Abstract

Introduction

Primary healthcare practitioners (PHCPs) can contribute to the control of cancer by promoting healthy lifestyles to patients. Given the scarcity of data in the Middle East on this subject, we sought to determine, through a cross-sectional survey, the status of healthy lifestyle promotion by PHCPs (physicians, nurses, midwives, nurse aids) in Jordan.

Methods

Building on published studies, an Arabic questionnaire was developed to measure knowledge, perceptions and practices of Jordanian PHCPs with regard to healthy lifestyle counselling. A purposive sample of 20 clinics covering the main regions of Jordan was selected and all PHCPs were asked to complete the questionnaire.

Results

322 practitioners (32.3% physicians) responded (a 75.1% response rate). 24.4% of PHCPs were current cigarette smokers (physicians 44.2%). Roughly 58% of physicians and 50% of non-physicians reported advising the majority of patients to quit tobacco, but proportions were lower for providing other services (eg, asking about frequency of tobacco use, inquiring about diet and exercise, providing evidence-based guidance on quitting tobacco or improving diet and activity). Only 8% of the sample reported collectively asking the majority of patients about smoking status, exercise and diet; and providing evidence-based tips to improve these. Among physicians and non-physicians, 14.2% and 40.4% were able to identify the lifestyle-related risk factors associated with breast, colorectal and lung cancer. In multivariable analyses, confidence was the only significant variable associated with provision of counselling on healthy lifestyles.

Conclusions

Among Jordanian PHCPs, primary prevention services are underprovided, and data suggest ample room to improve PHCPs' skills and practices.

Keywords: cancer, prevention, PRIMARY CARE, PREVENTIVE MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, no other study has been publicly availed with regard to the level of preparedness of primary healthcare practitioners in Jordan to provide cancer prevention counselling to patients.

The employed survey covered several lifestyle-related counselling practices rather than focusing on one only, under the premise that any primary healthcare practitioner should be well versed with all lifestyle-related factors.

The study covered primary healthcare clinics from across the country in Jordan.

The study was cross-sectional in nature and not powered to conduct in-depth stratified analyses.

Possible factors influencing the provision of healthy lifestyle-related services are numerous, and an in-depth analysis of these factors was beyond the scope of the analysis.

Introduction

The growing burden of non-communicable disease (NCD) is a challenge being faced by most countries and has moved leading health organisations to reiterate the importance of disease prevention through healthy lifestyles.1 2 Cancer in particular, owing to the dramatic health and economic toll it exerts on afflicted patients, necessitates serious efforts to promote lifestyles that lower the risk of this NCD.3 4 One recommended strategy is through healthy lifestyle promotion (to patients) by healthcare practitioners.2 5 Primary healthcare practitioners (PHCPs) in particular are acknowledged to be an effective tool for healthy lifestyle promotion,6–9 and are in a key position to play a highly valuable role in cancer prevention.4 10 Despite the clear importance of PHCPs engaging in NCD prevention, they face barriers and have yet to realise their full potential in delivering such basic and essential services.11 12

In the Middle East, countries struggle to address the rising NCD and cancer burden amid environments of resource constraints and political unrest.13 14 A country with a largely young population, Jordan faces further challenges in the advent of its population ageing.15 To add to these challenges, Jordan's lay public appears to be regressing with regard to lifestyle: tobacco use is increasing (with most recent estimates being 32.3%),16 and only 27% of the population reports being physically active.17 It is thus not surprising that the three most commonly occurring cancers in the country, breast, colorectal and lung,18 are associated at least in part with unhealthy lifestyle practices. Mounting evidence also indicates that the public in Jordan are underinformed with regard to cancer prevention and risks.17 19–21 However, if the public is to become better informed, healthcare providers must also be at the forefront to address this matter: the majority of the public prefers to obtain its cancer knowledge through healthcare providers (rather than other information-seeking channels).17

Models have been put forth with regard to what healthy lifestyle counselling should entail,5 and studies have explored the viability of NCD prevention through PHCPs.12 However, there are limited data specific to the region's PHCPs. We sought to study a Middle Eastern healthcare system that represents a country and region which faces various challenges that are likely to hinder the provision of NCD and cancer prevention services. Specifically, we sought to assess practices and perceptions among PHCPs in Jordan's largest public healthcare (Ministry of Health) clinics with regard to cancer prevention through healthy lifestyle counselling, thereby providing much-needed insight to inform interventions that promote cancer (and other NCDs) prevention. In addition, research generated in Jordan can also be useful for other neighbouring countries with similar sociopolitical challenges.

Methods

Setting and sample

A purposive sample of clinics representing the different types of public primary healthcare clinics in Jordan and covering the three main regions of the country (North, Central, South) was selected by the Jordanian Ministry of Health. Throughout February and March of 2014, all active PHCPs (ie, physicians, nurses, midwives and nurse aids) in each clinic visited were asked to complete the questionnaire.

Questionnaire

The self-administered Arabic questionnaire was developed using the social cognitive theory as a guiding framework.22 Other studies which evaluated professional practices in the area of healthy lifestyle counselling and cancer screening also were reviewed.23–29 However, a substantial part of the final tested questionnaire was customised to the local primary healthcare environment, covering key practices that were feasible and of relevance to promote among Jordanian PHCPs.

Content validity for the questionnaire was ensured by reviewing it with physicians and allied health staff working in the Jordanian Ministry of Health as well as the King Hussein Cancer Center; and the tool was piloted in one primary healthcare clinic. Cronbach’s α (internal consistency) of the questionnaire was 0.80.

The final questionnaire consisted of two main components: provider-reported knowledge, attitudes and practices pertaining to cancer-related healthy lifestyle counselling (tobacco use, healthy diet, physical activity); and provider-reported knowledge, attitudes and practices pertaining to counselling on the perceived burden and early signs and symptoms of the most prevalent cancers in Jordan: breast, colorectal and lung cancers. The latter component is beyond the scope of the current analysis, and descriptions of the sections covering only the former component are therefore included below.

Practices: we measured the extent to which various actions (asking about each lifestyle factor, explaining the factor's association with cancer, and providing evidence-based recommendations on how to improve or perform each factor) were performed for adults visiting the clinic. Specific lifestyle factors included healthy diet, physical activity, obesity and smoking. Practitioners were asked to estimate the percentage of patients aged 18 years or older on whom the actions were performed in the past 2 months. Responses to these variables were further categorised during analysis (whether or not each activity was performed for the majority—70% or more—of adult patients seen). Given our interest in ultimately promoting the provision of healthy lifestyle counselling to the majority of patients in a comprehensive manner (ie, encompassing smoking, diet, physical activity and obesity), we also defined a compound variable of overall provision of healthy lifestyle counselling by observing the proportion of practitioners who reported asking about smoking status, exercise status and diet; and providing evidence-based tips to improve these in 70% or more of patients.

Level of agreement (on a five-point scale) with statements covering the provision of healthy lifestyle counselling: the questionnaire specifically gauged the perceived value of healthy lifestyle counselling, negative and positive outcomes of such counselling; need for counselling; perceived professional responsibility to provide counselling; and the need for training in this area. Responses to these variables were further categorised during analysis (for each attitudinal statement, whether or not respondents had an unfavourable perception that could deter from the provision of healthy lifestyle counselling).

Perceived confidence (on a five-point scale) to ask about each lifestyle factor, explain the factor's association with cancer, and provide evidence-based recommendations on how to improve or perform each factor: responses to these variables were dichotomised during analysis (confident or highly confident vs all other responses). A dummy variable also was created to reflect whether or not practitioners concurrently reported confidence to provide several activities.

A general section probing barriers to counselling patients on cancer prevention and early detection was included. Various factors (practitioner-related; patient-related; system-related) were listed and practitioners rated each according to the level of significance (major barrier; moderate barrier; not a barrier).

Knowledge with regard to the effect of lifestyle factors on the risk of incidence of breast, colorectal and lung cancers (increases risk, decreases risk, no effect, don't know). A dummy variable was also created to reflect on whether or not practitioners were able to concurrently identify lifestyle-related risk factors associated with each of the three cancer sites probed.

A section measuring practitioners' demographic and professional characteristics.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated to present the characteristics of the sample and the attitudes, practices and knowledge levels of practitioners with regard to various elements of cancer prevention through healthy lifestyle counselling. Descriptive statistics were further analysed in a bivariate manner for physicians and non-physicians, since this particular factor was of practical relevance in informing recommendations for future training efforts (ie, whether or not they may need to be tailored to the profession).

All analyses were performed using STATA SE V.12.1.

Multivariate logistic regressions were run to assess the possible demographic, professional, attitudinal and knowledge factors that were associated with providing specific actions (eg, asking about and providing evidence-based recommendations for healthy eating; asking about and providing evidence-based recommendations for exercise; and asking about providing evidence-based recommendations to stop smoking). Independent variables explored in the models included gender, age, being a physician, whether or not the respondent engaged in a healthy lifestyle (exercised regularly during the week, ate fruits and legumes regularly during the week, did not eat red meat or fast foods frequently during the week), whether or not the respondent valued healthy lifestyle counselling, knowledge of the lifestyle factor's effect on risk of cancer, and confidence in providing the action.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 322 practitioners (218 nurses, midwives and nurse aids; 104 physicians) across 20 clinics in the North (8 clinics), Central (9 clinics) and South (3 clinics) regions of Jordan responded to the survey, resulting in a 75.1% response rate (the response rate was calculated as a percentage of the number of respondents divided by the number of practising physicians and nurses in the clinics). The sample had a larger proportion of non-physicians and women than physicians and men, respectively (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, professional and lifestyle characteristics of the sample of primary care physicians and nurses across Jordan

| Nurses/assistants, midwives (n=218) | Physicians (n=104) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range) | 35.4 (22–55) | 42.7 (25–64) |

| Mean years since graduating with highest professional degree (range) | 13.5 (1–35) | 16.3 (1–34) |

| Female, n (%) | 180 (85.3%) | 28 (27.7%) |

| Currently smoke cigarette, n (%) | 35 (16.2%) | 46 (44.2%) |

| Currently smoke waterpipe, n (%) | 29 (13.6%) | 19 (18.3%) |

| Mean BMI (range) | 26.8 (16.5–77.8) | 25.8 (19.1–32.8) |

| Exercise regularly, n (%) | 26 (12.1%) | 21 (20.8%) |

| Ate legumes on 6 or more days of the week, n (%) | 33 (15.5%) | 28 (27.7%) |

| Ate fruits on 6 or more days of the week, n (%) | 45 (21.1%) | 40 (39.2%) |

| Ate red meat on 3 or more days of the week, n (%) | 76 (36.0%) | 54 (52.9%) |

| Ate fast food on 3 or more days of the week, n (%) | 43 (20.1%) | 17 (16.5%) |

BMI, body mass index.

With regard to lifestyle practices, 24.4% of the sample were current cigarette smokers (with physicians, who were largely male, having a smoking rate of 44.2%); 14.8% were current waterpipe smokers. Unhealthy lifestyle practices were decipherable, most noticeably the low reported rates of regular physical activity.

Current practices

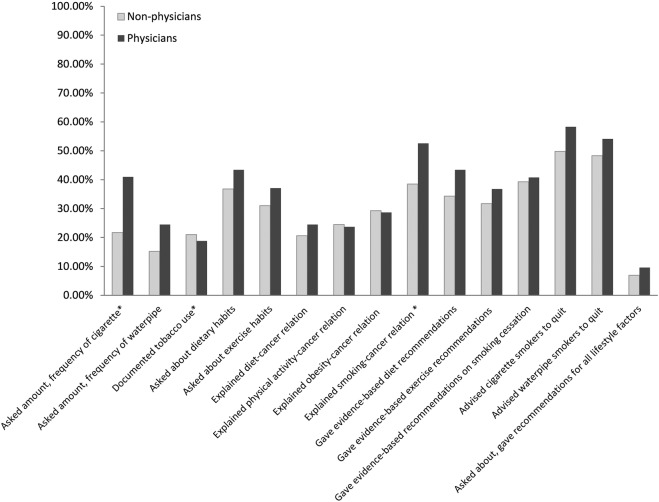

Reported frequencies of various activities related to counselling on healthy lifestyles are included in figure 1. The most frequently reported activity was advising tobacco users to quit: ∼58% of physicians and 50% of non-physician PHCPs reported doing this with the majority of their patients. However, less than half of the practitioners reported providing to the majority of their adult patients other key services such as asking about the frequency of tobacco use, inquiring about dietary and exercise habits, and providing patients with evidence-based guidance with regard to quitting tobacco and improving their diet and physical activity. When the concurrent provision of practices was observed, rates of provision dropped further: roughly 8% of the sample reported asking about smoking status, exercise status and diet; and providing evidence-based tips to improve these in the majority of patients.

Figure 1.

Average proportions of primary care providers in clinics in Jordan (physicians vs non-physicians) who reported performing various lifestyle-related counselling activities in at least 70% of the adult patients (over 18) they saw; *significant χ2 statistic (p<0.05) when comparing physicians to non-physicians.

Perceptions

Table 2 lists various statements which practitioners were asked to express their level of agreement with, and the proportions of respondents with perceptions that may deter from provision of healthy lifestyle counselling. With the exception of a few statements, results were comparable between physicians and non-physicians. A substantial (61.7%) proportion of practitioners felt that patients were sufficiently knowledgeable (and not in need of education) with regard to smoking's association with cancer, while ∼41% and 38% felt similarly with regard to patient's knowledge and need of education on the diet–cancer and physical activity–cancer association (respectively). With regard to outcome expectancies, 45.5% of practitioners did not perceive that their smoking cessation advice would increase the likelihood of a patient quitting, while roughly 37% and 30% did not perceive that their advice would influence the likelihood of patients improving their exercise habits or dietary ones, respectively. Furthermore, 40.5% of respondents did not reject the statement that lifestyle counselling would bother patients, and 36.5% were unable to reject the statement that counselling made them feel uncomfortable. In addition, 61.6% of practitioners did not reject the suggestion that ‘counselling on prevention of other non-communicable diseases is more important than counselling on cancer prevention’. Finally, variability was observed with regard to which PHCP (nurse or physician) should be responsible for healthy lifestyle counselling.

Table 2.

Attitudes regarding healthy lifestyle counselling and cancer prevention among practitioners in primary healthcare clinics in Jordan

| Statement | Non-physicians | Physicians |

|---|---|---|

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘preventing cancer is possible’ (n=320)* | 72 (33.3%) | 23 (22.6%) |

| Proportion agreeing/neutral that ‘most patients aware of smoking–cancer relation, do not need more information’ (n=314) | 129 (60.9%) | 65 (65.0%) |

| Proportion agreeing/neutral that ‘most patients aware of diet–cancer relation, do not need more information’ (n=318) | 92 (43.2%) | 37 (35.9%) |

| Proportion agreeing/neutral that ‘most patients aware of exercise–cancer relation, do not need more information’ (n=316) | 84 (39.8%) | 36 (35.0%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘smoking is a medical condition needing treatment’ (n=316) | 36 (16.8%) | 18 (18.0%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘obesity is a medical condition needing treatment’ (n=317) | 19 (9.0%) | 6 (5.8%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that they are ‘bothered when seeing effects of unhealthy lifestyles on patients’ (n=310) | 35 (16.8%) | 14 (14.0%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘likelihood that patient quits smoking increases if I advise him/her to do so’ (n=314) | 90 (42.7%) | 53 (52.5%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘likelihood that patient follows healthy diet increases if I advise him/her to do so’ (n=311) | 66 (31.4%) | 28 (28.3%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘likelihood that patient exercises increases if I advise him/her to do so’ (n=313) | 77 (37.0%) | 39 (37.9%) |

| Proportion agreeing/neutral that ‘counselling on prevention of non-communicable diseases (like diabetes and hypertensions) is more important than counselling on prevention of cancer’ (n=318) | 131 (60.7%) | 65 (65.0%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘physicians in clinic should be trained to provide counselling on healthy lifestyle practices’ (n=317) | 22 (10.3%) | 16 (15.7%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘non-physicians staff in the clinic should be trained to provide counselling on healthy lifestyle practices’ (n=321) | 24 (11.1%) | 9 (8.7%) |

| Proportion agreeing/neutral that ‘most patients won't take advice with regard to healthy lifestyle practices seriously’ (n=311) | 151 (72.3%) | 66 (66.0%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that they ‘feel more confident counselling patients on healthy lifestyle practices they successfully engage in themselves’ (n=321) | 29 (13.5%) | 8 (7.7%) |

| Proportion agreeing/neutral that they ‘prefer counselling only patients who they feel will listen to them on healthy lifestyle practices’ (n=320) | 130 (60.5%) | 59 (57.3%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘counselling patients on healthy lifestyle practices gives a feeling of self-respect and self-satisfaction’ (n=322) | 33 (15.2%) | 11 (10.7%) |

| Proportion agreeing/neutral that ‘talking about healthy lifestyle practices bothers patients and negatively impacts relationship with them’ (n=311) | 84 (40.2%) | 42 (42.0%) |

| Proportion agreeing/neutral that ‘they feel uncomfortable talking about healthy lifestyle practices with patients’ (n=318) | 81 (37.9%) | 35 (34.3%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘patients will change their lifestyle practices for the better if counselled on healthy lifestyle practices’ (n=316) | 48 (22.8%) | 29 (28.2%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that their ‘counselling on healthy lifestyle practices will lower patients’ risk of cancer’ (n=322) | 72 (33.3%) | 30 (28.9%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that their ‘counselling on healthy lifestyles will improve patient care’ (n=319)* | 34 (15.7%) | 7 (6.9%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘counselling on healthy lifestyles should be physician's role’ (n=322)* | 95 (44.2%) | 62 (59.6%) |

| Proportion disagreeing/neutral that ‘counselling on healthy lifestyles should be nurse's role’ (n=321)* | 84 (38.9%) | 26 (25.0%) |

*Significant χ2 statistic when comparing physicians to non-physicians (p<0.05).

When probed with regard to confidence (table 3), lower proportions of non-physicians tended to report being confident across the healthy lifestyle counselling tasks listed. Relatively low proportions (not exceeding 55%) of all practitioners reported high confidence in documentation of tobacco use and frequency; and relatively lower proportions of practitioners reported confidence in explaining the effects of specific lifestyle factors such as obesity and diet on the risk of cancer.

Table 3.

Proportions of practitioners reporting confidence in providing various healthy lifestyle counselling activities within primary healthcare clinics in Jordan

| N (%) non-physicians | N (%) physicians | |

|---|---|---|

| Ask about amount and frequency of cigarette or waterpipe use* | 119 (55.1%) | 70 (70.0%) |

| Document amount and frequency of cigarette or waterpipe use | 98 (46.0%) | 54 (54.6%) |

| Explain effect of smoking on risk of incidence of different cancers* | 131 (61.8%) | 79 (79.0%) |

| Advise cigarette smoker to quit* | 139 (65.9%) | 78 (77.2%) |

| Advise waterpipe smoker to quit* | 134 (63.5%) | 75 (78.1%) |

| Ask patient about his/her dietary habits | 139 (65.6%) | 66 (68.0%) |

| Ask patient about his/her physical activity | 130 (63.7%) | 68 (69.4%) |

| Explain effect of diet on risk of incidence of different cancers | 107 (49.8%) | 61 (60.4%) |

| Explain effect of physical activity on risk of incidence of different cancers* | 117 (54.4%) | 69 (68.3%) |

| Explain effect of obesity on risk of incidence of different cancers* | 103 (48.1%) | 61 (60.4%) |

| Give patient evidence-based recommendations to improve his/her dietary habits* | 125 (59.0%) | 75 (74.3%) |

| Give patient evidence-based recommendations to improve his/her activity* | 120 (56.1%) | 75 (72.8%) |

| Give patient evidence-based recommendations on quitting smoking | 143 (66.5%) | 72 (72.0%) |

| Reporting confidence in all the above-listed activities* | 24 (11.0%) | 21 (20.2%) |

*Significant χ2 statistic when comparing physicians to non-physicians (p<0.05).

Knowledge

When analysing knowledge of lifestyle factors and whether or not they influenced the risk of breast, colorectal and lung cancers, high levels of knowledge were observed with roughly no <70% of practitioners identifying individual risk factors per cancer site appropriately (with the exception of red meat and high fibre diet and colorectal cancer risk: low levels of knowledge with regard to these factors were driven by the substantially lower proportion of non-physicians who did not know of the association of these dietary staples with cancer). When a compound variable reflecting whether or not practitioners were able to identify lifestyle-related risk factors associated with each of the three cancer sites probed, lower proportions of practitioners could do so (14.2% of non-physicians and 40.4% of physicians).

Barriers

The most frequently reported barriers to the provision of healthy lifestyle counselling were largely patient related. These included ‘patients do not want to quit smoking’, ‘low literacy of patients’, ‘patients do not want to make dietary changes’, ‘patients scared or bothered if cancer is discussed’ and ‘patients cannot access healthy food’.

Multivariable analysis

Multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the association of various factors with the provision of healthy lifestyle counselling. Across models run to predict correlates of asking about and providing evidence-based recommendations on healthy lifestyle factors, confidence was the only significant independent variable. For example, those reporting confidence in asking about and providing recommendations for a healthy lifestyle (healthy diet, exercise and smoking cessation) were 30% more likely to engage in these activities than those who did not report such confidence. Those reporting confidence in asking about smoking status, advising quitting and providing recommendations for quitting were roughly twice as likely to engage in these activities than those who did not.

Discussion

Equipped and knowledgeable PHCPs can be a key and cost-effective resource for counselling on and contributing to the prevention of cancer and other NCDs. Despite this long-standing fact, the findings of our study confirm, in governmental primary care clinics in Jordan, the underprovision of various activities related to healthy lifestyle counselling; and the existence of knowledge gaps and misperceptions that can deter from such counselling within the primary healthcare setting. Our findings, based on a sample of clinics representing the three main geographic areas of the country, shed light on an understudied practitioner population existing in a developing region (and serving a significant segment of the country's host population as well as incoming refugees from surrounding areas). Thus, the findings can provide the impetus to avail of and inform interventions to improve practitioner perceptions, knowledge and practices in this area of the world.

With regard to the current status of healthy lifestyle counselling, there was an underprovision of various important aspects of healthy lifestyle counselling. Only advising cigarette smokers to quit was estimated to have been provided to roughly half of the patients seen. When we combined counselling activities, as exemplified by the proportion of practitioners who reported asking about smoking status, exercise status and diet, and providing evidence-based tips to improve these in the majority of patients, it was evident that there was a dramatic underprovision of comprehensive lifestyle counselling. Relatedly, individual traits existed which could negatively influence the likelihood that PHCPs would engage in healthy lifestyle counselling. Our sample of PHCPs generally did not engage in regular physical activity, did not (in high proportions) follow a healthy diet and a substantial proportion of physicians (44.2%) were cigarette smokers.

With regard to perceptions, many practitioners believed that patients already knew enough about lifestyle factors such as smoking and did not need further counselling. Furthermore, patient-stemming barriers (as a result of patient attitudes, illiteracy) were the most frequently cited impediments to the provision of counselling. Many of the practitioners in our sample also did not perceive that their counselling would increase the likelihood that a patient changes their behaviour. Finally, while knowledge about individual lifestyle factors and their association with cancer was generally high, knowledge levels were substantially lower when examining indicators of comprehensive (in the context of the lifestyle factors and cancers we probed) knowledge.

The determinants of healthy lifestyle counselling by practitioners vary in the literature and include, at the level of the practitioner, age, gender, specialty, extent of training, identifying a lifestyle-related risk factor in a patient, practising the health habit counselled on, reporting confidence to counsel and perceiving value in the practice.23 29–32 Our multivariable analyses only revealed self-efficacy as a consistent significant predictor of provision of healthy lifestyle counselling. Self-efficacy, however, is multifaceted, playing an intricate role in determining health behaviour both by directly influencing that behaviour, and by influencing (and being influenced by) various attitudes and individual characteristics that also influence the performance of the behaviour.22 Our results provide some insight into factors that most likely influence self-efficacy, and thus provide various discussion and educational points for inclusion in interventions (such as training) that can improve the self-efficacy of PHCPs to provide healthy lifestyle counselling. Differences among physicians and non-physicians that we detected in some results also emphasise the need to address—in any potential intervention—each professional category in a customised manner.

The possible factors influencing the provision of healthy lifestyle-related services are numerous and span multiple levels and individuals.12 33 34 Although we could not cover the full scope of these factors, our findings can contribute data and insight to inform the planning of interventions to improve healthy lifestyle counselling through PHCPs in Jordan.

Our study has its limitations. Our survey was a descriptive cross-sectional one and relied on the use of a tool that had not been previously validated (we designed the tool for the specific purpose of the study). Although our results indicate that the tool was reliable, our findings should be interpreted with this in mind. In addition, we were not able to verify practitioner-reported results with objective measures. The documentation systems in the clinics we targeted are underdeveloped, and we were also unable to conduct patient interviews to verify our findings. Nevertheless, given that our results indicate substantial practice and knowledge gaps—particularly when gauging whether or not providers availed several actions collectively, or could identify all the relevant risk factors for the cancers evaluated—it is unlikely that our findings or conclusions would have differed in direction had we supplemented our data with more objective measures. Furthermore, although we highlight the strong association of reported confidence with providing counselling on cancer prevention through healthy lifestyles, our intention was not to identify causal factors but rather to offer practical information that can be used in future efforts to educate healthcare professionals in this sector. Confidence is likely to have been shaped by other inter-related factors such as skills, knowledge and perceptions with regard to the value of counselling. Determining these intricate connections was beyond the scope of our study. We also did not include primary healthcare clinics in the Royal Medical Services sector (a subsidised public healthcare system that was built to serve army officers and their beneficiaries and subsequently grew to provide care to non-veterans who are willing to pay for such services). However, the Ministry of Health's primary healthcare clinics in Jordan are the largest primary care services in the country, are accessible to all Jordanians and are accessed by more than half of the population.35 36 Finally, with regard to limitations, we were constrained with a purposive sample of 20 clinics. The Jordanian Ministry of Health nominated a purposive sample that it deemed representative of its clinics across the country. Owing to time constraints that practitioners in this sector typically face, the Ministry of Health restricted its selection to these 20 clinics. Having said that, we conducted post hoc power analyses to ensure that our study was sufficiently powered to detect various estimates.

Despite our limitations, we were able to study a sample of clinics that covered the main governorates in the country and benefited from a relatively high response rate. Our findings indicate that, among Jordanian PHCPs in governmental healthcare clinics, primary cancer prevention services through healthy lifestyle counselling are underprovided. Our data also suggest that there is ample room for improving PHCPs' skills and practices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the data management efforts of Asiha Shtaiwi and Asma Hatoqai from the Cancer Control Office at King Hussein Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Contributors: NAO contributed to the planning, conduct, data processing and analysis, manuscript development, and final manuscript review. MAH contributed to the planning, conduct, manuscript development and final manuscript review. RAS contributed to the conduct, data processing, manuscript development and final manuscript review. FIH contributed to the planning, manuscript development and final manuscript review.

Funding: Funding was provided through the King Hussein Cancer Center.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Hussein Cancer Center (KHCC, the only comprehensive national cancer treatment facility in Jordan).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data are available by emailing nobeidat@khcc.jo.

References

- 1.United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf (accessed 31 Mar 2016).

- 2.World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: 2013–2020. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press, 2013. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/94384/1/9789241506236_eng.pdf (accessed 30 Mar 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F, Jemal A, Torre LA, et al. Long-term realism and cost-effectiveness: primary prevention in combatting cancer and associated inequalities worldwide. J Natl Cancer Inst 2015;107:djv273 10.1093/jnci/djv273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rose MG, DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, et al. Oncology in primary care. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arena R, Lavie CJ, Hivert MF, et al. Who will deliver comprehensive healthy lifestyle interventions to combat non-communicable disease? Introducing the healthy lifestyle practitioner discipline. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2016;14:15–22. 10.1586/14779072.2016.1107477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. The world health report 2008: primary health care now more than ever. Retrieved 15/5/2011 from. http://www.who.int/whr/2008/en/index.html

- 7.Eyre H, Kahn R, Robertson RM, et al. Preventing cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes: a common agenda for the American Cancer Society, the American Diabetes Association, and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2004;109:3244–55. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133321.00456.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise M, Nutbeam D. Enabling health systems transformation: what progress has been made in re-orienting health services? Promot Educ 2007;14(Suppl 2):23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham A, Kerner J, Quinlan K, et al. Translating cancer control research into primary care practice: a conceptual framework. Am J Lifestyle Med 2008;2:241–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin G, Berendsen A, Crawford SM, et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1231–72. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00205-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kardakis T, Weinehall L, Jerden L, et al. Lifestyle interventions in primary health care: professional and organizational challenges. Eur J Public Health 2014;24:79–84. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubio-Valera M, Pons-Vigues M, Martinez-Andres M, et al. Barriers and facilitators for the implementation of primary prevention and health promotion activities in primary care: a synthesis through meta-ethnography. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e89554 10.1371/journal.pone.0089554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Razeq H, Attiga F, Mansour A. Cancer care in Jordan. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 2015;8:64–70. 10.1016/j.hemonc.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahim HF, Sibai A, Khader Y, et al. Non-communicable diseases in the Arab world. Lancet 2014;383:356–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62383-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Higher Population Council. The demographic opportunity in Jordan—a policy document. http://www.hpc.org.jo/hpc/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=PQ67t2DHLEA%3D (accessed 27 Mar 2016).

- 16.Jaghbir M, Shreif S, Ahram M. Pattern of cigarette and waterpipe smoking in the adult population of Jordan. East Mediterr Health J 2014;20:529–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad MM, Dardas LA, Ahmad H. Cancer prevention and care: a national sample from Jordan. J Cancer Educ 2015;30:301–11. 10.1007/s13187-014-0698-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jordan Cancer Registry. Cancer incidence in Jordan. Jordanian Ministry of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad MM, Al-Gamal E. Predictors of cancer awareness among older adult individuals in Jordan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:10927–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omran S, Barakat H, Muliira JK, et al. Dietary and lifestyle risk factors for colorectal cancer in apparently healthy adults in Jordanian hospitals. J Cancer Educ 2015. 10.1007/s13187-015-0970-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taha H, Jaghbeer MA, Shteiwi M, et al. Knowledge and perceptions about colorectal cancer in Jordan. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015;16:8479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav 2004;31:143–64. 10.1177/1090198104263660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livaudais JC, Kaplan CP, Haas JS, et al. Lifestyle behavior counseling for women patients among a sample of California physicians. J Womens Health 2005;14:485–95. 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez L, Cook EF, Horng MS, et al. Lifestyle modification counseling for hypertensive patients: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2004. Am J Hypertens 2009;22:325–31. 10.1038/ajh.2008.348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Cancer Institute. National Survey of Primary Care Physicians’ Cancer Screening Recommendations and Practices—Colorectal and Lung Cancer Screening Questionnaire 2006. http://healthservices.cancer.gov/surveys/screening_rp/screening_rp_colo_lung_inst.pdf (accessed 14 Jun 2011).

- 26.Battista RN. Adult cancer prevention in primary care: patterns of practice in Quebec. Am J Public Health 1983;73:1036–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simon AE, Forbes LJ, Boniface D, et al. An international measure of awareness and beliefs about cancer: development and testing of the ABC. BMJ Open 2012;2:pii: e001758 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stubbings S, Robb K, Waller J, et al. Development of a measurement tool to assess public awareness of cancer. Br J Cancer 2009;101(Suppl 2):S13–17. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vickers KS, Kircher KJ, Smith MD, et al. Health behavior counseling in primary care: provider-reported rate and confidence. Fam Med 2007;39:730–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank E, Rothenberg R, Lewis C, et al. Correlates of physicians’ prevention-related practices. Findings from the Women Physicians’ Health Study. Arch Fam Med 2000;9:359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heywood A, Firman D, Sanson-Fisher R, et al. Correlates of physician counseling associated with obesity and smoking. Prev Med 1996;25:268–76. 10.1006/pmed.1996.0056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frank E, Segura C, Shen H, et al. Predictors of Canadian physicians’ prevention counseling practices. Can J Public Health 2010;101:390–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moreno-Peral P, Conejo-Ceron S, Fernandez A, et al. Primary care patients’ perspectives of barriers and enablers of primary prevention and health promotion-a meta-ethnographic synthesis. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0125004 10.1371/journal.pone.0125004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arena R, Guazzi M, Lianov L, et al. Healthy lifestyle interventions to combat noncommunicable disease-a novel nonhierarchical connectivity model for key stakeholders: a policy statement from the American Heart Association, European Society of Cardiology, European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, and American College of Preventive Medicine. Eur Heart J 2015;36:2097–109. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The National Strategy for Health Sector in Jordan 2015–2019. https://usaidjordankmportal.com/system/resources/attachments/000/000/311/original/Jordan_National_Health_Sector_Strategy_2015-2019_.pdf?1455799625 (accessed 10 Jan 2017).

- 36.Jordanian Department of Statistics. Jordan Census, 2015. http://census.dos.gov.jo/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2016/02/Census_results_2016.pdf (accessed 3 Apr 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.