Abstract

Despite predictions of the classic, hybrid-sterility model of chromosomal speciation, some organisms demonstrate high rate of karyotype evolution. This rate is especially impressive in Agrodiaetus butterflies that rapidly evolved the greatest chromosome number diversity known in animal kingdom within a single subgenus. Here we analyzed karyotype evolution in Agrodiaetus using phylogenetic comparative methods. We found that chromosome numbers possess a strong phylogenetic signal. This disproves the chromosome megaevolution model that proposes multiple chromosome rearrangements to accumulate independently in each of closely related species. We found that Brownian motion gives a more adequate description of observed trait changes than Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model. This indicates that chromosome numbers evolve via random walk along branches of the phylogeny. We discovered a correlation between karyotype changes and phylogeny branch lengths. This gradual pattern is inconsistent with the hybrid-sterility model which, due to association of major chromosome changes with cladogenetic events, predicts a high degree of punctualism in karyotype evolution. Thus, low underdominace of chromosomal rearrangements and/or prevalence of the recombination-suppression model over the hybrid-sterility model of chromosome speciation are the most common engines of the runaway chromosome number change observed.

Introduction

Chromosomal rearrangements (CRs) play significant role in both life functioning and evolution. They are subject of studies of physiologists, geneticists and medical researchers because multiple syndromes and heritable diseases are associated with CRs1. CRs also attract the attention of evolutionary biologists since they trigger speciation via reducing fertility of chromosomal heterozygotes (if CRs are underdominant) or/and via suppressed recombination (if CRs are neutral and do not influence fertility of chromosomal heterozygotes)2. CRs maintain postzygotic isolation between well-established species and protect hybridizing lineages from merging3. While protecting the blocks of linked genes from recombination, CRs are crucial in adaptive evolution4–6. Chromosome fusions and fissions change the number of chromosomes altering the number of linkage groups7–9. Finally, being a part of genome architecture, chromosome rearrangements are considered to be a selectable trait per se 10, 11.

Cytological events and intracellular processes involved in chromosome evolution are relatively well-studied12–15, however, much less is known about evolutionary mechanisms determining probability and rate of CRs fixation in populations. Chromosome diversity in different groups of organisms show that many lineages are characterized by karyotypic constancy among species, in particular by absence or low level of interspecific variability of chromosome numbers3, 8. This stability is in good compliance with the fact that new chromosomal rearrangements are usually associated with heterozygote disadvantage. Therefore, their distribution and probability of fixation within a large population is low16–18. For example, genomes of Lepidoptera, the order which includes butterflies and moths provide an excellent example of the chromosome number stability: haploid number (n) of chromosomes n = 31 is mostly invariable and characterizes the vast majority of species, genera and families19–22.

In contrast to this apparent uniformity, multiple examples of chromosome number diversity within small groups of animals and plants are known. Most extreme cases of rapid chromosome evolution are found in insects, for example, in the genus Apiomorpha (Hemiptera: Eriococcidae) interspecific karyotypic diversity of haploid chromosome numbers from n = 2 to n = 96 was discovered23. Among Lepidoptera particularly striking are Godyris (family Nymphalidae, n = 13–120)24, Leptidea (Pieridae, n = 28–103)7, 8, 19, 25, 26, Lysandra (Lycaenidae, n = 24–93)27, and Polyommatus (Lycaenidae). In Polyommatus extreme variety of chromosomal numbers is concentrated within the monophyletic group of closely related Agrodiaetus species3. This West Palearctic subgenus numbers nearly 120 species, had branched roughly three million years ago and has been evolving with considerably high diversification rate3, 28. Agrodiaetus has a larger karyotype diversity than any other animal group with a total range of haploid chromosome numbers from n = 10 to n = 13429–34.

In vertebrates, the range of chromosome number variation between closely related species is smaller, yet still impressive: in Corydoras fish genus (Siluriformes: Callichthyidae)35 haploid numbers are ranging from n = 22 to n = 51. South American rodents of the genus Ctenomys (Rodentia: Ctenomiydae) have haploid chromosome numbers varying from n = 5 to n = 35 among the 60 species described36, 37. Muntjac deers (Artiodactyla: Cervidae) have karyotypes, ranging from n = 3 to n = 2338. In plants, the greatest range of within-genus karyotype variation not related to polyploidy is found in Carex, where haploid chromosome number ranges from n = 6 to n = 6610, 39.

The tempo and dynamics of such runaway chromosome number evolution are still poorly studied (for some examples see refs 3, 8, 10, 21, 39–42). Here we analyze this evolutionary phenomenon by using the butterfly subgenus Agrodiaetus as a model system and applying comparative phylogenetic methods in order to track ways of chromosomal changes during natural history of taxa10, 27, 39, 42. We were interested in the three following questions.

Do chromosome numbers possess a phylogenetic signal? In other words, do multiple chromosome fissions and fusions accumulate independently in each of closely related species of Agrodiaetus? Or, on the contrary, does this accumulation occur in rows of multiple speciation events? Phylogenetic signal has been found earlier in Agrodiaetus karyotype evolution by Kandul with coauthors3 via Abouheif’s test for serial independence. Our analysis here aims to extend their results since they did not test intensity of phylogenetic signal, neither incorporated phylogenetic uncertainty into analysis nor produced any qualitative assessment of their results.

Can the transformation of chromosome numbers be described by a more “neutral” model, such as Brownian motion3, or karyotypes evolve towards an adaptive optimum?

What is the temporal pattern of chromosome number change within a lifespan of species? More specifically, (3a) is there association of CR fixations with speciation events? Such association is predicted by the classic chromosome-sterility theories of chromosome speciation and stems from the idea of fixation of a single underdominant CR17, 43.

If CR fixation correlates with speciation, we would expect a strong punctualism in chromosome evolution with the majority of CRs associated with cladogenetic events at the very initial stages of species diversification. Alternatively, (3b) CRs changing the chromosome number do not seriously impact fertility, can accumulate gradually and are not necessarily associated with early stages of speciation.

Results

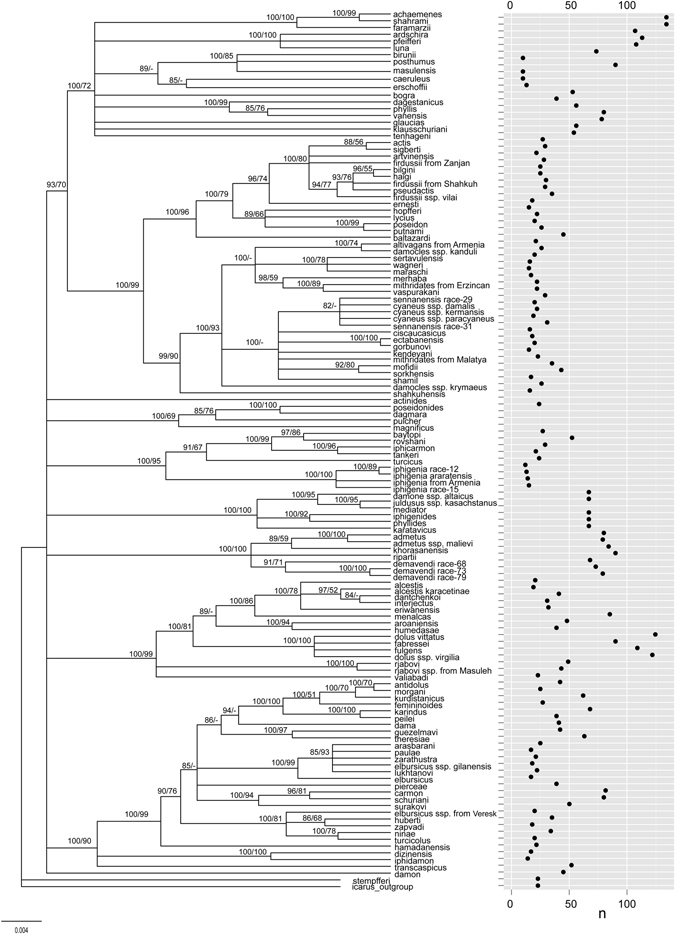

Phylogeny reconstruction

Phylogenetic trees using Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI) methods were obtained for 130 populations corresponding to 111 species comprising all the sequence data available to date for 120 described Agrodiaetus species (see Supplementary Table S1 for the sequence IDs). BI was performed with the following models: GTR + I + Г for mitochondrial markers COI and COII and HKY85 for leu-tRNA; GTR for nuclear 5.8S rDNA + ITS2 + 28S rDNA. ML analysis was performed with GTR model for the entire dataset (ML of the most plausible tree was −ln = 19652.9). BI consensus tree topology was mostly the same as ML tree topology. Figure 1 shows the calculated BI consensus tree. Most nodes were strongly supported; more than half of all nodes had Bayesian posterior probabilities of 0.90 and higher.

Figure 1.

Bayesian majority rule consensus phylogram of seven nuclear and mitochondrial DNA markers for Agrodiaetus species. Numbers above the branches indicate Bayesian posterior probabilities and bootstrap support values for maximum likelihood tree (ML), in that order, expressed as percentages, dashes indicate support values below 50%. Dots on the plot represent haploid chromosome numbers (n).

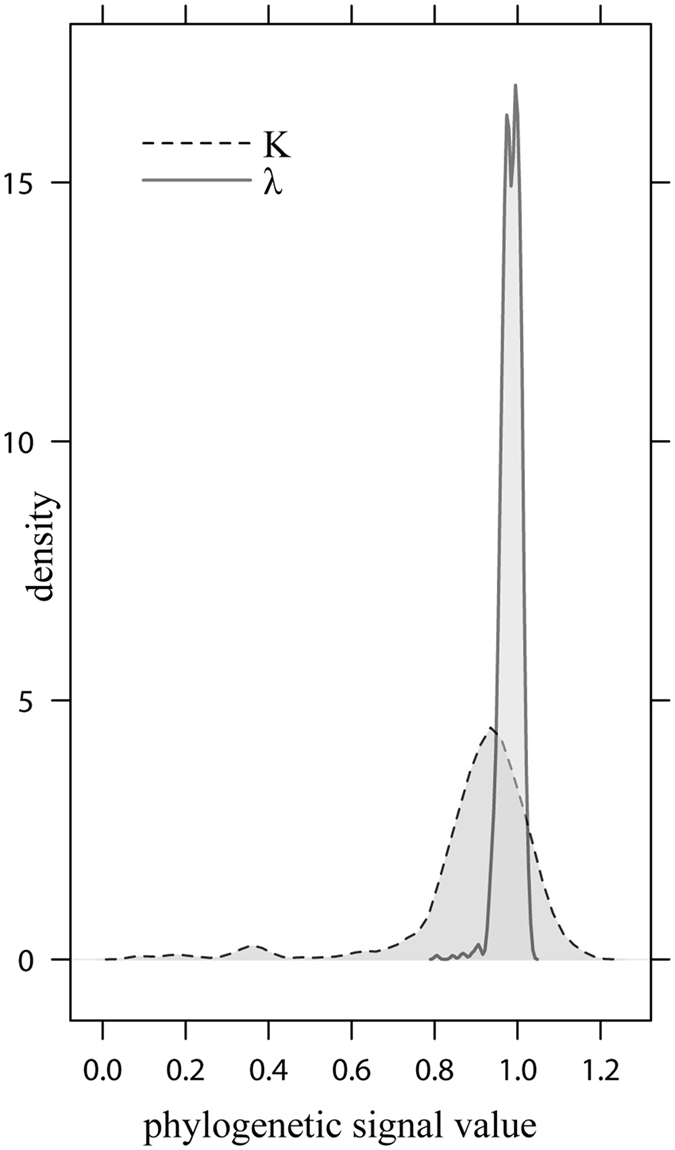

Phylogenetic signal

We calculated the phylogenetic signal using Pagel’s lambda and Blomberg’s K metrics44, 45. As shown in the Fig. 2, K and lambda vary in relation to tree topology (including different branch lengths), but for most phylograms both K and lambda approach the value indicating strong phylogenetic signal (K = 1, λ = 1). Pagel’s lambda has varied from λ = 0.81 to λ = 1.03 and Blomberg’s K from 0.06 to 1.4 (with K = 0.9 and K = 1 for the most tree topologies). Obtained K and lambda values were significantly different than expected by chance (p < 0.001). Lambda values were tested using likelihood ratio tests where topologies with λ = 0 and λ = 1 were compared against each other and against maximum likelihood lambda values accordingly. Maximum likelihood values of lambda were significantly greater than 0, however maximum likelihood λ value was not distinguished from the modelled λ = 1 (p < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Density distribution of phylogenetic signal for Pagel’s lambda and Blomberg’s K metrics across 1000 Bayesian post burn-in phylograms for subgenus Agrodiaetus.

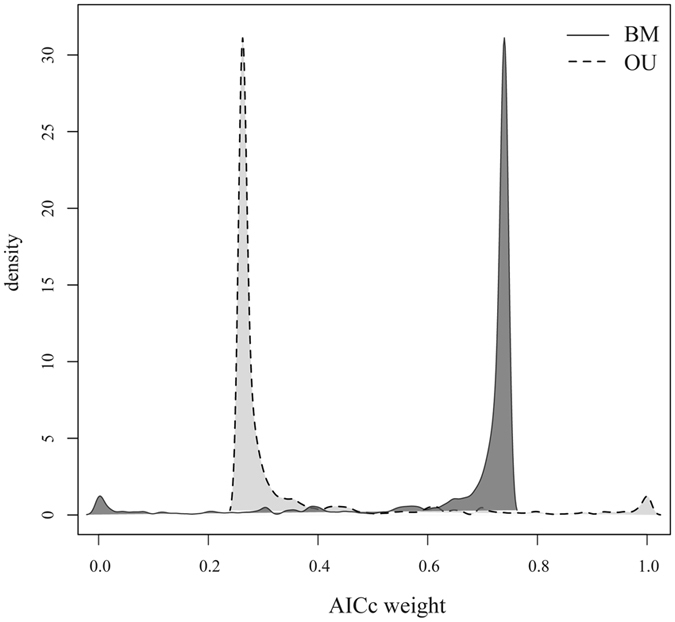

Brownian motion versus Ornstein-Uhlenbeck model

The Brownian motion (BM) as a constant variance process is often employed to model and characterize the continuous quantitative trait evolution, which is controlled by influence of stochastic factors46–50. Alternatively Ornstein-Uhlenbeck process (OU) is the commonly used to model selective pressure towards a particular range of phenotypes indicating an adaptive optimum50, 51. BM and OU processes were compared via corrected Akaike information criteria (AICc)52. Akaike weights demonstrated the higher likelihood rate for BM model (Fig. 3). Thus, we conclude that BM model gives a more adequate description of observed trait changes than the OU model.

Figure 3.

Density distribution of Brownian motion (BM) and Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) models support over 1000 Bayesian post burn-in phylograms for Agrodiaetus species. AICc is Akaike information criterion with a correction for finite sample sizes. AICc weights are the relative likelihood of each model: the weight is smaller if the model is less plausible.

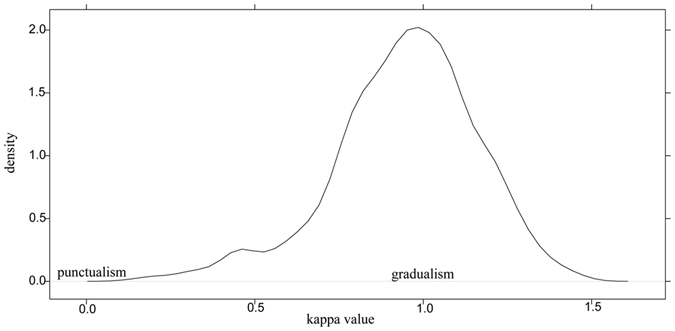

Gradual versus punctual mode of chromosome evolution

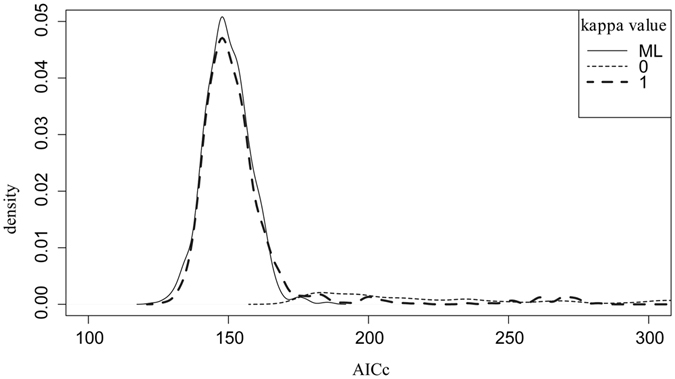

To test for a punctuational versus gradual mode of trait evolution we used κ (kappa) parameter53. Testing kappa values using AICc demonstrated that likelihood of κ = 1 and AICc of maximum likelihood kappa coincided almost entirely, whereas AICc of other models (κ = 0 and κ = 3) were higher (AICc of κ = 3 model is approximately 20 times as high as κ = 1 AICc), suggesting that κ = 1 most likely reflects mode of karyotype evolution indicating clear gradualism in CRs (Figs 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Density distribution of maximum likelihood tree-scaling parameter kappa values across 1000 Bayesian post burn-in phylograms for Agrodiaetus species.

Figure 5.

Density distribution of Pagel’s kappa model support over 1000 Bayesian post burn-in phylograms for Agrodiaetus species. AICc is Akaike information criterion riteria with a correction for finite sample sizes, the smaller the AICc means the more plausible the model.

Discussion

The observed diversity of chromosome numbers in Agrodiaetus could theoretically be a result of multiple CRs emerged from an ancestral karyotype and independently accumulated in each of the studied species. This pattern of chromosome change has been described by Baker and Bickham54–56 under the name “karyotype megaevolution”. This model describes a fast accumulation of multiple CRs occurring independently in each species which results in a lack of phylogenetic signal. Visual inspection of the Polyommatus (Agrodiaetus) chromosome numbers mapped on the consensus Bayesian phylogeny (Fig. 1) shows that some sister species have extremely different chromosome numbers (e.g. n = 10 in P. masulensis and n = 85 in P. posthumus). These drastically different karyotypes are not a result of polyploidy but a consequence of independent chromosome fissions and fusions29. Such a case may seem, at the first glance, to correspond with the karyotype megaevolution model.

An alternative to the chromosomal megaevolution is the model of stepwise accumulation of similar CRs in consequent rows of speciation events resulting in strong phylogenetic signal8. As our estimates show, this is certainly the case for the chromosome number evolution in Agrodiaetus. The studied karyotypes are phylogenetically nonindependent: CRs such as fusions and fissions are likely to pile up in Agrodiaetus during a succession of multiple speciation events and incrementally result in low and high chromosome numbers. Consequently, closely related taxa tend to have similar chromosome sets. Furthermore, strong phylogenetic signal also suggests that recently diverged species are more karyotypically akin than deeply diverged ones: the expected difference in chromosome sets between the descendants grows proportional to the time since they shared a common ancestor.

The strong phylogenetic signal does not describe a particular process or rate of evolution57, 58. Previously BM model has been hypothesized to characterize rapid karyotype transformations in Agrodiaetus 3. The model implies gradual changes through time to occur aside from the current character state and expected mean of the changes50, 59. Our current study confirms that in Agrodiaetus dynamics of chromosome evolution follows Brownian motion and can be described as neutral drift (or “random walk”) with changes around a mean of zero.

Since karyotypes may fall into the selective optimum or equilibrium, we checked also the presence of adaptive peak in chromosome numbers by testing OU model against BM. The idea of the adaptive shift in chromosomal numbers reflects certain conceptions. First of all, quantum and stasipatric chromosomal speciation models imply adaptive chromosome re-patterning via spontaneous gene and linkage group rearrangements17, 60. Second, spatial constraints can also occur because chromosome size and shape are important in the segregation of chromosomes during the cell division29. There also may be special cases of adaptivity in chromosome organization, such as eu- and heterochromatin adaptation to nocturnal and diurnal vision in mammals61.

On a range of different tree topologies modelling results conclusively demonstrate that BM, but not OU fits the data (Fig. 3). Therefore, it is likely that every next step in chromosome evolution along a phylogenetic lineage is independent of previous ones with variance accumulating over time. Thereby CRs and karyotypes depend on phylogenesis but probably not on any adaptive regime or evolutionary constraint.

If underdominant CRs directly initiate speciation via formation of post-zygotic reproductive isolation, as suggested in classic theories of chromosomal evolution17, 43, their fixation should be associated with the points of cladogenesis resulting in strong punctual mode of karyotype evolution. If CRs are not underdominant (or at least not strongly underdominant), their fixation and accumulation is expected to be gradual without any association between CRs and with cladogenesis. Graduality is consistent with at least three different scenarios. First, CRs might be irrelevant for reproductive isolation17. Second, according to the recombination-suppression model2, CRs might promote parapatric speciation working as a genetic filter between populations60, 62–64. Recombination-suppression model implies that mutations associated with the rearranged parts of the genomes are protected from intrapopulation gene flow. This results in accumulation of genetic incompatibilities leading to reproductive isolation and eventual speciation. Third, cascade43 and monobrachial65 models postulate the sequential accumulation of several neutral or nearly neutral CRs in independent populations resulting in interpopulation post-zygotic isolation.

In this study, we discovered a correlation between number of CRs and branch length, and this pattern is in a good agreement with gradual accumulation of CRs in Agrodiaetus. AICc conclusively demonstrate that κ = 1 model fits the data better κ = 0 or κ = 3 (Fig. 5). Thus, our data are hardly compatible with the classic chromosomal hybrid sterility model being the main engine of chromosome number diversity in Agrodiaetus. However, the results are well consistent with the mentioned above scenarios of karyotype evolution in which chromosome changes indirectly or weakly affect fertility of heterozygotes for CRs.

In Lepidoptera, there are other empirical data suggesting that chromosome fusions and fissions are not strongly underdominant and can accumulate gradually. There is an experimental evidence that Antherea moths heterozygous for multiple CRs are not sterile66. In Leptidea sinapis butterflies (Lepidoptera, Pieridae) the diploid chromosome number gradually decreases from 2n = 106 in Spain to 2n = 56 in eastern Kazakhstan, resulting in a 6000 km-wide cline where within-species accumulation of chromosomal changes is shown7, 8, 67. Homoploid hybrid speciation in Agrodiaetus via hybridization between chromosomal races with n = 27 and n = 68 and consequent chromosome sorting33 assumes that F1 hybrids heterozygous for 41 fusions/fissions were fertile. Thus, it seems unlikely that CRs are strongly underdominant in these groups. Interestingly, low underdominance of chromosomal fusions and fissions is not restricted to Lepidoptera. For example, it is also known in mammals68–70.

Finally, we should note that Lepidoptera, including Agrodiaetus butterflies, have holocentric chromosomes lacking localized centromeres and distinct chromosome arms71–73. Due to this special organisation fissions and fusions do not dramatically alter meiotic segregation as in the case of monocentric chromosomes which may became acentric after fission or dicentric after fusion. Higher viability of chromosomes after fragmentations and fusions and other phenomena related to holocentric structure such as holokinetic drive74 also could contribute to the origin of chromosomal diversity. Nevertheless, we believe that low underdominace of chromosomal rearrangements and prevalence of recombination-suppression over hybrid-sterility model are most common engines of runaway evolution of chromosome numbers in Lepidoptera.

Methods

Phylogeny reconstruction

Sequences (5.8S rDNA partial gene, ITS2 complete and 28S rDNA partial, COI, leu-tRNA complete and COII – partial) were collected from GenBank. Sequences of each gene were aligned separately by clustalW, the alignments were corrected manually using BioEdit75. Since ITS2 sequence has multiple indels which are highly specific on the species-level, it provides additional information for phylogenetic analysis76, 77, so we treated all ITS2 indels as binary characters (insertion - 1, deletion - 0). The final concatenated alignment had length of 2948 nucleotides (COI 1–1539 bp, leu-tRNA 1540–1604 bp, COII 1605–2281 bp, 5.8 S rDNA + ITS2 + 28 S rDNA 2282–2948 bp) and 23 binary characters. Additional 643 bp fragment of COI and 592 bp fragment of ITS2 for P. kendevani (ITS2), P. luna (ITS2), and P. shahukuhensis (ITS2) were kindly provided by Nazar Shapoval, Zoological Institute, RAS.

As an outgroup, we used P. icarus (Rottemburg, 1775) and P. stempfferi (Brandt, 1938) since they were earlier inferred as the outgroups to the subgenus Agrodiaetus 28. Substitution models were inferred by the hierarchical likelihood ratio, Akaike and Bayesian information criteria tests, as implemented in jModelTest278, models were evaluated separately for each gene. ML analysis was conducted using RAxML Black Box79 on the CIPRES Science Gateway platform80. Ten independent search replicates were run under the GTR model. Bootstrap support values for nodes on the ML topology were computed with RAxML rapid bootstraping algorithm81 by running 700 bootstrap replicates. Bayesian analysis was conducted using MrBayes 3.282 on four molecular (COI, COII, leu-tRNA and 5.8S rDNA + ITS2 + 28S rDNA genes) and one “standard” (binary) partitions using 7 million generations. Two independent runs were performed, each with four chains (three heated and one cold), using independent-gamma rate relaxed clock model with uniform branch lengths. Trees were sampled at intervals of every 2,000 generations. Stationarity was determined by examining log-likelihood scores plotted across generations with Tracer (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/), plotting posterior probabilities of all splits for paired MCMC runs by AWTY on-line service83 and by examining standard deviation of split frequencies between the two runs for convergence. Of the 3,501 trees sampled in each run, first 5% were discarded as burn-in and the remaining trees were used to construct a 50% majority rule consensus phylogram.

Phylogenetic signal and mode of evolution

Following approach suggested by Hipp10 and taking into account the lack of visual markers in holocentric chromosomes, we used only chromosome number “as a proxy for karyotype” and modeled chromosome number evolution as an evolution of a quantitative continuous character. Frequency of chromosome fusions and fissions depends on the number of chromosomes. Therefore, haploid chromosome numbers were log-transformed prior to phylogenetic comparative analysis.

To make the sampling as complete as possible we used all chromosome data available, including our own previously published results3, 30–34, 76, 84–91. In the analysis, the majority of the tips on the phylogenetic tree refer to species (Supplementary Table S1). In cases of intraspecific chromosomal variations, chromosomal races (i.e., populations with stable differentiated karyotypes) were used as entities for phylogenetic comparative analysis (in this cases tips on the phylograms refer to populations). Such cases were found in P. cyaneus, P. damocles, P. demavendi, P. dolus, P. elbursicus, P. firdussii, P. iphigenia, P. mithridates, P. rjabovi and P. sennanensis. For five species karyotype data are absent and we excluded them from the phylogenetic comparative analysis (P. actinides, P. dagmara, P. magnificus, P. mediator, P. pulcher). To incorporate phylogenetic uncertainty into analysis the entire comparative approach was carried out on 1000 ultrametric randomly chosen post burn-in phylograms92.

All computational procedures were performed using R packages for phylogenetic comparative methods: ape93, geiger: fitContinuous94, caper: pgls (https://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/caper/), phytools: phylosig95 and qpcR: akaike.weights (https://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/qpcr/).

Data Availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information file.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Alexander Dantchenko and Nazar Shapoval for provided samples and sequences. We are also very grateful to Valentina Kuznetsova for laboratory facilities and valuable discussion. The financial support for this study was provided by the grant N 14-14-00541 from the Russian Science Foundation to the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The work was partially performed using equipment of the ‘Chromas’ Core Facility, Centre for Molecular and Cell Technologies and Department of Entomology of St. Petersburg State University. A part of this equipment was purchased with support of the St. Petersburg University grant 1.40.490.2017.

Author Contributions

V.L. and A.V. designed research and acquired data, A.V. synthesized data and performed computational procedures, V.L. interpreted data, A.V. and V.L. wrote the paper.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08525-6

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alisa O. Vershinina, Email: vershininaalissa@gmail.com

Vladimir A. Lukhtanov, Email: lukhtanov@mail.ru

References

- 1.Sumner, A. T. Chromosomes: Organization and Function (Wiley-Blackwell, 2003).

- 2.Faria R, Navarro A. Chromosomal speciation revisited: rearranging theory with pieces of evidence. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010;25:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kandul NP, Lukhtanov VA, Pierce NE. Karyotypic diversity and speciation in Agrodiaetus butterflies. Evolution. 2007;61:546–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butlin RK. Recombination and speciation. Mol. Ecol. 2005;14:2621–2635. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pringle EG, et al. Synteny and chromosome evolution in the lepidoptera: evidence from mapping in Heliconius melpomene. Genetics. 2007;177:417–26. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.073122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larkin DM, et al. Breakpoint regions and homologous synteny blocks in chromosomes have different evolutionary histories. Genome Res. 2009;19:770–777. doi: 10.1101/gr.086546.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dincă V, Lukhtanov VA, Talavera G, Vila R. Unexpected layers of cryptic diversity in wood white Leptidea butterflies. Nat. Commun. 2011;2:324. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lukhtanov VA, Dincă V, Talavera G, Vila R. Unprecedented within-species chromosome number cline in the Wood White butterfly Leptidea sinapis and its significance for karyotype evolution and speciation. BMC Evol. Biol. 2011;11:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dumont, B. L. & Payseur, B. A. Genetic analysis of genome-scale recombination rate evolution in house mice. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002116, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Hipp AL. Nonuniform processes of chromosome evolution in sedges (Carex: Cyperaceae) Evolution. 2007;61:2175–2194. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Avelar AT, Perfeito L, Gordo I, Ferreira MG. Genome architecture is a selectable trait that can be maintained by antagonistic pleiotropy. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2235. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nguyen P, Sahara K, Yoshido A, Marec F. Evolutionary dynamics of rDNA clusters on chromosomes of moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera) Genetica. 2010;138:343–354. doi: 10.1007/s10709-009-9424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Šíchová J, Nguyen P, Dalíková M, Marec F. Chromosomal evolution in tortricid moths: conserved karyotypes with diverged features. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romanov MN, et al. Reconstruction of gross avian genome structure, organization and evolution suggests that the chicken lineage most closely resembles the dinosaur avian ancestor. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:1060. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vershinina AO, Anokhin Ba, Lukhtanov VA. Ribosomal DNA clusters and telomeric (TTAGG)n repeats in blue butterflies (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) with low and high chromosome numbers. Comp. Cytogenet. 2015;9:161–171. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i2.4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White MJD. Chain processes in chromosomal speciation. Syst. Zool. 1978;27:285–298. doi: 10.2307/2412880. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King, M. G. Species Evolution. The Role of Chromosome Change. (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- 18.Coyne, J. A. & Orr, A. H. Speciation. (Sinauer Associates, 2004).

- 19.Robinson, R. Lepidoptera genetics. (Pergamon Press, 1971).

- 20.Lukhtanov VA. Sex chromatin and sex chromosome systems in nonditrysian Lepidoptera (Insecta) J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2000;38:73–79. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0469.2000.382130.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukhtanov VA. Chromosome number evolution in skippers (Lepidoptera, Hesperiidae) Comp. Cytogenet. 2014;8:275–291. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v8i4.8789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahola V, et al. The Glanville fritillary genome retains an ancient karyotype and reveals selective chromosomal fusions in Lepidoptera. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4737. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook LG. Extraordinary and extensive karyotypic variation: A 48-fold range in chromosome number in the gall-inducing scale insect Apiomorpha (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Eriococcidae) Genome. 2000;43:255–263. doi: 10.1139/g99-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown KS, Von Schoultz B, Suomalainen E. Chromosome evolution in Neotropical Danainae and Ithomiinae (Lepidoptera) Hereditas. 2004;141:216–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5223.2004.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Šíchová J, et al. Dynamic karyotype evolution and unique sex determination systems in Leptidea wood white butterflies. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015;15:89. doi: 10.1186/s12862-015-0375-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Šíchová J, et al. Fissions, fusions, and translocations shaped the karyotype and multiple sex chromosome constitution of the northeast-Asian wood white butterfly. Leptidea amurensis. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2016;118:457–471. doi: 10.1111/bij.12756. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talavera G, Lukhtanov VA, Rieppel L, Pierce NE, Vila R. In the shadow of phylogenetic uncertainty: The recent diversification of Lysandra butterflies through chromosomal change. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013;69:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talavera G, Lukhtanov VA, Pierce NE, Vila R. Establishing criteria for higher-level classification using molecular data: the systematics of Polyommatus blue butterflies (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) Cladistics. 2013;29:166–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukhtanov VA, Dantchenko AV. Principles of the highly ordered arrangement of metaphase I bivalents in spermatocytes of Agrodiaetus (Insecta, Lepidoptera) Chromosome Res. 2002;10:5–20. doi: 10.1023/A:1014249607796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kandul NP, et al. Phylogeny of Agrodiaetus Hübner 1822 (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) inferred from mtDNA sequences of COI and COII and nuclear sequences of EF1- α: karyotype diversification and species radiation. Syst. Biol. 2004;53:278–298. doi: 10.1080/10635150490423692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukhtanov VA, et al. Reinforcement of pre-zygotic isolation and karyotype evolution in Agrodiaetus butterflies. Nature. 2005;436:385–389. doi: 10.1038/nature03704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lukhtanov VA, Vila R, Kandul NP. Rearrangement of the Agrodiaetus dolus species group (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) using a new cytological approach and molecular data. Insect Syst. Evol. 2006;37:325–334. doi: 10.1163/187631206788838563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukhtanov VA, Shapoval NA, Anokhin BA, Saifitdinova AF, Kuznetsova VG. Homoploid hybrid speciation and genome evolution via chromosome sorting. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2015;282(1807):20150157. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lukhtanov V. The blue butterfly Polyommatus (Plebicula) atlanticus (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) holds the record of the highest number of chromosomes in the non-polyploid eukaryotic organisms. Comp. Cytogenet. 2015;9:683–690. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i4.5760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimabukuro-Dias CK, Oliveira C, Foresti F. Cytogenetic analysis of five species of the subfamily Corydoradinae (Teleostei: Siluriformes: Callichthyidae) Genet. Mol. Biol. 2004;27:549–554. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572004000400014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmerman E. Karyology, systematics and chromosomal evolution in the rodent genus, Sigmodon. Publ. Museum, Michigan State Univ. Biol. Ser. 1970;4:385–454. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parededa MG, Novello A. Chromosome mosaicism: extreme karyotype variation in the genus Ctenomys from Uruguay (Rodentia: Ctenomydae) Caryologia. 2012;65:251–257. doi: 10.1080/00087114.2012.752907. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang W, Lan H. Rapid and parallel chromosomal number reductions in muntjac deer inferred from mitochondrial DNA phylogeny. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:1326–1333. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung K-S, Hipp AL, Roalson EH. Chromosome number evolves independently of genome size in a clade with nonlocalized centromeres (Carex: Cyperaceae) Evolution. 2012;66:2708–2722. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eichler EE, Sankoff D. Structural dynamics of eukaryotic chromosome evolution. Science. 2003;301:793–797. doi: 10.1126/science.1086132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leitch IJ, Beaulieu JM, Chase MW, Leitch AR, Fay MF. Genome size dynamics and evolution in monocots. J. Bot. 2010;2010:1–18. doi: 10.1155/2010/862516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vershinina AO, Lukhtanov VA. Dynamics of chromosome number evolution in the Agrodiaetus phyllis species complex (Insecta: Lepidoptera) Cell Tissue Biol. 2013;7:379–381. doi: 10.1134/S1990519X13040159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White, M. J. D. Animal cytology and evolution (Cambridge University Press, 1973).

- 44.Pagel M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature. 1999;401:877–884. doi: 10.1038/44766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blomberg SP, Garland T, Ives AR. Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: behavioral traits are more labile. Evolution. 2003;57:717–45. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harvey PH, Purvis A. Comparative methods for explaining adaptations. Nature. 1991;351:619–624. doi: 10.1038/351619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harvey PH, Rambaut A. Comparative analyses for adaptive radiations. Phil.Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 2000;355:1599–1605. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freckleton RP, Harvey PH, Pagel M. Phylogenetic analysis and comparative data: a test and review of evidence. Am. Nat. 2002;160:712–26. doi: 10.1086/343873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Butler MA, King AA. Phylogenetic comparative analysis: a modeling approach for adaptive evolution. Am. Nat. 2004;164:683–695. doi: 10.1086/426002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hansen TF. Stabilizing selection and the comparative analysis of adaptation. Evolution. 1997;51:1341–1351. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb01457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Posada D, Buckley TR. Model selection and model averaging in phylogenetics: advantages of Akaike information criterion and Bayesian approaches over likelihood ratio tests. Syst. Biol. 2004;53:793–808. doi: 10.1080/10635150490522304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pagel, M. Modelling the evolution of continuously varying characters on phylogenetic trees: the case of Hominid cranial capacity in Morphology, Shape and Phylogeny (ed. MacLeod, N. & Forey, P.L.) 269–286 (CRC Press, 2002).

- 54.Baker RJ, Bickham JW. Karyotypic evolution in bats: Evidence of extensive and conservative chromosomal evolution in closely related taxa. Syst. Zool. 1980;29:239–253. doi: 10.2307/2412660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baker RJ, Bickham JW. Karyotypic megaevolution by any other name: a response to Marks. Syst. Zool. 1984;33:339–341. doi: 10.2307/2413080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bell DM, et al. Patterns of karyotypic megaevolution in Reithrodontomys: evidence from a cytochrome-b phylogenetic hypothesis. J. Mammal. 2001;82:81–91. doi: 10.1644/1545-1542(2001)082<0081:POKMIR>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Revell LJ, Harmon LJ. Testing quantitative genetic hypotheses about the evolutionary rate matrix for continuous characters. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2008;10:311–331. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nunn, C. L. The comparative approach in evolutionary anthropology and biology (University of Chicago Press, 2011).

- 59.Beaulieu JM, Jhwueng D-C, Boettiger C, O’Meara BC. Modeling stabilizing selection: expanding the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck model of adaptive evolution. Evolution. 2012;66:2369–2383. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rieseberg LH. Chromosomal rearrangements and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2001;16:351–358. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Solovei I, et al. Nuclear architecture of rod photoreceptor cells adapts to vision in mammalian evolution. Cell. 2009;137:356–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Noor MAF, Grams KL, Bertucci LA, Reiland J. Chromosomal inversions and the reproductive isolation of species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:12084–12088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221274498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Navarro A, Barton NH. Accumulating postzygotic isolation genes in parapatry: a new twist on chromosomal speciation. Evolution. 2003;57:447–459. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb01537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ayala FJ, Coluzzi M. Chromosome speciation: humans, Drosophila, and mosquitoes. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6535–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501847102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baker RJ, Bickham JW. Speciation by monobrachial centric fusions. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1986;83:8245–8248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.21.8245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagaraju J, Jolly MS. Interspecific hybrids of Antheraea roylei and A. pernyi — a cytogenetic reassessment. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1986;72:269–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00267003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dincă V, et al. Reproductive isolation and pattern of genetic differentiation in a cryptic butterfly species complex. J. Evol. Biol. 2013;26:2095–2106. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nachman MW, Myers P. Exceptional chromosomal mutations in a rodent population are not strongly underdominant. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:6666–6670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veyrunes F, et al. Autosome and sex chromosome diversity among the African pygmy mice, subgenus Nannomys (Murinae; Mus) Chromosome Res. 2004;12:369–382. doi: 10.1023/B:CHRO.0000034098.09885.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lyapunova EA, Bakloushinskaya IY, Saidov AS, Saidov KK. Dynamics of chromosome variation in mole voles Ellobius tancrei (Mammalia, Rodentia) in Pamiro-Alay in the period from 1982 to 2008. Russ. J. Genet. 2010;46:566–571. doi: 10.1134/S1022795410050091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolf KW, Ak KN, Marec F. Kinetic organization of metaphase I bivalents in spermatogenesis of Lepidoptera and Trichoptera species with small chromosome numbers. Heredity. 1997;79:135–143. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1997.136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carpenter, J. E., Bloem, S. & Marec, F. Inherited sterility in insects in Sterile Insect Technique (eds Dyck, V. A., Hendrichs, J. & Robinson, A. S.) 115–146, doi:10.1007/1-4020-4051-2_5 (Springer, 2005).

- 73.Mola LM, Papeschi AG. Holokinetic chromosomes at a glance. J. Basic Appl. Genetics. 2006;17:17–33. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bureš P, Zedek F. Holokinetic drive: centromere drive in chromosomes without centromeres. Evolution. 2014;68:2412–2420. doi: 10.1111/evo.12437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic acids symposium series. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Egan AN, Crandall KA. Incorporating gaps as phylogenetic characters across eight DNA regions: ramifications for North American Psoraleeae (Leguminosae) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008;46:532–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wiemers M, Keller A, Wolf M. ITS2 secondary structure improves phylogeny estimation in a radiation of blue butterflies of the subgenus Agrodiaetus (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae: Polyommatus) BMC Evol. Biol. 2009;9:300. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Meth. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miller JR, Koren S, Sutton G. Assembly algorithms for next-generation sequencing data. Genomics. 2010;95:315–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 2008;57:758–771. doi: 10.1080/10635150802429642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ronquist F, et al. Mrbayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nylander JAA, Wilgenbusch JC, Warren DL, Swofford DL. AWTY (are we there yet?): A system for graphical exploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetics. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:581–583. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wiemers, M. Chromosome differentiation and the radiation of the butterfly subgenus Agrodiaetus (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae: Polyommatus) – a molecular phylogenetic approach. (Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, 2003).

- 85.Lukhtanov VA, Shapoval NA, Dantchenko VA. Agrodiaetus shahkuhensis sp. n. (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae), a cryptic species from Iran discovered by using molecular and chromosomal markers. Comp. Cytogenet. 2008;2:94–114. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wiemers M, Fiedler K. Does the DNA barcoding gap exist? – a case study in blue butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) Front. Zool. 2007;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vershinina A, Lukhtanov V. Geographical distribution of the cryptic species Agrodiaetus alcestis alcestis, A. alcestis karacetinae and A. demavendi (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) revealed by cytogenetic analysis. Comp. Cytogenet. 2010;4:1–11. doi: 10.3897/compcytogen.v4i1.21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lukhtanov VA, Shapoval NA, Dantchenko AV. Taxonomic position of several enigmatic Polyommatus (Agrodiaetus) species (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) from Central and Eastern Iran: insights from molecular and chromosomal data. Comp. Cytogenet. 2014;8:313–322. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v8i4.8939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lukhtanov VA, Dantchenko AV, Vishnevskaya MS, Saifitdinova AF. Detecting cryptic species in sympatry and allopatry: analysis of hidden diversity in Polyommatus (Agrodiaetus) butterflies (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae) Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2015;116:468–485. doi: 10.1111/bij.12596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lukhtanov VA, Tikhonov VV. Chromosomal and molecular evidence for presence of Polyommatus (Agrodiaetus) poseidon (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) in Caucasus region. Comp. Cytogenet. 2015;9:249–255. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v9i2.5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vishnevskaya MS, Saifitdinova AF, Lukhtanov VA. Karyosystematics and molecular taxonomy of the anomalous blue butterflies (Lepidoptera, Lycaenidae) from the Balkan Peninsula. Comp. Cytogenet. 2016;10(5):1–85. doi: 10.3897/CompCytogen.v10i5.10944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pagel, M. & Lutzoni, F. Accounting for phylogenetic uncertainty in comparative studies of evolution and adaptation in Biological Evolution and Statistical Physics (eds Laessig, M. & Valleriani, A.) 148–161 (Springer Verlag, 2002).

- 93.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. APE: Analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:289–290. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harmon LJ, Weir JT, Brock CD, Glor RE, Challenger W. GEIGER: investigating evolutionary radiations. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:129–131. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Revell L. J. phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things) Methods Ecol. Evol. 2012;3:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information file.