Abstract

AIM

To describe the imaging features of serous neoplasms of the pancreas using ultrasound, endoscopic ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging.

METHODS

This multicenter international collaboration enhances a literature review to date, reporting features of 287 histologically confirmed cases of serous pancreatic cystic neoplasms (SPNs).

RESULTS

Female predominance is seen with most SPNs presenting asymptomatically in the 5th through 7th decade. Mean lesion size was 38.7 mm, 98% were single, 44.2% cystic, 46% mixed cystic and solid, and 94% hypoechoic on B-mode ultrasound. Vascular patterns and contrast-enhancement profiles are described as hypervascular and hyperenhancing.

CONCLUSION

The described ultrasound features can aid differentiation of SPN from other neoplastic lesions under most circumstances.

Keywords: Guideline, Cancer, Ultrasound, Endoscopic ultrasound, Elastography

Core tip: Serous pancreatic cystic neoplasms are infrequent neoplasms of the pancreas. Ultrasound features including single cystic or mixed cystic and solid hypoechoic lesions, hypervascular and hyperenhancing profiles as described can aid differentiation from other neoplastic lesions under most circumstances.

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is the most common malignancy of the pancreas, accounting for about 90% of malignant pancreatic neoplasms. The most important imaging diagnosis to differentiate from PDAC are neuroendocrine tumours[1,2]. Most pancreatic cystic neoplasms are mucin producing including intraductal pancreatic mucinous neoplasia (IPMN) and mucinous cystic neoplasia (MCN)[3]. Other important pancreatic lesions to differentiate include metastases (e.g., of renal cell cancer), lymphoma and ectopic spleen. Comparatively less is known about serous pancreatic neoplasia (SPN) which is a rare (less than 1%-2% of pancreatic neoplasia) and predominantly cystic appearing tumor of the pancreas. Critically SPN is considered benign in comparison to the majority of other common cystic tumors and all solid tumors of the pancreas. SPN has been previously termed serous pancreatic cystic neoplasia and serous pancreatic cystadenoma[4]. Approximately 75% of SPNs are found in women at an average age of 50-60 years, however SPN may also be found in much younger patients[5]. Typically located in the body-tail of the pancreas and solitary, the majority are detected incidentally[4,6-8]. In the largest series published to date (n = 2622), 61% of patients were asymptomatic and 27% reported non-specific abdominal complaints, whilst only 9% presented with pancreatobiliary symptoms, and 9% with other symptoms[5].

Histopathologically, SPNs are cyst-forming epithelial neoplasms composed of cuboidal, glycogen-rich, epithelial cells, without cellular atypia. The cyst content is defined as “clear watery”. SPNs lack the genetic alterations typical of PDAC, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas (MCN and IPMN). Rather, they are characterized by molecular alterations of the von-Hippel-Lindau (VHL) gene and overexpression of vascular endothelial factor (VEGF), glucose transporter 1, and other markers of clear-cell tumorogenesis (HIF1-α, CAIX)[9]. VHL patients have a high prevalence of pancreatic lesions (unclassified benign cysts, neuroendocrine tumors, SPNs) and often multiple tumors in the gland. A systematic review found SPN in 11% of VHL patients[10]. However, the majority of SPNs are sporadic.

Most serous neoplasms are benign and defined as serous cystadenomas (SCAs). More aggressive subtypes occur, demonstrated in a series of 257 resected SCAs; 5.1% of SPNs were locally aggressive, with invasion of surrounding structures or vasculature or direct extension into peripancreatic lymph nodes, while 0.8% were frankly malignant, given the presence of metastases[5]. Another series of 193 SPNs reported infiltration of adjacent organs and structures in 3% of cases, but called into question the term “malignancy” for cases of very large SPNs[11]. Rare cases of synchronous or metachronous hepatic SPNs may represent multifocal occurrence rather than metastatic spread[9]. Frankly malignant behavior with metastases seems to be very rare. In a multinational study of 2622 patients with SPNs, only 3 serous cystadenocarcinomas (SCACs) were recorded (0.1%)[8]. Therefore, SCAC is represented predominantly by a few sporadic case reports in the recent literature. Follow-up studies have not demonstrated proof of an adenoma-carcinoma sequence in SPN[8,9,11-15].

The growth rate of SPNs is variably reported. In the largest series (n = 2622) it was found to be only 4 mm/year, and size was stable or decreased in as many as 63% of patients[8]. This was supported by another series (n = 214), where the doubling time was estimated at approximately 12 years, and was independent of tumour size[14]. In contrast, in another case series (n = 106) growth rate was reported to vary by tumor size, with the fastest growth (20 mm/year) observed in tumors ≥ 40 mm, compared to tumors < 40 mm (increasing 12 mm/year)[16]. Finally, a fourth series (n = 145) found the fastest growth 7-10 years after diagnosis (60 mm/year) compared to the first 7 years (10 mm/year). Oligocystic or macrocystic appearance, a history of other tumors, and patient age were all significant predictors of more rapid tumor growth[13].

Diagnosis of SPN primarily is based on imaging [computed tomography (CT); magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); ultrasound (US); endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)]. The classical microcystic SPN consists of innumerable very small cysts separated by thin, vessel-containing fibrous septae. Cysts may be microscopic or measure up to 10 mm. These features cause a honeycomb or sponge-like appearance with hypervascularity and distinct, sometimes lobulated, margins. Pertinent negatives include communication with the pancreatic duct, vascularized mural nodules, and a hypervascular capsule on contrast-enhanced imaging, whilst a central scar is visible in a third of cases and may contain calcifications[17-25]. Pitfalls may arise from several factors: the macro- and oligo-cystic types of SPN can appear similar to pseudocysts or MCN. Rarely the solid form of SPN may be confused with other hypervascular well-circumscribed pancreatic tumors, in particular neuroendocrine tumors and solid pseudopapillary neoplasms[18,19,26-28]. In contrast to the mentioned reports, an atypical appearance on CT was found in 61.1% of cases in a study of 72 confirmed SPNs[28].

A correct diagnosis of SPN is challenging. The pre-operative diagnosis was wrong in 63% of resected cases in a Japanese series[12], and in a large multinational study the indication for surgery was an uncertainty of diagnosis in 60% of cases[8]. To date, no large series describing typical and atypical US- and EUS-features of SPNs has been reported.

The aim of this retrospective study was to describe the imaging features of serous neoplasms of the pancreas using US, EUS, CT and MRI. The frequency of atypical imaging aspects by different imaging modalities will be estimated and the most common atypical features will be reported, particularly of US which is often the initial imaging modality employed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

An international multicenter retrospective data collection of 287 histologically confirmed cases of SPNs was performed. The cohort was not uniform according to the resection criteria. No other exclusion criteria have been defined.

Examination technique

Conventional ultrasound and contrast enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) were performed in all patients with one of six ultrasound systems: Philips iU22 unit (Philips Bothell, WA, United States; C5-1 convex array probes, 1-5 MHz), or LOGIQ E9 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, United States; C1-5 convex array probes, 1-5 MHz) or Hitachi (Hi vision EUB-6500, Preirus, Ascendus; C715 convex array probes, 1-5 MHz), or SIEMENS (Acuson Sequoia or S2000), or Toshiba (Aplio platinum 500; Aplio CV, convex array probes 3-6 MHz). CEUS was performed using contrast harmonic real-time imaging at a low MI 0.05-0.30. The ultrasound contrast agent Sonovue was used at a dose of 1.5-2.4 mL, immediately followed by an injection of 10 mL sodium chloride solution. Images were recorded for 3 min after contrast agent injection.

Contrast enhanced EUS was performed using longitudinal echoendoscopes EG-3870 UTK and Hitachi platforms (Hitachi HI vision EUB-6500, Hitachi Preirus, Hitachi Ascendus)[29-32].

Imaging Evaluation (TUS, EUS, CEUS, ceEUS)

After identification of the pancreatic lesion by conventional B-mode US or EUS, contrast enhanced imaging was immediately performed. All examinations were interpreted according to the 2011 EFSUMB guidelines[1]. CEUS features of pancreatic lesions were compared to the surrounding normal pancreatic parenchyma.

Final diagnoses, treatment and clinical follow up

Most patients (n = 249, 86.7%) were diagnosed as SPNs by post-operative histopathology. 31 (10.8%) cases were confirmed by EUS FNA and 7 (2.5%) by transabdominal (percutanous) ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy (18-gauge 20-cm single-use biopsy needles; Temno, Germany, or BioPince, Pflugbeil, Germany). Clinical follow-up for a minimum of 12 mo was established for all patients with SPN diagnosed by biopsy. Additional information on outcome data was not requested.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical parameters between the groups. Continuous parameters were presented as the mean ± SD, and Student’s t test was used. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Epidemiology

The average age of included patients was 57.3 ± 14.2 years (18-85 years). Fifty-eight patients were male and 229 were female (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of serous pancreatic neoplasia patients

| Characteristic | SPN patients (n = 287) |

| Age (yr) | |

| mean ± SD | 57.3 ± 14.2 |

| Range | 18-85 |

| Female/Male | 229/58 |

| Symptoms | |

| Pancreatitis | 5 |

| Weight loss | 9 |

| Anemia | 1 |

| Incidental finding | 272 |

| Histological results | |

| Surgery | 249 |

| EUS FNA (22G) | 31 |

| TUS-Bx (18 G) | 7 |

SPN: Serous pancreatic neoplasia; EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; FNA: Fine needle aspiration; TUS-Bx: Transabdominal biopsy.

Conventional ultrasound

On conventional B mode ultrasound (BMUS) most SPN lesions (n = 113, 39.3%) were detected in the head/neck of the pancreas. Most SPN lesions (97.9%) were single, though 6 (2.1%) patients had multiple lesions, and most lesions (97.9%) were hypoechoic on BMUS. With colour Doppler imaging (CDI), macrovessels were detected in 20.6% of lesions, among which the typical “spoke wheel” appearance was identified in 35.6% of lesions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Conventional B mode ultrasound findings of serous pancreatic neoplasia n (%)

| Characteristic | SPN lesions (n = 287) |

| Location | |

| Head/neck | 113 (39.3) |

| Body | 89 (31.0) |

| Tail | 85 (29.6) |

| Size of lesions (mm) | |

| mean ± SD | 38.7 ± 26.2 |

| Range | 4-160 |

| Number of lesions | |

| Single | 281 (97.9) |

| Multiple | 6 (2.1) |

| B mode aspect | |

| Microcystic mix | 31 (10.8) |

| Macrocystic | 96 (33.4) |

| Solid and cystic | 133 (46.3) |

| Solid | 27 (9.4) |

| B mode echogenicity | |

| Anechoic | 10 (3.4) |

| Hypoechoic | 271 (94.4) |

| Hyperechoic | 6 (2.2) |

| CDI vessel detectable | |

| Avascular | 228 (79.4) |

| Macrovessels detectable | 59 (20.6) |

| CDI vascular pattern (n = 59 with macrovessels) | |

| Central artery | 26 (44.1) |

| Typical spoke wheel appearance | 21 (35.6) |

| No specifics | 12 (20.3) |

SPN: Serous pancreatic neoplasia; CDI: Color Doppler imaging.

CEUS

Transabdominal CEUS was performed in 173 (60.3%) lesions. After contrast agent injection, most SPN lesions displayed hyper- (36.5%) or isoenhancement (61.8%) in the arterial phase. During the late phase, most SPN lesions were hyper-enchancing (22.5%) or iso-enhancing (74.9%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Contrast enhanced ultrasound imaging features of serous pancreatic neoplasia lesions n (%)

| Characteristic | SPN lesions (n = 173) |

| Arterial phase | |

| Hyperenhancement | 63 (36.5) |

| Isoenhancement | 107 (61.8) |

| Hypoenhancement | 3 (1.7) |

| Late phase | |

| Hyperenhancement | 39 (22.5) |

| Isoenhancement | 129 (74.6) |

| Hypoenhancement | 5 (2.9) |

CEUS: Contrast enhanced ultrasound; SPN: Serous pancreatic neoplasia.

EUS and contrast enhanced EUS

EUS was performed in 61 patients diagnosed with SPN. Using CDI, macrovessels were detected in all 61 cases. Contrast enhanced endoscopic ultrasound (CE-EUS) was performed in 54 SPN lesions, demonstrating hyper-enhancement in all cases (Table 4).

Table 4.

Endoscopic ultrasound and contrast enhanced endoscopic ultrasound imaging features of serous pancreatic neoplasia lesions n (%)

| Characteristic | SPN lesions (n = 61) |

| EUS | |

| Anechoic | 2 (3.3) |

| Hypoechoic | 56 (91.8) |

| Isoechoic | 3 (4.9) |

| EUS-CDI vessel detectable | |

| Avascular | 0 |

| Macrovessels detectable | 61 (100) |

| EUS-CDI vascular pattern (n = 61) | |

| Central artery | 26 (42.6) |

| Typical spoke wheel appearance | 15 (24.6) |

| No specifics | 20 (32.8) |

| CE-EUS (n = 54) | |

| Hyperenhancement | 54 (100) |

| Isoenhancement | 0 |

| Hypoenhancement | 0 |

| Final EUS-Diagnosis | |

| “Eyecatcher” | 49 (80.3) |

| Typical SCA | 5 (8.2) |

| Unclear macrocyst | 6 (9.8) |

EUS: Endoscopic ultrasound; EUS-CDI: Endoscopic ultrasound color Doppler Imaging; CE-EUS: Contrast enhanced endoscopic ultrasound; SPN: Serous pancreatic neoplasia; SCA: Serous cystadenoma.

DISCUSSION

SPNs are less frequent than common pancreatic tumors such as solid ductal adenocarcinoma and cystic IPMN but recent estimates suggest SCAs represent about 20% of all cystic pancreatic lesions[33,34]. SPN typically present as a solitary multilocular microcystic lesion with a honeycomb architecture due to the presence of multiple microcysts. Thin walls and multiple thin septa orient toward the centre/scar of the lesion, without communication with the main pancreatic duct. In typical cases an imaging diagnosis can be made confidently. However, atypical presentations are commonly encountered in everyday clinical practice. Specifically, extremely microcystic SPNs are considered rare, resembling a solid lesion in conventional US, but in fact a solid component was seen in the 55.7% of cases in our multicentre study. After contrast administration, these solid SPNs may resemble hypervascular solid lesions with homogeneous hyperenhancement, making differentiation from neuroendocrine neoplasms as difficult as it is crucial[35,36]. MRI may reveal a lesion’s true cystic nature[37]. The macrocystic variant must be differentiated from other macrocystic pancreatic lesions, such as pseudocyst, mucinous cystic neoplasms, side-branch and mixed type IPMNs, solid tumors (either adenocarcinomas or neuroendocrine) with cystic degeneration, and lymphangiomas[38-40].

Epidemiology

The mostly asymptomatic SPN is often a solitary lesion with multilocular cysts predominantly in the corpus and tail of the pancreas. SPNs are usually diagnosed in females in the 5th to 7th decade (female to male ratio 2-3:1) but with improved imaging methods the neoplasia may be diagnosed much earlier[3]. Multiple lesions, including involvement of the entire organ, have been observed in patients with Von Hippel-Lindau disease[6,7,10,23]. SPNs may present up to 20% of cystic pancreatic lesions[3,33,41].

Clinical symptoms

Sporadic and benign SPNs are most often an incidental finding without symptoms; jaundice is particularly uncommon. In our series only 5.2% of SPNs presented with symptoms. During the course of the disease, symptoms may be caused by growth of the lesion. The main pancreatic duct and or common bile duct may become entrapped in the lesion, especially if large in dimension. The reported growth rate has been estimated at 4 mm per year[39].

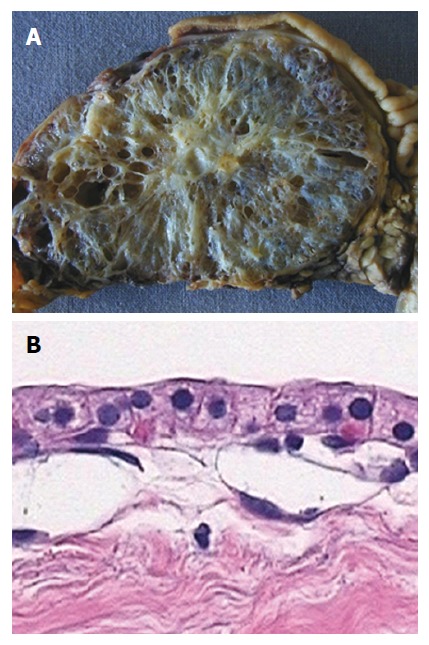

Pathology

The solitary well demarcated and multicystic SPN is a multilobular cyst forming epithelial neoplasia with a somewhat “honeycomb” architecture (Figure 1) without communication with the pancreatic duct.

Figure 1.

Macro- and micro-pathology (histology, cytology) of microcystic pancreatic adenoma. A: Typical microcystic appearance of serous cystadenoma with “honeycomb” architecture, and central scar with small calcification; B: Histology demonstrates the typical single layer of clear cuboidal epithelial cells lining the cysts.

Histologically, monostratified cuboidal, glycogen rich epithelial cells typically without mitoses are observed. Centrally located fibrous tissue (a so called “scar”) with or without calcifications can be found, similar to focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver; therefore the lesion has been referred to as “FNH of the pancreas”[4]. SPNs are typically hypervascular lesions, where septa are characterized by abundant subepithelial micro- and macro-vessels[6,7].

Size of single cysts

According to the size of the cysts, SPNs can be classified as real solid lesions (< 5%), pseudo-solid SPNs (cysts only detectable by microscopic evaluation), microcystic (< 10 mm), oligocystic (< 20 mm), and macrocystic appearance (30%)[4,6,7,42,43]. The cystic appearance can be described by thin multiple septa oriented toward the center of the lesion. Mixed forms (microcystic and macrocystic) are typical in large SPNs. Macrocystic giant SPNs are more commonly located in the pancreatic head, and a male preponderance was observed. The macrocystic variant may be indistinguishable from other macrocystic tumors of the pancreas[44].

Malignant transformation

SPN is typically a benign neoplasia but in a series of 257 resected SPNs, local expansion (5.1%) and malignant transformation with metastases (0.8%) have been described[5]. Therefore, follow-up is recommended by means of ultrasound or MRI. Surgical treatment is recommended only for symptomatic patients or patients with growing lesions, usually larger than 4 cm[16].

Imaging

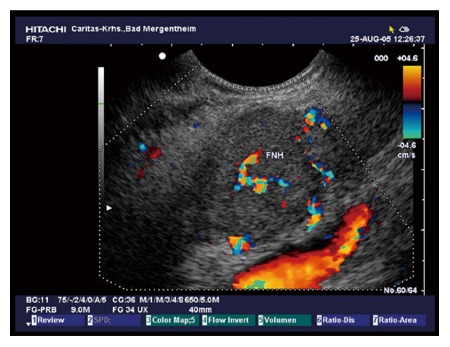

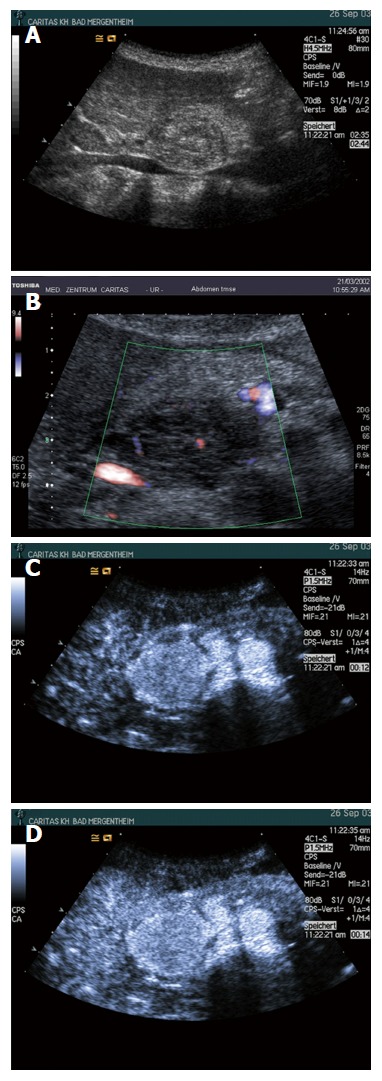

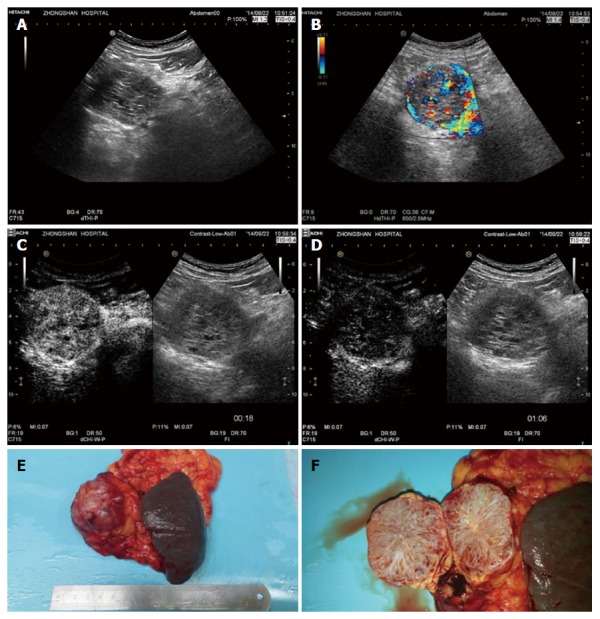

Ultrasound: Sonographically, SPN is a typically lobular cyst forming isoechoic neoplasia with centrally oriented thin walls (thin septae) without communication with the main pancreatic duct. A central hypoechoic spot (central fibrovascular scar) is characteristic[3,45-47]. In the case of depictable cysts the content is anechoic. SPNs are typically hypervascular lesions since the septa are composed by abundant subepithelial micro- and macro-vessels[6,7] (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Typical microcystic serous pancreatic neoplasia using colour Doppler imaging. Note the centrally located artery.

Figure 3.

Typical microcystic serous pancreatic neoplasia using B-mode (A), colour Doppler imaging (B), and contrast enhanced ultrasound (C and D). Note the centrally located artery and the typical hyperenhancement.

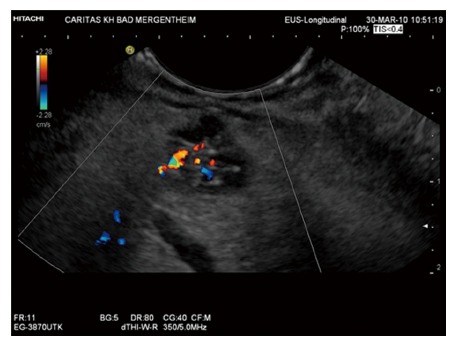

As has been shown in a prospective study (n = 12) using CE-EUS, hypervascularity, sharp delineation, fibrotic strands and typical vessel architecture are the predominant features of serous microcystic adenoma[47] (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Typical oligocystic serous pancreatic neoplasia using endoscopic ultrasound.

Figure 5.

Histopathologically proven serous microcystic serous pancreatic neoplasia. A: A solid-cystic lesion was detected in the head of pancreas with B-mode ultrasound; B: Multiple interlesional color flow signals were detected using colour Doppler imaging; C: Contrast enhanced ultrasound showed the lesion to hyperenhance in the arterial phase; D: Isoenhance in the late phase; E and F: Surgical pathology shows the typical honeycomb structure.

Solid SPNs may mimic neuroendocrine tumours, renal metastases, intrapancreatic accessory spleens and other hypervascular pancreatic tumours[35,36,45,48]. Solid and pseudosolid SPNs are typically hypervascular and, therefore, hyperenhancing using CEUS[45,48,49,50].

EUS: EUS is an accurate imaging modality to diagnose and exclude neoplasia of the pancreas[1,51-53]. The features are the same as described for conventional ultrasound[54]. SPN do not communicate with the main pancreatic duct but may show proximal duct dilatation due to compression, whereas IPMN usually showed distal or whole pancreatic duct dilatation[50,55]. CE-EUS has been proven to be of value for many indications[29-32,56-60]. In our study EUS was able to detect macrovessels and hypervascularity by CDI contrast-enhanced imaging in 100% of cases, whereas percutaneous US with CDI delineated macrovessels only in 20.6% of cases.

Endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration: Endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of SPN should target the largest cyst for fluid analysis[61,62]. The cyst fluid is watery (non-viscous) and colorless[63]. The cellularity is low with few cuboidal glycogen positive and mucin negative epithelial cells. CEA levels are usually but not always low (< 20 ng/mL). In the majority of cases, aspirated fluid will be hypocellular with few groups of bland cuboidal epithelial cells embedded in granular debris[64-67]. Round to cuboid serous epithelial cells with clear cytoplasma and small, round nuclei forming loose clusters or monolayered sheets are identified in only 20%-25% of cases[64,66,68]. Positive α-inhibin immunocytochemistry may enhance the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA in SPN[66]. Promising cyst fluid markers with high sensitivity and specificity for SPN include VEGF-A and a molecular assay for KRAS, GNAS and VHL mutations. In one study, VEGF-A was markedly elevated in SPN when compared to pseudocysts and mucinous neoplastic cysts[69,70]. The presence of KRAS and GNAS mutations is highly specific for IPMN and is never observed in SPN, whereas VHL deletions are found in almost all SPN[69,71-74].

Core biopsy: In solid and pseudosolid lesion we prefer histological evaluation which allows definite diagnosis[51,52,75].

MRI: The MRI features of SPNs are also represented by a typical lobular “honeycomb” shaped contour and architecture with thin walls less than 2 mm, in contrast to other cystic neoplasia of the pancreas. SPNs are homogeneously hypointense on T1-weighted MRI sequences. The cystic nature of the lesion can be easly demonstrated by a typical hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images. The hyperintense cysts are surrounded by hypointense septa and sometimes by a hypointense (pathognomonic) central scar. The central scar is a less sensitive (15%) but specific sign of SPN[39,45,76-79].

In contrast to EUS, the individual vessels cannot be displayed but contrast enhanced MRI using gadolinium chelates also reveal the hypervascular nature by diffuse hyperenhancement in pseudosolid SPN However also in pseudosolid SPN, MRI remains highly accurate in showing the cystic nature of the lesion on T2-weighted images[50]. The macrocystic types present features similar to other macrocystic tumors of the pancreas, but the lobulated contours, together with the absence of wall enhancement and wall thickness less than 2 mm, should suggest the correct diagnosis[39,46,76,79].

CT: CT is sometimes helpful for detection of SPN but should in general not be used for the evaluation and differential diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesions. CT might be helpful in the visualization of a centrally located calcified scar. SPN may mimic a hypervascular lesion[17,39,46].

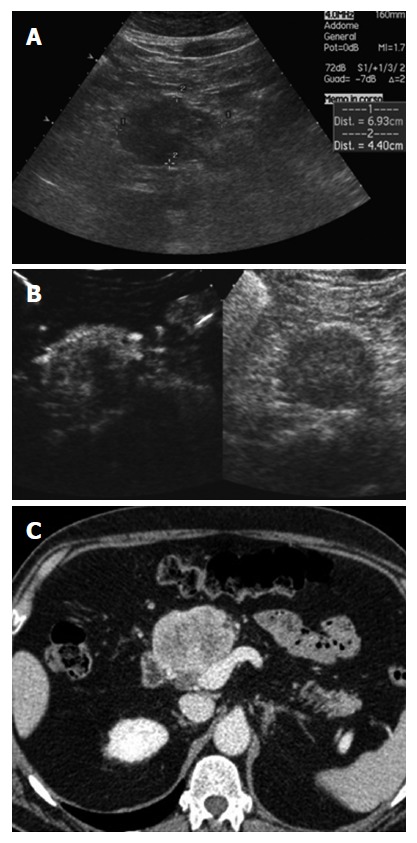

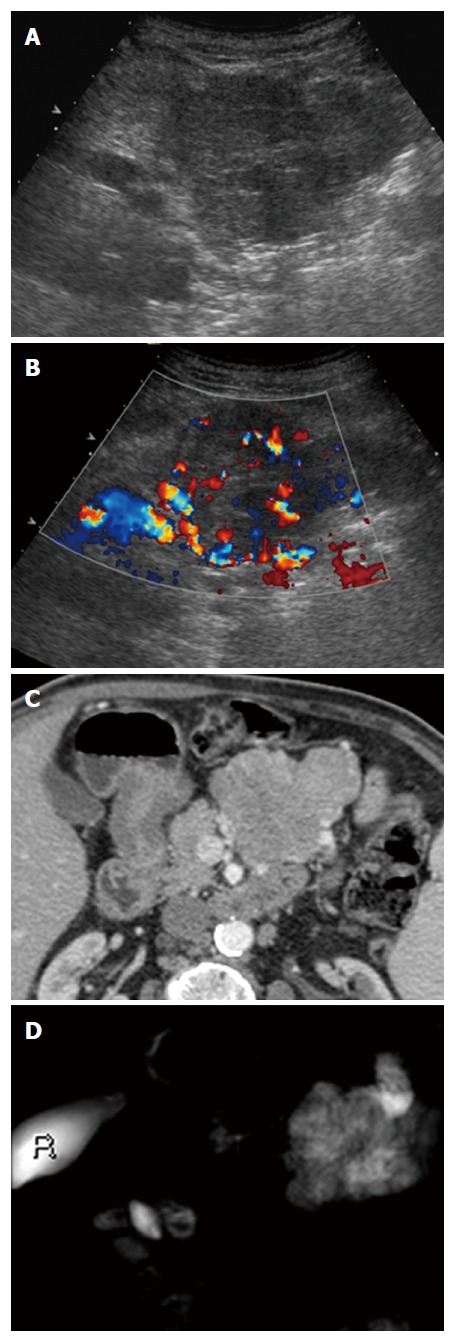

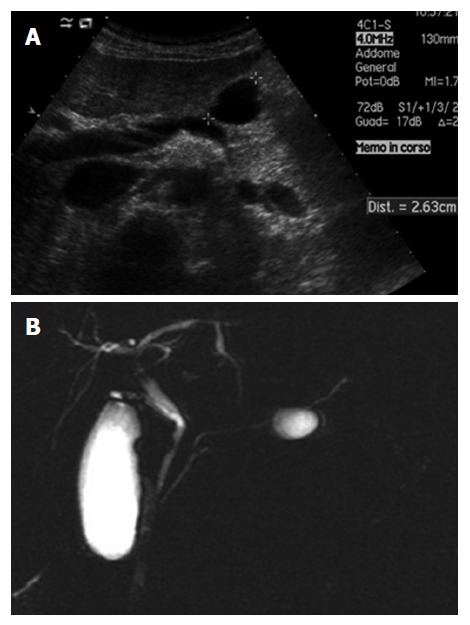

Differential diagnosis

The presence of a unilocular lobulated cyst located in the pancreatic head with anechoic fluid and wall thickness less than 2 mm are indicative of SPN using all imaging methods and should be considered as a unilocular macrocystic SCA, until otherwise proven (Figures 6, 7 and 8)[80].

Figure 6.

Pseudo-solid serous pancreatic neoplasia, histologically demonstrated to have a microcystic structure. A: B-mode ultrasound shows a solid hypoecoic mass in the neck of the pancreas; B: Contrast enhanced ultrasound shows the lesion to hyperenhance with a hypoechoic defect in the center; C: Computed tomography shows the lesion as solid and inhomogeneously hyperenhancing.

Figure 7.

Large pseudosolid serous pancreatic neoplasia. A: With B-mode ultrasound a huge mass is visible appearing solid and inhomogeneously hypoechoic; B: Doppler shows large arterial vessels within the mass; C: With Computed tomography the lesion appears pseudosolid with inhomogeneous slight enhancement; D: Magnetic resonance imaging clearly shows the cystic nature of the mass with microcystic appearance.

Figure 8.

Unilocular serous pancreatic neoplasia. A: B-mode ultrasound shows a cyst in the body of the pancreas; B: Magnetic resonance imaging shows small cystic lesions in the body of the pancreas not communicating with the main pancreatic duct.

Pancreatitis: A clinical history of pancreatitis is crucial for differentiating pseudocysts. Imaging findings of pancreatitis derived pseudocysts include signs of inflammation in the acute setting, calcifications, thin-walled duct dilation, pancreaticolithiasis, and atrophy and typical dilation of the pancreatic duct[39,51,81,82]. Solid SPNs are often misdiagnosed as chronic (focal) pancreatitis, which is important to know.

IPMN: Side branch or mixed type IPMN typically communicate with the pancreatic duct system and therefore can be differentiated from non-communicating SPN and MCN.

MCN: MCNs are also most common in females and they do not communicate with the pancreatic duct, but are usually located in the pancreatic tail[83]. The complex internal architecture of MCNs including septa and mural nodules can be best visualized using EUS and contrast enhanced EUS, but cMRI may be also helpful. In EUS-FNA, mucin and evaluation of the CEA level is important[39]. Peripherally located eggshell calcifications are a specific sign of MCN[84]. Other rare differential diagnoses include solid papillary neoplasia and lymphoepithelial cysts[39].

In conclusion, serous pancreatic neoplasms are an important differential of cystic, mixed and solid pancreatic lesions, with a generally benign course. This large series of histologically proven cases demonstrates the typical demographic, structural, vascular and contrast enhancement features which can distinguish these lesions from more common pathologies.

COMMENTS

Background

Serous pancreatic cystic neoplasms are infrequent neoplasms of the pancreas. A correct diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms (SPNs) is challenging. To date, no large series describing typical and atypical ultrasound (US)- and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) -features of SPNs have been reported.

Research frontiers

The aim of this retrospective study was to describe typical and atypical imaging features of serous neoplasms of the pancreas using US, EUS, computed tomography and MRI.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This multicenter international collaboration reports on imaging features in one of the largest series of 287 histologically confirmed cases of SPNs.

Applications

Ultrasound B-mode descriptors and contrast enhanced ultrasound describing the vascular pattern and enhancement features are helpful to differentiate SPN from other neoplastic cystic lesions.

Peer-review

Very interesting study about the serous pancreatic neoplasia.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Germany

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Data sharing statement: Each author gives permission to the graphic designers to alter the visual aspect of figures, tables, or graphs.

Peer-review started: March 7, 2017

First decision: April 11, 2017

Article in press: July 24, 2017

P- Reviewer: Lowenberg M, Reich K S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

References

- 1.Piscaglia F, Nolsøe C, Dietrich CF, Cosgrove DO, Gilja OH, Bachmann Nielsen M, Albrecht T, Barozzi L, Bertolotto M, Catalano O, et al. The EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Practice of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS): update 2011 on non-hepatic applications. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33:33–59. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D‘Onofrio M, Barbi E, Dietrich CF, Kitano M, Numata K, Sofuni A, Principe F, Gallotti A, Zamboni GA, Mucelli RP. Pancreatic multicenter ultrasound study (PAMUS) Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyer-Enke SA, Hocke M, Ignee A, Braden B, Dietrich CF. Contrast enhanced transabdominal ultrasound in the characterisation of pancreatic lesions with cystic appearance. JOP. 2010;11:427–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietrich CF, Barreiros AP, Jenssen C. Zystische, neuroendokrine und andere seltene Pankreastumoren. In: Dietrich CF, editor Endosonographie: Thieme Verlag, 2008: 287-331 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khashab MA, Shin EJ, Amateau S, Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, Cameron JL, Edil BH, Wolfgang CL, Schulick RD, et al. Tumor size and location correlate with behavior of pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1521–1526. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosmann FT. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer (2010) WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hruban RH, Pitman MB. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology (2007) Tumours of the pancreas. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jais B, Rebours V, Malleo G, Salvia R, Fontana M, Maggino L, Bassi C, Manfredi R, Moran R, Lennon AM, et al. Serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas: a multinational study of 2622 patients under the auspices of the International Association of Pancreatology and European Pancreatic Club (European Study Group on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas) Gut. 2016;65:305–312. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid MD, Choi H, Balci S, Akkas G, Adsay V. Serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: clinicopathologic and molecular characteristics. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2014;31:475–483. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlesworth M, Verbeke CS, Falk GA, Walsh M, Smith AM, Morris-Stiff G. Pancreatic lesions in von Hippel-Lindau disease? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1422–1428. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reid MD, Choi HJ, Memis B, Krasinskas AM, Jang KT, Akkas G, Maithel SK, Sarmiento JM, Kooby DA, Basturk O, et al. Serous Neoplasms of the Pancreas: A Clinicopathologic Analysis of 193 Cases and Literature Review With New Insights on Macrocystic and Solid Variants and Critical Reappraisal of So-called „Serous Cystadenocarcinoma“. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1597–1610. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimura W, Moriya T, Hirai I, Hanada K, Abe H, Yanagisawa A, Fukushima N, Ohike N, Shimizu M, Hatori T, et al. Multicenter study of serous cystic neoplasm of the Japan pancreas society. Pancreas. 2012;41:380–387. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31822a27db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malleo G, Bassi C, Rossini R, Manfredi R, Butturini G, Massignani M, Paini M, Pederzoli P, Salvia R. Growth pattern of serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: observational study with long-term magnetic resonance surveillance and recommendations for treatment. Gut. 2012;61:746–751. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Hayek KM, Brown N, O‘Rourke C, Falk G, Morris-Stiff G, Walsh RM. Rate of growth of pancreatic serous cystadenoma as an indication for resection. Surgery. 2013;154:794–800; discussion 800-802. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelaez-Luna MC, Moctezuma-Velázquez C, Hernández-Calleros J, Uscanga-Domínguez LF. Serous Cystadenomas Follow a Benign and Asymptomatic Course and Do Not Present a Significant Size Change During Follow-Up. Rev Invest Clin. 2015;67:344–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, Lauwers GY, Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumor growth rates and recommendations for treatment. Ann Surg. 2005;242:413–419; discussion 419-421. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179651.21193.2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Procacci C, Biasiutti C, Carbognin G, Accordini S, Bicego E, Guarise A, Spoto E, Andreis IA, De Marco R, Megibow AJ. Characterization of cystic tumors of the pancreas: CT accuracy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:906–912. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199911000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim HJ, Lee DH, Ko YT, Lim JW, Kim HC, Kim KW. CT of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas and mimicking masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:406–412. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee SE, Kwon Y, Jang JY, Kim YH, Hwang DW, Kim MA, Kim SH, Kim SW. The morphological classification of a serous cystic tumor (SCT) of the pancreas and evaluation of the preoperative diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2089–2095. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9959-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah AA, Sainani NI, Kambadakone AR, Shah ZK, Deshpande V, Hahn PF, Sahani DV. Predictive value of multi-detector computed tomography for accurate diagnosis of serous cystadenoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2739–2747. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen F, Liang JY, Zhao QY, Wang LY, Li J, Deng Z, Jiang TA. Differentiation of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms from serous cystadenomas of the pancreas using contrast-enhanced sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:449–455. doi: 10.7863/ultra.33.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu LC, Singhi AD, Hruban RH, Fishman EK. Characterization of pancreatic serous cystadenoma on dual-phase multidetector computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2014;38:258–263. doi: 10.1097/RCT.10.1097/RCT.0b013e3182ab1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graziani R, Mautone S, Vigo M, Manfredi R, Opocher G, Falconi M. Spectrum of magnetic resonance imaging findings in pancreatic and other abdominal manifestations of Von Hippel-Lindau disease in a series of 23 patients: a pictorial review. JOP. 2014;15:1–18. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manfredi R, Ventriglia A, Mantovani W, Mehrabi S, Boninsegna E, Zamboni G, Salvia R, Pozzi Mucelli R. Mucinous cystic neoplasms and serous cystadenomas arising in the body-tail of the pancreas: MR imaging characterization. Eur Radiol. 2015;25:940–949. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3493-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenssen C, Kahl S. Management of Incidental Pancreatic Cystic Lesions. Viszeralmedizin. 2015;31:14–24. doi: 10.1159/000375282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishigami K, Nishie A, Asayama Y, Ushijima Y, Takayama Y, Fujita N, Takahata S, Ohtsuka T, Ito T, Igarashi H, et al. Imaging pitfalls of pancreatic serous cystic neoplasm and its potential mimickers. World J Radiol. 2014;6:36–47. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i3.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi JY, Kim MJ, Lee JY, Lim JS, Chung JJ, Kim KW, Yoo HS. Typical and atypical manifestations of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: imaging findings with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:136–142. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun HY, Kim SH, Kim MA, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI. CT imaging spectrum of pancreatic serous tumors: based on new pathologic classification. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75:e45–e55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dietrich CF, Dong Y, Froehlich E, Hocke M. Dynamic contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound: A quantification method. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016 doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.193595. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hocke M, Ignee A, Dietrich C. Role of contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound in lymph nodes. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:4–11. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.190929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fusaroli P, Saftoiu A, Dietrich CF. Contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound: Why do we need it? A foreword. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:349–350. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.193596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ignee A, Atkinson NS, Schuessler G, Dietrich CF. Ultrasound contrast agents. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:355–362. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.193594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adsay NV. Cystic neoplasia of the pancreas: pathology and biology. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:401–404. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0348-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adsay NV, Klimstra DS, Compton CC. Cystic lesions of the pancreas. Introduction. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000;17:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braden B, Jenssen C, D‘Onofrio M, Hocke M, Will U, Möller K, Ignee A, Dong Y, Cui XW, Sãftoiu A, et al. B-mode and contrast-enhancement characteristics of small nonincidental neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:49–54. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.200213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dietrich CF, Sahai AV, D‘Onofrio M, Will U, Arcidiacono PG, Petrone MC, Hocke M, Braden B, Burmester E, Möller K, et al. Differential diagnosis of small solid pancreatic lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu X, Zhang S, Ma C, Peng C, Lv Y, Zou X. The diagnostic value of EUS in pancreatic cystic neoplasms compared with CT and MRI. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:324–329. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sahani DV, Kambadakone A, Macari M, Takahashi N, Chari S, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Diagnosis and management of cystic pancreatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;200:343–354. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahani DV, Kadavigere R, Saokar A, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Brugge WR, Hahn PF. Cystic pancreatic lesions: a simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics. 2005;25:1471–1484. doi: 10.1148/rg.256045161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong Y, Wang WP, Mao F, Fan M, Ignee A, Serra C, Sparchez Z, Sporea I, Braden B, Dietrich CF. Contrast enhanced ultrasound features of hepatic cystadenoma and hepatic cystadenocarcinoma. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:365–372. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1259652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Del Chiaro M, Verbeke C, Salvia R, Klöppel G, Werner J, McKay C, Friess H, Manfredi R, Van Cutsem E, Löhr M, et al. European experts consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:703–711. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kishida Y, Matsubayashi H, Okamura Y, Uesaka K, Sasaki K, Sawai H, Imai K, Ono H. A case of solid-type serous cystadenoma mimicking neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:211–215. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perez-Ordonez B, Naseem A, Lieberman PH, Klimstra DS. Solid serous adenoma of the pancreas. The solid variant of serous cystadenoma? Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1401–1405. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199611000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khurana B, Mortelé KJ, Glickman J, Silverman SG, Ros PR. Macrocystic serous adenoma of the pancreas: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:119–123. doi: 10.2214/ajr.181.1.1810119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martínez-Noguera A, D‘Onofrio M. Ultrasonography of the pancreas. 1. Conventional imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:136–149. doi: 10.1007/s00261-006-9079-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim YH, Saini S, Sahani D, Hahn PF, Mueller PR, Auh YH. Imaging diagnosis of cystic pancreatic lesions: pseudocyst versus nonpseudocyst. Radiographics. 2005;25:671–685. doi: 10.1148/rg.253045104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dietrich CF, Ignee A, Braden B, Barreiros AP, Ott M, Hocke M. Improved differentiation of pancreatic tumors using contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:590–597.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D‘Onofrio M, Zamboni G, Faccioli N, Capelli P, Pozzi Mucelli R. Ultrasonography of the pancreas. 4. Contrast-enhanced imaging. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:171–181. doi: 10.1007/s00261-006-9010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dietrich CF, Hocke M, Gallotti A, D´Onofrio M. Solid pancreatic tumors. In: D´Onofrio M, editor Ultrasonography of the pancreas. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer, 2012: 93-110 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Capelli P, Martini PT, D´Onofrio M, Morana G, De Robertis R, Luchini C, Canestrini S, Gobbo S, Mucelli RP. Serous Neoplasms. In: D´Onofrio M, Capelli P, Pederzoli P, editors. Imaging and Pathology of Pancreatic Neoplasms. Milan Heidelberg New York: Springer: 277-310 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dietrich CF, Jenssen C. [Evidence based endoscopic ultrasound] Z Gastroenterol. 2011;49:599–621. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dietrich CF, Hocke M, Jenssen C. [Interventional endosonography] Ultraschall Med. 2011;32:8–22, quiz 23-quiz 25. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1246017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hijioka S, Hara K, Mizuno N, Imaoka H, Bhatia V, Yamao K. Morphological differentiation and follow-up of pancreatic cystic neoplasms using endoscopic ultrasound. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:312–318. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bounds BC, Brugge WR. EUS diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2001;30:27–31. doi: 10.1385/IJGC:30:1-2:027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhutani MS. Role of endoscopic ultrasound for pancreatic cystic lesions: Past, present, and future! Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:273–275. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seicean A, Jinga M. Harmonic contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound fine-needle aspiration: Fact or fiction? Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:31–36. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.196917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serrani M, Lisotti A, Caletti G, Fusaroli P. Role of contrast harmonic-endoscopic ultrasound in pancreatic cystic lesions. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:25–30. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.190931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoo J, Yan LH, Siddiqui AA. Can contrast harmonic endoscopic ultrasonography replace endoscopic ultrasonography-guided fine-needle aspiration in patients with solid pancreatic lesions? An American perspective. Endosc Ultrasound. 2017;6:1–3. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.190930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ignee A, Jenssen C, Cui XW, Schuessler G, Dietrich CF. Intracavitary contrast-enhanced ultrasound in abscess drainage--feasibility and clinical value. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:41–47. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1066423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Choi JH, Seo DW. The Expanding Role of Contrast-Enhanced Endoscopic Ultrasound in Pancreatobiliary Disease. Gut Liver. 2015;9:707–713. doi: 10.5009/gnl15077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoon WJ, Brugge WR. The safety of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic cystic lesions. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:289–292. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Alkaade S, Chahla E, Levy M. Role of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology, viscosity, and carcinoembryonic antigen in pancreatic cyst fluid. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:299–303. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Al-Haddad M. Role of emerging molecular markers in pancreatic cyst fluid. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:276–283. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Belsley NA, Pitman MB, Lauwers GY, Brugge WR, Deshpande V. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: limitations and pitfalls of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2008;114:102–110. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Collins BT. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas with endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspiration biopsy and surgical correlation. Acta Cytol. 2013;57:241–251. doi: 10.1159/000346911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Salomao M, Remotti H, Allendorf JD, Poneros JM, Sethi A, Gonda TA, Saqi A. Fine-needle aspirations of pancreatic serous cystadenomas: improving diagnostic yield with cell blocks and α-inhibin immunohistochemistry. Cancer Cytopathol. 2014;122:33–39. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Villa NA, Berzosa M, Wallace MB, Raijman I. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration: The wet suction technique. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:17–20. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.175877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huang P, Staerkel G, Sneige N, Gong Y. Fine-needle aspiration of pancreatic serous cystadenoma: cytologic features and diagnostic pitfalls. Cancer. 2006;108:239–249. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yip-Schneider MT, Wu H, Dumas RP, Hancock BA, Agaram N, Radovich M, Schmidt CM. Vascular endothelial growth factor, a novel and highly accurate pancreatic fluid biomarker for serous pancreatic cysts. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:608–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cho MK, Choi JH, Seo DW. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided ablation therapy for pancreatic cysts. Endosc Ultrasound. 2015;4:293–298. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.170414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Singhi AD, Nikiforova MN, Fasanella KE, McGrath KM, Pai RK, Ohori NP, Bartholow TL, Brand RE, Chennat JS, Lu X, et al. Preoperative GNAS and KRAS testing in the diagnosis of pancreatic mucinous cysts. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4381–4389. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Frampton AE, Stebbing J, Gall TM, Silver B, Jiao LR, Krell J. Activating mutations of GNAS and KRAS in cystic fluid can help detect intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15:325–328. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.1002771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Springer S, Wang Y, Dal Molin M, Masica DL, Jiao Y, Kinde I, Blackford A, Raman SP, Wolfgang CL, Tomita T, et al. A combination of molecular markers and clinical features improve the classification of pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1501–1510. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kadayifci A, Atar M, Wang JL, Forcione DG, Casey BW, Pitman MB, Brugge WR. Value of adding GNAS testing to pancreatic cyst fluid KRAS and carcinoembryonic antigen analysis for the diagnosis of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:111–117. doi: 10.1111/den.12710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adler DG, Witt B, Chadwick B, Wells J, Taylor LJ, Dimaio C, Schmidt R. Pathologic evaluation of a new endoscopic ultrasound needle designed to obtain core tissue samples: A pilot study. Endosc Ultrasound. 2016;5:178–183. doi: 10.4103/2303-9027.183976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lewin M, Hoeffel C, Azizi L, Lacombe C, Monnier-Cholley L, Raynal M, Arrivé L, Tubiana JM. [Imaging of incidental cystic lesions of the pancreas] J Radiol. 2008;89:197–207. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(08)70395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Box JC, Douglas HO. Management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Am Surg. 2000;66:495–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fernández-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Current management of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Adv Surg. 2000;34:237–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.D‘Onofrio M, Gallotti A, Pozzi Mucelli R. Imaging techniques in pancreatic tumors. Expert Rev Med Devices. 2010;7:257–273. doi: 10.1586/erd.09.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen-Scali F, Vilgrain V, Brancatelli G, Hammel P, Vullierme MP, Sauvanet A, Menu Y. Discrimination of unilocular macrocystic serous cystadenoma from pancreatic pseudocyst and mucinous cystadenoma with CT: initial observations. Radiology. 2003;228:727–733. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2283020973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tanaka M. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas: diagnosis and treatment. Pancreas. 2004;28:282–288. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sugiyama M, Atomi Y, Kuroda A. Two types of mucin-producing cystic tumors of the pancreas: diagnosis and treatment. Surgery. 1997;122:617–625. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski K, Cardenosa G, Mueller PR. Cystic tumors of the pancreas. New clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;212:432–443; discussion 444-445. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199010000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Loftus EV Jr, Olivares-Pakzad BA, Batts KP, Adkins MC, Stephens DH, Sarr MG, DiMagno EP. Intraductal papillary-mucinous tumors of the pancreas: clinicopathologic features, outcome, and nomenclature. Members of the Pancreas Clinic, and Pancreatic Surgeons of Mayo Clinic. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1909–1918. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]