Abstract

To elucidate the temporal changes in the radiocesium distribution in forests contaminated by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident, we monitored the 137Cs concentration and inventory within forests from 2011 to 2015 across nine plots containing variable tree species and different contamination levels. The 137Cs concentrations in needles and branches decreased exponentially at all coniferous plots, with effective ecological half-lives of 0.45–1.55 yr for needles and 0.83–1.69 yr for branches. By contrast, the 137Cs concentration in deciduous konara oak leaves did not change over the five years. The concentration of 137Cs in oak wood increased by 37–75%, whereas that in Japanese red pine decreased by 63% over the five years. In Japanese cedar and hinoki cypress, the 137Cs concentration in wood showed an increasing trend in half of the plots. The changes in 137Cs in the organic and mineral soil layers were not strongly related to the tree species or contamination level. Our multi-site, multi-species monitoring results revealed that the pattern of temporal changes in radiocesium in the 9 forest plots was similar overall; however, changes in 137Cs in needles/leaves and wood differed among tree species.

Introduction

After the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP) accident, a large volume of radionuclides was released into the atmosphere. Consequently, serious radioactive fallout resulted over a broad area of northeastern Japan1, 2, which is mostly covered by forests (ca. 70%). Radiocesium isotopes (137Cs and 134Cs) with long physical half-lives, particularly 137Cs (30 years), represented a major portion of the radionuclides released as a result of the accident. Therefore, prolonged 137Cs contamination in these forest ecosystems is a major concern3.

Such forest contamination has resulted in a decline in timber production and a variety of additional problems, including the contamination of edible forest products, such as wild mushrooms, plants, and animals, and risks of internal and external exposure to forest workers and local residents. To facilitate the application of countermeasures and to evaluate the risks of these exposures, monitoring the temporal changes in the 137Cs concentration and inventory in contaminated forests is essential. In Fukushima and the surrounding prefectures of Ibaraki and Tochigi, approximately 30% of the forests are dedicated to coniferous plantation for timber production, with Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) and hinoki cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa) as the two main plantation species4. Secondary forests are also commonly found in this area, where deciduous broad-leaved (DBL) species such as konara oak (Quercus serrata) predominate. Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora) is often found with broad-leaved trees in mixed forests. Due to the presence of such diverse forest types and terrain characteristics, temporal changes in the 137Cs distribution within forests may differ across sites. In addition to the various forest types found in these areas, an airborne survey revealed that contamination levels vary between locations by several orders of magnitude5. Although the influence of the difference in contamination level to 137Cs behaviour in forests would be negligibly small6, it would be beneficial to confirm the similarity in 137Cs behaviour in forests with different contamination levels. Therefore, monitoring the temporal changes in 137Cs at multiple plots covering various forest types and contamination levels is important to document the overall temporal changes in the 137Cs concentration and inventory across broad areas of contaminated forest.

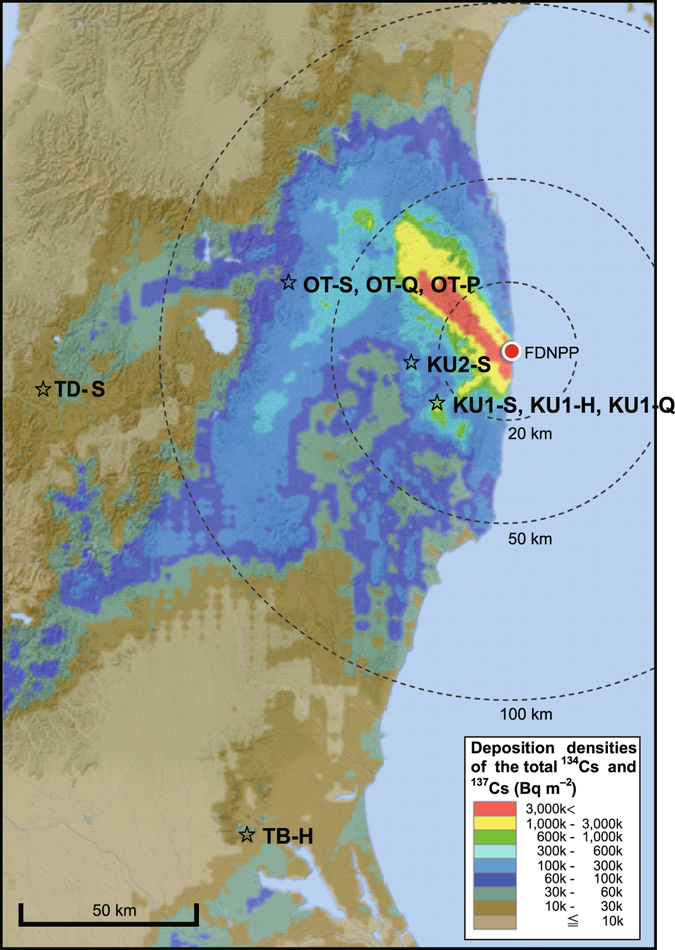

We began monitoring the radiocesium (137Cs and 134Cs) contamination in trees and soils in August 2011 (half a year after the accident) in five forest plots that differed in terms of the contamination level and dominant species (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The monitoring plots included three Japanese cedar plantations in Kawauchi Village (26 km from the FDNPP), Otama Village (66 km), and Tadami Town (134 km) (referred to as KU1-S, OT-S, and TD-S, respectively) and two mixed forest plots adjacent to OT-S that were dominated by broad-leaved trees (OT-Q) or Japanese red pine (OT-P). In these plots, we monitored the concentrations and inventories of radiocesium in needles/leaves, branches, bark, wood, soil surface organic layer, and mineral soil layers. In our previous paper, we reported the 137Cs distributions in forests observed in the summer of 2011, representing the phase immediately following the contamination7. The first year of observations revealed that the ratio of aboveground 137Cs (needles/leaves, branches, bark, and wood) to the total amount of 137Cs deposited in the forests varied from 18 to 52% across the various sites. Belowground, most of the 137Cs was distributed across the organic layer (16–49%) and along the mineral soil surfaces (20–44%) in 2011. Radiocesium was also detected in the internal tissues of trees (sapwood and heartwood), which had not been exposed to deposition, although these concentrations were much lower than those in the external tissues (needles/leaves, branches, and bark).

Table 1.

General characteristics, biomass of aboveground components, and forest floor surface densities of belowground components at the study plots.

| Plot | KU1-S | KU1-H | KU1-Q | KU2-S | OT-S | OT-Q | OT-P | TD-S | TB-H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latitude | 37°17′18″ | 37°17′22″ | 37°17′22″ | 37°22′53″ | 37°34′40″ | 37°34′15″ | 37°34′14″ | 37°19′28″ | 36°10′22″ |

| Longitude | 140°47′48″ | 140°47′33″ | 140°47′30″ | 140°42′58″ | 140°18′20″ | 140°18′29″ | 140°18′30″ | 139°31′15″ | 140°10′33″ |

| Distance from FDNPP (km) | 26 | 27 | 27 | 28 | 66 | 66 | 66 | 134 | 160 |

| Elevation (m) | 660 | 720 | 720 | 690 | 730 | 760 | 750 | 790 | 360 |

| Topography | Flat and steep | Flat | Flat | Flat | Flat and steep | Flat | Flat | Steep | Steep |

| Air dose rate at 1 m height (μSv h−1)a | 3.05 ± 0.42 | 3.70 ± 0.22 | 3.16 ± 0.09 | 1.29 ± 0.39 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

| 137Cs deposition (kBq m−2)b | 630 | 470 | 470 | 160 | 41 | 44 | 44 | 10 | 33 |

| Dominant sp. | Cryptomeria japonica | Chamaecyparis obtusa | Quercus serrata | Cryptomeria japonica | Cryptomeria japonica | Quercus serrata | Pinus densiflora | Cryptomeria japonica | Chamaecyparis obtusa |

| Stand age (yr) | 43 | 26 | 26 | 57 | 42 | 43 | 43 | 38 | 43 |

| Density (ha−1)c | 975/569 | 1330/− | −/1750 | 733/225 | 1117/− | 550/654 | 938/375 | 1105/133 | 2133/− |

| Mean DBH (cm)c | 18.8/14.3 | 17.6/− | −/13.1 | 30.9/25.8 | 24.8/− | 19.0/17.5 | 18.8/15.6 | 19.9/17.2 | 20.6/− |

| Aboveground (kg m−2)c | |||||||||

| Needles/leaves | 1.2–1.4/0.2 | 0.9–1.2 /− | −/0.3 | 3.0–3.3/0.00 | 2.3–2.7/− | 0.3/0.3 | 0.4–0.5/0.1–0.2 | 1.5–1.8/0.1 | 2.3–2.5/− |

| Branches | 0.7–0.9/0.8–0.9 | 1.1–1.6/− | −/1.2 | 2.6–2.9/0.02 | 1.5–1.8/− | 0.7/1.3–1.5 | 1.0–1.1/0.6–0.7 | 0.9–1.1/0.3–0.4 | 3.2–3.6/− |

| Bark | 0.4–0.5/0.7 | 0.6–0.8/− | −/1.1 | 1.0–1.5/0.01–0.02 | 0.9–1.0/− | 0.3/0.6–0.7 | 0.4/0.3–0.4 | 0.7–0.8/0.2 | 1.0–1.6/− |

| Wood | 6.6–8.1/3.3–3.7 | 9.9–12.7/− | −/6.0 | 19.7–21.0/0.1 | 13.7–16.6/− | 4.4–4.8/4.2–4.8 | 6.6–6.9/2.1–2.5 | 8.3–10.8/0.9–1.3 | 23.6–26.7/− |

| Tree total | 8.9–10.8/5.0–5.5 | 12.5–16.4/− | −/8.6 | 26.2–28.7/0.1–0.2 | 18.4–22.0/− | 5.7–6.1/6.4–7.2 | 8.4–8.8/3.2–3.7 | 11.3–14.4/1.4–1.9 | 30.2–34.3/− |

| Belowground (kg m−2) | |||||||||

| Organic layer | 1.1–1.6 | 1.1–1.5 | 1.0–1.2 | 1.4–2.8 | 1.6–2.1 | 0.9–1.5 | 1.0–1.7 | 1.1–1.6 | 0.8–1.5 |

| Mineral soil 0–5 cm | 15.7–19.6 | 14.4–17.2 | 18.0–19.4 | 10.8–14.6 | 11.9–14.3 | 13.9–17.9 | 16.2–18.7 | 15.3–21.3 | 16.5–17.4 |

| Mineral soil 5–10 cm | 22.8–29.6 | 22.8–23.8 | 23.4–26.2 | 14.6–22.6 | 17.6–19.0 | 24.2–25.8 | 23.7–28.7 | 21.8–33.1 | 24.1–26.6 |

| Mineral soil 10–15 cm | 27.1–32.7 | 22.6–27.3 | 27.9–29.7 | 22.5–28.3 | 19.9–22.4 | 26.4–30.8 | 25.1–28.8 | 27.6–47.4 | 25.6–27.4 |

| Mineral soil 15–20 cm | 29.5–36.3 | 24.7–27.8 | 30.1–33.8 | 23.8–29.3 | 20.5–25.0 | 28.3–31.6 | 24.3–32.2 | 33.7–40.9 | 23.5–27.6 |

| Sampling date | |||||||||

| 2011 | 31 Aug | — | — | 28 Nov | 9, 11 Aug | 9–10 Aug | 9–10 Aug | 7–8 Sep | 16 Feb, 2012 |

| 2012 | 23, 27 Aug | 24, 28 Aug | 24, 28 Aug | 20 Sep | 1, 6 Aug | 2, 7 Aug | 2, 7 Aug | 3–4 Sep | 28 Jan, 5 Feb, 2013 |

| 2013 | 26 Aug | 27 Aug | 27 Aug | 27–28 Aug | 1, 5 Aug | 2, 6 Aug | 1–2, 6 Aug | 4, 10–11 Sep | 25 Sep, 3 Oct |

| 2014 | 25–26 Aug, 3 Sep | 26 Aug, 3 Sep | 26–27 Aug | 27 Aug, 17 Sep | 29–30 Jul | 30 Jul–1 Aug | 29 Jul–1 Aug | 1–3 Sep | 30 Sep–2 Oct |

| 2015 | 25 Aug | 25–26 Aug | 26 Aug | 26–27 Aug | 4 Aug | 5 Aug | 4–5 Aug | 2–3 Sep | 28, 30 Sep |

aThe air dose rates are the averages and SD (n = 6 at KU1-H and KU1-Q, n = 20 at KU2-S and TB-H, n = 27 at KU1-S, n = 32 at TD-S, and n = 36 at OT-Q and OT-P) from the first observation date.

bThe deposition of 137Cs at each plot was obtained from the 5th airborne monitoring survey data collected on 28 June 2012 and reported on the website “Extension Site of Distribution Map of Radiation Dose, etc.” prepared by MEXT, Japan31.

cFor each component of every plot, the results for coniferous trees are shown on the left, and those for broad-leaved trees are shown on the right of each slash to denote the stand density, mean DBH, and aboveground biomass. The aboveground and belowground value are the ranges over the 4–5 years of the study.

Figure 1.

Locations of the study plots. The study plots are shown in a distribution map of 137Cs and 134Cs deposition levels on June 28, 2012 that was generated using the website “Extension Site of Distribution Map of Radiation Dose, etc”. prepared by MEXT, Japan31. The Extension Site of Distribution Map of Radiation Dose, etc., was created by editing GSI Tiles (elevation)39. KU1 and KU2: Kawauchi sites, OT: Otama site, TD: Tadami site, TB: Mt. Tsukuba site; -S: Japanese cedar plot; -H: hinoki cypress plot; -Q: DBL species-dominant plot; -P: Japanese red pine-dominant plot.

As shown in studies on the Chernobyl incident, the distribution of 137Cs in forests changes with time, especially over the first 4–5 years after an accident. Aboveground 137Cs can migrate to underlying soils via litterfall, throughfall, and stemflow8, and the proportion of 137Cs in soils eventually increases. In addition, changes in 137Cs transfer to wood are of serious concern with regards to the future resumption of timber production. Since 2011, we have continued to monitor the abovementioned five plots in Fukushima to capture the changes in the 137Cs distribution in these forests. In addition, we established four new plots in 2011 or 2012, with continued monitoring: a hinoki cypress forest (KU1-H) and a broad-leaved forest (KU1-Q) located close to KU1-S, a Japanese cedar forest (KU2-S) located in the same village as KU1-S but possessing a smaller contamination level from that at KU1-S, and a hinoki cypress forest in Ishioka City (TB-H) located 160 km away from the FDNPP and possessing a similar contamination level as that at TD-S.

This paper reports our five-year (2011–2015) monitoring of the radiocesium distributions across nine forest plots containing variable tree species and different contamination levels. We sought to describe and quantify the overall changes in the 137Cs distributions within the forests based on our monitoring data, and we discuss the similarities and differences in these changes within forests among the plots.

Results

Radiocesium concentrations

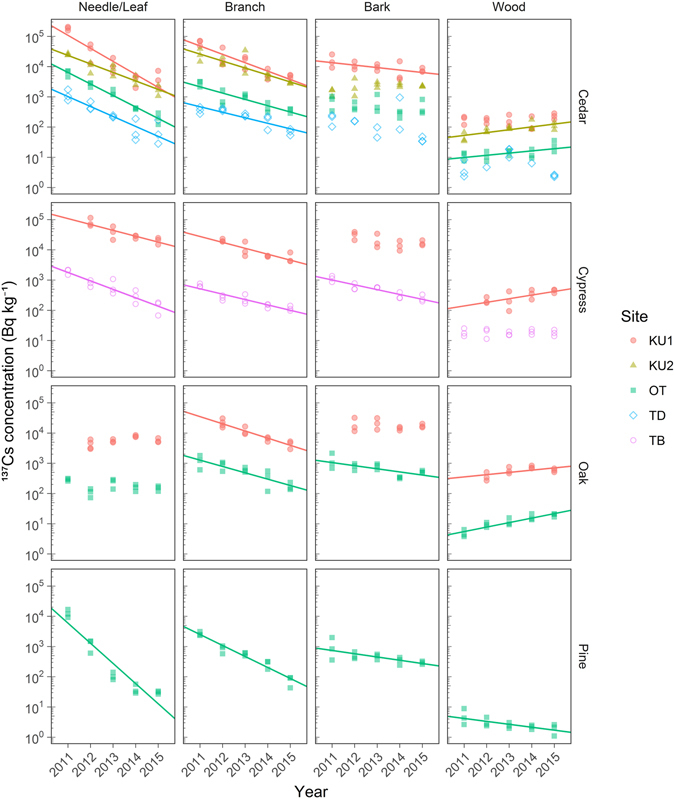

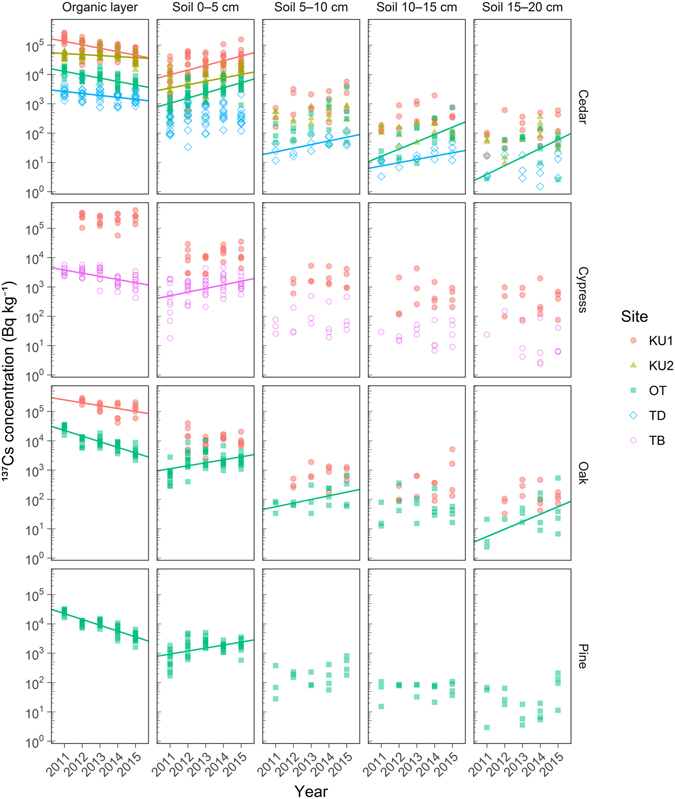

Figures 2 and 3 show the five-year changes in the 137Cs concentration (decay corrected to September 1 of each year and log-transformed) in needles/leaves, branches, bark, wood, the organic layer, and four mineral soil layers (0–5 cm, 5–10 cm, 10–15 cm, and 15–20 cm) for each study plot. Regression lines were drawn where the slopes were significantly positive or negative (p < 0.05). Note that the 137Cs concentrations did not necessarily change exponentially, particularly in the mineral soil layers, in which the 137Cs concentration first increased from 2011 to 2012 and then fluctuated (see cedar and oak plots in Fig. 3). The annual means and standard deviations (SDs) of the 137Cs (and 134Cs) concentration in each component are shown online in Supplementary Table S1 of the supplementary information section.

Figure 2.

Time series of needle/leaf, branch, bark, and wood 137Cs concentrations at each study plot. For individual samples, log-transformed 137Cs concentrations above the detection limit were plotted against the sampling year. Maximum likelihood regression analysis was performed for data below the detection limit38. Significant trends between the log-transformed concentration and sampling year (linear regression analysis, p < 0.05) are denoted by solid lines. The sampling period was August–September in each year except at KU2-S in 2011 (November 2011) and TB-H in 2011 and 2012 (February 2012 and February 2013, respectively). The radiocesium concentration was decay corrected to September 1 of each sampling year.

Figure 3.

Time series of organic layer and mineral soil layer (0–5 cm, 5–10 cm, 10–15 cm, and 15–20 cm) 137Cs concentrations at each study plot. For individual samples, log-transformed 137Cs concentrations above the detection limit were plotted against the sampling year. Maximum likelihood regression analysis was performed for data below the detection limit38. Significant trends between the log-transformed concentration and sampling year (linear regression analysis, p < 0.05) are denoted by solid lines. The sampling period was August–September in each year except at KU2-S in 2011 (November 2011) and TB-H in 2011 and 2012 (February 2012 and February 2013, respectively). The radiocesium concentration was decay corrected to September 1 of each sampling year.

Overall, the 137Cs concentrations in each component were positively correlated with the total level of deposition; 137Cs concentrations were highest at KU1-S (630 kBq m−2 in 137Cs deposition based on aerial survey) and lowest at TD-S (10 kBq m−2 in 137Cs deposition) (Figs 2 and 3 and Table 1). Needles, branches, bark, the organic layer, and the shallowest mineral soil layer (0–5 cm) (directly exposed to air) contained higher concentrations than wood and deeper mineral soil layers (not exposed to air). The 137Cs concentrations in needles, branches, and the organic layer showed clear decreasing trends, whereas those in wood and the shallowest soil layer (0–5 cm) showed increasing trends at the majority of plots. To remove the effect of radioactive decay on temporal 137Cs changes, we also conducted regression analysis using 137Cs data that was decay corrected to March 11, 2011 (Supplementary Figs S1 and S2). The decay correction to March 11, 2011, resulted in insignificant decreasing trends in bark at KU1-S and the organic layer at KU2-S and significant increasing trends in leaves at KU1-Q, bark at KU2-S, mineral soil (0–5 cm) at TD-S, and mineral soil (5–10 cm) at OT-S and OT-P. Most detected trends were not affected by the correction to March 11, 2011, suggesting that the trends observed in our study primarily resulted from radiocesium transfer.

The concentration of 137Cs in needles decreased exponentially at all coniferous plots (Fig. 2). The effective ecological half-lives of 137Cs in the needles were 0.70 (KU1-S), 1.07 (KU2-S), 0.79 (OT-S), 0.91 (TD-S), 1.55 (KU1-H), 1.08 (TB-H), and 0.45 (OT-P) yr, being shortest in Japanese red pine needles at OT-P and longest in hinoki cypress needles at KU1-H. The 137Cs concentration in the Japanese red pine needles in 2015 was to 0.2% of the initial concentration (2011), whereas those in the Japanese cedar and hinoki cypress needles in 2015 were 2–7% of the initial respective concentrations. The 137Cs concentration in oak leaves at the first monitoring time point (2011 for OT and 2012 for KU1) was approximately one-tenth of that in coniferous needles sampled at the adjacent plot in the same site and did not change over the monitoring period (5 years for OT and 4 years for KU1). Consequently, as of 2015, the 137Cs concentration in the oak leaves was the same order of magnitude as that in the coniferous needles at KU1 and OT. The concentration of 137Cs in branches exponentially decreased at all the study plots (Fig. 2). The effective ecological half-lives of 137Cs in the branches were 1.09 (KU1-S), 1.30 (KU2-S), 1.44 (OT-S), 1.65 (TD-S), 1.54 (KU1-H), 1.69 (TB-H), 1.27 (KU1-Q), 1.44 (OT-Q), and 0.83 (OT-P) yr. Similar to the needles, the 137Cs concentration in the branches of Japanese red pine decreased the fastest among the studied species. The concentration of 137Cs in bark decreased by 53–78% over the 4–5 years at four plots (KU1-S, TB-H, OT-Q, and OT-P) and did not show clear temporal variations at the other five plots (Fig. 2). The 137Cs concentration increased by 37–75% in konara oak wood (KU1-Q and OT-Q) during the 4–5 years and decreased by 63% in Japanese red pine wood (OT-P) over the 5 years (Fig. 2). The concentration of 137Cs in Japanese cedar and hinoki cypress woods showed increasing trends at half of the plots (Fig. 2).

In the organic layer, the 137Cs concentration decreased by 28–86% over the 4–5 years at all the plots except KU1-H (Fig. 3). Exponential decreasing trends were clearly observed at some plots (KU1-S, OT-S, TD-S, TB-H, OT-Q, and OT-P). In the surface mineral soil layer (0–5 cm), the concentration of 137Cs increased by 43–82% over the five years at six (KU1-S, KU2-S, OT-S, TB-H, OT-Q, and OT-P) of the nine plots (Fig. 3). Regarding annual changes, the 137Cs concentration in the surface mineral soil layer at some plots increased rapidly from 2011 to 2012 and then levelled off or fluctuated in later years (Soil 0–5 cm in Fig. 3). In deeper mineral soil layers (below 5 cm), the concentrations of 137Cs did not show clear temporal trends at almost all plots, with the exception of TD-S (5–10 cm and 10–15 cm), OT-S (10–15 cm and 15–20 cm), and OT-Q (5–10 cm and 15–20 cm), where increasing trends were observed (Fig. 3). In particular, after applying the decay correction to March 11, increasing trends were observed in deeper soil layers at some plots, which suggests that 137Cs continued to migrate very slowly to deeper soil layers during the five years, although this migration was very minor compared to the rapid migration during the first half year after the fallout.

Radiocesium inventories

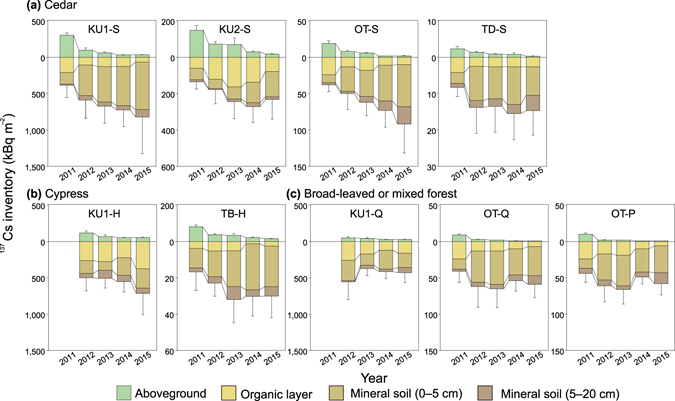

Figure 4 shows temporal changes in the 137Cs inventory in the aboveground compartments (needles/leaves, branches, bark, and wood), organic layer, and mineral soil layers at each study plot. The 137Cs (and 134Cs) inventory of each component is shown online in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3 of the supplementary information section.

Figure 4.

Time series of the 137Cs inventories in the aboveground compartments, organic layer, and mineral soil layers at each study plot. Error bars denote the SDs of aboveground and belowground 137Cs inventories.

The aboveground compartments retained the highest percentage of 137Cs in 2011 (18–52% of the total 137Cs inventory) and then decreased in subsequent years in each plot (to 1.0–7.0% in 2015; Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). This rapid decline in the 137Cs inventory of aboveground compartments was mainly due to decreases in the needle and branch inventories, which retained more than 80% of the 137Cs initially deposited in the aboveground compartments in 2011 (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The 137Cs inventory in wood accounted for less than 1% of the total 137Cs inventory at all the plots except TB-H (<2%) in 2015 (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The proportion of the aboveground 137Cs inventory was higher at sites KU1, KU2, and TB (4–7% in 2015) than at sites OT and TD (1–2%) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The decrease in the aboveground 137Cs inventory was most significant from 2011 to 2012 (Fig. 4). In particular, the 137Cs inventory in the aboveground compartments decreased to 4% in 2012 at the mixed forest plots (OT-Q and OT-P), representing a more significant decrease than the decrease to 9–29% at the Japanese cedar and hinoki cypress plots (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The faster rate of decline observed at the mixed forest plots was mainly attributed to the significant decline in the 137Cs concentration in the Japanese red pine needles (Fig. 2). By contrast, the 137Cs inventory in the aboveground compartments remained approximately stable at the broad-leaved forest plot (KU1-Q), where the proportion of the 137Cs inventory in leaves remained consistently low (0.2–0.5% of the total 137Cs inventory; Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Consequently, the 137Cs percentage in the aboveground compartments was comparable after 2013 among the different forest types at KU1 (Fig. 4).

The 137Cs inventory in the organic layer was highest in 2011 (16–49% of the total 137Cs inventory) and then decreased over time at most plots (to 8–35% in 2015 at KU1-S, OT-S, TD-S, TB-H, KU1-Q, OT-Q, and OT-P; Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). However, the 137Cs inventory in the organic layer increased from 2011 to 2013 and then decreased at KU2-S (Fig. 4), where the 137Cs proportion in the aboveground compartments was highest among the plots in 2011 (52%; Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). At the Kawauchi site (KU1-H, KU1-Q, and KU2-S), higher 137Cs levels persisted in the organic layer (31–49% in 2015), in contrast to those at the other sites (8–17%) except KU1-S (8%) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Corresponding to the 137Cs decline in the aboveground compartments and organic layers, the annual 137Cs inventory in the mineral soil layers was lowest in 2011 (25–39%) and then drastically increased from 2011 to 2012 (64–75% in 2012) at KU1-S, OT-S, TD-S, OT-Q, and OT-P (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). Over the five years studied, mineral soils became the largest 137Cs reservoirs within the forests at these plots (81–89% in 2015) (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). To a depth of 20 cm, the majority of the 137Cs in mineral soils was stored in the 0–5 cm layer at all plots (65–91% of the 137Cs inventory in the mineral soil layers in 2015).

Discussion

Aboveground 137Cs

Our five-year monitoring data collected at plots with different contamination levels revealed the same exponential decreases in the 137Cs concentration in needles and branches at all coniferous plots (Fig. 2). Previous studies have shown that throughfall and litterfall sampled in various forest stands affected by Fukushima fallout are highly contaminated with radiocesium9–11 and that throughfall contributions to 137Cs transfer from aboveground to belowground were more significant than those of defoliation in the very early phase after the incident and then rapidly decreased9, 12. Therefore, the observed decreases in 137Cs in needles and branches were probably first mainly driven by rain; thereafter, defoliation played a major role in the decreases, and these processes similarly occurred at all plots overall.

Among the coniferous species, the effective ecological half-life of 137Cs in needles was the shortest for Japanese red pine compared to those of Japanese cedar and hinoki cypress. We inferred that Japanese red pine trees defoliated their needles that were initially contaminated at the time of Fukushima accident more rapidly than the other coniferous tree species because Japanese red pine trees have a shorter leaf longevity (2–3 years) than Japanese cedar and hinoki cypress (4–6 years)13, 14. For konara oak, because significant deposition resulting from the Fukushima accident occurred at a stage prior to leaf flushing, the deciduous leaves of konara oak were much less contaminated than other evergreen needles in the summer of 20117. In addition, the 137Cs concentration in the deciduous leaves did not change significantly over the five years, whereas the concentrations in other species exponentially decreased. Interestingly, as a result, the 137Cs concentration in deciduous leaves reached levels comparable to that in evergreen needles at the adjacent plot in the same site (KU1 and OT) after five years (Fig. 2).

Tree bark was less contaminated in the summer of 2011 than needles and branches at many plots (Fig. 2) likely because needles and branches were more exposed to radiocesium deposition than bark and because needles and branches are morphologically effective at intercepting deposition. However, our five-year monitoring study revealed that the 137Cs concentration in bark did not change considerably over the observation period at many plots. Bark mainly consists of inner bark (phloem) and outer bark. The outer bark, which was exposed to radiocesium deposition, would retain a considerable portion of radiocesium in the early phase15. Therefore, the longer residence time of 137Cs in the bark than in the needles and branches implies that both the turnover and wash-off rates in the outer bark are low compared to those in the needles and branches. Eventually, the concentration and inventory of bark 137Cs reached comparable levels to those of needle and branch 137Cs in 2015 (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

These unique behaviour of bark 137Cs have been reported in Chernobyl studies: The bark of an oak tree species (Q. petraea) in Bulgaria was found to be 2–4 times more contaminated with 137Cs than its leaves and branches 22 years after the Chernobyl accident16. In the 40-mm-thick bark of an oak tree species (Q. robur) in Romania, the outer 8-mm layer was found to be the most contaminated with 137Cs 27 years after the accident17. Alternatively, the 137Cs concentration in inner bark was higher than that in outer bark in Scots pines 12 years after the accident18. These differences in outer and inner bark 137Cs appear to be dependent on the species and/or environment, and careful follow-up research on bark contamination is therefore of particular importance to forest management.

Belowground 137Cs

The 137Cs concentration in the organic layers decreased exponentially with time at some plots, whereas that in the surface mineral soil layer increased (Fig. 3). These results indicate that 137Cs was transferred from the organic layer to the mineral soil layer, which was likely caused by washout by rain and litter decomposition19 over the five years. As an exception, the 137Cs inventory in the organic layer increased from 2011 to 2013 at KU2-S, where the 137Cs proportion in the aboveground compartments was highest over the five years compared to that at the other plots (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). As the amount of 137Cs retained by needles and bark was relatively high at KU2-S, this high interception resulted in the delayed migration of 137Cs from the aboveground compartments to the organic layer. This delayed migration explains the increasing 137Cs inventories from 2011 to 2013 and the decreasing inventories from 2013 to 2015 in the organic layer. Previous studies have reported that the thickness and volume of the organic (litter) layer affect the 137Cs retention capacity of the organic layer20, 21. We did not detect high retention within the thick organic layer (e.g., 1.4–2.8 cm at KU2-S and 1.6–2.1 cm at OT-S) (Table 1 and Fig. 4). However, the proportions of 137Cs retained in the organic layer to belowground compartments (organic layer and mineral soil) were relatively high at KU1-H, KU1-Q, and KU2-S in 2015. At these plots, the 137Cs proportions in aboveground compartments were high (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3), which may suggest that the amount of 137Cs in the organic layer was more closely controlled by inputs from aboveground trees rather than by the 137Cs retention capacity of the organic layer during the initial phase of radiocesium cycling after the fallout.

In the mineral soil layers, the most 137Cs was retained in the shallowest layer, as shown in previous reports21–23. The retention rate of the surface layer (the ratio of the 137Cs inventory in the 0–5 cm soil layer to that in all soil layers) did not show any temporal trends at any of the plots (data not shown). Matsunaga et al. (2013)24 reported that the vertical distribution of 137Cs in mineral soils did not change after the rainy season in the first year following the FDNPP accident. The 137Cs flux through the mineral soil layers decreased in the second year relative to level in the first year20, 25. Previous studies on the Chernobyl incident have reported that the 137Cs level in mineral soil decreased with increasing depth and that the distribution of 137Cs in mineral soils did not change drastically over time26. These findings suggest that the 137Cs distribution in the mineral soil layer was rapidly established within a half year after the fallout at Fukushima and that the mobility of 137Cs in the mineral soil layer quickly decreased, although 137Cs continues to migrate to deeper soil layers very slowly at some plots.

137Cs in wood

Time series variations of the 137Cs concentration in wood differed between tree species: The concentrations in Japanese red pine decreased, whereas those in konara oak increased (Fig. 2). Japanese cedar and hinoki cypress showed increasing trends or did not show significant trends (Fig. 2). Regarding the Chernobyl accident, oak trees exhibited stronger 137Cs absorption capacities than pine trees20, 27, in accordance with our results. Recent Fukushima studies have noted the relative importance of the foliar uptake of radiocesium and its translocation in the initial phases following deposition28–30. The radiocesium concentrations in internal tree tissues should be affected by many factors such as foliar uptake just after an accident, subsequent root uptake, dilution due to tree growth, radioactive decay, and defoliation. The relative biomass increment in woods was low at OT-Q (0.3% yr−1) and OT-P (0.8% yr−1) compared to that at other coniferous plots (2–9% yr−1; Supplementary Table S4). Therefore, the dilution of the 137Cs concentration in wood due to tree growth was almost negligibly small in the Japanese red pines and konara oaks in the present study. In addition, in the present study, the radioactive decay of 137Cs (−2.3% yr−1) did not affect the temporal trends in the 137Cs concentration in wood because the significance of the slope of the regression line did not change after decay correction to March 11, 2011 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Foliar uptake of 137Cs would have had little influence on the temporal trends in the 137Cs concentration in konara oak wood because the leaves had not been flushed at the time of the accident. Thus, the increasing trends in the 137Cs concentration in konara oak wood suggest that the 137Cs inflow exceeded the outflow due to defoliation during the five years after the accident. By contrast, the decreasing trend in Japanese red pine wood indicates that the 137Cs inflow was smaller than the outflow. The 137Cs inflow due to root uptake, however, can be affected by soil conditions such as moisture20 and potassium and ammonium contents26, and the outflow due to defoliation might be affected by the vitality and age of a tree. The different temporal trends observed in the Japanese cedar and hinoki cypress among the sites should be evaluated in further studies that include such pedological and physiological details.

Concluding remarks

In this paper, we reported temporal radiocesium changes after the FDNPP accident based on annual monitoring data of the radiocesium distributions in Fukushima forests of various types and with varying contamination levels from 2011 to 2015. Our multi-site, multi-species monitoring results revealed that the pattern of temporal radiocesium changes in the 9 forest plots was similar overall; however, changes in 137Cs in needles/leaves and wood differed among the tree species. These suggest that our data are very useful for understanding and quantifying radiocesium migration in various forests in Fukushima and for developing a predictive model. The distributions of radiocesium in forests will continue to change until steady state is reached, and further monitoring will undoubtedly be required in the future.

Methods

Sites

The study was conducted at five sites with different radiocesium deposition levels: site KU1 on Mt. Otsupe in Kawauchi Village (26–27 km from the FDNPP, 470–630 kBq m−2 of 137Cs deposition as of June 2012, as evaluated by airborne monitoring31), site KU2 at Kanayama in Kawauchi Village (28 km, 160 kBq m−2), site OT in Otama Village (66 km, 41–44 kBq m−2), and site TD in Tadami Town (134 km, 10 kBq m−2) in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, as well as site TB on Mt. Tsukuba in Ishioka City (160 km, 33 kBq m−2) in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan (Table 1 and Fig. 1). From August–September 2011, study plots at KU1-S, OT-S, and TD-S were established in Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica; common name: sugi) plantations. Plot OT-Q was located in a secondary forest where deciduous oak (Quercus serrata; common name: konara) is as abundant as pine, and plot OT-P was located in a secondary forest where Japanese red pine (Pinus densiflora; common name: akamatsu) dominates, along with some broad-leaved tree species7. In addition, KU2-S was established in a Japanese cedar plantation in November 2011; TB-H and KU1-H were established in a hinoki cypress (Chamaecyparis obtusa; common name: hinoki) plantation in February 2012 and August 2012, respectively; and KU1-Q was established in a secondary forest of DBL trees in August 2012. The topographic features, plot areas, initial deposition levels, stand ages as of 2011, stand densities and diameters at breast height (DBH), aboveground biomass levels, and forest floor surface densities for each study plot are shown in Table 1. Steep slopes were found at KU1-S, OT-S, TD-S, and TB-H. Soils were classified as Andosols or brown forest soils (KU1-S, OT-S, OT-Q, and OT-P) and as Inceptisols or brown forest soils (TD-S)23, 32. The dry mass of the organic layer (kg m−2) was highest at KU2-S. The annual mean temperature was 10.7 °C, 15.0 °C, 10.2 °C, and 14.4 °C, and rainfall levels reached 1,574 mm, 1,176 mm, 2,615 mm, and 1,435 mm in 2011–2015 at nearby meteorological stations of KU, OT, TD, and TB (Supplementary Table S5) (Japan Meteorological Agency)33.

Field measurements and sampling

Field measurements and sampling of needles/leaves, branches, bark, wood, litter, and mineral soils were basically conducted from August to September of each year (Figs 2 and 3). At each study plot, tree monitoring had been carried out annually to determine the species, diameter growth, and mortality and to recruit all individual trees with a DBH of >10 cm. Tree heights were estimated from the observed relationship between tree height (approximately 20 randomly selected trees per plot) and DBH. The biomass values of needles/leaves and branches were estimated based on DBH allometric equations for dominant species34. Biomass values of bark and wood were estimated from the total stem volume, which was calculated from the DBH and tree height34 and from the mean volume ratio and specific density of wood and bark samples35.

Three trees of differing diameters (small, medium, and large) were felled near the study plot of each stand every year: Japanese cedar at KU1-S, KU2-S, OT-S, and TD-S; konara oak and Japanese red pine at OT-Q and OT-P; konara oak near KU1-Q; and hinoki cypress near KU1-H and TB-H. Needles/leaves and branches were sampled from different parts of each tree crown. These samples were homogenized and then oven-dried for 2–3 days at 75 °C. Bark and debarked wood disks were sampled from stems at approximately breast height, and disks were divided into sapwood and heartwood samples. Bark and wood samples taken in 2011 were oven-dried for over 2 days at 105 °C. From 2012, to facilitate drying, bark and wood samples were oven-dried for 2–3 days at 75 °C, and the dry masses were converted at 105 °C using mean conversion factors (0.98 for bark and 0.99 for wood), which were experimentally determined for the four species.

Organic and mineral soil layer samples were collected at four points around three trees in 2011. After 2012, sampling subplots were established at 12 points in KU1-S, KU2-S, OT-S, OT-Q, OT-P, TD-S, and TB-H and at 6 points in KU1-H and KU1-Q, where the stand areas were relatively small. Samples of the organic layer accumulated on the forest floor were collected from a 25 × 25-cm quadrat. Soil layers were sampled at 5-cm intervals from 0 cm to a depth of 20 cm using a 475-mL cylinder (95-cm2 cross-sectional area × 5-cm depth). Details on the sampling method used are reported in Ikeda et al.36. Samples of the organic and surface soil layers (0–5 cm depth) were collected from each subplot. Deeper soil layers (5–10, 10–15, and 15–20 cm) below the organic and surface soil layers were sampled at 4 or 3 points in each plot. The organic and mineral soil layer samples were air-dried and then oven-dried for 24 h at 75 °C and 105 °C, respectively.

Radiocesium analysis

The concentrations of 137Cs and 134Cs in most samples from 2011 were determined using a gamma-ray spectrometer (GC2020-7500SL-2002CSL, Canberra, Meriden, USA). Further details on this method are reported in Kuroda et al.37, Fujii et al.23, and Komatsu et al.7. The 134Cs and 137Cs concentrations in all samples from 2012–2015 were determined using HPGe coaxial and P-type reverse coaxial detector systems (GEM20-70, GEM40P4-76, GEM-FX7025P4-ST, and GWL-120-15-LB-AWT, ORTEC, Oak Ridge, USA) and spectral analysis software (DS-P1001 Gamma Station, Seiko EG&G, Tokyo, Japan) in the Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute (FFPRI) laboratory. Measurement times were set to 1,800–86,400 s to obtain 137Cs concentrations with relative errors of <10%. When concentrations fell below the detection limit, the mean value and SD were determined via maximum likelihood estimation38. This procedure for processing data below the detection limit was also applied in the regression analysis. The radiocesium concentration was decay corrected to September 1 of each sampling year. The radiocesium concentration in wood was derived by weighting the mean radiocesium concentration of sapwood and heartwood by the biomass of sapwood and heartwood for each sample. The radiocesium inventory (Bq m−2) of each component was calculated by multiplying the mean radiocesium concentration per unit of dry mass (Bq kg−1) by the dry mass of each unit area (kg m−2). Further information on the stand-level radiocesium inventory calculations is included in Komatsu et al.7. We confirmed that the 134Cs/137Cs ratios of the samples were very stable after considering their half-lives; hence, we hereafter focus only on the 137Cs results in this paper (see the supplementary information section for 134Cs data).

The effective ecological half-lives (T eff) denoting the reduction of 137Cs activity concentration in the leaves and branches were calculated with the follow equation:

| 1 |

where C(0) is the initial concentration (Bq kg−1), sampled in 2011 or 2012 according to the sampled plots (Table 1) and C(t) is the 137Cs concentration (Bq kg−1) after time t (yr). Both C(t) and C(0) are decay corrected to September 1 of each sampling year. Note that the effective ecological half-life involves both the physical and ecological half-lives.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Kanto Regional Forest Office of the Forestry Agency, the village office of Kawauchi, and the local residents of Fukushima Prefecture for their cooperation. We also thank the many researchers and staff of the FFPRI for their assistance with field sampling, measurements, and sample analysis. Comments from anonymous reviewers were valuable for improving our early draft. This study was supported through research grant #201126 of the FFPRI and the Forestry Agency of Japan.

Author Contributions

N.I. built the datasets and performed the analysis with help from M.K. and S.O., and N.I. prepared the manuscript with help from M.K., S.O., and S.H. While all the authors were involved in sampling, S.K. was responsible for soil sampling, and T.K. was responsible for biomass sampling. T.K., S.K., and T.T. conceived of and facilitated the project and monitoring component. All the authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08261-x

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Naohiro Imamura, Email: nimamura@ffpri.affrc.go.jp.

Masabumi Komatsu, Email: kopine@ffpri.affrc.go.jp.

Shinta Ohashi, Email: shinta.res@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Katata G, Ota M, Terada H, Chino M, Nagai H. Atmospheric discharge and dispersion of radionuclides during the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Part I: Source term estimation and local-scale atmospheric dispersion in early phase of the accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2012;109:103–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terada H, Katata G, Chino M, Nagai H. Atmospheric discharge and dispersion of radionuclides during the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Part II: verification of the source term and analysis of regional-scale atmospheric dispersion. J. Environ. Radioact. 2012;112:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto, S., Ugawa, S., Nanko, K. & Shichi, K. The total amounts of radioactively contaminated materials in forests in Fukushima, Japan. Sci. Rep. 2, doi:10.1038/srep00416 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Forestry agency, Japan. Present state of forest resources (31 March, 2012)http://www.rinya.maff.go.jp/j/keikaku/genkyou/h24/index.html.

- 5.Koizumi A, et al. 137Cs trapped by biomass within 20 km of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:9612–9618. doi: 10.1021/es401422g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonze MA, Calmon P. Meta-analysis of radiocesium contamination data in Japanese forest trees over the period 2011–2013. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;601–602:301–316. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Komatsu M, et al. Characteristics of initial deposition and behavior of radiocesium in forest ecosystems of different locations and species affected by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016;161:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IAEA. Forest environment in Environmental consequences of the Chernobyl accident and their remediation: twenty years of experience/ report of the Chernobyl Forum Expert Group ‘Environment’ 41–47 (IAEA, 2006).

- 9.Teramage MT, Onda Y, Kato H, Gomi T. The role of litterfall in transferring Fukushima-derived radiocesium to a coniferous forest floor. Sci. Total Environ. 2014;490:435–439. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itoh Y, Imaya A, Kobayashi M. Initial radiocesium deposition on forest ecosystems surrounding the Tokyo metropolitan area due to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Hydrol. Res. Lett. 2015;9:1–7. doi: 10.3178/hrl.9.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Endo I, et al. Estimation of radioactive 137-cesium transportation by litterfall, stemflow and throughfall in the forests of Fukushima. J. Environ. Radioact. 2015;149:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2015.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato H, Onda Y, Hisadome K, Loffredo N, Kawamori A. Temporal changes in radiocesium deposition in various forest stands following the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2017;166:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kajimoto T, et al. Dynamics of radiocesium in forest ecosystems affected by the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. J. Japanese For. Soc. 2015;97:33–43. doi: 10.4005/jjfs.97.33. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kiyono Y, Akama A. Predicting annual trends in leaf replacement and 137Cs concentrations in Cryptomeria japonica var. japonica plantations with radioactive contamination from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station accident. Bull. FFPRI. 2016;15:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohashi S, Okada N, Tanaka A, Nakai W, Takano S. Radial and vertical distributions of radiocesium in tree stems of Pinus densiflora and Quercus serrata 1.5 y after the Fukushima nuclear disaster. J. Environ. Radioact. 2014;134:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhiyanski M, et al. Cesium-137 contamination of oak (Quercus petrae Liebl.) from sub-mediterranean zone in South Bulgaria. J. Environ. Radioact. 2010;101:864–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cosma C, Iurian A-R, Incze R, Kovacs T, Žunić ZS. The use of tree bark as long term biomonitor of 137Cs deposition. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016;153:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiry Y, Goor F, Riesen T. The true distribution and accumulation of radiocaesium in stem of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) J. Environ. Radioact. 2002;58:243–259. doi: 10.1016/S0265-931X(01)00068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakanishi T, Matsunaga T, Koarashi J, Atarashi-Andoh M. 137Cs vertical migration in a deciduous forest soil following the Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2014;128:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shcheglov, A. I., Tsvetnova, O. B. & Klyashtorin, A. L. In Biogeochemical migration of technogenic radionuclides in forest ecosystems (ed. Tikhomirov, F. A.) (Nauka, 2001).

- 21.Koarashi J, et al. Factors affecting vertical distribution of Fukushima accident-derived radiocesium in soil under different land-use conditions. Sci. Total Environ. 2012;431:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato H, Onda Y, Teramage M. Depth distribution of 137Cs, 134Cs, and 131I in soil profile after Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2012;111:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujii K, et al. Vertical migration of radiocesium and clay mineral composition in five forest soils contaminated by the Fukushima nuclear accident. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2014;60:751–764. doi: 10.1080/00380768.2014.926781. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsunaga T, et al. Comparison of the vertical distributions of Fukushima nuclear accident radiocesium in soil before and after the first rainy season, with physicochemical and mineralogical interpretations. Sci. Total Environ. 2013;447:301–314. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosén K, Öborn I, Lönsjö H. Migration of radiocaesium in Swedish soil profiles after the Chernobyl accident, 1987−1995. J. Environ. Radioact. 1999;46:45–66. doi: 10.1016/S0265-931X(99)00040-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konopleva I, Klemt E, Konoplev A, Zibold G. Migration and bioavailability of 137Cs in forest soil of southern Germany. J. Environ. Radioact. 2009;100:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ipatyev V, Bulavik I, Baginsky V, Goncharenko G, Dvornik A. Forest and Chernobyl: forest ecosystems after the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident: 1986–1994. J. Environ. Radioact. 1999;42:9–38. doi: 10.1016/S0265-931X(98)00042-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masumori M, Nogawa N, Sugiura S, Tange T. Radiocesium in stem, branch and leaf of Cryptomeria japonica and Pinus densiflora trees: Cases of forests in Minamisoma in 2012 and 2013. J. Japanese For. Soc. 2015;97:51–56. doi: 10.4005/jjfs.97.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nishikiori T, et al. Uptake and translocation of radiocesium in cedar leaves following the Fukushima nuclear accident. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;502:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thiry Y, Garcia-Sanchez L, Hurtevent P. Experimental quantification of radiocesium recycling in a coniferous tree after aerial contamination: Field loss dynamics, translocation and final partitioning. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016;161:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan. Extension Site of Distribution Map of Radiation Dose, etc.,/GSI Maps http://ramap.jmc.or.jp/map/eng/.

- 32.Kaneko S, Ikeda S, Akama A, Miura S, Takahashi M. Soil physicochemical properties of experimental sites in forests contaminated by radioactive materials due to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Japanese J. For. Environ. 2013;55:75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Japan Meteorological Agency. http://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/index.php.

- 34.Kajimoto T, et al. Methods for assessing the spatial distribution and dynamics of radiocesium in tree components in forest ecosystems. Bull. FFPRI. 2014;13:113–136. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hosoda K, Mitsuda Y, Iehara T. Differences between the present stem volume tables and the values of the volume equations, and their correction. Japanese J. For. Plan. 2010;44:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikeda S, Kaneko S, Akama A, Takahashi M. Methods for assessing the spatial distribution and dynamics of radiocesium in forest soils. Bull. FFPRI. 2014;13:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuroda K, Kagawa A, Tonosaki M. Radiocesium concentrations in the bark, sapwood and heartwood of three tree species collected at Fukushima forests half a year after the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear accident. J. Environ. Radioact. 2013;122:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvrad.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helsel, D. R. Computing Summary Statistics and Totals in Statistics for Censored Environmental Data Using Minitab and R 62–98 (John Wiley & Sons, 2012).

- 39.Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI). GSI Tiles (elevation) http://maps.gsi. o.jp/#5/35.362222/138.731389/&base=std&ls=std%7Crelief&disp=11&lcd=relief&vs=c1j0l0u0f0&d=vl.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.