Abstract

A major challenge in photodynamic therapy (PDT) is the development of new tumor-targeting photosensitizers. The tumor-specific activation is considered to be an effective strategy for designing these photosensitizers. Herein, we describe a novel tumor-pH-responsive supramolecular photosensitizer, LDH-ZnPcS8, which is not photoactive under neutral conditions but is precisely and efficiently activated in a slightly acidic environment (pH 6.5). LDH-ZnPcS8 is prepared by using a simple coprecipitation method based on the electrostatic interaction between negatively charged octasulfonate-modified zinc(II) phthalocyanine (ZnPcS8) and cationic hydroxide layers of layered double hydroxide (LDH). The in vitro photodynamic activities of LDH-ZnPcS8 in cancer cells are dramatically enhanced relative to those of ZnPcS8 alone. The results of in vivo fluorescence imaging demonstrate that the nanohybrid is activated in tumor tissues, where it displays an excellent PDT effect resulting in 95.3% tumor growth inhibition. Furthermore, the minimal skin phototoxicity of LDH-ZnPcS8 highlights its high potential as a novel photosensitizer for activatable PDT.

Keywords: photodynamic therapy, activatable photosensitizer, skin phototoxicity, layered double hydroxide, phthalocyanine.

Introduction

Photodynamic therapy (PDT), a clinically promising therapeutic modality for various neoplasms, has attracted widespread attention in the past few decades owing to several unique features including minimal invasiveness and lack of initiating resistance 1-4. PDT utilizes the combined action of photosensitizers, light, and molecular oxygen to produce reactive oxygen species that destroy cells and tissues 5-10. By focusing light on specific regions of a tumor, damage caused by PDT can be confined to selectively targeted tissues 11-16. However, a drawback of the typical PDT approach is that patients must remain in the dark for long periods of time after treatment so that the photosensitizer can be excreted from the body. Otherwise, damage to normal tissues as well as cutaneous photosensitivity can occur 17. Also, after intravenous injection of photosensitizers, the eyes of patients are sensitive to indoor bright light or sunlight and their skin is readily sunburned, swollen, and blistered when exposed to bright light for short periods 18-22.

Recently, a new PDT technique was developed that utilizes activatable photosensitizers (aPSs), substances that are selectively activated by tumor-associated stimuli 23-29. Importantly, in the absence of tumor-associated stimuli, aPSs exist in a passive state even upon exposure to light 30-37. Because tumor microenvironments are more acidic (pH ca. 6.5-6.8) than those in blood and normal tissues (pH ca. 7.4) 38, response to acidic pH is a commonly used stimulus for activating aPSs 39-47. However, most of the aPSs of this type developed to date respond to conditions that have pH values ≤ 6.0 39-44, that do not fall in the general pH region found in tumor microenvironments. To the best of our knowledge, only three known aPSs have true tumor-pH-responsive characteristics 45-47. These include the phthalocyanine dimer 45, polysaccharide/Ce6 conjugate 46, and cyclometalated iridium(III) complexes 47. However, these aPSs do not possess a high enough activation efficiency that includes both quenching of singlet oxygen in a deactivated state and reactivation-properties that are required for low side effects and high therapeutic efficacy of PDT. These aPSs also require tedious preparation procedures for introducing stimuli-responsive linkers or groups. Therefore, there is a need for efficient tumor-pH-responsive photosensitizers that can be easily synthesized.

Layered double hydroxides (LDHs), also called anionic nanoclays, are a prominent class of layered inorganic materials with a chemical description of [M2+1-xM3+x(OH)2](An-)x/n·mH2O, in which M2+, M3+, An- represent the divalent metal cation, trivalent metal cation, and charge-balancing interlayer anion, respectively 48. Recently, LDHs have gained considerable attention as drug/gene carriers owing to a host of desirable properties, such as simple preparation, good biocompatibility and biodegradability, and protection of the loaded drug/gene 49-52. Additional unique assets of LDHs not present in other nanocarriers are their anion exchange properties and acid sensitivity. These properties enable LDHs to load unmodified anionic drugs/biomolecules and then to release the active molecules in a pH-controlled fashion in acidic environments 53, 54.

In a previous investigation, we reported the high photosensitizing efficiency of zinc (II) phthalocyanine containing octasulfonate ZnPcS8 (Scheme 1) with a singlet oxygen quantum yield of 0.62 in water solution 55. Because of strong hydrophobic interactions, phthalocyanines generally aggregate in an aqueous solution 56. However, the highly hydrophilic and electrostatic repulsive interactions caused by the negatively charged sulfonate groups cause ZnPcS8 to remain in a non-aggregated form even in non-surfactant containing water. Furthermore, even though ZnPcS8 is rapidly excreted from the body, difficult procedures must be followed to avoid light exposure after PDT treatment using this phthalocyanine derivative. To overcome this limitation, we have employed a modular and versatile strategy that takes advantage of a host-guest supramolecular interaction between LDH and ZnPcS8 to design the new photoactivity-activatable photosensitizer LDH-ZnPcS8.

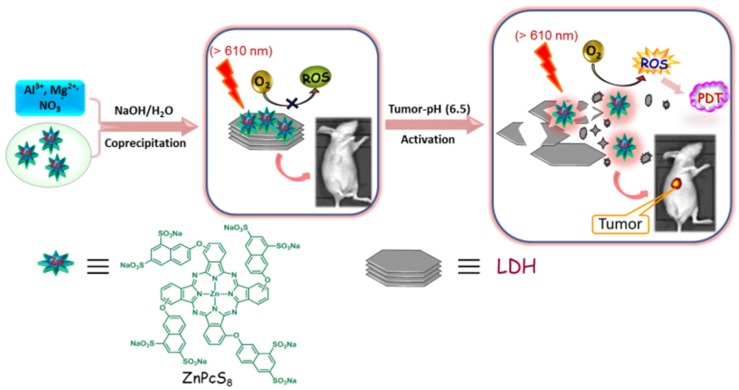

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the construction of LDH-ZnPcS8 nanohybrid by a co-precipiatation method: Mg, Al, and Zn in the nanohybrid were 20.87, 7.13 and 0.27 wt%, respectively. The loading percentage of ZnPcS8 in LDH-ZnPcS8 was 7.35 wt%. The probable mechanism as an aPS for PDT through the low acidity-driven release of ZnPcS8 from LDH-ZnPcS8, leading to reactivation of its photoactivities is illustrated.

In our initial considerations, we envisaged that the strong electrostatic-driven affinity between ZnPcS8 and the positively charged brucite layer of LDH would promote the formation of the aggregate LDH-ZnPcS8. Furthermore, the presence of ZnPcS8 on the large planar surface of LDH in LDH-ZnPcS8 would enable photo-induced electron transfer (PET) leading to efficient quenching of the photoexcited state of ZnPcS8 (Scheme 1). In addition, the strong electrostatic interactions in LDH-ZnPcS8 would be lost in a slightly acidic environment leading to the collapse of the aggregate structure. This phenomenon would cause the release of ZnPcS8 and restoration of its high photoactivity. In studies aimed at evaluating these proposals, we discovered that LDH-ZnPcS8 has excellent tumor-pH-responsive properties, including a high quenching effect of over 80% at pH 7.4 and reactivating effect of up to 90% at pH 6.5. To our knowledge, LDH-ZnPcS8 possesses the highest activatable efficiency described so far. More importantly, our results show that LDH-ZnPcS8 has low in vivo skin phototoxicity.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and characterization of LDH-ZnPcS8

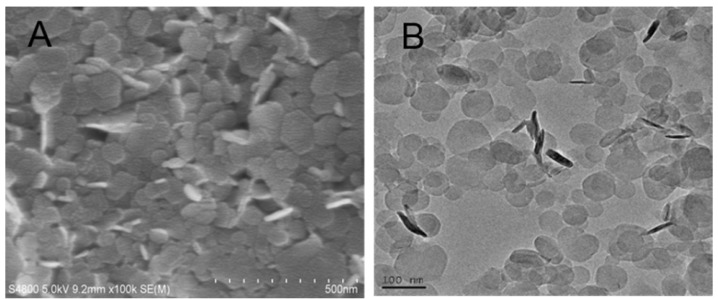

As depicted schematically in Scheme 1, LDH-ZnPcS8 was prepared by utilizing a co-precipitation method. Briefly, highly water-soluble ZnPcS8 was treated with a solution of Mg (NO3)2 and Al (NO3)3 under alkaline conditions to yield the LDH-ZnPcS8 nanohybrid. The chemical composition of LDH-ZnPcS8, determined by using ICP-OES, showed that the amounts of Mg, Al, and Zn in the nanohybrid were 20.87, 7.13, and 0.27 wt%, respectively. Accordingly, the loading percentage of ZnPcS8 in LDH-ZnPcS8 was 7.35 wt%. Inspection of SEM and TEM images indicated that LDH-ZnPcS8 has a hexagonal lamellar morphology with a main lateral diameter of 60-100 nm (Figure 1). Also, the results of DLS measurements demonstrated that LDH-ZnPcS8 in water had a relatively uniform size distribution with a mean hydrodynamic diameter of about 145 nm (Figure S1A).

Figure 1.

(A) SEM image and (B) TEM image of LDH-ZnPcS8.

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to probe the structure of LDH-ZnPcS8 (Figure S1B). In contrast to LDH-NO3, which contained an interlayer anion of NO3-, the FTIR spectrum of LDH-ZnPcS8 had characteristic bands associated with the ZnPcS8 component. Peaks at 1627, 1586, 1501 and 1485 cm-1 were ascribed to C=N and C=C stretching vibrations of the phthalocyanine core, and sulfonic group S=O stretching bands were present at 1054 and 1039 cm-1. LDH-ZnPcS8 had an XRD pattern that was identical to that of LDH-NO3 (Figure S1C), with a basal spacing of 0.79 nm and a gallery height of 0.31 nm.

The results of PM3 calculations (Figure S2) showed that the three-dimensional size of ZnPcS8 was 2.00 × 2.00 × 0.85 nm3 and that the thickness of ZnPcS8 was larger than the gallery height of LDH-ZnPcS8. This finding prompted us to speculate that ZnPcS8 was not inserted into the interlayer of LDH but rather firmly absorbed on the layer surface as a consequence of strong electrostatic interactions between ZnPcS8 and the brucite layer. Moreover, the fact that the zeta potential of LDH-ZnPcS8 (+36.9 mV) was smaller than that of LDH-NO3 (+41.2 mV) suggested that the layer charges of LDH in the nanohybrid were neutralized by ZnPcS8.

Highly quenched photoactivities of LDH-ZnPcS8

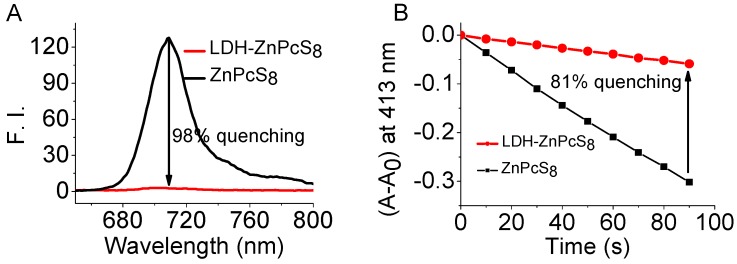

The efficiencies for quenching of the photoactivities of LDH-ZnPcS8 water solution were examined. Inspection of the absorption spectrum of ZnPcS8 (Figure S3) showed that it existed nearly exclusively as a monomer in water. The spectrum of ZnPcS8 contained a sharp and intense Q-band at 696 nm. In contrast, the Q-band of LDH-ZnPcS8 (λ = 699 nm) was broader and less intense which reflected aggregation of the phthalocyanine groups. Fluorescence emission from LDH-ZnPcS8 was more than 45-fold less intense compared to that of ZnPcS8 (Figure 2A). This observation clearly showed that the fluorescence of ZnPcS8 was essentially quenched (> 98%) in the matrix of LDH-ZnPcS8. The efficiency of LDH-ZnPcS8 quenching of singlet oxygen generation was evaluated by using DPBF as a probe (Figure S4 and Figure 2B). The results showed that ZnPcS8 promoted efficient photodegradation of DPBF. In contrast, singlet oxygen generation promoted by LDH-ZnPcS8 was highly inefficient under the same conditions used for ZnPcS8. The singlet oxygen quenching efficiency was determined to be 81%, which was much higher than the effect of self-quenching in zinc phthalocyanine dimers (60%-66%) 45. It is worth mentioning that this singlet oxygen quenching was correlated well with fluorescence quenching. Similar results were also reported by Lovell et al. 57. Another study showed that ZnPcS8 in the nanohybrid was effectively protected from photodegradation. As shown in Figure S5, while ZnPcS8 was nearly completely degraded by light irradiation for 50 min, there was almost no degradation of LDH-ZnPcS8 under the same conditions.

Figure 2.

Photophysical and photochemical properties of LDH-ZnPcS8: (A) fluorescence spectra of ZnPcS8 and LDH-ZnPcS8 in water at 1.5 μM. (B) Photodegradation rates of DPBF (60 μM) in water (containing 0.12% DMF and 0.06% Cremophor EL) induced by ZnPcS8 and LDH-ZnPcS8 (both at 3.5 μM). A0 is the initial absorbance of the phthalocyanine probe.

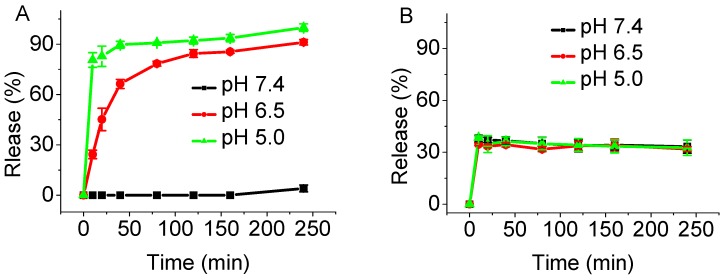

pH-controlled release of LDH-ZnPcS8

We anticipated that tumor-promoted release of ZnPcS8 from photoinactive LDH-ZnPcS8 would lead to an active PDT agent. To demonstrate the pH-responsive release of ZnPcS8, LDH-ZnPcS8 was incubated in phosphate buffer solutions at pH values of 5.0, 6.5, and 7.4 which simulated the physiological media present in lyso/endosomes, tumor tissues, and blood, respectively 58. As the plots in Figure 3A show, the release of ZnPcS8 was both pH- and time-dependent. ZnPcS8 was very slowly released in the pH 7.4 solution. Under slightly acidic conditions, ZnPcS8 was released rapidly; especially at pH 5.0, more than 80% release took place within 10 min and was nearly complete after 4 h. About 90% of ZnPcS8 was released within 4 h in the acidic (pH ca. 6.5) tumor environment. These results strongly suggest that the nanohybrid specifically and efficiently generates photoactive ZnPcS8 in a tumor-pH medium.

Figure 3.

Comparison of the release profiles: (A) ZnPcS8 from LDH-ZnPcS8 and (B) S2 from LDH-S2 in PBS solutions with pH 7.4, 6.5, and 5.0 at different time intervals.

To understand the effect of the negative charges present in ZnPcS8 on the pH-sensitivity of the nanohybrid, the analog LDH-S2 containing two sulfonate groups on a phthalonitrile moiety (S2) 55 was prepared (Figure S6). The plot displayed in Figure 3B shows that release of S2 from LDH-S2 occurred quickly and reached a plateau at ca. 40% under different pH conditions. This observation suggested that S2 release from the nanohybrid was not pH-dependent. Also, the stability under neutral condition and efficiency of release of LDH-ZnPcS8 at tumor-pH were much higher than another nanohybrid in which a tetrasulfonated phthalocyanine was aggregated with LDH. The release efficiency of the latter hybrid reached ca. 12% at pH 7.4 and only 58% at pH 6.5 54. These results demonstrated that pH-control of release in these nanohybrids directly related to the number of negatively charged sulfonate moieties.

To gain additional information about the release process, LDH-ZnPcS8 was suspended in phosphate buffer solutions at different pHs for 4 h. The precipitates and filtrates were isolated by centrifugation. As shown in Figure S7A, the precipitates resulting from pH 6.5 and 5.0 solutions were essentially colorless and obviously less than that coming from the pH 7.4 solution. In contrast, the filtrates derived from the pH 6.5 and 5.0 solutions had the color associated with absorption of light by ZnPcS8, while nearly no light absorption was observed for the supernatant coming from the pH 7.4 solution (Figure S7B).

We speculated that ZnPcS8 release from LDH-ZnPcS8 under acidic conditions was a consequence of both collapse of the nanohybrid structure and ion exchange. The presence of more sulfonate groups should lead to stronger electrostatic interactions between LDH and ZnPcS8, which was not conducive to efficient ion-exchange. However, the stronger electrostatic interactions might affect the structural integrity of LDH and make it more susceptible to collapse in an acidic environment.

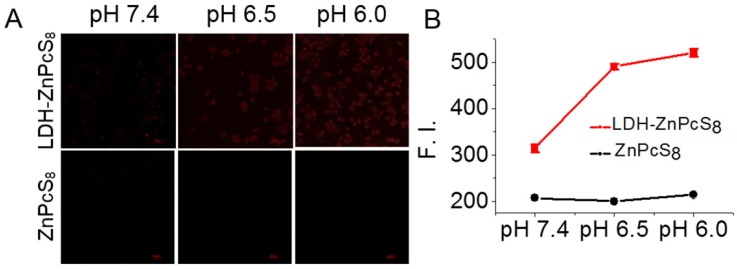

In vitro fluorescence imaging and photodynamic activities

The pH-responsive photoactivity of LDH-ZnPcS8 at the cellular level was examined. HepG2 cells in pH 7.4, 6.5 and 6.0 solutions were incubated independently with LDH-ZnPcS8. ZnPcS8 was followed by treatment with nigericin, which promotes equilibration of intracellular and extracellular pH 59, 60. Fluorescence images of the cells were then recorded using a confocal microscope and the intracellular fluorescence intensities were determined. As shown in Figure 4, the intracellular intensities of cells treated with LDH-ZnPcS8 were much higher than those incubated with ZnPcS8. Also, cells incubated with LDH-ZnPcS8 at pH 6.0 and 6.5 exhibited stronger fluorescence emission than that at pH 7.4. Given the fact that the environments of typical tumors and normal tissues fall into the respective pH ca. 6.5 and 7.4 regions, the results demonstrated that LDH-ZnPcS8 might be a potentially useful aPS for cancer therapy. We noticed that fluorescence emission from cells treated with LDH-ZnPcS8 at pH 7.4 was stronger than anticipated. This phenomenon might be due to effective neutralization of the negative charges of ZnPcS8 by the cationic brucite layer making its uptake difficult by cancer cells that contain a negatively charged cell membrane. Another reason might be that ZnPcS8 was released from the nanohybrid after endocytosis into the inherently acidic endosomes or lysosomes as a result of non-complete pH regulation in the cells by nigericin.

Figure 4.

pH-responsive fluorescence emission of LDH-ZnPcS8 at the cellular level: (A) Confocal fluorescence images of HepG2 cells after incubation with LDH-ZnPcS8 and ZnPcS8 at 0.1 μM for 30 min, followed with 25 μM nigericin solutions at pH 7.4, 6.5 and 6.0 for 20 min. Scale bars= 50 μm. (B) Comparison of the relative intracellular fluorescence intensities. Data are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation (number of cells = 50).

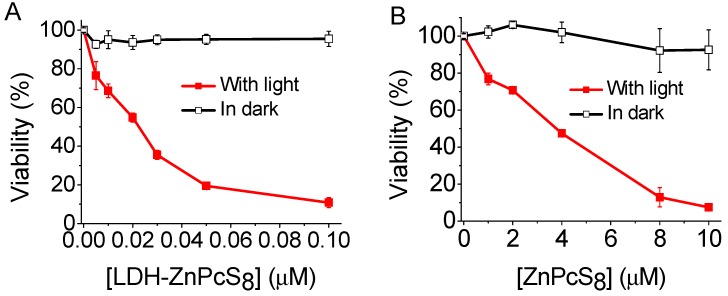

As a logical next step, we investigated the photodynamic activities of LDH-ZnPcS8 and ZnPcS8 in the HepG2 cell line. As the plots given in Figure 5 demonstrate, both LDH-ZnPcS8 and ZnPcS8 were quite non-cytotoxic for HepG2 cells in the dark. However, under red light illumination, the cell killing effects caused by LDH-ZnPcS8 and ZnPcS8 differed greatly. The IC50 value of LDH-ZnPcS8 for HepG2 cell death was more than 170-fold lower than that of ZnPcS8 (IC50 = 0.022 μM for LDH-ZnPcS8 and 3.78 μM for ZnPcS8). The different activities might be the result of the better cellular uptake and acid-reactivation feature of LDH-ZnPcS8, which were verified by the results of their cellular uptake detected by two different methods (Figure S8) and subcellular localization (Figure S9) without using nigericin.

Figure 5.

Cytotoxic effects HepG2 cells: (A) LDH-ZnPcS8 and (B) ZnPcS8 in the presence and absence of light (λ > 610 nm) at a dose of 27 J•cm-2. Data are expressed as mean values ± standard deviation of three separate experiments.

In vivo fluorescence imaging and photodynamic activities

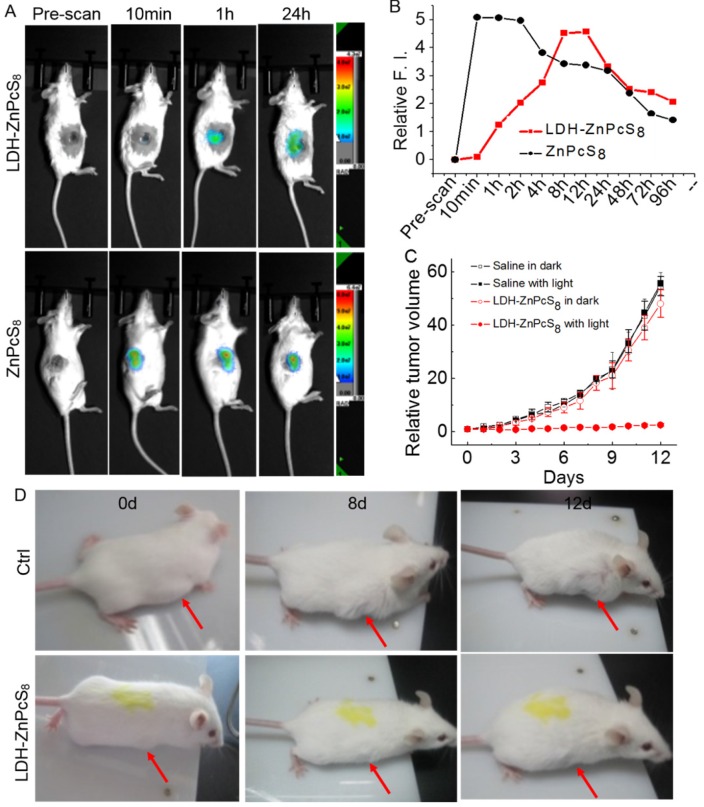

Encouraged by the activatable capability of LDH-ZnPcS8 in vitro, we studied its potential use as an in vivo aPS. In a proof-of-concept study, in vivo fluorescence imaging was first carried out following intratumoral injection 33, 52 of LDH-ZnPcS8 into mice bearing an H22 tumor. As shown in Figures 6A and B, the tumor site displayed no emission signal before injection. One hour after injection a weak fluorescence signal was observed at the tumor site which slowly grew in intensity during a 12-h period. The fluorescence intensity of ZnPcS8-injected tumors in mice, used as controls, was very strong within a few hours after injection. After one day, emission from tumors injected with both substances was significantly decreased in a similar fashion. The results indicated that LDH-ZnPcS8, which was almost nonfluorescent and nonphototoxic in its native state, was activated slowly but efficiently in tumors.

Figure 6.

In vivo activation of LDH-ZnPcS8: (A) In vivo fluorescence imaging of mice and (B) relative fluorescence intensities after intratumoral injection with LDH-ZnPcS8 and ZnPcS8 at different time points. (C) The tumor growth curves of the four groups of mice after treatment (Drug dose: ~0.9 μmol•Kg-1. Light condition: wavelength, 685 ± 4 nm; power density, 140 mW•cm-2 ; irradiation, 30 min. Drug light interval: 5 h.). The error bar is based on standard deviation of mice per group. (D) Representative photos of mice bearing tumors after treatment. (top: saline with light. bottom: LDH-ZnPcS8 with light.) The arrows indicate tumor sites.

The therapeutic efficacy of LDH-ZnPcS8-induced PDT treatment was further evaluated. Two groups of tumor-bearing mice (8 mice per group) each were injected with LDH-ZnPcS8 or saline used as a control. Half of the mice from each group were subjected to irradiation while the other half did not receive irradiation. The results (Figure 6C and 6B) showed that tumor growth was almost completely inhibited (95.3% tumor growth inhibition after 12 d) in mice treated with LDH-ZnPcS8 and then irradiated. In contrast, mice treated with LDH-ZnPcS8 and not irradiated showed a significant level of tumor growth which was comparable to growth in mice treated with saline with or without irradiation.

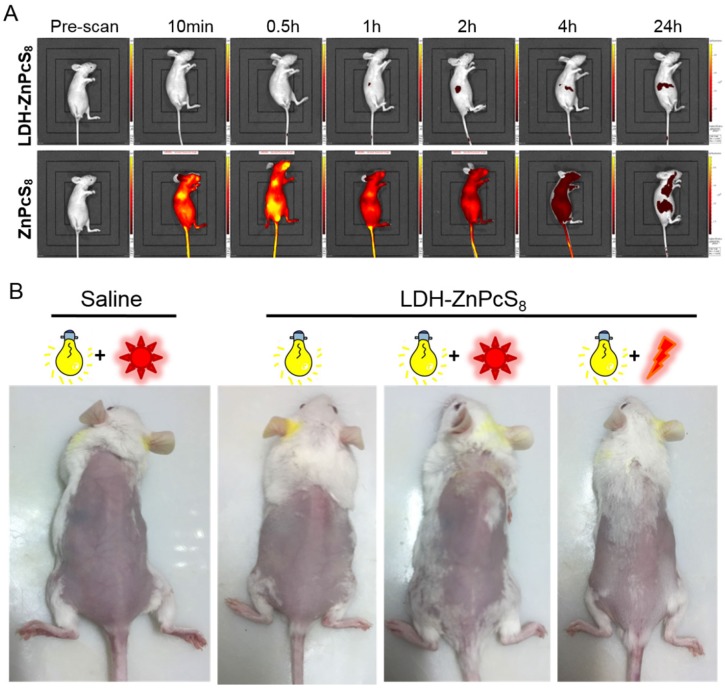

In vivo skin phototoxicity

To further highlight the advantages of LDH-ZnPcS8 as an aPS for PDT, we determined its potential skin phototoxicity after intravenous injection by using in vivo fluorescence imaging. As is evident from Figure 2, fluorescence quenching correlated well with singlet oxygen quenching. Therefore, higher fluorescence emission from treated skin indicated a higher photosensitizing ability of the substance applied. As shown in Figure 7A, compared to the strong signal arising from the skin of the mice treated with ZnPcS8, there was almost no signal in mice injected with LDH-ZnPcS8. Furthermore, the data showed that in vivo clearance of ZnPcS8 was much faster than that of traditional lipophilic photosensitizers, which are limited by their strong tissue retention propensity 18-20, 55, 61. Thus, these observations clearly showed that aggregation of ZnPcS8 with LDH shortened the duration of its photosensitivity and reduced its skin phototoxicity. There was almost no change in the weight of LDH-ZnPcS8-treated mice with light irradiation (Figure S10). Also, similar to the saline-treated controls (Figure 7B), no erythema, edema or other indications of skin photosensitivity were observed on the back skin of mice treated with LDH-ZnPcS8 and exposed to either room light, sunlight (20 min), or even laser irradiation (252 J•cm-2).

Figure 7.

Detection of potential skin phototoxicity: (A) In vivo fluorescence imaging of mice before and after intravenous injection with LDH-ZnPcS8 and ZnPcS8 at different time points. (B) Representative photos of mice after treatments with saline or LDH-ZnPcS8 with room light, sunlight, and/ or laser irradiation

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a novel tumor pH-activatable supramolecular photosensitizer, which could be prepared easily by using a co-precipitation method. The design of the new activatable photosensitizer took advantage of electrostatic interactions between octasulfonate-modified zinc (II) phthalocyanine (ZnPcS8) and layered double hydroxide (LDH). The LDH-ZnPcS8 nanohybrid exhibited a hexagonal lamellar morphology with a generally lateral diameter of ca. 100 nm. Because of its incorporation in a nanohybrid with LDH, both fluorescence emission and generation of singlet oxygen promoted by ZnPcS8 were efficiently quenched (> 80%). However, the photoactivities of ZnPcS8 were reactivated up to 90% by incubation in an aqueous solution at pH 6.5. In contrast to ZnPcS8, the in vitro photodynamic activities of LDH-ZnPcS8 in HepG2 cells were greatly enhanced as reflected by a 170-fold decrease in the IC50 value for induced cell death. The results of in vivo fluorescence imaging demonstrated that deactivated LDH-ZnPcS8 was activated in tumor tissues where it had a 95.3% tumor inhibition effect. More importantly, this tumor-pH activatable photosensitizer exhibited minimal skin phototoxicity. We believe that the conceptual basis for the functional significance of LDH-phthalocyanine supramolecular photosensitizer would be useful for developing new strategies to design other activatable PDTs.

Materials and Methods

Materials and reagents

Mg(NO3)2·6H2O, Al(NO3)2·9H2O, NaOH, KNO3, N,N-dimethyl formamide (DMF), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and saline were purchased from Chinese Medicine Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (China). Cremophor EL and 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) were bought from Sigma (USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and RPMI 1640 medium were obtained from HyClone (USA). 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Genview (USA).

Preparation of LDH-ZnPcS8 and LDH-S2

LDH-ZnPcS8 was prepared by a direct co-precipitation method. A solution of Al(NO3)3 (1.66 mmol) and Mg(NO3)2 (4.97 mmol) in water (12.5 mL) was added dropwise into a stirring water solution of ZnPcS8 (608 μM, 12.5 mL) at 25o C followed by dropwise addition of NaOH in water (430 mM, 37.5 mL). The mixture was stirred in a nitrogen atmosphere at 25 oC for 1.5 h and then centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 10 min. Subsequently, the supernatant was removed and the sediment was dispersed into pure water (40 mL) again. The steps of centrifugation and dispersion were repeated twice. Finally, the suspension was loaded into a Teflon-lined steel pressure vessel and subjected to a hydrothermal treatment at 120 oC for 8 h.

LDH-S2 was prepared using the same method described for LDH-ZnPcS8, by replacing ZnPcS8 with S2 (0.26 mmol).

Characterization

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded at room temperature using the KBr pellet method using an SP2000 spectrometer in the 400-4000 cm-1 with the average of 50 scans. The zeta potential and dynamic light scattering (DLS) were measured by Nanotrac Wave. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were obtained with D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer using Cu Kα (λ = 0.154 nm) radiation. The step size of 0.02° was used in the scan range 5-80° (2θ). The morphology of samples was observed by Hitachi SU8000 field emission SEM or S-4800 field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The chemical composite analysis was performed with Jobin Yvon Ultima2 inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) instrument. Electronic absorption spectra were detected on a SHIMADZU UV-2450 spectrophotometer. Fluorescence spectra were carried out on an Edinburgh FL900/FS900 spectrofluorometer.

Photoactivities in solution

The studies of photostability in water were performed as per our previously described procedure by changing the solvent of DMF to water 55.

The efficiency of singlet oxygen production was checked in aqueous solution. First, 50 mM DPBF in DMF was prepared and formulated with Cremophor EL. Subsequently, the solution was diluted with water to obtain a 120 µM DPBF solution (containing 0.24% DMF and 0.12% Cremophor EL). Next, the 1 mL DPBF solution was mixed with ZnPcS8 or LDH-ZnPcS8 solution (7 µM, 1 mL) to obtain a mixture of ZnPcS8 (or LDH-ZnPcS8) and DPBF (containing [DPBF] = 60 µM, [photosensitizer] = 3.5 µM, 0.12% DMF, and 0.06% Cremophor EL). Finally, the mixture was treated with a red-light irradiation and the DPBF degradation around 413 nm was monitored over the irradiated time. The concentration of LDH-ZnPcS8 in this study was recorded per the amount of ZnPcS8 it contained, which was detected by acid decomposition method as similar to the next calculation method.

pH-controlled release

The release of ZnPcS8 from LDH-ZnPcS8 nanocomposite was carried out in phosphate buffer solutions with pH at 5.07, 6.5, and 7.4. LDH-ZnPcS8 was uniformly dispersed into the phosphate buffer solutions ([ZnPcS8] = 2.0 μM, 150 mL) and the mixture was shaken at 37 ± 0.5o C. At different time intervals, 3 mL of this mixture were taken out and then centrifuged. Next, the supernatants were carefully transferred for UV-vis spectroscopic detection. The release concentrations could then be calculated per the absorbance at about 694 nm by comparing to the calibration curves. The mixture was replenished with 3 mL of the phosphate buffer solutions to keep the total volume constant.

The release of S2 from LDH-S2 was performed using a similar procedure described for LDH-ZnPcS8, while the absorbance at about 306 nm was recorded to give the release percentage.

Cell culture

Human hepatocarcinoma (HepG2) cells and mouse hepatoma (H22) cells were purchased from ATCC. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, streptomycin (50 μg•mL-1), and penicillin (50 units•mL-1) and maintained in an incubator at 37 oC under 5% CO2 atmosphere.

pH-dependent intracellular fluorescence studies

About 1 × 105 HepG2 cells in 400 μL of medium were seeded in a confocal dish and incubated overnight. The culture medium was changed with solutions of ZnPcS8 and LDH-ZnPcS8 in the medium (0.1 μM, 400 μL) for 30 min under the same conditions. The cells were then rinsed with PBS and incubated with nigericin (Sigma) in phosphate buffer solutions (25 µM, 400 μL) at different pH (6.0, 6.5 and 7.4) for 20 min. The cells were washed with PBS twice and imaged using a fluorescent confocal microscope (Nikon). The photosensitizers were excited at 637 nm and monitored at 650-750 nm. The images were digitized and analyzed by using the Nikon C2 ROI Fluorescence Statistics software. The average intracellular fluorescence intensities (a total of 50 cells for each sample) were also determined.

Cellular uptake

Method 1

1 × 105 HepG2 cells in 400 μL of RPMI 1640 medium were seeded in a dish. After 24 h, LDH-ZnPcS8 or ZnPcS8 (0.1 μM, 400 μL) were added to the cells and incubated for 2 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS twice and imaged by using a fluorescent confocal microscope (Nikon). The photosensitizers were excited at 637 nm and detected at 650-750 nm.

Method 2

1 × 105 HepG2 cells in 400 μL of RPMI 1640 medium 400 μL were added to centrifuge tubes. After 24 h, LDH-ZnPcS8 or ZnPcS8 (4.0 μM, 400 μL) were added to the cells and the cells were incubated for 2 h. After washing with PBS twice, the cells were lysed in DMF and the mixture was sonicated for 3 min and centrifuged at 10000 rpm for 10 min. Finally, the fluorescence emission of the supernatant was detected in a spectrofluorometer and its concentration of phthalocyanine was calculated. Each experiment was repeated three times independently.

Subcellular localization

HepG2 cells at a density of 1 × 104 in 400 μL of RPMI 1640 medium were seeded in a confocal dish. After 24 h, LDH-ZnPcS8 or ZnPcS8 (0.1 μM, 400 μL) were added to the cells for 0.5 h. Lyso-Tracker (5 μM in 20 μL) was then added to the medium and incubated for another 60 followed by co-incubation with MitoTracker (5 μM in 20 μL) for 30 min. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS twice and imaged by using a fluorescent confocal microscope (Nikon). The Lyso-Tracker and MitoTracker were excited at 543 and 488 nm, and detected at 499-529 and 552-617 nm, respectively. The photosensitizers were excited at 637 nm and detected at 650-750 nm.

In vitro photodynamic activities

HepG2 cells at a density of 1 × 104 in 100 μL of RPMI 1640 medium were seeded in 96-well plates. After 24 h, LDH-ZnPcS8 or ZnPcS8 were added to the cells for 2 h. The cells were then washed with PBS twice and fed with culture medium again before illumination. A 500 W halogen lamp was used as the light source and a water tank was used for cooling and a colored glass filter to cut-on 610 nm. The fluence rate (λ > 610 nm) was 15 mW•cm-2 so an illumination of 30 min led to a total fluence of 27 J•cm-2. The cell viability was checked by the MTT assay.

In vivo studies

Female mice (~20 g) were purchased from Vital River Co., Ltd, China. All animal studies were performed in compliance with guidelines of the Animal Care Committee of Fuzhou University.

In vivo fluorescence imaging

HepG2 cells or mouse hepatoma H22 cells (~1 × 107 cells in 200 μL) were inoculated subcutaneously on the axilla of mice. When the tumor volume reached ~100 mm3, the mice were injected intravenously or intratumorally with an LDH-ZnPcS8 and ZnPcS8 aqueous solution (dose: ~0.45 μmol•Kg-1). In vivo fluorescence imaging of mice was performed from 695-770 nm at different time points with IVIS Lumina II imaging system or SI-image AMIX imaging system (excited at 640 nm).

In vivo photodynamic activities

Mouse hepatoma H22 cells (~1×107 cells in 200 μL) were injected subcutaneously into the axilla of mice. When the tumor reached ~100 mm3, the mice were injected intratumorally with an aqueous solution of LDH-ZnPcS8 (dose: ~0.9 μmol•Kg-1). After 5 h post-injection, the mice were irradiated with a laser (685 ± 4 nm; power density: 140 mW•cm-2) for 30 min (i.e., an optical fluence rate of 252 J•cm-2). The tumor size was determined daily by using a caliper for a duration of 12 d and calculated using the following formula: volume = (tumor length) × (tumor width)2 × 0.5. The relative tumor volume was calculated as V/V0 (V, V0 are the tumor volume detected at time t and t0, respectively). The tumor volumes were compared with three control groups of mice treated with LDH-ZnPcS8 but no light treatment and with saline in the presence or absence of light treatment. Eight mice were used for each group.

In vivo skin phototoxicity

Normal mice were injected intravenously with saline or LDH-ZnPcS8 (dose: ~0.9 μmol•Kg-1). After injection, the mice were kept inside with room light turned on during the day but turned off at night. Their body weights were checked every day. One day post-injection, 5 mice were kept outside with sunlight for 20 min while 5 mice were treated with a laser irradiation (252 J•cm-2) on their back. All mice were kept in room light and their skin status was monitored.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 21473033, 21301031), Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (Grant No.201135141001), and a grant from the National Creative Research Initiative programs of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2012R1A3A2048814).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary optical spectra, characterizations, and biological data.

References

- 1.Brown SB, Brown EA, Wallker I. The present and future role of photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:497–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolmans DE, Fukumura D, Jain RK. Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:380–7. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castano AP, Mroz P, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy and anti-tumour immunity. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:535–45. doi: 10.1038/nrc1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Celli JP, Spring BQ, Rizvi I. et al. Imaging and photodynamic therapy: mechanisms, monitoring, and optimization. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2795–838. doi: 10.1021/cr900300p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang P, Lin J, Wang X. et al. Light-triggered theranostics based on photosensitizer-conjugated carbon dots for simultaneous enhanced-fluorescence imaging and photodynamic therapy. Adv Mater. 2012;24:5104–10. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turan IS, Yildiz D, Turksoy A. et al. A bifunctional photosensitizer for enhanced fractional photodynamic therapy: singlet oxygen generation in the presence and absence of light. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:2875–8. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang C, Cheng L, Liu Y. et al. Imaging-guided pH-sensitive photodynamic therapy using charge reversible upconversion nanoparticles under near-infrared light. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23:3077–86. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gong H, Chao Y, Xiang J. et al. Hyaluronidase to enhance nanoparticle-based photodynamic tumor therapy. Nano Lett. 2016;16:2512–21. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng Y, Cheng H, Jiang C. et al. Perfluorocarbon nanoparticles enhance reactive oxygen levels and tumour growth inhibition in photodynamic therapy. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8785–92. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhuang X, Ma X, Xue X. et al. A photosensitizer-loaded DNA origami nanosystem for photodynamic therapy. ACS Nano. 2016;10:3486–95. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b07671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castano AP, Demidova TN, Hamblin MR, Mechanisms in photodynamic therapy. part two-cellular signaling, cell metabolism and modes of cell death. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2005;2:1–23. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(05)00030-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan W, Huang P, Chen X. Overcoming the Achilles' heel of photodynamic therapy. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:6488–519. doi: 10.1039/c6cs00616g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao W, Wang Z, Lv L. et al. Photodynamic therainduced enhancement of tumor vasculature permeability using an upconversion nanoconstruct for improved intratumoral nanoparticle delivery in deep tissues. Theranostics. 2016;6:1131–44. doi: 10.7150/thno.15262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yue C, Yang Y, Zhang C. et al. ROS-responsive mitochondria-targeting blended nanoparticles: chemo- and photodynamic synergistic therapy for lung cancer with on-demand drug release upon irradiation with a single light source. Theranostics. 2016;6:2352–66. doi: 10.7150/thno.15433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han K, Zhang WY, Zhang J. et al. Acidity-triggered tumor-targeted chimeric peptide for enhanced intra-nuclear photodynamic therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26:4351–61. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han D, Zhu G, Wu C. et al. Engineering a cell-surface aptamer circuit for targeted and amplified photodynamic cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2013;7:2312–9. doi: 10.1021/nn305484p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Z. A review of progress in clinical photodynamic therapy. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2005;4:283–93. doi: 10.1177/153303460500400308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vrouenraets MB, Visser GW, Snow GB. et al. Basic principles, applications in oncology and improved selectivity of photodynamic therapy. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:505–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Y, Lin Y, Zhang H. et al. A photodynamic therapy combined with topical 5-aminolevulinic acid and systemic hematoporphyrin derivative is more efficient but less phototoxic for cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142:813–21. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y, He L, Wu J. et al. Switchable PDT for reducing skin photosensitization by a NIR dye inducing self-assembled and photo-disassembled nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2016;107:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuh M, Nseyo UO, Potter WR. et al. Photodynamic therapy for palliation of locally recurrent breast carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1766–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.11.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wyss P, Schwarz V, Dobler-Girdziunaite D. et al. Photodynamic therapy of locoregional breast cancer recurrences using a chlorin-type photosensitizer. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:720–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lovell JF, Liu TW, Chen J. et al. Activatable photosensitizers for imaging and therapy. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2839–57. doi: 10.1021/cr900236h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majumdar P, Nomula R, Zhao J. Activatable triplet photosensitizers: magic bullets for targeted photodynamic therapy. J Mater Chem C. 2014;2:5982–97. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lovell JF, Chan MW, Qi Q. et al. Porphyrin FRET acceptors for apoptosis induction and monitoring. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:18580–2. doi: 10.1021/ja2083569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolemen S, Isık M, Kim GM. et al. Intracellular modulation of excited-state dynamics in a chromophore dyad: differential enhancement of photocytotoxicity targeting cancer cells. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:5340–44. doi: 10.1002/anie.201411962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H, Tian J, He W. et al. H2O2-activatable and O2-evolving nanoparticles for highly efficient and selective photodynamic therapy against hypoxic tumor cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;13:1539–47. doi: 10.1021/ja511420n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim H, Kim Y, Kim IH. et al. ROS-responsive activatable photosensitizing agent for imaging and photodynamic therapy of activated macrophages. Theranostics. 2014;4:1–11. doi: 10.7150/thno.7101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu D, Song G, Li Z. et al. A two-dimensional molecular beacon for mRNA-activated intelligent cancer theranostics. Chem Sci. 2015;6:3839–44. doi: 10.1039/c4sc03894k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuan Y, Zhang CJ, Gao M. et al. Specific light-up bioprobe with aggregation-induced emission and activatable photoactivity for the targeted and image-guided photodynamic ablation of cancer cells. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:1780–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichikawa Y, Kamiya M, Obata F. et al. Selective ablation of β-galactosidase-expressing cells with a rationally designed activatable photosensitizer. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:6772–5. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J, Tung CH, Choi Y. Smart dual-functional warhead for folate receptor-specific activatable imaging and photodynamic therapy. Chem Commun. 2014;50:10600–3. doi: 10.1039/c4cc04166f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan H, Yan G, Zhao Z. et al. A smart photosensitizer-manganese dioxide nanosystem for enhanced photodynamic therapy by reducing glutathione levels in cancer cells. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:5477–82. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng B, Zhou F, Xu Z. et al. Versatile prodrug nanoparticles for acid-triggered precise imaging and organelle-specific combination cancer therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2016;26:7431–42. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durantini AM, Greene LE, Lincoln R. et al. Reactive oxygen species mediated activation of a dormant singlet oxygen photosensitizer: from autocatalytic singlet oxygen amplification to chemicontrolled photodynamic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:1215–25. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang D, Wang T, Liu J. et al. Acid-activatable versatile micelleplexes for PD-L1 blockade-enhanced cancer photodynamic immunotherapy. Nano Lett. 2016;16:5503–13. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b01994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Q, Feng L, Liu J. et al. Intelligent albumin-MnO2 nanoparticles as pH-/H2O2-responsive dissociable nanocarriers to modulate tumor hypoxia for effective combination therapy. Adv Mater. 2016;28:7129–36. doi: 10.1002/adma.201601902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Zhou K, Huang G. A Nanoparticle-based strategy for the imaging of a broad range of tumours by nonlinear amplification of microenvironment signals. Nat Mater. 2014;13:204–12. doi: 10.1038/nmat3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng LB, Zhang W, Li D. et al. pH-Responsive supramolecular vesicles assembled by water-soluble pillar[5]arene and a BODIPY photosensitizer for chemo-photodynamic dual therapy. Chem Commun. 2015;51:14381–4. doi: 10.1039/c5cc05785j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tian J, Zhou J, Shen Z. et al. A pH-activatable and aniline-substituted photosensitizer for near-infrared cancer theranostics. Chem Sci. 2015;6:5969–77. doi: 10.1039/c5sc01721a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tian J, Ding L, Xu HJ. et al. Cell-specific and pH-activatable rubyrin-loaded nanoparticles for highly selective near-infrared photodynamic therapy against cancer. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:18850–8. doi: 10.1021/ja408286k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Battogtokh G, Ko YT. Active-targeted pH-responsive albumin-photosensitizer conjugate nanoparticles as theranostic agents. J Mater Chem B. 2015;3:9349–59. doi: 10.1039/c5tb01719j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuan Y, Kwok RT, Tang BZ. et al. Smart probe for tracing cancer therapy: selective cancer cell detection, image-guided ablation, and prediction of therapeutic response in situ. Small. 2015;11:4682–90. doi: 10.1002/smll.201501498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lau JT, Lo PC, Jiang XJ. et al. A dual activatable photosensitizer toward targeted photodynamic therapy. J Med Chem. 2014;57:4088–97. doi: 10.1021/jm500456e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ke MR, Ng DK, Lo PC. A pH-responsive fluorescent probe and photosensitiser based on a self-quenched phthalocyanine dimer. Chem Commun. 2012;48:9065–7. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34327d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park SY, Baik HJ, Oh YT. et al. A smart polysaccharide/drug conjugate for photodynamic therapy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:1644–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201006038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He L, Li Y, Tan CP. et al. Cyclometalated iridium(III) complexes as lysosome-targeted photodynamic anticancer and real-time tracking agents. Chem Sci. 2015;6:5409–18. doi: 10.1039/c5sc01955a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braterman PS, Xu ZP, Yarberryin F. Auerbach SM, Carrado KA, Dutta PK, Ed. New York: Marcel Decker; 2004. Handbook of layered materials; pp. 373–474. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu ZP, Stevenson G, Lu CQ. et al. Stable suspension of layered double hydroxide nanoparticles in aqueous solution. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:36–7. doi: 10.1021/ja056652a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ladewig K, Xu ZP, Lu GQ. Layered double hydroxide nanoparticles in gene and drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Del. 2009;6:907–22. doi: 10.1517/17425240903130585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park DH, Cho J, Kwon OJ. et al. Biodegradable inorganic nanovector: passive versus active tumor targeting in siRNA transportation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:4582–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liang RZ, Tian R, Ma LN. et al. A supermolecular photosensitizer with excellent anticancer performance in photodynamic therapy. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:3144–51. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choy JH, Kwak SY, Jeong YJ. et al. Inorganic layered double hydroxides as nonviral vectors. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2000;39:4041–45. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20001117)39:22<4041::aid-anie4041>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li XS, Ke MR, Huang W. et al. A pH-responsive layered double hydroxide (LDH)-phthalocyanine nanohybrid for efficient photodynamic therapy. Chem Eur J. 2015;21:3310–7. doi: 10.1002/chem.201404514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li XS, Ke MR, Zhang MF. et al. A non-aggregated and tumour-associated macrophage-targeted photosensitiser for photodynamic therapy: a novel zinc(II) phthalocyanine containing octa-sulphonates. Chem Commun. 2015;51:4704–7. doi: 10.1039/c4cc09934f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Darwent JR, Douglas P, Harriman A. et al. Metal phthalocyanines and porphyrins as photosensitizers for reduction of water to hydrogen. Coord Chem Rev. 1982;44:83–126. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Novell JF, Chen J, Jarvi MT. et al. FRET quenching of photosensitizer singlet oxygen generation. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:3203–11. doi: 10.1021/jp810324v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Helmlinger G, Sckell A, Dellian M. et al. Acid production in glycolysis-impaired tumors provides new insights into tumor metabolism. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:1284–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jahde E, Glusenkamp KH, Rajewsky MF. Nigericin enhances mafosfamide cytotoxicity at low extracellular pH. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1991;27:440–4. doi: 10.1007/BF00685157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jiang XJ, Lo PC, Yeung SL. et al. A pH-responsive fluorescence probe and photosensitiser based on a tetraamino silicon(IV) phthalocyanine. Chem Commun. 2010;46:3188–90. doi: 10.1039/c000605j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu W, Chen N, Jin H. et al. Intravenous repeated-dose toxicity study of ZnPcS2P2-based-photodynamic therapy in beagle dogs. Toxicol Pharmacol. 2007;47:221–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary optical spectra, characterizations, and biological data.