Highlights

-

•

Contingency management (CM) reduces other drug use in opiate addiction treatment.

-

•

Meta-analyses did not find evidence of effectiveness for non-prescribed opiate use.

-

•

CM is effective for cocaine, tobacco, opiates + cocaine, tobacco, polysubstance use.

-

•

Evidence is lacking for long-term effects.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, Contingency management, Opiates, Cocaine, Tobacco, Polysubstance, Reinforcement

Abstract

Background and aims

Use of non-prescribed drugs during treatment for opiate addiction reduces treatment success, creating a need for effective interventions. This review aimed to assess the efficacy of contingency management, a behavioural treatment that uses rewards to encourage desired behaviours, for treating non-prescribed drug use during opiate addiction treatment.

Methods

A systematic search of the databases Embase, PsychInfo, PsychArticles and Medline from inception to March 2015 was performed. Random effects meta-analysis tested the use of contingency management to treat the use of drugs during opiate addiction treatment, using either longest duration of abstinence (LDA) or percentage of negative samples (PNS). Random effects moderator analyses were performed for six potential moderators: drug targeted for intervention, decade in which the study was carried out, study quality, intervention duration, type of reinforcer, and form of opiate treatment.

Results

The search returned 3860 papers; 22 studies met inclusion criteria and were meta-analysed. Follow-up data was only available for three studies, so all analyses used end of treatment data. Contingency management performed significantly better than control in reducing drug use measured using LDA (d = 0.57, 95% CI: 0.42–0.72) or PNS (d = 0.41) (95% CI: 0.28–0.54). This was true for all drugs other than opiates. The only significant moderator was drug targeted (LDA: Q = 10.75, p = 0.03).

Conclusion

Contingency management appears to be efficacious for treating most drug use during treatment for opiate addiction. Further research is required to ascertain the full effects of moderating variables, and longer term effects.

1. Introduction

Amongst those in treatment for opiate addiction, use of non-prescribed drugs is very common. Hair samples from 99 recently deceased opiate addiction patients identified a range of 21 different drugs being used during treatment, including cocaine, amphetamine, morphine and diazepam (Nielsen et al., 2015). Other studies have observed that over a third of patients entering opiate addiction treatment were also DSM-IV dependent on a drug other than heroin (not including nicotine) (Puigdollers et al., 2009), and poly drug use has been reported to be as high as 68% (Taylor, 2015). These high levels of drug use are not limited to illicit substances. Tobacco smoking is highly prevalent in drug treatment in general (Cookson et al., 2014), with prevalence rates of over 90% observed in individuals undergoing methadone treatment for opiate addiction (Best et al., 2009, Clemmey et al., 1997). Methadone itself has been linked to increased tobacco cigarette consumption, smoke intake and self-reported satisfaction of cigarette smoking (Chait and Griffiths, 1984), and to increased alcohol consumption compared with heroin use (Backmund et al., 2003).

Use of non-prescribed drugs during methadone treatment for opiate addiction has been associated with a range of adverse effects such as poor treatment retention and outcomes (Magura et al., 1998). Use of a single drug during opiate addiction treatment is associated with a threefold greater risk of dropping out of treatment, and use of multiple drugs quadruples the risk of dropping out (White et al., 2014). For example, cocaine use during methadone treatment has been linked to persistence of heroin use (Hartel et al., 2011). Similarly, tobacco smoking during opiate detoxification results in significantly greater opiate craving and significantly lower rates of detoxification completion (Mannelli et al., 2013) and is associated with higher levels of illicit drug use (Frosch et al., 2000).

High prevalence rates and the links to adverse treatment outcomes indicate a need for effective interventions for non-prescribed drug use during opiate addiction treatment. One of the most widely used behavioural interventions is contingency management (CM). CM is based on the theory of operant conditioning (Skinner, 1938), which states that the administering of a reward for a particular behaviour increases the likelihood of that behaviour being repeated. In the current context, CM uses rewards (vouchers, clinical privileges or desirable items to be won as prizes for example) to positively reinforce abstinence from or reduced use of drugs during treatment for opiate addiction. CM differs from other common psychological interventions in that the focus of treatment is not on introspective analysis of discrepancies between goals and behaviour (as in motivational interviewing) or modification of flawed cognitive processing (as in CBT), but instead on directly influencing the reinforcement mechanisms involved in addiction (Jhanjee, 2014). Previous reviews have shown CM to be moderately effective in treating substance use (illicit drugs, alcohol and tobacco) disorders in general (Benishek et al., 2014, Davis et al., 2016, Dutra et al., 2008, Lussier et al., 2006, Prendergast et al., 2006), particularly so for opiate addiction (Prendergast et al., 2006). Despite a number of recent reviews assessing the efficacy of CM for substance use in general, very little is known about the use of CM for treating use of non-prescribed drugs in the context of opiate addiction treatment, where treatment outcomes may differ.

Whilst some of these reviews included studies assessing the use of CM in this context (Benishek et al., 2014, Castells et al., 2009, Davis et al., 2016, Lussier et al., 2006), none directly addressed the efficacy of CM for substance use during opiate addiction treatment. The most recent review of this specific use of CM is a meta-analysis published over 16 years ago (Griffith et al., 2000). CM was observed to perform better overall than control, and the effects of CM for drug use during opiate addiction treatment were observed to be moderated by five factors (type of reinforcer, time to reinforcement delivery, targeted CM drug(s), number of urine specimens collected per week and type of subject assignment). However, this review did not search the literature systematically, increasing the risk of bias in the selection of study data. Similarly, it did not assess the effects of different drugs targeted with CM, instead only assessing the moderating effects of targeting single or poly drug use. The aim of the present review was to assess the efficacy of CM for treating the use of different non-prescribed drugs during treatment for opiate addiction, by systematically searching the literature and assessing the effects of potentially moderating variables.

2. Method

A protocol for the current review is available online (see appendix of Supplementary file).

2.1. Search strategy

The review was carried out in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Moher, 2009). Studies were identified using a keyword search of the online databases Embase; PsychInfo; PsychArticles using the Ovid SP interface and a MeSH search of Medline using the PubMed interface; with the following search terms: “Contingency Management” or “Reward” or “Payment” or “Incentive” or Prize” and “Substance” or “Misuse” or “Drug” or “Narcotic*” or “Tobacco” or “Smok*” or “Stimulan*” or “Cocaine” or “Alcohol” and “Opiate” or “Opioid” or “Heroin” or “Methadone”. The search was limited to studies published between each database’s inception and March 2015; published in the English language and including only humans. See appendix1 for full search strategy.

2.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they: i) Tested one or more CM intervention(s) aimed at substance use reduction or abstinence in patients receiving treatment for opiate addiction. CM included any intervention that consistently administered rewards to positively reinforce substance use reduction or abstinence in patients receiving treatment for opiate addiction; ii) used a controlled trial design–either a no/delayed treatment control group or an alternative therapy control group, or controlled by repeated participation in two or more treatment arms; iii) randomised participants to conditions; iv) provided reinforcement or punishment contingent on biological verification of substance use/abstinence; v) used consistent measures of substance use at baseline and follow-up; vi) Published in a peer reviewed journal. Studies were excluded if: i) Participation was non-voluntary – e.g., court orders, prison inmates etc.; ii) means and standard deviations for treatment effects were not available from the published data or the authors.

2.3. Study selection

Studies were reviewed for inclusion by three independent reviewers, with all studies being reviewed for inclusion twice. TA processed all titles and abstracts as first reviewer, RC and LB jointly processed half each as second reviewers. An agreement rate of 96% was reached between reviewers; disagreements were discussed and resolved by a separate reviewer, AM.

2.4. Quality assessment

The ‘Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies’ (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 2003) was used to assess the internal and external validity of all studies, as well as any biases and confounds. This assesses the quality of studies as strong, moderate or weak on six domains (selection bias, study design, confounds, blinding, data collection and withdrawals/dropouts), providing an overall score for the quality of the evidence in the study. A study is rated as providing strong evidence only when all domains are rated as moderate or strong, and a moderate rating when strong or moderate ratings are achieved for all bar one of the domains. Inter-rater reliability has been shown to be ‘fair’ across the six domains and ‘excellent’ overall, often performing better than the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012).

2.5. Data extraction and synthesis

All data extraction was completed by a single reviewer (TA) using an extraction table designed specifically for the current review and agreed by all reviewers (see supplementary materials). Where studies did not contain means and standard deviations for treatment effects, authors were contacted up to two times to obtain the data. Requests for data were sent to authors of 35 studies, with data for six studies being received (Carpenedo et al., 2010, Downey et al., 2000, Epstein et al., 2009, Kirby et al., 2013, Petry et al., 2007, Vandrey et al., 2007). Where means and standard deviations were not obtained, alternative data including F tests, t-tests and chi square were used to calculate an effect size where feasible (Dunn et al., 2010, Shoptaw et al., 2002, Silverman et al., 1998, Silverman et al., 1996).

2.6. Outcome measures

Standardised mean differences (Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988)) were calculated for each individual study using either: 1) longest duration of abstinence (LDA) data or 2) percentage of biochemically verified negative samples (PNS). As follow-up data were available for only three of the 10 studies that included a follow-up period, all data used in analyses are those recorded during treatment.

2.7. Moderators

A number of possible moderators were assessed, based on those shown in previous reviews to impact on the efficacy of CM (Griffith et al., 2000, Prendergast et al., 2006). These included the drug targeted for intervention, the decade in which the study was carried out, the quality of the study, duration of the intervention, the type of reinforcer used, and the form of opiate treatment participants were undergoing. Some moderators previously suggested to affect the efficacy of CM (Griffith et al., 2000, Prendergast et al., 2006) could not be investigated due to a lack of suitable data in the included studies or because all studies used the same approach. For example, the number of times abstinence was verified per week could not be investigated as 16 studies recorded this three times a week compared to only five recording it twice a week and one study recording it every day. Similarly, type of incentive (positive, negative, mixed) was not tested as all bar two studies in both analyses used a mixed incentive. Time to reinforcement could not be tested as all included studies delivered immediate reinforcements.

2.8. Data analysis

Meta-analyses were carried out using RevMan v5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) software. Data were entered into a generic inverse variance analysis in RevMan that analysed the efficacy of CM compared with control across all drug use during treatment for opiate addiction, using both LDA and PNS. All meta-analyses were carried out as random effects analyses due to the wide variety of CM interventions included (Riley et al., 2011). To allow comparison of CM to control, some multi-arm trials were collapsed into a two-arm design by averaging the effects across the treatment conditions (Cochrane Colaboration, 2011). This was only done however when each arm used CM in isolation (other than normal pharmacological treatment for opiate addiction); if a study arm included CM in combination with another behavioural or pharmacological treatment not part of standard treatment, then this arm was not included in the meta-analysis. This was done in order to match the design of the included studies with only single experimental and control arms. Control arms were not collapsed unless each was a standard treatment control. For example, one study (Schottenfeld et al., 2005) had four conditions (CM with either methadone or buprenorphine and performance feedback with either methadone or buprenorphine), so the two CM conditions were collapsed together, as were the two performance feedback conditions. Another study (Preston et al., 2000) also had four conditions (CM, methadone increase, CM + methadone increase and a usual care control), but no conditions were collapsed and only the CM and usual care control conditions were used in the analysis. The I2 statistic was used to assess the percentage of variability in treatment effect estimates attributable to between-study heterogeneity.

Moderator analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software V.3 (Borenstein et al., 2014). Results were computed using random effects statistics and indicate the extent to which each moderator accounts for variability in effect sizes with respect to drug use outcomes. A significant value of Q-between indicates significant differences among effect sizes between the categories of the moderator variable. This method also calculates the mean pooled effect size for each category within the moderator variable being tested and whether this is significant. For the drug targeted for intervention, studies fell into five categories: opiates, cocaine, opiates and cocaine combined, tobacco, and polysubstance use. For study decade, studies were grouped as being published from 1990 to 1999, 2000 to 2009 and 2010 onwards (study publication dates ranged from 1993 to 2015). Study quality followed the strong, moderate and weak ratings of the ‘Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies’ (Effective Public Health Practice Project, 2003). Intervention durations were grouped as <12 weeks, 12 weeks, and >12 weeks. Reinforcer type was categorised as monetary vouchers and ‘other’. Opiate treatment similarly contained two categories, methadone treatment and ‘other’.

Publication bias was assessed using the ‘failsafe N’ technique (Rosenthal, 1979), calculated using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software V.3 (Borenstein et al., 2014). This calculates the number of studies averaging a Z-value of zero that would be required to make the overall pooled effect size non-significant (Rosenthal, 1979).

3. Results

3.1. Included studies

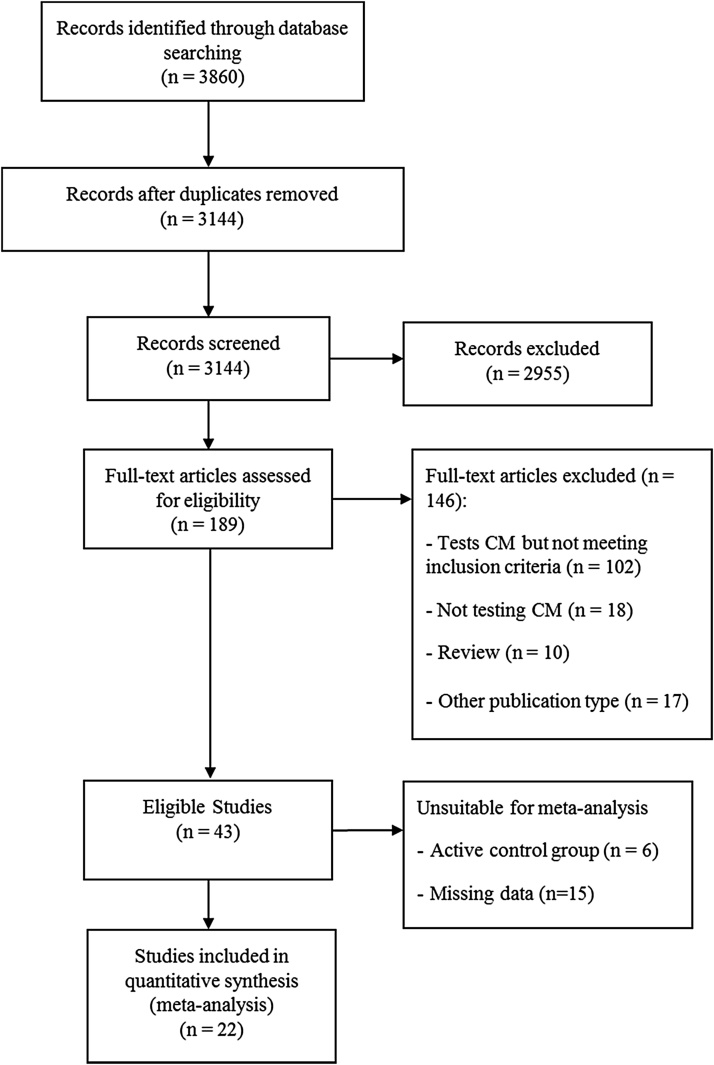

A total of 3144 studies were identified in the search, yielding a total of 22 studies meeting inclusion criteria and included in the meta-analysis (Chutuape et al., 2001, Chutuape et al., 1999, Downey et al., 2000, Dunn et al., 2010, Epstein et al., 2009, Epstein et al., 2003, Gross et al., 2006, Katz et al., 2002a, Katz et al., 2002b, Kidorf and Stitzer, 1993, Kidorf and Stitzer, 1996, Ling et al., 2013, Peirce et al., 2006, Petry et al., 2014, Petry et al., 2007, Petry and Martin, 2002, Preston et al., 2000, Schottenfeld et al., 2005, Silverman et al., 1998, Silverman et al., 1996, Umbricht et al., 2014, Vandrey et al., 2007) (see PRISMA flow diagram, Fig. 1). The included studies randomised a total of 2333 patients to 39 CM conditions and 33 non-CM control conditions. This included three studies with two CM conditions each collapsed into a single CM condition, four studies with three CM conditions each collapsed into a single CM condition, and two studies with two CM, and two control, conditions each collapsed into single CM and control conditions.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Study description and quality assessment

Eight of the 22 studies tested the effects of CM for cocaine use, two for opiate use, one for tobacco smoking, six for combined use of opiates and cocaine and five for polysubstance use. Twenty-one studies included some form of opiate substitution therapy (18 methadone, one buprenorphine, one a mixed buprenorphine and naloxone tablet, and one suboxone), with only a single study not utilising any form of opiate substitution therapy. The duration of CM interventions used ranged between 11 days and 31 weeks, with the number of participants in each study ranging between 12 and 388. Seventeen studies reported retention rates, resulting in an average retention rate of 76.4% (range 51.2%–97.7%). All studies were carried out in the US, with 13 being carried out in the same state (Maryland) (See Table 1 for full description of studies and interventions). Methodological quality assessment rated two studies as overall providing strong evidence, 10 studies moderate evidence and 10 studies weak evidence (Table 2).

Table 1.

Description of each included study and intervention, organised by drug target of CM intervention.

| Study, publication date, publishing journal and location carried out | Design and usual opiate substitution therapy treatment | Participants randomised pre and post intervention | Intervention procedure | CM Schedule, length of intervention and max reward | Additional treatments | Primary Outcome | Abstinence Criteria | Substance use post intervention | Substance use at longest follow up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine | |||||||||

| Epstein et al. (2003) | 2 × 2 factorial design. CM or no CM, and CBT or Social support | Rand − 193 | Urines collected every Mon, Wed and Fri, and vouchers administered dependent on condition | Escalating with reset and bonus for three consecutive negative samples | Individual counselling sessions focussing on cessation of all drugs | Number of drug negative urines | Benzo <300 ng/ml | Throughout intervention, BZE levels were lower in the CM-only and combination groups than in the other two groups. F(1, 185) = 15.94, p < 0.001 | No significant difference between any of the groups at 12 month follow up |

| Psychology of Addictive Behavior Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Meth., between 50 and 80 mg/day | Post − 147 | 12 Weeks | ||||||

| Max $1155 | |||||||||

| Katz et al., 2002a, Katz et al., 2002b | Rand − 40 | Multiple Each phase lasted 11 days | 50% reduction in Benzo. or Benzo <300 ng/ml | ||||||

| Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Repeated measures − single, continuous, interrupted or no voucher meth. 100 mg/day | Post − Not reported | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Vouchers awarded dependent on condition (one large voucher, continuous or interrupted vouchers, or no voucher) | Max reward dependent on condition | Weekly individual and group counselling | Number of consecutive days cocaine abstinence | LDA | Mean abstinence duration was 2 days for no voucher, 3.2 days for single-voucher, and 4.9 and 4.8 days for continuous and interrupted voucher conditions, respectively, F(3, 117) = 7.3, p = < 0.001. | N/A |

| Kidorf et al. (1993) | Rand − 44 | Fixed schedule | Definition not reported | ||||||

| 7 Weeks | |||||||||

| Experimental and Clinical, Psychopharmacology Baltimore, Maryland, USA | CM or Yoked Control group. Ppt were accepted into the 2 years meth. treatment once the exp had done so Meth. 50 mg/day | Post − 43 | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. The single reward was awarded after two consecutive weeks of cocaine abstinence which had to occur within the 7 week probationary period | Single reward of 2 years meth. treatment | Group and individual counselling at least once per week | Two consecutive weeks of cocaine abstinence | PNS | 50% of CM and 14% of control achieved 2 weeks of continuous cocaine abstinence. No significant difference was found between conditions for the number of negative urines returned | No significant difference between the two conditions was found for the proportion of cocaine negative urines submitted |

| Petry et al. (2007) | Rand − 76 | Fishbowl or voucher escalating with reset. | Not reported | ||||||

| Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Connecticut, USA | Prize based (fishbowl) or voucher based CM, or standard care control Meth. Mean dose between 78.4 and 83 mg/day dependent on condition | Post − 59 | Urines collected twice per week with an average of 4 days between submissions. Negative samples resulted in draws from the prize earn, or vouchers. | 12 weeks Max up to $300 and $585 respectively | Weekly individual and/or group counselling | Cocaine abstinence | LDA and PNS | Fishbowl CM ppt achieved significantly greater LDA than control ppt. Voucher CM ppt did not. | No significant difference between percentage of participants submitting negative samples in any condition at 9 months |

| Silverman et al. (1998) | Rand −59 | Escalating with reset, with bonuses in one condition. 12 weeks | Benzo. <300 ng/ml | ||||||

| Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Three conditions, Escalating CM, Escalating CM with start bonus, and yoked control Meth. Mean dose 62 mg/day | Post − Average retention 10.3–11.3 weeks dependent on condition | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Vouchers dispensed after urines tested | Max reward $1950 without bonuses | Offered weekly individual counselling | Not reported | LDA | Both CM conditions achieved significantly longer durations of abstinence | Difference between CM groups and control remained significant at 8 weeks |

| Silverman et al. (1996) | Two conditions, escalating with reset CM and yoked control | Rand − 37 | Urines taken Mon, Wed and Fri. | Escalating with reset and bonus. | Benzo. <300 ng/ml | ||||

| 12 weeks | |||||||||

| Archives of General Psychiatry, Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Meth. 50 mg/day | Post − 89% of exp ppt and 83% of ctrl ppt retained for full 12 weeks | Vouchers given for abstinence | Max $1155 | Weekly individual counselling (45 min per week) | Not reported | LDA | Exp patients achieved significantly longer durations of sustained cocaine abstinence than ctrl ppt (F(1.35) = 13.5; p = <0.001) | No significant difference found between groups 4 weeks post intervention |

| Umbricht et al. (2014) | 2 × 2 Design. CM or Yoked control and Topiramate or placebo. | Rand − 171 | Escalating with reset. | Benzo. <300 ng/ml | |||||

| Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Meth. 100 mg/day | Post − 113 | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Vouchers awarded for abstinence | 31 weeks Max $1155 | Weekly individual and group counselling | Cocaine abstinence between weeks 9 and 20 | PNS and LDA | No significant difference found between any of the conditions | N/A |

| Vandrey et al. (2007) | Rand − 12 | Fixed, with a single voucher or cheque available in each condition. | Benzo. <300 ng/ml | ||||||

| Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology | 2 × 4 design − 2 types of reward type (voucher or cheque) and 4 types of reward magnitude ($0, $25, $50 or $100) Meth., dose not reported | Post − Not reported | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Rewards were provided for evidence of abstinence Mon to Wed, on the Thur | 16 weeks (two 8 week periods) Largest voucher value $100 | Group and individual counselling | Not reported | PNS | No main effect of incentive type. Planned comparisons found that high value cheques resulted in significantly greater abstinence than high value vouchers | N/A |

| Opiates | |||||||||

| Ling et al. (2013) | 4 conditions, 4 CM, CBT, CM + CBT and no behavioural treatment Control | Rand − 202 | Fishbowl with escalating draws. | Exact criteria not reported | |||||

| Addiction, Los Angeles, USA | Suboxone, variable dose | Post − 134 | Urines collected twice weekly, with escalating numbers of draws for vouchers dependent on drug free urines | 16 weeks Max initially $2196, later reduced to $14600 | Counselling | Proportion of opiate negative urines | PNS | Mean number of consecutive opioid-negative UA results did not differ significantly by group. | Same results 52 week follow up as post treatment |

| Preston et al. (2000) | Rand − 120 | Escalating with reset. | <300 ng/ml opiates | ||||||

| 8 weeks | |||||||||

| Archives of General Psychiatry, Baltimore, Maryland, USA | 4 Conditions: CM, Increased meth. with non contingent vouchers, CM + meth. increase, usual treatment control with non contingent vouchers Meth. dose not reported | Post − 112 | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Vouchers administered for evidence of abstinence | Max $554 | Weekly individual counselling | Opiate negative urine samples | PNS and LDA | LDA significantly increased with contingent vouchers (F(1116) = 10.02, p = 0.002) | N/A |

| Cocaine and Opiates | |||||||||

| Chutuape et al. (2000) | Rand − 53 | Escalating with reset. | |||||||

| Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Baltimore, Maryland, USA | 3 conditions: CM with weekly or monthly urine testing, and a control where take home meth. was awarded randomly Meth. 60 mg/day | Post − 43 | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. One urine randomly selected either weekly or monthly dependent on condition to decide whether vouchers awarded | 28 weeks Max reward was take home doses for all weeks | Weekly individual and group counselling sessions | Not reported | Not reported | The mean LDA was 10.5 (SD 8.9), 8.4 (SD 8.5), and 5.4 (SD 7) weeks for the Weekly, Monthly, and Random Drawings groups, respectively (F(2.52) 1.9, PB0.16). | N/A |

| Epstein et al. (2009) | Rand − 252 | Escalating with reset. | <300 ng/ml for both opiates and cocaine | ||||||

| Drug Alcohol Dependence, Baltimore, Maryland, USA | 3 × 2 dose by contingency design − meth. dose of either 70 mg or 100 mg and yoked control, CM for cocaine or split CM for cocaine and opiates | Post − 23% of ppt dropped out before the end of the intervention | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Vouchers were awarded for abstinence from cocaine and opiates either together or separately dependent on condition | 12 weeks Max not reported | Weekly individual counselling | Percentages of urine specimens negative for heroin, cocaine, and both simultaneously | PNS and LDA | Main effect of contingency on cocaine-negative urines, (F(2244) = 7.36, p = 0.0008) and on urines simultaneously negative for opiates and cocaine, (F(2244) = 3.61, p = 0.0285) but not in opiate-negative urines, (F(2244) = 2.51, p = 0.0830) | N/A |

| Groß et al. (2006) | Three conditions: CM vouchers, Reduction in medication, and standard treatment control | Rand − 60 | Escalating with reset and bonus. | <300 ng/ml of cocaine or opiates | |||||

| Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, Vermont, USA | Bup, maintained on either 4 mg/70 kg or 8 mg/70 kg for the duration of the study | Post − 45 | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Dependent on condition, ppt either earned points, or did not have their bup dose decreased on evidence of abstinence | 12 weeks Max $269 | Behavioural drug counselling | Mean duration of continuous abstinence, total number of weeks abstinent (non-continuous), and number of missing visits. | LDA | Contingent medication ppt achieved significantly greater durations of continuous abstinence (M = 5.9 weeks, SD = 4.6) than ppt in the voucher group (M = 2.9 weeks, SD = 3.3; Fisher’s LSD, p=0.05). | N/A |

| Katz et al. (2002a,b) | Two conditions, CM or Standard care | Rand − 52 | <300 ng/ml for both opiates and cocaine | ||||||

| Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Meth. 100 mg/day | Post − Mean 35.9 days (of 180) in treatment | Urines collected three times per week and vouchers administered for negative samples | Escalating with reset and bonus 12 weeks Max $1,087.50 | Weekly individual cognitive behavioural counselling | Not reported | LDA and PNS | No statistically significant condition effects found | N/A |

| Petry et al. (2002) | CM or standared treatment | Rand − 42 | Fishbowl, escalating draws. | Not reported | |||||

| Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Connecticut, USA | Meth. Average 69 or 70 mg/day in standard treatment and CM | Post − 39 | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Ppt received on draw for abstinence from either cocaine or opiates, and four for abstinence from both. Continuous weekly abstinence earned bonus draws | 12 weeks Max number of draws dependent on abstinence from different drugs | Monthly individual counselling | Weeks of continuous abstinence from both opioids and cocaine | LDA | There were significant group difference in the percentage of urine samples negative for both drugs (F(1, 40) = 4.01, p = 0.05 | The percentage of urine samples negative for both opioids and cocaine was higher in exp than ctrl ppt (U = 112.0, p=0.05.) at 6 month follow up |

| Schottenfeld et al. (2005) | Rand − 162 | Escalating with reset. | <300 ng/ml for both opiates and cocaine | ||||||

| The American Journal of Psychiatry, USA | 2 × 2 design: meth. or buprenorphine and CM or performance feedback Maximum daily meth. dose of 85 mg or bup. dose of 16 mg | Post − Cumulative proportion: meth. + CM − 0.6, meth. + performance feedback − 0.75, Bup + CM − 0.45, Bup + Performance feedback − 0.5 | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri and vouchers administered for evidence of abstinence | 24 week Max $1033.50 | Individual counselling twice weekly for the first 12 weeks and weekly for the last 12 | Maximum number consecutive weeks of abstinence and proportion of drug-free urine tests | LDA | meth. ppt achieved significantly longer periods of abstinence than bup. There were no significant effects of CM (F = 0.09, df = 1, 158, p = 0.76) and no significant interaction between medication and CM (F = 0.10, df = 1, 158, p = 0.75) | N/A |

| Tobacco | |||||||||

| Dunn et al. (2010) | Rand − 40 | Escalating with reset 90 days | |||||||

| Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology Vermont, USA | Two conditions: CM and non contingent voucher Meth. 107.6 ± 8.8 mg/day or Bup. 14.9 ± 1.3 mg/day | Post − 25 | Biochemical verification taken everyday with vouchers for abstinence delivered daily. Numerous bonus's available for abstinence at certain points | Max $362.50 | None reported | Percentage of biochemical samples meeting abstinence criteria | Abstinence defined as breath CO ≤ 6 ppm during days 1–5 and a urine cotinine ≤ 80 ng/ml on Days 6–14 PNS and LDA | Exp. Ppt submitted significantly more negative samples than ctrl. Ppt (t (30.1) = 3.24, p < 0.01) | No significant difference between the two conditions at any follow up |

| Poly substance use | |||||||||

| Chutuape et al. (1999) | Two conditions: CM and usual care control | Rand − 14 | <200 ng/ml for meth., opiates, cocaine and benzodiazepines | ||||||

| Drug and Alcohol Dependence, Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Meth. 71 mg/day or 77 mg/day in CM and standard care conditions | Post − 12 | Urines collected Mon, Wed and Fri. Vouchers or take homes administered for evidence of abstinence dependent on ppt choice | Fixed. 12 weeks Max $900 or three take homes per week dependent on ppt choice | Twice-weekly counselling sessions (one individual and one group session) | Number of drug free urines | LDA | mean LDA for exp ppt was 8.4 and 1 week for ctrl ppt (t(8) = 5.9, p = <0.001.) | 5 ppt relapsed after the CM intervention. ended, generally within the first week |

| Downey et al. (2000) | Two conditions: CM and Yoked control | Rand − 41 | Urines taken Mon, Wed and Fri. | Escalating with reset and bonus. | <300 ng/ml for all drugs other than phencyclidine which was <25 ng/ml | ||||

| Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, USA | Mixed Bup. Naloxone tablets. Dose not reported | Post − 21 | Vouchers administered for evidence of abstinence | 12 weeks Max not reported | Weekly cognitive behavioural substance abuse therapy | Not reported | LDA | No sig difference between the two groups on% drug free urines, LDA or total abstinence for heroin, cocaine or poly drug use during the voucher phase | N/A |

| Kidorf et al. (1996) | Rand − 16 | Fixed with negative consequences for drug positive samples. | |||||||

| Behavior Therapy, Baltimore, Maryland, USA | Two conditions: CM and usual care control Meth. 60 mg/day | Post − 14 | Urines collected Twice per week and take homes administered for evidence of abstinence. Samples positive for drugs resulted in meth. being administered in a split dose | 2 month cross over Max 2 take homes per week | Weekly individual counselling | Percentage of drug free urines | Breath alcohol < 0.5, other drug cut-offs not reported PNS | A condition main effect was found, (F(2, 30) = 4.43, p = < 0.05.) Patients submitted more drug-free urines when exposed to exp (M = 29%; SE = 9.0) than ctrl (M = 9%; SE = 3.0) | N/A |

| Peirce et al. (2006) | Rand − 388 | Fishbowl, escalating with reset. | Not reported | ||||||

| Archives of General Psychiatry USA | Two conditions: CM and usual care control Meth. Doeses ranging between 67.9 mg/day to 108 mg/day dependent on recruitment centre | Post − 67.1% of exp ppt and 64.8% ctrl ppt retained | Urines collected twice per week and prize draws allowed for evidence of abstinence | 12 weeks Max 204 draws, resulting in a maximum of approx. $400 in prizes, plus one guaranteed $20 prize. | Individual and group consoling. Frequency ranged from 3 times per week to once per month | Not reported | LDA | Exp ppt were significantly more likely to submit stimulant- and alcohol-negative samples than were ctrl ppt (OR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.42-2.77; missing samples coded as missing) | No group differences in percentage of submitted samples negative for stimulants and alcohol (χ2 = 0.08, P=0.78). |

| Petry et al. (2015) | Rand − 240 | Escalating with reset for either fishbowl draws or vouchers dependent on condition. | Not reported | ||||||

| Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, USA | Four conditions: $300 prize CM, $900 prize CM, $900 voucher CM and usual care control Meth. Doses ranging between 77 mg/day and 85.4 mg/day | Post − Not reported | Urines taken at least twice a week with at least 2 days between tests. Abstinence resulted in either fishbowl draws or vouchers | 12 weeks Max either $300 or 900$ | Weekly group counselling | LDA and proportion of samples submitted negative for cocaine and alcohol | PNS and LDA | The longest duration of abstinence and proportion of samples testing negative were significantly greater in each of the three CM conditions relative to usual care (F(3236) = 3.39, p = 0.02 and F(3236) = 3.94, p=0.009 respectively) | At the 12-month follow-up, 113 of 225 (50.2%) patients submitted negative samples |

Abbreviations – Rand- Randomised to conditions, Post- Post intervention, Exp – Experimental condition(s), Ctrl – Control condition, CM – Contingency Management, TLFB – Time Line Follow Back, LDA – longest duration of abstinence, PNS – percentage of negative samples, Meth. – methadone, Bup. – buprenorphine, Pbo. – placebo, ppt – participants, Benzo – benzoylecgonine, OST – Opiate substitution therapy.

Table 2.

EPHPP ratings for all included studies organised by drug target of CM intervention.

| Study | Selection Bias | Study Design | Confounds | Blinding | Data Collection | Withdrawals/ Dropouts | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine | |||||||

| Epstein et al. (2003) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Strong |

| Katz et al., 2002a, Katz et al., 2002b | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Moderate |

| Kidorf et al. (1993) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Moderate |

| Petry et al. (2007) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Weak |

| Silverman et al. (1996) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Moderate |

| Silverman et al. (1998) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Moderate |

| Umbricht et al. (2014) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Vandrey et al. (2007) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Weak |

| Opiates | |||||||

| Ling et al. (2013) | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Preston et al. (2000) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Weak |

| Opiates and Cocaine | |||||||

| Chutuape et al. (2000) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Weak |

| Epstein et al. (2009) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Groß et al. (2006) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Katz et al., 2002a, Katz et al., 2002b | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Moderate |

| Petry et al. (2002) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Strong |

| Schottenfeld et al. (2005) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | Weak |

| Tobacco | |||||||

| Dunn et al. (2010) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Moderate |

| Poly-substance | |||||||

| Chutuape et al. (1999) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Weak |

| Downey et al. (2000) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Weak |

| Kidorf et al. (1996) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Weak |

| Peirce et al. (2006) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Weak |

| Petry et al. (2015) | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | Weak |

1 = Strong, 2 = Moderate, 3 = Weak

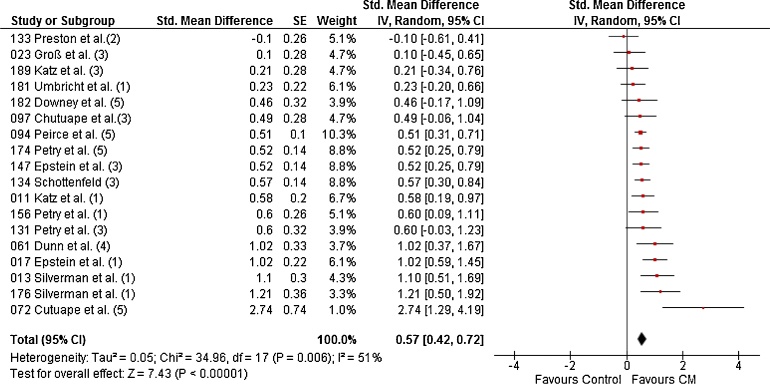

3.3. Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis for LDA (longest duration of abstinence) from all substances combined contained 18 studies randomising 2059 patients to 31 CM conditions and 25 non-CM control conditions. The random effects meta-analysis produced a pooled effect size of d = 0.57 (95% CI: 0.42–0.72), with CM performing significantly better than control (Fig. 2). A moderate (Cochrane Colaboration, 2011) level of the variability of effects between studies was due to between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 51%).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot for LDA during treatment of all substances combined. (1) = Cocaine, (2) = opiates, (3) = opiates and cocaine, (4) = Tobacco, (5) = Poly-substance.

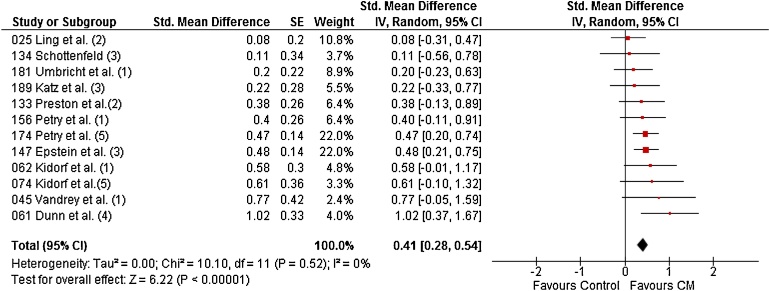

For PNS (percentage of negative samples), 12 studies randomising 1387 patients to 24 CM conditions and 21 non-CM control conditions were included and the pooled effect size was d = 0.41 (95% CI: 0.28–0.54), again with CM performing significantly better than control (Fig. 3). Variability of effects was not due to between-study heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for PNS during treatment of all substances combined. (1) = Cocaine, (2) = opiates, (3) = opiates and cocaine, (4) = Tobacco, (5) = Poly-substance.

3.4. Moderator analysis

The only moderator found to have a significant effect on the efficacy of CM was intervention drug target, but only for LDA (Table 3, Table 4). Within each of the categories of the six moderators, CM performed significantly better than control in all but three instances. Within drug targeted for intervention, CM performed no better than control for treating non-prescribed opiate use for both LDA and PNS. Within intervention duration, CM failed to encourage significantly better LDA than control in studies with intervention duration of less than 12 weeks. Within opiate treatment type, CM did not result in significantly greater PNS than control for studies where participants were in the ‘other’ category.

Table 3.

Random effects moderator analysis results for LDA.

| Moderator | k1 | Effect Size (d)2 | 95% CI | Z Value | P value | Q between (df)3 | P of Q between |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug targeted for intervention | 18 | 10.75 (4) | 0.03 | ||||

| Cocaine | 6 | 0.75 | 0.45–1.04 | 4.91 | <0.001 | ||

| Opiates | 1 | −0.10 | −0.61–0.41 | −0.40 | 0.70 | ||

| Opiates and cocaine | 6 | 0.48 | 0.32–0.64 | 5.85 | <0.001 | ||

| Tobacco | 1 | 1.02 | 0.37–1.67 | 3.10 | <0.01 | ||

| Poly substance | 4 | 0.62 | 0.27–0.98 | 3.45 | <0.01 | ||

| Study decade | 1.31 (2) | 0.52 | |||||

| 1990–1999 | 4 | 1.08 | 0.14–2.02 | 2.23 | 0.02 | ||

| 2000–2009 | 10 | 0.53 | 0.41–0.65 | 8.67 | <0.001 | ||

| 2010 onwards | 4 | 0.53 | 0.32–0.74 | 4.92 | <0.001 | ||

| Study Quality | 2.66 (2) | 0.23 | |||||

| Stong | 2 | 0.87 | 0.48–1.27 | 4.37 | <0.001 | ||

| Moderate | 8 | 0.57 | 0.32–.82 | 4.47 | <0.01 | ||

| Weak | 8 | 0.51 | 0.30–0.72 | 4.75 | <0.001 | ||

| Intervention Duration | 1.30 (2) | 0.52 | |||||

| <12 Weeks | 2 | 0.26 | −0.41–0.93 | 0.77 | 0.44 | ||

| 12 Weeks | 12 | 0.63 | 0.44–0.82 | 6.42 | <0.001 | ||

| >12 Weeks | 4 | 0.53 | 0.27–0.79 | 4.04 | <0.001 | ||

| Reinforcer type | 0.022 | 0.88 | |||||

| Monetary Vouchers | 16 | 0.57 | 0.41–0.74 | 6.86 | <0.001 | ||

| Other' | 2 | 0.54 | 0.13–0.95 | 2.55 | 0.01 | ||

| Opiate treatment | 0.65 | 0.42 | |||||

| Methadone | 13 | 0.61 | 0.42–0.80 | 6.45 | <0.001 | ||

| Other | 5 | 0.47 | 0.20–0.74 | 3.46 | <0.01 | ||

1Number of studies, 2Weighted random effects, 3A significant value of Q-between indicates significant differences among effect sizes between the categories of the moderator variable

Table 4.

Random effects moderator analysis results for PNS.

| Moderator | k1 | Effect Size (d)2 | 95% CI | Z Value | P value | Q betweeen (df)3 | P of Q between |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug targeted for intervention | 6.43 (4) | 0.17 | |||||

| Cocaine | 4 | 0.4 | 0.13–0.67 | 2.89 | <0.01 | ||

| Opiates | 3 | 0.18 | −0.11–0.46 | 1.23 | 0.22 | ||

| Opiates and cocaine | 2 | 0.43 | 0.18–0.67 | 3.42 | <0.01 | ||

| Tobacco | 2 | 1.02 | 0.37–1.67 | 3.09 | <0.01 | ||

| Poly substance | 1 | 0.49 | 0.23–0.74 | 3.74 | <0.001 | ||

| Study decade | 1.10 (2) | 0.58 | |||||

| 1990–1999 | 2 | 0.51 | 0.25–0.77 | 3.83 | <0.001 | ||

| 2000–2009 | 3 | 0.30 | 0.01–0.59 | 2.01 | 0.05 | ||

| 2010 onwards | 7 | 0.40 | 0.20–0.60 | 3.93 | <0.001 | ||

| Study Quality | 0.36 (2) | 0.84 | |||||

| Stong | 1 | 0.48 | 0.21–0.75 | 3.43 | <0.01 | ||

| Moderate | 5 | 0.36 | 0.06–0.66 | 2.32 | 0.02 | ||

| Weak | 6 | 0.44 | 0.30–0.58 | 0 | <0.001 | ||

| Itntervention Duration | 0.32 (2) | 0.85 | |||||

| <12 Weeks | 5 | 0.47 | 0.28–0.67 | 4.73 | <0.001 | ||

| 12 Weeks | 2 | 0.42 | 0.18–0.67 | 3.35 | 0.04 | ||

| >12 Weeks | 5 | 0.37 | 0.02–0.71 | 2.06 | <0.01 | ||

| Reinforcer type | 0.41 (1) | 0.52 | |||||

| Monetary Vouchers | 9 | 0.39 | 0.23–0.54 | 4.82 | <0.001 | ||

| Other' | 3 | 0.51 | 0.17–0.85 | 2.94 | <0.01 | ||

| Opiate treatment | 0.35 (1) | 0.55 | |||||

| Methadone | 8 | 0.45 | 0.30–0.60 | 6.00 | <0.001 | ||

| Other | 4 | 0.32 | −0.08–0.72 | 1.58 | 0.12 | ||

1Number of studies, 2Weighted random effects, 3A significant value of Q-between indicates significant differences among effect sizes between the categories of the moderator variable.

3.5. Publication bias

There is widespread acceptance of the fact that studies reporting positive results are far more likely to be published than studies reporting null findings, resulting in an over representation of positive results within the literature (Rosenthal, 1991, Rosenthal and Rubin, 1988, Schmid, 2016). The ‘failsafe N’ (Rosenthal, 1979) calculates the number of studies reporting null results that would be required to overturn the statistically significant difference between CM and control observed above. For LDA, 560 papers reporting null results would be required, and 101 for PNS.

4. Discussion

Overall, the random effects analyses showed CM performed significantly better than control in encouraging abstinence from a range of different drugs in patients undergoing treatment for opiate addiction. This was the case when measuring both LDA and PNS, producing medium and small (Cohen, 1988) pooled effect sizes respectively. Moderator analysis performed on drug targeted for intervention, decade in which the study was carried out, quality of the study, duration of the intervention, type of reinforcer used, and form of opiate treatment, showed drug target for LDA data to be the only characteristic significantly moderating the efficacy of CM, driven primarily by the ineffectiveness of CM in treating opiate use. Despite only a single significant moderator effect, within each of the six moderator categories CM was found to perform significantly better than control in all but three cases. CM performed no better than control in encouraging abstinence from non-prescribed opiates during treatment for opiate addiction, measuring both LDA and PNS. CM also performed no better than control for LDA in studies with interventions less than 12 weeks long, and PNS in studies where usual opiate treatment was anything but methadone treatment. CM for other non-prescribed drug use in treatment for opiate addiction had no negative impact on usual treatment retention compared to three-month follow-up retention rates observed in usual opiate treatment (Burns et al., 2015, Hansen et al., 1990, Soyka et al., 2008).

This review has a number of limitations. One aim of the moderator analysis was to analyse the effects of CM by target drug type. To improve on the work of Griffith et al. (2000), five categories of drugs were used rather than two. However, one of them, polysubstance use, combined studies with four differing definitions of this, making results hard to integrate. CM still performed better in this category though, suggesting a robustness of effects across a variety of different drug combinations. Another limitation is that the review does not contain any grey literature. This means that any CM studies that have been conducted yet never published are not included in the analysis.

The current review does have a number of strengths however. It is the first review in over 16 years to address directly the efficacy of CM for encouraging abstinence from non-prescribed drug use during treatment for opiate addiction. This is important as CM has gained considerable support in this time, having been recommended since 2007 as a treatment for drug misuse by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Pilling et al., 2007). The findings of the current review support those of the previous reviews carried out in the field; finding an overall positive small to medium (Cohen, 1988) effect size for CM in treating drug use in opiate addiction treatment (Griffith et al., 2000). This is in contrast to the usual small effect size of psychological interventions in the field (Dutra et al., 2008). Findings of the present review are also similar to those of a previous reviews assessing the use of CM for drug use overall, regardless of treatment setting which found similar small to medium effect sizes for drug use in general (Benishek et al., 2014, Castells et al., 2009, Davis et al., 2016, Lussier et al., 2006, Prendergast et al., 2006). The robustness of the effects of CM across different client groups suggests potential utility in treating a diverse range of individuals and needs within the addictions field.

We found no evidence of CM working better than control in encouraging abstinence from non-prescribed opiates during treatment, which is in contrast to Prendergast et al. (2006) who identified CM as one of the most effective treatments for opiate use. The current review included only two studies of this type, compared to four (different) studies included in the previous review because of differing review aims. Moreover, three of the four opiate studies in the previous review systematically reduced methadone doses to zero over the course of the intervention, thereby increasing the likelihood of relapse to opiates and perhaps handing those receiving CM a competitive advantage over those not. Studies in the current review however maintained medication doses throughout the duration of the intervention, possibly eliminating this advantage and leading to the observed non-significant finding. With more data however, results for opiates may more closely follow the trends observed with other drugs.

The moderator analysis performed in the current review has also produced contradictory results to previous reviews. Previous reviews (Griffith et al., 2000, Prendergast et al., 2006) found four of the six moderators analysed here to have a significant effect on the efficacy of CM (drug targeted for intervention, the decade in which the study was carried out, the quality of the study evidence, the length of the intervention period). The current study only found a significant effect for drug targeted for intervention however. A possible explanation for this is differences in analysis, with the previous reviews adopting a fixed effects analysis, and the current the more conservative and more widely recommended (Cochrane Colaboration, 2011) random effects analysis. Support for this comes from more recent reviews that have adopted this same random effects analysis. Lussier et al. (2006) for example analysed the effects of three (drug targeted for intervention, the decade in which the study was carried out, the quality of the study evidence) moderators also analysed in the current and previous reviews, finding none of them to have a significant effect.

More general limitations within the field have also been identified, for example a lack of data available for meta-analysis. In the current review, a total of 21 studies that met all other inclusion criteria could not be included in the quantitative data synthesis. This lack of available data is even more pronounced for follow-up, with only 10 of the 22 included studies utilising some sort of follow-up element in their study design, with data available for only three. CM is often criticised for poor follow-up results, but given the paucity of data we were not able to explore this here. Another concern is the quality of the studies included, with only two studies being rated as providing strong evidence, and 20 papers providing weak evidence. Notably, every study in the current review was performed in the US, with at least 13 performed in the same state and 17 having at least one co-author from the same institution. This significantly limits the generalisability of the currently available evidence on CM for non-prescribed drug use in opiate addiction treatment.

This lack of evidence does however present avenues for future research, particularly the use of CM for tobacco smoking in opiate addiction treatment. This is especially relevant considering that tobacco smoking is the most prevalent form of drug use in opiate addiction treatment (Best et al., 2009, Clemmey et al., 1997), and it has been shown that individuals in treatment for opiate addiction treatment have a mortality rate four times that of non-smokers (Hser et al., 1994). It is similarly important that future research studies are carried out in a wider range of countries, include follow-ups to investigate relapse after the removal of rewards, and focus on improving the overall quality of the data that are published.

In conclusion, CM appears to be an efficacious treatment of the use of cocaine, non-prescribed opiates and cocaine, tobacco, and polysubstance use during opiate addiction treatment, but not for use of non-prescribed opiates. Evidence about longer-term efficacy in this treatment context remains lacking, as is research into the effects of CM on tobacco, the most prevalent secondary addiction in this population.

Contributors

LB and RC acted as second reviewers during study selection. AM, LB and JS had editorial input during manuscript preparation. All authors approved of the final manuscript before submission.

Role of funding source

This work was funded as part of TA’s PhD studentship by the Medical Research Council and the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (MRC/IoP Excellence Studentship). Funding: LB is funded by a Cancer Research UK/BUPA Foundation Fellowship (C52999/A19748). All authors are part of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration Public Health Research: Centre of Excellence. Funding from the Medical Research Council, British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration is gratefully acknowledged (MR/K023195/1). The funders played no role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the manuscript and in the decision to submit this manuscript for publication. JS has previously received funding from the NIHR to test the application of contingency management in opiate addiction treatment.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all those that took time and effort to locate and send data to aid in the analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.05.028.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Armijo-Olivo S., Stiles C.R., Hagen N.A., Biondo P.D., Cummings G.G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: a comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: methodological research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012;18:12–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backmund M., Schütz C.G., Meyer K., Eichenlaub D., Soyka M. Alcohol consumption in heroin users, methadone-substituted and codeine-substituted patients–frequency and correlates of use. Eur. Addict. Res. 2003;9(45–50):67733. doi: 10.1159/000067733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benishek L.A., Dugosh K.L., Kirby K.C., Matejkowski J., Clements N.T., Seymour B.L., Festinger D.S. Prize-based contingency management for the treatment of substance abusers: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2014;109:1426–1436. doi: 10.1111/add.12589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best D., Lehmann P., Gossop M., Harris J., Noble A., Strang J. Eating too little, smoking and drinking too much: wider lifestyle problems among methadone maintenance patients. Addict. Res. 2009;6:489–498. [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M., Hedges L., Higgins J., Rothstein H. 2014. Comprehensive Meta Analysis V3. [Google Scholar]

- Burns L., Gisev N., Larney S., Dobbins T., Gibson A., Kimber J., Larance B., Mattick R.P., Butler T., Degenhardt L. A longitudinal comparison of retention in buprenorphine and methadone treatment for opioid dependence in New South Wales, Australia. Addiction. 2015;110:646–655. doi: 10.1111/add.12834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenedo C.M., Kirby K.C., Dugosh K.L., Rosenwasser B.J., Thompson D.L. Extended voucher-based reinforcement therapy for long-term drug abstinence. Am. J. Health Behav. 2010;34:776–787. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.6.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castells X., Kosten T.R., Capellà D., Vidal X., Colom J., Casas M. Efficacy of opiate maintenance therapy and adjunctive interventions for opioid dependence with comorbid cocaine use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:339–349. doi: 10.1080/00952990903108215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chait L., Griffiths R. Effects of methadone on human cigarette smoking and subjective ratings. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1984;229:636–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape M.A., Silverman K., Stitzer M. Contingent reinforcement sustains post-detoxification abstinence from multiple drugs: a preliminary study with methadone patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;54:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutuape M.A., Silverman K., Stitzer M.L. Effects of urine testing frequency on outcome in a methadone take-home contingency program. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;62:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemmey P., Brooner R., Chutuape M.A., Kidorf M., Stitzer M. Smoking habits and attitudes in a methadone maintenance treatment population. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Colaboration . 2011. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane Collaboration . 2014. Review Manager v5.3. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.; 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Cookson C., Strang J., Ratschen E., Sutherland G., Finch E., McNeill A. Smoking and its treatment in addiction services: clients’ and staff behaviour and attitudes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014;14:304. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D.R., Kurti A.N., Skelly J.M., Redner R., White T.J., Higgins S.T. A review of the literature on contingency management in the treatment of substance use disorders. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2016;2009–2014:2009–2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey K.K., Helmus T.C., Schuster C.R. Treatment of heroin-dependent poly-drug abusers with contingency management and buprenorphine maintenance. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:176–184. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn K.E., Sigmon S.C., Reimann E.F., Badger G.J., Heil S.H., Higgins S.T. A contingency-management intervention to promote initial smoking cessation among opioid-maintained patients. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010;18:37–50. doi: 10.1037/a0018649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L., Stathopoulou G., Basden S.L., Leyro T.M., Powers M.B., Otto M.W. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:179–187. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effective Public Health Practice Project . 2003. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein D.H., Hawkins W.E., Covi L., Umbricht A., Preston K.L. Cognitive-behavioral therapy plus contingency management for cocaine use: findings during treatment and across 12-month follow-up. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2003;17:73–82. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein D.H., Schmittner J., Umbricht A., Schroeder J.R., Moolchan E.T., Preston K.L. Promoting abstinence from cocaine and heroin with a methadone dose increase and a novel contingency. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosch D.L., Shoptaw S., Nahom D., Jarvik M.E. Associations between tobacco smoking and illicit drug use among methadone-maintained opiate-dependent individuals. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:97–103. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith J.D., Rowan-Szal G.A., Roark R.R., Simpson D.D.D. Contingency management in outpatient methadone treatment: a meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A., Marsch L.a., Badger G.J., Bickel W.K. A comparison between low-magnitude voucher and buprenorphine medication contingencies in promoting abstinence from opioids and cocaine. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:148–156. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen W.B., Tobler N.S., Graham J.W. Attrition in substance abuse prevention research: a meta-analysis of 85 longitudinally followed cohorts. Eval. Rev. 1990;14:677–685. [Google Scholar]

- Hartel D.M., Schoenbaum E.E., Selwyn P.A., Kline J., Davenny K., Klein R.S., Friedland G.H. Heroin use during methadone maintenance treatment: the importance of methadone dose and cocaine use. Am. J. Public Health. 2011;85:83–88. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser Y.I., McCarthy W.J., Anglin M.D. Tobacco use as a distal predictor of mortality among long-term narcotics addicts. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 1994;23:61–69. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhanjee S. Evidence based psychosocial interventions in substance use. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2014;36:112–118. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.130960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E.C., Chutuape M.A., Jones H.E., Stitzer M.L. Voucher reinforcement for heroin and cocaine abstinence in an outpatient drug-free program. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:136–143. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E.C., Robles-Sotelo E., Correia C.J., Silverman K., Stitzer M.L., Bigelow G. The brief abstinence test: effects of continued incentive availability on cocaine abstinence. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:10–17. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.10.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M., Stitzer M.L. Contingent access to methadone maintenance treatment: effects on cocaine use of mixed opiate-cocaine abusers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1993;1:200–206. [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M., Stitzer M.L. Contingent use of take-homes and split-dosing to reduce illicit drug use of methadone patients. Behav. Ther. 1996;27:41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby K.C., Carpenedo C.M., Dugosh K.L., Rosenwasser B.J., Benishek L.A., Janik A., Keashen R., Bresani E., Silverman K. Randomized clinical trial examining duration of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for cocaine abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132:639–645. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W., Hillhouse M., Ang A., Jenkins J., Fahey J. Comparison of behavioral treatment conditions in buprenorphine maintenance. Addiction. 2013;108:1788–1798. doi: 10.1111/add.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier J.P., Heil S.H., Mongeon J.A., Badger G.J., Higgins S.T. A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:192–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S., Nwakeze P.C., Demsky S. RESEARCH REPORT Pre- and in-treatment predictors of retention in methadone treatment using survival analysis. Addiction. 1998;93:51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannelli P., Wu L.-T., Peindl K.S., Gorelick D.A., Wu L.T., Peindl K.S., Gorelick D.A. Smoking and opioid detoxification: behavioral changes and response to treatment. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2013;15:1705–1713. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M.K.K., Johansen S.S., Linnet K. Evaluation of poly-drug use in methadone-related fatalities using segmental hair analysis. Forensic Sci. Int. 2015;248:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peirce J.M., Petry N.M., Stitzer M.L., Blaine J., Kellogg S., Satterfield F., Schwartz M., Krasnansky J., Pencer E., Silva-Vazquez L., Kirby K.C., Royer-Malvestuto C., Roll J.M., Cohen A., Copersino M.L., Kolodner K., Li R. Effects of lower-cost incentives on stimulant abstinence in methadone maintenance treatment: a National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:201–208. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N.M., Martin B. Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine- and opioid-abusing methadone patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2002;70:398–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.2.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N.M., Alessi S.M., Hanson T., Sierra S. Randomized trial of contingent prizes versus vouchers in cocaine-using methadone patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2007;75:983–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry N., Alessi S., Barry D., Carroll K. Standard magnitude prize reinforcers can be as efficacious as larger magnitude reinforcers in cocaine-dependent methadone patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2014;83:464–472. doi: 10.1037/a0037888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling S., Strang J., Gerada C. NICE GUIDELINES: psychosocial interventions and opioid detoxification for drug misuse: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ Br. Med. J. 2007;335:203–205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39265.639641.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast M., Podus D., Finney J., Greenwell L., Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–1560. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01581.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston K.L., Umbricht A., Epstein D.H. Methadone dose increase and abstinence reinforcement for treatment of continued heroin use during methadone maintenance. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2000;57:395–404. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigdollers E., Domingo-Salvany A., Brugal M.T., Torrens M., Alvarós J., Castillo C., Magrí N., Martín S., Vázquez J.M. Characteristics of heroin addicts entering methadone maintenance treatment: quality of life and gender. Subst. Use Misuse. 2009;39:1353–1368. doi: 10.1081/ja-120039392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley R.D., Higgins J.P.T., Deeks J.J. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ. 2011;342 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d549. p.d549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R., Rubin D.B. [Selection models and the file drawer problem]: comment: assumptions and procedures in the file drawer problem. Stat. Sci. 1988;3:120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychol. Bull. 1979;86:638–641. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R. Sage; 1991. Meta-Analytic Procedures for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid C.H. 2016. Outcome Reporting Bias: A Pervasive Problem in Published Meta-analyses. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schottenfeld R., Chawarski M.C., Pakes J.R., Pantalon M.V., Carroll K.M., Kosten T.R. Methadone versus buprenorphine with contingency management or performance feedback for cocaine and opioid dependence. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:340–349. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S., Rotheram-Fuller E., Yang X., Frosch D., Nahom D., Jarvik M.E., Rawson R.A., Ling W. Smoking cessation in methadone maintenance. Addiction. 2002 doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K., Higgins S.T., Brooner R.K., Montoya I.D., Cone E.J., Schuster C.R., Preston K.L. Sustained cocaine abstinence in methadone maintenance patients through voucher-based reinforcement therapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1996;53:409. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830050045007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman K., Wong C.J., Umbricht-Schneiter A., Montoya I.D., Schuster C.R., Preston K.L. Broad beneficial effects of cocaine abstinence reinforcement among methadone patients. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1998;66:811–824. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B.F. Appleton-Century; New York: 1938. The Behavior of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Soyka M., Zingg C., Koller G., Kuefner H. Retention rate and substance use in methadone and buprenorphine maintenance therapy and predictors of outcome: results from a randomized study. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:641–653. doi: 10.1017/S146114570700836X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor O.D. Poly substance use in methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) patients. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 2015;25:822–829. [Google Scholar]

- Umbricht A., DeFulio A., Winstanley E.L., Tompkins D.A., Peirce J., Mintzer M.Z., Strain E.C., Bigelow G.E. Topiramate for cocaine dependence during methadone maintenance treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;140:92–100. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandrey R., Bigelow G.E., Stitzer M.L. Contingency management in cocaine abusers: a dose-effect comparison of goods-based versus cash-based incentives. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:338–343. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.4.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W.L., Campbell M.D., Spencer R.D., Hoffman H.A., Crissman B., DuPont R.L. Patterns of abstinence or continued drug use among methadone maintenance patients and their relation to treatment retention. J. Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46:114–122. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.901587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.