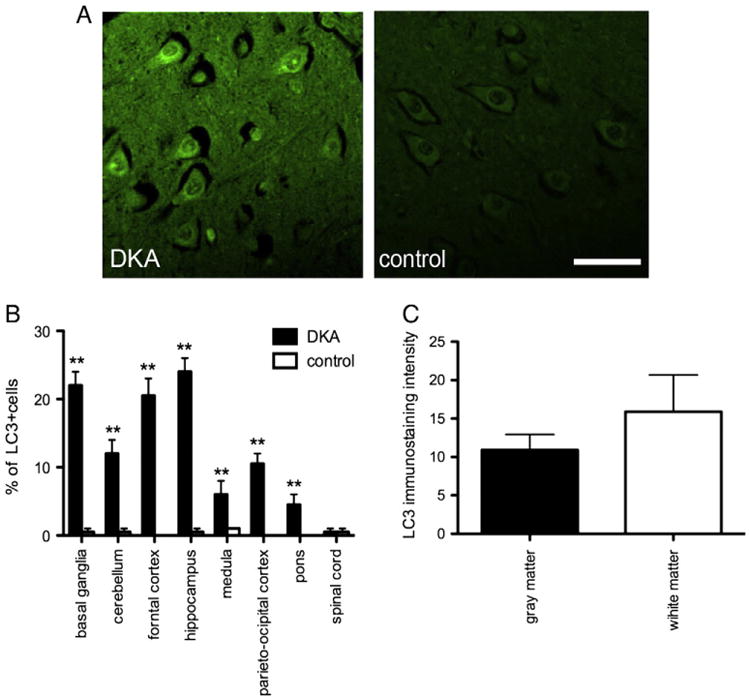

LC3 and Atg4 levels in neurons

Emerging studies indicate that a variety of cellular stresses, such as endoplasmic reticulum stress or mitochondrial dysfunction can induce autophagy, which could be selectively involved in removal of the oxidative modified macromolecules and organelles. Due to the fact that we found increased levels of markers for oxidative stress and ER stress in DKA we analyzed relative levels of autophagy associated proteins in DKA neurons. Immunofluorescence staining indicated DKA neurons exhibited increased levels of microtubule-associated protein light-chain 3 (LC3), an autophagosome marker. In the observed areas of the DKA brains neurons exhibited punctate perinuclear LC3+ immunoreactivity while glial cells (predominantly astrocytes and microglia) exhibited faint or absent immunoreactivity. The distribution of LC3+ neurons was similar to GRP78+ neurons. The LC3 levels were slightly greater in hippocampal neurons although there were similar numbers of LC3+ neurons in the basal ganglia and frontal cortex (24±3.2; 22±3.1; 21± 4.1, retrospectively) (Figs. 2A, B). Approximately 10% of βIII neurons in the cerebellum, pons and medulla showed LC3 expression. Similar to GRP78 there was no difference in LC3 immunostaining intensity in structures of gray and white matter (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

(A) Representative images of LC3+ neurons in the hippocampus of DKA brains and control cases. Scale bar=20 μm. (B) Percentage of LC3+ immunostaining neurons in the indicated areas of DKA and control cases. Error bars indicate +/−SD. (**) P<0.001 (C) Quantification of LC3+ fluorescence intensity in the gray and white matter of DKA brains. Data represent average±SD of five chosen microscopic fields per section at 10× magnification.

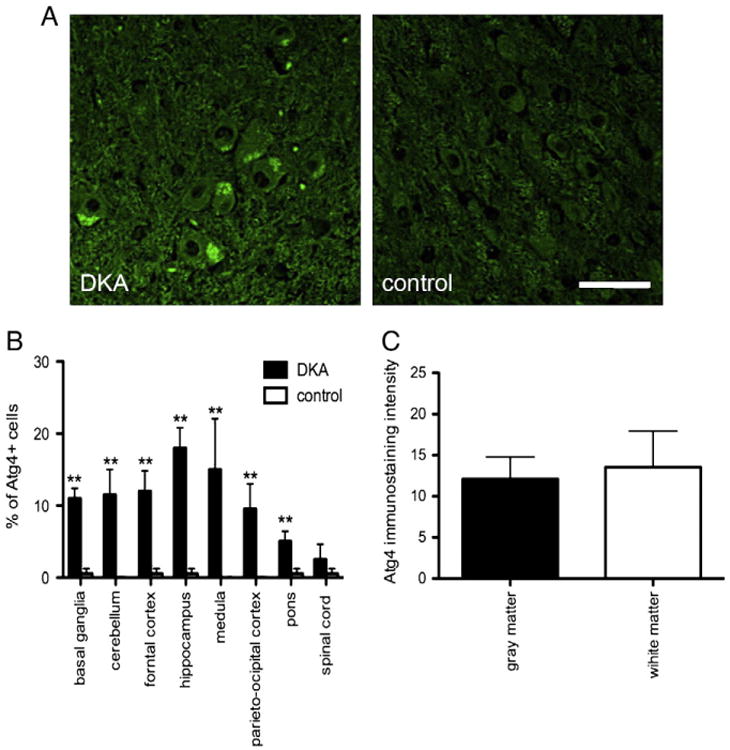

The Atg4 family of cysteine proteases plays an important role in regulation of autophagosome formation and degradation. Oxidative stress is considered a potent regulator of Atg4 expression. Thus we analyzed expression of Atg4. Atg4 had patterns of distribution and levels similar to LC3 in the neurons of the observed areas (Figs. 3A, B). There were slightly higher numbers of Atg4+ microglial cells than for LC3+ in the DKA cases (data not shown). In the DKA cases Atg4 was only sporadically present in astrocytes. Analysis of gray and white matter also showed similar levels of expression of Atg4 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

(A) Representative images of Atg4+ neurons in the hippocampus of DKA brains and control cases. Scale bar=20 μm. (B) Percentage of Atg4+ immunostaing neurons in the indicated areas of DKA and control cases. Error bars indicate +/−SD. (**) P<0.001 (C) Quantification of Atg4+ fluorescence intensity in the gray and white matter of DKA brains. Data represent average±SD of five chosen microscopic fields per section at 10× magnification.

Cleaved caspase-3 in neurons

To determine if apoptosis played a role in the regulation of neuronal cell death in poorly controlled T1DM and was relevant to the observed alterations in markers of ER stress and autophagy, cleaved caspase-3 immunoreactivity was assessed. Cleaved caspase-3 positive neuronal cells were very rare in brains of DKA cases numbers of which were not different from controls (data not shown). Thus apoptosis, at least that driven by caspase-dependent mechanisms, does not appear to play an important role in regulating neuron death in DKA nor associated with the alterations in autophagy observed in the DKA brains.

Discussion

Increased levels of LC3 and Atg4 in the brains of young patients with T1DM and chronic poor metabolic control are in agreement with the potential oxidative stress-induced alteration in macroautophagy and enhanced levels of GRP78 that implicate changes in both macroautophagy and CMA (Kiffin et al., 2006). The disrupted metabolic control in DKA results in numerous aberrant nutrient, hormone and metabolic signals that could induce autophagy. Specific candidates for induction and stimulation of autophagy include: insulin deficiency/resistance (Barrett et al., 1982; Evans et al., 2005; Hoffman et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2008); deficiency of insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and insulin growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) (Bains et al., 2011; Cinaz et al., 1996; Hoffman et al., 2010); hyperglucagonemia (Schworer and Mortimore, 1979); and hyperglycemia (Liu et al., 2010). Based on the expression of 8OHG and NT (Greenacre and Ischiropoulos, 2001; Hoffman et al., 2011; Nunomura et al., 2006) other candidates for perturbation of autophagy include: alteration of protein synthesis and degradation (Ding et al., 2007) due to the oxidative stress of RNA (Castellani et al., 2008; Hoffman et al., 2011), protein damage, altered lipid metabolism (Decsi et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2007; Singh et al., 2009); increased production of ketones and aldehydes (Finn and Dice, 2005; Hill et al., 2008; Wood et al., 2006) and lipid peroxidation (Hoffman et al., 2011; Kostolanska et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2002; Muller et al., 2011).

An adverse impact of the metabolic milieu on susceptible long-lived, post-mitotic neurons is strengthened considering that with a normal metabolic state, mild oxidative stress gradually results in increased lysosomal burden with the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates, damaged organelles and further oxidative stress (Brunk and Terman, 2002). This stress results in the gradual impairment of neuronal function, decreased production of ATP, and possible cell death (Terman et al., 2007). It is important to recognize that HSP70, a stabilizer of protein metabolism, is diffusely expressed in DKA/BE (Hoffman et al., 2007) and is increased systemically prior to treatment of severe uncomplicated (without BE) DKA (Oglesbee et al., 2005). Thus HSP70 could provide protection against the oxidative stress during normal metabolism and lysosomal membrane permeabilization (Nylandsted et al., 2004) such as occurs in retinal pigment epithelial cells in macular degeneration (Kaamiranta et al., 2009).

Results of IHC indicate increased LC3 immunoreactivity, suggesting an alteration in the autophagy-lysosome pathway in poorly controlled T1DM. These findings are complemented by a correlative increase in Atg4 immunoreactivity, which indicates an enhancement of autophagy induction. While at present we are limited in the manner in which our specimens are processed to further assess the more biochemical nature of autophagy dysfunction, our data clearly indicate an alteration in the autophagy-lysosome pathway that suggests induction of autophagy. We appreciate that LC3 IHC cannot definitely delineate the accumulation of autophagic vacuoles, as antibodies used to detect LC3 recognize both cytosolic LC3-I as well as the autophagic vacuole-associated LC3-II (Kabeya et al., 2000). Furthermore, studies of autophagic flux would be required to assess whether accumulation of autophagic vacuoles occurs as a result of nascent autophagic vacuole formation, or as a result of lysosome dysfunction (Klionsky et al., 2008). Regardless, the metabolic instability and negative nitrogen balance in T1DM, even without DKA (Mordier et al., 2000; Umpleby et al., 1986), suggest that alterations in macroautophagy induction are occurring and further studies are warranted to validate the manner in which macroautophagy is altered. Examples of the significant catabolism in DKA and potential impact on autophagy include: a transient decrease in numerous amino acids during severe uncomplicated DKA (Carl et al., 2002) with arginine deprivation inhibiting the mammalian target rapamycin (mTOR), a regulator of autophagy and possible stimulation (Savaraj et al., 2010). In contrast, glutamine which is also decreased during DKA and its treatment (Carl et al., 2002) has a direct relationship with autophagy (Nicklin et al., 2009) that could transiently impair autophagy. In addition to the decrease of the antioxidant vitamins A and C, during DKA (Lee et al., 2002), the depletion of cysteine and glycine (Carl et al., 2002) two of the three amino acids that make up glutathione, a primary antioxidant that is depleted in poorly controlled T1DM (Darmaun et al., 2005) results in further increases of oxidative stress that may contribute to autophagic induction.

A protective role for autophagy cannot be ruled out (Vanhorebeek et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2008). However, dysfuntional autophagy due to both chronic poor control and the acute metabolic instability of DKA is supported by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) reports of neuronal injury/deficits in young patients with poorly controlled T1DM (Makimattila et al., 2004; Sarac et al., 2005) unrelated to DKA. MRS has also identified transient neuronal injury during the acute insult of DKA and its treatment (Wootton-Gorges et al., 2007). The regions of neuronal insult demonstrated by MRS correlate well with the regions of immunocytochemical (ICC) markers of oxidative/nitrosative stress and the decreased neuronal density in the fatal DKA/BE (Hoffman et al., 2008, 2010, 2011). LC3, Atg-4 and GRP78 immunoreactivity is greatest in the hippocampus, the region that exhibits significant elevations in NT (Hoffman et al., 2010) and 8OHG (Hoffman et al., 2011) and the greatest neuronal deficit (Hoffman et al., 2008), as well as the region exhibiting maximal down-regulation of IGF-1R and insulin receptors (IR) (Hoffman et al., 2010). In contrast, immunoreactivity of autophagy markers was comparatively low in the cerebellum. This is in keeping with no decrease in Purkinje cell density and only minimal decreases of insulin growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and insulin receptors in DKA/BE (Hoffman et al., 2008). This preserved histology agrees with the report by Bains et al. (2009)that IGF-1 protects Purkinje neurons from autophagic death.

Cell death independent of the caspases is well recognized (Kroemer and Martin, 2005), and therefore the lack of expression of cleaved caspase-3 and other markers of the energy-dependent apoptotic pathway including mitochondrial DNA deletion (mtDNA) (Hoffman et al., 2006, 2011), does not rule out the contribution of caspase-independent apoptosis or other forms of cell death. Distinct temporal (Newcomb et al., 1999) and regional (Conti et al., 1998) apoptotic patterns have been reported in acute experimental traumatic brain injury. However, only the rare expression of cleaved caspase-3 in these DKA cases is in agreement with previous studies suggesting a lesser role for apoptosis (Hoffman et al., 2006, 2011) as a mechanism of chronic or acute neuronal loss, and also against apoptosis mediating ensuing cell death (Newcomb et al., 1999). Support for a limited role of apoptosis includes: 1) inhibition by polyunsaturated fatty acids (Kim et al., 2001); 2) a negative regulator effect by the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) (Kang et al., 2011), which is robustly expressed in the BE/DKA (Hoffman et al., 2008); 3) blockage of ER stress-induced apoptosis by complexes formed between GRP78 with caspase 7 and 12 (Rao et al., 2002); 4) an anti-apoptotic effect by HSP70 (Beere, 2005); 5) crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis that could result in down regulation of apoptosis (Boya et al., 2005); and 6) preferential UPR activation of autophagy similar to Alzheimer disease (AD) (Scheper et al., 2011). Also, Zhu et al. (2006) have reported apoptosis to be a mathematical improbability in AD.

It is important to note that although not statistically significant, when areas of white matter were analyzed together there were increased levels of Atg-4 and LC3 immunoreactivity and equal levels of GRP78 in comparison to that observed in gray matter. The finding of significant expression of autophagic markers in both white and gray matter is in keeping with structural deficits in young patients with T1DM (Wessels et al., 2007; Aye et al., 2011) and the white matter atrophy in the frontal and temporal regions in these DKA cases (Hoffman et al., 2010). The increase of autophagy in white matter is consistent with the leukoencephalopathy, and activation of RAGE in a long-term diabetic mouse model and the neuroradiologic white matter injury in humans with T1DM (Toth et al., 2006).

This study demonstrates that autophagy is increased in the brains of young T1DM patients with chronic poor metabolic control and increased oxidative stress. Further study is needed on the relationship between autophagy and the pathogenesis of early onset diabetic encephalopathy in T1DM.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Andjelkovic is supported by grant (AVA) NIH RO1 NS 062853. Dr. Shacka is supported by a VA Merit Review Award (1 101 BX000957-01) and acknowledges the Neuroscience Molecular Detection Core (P30 NS47466; Kevin Roth, MD, PhD, Director). The authors also acknowledge the critical review of Dr. M.F. Casanova.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors have no actual or potential conflict of interests.

References

- Aye T, Reiss AL, Kesler S, Hoang S, Drobny J, Park Y, Schleifer K, Baumgartner H, Wilson DM, Buckingham BA. The feasibility of detecting neuropsychologic and neuroanatomic effects of type 1 diabetes in young children. Diabetes Care. 2011;7(34):1458–1462. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains M, Florez-McClure ML, Heidenreich KA. Insulin-like growth factor-1 prevents the accumulation of autophagic vesicles and cell death in Purkinje neurons by increasing the rate of autopgagosome-to-lysosome fusion and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(30):20398–20407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.011791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bains M, Zaegel V, Mize-Berge J, Heidenreich KA. IGF-1 stimulates Rab7-RILP interaction during neuronal autophagy. Neurosci Lett. 2011;488(2):112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett EJ, DeFronzo RA, Bevilacqua S, Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance in diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes. 1982;31(10):923–928. doi: 10.2337/diab.31.10.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beere HM. Death versus survival: functional interaction between the apoptotic and stress-inducible heat shock protein pathways. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(10):2633–2639. doi: 10.1172/JCI26471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernales S, McDonald KL, Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;4(12):e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boya P, Gonzalez-Polo RA, Casares N, Perfettini JL, Dessen P, Larochette N, Metivier D, Meley D, Souquere S, Yoshimori T, Pierron G, Codogno P, Kroemer G. Inhibition of macroautophagy triggers apotosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(3):1025–1040. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.1025-1040.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunk UT, Terman A. The mitochondrial-lysosomal axis theory of aging: accumulation of damaged mitochondria as a result of impergect autophagocytosis. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1996–2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carl GF, Hoffman WH, Blankenship PR, Litaker MS, Hoffman MG, Mabe PA. Diabetic ketoacidosis depletes plasma tryptophan. Endocr Res. 2002;28(1&2):91–102. doi: 10.1081/erc-120004541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadesus G, Moreira PI, Nunomura A, Siedlak SL, Bligh-Glover W, Bairaj E, Petot G, Smith MA, Perry G. Indicies of metabolic function and oxidative stress. Neurochem Res. 2007;32(4–5):717–722. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9296-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellani RJ, Nunomura A, Rolston RK, Moreira PI, Takeda A, Perry G, Smith MA. Sublethal RNA oxidation as a mechanism for neurodegenerative disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9(5):789–806. doi: 10.3390/ijms9050789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceriello A. Oxidative stress and diabetes-associated complications. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(Suppl. 1):60–62. doi: 10.4158/EP.12.S1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherra SJ, Chu CT. Autophagy in neuroprotection and neurodegeneration: a question of balance. Future Neurol. 2008;3(3):309–323. doi: 10.2217/14796708.3.3.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinaz P, Kendirci M, Kurtoglu S, Gokcora N, Buyan N, Yavuz I, Demir A. Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1996;9(4):475–482. doi: 10.1515/jpem.1996.9.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RSB, Bayir H, Chu CT, Alber SM, Kochanek PM, Watkins SC. Autophagy is increased in mice after traumatic brain injury and is detectable in human brain after trauma and critical illness. Autophagy. 2008;4(1):88–90. doi: 10.4161/auto.5173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti AC, Raghupathi R, Trojanowski JQ, McIntosh TK. Experimental brain injury induces regionally distinct apoptosis during the acute and delayed post-traumatic period. J Neurosci. 1998;18(15):5663–5672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-15-05663.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM. Autophagy: many paths to the same end. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;263(1–2):55–72. doi: 10.1023/B:MCBI.0000041848.57020.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: selectivity pays off. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(3):142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cybulsky AV, Takano T, Papillon J, Khadir A, Liu J, Peng H. Complement C5b-9 membrane attack complex increases expression of endoplasmic reticulum stress proteins in glomerular epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(44):41342–41351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton RR, Hoffman WH, Passmore GG, Martin SL. Plasma C-reactive protein levels in severe diabetic ketoacidosis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2003;33:435–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmaun D, Smith SD, Sweeten S, Sager BK, Welch S, Mauras N. Evidence for accelerated rates of glutathione utilization and glutathione depletion in adolescents with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(1):190–196. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decsi T, Szabo E, Kozari A, Erhardt E, Marosvolgyi T, Soltesz G. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in plasma lipids of diabetic children during and after diabetic ketoacidosis. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(7):850–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Q, Dimayuga E, Keller JN. Oxidative stress alters neuronal RNA-and protein-synthesis: implications for neuronal viability. Free Radic Res. 2007;41(8):903–910. doi: 10.1080/10715760701416996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte AI, Proenca T, Oliveira CR, Santos MS, Rego AC. Insulin restores metabolic function in cultured cortical neurons subjected to oxidative stress. Diabetes. 2006;55(10):2863–2870. doi: 10.2337/db06-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edge JA, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, Dunger DB. The risk and outcome of cerebral oedema developing during diabetic ketoacidosis. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:16–22. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito K, Nappo F, Marfella R, Giugliano G, Giugliano F, Ciotola M, Quagliaro L, Ceriello A, Giugliano D. Inflammatory cytokines concentrations are acutely increased by hyperglycemia in humans: role of oxidative stress. Circulation. 2002;106(16):2067–2072. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000034509.14906.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JL, Maddux BA, Goldfine ID. The molecular basis for oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7(7–8):1040–1052. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro E, Cecconi F. Autophagic and apoptotic response to stress signals in mammalian cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;462(2):210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PF, Dice JF. Ketone bodies stimulate chaperone mediated autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(27):25864–25870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores L, Rodela S, Abian J, Claria J, Esmatjes E. F2 isoprostane is already increased at the onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus: effect of glycemic control. Metabolism. 2004;53(9):1118–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fribley A, Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. Regulation of apoptosis by the unfolded protein response. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;559:191–204. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-017-5_14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser N, Barnett P, McCaslin I, Nelson D, Trainor J, Louie J, Kaufman F, Quayle K, Roback M, Malley R, Kuppermann N The Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Pediatric Society. Risk factors for cerebral edema in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(4):264–269. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101253440404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogitidze JN, Hedrington MS, Briscoe VJ, Tate DB, Ertl AC, Davis SN. Effects of acute hypoglycemia on inflammatory and pro-atherothrombotic biomarkers in individuals with type 1 diabetes and healthy individuals. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1529–1535. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenacre SA, Ischiropoulos H. Tyrosine nitration: localization, quantification, consequences for protein function and signal transduction. Free Radic Res. 2001;34(6):541–581. doi: 10.1080/10715760100300471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill BG, Haberzetti P, Ahmed Y, Srivastava S, Bhatnagar A. Unsaturated lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes activate autophagy in vascular smooth-muscle cells. Biochem J. 2008;410(3):525–534. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitomi J, Katayama T, Taniguchi M, Honda A, Imaizumi K, Tohyama M. Apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress depends on activation of caspase-3 via caspase-12. Neurosci Lett. 2004;357(4):127–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.12.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Steinhart CM, el Gammal T, Steele S, Cuadrado AR, Morse PK. Cranial CT in children and adolescents with diabetic ketoacidosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1988;9(4):733–739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Kappler F, Passmore GG, Mehta R. Diabetic ketoacidosis and its treatment increase plasma 3-deoxyglucosone. Clin Biochem. 2003a;36(4):269–273. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(03)00030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Burek CL, Waller JL, Fisher LE, Khichi M, Mellick LB. Cytokine response to diabetic ketoacidosis and its treatment. Clin Immunol. 2003b;108(3):175–181. doi: 10.1016/s1521-6616(03)00144-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Cudrici CD, Zakranskaia E, Rus H. Complement activation in diabetic ketoacidotic brains. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006;80(3):283–288. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Casanova MF, Cudrici CD, Zakranskaia E, Venugopalan R, Nag S, Oglesbee MJ, Rus H. Neuroinflammatory response of the choroid plexus epithelium in fatal diabetic ketoacidosis. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007;83(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Artlett CM, Zhang W, Kreipke CW, Passmore GG, Rafols JA, Sima AA. Receptor for advanced glycation end products and neuronal deficit in the fatal brain edema of diabetic ketoacidosis. Brain Res. 2008;1238:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Stamatovic SM, Andjelkovic AV. Inflammatory mediators and blood brain barrier disruption in fatal brain edema of diabetic ketoacidosis. Brain Res. 2009;1254:138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Andjelkovic AV, Zhang W, Passmore GG, Sima AA. Insulin and IGF-1 receptors and cerebral neuronal deficits in two young patients with diabetic ketoacidosis and fatal brain edema. Brain Res. 2010;1343:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman WH, Siedlak SL, Wang Y, Castellani RJ, Smith MA. Oxidative damage is present in the fatal brain edema of diabetic ketoacidosis. Brain Res. 2011;1369:194–202. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.10.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoozemans JJ, Veerhuis R, Van Haastert ES, Rozemuller JM, Baas F, Eikelenboom P, Scheper W. The unfolded protein response is activated in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110(2):165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikesugi K, Mulhern ML, Madson CJ, Hosoya K, Terasaki T, Kador PF, Shinohara T. Induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in retinal pericytes by glucose deprivation. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31(11):947–953. doi: 10.1080/02713680600966785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagi R. Inhibitors of advanced glycation and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Methods Enzymol. 2011;491:361–380. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385928-0.00020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain SK, McVie R, Bocchini JA., Jr Hyperketonemia (ketosis), oxidative stress and type 1 diabetes. Pathophysiology. 2006;13:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pathophys.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerath RS, Burek CL, Hoffman WH, Passmore GG. Complement activation in diabetic ketoacidosis and its treatment. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaamiranta K, Salminen A, Eskelinen EL, Kopitz J. Heat shock proteins as gatekeepers of proteolytic pathways-Implications for age-related macular degeneration (AMD) Ageing Res Rev. 2009;8(2):128–139. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19(21):5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang R, Tang D, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ., III RAGE regulates autophagy and apoptosis following oxidative injury. Autophagy. 2011;7(4):442–444. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.4.14681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik S, Massey AC, Mizushima N, Cuervo AM. Constitutive activation of chaperone-mediated autophagy in cells with impaired macroautophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19(5):2179–2192. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-11-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik S, Singh R, Cuervo AM. Autophagic pathways and metabolic stress. 2010;(Suppl. 2):4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiffin R, Bandyopadhyay U, Cuervo AM. Oxidative stress and autophagy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8(1–2):152–162. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HY, Akbar M, Kim HY. Inhibition of neuronal apoptosisby polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;16(2–3):223–227. doi: 10.1385/JMN:16:2-3:223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DS, Jeong SK, Kim HR, Kim DS, Chae SW, Chae HJ. Effects of triglycerides on ER stress and insulin resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363(1):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev DS, Askew DS, Baba M, Baehrecke EH, Bahr BA, Ballabio A. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy. 2008;4(2):151–175. doi: 10.4161/auto.5338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostolanska J, Jakus V, Barak L. Glycation and lipid peroxidation in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus with and without diabetic complications. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;22(7):635–643. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2009.22.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroemer G, Martin SJ. Caspase-independent cell death. Nat Med. 2005;11(7):725–730. doi: 10.1038/nm1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DM, Hoffman WH, Carl GF, Khichi M, Cornwell PE. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant vitamins prior to, during, and after correction of diabetic ketoacidosis. J Diabetes Complications. 2002;16:294–300. doi: 10.1016/s1056-8727(01)00215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZG, Zhang W, Grunberger G, Sima AAF. Hippocampal neuronal apoptosis in type 1 diabetes. Brain Res. 2002;946:221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02887-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ni M, Lee B, Barron E, Hinton DR, Lee AS. The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP is required for endoplasmic reticulum integrity and stress-induced autophagy in mammalian cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(9):1460–1471. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Spellberg B, Phan QT, Fu Y, Fu Y, Lee AS, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG, Ibrahim AS. The endothelial cell receptor GRP78 is required for mucormycosis pathogenesis in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):1914–1924. doi: 10.1172/JCI42164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(9):741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makimattila S, Malmberg-Cedar K, Hakkinen AM, Vuori K, Salonen O, Summanen P, Yki-Jarvinen H, Kaste M, Heikkinen S, Lundbom N, Roine RO. Brain metabolic alterations in patients with type 1 diabetes-hyperglycemia-induced injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:1393–1399. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000143700.15489.B2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandl J, Meszaros T, Banhegyi G, Hunyady L, Csala M. Endoplasmic reticulum: nutrient sensor in physiology and pathology. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20(4):194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44(235):291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey AC, Follenzi A, Kiffin R, Zhang C, Cuervo AM. Early cellular changes after blockage of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Autophagy. 2008;4:442–456. doi: 10.4161/auto.5654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrpour M, Esclatine A, Beau I, Codogno P. Autophagy in health and disease. 1 Regulation and significance of autophagy: an overview. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298(4):C776–C785. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00507.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordier S, Deval C, Bechet D, Tassa A, Ferrara M. Leucine limitation induces autophagy and activation of lysosome-dependent proteolysis in C2C12 myotubes through a mammalian target of rapamycin-independent signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(38):29900–29906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C, Salvayre R, Negre-Salvayre A, Vindis C. HDLs inhibit endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagic response induced by oxidized LDLs. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18(5):817–828. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb JK, Zhao X, Pike BR, Hayes RL. Temporal profile of apoptotic-like changes in neurons and astrocytes following controlled cortical impact injury in the rat. Exp Neurol. 1999;158(1):76–88. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklin P, Bergman P, Zhang B, Triantafellow E, Nyfeler B, Yang H, Hild M, Kung C, Wilson C, Myer VE, MacKeigan JP, Porter JA, Wang YK, Cantley LC, Finan PM, Murphy LO. Bidirectional transport of amino acids reulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell. 2009;136(3):521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijholt DA, de Graaf TR, van Haastert ES, Oliveira AO, Berkers CR, Zwart R, Ovaa H, Baas F, Hoozemans JJ, Scheper W. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates autophagy but not the proteasome in neuronal cells: implications for Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18(6):1071–1081. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunomura A, Honda K, Takeda A, Hirai K, Zhu X, Smith MA, Perry G. Oxidative damage to RNA in neurodegenerative diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006:1–6. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/82323. ID 82323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylandsted J, Gyrd-Hansen M, Danielewicz A, Fehrenbacher N, Ladermann U, Hoyer-Hansen M, Weber E, Multhoff G, Rohde M, Jaattela M. Heat shock protein 70 promotes cell survival by inhibiting lysosomal membrane permeabilization. J Exp Med. 2004;200(4):425–435. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oglesbee MJ, Herdman AV, Passmore GG, Hoffman WH. Diabetic ketoacidosis increases extracellular levels of the major inducible 70-kDa heat shock protein. Clin Biochem. 2005;38:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineau L, Colas J, Dupont S, Beney L, Fleurat-Lessard P, Berjeaud JM, Berges T, Ferreira T. Lipid-induced ER stress: synergistic effects of sterols and saturated fatty acids. Traffic. 2009;10(6):673–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivtoraiko VN, Stone SL, Roth KA, Shacka JJ. Oxidative stress and autophagy in the regulation of lysosomal-dependent neuron death. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(3):481–496. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghubir R, Nakka VP, Mehta SL. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in brain damage. Methods Enzymol. 2011;489:259–275. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385116-1.00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RV, Peel A, Logvinova A, del Rio G, Hermel E, Yokota T, Goldsmith PC, Ellerby LM, Ellerby HM, Bredesen DE. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program: role of the ER chaperone GRP78. FEBS Lett. 2002;514(2–3):122–128. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02289-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, Massey DC, Menzies FM, Moreau K, Narayanan U, Renna M, Siddiqi FH, Underwood BR, Winslow AR, Rubinsztein DC. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(4):1383–1435. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadasivan S, Dunn WA, Hayes RL, Wang KK. Changes in autophagy proteins in a rat model of controlled cortical impact induced brain injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373(4):476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarac K, Akinci A, Alkan A, Aslan M, Baysal T, Ozcan C. Brain metabolite changes on proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in children with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes mellitus. Neuroradiology. 2005;47:562–565. doi: 10.1007/s00234-005-1387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savaraj N, You M, Wu C, Wangpaichitr M, Kuo MT, Feun LG. Arginine deprivation, autophagy, apoptosis (AAA) for the treatment of melanoma. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10(4):405–412. doi: 10.2174/156652410791316995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayre LM, Perry G, Smith MA. Oxidative stress and neurotoxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:172–188. doi: 10.1021/tx700210j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper W, Nijholt DA, Hoozemans JJ. The unfolded protein response and proteostasis in Alzheimer disease: preferential activation of autophagy by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Autophagy. 2011;7 doi: 10.4161/auto.7.8.15761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherz-Shouval R, Shvets E, Fass E, Shorer H, Gil L, Elazar Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 2007;26(7):1749–1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid D, Munz C. Innate and adaptive immunity through autophagy. Immunity. 2007;27(1):11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schworer CM, Mortimore GE. Glucagon-induced autophagy and proteolysis in rat liver: mediation by selective deprivation of intracellular amino acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:3169–3173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh-Ali M, Sultan S, Alamir AR, Haas MJ, Mooradian AD. Hyperglycemia-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress in endothelial cells. Nutrition. 2010;26(11-12):1146–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sima AA, Li ZG. The effect of C-peptide on cognitive dysfunction and hippocampal apoptosis in type 1 diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2005;54:1497–1505. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.5.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P, Jain A, Kaur G. Impact of hypoglycemia and diabetes on CNS: correlation of mitochondrial oxidative stress with DNA damage. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;260(1-2):153–159. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000026067.08356.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1131–1135. doi: 10.1038/nature07976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sosa L, Dupraz S, Laurino L, Bollali F, Bisbal M, Caceres A, Pfenninger KH, Quiroga S. IGF-1 receptor is essential for the establishment of hippocampal neuronal polarity. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(8):993–995. doi: 10.1038/nn1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS. Caspases-controlling intracellular signals by protease zymogen activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477(1-2):299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00281-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szegezdi E, Logue SE, Gorman AM, Samali A. Mediators of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(9):880–885. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S, Wood M, Maher P. Oxidative stress induces a form of programmed cell death with characteristics of both apoptosis and necrosis in neuronal cells. J Neurochem. 1998;71:95–105. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanida J, Ueno T, Kominami E. LC3 and autophagy. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;445:77–88. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-157-4_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terman A, Gustafsson B, Brunk UT. Autophagy, organelles and aging. J Pathol. 2007;211(2):134–143. doi: 10.1002/path.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth C, Schmidt AM, Tuor UI, Francis G, Foniok T, Brussee V, Kaur J, Yan SF, Martinez JA, Barber PA, Buchan A, Zochodne DW. Diabetes, leukoencephalopathy and rage. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;23(2):445–461. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk Z, Nemet I, Varga-Defteardarovic L, Car N. Elevated level of methylglyoxal during diabetic ketoacidosis and its recovery phase. Diabetes Metab. 2006;32:176–180. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umpleby AM, Boroujerdi MA, Brown PM, Carson ER, Sonksen PH. The effect of metabolic control on leucine metabolism in type 1 (insulin dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 1986;29(3):131–141. doi: 10.1007/BF02427082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhorebeek I, Gunst J, Derde S, Derese I, Boussemaere M, Guiza F, Martinet W, Timmermans JP, D'Hoore A, Wouters PJ, Van den Berghe G. Insufficient activation of autophagy allows cellular damage to accumulate in critically ill patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(4):E 633–E 645. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels AM, Rombouts SA, Remijnse PL, Boom Y, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Heine RJ, Snoek FJ. Cognitive performance in type1 diabetes patients is associated with cerebral white matter volume. Diabetologia. 2007;50(8):1763–1769. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0714-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PL, Khan MA, Kulow SR, MahMood SA, Moskal JR. Neurotoxicity of reactive aldehydes: the concept of “aldehyde load” as demonstrated by neuroprtection with hydroxylamines. Brain Res. 2006;1095(1):190–199. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wootton-Gorges SL, Buonocore MH, Kuppermann N, Marcin JP, Barnes PD, Neely EK, DiCarlo J, McCarthy T, Glaser NS. Cerebral proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in children with diabetic ketoacidosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:895–899. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SW, Baek SH, Brennan RT, Bradley CJ, Park SK, Lee YS, Jun EJ, Lookingland KJ, Kim EK, Lee H, Goudreau JL, Kim SW. Autophagic death of adult hippocampal neural stem cells following insulin withdrawal. Stem Cells. 2008;26(10):2602–2610. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Kaufman RJ. The unfolded protein response: a stress signaling pathway critical for health and disease. Neurology. 2006;66(2 Suppl. 1):S102–S109. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000192306.98198.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YB, Li SX, Chen XP, Yang L, Zhang YG, Liu R, Tao LY. Autophagy is activated and might protect neurons from degeneration after traumatic brain injury. Neurosci Bull. 2008;24(3):143–149. doi: 10.1007/s12264-008-1108-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Raina AK, Perry G, Smith MA. Apoptosis in Alzheimer disease: a mathematical improbability. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2006;3(4):393–396. doi: 10.2174/156720506778249470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]