Abstract

Immunoreceptors can transduce either inhibitory or activatory signals depending on ligand avidity and phosphorylation status, which is modulated by the protein kinases Lyn and Fyn. Here we show that Lyn and Fyn control immune receptor signaling status. SHP-1 tyrosine 536 phosphorylation by Lyn activates the phosphatase promoting inhibitory signaling through the immunoreceptor. By contrast, Fyn-dependent phosphorylation of SHP-1 serine 591 inactivates the phosphatase, enabling activatory immunoreceptor signaling. These SHP-1 signatures are relevant in vivo, as Lyn deficiency exacerbates nephritis and arthritis in mice, whereas Fyn deficiency is protective. Similarly, Fyn-activating signature is detected in patients with lupus nephritis, underlining the importance of this Lyn–Fyn balance. These data show how receptors discriminate negative from positive signals that respectively result in homeostatic or inflammatory conditions.

Src-family kinases Fyn and Lyn are signaling components downstream of ITAM-bearing antigen receptors. Here the authors show that by phosphorylating SHP-1 at different residues, Lyn and Fyn can have opposing regulatory effects on ITAM receptors.

Introduction

The immune system is controlled by a finely tuned network of regulatory mechanisms that maintain homeostasis or can initiate inflammatory responses1. An important axis of regulation comprises immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-containing immunoreceptors, such as the T-cell receptors (TCR) and B-cell receptors (BCR), Fc receptors (FcR)2. ITAMs are defined by two consecutive Yxx[L/I] sequences separated by 6 to 12 amino acids, and are present in the cytoplasmic domains of several transmembrane adapter molecules, such as the common γ subunit of FcR (FcRγ), the Igα and Igβ subunits of the BCR, the γ, δ, ε, and ζ subunits of the TCR-associated CD3 complex1, 3, and in FcγRIIA4. Cellular responses after FcR triggering depend on ligand avidity. Receptor clustering mediated by high avidity ligand interaction induces phosphorylation on ITAM tyrosine residues by membrane-anchored and receptor-associated Src-family kinases (SFK). Phosphorylated ITAMs are docking sites for recruitment of the tyrosine kinases Syk or Zap70, which launch inflammatory responses and restore homeostasis. However, in case of dysregulation or chronic stimulation, ITAM signal can also result in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases1, 5. Both in innate and adaptive immunity, the activation of ITAMs-bearing immune receptors is actively counteracted by the action of ITIM-bearing inhibitory receptors such as FcγRIIB with the ITIM being defined by a single [I/V/L/S]xYxx[L/V] sequence. This regulation generally involves co-aggregation of inhibitory and targeted activated receptors and is promoted through recruitment of relevant phosphatases such as Src homology region 2 domain-containing inositol 5′ phosphatases (SHIP-1 and SHIP-2)6. In addition to this inhibitory feedback targeting co-aggregated activated receptors, a continuously active inhibitory mechanism generated by ITAM-bearing receptors following low avidity interactions has been described that acts towards a whole array of activating receptors without the requirement for co-aggregation7–12. This mechanism has been named inhibitory ITAM (ITAMi) and is thought to be involved in the maintenance of homeostasis5, 13. Various FcRs, such as FcαRI, FcγRIIA, and FcγRIIIA can function as such bi-functional receptors to trigger inhibitory signals, a property that can be exploited to reduce the susceptibility to autoimmune and inflammatory diseases7–11.

Induction of FcR ITAMi signals by weakly binding ligands with low avidity depends on the recruitment of the Src homology region 2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatase SHP-113, 14. BCRs and TCRs have been also reported to recruit SHP-1 upon interaction with low avidity ligands15, 16. Moreover, deletion of SHP-1 in haematopoietic lineages, including T cells, neutrophils, and dendritic cells, is associated with a variety of pathologies17–20. Together, these evidences support an important role of SHP-1 in the maintenance of immune homeostasis.

SFKs, such as Lyn and Fyn, are implicated in the initiation of ITAM-receptor-mediated signaling. These kinases are responsible for ITAM phosphorylation upon receptor aggregation leading to Syk recruitment initiating further signal propagation via downstream effectors such as PI3-kinase and phospholipase C-γ13, 21. In B cells, Lyn was reported to have both positive and negative roles in BCR-mediated signaling22. Aged Lyn-deficient mice have high levels of serum immunoglobulins (including autoantibodies) and their B cells are hyper-responsive to IL-4 and CD40 engagement23–25 demonstrating a defective homeostasis due to a deficient negative regulation. Therefore, the individual function and coordination of Lyn and Fyn in the control of ITAM signaling pathways mediated by the engagement of FcRs or BCRs by either high or low avidity ligands is unclear.

Here we report that Lyn and Fyn have important and non-redundant roles in the ligand-sensing threshold between ITAM and ITAMi signals mediated by immunoreceptors, able to differentially translate outside ligand interactions into opposite signals. Our results show that, although Lyn is crucial in coupling to ITAMi signals, Fyn is the essential effector molecule coupling to ITAM signals following FcR, but also BCR, engagement. This ITAM switch involves a capacity to differentially control SHP-1 by shifting its phosphorylation status. These signaling signatures are confirmed in inflammatory and auto-immune diseases involving an imbalance between ITAM and ITAMi signals.

Results

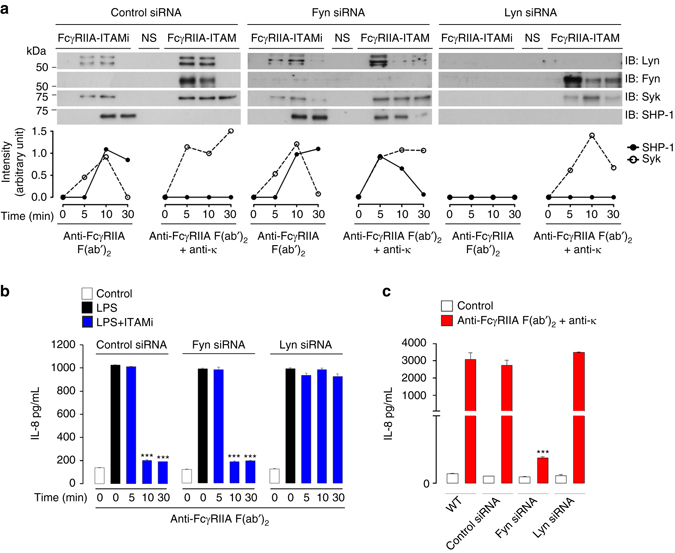

Lyn and Fyn differentially regulate FcR-ITAM signals

In order to address whether SFKs play a role in the switch between ITAMi or ITAM signaling, we first downregulated Fyn or Lyn expression in representative human monocytic cell lines by a siRNA strategy. The cells were then stimulated for ITAMi signaling by divalent targeting, or for ITAM signals by multivalent crosslinking of FcγRIIA or FcαRI as described previously7, 11. The ITAMi molecular signature was characterized by transient Syk recruitment followed by stable and prolonged SHP-1 recruitment. This required the presence of Lyn but not Fyn. In contrast, multivalent crosslinking of these receptors inducing an ITAM activation signal molecular signature with a stable recruitment of Syk (but not SHP1), required the recruitment of Fyn (Fig. 1a and, Supplementary Figs. 1a and 2a, left panel). Fyn silencing had no effect on ITAMi signaling but reversed the ITAM to an ITAMi signature by the recruitment of SHP-1 to the receptors despite their multivalent crosslinking (Fig. 1a and, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2a, middle panel). Lyn silencing completely abolished the ITAMi signaling without affecting the ITAM activation signal (Fig. 1a and, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2a, right panel). Syk silencing did not alter the recruitment of Lyn or Fyn to the FcγRIIA (Supplementary Fig. 3a) but affected SHP-1 recruitment under ITAMi conditions as previously shown11. Functional consequences of individual SFK silencing were then evaluated. Lyn but not Fyn was essential for the ITAMi-dependent FcR-mediated inhibition of LPS-induced IL-8 production (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 2b). By contrast, Fyn but not Lyn was essential for ITAM-dependent cell activation as measured by IL-8 production after multivalent engagement of FcγRIIA (Fig. 1c) or FcαRI (Supplementary Fig. 2c). To address whether other SFK could compensate for ITAM signals, we first silenced both Lyn and Fyn expression in transfected monocytic cell line THP-1-CD14+-FcγRIIA+. This abolished both the ITAMi-signal-inhibiting heterologous TLR4 receptor and the ITAM-mediated IL8 production following crosslinking of FcγRIIA (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). This was confirmed by Western blot analysis of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins in THP-1 whole cell lysates after ITAMi or ITAM induction (Supplementary Fig. 4g, h) ruling out a compensation by other SFK of Lyn/Fyn absence. In agreement, silencing expression of Hck, Fgr, or both, had no significant effect on ITAMi and ITAM signaling (Supplementary Fig. 4d–h). These results reveal opposing roles of the SFK Fyn and Lyn, transducing, respectively, activating or inhibitory signals depending on the type of ligand interaction.

Fig. 1.

Differential regulation of FcR-ITAM signals by Lyn and Fyn. a After induction of FcγRIIA-ITAMi or ITAM signalling in THP-1-CD14+-FcγRIIA+ cells transfected with indicated siRNAs, immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblots (IB) were performed with indicated Abs. Quantification of the indicated band using ImageJ software relative to total corresponding protein levels in cell lysates (see Supplementary Fig. 1) is indicated at the bottom of each panel, representing one out of at least three experiments. b Modulation of LPS-mediated IL-8 production by Lyn and Fyn during FcγRIIA-ITAMi induction. THP-1-CD14+-FcγRIIA+ cells transfected with indicated siRNAs were stimulated for indicated time points to induce either ITAMi or ITAM signals followed by stimulation with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 1 h. Then, supernatant was collected for cytokine measurement. c Modulation of IL-8 production by Lyn and Fyn during FcγRIIA-ITAM induction for 18 h. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. ***P < .001; Student’s unpaired t-test

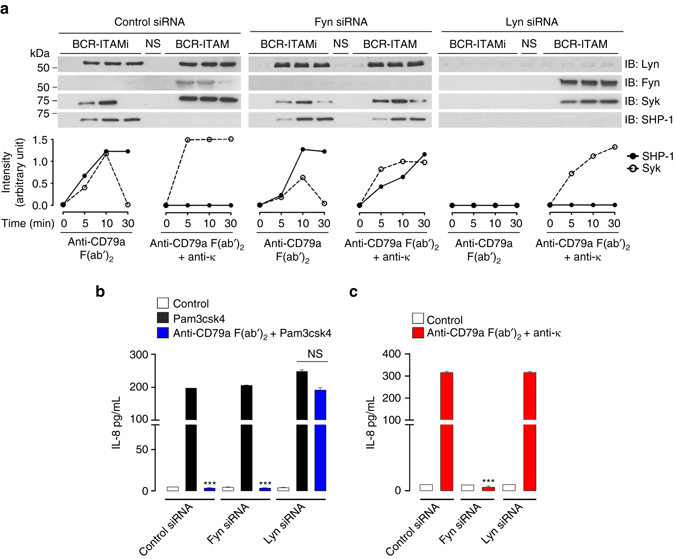

Distinct SFKs differentially regulate BCR-ITAM signals

To investigate whether other Lyn/Fyn-associated ITAM-bearing receptors could also deliver such opposite signals, divalent or multivalent targeting of BCR were performed using anti-CD79a F(ab′)2 fragments alone or complexed with anti-κ light chain antibodies in representative lymphocytic cell lines expressing siRNA for Lyn or Fyn. Similar to FcRs, divalent targeting of BCR resulted in typical ITAMi molecular signatures, while multivalent crosslinking led to the expected molecular signature of ITAM activation signal (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Furthermore, in agreement with the results obtained with FcRs, BCR-mediated ITAMi signals required Lyn, whereas Fyn was essential for ITAM activation signals. Since Syk is recruited with SHP-1 during the ITAMi signaling, we knocked-down Syk expression by using siRNA to determine its role in SHP-1 recruitment to the BCR. The silencing of Syk expression impaired the recruitment of SHP-1, but not of Lyn, to the BCR induced by anti-CD79a F(ab′)2 fragments. However, Syk silencing had no effect on Fyn recruitment under BCR-ITAM induction (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Altogether these findings suggest that BCR-ITAMi inhibitory signaling pathway sequentially involves Syk and SHP-1, as previously described for ITAMi signaling of FcRγ-associated Fc receptors7, 11. We next assessed whether BCR could also induce ITAMi functional signals following low avidity engagement. Thus, we examined whether they could inhibit functional responses induced by heterologous receptors such as TLR-induced cytokine production. The results clearly show that BCR-divalent targeting inhibited cytokine production induced by heterologous receptors, and this required Lyn (Fig. 2b). By contrast, Fyn was required for autologous cytokine production after BCR multivalent engagement (Fig. 2c). These results demonstrate that, similar to FcRs, ITAMi signaling by BCR is able to induce an inhibitory crosstalk with other receptors thereby dampening inflammatory responses without co-ligation between heterologous receptors. They explain previous observations concerning the triggering of negative signals by the binding of low avidity ligand or antibodies to the BCR26.

Fig. 2.

Differential regulation of BCR-ITAM signals by Lyn and Fyn. a After induction of BCR-ITAMi or ITAM signalling in transfected Ramos B cells, immunoprecipitation (IP) and immunoblots (IB) were performed with indicated Abs. Quantification of the indicated band using ImageJ software relative to total corresponding protein levels in cell lysates is shown at the bottom of each panel, representing one out of at least three experiments. b Modulation of Pam3csk4-mediated IL-8 production by Lyn and Fyn during BCR-ITAMi signalling on transfected Ramos B cells were stimulated for 30 min to induce ITAMi signal followed by stimulation with Pam3csk4 (1 µg/ml) for 6 h. Supernatants were collected for cytokine measurement. c Modulation of IL-8 production by Lyn and Fyn on transfected Ramos B cells after induction of BCR-ITAM signaling for 6 h. Supernatants were collected for cytokine measurement. For all, data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. n = 3. ***P < .001; Student’s unpaired t-test. NS, not stimulated

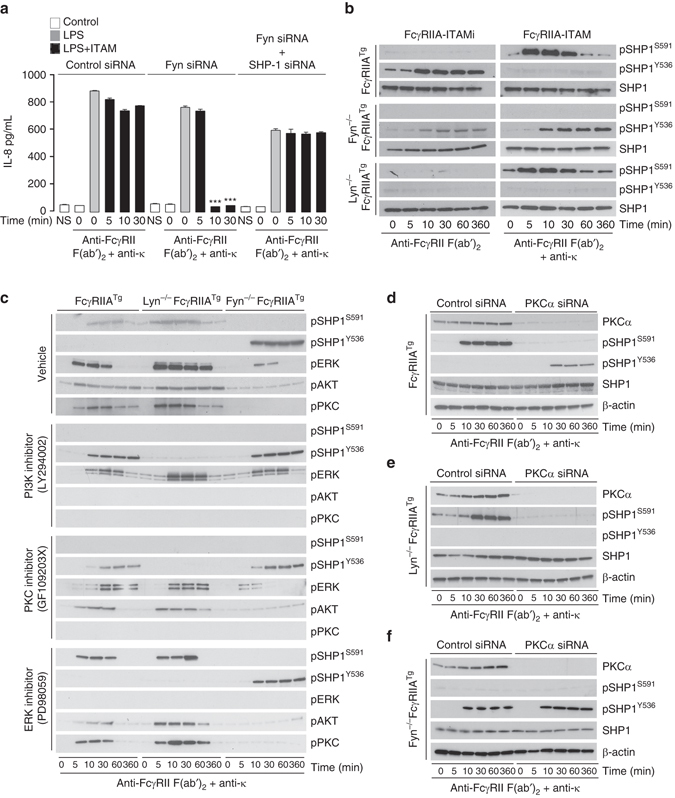

SFKs differentially control SHP-1 phosphorylation

To address the mechanism by which Lyn regulate ITAMi signaling, we took advantage of our findings that Fyn deletion reverses ITAM activation signals into ITAMi signals to explore a possible link between SHP-1 and Fyn under ITAM-activating configuration. Although Fyn silencing resulted in an inhibitory signal generated by multivalent targeting of FcγRIIA, the silencing of both SHP-1 and Fyn abolished it (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 5a), indicating that Fyn abrogates an SHP-1-mediated inhibitory signal. Previously, phosphorylation of SHP-1 on Y536 and S591 residues has been associated with its activation and inactivation, respectively27, 28. Hence we analyzed whether Lyn and Fyn could control SHP-1 function through differential phosphorylation of this phosphatase. Stimulation of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) from FcγRIIATg (R131 isoform) mice29 under ITAMi conditions showed that Lyn induced SHP-1 Y536 phosphorylation. By contrast, receptor multivalent aggregation induced a Fyn-dependent SHP-1 S591 phosphorylation (Fig. 3b). Under these stimulation conditions if Fyn was absent, a Lyn-dependent Y536 phosphorylation of SHP-1 was observed instead, thus mimicking an ITAMi signal (Fig. 3b). To understand how Fyn, a tyrosine kinase, could promote SHP-1 serine phosphorylation, we performed FcγRIIA-ITAM multivalent aggregation in the presence or absence of ERK, PKC, and PI3K inhibitors30, 31. Whereas PI3K and PKC inhibitors completely blocked both SHP-1S591 and PKC phosphorylation, the ERK inhibitor had no effect (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 5b). In addition, both PI3K and PKC inhibitors favored SHP-1Y536 phosphorylation under conditions of FcγRIIA-ITAM activation signaling, and this preference required the presence of Lyn (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 5b). Interestingly, silencing of the PKCα isoform also abrogated SHP-1S591 phosphorylation under conditions of FcγRIIA multimeric aggregation and favored SHP-1Y536 phosphorylation (Fig. 3d), which was Lyn-dependent (Fig. 3e). However, PKCα silencing had no effect on the phosphorylation status of SHP-1 observed in the absence of Fyn (Fig. 3f). Moreover, PI3K inhibition or PKC-α silencing did not impair Syk activation following FcγRIIA-ITAM induction in the presence or absence of Lyn or Fyn (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Together, these results indicate that during ITAM-induced activation signals, Fyn inactivates SHP-1 through phosphorylation of the S591 involving a PI3K–PKCα axis, thereby blocking its activation by Lyn. Our results demonstrate that Lyn is crucial to maintain ITAMi-mediated homeostasis, whereas Fyn is essential for ITAM-mediated cell activation by inducing the PI3K–PKCα signaling axis that inactivates SHP-1 during inflammatory responses for most immunoreceptors.

Fig. 3.

Fyn–PI3K–PKCα axis inactivates SHP-1-mediated ITAMi signaling. a Modulation of LPS-mediated IL-8 production by Lyn or Fyn after induction of FcγRIIA-ITAM signal on transfected THP-1. Cells were stimulated with LPS for 1 h at 37 °C after induction of ITAM as described in Fig. 1a. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. ***P < .001; Student’s unpaired t-test. b After induction of FcγRIIA-mediated ITAMi or ITAM signals on BMDM derived from FcγRIIA transgenic mice or from FcγRIIATg under Lyn-deficient or Fyn-deficient backgrounds. Cell lysate samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblots were performed using anti-phospho (p) SHP-1 serine 591 (S591) or tyrosine 536 (Y536) Abs. c Effect of PI3K, PKC, and ERK inhibitors on SHP-1 phosphorylation driven by ITAM signals in BMDMs. Cells were pre-treated with inhibitors as indicated and Western blotting was performed on cell lysates using antibodies anti-phosphorylated (p) kinases and phosphatases as indicated. Total protein contents in cell lysates were shown in Supplementary Fig. 3,b. d–f Involvement of PKCα on serine SHP-1 phosphorylation following FcγRIIA-ITAM signal. BMDMs from FcγRIIATg (d), Lyn-deficient FcγRIIATg (e), or Fyn-deficient FcγRIIATg (f) mice were transfected with indicated siRNAs before induction of FcγRIIA-ITAM as described in Fig. 1a. b–f Are representative of three experiments. NS, not stimulated

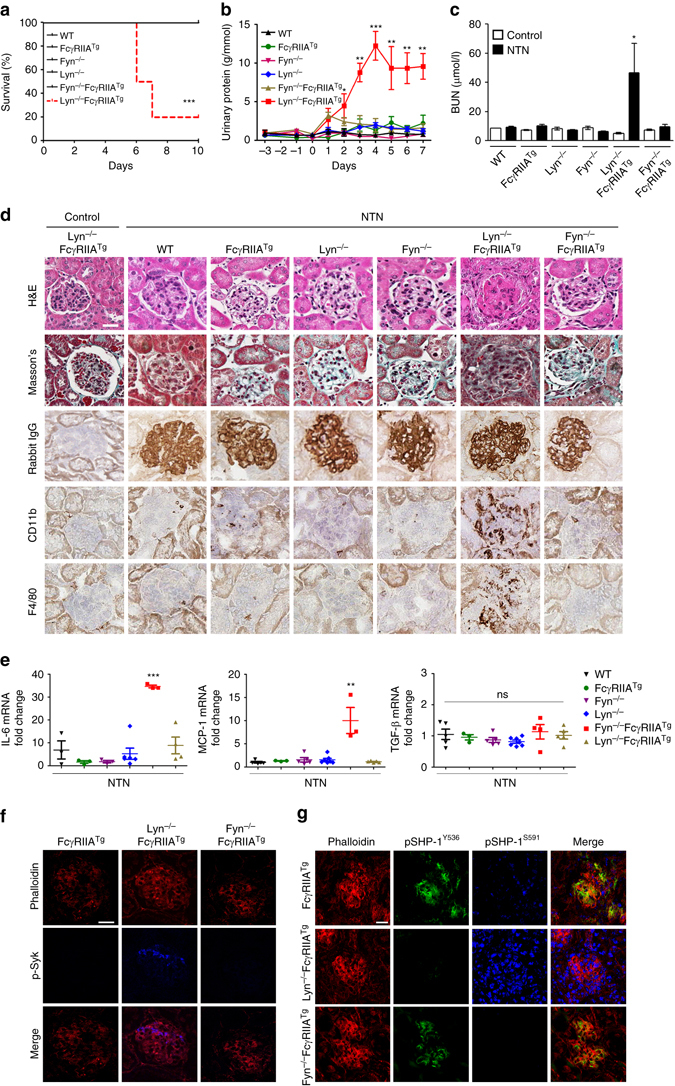

Opposing control of SHP-1 activity regulates inflammation

To investigate the functional role of Lyn and Fyn in the regulation of ITAM signals in vivo, we employed a mild immune-complex nephrotoxic nephritis (NTN) model via administration of a rabbit anti-mouse glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) serum. A mild NTN model was chosen because FcγRIIATg and Lyn-deficient mice have a pre-established autoimmune phenotype23, 25, 29. Consistent with the above-described role of Lyn in maintaining ITAMi-mediated immune homeostasis, i.p. administration of the NTN serum led to a severe acute nephritis associated with high mortality at day 7 in Lyn-deficient FcγRIIATg recipients, whereas mice deficient for Lyn or Fyn and Fyn-deficient FcγRIIATg mice did not develop significant disease despite similar glomerular rabbit antibody deposits and no significant differences in mouse IgG anti-rabbit IgG responses (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 6a). Renal disease development in Lyn-deficient FcγRIIATg mice was characterized by a marked increase in urinary protein (Fig. 4b) and blood urea nitrogen concentration (BUN) (Fig. 4c). They also exhibited severe renal injury involving extensive mesangial and capillary (subendothelial or even intracapillary) deposits associated with mild mesangial and endocapillary plus extra-capillary proliferation (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 6b–d). Glomerular lesions were characterized by an intense macrophage infiltrate and cytokine production (Figs. 4d, e and Supplementary Fig. 6e). These effects involved ITAM activation signaling, as demonstrated by in situ phosphorylation of the Y525 residue in Syk (Fig. 4f). This was associated with a strong in situ phosphorylation of SHP-1 on the inhibitory S591 residue but not on Y536 (Fig. 4g, middle panels). Moreover, no involvement of SHIP-1-mediated inhibitory signaling by macrophage FcγRIIB was observed in situ after NTN induction in FcγRIIATg mice, as glomerular immunofluorescence stainings with anti-phospho SHIP-1 antibody were completely negative (Supplementary Fig. 7). By contrast, NTN induction in Fyn-deficient FcγRIIATg mice led to in situ phosphorylation of SHP-1 on Y536 but failed to induce S591 phosphorylation, and this was associated with no renal inflammation despite the presence of antibody deposits on the glomerular membrane (Fig. 4g, bottom panels). Interestingly, the same observations were made in 8-week-old FcγRIIATg mice (Fig. 4g, top panels). These results suggest that the absence of Fyn in vivo may protect against autoimmune disease development favoring the activating phosphorylation of SHP-1 on tyrosine residue.

Fig. 4.

Lyn-SHP-1Y536 axis protects mice against lethal nephritis. a Survival curves, b proteinuria, and c serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN) after NTN induction. d Rabbit IgG deposit quantification by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (top panels), haematoxylin & eosin (H&E), and fibrosis Masson’s stain (middle panels) of kidney sections from one representative out of nine mice. Immunostaining for CD11b+ and F4/80+ cells in kidney sections of the indicated mouse lines (bottom panels). e Relative gene expression of indicated cytokines assessed by q-PCR of independent kidney tissue RNA samples. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; Mann–Whitney test. Non significant, ns. Data are from at least five mice per group. f Representative photomicrographs of glomeruli stained for phalloidin and p-Syk-Alexa 647. g Representative photomicrographs of glomeruli stained for phalloidin, p-SHP-1S591-Alexa 647 and pSHP-1Y536-Alexa 488. Scale bars: 200 μm

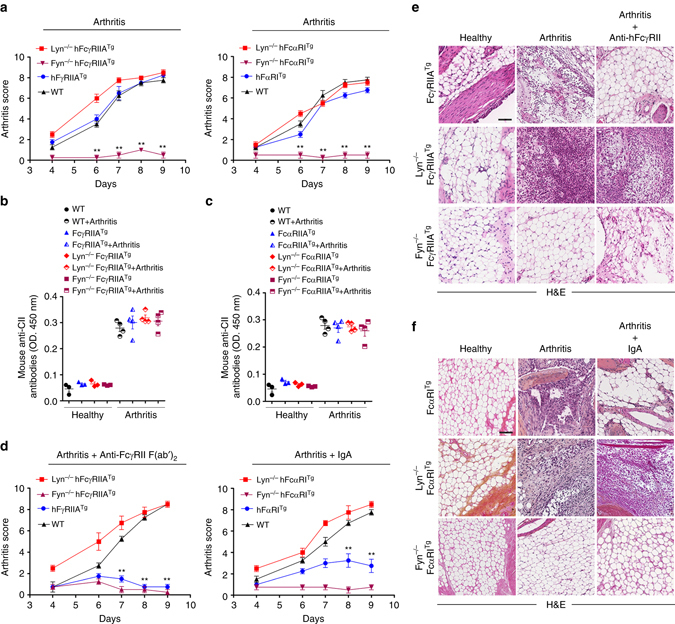

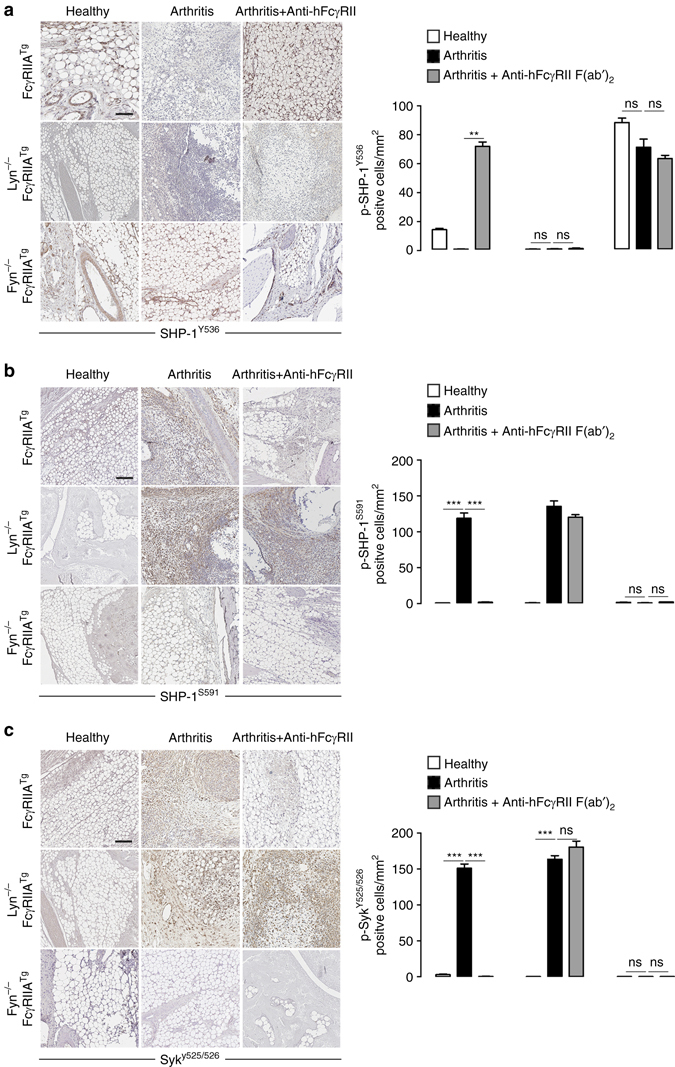

To investigate the aggravating role of Fyn in inflammatory disease development, we took advantage of another autoimmune disease model, namely the collagen antibody-induced arthritis (CAIA) using two transgenic animals expressing either hFcγRIIA or hFcαRI. The aggravating role of Fyn was highlighted by the absence of lesions in both Fyn-deficient FcγRIIATg and Fyn-deficient FcαRITg mice despite similar serum levels of injected mouse anti-collagen antibodies (Fig. 5a–f). By contrast, Lyn-deficient FcγRIIATg and Lyn-deficient FcαRITg mice showed enhanced arthritis development characterized by leukocyte infiltration (Fig. 5a–f). To determine whether targeting ITAMi could have a therapeutic value, we treated transgenic animals expressing human FcγRIIA or FcαRI for ITAMi signaling with anti-FcγRII F(ab′)2 or monomeric hIgA, respectively, as previously described11, 32. ITAMi induction prevented disease development, and this protection required the presence of Lyn but not Fyn (Fig. 5d–f). We next addressed the role of the different phosphorylated forms of kinases and phosphatases in joints of arthritic FcγRIIATg mice. While Lyn protected the host against autoimmunity by inducing a constitutive phosphorylation of SHP-1Y536 residue, Fyn favored autoimmunity by inactivation of SHP-1 through the phosphorylation of the SHP-1S591 residue associated with induction of SykY525–526 phosphorylation (Fig. 6a–c). Moreover, induction of ITAMi by anti-FcγRIIA targeting was associated with in situ detection of Lyn-dependent pSHP-1Y536, but not pSHP-1S591 (Fig. 6a–c). Altogether, these results support that non-redundant SFKs are crucial in dictating ITAMi/ITAM balance that controls homeostasis as well as inflammatory and autoimmune disease development.

Fig. 5.

Fyn axis is essential for arthritis development. a Fyn-deficient mice failed to develop autoimmune arthritis following induction of the CAIA model both in hFcγRIIATg and hFcαRITg background. Arthritis score was graded blind as 0 (normal), 3 (mild), 6 (moderate), or 9 (severe). b, c Circulating levels of CII-specific antibodies in individual sera from WT, FcγRIIATg (b) and from FcαRITg (c) mice on the indicated backgrounds at day 10 after injection of antibodies. Mean ± s.e.m. (n = 4) (d) Lyn is essential for FcR-ITAMi-mediated protection of arthritis. Arthritis score evaluated as in a. e, f H&E staining of hind paws from representative indicated mice at day 10. Scale bars: 200 µm. Mean ± s.e.m (n = 8). **P < .01; two-way ANOVA test

Fig. 6.

Inactive SHP-1S591 is linked to arthritis development. a–c Immunostaining for the detection of phospho SHP-1Y536 (a), phospho SHP-1S591 (b), and phospho SykY525–526 (c) in hind leg sections of indicated mice subjected or not to the CAIA model. The corresponding quantifications of positive cells for phospho-SHP-1 on Y536 or S591 and phospho-Syk Y525/526 are shown on the right of each panel. Scale bars: 200 µm. **P < .01, ***P < .001; non significant ns, Mann–Whitney test. Sections of three mice/group were automatically quantified with the software CaloPix piloted in a blind manner. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m (n = 5)

Fyn-SHP-1S591 axis is linked to lupus nephritis activity

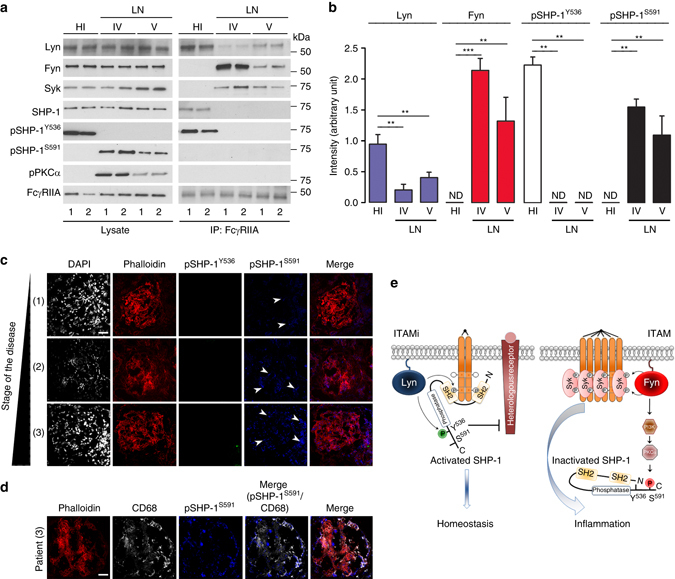

To examine whether Fyn-mediated inhibitory SHP-1S591 phosphorylation were associated with immune complex-mediated disease via the FcγRIIA in patients with a given inflammatory disease, we analyzed blood leukocytes from untreated patients with lupus nephritis at different stages of renal involvement morphologically classified as class IV-A (severe nephritis with immune deposits and leukocyte infiltration) and pure class V (membranous immune deposits only). As shown in Fig. 7a, b, pSHP-1S591 and pPKCα were exclusively observed in patient cell lysates, and were not associated with FcγRIIA. Consistent with the role of Lyn/SHP-1 axis in homeostasis, Lyn and pSHP-1Y536 were strongly associated with FcγRIIA in healthy individuals only, underlining the inhibitory ITAM homeostatic phenotype, whereas Fyn and Syk were exclusively associated with FcγRIIA in patients highlighting the deleterious role of ITAM signaling in this inflammatory disease. Moreover, tissue analysis of phosphorylated phosphatases in situ of renal biopsies from untreated patients with lupus nephritis at different stages of disease show that the phosphorylation status of SHP-1S591 residue was linked to disease activity in proximity of phalloidin+ renal cells (Fig. 7c). No phosphorylation of SHP-1Y536 was detected on patient kidney biopsies. However, in control experiments, pSHP-1Y536 intracellular immunofluorescence staining was observed in THP-1 cells after FcγRIIA-ITAMi induction using the same antibody and, inversely, pSHP-1S591 was only detected after FcγRIIA-ITAM-induction (Supplementary Fig. 8). As some pSHP-1S591-positive glomerular areas were negative for phalloidin, we next examined leukocyte markers for pSHP-1S591 co-expression in biopsies from three patients with lupus nephritis with high disease activity. Figure 7d shows a representative biopsy revealing that significant areas of pSHP-1S591 positivity were located in CD68+ cells but also in CD68− cells. These results indicate that macrophages, which are present in the inflamed glomeruli express inactive SHP-1 in their cytosol. Moreover, in situ phosphorylation of SHP-1S591, but not of SHP-1Y536, was associated with spontaneous severe nephritis in 1-year-old pro-autoimmune R131 FcγRIIATg mice (Supplementary Fig. 9a–f). This end-stage chronic kidney disease was characterized by enhanced body weight, increased BUN levels, glomerular IgG deposits, sclerotic glomeruli, fibrosis, and kidney interstitial infiltration by CD11b + , F4/80 + and CD3 + cells and increased expression of mRNA coding for proinflammatory cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 9a–e). In this model pSHP-1S591 was detected in situ, whereas pSHP-1Y536 was detected in the kidney of WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 9f). Altogether, these results support that the type of the phosphorylation of SHP-1 (Y536 vs. S591 residues) determines the shift between the healthy and autoimmune status and can be used as novel biomarkers for lupus disease activity.

Fig. 7.

Fyn-SHP-1S591 axis as a biomarker of lupus nephritis activity. a Analysis of phosphorylated ITAM effectors in blood leukocyte samples from 4 lupus nephritis (LN) patients (1 and 2 are class IV; 3 and 4 are class V) and four healthy individuals (HI). Left panel, cell lysates were immunoblotted using indicated Abs. Right panel, FcγRIIA immunoprecipitation (IP) with an anti-FcγRIIA monoclonal antibody (IV.3) followed by immunoblotting using indicated antibodies. b Quantification of the indicated band using ImageJ software relative to total levels of the corresponding protein in cell lysates. *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001; Mann–Whitney test. Not detectable (ND). Data are mean ± s.e.m (n = 5). No significant differences in blood phagocyte counts were observed between healthy controls and patients as followed: Monocytes 0.50 ± 0.16 vs. 0.49 ± 0.30; Neutrophils 4.0 ± 0.42 vs. 3.4 ± 2.4, ×106/ml, respectively. c Representative photomicrographs of glomeruli stained from biopsies of lupus nephritis patients for phalloidin (red), p-SHP-1S591-Alexa 647 (blue), and pSHP-1Y536-Alexa 488 (green). Scale bars: 200 μm. d Representative photomicrographs of glomeruli stained from biopsies of LN patients for phalloidin (red), p-SHP-1S591-Alexa 647 (blue), and CD68-Alexa 405 (white). Scale bars: 200 μm. e Predicted model for the Lyn and Fyn switch controlling the balance between inhibitory or activating ITAM signals in immunoreceptors. Left panel: upon divalent targeting of immunoreceptors, Lyn is recruited to the receptor leading to receptor partial phosphorylation on tyrosine (e.g., Y304 in the case of FcγRIIA11). Simultaneously, Lyn phosphorylates SHP-1 on Y536, inducing a conformational change leading to SH2 domain recruitment to phospho-ITAM, thereby lifting inhibition of the phosphatase domain by the N-SH2 domain. This enables SHP-1 to inactivate signal effectors recruited by heterologous receptors. Right panel: multivalent crosslinking of immunoreceptors results in full phosphorylation of ITAM tyrosines by Fyn. These phosphotyrosines serve as “docking” sites for Syk, inducing cell activation and inflammatory responses. Fyn simultaneously activates the PI3K–PKCα pathway, leading to SHP-1 phosphorylation on S591. The N-SH2/phosphatase domains are maintained in a closed conformation, blocking both recruitment and activation of SHP-1. Under chronic stimulation, this may lead to aggravation of inflammatory or autoimmune diseases

Discussion

Here we characterize the mechanism by which SFKs and SHP-1 control the balance between the activating and inhibitory ITAM signaling. Initially described for their activating function, evidences have accumulated that FcRs bearing an ITAM motif could generate opposite signals, known as ITAMi. Yet, a black box remains in regard to the inhibitory signaling mechanism involved. In this study, we show that low valency aggregations of BCR by anti-CD79a F(ab′)2 fragments induced an ITAMi signal characterized by the recruitment of the phosphatase SHP-1, whereas highly multivalent aggregation induced a conventional ITAM activation signal extending the concept that dual ITAM functionality of BCR depends on the valency of the ligand. CD79a-mediated ITAMi inhibitory signals by the BCR is in agreement with previously described pathways to maintain B-cell anergy in which chronic B-cell stimulation results in ITAM monophosphorylation inducing an inhibitory signaling circuit involving SHIP-1 and Dok-133. Interestingly, monophosphorylation of FcγRIIA ITAM is also associated with ITAMi signals but with SHP-1, rather than SHIP-1, recruitment11. Whether the number of BCR adapters containing monophosphorylated ITAM is involved in the differential recruitment of phosphatases remains unclear. Our results may also explain a previous observation in which SHP-1 was found to be implicated in the regulation of BCR signaling and in the maintenance of tolerance as B cell-targeted ablation of SHP-1 led to lupus-like disease19. Taken together, these findings support the conclusion that immune receptors associated with an ITAM motif, including antigen receptors, can play a dual role as they can induce either activating (ITAM) or inhibitory (ITAMi) signaling depending on ligand avidity.

Our study further demonstrates that single receptors switch between ITAM and ITAMi signals using distinct SFKs fulfilling opposite signaling functions, such as described here for FcR and BCR. Upon divalent targeting of immunoreceptors Lyn, but not Fyn, is recruited to the receptor, leading to ITAM partial phosphorylation on tyrosine, as we previously reported for FcγRIIA11, and of SHP-1 recruitment. In contrast, upon multivalent crosslinking of FcγRIIA, Fyn but not Lyn, plays a crucial role in FcγRIIA-ITAM-mediated cytokine production. This Lyn/Fyn switch is not affected by other SFK such as Hck and Fgr. Interestingly, it has been shown that FcγRs can mediate a well-established ITAM-dependent function, the phagocytosis, in the absence of Lyn, Hck, and Fgr34, 35. Our data highlight that Lyn and Fyn are essential for ITAM responses as silencing of both SFK render the cell unresponsive for FcγRIIA activating or inhibitory stimuli.

The mechanism by which Lyn and Fyn alternatively switch ITAM-bearing receptor function relies on their control of SHP-1 phosphorylation status. It is now clear that SHP-1 phosphorylation at Y536 induces a conformational change easing SHP-1 recruitment through its SH2 domains to phosphotyrosine residues, thereby lifting the inhibition of the phosphatase domain by its N-SH2 domain36. Of note, the two SH2 domains of SHP-1 can cooperate to bind phosphotyrosines on adjacent molecules37, a configuration expected to be that of ITAMi. This recruitment would enable ITAMi-mediated SHP-1 phosphatase activity to inactivate signal effectors mobilized by heterologous receptors38. In contrast, multivalent crosslinking of immunoreceptors results in the recruitment of the SFKs Lyn and Fyn to the receptor leading to full phosphorylation of the ITAMs. These would serve as “docking” sites for Syk preventing SHP-1 recruitment, which is associated with its phosphorylation on S591 in the cytosol. Thus, Fyn but not Lyn redirects SHP-1 towards its inactivated form allowing simultaneously full ITAM phosphorylation and receptor activation signaling by Syk. As Fyn is a tyrosine, but not a serine, kinase we explored the mechanism involved. SHP-1 is constitutively associated with PKCα27. Upon cell activation, PKCα phosphorylates SHP-1 on S591 in its C terminus thereby negatively regulating the activity of this phosphatase27. Using a specific inhibitory and siRNA strategy, we found that a Fyn–PI3K–PKCα axis induced the phosphorylation of SHP-1 on S591 upon crosslinking of FcγRIIA in the presence of Fyn, despite the recruitment of Lyn. Since S591 phosphorylation on SHP-1 keeps the phosphatase in a closed conformation36, our results suggest that while S591 residue is phosphorylated by Fyn, the Y536 residue is inaccessible to Lyn. Moreover, this study demonstrates also that the absence of Fyn favors the phosphorylation of SHP-1 on Y536 in the presence of Lyn, despite the extensive crosslinking of FcγRIIA. These results indicate that the selective absence or inhibition of Fyn may abolish inflammation during autoimmune and proinflammatory processes. Whether Fyn–PI3K–PKCα axis is involved in previously described Fyn-dependent humoral responses39 remains to be demonstrated.

R131H FcγRIIA polymorphism has a strong correlation with the pathogenesis, development and increased susceptibility to several autoimmune diseases, in particular systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and rheumatoid arthritis4, 40, 41. Interestingly, similar to Lyn-deficient mice, R131H-FcγRIIATg mice develop spontaneously autoimmunity at old age, with a complex spectrum of symptoms similar to those found in human rheumatoid arthritis (erosive pannus) and SLE (antinuclear antibodies, glomerulonephritis with immune complex deposition in the renal basement membrane, pneumonitis and non-erosive arthritis)42. Several studies have reported that Lyn, but not Fyn, controls IgG-mediated or IgE-mediated systemic anaphylaxis43, 44. Our data elucidate the role of these SFKs in the development of autoimmune and proinflammatory disease. Indeed, Fyn and Lyn deletion had opposing effects on the regulation of inflammation observed in R131H-FcγRIIATg mice. In the mild model of NTN, ablation of Fyn had no effect on young mice, but that of Lyn induced lethal nephritis associated with the activation of Syk and in situ phosphorylation of SHP-1 on S591. It is unlikely that SHIP-1 plays a negative role in this model through a putative engagement of FcγRIIB on infiltrating macrophages by mouse anti-rabbit Ig antibodies anti-GBM, as no phosphorylation of SHIP-1 was observed in situ. In addition, FcγRIIB function is Lyn dependent45 and our results show that Lyn-deficient mice did not develop any severe nephritis as compared to WT mice after NTN induction. The ablation of Fyn, however, protected the R131H-FcγRIIATg or FcαRITg mice against spontaneous renal autoimmune disease and arthritis development. In agreement with our in vitro data, this was associated with the phosphorylation of SHP-1 on Y536 but not on S591 and with the inactivation of Syk. Consistent with the role of Lyn in the ITAMi-mediated homeostasis, Lyn was strongly associated with FcγRIIA in leukocytes of healthy individuals. In contrast, in lupus nephritis patients, while Lyn weakly associated to FcγRIIA, Fyn, and Syk were highly associated to the receptor. According to our in vitro and in vivo data, the recruitment of Lyn to FcγRIIA was associated with the pSHP-1Y536 in healthy individuals. On the opposite, blood leukocytes from lupus nephritis patients display a strong recruitment of Fyn to FcγRIIA, which was associated with pSHP-1S591, pPKCα and weak recruitment of Lyn. The selective targeting of Fyn activity may thus become a challenge to open new therapeutic strategies for autoimmune diseases. Moreover, the inactive form of SHP-1 (pSHP-1S591) was linked to the severity of inflammatory glomerular lesions in biopsies from lupus nephritis patients and was observed in kidneys of FcγRIIATg mice with severe spontaneous nephritis. Interestingly, intra-glomerular CD68+ macrophages in class IV lupus nephritis patients with high disease activity expressed pSHP-1S591 suggesting that SHP-1 status may contribute to disease pathogenesis by failing to downregulate FcγRIIA activity. We cannot determine from our study whether the pathogenic role for pSHP-1S591 involved infiltrating or kidney resident macrophages, as described recently46.

This study uncovers how a given receptor discriminates negative or positive signals leading to homeostatic or inflammatory conditions. SHP-1 emerges as a master molecule translating the sensing by distinct SFKs into opposite, activating, or inhibitory, signals (Fig. 7e). This mechanism is at stake in a number of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, and its targeting could have far-reaching therapeutic value.

Methods

Humans

Eighteen individuals (8 healthy individuals and 10 patients with SLE) were studied. The SLE group was composed of 10 patients attending or referred to the Bichat’s Hospital specialist nephrology unit between July 2014 and January 2016 meeting at least four ACR SLE criteria47 presenting with active disease with nephritis proven by kidney biopsy (5 at class IV and 5 at class V) and in whom peripheral blood by venepuncture was obtained immediately prior to immunosuppressive therapy administration. All patients were female with age varying between 25 and 42. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Bichat Hospital Local Research Ethics Committee and informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled. Data collection and analyses were performed anonymously.

Mice

C57BL/6 human FcγRIIATg mice expressing the WT human FcγRIIA on CD11b-positive cells were from Jackson Laboratory (JAX, Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Fyn-deficient FcγRIIATg, Lyn-deficient FcγRIIATg were obtained by the intercross of FcγRIIATg mice with mice knockout for Fyn (JAX) or for Lyn (previously described in ref. 44). All mice were of C57BL/6 strain, female gender between 8–10 weeks old. All mice carrying the FcγRIIA transgene were used as heterozygous animals. Mice were bred and maintained at the mouse facilities of the Bichat Medical School campus. All experiments were performed in accordance with the French Council of Animal Care guidelines and national ethical guidelines of INSERM Animal Care Committee (Animal Use Protocol number 75-1596).

NTN Mouse Model

NTN was induced by i.p. injection (200 μl/20 g body weight) of rabbit anti-mouse GBM in 8–10-week-old mice. Briefly, mice were preimmunized i.p. with normal rabbit IgG (0.5 mg/20 g body weight) in CFA 5 days prior to i.p. administration of NTN serum. Blood samples were collected and animals were killed at day 7 following NTN injection. Renal function parameters (urinary proteins and BUN), histological and immunohistological parameters were studied.

CAIA model

Arthritis was induced as described11, 32 using the Arthrogen-CIA Arthritogenic Monoclonal Antibody kit (Chondrex, Inc.). Mice were injected i.v. with anti-CII Ab cocktail (Day 0) followed by LPS (i.p.) 3 days later. Animals were injected i.p. with 10 mg/20 g body weight of 500 μg serum human IgA (purchased from Biomedicals)/20 g body weight or 100 µg AT-10 F(ab′)2 or irrelevant mAb F(ab′)2 (clone 320) for 10 days at 2-day intervals. The first dose was administered 2 days prior to anti-CII Ab cocktail injection. Paw thickness was measured with a pocket thickness gauge. On day 10, animals were sacrificed and hind paws and knees were fixed in formalin or snap-frozen.

Cells and reagents

THP-1 (ATCC, catalog # TIB-202) and THP1-FcγRIIA-R131+-CD14+ cell lines (kindly provided by Novimmune)48 were maintained in RPMI-1640, 10% FCS and 50 µM β-mercaptoethanol or supplemented with 200 µg/ml Zeocin, 10 µg/ml blasticidin and 2 µg/ml puromycin (Invitrogen, France). Ramos human cell line (Invivogen, catalog # rms-sp) was maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and antibiotics. FCS was removed from the culture medium immediately before stimulation. Human blood samples (12 ml) were first submitted to red cell lysis and pellets of 107 leukocytes were subjected RIPA buffer treatment (see below). BMDM from 6-week-old to 8-week-old mice were obtained after a 7-day culture with M-CSF (R&D systems). Cell lines (THP-1 and Ramos as well as transfectants) were studied. For reagents: Mouse mAbs anti-human FcγRII (clones IV.3 and AT-10), anti-human CD79a (clone ZL7-4) were purchased from Santa Cruz and used in their F(ab′)2 fragment forms. Mouse mAb anti-human FcαRI (clone A77) and control mAb (320) were purified in-house and were used as F(ab′)2, as previously described7, 11. For biochemical studies, rabbit polyclonal anti-Syk, anti–SHP-1, anti-Lyn, anti-Fyn, anti-ERK (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog # sc-1077, sc-287, sc-15, sc-16 and sc-153, respectively) at dilution 1/500 in 5% w/v nonfat dry milk, anti-SHP1 (phospho–Y536) (ECM Biosciences, catalog # SP1571) at dilution 1/1000 in 5% w/v nonfat dry milk, anti-SHP1 (phospho–S591) (Abcam, catalog # ab41436) at 1/1000 in 5% w/v BSA and rabbit polyclonal anti-phosphotyrosine (Upstate, catalog # 06-427) antibodies were used. Anti-pERK, anti-pAKT, anti-pPKCα, anti-AKT, and anti-PKCα were from Cell Signalling and catalog # 4377, 4060, 9375, 9272, and 2056, respectively.

Cell stimulation

For ITAMi signaling, 5 × 106 of monocytic cell lines (THP-1-CD14+-FcγRIIA+ or THP-1-CD14+), and Ramos B cell lines (transfected with different siRNA) were incubated for 30 min with 10 µg/ml of anti-FcγRIIA (clone IV.3) or anti-CD79a (clone ZL7-4) F(ab′)2 fragments at 37 °C, respectively. Cells were then incubated with or without LPS (10 ng/ml) as described8 or Pam3csk4 (1 µg/ml) for 1 h for monocytic cell lines and 18 h for Ramos. For ITAM signaling, cells were incubated with 10 µg/ml of anti-FcγRIIA (clone IV.3) or anti-CD79a (clone ZL7-4) F(ab′)2 at 4 °C followed by an anti-κ light chain F(ab′)2 at 37 °C for 18 h for cytokine measurement. For kinase inhibitor experiments, cells were incubated overnight with inhibitors for kinases such as PI3K (LY294002), ERK (PD98059) (both from Cell Signaling Technology), and PKC (GF109203X) (from Sigma Aldrich) or with vehicle alone (1:1000 diluted DMSO in PBS), followed by induction of FcγRIIA-mediated ITAM signals.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

Cells (5 × 106 to 107) were solubilized in RIPA lysis buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40/0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) as described8. For immunoprecipitation, cell lysates were incubated with 2 μg/ml of IV.3 anti-FcγRIIA, A77 anti-FcαRI or ZL7-4 anti-CD79a mAbs and immunoprecipitated overnight at 4 °C with Protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare). Samples were resolved by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10%), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and immunoblotted with rabbit antibodies followed by goat anti-rabbit IgG (GE Healthcare) coupled to horseradish peroxidase. Membranes were developed by enhanced chemical luminescence treatment (Amersham Biosciences). All uncut Western blots are available in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

IL-8 was measured in the supernatants of stimulated cells using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Anti-type I and II collagen mouse IgG antibodies were measured by an ELISA kit with TMB according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Chondrex, Inc, Catalog # 2036 T).

Real-time PCR

RNA purification from homogenized kidneys was performed by using RNAble (Eurobio). cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription using Moloney murine leukaemia virus (Invitrogen). Samples were analyzed by real-time PCR with Taq Man Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystem). Primers were purchased from Eurofins. Gene quantification was performed using a Chrom o4 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Data were normalized to β-actin values. For primers and probe sequences see Supplementary Table 1.

siRNA transfections

Experiments were performed using predesigned HP GenomeWide (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) siRNAs. For targets DNA sequences and siRNAs sense and anti-sense see Supplementary Table 2. Single-strand sense and antisense RNA nucleotides were annealed to generate an RNA duplex according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell lines were incubated with 5–10 nM of each siRNA tested and 2 µl of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Saint Aubin, France) for 48 or 72 h at 37 °C before use. BMDMs were incubated at day 4 during M-CSF-induced differentiation with 20 nM of each siRNA tested and 2 µl of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Saint Aubin, France) for 48 h at 37 °C before use.

Histological and immunofluorescence analyses

For the kidney, paraffin-embedded sections 4 µm in thickness were stained with PAS for morphological analysis. For immunohistochemistry, frozen kidney sections were incubated with biotinylated antibodies against rabbit IgG or monoclonal antibodies anti-mouse CD11b, anti-mouse F4/80, anti-mouse CD3, and anti-mouse Ly6G (Becton Dickinson) for 1 h at room temperature. When necessary, the primary antibody incubation was followed by incubation with anti-rabbit IgG or anti-goat IgG (Southern Biotech Associates). Slides were mounted with the Eukitt mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and read with an upright microscope (DM2000; Leica) using the IM50 software (Leica). For colocalization experiments, frozen kidney sections were incubated overnight successively with each antibody (anti-phospho SykY525–526 AF488 (Cell Signalling) and anti-phalloidin AF568 (Life Technologies) followed by incubation with streptavidin-Alexa Fluor 488 (Life Technologies) at room temperature. Tissue sections were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). Slides were read with a laser-scanning confocal microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss) using a 63× objective and the LSM Image Browser (Carl Zeiss). For formalin-fixed hind paws and mouse knees, the samples were decalcified and embedded in paraffin. Sagittal sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Histological score of peri-articular exudates, synovitis and tissue loss were graded as 0 (normal), 3 (mild), 6 (moderate), or 9 (severe). The cumulative score of all features was used as histological score to represent overall disease severity. Analyses were made in a blind manner. Sections were incubated with rabbit primary antibodies against mouse phospho (p)-Syk (Y525-526)49, mouse p-SHP1 (S591) (both from Abcam), or p-SHP1 (Y536) (Assay Biotech). The presence of antibodies was detected with biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody (Southern Biotech) followed by peroxidase streptavidin and diaminobenzidine successive stains. Positive cells were quantified in hind paw sections with analysis software CaloPix (TRIBVN, Chatillon, France) after scanning with Aperio ScanScope CS (Leica Biosystems, Nanterre, France). For immunofluorescence studies, frozen kidney slides or cytospined cells were incubated in blocking buffer (PBS, 0.3% saponine, 1% BSA) for 30 min, and then with anti-phospho SHP-1Y536 AF488, SHP-1S591 AF647 (Bioss Antibodies, 1/50 dilution), anti-CD68 AF405 (Life Technologies 1/50 dilution), and anti-Phaloidin AF568 (Life Technologies,1/100 dilution) for 2 h. Fluorescence was detected by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM-510-META, Zeiss).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance between two groups was examined by the Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney test, while the one-way and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni’s, Holm–Sidak’s, or Newman–Keuls multiple comparisons test were used to evaluate multiple groups. Sample sizes were higher than five per group. P-values of 0.05 were considered significant; values <0.05 are indicated in the figure legends.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from ANR (MIEN-2009 and BLANC International-2012) and from LabEx Inflamex (ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02). S.B.M. was supported by a grant from the French Foundation ARC (PDF20100601037). R.C.M. is supported by ≪ Equipe ≫ program of the Fondation pour la recherche médicale (FRM). We thank Marieke Heineke and Loredana Saveanu critical reading of this manuscript, and Julie Bex and Erwan Boedec for animal care. We are indebted to the patients and healthy volunteers who participated in the study.

Author contributions

S.B.M. and R.C.M. designed experiments. S.B.M. performed experiments. A.M., H.F., D.T.-B., L.D. and C.B. contributed to experiments. E.D. provided human samples and performed analyses of morphological data. S.B.M. and R.C.M. wrote the manuscript. P.L., M.B., U.B. and N.C. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00294-0.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sanae Ben Mkaddem, Email: sanae.benmkaddem@inserm.fr.

Renato C. Monteiro, Email: renato.monteiro@inserm.fr

References

- 1.Bezbradica JS, Medzhitov R. Role of ITAM signaling module in signal integration. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012;24:58–66. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamerman JA, Lanier LL. Inhibition of immune responses by ITAM-bearing receptors. Sci. STKE. 2006;2006:re1. doi: 10.1126/stke.3202006re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reth M. Antigen receptor tail clue. Nature. 1989;338:383–384. doi: 10.1038/338383b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hogarth PM. Fc receptors are major mediators of antibody based inflammation in autoimmunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2002;14:798–802. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(02)00409-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Getahun A, Cambier JC. Of ITIMs, ITAMs, and ITAMis: revisiting immunoglobulin Fc receptor signaling. Immunol. Rev. 2015;268:66–73. doi: 10.1111/imr.12336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolland S, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory pathways triggered by ITIM-containing receptors. Adv. Immunol. 1999;72:149–177. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60019-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasquier B, et al. Identification of FcalphaRI as an inhibitory receptor that controls inflammation: dual role of FcRgamma ITAM. Immunity. 2005;22:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinheiro da Silva F, et al. CD16 promotes Escherichia coli sepsis through an FcR gamma inhibitory pathway that prevents phagocytosis and facilitates inflammation. Nat. Med. 2007;13:1368–1374. doi: 10.1038/nm1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanamaru Y, et al. Inhibitory ITAM signaling by Fc alpha RI-FcR gamma chain controls multiple activating responses and prevents renal inflammation. J. Immunol. 2008;180:2669–2678. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aloulou M, et al. IgG1 and IVIg induce inhibitory ITAM signaling through FcgammaRIII controlling inflammatory responses. Blood. 2012;119:3084–3096. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben Mkaddem S, et al. Shifting FcgammaRIIA-ITAM from activation to inhibitory configuration ameliorates arthritis. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:3945–3959. doi: 10.1172/JCI74572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iborra S, et al. Leishmania uses mincle to target an inhibitory ITAM signaling pathway in dendritic cells that dampens adaptive immunity to infection. Immunity. 2016;45:788–801. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blank U, Launay P, Benhamou M, Monteiro RC. Inhibitory ITAMs as novel regulators of immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;232:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mkaddem SB, et al. IgA, IgA receptors, and their anti-inflammatory properties. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014;382:221–235. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-07911-0_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefanova I, et al. TCR ligand discrimination is enforced by competing ERK positive and SHP-1 negative feedback pathways. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:248–254. doi: 10.1038/ni895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getahun A, Beavers NA, Larson SR, Shlomchik MJ, Cambier JC. Continuous inhibitory signaling by both SHP-1 and SHIP-1 pathways is required to maintain unresponsiveness of anergic B cells. J. Exp. Med. 2016;213:751–769. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abram CL, Roberge GL, Pao LI, Neel BG, Lowell CA. Distinct roles for neutrophils and dendritic cells in inflammation and autoimmunity in motheaten mice. Immunity. 2013;38:489–501. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Croker BA, et al. Inflammation and autoimmunity caused by a SHP1 mutation depend on IL-1, MyD88, and a microbial trigger. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:15028–15033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806619105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pao LI, et al. B cell-specific deletion of protein-tyrosine phosphatase Shp1 promotes B-1a cell development and causes systemic autoimmunity. Immunity. 2007;27:35–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson DJ, et al. Shp1 regulates T cell homeostasis by limiting IL-4 signals. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:1419–1431. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwashima M, Irving BA, van Oers NS, Chan AC, Weiss A. Sequential interactions of the TCR with two distinct cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases. Science. 1994;263:1136–1139. doi: 10.1126/science.7509083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauld SB, Cambier JC. Src-family kinases in B-cell development and signaling. Oncogene. 2004;23:8001–8006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hibbs ML, et al. Multiple defects in the immune system of Lyn-deficient mice, culminating in autoimmune disease. Cell. 1995;83:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90171-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janas ML, Hodgkin P, Hibbs M, Tarlinton D. Genetic evidence for Lyn as a negative regulator of IL-4 signaling. J. Immunol. 1999;163:4192–4198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishizumi H, et al. Impaired proliferation of peripheral B cells and indication of autoimmune disease in lyn-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:549–560. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraus M, et al. Interference with immunoglobulin (Ig)alpha immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) phosphorylation modulates or blocks B cell development, depending on the availability of an Igbeta cytoplasmic tail. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:455–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones ML, Craik JD, Gibbins JM, Poole AW. Regulation of SHP-1 tyrosine phosphatase in human platelets by serine phosphorylation at its C terminus. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:40475–40483. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Kruhlak MJ, Hao JJ, Shaw S. Rapid T cell receptor-mediated SHP-1 S591 phosphorylation regulates SHP-1 cellular localization and phosphatase activity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007;82:742–751. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tan Sardjono C, et al. Development of spontaneous multisystem autoimmune disease and hypersensitivity to antibody-induced inflammation in Fcgamma receptor IIa-transgenic mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3220–3229. doi: 10.1002/art.21344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parravicini V, et al. Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniels AB, et al. Analysis of FcgammaRIIA cytoplasmic tail requirements in signaling for serotonin secretion: evidence for an ITAM-dependent, PI3K-dependent pathway. Scand. J. Immunol. 2010;71:232–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02369.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossato E, et al. Reversal of arthritis by human monomeric IgA through the receptor-mediated SH2 domain-containing phosphatase 1 inhibitory pathway. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1766–1777. doi: 10.1002/art.39142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Neill SK, et al. Monophosphorylation of CD79a and CD79b ITAM motifs initiates a SHIP-1 phosphatase-mediated inhibitory signaling cascade required for B cell anergy. Immunity. 2011;35:746–756. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzer-Attas CJ, et al. Fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages lacking the Src family tyrosine kinases Hck, Fgr, and Lyn. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:669–682. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kovacs M, et al. The Src family kinases Hck, Fgr, and Lyn are critical for the generation of the in vivo inflammatory environment without a direct role in leukocyte recruitment. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:1993–2011. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z, Shen K, Lu W, Cole PA. The role of C-terminal tyrosine phosphorylation in the regulation of SHP-1 explored via expressed protein ligation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:4668–4674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lesourne R, Bruhns P, Fridman WH, Daeron M. Insufficient phosphorylation prevents fc gamma RIIB from recruiting the SH2 domain-containing protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:6327–6336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pfirsch-Maisonnas S, et al. Inhibitory ITAM signaling traps activating receptors with the phosphatase SHP-1 to form polarized “inhibisome” clusters. Sci. Signal. 2011;4:ra24. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaimowitz NS, Falanga YT, Ryan JJ, Conrad DH. Fyn kinase is required for optimal humoral responses. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e60640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rascu A, Repp R, Westerdaal NA, Kalden JR, van de Winkel JG. Clinical relevance of Fc gamma receptor polymorphisms. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1997;815:282–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Pol W, van de Winkel JG. IgG receptor polymorphisms: risk factors for disease. Immunogenetics. 1998;48:222–232. doi: 10.1007/s002510050426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan Sardjono C, Mottram PL, Hogarth PM. The role of FcgammaRIIa as an inflammatory mediator in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 2003;81:374–381. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2003.01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Falanga YT, et al. Lyn but not Fyn kinase controls IgG-mediated systemic anaphylaxis. J. Immunol. 2012;188:4360–4368. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Odom S, et al. Negative regulation of immunoglobulin E-dependent allergic responses by Lyn kinase. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:1491–1502. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishizumi H, Horikawa K, Mlinaric-Rascan I, Yamamoto T. A double-edged kinase Lyn: a positive and negative regulator for antigen receptor-mediated signals. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1343–1348. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stamatiades EG, et al. Immune monitoring of trans-endothelial transport by kidney-resident macrophages. Cell. 2016;166:991–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tan EM, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:1271–1277. doi: 10.1002/art.1780251101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shang L, et al. Selective antibody intervention of Toll-like receptor 4 activation through Fc gamma receptor tethering. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:15309–15318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.537936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McAdoo SP, et al. Correlation of disease activity in proliferative glomerulonephritis with glomerular spleen tyrosine kinase expression. Kidney Int. 2015;88:52–60. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.