Seasonal variation in fatal pulmonary embolism has been well documented by at least 23 reports comprising nearly 11 000 cases.1 Evidence is lacking, however, for seasonal variation in deep vein thrombosis—the only large hospital series available did not establish significant variation.2 We analysed hospital admissions for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in France over four years.

Methods and results

We reviewed all cases with a discharge diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism entered on the national hospital discharge register between 1995 and 1998. We used the international classification of diseases, ninth and 10th revisions (deep vein thrombosis: ICD-9 codes 451.1 and 451.2 and ICD-10 codes I80.1 and I80.2; pulmonary embolism: ICD-9 code 415.1 and ICD-10 codes I26.0 and I26.9). This dataset is a collection of all discharges from public and non-profit making, short stay, or acute hospitals in France (71% of hospital capacity). We included discharge data if the usual confirmatory tests—or specific fibrinolytic or surgical therapy—were mentioned. Usual confirmatory tests were venography or Doppler ultrasonography for deep vein thrombosis and a ventilation and perfusion lung scan, helicoidal computed tomography, or pulmonary angiography for pulmonary embolism.

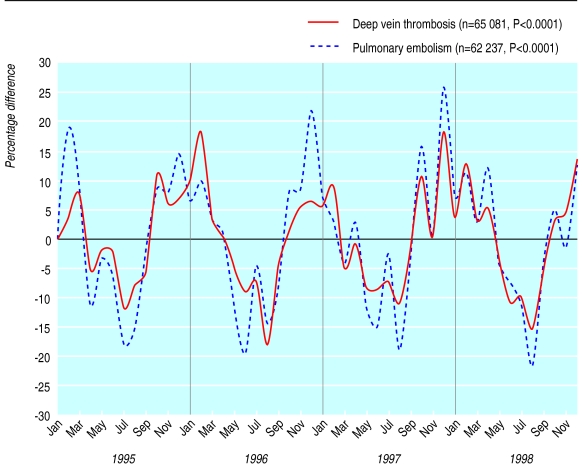

The figure shows monthly data on admissions to hospital for deep vein thrombosis (n=65 081, median age 69 years, 58% women, 95% medical patients) and pulmonary embolism (n=62 237, median age 68 years, 57% women, 96% medical patients), presented as percentages above or below the average monthly value for each year of the study, the sum of monthly variations being 0.

The number of admissions per month was significantly higher in winter and lower in summer for both deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (Roger's test3: P<0.0001). Mean monthly admissions for deep vein thrombosis (1356 (SD 450)) ranged from 18% below average in August 1996 to 18% above average in February 1996 and December 1997. Mean monthly admissions for pulmonary embolism (1297 (SD 268)) ranged from 22% below average in August 1998 to 26% above average in December 1997.

The same winter predominance was observed for cases of deep vein thrombosis without confirmatory tests (n=34 245); cases of deep vein thrombosis without pulmonary embolism (n=47 508); and subgroups of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism defined by age, sex, and surgical setting (data not shown).

Comment

Clear seasonal variations exist in admission to hospital for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Because the study was retrospective the accuracy of diagnosis might be questioned, but any bias would be minimal as only cases with documentary proof were selected. The fact that outpatient care—recently estimated to account for a third of cases of venous thromboembolism in a community based study in France4—was not considered could be another potential source of bias. Bias would be minimal, however, as there is no reason why the decision to admit patients to hospital with deep vein thrombosis should follow a seasonal pattern. The nationwide nature of this large database also limits any selection bias from seasonal variations in populations. The fact that similar patterns occurred in different subgroups and in the admissions data for both deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism also increases the credibility of these statistics.

The largest hospital series available (n=7303) did not show any seasonality in deep vein thrombosis.2 The authors hypothesised that the winter predominance of deaths from pulmonary embolism could be explained by associated comorbidities, which might contributeto a reduced tolerance to small emboli. Our finding that seasonal variation exists in hospital admissions for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism suggests that thrombogenic factors could involve a seasonal component. Vasoconstriction induced by the cold and reduced physical activity produce a well documented reduction in blood flow in the lower limbs. Except for hypercoagulability, which might be induced by winter respiratory tract infections,5 little is known about seasonal fluctuations in coagulation.

Figure.

Monthly percentage variations in French hospital admissions for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (0 represents the sum of monthly variations)

Acknowledgments

We thank the Direction des Hôpitaux du Ministère de la Santé and the Centre de Traitement de l'Information du PMSI (CTIP), which maintains the databases; Ms Marie Annie Burette, Drs Michel Arenaz and Max Bensadon, and Ms Cécile Landais for helping us with data from the national hospital discharge register (PMSI); and Ms Béatrice Boureux for typing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Allan TM, Douglas AS. Seasonal variation in deep vein thrombosis. BMJ. 1996;312:1227. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7040.1227a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bounameaux H, Hicklin L, Desmarais S. Seasonal variation in deep vein thrombosis. BMJ. 1996;312:284–285. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7026.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger JH. A significance test for cyclic trends in incidence data. Biometrika. 1977;64:152–155. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oger E. Incidence of venous thromboembolism: a community-based study in western France. EPI-GETBP Study Group. Groupe d'Etude de la Thrombose de Bretagne Occidentale. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2000;83:657–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodhouse PR, Khaw KT, Plummer M, Foley A, Meade TW. Seasonal variations of plasma fibrinogen and factor VII activity in the elderly: winter infections and death from cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 1994;343:435–439. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]