Abstract

Objectives

To explore the value of simulation modelling in evaluating the effects of strategies to plan and schedule operating room (OR) resources aimed at reducing time to surgery for non-elective orthopaedic inpatients at a Swedish hospital.

Methods

We applied discrete-event simulation modelling. The model was populated with real world data from a university hospital with a strong focus on reducing waiting time to surgery for patients with hip fracture. The system modelled concerned two patient groups that share the same OR resources: hip-fracture and other non-elective orthopaedic patients in need of surgical treatment. We simulated three scenarios based on the literature and interaction with staff and managers: (1) baseline; (2) reduced turnover time between surgeries by 20 min and (3) one extra OR during the day, Monday to Friday. The outcome variables were waiting time to surgery and the percentage of patients who waited longer than 24 hours for surgery.

Results

The mean waiting time in hours was significantly reduced from 16.2 hours in scenario 1 (baseline) to 13.3 hours in scenario 2 and 13.6 hours in scenario 3 for hip-fracture surgery and from 26.0 hours in baseline to 18.9 hours in scenario 2 and 18.5 hours in scenario 3 for other non-elective patients. The percentage of patients who were treated within 24 hours significantly increased from 86.4% (baseline) to 96.1% (scenario 2) and 95.1% (scenario 3) for hip-fracture patients and from 60.2% (baseline) to 79.8% (scenario 2) and 79.8% (scenario 3) for patients with other non-elective patients.

Conclusions

Healthcare managers who strive to improve the timelines of non-elective orthopaedic surgeries may benefit from using simulation modelling to analyse different strategies to support their decisions. In this specific case, the simulation results showed that the reduction of surgery turnover times could yield the same results as an extra OR.

Keywords: Quality improvement, simulation modelling, operating room, efficiency, orthopaedic surgery

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The simulation experiment was conducted with real world data from a Swedish university hospital.

This is one of the few studies applying simulation modelling to non-elective patient flows.

The simulation study has been carried out in collaboration with hospital staff, and the model was continuously validated.

The outcome variables were limited to waiting time and percentage of patients undergoing surgery within 24 hours.

Unexpected incidents such as patient health status and employee sick leave were not included in the simulation model.

Introduction

The planning and scheduling of activities in the operating room (OR) is a complex task and if carried out inappropriately it can generate unnecessary costs and delays in patient treatment.1 The negative consequences of poorly managed OR resources become evident for patients with hip fracture. Delay to surgery is associated with postoperative complications, prolonged recovery and length of stay, as well as increased mortality.2–5 Despite the positive effects of improvement efforts to reduce waiting time to surgery, the management of OR resources still represents a challenge for the timely delivery of surgical services for this vulnerable patient group.6 7 Waiting time to surgery is consequently still one of the most important performance variables for managing non-elective patient flows in order to prevent unnecessary patient suffering.

One of the challenges in the management of OR resources relates to the management of multiple patient groups that compete for the same resources. A major issue is the trade-off between elective and non-elective cases.8 9 In orthopaedics, non-elective surgical cases have historically been added to the elective schedules which resulted in several problems including disruptions to elective cases and after-hour surgery.10 11 To overcome these problems, hospitals have introduced dedicated day-time orthopaedic ORs for non-elective orthopaedic patients. The use of dedicated orthopaedic ORs is associated with shorter after-hour surgeries for trauma cases and less disruptions to elective schedules,8 12 as well as improved patient care, for example, decreased rates of perioperative mortality, postoperative complications and length of stay.13 The management of non-elective orthopaedic patient flows is however still a challenge as it is often based on ‘ad hoc’ strategies,14 and limited research is applied to non-elective patient flows.1

Non-elective patient flows are different from elective flows because patients can arrive at any time of the day or night, 7 days a week and this creates specific planning requirements. In this respect, there are two main approaches to manage healthcare demand: the unit and the process perspective.15 The unit perspective aims to maximise resource efficiency within a single unit or department whereas the process perspective focuses more on maximising the service level for specific patient groups. These two strategies are not in conflict with one another; in fact, it is claimed that a focus on creating efficient processes indirectly yields a more efficient use of resources.16 The challenge for healthcare organisations lies in developing operational strategies that are aligned with the perspective they chose to prioritise. In an OR, the adoption of a unit perspective would mean focusing on how to increase the usage of OR resources such as surgeons' time and OR-teams; a process perspective would instead emphasise the timeliness of care delivery for specific patient groups.

Simulation modelling is one approach that can help to develop effective operational strategies to plan non-elective surgeries. Stemming from Operations Research, simulation modelling allows for the development and testing of changes before they are implemented in reality.17 18 Simulation modelling can also function as a system analysis tool19 to identify processes in need of improvement in order to reach the goals of the organisation. Simulation modelling applied to OR departments and surgery often focuses on optimising capacity of flows, scheduling and resource utilisation.20–22 However, most research still focuses on elective patients despite the challenge non-elective patients represent when it comes to planning care.1

Rationale and aim of the study

In summary, there is a concrete need to develop operational strategies to plan and schedule OR resources and activities in order to improve the timeliness of care delivery. Simulation modelling can be a valuable approach to evaluate the effects of strategies that, while they may have been tested for elective patient flows, have not been explored for non-elective ones. Thus, in this study we explored the value of simulation modelling to evaluate the effects of strategies to plan and schedule OR resources aimed at reducing the time to surgery for non-elective orthopaedic inpatients. We specifically analysed the effects for patients with hip fracture and other non-elective orthopaedic inpatients who often share the same OR resources.

Method

The applied simulation method was discrete event simulation (DES). DES is often applied to healthcare for patient-flow management, resource allocation and scheduling23 and is the predominant method used in surgical care.24 DES represents the components of a system and their interactions and looks at specific events in a given process (eg, surgical procedure) and their chronological sequence.25 The state of the system observed and simulated is updated as each event takes place making DES a suitable tool to evaluate and improve system performance.26 The effects of OR planning and scheduling strategies were measured by waiting time to surgery and the percentage of patients undergoing surgery within 24 hours, a common improvement target for patients with hip fracture.7 The study has been granted ethical approval by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm (ref no. 2009/1657-31).

Setting

This study was carried out at a Swedish university hospital with a catchment area of ∼450 000 inhabitants. The 52-bed orthopaedic department has an annual admittance of ∼3700 patients, mainly for non-elective care. Patients with hip fractures constitute the major non-elective group with an annual surgical rate of ∼600 fractures. In Sweden, the National Board of Health and Welfare recommends that patients with hip fracture receive surgical treatment within 24 hours from admission.27 When this study was conducted, the County Council requirement was that 80% of patients with a hip fracture should have surgery within 24 hours from admission. At the hospital, efforts have been made in recent years to reach this goal. Despite the improvement observed, variability in the process still exists.7 28 Staff and managers at the hospital expressed that further improvement could be achieved by improving the process at the OR, which subsequently became the focus of the simulation model.

There were 12 ORs at the current OR department and 5 (6 on Mondays) were dedicated for orthopaedic surgeries and the remainder were dedicated for general surgical and urological cases. Two ORs were dedicated during day shift to serve non-elective orthopaedic surgeries and one OR during night shift. At weekends there was one OR dedicated during the day and night shift. In 2014, a total of 10 574 surgeries were performed at the operating department; of these 4512 were orthopaedic surgeries, 2230 non-elective and 2282 elective surgeries. Normally, according to a regional guideline, multitrauma cases were treated at another hospital in the County Council and therefore very few underwent surgery at this hospital. Non-elective orthopaedic patients arrive 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The patients arrive at ED and then pass several units preoperatively; different kind of assessments and procedures are carried out in order to prepare patients for surgery. An anaesthesiologist makes the final decision and decides when the patient is ready for surgery.

Simulation model

The system modelled used real patient data from 2013 and concerned hip-fracture patients and other non-elective patients arriving for orthopaedic surgery. In the model, we only considered patients who required surgery and hence were assumed to have already been assessed for surgical needs. However, in reality the time which elapses before surgery actually is scheduled, varies greatly, depending on patient condition, as some patients require other investigations and/or treatments prior to surgery, for example, stabilisation for several days. This variation was not added to the model, as it was not considered to be a hospital-related delay to surgery. Nonetheless, we did add a short time to each of the modelled patients waiting to undergo surgery as they were not very likely to be scheduled for surgery immediately after being assessed by an orthopaedic surgeon. This time was computed as the mean for the 20 patients with the shortest waiting time, for example, the patients who computed the fastest elapsed time from the time of admission to the hospital to the time the patient entered the OR.

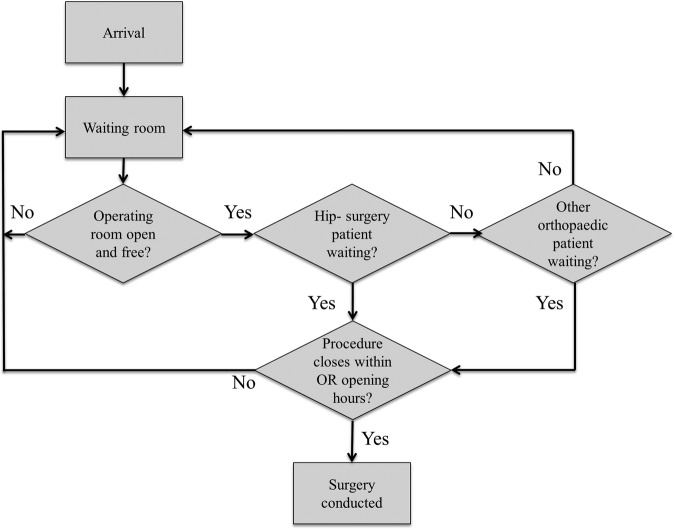

Furthermore, we divided the patients into two separate groups (queues), one queue for hip-fracture surgery and one for the remaining orthopaedic non-elective surgical cases (figure 1). These two patient groups shared the same OR resources. Given the low number of multitrauma cases, a hip-surgery patient in general was considered to have a higher priority and therefore the hip-surgery queue was given higher priority than the other orthopaedic surgery queue. Both queues were modelled on the first-come-first-served processing rule. The number of ORs was dynamically modelled according to the authentic number of ORs open for a specific day in the week. In the same way, we modelled the opening hours of the ORs according to how long the specific OR was open for a specific weekday in reality.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the simulation model.

First, the patients arrive according to an arrival process α(x) and are placed in one of the two queues according to the described rules above (figure 1). The process α(x) was assumed to be Poisson, that is, having exponential arrival intervals with a calculated arrival mean derived for each hour during the day and night.29 If one of the ORs was available, that is, not occupied with another surgical procedure or was closed, the simulation model searched the queues for a patient ready to undergo surgery according to a prioritisation scheme (described in the experiment). If a patient's estimated surgical procedure time exceeded the remaining OR opening hours, the patient was forced to wait (remain in the queue) until the next day, and instead the next patient in line was processed. In the model, a distinction was made between the simulated planned surgical procedure time and the simulated actual surgical procedure time in order to capture the difference in what is known to the staff before the surgery starts and what really happens in terms of surgery duration. The simulation of the planned surgical procedure time was based on the mean procedure time for a particular procedure, whereas the simulation of the actual surgical procedure time was drawn from a log-normal distribution with specified mean and variance30 and was unknown before the simulated surgery started. This means that the opening hours of an OR may be exceeded and more time will be required in order to complete the surgical procedure already underway. After the surgery was completed, the patient was sent out of the system.

The data obtained from the hospital were preprocessed by use of Python script language, and the simulation model was developed in Java.

Simulation experiment with scenarios

The simulation experiment was set up to evaluate the effects of three scenarios on the mean waiting time and the percentage of patients waiting longer than 24 hours for surgery. These two variables were measured for hip-fracture patients and other non-elective orthopaedic patients. The experiment was conducted by simulating three scenarios that were developed based on the literature and through interactions with staff and managers at the hospital. The first scenario represented the planning and scheduling of the non-elective orthopaedic cases using current practice (baseline scenario), the second scenario represented current practice but the turnover between surgeries was reduced by 20 min and the third scenario represented current practice with the exception of one extra OR in day time (Monday to Friday). Scenarios 2 and 3 represent potential areas for improvements discussed at the involved departments, that is, the operating department, the orthopaedic department and the anaesthesia and intensive care department. Each scenario was simulated 10 times using different random seeds.

Non-elective orthopaedic data from 2013 extracted from the hospital OR system was used as input to the simulation model. After visual inspection, incomplete case records were omitted from the data set. In table 1, the various parameters used for the simulation are listed. The prioritisation parameter at the bottom of the table describes the logical flow of how the priority between hip-fracture patients and other non-elective orthopaedic patients was simulated.

Table 1.

Description of parameters used in the simulation model

| Parameter | Value in baseline scenario | Distribution type | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR opening | 8:00 | Personal communication with staff | |

| OR closing (day time) | 16:00 | Personal communication with staff | |

| OR closing (Friday) | 14:00 | Personal communication with staff | |

| OR closing (night shift) | 21:00 | Personal communication with staff | |

| Number of ORs open per week | 2 OR day time and 1 OR evening shift. Weekends: 1 OR daytime and 1 OR evening shift | Expert opinion | |

| Patient arrival | Poisson | OR scheduling system | |

| Time from Emergency Department to OR | 5 hours for hip-fracture patients and 3.5 hours for other non-elective patients | Patient records | |

| Simulated actual surgical procedure time | All patient time included. Included surgical preparation as cleaning and anaesthesia, ie, preprocedure and postprocedure | Lognormal | OR scheduling system |

| Simulated planned surgical procedure time | Mean (all patient time included) | OR scheduling system | |

| Turnover time | The turnover time including postprocedure and preprocedure of two subsequent surgical cases was estimated to be 60–90 min | Expert opinion | |

| Prioritisation (hip-fracture patients vs other non-elective patients) | (a) If hip <24 h and other <36 h then hip priority | Expert opinion | |

| (b) If hip <24 h and other >36 h then other priority | |||

| (c) If hip >24 h and other >36 h then hip priority | |||

| (d) If other >36 h and postponed then other priority |

The turnover time including post-procedure and preprocedure of two subsequent surgical cases was estimated at the included hospital to be 60–90 min depending on the surgical cases. A reduction of 20 min turnover time altogether was deemed reasonable and well-motivated by the staff.

To ensure that the simulation model was a representation of, or as close to, the real orthopaedic surgical system as possible, the model was validated continuously throughout the study, that is, the baseline scenario was validated. Several meetings with orthopaedic surgeons, anaesthesiologists, OR nurses, OR coordinators and registered nurse anaesthetists were carried out along with intermittent observations at the operating department. When comparing the baseline scenario with real world data, the simulated data showed slightly better results in terms of waiting time to surgery. This difference can be explained by design decisions in the simulation model that were taken due to limited data availability. For instance, we lacked data that could explain the variation in time from arrival at the Emergency Department to the time the patients are cleared for surgery. This variation could be due to the need for preoperative investigations for patients, which could delay the surgery. Since this delay was not deemed relevant for this study, we decided to build the simulation model based on the mean of the 20 fastest patients; the mean time between arrival at the Emergency Department and the start of surgery for these patients was 5 hours.

Statistical analysis

The arrival of patients was modelled by using Poisson process, and the uncertainty of surgical duration was modelled by log-normal distribution. A parametric approach using 95% CIs for waiting time in hours and percentage of cases treated within 24 hours was used to compare the three scenarios. Box-plot was used to graphically represent the data.

Results

The reduction of the turnover time by 20 min (scenario 2) and the introduction of an extra OR during day time (scenario 3) contributed to a significant, as indicated by the lack of overlapping between the CIs, reduction in waiting time to surgery for both patient groups, compared to scenario 1 (baseline). For hip-fracture patients, the mean waiting time decreased from 16.2 hours in scenario 1 to 13.3 hours in scenario 2 and 13.6 hours in scenario 3. The corresponding change in the mean waiting time for the other non-elective patients was a reduction from 26.3 to 18.9 hours and from 26.3 to 18.5 hours, in scenarios 2 and 3, respectively (table 2).

Table 2.

Performance of the three simulated scenarios

| Scenario 1 (baseline) | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean waiting time in hours with 95% CI | |||

| Hip-fracture patients | 16.2 hours (95% CI 15.4 to 17.1) | 13.3 hours (95% CI 13.1 to 13.5) | 13.6 hours (95% CI 13.4 to 13.9) |

| Other non-elective patients | 26.3 hours (95% CI 24.3 to 27.6) | 18.9 hours (95% CI 18.1 to 19.7) | 18.5 hours (95% CI 18.1 to 19.0) |

| Percentage of patients treated within 24 hours with 95% CI | |||

| Hip-fracture patients | 86.4% (95% CI, 83.5% to 89.3%) | 96.1% (95% CI 95.5 to 96.7) | 95.1% (95% CI, 94.0% to 96.1%) |

| Other non-elective patients | 60.2% (95% CI, 56.9% to 63.7%) | 79.8% (95% CI 77.6% to 82.1%) | 79.8% (95% CI, 78.5% to 81.1%) |

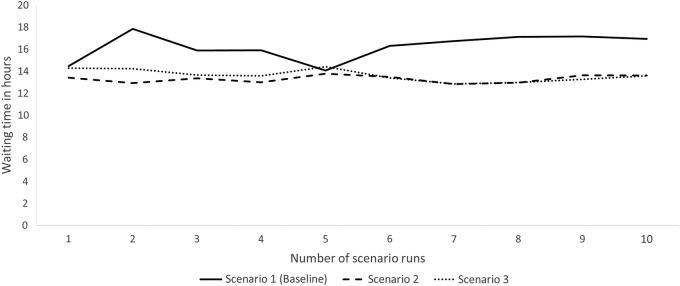

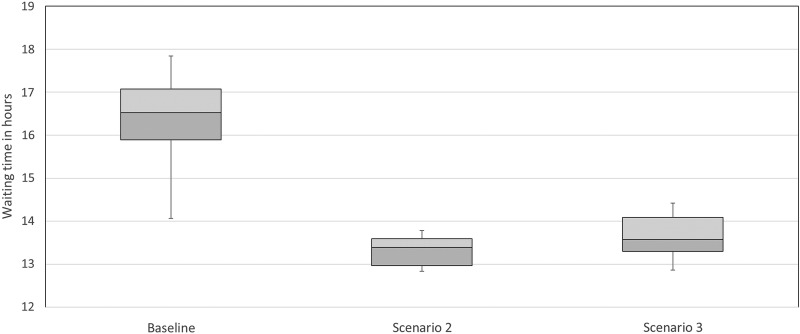

The level of improvement achieved in scenario 2 and, compared with baseline, were similar for both scenarios. Scenarios 2 and 3 showed better results for all simulation runs compared with baseline except for one run in scenario 3 (figure 2). Figure 3 shows the same results, viewed as box plot.

Figure 2.

Mean waiting time in hours for hip-fracture patients monitored for each scenario.

Figure 3.

Box plots of the waiting time for hip-fracture patients for each of the three scenarios.

Significant results were also observed for the percentage of patients who waited longer than 24 hours for surgical treatment, that is, similar levels of improvement were identified for scenarios 2 and 3 compared with baseline (table 2).

The percentage of hip-fracture patients who underwent surgery within 24 hours was simulated at 86.4% in the baseline scenario. In scenarios 2 and 3, however, simulated results showed that 96.1% and 95.1%, respectively, of the hip-fracture patients underwent surgery within 24 hours. Furthermore, in the other non-elective patient group a significant increase in percentage of patients who underwent surgery within 24 hours was simulated in scenarios 2 (79.8%) and 3 (79.8%) compared with baseline (60.2%) (table 2).

Discussion

In this paper, we investigated how simulation modelling can be used to analyse different operational strategies to reduce waiting time to surgery for patients with hip fracture and other non-elective orthopaedic patients. In this specific hospital, we found that a reduction in turnover time by 20 min in an OR can yield the same level of improvement as adding an extra OR during daytime.

This study contributes to the literature on how to improve the planning and scheduling of non-elective patients flow using simulation, a field in which empirical research is limited.1 The main contribution, in terms of simulation results, lies in showing how, in a hospital setting where non-elective orthopaedic surgeries are performed in dedicated ORs, the reduction of the turnover time may have the same effect as adding an extra OR. The latter strategy may yield higher costs as it would require investing in additional human resources, physical space and associated equipment. The experimental results can be explained by the pattern in patient arrival rate. An increase in OR resources during the daytime has limited effect on waiting time since non-elective patients typically arrive 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, although the arrival rate is likely to be less frequent during the night. The benefits of reduced turnover time31 32 for elective patients have been described earlier; this study clearly shows that such strategy is valuable to improve process efficiency while ensuring efficient resource usage at the OR also in the context of non-elective patients flows.

This study does not directly provide answers to how turnover time can be reduced, but the literature suggests parallel processing as a viable method.31 32 Friedman and colleagues found that turnover time could be reduced through parallel processing in ORs designed for outpatient inguinal hernia repair. Parallel processing was achieved without additional resources by having the operating team of surgeon, nurses and scrub technicians working on two patients simultaneously. The maintenance of a constant team throughout the entire day also contributed to the observed improvement.32 Another approach to parallel processing is to start the preprocedure of the upcoming surgical case before the postprocedure of the current surgical case is completed. This approach however requires extra resources in terms of surgical teams. Holmgren and Persson present an optimisation model that sequences surgical cases in such a way that parallel processes are scheduled for many ORs subject to a limited number of surgical teams.31 Future studies can investigate how parallel processing, as well as other strategies, can be used to improve the efficiency of non-elective surgical flows.

As in our study, the specific operational strategies adopted should be tailored to the specific context of application and developed in collaboration with managers and professionals. While the results obtained in this study may be influenced by the setting of application, this study clearly shows the value of using simulation modelling when analysing management strategies that involve stochastic processes, such as patient arrival, case-mix and procedure duration. In the case organisation, the results of the simulation analysis were the starting point for two new research and development projects that aim to investigate how parallel processing can be implemented to increase patient throughput in the OR and how a 6-hour workday in the OR can be implemented.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The main strengths of this study are that it was based on real world data from a hospital and the development of the model was grounded on the real needs of hospital staff and managers who had worked for several years to reduce waiting time to surgery for patients with hip fracture.7 The model itself was developed and validated in collaboration with hospital staff and managers, a process that is of key importance.33 34

The main limitations of the study are twofold. Firstly, the simulation model does not take into consideration unexpected incidents such as sudden change in patient health status (ie, not being well enough to undergo a surgical procedure) and the sick leave of employees. While one may expect these variables to influence the waiting time to surgery, we sought to overcome this limitation by considering the relative performance, that is, the difference in results between scenarios. In other words, we would expect a sudden change in patient health status and staff sick leave to have a similar effect on all scenarios and hence not crucial to this study. Second, the outcome variables included were limited to waiting time and percentage of patients undergoing surgery within 24 hours. A more comprehensive evaluation of performance, including measures of cost, usage rates of the OR and percentage of cancelled surgeries, can be a way forward to develop better strategies for the management of non-elective patient flows.

Conclusions

This study shows that simulation modelling can be used to understand system performance in the context of non-elective care. In the hospital studied, a reduction of 20 min in OR turnover time yielded almost the same effect in patient waiting time as the addition of one extra OR during the daytime. Future research can investigate how this reduction in turnover time can be accomplished for non-elective patient flows for instance through OR and staff scheduling. The economic effects of these strategies can also be explored in future research.

We suggest that simulation modelling can become an integral part of healthcare development to investigate improvement strategies with healthcare managers and professionals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Åsa af Jochnick and Sara Saltin for their help with collection of quantitative data, as well as staff and managers at the Danderyd Hospital for their contribution to the development of the model.

Footnotes

Contributors: MP, HH-F, MU, OGS, AS, PK-P and PM designed the study. MP, MU, PK-P, OGS and PM collected the data. All authors contributed to the development of the model, and MP conducted the implementation of the model and result analysis. MP, HH-F, MU and PM drafted the manuscript. OGS, AS, and PKP read and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript and are accountable for all parts of the work.

Funding: The authors thank the Regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet for financial support.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm (ref no. 2009/1657-31).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Excel file with the input and output data from the simulation model (ie, key activities carried out in the care process and the time when they were carried out) is available on request by emailing marie.persson@bth.se or pamela.mazzocato@ki.se

References

- 1.Cardoen B, Demeulemeester E, Belien J. Operating room planning and scheduling: a literature review. Eur J Oper Res 2010;201:921–32. 10.1016/j.ejor.2009.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trpeski S, Kaftandziev I, Kjaev A. The effects of time-to-surgery on mortality in elderly patients following hip fractures. Contribution to Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Section of Biological and Medical Sciences 2013;34:116–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daugaard CL, Jorgensen HL, Riis T, et al. Is mortality after hip fracture associated with surgical delay or admission during weekends and public holidays? A retrospective study of 38,020 patients. Acta Ortho 2012;83:609–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moja L, Piatti A, Pecoraro V, et al. Timing matters in hip fracture surgery: patients operated within 48 hours have better outcomes. A meta-analysis and meta-regression of over 190,000 patients. PLoS One 2012;7:e46175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simunovic N, Devereaux PJ, Sprague S, et al. Effect of early surgery after hip fracture on mortality and complications: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2010;182:1609–16. 10.1503/cmaj.092220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hommel A, Ulander K, Bjorkelund KB, et al. Influence of optimised treatment of people with hip fracture on time to operation, length of hospital stay, reoperations and mortality within 1 year. Injury 2008;39:1164–4. 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazzocato P, Unbeck M, Elg M, et al. Unpacking the key components of a programme to improve the timeliness of hip-fracture care: a mixed-methods case study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2015;23:93 10.1186/s13049-015-0171-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heng M, Wright JG. Dedicated operating room for emergency surgery improves access and efficiency. Can J Surg 2013;56:167–74 10.1503/cjs.019711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zonderland ME, Boucherie RJ, Litvak N, et al. Planning and scheduling of semi-urgent surgeries. Health Care Manag Sci 2010;13:256–67 10.1007/s10729-010-9127-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wixted JJ, Reed M, Eskander MS, et al. The effect of an orthopedic trauma room on after-hours surgery at a level one trauma center. J Orthop Trauma 2008;22:234–6 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31816c748b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elder GM, Harvey EJ, Vaidya R, et al. The effectiveness of orthopaedic trauma theatres in decreasing morbidity and mortality: a study of 701 displaced subcapital hip fractures in two trauma centres. Injury 2005;36:1060–6. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhattacharyya T, Vrahas MS, Morrison SM, et al. The value of the dedicated orthopaedic trauma operating room. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2006;60:1336–41 10.1097/01.ta.0000220428.91423.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts TT, Vanushkina M, Khasnavis S, et al. Dedicated orthopaedic operating rooms: beneficial to patients and providers alike. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:e18–23 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox MR, Cook L, Dobson J, et al. Acute Surgical Unit: a new model of care. ANZ J Surg 2010;80:419–24 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vissers J, Beech R, Health operations management: patient flow logistics in health care. Routledge health management series London: Routledge, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Modig N, Åhlström PR. This is lean: resolving the efficiency paradox. Stockholm: Rheologica publishing Bulls Graphics AB, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slovensky DJ, Morin B. Learning through simulation: the next dimension in quality improvement. Qual Manag Health Care 1997;5:72 10.1097/00019514-199705030-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colin R. Real World Research: a resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. Victoria: Blackwell Publishing, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid PP, Compton WD, Grossman JH, et al. Building a better delivery system: a new engineering/health care partnership. Washington: (DC: ): National Academies Press, 2005:35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dexter F, Wachtel RE, Epstein RH, et al. Analysis of operating room allocations to optimize scheduling of specialty rotations for anesthesia trainees. Anesth Analg 2010;111:520–4. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e2fe5b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Essen JT, Hurink JL, Hartholt W, et al. Decision support system for the operating room rescheduling problem. Health Care Manag Sci 2012;15:355–72 10.1007/s10729-012-9202-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Houdenhoven M, van Oostrum JM, Hans EW, et al. Improving operating room efficiency by applying bin-packing and portfolio techniques to surgical case scheduling. Anesth Analg 2007;105:707–14. 10.1213/01.ane.0000277492.90805.0f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Günal M, Pidd M. Discrete event simulation for performance modelling in health care: a review of the literature. J. Simulat 2010;4:42–51. 10.1057/jos.2009.25 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobolev BG, Sanchez V, Vasilakis C. Systematic review of the use of computer simulation modeling of patient flow in surgical care. J Med Syst 2011;35:1–16. 10.1007/s10916-009-9336-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banks J. Handbook of simulation: principles, methodology, advances, applications, and practice. New York: Wiley Publications, 1998:659. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mustafee N, Katsaliaki K, Taylor SJ. Profiling literature in healthcare simulation. Simulation 2010;86(8-9):543–58. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Socialstyrelsen. Guidelines for care and treatment of hip fractures [In Swedish: Socialstyrelsens riktlinjer för vård och behandling av höftfrakturer] Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eriksson M, Kelly-Petterson P, Stark A, et al. “Straight to bed” for hip-fracture patients. Injury 2012;43:2126–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Law AM, Kelton WD. Simulation modeling and analysis. 5th edn New York: McGraw Hill Education, 2014:389–93. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strum DP, May JH, Vargas LG. Modeling the Uncertainty of surgical procedure times comparison of log-normal and normal models. J Am Soc Anesthesiol 2000;92:1160–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holmgren J, Persson M. An optimization model for sequence dependent parallel operating room planning. Second international conference on Health Care Systems Engineering; Lyon, France, 2015. Springer Proceedings in Mathematics & Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedman DM, Sokal SM, Chang Y, et al. Increasing operating room efficiency through parallel processing. Ann Surg 2006;243:10–4. 10.1097/01.sla.0000193600.97748.b1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aharonson-Daniel L, Paul RJ, Hedley AJ. Management of queues in out-patient departments: the use of computer simulation. J Manag Med 1996;10:50–8. 10.1108/02689239610153212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cochran JK, Bharti A. Stochastic bed balancing of an obstetrics hospital. Health Care Manag Sci 2006;9:31–45. 10.1007/s10729-006-6278-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.