Abstract

Adolescents are the only age group with growing AIDS-related morbidity and mortality in Eastern and Southern Africa, making HIV prevention research among this population an urgent priority. Structural deprivations are key drivers of adolescent HIV infection in this region. Biomedical interventions must be combined with behavioural and social interventions to alleviate the socio-structural determinants of HIV infection. There is growing evidence that social protection has the potential to reduce the risk of HIV infection among children and adolescents. This research combined expert consultations with a rigorous review of academic and policy literature on the effectiveness of social protection for HIV prevention among children and adolescents, including prevention for those already HIV-positive. The study had three goals: (i) assess the evidence on the effectiveness of social protection for HIV prevention, (ii) consider key challenges to implementing social protection programmes that promote HIV prevention, and (iii) identify critical research gaps in social protection and HIV prevention, in Eastern and Southern Africa. Causal pathways of inequality, poverty, gender and HIV risk require flexible and responsive social protection mechanisms. Results confirmed that HIV-inclusive child- and adolescent-sensitive social protection has the potential to interrupt risk pathways to HIV infection and foster resilience. In particular, empirical evidence (literature and expert feedback) detailed the effectiveness of combination social protection particularly cash/in-kind components combined with ‘care’ and ‘capability’ among children and adolescents. Social protection programmes should be dynamic and flexible, and take into account age, gender, HIV-related stigma, and context, including cultural norms, which offer opportunities to improve programmatic coverage, reach, and uptake. Effective HIV prevention also requires integrated social protection policies, developed through strong national government ownership and leadership. Future research should explore which combinations of social protection work for sub-groups of children and adolescents, particularly those living with HIV.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, adolescents, children, HIV prevention, social protection, care and support

Introduction

AIDS-related illness is the leading cause of death amongst adolescents in Eastern and Southern Africa: since 2000, the number of AIDS-related adolescent deaths in the region has tripled (WHO, 2015a). HIV infection poses a serious risk to children and adolescents in the region, with 160,000 new infections annually in this age group (UNICEF-ESARO, 2015). Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA) is also home to 80% of the world's 3.9-4.5 million HIV-positive children and adolescents (Kasedde & Olson, 2012). Investing in social protection in ESA has taken on a new urgency as HIV and AIDS interact with drivers of poverty to disrupt livelihood systems and family and community safety nets (Adato & Bassett, 2009). Children, in particular, are a key constituency for whom it is imperative to scale up and deepen social protection to mitigate the effects of extreme deprivation and vulnerability (E. Miller & Samson, 2012). The expanding evidence base on children and HIV/AIDS has contributed to the progress of the global agenda for improving the health outcomes of children affected by HIV/AIDS.

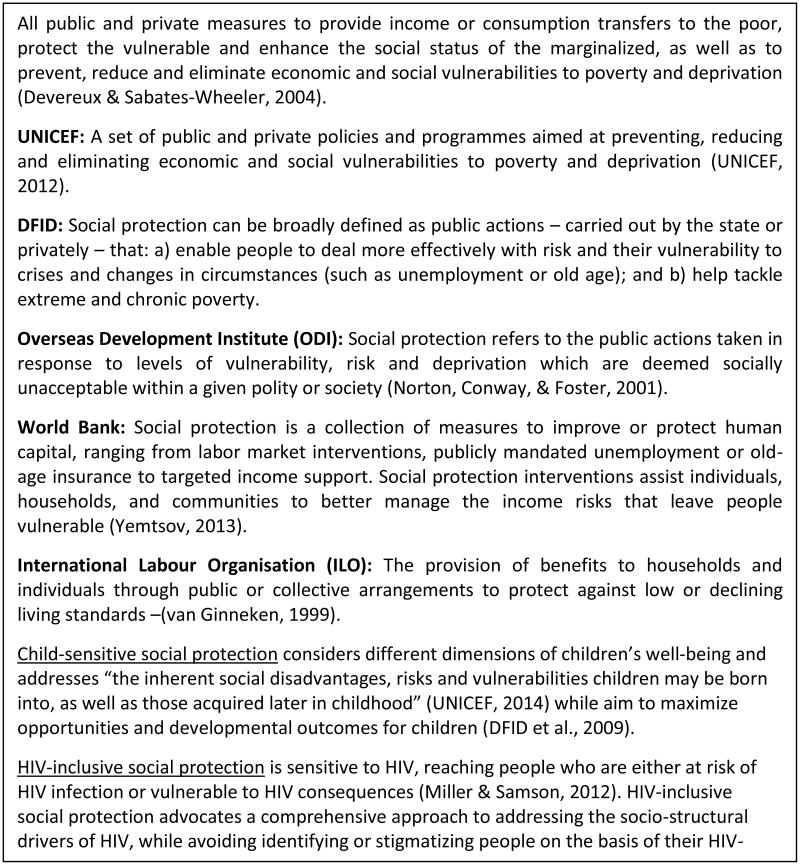

A growing literature investigates the potential that types of social protection have to promote protective behaviours and reduce risk behaviours of children and adolescents affected by HIV (Cluver, Orkin, Yakubovich, & Sherr, 2016; E. Miller & Samson, 2012; UNICEF-ESARO, 2015). This literature points to the importance of improving our understanding of how various modes and forms of social protection support HIV prevention for children and adolescents. This paper aimed to (i) assess the evidence on the effectiveness of social protection for HIV prevention, (ii) consider key challenges to implementing social protection programmes that promote HIV prevention, and (iii) identify critical research gaps in social protection and HIV prevention, in Eastern and Southern Africa. It is guided by a framework that conceptualises that social protection (1) interrupts risk pathways that result in poor health outcomes, and (2) contributes to resilience-enhancing processes in children affected by, and infected with HIV and AIDS in ESA (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Child-sensitive HIV-inclusive Social Protection Conceptual Framework.

Social Protection – Definitions, Conceptual and Policy Framework

Social protection is a highly contested term in the social sciences, with debates about it grounded in complex socio-historical and ideological positions (Devereux & Sabates-Wheeler, 2007). Recently, social protection has been used in the social development literature, and is appearing with increasing frequency in recent policy documents and bilateral commitments (DFID et al., 2009; PEPFAR, 2015; The World Bank, 2012; UNAIDS, 2014c). Despite the recent currency of the term, social protection is not a new concept. In the post-World War II period, social protection provisions became common in Western Europe alongside the idea that the role of the state is to provide for and protect its citizens (Scott, 2012). In response to demonstrated effectiveness, including improved long-term child outcomes, social protection is the foundation of welfare state models in Western Europe (European Commission, 2012; Frazer, 2013), North and South America (Haushofer & Fehr, 2014).

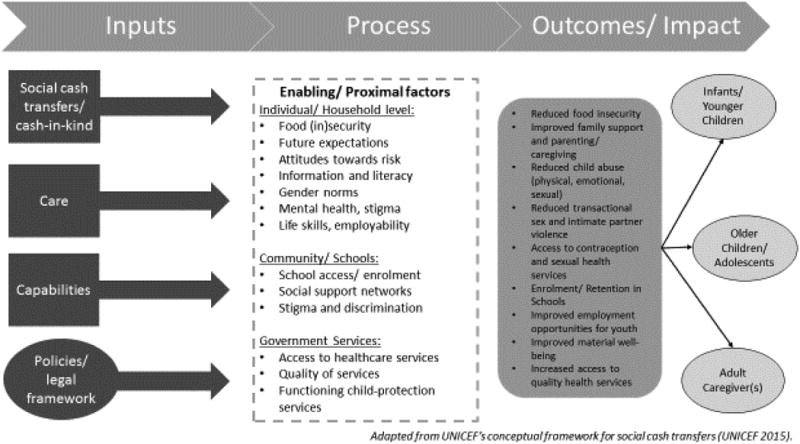

The multifaceted nature of the concept of social protection has resulted in numerous working definitions (Figure 2), all of which share several components: (1) an aim to address key structural vulnerabilities; (2) a focus on reaching the most vulnerable populations through targeted criteria or means testing; (3) delivery by multiple actors including the state, civil society, communities, and private entities alone or in partnerships; (4) a combination of formal (e.g. cash transfers, national feeding scheme), traditional, and informal (e.g. community support and leadership) modalities of delivery; and (5) categorisation of social protection provisions into several key functions. These functions can be summed up into four dimensions of social protection: protective measures which provide relief from deprivation, preventative measures which seek to avert deprivation, promotive measures which aim to enhance real incomes and capabilities, and transformative measures which seek to address concerns of social equity and exclusion (Devereux & Sabates-Wheeler, 2004; Guhan, 1994). The four dimensions of social protection correspond to the main social protection categories which form the conceptual backbone of our research: cash or in-kind interventions (protective), care programmes (preventative), capability-focused initiatives (promotive), and policies and legal environments (transformative) (The African Child Policy Forum (ACPF), 2014). These social protection categories operate at numerous, intersecting levels (UNICEF-ESARO, 2015).

Figure 2. Social Protection Definitions.

While social protection can be viewed as a set of risk-mitigation measures, its relationship to resilience – another multifaceted construct (Shaw, McLean, Taylor, Swartout, & Querna, 2016) – requires further elucidation. A significant portion of research and policies on HIV and children in sub-Saharan Africa focuses on children's victimization and vulnerability, while being neglectful of children's agency, and their acquired life skills (Boyden, 1997; Fassin, 2008; Skovdal & Daniel, 2012). Recent conceptualisations of child agency encourage a move away from narrow definitions of vulnerability and resilience to consider multiple material, social and relational factors that affect the psychosocial well-being of children living at the intersection of poverty and HIV/AIDS (Govender, Reardon, Quinlan, & George, 2014; Skovdal & Daniel, 2012). In particular, an emerging literature calls for increased attention to understanding the potential resilience-enhancing experiences of HIV-affected children and youth living in resource-poor settings (Betancourt, Meyers-Ohki, Charrow, & Hansen, 2013; Skovdal & Daniel, 2012).

However, discussions of child and adolescent resilience are often limited, placing the burden for overcoming adversity solely on the individual (Shaw et al., 2016). This tendency has prompted the call for a multi-level approach to ‘identifying and learning from children's interaction with their social environment as a pathway to resilience’ (Skovdal and Daniel, 2012). This paper's conceptual framework is an adaptation of the United Nations Children's Emergency Fund's (UNICEF) conceptual framework for social cash transfers (Figure 1). It combines Bronfenbrenner's ecological model of human development with the levels across which children access both relational and material support suggested by Skovdal and Daniel (Skovdal & Daniel, 2012). Bronfenbrenner's ecological model of human development conceptualises determinants at multiple levels: micro-system (individual and family-level), meso-system (community-level), exo-system (socio-political, economic and structural factors), and macro-system (interactions among the other levels) (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Lerner, 2005). The social protection conceptual framework applied in this study illustrates how social protection provisions may interrupt single or multiple risk pathways and support resilience in different levels of a child's socio-ecological development: (1) the household; (2) the community, including schools; and (3) the political economy and government services (Skovdal & Daniel, 2012).

Recent changes in the international policy environment recognize the pressing need for innovative and targeted responses to support the health of HIV-positive people and prevent new infections. The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Fast Track Strategy includes targets for increased testing, treatment and adherence by 2030 (UNAIDS, 2014b). The World Health Organization (WHO) recently released guidelines recommending that antiretroviral therapy (ART) be initiated to everyone living with HIV, regardless of CD4 cell count (WHO, 2015b). The Sustainable Development Goals include setting up national social protection systems with a high coverage rate of the most vulnerable populations by 2030i, with HIV as a cross-cutting theme (UNAIDS, 2014a). Social protection commitments are also being included in regional policies such as the Southern African Development Community's “Minimum package of services for orphans and other vulnerable children and youth”.ii These goals and strategies which are shaping the post-2015 health and development agenda recognise that the targets for reducing HIV-related mortality and morbidity can only be met by identifying mechanisms that link structural deprivations with more proximal health outcomes. Short-term responses to mitigating the negative impacts of the HIV epidemic and chronic poverty on children's and adolescents' lives are not effective. Social protection is increasingly receiving recognition as an important part of a comprehensive response HIV/AIDS response because of its potential to address structural deprivations. At this critical junction, it is crucial to undertake a review of the evidence on child-and adolescent-sensitive social protection for HIV prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa.

Methods

Two research methodologies were combined to summarise and assess the existing evidence on child- and adolescent-sensitive social protection for HIV-prevention in Eastern and Southern Africa: (1) A rigorous review of academic, policy and grey literature on social protection, children and adolescents in Eastern and Southern Africa; and (2) Consultations with 25 experts from a variety of national, regional and international institutions and research bodies.

The rigorous literature review consisted of two components: (i) a systematic review of intervention studies, and (ii) a desk review and mapping of policies from Southern and Eastern Africa. Systematic Review: Peer-reviewed articles in OVIDSp and EBSCOhost were systematically searched using key terms for social protection, children and adolescents, and HIV/ AIDS (Table 1). Social protection was conceptualized broadly to include as many of the possible interventions and components that may fall under this umbrella term. We conceptualised the outcome – HIV prevention – as either prevention of acquiring HIV for HIV-negative people or preventing the onwards transmission of HIV – prevention for positives, an extension of recent reviews of the evidence of social cash transfers (UNICEF-ESARO, 2015). We scanned 905 titles and abstracts for review, 15 of which were reviewed full-text. 11 were included in this manuscript. Hand searches resulted in an additional 13 publications. Only publications on the efficacy or effectiveness of social protection interventions were included in the final full-text reviews. Evidence from national, regional or local programmes, and proof-of-concept/ intervention studies were included, as long as primary data (qualitative of quantitative) was used to assess the effectiveness of one or multiple social protection provisions.

Table 1. Search terms and strings used in OvidSP.

| String | Category | Concept | Search terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Population | Adolescents and children | (((HIV or AIDS or ((human or acquired) adj1 (immunodeficiency or immune-deficiency or immuno-deficiency))) adj2 (child* or adolescen* or teen* or you*)) or ALHIV or PHIV or BHIV).ab,ti,kw. |

| HIV-positive | |||

| 2 | Programmes | Social Protection | (Social Protection OR Safety net OR Welfare OR Social assistance OR social security OR Social benefit).ti,ab,kw. |

| 3 | Cash | (School feeding OR Cash Transfer OR Grant OR Voucher OR Food OR Money Transfer OR Fund* Transfer OR Payment OR Reimbursement OR Airtime OR Uniform OR School fee OR Financial instrument OR Microfinance OR Employment OR Work OR Bursary OR Cash OR Money).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 4 | Care | (Social support OR parent* OR caregiver OR psychosocial support OR teach* support OR Health work* OR Counsellor OR Counselor OR Care Work* OR Home visits* OR Treatment support OR Adherence support OR Treatment buddies OR Treatment buddy OR Peer support* OR Peer educator OR After-school OR Support groups OR Learner support OR Student OR Care).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 5 | Social protection strings | 2 OR 3 OR 4 | |

| 6 | Final: SP & Adolescents | 1 AND 5 |

Policy mapping and grey literature review

This systematic review was complemented by a parallel review of policies and formal documents of international organisations: UNICEF, UNAIDS, WHO, the World Bank; regional organisations: African Union, Southern African Development Community, East African Community); and national ministries and institutions for key countries in Eastern and Southern Africa. Based on HIV prevalence rates and numbers of children/ adolescents living with HIV, we conducted in-depth searches for policies and programmes in three East African countries: Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya, as well as three Southern African countries: Malawi, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. Additional unpublished documents on social protection interventions and policies were identified through expert consultations.

Consultations with policy-makers and programmers

With the support of the Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Inter-Agency Task Team on Children Affected by AIDS's (RIATT-ESA) Social Protection working group, we identified experts on social protection at international, regional and national levels. We interviewed twenty-five of these stakeholders about their national and regional experiences in designing implementing and evaluating social protection interventions. Interviews were transcribed and manually coded. From this coding, themes were identified, reviewed and defined. Findings from the literature review and expert consultations were largely complimentary, and are presented together throughout the results and discussion section.

Results

Social Protection Programmes: Cash, Care, and Capabilities

Our literature review identified 22 peer-reviewed and grey-literature publications highlighting evidence to date on 20 social protection programmes and initiatives (Table 2). The body of knowledge on social protection for HIV prevention consists of two types of evidence: (1) effectiveness trials or intervention studies and (2) analysis of national-level programmes. In total, our findings located 18 pilot or effectiveness/ intervention trials (eight randomized controlled trials (RCT), five quantitative surveys, two pre-post pilot studies, and three qualitative), and 3 national-level programmes (one RCT, two quantitative analysis) for which there is evidence for outcomes linked to HIV prevention among children and adolescents in Eastern and Southern Africa. The located studies evaluate all the categories of social protection: four programmes evaluated cash-only social protection, seven care-only interventions, while eleven reviewed combinations of social protection: four cash-plus-care,iii three care-plus-capability, two cash-plus-capability, and one of three categories of social protection: cash-plus-care-plus-capability. Seven studies of care-only interventions included HIV-positive children and adolescents: two pre-post pilot studies (Bhana et al., 2014; Snyder et al., 2014), two mixed methods studies (Lightfoot, Kasirye, Comulada, & Rotheram-Borus, 2007; Webster Mavhu et al., 2013), and three qualitative studies (Parker et al., 2013; Senyonyi, Underwood, Suarez, Musisi, & Grande, 2012; Willis et al., 2015).

Table 2. Summary of Evidence on Social Protection for HIV Prevention.

| Citation/ Publication |

Status | Social Protection Intervention |

Type | Country | Age Group | Methodology & Sample size |

Outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ssewamala 2013, 2014 | 2013 - On-going | Cash – youth-focused grants Capability – economic empowerment approach |

Pilot/ intervention study | Uganda | 10-16 years old | RCT, n=736(est.) | HIV treatment adherence Psychosocial functioning Sexual risk-taking |

On-going trial |

| Pettifor 2015 | 2013-2015 | Cash –CCT on School attendance (HTPN 068) | Pilot/ intervention study | South Africa | 13-20 | RCT, n=2,523, women | HIV Prevalence, School attendance | No difference in new HIV infections, reduced risk behaviours |

| Baird 2012 | 2008-2009 | Cash – CCT and UCT (Zomba trial) | Pilot/ Intervention Trial | Malawi | 13-22 | RCT, n=2,915 | HIV infection (incidence) | Both CCT and UCT to girls reduce likelihood of HIV infection by about half. |

| Bandiera 2013 | 2008- 2010 | Care – life skills Capability – vocational training |

Pilot/ Intervention Trial | Uganda | 14-20 | RCT, n=4,800 | Risky behaviours (unprotected sex), knowledge about HIV and pregnancy prevention, unwilling sex | Self-reported routine condom usage increases by 50%, 26% drop in fertility rates over two years, and from baseline 21%, near elimination of unwilling sex. |

| Hallfors 2011, 2014 | 2007- 2010 | Cash – school fees, uniforms, and school supplies Care – school-based “helper” |

Pilot/ Intervention Study7 | Zimbabwe | 10-16 at baseline | RCT, n=329 (baseline) 287 (5-year follow up) Female adolescent orphans only |

Sexual debut, ever married, school dropout, years of schooling, meals per day, HIV HSV-2 biomarkers | no difference in HIV, HSV-2 biomarkers. Intervention group reduced sexual debut, marriage, or pregnancy, less likely to drop out of school and almost one additional year of schooling. |

| Karim 2015 | 2010-2012 | Care – lifeskills program Cash – conditional transfer (Caprisa 007) |

Pilot/ intervention study | South Africa | 15-16 | RCT, n=3,217 | HSV, HIV | Incentives conditional on participation in life skills program reduced HSV but not HIV. |

| Duflo 2011 | 2003-2006 | Cash – School uniforms on condition of being enrolled in school (CCT) Capability – teacher training |

National programme impact evaluation | Kenya | 11 - 16 (and some older due to grade repetition) | 4-arm RCT with 7-year follow-up, n=19,000 | Fertility, School Attendance, marriage rate, HIV and HSV-2 prevalence | 18% reduction in school dropout rate across cohort. For girls, significant reduction in teen pregnancy and teen marriage but no reduction in risk of STI. No reduction in HIV and HSV-2. |

| Cho 2011 | 2008-2009 | Care – “community visitor” to monitor school attendance Cash – UCT (School fees, uniforms) |

Pilot/Intervention Trial | Kenya | 12-14 | Pilot RCT, n=105 | School enrolment, age of sexual debut, attitudes about early sex | Control more likely than intervention group to: Drop out of school (12% vs 4%) and begin sexual intercourse (33% vs 19%) and report attitude supporting early sex. |

| Dunbar 2014 | 2006-2008 | Care – social support Cash – UCT Capability – life-skills and health education, vocational training, micro-grants |

Pilot/ intervention study | Zimbabwe | 16-19 | Pilot RCT, n=315 | Food insecurity, risky behaviour, fertility | Intervention arm showed reduced food insecurity [IOR=0.83 vs. COR=0.68, p=0.02], having own income [IOR=2.05 vs. COR=1.67, p=0.02] lower risk of transactional sex [IOR=0.64, 95% CI (0.50, 0.83)], and increase condom use with partner [IOR=1.79, 95% CI (1.23, 2.62)] and fewer teen pregnancies [HR=0.61, 95% CI (0.37, 1.01)] |

| Cluver 2013 | 2009 - 2012 | Cash – child-focused cash transfers both UCT and CCT comparison | National programme impact evaluation | South Africa | 10-18 | Quantitative, n=3,515 | Risky Behaviour | Reduced incidence of transactional sex amongst girls (odds ratio [OR] 0·49, 95% CI 0·26–0·93; p=0·028), and age-disparate sex (OR 0·29, 95% CI 0·13–0·67; p=0·004). No significant effects for boys. |

| Cluver 2014, 2016 | 2009 - 2012 | Cash alone UCT – child-focused grants, free school Cash + care – cash transfers, free schools, parental support |

National programme impact evaluation | South Africa | 10-18 | Quantitative, n=2,515 | Risky Behaviour | Girls: Economically driven sex incidence in last year dropped from 11% (no intervention) to 2%.(intervention). Unprotected/casual sex dropped from 15% (no intervention) to 10% (either parental monitoring or school feeding) and to 7% (with both PM and SF). |

| Handa 2014 | 2007-2011 | Cash – UCT | National programme impact evaluation |

Kenya | 15-24 | Quantitative, n=1,540 | Sexual debut | Reduction in likelihood of sexual debut by 23% among young people. |

| Kauffman 2010 | 2002- On-going | Care – sports based programmes Capability – life skills |

National programme impact evaluation | Zimbabwe Botswana |

15-19 | Quantitative, n=553 | Risky Behaviour, sexual debut | No differences in sexual debut; Sexually active participants had fewer sexual partners. |

| Mahvu 2013 | Aug-Sept 2009 | Care - Support Group | Pilot/ intervention study | Zimbabwe | 6-18 | Mixed-methods, n=229 | Mental Health, Risky behaviour | Support group attendance is helpful, young people stressed that life outside the confines of the group was more challenging |

| Lightfoot 2007 | 2003-2004 | Care – one-to-one sessions with nurse | Pilot/ intervention study | Uganda | 16-24 | Mixed-methods, n=100 | Risky behaviour | Intervention decrease in number of sexual partners (3.1 at baseline to 0.7 at follow up ) Condom use increased from 10% at baseline to 93% at follow up in intervention |

| Visser, Zungu, Ndala-Magoroa 2015 | 2003- On-going | Care – Home visits and family support, personal guidance and counselling, empowerment programme, access to health care and treatment Capability – Help with study programme/homework, help with further education and training, bursary application, job skills, career guidance, life skills training |

Post-programme impact evaluation | South Africa | <18 | Mixed-methods N=427 OVC participants over 18 who had previously been project beneficiaries (70% for over a year) |

HIV risk, educational attainment, self esteem, family support, employment, income | Higher self-esteem and problem-solving abilities. Improved family support. Less reported HIV risk behaviour (men -binge drinking 12.3% vs. 30.6% for control group. Women - fewer unwanted pregnancies – 28.8% vs. 37% for control group.women) No difference in education levels. Higher employment (20.8% vs. 11.5% in control group). Financially somewhat advantaged (45.5% vs. 28.7% in control group). More optimistic about future opportunities (70.5% vs. 56.3%). |

| Bhana 2015 | 2012- On-going | Care – Family-based psychosocial intervention | Pilot/ Intervention Trial | South Africa | 10-14 | Pre-post pilot study, n=65 | Mental Health, Knowledge about HIV, Stigma, sexual risk-taking | Trial on-going. |

| Snyder 2014 | 2009 | Care – structured support group - Hlanganani | Pilot/ intervention study | South Africa | 16-24 | Pre-post RCT, n=109 | adherence to ARVS, increase Knowledge of HIV and promote better SRH practise amongst adolescents | Condom use at last sex rose from 71% to 83% at follow-up. Linkage to care 100% of all ART eligible participants (n=13), compared to 58% in comparison (n=31). |

| Parker 2013 | 2012 | Care – support groups (SYMPA) | Pilot/ intervention study | DRC | 15-24 | Qualitative, n=13 | Communication with significant other, risky behaviour, knowledge about HIV | Reduction in sexual risk taking and improved ability to negotiate safer sex. Participants also reported feeling more comfortable speaking with care-giver about sex |

| Senyonyi 2013 | 2011 | Care – Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, support groups | Pilot/ intervention study | Uganda | 12-18 | Qualitative, n=171 | Sexual risk-taking Mental health |

No change in depression. Reduction in sexual risk taking reported. |

| Willis 2015 | On-going | Care – Zvandiri programme: Theraputic digital story telling | Pilot/ intervention study | Zimbabwe | 14-16 | Qualitative, n=12 | Improved psychosocial well-being | Improved communication with caregivers reported, acquisition of digital media skills, feeling of empowerment |

Our findings complement the detailed analysis of social cash transfers prepared by The Transfer Project (UNICEF-ESARO, 2015) and a recent mapping of social protection programmes by the United Nations Development Programme (Cirillo & Tebaldi, 2016). This article focuses on evidence-based social protection programmes and policies that help HIV-negative children and adolescents to stay healthy, but also those preventing HIV-positive children and adolescents from transmitting HIV. While there is limited evidence on how social protection directly impacts HIV prevalence and incidence (E. Miller & Samson, 2012), a growing body of research shows that social protection can reduce sexual practices such as early sexual debut, unprotected sex, early pregnancy, dependence on men for economic security, transactional sex, school dropout, food insecurity, early marriage and economic migration (Lutz & Small, 2014; UNAIDS, 2014c; UNICEF-ESARO, 2015). Studies suggest a few – potentially overlapping – mechanisms through which social protection may causal pathways to HIV infection: (1) poverty reduction and economic development (Gillespie, Kadiyala, & Greener, 2007; Mishra et al., 2007; Nattrass & Gonsalves, 2009), (2) the role of schools (A. E. Pettifor et al., 2008; UNAIDS, 2014c; UNICEF-ESARO, 2015), (3) improved food security (Cluver, Toska, et al., 2016; Emenyonu, Muyindike, Habyarimana, Pops-Eleches, & Thirumurthy, 2010), and (4) improved psychosocial outcomes (Govender et al., 2014). A detailed analysis of the mechanisms of social protection is beyond the scope of this article, however, one substantive contribution of this article is that it summarises the burgeoning evidence base on social protection as a critical enabler for HIV prevention outcomes (Baird, Garfein, McIntosh, & Ozler, 2012; Lutz & Small, 2014; UNAIDS, 2014c).

Social Cash Transfers

Amongst evaluations of cash transfers for HIV prevention located in this study, only one found a reduction in HIV prevalence (Baird et al., 2012), with others finding no difference in HIV infection rates (Duflo, Dupas, & Kremer, 2011; Hallfors et al., 2015; Karim, 2015; A. E. Pettifor, Macphail, & Kahn, 2009). The lack of evidence for reduced HIV incidence could be due to studies being statistically under-powered, very low HIV incidence rates in younger adolescents, or because the impact of reduced HIV-risk behaviours only affect HIV incidence later in adolescence (Duflo et al., 2011; Hallfors et al., 2015; Karim, 2015; A. E. Pettifor et al., 2009). One study found reductions in HSV-2 incidence (Karim, 2015), which is a strong marker for HIV incidence (Freeman et al., 2006).

Cash transfers as a form of social protection have received significant attention, resulting in a copious literature about their efficacy (Cluver et al., 2013; Handa, Halpern, Pettifor, & Thirumurthy, 2014; A. E. Pettifor et al., 2009), so will not be discussed in detail in this article. Among trials and evaluations of the effect of social cash transfers on HIV-risk behaviours, ten studies found reductions in sexual risk-taking, three improved educational outcomes, one documented reduced food insecurity, and three improved mental health, stigma and psychosocial support. As these high-risk sexual behaviours have been linked with increased HIV incidence, the evidence on social protection for HIV prevention among HIV-negative children and adolescents is encouraging. These findings confirms that there is a critical mass of evidence to show the impact of social cash transfers on the impacts of HIV and AIDS, although the quality and strength of this evidence varies.

Care Social Protection Provisions

Research and programming to-date has documented several additional mechanisms of social protection beyond cash transfers. ‘Care’ programmes – particularly those focusing on strengthening families and supporting caregivers – have had significant results on outcomes proximal to reduced HIV infection (Chandan & Richter, 2008; Cluver, Orkin, Boyes, & Sherr, 2014; Sherr et al., 2014; Visser, Zungu, & Ndala-Magoro, 2015) suggesting that care and psychosocial support should be an integral component of HIV prevention efforts. Our study located several ‘care-only’ or ‘care-plus’ social protection programmes which reduced HIV risk taking: family-based interventions in South Africa (Bhana et al., 2014; Visser et al., 2015), one-on-one counselling for adolescents and youth (Lightfoot et al., 2007), and peer-driven or group-based interventions (W Mavhu et al., 2010; Parker et al., 2013; Senyonyi et al., 2012; Snyder et al., 2014; Willis et al., 2015). Given that most of the above studies were small-scale pilots, evidence from larger scale interventions is needed, including studies that include HIV incidence as an outcome. That non-cash social protection mechanisms require greater recognition for their potential for HIV-prevention among children and adolescents (Chandan & Richter, 2008) was also a strong finding from expert consultations:

‘The acknowledgement of care and support needs to be more explicit. We talk about interventions that many wouldn't see as social protection, that are social protection… (the term ‘social protection’) it is so closely associated with cash… I think we need to reclaim … care and support.’

(Expert consultation, International not-for-profit organization employee)

‘As budgets have gotten more constrained and when the strategic investment framework was produced, everything needed to be evidence based. Care and support dropped down into development synergies from key interventions… We haven't heard enough about psychosocial support… We have heard plenty on cash… we are still missing the glue that holds it all together which is the carers and care giving structures… I fear that with cash, you can put it into the household, but you don't necessarily support the caregiver… this is what is needed alongside cash. These caregiving mechanisms are critical to ensure that care and support is delivered successfully.’

(Expert Consultation, International not-for-profit organization employee)

‘(A social protection programme) might provide cash, but if families aren't cognizant of other needs that children have, the cash may not have as much of an impact. Children must feel loved, cared for, belonging.’

(Expert Consultation, Regional not-for-profit organization employee)

These findings suggest that the potential of ‘care’ social protection mechanisms extend beyond ameliorating the impact of ‘cash’ interventions. ‘Care’ social protection may have positive impact in three separate, inter-related ways. First, ‘care’ directly benefits the intended beneficiaries as stand-alone interventions or in combination with ‘cash/in-kind’ provisions. Secondly, ‘care’ interventions act as flexible mechanisms that can buffer and respond to the complex and shifting needs of HIV-vulnerable children and adolescents. Thirdly, through their flexibility and responsiveness, ‘care’ social protection may act as glue for the sustained uptake and retention of other forms of social protection. Practical examples of such interventions include systems that address the needs of vulnerable children and adolescents through referrals and psychosocial support and programmes that support caregivers, which also act as gateways to other forms of social protection. This finding dovetails with a growing body of qualitative literature that supports the design and delivery of psychosocial support and ‘care’ interventions (Campbell et al., 2012; Govender et al., 2014; Winskell, Miller, Allen, & Obong'o, 2016). The current momentum around the delivery of ‘cash’ and ‘cash-plus’ combinations of social protection provisions offers opportunities for documenting the potential of ‘care’ interventions:

‘… there is such momentum for cash… we must (use this momentum) to encourage the delivery of care and address the policies, norms and processes that are stigmatizing, that are excluding… We are beating the drum for cash transfers to be more effective and functional.’

(Expert consultation, International not-for-profit organization employee)

Capability Social Protection Provisions

An emerging category with several promising completed trials and a few underway is that of ‘capability’ social protection provisions, which focus on long-term transfer of skills and knowledge that addresses structural inequalities faced by children and adolescents. ‘Capability’ social protection refer to any intervention delivered under the promotive function of social protection (Devereux & Sabates-Wheeler, 2004). Three recent trials that involved ‘capability’ social protection in the form of life skills training combined with cash transfers had promising results in reducing HIV-risk behaviour (Duflo et al., 2011; Dunbar et al., 2014; Karim, 2015). Though the content of ‘capability’ varied by intervention from teacher training to life skills support for adolescents, these findings suggest that extending social protection interventions to include promotive elements, such as capability development, is crucial for building long-term resilience amongst children and adolescents. This finding was supported by the expert consultations, in which ‘capability’ interventions were an important theme:

‘Building self-esteem and life skills is important. It makes sure that we are empowering the child and adolescent to be able to live in this world. They must be empowered to effectively communicate, negotiate and effectively seek services. […] (Social protection) models should look at experiential learning that empowers children to access services.’

(Expert Consultation, Regional not-for-profit organization worker)

Combination Social Protection

Growing evidence demonstrates that combinations of social protection, particularly ‘cash-plus-care’ have greater potential for HIV prevention among children and adolescents than cash interventions alone (Bandiera, Buehren, Burgess, Goldstein, & Gulesci, 2013; Cho et al., 2011; Cluver, Orkin, et al., 2016; Duflo et al., 2011; Karim, 2015). Social protection interventions consisting of multiple components have additive, and potentially multiplicative effects on HIV prevention (Cluver, Orkin, et al., 2016) and are necessary to meet the complex psychosocial needs of HIV-positive children and adolescents, as well as those vulnerable to infection (Amzel et al., 2013; Cluver, Toska, et al., 2016). The shift towards combinations from single forms of social protection has emerged from two complementary movements: increased evidence on the effectiveness of combined social protection interventions, and an adapted conceptualization of the compounded pathways to risk and vulnerability for HIV infection.

Social protection provisions may work better in combination by addressing the multiple vulnerabilities and contextual barriers faced by those most at risk of HIV infection. For example, adolescent girls receiving a combination of an unconditional cash transfer, social support and life skills training in Zimbabwe reported higher income, reduced food insecurity, and less transactional sex or unwanted pregnancies (Dunbar et al., 2014). Recent findings from a longitudinal survey in South Africa also suggest that certain combinations of social protection provision are linked to reduced HIV risk incidence amongst adolescent girls (Cluver, Orkin, et al., 2016).

‘The importance of deliberate, politically-backed and sustainable combinations of child-sensitive social protection mechanisms cannot be overstated.’

(Expert Consultation, Regional not-for-profit organization worker)

However, the evidence is not conclusive on which specific social protection provisions are best for HIV prevention and suggests that different combinations work for adolescent girls and boys under different circumstances (Cluver, Orkin, et al., 2016; Handa et al., 2014). Combinations, including ‘cash-plus-capability’, or multiple types of care combined also hold great potential and merit further exploration.

‘Various interventions are necessary… think about the alignment between… psychosocial support, family care, and the interventions that go with those… comprehensive care and support … cash is a core, plus various care interventions if (we want to) have a bigger impact on the broader goals that we are working for…. it must be applied and provided with psychosocial support and care of a range of elements.’

(Expert Consultation, International not-for-profit organization worker)

Social Protection Policy Implementation

The most effective social protection policies cannot be implemented in the absence of an enabling environment, including the programmatic and fiscal support of states (Devereux & Sabates-Wheeler, 2004). Transformative social protection (that is, enabling legal and normative environments) is essential for the delivery of other social protection mechanisms, as well as to address issues, such as stigma, that drive exclusion and create barriers to uptake. An enabling legal environment is needed to ensure that the Fast Track goals, which focus on increasing reach of existing services, are attainable by 2030. International and regional directives on social protection, as well as those on HIV prevention and treatment provide a rhetorical framework for the delivery of child-sensitive social protection for HIV prevention:

‘Transformative social protection is intended to address the drivers of exclusion…’

(Expert Consultation, International not-for-profit organization worker and academic)

‘Transformative social protection… and social policy reform is talked about less (than other forms of social protection) but has the opportunity to address the root causes of vulnerability and exclusion… it is necessary to have policies and laws that extend to social norms which exclude people… some of these prevent people from accessing the cash and accessing a whole range of services… the opportunity is to use social protection to actually ensure that marginalized groups are included requires transformative social protection. Structural environments must be conducive for other forms of social protection to work.’

(Expert consultation)

These relatively new directives pose a great opportunity and also raise questions regarding the interpretation and implementation of such lofty and ambitious initiatives. What form such initiatives should take, and how they should be targeted, funded and delivered are all highly contested (e.g. Mkandawire, 2005; UNRISD, 2010; World Bank, 2012).

Numerous African states have an established history of social protection, including cash transfers and in-kind interventions such as school feeding programmes and emergency food aid (Seekings, 2007). There has been a progressive expansion in the use of unconditional cash transfers on the continent since the 1990s, which have become a critical instrument of many social development and poverty reduction strategies (UNICEF-ESARO, 2015). Approximately 17 million cash transfers are provided in South Africa and transfer programmes are being scaled up in other Eastern and Southern African countries (Adato & Bassett, 2009; GroundUp, 2015).

Our in-depth analysis of six countries in Eastern and Southern Africa demonstrates a high level of variation between domestic policy environments and provisions for various social protection mechanisms. Such variety speaks to the unique social protection needs, resources and policy and legislative frameworks, as well as perhaps uptake and political buy-in. Most of the documents that included specific social protection components (cash, care, capabilities, or combinations) were strategies focusing on specific vulnerable sub-groups such as orphans and vulnerable children (OVC), as seen in Kenya and Lesotho. Few policy documents acknowledge the direct role that social protection may play in HIV prevention by supporting safe sexual health behaviours for older children/ adolescents.

There are several lessons that can be gleaned from national-level policy implementation in Eastern and Southern Africa. First, to reach those most structurally-vulnerable, good targeting strategies or means-tested provisions (such as for the child support grant in South Africa) are needed. Second, knowledge of the unique vulnerabilities of children and adolescents are key to the success of health and social support interventions. National policies that targeted HIV-affected households have negative impacts, whereas those that combine long-term vulnerabilities such as orphanhood with poverty have had greater impact (Handa & Stewart, 2008; Schuring, 2011). Third, good targeting does not result in good reach. A better understanding of inclusion and exclusion errors of current targeting strategies is needed (E. Miller & Samson, 2012). Finally, social protection policy processes that evolve out of (or are adapted to) domestic political agendas and respond to local conceptualizations and prioritizations of need are more likely to succeed—in terms of their coverage, fiscal sustainability, political institutionalization, and impacts—than those that are based on imported from elsewhere.

Discussion

A series of issues regarding the roll-out and sustainability of social protection mechanisms emerged from the triangulation of expertise consultations with a review of policy and literature on social protection. This section highlights issues of targeting, flexibility and conditionality, and considers the feasibility and barriers to social protection policies and interventions for HIV prevention for children and adolescents in Eastern and Southern Africa.

Targeting and Flexibility

One of the ways that social protection mechanisms reach the most vulnerable is through targeted inclusion and exclusion criteria to ensure that scarce resources are used efficiently (Slater, Farrington, Samson, & Akter, 2009). In order to ensure that targeting is effective and to minimize harmful unintended consequences, targeting criteria and methods should be transparent and clearly communicated (UNICEF, 2015). Finding HIV-inclusive eligibility criteria that do not stigmatise beneficiaries is challenging, though some examples include gap-generation households and child-headed households (Schuring, 2011). Targeting that focuses on the poorest families with children has the greatest impact on orphans and vulnerable children (Handa & Stewart, 2008). Though not focused on children or adolescents, qualitative evidence from Malawi demonstrates that targeted Social Cash Transfers reached HIV-positive people who were able to use the income to improve adherence to ART (Miller & Tsoka, 2012), which is key to reducing HIV infectiousness (Rodger et al., 2014).

However, targeting may result in high inclusion and exclusion bias due to various contextual factors such as stigma and discrimination, lack of knowledge/ agency in accessing grants, limited ability to administer resource-heavy conditional programmes, and poor communication about inclusion/exclusion criteria (including criteria rationale). Additionally, targeting strategies may be expensive. Additional research is needed on effective targeting practices that respond to localised knowledge of the HIV epidemic and the specific vulnerabilities of children and adolescents. HIV-related stigma and discrimination as a result of targeting can overshadow needs of other vulnerable children.

A central finding of this research was that social protection mechanisms must be flexible to respond to the fluid and dynamic realities and needs of children and adolescents. Common shocks to children and adolescents that may render them further vulnerable include changes to living environments through political and natural events, moving, losing caregivers and grief, as well as other situational factors (Amzel et al., 2013; Chandan & Richter, 2008; Richter et al., 2009; Vale & Thabeng, 2015). In recognizing the unique, rapidly changing and often volatile situations and needs of adolescents, it is important to ensure that social protection mechanisms are flexible and dynamic enough to provide the appropriate support that is fundamental for HIV-prevention among this vulnerable group. As significant administrative and bureaucratic infrastructure has to be created to disburse and manage social cash transfer programmes, they provide a crucial entry point to reach those most vulnerable with multiple social protection provisions, including ‘cash-plus’ combinations. Combinations of social protection that include ‘care’ components can offer the flexibility necessary to addressing the realities in which HIV-vulnerable children and adolescents live.

Flexibility of social protection mechanisms is key to their effectiveness in adapting to young people's needs as they transition from childhood to adolescence. This theme was born out from expert consultations:

‘Social protection should be very dynamic to adapt to the evolving needs that children may have… the stagnant nature of some social protection mechanisms mean that they can't adapt to the needs of young people as they go through adolescence… There is a current failure to adapt to children and their evolving needs.’

(Expert consultation, academic)

Unfortunately, social protection provisions that address issues of sexual and reproductive health often perceive young people as children: sexually naïve until they become pregnant or contract HIV through sexual relationships.

Conceptually treating childhood and adulthood as two mutually exclusive life stages is limiting and ‘hugely misses the point of adolescence… Social protection that perceives young people as children until evidence to the contrary, for example when they become pregnant, is not dynamic enough to be effective in terms of prevention… Social protection needs evolve and vary for individuals as they grow up: there is a vacuum between paediatric and adult care… treating people as children and then adults is inadequate and doesn't reflect their needs and experiences.’

(Expert consultation, academic)

A common theme from expert consultations was that age is an important (and sometimes overlooked) consideration in the conceptualization, design and provision of child and adolescent sensitive, HIV-inclusive social protection. Though the needs of children (0-15 years old) and adolescents (10-19 years old) vary by socio-economic and family factors, age plays an important role in their vulnerabilities, and also their ability to access and benefit from various social protection mechanisms. Younger children are likely to access social protection mechanisms for HIV prevention through caregivers and households, for example, in the case of cash transfers to mothers. Older children and adolescents, on the other hand, should be targeted and receive social protection provisions directly (UNICEF-ESARO, 2015). Programmes that focus on caregivers have greater effect and reach for younger children however, older adolescents may find that programmes focusing on the home/ caregivers do not match their expectations (Busza, Besana, Mapunda, & Oliveras, 2014).

Conditionality

Some social cash transfer programmes are conditional, whereas others, including many in Africa are unconditionaliv. There are essentially two types of conditional programmes, those that are conditional on avoiding undesirable sexual health outcomes, such as HIV- infection, sexually transmitted infections or adolescent pregnancy and others that aim to encourage protective health behaviours such as retention-in-care and immunizations. The former category is based on the premise that risk is driven by rational behaviour choices (de Walque et al., 2012), and has raised serious ethical considerations (Cluver, Hodes, Sherr, et al., 2015). The latter category is less concerning, although efforts must be made to ensure that the most vulnerable families do not ‘slip through the net’ because they are unable to meet the requirements. The Zomba trial in Malawi is the only evidence to date that both conditional and unconditional cash transfers among adolescents worked in reducing HIV prevalence (Baird et al., 2012). However, there was no significant difference in HIV prevalence amongst the groups receiving the unconditional and conditional cash transfers. Neither of the two recent trials of conditional cash transfers showed results on reducing HIV incidence (Karim, 2015; A. E. Pettifor et al., 2009). National-level conditional cash transfers such as the Malawi and Zambian cash transfer schemes – conditional upon children enrolment in school and vaccinations – have had more encouraging results (Schuring, 2011). Given the costs of administering a conditional social protection scheme, particularly at a national level, further research is needed to discern whether it is the cash transfer in itself or the conditionality that makes the difference. Experts consulted expressed a strong preference for unconditional cash transfers, for a variety of reasons including perceptions of effectiveness, stigma and discrimination:

‘There is a body of evidence that suggests that unconditional cash transfers tackle vulnerability in important ways while also building human capital in ways that improve capacity and that address vulnerabilities in early childhood, adolescence and into early adulthood. This is important to supporting the health and well-being of vulnerable young people.’

(Expert Consultation, academic and international not-for-profit organization worker)

Stigma must also be an important consideration in the delivery of conditional cash transfers. ‘Stigma and discrimination can exclude households and adolescents from getting a whiff of the cash… and a whole range of services.’ (Expert Consultation, International not-for-profit organization worker). Simply accessing services can be stigmatizing, which is one of the core arguments for the delivery of HIV-inclusive, rather than HIV-specific social protection. Additionally, social protection targets should include those who most need services, and that these in turn will include those both at risk, and living with HIV: ‘Conditional transfers can be discriminatory. We want to see systems that are built on a universal approach….’ (Expert consultation, international not-for-profit organization worker). This approach therefore appreciates that, at times, one needs to deliver specific services to children who are HIV-positive and in need of medical services and psychosocial support.

Feasibility and barriers to ensuring effective implementation and uptake of social protection for HIV prevention

The World Bank State of Safety Nets 2015 report, which looked at social assistance in 120 developing countries, indicates that well-designed social assistance programmes are cost-effective, costing between 1.5 and 1.9% of gross domestic product (The World Bank, 2015). In Sub-Saharan Africa, social assistance currently covers just one-tenth of the poorest 20% (The World Bank, 2015). Estimates of the reach of non-cash social protection initiatives are not available. The expansion of social protection provisions is possible for most African countries (Garcia & Moore, 2012). Such initiatives are not only an investment for the health and wellbeing of children and adolescents, but also a long-term cost-saving mechanism by nature of avoidance of negative future outcomes and the realization of long-term savings (Remme, Vassall, Lutz, Luna, & Watts, 2014; Sherr et al., 2014). Budgetary commitments for social protection can be made more manageable by co-financing from multiple government departments, as demonstrated by the STRIVE consortium (Kim, Lutz, Dhaliwal, & O'Malley, 2011; Remme et al., 2014). Further cost analysis of existing successful social protection initiatives is needed to support governments in deciding where to invest their social protection funding (E. Miller & Samson, 2012).

Complex challenges such as HIV prevention among children and adolescents require combinations of well-integrated interventions. Silo-based approaches to policy making and implementation can fail to capitalise on the additive effects of combinations of social protection interventions. Just as combinations are required at a programmatic level, from a policy and an evaluation perspective, integrated approaches are needed. Co-financing and the delivery of integrated interventions was a common theme in expert consultations:

‘HIV money is limited, so as soon as you peg something as an HIV intervention, you slot it into the HIV funding slot and then other health budgets don't want to pay, education doesn't want to pay, social protection doesn't want to pay for it. The reality is international funds are shrinking and there are budget crises in many sectors that need to be better funded. Co-financing says that there is a trap that if programmes are implemented in silos… we have many valuable, cost effective and impactful interventions that cannot demonstrated single-sector value to warrant complex cost. In a silo-based world, we are underfunded. Co-financing is a framework for making decisions based on comprehensive approaches, integrated evaluations, developing mechanisms for budgeting that responds to them.’

(Expert Consultation, Academic and international not-for-profit organization worker)

‘We need to intersect livelihoods and health and education and parental care… what is important is how you get different interventions to work together… it is important to have complementarity among interventions. The focus must be on synergy and interventions working together.’

(Expert Consultation, Academic and international not-for-profit organization worker)

‘If we are going to reach all of those that have not been tested, if we are to get to 90% of treatment, if we want to end AIDS by 2030, we all have to collaborate. Not one sector by itself is going to achieve this. We all have to pull together.’

(Expert Consultation, International not-for-profit organization worker in Mudekunye, 2015)

Despite the promising potential and sustainability of social protection, barriers exist to ensuring that social protection initiatives are enshrined in policy. These include the social and political attitudes within governments, based on perceptions of who is deserving of support, with young people often being deemed undeserving (Seekings, 2007). Political ownership and domestic funding are fundamental to the sustained success of national social protection initiatives (Adato & Bassett, 2009). The key message here is the importance of long-term government-led social protection initiatives and on the feasibility of such programmes.

‘The success of [social protection] programmes is incumbent on whether governments are willing to take responsibilities of ownership… owned or co-financed (interventions) by governments are more sustainable.’

(Expert Consultation, International not-for-profit organization worker)

Even when there are strong policies in place, there can be wide discrepancies between social protection and health policy provisions and their successful implementation. Supply-side barriers to ensuring adequate implementation and coverage of social protection policies include inadequate awareness among implementers, inadequate skills, government coordination, human and health resources, insufficient motivation of social and health service providers and inconsistent service provision among street-level bureaucrats as to who receives social protection services. An additional barrier is the unsubstantiated yet widespread impression that social protection provisions fuel/ incentivize sexual irresponsibility, risk-taking and recklessness:

‘[I]n these days teenagers at the age of 16 and 18 are getting pregnant just to get the grant… All they care about is having fun and nothing else… Some of them get pregnant on purpose of getting the grant money from government… But now they use the money that was meant to feed their babies to have fun… go to braai places and buy alcohol… They say, “success is all about making profit”, so by having babies they are making a profit’.

(Anonymous interviewee in Hodes, Toska, & Gittings, 2016).

Such claims are not borne out of accounts of girls and adolescent women receiving cash transfers in South Africa (Rosenberg et al., 2015), but are present in the accounts of a range of adult authorities, including caregivers, healthcare workers and social service providers, as well as boys.

There are a variety of factors that will affect the successful uptake, reach and coverage of social protection mechanisms. These may include inadequate awareness on the part of potential beneficiaries and inadequate support for beneficiaries to sustainably access available social protection provisions. For example, the impact of social transfers that aim to improve health outcomes depend not only on the availability of the transfers but also the accessibility, cost and quality of health services as well as social norms that establish attitudes about healthcare (UNICEF, 2012).

A comprehensive analysis of potential risks and benefits of social protection mechanisms is necessary before designing and implementing successful social protection programmes. The importance of context cannot be overstated. The settings where social protection is provided and received mediate behaviours, experiences and outcomes (Seekings, 2007). Social protection forms must respond to local needs and be adapted in accordance with the specificities of context (Adato & Bassett, 2009) and account for different dimensions of agency and subjectivity. The categories, forms and combinations of social protection that best support children and adolescents at high-risk of HIV-infection will vary contextually. Such programmes must resonate with local understandings of health and illness and intersect with political norms, social practices and symbolic beliefs in ways that enhance, rather than obstruct, their efficacy, and their social and epidemiological benefits (de Haan, 2014). Researchers and implementers must grapple with the situation-dependent and context-specific natures of behaviour and identity and how these are negotiated, produced, and constructed in a dynamic interaction between individual and locality (Campbell, Kalipeni, Craddock, Oppong, & Ghosh, 1997; Devereux, 2015).

‘It is important to consider regions (Eastern and Southern Africa) and countries separately… In every country there are different components of social protection provision and different stages of development. In-country contexts are also important… For example, in Kenya, despite cash transfers and policies being in place, in some areas infections haven't stabilized… it is also important to include, urban and rural considerations.’

(Expert Consultation, International not-for-profit organization worker)

‘Topography of access (to social protection services) is wildly different. Needs are also different as are the expenses you may incur, even within a country, can be totally different between places… situations are fluid and dynamic geographically as well as in the life course of an adolescent. There are also risks when social protection is withdrawn… there isn't national coherence or consistency – funding schemes come and go and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are constantly changing and folding.’

(Expert consultation, Academic)

Ongoing need for evidence and future directions

While there is consensus amongst beneficiaries, practitioners and decision-makers that social protection can play a key role to attenuate the structural deprivations that lead to HIV infection and AIDS-related morbidities (Cluver, Orkin, et al., 2016; E. Miller & Samson, 2012; A. Pettifor et al., 2015), it is unclear which social protection initiatives are best for which key child and adolescent populations and priority groups, including lesbian, gay, bisexual, intersex and transgender children and adolescents, and children and adolescents with disabilities. Furthermore, research that directly assesses the effect of social protection on HIV and HSV-2 incidence is needed, although using biomarkers in adolescent samples requires very large study sample sizes, which massively increases cost of research. Nonetheless, the potential pathways through which social protection provisions reduce HIV infections are increasingly being mapped out through qualitative and quantitative studies. The next generation of research and programming must answer the questions of what works best, for whom, under which circumstances and most cost effectively.

‘Research is needed to identify the most cost-effective combinations that generate impact… we often live in a world where evaluation technologies drive policy solutions, rather than the most important policy interventions driving demand for evidence building approaches.’

(Expert Consultation, Academic and international not-for-profit organization worker)

Prevention for Positives

HIV-focused programmes, including awareness initiatives, are often univocal. Their principal message is to ‘Prevent HIV’, but this does not encompass the realities of those who are already HIV-positive, including over 5 million children and adolescents under 19 years old. While we need to stop HIV-negative people from getting infected, we can make great progress by supporting HIV-positive people to stop onwards transmission. Findings in this paper support the delivery of social protection interventions to help young people (children, adolescents and youth) live healthier lives and access preventive care (E. Miller & Samson, 2012; UNICEF-ESARO, 2015), particularly with regards to sexual well-being and HIV prevention (Cluver et al., 2014; Cluver, Orkin, et al., 2016). However, there is limited evidence about the effect of social cash transfers on ART adherence among children and adolescents (Cluver, Toska, et al., 2016) and on interventions that reduce HIV risk taking. Furthermore, there is a dearth of research on what social protection combinations may be best suited to address the compounded vulnerabilities of HIV-positive children and adolescents. Preliminary findings from a community-traced study in South Africa, indicate that access to in-kind cash benefits and care such as parenting supervision and supported disclosure may have positive effects on adherence to ART (Cluver, Hodes, Toska, et al., 2015; Cluver, Toska, et al., 2016) and safe sex (Toska, Cluver, Hodes, & Kidia, 2015). In light of potential linkages between poor adherence and sexual risk-taking among HIV-positive adolescents (Marhefka, Elkington, Dolezal, & Mellins, 2010), it is crucial to identify policy and programmatic interventions that can address the vulnerabilities of HIV-positive children as they become adolescents. In doing so they may improve health behaviours among HIV-positive adolescents, shoring up their resilience and thus also helping to prevent onwards transmission of HIV.

Combinations of interventions

One of the most important contributions that social protection provisions may make is through novel interventions that straddle biomedical and social spheres (Cluver, Hodes, Sherr, et al., 2015). One next step in HIV prevention research and programming is actively combining social protection and biomedical programmes (Coates, Richter, & Caceres, 2008). The DREAMS initiative is one such example which includes ‘combination prevention’ of social protection (e.g. cash transfers and parenting programmes) and biomedical and behavioural interventions (i.e. HIV testing, condom provision and PrEP) (PEPFAR, 2015 in Cluver 2015)(PEPFAR, 2014). Questions regarding the scalability and durability of these interventions remain unanswered (Delany-Moretlwe et al., 2015), presenting a powerful potential for further research in this field.

Gender

Growing evidence indicates that HIV-infection risk is linked to economic-disparate (where one partner has significantly greater financial means than the other) and intergenerational sex, as well as to unequal gender norms that limit women's power to negotiate safer sex or to protect themselves from violence (Harrison, Colvin, Kuo, Swartz, & Lurie, 2015; Shisana et al., 2014; Toska, Cluver, Boyes, Pantelic, & Kuo, 2015). As a result of these intersecting structural factors, adolescent girls account for over 62% of new infections in Eastern and Southern Africa (UNICEF-ESARO, 2015). Mixed-methods investigations provide increased recognition of the associations between gender inequality, transactionality, poverty and HIV-risk behaviours. Girls and young women tolerate condom refusal and sexual concurrency to maintain relationships with male sexual partners who supported them materially (Toska, Cluver, Hodes, et al., 2015). However, critics note that dominant discourses around gender inequalities and the ability of women and girls to protect themselves can be reductionist, and there is a need for more nuanced understandings of the relationships between HIV prevention and gender inequalities, including how they articulate with poverty and other factors (Govender, 2011; Jewkes & Morrell, 2012; Shefer, Kruger, & Schepers, 2015).

In light of the increased vulnerability of adolescent girls and young women to HIV infection, the gendering of regional social protection policies and interventions in commendable. However, a more nuanced analysis of the relationships between inequality, poverty and gender in HIV risk is required (Jewkes, Levin, & Penn-Kekana, 2003). Further research on social protection amongst adolescents, gender and HIV risk could also interrogate masculinities, given that norms of masculinity (Colvin, Robins, & Leavens, 2010; Jewkes et al., 2007; Sonke Gender Justice & MenEngage Africa, 2015) and institutional supply-side barriers (Dovel, Yeatman, Watkins, & Poulin, 2015) make men less likely to access prevention, testing, treatment and support services and more likely to be lost to follow-up or die on ART (Johnson et al., 2013).

There is a growing body of literature that indicates that efforts with men and boys for gender transformation have the potential to impact gender norms and practices that are harmful to men, women, girls and boys (Dworkin, Fleming, & Colvin, 2015; Dworkin, Hatcher, Colvin, & Peacock, 2013; Gittings, 2016). Research about masculinities as well as femininities, adolescence and HIV risk is an under-explored area that has the potential to provide valuable insights. Further research is needed to elucidate the complex gendered vulnerabilities and pathways for contracting and transmitting HIV and the uptake of HIV prevention and treatment services.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that flexible and responsive social protection mechanisms may be an important component in the response to the complex causal pathways resulting in HIV infection. Evidence on social protection programmes and policies highlights the potential for combinations of social protection interventions, particularly ‘cash’ combined with ‘care’ and ‘capability’ to interrupt risk pathways and build resilience. Social protection can play a role in HIV prevention among adolescents through alleviating economic and structural drivers of HIV risk, including economic and gender inequalities and social exclusion, which are at the root of HIV susceptibility and vulnerability, and underlie HIV-risk behaviours. As critical evaluations have shown, if social protection is to be effective for children and adolescents, it must be both HIV-inclusive and responsive to their unique needs (Delany-Moretlwe et al., 2015; A. Pettifor et al., 2015).

Recent global strategies – such as UNAIDS' Fast Track targets – and policy directives – such as the Sustainable Development Goals – provide an exciting opportunity for considering comprehensive forms of social protection and strengthening health and community systems for scaling up national responses. Given the urgency to implement effective programmes, a better understanding of which combinations of social protection packages have the most impact for HIV prevention and poverty mitigation among children in different HIV/AIDS contexts. As a large cohort of HIV-affected children in Sub-Saharan Africa reaches adolescence, social protection that improves the resilience to affect good health outcomes of young people is needed, particularly combination social protection, which include ‘capabilities’ components in addition to ‘cash’ and ‘care’ provisions. Ensuring the reach and uptake of such social protection programmes for the most vulnerable will be integral to ensuring that no child or adolescent is left behind.

Equally important, is the need to ensure that social protection policies and programmes are driven by local processes and embedded in national agendas. This requires supporting governments to take full responsibility for pilot projects, and to scale them up to sustainable national programs, when evidence on programmatic and cost-effectiveness is available. International donors and development partners need to support regional agendas on implementation of evidence-based programmes and build local capacity to improve access and delivery to social protection provisions.

Acknowledgments

Research presented here was conducted within the Mzantsi Wakho study, a collaboration of the Universities of Cape Town and Oxford. We thank participants, particularly adolescents, families, healthcare workers and social service providers. Chris Colvin, Rajen Govender, Caroline Kuo, Nicoli Nattrass, Izidora Skracic, Julia Rosenfeld, and the UNICEF-ESARO/Transfer Project provided intellectual guidance and support for this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Regional Inter-Agency Task Team on Children and AIDS in Eastern and Southern Africa (RIATT-ESA), Nuffield Foundation under Grant CPF/41513, the International AIDS Society through the CIPHER grant (155-Hod), DFID's Evidence for HIV Prevention in Southern Africa (EHPSA) programme, Janssen's Educational Grant programme, the Clarendon-Green Templeton College Scholarship, and the Philip Leverhulme Trust (PLP-2014-095). Additional support for Lucie Cluver was provided by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ ERC grant agreement n°313421. Additional support for Rebecca Hodes was provided by South Africa's National Research Foundation and the University of Cape Town's Humanities Faculty.

Footnotes

Sustainable Development Goal #1 is to “End poverty in all its forms everywhere” and target 1.3 calls for the implementation of “nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable” as a means to achieve this.

Regionally, the Southern African Development Community's ‘Minimum package of services for orphans and other vulnerable children and youth’ recognizes the vulnerabilities of children and youth in the region. It has defined the basic needs and minimum services for vulnerable children and youth and entrenched policy recommendations for provision of these services in a comprehensive and holistic manner (SADC, 2011). In Eastern Africa, there has been a recent push towards the harmonization of laws and policies in order to create common health environments. A feasibility study has been conducted about harmonizing social health protection systems across the region and providing universal healthcare (East African Community (EAC), 2014), and implementation conversations are currently underway. It is within these rich policy environments that we consider the potential for, and future of, social protection for HIV prevention among children and adolescents.

The term ‘plus’ is used throughout the paper to refer to combinations of social protection categories, for example a cash-plus-care provision is a programme combining cash/ cash-in-kind and care components, as used by Cluver and colleagues (Cluver et al., 2014), to refer to combinations of child support grants (cash) and positive parenting (care).

The term ‘unconditional’ is used to mean that receipt of the transfer is not linked to the recipient doing certain tasks (such as taking children for health checks, school enrolment or participating in community works programmes).

African Journal of AIDS Research Special Issue: Fast Tracking the HIV Prevention Response in the New Health and Development Agenda

References

- Adato M, Bassett L. Social protection to support vulnerable children and families: The potential of cash transfers to protect education, health and nutritionAIDS Care. 2009;21(sup1):60–75. doi: 10.1080/09540120903112351. http://doi.org/10.1080/09540120903112351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amzel A, Toska E, Lovich R, Widyono M, Patel T, Foti C, Altschuler J. Promoting a combination approach to paediatric HIV psychosocial supportAIDS (London, England) 2013;27(Suppl 2):S147–57. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000098. http://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird SJ, Garfein RS, McIntosh CT, Ozler B. Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9823):1320–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61709-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera O, Buehren N, Burgess R, Goldstein M, Gulesci S. Empowering Adolescent Girls: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial in Uganda. London, United Kingdom: 2013. Retrieved from https://reach3.cern.ch/imagery/SSD/32BHP_Brace/Handover Lis/Resources/Methodology/ELA_RCT Uganda_HIV.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Charrow A, Hansen N. Annual Research Review: Mental health and resilience in HIV/AIDS-affected children - a review of the literature and recommendations for future research. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2013;54(4):423–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02613.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhana A, Mellins CA, Petersen I, Alicea S, Myeza N, Holst H, McKay M. The VUKA family program: piloting a family-based psychosocial intervention to promote health and mental health among HIV infected early adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2014;26(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.806770. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=23767772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden J. Childhood and the policy-makers: a comparative perspective on the globalisation of childhood. In: James A, Prout A, editors. Constructing and Reconstructing Childhood: Contemporary Issues in the Sociological Study of Childhood. 2. London, United Kingdom: Falmer Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Busza J, Besana GVR, Mapunda P, Oliveras E. Meeting the needs of adolescents living with HIV through home based care: Lessons learned from Tanzania. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014 Feb;45:137–142. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.03.030. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Kalipeni E, Craddock S, Oppong J, Ghosh J. Migrancy, masculine identities, and AIDS: The psychosocial context of HIV transmission on the South African gold mines. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(2):273–281. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00343-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, Skovdal M, Mupambireyi Z, Madanhire C, Nyamukapa C, Gregson S. Building adherence-competent communities: factors promoting children's adherence to anti-retroviral HIV/AIDS treatment in rural Zimbabwe. Health & Place. 2012;18(2):123–31. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.07.008. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandan U, Richter LM. Programmes to strengthen families: Reviewing the evidence from high income countries 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, Hallfors DD, Mbai II, Itindi J, Milimo BW, Halpern CT, Iritani BJ. Keeping adolescent orphans in school to prevent human immunodeficiency virus infection: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Kenya. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48(5):523–526. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]