Abstract

Manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD), localized at the mitochondrial matrix, has the ability to protect cells against oxidative damage. It has been reported that low levels of Mn-SOD gene expression cause the development of certain kind of tumors. On the other hand, overexpression of Mn-SOD gene may play an important role in the development of cancer. In our study, we find that Mn-SOD activity was higher in nonaggressive (MCF-7) and aggressive (BT-549 and 11-9-14) breast cancer cell lines compared to that of nontumorigenic (MCF-12A and MCF-12F) mammary epithelial cell lines. We also observed an increased expression of Mn-SOD gene in cancerous cell lines. The elevated level of SOD activity in nonaggressive and aggressive breast epithelial cell lines was associated with some changes in nucleotide sequence.

INTRODUCTION

Carcinoma of the breast, the third most common cancer worldwide, accounts for the highest morbidity and mortality [1]. It is also the second leading cause of cancer death in women, after lung cancer [2]. The etiology of breast cancer is multifactorial. Hormonal, genetic, and environmental factors are implicated in the pathogenesis of breast cancer [3]. Furthermore, reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide anions and hydrogen peroxide-induced lipid peroxidation, play a major role in malignant transformation [4] and tumor cell proliferation and invasion [5, 6, 7]. It has been hypothesized that the production of ROS in combination with a decrease in the activity of antioxidant enzymes may be characteristic of tumor cells [8, 9].

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is a family of ubiquitous antioxidant metalloproteinases that catalyze the conversion of superoxide anion radicals to hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen [10]. Three different isoforms of SOD (cytosolic Cu/Zn SOD or SOD1, mitochondrial Mn-SOD or SOD2, and extracellular SOD or SOD3) exist within this family. Among these three, manganese superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) which is localized at the mitochondrial matrix [11, 12, 13] has shown the ability to reverse malignant phenotype in a variety of human tumor cells that are low or absent in Mn-SOD expression. It has been hypothesized that the Mn-SOD gene is a tumor suppressor [14, 15]. Mn-SOD activity has been reported to be decreased in many transformed cell lines suggesting that an altered Mn-SOD gene may play an important role in the development of cancer [16, 17, 18, 19]. The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether a differential expression of Mn-SOD exists between nontumorigenic human mammary epithelial cell lines (MCF-12A and MCF-12F), nonaggressive human breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7) and aggressive cancerous human mammary epithelial cell lines (BT-549 and 11-9-14).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Maintenance of human mammary epithelial cell lines

Five cell lines representing nontumorigenic (MCF-12A and MCF-12F), nonaggressive cancerous (MCF-7), and aggressive cancerous (11-9-14 and BT-549) human mammary epithelial cells were used in this study. All cell lines except 11-9-14 were obtained from ATCC, Va. 11-9-14 cell line was obtained from the Tissue Procurement Facility, Meharry Medical College, Nashville, Tenn. It was originated from the human breast epithelial cell line BT-549 at ATCC and transfected with galectin-3, a β-galactoside binding protein (a cell adhesion molecule). The cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12, supplemented with 100 μg/mL penicillin-streptomycin, 2.5 μg/mL fungizone, 20 ng/mL epidermal growth factor, 98 ng/mL cholera toxin, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, and nonessential amino acids. The cultures were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. All cell culture supplies were purchased from Sigma, Mo.

Assay of SOD activity

SOD activity was measured using alkaline dimethyl sulfoxide as superoxide anion generating system as follows. Samples to be assayed (200 μL) were added to 1 mL of 0.20 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.6) containing 10−4 M EDTA and 2 × 10−5 M cytochrome C. Tubes were kept in an ice bath for 20 minutes. Then, 0.5 mL alkaline DMSO (DMSO containing 1% water and 5 mM NaOH) was added with stirring. After the addition of alkaline DMSO, the final pH of the solution was usually between 9.5 and 9.6. Absorbance of reduced cytochrome C was determined at 550 nm against samples prepared under similar conditions except that DMSO did not contain NaOH. Mn-SOD activity was determined after incubating the cell lysates with 50 mM NaCN because NaCN inhibits the activity of cytosolic Cu-Zn SOD. The final concentration of NaCN in the assay mixture was 5 mM. A unit of enzymatic activity is the amount of enzyme, which causes 50% inhibition of alkaline DMSO-mediated cytochrome c reduction [20].

Isolation of RNA

RNA was isolated from 106 cells using Trizol (Invitrogen, Md). Cells were first washed with sterile PBS three times and resuspended in 1 mL Trizol and sonicated in a Branson sonifier cell disrupter. The mixture was kept in room temperature for 5 minutes. Then 200 μL chloroform was added and the mixture was vigorously shaken. The phases were separated by centrifuging at 12 000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. The RNA was then precipitated from the aqueous phase with isopropanol (25°C). The pellet was washed with ample amounts of sterile, 70% ethanol (25°C). The concentration and the purity of the RNA were analyzed in a UV spectrophotometer.

Slot blot hybridization

Slot blot hybridization was performed using increasing amounts of RNA from all samples. The reverse primer, 5′GTATCTTTCAGTTACATTCTCCCA-3′, for SOD and forward primer, 5′GTGGAGTCTACTGGCGTCTTC-3′, for GAPDH were digoxigenin-labeled for slot blot hybridization using the Terminal DIG labeling kit (Roche Biochemicals, Ind). Different amounts of RNA (0, 1, 2, and 4 μg) from all cells were loaded onto a positively charged nylon membrane (MSI, Ga) using a Turboblotter (BioRad, Calif). The samples were then linked to the membrane using a UV crosslinker (Stratagene, Calif). A nonradioactive detection method using digoxigenin (Roche Biochemicals, Ind) was used to detect any hybridization. The membranes were washed under high-stringent conditions with 0.1 × SSC and 0.1% SDS at 600°C for 1 hour before being exposed to the film. The labeled reverse primer was used as the probe and the hybridization was performed following manufacturer's instructions. The band intensities (IDV values) were quantitated using the alpha imager (Alpha Innotech, Calif).

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

RT-PCR of both SOD and GAPDH was performed using 5 μg RNA from each sample, using the One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen, Md). The primers were synthesized to amplify approximately 200 amino acids in the carboxyl end of the protein and based on the sequences from the GenBank Accession No. M36693. The primer sequences were 5′-TTGAGCCGGGCAGTGTGCGGCACC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTATCTTTCAGTTACATTCTCCCA-3′ (reverse) for SOD, and 5′GTGGAGTCTACTGGCGTCTTC-3′ (forward) and 5′ CATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTT-3′ (reverse) for GAPDH. RT-PCR was performed in a thermal cycler (Biometra, Tgradient) as follows: 1 cycle for 30 minutes at 45°C, 1 cycle for 2 minutes at 94°C, 39 cycles for 1 minute at 94°C, 1 minute at 50°C, 2 minutes at 72°C and 1 cycle for 10 minutes at 72°C. The RT-PCR products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, purified using QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Calif), and sequenced using BigDye terminators kit (Applied Biosystems, Calif). The sequences were analyzed using Applied Biosystems automated sequencer (ABI 3700 model).

Statistical analysis

Differences between tumorigenic and nontumorigenic cells were assessed by using ANOVA, and the significance level was set at .

RESULTS

Activity of SOD

Total as well as Mn-SOD activity was varied between cell lines (Table 1). The order of activity was MCF-7 (nonaggressive) > BT-549 and 11-9-14 (aggressive) > MCF-12A and MCF-12F (nontumorigenic).

Table 1.

Activity of SOD in different cell lines (values are mean ± SEM, ). *Values in cancer cell lines (MCF-7, BT-549, 11-9-14) are significantly different from those in normal cell lines (MCF-12A and MCF-12F), .

| Cell line | Total SOD activity (unit/mg protein) | Mn-SOD activity (unit/mg protein) |

|---|---|---|

| MCF-12A | 17.77 ± 1.563 | 3.04 ± 0.35 |

| MCF-12F | 21.72 ± 1.508 | 2.42 ± 0.12 |

| MCF-7 | 42.76 ± 5.717* | 16.38 ± 1.13* |

| BT-549 | 28.47 ± 1.215* | 7.83 ± 0.47* |

| 11-9-14 | 29.49 ± 0.858* | 10.69 ± 0.29* |

Expression of Mn-SOD gene

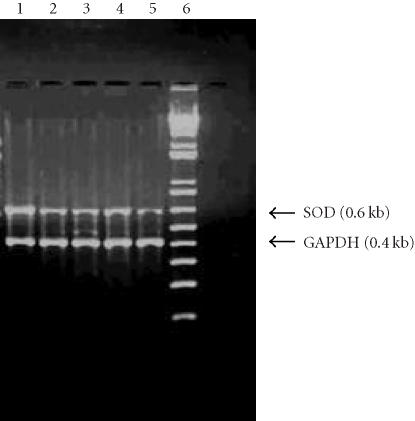

An RT-PCR yielded products of approximately 0.6 kb for SOD and 0.4 kb for GAPDH in all cell lines. The results showed the differential expression of Mn-SOD gene between nontumorigenic, nonaggressive, and aggressive breast cancer cell lines (BT-549 and 11-9-14) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. The gel picture showing differential RT-PCR product. Lane 1 : 5 μg RNA from MCF-12A in RT-PCR; lane 2 : 5 μg RNA from MCF-12F in RT-PCR; lane 3 : 5 μg RNA from MCF-7 in RT-PCR; lane 4 : 5 μg RNA from BT-549 in RT-PCR; lane 5 : 5 μg RNA from 11-9-14 in RT-PCR; lane 6 : 1 kb plus marker.

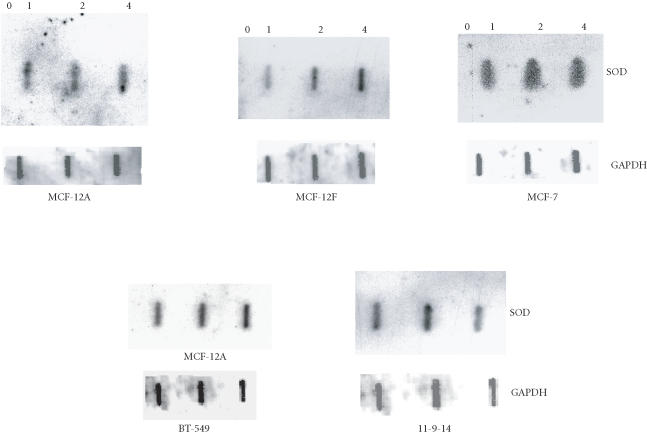

A slot blot hybridization (Figure 2) was done with increasing amounts of RNA from nontumorigenic (MCF-12A and MCF-12F), nonaggressive cancerous (MCF-7), and aggressive cancerous (BT-549 and 11-9-14) cell lines to confirm their differential expression of Mn-SOD RNA. The housekeeping gene, GAPDH, was used as a positive control. No change in the expression of GAPDH was observed with increasing concentration of RNA. The quantitative analysis of the RNA levels shown in Figure 2 has been normalized with the RNA level of GAPDH gene (Table 2) which indicates that the band intensities are different between these cell lines. Highest expression was observed in MCF-7 in comparison with others. Expression was lowest in MCF-12A.

Figure 2.

Slot blot hybridization. Increasing amounts of RNA (0, 1, 2, and 4 μg) were taken from MCF-12A, MCF-12F, MCF-7, BT-549, and 11-9-14 breast epithelial cells and hybridized with probe.

Table 2.

Band intensities (IDV values) of slot blot for normal and cancer cell lines at different RNA concentrations. (Values are mean ± SEM, ). Values in cancer cell lines (MCF-7, BT-549, and 11-9-14) are significantly different from those in normal cell lines (MCF-12A and MCF-12F), .

| RNA conc. (μg) | IDV values | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-12A | MCF-12F | MCF-7 | BT-549 | 11-9-14 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0.95 ± 0.003 | 1.53 ± 0.03 | 4.49 ± 0.002 | 1.97 ± 0.002 | 1.91 ± 0.001 |

| 2 | 1.37 ± 0.05 | 2.11 ± 0.04 | 4.71 ± 0.1 | 2.84 ± 0.06 | 3.25 ± 0.04 |

| 4 | 1.76 ± 0.08 | 2.44 ± 0.14 | 5.37 ± 0.49 | 3.24 ± 0.11 | 3.04 ± 0.61 |

Sequencing of RT-PCR products of Mn-SOD gene

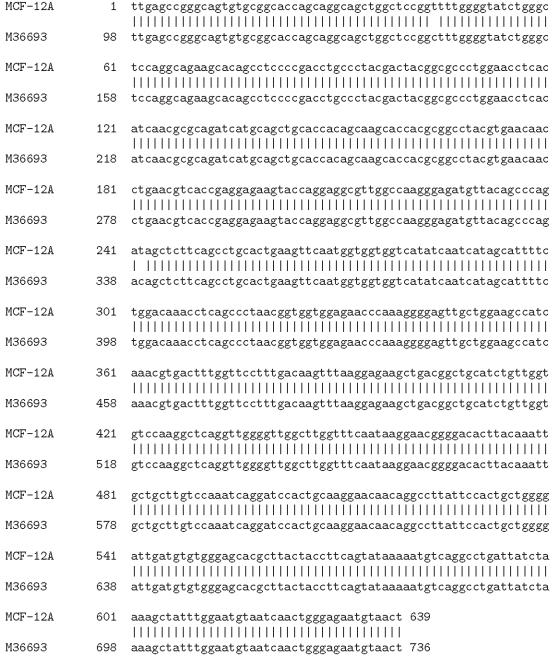

The RT-PCR products from MCF-12A, MCF-12F, MCF-7, BT-549, and 11-9-14 were sequenced and each nucleotide sequence was compared with that of the human Mn-SOD gene as reported in NCBI data base (M36693). We have shown here the alignment of the nucleotide sequence of one representative human breast cell line (MCF-12A) with that of the human Mn-SOD from GenBank (Accession No. M36693) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Alignment of nucleotide sequence of MCF-12A Mn-SOD gene with that of human GenBank (M36693) sequence.

With our primers, we could sequence 627 to 652 nucleotides depending on the cell lines (Table 3). This sequence exactly aligns to a segment (98–746) of the human Mn-SOD cDNA (976 bp, GenBank Accession No. M36693). In MCF-12A and MCF-12F, we found three base changes in the nucleotide level (Table 4). One of these was common in both (c339t). The two other changes were different between MCF-12A (g130c and c139t) and MCF-12F (c141t and t625c). When the sequences of MCF-7, BT-549, and 11-9-14 were compared with that of M36693, we found only one substitution in each of these cell lines (Table 3). In both MCF-7 and 11-9-14 cell lines, this change was from c to t (c339t) as observed in both MCF-12A and MCF-12F. However, in BT-549, it was from c to t at 141 (c141t).

Table 3.

Comparison of nucleotide sequence of RT-PCR products of Mn-SOD gene between different human breast cell lines.

Table 4.

Comparison of amino acid (AA) sequence of Mn-SOD gene between different human breast cell lines.

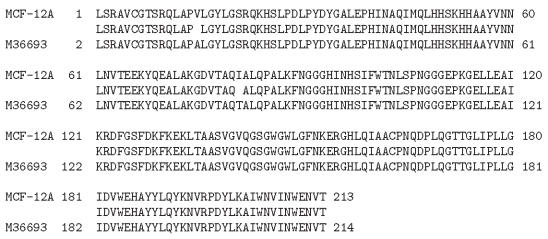

The nucleotide sequence was translated using human codon usage to give a peptide sequence of 209–217 amino acids (Table 4). This sequence exactly corresponds to a segment (2–217) of the Mn-SOD peptide sequence of M36693 (GenBank). For MCF-12A, three amino acid changes were found (Q12H, A16V, T82I). Two changes were observed for MCF-12F cell line (A16V, T82I). But in other cell lines, only one amino acid substitution (T82I in MCF-7 and 11-9-14, and A16V in BT-549) was found. The alignment of the peptide sequence of one representative human breast cell line (MCF-12A) with that of the human Mn-SOD from the GenBank (M36693) is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Alignment of peptide sequence of MCF-12A Mn-SOD gene with that of human GenBank (M36693) sequence.

DISCUSSION

Mn-SOD plays a key role in protecting cells against oxidative damage and regulating cellular concentration of , which is a highly reactive oxidant and an unwanted product of cellular metabolism [21]. Many different types of tumors have been demonstrated to have low Mn-SOD activity [22]. Overexpression of Mn-SOD suppresses the tumorigenicity of human melanoma cells, breast cancer cells, and glioma cells, suggesting that Mn-SOD is a tumor suppressor gene in a wide variety of cancers [15, 23, 24].

Several reports have however shown that despite generally low levels of Mn-SOD in the center of solid tumor nests, there appeared to be very intense Mn-SOD staining in a few tumor cells located at the leading edge or outside layers of tumors adjacent to benign epithelium in breast and prostate tumors [25, 26]. In addition, Mn-SOD expression is increased in metastatic gastric cancer [27]. Lam et al [28] demonstrated that overexpression of Mn-SOD by adenovirus gene transfer in hamster squamous carcinoma cells stimulated tumor cell invasive capacity and this elevation was abolished by adenovirus catalase suggesting the involvement of ROS and particularly by hydrogen peroxide in the process of tumor invasion. Reconstitution of Mn-SOD in tumor cells induces cell resistance to the cytotoxic effects of TNF-α, ionizing, and hyperthermia [29, 30, 31], suggesting that Mn-SOD functions not only as a tumor suppressor but also as a mediator in signaling cell resistance to ROS-induced cytotoxicity [32].

In our study, we find high activity of Mn-SOD in certain breast cancer cell lines especially in MCF-7 cell line (Table 1). We speculate that this elevation of Mn-SOD in cancerous breast tissues without a corresponding increase in the activity of catalase and/or glutathione peroxidase would lead to the accumulation of peroxides and oxidative stress and will enhance the progression of cancer. Siemankowski et al [31] also showed a similar kind of activity (∼ 40 U SOD/mg protein) in MCF-7 cell line. Mn-SOD may play a dual role in relation to exposure to ROS. Human cancer has frequently decreased Mn-SOD levels. However, although it is clearly an important scavenger of ROS, the production of H2O2 by Mn-SOD in specific circumstances may lead to potentially carcinogenic effects, especially if some individuals have a decreased capacity to remove H2O2 by glutathione peroxidase or catalase. Alternatively, better scavenging capacity may decrease the ability to undergo normal cellular protective mechanisms such as apoptosis; therefore, oxidative stresses would have a greater likelihood of nuclear DNA mutation [33, 34]. According to our results (Tables 3 and 4), a G- to C- substitution in 130 positions in MCF-12A (nontumorigenic) was found that changes the amino acid codon at 12 positions in the peptide from Q to H. But this change was not observed in MCF-7, BT-549, and 11-9-14 cell lines. Rosenblum et al [35] suggest that the alteration may affect the cellular allocation of the enzyme and transport of Mn-SOD into the mitochondrion where it would be biologically available. They further suggest that inefficient targeting of Mn-SOD could leave mitochondria without their full defense against superoxide radicals, which could lead to protein oxidation as well as mitochondrial DNA mutations. Overexpression of Mn-SOD perhaps causes (a) a decrease in the malignant phenotypes of various types of cancer including breast cancer [15, 23], (b) an increase in the resistance for cytotoxicity from tumor necrosis factor α in breast cancer [30, 36], (c) an increase in apoptosis [37], and (d) an improvement in apoptosis after hydrogen peroxide challenge [37]. It is also possible that mitochondrial Mn-SOD could impact on oxidative damage in nuclear DNA, which would be one plausible mechanism for increased risk from a genetic polymorphism in Mn-SOD, although the effects on the mitochondrion alone could be sufficient for its impact on carcinogenesis. Thus, there are a number of ways that changes in the cellular distribution of Mn-SOD might affect breast cancer risk. It should further be noted that this is the first study on the nucleotide and amino acid sequence of Mn-SOD gene in breast epithelial cell lines. This information will be useful in future design of experiments involving Mn-SOD gene in breast epithelial cell lines. Now in our laboratory, we are trying to sequence the whole Mn-SOD cDNA as well as the expression of Mn-SOD mRNA by northern blot analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Defense to S. K. Das (Grant DAMD17-03-1-0352 and Grant DAMD17-03-2-0054) and the National Institutes of Health to S. K. Das and S. Mukherjee (Grant 2S06GM-08037).

References

- 1.Parkin D.M, Pisani P, Ferlay J. Estimates of the worldwide incidence of 25 major cancers in 1990. Int J Cancer. 1990;80(6):827–841. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990315)80:6<827::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO World Health Report 1997 Executive Summary. The World Health Report Archives. 1997:1–16.

- 3.Russo J, Hu Y.F, Yang X, Russo I.H. Developmental, cellular, and molecular basis of human breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2000;(27):17–37. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez R.A. Free radicals, oxidative stress, and DNA metabolism in human cancer. Cancer Invest. 1999;17:376–377. doi: 10.3109/07357909909032882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bize I.B, Oberley L.W, Morris H.P. Superoxide dismutase and superoxide radical in Morris hepatomas. Cancer Res. 1980;40(10):3686–3693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaughnessy S.G, Buchanan M.R, Turple S, Richardson M, Orr F.W. Walker carcinosarcoma cells damage endothelial cells by the generation of reactive oxygen species. Am J Pathol. 1989;134(4):787–796. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szatrowski T.P, Nathan C.F. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51(3):794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toyokuni S, Okamoto K, Yodoi J, Hiai H. Persistent oxidative stress in cancer. FEBS Lett. 1995;358(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01368-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oberley L.W, Oberley T.D. Role of antioxidant enzymes in the cancer phenotype. In: Clerch L.B, Massaro D.J, editors. Oxygen, Gene Expression and Cellular Function (Lung Biology in Health and Disease) New York, NY: Marcel Dekker; 1997. pp. 279–307. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varachaud A, Berthier-Vergnes O, Rigaud M, Schmitt D, Bernard P. Variable expression of Mn SOD in three different human melanoma cell lines. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8(2):90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisiger R.A, Fridovich I. Superoxide dismutase. Organelle specificity. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(10):3582–3592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisiger R.A, Fridovich I. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Site of synthesis and intramitochondrial localization. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(13):4793–4796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oberley T.D, Oberley L.W, Slattery A.F, Lauchner L.J, Elwell J.H. Immunohistochemical localization of antioxidant enzymes in adult Syrian hamster tissues and during kidney development. Am J Pathol. 1990;137(1):199–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bravard A, Sabatier L, Hoffschir F, Ricoul M, Luccioni C, Dutrillaux B. SOD2: a new type of tumor-suppressor gene? Int J Cancer. 1992;51(3):476–480. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910510323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J.J, Oberley L.W, St Clair D.K, Ridnour L.A, Oberley T.D. Phenotypic changes induced in human breast cancer cells by overexpression of manganese-containing superoxide dismutase. Oncogene. 1995;10(10):1989–2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oberley L.W, Buettner G.R. Role of superoxide dismutase in cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1979;39(4):1141–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westman N.G, Marklund S.L. Copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase and manganese-containing superoxide dismutase in human tissues and human malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 1981;41(7):2962–2966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marklund S.L, Westman N.G, Lundgren E, Roos S.G. Copper- and zinc-containing superoxide dismutase, manganese-containing superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase in normal and neoplastic human cell lines and normal human tissues. Cancer Res. 1982;42(5):1955–1961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guner G, Islekel H, Oto O, Hazan E, Acikel U. Evaluation of some antioxidant enzymes in lung carcinoma tissue. Cancer Lett. 1996;103(2):233–239. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(96)04226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyland K, Voisin E, Banoun H, Auclair C. Superoxide dismutase assay using alkaline dimethylsulfoxide as superoxide anion-generating system. Anal Biochem. 1983;135(2):280–287. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90684-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christianson D.W. Structural chemistry and biology of manganese metalloenzymes. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1997;67(2-3):217–252. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(97)88477-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oberley L.W, Buettner G.R. Role of superoxide dismutase in cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1979;39(4):1141–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Church S.L, Grant J.W, Ridnour L.A, et al. Increased manganese superoxide dismutase expression suppresses the malignant phenotype of human melanoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(7):3113–3117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.3113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong W, Oberley L.W, Oberley T.D, St Clair D.K. Suppression of the malignant phenotype of human glioma cells by overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Oncogene. 1997;14(4):481–490. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas P.A, Oykutlu D, Pou B, et al. Immunohistochemical characterization of antioxidant enzymes in human breast cancer. Pathol Oncol Res. 1997;3(4):278–286. doi: 10.1007/BF02904287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bostwick D.G, Alexander E.E, Singh R, et al. Antioxidant enzyme expression and reactive oxygen species damage in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer. Cancer. 2000;89(1):123–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malafa M, Margenthaler J, Webb B, Neitzel L, Christophersen M. MnSOD expression is increased in metastatic gastric cancer. J Surg Res. 2000;88(2):130–134. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam E.W, Zwacka R, Seftor E.A, et al. Effects of antioxidant enzyme overexpression on the invasive phenotype of hamster cheek pouch carcinoma cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27(5-6):572–579. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong G.H.W, Elwell J.H, Oberley L.W, Goeddel D.V. Manganous superoxide dismutase is essential for cellular resistance to cytotoxicity of tumor necrosis factor. Cell. 1989;58(5):923–931. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90944-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J.J, Oberley L.W. Overexpression of manganese-containing superoxide dismutase confers resistance to the cytotoxicity of tumor necrosis factor alpha and/or hyperthermia. Cancer Res. 1997;57(10):1991–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siemankowski L.M, Morreale J, Briehl M.M. Antioxidant defenses in the TNF-treated MCF-7 cells: selective increase in MnSOD. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(7-8):919–924. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z, Khaletskiy A, Wang J, Wong J.Y.C, Oberley L.W, Li J.J. Genes regulated in human breast cancer cells overexpressing manganese-containing superoxide dismutase. Free Radic Biol Med. 2001;30(3):260–267. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00468-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oberley T.D, Oberley L.W. Antioxidant enzyme levels in cancer. Histol Histopathol. 1997;12(2):525–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Briehl M.M, Baker A.F, Siemankowski L.M, Morreale J. Modulation of antioxidant defenses during apoptosis. Oncol Res. 1997;9(6-7):281–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenblum J.S, Gilula N.B, Lerner R.A. On signal sequence polymorphisms and diseases of distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(9):4471–4473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manna S.K, Zhang H.J, Yan T, Oberley L.W, Aggarwal B.B. Overexpression of manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses tumor necrosis factor-induced apoptosis and activation of nuclear transcription factor-kappaB and activated protein-1. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(21):13245–13254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kinscherf R, Claus R, Wagner M, et al. Apoptosis caused by oxidized LDL is manganese superoxide dismutase and p53 dependent. FASEB J. 1998;12(6):461–467. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.6.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]