Abstract

Background

The treatment for prostate cancer patients with biochemical failure after local therapy remains controversial. Peripheral androgen blockade using a combination of a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor and an antiandrogen may allow control of the PSA. Since testosterone levels are not suppressed, this approach may be associated with less morbidity than conventional gonadal androgen suppression.

Patients and Methods

All patients had undergone previous definitive local therapy and had evidence of a rising PSA above 1 ng/ml, with no evidence of recurrent disease. Patients received both finasteride, 5 mg po per day, and flutamide, 250 mg po TID. Patients were followed for a PSA response and quality of life assessment.

Results

99 of 101 accrued patients are eligible. A ≥80% PSA decline was seen in 96(96%) patients. The median time to PSA progression was 85 months. With a median follow up of 10 years, the median survival time has not been reached and the five-year overall survival rate is 87 %. Toxicity was mild, with 18 patients stopping for toxicity; 15 had diarrhea, four had gynecomastia, and 3 patients had transaminase elevation. Baseline FACT-P and TOI scores decreased by 5 points each at 6 months post-enrollment.

Conclusions

The use of the finasteride/flutamide combination is feasible, and results in PSA declines of ≥ 80% in 96% of patients with serologic progression after definitive local therapy. There were no unexpected toxicities and the change in quality of life was mild. Further evaluation of this or a similar regimen in a controlled clinical trial is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 1 in 3 men treated for clinically localized prostate cancer will develop recurrent disease, most commonly demonstrating a rising PSA, termed serologic progression[1, 2] The treatment of such early recurrences remains controversial. A number of salvage local therapies, such as radical prostatectomy for radiation therapy failures[3], salvage radiotherapy for surgery failures[4],or the use of other local therapeutic approaches such as cryotherapy[5] have been used in selected patient populations. Another common approach is the use of systemic therapy. The most active systemic therapy, with a response rate of over 90%[6], is testosterone lowering treatments, termed androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). However, such therapy may have a myriad of side effects, such as hot flashes, loss of muscle and bone mass, depression, mood swings, loss of mental acuity and decreased libido[7]. More recently, the potential adverse effect on glucose homeostasis and cardiac events have been raised as concerns.[8, 9] Furthermore, the survival benefit of such therapy remains unproven.[6] Since patients with PSA only recurrences after definitive local therapy are not necessarily destined to die of their disease, they are excellent candidates for therapy which may have lower toxicity, while retaining the potential to control their disease.

Alternatives to gonadal androgen ablation have been investigated. Some therapies, such as 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, may affect prostate cancer cells by blocking the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone, thereby lowering dihydrotestosterone levels in the cells[10]. Currently available 5-alpha reductase inhibitors include finasteride which inhibits only one isoenzyme, or dutasteride which inhibits both of the two isoenzymes that humans possess to convert testosterone to dihydrotestosterone. Finasteride monotherapy has been shown to have some activity in the prevention of prostate cancer[11] [12], but appears to be inactive in treating metastatic disease.[13] Its role in prostate cancer patients with serologic progression is unproven.

Antiandrogens are a class of drugs that bind the androgen receptor, thereby inhibiting its activation by androgens. Drugs of this class include flutamide, bicalutimide, and nilutamide. Bicalutamide has been studied in the adjuvant setting after local therapy, where its use delayed time to PSA recurrence, but had no impact on overall survival[14]. As monotherapy in the metastatic setting, these agents are inferior to ADT.[15] However, several pilot trials have shown that the addition of anti-androgens to 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (termed “peripheral androgen blockade” because systemic testosterone levels are not lowered) may have useful activity in the control of prostate cancer.[16–18] Furthermore, these pilot trials suggested that peripheral androgen blockade is well tolerated and potentially less morbid than ADT. Based on these data, beginning in 1998, the CALGB undertook a phase 2 study of the finasteride/flutamide combination as peripheral androgen blockade in patients with serologic progression after definitive local therapy, with the intent of evaluating an approach for this group of patients that was potentially better tolerated than ADT. At the time this study was designed, the only 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor available was finasteride, and the finasteride/bicalutamide combination had not yet been tested. While launched in 1998, this study has not been previously reported because of the long term survival of these patients.

METHODS

Patients

The study population consisted of patients with localized prostate cancer treated with either a radical prostatectomy, or external beam radiation therapy. This treatment had to be completed at least 1year, but no more than 10 years prior to enrollment. No more than 6 months of any hormonal therapy could have been received as adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy. Patients had to have a PSA level of ≥1 ng/ml, but ≤10 ng/ml, with evidence of a rise of at least 1 ng/ml above their nadir, confirmed by at least one additional PSA level at least one week later. At the time this study was launched, there was little appreciation of the prognostic value of PSA doubling time, so this pre-treatment variable was not assessed. No patient could have had hormonal therapy within 12 months of registration, and in particular no 5α-reductase inhibitor therapy within two years of protocol treatment was permitted. Patients could not be on corticosteroids above standard replacement doses, could not have undergone an orchiectomy, and no previous cytotoxic chemotherapy for prostate cancer was allowed. Patients were required to have a CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis and a bone scan showing no evidence of metastatic disease and no evidence of recurrent or persistent local disease on digital rectal exam. An ECOG performance status of ≤2 was required. Finally, serum levels of AST and/or ALT, creatinine and bilirubin ≤2 times the upper limits of normal were also required at trial entry.

Study Design

The study was approved by the Executive Committee of the CALGB, and by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating site. All patients provided written, informed consent. Therapy consisted of a combination of finasteride at 5 mg po daily and flutamide 250 mg po TID. Blood tests to monitor liver function tests, PSA, testosterone, LH and FSH were obtained once a month for the first three months, then every three months for three visits, and every six months thereafter. Toxicity was assessed at these timepoints and graded according to CTC version 2. Progression was defined as the development of metastatic disease on scan, recurrence of local disease on scan or physical exam, or PSA progression. Dose adjustments required by the study included removal of patients from study treatment for grade 2 or higher elevation of AST or ALT. Grade 2 or greater diarrhea resulted in a decrease of flutamide to half-dose (125 mg po TID), with discontinuation of the flutamide if there was a recurrence of grade 2 or greater diarrhea on reduced doses. To prevent gynecomastia, prophylactic breast irradiation was encouraged, but not mandated.

After progressive disease was noted, flutamide was discontinued, and patients remained on finasteride, to monitor for a potential anti-androgen withdrawal response. After further progression on finasteride monotherapy, treatment with combined androgen blockade, consisting of an LHRH agonist and either bicalutamide or nilutamide, was undertaken.

Quality of Life

Quality of life (QOL) was measured primarily by using the FACT-P instrument.[19] This was supplemented with additional questions focusing specifically on sexual functioning adapted from Medical Outcomes Study Sexual Problems Scale.[20] Patients completed the questionnaire at baseline, 3 months and 6 months.

Endpoints

This trial was designed prior to the development of consensus criteria by the PSA Working Group. In this trial, a response was defined as a PSA decline of ≥80%. Since patients had no evidence of metastatic disease on study entry, routine follow-up scans were not required, but documentation of metastatic disease on scans obtained for cause was considered meeting criteria for progression. Progression by PSA criteria was defined in the protocol as a rise of ≥4 ng/ml or 50% above the nadir, whichever was greater. The nadir was considered the lowest PSA level while on protocol therapy. An elevated confirmatory PSA at least one week later was also required for progression.

Statistical Design and Data Analysis

The primary endpoint of this study was time to PSA progression. Sample size computation was based on the primary endpoint. The null hypothesis was that the median time to PSA progression was less than or equal to 18 months, with the alternative hypothesis being that the median time to PSA failure would be 26 months or greater. The target sample size was 100 patients. The normal approximation to the exact exponential test was used for sample size computation and the following assumptions were made: a two-sided type I error rate =0.05, power of at least 80%, an accrual rate of 4 patients/month over a 24-month accrual period, an 18-month follow-up period, and the time to PSA progression follows an exponential distribution.

At the time the protocol for this study was written, very little was known about the natural history of patients experiencing biochemical failure after local therapy for prostate cancer. Indeed, the present study represents one of the first cooperative group studies in this disease state. A median time to progression of 18 months was assumed based on the PFS results of SWOG 8894 a study of bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide in patients with untreated metastatic prostate cancer. [21] In retrospect these calculations should have been based on the subset with “minimal disease” which still represented a more advanced disease group than the men in our study.

The primary interest in the quality of life was the change in the total score of the FACT-P between baseline and month 6 during treatment with the combination of finasteride and flutamide. In particular, the study was designed to detect a “small” to “medium” change in the FACT-P at month 6 relative to baseline, specifically a standardized mean change of 0.34, at the 0.05 level of significance (two-tailed) with 80% power. This change was prospectively defined as reflecting a “small to medium” change.

The Kaplan-Meier product-limit approach was used to estimate the time to PSA progression, prostate cancer specific survival (PCSS), time to metastases and overall survival time distributions. PCSS was defined as the time interval between study entry to the time of death due to prostate cancer. OS was defined as the time interval between study entry to date of death due to any cause. Time to metastases was defined as the interval between study entry to date of initial metastases. Metastatic disease was defined as recurrence on exam, scan, or biopsy. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the toxicity data.

The change of QOL measures over time against baseline was evaluated using a generalized linear model with the generalized estimating equation (GEE) method. The empirical variance estimates from the GEE analysis takes the correlation of multiple measures of QOL scales over time into account and forms the basis of testing the change of QOL measures after receiving treatment. In the GEE analyses, only patients who provided all three QOL assessments are included. Assessment time is the only covariate included in modeling, and an unspecified correlation structure is chosen. For continuous scores of the FACT-P, an identity link is used to fit linear regression models. For ordinal scores, such as the sexual problems scale, a multinomial cumulative logic is used to fit the proportional odds models.

Patient registration and data collection were managed by the CALGB Statistical Center. Data quality was ensured by careful review of data by CALGB Statistical Center staff and by the study chairperson. Statistical analyses were performed by CALGB statisticians. As part of the quality assurance program of the CALGB, members of the Audit Committee visit all participating institutions at least once every three years to review source documents. The auditors verify compliance with federal regulations and protocol requirements, including those pertaining to eligibility, treatment, adverse events, tumor response, and outcome in a sample of protocols at each institution. Such on-site review of medical records was performed for 49 of the 101(49%) patients enrolled in this study.

RESULTS

Patients

A total of 101 patients were enrolled onto this study from October, 1998 through July, 2001. One patient was found to be ineligible, and one patient never started protocol therapy. Long term outcome results are based on the 99 patients treated. Patient demographic and clinical data are summarized in Table 1. The enrollment data indicate a typical group of patients who developed an elevated PSA after local therapy for this time period. Sixty-six percent of the patients had undergone primary therapy consisting of radical prostatectomy, whereas 71% had received prior radiotherapy, mostly as secondary or salvage therapy. Median PSA at time of enrollment was 3.8 (range 1.0 to 9.9). These patients were largely asymptomatic, with only 10% taking an analgesic for any reason. Their performance status was high, with 76% being ECOG 0, and their laboratory parameters such as hemoglobin (median=14.7 g/dl), and alkaline phosphatase (median of 72.5 IU/l) reflected their low systemic tumor burden. Gleason score was assessed locally; 78% of patients had a Gleason score of ≤7. Per eligibility criteria, no patient had evidence of metastatic disease or grossly apparent locally recurrent or persistent disease.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Data on 99 Eligible Men

| Median Age, years (range) | 71 (48–85) |

| Race % | |

| White | 82 |

| AA | 16 |

| Other | 2 |

| Median Years Since Diagnosis (range) | 4 (0.85–13.31) |

| Gleason Score % | |

| <5 | 12 |

| 5–7 | 66 |

| 8–10 | 22 |

| ECOG Performance Status % | |

| 0 | 76 |

| 1 | 23 |

| 2 | 1 |

| Median Hemoglobin, g/dl (range) | 14.7 (5.0–17.5) |

| Median PSA, ng/ml (range) | 3.8 (1.1–9.9) |

| Median Alkaline Phosphatase, IU/I (range) | 72.5 (3.0–183.0) |

| Median Testosterone, ng/dl (range) | 321 (0–831) |

| % Prior Hormonal Treatment | 23 |

| % Prior Radiation | 71 |

| % Prior RP | 66 |

Clinical Outcomes

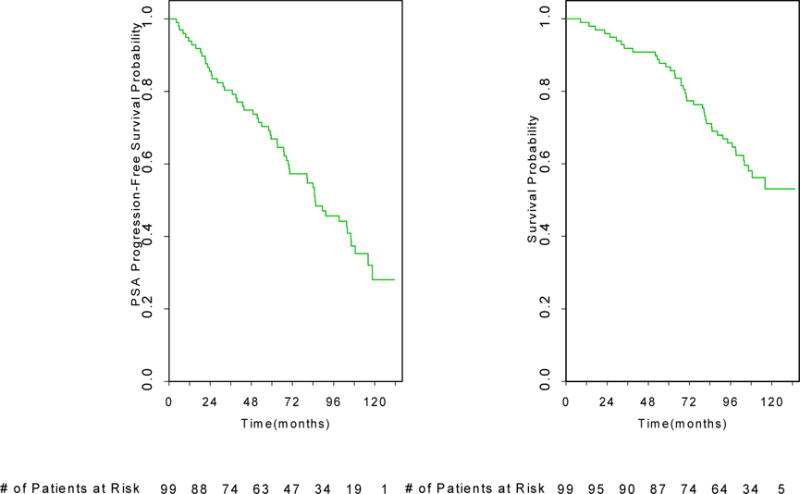

Nearly all patients met the predefined criteria for a PSA response, with a decline in PSA level of ≥80% observed in 96/99 patients. The remaining three patients had declines of 77%, 73% and 38%, which were not confirmed. Seventy three percent of enrolled patients achieved an undetectable PSA value (<0.2 ng/ml). Over 50% of the patients had their PSA decrease below 1 ng/ml by the first month, and the median time to a nadir value was 3.2 months. The median PSA progression-free survival is 85 months (95% CI=70–106) and the 5 year PSA progression free survival rate is 65% (Figure 1A). With 10-years of follow-up, the median survival time has not been reached and the 5 year overall survival rate is 87% (Figure 1B). The 5-year prostate cancer specific survival rate is 95.7% (95%CI = 89.0 – 98.4). The 5year metastases freedom rate is 97.5 % (95% CI = 90.2–99.4).

Figure 1.

(Top) Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression-free survival probability is shown. (Bottom) Overall survival probability is shown.

An exploratory analysis based on baseline Gleason Score was performed. The median time to PSA progression or death for patients with baseline Gleason sum 8–10 was 67 months (95% CI =32–86), compared to 104 months (95% CT=70–119,) for patients with Gleason sum <8.

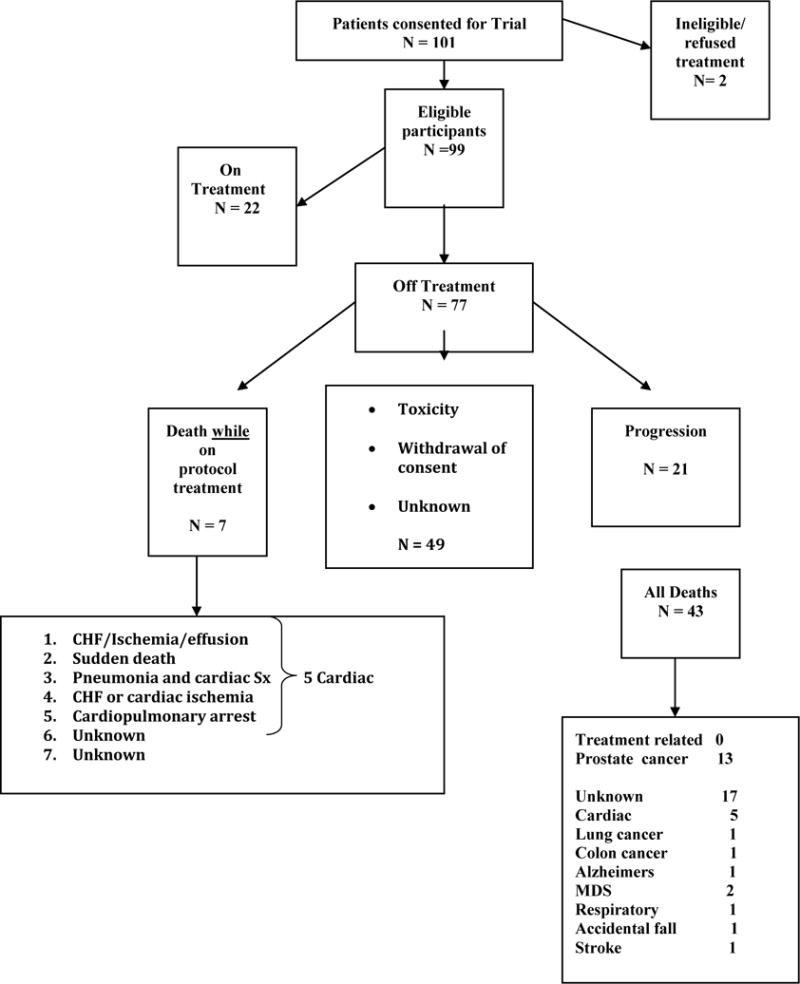

Patient Disposition

Patient disposition is summarized in Figure 2. Of 99 eligible patients 22 remain on therapy. Of the 77 patients off protocol treatment, 43 patients have died. Of these, 13 deaths were attributed to progressive prostate cancer. Other causes of death included 5 patients (12% of all deaths, and 5% of all patients) who experienced cardiac events or events that were potentially cardiac in nature while on protocol treatment. This included 2 patients with CHF and/or ischemia, 1 with cardiopulmonary arrest, 1 with cardiac symptoms in the setting of pneumonia, and 1 patient with sudden death. Two patients developed myelodysplasia. One patient each died from metastatic lung and colon cancers, respectively, which were diagnosed after starting therapy. Other causes of death included Alzheimer’s disease, respiratory distress, stroke and an accidental fall. Seventeen patients had unknown causes of death.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition is summarized. CHF, congestive heart failure; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; Sx, symptoms.

Reasons for removal from protocol therapy include toxicity (18 patients), progressive disease (21 patients) and withdrawal of consent (9 patients). The major toxicities that led to patient removal from treatment (vide infra) include toxicities that were expected, such as diarrhea, elevation of liver enzymes and gynecomastia.

Response to subsequent hormonal therapy

At the time of protocol-defined progression, patients underwent flutamide withdrawal, and upon further progression were placed on combined androgen blockade (CAB) with an LHRH agonist and a different anti-androgen other than flutamide. Outcome data from these maneuvers are incomplete, due to 22 patients remaining on their original treatment, and a number of other patients being taken off trial prior to progression. However of the 21 patients to date who have been taken off flutamide due to progression, two (14%) had a withdrawal response, as measured by a ≥50% decrease in serum PSA. Nineteen of 27 patients (70%) subsequently treated with combined androgen blockade sustained a PSA response of ≥50%. Six men received CAB without waiting for a flutamide withdrawal response. The duration of response to CAB was not captured, as this was considered post-protocol therapy.

Adverse Events (AEs)

Grade 3 or higher AEs, and selected AEs that occurred in >5% of patients are listed in Table 2. Sixty seven percent of men experienced gynecomastia or breast tenderness and over one half of men experienced grade 1 or 2 anemia. Twenty eight percent of the men had Grade 1 or 2 transaminase elevations and 33% of men had grade 1 or 2 diarrhea. Grade 4 toxicities (n=4) were observed in 1 patient each, and consisted of a severe rash with associated bleeding, mood change (depressive episode that led to discontinuation of therapy), thrombosis (DVT) and myocardial infarction.

Table 2.

Number of Grade 3 and 4 Toxicities, and Selected Toxicities Occurring in >5% of Patients.

| Event | Grade 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anemia | 51 | 2 | 0 |

| Lymphocytes | 25 | 11 | 0 |

| Platelets | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Malaise/Fatigue | 42 | 0 | 0 |

| Transaminase Elevation | 28 | 1 | 0 |

| Weight Loss | 12 | 1 | 0 |

| Weight Gain | 23 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 28 | 3 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 33 | 3 | 0 |

| Gynecomastia/Breast tenderness | 67 | 3 | 0 |

| Hot Flashes | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Impotence/Libido | 20 | 19 | 0 |

| Elevated BUN | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Creatinine | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Hematuria | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Proteinuria | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Edema | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Neurologic | 12 | 1 | 0 |

| Skin | 16 | 0 | 1 |

| Mood Change | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| Phlebitis/Thombosis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Cardiac ischemia | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Myocardial Infarction | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Dyspnea | 10 | 1 | 1 |

| Hypertension | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Dysrhythmia | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Hyperkalemia | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Prothrombin | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| PTT | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Eighteen patients were removed from treatment due to adverse events. Fifteen patients had diarrhea which led to their removal from study. Three men had grade 3 diarrhea. Four patients withdrew consent due to the development of grade 1 or 2 gynecomastia. One of these patients had received prophylactic radiation therapy. Three patients were taken off for grade 2 elevations of their transaminases. One other patient developed a rash which led to removal from the trial, and one other patient was removed for a deep vein thrombosis.

Quality of Life

Eighty-six (86) of 99 patients provided their background information, including education, marital status, and employment status. QOL assessments were available from 96, 85, and 87 patients at baseline, month 3, and month 6, respectively. Seventy-six patients (76) provided responses to all three QOL assessments. Sixty-seven (67) patients provided both background information and all three QOL assessments.

Overall, quality of life as measured by the FACT-P decreased over time; with scores at the 6 month assessment being generally worse (Table 3). Significant declines were seen in the total FACT-P (p=0.0045), total FACT-G (p=0.0044), physical well-being (p<0.0001), functional well-being (p=0.0036) and Treatment Outcome Index (TOI, p<0.0001). Cella et al [22]demonstrated that 5–7 point changes on the Total FACT scores and TOI scores are clinically meaningful. By this criterion, clinically meaningful changes were seen on the total FACT-P and the TOI scores. Examination of the sexual functioning items revealed significant improvements over time in the ability to relax and enjoy sexual activity (Table 3, p=0.0255) and to become sexually aroused (Table 3, p=0.0005).

Table 3.

Estimated means and Wald Chi-square p-values testing the difference scores of 3-/6-months and baseline for total FACT-P and its subscales, and sexual problem scales

| QOL measures | Difference of 3-ms vs. baseline Est. mean (std error) | Difference of 3-ms vs. baseline p-value | Difference of 6-ms vs. baseline Est. mean (std error) | Difference of 6-ms vs. baseline p-value | Differences of 3-/6-ms vs. baseline p-value *** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total FACT-P | −2.62 (1.60) | 0.1031 | −5.13 (1.81) | 0.0045 | 0.0132 |

| Total FACT-G | −1.18 (0.94) | 0.2082 | −2.82 (0.99) | 0.0044 | 0.0057 |

| Physical well-being | −1.72 (0.37) | < 0.0001 | −2.32 (0.40) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Social family well-being | 0.45 (0.57) | 0.4308 | −0.18 (0.55) | 0.7372 | 0.3741 |

| Emotional well-being | 1.11 (0.38) | 0.0037 | 0.49 (0.40) | 0.2164 | 0.0076 |

| Functional well-being | −1.18 (0.43) | 0.0059 | −1.25 (0.43) | 0.0036 | 0.0118 |

| TOI=physical, functional well-being prostate concerns | −3.98 (1.09) | 0.0002 | −5.14 (1.26) | <0.0001 | 0.0002 |

| Prostate concerns | −1.08 (0.58) | 0.0629 | −1.33 (0.75) | 0.0733 | 0.1344 |

| Being able to have and maintain an erection + | 0.85 (0.18) | 0.4564 | 1.19 (0.25) | 0.4122 | 0.2236 |

| Lack of sexual interest + | 0.68 (0.16) | 0.1043 | 0.62 (0.13) | 0.0255 | 0.0745 |

| Being able to relax and enjoy sex + | 0.56 (0.11) | 0.0038 | 1.07 (0.21) | 0.7311 | 0.0016 |

| Difficulty becoming aroused + | 0.52 (0.12) | 0.0033 | 0.41 (0.11) | 0.0005 | 0.0020 |

The coding of “Lack of sexual interest” and “Difficulty becoming aroused” are preserved from the original scale.

the estimated means and its standard errors are the odds ratio of having a higher score at 3/6 months relative to at baseline (the exponentiated differences of the log odds) and its std. error.

DISCUSSION

The appropriate therapy for patients with serologic progression after definitive local therapy remains unknown. Local salvage therapy clearly has a role in selected patients. Recently, the PSA doubling time (PSADT) has been used as a means to distinguish between patients who might benefit from additional local therapy versus those that might benefit from systemic therapy.[23, 24] ADT has been widely used in patients with serologic progression, but appears to be associated with toxicities with long-term use, and has not been shown to prolong survival. It was in this context that CALGB 9782 was launched, as a means of evaluating a regimen with the potential for efficacy, but diminished toxicity.

This trial of peripheral androgen blockade has demonstrated that this approach is feasible, active, and durable. Although the entry criteria developed for this trial predated an understanding of the important prognostic importance of PSADT, this was nevertheless a carefully defined group, with PSA values between 1 and 10 ng/ml, no evidence of metastatic disease, and very limited prior hormonal exposure. This group of patients experienced declines in PSA of ≥80% in 96% of the patients, with 73% of such patients developing an undetectable PSA, defined as values <0.2 ng/ml. Furthermore, these patients had a rapid decline in their PSA levels, reaching nadir values at a median time of 3.2 months. While direct comparisons with historical data related to ADT are problematic, and the correlation of survival with PSA declines due to hormone therapy remains to be proven for this group of patients, the initial PSA declines in response to peripheral androgen blockade in these patients compares favorably with other reported hormonal maneuvers [21].[25]

The PSA declines observed appeared to be durable, with only 21 of 97 eligible patients (22%) having progressed through this therapy at a median follow up of 10 years. The survival of this group of patients appears robust, with 87% alive after five years, and median survival not reached at 10 years of follow-up. However, the true impact of this therapy cannot be ascertained, since a significant proportion of men with serologic progression will not necessarily die from prostate cancer[26].

Interestingly, after progression, the majority of patients responded to additional hormonal maneuvers. While the exact response proportion to anti-androgen withdrawal (AAWD) in the absence of ongoing gonadal androgen ablation has not been carefully tested, it is of interest to note that an AAWD response was seen in 14% of the patients in the current study, which is comparable to the response rate reported with AAWD in patients simultaneously treated with orchiectomy or an LHRH agonist and an anti-androgen[27–30]. Furthermore, 70% of patients treated with “salvage” LHRH agonist therapy had subsequent PSA responses, suggesting that initial response to peripheral androgen blockade may not compromise subsequent sensitivity to ADT. The durability of these subsequent PSA declines after salvage gonadal ablation is not known.

Importantly, the apparent disease control achieved with this regimen was not at the expense of significant toxicity. Overall, this regimen was extremely well tolerated. As expected, some gastrointestinal toxicity was seen, which was attributed to flutamide. Fifteen patients developed diarrhea, which led to dose reductions or removal from protocol therapy. Three patients had transaminase elevation sufficient to stop therapy. Nearly one half of the patients developed grade 1 or 2 gynecomastia or breast tenderness. This led to the withdrawal of consent in four patients. While further follow up is required, 5 potential cardiac deaths have been observed in 99 patients (5%) while on treatment with no clear treatment associated cardiac events noted. Although the exact incidence and relationship of cardiac events with ADT remains debated, it was reassuring that relatively few cardiac events were observed.

One of the potential advantages of peripheral androgen blockade is the ability to preserve potency. Unfortunately, the vast majority of patients enrolled in this study rated their ability to have or maintain an erection as poor at baseline. Perhaps this is attributable to the median age of 71 as well as the relative lack of potency sparing local therapeutic approaches being undertaken at the time most of these patients were treated. Therefore, preservation of potency could not be reliably measured.

The decrease in quality of life at the 6 month assessment appears to be driven by changes in the physical and functional well-being. Importantly, no significant changes were seen in emotional or social family well-being. Interestingly, patients reported improvement in the ability to relax and enjoy sexual activity and to become sexually aroused. As a group, the men rated their ability to have or maintain an erection as poor at baseline; therefore, it is not surprising that no improvement during therapy was seen in the ability to have or maintain an erection. This pattern suggests that the men were able to find alternate ways of enjoying sexual intimacy with their partners. An important question for future research is to determine whether men who have no or minimal erectile dysfunction prior to treatment would be able to maintain erectile function with peripheral androgen blockade.

In summary, peripheral androgen blockade with flutamide and finasteride has activity and minimal toxicity in prostate cancer patients with serologic progression. While the patients enrolled on this trial appeared to have outstanding and durable control of their cancer, while avoiding the toxicity and expense of ADT, this trial was non-comparative, and therefore it is difficult to be sure of the effectiveness of such therapy without a control group. Other treatment options for patients that qualified for this protocol include ADT with gonadal androgen ablation, as well as close observation. The results of a randomized trial of intermittent androgen suppression compared to continuous androgen suppression in nearly the same population of men recently described similar survival rates between the two groups.[31] The men in the intermittent arm, of which 35 % fully recovered their testosterone, reported higher quality of life scores. The largest reported analysis of observation of men with biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy was recently updated. [32] This retrospective study of 450 men who did not receive any additional therapies after surgery reported a median metastasis free survival (MFS) of 10 years. Their 5 year MFS of 67% compares to our 5 year 97% freedom from metastasis rate. Future studies in this group of men will benefit from further defining those with low, intermediate and high risk disease using contemporary risk calculations and perhaps yet to be defined biomarkers. With this in mind, further evaluation of the combination of flutamide and finasteride or a similar regimen in a controlled clinical trial is warranted.

Acknowledgments

The research for CALGB 9782 was supported, in part, by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA31946) to the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (Monica M. Bertagnolli, M.D., Chair) and to the CALGB Statistical Center (Daniel J. Sargent, Ph.D., CA33601). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

The following institutions participated in this study:

Cancer and Leukemia Group B Statistical Office, Durham, NC, (Daniel J. Sargent, Ph.D., supported by CA33601)

Christiana Care Health Services, Inc., CCOP, Wilmington, DE, (Stephen S. Grubbs, M.D., supported by CA45418)

Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, (Harold J Burstein, M.D., Ph.D., supported by CA 32291)

North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, NY

The Ohio State University Medical Center, Columbus, OH, (Clara D. Bloomfield, M.D., supported by CA 77658)

Hematology-Oncology Associates of Central New York CCOP, Syracuse, NY, (Jeffrey Kirshner, M.D., supported by CA45389)

University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, (Charles Ryan, M.D., supported by CA 60138)

University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, (Hedy L Kindler, M.D., supported by CA 41287)

University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, (Bruce A. Peterson, M.D., supported by CA16450)

University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, (Anne Kessinger, M.D., supported by CA77298)

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, (Thomas Shea, M.D., supported by CA47559)

University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, (Steven M Grunberg, M.D., supported by CA77406)

Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, (David D Hurd, M.D., supported by CA03927)

Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, (Nancy L. Bartlett, M.D., supported by CA77440)

Western Pennsylvania Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, (John Lister, M.D.)

References

- 1.Han M, et al. Long-term biochemical disease-free and cancer-specific survival following anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy. The 15-year Johns Hopkins experience. Urol Clin North Am. 2001;28(3):555–65. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goad JR, et al. PSA after definitive radiotherapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Urol Clin North Am. 1993;20(4):727–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephenson AJ, Eastham JA. Role of salvage radical prostatectomy for recurrent prostate cancer after radiation therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(32):8198–203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasquier D, Ballereau C. Adjuvant and salvage radiotherapy after prostatectomy for prostate cancer: a literature review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72(4):972–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisters LL, et al. Locally recurrent prostate cancer after initial radiation therapy: a comparison of salvage radical prostatectomy versus cryotherapy. J Urol. 2009;182(2):517–25. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.04.006. discussion 525–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loblaw DA, et al. Initial hormonal management of androgen-sensitive metastatic, recurrent, or progressive prostate cancer: 2006 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1596–605. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milbank AJ, Dreicer R, Klein EA. Hormonal therapy for prostate cancer: primum non nocere. Urology. 2002;60(5):738–41. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01867-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keating NL, O’Malley AJ, Smith MR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(27):4448–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alibhai SM, et al. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy on cardiovascular disease and diabetes. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3452–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geller J. Effect of finasteride, a 5 alpha-reductase inhibitor on prostate tissue androgens and prostate-specific antigen. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71(6):1552–5. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-6-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson IM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(3):215–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andriole GL, et al. Effect of dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 362(13):1192–202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Presti JC, Jr, et al. Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study to investigate the effect of finasteride (MK-906) on stage D prostate cancer. J Urol. 1992;148(4):1201–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36860-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLeod DG, et al. The bicalutamide 150 mg early prostate cancer program: findings of the North American trial at 7.7-year median followup. J Urol. 2006;176(1):75–80. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chodak G, et al. Single-agent therapy with bicalutamide: a comparison with medical or surgical castration in the treatment of advanced prostate carcinoma. Urology. 1995;46(6):849–55. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(99)80356-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fleshner NE, Trachtenberg J. Combination finasteride and flutamide in advanced carcinoma of the prostate: effective therapy with minimal side effects. J Urol. 1995;154(5):1642–5. discussion 1645–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ornstein DK, et al. Combined finasteride and flutamide therapy in men with advanced prostate cancer. Urology. 1996;48(6):901–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tay MH, et al. Finasteride and bicalutamide as primary hormonal therapy in patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(6):974–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esper P, et al. Measuring quality of life in men with prostate cancer using the functional assessment of cancer therapy-prostate instrument. Urology. 1997;50(6):920–8. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sherbourne CD. Social Functioning: Sexual problems measures. In: Stewart ALW, J E, editors. Measuring Functioning and Well-Being: The Medical Outcome Study Approach. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 1992. pp. 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenberger MA, et al. Bilateral orchiectomy with or without flutamide for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(15):1036–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810083391504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cella DF, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stephenson AJ, et al. Predicting the outcome of salvage radiation therapy for recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(15):2035–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vickers AJ, et al. Systematic review of pretreatment prostate-specific antigen velocity and doubling time as predictors for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(3):398–403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klotz LH, Canada BC, et al. A phase III randomized trial comparing intermittent versus continuous androgen suppression for patients with PSA progression after radical therapy: NCIC CTG PR.7/SWOG JPR.7/CTSU JPR.7/UK Intercontinental Trial CRUKE/01/013. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(suppl 7) abstr 3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pound CR, et al. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. Jama. 1999;281(17):1591–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.17.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly WK, Scher HI. Prostate specific antigen decline after antiandrogen withdrawal: the flutamide withdrawal syndrome. J Urol. 1993;149(3):607–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36163-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scher HI, Kelly WK. Flutamide withdrawal syndrome: its impact on clinical trials in hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(8):1566–72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.8.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Small EJ, et al. Antiandrogen withdrawal alone or in combination with ketoconazole in androgen-independent prostate cancer patients: a phase III trial (CALGB 9583) J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(6):1025–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sartor AO, et al. Antiandrogen withdrawal in castrate-refractory prostate cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial (SWOG 9426) Cancer. 2008;112(11):2393–400. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crook JOC, CJ Ding K, et al. A phase III randomized trial of intermittent versus continuous androgen suppression for PSA progression after radical therapy. 2011 ASCO Annual Meeting; Chicago. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antonarakis ES, et al. The natural history of metastatic progression in men with prostate-specific antigen recurrence after radical prostatectomy: long-term follow-up. BJU Int. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]