Abstract

Background and aims

Myeloperoxidase (MPO), a product of systemic inflammation, promotes oxidation of lipoproteins; whereas, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) exerts anti-oxidative effects in part via paraoxonase-1 (PON1). MPO induces dysfunctional HDL particles; however, the interaction of circulating levels of these measures in cardiovascular disease (CVD) has not been studied in humans. We tested whether serum levels of MPO indexed to HDL particle concentration (MPO/HDLp) are associated with increased CVD risk in a large multiethnic population sample, free of CVD at baseline.

Methods

Levels of MPO, HDL-C, and HDL particle concentration (HDLp) by NMR were measured at baseline in 2924 adults free of CVD. The associations of MPO/HDLp with incident ASCVD (first non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or CVD death) and total CVD were assessed in Cox proportional-hazards models adjusted for traditional risk factors. The median follow-up period was 9.4 years.

Results

Adjusted for sex and race/ethnicity, MPO/HDLp was associated directly with body mass index, smoking status, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, and interleukin 18, and inversely with age, HDL-C levels, HDL size, and PON1 arylesterase activity, but not with cholesterol efflux. In fully adjusted models, the highest versus lowest quartile of MPO/HDLp was associated with a 74% increase in incident ASCVD (aHR, 1.74, 95% CI 1.12–2.70) and a 91% increase in total incident CVD (aHR, 1.91, 95% CI 1.27–2.85).

Conclusions

Increased MPO indexed to HDL particle concentration (MPO/HDLp) at baseline is associated with increased risk of incident CVD events in a population initially free of CVD over the 9.4 year period.

Keywords: HDL particle concentration, paroxonase-1, myeloperoxidase, incident cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Inflammation and oxidative stress play a key role in the progression of atherosclerotic plaques and development of cardiovascular disease. Myeloperoxidase (MPO), expressed in the azurophilic granules of leukocytes, is released during states of increased inflammation and catalyzes the formation of several reactive species. MPO is enriched within advanced atherosclerotic lesions in humans,1 suggesting a role in atherosclerosis. In animal models, MPO has been shown to catalyze initiation of lipid peroxidation at sites of inflammation in vivo,2 and when incubated with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) in vitro.3 MPO also oxidizes high-density lipoprotein (HDL), rendering it dysfunctional.4,5 HDL-bound MPO retains its enzymatic activity, and MPO-dependent modification of HDL markedly increases the binding affinity of HDL for MPO, leading to a vicious cycle of MPO- dependent modifications at sites of chronic inflammation.6 Paraoxonase1 (PON1), on the other hand, prevents oxidation of lipids in lipoproteins, allowing HDL to exert atheroprotective and anti-inflammatory actions.7 PON1 promotes high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-mediated macrophage cholesterol efflux in in-vitro studies.8,9 In fact, MPO, PON1, and HDL have been shown to form a ternary complex, in which PON1 inhibits activity of MPO, and vice versa.10

Many clinical studies have reported a direct association of MPO with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and an inverse association of PON1 with ACS.11–17 However, PON1 arylesterase activity and circulating levels of MPO have inconsistent associations with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) in those without ACS16,18,19–22 Recently, the MPO/PON1 ratio was associated with atherosclerosis cross-sectionally.23 In the present study, we sought to investigate whether MPO indexed to HDL particle concentration, as an indicator of the oxidative potential of HDL, would be associated with incident ASCVD, independent of PON1 arylesterase activity. This is the first study to report an association between MPO/HDL particle ratio and cardiovascular outcomes in a large cohort of humans without baseline cardiovascular disease.

Materials and methods

Study population

The Dallas Heart Study is a multiethnic, probability-based population-representative cohort study of Dallas County residents, including intentional oversampling of Blacks to make up 50% of the cohort.24 Participants 30 to 65 years of age underwent fasting blood collection at baseline. We excluded individuals with a history of cardiovascular disease, defined as self-reported history of myocardial infarction, stroke, arterial revascularization, heart failure, or arrhythmia, those with niacin use, and those who died within 1 year of enrollment. We did not exclude participants with unknown subclinical disease. We included in our analysis 2924 out of a total 2971 enrolled participants.

Measurement of circulating markers

Blood was collected in EDTA tubes by venipuncture from all the participants at baseline, stored at 4°C for less than 4 hours, and centrifuged, and plasma was removed and stored at −70°C. All biomarkers reported here have been previously measured and the analytical methods described,24 including MPO, plasma lipids, serum PON1 activity,25,26 cholesterol efflux,27 Interleukin 18,28 high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP),24,29 asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA).30 MPO measurements were provided by Biosite, Inc. (now Alere, Inc., Waltham, MA).31 HDL particle sizes and concentrations were measured by NMR spectroscopy (LabCorp, formerly LipoScience, Inc., Raleigh, NC, USA).32 PON1 arylesterase activity was measured by cleavage of phenyl acetate resulting in phenol formation, measured in kU/L, based on the extinction coefficient of phenol.26 Cholesterol efflux capacity was assessed by measuring the efflux of fluorescence-labeled cholesterol from J774 macrophages to apolipoprotein B–depleted plasma in study participants, expressed as a percentage of efflux in the sample, normalized to a reference sample.27 All the analyzed data came from samples collected at baseline.

Clinical endpoints

The primary end point was a composite ASCVD outcome, defined as a first non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, coronary revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary-artery bypass grafting) or death from cardiovascular causes. A secondary end point, total cardiovascular disease, was defined as all the events included in the primary end point plus peripheral revascularization and hospitalization for heart failure or atrial fibrillation. All the events were adjudicated separately by two cardiologists from primary records, as described in our earlier study.33 The median follow-up period was 9.4 years.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic and clinical variables were compared across quartiles of MPO/HDLp with the use of the Jonckheere–Terpstra trend test.34 Correlations with continuous markers were assessed with the use of nonparametric Spearman coefficients. Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional-hazards models were used to assess the association between quartiles of the MPO/HDLp ratio and the time to a first event for both atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (the primary end point) and total cardiovascular disease (the secondary end point). Multivariable models included age, sex, race, presence or absence of diabetes, presence or absence of hypertension, current smoking, body mass index, total cholesterol level, log-transformed triglyceride level, and history of statin use. Models were serially adjusted for HDL-C, PON1 arylesterase activity, hs-CRP, IL-18, and BMI. Two-sided p values of 0.05 or less were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed with the use of SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

The median age of the participants at study entry was 42 years. A total of 57% of the participants were women and 49% Black. The median MPO levels and the median HDLp levels by sex and race/ethnicity are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO), total HDL particle concentration (HDLp) and cardiovascular events by sex and race/ethnicity.

| MPO (ng/mL)b | HDLp (µmol/L)b | Number of ASCVDc |

Number of total CVDd |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Blacks (n=1224)a | 17.5[13.9–22.1]g | 32.8 [28.9–37.3]h | 111 | 136 |

| Whites (n=830) | 15.8 [12.4–20.2]g | 33.5 [29.3–37.6]h | 38 | 49 |

| Hispanics (n=390) | 17.7 [13.9–21.6]g | 31.5 [27.9–35.7]h | 12 | 16 |

| Women (n=1411) | 17.0 [13.1–21.3]e | 33.7 [29.6–38.6]f | 64 | 87 |

| Blacks (n=732) | 17.6 [13.8–22.1] | 33.0 [29.2–37.9] | ||

| Whites (n=434) | 15.5 [12.1–20.4] | 35.4 [31.3–40.4] | ||

| Hispanics (n=228) | 18.1 [14.3–21.8] | 33.1 [28.7–36.8] | ||

| Men (n=1087) | 16.8 [13.4–21.1]e | 31.4 [28.0–35.3]f | 100 | 118 |

| Blacks (n=492) | 17.2 [14.2–22.1] | 32.3 [28.5–36.3] | ||

| Whites (n=396) | 16.1 [12.6–20.0] | 31.4 [28.0–35.0] | ||

| Hispanics (n=162) | 17.4 [13.4–21.3] | 30.2 [27.3–34.3] |

Number of participants in each category is denoted by n.

Median [interquartile range].

Number of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events defined as first non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or death from cardiovascular disease.

Number of total cardiovascular disease (CVD) events defined as first ASCVD event or hospitalization from heart failure or atrial fibrillation or peripheral arterial revascularization.

p-value = 0.82 for comparison by gender, derived using Kruskal-Wallis Test.

p-value < 0.0001 for comparison by gender, derived using Kruskal-Wallis Test.

p-value < 0.0001 for comparison across race groups, derived using Kruskal-Wallis Test.

p-value <0.0001 for comparison across race groups, derived using Kruskal-Wallis Test.

Association of MPO/HDLp with risk factors, lipids, and biomarkers of inflammation and HDL function

There was a 2.6-fold increase in median MPO/HDLp ratio across its 4 quartiles (Table 2) and an approximately 4-fold increase from the 5th to 95th percentile. Increasing MPO/HDLp was driven primarily by increases in MPO, with a small contribution from decreases in HDLp (Table 2). Increasing quartiles of MPO/HDLp were associated inversely with age and directly with body mass index (BMI) and the rate of smoking, but were not associated with other traditional risk factors (Table 3). In terms of lipoprotein composition, increasing MPO/HDLp was associated with decreased HDL-C and modestly with HDL size, but not with LDL-C or triglyceride levels (Table 2). MPO/HDLp was directly associated with high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and interleukin 18 (IL-18). In sex- and race-adjusted models, MPO/HDLp was strongly associated inversely with PON1 arylesterase activity (p<0.0001, Table 4) but not associated with cholesterol efflux (p=0.45, Table 4).

Table 2.

Lipids, biomarkers of inflammation, and HDL function by quartiles of the MPO/HDLp ratio.

| Q1 (n=609)a | Q2 (n=612) | Q3 (n=612) | Q4 (n=610) | p-trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPO/HDLp | 0.31(0.25, 0.37)b | 0.47(0.41, 0.53) | 0.58(0.51, 0.66) | 0.82(0.68, 1.02) | <0.0001 |

| MPO (ng/mL) | 10.9(9.1, 12.2) | 15.2(14.3, 16.0) | 18.8(17.8, 19.9) | 25.2(22.9, 30.4) | <0.0001 |

| HDLp (µmol/L) | 33.7(29.5–38.6) | 32.7(29.1–37.0) | 37.0 (29.1–36.9) | 32.1 (28.0–36.3)) | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 180(158–205) | 176(153, 200) | 177(153, 204) | 178(154, 204) | 0.36 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 108(85, 129) | 102(83, 125) | 103(82, 128) | 106(86, 129) | 0.96 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 97(68, 142) | 92(67, 142) | 95(67, 143) | 98 (67, 151) | 0.35 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 50(41–60) | 47(40, 58) | 48(40, 57) | 46(38, 55) | <0.0001 |

| HDL size (nm) | 9.0(8.7, 9.3) | 8.9(8.7, 9.3) | 9.0(8.7, 9.3) | 8.9(8.7, 9.3) | 0.014 |

| ADMA (µmol/L) | 0.47(0.41, 0.54) | 0.48(0.42, 0.55) | 0.48(0.42, 0.55) | 0.48(0.42, 0.56) | 0.16 |

| SDMA (µmol/L) | 0.40(0.35, 0.46) | 0.41(0.35, 0.47) | 0.40(0.35, 0.47) | 0.39(0.34, 0.47) | 0.25 |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 2.3(1.0, 5.4) | 2.4(1.0, 5.5) | 2.6(1.2, 6.4) | 4.0(1.6, 8.6) | <0.0001 |

| IL 18 (pg/mL) | 481(345, 718) | 482(332–702) | 533(348–779) | 547(379, 840) | 0.0013 |

MPO, myeloperoxidase; HDLp, high-density lipoproteins particle concentration; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level; PON1, serum paraoxonase/arylesterase1 activity; ADMA, asymmetric dimethylarginine; SDMA, symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA); Hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL-18, interleukin 18.

Quartiles are denoted by Q.

All continuous measures are reported as medians [IQR].

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics, risk factors, and cardiovascular events by quartiles of the MPO/HDLp ratio.

| Q1 (n=609)a | Q2 (n=612) | Q3 (n=612) | Q4 (n=610) | p-trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44 (37, 52)b | 43 (36, 51) | 43 (36, 51) | 43 (35, 52) | <0.017 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 (24, 31) | 28 (24, 33) | 29 (25, 34) | 29 (25, 35) | <0.0001 |

| Male (%) | 42c | 46 | 42 | 43 | 0.81 |

| Black (%) | 43 | 47 | 50 | 55 | <0.0001 |

| White (%) | 41 | 35 | 29 | 27 | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic (%) | 13 | 15 | 19 | 16 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 30 | 32 | 28 | 33 | 0.66 |

| Diabetes (%) | 7.7 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 0.061 |

| Smoker (%) | 23 | 25 | 26 | 34 | <0.0001 |

| Statin use (%) | 6.3 | 5.3 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 0.23 |

| ASCVDd (n/total) | 32/624 | 34/625 | 41/625 | 57/624 | 0.003 |

| Total CVDe (n/total) | 39/624 | 43/625 | 56/625 | 67/624 | 0.002 |

BMI, body mass index.

Quartiles are denoted by Q.

All continuous measures are reported as medians [IQR].

All categorical measures as percentages.

Number of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) events defined as first non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or death from cardiovascular disease.

Number of total cardiovascular disease (CVD) events defined as first ASCVD event or hospitalization from heart failure or atrial fibrillation or peripheral arterial revascularization.

Table 4.

Sex- and race-adjusted PON1 arylesterase activity and cholesterol efflux by quartiles of the MPO/HDLp ratio.

| Q1 (n=609)a | Q2 (n=612) | Q3 (n=612) | Q4 (n=610) | p-trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PON1 arylesterase (kU/L)c | 122.6 (97.9, 146.6)b | 117.2 (95.0,137.8) | 111.6 (91.3, 133.0) | 109.1 (85.7, 129.8) | <0.0001 |

| Cholesterol efflux (%)d | 0.99 (0.83, 1.19) | 1.00 (0.85, 1.19) | 1.01 (0.85, 1.18) | 0.99 (0.82, 1.17) | 0.45 |

PON1, serum paraoxonase/arylesterase1 activity.

Quartiles are denoted by Q.

All continuous measures are reported as medians [IQR].

One unit of PON1 arylesterase activity is equal to 1 µM of phenol formed per minute. The activity is expressed in kU/L.

Cholesterol efflux capacity is expressed as a percentage of efflux in the sample, normalized to a reference sample.

Association of MPO/HDLp with cardiovascular events

There were 164 ASCVD and 205 total CVD first events. Increasing quartiles of MPO alone modestly trended towards increasing risk of ASCVD and CVD, but no individual quartile comparisons to quartile 1 were significant in unadjusted or adjusted analyses (Tables 5 and 6). Similar findings were seen for MPO indexed to PON1 (MPO/PON1) and MPO indexed to HDL-C (MPO/HDL-C, Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Hazard ratiosa estimating the association of quartiles of MPO, MPO/HDL-C, and MPO/HDLp ratios and incident ASCVD.

| Q1 | Q2 | 95% CI | Q3 | 95% CI | Q4 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPO | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 0.97 | (0.61, 1.56) | 1.28 | (0.82, 1.99) | 1.48 | (0.96, 2.27) |

| Adjustedb | 1.0 | 0.93 | (0.58, 1.49) | 1.16 | (0.74, 1.81) | 1.29 | (0.83, 2.0) |

| MPO/PON1 | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 1.13 | (0.70, 1.80) | 1.27 | (0.81, 2.01) | 1.57 | (1.01, 2.43) |

| Adjusted | 1.0 | 1.05 | (0.66, 1.69) | 1.18 | (0.75, 1.88) | 1.46 | (0.92, 2.30) |

| MPO/HDL-C | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 0.78 | (0.49, 1.25) | 0.947 | (0.60, 1.49) | 1.49 | (0.99, 2.24) |

| Adjusted | 1.0 | 0.70 | (0.44, 1.13) | 0.914 | (0.58, 1.44) | 1.31 | (0.86, 1.99) |

| MPO/HDLp | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 0.93 | (0.58, 1.51) | 1.33 | (0.85, 2.08) | 1.63 | (1.06, 2.50) |

| Adjusted | 1.0 | 0.90 | (0.55, 1.46) | 1.35 | (0.86, 2.11) | 1.74 | (1.12, 2.70) |

MPO, myeloperoxidase; PON1, serum paraoxonase/arylesterase1 activity; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level; HDLp, high-density lipoproteins particle concentration.

From Cox proportional-hazards models assessing the association of each listed marker with incident ASCVD (first non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, coronary revascularization, or CVD death; n=164).

Cox models adjusted for traditional risk factors age, sex, race, hypertension, smoking, total cholesterol, and statin use.

Table 6.

Hazard ratiosa estimating the association of quartiles of MPO, MPO/HDL-C, and MPO/HDLp ratios and incident Total CVD.

| Q1 | Q2 | 95% CI | Q3 | 95% CI | Q4 | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPO | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 1.09 | (0.72, 1.65) | 1.27 | (0.86, 1.90) | 1.44 | (0.97, 2.13) |

| Adjustedb | 1.0 | 1.04 | (0.69, 1.58) | 1.19 | (0.79, 1.77) | 1.27 | (0.86, 1.89) |

| MPO/PON1 | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 1.05 | (0.69, 1.60) | 1.28 | (0.86, 1.91) | 1.45 | (0.98, 2.14) |

| Adjusted | 1.0 | 1.00 | (0.65, 1.52) | 1.17 | (0.78, 1.76) | 1.35 | (0.90, 2.03) |

| MPO/HDL-C | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 0.78 | (0.50, 1.19) | 1.11 | (0.75, 1.65) | 1.51 | (1.04, 2.19) |

| Adjusted | 1.0 | 0.71 | (0.44, 1.14) | 0.93 | (0.59, 1.47) | 1.33 | (0.87, 2.02) |

| MPO/HDLp | |||||||

| Unadjusted | 1.0 | 1.15 | (0.75, 1.77) | 1.45 | (0.97, 2.19) | 1.75 | (1.17, 2.60) |

| Adjusted | 1.0 | 1.13 | (0.73, 1.74) | 1.50 | (1.00, 2.26) | 1.91 | (1.27, 2.85) |

MPO, myeloperoxidase; PON1, serum paraoxonase/arylesterase1 activity; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level; HDLp, high-density lipoproteins particle concentration.

From Cox proportional-hazards models assessing the association of each listed marker with total CVD (first non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, coronary revascularization, CVD death, peripheral revascularization, and hospitalization for heart failure or atrial fibrillation; n=205).

Cox models adjusted for traditional risk factors age, sex, race, hypertension, smoking, total cholesterol, and statin use.

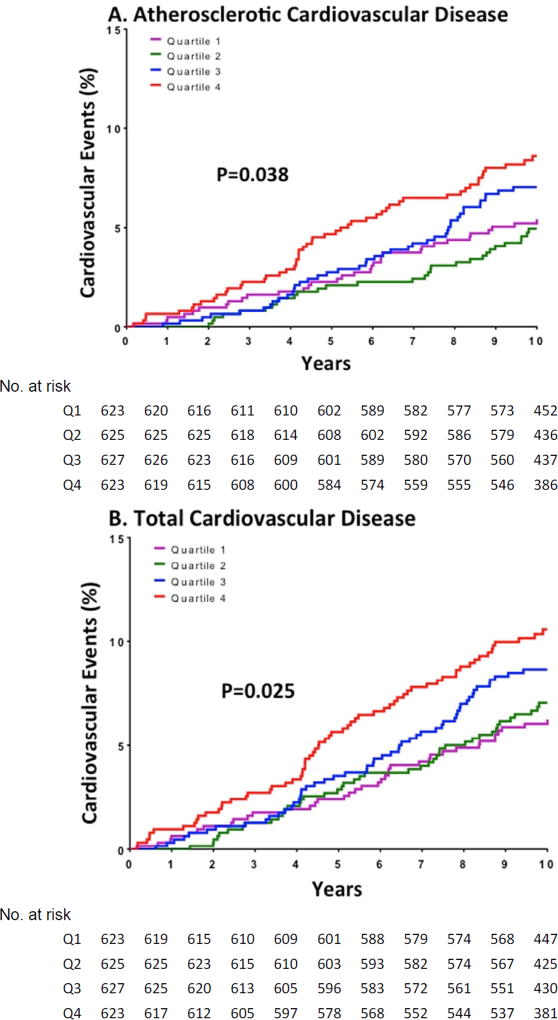

In contrast, increasing quartile of MPO/HDLp monotonically associated with the unadjusted ASCVD event rate (5.1% in Q1, 5% in Q2, 7.4% in Q3, and 8.8% in Q4, log rank p=0.038, Fig. 1). The fourth versus first quartile of MPO/HDLp was also associated with an increased risk for ASCVD (HR 1.63, 95% CI 1.06–2.50, Fig. 1 and Table 5). Adjusting for the traditional risk factors did not attenuate this association (adjusted HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.12–2.70, Fig. 1 and Table 5). Similarly, there was a significant direct association between quartiles of MPO/HDLp and total CVD (Fig. 1 and Table 6). In adjusted analyses, the fourth versus first quartile of MPO/HDLp was associated with increased total CVD (adjusted HR 1.91, 95% CI 1.27–2.85, Fig. 1 and Table 6). Sensitivity analyses revealed similar significant associations in subgroups restricted to HDL-C less than median or to HDLp less than median (data not shown). There were no interactions between MPO/HDLp and sex, race, or diabetes for the associations with incident ASCVD or total CVD (data not shown). Serial adjustments for PON1 arylesterase activity, BMI, HDL-C, HOMA-IR, hs-CRP, and IL-18 did not attenuate the findings.

Figure 1. Cumulative risk of cardiovascular events by quartile of the MPO/HDLp ratio.

Cumulative event curves are shown for quartiles (Q1 through Q4) of the MPO/HDLp ratio, with the use of quartile 1 (lowest ratio) as the reference, derived from Cox proportional-hazards models. (A) A total of 164 participants had a primary end-point event of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, (B) and 205 had a secondary end-point event of total cardiovascular disease. The primary end point was a composite atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease outcome, defined as a first non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke, coronary revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary-artery bypass grafting) or death from cardiovascular causes. A secondary end point, total cardiovascular disease, was defined as all the events included in the primary end point plus peripheral revascularization and hospitalization for heart failure or atrial fibrillation. Models are adjusted for traditional risk factors: age, sex, race, hypertension, smoking, total cholesterol, and statin use.

Discussion

This is the first report of a circulating measure of lipid peroxidation (MPO) indexed to HDL particle concentration and incident events. We found that the ratio of MPO/HDLp was directly associated with cardiovascular risk in a population-based cohort free from cardiovascular disease at baseline. This association persisted after multivariable adjustment, suggesting that the link between increased lipid peroxidation per HDL particle and cardiovascular risks is independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

In states of increased inflammation, lipid peroxidation via MPO is increased but lipid levels are also altered, especially the cholesterol content of HDL (HDL-C). Indexing MPO to HDLp may better reflect the oxidation status per HDL particle. In our study, inflammation status was assessed by several validated markers, including hs-CRP, and IL-18, each of which has been associated with CV risk.35,36 Indeed, higher MPO/HDLp was associated with increased baseline inflammation among those free of CVD, confirming that oxidative status per particle is related to a pro-inflammatory state.

Another advantage of ascertaining lipid peroxidation status per HDL particle is the potential to reflect the functionality of HDL particles. It has become increasingly clear that the cholesterol content of HDL alone (HDL-C) is not an adequate surrogate for HDL function and that the functions of HDL are diverse and may not be captured by a single metric.37–39 We ascertained two measures of HDL function: 1) anti-oxidative status via PON1 (as measured by arylesterase activity); and 2) cholesterol efflux capacity. Both PON1 and cholesterol efflux capacity are key anti-atherosclerotic functions of HDL and have been correlated with CV risk.15,16,27 In our study, MPO/HDLp trended with both worsening PON1 activity and decreased cholesterol efflux, although not statistically significantly. When adjusted for race and sex, MPO/HDLp correlated with worsening PON1 activity but not with cholesterol efflux, suggesting possible role of race and sex in modulating efflux.

PON1 is an HDL-associated protein that exerts an anti-oxidative effect, and PON1 activity correlates with HDL particle concentration and large HDL particles.40,41 Cholesterol efflux also correlates with HDL particle concentration but not with large particles.27 Lower serum PON1 activity and cholesterol efflux are both associated with increased cardiovascular risks in several cohorts.15,16,27 MPO and PON1 have been assessed together in studies of patients with acute coronary syndrome and established coronary disease.23,42 Our study extends these findings by assessing oxidative status per HDL particle and CVD risk. We found that increasing MPO/HDLp was associated with worsening PON1 activity across a large, multi-ethnic cohort free of CVD when adjusted for race and sex. In contrast, MPO/HDLp was not associated with cholesterol efflux in our cohort, a consistent observation from prior studies assessing both HDL’s oxidative function and efflux,43,44 and supportive of the diverse, non-overlapping anti-inflammatory functions of HDL. Interestingly, despite correlation between MPO/HDLp and PON1, PON1 activity does not explain the associations between MPO/HDLp and cardiovascular events in our study.

Several prior studies have shown associations between MPO levels and CHD among high-risk patients. MPO levels are higher in those with CHD and also are associated with increasing severity of coronary atherosclerosis.12,21 In one study of patients with ACS, those with increased MPO levels were at increased risk of adverse events, reinfarction, or death,13 confirmed in another study assessing mortality after acute MI.14 In contrast, the associations between MPO and ASCVD in those without ACS have been inconsistent. While several case-control studies linked higher MPO levels to presence of CAD or increased risk of incident CAD,11,20 one cohort study found that plasma MPO did not predict mortality independent of other cardiovascular risk factors in patients with stable CAD.22 Similarly, in a cross-sectional study of patients undergoing elective coronary angiography, there were no significant differences in MPO concentrations for those with proven stable CAD compared to those without.19

In contrast to these prior studies in patients with stable CAD or high risk ACS, our study assessed MPO in a large longitudinal cohort free from cardiovascular disease at baseline. In this study population, MPO was previously reported to be associated with subclinical atherosclerosis in a race-specific manner.31 The current investigation extends these findings by indexing MPO levels to HDL particle concentration and reporting association with incident cardiovascular events without effect modification by race/ethnicity.

A limitation of our study includes the relatively small number of events and cohort size, which may affect the reliability of our observed effects. Another limitation is that the younger age of our study population may provide different magnitudes of associations with events than other studies that assessed the CV biomarkers in older populations.

In conclusion, MPO indexed to HDL particle concentration (MPO/HDLp) at baseline was directly associated with the risk of incident CVD events in a population initially free of CVD, reflecting increased inflammation. These findings suggest that compositional assessment of dysfunctional HDL may have clinical relevance and support future studies on biomarkers of HDL metabolism and cardiovascular risk.

Highlights.

Increased serum levels of MPO indexed to HDL particle concentration (MPO/HDLp ratio) reflect increased state of inflammation.

The MPO/HDLp ratio is directly associated with CVD risk in people who are free of CVD at baseline.

Compositional assessment of dysfunctional HDL may be necessary to understand the role of HDL in atheroprotection.

Acknowledgments

MPO measurements were provided by Biosite, Inc. (now Alere, Inc., Waltham, MA), and NMR measurements were provided by LipoScience (now LabCorp, Burlington, NC).

Financial support

The Dallas Heart Study is supported by grants from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH (UL1TR001105). Anand Rohatgi is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH under Award Number K08HL118131 and by the American Heart Association under Award Number 15CVGPSD27030013.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

Anand Rohatgi is on Scientific Advisory Board for Cleveland HeartLab and HDL Diagnostics, Inc. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Author contributions

Study conception and design: Khine, Rohatgi. Acquisition of data: Khine, Ayers, Rohatgi. Analysis and interpretation of data: Khine, Ayers, Rohatgi. Drafting of manuscript: Khine, Rohatgi. Critical revision: Khine, Teiber, Haley, Khera, Ayers, Rohatgi.

References

- 1.Daugherty A, Dunn JL, Rateri DL, Heinecke JW. Myeloperoxidase, a catalyst for lipoprotein oxidation, is expressed in human atherosclerotic lesions. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1994 Jul;94(1):437–444. doi: 10.1172/JCI117342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang R, Brennan ML, Shen Z, et al. Myeloperoxidase functions as a major enzymatic catalyst for initiation of lipid peroxidation at sites of inflammation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002 Nov 29;277(48):46116–46122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Podrez EA, Schmitt D, Hoff HF, Hazen SL. Myeloperoxidase-generated reactive nitrogen species convert LDL into an atherogenic form in vitro. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1999 Jun;103(11):1547–1560. doi: 10.1172/JCI5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicholls SJ, Zheng L, Hazen SL. Formation of dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein by myeloperoxidase. Trends in cardiovascular medicine. 2005;15(6):212–219. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.06.004. Accessed Aug. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao B, Oda MN, Oram JF, Heinecke JW. Myeloperoxidase: an inflammatory enzyme for generating dysfunctional high density lipoprotein. Current opinion in cardiology. 2006 Jul;21(4):322–328. doi: 10.1097/01.hco.0000231402.87232.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsche G, Furtmuller PG, Obinger C, Sattler W, Malle E. Hypochlorite-modified high-density lipoprotein acts as a sink for myeloperoxidase in vitro. Cardiovascular research. 2008 Jul 1;79(1):187–194. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aviram M, Billecke S, Sorenson R, et al. Paraoxonase active site required for protection against LDL oxidation involves its free sulfhydryl group and is different from that required for its arylesterase/paraoxonase activities: selective action of human paraoxonase allozymes Q and R. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 1998 Oct;18(10):1617–1624. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.10.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenblat M, Karry R, Aviram M. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) is a more potent antioxidant and stimulant of macrophage cholesterol efflux, when present in HDL than in lipoprotein-deficient serum: relevance to diabetes. Atherosclerosis. 2006 Jul;187(1):74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenblat M, Vaya J, Shih D, Aviram M. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) enhances HDL-mediated macrophage cholesterol efflux via the ABCA1 transporter in association with increased HDL binding to the cells: a possible role for lysophosphatidylcholine. Atherosclerosis. 2005 Mar;179(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Y, Wu Z, Riwanto M, et al. Myeloperoxidase, paraoxonase-1, and HDL form a functional ternary complex. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013 Sep;123(9):3815–3828. doi: 10.1172/JCI67478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang R, Brennan ML, Fu X, et al. Association between myeloperoxidase levels and risk of coronary artery disease. Jama. 2001 Nov 7;286(17):2136–2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.17.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duzguncinar O, Yavuz B, Hazirolan T, et al. Plasma myeloperoxidase is related to the severity of coronary artery disease. Acta cardiologica. 2008 Apr;63(2):147–152. doi: 10.2143/AC.63.2.2029520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baldus S, Heeschen C, Meinertz T, et al. Myeloperoxidase serum levels predict risk in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2003 Sep 23;108(12):1440–1445. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000090690.67322.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mocatta TJ, Pilbrow AP, Cameron VA, et al. Plasma concentrations of myeloperoxidase predict mortality after myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007 May 22;49(20):1993–2000. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharyya T, Nicholls SJ, Topol EJ, et al. Relationship of paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene polymorphisms and functional activity with systemic oxidative stress and cardiovascular risk. Jama. 2008 Mar 19;299(11):1265–1276. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang WH, Hartiala J, Fan Y, et al. Clinical and genetic association of serum paraoxonase and arylesterase activities with cardiovascular risk. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2012 Nov;32(11):2803–2812. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.253930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy DJ, Tang WH, Fan Y, et al. Diminished antioxidant activity of high-density lipoprotein-associated proteins in chronic kidney disease. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2013 Apr;2(2):e000104. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunutsor SK, Bakker SJ, James RW, Dullaart RP. Serum paraoxonase-1 activity and risk of incident cardiovascular disease: The PREVEND study and meta-analysis of prospective population studies. Atherosclerosis. 2016 Feb;245:143–154. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kubala L, Lu G, Baldus S, Berglund L, Eiserich JP. Plasma levels of myeloperoxidase are not elevated in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2008 Aug;394(1–2):59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meuwese MC, Stroes ES, Hazen SL, et al. Serum myeloperoxidase levels are associated with the future risk of coronary artery disease in apparently healthy individuals: the EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007 Jul 10;50(2):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ndrepepa G, Braun S, Mehilli J, von Beckerath N, Schomig A, Kastrati A. Myeloperoxidase level in patients with stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes. European journal of clinical investigation. 2008 Feb;38(2):90–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stefanescu A, Braun S, Ndrepepa G, et al. Prognostic value of plasma myeloperoxidase concentration in patients with stable coronary artery disease. American heart journal. 2008 Feb;155(2):356–360. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haraguchi Y, Toh R, Hasokawa M, et al. Serum myeloperoxidase/paraoxonase 1 ratio as potential indicator of dysfunctional high-density lipoprotein and risk stratification in coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2014 Jun;234(2):288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Victor RG, Haley RW, Willett DL, et al. The Dallas Heart Study: a population-based probability sample for the multidisciplinary study of ethnic differences in cardiovascular health. The American journal of cardiology. 2004 Jun 15;93(12):1473–1480. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teiber JF, Kramer GL, de Lemos JA, Drazner MH, Haley RW. Abstract 17217: Serum Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) Activity is Associated With Indices of Hypertensive Heart Disease and Cardiac Remodeling in the Dallas Heart Study Population. Circulation. 2015 Nov 10;132(Suppl 3):A17217. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teiber JF, Kramer GL, Haley RW. Methods for measuring serum activity levels of the 192 Q and R isoenzymes of paraoxonase 1 in QR heterozygous individuals. Clinical chemistry. 2013 Aug;59(8):1251–1259. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.199331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rohatgi A, Khera A, Berry JD, et al. HDL cholesterol efflux capacity and incident cardiovascular events. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Dec 18;371(25):2383–2393. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zirlik A, Abdullah SM, Gerdes N, et al. Interleukin-18, the metabolic syndrome, and subclinical atherosclerosis: results from the Dallas Heart Study. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2007 Sep;27(9):2043–2049. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khera A, Vega GL, Das SR, et al. Sex differences in the relationship between C-reactive protein and body fat. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2009 Sep;94(9):3251–3258. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gore MO, Luneburg N, Schwedhelm E, et al. Symmetrical dimethylarginine predicts mortality in the general population: observations from the Dallas heart study. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013 Nov;33(11):2682–2688. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen LQ, Rohatgi A, Ayers CR, et al. Race-specific associations of myeloperoxidase with atherosclerosis in a population-based sample: the Dallas Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011 Dec;219(2):833–838. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeyarajah EJ, Cromwell WC, Otvos JD. Lipoprotein particle analysis by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clinics in laboratory medicine. 2006 Dec;26(4):847–870. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maroules CD, Rosero E, Ayers C, Peshock RM, Khera A. Abdominal aortic atherosclerosis at MR imaging is associated with cardiovascular events: the Dallas heart study. Radiology. 2013 Oct;269(1):84–91. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13122707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jonckheere AR. A DISTRIBUTION-FREE k-SAMPLE TEST AGAINST ORDERED ALTERNATIVES. Biometrika. 1954;41(1–2):133–145. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koenig W, Sund M, Frohlich M, et al. C-Reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men: results from the MONICA (Monitoring Trends and Determinants in Cardiovascular Disease) Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation. 1999 Jan 19;99(2):237–242. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jefferis BJ, Papacosta O, Owen CG, et al. Interleukin 18 and coronary heart disease: prospective study and systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2011 Jul;217(1):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackey RH, Greenland P, Goff DC, Jr, Lloyd-Jones D, Sibley CT, Mora S. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol and particle concentrations, carotid atherosclerosis, and coronary events: MESA (multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis) Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012 Aug 7;60(6):508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.deGoma EM, deGoma RL, Rader DJ. Beyond high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels evaluating high-density lipoprotein function as influenced by novel therapeutic approaches. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008 Jun 10;51(23):2199–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Steeg WA, Holme I, Boekholdt SM, et al. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein particle size, and apolipoprotein A-I: significance for cardiovascular risk: the IDEAL and EPIC-Norfolk studies. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008 Feb 12;51(6):634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dullaart RP, Otvos JD, James RW. Serum paraoxonase-1 activity is more closely related to HDL particle concentration and large HDL particles than to HDL cholesterol in Type 2 diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Clinical biochemistry. 2014 Aug;47(12):1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dullaart RP, Gruppen EG, Dallinga-Thie GM. Paraoxonase-1 activity is positively related to phospholipid transfer protein activity in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Role of large HDL particles. Clinical biochemistry. 2015 Dec 2; doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emami Razavi A, Basati G, Varshosaz J, Abdi S. Association between HDL particles size and myeloperoxidase/ paraoxonase-1 (MPO/PON1) ratio in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Acta medica Iranica. 2013;51(6):365–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de la Llera-Moya M, Drazul-Schrader D, Asztalos BF, Cuchel M, Rader DJ, Rothblat GH. The ability to promote efflux via ABCA1 determines the capacity of serum specimens with similar high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to remove cholesterol from macrophages. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2010 Apr;30(4):796–801. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.199158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Llera-Moya M, et al. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2011 Jan 13;364(2):127–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]