Abstract

Isolated abdominal aortic dissections are rare events. Their anatomic and clinical features are different from those of atherosclerotic aneurysms. We report 4 cases of isolated abdominal aortic dissection that were successfully treated with surgical or endovascular intervention. The anatomic and clinical features and a review of the literature are also presented.

Key words: Aneurysm, dissecting/diagnosis/surgery/therapy; aorta, abdominal/pathology; aortic dissection, abdominal/diagnosis/surgery/therapy; blood vessel prosthesis; chronic disease; endovascular stent-graft; human; male; tomography, X-ray computed

Aortic dissection is rarely limited to the abdominal aorta. The reported rate of primary abdominal aortic dissection is less than 2%, compared with that of ascending aortic dissection (70%), descending aortic dissection (20%), and aortic arch dissection (7%).1 The anatomic and clinical features of isolated abdominal aortic dissections are different from those of common atherosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). We report our recent experience with 4 patients who presented at our institution between February 2000 and June 2003.

Case Reports

Patient 1

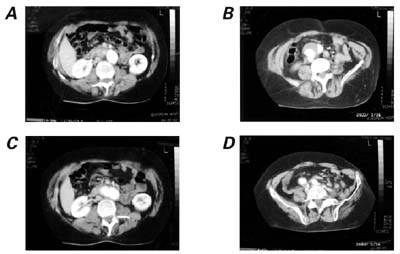

In June 2002, a 42-year-old man with a family history of Marfan syndrome and aortic dissection was admitted for aortic root replacement as a consequence of chronic dissecting aneurysm of the ascending aorta. Physical examination revealed a palpable, pulsatile abdominal mass. Computed tomographic (CT) scanning (Fig. 1) revealed an ascending aortic dissecting aneurysm and an isolated dissecting AAA (widest diameter, 5 cm), extending from the infrarenal aorta to the right internal iliac artery, without evidence of thoracic or suprarenal aortic dissection.

Fig. 1 Patient 1. Computed tomographic scan shows A) a nondissected suprarenal aorta associated with B, C) an infrarenal abdominal aortic dissection, extending to D) the right iliac artery.

A 2-staged operation was performed. The 1st stage consisted of valve-sparing aortic root reconstruction with a Gelweave Valsalva™ 30-mm vascular prosthesis (Sulzer Vascutek®; Renfrewshire, Scotland), followed 2 weeks later by abdominal aortic reconstruction with a standard Hemashield Gold 18 × 9-mm bifurcated Dacron graft (Boston Scientific/Medi-tech; Natick, Mass). The abdominal aortic graft was proximally anastomosed end-to-end to the nondissected portion of the aorta; and the distal graft branches were anastomosed end-to-end to the nondissected left common iliac artery and the right internal iliac artery. The right external iliac artery was reimplanted end-to-side to the right branch of the prosthesis. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 7 days later. When last seen in December 2004, the patient was alive, without complications.

Patient 2

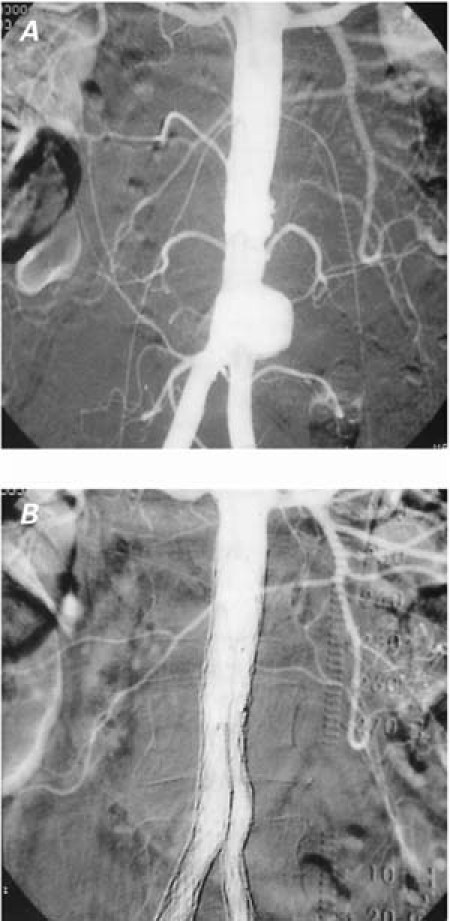

In February 2000, a 71-year-old man who had a history of chronic hypertension was evaluated because of blue toe syndrome. A CT scan revealed an isolated dissection of the infrarenal aorta with a small pre-bifurcation aortic aneurysm (widest diameter, 3 cm). The aneurysm was treated with an endovascular procedure (Fig. 2) consisting of placement of a 22 × 13 × 135-mm bifurcated AneuRx® AAA Stent Graft (Medtronic, Inc.; Minneapolis, Minn). The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 3 days later. When last seen in June 2004, the patient was alive, without complications.

Fig. 2 Patient 2. Angiographic examination performed A) before and B) after endovascular stenting.

Patient 3

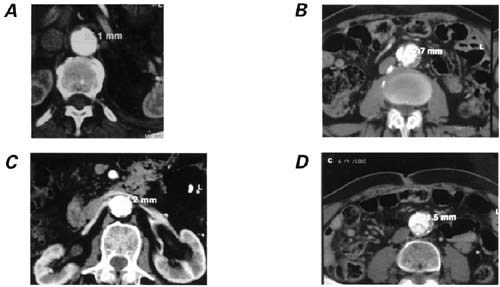

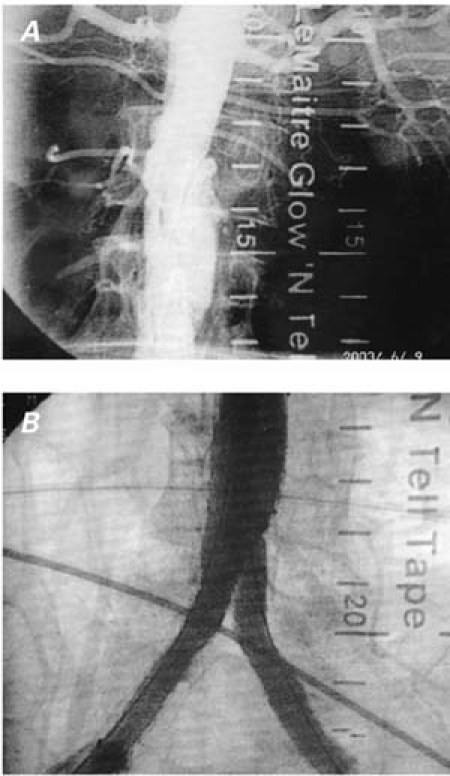

In June 2003, an 81-year-old man who had a history of chronic hypertension was evaluated because of peripheral arterial embolization with lower limb ischemia. A CT scan (Fig. 3) revealed an isolated dissection of the infrarenal aorta with a small infrarenal aneurysm (widest diameter, 2.7 cm). The aneurysm was treated with an endovascular procedure (Fig. 4) consisting of implantation of a 23 × 12 × 140-mm Excluder® stent graft (W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc.; Flagstaff, Ariz). The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 2 days later. In December 2003, the patient was alive, without complications.

Fig. 3 Patient 3. Computed tomographic scan shows A, B) a nondissected suprarenal aorta associated with C, D) an infrarenal abdominal aortic dissection.

Fig. 4 Patient 3. Angiographic examination performed A) before and B) after endovascular stenting.

Patient 4

In July 2002, a 61-year-old man who had a history of chronic hypertension presented with acute abdominal pain, without clinical evidence of hemorrhagic shock. He had experienced an acute myocardial infarction followed by coronary revascularization 8 years earlier. A CT scan revealed a large dissecting AAA (widest diameter, 8 cm), which originated just below the renal arteries and extended distally to the right common iliac artery (confirmed by aortic angiography). The ascending aorta was slightly dilated (widest diameter, 4 cm), but there was no evidence of suprarenal or thoracic aortic dissection.

Surgical treatment consisted of direct abdominal aortic reconstruction through a midline incision. Cross-clamps were placed on the juxtarenal aorta and on the right and left iliac bifurcation, where the dissection ended. After excision of the entire dissecting flap, an 18 × 9-mm bifurcated Hemashield Gold Dacron graft was anastomosed end-to-end to the nondissected infrarenal proximal aorta, and distally to the bilateral iliac bifurcation. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 6 days later.

Discussion

Spontaneous dissection of the abdominal aorta (not associated with trauma or with descending thoracic aortic dissection) is rare; it accounts for less than 2% of all aortic dissections.1 However, the wide use of CT scanning in cases of nonspecific abdominal pain has begun to reveal this condition with increasing frequency. Farber and coworkers2 recently reported the cases of 10 patients in whom isolated dissecting AAAs were observed within a 6-year period. Our 4 patients presented within a shorter period of time (about 3 years) and constituted 4.1% of patients (4/97) who underwent elective AAA resection at our hospital during that time period.

In cases of AAA dissection, the dissection flap generally originates below or at the level of the renal arteries; less often, the intimal tear is in the suprarenal aorta.3,4 In the series of Farber and coworkers,2 the dissection flap originated below the renal arteries in 9 cases and at the level of the superior mesenteric artery in 1 case. Similar findings had previously been reported by Becquemin and co-authors5 in a series of 7 patients affected by acute or chronic dissection of the abdominal aorta. In that study, 6 of 7 patients had infrarenal dissection.

As opposed to the more common atherosclerotic aneurysms, isolated dissecting AAAs are often evident clinically, although the symptoms are nonspecific. The fast expansion of the false lumen of the aneurysm produces early clinical symptoms, such as back pain, peripheral ischemia, distal embolization, and an easily detectable pulsatile abdominal mass. In a review of 47 cases of abdominal aortic dissection, approximately 33% presented with lower limb ischemia, 30% with abdominal pain, and 20% with back or flank pain.6 More recent clinical series, in addition to the present report, confirm that dissecting AAAs, although associated with heterogeneous clinical features, are rarely asymptomatic.2,5,7

Therapeutic options in cases of dissecting AAAs include prosthetic replacement of the involved aorta or observation only, in selected cases (asymptomatic chronic dissections), with regular follow-up. Of note, these therapeutic options are similar to those commonly used for atherosclerotic aneurysms. When feasible, endovascular techniques provide an alternative and less invasive therapy than does surgery. In such cases, intravascular ultrasound-guided stent-grafting is recommended.8

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Paolo Nardi, MD, Division of Cardiac Surgery, University of Rome Tor Vergata European Hospital, Via Portuense 700, 00149 Rome, Italy. E-mail: pa.nardi@quipo.it

References

- 1.Roberts CS, Roberts WC. Aortic dissection with the entrance tear in abdominal aorta. Am Heart J 1991;121:1834–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Farber A, Wagner WH, Cossman DV, Cohen JL, Walsh DB, Fillinger MF, et al. Isolated dissection of the abdominal aorta: clinical presentation and therapeutic options. J Vasc Surg 2002;36:205–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Baumgartner F, Omari B, Donayre C. Suprarenal abdominal aortic dissection with retrograde formation of a massive descending thoracic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 1998;27:180–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Elliott BM, Roberts CS, Robison JG, Brothers TE. Aortic dissection originating in the suprarenal abdominal aorta. J Vasc Surg 1994;19:1092–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Becquemin JP, Deleuze P, Watelet J, Testard J, Melliere D. Acute and chronic dissections of the abdominal aorta: clinical features and treatment. J Vasc Surg 1990;11:397–402. [PubMed]

- 6.Graham D, Alexander JJ, Franceschi D, Rashad F. The management of localized abdominal aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg 1988;8:582–91. [PubMed]

- 7.Cambria RP, Morse S, August D, Gusberg R. Acute dissection originating in the abdominal aorta. J Vasc Surg 1987;5: 495–7. [PubMed]

- 8.Giudice R, Frezzotti A, Scoccianti M. Intravascular ultrasound-guided stenting for chronic abdominal aortic dissection. J Endovasc Ther 2002;9:926–31. [DOI] [PubMed]