Abstract

The accurate detection of disease-related biomarkers is crucial for the early diagnosis and management of disease in personalized medicine. Here, we present a molecular imaging of human epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-expressing malignant tumors using an EGFR-specific repebody composed of leucine-rich repeat (LRR) modules. The repebody was labeled with either a fluorescent dye or radioisotope, and used for imaging of EGFR-expressing malignant tumors using an optical method and positron emission tomography. Our approach enabled visualization of the status of EGFR expression, allowing quantitative evaluation in whole tumors, which correlated well with the EGFR expression levels in mouse or patients-derived colon cancers. The present approach can be effectively used for the accurate detection of EGFR-expressing cancers, assisting in the development of a tool for detecting other disease biomarkers.

Keywords: Repebody, Epidermal growth factor receptor, Colon cancer, Molecular imaging, PET, Optical imaging.

Introduction

In the era of precision medicine, the understanding of oncogenic mechanisms has begun to influence risk assessment, diagnostic categories, and therapeutic strategies. Such paradigm has resulted in the increasing use of antibodies and drugs designed to counter the influence of specific molecular drivers 1. There is therefore a growing need to analyze specific targets and biomarkers in vivo, including distinct molecules, events, and processes 2. Targeted molecular imaging of malignant tissues using antibodies is a widely accepted approach for cancer diagnostics, providing a noninvasive tool to allow the repeated determination of the expression level of targets, and to identify the most suitable therapy for individual patients 3. However, intact antibody molecules are large glycoproteins (150 kDa), which have a limited application in molecular imaging due to their poor extravasation and low penetration into the tumor mass, combined with a slow clearance from the circulation, which causes a high background signal 4.

Smaller antibody fragments or engineered proteins provide a potential source of targeting domains for molecular imaging agents, allowing for improvements of the tumor-to-organ radioactivity concentration ratio and imaging contrast 5. As such, diverse antibody fragments 6-11 and protein scaffolds, including Affibody molecules 12, fibronectin-derived monobody 13, nanobodies 14, and peptides 15, have been explored for such uses.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is overexpressed in the majority of solid tumors, including gliomas, and those of the lung, colon, rectum, head and neck, pancreas, kidneys, ovaries, and bladder 16, 17. EGFR expression correlates with reduced survival of patients with glioma 18, breast 19, colorectal 20, non-small cell lung 21, prostate 22, bladder, cervical, esophageal, ovarian, and head and neck cancers 23. Recently, novel anticancer drugs have been developed that target EGFR family members and other growth factor receptors 24-26. Cetuximab is an example of a monoclonal antibody that has high affinity for, and blocks, the ligand-binding domain of EGFR, thereby preventing downstream signaling 24. It is a well-established therapeutic agent in oncology, and is increasingly used in clinics, mainly in combination with chemo- or radiotherapy 27. Despite the success of such inhibitors, large numbers of patients with EGFR-positive tumors fail to respond to current EGFR-targeted therapies, as a range of mutations (e.g., EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, PI3K, and PTEN) may contribute to intrinsic or acquired resistance 17. Several microtubule inhibitor-based antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that target EGFR are under investigation as therapeutic agents. It is expected that they will improve the activity of the approved EGFR antagonists by circumventing resistance mediated by downstream signaling mutations 28, 29.

Through modular engineering approaches, we previously developed a non-antibody protein scaffold, called repebody, which is composed of leucine-rich repeat (LRR) module 30. The repebody scaffold could be easily developed as high-affinity protein binders against a variety of epitopes through a phage display and modular engineering 30-33, offering some advantages over immunoglobulin antibodies or artificial protein binders in terms of binding affinity, ease of engineering, and specificity 30, 31, 33. In a previous publication, we reported a repebody with high affinity for EGFR as the protein binder, and presented protein-drug conjugates combining the repebody and monomethyl auristatin F (MMAF) in a site-specific manner 31. This study describes the development of repebody-based imaging probes for noninvasive and repeated assessment of EGFR expression in tumors using optical methods and positron emission tomography (PET). We sought to determine whether such imaging agents could yield a richer set of diagnostic information than can be achieved with traditional biopsy approaches.

Materials and methods

Cells

Human non-small cell lung carcinoma (H1650, HCC827, A549), human colorectal carcinoma (HT-29, SW620), and human melanoma (MDA-MB-435) cell lines were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). They were cultured in high-glucose DMEM and RPMI Medium and supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum FBS, 1% penicillin and 1% streptomycin. The cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

Western blot analysis

Cells and cancer tissues were lysed in protein extraction solution and the total protein samples (50 μg) were loaded onto 8% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and incubated with primary rabbit anti-EGFR antibody (Thermo scientific), and beta-actin (Santa Cruz) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz) for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive protein bands were visualized with an ECL detection kit (Santa Cruz) and quantified with a LAS-3000 Imager (Fujifilm).

Expression and purification of a repebody rEgA

Repebody rEgA was cloned into pET21a vector (Novagen) using NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. Origami B (DE3) host cell (Novagen) was used for the expression of repebody rEgA. After transformation, single colony was inoculated into LB media containing the appropriate antibiotics and cultured at 37 °C overnight. Next day, overnight culture was diluted 1:100 into fresh LB media and grown until OD600 reached about 0.5. Repebody expression was induced by addition of 0.5 mM of IPTG and further incubated at 18 °C for overnight. Cell harvest was conducted by using centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 20 min. After resuspending cell pellet, repebody purification was performed as described elsewhere 33. Briefly, soluble fraction of disrupted cells was obtained by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 60 min and residual insoluble fraction was removed by filtration through 0.22 micron filters. Repebody rEgA was isolated using Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen) and further purified on a Superdex75 (GE Healthcare). The resulting repebody rEgA was eluted with PBS (pH 7.4). Purity and concentration of repebody rEgA were checked using SDS-PAGE and UV-spectroscopy, respectively. The molecular mass of the repebody rEgA was determined by matrix assisted laser desorption ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS), as previously described 31.

Determination of binding affinity of rEgA

Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed for measuring the binding affinity of repebody rEgA toward human EGFR which were obtained as previously described 31. Repebody rEgA and soluble human EGFR (shEGFR) were eluted in filtered and degassed buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl. All proteins were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature. 7.5 µM of shEGFR was filled into the sample cell of MicroCal iTC200 (Malvern) and syringe contained 75 µM of repebody rEgA. Titration was conducted with 20 injections at 25 °C. The stirring speed and spacing were 1,000 rpm and 120 sec, respectively. The experiment result was fitted with a 1:1 binding model, using Origin software (OriginLab).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

For the target specificity of repebody rEgA, 10 µg/ml of soluble proteins (BSA, mouse EGFR, human EGFR, human HER2, human HER3 and human HER4) were coated onto 96 well MaxiSorp plate (SPL) at 4°C for overnight. All ErbB family proteins were Fc-fused form (R&D systems). After 3 times of PBS washing, plate blocking was carried out with blocking buffer (PBS (pH 7.4), 0.1% Tween-20 and 2% BSA) at room temperature for 1 hour. 100 µg/ml of repebody rEgA was dissolved in blocking buffer and added into each well for 1 hour. Anti-repebody rabbit antibody (1:5000; Abclon) and anti-rabbit antibody HRP conjugate (1:3000; Bio-Rad) were used as the detection antibody and the secondary antibody, respectively. After incubation of each antibody, plate washing was carried out 3 times with PBS (pH 7.4) and 0.1% Tween-20. Binding signals of repebody rEgA were developed by adding TMB solution (Sigma) and 1 M H2SO4 was subjected to stop the reaction. Developed signals were measured at 450 nm using Infinite M200 plate reader (Tecan). For a competitive ELISA, BSA and hEGFR (10 µg/ml) were coated onto a 96 well plate as described above. After blocking, a protein solution mixture (repebody rEgA and Cetuximab) was incubated at room temperature for 1 hour. The binding of rEgA and cetuximab towards EGFR was analyzed using anti-repebody rabbit antibody and anti-human Fab antibody HRP conjugate (1:3000, Bio-Rad), respectively.

Fluorescence dye labeling

The fluorescent dyes Flamma 496 vinylsulfone (496, Λabs-496 nm, Λem-516 nm) and Flamma 675 vinylsulfone (675, Λabs-675 nm, Λem-691 nm) were purchased from BioActs Corporation. To conjugate the fluorescent dyes to repebody (rEgA) and cetuximab, all proteins were dissolved in 0.1 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.0) at a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. The dyes 496 and 675 were dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml. All proteins were labeled with an excess of fluorescent probe (1:10 molar ratio of protein:dye), followed by incubation with continuous stirring at room temperature for 24 h in the dark. Unreacted dye molecules were removed from labeled proteins using centrifugal filtering (MWCO 10 kDa, Merck Millipore) with PBS buffer. The centrifugal filtration steps were performed at 1660 g for 20 min at room temperature and were repeated at least five times. The presence of the unreacted free dye was analyzed directly by SDS-PAGE. Quantitation of the protein-dye conjugation (dye:protein or F/P molar ratio) was calculated by separately determined molar concentrations of protein or protein-fluorophore conjugate on the basis of absorbance measurements (Table S1).

Immunofluorescence staining

The selected cells on glass coverslips were fixed in cold acetone for 10 min, incubated with 1% BSA/PBS for 10 min, and then stained with the rabbit anti-EGFR primary antibody (Thermo Scientific) and the goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with green FITC (Life Technologies). rEgA-496 was stained under the same conditions, except a secondary antibody was excluded. Fluorescence images from the slides were visualized and captured with a LSM510 microscope (ZEISS, Germany) and processed using LSM image software.

Flow cytometry analysis

Selected cells were stained with rEgA-496. Cellular fluorescence of 1 × 104 cells was analyzed using an Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). For confirmation of specific binding, rEgA was pre-incubated with naive rEgA (10 μM) for 30 min prior to incubation with rEgA-496 (0.1 μM).

Synthesis and analysis of 64Cu-NOTA-labeled rEgA

rEgA (500 µg, 0.018 µmol) was incubated in a 5:1 molar ratio with 2-(p-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N',N,"-triacetic acid trihydrochloride (p-SCN-Bn-NOTA, 2 µg, 3.6 nmol) in 1.0 M NaHCO3 buffer (10 µL, pH 9.2) for 24 h. The resulting product, NOTA-rEgA, was purified via a PD MiniTrap G-10 column. 64Cu (185-204 MBq) was then complexed with NOTA-rEgA in 0.1 M NH4OAc buffer at pH 5.5 and 40°C for 1 h. Finally, 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA was purified using a G-10 column and the radiochemical purity was determined by HPLC with analytical size-exclusion chromatography (Phenomenex, BioSep-SEC-S 2000, 300 × 7.80 mm; gradient: 70% solvent A [0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in D.W.] and 30% B [0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (MeCN)] to 30% solvent A and 70% solvent B for 30 min; flow rate: 1 mL/min; 218 nm; 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA and Cu-NOTA-rEgA Rt: 12.02 min). The analytic HPLC results revealed a single peak, suggesting the formation of one product (64Cu-NOTA-rEgA) identical to the reference compound (Cu-NOTA-rEgA). The total reaction time of the 64Cu-NOTA- rEgA was within 1 h, and the overall decay-corrected radiochemical yield was approximately 72 ± 2.5% (n = 10). Radiochemical purity was greater than 98% according to the analytic HPLC system. 64Cu-NOTA-labeled rEgA was passed through a 0.20 μm membrane filter into a sterile multi dose vial for in vivo experiments.

In vitro and in vivo serum stability of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA

For the in vitro stability test, 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA (0.37 MBq/100 μL) with or without an excess of EDTA (10 eq) was incubated with human serum (1.0 mL) in a 37°C water bath for 1, 6, 24, and 48 h, and was then analyzed by chromatography on ITLC-sg strips developed with 0.1 M NH4OAc (pH 5.5):MeOH in the ratio of 1:1. After development, the chromatographic strips were scanned on an automatic TLC scanner, and TLC was performed at various time points. All experiments were performed in triplicate. For the in vivo stability test, 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA (7.4 MBq/100 μL) was injected into the tail vein of normal nude mice, and blood was assessed at 15, 60, 120, and 240 min after intravenous injection (n = 12, with each measurement performed in triplicate). After centrifugation (16800 rpm, 20 min), the mouse serum was separated and analyzed by ITLC-sg.

Experimental cetuximab therapy in mice

Male BALB/c athymic nu/nu mice (5-6 weeks old) were purchased from the Orient company (Korea). Selected cells (HCC827, H1650, A549, and SW620; 5 × 106) in 50 μL PBS were inoculated subcutaneously into the right flank of mice. After about 21 days, mice were used for experiments when the tumor size reached 100 mm3. A 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA PET study was performed 1 day before starting the cetuximab treatment, with the PET image being acquired 6 h after intravenous injection of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA (7.4 MBq). To measure the antitumor activity of cetuximab in the xenograft mouse models, mice were treated with 30 mg/kg cetuximab twice a week via intraperitoneal injection. Tumor size and body weight were measured for 21 days. Tumor volume was determined using the formula: tumor volume = π/6 (length × width × height). All of the animal experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chonnam National University.

In vivo optical imaging of EGFR-expressing tumors

Mice were subcutaneously implanted with HT-29, H1650, HCC827, A549 and SW620. When the tumor size reached 100 mm3, 100 μL of 1 nmol rEgA-675 was injected into the mice through the tail vein. The fluorescence from rEgA-675 was monitored by IVIS 100 system (Caliper Life Science) after injection. In grafted HCC827 and SW620 tumor model, 100 μL of 1 nmol cetuximab-675 was injected into the mice through tail vein for comparison with rEgA-675. The fluorescence from Cetuximab-675 was monitored by cooled CCD camera after injection.

MicroPET analysis

MicroPET images were obtained by using a high resolution small animal PET-SPECT-CT scanner (Inveon, Siemens Medical Solutions). MicroPET imaging of the tumors in the mice (n = 6 per condition) was performed using intravenously injected 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA (7.4 MBq/200 µL, 29.24 ± 0.95 µg of rEgA), with the images being acquired at 10 min, 1 h, 6 h, 24 h, and 48 h after the injection. To verify the specificity of the rEgA binding to the EGFR-expressing tumor, the HT-29 and H1650 tumor-bearing mice were injected with 100 μL of 50 µmol naive rEgA and 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA on the subsequent day. Acquired images were reconstructed by three dimensional ordered subset expectation maximization (OSEM3D) algorithm using 16 subsets and any of four iterations. Image analysis was performed with PMOD software 34-36 (PMOD Technologies Ltd). We measured the maximum percentage of the injected dose per gram (%ID/g) of the tumor in each time point.

Biodistribution analysis

Biodistribution analysis 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA of was performed with murine models. Biodistribution in different organs was assessed in H1650 grafted tumor mice at 1, 6, and 24 h after intravenous injection of 7.4 MBq of radiotracer (29.24 ± 0.95 µg of rEgA; n = 6, each). Blood, heart, lung, liver, spleen, stomach, intestine, kidney, pancreas, muscle, and bone were sampled from the mice, and the radioactivity of each organ was measured with a γ-counter. Radioactivity determinations were normalized with weight of tissue and the amount of radioactivity injected to obtain the % ID/g.

Optical imaging of rEgA-675 of orthotopic colon cancer mouse models and histology

Six-week-old female BALB/c mice (n = 6) were given an intraperitoneal injection of azoxymethane (AOM; 10 mg/kg). One week later, the animals were administered 2% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) for 7 days via their drinking water, followed by maintenance on a basal diet and tap water for 7 days. This 3 week-cycle of DSS administration was repeated once again before colonoscopy. Colonoscopy was performed in AOM/DSS model to check whether colon tumors were formed adequately. rEgA-675 was intravenously injected into the AOM/DSS mice. Optical imaging was performed 2 days post-injection. Mice were sacrificed after in vivo imaging, and necropsy imaging was then performed. Excised each polyps were fixed in formalin and prepared as paraffin-embedded blocks. All the tissue sections were serially dissected to 5 µm thickness. The endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by PBS containing 1.5% H2O2. Pretreatment of the tissues for heat induced epitope retrieval was performed 5 min in a 125 °C pressure cooker with 10 mM citrate buffer, pH 6.0. The slides were incubated with the rabbit anti-EGFR primary antibody (Thermo Scientific) overnight at 4 °C and incubated with secondary antibody for 10 min at room temperature. Horseradish peroxidase detection system (Dako) was applied and visualized by chromogen reactions of the tissue sections that were initially treated with 0.02% diaminobenzidine (DAB).

Human colon tissue ex vivo stain

Colon adenocarcinoma samples from 15 patients were cut in half to compare the rEgA-675 staining with corresponding normal mucosa to act as a control. The tissues were put into the rEgA-675 solution, and the samples were incubated for 15 min, followed by washing with PBS for 5 min three times. Fluorescence images were obtained using the IVIS 100 system (Caliper Life Science).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v. 21. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used for statistical analysis, with a P value of < 0.05 considered as statistically significant. All data are expressed as means ± SD.

Results

EGFR-specific rEgA

We previously developed a repebody specific for the ectodomain of human EGFR (hEGFR) through a phage display and modular engineering approach 31. In our previous studies 31, 33, 37, we demonstrated that the repebody has a negligible immunogenicity and cytotoxicity in BALB/c mice.

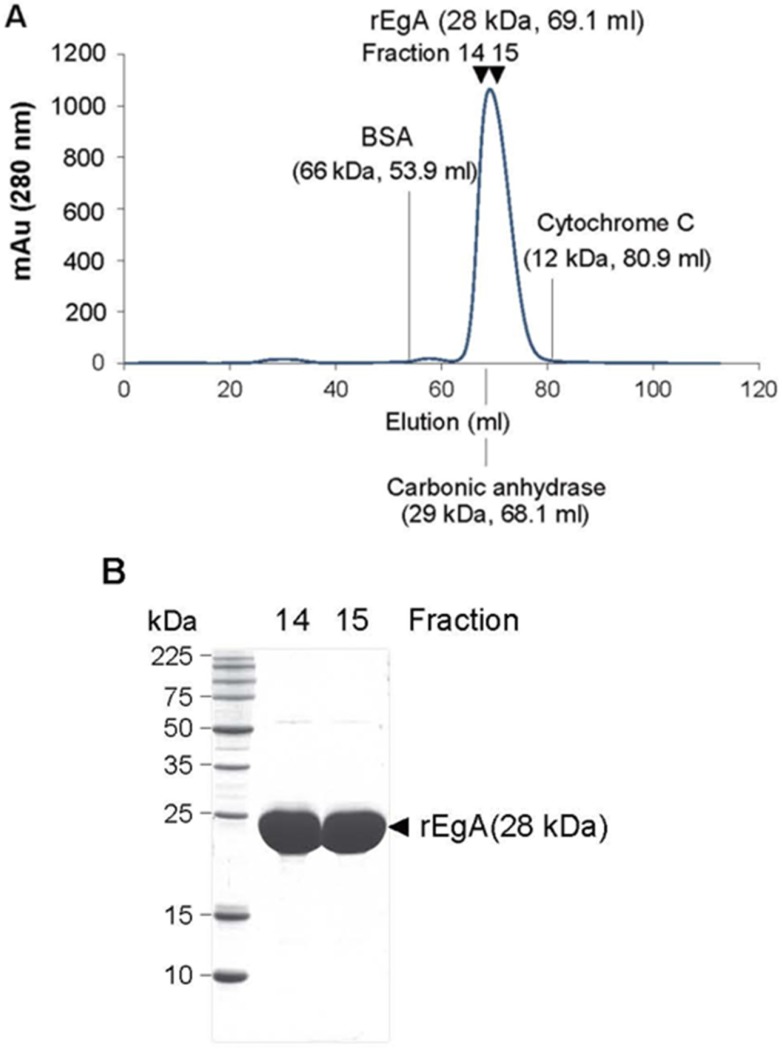

We tested the purity and molecular mass of newly purified rEgA through gel permeation chromatography (GPC) and MALDI-MS. The rEgA was eluted as a monomeric single peak without other detectable peaks (Fig. 1A). Moreover, SDS-PAGE data showed that rEgA has a purity of more than 95%, indicating that the rEgA was in a highly purified form (Fig. 1B). The molecular weight of rEgA calculated by MALDI-MS was 28273.538 (Fig. S1A), and the complete amino acid sequence is suggested in Fig. S1B.

Figure 1.

Purification of the repebody rEgA. (A) Gel Permeable Chromatography (GPC) profile of the repebody rEgA. After Ni-NTA purification, the resulting rEgA was subjected to GPC using superdex 75 column. BSA, Carbonic anhydrase and Cytochrome C were used as marker proteins. (B) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified rEgA. After GPC, eluted fractions (14 and 15) were further analyzed by SDS-PAGE for purity test.

The rEgA was shown to have a nanomolar affinity (KD = 9.18 nM; Fig. 2A) and high specificity for hEGFR, high binding to hEGFR, and moderate binding to mouse EGFR (mEGFR), but only weak cross-reactivity against other EGFR family members (Fig. 2B). We performed a competitive ELISA using cetuximab as a competitor to obtain an insight into the binding epitope of rEgA on EGFR. The result showed that the binding signal of rEgA against EGFR was significantly decreased when soluble cetuximab was co-incubated. This result indicates that rEgA and cetuximab share their binding epitopes (Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

EGFR-specific repebody rEgA. (A) Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed to measure the binding affinity of rEgA towards human EGFR. (B) Relative binding specificity of rEgA, bovine serum albumin (BSA), mouse soluble EGFR ectodomain (mEGFR), human soluble EGFR2 ectodomain (hHER2), human soluble EGFR3 ectodomain (hHER3), and human soluble EGFR4 ectodomain (hHER4), coated on a 96-well plate (10 µg/mL) for ELISA. A450 was determined. Error bars indicate standard deviations of triplicate experiments.

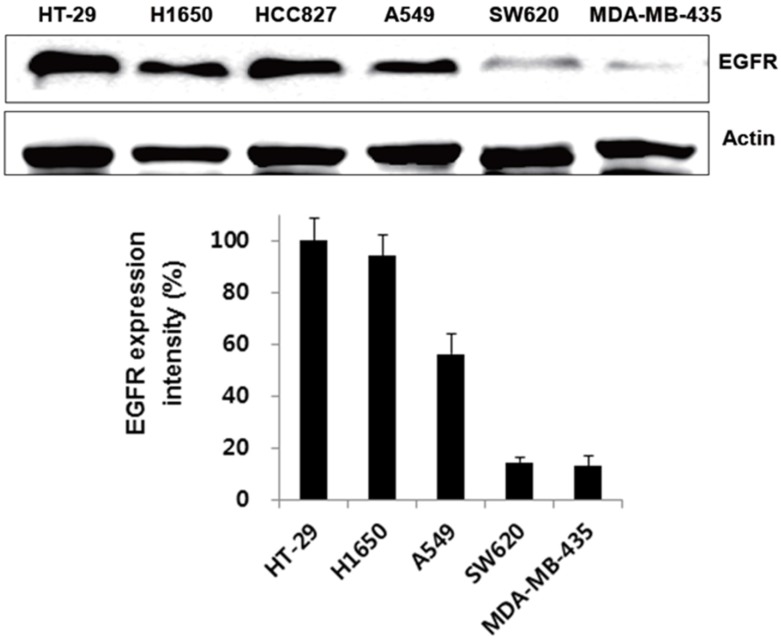

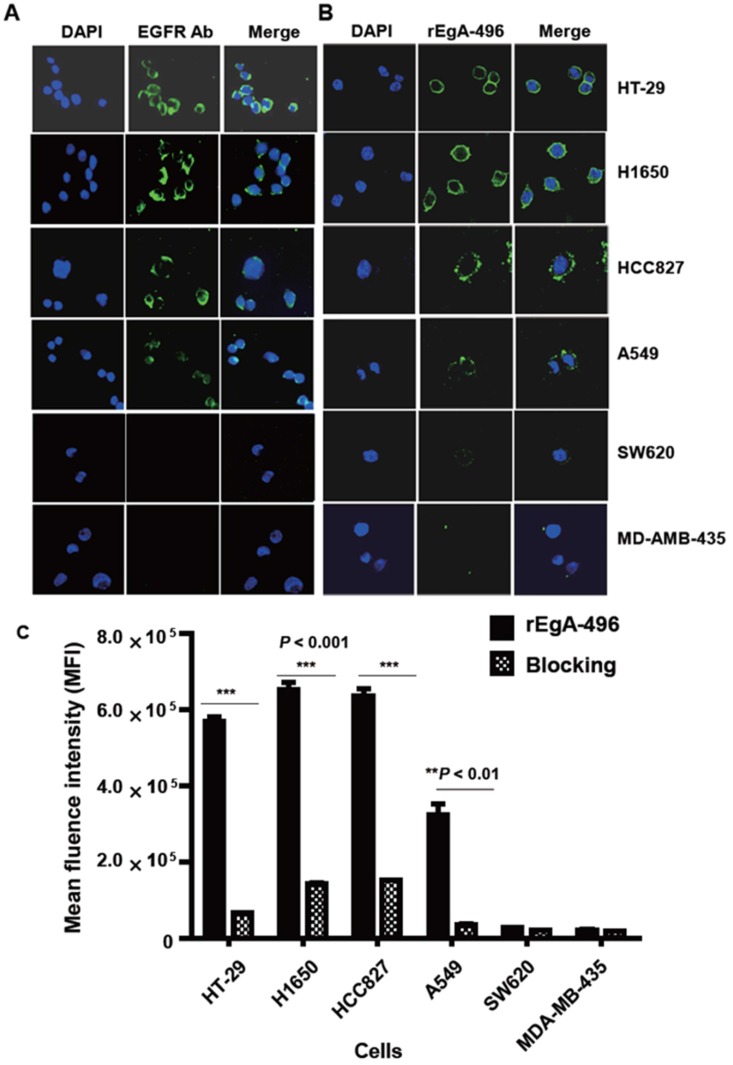

Specific binding of rEgA in vitro

We first verified its binding to EGFR-expressing tumors using the cultured human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines H1650, HCC827, and A549, and the human colon cancer cell line HT-29. Low EGFR-expressing human melanoma (MDA-MB-435) and colon cancer cells (SW620) were included as negative controls. Western blot analysis (Fig. 3) and immunofluorescence stain (Fig. 4A) revealed a strong expression of EGFR in the H1650, HCC827, and HT-29 cells, and moderate EGFR expression in the A549 cells, but showed virtually no presence in the SW620 and MDA-MB-435 cells. The binding of rEgA-496 was further examined using confocal microscopy after immunofluorescence staining; it was observed to bind strongly to H1650, HCC827, and HT29, and intermediately to A549, but not to SW620 and MDA-MB-435 cells (Fig. 4B). The binding specificity of rEgA was further examined using flow cytometry, and the same patterns were observed (Fig. 4C). Binding of rEgA to HT-29, H1650, HCC827, and A549 was significantly decreased by pretreatment with 10 μM naive rEgA (Fig. 4C). It was noted that in vitro rEgA-496 binding strongly correlated with EGFR expression levels.

Figure 3.

Expression of EGFR receptor in cancer cells by Western blot analysis. EGFR expression of selected cells were determined by Western blot analysis using EGFR antibody. Actin was included as a control. Protein bands intensity quantified with a LAS-3000 Imager. (EGFR expression intensity (%) = (EGFR/Actin) x 100

Figure 4.

Binding of rEgA-496 to various tumor cells. Binding of (A) EGFR antibody (left) and (B) rEgA-496 (right, 0.1 μM, green color) to the indicated tumor cells, as determined by confocal microscopy (400×) after immunofluorescence staining. The nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). (C) Binding of rEgA-496 (0.1 μM) to the indicated tumor cells measured by flow cytometry analysis. Cells were incubated with rEgA-496 (■). Cells were pre-treated with 10 μM naive rEgA, and then subsequently treated with 0.1 μM rEgA-496 (▩).

Characterization of 64Cu-NOTA-labeled rEgA

rEgA was reacted in a 5:1 molar ratio with p-SCN-Bn-NOTA in 1.0 M NaHCO3 buffer, and the NOTA-rEgA was then purified via a PD MiniTrap G-10 column. The number of NOTA per rEgA calculated on the basis of MALDI-MS was 0.78 ± 0.25 (n = 3), with the exception of non-conjugated rEgA (Fig. S3A). For the in vitro stability test, 64Cu was then chelated by NOTA-rEgA in 0.1 M NH4OAc buffer, and finally the 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA was purified using a G-10 column and the radiochemical purity was determined by HPLC. The analytical HPLC result suggested the formation of one product (64Cu-NOTA-rEgA) identical to the reference compound (Cu-NOTA-rEgA). The total reaction time for 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA was within 1 h. The overall radiochemical yield was approximately 72 ± 2.5% (n = 10) and the radiochemical purity was greater than 98% (Fig. S3B).

To determine the stability of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA, we performed an in vitro stability test with or without an excess of EDTA (10 eq), with the in vivo stability of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA measured for 4 h. When the 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA was incubated in human serum at 37°C for 48 h with or without an excess of EDTA (10 eq), the percentage of the remaining 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA (Rf: 0.05-0.1) was greater than 95%, indicating a relatively high in vitro stability (Fig. S4A, B). No metabolite or free 64Cu was detected in the serum of mice 15, 60, 120, and 240 min after intravenous injection of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA (n = 12, 96.48%, 98.8%, 96.83%, and 98.84%, respectively; Fig. S4C).

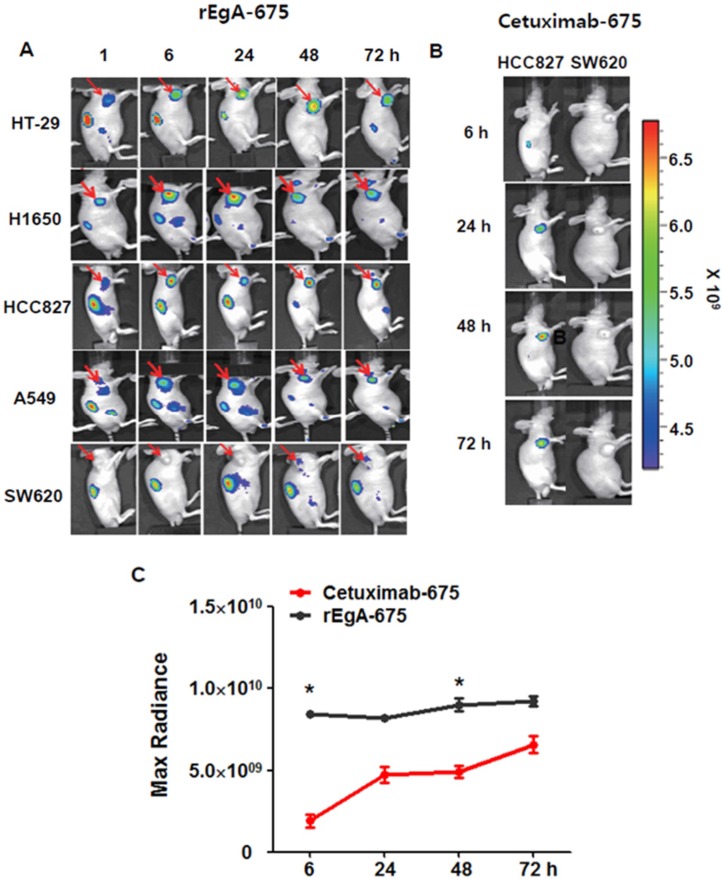

In vivo imaging of EGFR-expressing xenograft tumors using rEgA

We next assessed the utility and potential of rEgA as an imaging probe for the detection of EGFR-expressing tumors using xenograft tumor mice. Mice were ectopically implanted with HT-29, H1650, HCC827, A549 or SW620 cancer cells. When the tumor size reached approximately 100 mm3, rEgA-675 (100 μL of 1 nmol) was injected into the mice through the tail vein. Strong fluorescence signals were then detected at the grafted HT-29, H1650, HCC827cells, but not at the SW620 cell xenograft (Fig. 5A). The targeted tumor signal from rEgA-675 was compared with that from cetuximab-675 in HCC827 and SW620 bearing mice following intravenous injection (Fig. 5B). Both agents resulted in the detection of strong fluorescence signals from the HCC827 grafted tumors (Fig. 5A, B); however, during the observation period, the tumor fluorescence signal from rEgA was 2- to 4-fold stronger than that from cetuximab (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

In vivo imaging of rEgA-675. (A) Targeting of intravenously injected rEgA-675 (100 μL of 1 nmol) in mice grafted with tumors, determined using a cooled CCD camera after 24 h (n = 12 per condition). Arrows indicate grafted tumors. (B) In vivo optical imaging of HCC827 and SW620 grafts in mice (n = 6 per condition) after intravenous injection of cetuximab-675 (100 μL of 1 nmol), as indicated. The series of optical images were carried out at the indicated time points post-injection. Mice were subcutaneously implanted with HCC827 and SW620. (C) Quantification of fluorescence signals of HCC827 grafted tumors (B) (* P < 0.05).

Subsequently, we employed 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA for in vivo microPET imaging of EGFR-expressing cancer. We evaluated the uptake level of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA in strong (H1650 and HT-29), moderate (A549), and weak (SW620 and MDA-MB-435) EGFR-expressing xenografts. Uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA was initially detected after 1 h, peaked at 6 h, plateaued to 24 h, and then declined by 48 h (Fig. 6A, B). A higher level of uptake was detected in H1650 and HT-29 cells than in A549 cells. Negligible accumulation was detected in SW620 (%ID/g; 0.50 ± 0.04) and MDA-MB-435 (%ID/g; 0.34 ± 0. 06) cells (Fig. 6A, B). EGFR expression level (%) and 6 h PET uptake (%ID/g) demonstrated a good correlation (R2= 0.9154, P = 0.011; Fig. 6C). The tumor-to-organ ratio of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA uptake in HT-29 and H1650 xenografts also peaked at 6 hours (Table S2). Tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA increased from the 1 h level, with the highest uptake being observed at 6 h in HT-29, H1650, and A549 bearing mice. After injection of 100 μL of 50 µmol naive rEgA and 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA on the subsequent day, the radioactivity of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA in the tumor tissue significantly decreased at all time points, indicating the specificity of rEgA binding in vivo (Fig. 6A, B). Biodistribution results showed a trend similar to the microPET results, with a peak at 6 h (Table S3). However, the absolute value of microPET was lower than that of the biodistribution study, which was possibly due to the partial-volume effects of the microPET scanner 6. Taken together, the results demonstrate that rEgA has the utility and potential to visualize the status of EGFR expression in living subjects.

Figure 6.

Relative efficacy of in vivo MicroPET imaging of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA. (A) MicroPET imaging of HT29, H1650, A549, SW620 and MDA-MB-435 tumor-bearing mice (n = 6 per condition) using intravenously injected 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA. For blocking HT-29 and H1650 tumor-bearing mice (n = 6 per condition) were injected with 100 μL of 50 µmol naive rEgA 24 h before injection of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA. (B) On the subsequent day, the 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA was monitored using microPET at the indicated times post-injection (* P < 0.05). (C) Correlation of EGFR expression level (%) and 6 h PET uptake (%ID/g) by Pearson correlation method (R 2= 0.9154, P = 0.011).

Correlation between tumor suppression by cetuximab and 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA uptake

We next evaluated the correspondence between in vivo tumoral uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA and the therapeutic efficacy of cetuximab (30 mg/kg) to assess the implications of EGFR imaging study for the prediction of the therapeutic response of receptor-targeted therapy (e.g., ADCs) (Fig. S5). The tumor suppression rate of cetuximab in the HCC827 and H1650 xenografts, which exhibited high 64Cu-NOTA-rEgA uptake, was significantly stronger than in the A549 and SW620 xenografts, which showed only weak or no uptake. For grafted HCC827 and H1650 tumors, the cetuximab treatment suppressed tumor growth by 57% ± 9.6% compared with the PBS control groups. However, the cetuximab treatment had little effect on the growth of A549 tumors (22.2% ± 9.8%). The SW620 grafted mouse models demonstrated no suppression of tumor growth, as was expected.

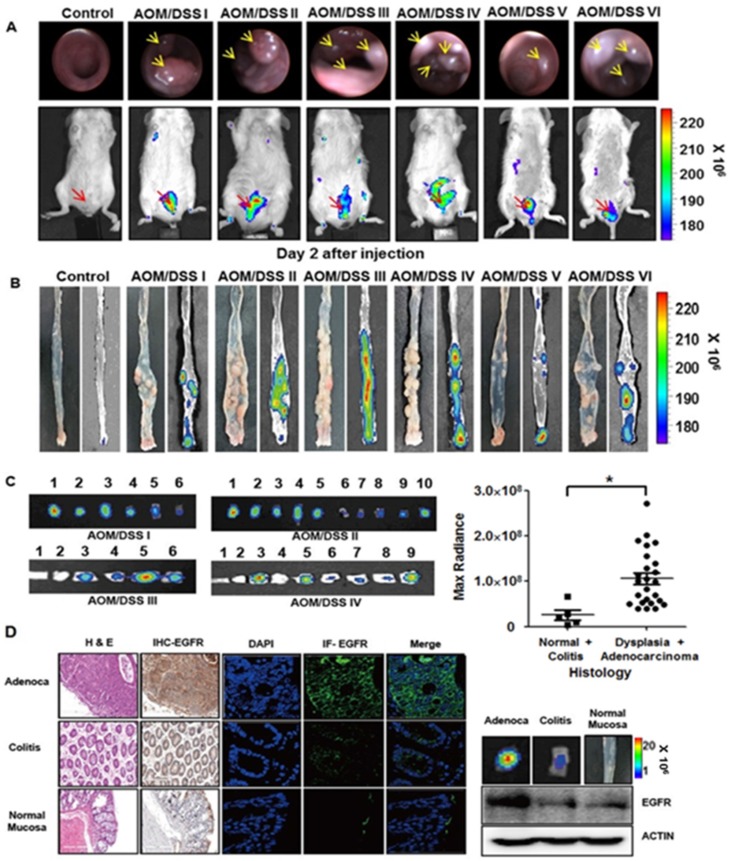

In vivo optical imaging of chemically induced colonic dysplasia

We further tested the binding of rEgA to tumors using chemically induced colonic dysplasia models in mice. Colonoscopy was performed in the AOM/DSS model mice to check whether colon tumors were adequately formed, and when a colonic mass was found, rEgA-675 was intravenously injected into the AOM/DSS mice and optical imaging was performed 2 days post-injection (Fig. 7A). Fluorescence signals were observed in the abdomina of AOM/DSS mice, but not in those of control mice (Fig. 7A). After sacrificing the mice, the rEgA-675 uptake in each colonic polyp was analyzed using necropsy imaging (Fig. 7B). Comparison of the necropsy imaging results with the pathology revealed strong accumulation of rEgA in dysplastic lesions, but weak or no accumulation in benign lesions and normal mucosa (Fig. 7C). Western blot analysis, and immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining, indicate that EGFR expression was well correlated with the fluorescence signals (Fig. 7C-D and Fig. S6).

Figure 7.

Optical imaging of rEgA-675 in an AOM/DSS orthotopic mouse tumor model. (A) rEgA-675 (100 μL of 1 nmol) was intravenously injected into AOM/DSS mice and they were imaged at day 2 post-injection (n = 6). Arrows indicate the tumors. (B) Mice were sacrificed after in vivo imaging, and necropsy imaging was then performed. (C) Colonic polyps were removed and histologic results were correlated with optically measured avidity (* P < 0.01). (D) EGFR expression of colonic polyps was assessed by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining (left), immunofluorescence (IF) staining and Western blot analysis (right) using EGFR antibody. (Adenoca: Adenocarcinoma)

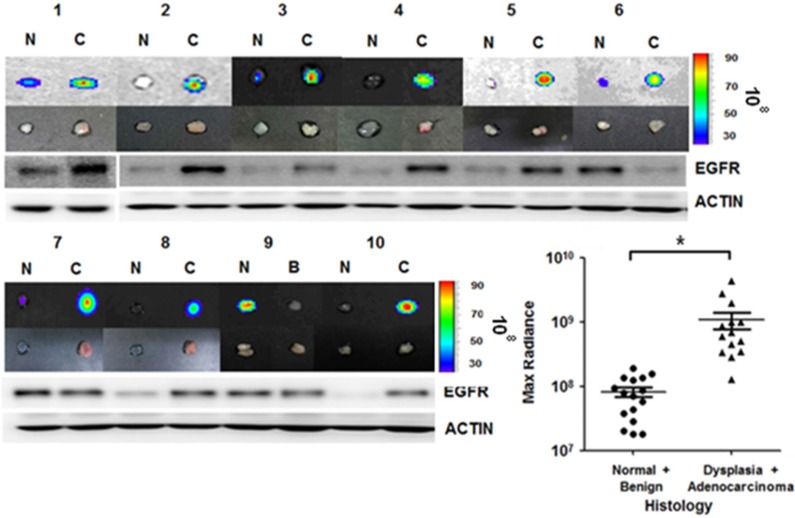

Ex vivo imaging of rEgA-675 in patient-derived colon cancer tissue

We further applied the rEgA-675 probe to human specimens taken by clinical endoscopic resection. Endoscopic biopsy was used to simultaneously take samples of tumor tissue and adjacent normal mucosa for comparison. Penetration of rEgA-675 into tumor tissue and normal mucosa was investigated, followed by pathologic analysis (Table S4). The signal intensity from the malignancy was around 10-fold higher than those from benign lesion and normal mucosa (Fig. 8 and Fig. S7). This result is well coincident with that of the mouse model, demonstrating the potential of the fluorescent rEgA as a molecular endoscopic contrast agent for in situ evaluation of EGFR expression.

Figure 8.

rEgA ex vivo stain of human cancer tissue. Uptake of fluorescent rEgA is demonstrated in specimens obtained from patients with adenocarcinoma, and dysplastic and benign polyps of the colon or rectum. Endoscopic biopsies were taken simultaneously from both the tumor and adjacent normal mucosa for comparison purposes. EGFR expression in the indicated specimens was examined by Western blot analysis using EGFR antibody and included. Histologic results were correlated with maximum optical radiance signals (* P < 0.01). The experiment was performed on samples from 15 patients, with a normal mucosa and pathologic sample analyzed for each patient (Fig. S7). Imaging and Western blot results from ten representative samples were demonstrated. (N: Normal mucosa or colitis, B: Benign polyp, C: Dysplasia or Adenocarcinoma)

Discussion

A distinct feature of the present approach lies in the use of a small-sized high-affinity repebody for targeting of EGFR in in vivo imaging of tumors. We demonstrated that the approach is suitable for the quantification of target molecule concentrations with PET imaging, which can act as a surrogate for the target burden in cancer tissue. With a repebody specific for a different target, the present strategy can be broadly applied to the detection of other cancer cell surface-markers by molecular imaging. In this study, we also explored the utility and potential of a repebody-based approach for molecular fluorescence endoscopy imaging of EGFR by showing a close correlation between the imaging results and ex vivo histological grading of chemically induced mouse colon cancers and patient-derived colon cancers.

The sensitivity and specificity of imaging agents are dependent on the binding affinity between the molecular probe and the desired target and the specific nature of the molecular recognition. Although antibodies are of primary choice as affinity probes, fewer than half of the approximately 6,000 routinely used commercial antibodies are specific for only their intended target 38. The lack of specificity has been particularly considered significant limitations in medical applications, such as imaging agents and therapeutics. The emergence of protein and peptide engineering techniques, such as synthetic libraries and selection and evolution technologies, has facilitated substantial progress towards a new generation of affinity probes based on alternative protein scaffolds. We previously developed a repebody scaffold, which is a small-sized non-antibody scaffold composed of leucine-rich repeat (LRR) modules 30. The repebody scaffold was shown to be highly stable over a wide range of pH and temperature values, and easy to engineer. A repebody library was constructed for a phage display 30, followed by selection of repebodies specific for the human soluble EGFR ectodomain (hsEGFR). Among them, a repebody (rA11) with an apparent binding affinity of 92 nM for hsEGFR was chosen, and its binding affinity was increased through a modular evolution approach 31, 33. The repebody (rEgA) used in the present study was shown to have a nanomolar affinity (KD = 9.18 nM) and high specificity for hsEGFR, but display weak cross-reactivity against other EGFR family members.

Our cellular and in vivo imaging results indicate that the repebody is a promising molecular binder for the development of imaging agents to evaluate the presence and quantity of therapeutic targets in tumor tissue. The intensity of the imaging signal was closely correlated with the expression of EGFR in cancer cells. Moreover, in animal models, uptake of the radiolabeled repebody showed a good correspondence with the therapeutic efficacy of cetuximab. These results open up the potential applications for a repebody in molecular imaging-based companion diagnostics. The companion diagnostics for highly targeted drugs have so far been based almost entirely on in vitro assays of biopsy material. Companion diagnostics based on molecular imaging thus offer a number of features complementary to those of in vitro assays, including the ability to measure the heterogeneity of each patient's cancer across the entire disease burden, and to measure early changes in response to treatment 39. Although large numbers of patients with EGFR-positive tumors fail to respond to current EGFR-targeted therapies, which may be due to a range of mutations (e.g., EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, PI3K, and PTEN) 17, the strategy of repebody-based companion diagnostics is still valid, because several EGFR-targeted ADCs are under active development 28, 29. Furthermore, EGFR imaging can be used not only for the detection of treatment resistance, but also for the detection of the treatment response of drugs that do not primarily target EGFR (e.g., HSP90 inhibition) 40.

The combination of a target-specific repebody and visualization using confocal microendoscopy offers a new optical imaging method for in vivo early detection of cancer, as well as for target evaluation. Both in vivo and ex vivo imaging of mouse colon cancers using a cooled CCD camera showed significant fluorescence signals resulting from the repebody binding to dysplastic polyps, leading to a 2.1-10.3-fold increase in intensity compared to those from normal mucosa or benign lesions. The repebody used in this study revealed moderate binding for mEGFR (half the affinity for hEGFR, Fig. 2B), which indicates that the repebody is eligible for imaging of mouse colon cancers. Ex vivo imaging of patient-derived colon cancer tissue with fluorescent repebody also showed high contrast between malignant and benign or normal tissue, revealing correspondence with the immunohistochemical staining of EGFR. A recent immunohistochemical study that included 386 colorectal cancer patients reported a significant correlation between EGFR expression at the invasive margin and a poor prognosis 41. Our results thus strongly imply another potential application of the repebody, which is in the endoscopic evaluation of EGFR expression, where the repebody may have a role in risk evaluation for colon cancer patients.

In conclusion, after injection the repebody can be used as an imaging agent to provide high-contrast PET imaging and molecular endoscopic imaging of EGFR expression in cancer. Our results demonstrate that the repebody has a potential as a novel scaffold for the development of imaging agents for precision cancer treatment. In the near future, multifunctional scaffolds (i.e., multiple independent binding sites for the same or different targets) could be used to greatly enhance the selectivity of a repebody through avidity. The versatility of a repebody will address a number of alternative scaffold designs for therapeutics, diagnostics, and theranostics.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Pioneer Research Center Program (2015M3C1A3056410), Bio & Medical Technology Development Program (NRF-2014M3A9B5073747) of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning. J.-J.M. was supported by the grant of CNUH-GIST (CRI15072-3), H.-S.K. was supported by the Global Research Laboratory Program (NRF-2015K1A1A2033346), Mid-career Researcher Program (NRF-2014R1A2A1A01004198) of the National Research Foundation (NRF), and Brain Korea 21 funded by the Ministry of Education, J.Y.K. was supported by the Radiation Technology R&D program (NRF-2012M2A2A7013480) and D.Y.K. was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2015M2B2A9031798) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (D.-Y. K.). W.S.L was supported by the grant (HCRI14025-1) from the Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital Institute for Biomedical Science.

Abbreviations

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- shEGFR

soluble human EGFR

- mEGFR

mouse EGFR

- LRR

leucine-rich repeat

- PET

positron emission tomography

- ADCs

antibody-drug conjugates

- MMAF

monomethyl auristatin F

- AOM

azoxymethane

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium

- p-SCN-Bn-NOTA

2-(p-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N,N',N,"-triacetic acid trihydrochloride.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S7 and Supplementary Tables S1-S4.

References

- 1.Collins FS, Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:793–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freise AC, Wu AM. In vivo imaging with antibodies and engineered fragments. Mol Immunol. 2015;67:142–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tolmachev V, Stone-Elander S, Orlova A. Radiolabelled receptor-tyrosine-kinase targeting drugs for patient stratification and monitoring of therapy response: prospects and pitfalls. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:992–1000. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chames P, Van Regenmortel M, Weiss E, Baty D. Therapeutic antibodies: successes, limitations and hopes for the future. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:220–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garousi J, Lindbo S, Nilvebrant J, Astrand M, Buijs J, Sandstrom M. et al. ADAPT, a novel scaffold protein-based probe for radionuclide imaging of molecular targets that are expressed in disseminated cancers. Cancer Res. 2015;75:4364–71. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aerts HJ, Dubois L, Perk L, Vermaelen P, Dongen GA, Wouters BG. et al. Disparity between in vivo EGFR expression and 89Zr-labeled cetuximab uptake assessed with PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:123–31. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.054312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li WP, Meyer LA, Capretto DA, Sherman CD, Anderson CJ. Receptor-binding, biodistribution, and metabolism studies of 64Cu-DOTA-cetuximab, a PET-imaging agent for epidermal growth-factor receptor-positive tumors. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2008;23:158–71. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2007.0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenthal EL, Kulbersh BD, King T, Chaudhuri TR, Zinn KR. Use of fluorescent labeled anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody to image head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:1230–8. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalofonos HP, Pawlikowska TR, Hemingway A, Courtenay-Luck N, Dhokia B, Snook D. et al. Antibody guided diagnosis and therapy of brain gliomas using radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies against epidermal growth factor receptor and placental alkaline phosphatase. J Nucl Med. 1989;30:1636–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stillebroer AB, Franssen GM, Mulders PF, Oyen WJ, Dongen GA, Laverman P. et al. Immuno PET imaging of renal cell carcinoma with 124I- and 89Zr-labeled anti-CAIX monoclonal antibody cG250 in mice. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013;28:510–5. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2013.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duan D, Li SL, Zhu YQ, Zhang T, Lei CM, Cheng XH. Radioimmunoimaging with mixed monoclonal antibodies of nude mice bearing human lung adenocarcinoma xenografts. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:4255–61. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.9.4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong H, Kovar J, Little G, Chen H, Olive DM. In vivo imaging of xenograft tumors using an epidermal growth factor receptor-specific affibody molecule labeled with a near-infrared fluorophore. Neoplasia. 2010;12:139–49. doi: 10.1593/neo.91446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hackel BJ, Kimura RH, Gambhir SS. Use of 64Cu-labeled fibronectin domain with EGFR overexpressing tumor xenograft: molecular imaging. Radiology. 2012;263:179–88. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gainkam LOT, Huang L, Caveliers V, Keyaerts M, Hernot S, Vaneycken I. et al. Comparison of the biodistribution and tumor targeting of two 99mTc-labeled anti-EGFR nanobodies in mice, using pinhole SPECT/Micro-CT. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:788–95. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong MH, Kim K, Kim EM, Cheong SJ, Lee CM, Jeong HJ. et al. In vivo and in vitro evaluation of Cy5.5 conjugated epidermal growth factor receptor binding peptide. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:805–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. Drug therapy: EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1160–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chong CR, Janne PA. The quest to overcome resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies in cancer. Nat Med. 2013;19:1389–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinojima N, Tada K, Shiraishi S, Kamiryo T, Kochi M, Nakamura H. et al. Prognostic value of epidermal growth factor receptor in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6962–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nieto Y, Nawaz F, Jones RB, Shpall EJ, Nawaz S. Prognostic significance of overexpression and phosphorylation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the presence of truncated EGFRvIII in locoregionally advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4405–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zlobec I, Vuong T, Hayashi S, Haegert D, Tornillo L, Terracciano L. et al. A simple and reproducible scoring system for EGFR in colorectal cancer: application to prognosis and prediction of response to preoperative brachytherapy. Brit J Cancer. 2007;96:793–800. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parra HS, Cavina R, Latteri F, Zucali PA, Campagnoli E, Morenghi E. et al. Analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor expression as a predictive factor for response to gefitinib ('Iressa', ZD1839) in non-small-cell lung cancer. Brit J Cancer. 2004;91:208–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schlomm T, Kirstein P, Lwers L, Daniel B, Steuber T, Walz J. et al. Clinical significance of epidermal growth factor receptor protein overexpression and gene copy number gains in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6579–84. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholson RI, Gee JMW, Harper ME. EGFR and cancer prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:S9–S15. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azizi E, Kittai A, Kozuch P. Antiepidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies: applications in colorectal cancer. Chemother Res Pract. 2012;2012:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2012/198197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hara F, Aoe M, Doihara H, Taira N, Shien T, Takahashi H. et al. Antitumor effect of gefitinib ('Iressa') on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett. 2005;226:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukohara T, Engelman JA, Hanna NH, Yeap BY, Kobayashi S, Lindeman N. et al. Differential effects of gefitinib and cetuximab on non-small-cell lung cancers bearing epidermal growth factor receptor mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1185–94. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, Azarnia N, Shin DM, Cohen RB. et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamouscell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:568–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillips AC, Boghaert ER, Vaidya KS, Mitten MJ, Norvell S, Falls HD. et al. ABT-414, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting a tumor-selective EGFR epitope. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:661–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang L, Veneziale B, Frigerio M, Badescu G, Li X, Zhao Q. et al. Preclinical evaluation of a next-generation, EGFR targeting ADC that promotes regression in KRAS or BRAF mutant tumors. AACR 107th Annual Meeting 2016. 2016;57:310–1. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SC, Park K, Han J, Lee JJ, Kim HJ, Hong S. et al. Design of a binding scaffold based on variable lymphocyte receptors of jawless vertebrates by module engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:3299–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113193109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JJ, Choi HJ, Yun M, Kang Y, Jung JE, Ryu Y. et al. Enzymatic prenylation and oxime ligation for the synthesis of stable and homogeneous protein-drug conjugates for targeted therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:11020–4. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hwang DE, Ryou JH, Oh JR, Han JW, Park TK, Kim HS. Anti-human VEGF repebody effectively suppresses choroidal neovascularization and vascular leakage. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152522. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JJ, Kim HJ, Yang CS, Kyeong HH, Choi JM, Hwang DE. et al. A high-affinity protein binder that blocks the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway effectively suppresses non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Ther. 2014;22:1254–65. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blasi F, Oliveira BL, Rietz TA, Rotile NJ, Day H, Looby RJ. et al. Effect of chelate type and radioisotope on the imaging efficacy of 4 fibrin-specific PET probes. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1157–63. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.136275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sah BR, Schibli R, Waibel R, Boehmer LV, Bläuenstein P, Nexo E. et al. Tumor imaging in patients with advanced tumors using a new 99mTc-radiolabeled vitamin B12 derivative. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:43–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.113.122499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmermann K, Grünberg J, Honer M, Ametamey S, Schubiger PA, Novak-Hofer I. Targeting of renal carcinoma with 67/64Cu-labeled anti-L1-CAM antibody chCE7: selection of copper ligands and PET imaging. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:417–4427. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(03)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee JJ, Kang JA, Ryu Y, Han SS, Nam YR, Rho JK. et al. Genetically engineered and self-assembled oncolytic protein nanoparticles for targeted cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2017;120:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bradbury A, Plückthun A. Reproducibility: Standardize antibodies used in research. Nature. 2015;518:27–9. doi: 10.1038/518027a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mankoff DA, Edmonds CE, Farwell MD, Pryma DA. Development of companion diagnostics. Semin Nucl Med. 2016;46:47–56. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiegelberg D, Mortensen A, Selvaraju R, Eriksson O, Stenerlöw B, Nestor M. Molecular imaging of EGFR and CD44v6 for prediction and response monitoring of HSP90 inhibition in an in vivo squamous cell carcinoma model. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:974–82. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3260-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ljuslinder I, Melin B, Henriksson ML, Oberg A, Palmqvist R. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor expression at the invasive margin is a negative prognostic factor in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2031–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S7 and Supplementary Tables S1-S4.