Abstract

Phylogeny of Penicillium section Sclerotiora is still limitedly investigated. In this study, five new species of Penicillium are identified from the samples collected from different places of China, and named P. austrosinicum, P. choerospondiatis, P. exsudans, P. sanshaense and P. verrucisporum. The conidiophores of P. austrosinicum and P. exsudans are monoverticillate like most members of the section, while the rest species are biverticillate similar to the only two species P. herquei and P. malachiteum previously reported in the section Sclerotiora. The phylogenetic positions of the new taxa are determined based on the sequence data of ITS, BenA, CaM and RPB2 regions, which reveals that all the species with biverticillate condiophores form a well-supported subclade in the section. The new Penicillium species clearly differ from the existing species of the genus in culture characteristics on four standard growth media, microscopic features, and sequence data. Morphological discrepancies are discussed between the new species and their allies.

Introduction

Penicillium Link is one of the most common fungal genera occurring in diverse environments. They are able to decompose organic matters, and play an important role in biological circulation of biomasses in nature. They also display medicinal and industrial uses. Penicillin, the first antibiotic against gram-positive bacterial infections, has been produced by eight species in section Chrysogena 1, 2. A plethora of mycotoxins, such as citrinin, patulin and nephrotoxic ochratoxin A, are produced by different species3. The enzyme β-glucosidase, essential for biomass-based biofuel industry, is effectively secreted by P. echinulatum and P. oxalicum 4, 5. In food industry, P. nalgiovense and P. salamii are used as starter cultures for sausage fermentation6; P. camemberti for white cheese (Camembert and Brie) and P. roqueforti for blue cheese (roquefort, gorgonzola, stilton, gammelost, etc.)7. Apart from living as saprophytes, more than ten species are endophytes of diverse plants8–10.

Penicillium is lectotypified with one of the three originally species, P. expansum, by Pitt11. The genus is affiliated to the family Aspergillaceae, and contains two subgenera, Aspergilloides and Penicillium. It was further divided into 25 sections based on a four-gene phylogeny12. Recently, two new sections were established, while two other sections were synonymized as one13. In the past decades, significant advances have been achieved for the knowledge of species diversity of this group11, 14–16. More than 1000 Penicillium names were introduced in the past, and 354 species were generally accepted17. Fifty-seven additional species have recently been discovered13, 18–27.

The section Sclerotiora belonging to the subgenus Aspergilloides that contains 17 species was established by Houbraken and Samson12. Among them, P. nodositatum was excluded based on the results of sequence analyses; and P. lilacinoechinulatum, formerly considered as a synonym of P. bilaiae, was revived28. Seven more species were recently added including P. alexiae, P. amaliae, P. arianeae, P. daejeonium, P. maximae, P. restingae and P. vanoranjei 28–30. In China, four taxa (P. adametzii, P. bilaiae, P. herquei and P. sclerotiorum) of the section were recorded in the Flora Fungorum Sinicorum vol. 35 Pennicilium et Teleomorphi Cognati31. In this study, we describe five new species isolated from the soil and rotten fruit samples, which were collected in Guangdong, Hainan and Hunan provinces of China.

Results

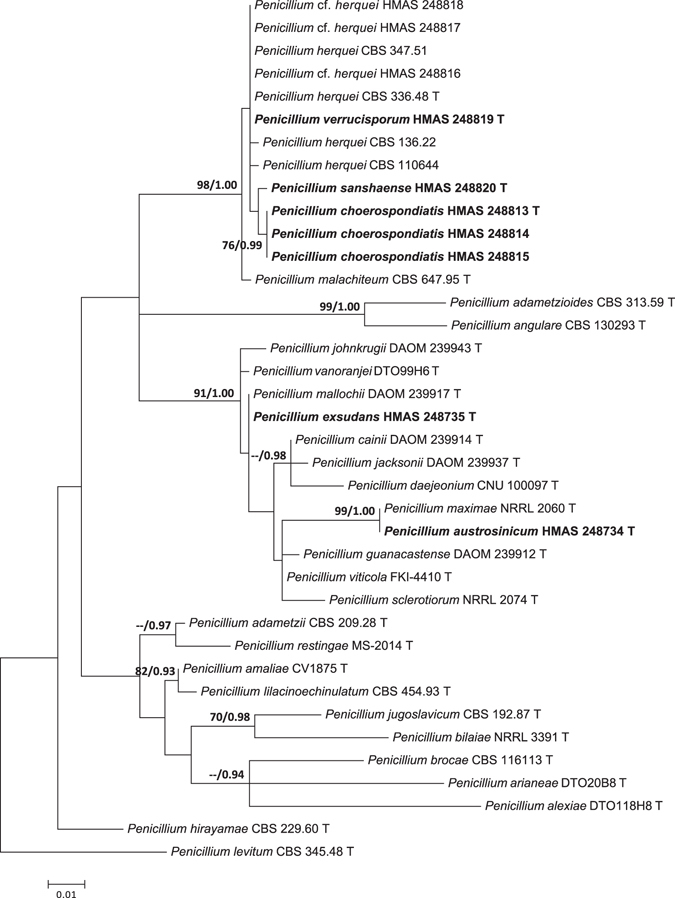

The ITS data set contained 35 sequences of 521 bp. General Time Reversible (GTR) with gamma distribution (+G) was determined as the most suitable model for Maximum Likelihood (ML) analysis, and General Time Reversible with gamma distribution and invariant sites (GTR + I + G) was selected by Akaike Information Criterion as the best fit for Bayesian Inference (BI) analysis. In the ITS tree (Fig. 1), P. choerospondiatis and P. sanshaense were distinguished as sister groups that were associated with P. herquei and P. verrucisporum.

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Penicillium section Sclerotiora inferred from the sequences of the ITS region. Bootstrap values ≥70% (left) and posterior probability values ≥0.90 (right) are indicated at nodes.

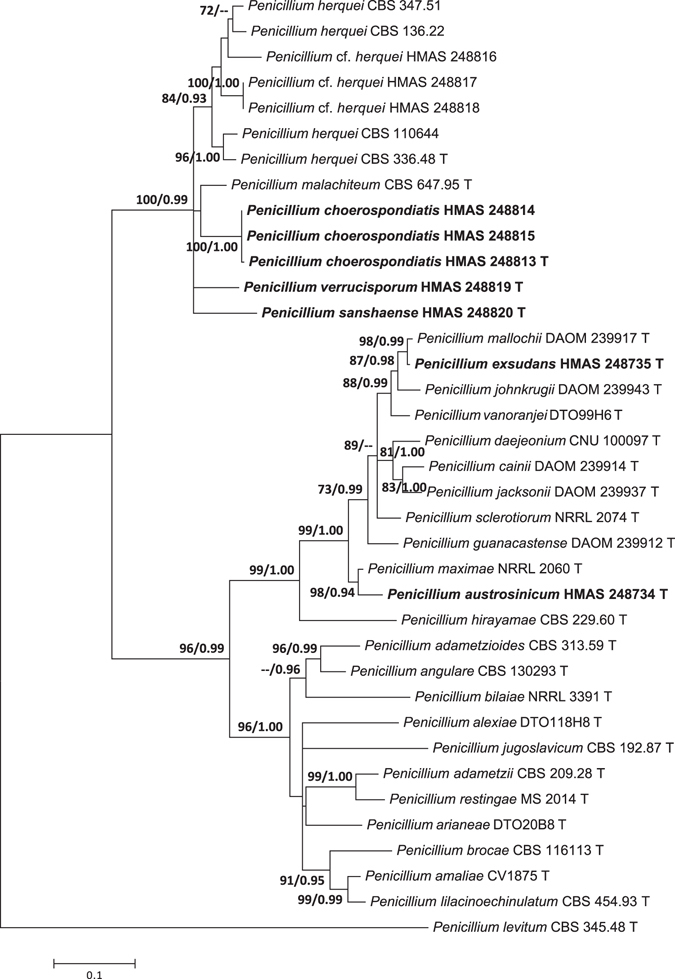

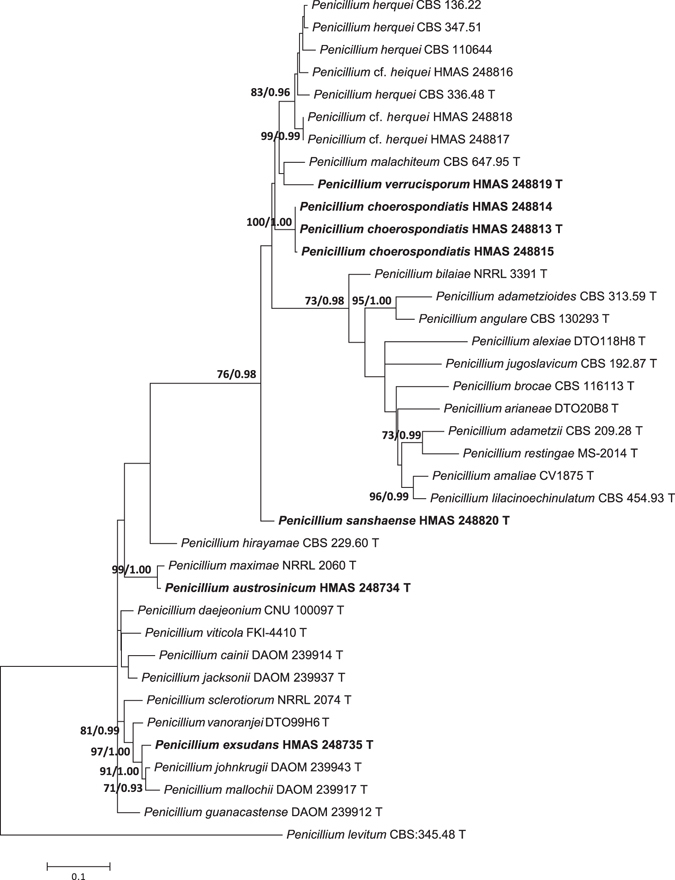

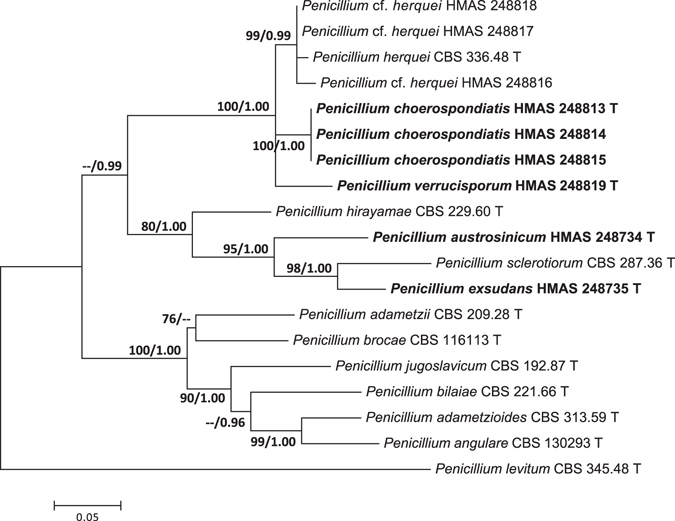

The other three single gene data sets included 35 sequences of 513 bp for BenA gene, 34 sequences of 592 bp for CaM partition, and 19 sequences of 1042 bp for the RPB2. The most suitable models for ML analyses were Kimura 2-parameter (K2) + G (BenA), Tamura-Nei (TN93) + I + G (CaM), and K2 + I + G (RPB2). The most suitable models for Bayesian Inference (BI) analyses were Tamura-Nei (TrN) + G (BenA), TrN + I + G (CaM), and equal-frequency Transition Model (TIMef) + I + G (RPB2). The individual gene analyses of the three genes supported the treatments of P. austrosinicum, P. choerospondiatis, P. exsudans, P. sanshaense and P. verrucisporum as valid new species (Figs 2–4).

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Penicillium section Sclerotiora inferred from the sequences of the CaM region. Bootstrap values ≥70% (left) and posterior probability values ≥0.90 (right) are indicated at nodes.

Figure 2.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Penicillium section Sclerotiora inferred from the sequences of the BenA region. Bootstrap values ≥70% (left) and posterior probability values ≥0.90 (right) are indicated at nodes.

Figure 4.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Penicillium section Sclerotiora inferred from the sequences of the RPB2 region. Bootstrap values ≥70% (left) and posterior probability values ≥0.90 (right) are indicated at nodes.

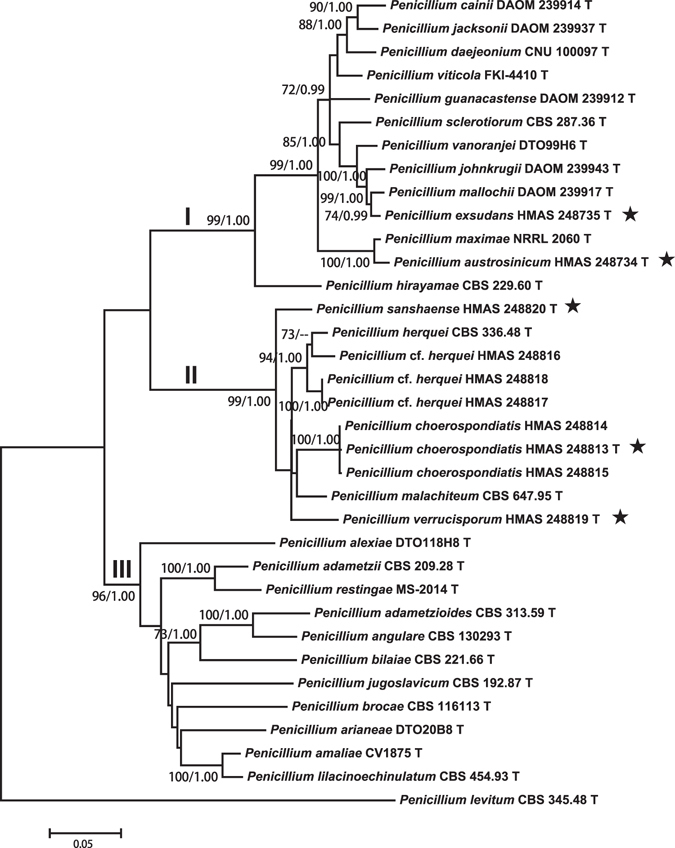

The combined data set consisted of 35 taxa with 2668 bp in length. The GTR + I + G model was determined as the most suitable model for ML and BI analyses. As shown in the four-gene phylogeny of Penicillium section Sclerotiora (Fig. 5), three subclades were recognized. Subclade I contained 13 species (MLBP/BIPP = 99%/1.00) including the newly described P. austrosinicum and P. exsudans. Penicillium austrosinicum was associated with P. maximae (MLBP/BIPP = 100%/1.00), and P. exsudans was a sister of P. mallochii (MLBP/BIPP = 74%/99%). The conidiophores of species in this subclade are all monoverticillate. Subclade II consisted of five species (MLBP/BIPP = 99%/1.00) of which three are newly established. The conidiophores of species in the subclade II are uniformly biverticillate. Subclade III accommodated the rest monoverticillate species in the section (MLBP/BIPP = 96%/1.00).

Figure 5.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of Penicillium section Sclerotiora inferred from the concatenated sequences of ITS, BenA, CaM and RPB2 regions. Bootstrap values ≥70% (left) and posterior probability values ≥0.90 (right) are indicated at nodes.

Taxonomy

Penicillium austrosinicum X.C. Wang & W.Y. Zhuang, sp. nov.

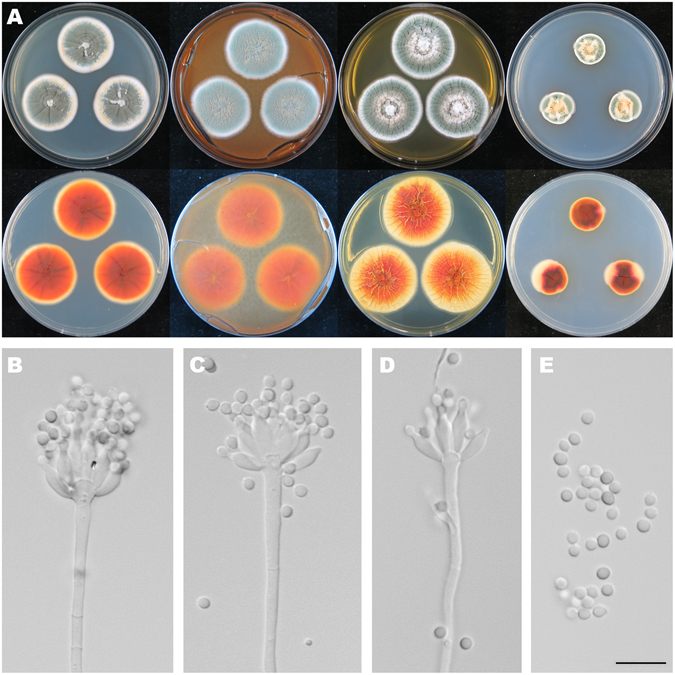

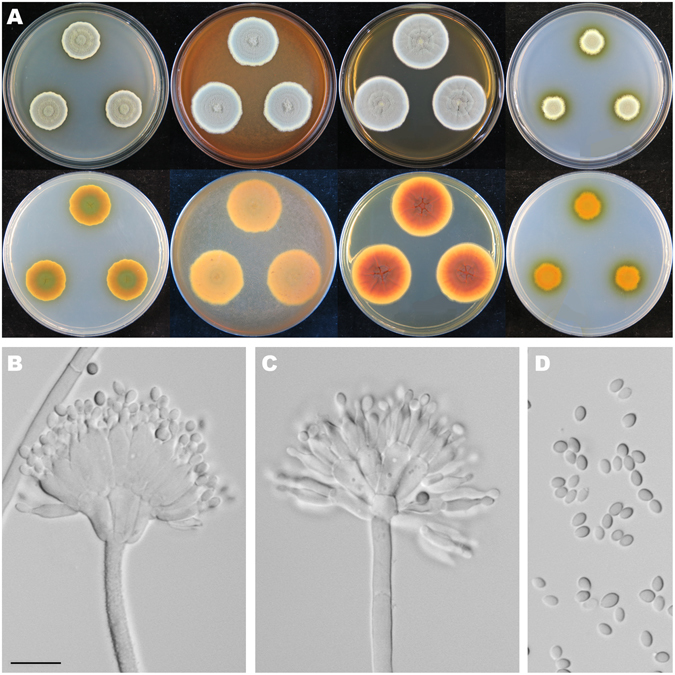

Figure 6

Figure 6.

Colonial and microscopic morphology of Penicillium austrosinicum (HMAS 248734). (A) Colony phenotypes (top row left to right, obverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ); (B–D) Conidiophores; (E) Conidia. Bars: E 10 µm, applies to B–D.

Fungal Names: FN570338

Etymology: The specific epithet refers to the locality of the type strain.

DNA barcodes: ITS KX885061, BenA KX885041, CaM KX885051, RPB2 KX885032.

Colony diam, 7 d, 25 °C (unless stated otherwise): CYA 33–34 mm; CYA 30 °C 32–35 mm; CYA 37 °C no growth; CYA 5 °C no growth; MEA 35–37 mm; YES 37–40 mm; CZ 18–22 mm.

Diagnosis: Penicillium austrosinicum characterized by producing sclerotia on CYA at 25 °C, strictly monoverticillate conidiophores, ampulliform phialides, subglobose and rough-walled conidia.

On CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, plain, conspicuously and radially sulcate, white mycelia appeared in centers, abundant cream to yellow sclerotia produced; margins moderately wide, entire; mycelia white; texture floccose; sporulation dense; conidia en masse dull green; soluble pigments absent; exudates clear and yellowish; reverse conspicuously and radially sulcate, orange in centers but buff at periphery. On MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, plain, radially sulcate in central areas; margins wide, entire; mycelia white and orange; texture floccose; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates tiny and orange; reverse radially sulcate in central areas, orange in centers but yellow at periphery. On YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, protuberant in centers with white mycelia, radially and concentrically sulcate; margins moderately wide, entire; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse light green to green; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse conspicuously and radially sulcate, orange in centers but buff at periphery. On CZ 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular or irregular, protuberant in centers with white and orange mycelia; margins narrow to moderately wide, entire or irregular; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation moderately dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates abundant, clear; reverse reddish brown in centers but orange and buff at periphery. Conidiophores strictly monoverticillate; stipes septate, smooth-walled, 35–175 × 2–3 µm, vesiculate; phialides ampulliform, 8–12, 6–9 × 2.5–3 µm; conidia subglobose, rough-walled, 2.7–3.3 × 2.5–3.3 µm.

Typification: CHINA. Guangdong Province, Shaoguan City, Shixing County, Chebaling National Nature Reserve, Xianrendong Village, 24°44′3″N 114°12′24″E, rotten fruit, 1 November 2015, Zhao-Qing Zeng, Xin-Cun Wang, Kai Chen & Yu-Bo Zhang, 10541 (holotype HMAS 248734, ex-type strain CGMCC 3.18410).

Notes: Fig. 1 shows that P. austrosinicum is the sister of P. maximae (MLBP/BIPP = 100%/1.00) in subclade I. Compared with the new species, P. maximae differs in sparse sporulation on CYA at 25 °C, orange mycelia on MEA at 25 °C, absence of sclerotia, the occasionally seen biverticillate conidiophores, ellipsoidal and smooth conidia, and faster growth rate on YES at 25 °C. The detailed morphological differences between Penicillium austrosinicum and related fungi are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Morphological comparison of the related Penicillium species.

| Conidiophore pattern | No. of metulae per verticil | Metula size (µm) | No. of phialides per metula | Phialide size (µm) | Conidial shape | Conidial walls | Conidial size (µm) | Diam on CYA at 25 °C after 7d (mm) | Diam on MEA at 25 °C after 7d (mm) | Diam on YES at 25 °C after 7d (mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. choerospondiatis | biverticillate | 3–5 | 10.5–15 × 3.5–4.5 | 5–8 | 9–12 × 3.3–4 | ellipsoidal | finely roughened | 4.5–6.5 × 3.3–4.5 | 11–12.5 | 26–29 | 16–19 |

| P. herquei | biverticillate | 4–6 | 10–12 × 3–5 | 6–10 | 7–10 × 2.5–3 | ellipsoidal to apiculate | smooth to roughened | 3.5–5 × 3–3.5 | 20–32 | 30–40 | 30–40 |

| P. malachiteum | biverticillate | 4–8 | 8–12 × 2.5–4 | 4–10 | 8–12 × 2–2.5 | ellipsoidal | smooth to finely roughened | 3–5 × 1.5–3.5 | 20–25 | 28–32 | 28–32 |

| P. sanshaense | biverticillate | 6–8 | 9–12 × 4–6.5 | 6–8 | 9–12 × 3–4 | ellipsoidal | smooth | 3–3.5 × 2–2.5 | 21–23 | 28–30 | 32–34 |

| P. verrucisporum | biverticillate | 5–8 | 9–10.5 × 3.5–5.5 | 5–8 | 7.5–8 × 2.5–3.5 | ellipsoidal | roughened | 3–3.5 × 2.5–3 | 25–27 | 36–37 | 43–44 |

| P. austrosinicum | monoverticilate | 8–12 | 6–9 × 2.5–3 | subglobose | roughened | 2.7–3.3 × 2.5–3.3 | 33–34 | 35–37 | 37–40 | ||

| P. maximae | monoverticilate | 8–16 | 6.5–10 × 2.5–3 | ellipsoidal | smooth | 3–3.5 × 2.5–3 | 34–37 | 34–37 | 40–43 | ||

| P. exsudans | monoverticilate | 6–12 | 7.5–10 × 3.3–4.5 | subglobose to ellipsoidal | finely roughened | 2.7–3.3 × 2.3–3 | 34–36 | 31–33 | 39–42 | ||

| P. johnkrugii | monoverticilate | n.a. | 7–11 × 2–3 | globose to subglobose | finely roughened | 2–3 | 30–38 | 26–36 | 28–38 | ||

| P. mallochii | monoverticilate | n.a. | 7–10 × 2–3 | globose to subglobose | finely roughened | 2.5–3.5 × 2–2.5 | 29–39 | 24–35 | n.a. |

n.a.: data not available.

Penicillium choerospondiatis X.C. Wang & W.Y. Zhuang, sp. nov.

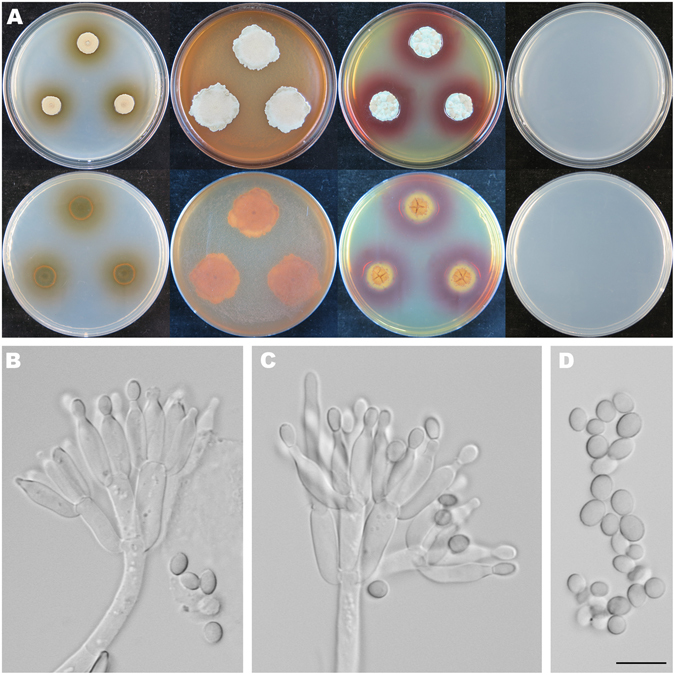

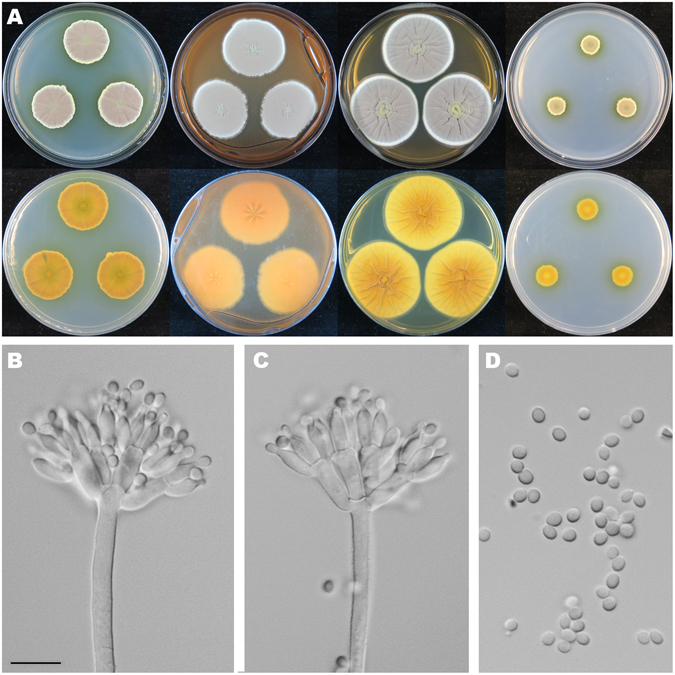

Figure 7

Figure 7.

Colonial and microscopic morphology of Penicillium choerospondiatis (HMAS 248813). (A) Colony phenotypes (top row left to right, obverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ); (B–C) Conidiophores; (D) Conidia. Bars: D 10 µm, applies to B–C.

Fungal Names: FN570333

Etymology: The specific epithet refers to the host plant Choerospondias axillaris.

DNA barcodes: ITS KX885063, BenA KX885043, CaM KX885053, RPB2 KX885034.

Colony diam, 7 d, 25 °C (unless stated otherwise): CYA 11–12.5 mm; CYA 37 °C no growth; CYA 5 °C no growth; MEA 26–29 mm; YES 16–19 mm; CZ nogrowth.

Diagnosis: Penicillium choerospondiatis characterized by crustose colonies on CYA, MEA and YES at 25 °C, no growth on CZ at 25 °C, short and smooth stipes, biverticillate conidiophores, ampulliform phialides, large, ellipsoid and finely roughened conidia, and occurring on fruits of Choerospondias axillaris.

On CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, convex, crustose, conidia dislodged onto the cover when the plates inverted; margins narrow, entire or undulate; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation very dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments light brown; exudates absent; reverse nearly black but yellowish brown at margins. On MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies irregular, plain, crustose, abundant conidia dislodged onto the cover when the plates inverted; margins irregular; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation very dense; conidia en masse dull green; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse light brown to brown. On YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular or irregular, concave in centers, irregularly sulcate, crustose, abundant conidia dislodged onto the cover when the plates inverted; margins irregular; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation very dense; conidia en masse dull green and yellowish brown; soluble pigments abundant, reddish brown; exudates absent; reverse rimose in centers, brown and yellowish brown, but nearly black at periphery. On CZ 25 °C, 7 d: No growth. Conidiophores biverticillate, a minor proportion monoverticillate and terverticillate; stipes septate, smooth-walled, 100–135 × 4–6 µm; metulae cylindrical, 3–5, 10.5–15 × 3.5–4.5 µm; phialides ampulliform, 5–8 per metula, 9–12 × 3.3–4 µm; conidia ellipsoidal, finely rough-walled, 4.5–6.5 × 3.3–4.5 µm.

Typification: CHINA. Hunan Province, Hengyang City, Hengyang County, Goulou town, Goulou Mountain National Forest Park, 27°06′42″N 112°36′28″E, on fruits of Choerospondias axillaris, 24 October 2015, Zhao-Qing Zeng, Xin-Cun Wang, Kai Chen & Yu-Bo Zhang, strain, Xin-Cun Wang, XCW_SN001 (holotype HMAS 248813, ex-type strain CGMCC 3.18411).

Other specimens examined: CHINA. Guangdong Province, Shaoguan City, Shixing County, Chebaling National Nature Reserve, 24°43′41″N 114°15′22″E, on fruits of C. axillaris, 31 October 2015, Zhao-Qing Zeng, Xin-Cun Wang, Kai Chen & Yu-Bo Zhang, strain, Xin-Cun Wang, XCW_SN002 (HMAS 248814); Songshukeng Village, 24°43′13″N 114°16′15″E, on fruits of C. axillaris, 2 November 2015, Zhao-Qing Zeng, Xin-Cun Wang, Kai Chen & Yu-Bo Zhang, strain, Xin-Cun Wang, XCW_SN049 (HMAS 248815).

Notes: Penicillium herquei and P. malachiteum were the only known taxa producing biverticillate conidiophores in section Sclerotiora. When the three new species with the same type of conidiophores are added, they turn out to be all together forming a well-supported subclade (Fig. 1, MLBP/BIPP = 99%/1.00).

As sister of the new species (Fig. 1), P. malachiteum, originally isolated from soil in Japan32, has longer and verrucose stipes (200–320 vs 100–135), more metulae per verticil (4–8 vs 3–5), smaller metulae and conidia, and faster growth rate on CYA and YES at 25 °C28. Penicillium herquei is also similar in colonial morphology, but differs in longer and roughened stipes (200–400 vs 100–135), smaller metulae, phialides and conidia, and growing faster on CYA, MEA and YES at 25 °C11,28. The morphological differences among the related taxa are summarized in Table 1.

Although the three strains of P. choerospondiatis were from different sites, they are morphologically identical. As to their sequence divergences, very few variations were detected. Their ITS and RPB2 regions are basically the same, six bp differences are found in the BenA gene, and three bp divergences exist in the CaM region among collections, which are treated as infraspecific variations.

Penicillium exsudans X.C. Wang & W.Y. Zhuang, sp. nov.

Figure 8

Figure 8.

Colonial and microscopic morphology of Penicillium exsudans (HMAS 248735). (A) Colony phenotypes (top row left to right, obverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ); (B–D) Conidiophores; (E) Conidia. Bars: E 10 µm, applies to B–D.

Fungal Names: FN570336

Etymology: The specific epithet refers to the abundant exudates produced on CYA and CZ at 25 °C.

DNA barcodes: ITS KX885062, BenA KX885042, CaM KX885052, RPB2 KX885033.

Colony diam, 7 d, 25 °C (unless stated otherwise): CYA 34–36 mm; CYA 37 °C no growth; CYA 5 °C no growth; MEA 31–33 mm; YES 39–42 mm; CZ 22–25 mm.

Diagnosis: Penicillium exsudans characterized by strictly monoverticillate conidiophores, ampulliform phialides, subglobose to ellipsoidal and finely roughened conidia.

On CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, plain, conspicuously and radially sulcate in central areas; margins entire; mycelia white; texture floccose; sporulation dense; conidia en masse green to greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates abundant, yellow near centers and clear at periphery; reverse conspicuously and radially sulcate in central areas, orange and bright yellow in centers but white at periphery. On MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, plain, radially sulcate in central areas; margins moderately wide, entire; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse radially sulcate in central areas, brownish red in centers but buff at periphery. On YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, plain, conspicuously and radially sulcate; margins wide, up to 2 mm, entire; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse orange in centers but buff at periphery. On CZ 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular or irregular, protuberant in centers; margins narrow to moderately wide, irregular; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse bluish green to greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates abundant, yellow or clear; reverse orange in centers but yellow to buff at periphery. Conidiophores strictly monoverticillate; stipes septate, smooth-walled, 60–130 × 2.5–4 µm, vesiculate or not; phialides ampulliform, 6–12, 7.5–10 × 3.3–4.5 µm; conidia subglobose to ellipsoidal, finely rough-walled, 2.7–3.3 × 2.3–3 µm.

Typification: CHINA. Guangdong Province, Shaoguan City, Shixing County, Chebaling National Nature Reserve, Xianrendong Village, 24°44′3″N 114°12′24″E, rotten fruit, 1 November 2015, Zhao-Qing Zeng, Xin-Cun Wang, Kai Chen & Yu-Bo Zhang, strain, Xin-Cun Wang, XCW_SN071 (holotype HMAS 248735, ex-type strain CGMCC 3.18412).

Notes: In Fig. 1, P. exsudans clustered with P. mallochii and P. johnkrugii (MLBP/BIPP = 99%/1.00) in subclade I. Compared with the new species, P. mallochii has yellow mycelia and crustose colonies on MEA at 25 °C, and longer stipes (53–380 vs 60–130)33. Penicillium johnkrugii differs in producing sclerotia on CYA, MEA and YES at 25 °C, not producing conidia on CYA at 25 °C, longer stipes (85–230 vs 60–130), and slower growth on YES at 25 °C34.

Penicillium sanshaense X.C. Wang & W.Y. Zhuang, sp. nov.

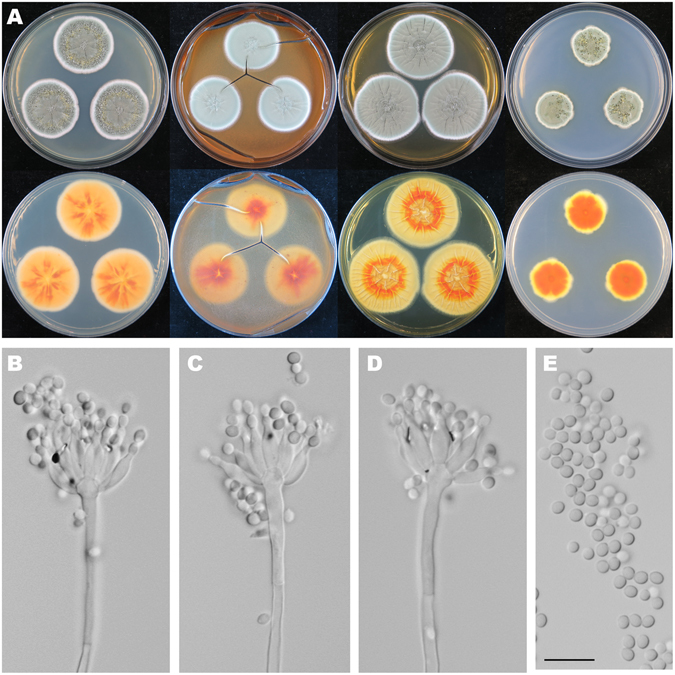

Figure 9

Figure 9.

Colonial and microscopic morphology of Penicillium sanshaense (HMAS 248820). (A) Colony phenotypes (top row left to right, obverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ); (B–C) Conidiophores; (D) Conidia. Bars: B 10 µm, applies to C–D.

Fungal Names: FN570337

Etymology: The specific epithet refers to the locality of the type strain.

DNA barcodes: ITS KX885070, BenA KX885050, CaM KX885060, RPB2 n.a.

Colony diam, 7 d, 25 °C (unless stated otherwise): CYA 21–23 mm; CYA 37 °C no growth; CYA 5 °C no growth; MEA 28–30 mm; YES 32–34 mm; CZ 14–16 mm.

Diagnosis: Penicillium sanshaense characterized by long stipes, biverticillate conidiophores, ampulliform phialides, ellipsoidal and smooth conidia.

On CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, protuberant in centers, concentrically sulcate; margins undulate; mycelia yellow; texture floccose; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments light greenish yellow; exudates clear or absent; reverse rimose and brown in centers but yellow to yellowish brown at periphery. On MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, plain, funiculate at centers, concentrically sulcate; margins undulate, hairy; mycelia yellow; texture floccose; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse orange in central areas but yellowish white at periphery. On YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, concave in centers, concentrically and radially sulcate; margins moderately wide, entire; mycelia yellow; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse radially sulcate, reddish brown in centers but yellow to orange at periphery. On CZ 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular or irregular, convex, greenish yellow at centers; margins hairy; mycelia yellow; texture floccose; sporulation dense; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments light brown; exudates absent; reverse light yellowish brown in centers, brown in central areas, but yellow at periphery. Conidiophores biverticillate, a minor proportion terverticillate; stipes septate, smooth- to rough-walled, 200–500 × 3–4 µm; metulae 6–8, slightly swollen at the apices, 9–12 × 4–6.5 µm; phialides ampulliform, tapering into very thin neck, 6–8 per metula, 9–12 × 3–4 µm; conidia ellipsoidal, smooth-walled, 3–3.5 × 2–2.5 µm.

Typification: CHINA. Hainan Province, Sansha City, Xisha Islands, Yongxing Island, 16°50′41″N 112°20′50″E, soil, 29 March 2015, Ye-Wei Xia, strain, Kai Chen ZC97 (holotype HMAS 248820, ex-type strain CGMCC 3.18413).

Notes: Phylogenetically, P. sanshaense represents an independent lineage in subclade II (Fig. 1). Penicillium cf. herquei (HMAS 248817, HMAS 248818) is similar in smooth conidia, but differs in less metulae per verticil (2–5 vs 6–8), longer metulae obviously swollen at the apices, shorter phialides, and faster growth on CYA, MEA and YES at 25 °C.

Penicillium verrucisporum X.C. Wang & W.Y. Zhuang, sp. nov.

Figure 10

Figure 10.

Colonial and microscopic morphology of Penicillium verrucisporum (HMAS 248819). (A) Colony phenotypes (top row left to right, obverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ; bottom row left to right, reverse CYA, MEA, YES and CZ); (B–C) Conidiophores; (D) Conidia. Bars: B 10 µm, applies to C–D.

Fungal Names: FN570339

Etymology: The specific epithet refers to the warted walls of conidia.

DNA barcodes: ITS KX885069, BenA KX885049, CaM KX885059, RPB2 KX885040.

Colony diam, 7 d, 25 °C (unless stated otherwise): CYA 25–27 mm; CYA 37 °C no growth; CYA 5 °C no growth; MEA 36–37 mm; YES 43–44 mm; CZ 11–12.5 mm.

Diagnosis: Penicillium verrucisporum characterized by comparatively short stipes, biverticillate conidiophores, ampulliform phialides, ellipsoidal and roughened conidia.

On CYA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, plain, conspicuously and radially sulcate; margins narrow, undulate; mycelia yellow; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green to dull purplish brown; soluble pigments greenish yellow; exudates absent; reverse radially sulcate, greenish brown in centers but yellowish brown at periphery. On MEA 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies oblong, plain, funiculate in centers, radially sulcate in central areas or not; margins narrow to moderately wide, entire; mycelia white; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse dull greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse radially sulcate in central areas, yellowish to orangish brown in centers but buff at periphery. On YES 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, radially and concentrically sulcate; margins moderately wide, entire; mycelia yellow; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments absent; exudates absent; reverse radially and concentrically sulcate, orangish brown in centers but buff at periphery. On CZ 25 °C, 7 d: Colonies nearly circular, convex; margins narrow, irregular; mycelia yellow; texture velutinous; sporulation dense; conidia en masse greyish green; soluble pigments greenish yellow; exudates absent; reverse buff in centers but yellowish brown at periphery. Conidiophores biverticillate; stipes septate, finely rough-walled, 125–200 × 3.5–4 µm; metulae 5–8, slightly swollen at the apices or not, 9–10.5 × 3.5–5.5 µm; phialides ampulliform, 5–8 per metula, 7.5–8 × 2.5–3.5 µm; conidia ellipsoidal, rough-walled, 3–3.5 × 2.5–3 µm.

Typification: CHINA. Hunan Province, Chenzhou City, Yizhang county, Mangshan National Nature Reserve, Jiangjunzhai, 24°59′7″N 112°52′24″E, soil, October 27 2015, Kai Chen, MS 18-1 (holotype HMAS 248819, ex-type strain CGMCC 3.18415).

Notes: In the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1), P. verrucisporum appears as an independent terminal branch in subclade II. Among species of the subclade, P. choerospondiatis is similar in comparatively short stipes, but differs in no growth on CZ at 25 °C, less metulae per verticil, larger metulae and phialides, larger and finely roughened conidia, and slower growth on CYA, MEA and YES at 25 °C. The morphological differences among the related taxa are detailed in Table 1.

Discussion

Members of Penicillium section Sclerotiora are characterized by the pigmented mycelia in shades of yellow and/or orange in culture, reverse view of colony yellow, orange or red, and sclerotia and cleistothecia if present bright-colored12. The conidiophores of the species in this section were mostly monoverticillate, and conidiophore branching pattern has not been considered of phylogenetic importance. In this work, we add three new species bearing biverticillate conidiophores to the section. Based on the four-gene phylogeny, three subclades in the section are recognized (Fig. 5). Species with monoverticillate conidiophores are in subclades I and III, while all those possessing biverticillate conidiophores are in subclade II. They join the species P. herquei and P. malachiteum recognized previously with a similar conidiophore branching pattern, which reveals that conidiophore branching pattern is phylogenetically informative. The result highlights that the morphological feature of conidiophore branching pattern is in accordant with the phylogenetic analysis and may be used as a reliable character in taxonomy of the section Sclerotiora.

Most species in Penicillium section Sclerotiora bearing monoverticillate conidiophores have vesiculate conidiophore apices, except for P. adametzii, P. angulare and P. viticola 11, 35. Although these three species do not form vesiculate conidiophores, they are scattered among or intertwined with those producing vesiculate conidiophores in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5). The former two species are located in subclade III and the latter is in subclade I. For the new species in subclade I, the conidiophores of P. austrosinicum and P. exsudans are vesiculate. The feature vesiculate conidiophore might not be phylogenetically informative for the group.

Sclerotia have been produced by seven members of the section Sclerotia 28. The color of sclerotia varies among species. For example, P. austrosinicum gives rise to cream to yellow sclerotia, and P. hirayamae, P. sclerotiorum and P. vanoranjei form orange ones on CYA at 25 °C11,34. In fact, sclerotia appear sporadically in Penicillium species across sections34, such as P. corvianum in section Canescentia producing brown sclerotia26, P. macrosclerotiorum in section Gracilenta giving rise to the white ones36, and P. salamii in section Brevicompacta having orange ones21. The production of sclerotia, as a morphological feature, does not reflect the phylogenetic relationships among species of the genus.

Species in section Sclerotia have been isolated from diverse substrates including soil, plants, and insects28, 33, 37. Apart from the species dominant in soil, the species collected from plant materials comprise a substantial proportion. Three of our five new species are from plant debris: P. choerospondiatis infecting the fruits of Choerospondias axillaris, and P. austrosinicum and P. exsudans from the rotten fruits of unidentified plants. Furthermore, P. herquei is on a leaf of Agauria pyrifolia, P. hirayamae is on cereals11, P. viticola infects grape35, and P. cainii has been isolated from nuts of Juglans nigra and Carya ovata 34. Some species are fungicolous: P. angulare is from a wood-decaying polypore38. Some species are living as plant endophytes8–10. Along with the identifications of new species, a broader range of substrates will be expected. Penicillium herquei can be planted by the nonsocial leaf-rolling weevil Euops chinesis 39–41, which indicates that the fungus evolved the ability to adapt divergent niches.

The genus Penicillium has been established for more than 200 years. New species of this genus have been increasingly found from different regions of the world, especially during the past two decades. The results of this study broaden our knowledge of the species diversity of this group. It is undoubted that more Penicillium species will be found in the unexplored areas of China as well as in other regions of the world based on the integrated or comprehensive studies of morphology, cultural characteristics and sequence data.

Materials and Methods

Fungal materials

Cultures were isolated and purified from the soil and rotten fruit samples collected in Guangdong, Hainan and Hunan provinces of China. Dried cultures have been deposited in the Herbarium Mycologicum Academiae Sinicae (HMAS), and the living ex-type strains are preserved in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC).

Morphological observations

Morphological characterization of each sample was conducted following the standardized methods established by Visagie et al.17. Four standard growth media were used including the Czapek yeast autolysate agar (CYA, yeast extract Oxoid), malt extract agar (MEA, Amresco), yeast extract agar (YES) and Czapek’s agar (CZ). The methods for culture inoculation, incubation, microscopic examinations and digital recordings were described in our previous study42.

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Fungal cultures were grown on the potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium for 7 d and then harvested for DNA extraction using the Plant Genomic DNA Kit (DP305, TIANGEN Biotech, Beijing, China). The fragments of the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS), beta-tubulin (BenA), calmodulin (CaM) and the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2) genes were amplified by PCR using the primers reported by Visagie et al.17. The products were purified and subject to sequencing on an ABI 3730 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Phylogenetic analyses

The sequences obtained in this study have been deposited in GenBank. The accessions and those retrieved from GenBank17 are listed in Table 2. The sequences of each gene (i.e., ITS, BenA, CaM or RPB2) were aligned using the program MAFFT (ver. 7.221)43, and subsequently processed with BioEdit (ver. 7.1.10)44. The individual or concatenated gene data sets were used to generate the respective Maximum-Likelihood (ML) trees using the software MEGA (ver. 6.0.6)45 withthe most suitable nucleotide substitution model and 1,000 replicates of bootstrap tests. Bayesian Inference (BI) analysis was performed with MrBayes (ver. 3.2.5)46 using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm. Appropriate nucleotide substitution models and parameters were determined by using the program Modeltest (ver. 3.7)47. Four MCMC chains (one cold and three heated) were run for one million generations with the trees sampled every 100 generations. The first 25% trees were excluded as the burn-in phase of the analyses, and the posterior probability (PP) values were estimated with the 75% remaining trees. The consensus trees were viewed in FigTree (ver. 1.3.1; http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). The species Penicillium levitum in section Lanata-Divaricata was used as an outgroup.

Table 2.

Fungal species and sequences used in phylogenetic analyses.

| Species | Collection | ITS | BenA | CaM | RPB2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. adametzii | CBS 209.28 T* | JN714929 | JN625957 | KC773796 | JN121455 |

| P. adametzioides | CBS 313.59 T | JN686433 | JN799642 | JN686387 | JN406578 |

| P. alexiae | DTO118H8 T | KC790400 | KC773778 | KC773803 | n.a. |

| P. amaliae | CV 1875 T | JX091443 | JX091563 | JX141557 | n.a. |

| P. angulare | CBS 130293 T | AF125937 | KC773779 | KC773804 | JN406554 |

| P. arianeae | DTO20B8 T | KC773833 | KC773784 | KC773811 | n.a. |

| P. austrosinicum | HMAS 248734 T | KX885061 * | KX885041 | KX885051 | KX885032 |

| P. bilaiae | CBS 221.66 T | JN714937 | JN625966 | JN626009 | JN406610 |

| P. brocae | CBS 116113 T | AF484398 | KC773787 | KC773814 | JN406639 |

| P. cainii | DAOM 239914 T | JN686435 | JN686366 | JN686389 | n.a. |

| P. choerospondiatis | HMAS 248813 T | KX885063 | KX885043 | KX885053 | KX885034 |

| HMAS 248814 | KX885064 | KX885044 | KX885054 | KX885035 | |

| HMAS 248815 | KX885065 | KX885045 | KX885055 | KX885036 | |

| P. daejeonium | CNU 100097 T | JX436489 | JX436493 | JX436491 | n.a. |

| P. exsudans | HMAS 248735 T | KX885062 | KX885042 | KX885052 | KX885033 |

| P. guanacastense | DAOM 239912 T | JN626098 | JN625967 | JN626010 | n.a. |

| P. herquei | CBS 336.48 T | JN626101 | JN625970 | JN626013 | JN121494 |

| CBS 136.22 | JN626100 | JN625969 | JN626012 | n.a. | |

| CBS 347.51 | JN626102 | JN625971 | JN626014 | n.a. | |

| CBS 110644 | JN626103 | JN625972 | JN626015 | n.a. | |

| P. cf. herquei | HMAS 248816 | KX885066 | KX885046 | KX885056 | KX885037 |

| HMAS 248817 | KX885067 | KX885047 | KX885057 | KX885038 | |

| HMAS 248818 | KX885068 | KX885048 | KX885058 | KX885039 | |

| P. hirayamae | CBS 229.60 T | JN626095 | JN625955 | JN626003 | JN121459 |

| P. jacksonii | DAOM 239937 T | JN686437 | JN686368 | JN686391 | n.a. |

| P. johnkrugii | DAOM 239943 T | JN686447 | JN686378 | JN686401 | n.a. |

| P. jugoslavicum | CBS 192.87 T | KC773836 | KC773789 | KC773815 | JN406618 |

| P. lilacinoechinulatum | CBS 454.93 T | AY157489 | KC773790 | KC773816 | n.a. |

| P. malachiteum | CBS 647.95 T | KC773838 | KC773794 | KC773820 | n.a. |

| P. mallochii | DAOM 239917 T | JN626104 | JN625973 | JN626016 | n.a. |

| P. maximae | NRRL 2060 T | EU427298 | KC773795 | KC773821 | n.a. |

| P. restingae | MS-2014 T | KF803355 | KF803349 | KF803352 | n.a. |

| P. sanshaense | HMAS 248820 T | KX885070 | KX885050 | KX885060 | n.a. |

| P. sclerotiorum | CBS 287.36 T | JN626132 | JN626001 | JN626044 | JN406585 |

| P. vanoranjei | DTO99H6 T | KC695696 | KC695686 | KC695691 | n.a. |

| P. verrucisporum | HMAS 248819 T | KX885069 | KX885049 | KX885059 | KX885040 |

| P. viticola | FKI-4410 T | AB606414 | AB540174 | n.a. | n.a. |

| P. levitum | CBS 345.48 T | GU981607 | GU981654 | KF296394 | KF296432 |

T: ex-type strains.

n.a.: data not available.

*The accessions in bold are newly obtained in this study.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable suggestions and linguistic corrections. We also thank Prof. Tai-Hui Li (Guangdong Institute of Microbiology) for providing the soil samples from the Xisha Islands, and Prof. Jian-Yun Zhuang (Institute of Microbiology, CAS) for constructive discussions. This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 31570018, 31270073) to WYZ.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: W.Y.Z. Performed the experiments: X.C.W. Analyzed the data: X.C.W. and W.Y.Z. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: K.C. and Z.Q.Z. Wrote the paper: X.C.W. and W.Y.Z.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Houbraken J, Frisvad JC, Samson RA. Fleming’s penicillin producing strain is not Penicillium chrysogenum but P. rubens. IMA Fungus. 2011;2:87–95. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2011.02.01.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houbraken J, et al. New penicillin-producing Penicillium species and an overview of section Chrysogena. Persoonia. 2012;29:78–100. doi: 10.3767/003158512X660571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frisvad JC, Smedsgaard J, Larsen TO, Samson RA. Mycotoxins, drugs and other extrolites produced by species in Penicillium subgenus. Penicillium. Stud. Mycol. 2004;49:201–241. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider WD, et al. Penicillium echinulatum secretome analysis reveals the fungi potential for degradation of lignocellulosic biomass. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2016;9 doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0476-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao G, et al. Production of a high-efficiency cellulase complex via beta-glucosidase engineering in Penicillium oxalicum. Biotechnol. Biofuels. 2016;9 doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0491-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magista D, et al. Penicillium salamii strain ITEM 15302: A new promising fungal starter for salami production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016;231:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalai, S., Anzala, L., Bensoussan, M. & Dantigny, P. Modelling the effect of temperature, pH, water activity, and organic acids on the germination time of Penicillium camemberti and Penicillium roqueforti conidia. Int. J. Food Microbiol. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.03.024 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Vega FE, Posada F, Peterson SW, Gianfagna TJ, Chaves F. Penicillium species endophytic in coffee plants and ochratoxin A production. Mycologia. 2006;98:31–42. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2006.11832710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim CS, Park MS, Yu SH. Two species of endophytic Penicillium from Pinus rigida in Korea. Mycobiology. 2008;36:222–227. doi: 10.4489/MYCO.2008.36.4.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.You YH, Park JM, Park JH, Kim JG. Diversity of endophytic fungi associated with the roots of four aquatic plants inhabiting two wetlands in Korea. Mycobiology. 2015;43:231–238. doi: 10.5941/MYCO.2015.43.3.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitt, J. I. The genus Penicillium and its teleomorphic states Eupenicillium and Talaromyces (Academic Press, 1979).

- 12.Houbraken J, Samson RA. Phylogeny of Penicillium and the segregation of Trichocomaceae into three families. Stud. Mycol. 2011;70:1–51. doi: 10.3114/sim.2011.70.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houbraken J, Wang L, Lee HB, Frisvad JC. New sections in Penicillium containing novel species producing patulin, pyripyropens or other bioactive compounds. Persoonia. 2016;36:299–314. doi: 10.3767/003158516X692040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thom, C. The Penicillia (Williams & Wilkins, 1930).

- 15.Raper, K. B. & Thom, C. A manual of the Penicillia (Williams & Wilkins, 1949).

- 16.Stolk AC, Samson RA. The Ascomycete genus Eupenicillium and related Penicillium anamorphs. Stud. Mycol. 1983;23:1–149. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visagie CM, et al. Identification and nomenclature of the genus. Penicillium. Stud. Mycol. 2014;78:343–371. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crous PW, et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 281–319. Persoonia. 2014;33:212–289. doi: 10.3767/003158514X685680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.You YH, et al. Penicillium koreense sp. nov., isolated from various soils in Korea. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;24:1606–1608. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1406.06074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park MS, et al. Penicillium jejuense sp. nov., isolated from the marine environments of Jeju Island, Korea. Mycologia. 2015;107:209–216. doi: 10.3852/14-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perrone G, et al. Penicillium salamii, a new species occurring during seasoning of dry-cured meat. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015;193:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taniwaki MH, et al. Penicillium excelsum sp. nov from the Brazil Nut Tree Ecosystem in the Amazon Basin’. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Visagie CM, Houbraken J, Seifert KA, Samson RA, Jacobs K. Four new Penicillium species isolated from the fynbos biome in South Africa, including a multigene phylogeny of section Lanata-Divaricata. Mycol. Prog. 2015;14 doi: 10.1007/s11557-015-1118-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rong CB, et al. Penicillium chroogomphum, a new species in Penicillium section Ramosa isolated from fruiting bodies of Chroogomphus rutilus in China. Mycoscience. 2016;57:79–84. doi: 10.1016/j.myc.2015.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Visagie CM, et al. A taxonomic review of Penicillium species producing conidiophores with solitary phialides, classified in section Torulomyces. Persoonia. 2016;36:134–155. doi: 10.3767/003158516X690952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Visagie CM, et al. Fifteen new species of Penicillium. Persoonia. 2016;36:247–280. doi: 10.3767/003158516X691627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visagie CM, Seifert KA, Houbraken J, Samson RA, Jacobs K. A phylogenetic revision of Penicillium sect. Exilicaulis, including nine new species from fynbos in South Africa. IMA Fungus. 2016;7:75–117. doi: 10.5598/imafungus.2016.07.01.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visagie CM, et al. Five new Penicillium species in section Sclerotiora: a tribute to the Dutch Royal family. Persoonia. 2013;31:42–62. doi: 10.3767/003158513X667410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sang H, et al. Penicillium daejeonium sp. nov., a new species isolated from a grape and schisandra fruit in Korea. J. Microbiol. 2013;51:536–539. doi: 10.1007/s12275-013-3291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crous PW, et al. Fungal Planet description sheets: 214–280. Persoonia. 2014;32:184–306. doi: 10.3767/003158514X682395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kong, H. Z. Flora Fungorum Sinicorum. vol. 35. Penicillium et teleomorphi cognati (Science Press, 2007).

- 32.Yaguchi T, Miyadoh S, Udagawa S. Chromocleista, a new cleistothecial genus with a Geosmithia anamorph. Trans. Mycol. Soc. Japan. 1993;34:101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rivera KG, et al. Penicillium mallochii and P. guanacastense, two new species isolated from Costa Rican caterpillars. Mycotaxon. 2012;119:315–328. doi: 10.5248/119.315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivera KG, Seifert KA. A taxonomic and phylogenetic revision of the Penicillium sclerotiorum complex. Stud. Mycol. 2011;70:139–158. doi: 10.3114/sim.2011.70.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nonaka K, et al. Penicillium viticola, a new species isolated from a grape in Japan. Mycoscience. 2011;52:338–343. doi: 10.1007/S10267-011-0114-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Zhang XM, Zhuang WY. Penicillium macrosclerotiorum, a new species producing large sclerotia discovered in south China. Mycol. Res. 2007;111:1242–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson SW, Perez J, Vega FE, Infante F. Penicillium brocae, a new species associated with the coffee berry borer in Chiapas, Mexico. Mycologia. 2003;95:141–147. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2004.11833143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peterson SW, Bayer EM, Wicklow DT. Penicillium thiersii, Penicillium angulare and Penicillium decaturense, new species isolated from wood-decay fungi in North America and their phylogenetic placement from multilocus DNA sequence analysis. Mycologia. 2004;96:1280–1293. doi: 10.1080/15572536.2005.11832878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li X, Guo W, Ding J. Mycangial fungus benefits the development of a leaf-rolling weevil. Euops chinesis. J. Insect Physiol. 2012;58:867–873. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, et al. Farming of a defensive fungal mutualist by an attelabid weevil. ISME J. 2015;9:1793–1801. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X, Guo W, Wen Y, Solanki MK, Ding J. Transmission of symbiotic fungus with a nonsocial leaf-rolling weevil. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2016;19:619–624. doi: 10.1016/j.aspen.2016.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang XC, Chen K, Qin WT, Zhuang WY. Talaromyces heiheensis and T. mangshanicus, two new species from China. Mycol. Prog. 2017;16:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s11557-016-1251-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl. Acids. Symp. Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ronquist F, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Posada D, Crandall KA. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:817–818. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]