Abstract

The epigenetics and molecular biology of human embryonic stem cells (hES cells) have received much more attention than their architecture. We present a more complete look at hES cells by electron microscopy, with a special emphasis on the architecture of the nucleus. We propose that there is an ultrastructural signature of pluripotent human cells. hES cell nuclei lack heterochromatin, including the peripheral heterochromatin, that is common in most somatic cell types. The absence of peripheral heterochromatin may be related to the absence of lamins A and C, proteins important for linking chromatin to the nuclear lamina and envelope. Lamin A and C expression and the development of peripheral heterochromatin were early steps in the development of embryoid bodies. While hES cell nuclei had abundant nuclear pores, they also had an abundance of nuclear pores in the cytoplasm in the form of annulate lamellae. These were not a residue of annulate lamellae from germ cells or the early embryos from which hES cells were derived. Subnuclear structures including nucleoli, interchromatin granule clusters, and Cajal bodies were observed in the nuclear interior. The architectural organization of human ES cell nuclei has important implications for cell structure – gene expression relationships and for the maintenance of pluripotency.

Keywords: ultrastructure, human embryonic stem cells, nuclear structure, chromatin organization, annulate lamellae, electron microscopy

INTRODUCTION

Human embryonic stem (hES) cells can develop into any cell type, giving them great potential for the treatment of disease [Ilic and Ogilvie, 2016; Panchision, 2016; Wu and Izpisua Belmonte, 2015]. This developmental plasticity also makes them important tools in the study of human development. A growing literature is providing an epigenetic and biochemical characterization of these cells, but ultrastructural analysis has lagged.

The differentiation of an embryonic cell into the many cell types of the adult organism requires extensive epigenetic modifications of the genome. These include changes in the spatial positioning of genes within the nucleus and in the condensation of silenced genes into heterochromatin, leaving patterns of nuclear architecture that are cell-type specific. A common pattern of gene silencing includes covalent modifications of DNA and chromatin proteins and the movement of the gene to the periphery of the nucleus, where heterochromatin is preferentially localized in many cell types. These changes in three dimensional genome organization and packaging may both reflect and cause developmentally-regulated patterns of gene expression.

The peripheral structures of the nucleus have received more attention as a growing list of diseases has been mapped to mutations in the lamin proteins or to mutations in lamin-associated proteins [Davidson and Lammerding, 2014; Gruenbaum et al., 2005; Worman and Bonne, 2007]. Ultrastructural characterization of hESCs initially concentrated on the nuclear periphery and on substructures that are normally associated with the nuclear periphery. In many cells this zone is where many genes are silenced by packaging into peripheral heterochromatin, condensed chromatin with physical connections to the nuclear lamina. Regions of the genome that are silenced over longer times are often packaged into condensed heterochromatin [Cooper, 1959; Heitz, 1928; Heitz, 1929]. Though the patterns of heterochromatin distribution in the mammalian nucleus are cell-type specific, most heterochromatin is located at the nuclear lamina between nuclear pores and adjacent to the nucleolus. Silencing of genes often correlates with their movement to peripheral heterochromatin [Zink et al., 2004] and activation of genes accompanies movement from the periphery to the nuclear interior [Chuang et al., 2006] by mechanisms that may involve transcription, actin, and myosin. The experimental tethering of gene loci to the lamina causes differential degrees of transcriptional repression, depending on the locus and experimental system [Finlan et al., 2008; Kumaran and Spector, 2008; Reddy et al., 2008]. The lamina participates in mechanical signaling from the microenvironment to the genome [Tajik et al., 2016].

Nuclear pores are peripheral nuclear structures but we have observed them in the cytoplasm of hES cells. Annulate lamellae are cisternal structures composed of nuclear pores embedded in a double membrane (reviewed in [Kessel, 1992]) which are occasionally observed in the cytoplasm of germ cells and early embryos. Though resembling the nuclear envelope, they are located in the cytoplasm and are often stacked. Annulate lamellae were first observed by electron microscopy in sea urchin eggs [Swift, 1956], rat spermatids [Palade, 1955], ootestes of snails, clam ovaries, and salamander larvae [Swift, 1956]. Even in this early work a clear pattern emerges; annulate lamellae are most abundantly seen in germ cells and early embryos. It was soon noted that they were absent in most somatic cells but sporadically observed in tumor cells [Binggeli, 1959; Schulz, 1957; Wessel and Bernhard, 1957].

In human oocytes, assembly of annulate lamellae accompanies pronucleus formation after fertilization [Rawe et al., 2003]. Similarly, in bovine oocytes annulate lamellae appear early in fertilization and in some cells may appear even before the formation of a nuclear envelope following fertilization [Sutovsky et al., 1998]. An abnormal clumping of annulate lamellae around both pronuclei and the internalization of annulate lamellae into pronuclei is a characteristic feature of human zygotes that will arrest at the two-pronuclei stage, a common cause for in vitro fertilization failure [Rawe et al., 2003].

We propose that there is an ultrastructural signature of pluripotent human cells. Elucidating the component features of this signature should be an important goal in stem cell and developmental biology, a goal we begin to address here. One important feature of hES cells distinguishing them somatic cells was the absence of heterochromatin. This was most obvious at the inside of the nuclear lamina. The nuclear lamina had associated chromatin, but this was euchromatin and not the peripheral heterochromatin. Heterochromatin formed only after hES cells were induced to differentiate. An unexpected characteristic of hES cells was the abundance of nuclear pores in the cytoplasm in the form of annulate lamellae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human embryonic stem cells were provided by the Human Embryonic Stem Cell Core Facility at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. These cells were from two NIH approved human embryonic stem cell lines, H1 (WA01) and H9 (WA09), originally obtained from WiCell Institute at the University of Wisconsin (Madison). Cells were grown in an undifferentiated state on feeder layers of gamma- irradiated (40 Gy) mouse embryo fibroblasts in medium containing DMEM/F12, 20% KnockOut-Serum Replacement (Gibco/Invitrogen), 1% non-essential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 4 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor. For differentiation into embryoid bodies, colonies were transferred to medium containing Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium, 20% fetal bovine serum, and 1% L-glutamine.

Electron Microscopy

For electron microscopy, human embryonic stem cells were grown on a MEF feeder layer on Thermanox coverslips (Nunc). Cells were fixed without washing with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (electron microscopy grade) in 0.1M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3 at 4°C for 1 hour, some were fixed an additional 1 to 4 hours at room temperature, then washed in the same buffer at 4°C overnight up to several days [Underwood et al., 2006]. Samples were postfixed in 1% osmium in 0.1M sodium cacodylate at 4°C for 30–50 min, washed again, and dehydrated in graded ethanols with propylene oxide as the intermediate solvent, and embedded with Epon resin. For samples compatible with EDTA regressive staining, 0.1M Sorensen’s phosphate buffer, pH 7.3 replaced the sodium cacodylate and osmium postfixation was eliminated. Human embryoid bodies differentiated from 8 to 49 days were processed for electron microscopy in the same way. The blocks with coverslips on the surface were immersed in liquid nitrogen to remove the coverslips, allowing the cells to remain on the surface of the block. Thin sections were stained with 1.4% (w/v) uranyl acetate in 40% ethanol and then with lead citrate.

For EDTA regressive staining [Bernhard, 1969; Kota et al., 2008], sections were stained with 5% (w/v) uranyl acetate for 3 minutes, destained in 0.2 M EDTA for 30 to 60 minutes, and then lead citrate stained [Knight, 1982] for 2.5 minutes.

For pre-embedment electron microscopic localization [Nickerson et al., 1990], cells on Thermanox coverslips were washed at 4°C in PBS, permeabilized with Cytoskeletal Buffer (10 mM Pipes, pH 6.8/300 mM sucrose/100 mM NaCl/3 mM MgCl2/1 mM EGTA) containing 0.5% Triton-X 100, 2 mM VRC (Vanadyl Ribonucleoside Complex) and 1 mM AEBSF (4-(2-Aminoethyl)-benzenesulfonyl fluoride, hydrochloride) at 4°C for 5 minutes, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Ted Pella) in Cytoskeletal Buffer containing VRC and AEBSF at 4°C for 40 minutes, washed twice in Cytoskeletal Buffer at 4°C, then stained with a mouse monoclonal antibody against SRm300. Control sections were not exposed to the first antibody. The second antibody was coupled to 5 nm gold beads [Nickerson et al., 1990]. Cells were then fixed with 2.5% Glutaraldehyde (Ted Pella) in 0.1M Sörensen’s Phosphate Buffer, pH 7.3 [Glauert, 1991] at 4°C for 1 hour, then washed twice in the same buffer, and held overnight at 4°C in the buffer before embedment.

Sections were imaged with a Philips CM10 electron microscope. Micrograph negatives were scanned and processed digitally for high resolution imaging. Some low resolution images were taken with a Gatan ES1000W Erlangshen CCD Camera. Measurements were made from scanned negatives using Photoshop. For nucleosome sizes, two orthogonal measurements were made from each structure and averaged.

Immunofluorescent Staining

To prepare cells for fluorescence and confocal microscopy, two different methods were applied:

Fixation/permeabilization

Cells were washed in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution before fixation with 4% formaldehyde in Cytoskeletal Buffer for 50 minutes. To improve antibody penetration, the cells were then permeabilized by using 0.5% Triton X-100 in Cytoskeletal Buffer for 5 minutes. All steps were performed at 4°C.

Permeabilization/fixation

After washing in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution, cells were incubated in 0.5% Triton X-100 in Cytoskeletal Buffer for 2 to 5 minutes. This step removes soluble proteins from both the cytoplasm and nucleus. Cells were later fixed in 4% formaldehyde in Cytoskeletal Buffer for 50 minutes. All steps were performed at 4°C.

Antibody Staining

Cells were stained with antibodies as described [Wagner et al., 2003] and imaged with a Leica SP laser scanning confocal microscope. The B4A11 monoclonal antibody against SRm300 [Blencowe et al., 2000; Blencowe et al., 1994; Wan et al., 1994] identified RNA splicing speckled domains and was available from Calbiochem/EMD.

The mAb414 monoclonal antibody was originally made by Laura Davis and Gunther Blobel [Davis and Blobel, 1986] and was commercially available from Covance (Richmond, CA). The anti-TPR monoclonal antibody 203-37 [Cordes et al., 1997; Frosst et al., 2002] was from Matritech Inc. (Newton, MA). Lamin A/C and Lamin B peptide antibodies were a gift of Nilabh Chaudhary and Gunther Blobel. Lamin A/C monoclonal antibody 636 was from Biomedia (Forster, CA). Lamin B monoclonal 101B7 was from Matritech Inc. (Newton, MA). Monoclonal antibodies against SRm300 [Blencowe et al., 2000; Blencowe et al., 1994] are available at Calbiochem/EMD (San Diego, CA).

Oil Red O staining was done as described [Koopman et al., 2001]. This procedure permits staining with or without permeabilization. Our experiments were done both ways.

RESULTS

Ultrastructural Analysis

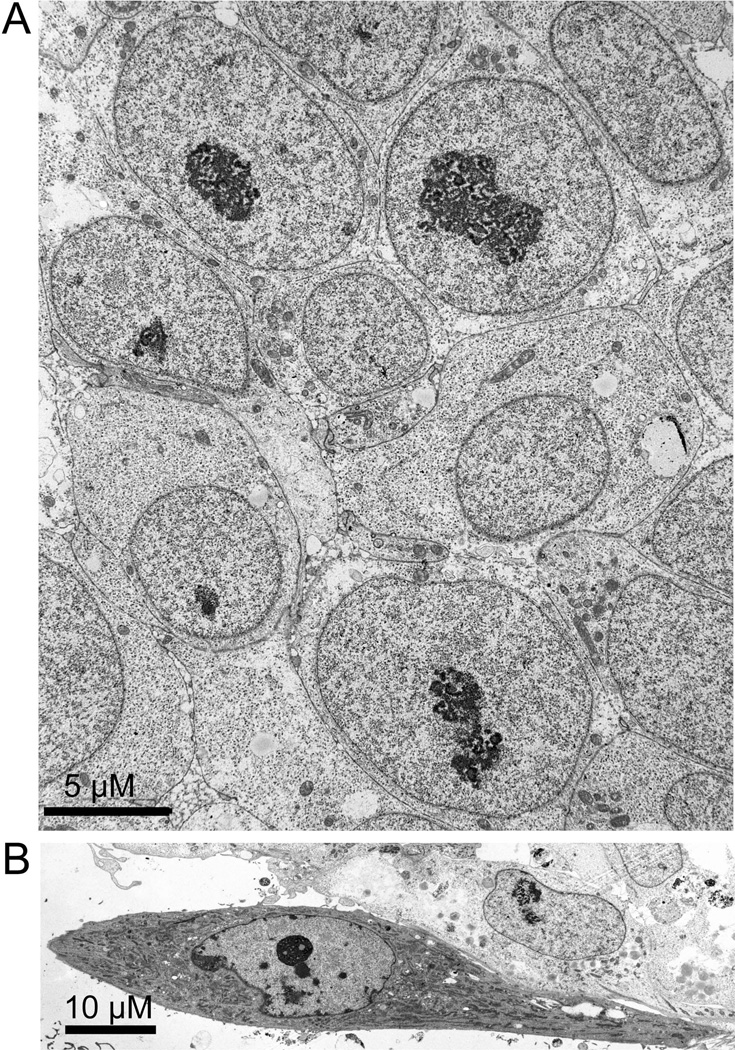

The ultrastructure of H1 and H9 hES cells was characterized. The features we report here were observed for both lines. hESCs grew on feeder layers of mouse embryonic fibroblasts as tightly packed colonies (Fig. 1). These colonies were easy to distinguish from the lawn of feeder mouse embryo fibroblasts by the distribution and density of cells. At higher magnification, they were easy to distinguish by the appearance of the cell, for example, by the absence of typical fibroblast features. The field of Fig. 1B has a feeder fibroblast at the edge of a colony. The fibroblast is clearly distinguishable by many features including a higher average electron density of the cytoplasm and the abundance of rough endoplasmic reticulum. In contrast, hESCs had a relatively undifferentiated cytoplasm, with a few mitochondria, abundant polyribosomes, and only occasional regions of endoplasmic reticulum. An unexpected feature of the hES cell cytoplasm was the presence of many lipid droplets in a high percentage of cells. The preservation and electron density of these varied with osmium fixation and are better seen at the higher magnification of Fig. 2. The number and distribution of lipid droplets was easier to evaluate in cultures stained with Oil Red O (Supplemental Fig. 1). There were abundant lipid droplets in the cytoplasm of most cells, with the highest concentrations in cells near the edge of the colony. These cellular organelles have roles in lipid storage, regulation of metabolism, and cell signaling [Bozza and Viola, 2010; Digel et al., 2010].

Figure 1.

A low magnification transmission electron micrograph of H1 hES cells. A colony of H1 cells was fixed and processed as described in Materials and Methods. (A) hES cells grew in tightly packed colonies. Cells were in close contact along all plasma membranes, though cell-cell junctions were not observed. Cells had a high ratio of nuclei to cytoplasm. Cell cytoplasm had an unusually simple ultrastructure, with few inclusions other than mitochondria and lipid droplets that stained slightly after osmium tetroxide postfixation. Nuclei were typically round and also had a simple ultrastructure, usually having a single large nucleolus and a striking absence of heterochromatin. Size bar = 5 µM

(B) In contrast, the ultrastructure of a mouse feeder cell at the edge of a hES cell colony was much more complex. The cytoplasm was filled with a much higher density of rough endoplasmic reticulum as well as a higher density of mitochondria. Nuclei had patches of heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery and had the centromeric heterochromatin characteristic of mouse cells. Size bar = 10 µM

Figure 2.

hES cells lack heterochromatin. This is a higher magnification view of a H9 hES cell that was in the center of a colony. The cytoplasm is simple with mitochondria (M) and lipid droplets (L) which are stained light grey by the osmium postfixation. As in many cells in this sample, an unusual cytoplasmic structure, an annulate lamellae (AL), was observed. The nucleus (Nu) had a large nucleolus and a striking absence of heterochromatin. Size bar = 2 µM

hES cell nuclei had one or two large nucleoli. Some sections were cut above or below the nucleolus and these nuclear sections lacked a nucleolus. The nucleoplasm of hES cells had a homogeneous texture of chromatin and did not have heterochromatin (Fig. 2).

Chromatin

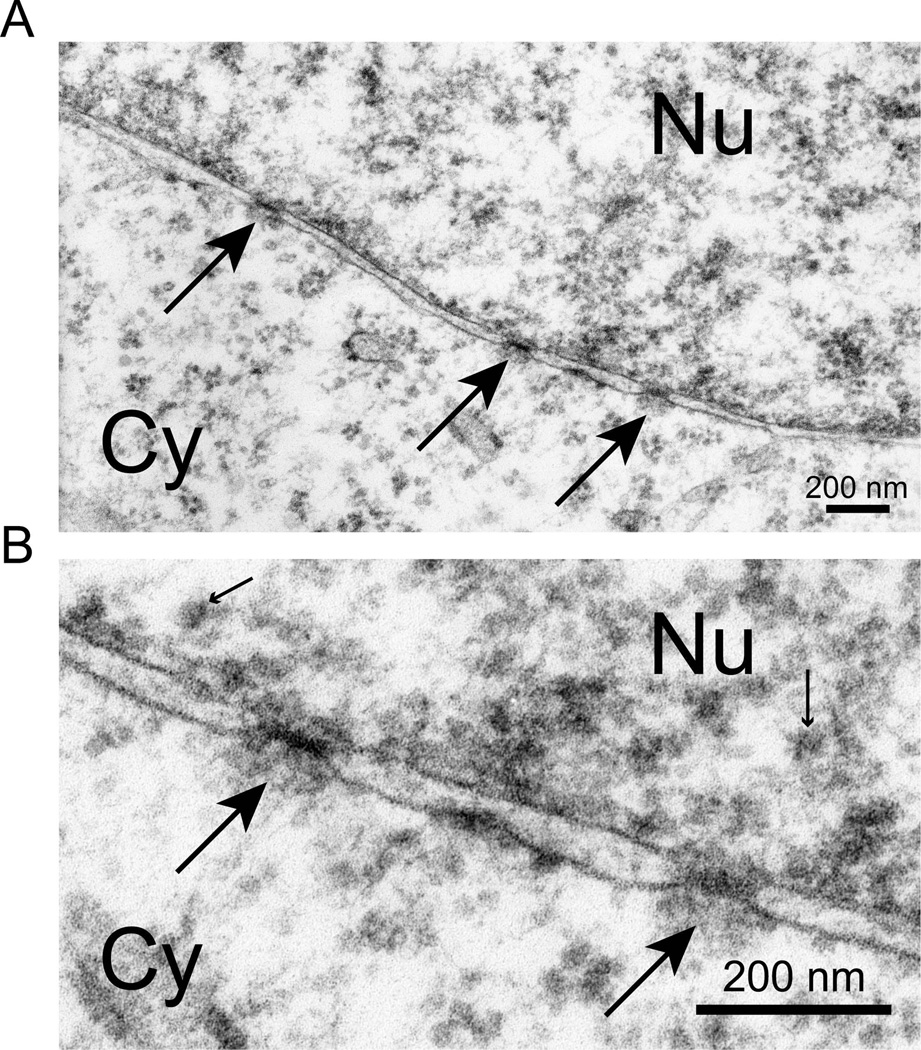

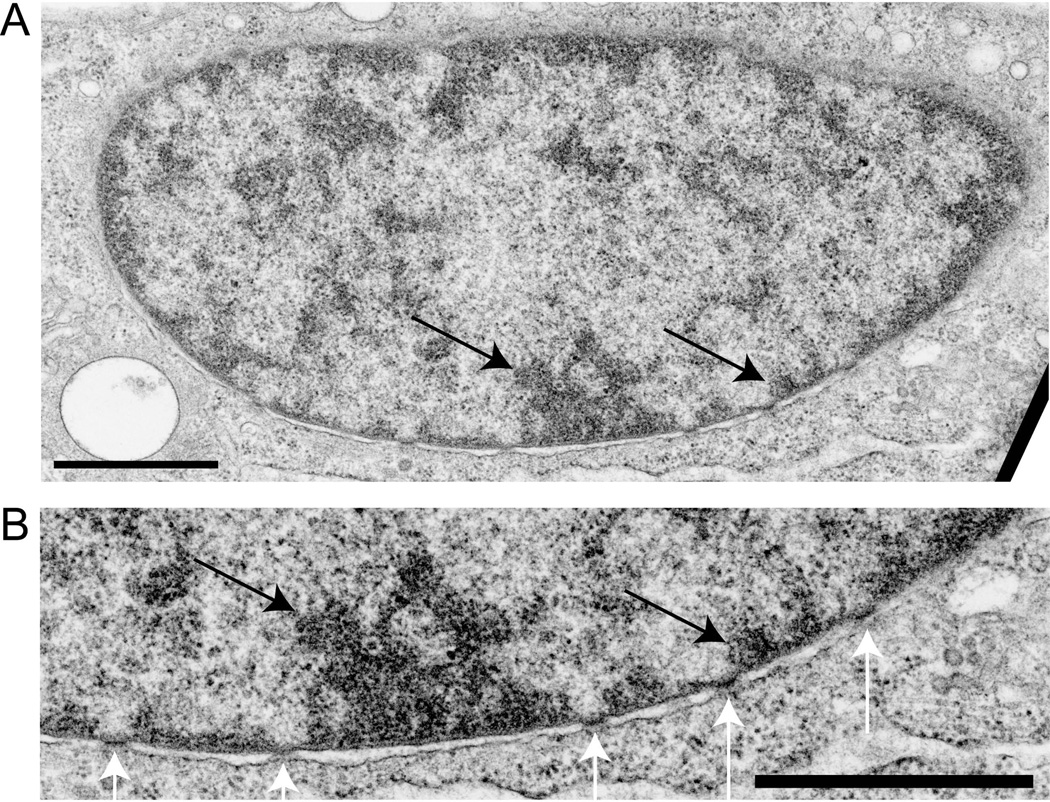

Heterochromatin has a cell-type distribution, but is observed in most cell types at the periphery of the nucleus where it is in contact with the nuclear lamina. This is the distribution of heterochromatin in the fibroblast of Fig. 1B. hESCs in contrast had no peripheral heterochromatin (Fig. 3). Chromatin appeared to be in contact with the nuclear lamina, but in the form of euchromatin. The density of chromatin adjacent to the nuclear lamina was indistinguishable to that in the nucleoplasm. When hES cells were provoked to differentiate into embryoid bodies by withdrawal of FGF and supplementation with serum, the formation of heterochromatin was observed in most cells (Fig. 4A and B). Most often, this was peripheral heterochromatin. Large peripheral masses of heterochromatin were easily distinguished from nucleoli at high magnification by the absence of characteristic features of the three regions of nucleoli (discussed below).

Figure 3.

hES cells have only euchromatin at the interior of the nuclear lamina. This is the edge of an H9 hES cell nucleus shown at two increasing magnifications. The cytoplasm (Cy) has few structures except free polyribosomes. The edge of the nucleus has the two membranes of the nuclear envelope that meet at nuclear pores (large arrows). The nuclear lamina on the nuclear side of the inner nuclear membrane is very thin and barely visible. Chromatin at the inner surface of the lamina was decondensed euchromatin, as in all cells in this study. The dominant feature of this chromatin was small masses of similar size (small arrows), all larger than the ribosomes observed in the cytoplasm. A random selection of these masses was measured as described in Materials and Methods in the micrograph of lower panel as 24.0 µM +/− 1.2µM (n=10), a size consistent with the identification of these as individual nucleosomes coated with the uranyl acetate stain. Electron dense masses of substantially larger size would be present in heterochromatin and these were missing. Both size bars = 200 nM

Figure 4. hES cells develop heterochromatin after differentiation into embryoid bodies.

Heterochromatin was observed in almost all cells. Embryoid body formation was induced by withdrawal of FGF and supplementation with serum. These images, at two magnifications, are for induced H9 hES cells at 7 weeks. In Panel B the black arrows mark peripheral heterochromatin and the white arrows show nuclear pores. Size bars = 1 uM

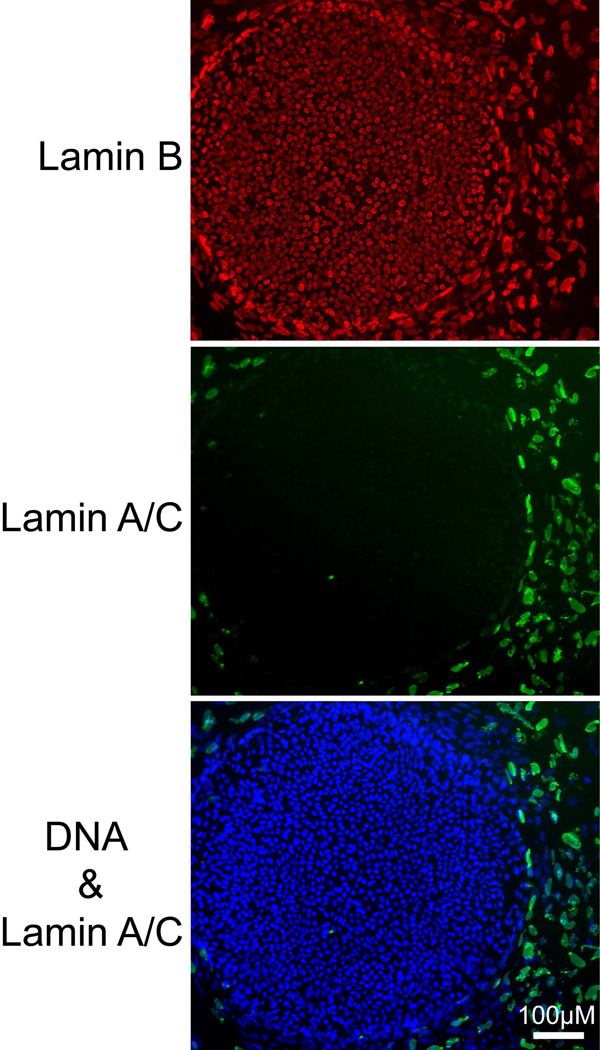

Peripheral heterochromatin forms by contacts of chromatin with lamins and lamin-associated proteins of the nuclear lamina [Dechat et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2001; Reddy et al., 2008; Schirmer, 2008; Towbin et al., 2009; Verstraeten et al., 2007]. In these connections, a group of proteins form complex links between chromatin, the nuclear lamina, the nuclear envelope, and the cytoskeleton, tying them together into an integrated structure. The expression of lamins A and C is a feature of more differentiated mammalian cell types [Lebel et al., 1987; Stewart and Burke, 1987]. hES cells lacked lamin A/C, as detected by immunostaining (Fig. 5). Lamin B was abundant and located in the nuclear lamina (Fig. 5). hES cells at the edge of colonies had weak traces of Lamin A/C staining. These peripheral cells may have started toward differentiation.

Figure 5. hES cells do not express Lamin A/C.

H1 cells grown on a coverslip were simultaneously stained for lamin A/C and Lamin B and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. The large colony of hESC cells stained for Lamin B but not Lamin A/C while the surrounding layer of mouse fibroblast feeder cells contained both Lamins A/C and B in their nuclear laminas. DNA was detected with DAPI.

Nuclear Pores

Nuclear pores were embedded in the double membrane of the nuclear envelope, which covered the nuclear lamina (Figs. 2 and 3). The distribution of pores in the peripheral structures of the nucleus was indistinguishable from that in fibroblasts or in human mammary epithelial cells [Underwood et al., 2006]. However, nuclear pores were also frequently observed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2). These pores were in arrays with each pore embedded in a double membrane. These structures are readily identifiable as annulate lamellae [Cordes et al., 1996; Kessel, 1963; Kessel, 1992] and are shown in different planes of section in Fig. 6. The membrane-pore arrays formed stacks of cisternae, typically with three or four layers of embedded pores. The double membranes of annulate lamellae were sometimes decorated with ribosomes, but only at their extensions where pores were absent (Fig. 6C). In these regions, the cisternae had the appearance of rough endoplasmic reticulum. Ribosomes were not observed near nuclear pores in annulate lamellae.

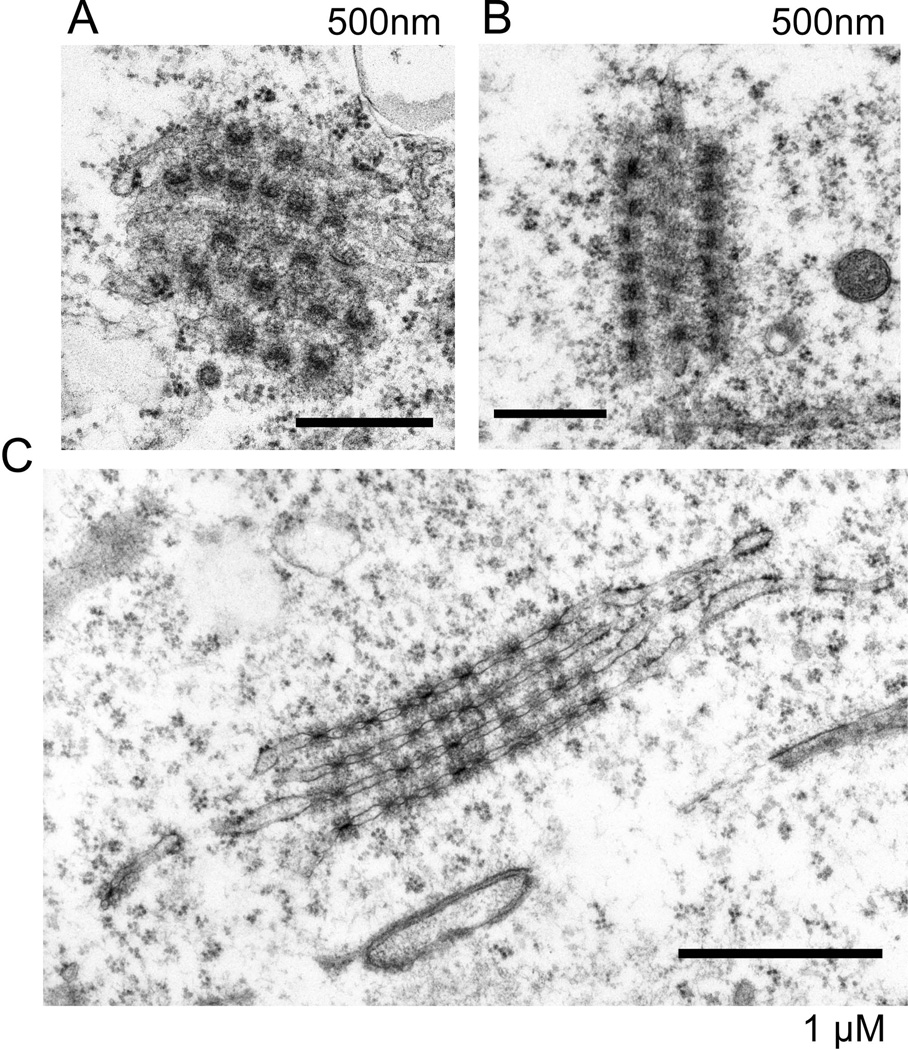

Figure 6. hESC cells had abundant annulate lamellae.

Electron microscopy revealed annulate lamellae in the cytoplasm of many sections for both H1 hES cells (Panel A) and H9 hESCs (Panels B and C). These are three typical views in different orientations. Nuclear pores were embedded in double membranes that were often stacked and were not connected to the nucleus. The size bars are 500nm for Panels A and B and 1 uM for Panel C.

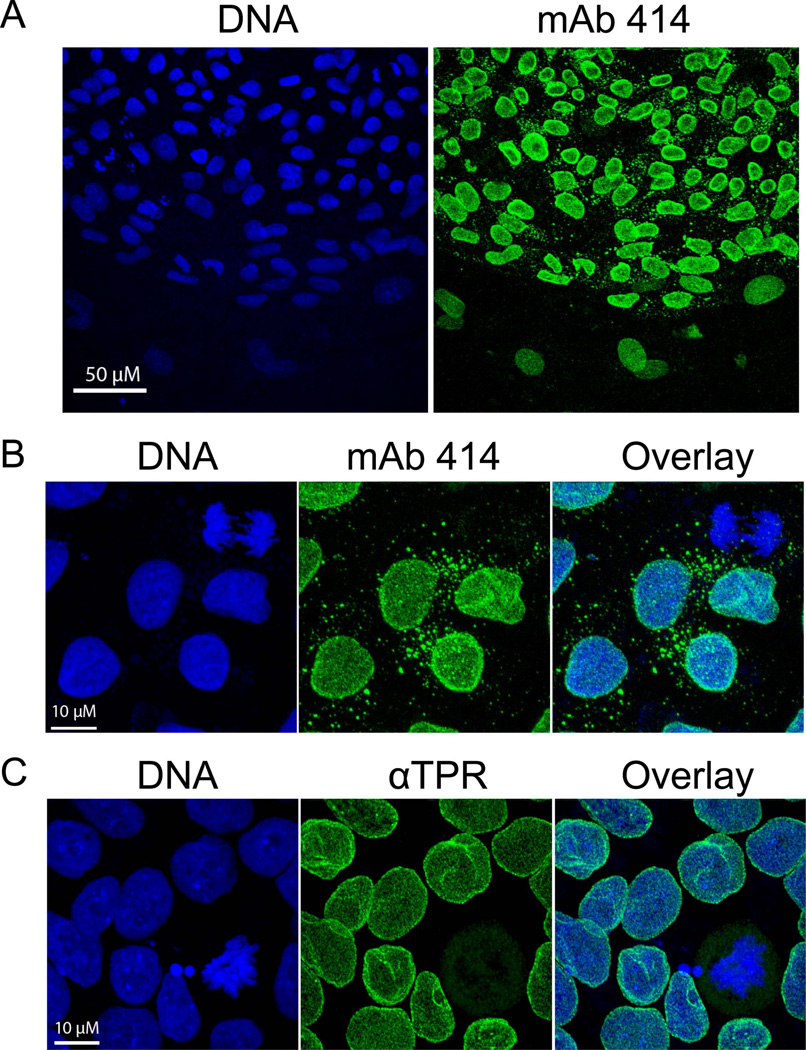

The large number of cytoplasmic electron microscopy sections having annulate lamellae suggested that these structures might be present in a majority of cells. Electron microscopy images only a thin section through a cell, making counting difficult. When annulate lamellae were detected by immunofluorescent staining with the antibody mAb414 [Davis and Blobel, 1986; Sukegawa and Blobel, 1993] which recognizes p62 and related nucleoporins with FxFG repeats all cells had cytoplasmic structures containing nucleoporins (Fig. 7 A and B). Annulate lamellae detected in this way were well distributed through the cytoplasm. An antibody specific for TPR [Cordes et al., 1997], a protein associated with nuclear pores and debatably forming filamentous projections into the nuclear interior [Cordes et al., 1997; Frosst et al., 2002], stained pores at the nuclear surface but did not stain any in the cytoplasm (Fig. 7C). It has been reported that nuclear pores in cytoplasmic annulate lamellae lack TPR [Cordes et al., 1997].

Figure 7. hESC cells had nuclear pores in the cytoplasm that contained FxFG repeat nucleoporins but not TPR.

Presented are representative maximum intensity confocal projections of H9 hES cells (Panels A and B) and H1 hESC cells (Panel C). Most nuclear pores were in the nuclear lamina but annulate lamellae were observed as small masses in the cytoplasm of most cells that stained with the MAB414 antibody recognizing nucleoporin p62 and related FxFG nucleoporins [Davis and Blobel, 1986; Sukegawa and Blobel, 1993]. They were not recognized by an antibody specific for TPR, a protein in filamentous projections on the nucleoplasmic face of nuclear pores [Cordes et al., 1997]. DNA was detected by DRAQ5 staining.

Nucleoli

hES cells had large, decondensed nucleoli (Fig. 8). Subregions within nucleoli were more easily distinguishable than we have typically observed in somatic cells. Every nucleolar section had a clear delineation of regions, while finding this in a somatic cell, for example a mammary epithelial cell, requires searching [Underwood et al., 2006]. This difference may, in part, be attributable to the absence of hetereochromatin which, in many cell types, is located adjacent to nucleoli. This result is also consistent with the hypothesis that hES cells have not undergone the rRNA gene silencing and condensation within rDNA that is observed in somatic cells [Grummt and Pikaard, 2003].

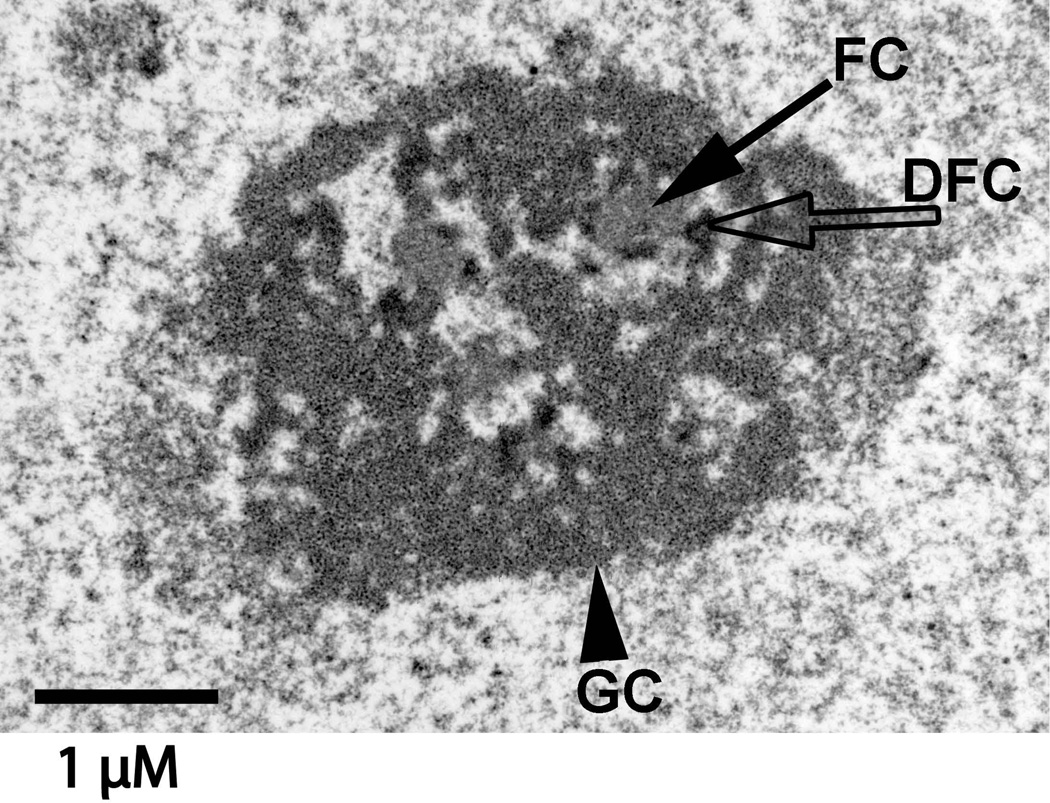

Figure 8. The ultrastucture of hES cell nucleoli was not obscured by adjacent heterochromatin.

This typical nucleolus was in an H1 hES cell. Subdomains of nucleoli were easily discerned. These were fibrillar centers (FCs), dense fibrillar components (DFCs), and granular components (GC). In one model of nucleolar function [Olson and Dundr, 2005], rDNA transcription takes place at the border of the FC and DFC while rRNA processing begins in the DFC. The granules in the GC are ribosomal subunits. Size bar = 1 uM

Interchromatin Granule Clusters

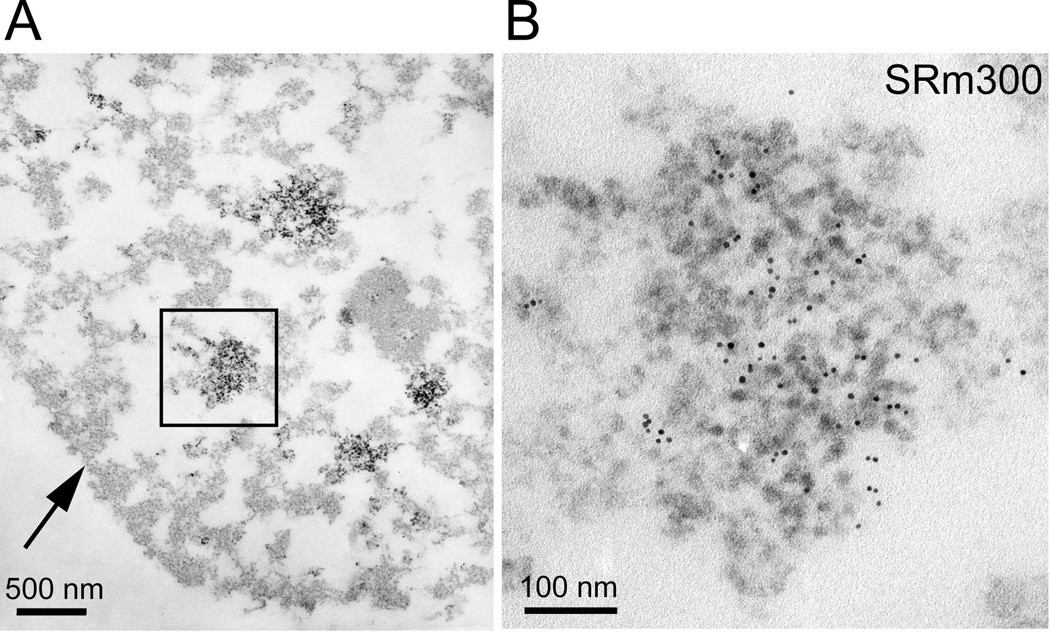

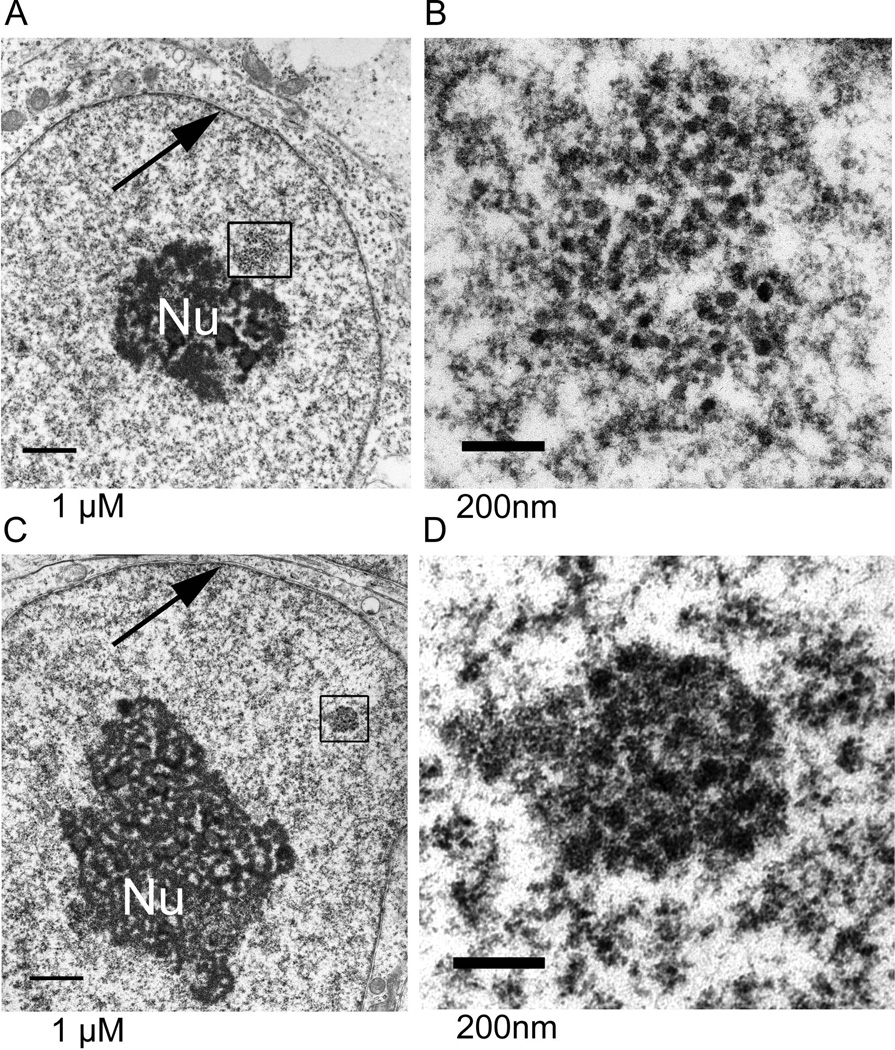

Interchromatin granule clusters [Monneron and Bernhard, 1969] were observed in hES cells (Fig. 9) by immunostaining with antibodies against RNA splicing factors and confocal microscopy. There were 20 to 40 speckled interchromatin granule cluster domains that were well distributed in the nucleoplasm as judged by fluorescence microscopy (not shown), a distribution similar to that observed for many somatic cells in tissue culture [Blencowe et al., 1994; Lelievre et al., 1998; Wagner et al., 2003; Wan et al., 1994].

Figure 9. hES cells have interchromatin granule clusters.

This H9 hES cell was stained with a monoclonal antibody recognizing SRm300 [Blencowe et al., 1998] and a secondary antibody coupled to 5nm gold beads before embedment and sectioning. The EDTA regressive counterstain is selective for RNA [Bernhard, 1969; Monneron and Bernhard, 1969]. Interchromatin granule clusters correspond to the RNA splicing speckled domains seen by fluorescence microscopy and contain high concentrations of RNA processing and export factors. Panel B is a higher magnification view of the interchromatin granule cluster marked in Panel A.

Small Nuclear Bodies

A variety of small nuclear bodies were observed (Fig. 10). Most common were loose clusters of granules that resembled the perichromatin granules first identified in somatic cells [Monneron and Bernhard, 1969] (Fig. 10 A and B). These might alternatively correspond to the PML bodies previously observed by light microscopy which were sometimes elongated and sometimes had a rosette structure [Butler et al., 2009].

Figure 10. Nuclear bodies observed in hES cells.

(A and B) Many nuclei, as in this H9 hES cell, had loose clusters of granules that resembled perichromatin granules [Monneron and Bernhard, 1969]. (C and D) As seen in this H1 hES cell, structures of closely clustered connected granules surrounded by a halo region with a lower concentration of chromatin were observed. These closely resembled the Cajal bodies of somatic cells [Cajal, 1903; Monneron and Bernhard, 1969; Morris, 2008]

Tighter collections of connected granules were identified as Cajal bodies [Cajal, 1903; Monneron and Bernhard, 1969; Morris, 2008] (Fig. 10 C and D). Cajal bodies were surrounded by a halo region with a lower concentration of chromatin, a feature found in many cell types.

DISCUSSION

Ultrastructural analysis of H1 and H9 hES cells showed an absence of peripheral heterochromatin. Further, these cells lack internal nuclear patches of heterochromatin. While “heterochromatin” has, in molecular biology, become shorthand for covalent modifications of histones that recruit transcriptional repressor complexes, the only direct observation of its distribution and density requires electron microscopy. Many genes in H9 hES cells have heterochromatin-promoting histone H3K27 trimethylation. These genes recruit the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) subunit SUZ12 [Lee et al., 2006]. Yet, the same H9 hES cells have no heterochromatin by ultrastructural criteria (Fig. 2). This divergence between chromatin marks and higher order chromatin architecture may be a significant feature of pluripotency. The absence of heterochromatin was consistent with previous work showing a more homogeneous distribution of heterochromatin proteins in human ES cells [Butler et al., 2009], and electron spectroscopic imaging of mouse ES cells that showed a more uniform distribution of chromatin in 10nm fibers than is typical of differentiated cells [Ahmed et al., 2010]. Compared to human somatic cells, mouse cells have more prominent peri-centromeric heterochromatin in masses that are large enough to be observable by light microscopy. In mouse embryonic stem cells the DNA around centromeres is not condensed and is maintained in an open state by the pluripotency factor Nanog [Novo et al., 2016]. The absence of heterochromatin in hES cells may contribute to cell pluripotency by keeping the entire genome in a transcriptionally permissive euchromatic compartment [Cavalli and Misteli, 2013; Gaspar-Maia et al., 2011].

The absence of peripheral heterochromatin in hES cells may be a result, in part, of the absence of lamins A and C (Fig. 5). In fibroblasts induced to become pluripotent by ectopic expression of the four transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4, the lamin A/C gene is strongly repressed [Wernig et al., 2007] (http://www.ebi.ac.uk, experiment E-MEXP-1037). Upregulation of lamin A/C is an early marker of human and mouse ES cell differentiation [Constantinescu et al., 2006]. The gene from which lamins A and C are both produced is in a bivalent chromatin conformation in murine ES cells [Bernstein et al., 2006]. This conformation has smaller interior regions of transcription activating histone H3 K4 methylation embedded in larger transcription repressing histone H3 K27 methylation regions and is hypothesized to keep important developmentally regulated genes poised for activation, but silent, in ES cells [Bernstein et al., 2006].

Lamins A and C, alternatively spliced from the same gene, are necessary for the development of normal peripheral heterochromatin [Galiova et al., 2008]. The periphery of the nucleus has a large number of protein connections between (from inside to outside) chromatin, the nuclear lamina, the two membranes of the nuclear envelope, and the cytoskeleton. The nuclear lamina is, therefore, an essential scaffold in the architectural organization of the cell. Lamins A and C may directly bind chromatin [Baricheva et al., 1996; Luderus et al., 1994]. They are indirectly bound to chromatin through multiple linkage proteins such as BAF, Emerin, LAP2α, and others (reviewed in [Andres and Gonzalez, 2009; Gruenbaum et al., 2005; Parnaik, 2008; Schirmer, 2008; Towbin et al., 2009]). A significant portion of the underlying architectural support for peripheral heterochromatin is therefore missing in hES cells.

Annulate lamellae were very abundant in the cytoplasm of hES cells (Fig. 7). Our results rule out any possibility that annulate lamellae are a residue of pre-assembled pores in the oocyte or early embryo from which they are derived since these hES cell lines are so many divisions downstream. There must be active processes in hES cells that continually generate these annulate lamellae. In oocytes of the salamander Necturus maculosus, annulate lamellae appear to be generated from vesicles budding from the nuclear envelope [Kessel, 1963]. The absence of lamin A/C in the nuclear lamina of hES cells might weaken the connections of nuclear pores to the nuclear surface and might facilitate such a budding mechanism. An alternative mechanism functions in some early mammalian zygotes where annulate lamellae and a pore-containing nuclear envelope can appear simultaneously after fertilization [Sutovsky et al., 1998]. Nucleocytoplasmic transport factors regulate nuclear pore assembly and the incorporation of these nuclear pores into annulate lamellae. In Xenopus eggs and egg extracts RanGTP induces formation of nuclear pores and annulate lamellae-like structures and this is inhibited by importin β [Harel et al., 2003; Walther et al., 2003].

The functions of annulate lamellae are insufficiently understood. The presence of annulate lamellae in early embryos, and especially in species where eggs and embryos have nuclear proteins prepositioned in the cytoplasm, has suggested that annulate lamellae might be a storage form of nuclear pores supporting the very rapid synthesis of many new nuclei during early development [Cordes et al., 1995]. This view was challenged by studies of syncytial Drosophila embryos showing that maternally contributed nucleoporins prepositioned in a solublized form in the cytoplasm, and not annulate lamellae, are the primary building blocks for new nuclear pores [Onischenko et al., 2004]. Recently, time lapse imaging of live Drosophila syncytial blastoderm embryos has established that cytoplasmic accumulations of nuclear pore complexes which are probably annulate lamellae integrate into the nuclear envelope and lamina in interphase [Hampoelz et al., 2016]. This process is fast, occurring over 1–2 minutes, and inserts batches rather than individual nuclear pores. Further, in this system nuclear pores in annulate lamellae are scaffolds with a subset of nucloporins, recruiting additional pore proteins after insertion into the nuclear envelope and lamina.

In cells lacking annulate lamellae nuclear pore biogenesis may occur postmitotically with the reformation of the nucleus, but interphase assembly of new pores from component parts into an intact nuclear lamina/envelope has long been documented [Doucet and Hetzer, 2010; Doucet et al., 2010; Maul et al., 1971].

Annulate lamellae clearly have functions beyond the simple storage of nuclear pores. For example, they have an involvement in Ca2+ signaling in support of Xenopus oocyte fertilization [Boulware and Marchant, 2005; Boulware and Marchant, 2008]. In this mechanism, annulate lamellae suppress Ca2+ signaling by sequestering the IP3 receptor. Other sequestration functions are possible. Nup133 is required for neural stem cell differentiation in the mouse embryo [Lupu et al., 2008]. It is possible that annulate lamellae sequester nucleoporins required for differentiation in the cytoplasm. In this case, annulate lamellae would be pluripotency- promoting structures. Sequestration of nucleoporins may have other effects. For example, levels of Nup96 affect cell cycle length and the expression of cell cycle regulated genes [Chakraborty et al., 2008; Wozniak and Goldfarb, 2008]. It is not known whether these effects require Nup96 to be at the nucleus. In Drosophila, a group of nucleoporins, including Nup98 and Sec13, interact with genes in the nucleoplasm [Capelson et al., 2010; Kalverda et al.]. Depletion of Nup98 or Sec13 decreases the expression of their respective target genes [Capelson et al., 2010; Kalverda et al.].

We propose that there is an ultrastructural signature that identifies pluripotent human cells. While occasional electron micrographs have appeared, there has been no extensive ultrastructural characterization of human ES cells. Most examinations of nuclear structure in pluripotent cells have used fluorescence microscopy [Butler et al., 2009]. There are significant advantages to using electron microscopy to characterize a new cell type. Electron microscopy has much higher resolution, and it does not require a preconceived idea or hypothesis since it is not necessary to pre-select a particular molecule for imaging. The architectural organization of human ES cells has important implications for cell structure – gene expression relationships. Features of regulatory machinery compartmentalization that may be unique to these cells offer functional insights into the cellular and molecular mechanisms that mediate pluripotency and competency for developing the complete complement of cell and tissue phenotypes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: National Cancer Institute Program Project grant P01 CA82834 (G. Stein).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to declare.

REFERENCES

- Ahmed K, Dehghani H, Rugg-Gunn P, Fussner E, Rossant J, Bazett-Jones DP. Global chromatin architecture reflects pluripotency and lineage commitment in the early mouse embryo. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10531. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres V, Gonzalez JM. Role of A-type lamins in signaling, transcription, and chromatin organization. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:945–957. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baricheva EA, Berrios M, Bogachev SS, Borisevich IV, Lapik ER, Sharakhov IV, Stuurman N, Fisher PA. DNA from Drosophila melanogaster beta-heterochromatin binds specifically to nuclear lamins in vitro and the nuclear envelope in situ. Gene. 1996;171:171–176. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard W. A new procedure for electron microscopical cytology. J. Ultrastruct. Res. 1969;27:250–265. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)80016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, Jaenisch R, Wagschal A, Feil R, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:315–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binggeli MF. Abnormal intranuclear and cytoplasmic formations associated with a chemically induced, transplantable chicken sarcoma. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1959;5:143–152. doi: 10.1083/jcb.5.1.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe BJ, Bauren G, Eldridge AG, Issner R, Nickerson JA, Rosonina E, Sharp PA. The SRm160/300 splicing coactivator subunits. Rna. 2000;6:111–120. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200991982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe BJ, Issner R, Nickerson JA, Sharp PA. A coactivator of pre-mRNA splicing. Genes & development. 1998;12:996–1009. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe BJ, Nickerson JA, Issner R, Penman S, Sharp PA. Association of nuclear matrix antigens with exon-containing splicing complexes. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:593–607. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware MJ, Marchant JS. IP3 receptor activity is differentially regulated in endoplasmic reticulum subdomains during oocyte maturation. Curr Biol. 2005;15:765–770. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulware MJ, Marchant JS. Nuclear pore disassembly from endoplasmic reticulum membranes promotes Ca2+ signalling competency. J Physiol. 2008;586:2873–2888. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza PT, Viola JP. Lipid droplets in inflammation and cancer. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2010;82(4-6):243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler JT, Hall LL, Smith KP, Lawrence JB. Changing nuclear landscape and unique PML structures during early epigenetic transitions of human embryonic stem cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009;107:609–621. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajal SR. Un sencillo método de coloración selectiva del retículo protoplásmico y sus efectos en los diversos órganos nerviosos de vertebrados e invertebrados. Tra. Lab. Invest. Biol. 1903;2:129–221. [Google Scholar]

- Capelson M, Liang Y, Schulte R, Mair W, Wagner U, Hetzer MW. Chromatin-Bound Nuclear Pore Components Regulate Gene Expression in Higher Eukaryotes. Cell. 2010;140:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli G, Misteli T. Functional implications of genome topology. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20:290–299. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty P, Wang Y, Wei JH, van Deursen J, Yu H, Malureanu L, Dasso M, Forbes DJ, Levy DE, Seemann J, Fontoura BM. Nucleoporin levels regulate cell cycle progression and phase-specific gene expression. Dev Cell. 2008;15:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang CH, Carpenter AE, Fuchsova B, Johnson T, de Lanerolle P, Belmont AS. Long-range directional movement of an interphase chromosome site. Curr Biol. 2006;16:825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantinescu D, Gray HL, Sammak PJ, Schatten GP, Csoka AB. Lamin A/C expression is a marker of mouse and human embryonic stem cell differentiation. Stem Cells. 2006;24:177–185. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper KW. Cytogenetic analysis of major heterochromatic elements (especially Xh and Y) in Drosophila melanogaster, and the theory of “heterochromatin”. Chromosoma. 1959;10:535–588. doi: 10.1007/BF00396588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes VC, Reidenbach S, Franke WW. High content of a nuclear pore complex protein in cytoplasmic annulate lamellae of Xenopus oocytes. Eur J Cell Biol. 1995;68:240–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes VC, Reidenbach S, Franke WW. Cytoplasmic annulate lamellae in cultured cells: composition, distribution, and mitotic behavior. Cell Tissue Res. 1996;284:177–191. doi: 10.1007/s004410050578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes VC, Reidenbach S, Rackwitz HR, Franke WW. Identification of protein p270/Tpr as a constitutive component of the nuclear pore complex-attached intranuclear filaments. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:515–529. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.3.515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PM, Lammerding J. Broken nuclei--lamins, nuclear mechanics, and disease. Trends in cell biology. 2014;24:247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LI, Blobel G. Identification and characterization of a nuclear pore complex protein. Cell. 1986;45:699–709. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90784-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechat T, Gotzmann J, Stockinger A, Harris CA, Talle MA, Siekierka JJ, Foisner R. Detergent-salt resistance of LAP2alpha in interphase nuclei and phosphorylation-dependent association with chromosomes early in nuclear assembly implies functions in nuclear structure dynamics. EMBO J. 1998;17:4887–4902. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Digel M, Ehehalt R, Fullekrug J. Lipid droplets lighting up: Insights from live microscopy. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(11):2168–2175. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet CM, Hetzer MW. Nuclear pore biogenesis into an intact nuclear envelope. Chromosoma. 2010;119:469–477. doi: 10.1007/s00412-010-0289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doucet CM, Talamas JA, Hetzer MW. Cell cycle-dependent differences in nuclear pore complex assembly in metazoa. Cell. 2010;141:1030–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlan LE, Sproul D, Thomson I, Boyle S, Kerr E, Perry P, Ylstra B, Chubb JR, Bickmore WA. Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frosst P, Guan T, Subauste C, Hahn K, Gerace L. Tpr is localized within the nuclear basket of the pore complex and has a role in nuclear protein export. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:617–630. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galiova G, Bartova E, Raska I, Krejci J, Kozubek S. Chromatin changes induced by lamin A/C deficiency and the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaspar-Maia A, Alajem A, Meshorer E, Ramalho-Santos M. Open chromatin in pluripotency and reprogramming. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2011;12:36–47. doi: 10.1038/nrm3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauert AM. Fixatives. In: Glauert AM, editor. Fixation, Dehydration and Embedding of Biological Specimens. New York: Elsevier North-Holland Biomedical Press; 1991. p. 14. editor^editors. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Wilson KL. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:21–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grummt I, Pikaard CS. Epigenetic silencing of RNA polymerase I transcription. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:641–649. doi: 10.1038/nrm1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampoelz B, Mackmull MT, Machado P, Ronchi P, Bui KH, Schieber N, Santarella-Mellwig R, Necakov A, Andres-Pons A, Philippe JM, Lecuit T, Schwab Y, Beck M. Pre-assembled Nuclear Pores Insert into the Nuclear Envelope during Early Development. Cell. 2016;166:664–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel A, Chan RC, Lachish-Zalait A, Zimmerman E, Elbaum M, Forbes DJ. Importin beta negatively regulates nuclear membrane fusion and nuclear pore complex assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4387–4396. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitz E. Das Heterochromatin der Moose. I Jahrb. Wissensch. Bot. I Jahrb. Wissensch. Bot. 1928;69:762–818. [Google Scholar]

- Heitz E. Heterochromatin, Chromocentren, Chromomeren (Vorlaufige Mitteilung) Ber. Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 1929;47:274–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ilic D, Ogilvie C. Human Embryonic Stem Cells-What Have We Done? What Are We Doing? Where Are We Going? Stem cells. 2016 doi: 10.1002/stem.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalverda B, Pickersgill H, Shloma VV, Fornerod M. Nucleoporins Directly Stimulate Expression of Developmental and Cell-Cycle Genes Inside the Nucleoplasm. Cell. 2010;140:360–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel RG. Electron Microscope Studies on the Origin of Annulate Lamellae in Oocytes of Necturus. J Cell Biol. 1963;19:391–414. doi: 10.1083/jcb.19.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel RG. Annulate lamellae: a last frontier in cellular organelles. Int Rev Cytol. 1992;133:43–120. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61858-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight DP. Cytological staining methds in electron microscopy. In: Lewis PR, Knight DP, editors. Staining Methods for Sectioned Material. New York: Elsevier North-Holland Biomedical Press; 1982. p. 44. editor^editors (42.43.42f) [Google Scholar]

- Koopman R, Schaart G, Hesselink MK. Optimisation of oil red O staining permits combination with immunofluorescence and automated quantification of lipids. Histochem Cell Biol. 2001;116:63–68. doi: 10.1007/s004180100297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kota KP, Wagner SR, Huerta E, Underwood JM, Nickerson JA. Binding of ATP to UAP56 is necessary for mRNA export. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:1526–1537. doi: 10.1242/jcs.021055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran RI, Spector DL. A genetic locus targeted to the nuclear periphery in living cells maintains its transcriptional competence. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:51–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel S, Lampron C, Royal A, Raymond Y. Lamins A and C appear during retinoic acid-induced differentiation of mouse embryonal carcinoma cells. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:1099–1104. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.3.1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KK, Haraguchi T, Lee RS, Koujin T, Hiraoka Y, Wilson KL. Distinct functional domains in emerin bind lamin A and DNA-bridging protein BAF. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4567–4573. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, Guenther MG, Levine SS, Kumar RM, Chevalier B, Johnstone SE, Cole MF, Isono K, Koseki H, Fuchikami T, Abe K, Murray HL, Zucker JP, Yuan B, Bell GW, Herbolsheimer E, Hannett NM, Sun K, Odom DT, Otte AP, Volkert TL, Bartel DP, Melton DA, Gifford DK, Jaenisch R, Young RA. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2006;125:301–313. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelievre SA, Weaver VM, Nickerson JA, Larabell CA, Bhaumik A, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Tissue phenotype depends on reciprocal interactions between the extracellular matrix and the structural organization of the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14711–14716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luderus ME, den Blaauwen JL, de Smit OJ, Compton DA, van Driel R. Binding of matrix attachment regions to lamin polymers involves single-stranded regions and the minor groove. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6297–6305. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupu F, Alves A, Anderson K, Doye V, Lacy E. Nuclear pore composition regulates neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation in the mouse embryo. Dev Cell. 2008;14:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul GG, Price JW, Lieberman MW. Formation and distribution of nuclear pore complexes in interphase. J Cell Biol. 1971;51:405–418. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monneron A, Bernhard W. Fine structural organization of the interphase nucleus in some mammalian cells. J Ultrastruct Res. 1969;27:266–288. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(69)80017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GE. The Cajal body. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:2108–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson JA, Krockmalnic G, He DC, Penman S. Immunolocalization in three dimensions: immunogold staining of cytoskeletal and nuclear matrix proteins in resinless electron microscopy sections. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:2259–2263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novo CL, Tang C, Ahmed K, Djuric U, Fussner E, Mullin NP, Morgan NP, Hayre J, Sienerth AR, Elderkin S, Nishinakamura R, Chambers I, Ellis J, Bazett-Jones DP, Rugg-Gunn PJ. The pluripotency factor Nanog regulates pericentromeric heterochromatin organization in mouse embryonic stem cells. Genes & development. 2016;30:1101–1115. doi: 10.1101/gad.275685.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson MO, Dundr M. The moving parts of the nucleolus. Histochemistry and cell biology. 2005;123:203–216. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0754-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onischenko EA, Gubanova NV, Kieselbach T, Kiseleva EV, Hallberg E. Annulate lamellae play only a minor role in the storage of excess nucleoporins in Drosophila embryos. Traffic. 2004;5:152–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.0166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palade GE. Studies on the endoplasmic reticulum. II. Simple dispositions in cells in situ. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1955;1:567–582. doi: 10.1083/jcb.1.6.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchision DM. Concise Review: Progress and Challenges in Using Human Stem Cells for Biological and Therapeutics Discovery: Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Stem cells. 2016;34:523–536. doi: 10.1002/stem.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnaik VK. Role of nuclear lamins in nuclear organization, cellular signaling, and inherited diseases. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;266:157–206. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(07)66004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawe VY, Olmedo SB, Nodar FN, Ponzio R, Sutovsky P. Abnormal assembly of annulate lamellae and nuclear pore complexes coincides with fertilization arrest at the pronuclear stage of human zygotic development. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:576–582. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E, Singh H. Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature. 2008;452:243–247. doi: 10.1038/nature06727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer EC. The epigenetics of nuclear envelope organization and disease. Mutat Res. 2008;647:112–121. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz H. Electron microscopic examination of mammary carcinoma in rats. Oncologia. 1957;10:307–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C, Burke B. Teratocarcinoma stem cells and early mouse embryos contain only a single major lamin polypeptide closely resembling lamin B. Cell. 1987;51:383–392. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90634-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukegawa J, Blobel G. A nuclear pore complex protein that contains zinc finger motifs, binds DNA, and faces the nucleoplasm. Cell. 1993;72:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90047-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutovsky P, Simerly C, Hewitson L, Schatten G. Assembly of nuclear pore complexes and annulate lamellae promotes normal pronuclear development in fertilized mammalian oocytes. J Cell Sci. 1998;111(Pt 19):2841–2854. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.19.2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift H. The fine structure of annulate lamellae. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1956;2:415–418. doi: 10.1083/jcb.2.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajik A, Zhang Y, Wei F, Sun J, Jia Q, Zhou W, Singh R, Khanna N, Belmont AS, Wang N. Transcription upregulation via force-induced direct stretching of chromatin. Nature materials. 2016 doi: 10.1038/nmat4729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin BD, Meister P, Gasser SM. The nuclear envelope--a scaffold for silencing? Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood JM, Imbalzano KM, Weaver VM, Fischer AH, Imbalzano AN, Nickerson JA. The ultrastructure of MCF-10A acini. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:141–148. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstraeten VL, Broers JL, Ramaekers FC, van Steensel MA. The nuclear envelope, a key structure in cellular integrity and gene expression. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:1231–1248. doi: 10.2174/092986707780598032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, Chiosea S, Nickerson JA. The spatial targeting and nuclear matrix binding domains of SRm160. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3269–3274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438055100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther TC, Askjaer P, Gentzel M, Habermann A, Griffiths G, Wilm M, Mattaj IW, Hetzer M. RanGTP mediates nuclear pore complex assembly. Nature. 2003;424:689–694. doi: 10.1038/nature01898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan KM, Nickerson JA, Krockmalnic G, Penman S. The B1C8 protein is in the dense assemblies of the nuclear matrix and relocates to the spindle and pericentriolar filaments at mitosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:594–598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernig M, Meissner A, Foreman R, Brambrink T, Ku M, Hochedlinger K, Bernstein BE, Jaenisch R. In vitro reprogramming of fibroblasts into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. Nature. 2007;448:318–324. doi: 10.1038/nature05944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel W, Bernhard W. Comparative electron microscopic examination of Ehrlich- and Yoshida ascites tumor cells. Z Krebsforsch. 1957;62:140–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worman HJ, Bonne G. "Laminopathies": a wide spectrum of human diseases. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2121–2133. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak RW, Goldfarb DS. Cyclin-like oscillations in levels of the nucleoporin Nup96 control G1/S progression. Dev Cell. 2008;15:643–644. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Dynamic Pluripotent Stem Cell States and Their Applications. Cell stem cell. 2015;17:509–525. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zink D, Amaral MD, Englmann A, Lang S, Clarke LA, Rudolph C, Alt F, Luther K, Braz C, Sadoni N, Rosenecker J, Schindelhauer D. Transcription-dependent spatial arrangements of CFTR and adjacent genes in human cell nuclei. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:815–825. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200404107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.