Abstract

Objective

To examine geographic variation in motor vehicle crash (MVC)-related pediatric mortality and identify state-level predictors of mortality.

Study design

Using the 2010–2014 Fatality Analysis Reporting System, we identified passengers <15y involved in fatal MVCs, defined as crashes on U.S. public roads with ≥1 death (adult or pediatric) within 30d. We assessed passenger, driver, vehicle, crash, and state policy characteristics as factors potentially associated with MVC-related pediatric mortality. Our outcomes were age-adjusted, MVC-related mortality rate per 100,000 children (AAMR) and percentage of children that died of those in fatal MVCs. Unit of analysis was U.S. state. We used multivariable linear regression to define state characteristics associated with higher levels of each outcome.

Results

Of 18,116 children in fatal MVCs, 15.9% died. AAMR varied from 0.25 in Massachusetts to 3.23 in Mississippi (mean national rate=0.94). Predictors of greater AAMR included greater percentage of children unrestrained/inappropriately restrained (p<0.001) and greater percentage of crashes on rural roads (p=0.016). Additionally, greater percentages of children died in states without red light camera legislation (p<0.001). For 10% absolute improvement in appropriate child restraint use nationally, our risk-adjusted model predicted >1,100 pediatric deaths averted over 5y.

Conclusions

MVC-related pediatric mortality varied by state and was associated with restraint nonuse/misuse, rural roads, vehicle type, and red light camera policy. Revising state regulations and improving enforcement around these factors may prevent substantial pediatric mortality.

Keywords: motor vehicle crashes, pediatric mortality, Fatality Analysis Reporting System, child restraints

Unintentional injury is the leading cause of pediatric death in the U.S. and motor vehicle crashes (MVCs) are the most common cause of injury (1). Over the past twenty years, many studies have analyzed individual, person-level data, and identified several risk factors for MVC-related mortality in children, including nonuse of restraints (2–5), front seat position (4–6), alcohol-impaired drivers (7–10), younger driver age (9), high speed roads (9,11), and rural roads (12,13). In 2011, informed by this research, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published specific guidelines regarding the strongest and most modifiable predictors – child restraints and seat position (14). Prior guidelines have also addressed alcohol use by drivers (15). Although these recommendations have been implemented in part by some states, no state has implemented them fully (16).

Further, no prior study has examined trends in MVC-related pediatric mortality across states and factors associated with geographic variation at the state or regional level. This geographic variation is important because laws regarding child traffic safety remain within the state domain (17). It is vital, therefore, to understand how state-level regulations and their implementation and enforcement impact MVC-related pediatric mortality. We hypothesized that state-level policies related to child traffic safety would be associated with state mortality rates. Our objectives were to assess for variation in MVC-related pediatric mortality by state and region, and to explain the sources of such variation.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of data to inform state-level policy. We compiled our analytic dataset from multiple sources. The primary source was the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS), a nationwide census providing publicly-available data on fatalities associated with MVCs. The FARS includes all fatal crashes in the U.S., defined as crashes that occur on a public road and result in ≥1 death (adult or pediatric) within 30 days. Data collection is supervised by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and data are compiled from various documents in each state, including police accident reports, death certificates, state vehicle registration files, medical examiner reports, state driver licensing files, state highway department data, emergency medical service reports, and vital statistics. Data are subjected to checks for acceptable range values and consistency, as well as quality checks (18). We obtained annual U.S. population size estimates by age, state, and region, and the percentage of households with a vehicle from the U.S. Census (19,20). We compiled state-level policies relevant to child traffic safety from the Governors Highway Safety Association, the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (U.S. non-profit research organization funded by auto insurers), and the medical and legal literature (17,21,22). We assembled data from 2010–2014 to coincide with the most recently available FARS data.

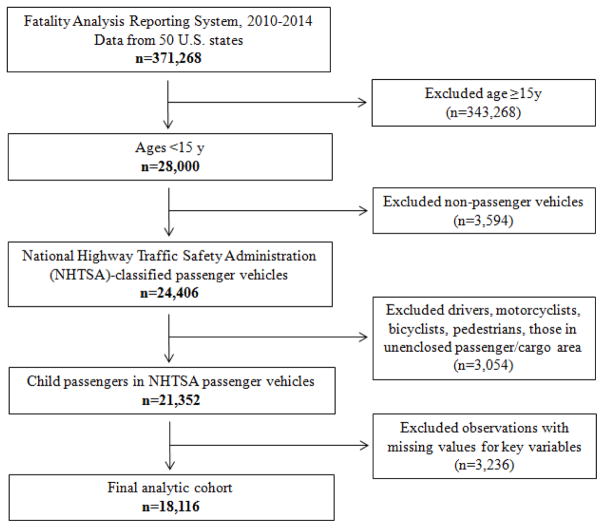

We defined a study cohort using person-level data from children <15y riding in a passenger vehicle involved in a fatal crash (Figure 1; available at www.jpeds.com). Passenger vehicles are defined by the NHTSA as cars, sport utility vehicles (SUVs), vans, and pickup trucks with a gross weight ≤10,000 pounds (18,23). We excluded children classified as drivers, passengers on a motorcycle/bicycle, or pedestrians, as well as children in an unenclosed passenger or cargo area, the vehicle exterior, or a trailing unit. We made these exclusions in order to focus on state-level policies, such as guidelines for restraint use, that would apply to all children in our study population. We used a complete case analysis approach for the individual observations, excluding observations with missing data for key variables from all analyses. Data were missing for fewer than 5% of observations for all variables except for restraint use/misuse, which was missing for 6% of observations.

Figure 1.

Study population

Our primary outcome was state-based, age-adjusted, mean MVC-related pediatric mortality per 100,000 children (AAMR) over 2010–2014, defined as 30-day mortality from the day of the crash. We calculated age-adjusted mortality rates per 100,000 children for each state using census information on the pediatric population for five age groups (0–2y, 3–5y, 6–8y, 9–12y, 13–14y) within each state, standardized by the population within these age groups in the U.S. overall. Age groups were selected based upon recommended seating within a motor vehicle at different ages. We then obtained mean mortality rates by averaging the annual rates over the 5-year period 2010–2014. Due to state-level differences in vehicle ownership and the amount of time children may spend as passengers in a vehicle, we considered a secondary outcome, the percentage of children that died of those involved in a fatal crash (20). We calculated both outcomes by region (Midwest, Northeast, South, West) and nationally.

To explain state-level variation in mortality rates, we compiled an extensive list of variables potentially related to MVC-related pediatric mortality, including passenger, driver, vehicle, crash, and state policy characteristics (Appendix; available at www.jpeds.com). Most person-, vehicle-, and crash-level variables were used as defined in the FARS. Of note, the FARS dataset reported type of restraint and any indication of misuse of the restraint system. Additionally, we defined several variables. Child passengers riding in the front seat were deemed appropriate or inappropriate based upon the AAP guidelines that children <13y should ride in the rear seats of vehicles (14). Vehicle type was categorized as car, SUV, van/minivan, pick-up truck, and vehicle larger than a pick-up truck. Crashes occurring over the weekend were defined as those between Friday 5pm and Monday 6am. Crashes occurring during the day were defined as those between 6am and 6pm (24). We modeled state speed and red light camera policy using dummy variables (state legislation present versus not present, prohibited versus not prohibited, limited versus not limited, permitted versus not permitted) as well as by current use patterns (in use versus not in use). We categorized the variables into four main topical groups: 1) restraints or seat position (2,3,6,9,23,25); 2) speeding or traffic restrictions (8,9,11,23); 3) driving under the influence of alcohol (7–10); and 4) availability of pediatric trauma centers and trauma systems (26–31).

Statistical analyses

We performed an ecological study, using U.S. state as our unit of analysis. We summarized person-level data for all children meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria to obtain mean state-level values for each variable. We used multivariable linear regression to identify state characteristics associated with greater AAMR or percentage of children who die when involved in a fatal crash. For each outcome, we employed step-wise model-building; this approach allowed us to obtain the most parsimonious model that represented the geographic variation of MVC-related pediatric mortality without concern for overfitting the data. We included all identified variables of interest in the initial model-building process for each outcome.

We first assessed Pearson correlation coefficients between each outcome and each potential continuous predictor. We identified continuous variables that met two criteria: 1) correlation with the outcome, expressed by Pearson correlation >0.3 or <−0.3 and 2) p-value ≤0.1. Variables that met these criteria were included in a correlation matrix; we removed highly collinear variables (bivariate Pearson correlation ≥0.6), keeping the variable with the highest Pearson correlation with the outcome in the model in each instance of collinearity. For categorical and binary variables, we used analysis of variance and t-tests, respectively, to identify variables with an association with the outcome with a p-value ≤ 0.1. We included all selected variables in an initial model, using a process of step-wise selection to remove non-significant variables (p>0.1) until we obtained a final model for each outcome. In all models for the primary outcome, the percentage of households with a vehicle was included regardless of significance due to its likelihood to be a confounder.

Analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC). A two-sided p-value of 0.05 was used to determine significance in the final models. The Partners Human Research Committee approved this research.

Results

After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we established a cohort of 18,116 children (Figure 1). This national cohort had a mean age of 6.9y (SD 4.4) and was 51% male. The majority of children involved in a fatal crash lived in the South (52%), with 21% in the West, 19% in the Midwest, and 7.5% in the Northeast. Of the 18,116 children involved in a fatal crash, 2,885 died (15.9%) within 30 days, of which 1,424 died at the scene of the MVC. This corresponded to an overall AAMR for the U.S. of 0.94 per 100,000 children.

Crash characteristics by state are shown in Table I. On average across all states, 20% of children involved in a fatal crash were unrestrained or inappropriately restrained at the time of the crash, 13% were inappropriately seated in the front seat, and nearly 9% of drivers carrying a child passenger were under the influence of alcohol. Crashes were most likely to occur on state highways (35%) and on roads classified as rural by the Federal Highway Authority (62%) (18). Vehicles involved in fatal crashes had been on the road for an average of 9.4y (SD 1.1). Consistent with the nature of the FARS, the vast majority of vehicles sustained disabling damage. Policy characteristics within the four identified domains varied considerably by state (Table I).

Table 1.

Summary of states’ crash characteristics for fatal crashes involving a child passenger, 2010–2014 and state policy characteristics relevant to child motor vehicle safety

| Factor | |

|---|---|

| State crash characteristics, mean (SD) | |

| Driver age (years) | 36 (1.9) |

| Driver under the influence of alcohol (%) | 8.9 (4.4) |

| Child inappropriately seated in front seat (%) | 13 (3.2) |

| Child unrestrained or inappropriately restrained (%) | 20 (8.4) |

| Road location (%) | |

| Interstate | 16 (8.3) |

| U.S. highway | 20 (11) |

| State highway | 35 (16) |

| County road | 12 (11) |

| Local street | 15 (11) |

| Rural road (%)* | 62 (21) |

| Vehicle type (%) | |

| Car | 42 (8.9) |

| Van/minivan | 14 (6.8) |

| Sports utility vehicle | 24 (6.0) |

| Pickup truck | 17 (7.2) |

| Vehicle years on the road (years) | 9.4 (1.1) |

| Speed limit at crash site (miles per hour) (%) | |

| 5 to 20 | 0.5 (1.0) |

| 25 to 40 | 22 (12) |

| 45 to 60 | 52 (17) |

| 65 to 80 | 24 (18) |

| None | 0.8 (2.5) |

| Crash during the day (6am – 6pm) (%) | 64 (7.2) |

| Crash over the weekend† (%) | 46 (5.9) |

| Disabling damage to vehicle (%) | 84 (11) |

| Rollover mechanism (%) | 24 (11) |

| Child ejected from vehicle (%) | 8.0 (5.0) |

| Child extricated from vehicle (%) | 9.0 (6.6) |

| State policy characteristics | |

| Restraints or seat position | |

| Law states a preference for seating children in the rear seat, % of states | 34 |

| Allows primary enforcement of seat belt laws for children, % of states | 68 |

| Requires a rear-facing seat for children <1y or <20 pounds, % of states | 30 |

| Maximum fine for first offense violating state child restraint laws ($), mean (SD) | 67 (70) |

| Maximum fine for first offense violating state seat belt laws ($), mean (SD) | 34 (33) |

| Speeding or traffic restrictions | |

| Legislation in place regarding speed camera use, % of states | 50 |

| Legislation in place regarding red light camera use, % of states | 34 |

| Maximum state speed limit (miles per hour), mean (SD) | 71 (5.5) |

| Driving under the influence of alcohol | |

| Administrative license suspension on first offense/refusal to submit to a chemical test, % of states | 90 |

| Open container law meeting federal requirements,‡ % of states | 80 |

| Repeat offender law meeting federal requirements,‡ % of states | 72 |

| Mandatory vehicle or license plate sanctions, % of states | 60 |

| Availability of pediatric trauma centers/trauma systems | |

| Funded state trauma system, % of states | 58 |

| State has ≥1 level 1 or level 2 pediatric trauma center, % of states | 64 |

| Total level 1 and level 2 pediatric trauma centers per 100,000 children, mean (SD) | 0.18 (0.20) |

The distinction between rural and urban roads was as defined by the Federal Highway Administration (18).

Weekend was defined as Friday 5pm to Monday 6am.

Federal law specifies minimum requirements for state open container and repeat offender laws. If these are not met, National Highway System, Surface Transportation Program, and Interstate Maintenance funds are instead transferred into each state’s State and Community Highway Safety Grant Program (Section 402) (49,50).

There was substantial state-level variation of the key predictors selected through our model-building process (Table II). The percentage of children involved in a fatal crash who were unrestrained or inappropriately restrained varied from 2% in New Hampshire to 38% in Mississippi. Characteristics of the crashes also varied: the percentage of those that occurred on a rural road varied from 17% in Massachusetts and Rhode Island to 100% in Maine and Vermont; the percentage of those that occurred on state highways varied from 11% in Iowa to 84% in Hawaii; and the percentage of those that occurred on a road with a speed limit 65 to 80 miles per hour (mph) varied from 0% in Hawaii, Maine, and Rhode Island to 80% in Wyoming (Table II).

Table 2.

State variation of key predictors for fatal crashes involving a child passenger, 2010–2014

| State | No restraint use/misuse (%) | On rural road (%) | Vehicle type van (%) | On state highway (%) | Speed limit 65–80 mph (%) | Red light camera policy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwest | 21 | 71 | 20 | 27 | 25 | -- |

| Illinois | 22 | 45 | 21 | 29 | 11 | Limited |

| Indiana | 19 | 72 | 27 | 29 | 15 | No law |

| Iowa | 24 | 71 | 33 | 11 | 20 | No law |

| Kansas | 25 | 77 | 15 | 14 | 43 | No law |

| Michigan | 9 | 54 | 21 | 24 | 12 | No law |

| Minnesota | 21 | 74 | 19 | 28 | 17 | No law |

| Missouri | 20 | 62 | 13 | 49 | 19 | Limited |

| Nebraska | 34 | 86 | 15 | 15 | 41 | No law |

| North Dakota | 25 | 93 | 22 | 24 | 47 | No law |

| Ohio | 14 | 62 | 17 | 34 | 9 | Limited |

| South Dakota | 30 | 87 | 13 | 28 | 61 | No law |

| Wisconsin | 10 | 68 | 25 | 41 | 10 | Prohibited |

| Northeast | 11 | 50 | 18 | 44 | 11 | -- |

| Connecticut | 10 | 20 | 11 | 39 | 15 | No law |

| Maine | 5 | 100 | 31 | 50 | 0 | Prohibited |

| Massachusetts | 13 | 17 | 25 | 36 | 23 | No law |

| New Hampshire | 2 | 50 | 15 | 53 | 10 | Prohibited |

| New Jersey | 13 | 18 | 20 | 26 | 14 | Prohibited |

| New York | 11 | 72 | 21 | 33 | 14 | Limited |

| Pennsylvania | 15 | 59 | 20 | 58 | 7 | Limited |

| Rhode Island | 17 | 17 | 6 | 56 | 0 | Permitted |

| Vermont | 18 | 100 | 11 | 46 | 14 | No law |

| South | 23 | 63 | 11 | 37 | 20 | -- |

| Alabama | 33 | 64 | 9 | 26 | 23 | Limited |

| Arkansas | 17 | 83 | 9 | 43 | 20 | Prohibited |

| Delaware | 33 | 58 | 6 | 67 | 6 | Permitted |

| Florida | 16 | 39 | 15 | 30 | 20 | Permitted |

| Georgia | 23 | 48 | 13 | 38 | 17 | Permitted |

| Kentucky | 16 | 77 | 12 | 57 | 12 | No law |

| Louisiana | 32 | 51 | 8 | 51 | 13 | Limited |

| Maryland | 15 | 40 | 20 | 49 | 8 | Permitted |

| Mississippi | 38 | 81 | 5 | 29 | 32 | Prohibited |

| North Carolina | 15 | 71 | 14 | 30 | 12 | Limited |

| Oklahoma | 23 | 66 | 8 | 30 | 46 | No law |

| South Carolina | 19 | 79 | 13 | 40 | 18 | Prohibited |

| Tennessee | 21 | 53 | 12 | 32 | 13 | Permitted |

| Texas | 21 | 55 | 7 | 20 | 41 | Limited |

| Virginia | 26 | 66 | 17 | 22 | 14 | Limited |

| West Virginia | 21 | 67 | 11 | 30 | 24 | Prohibited |

| West | 22 | 63 | 10 | 32 | 37 | -- |

| Alaska | 14 | 62 | 0 | 76 | 19 | No law |

| Arizona | 24 | 41 | 14 | 13 | 42 | Permitted |

| California | 13 | 46 | 14 | 27 | 32 | Permitted |

| Colorado | 26 | 50 | 11 | 22 | 36 | Permitted |

| Hawaii | 20 | 50 | 4 | 84 | 0 | No law |

| Idaho | 23 | 75 | 14 | 20 | 43 | No law |

| Montana | 30 | 92 | 8 | 21 | 73 | Prohibited |

| Nevada | 23 | 45 | 14 | 25 | 41 | Prohibited |

| New Mexico | 32 | 76 | 14 | 18 | 46 | Limited |

| Oregon | 13 | 77 | 12 | 27 | 9 | Permitted |

| Utah | 23 | 51 | 8 | 36 | 38 | No law |

| Washington | 5 | 59 | 14 | 33 | 17 | Limited |

| Wyoming | 37 | 89 | 9 | 16 | 80 | No law |

| U.S. Overall | 20 | 62 | 14 | 35 | 24 | -- |

| mph, miles per hour |

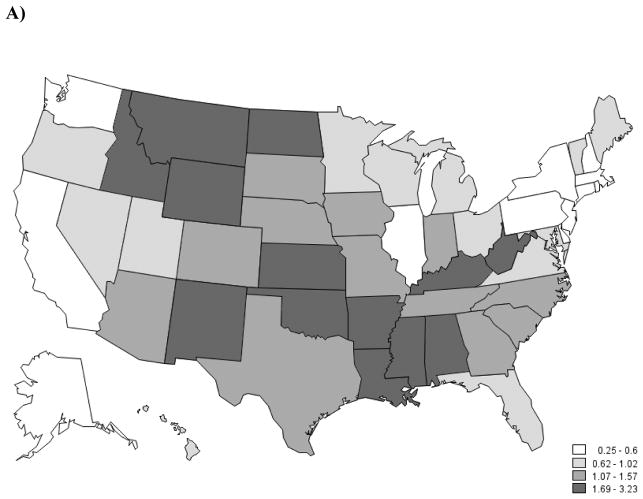

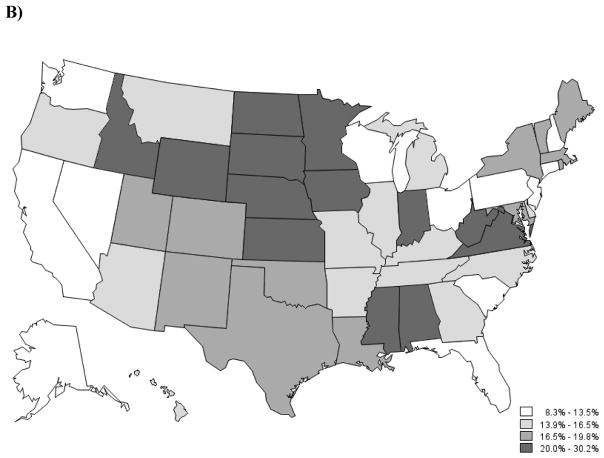

The number of fatal crashes over 2010–2014 ranged from 18 in Rhode Island to 2,017 in Texas, while the number of deaths ranged from 3 in Rhode Island to 346 in Texas. AAMR per 100,000 children varied from 0.25 in Massachusetts to 3.23 in Mississippi. The percentage of children that died of those involved in a fatal crash varied from 8% in New Hampshire to 30% in Nebraska (Table III; available at www.jpeds.com). The geographic distribution of AAMR and percentage of children that died of those involved in a fatal crash are illustrated graphically in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Deaths and age-adjusted mean mortality rates per 100,000 children by state, 2010–2014

| State | Number involved in a crash | Deaths | Percentage died (%) | Mortality rate per 100,000children per year* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midwest | 3,468 | 585 | 17 | 0.89 |

| Illinois | 473 | 75 | 16 | 0.60 |

| Indiana | 313 | 72 | 23 | 1.10 |

| Iowa | 123 | 33 | 27 | 1.10 |

| Kansas | 249 | 51 | 20 | 1.69 |

| Michigan | 417 | 60 | 14 | 0.65 |

| Minnesota | 178 | 38 | 21 | 0.71 |

| Missouri | 539 | 89 | 17 | 1.50 |

| Nebraska | 86 | 26 | 30 | 1.30 |

| North Dakota | 55 | 11 | 20 | 1.76 |

| Ohio | 707 | 83 | 12 | 0.75 |

| South Dakota | 54 | 13 | 24 | 1.52 |

| Wisconsin | 274 | 34 | 12 | 0.62 |

| Northeast | 1,365 | 189 | 14 | 0.38 |

| Connecticut | 84 | 11 | 13 | 0.34 |

| Maine | 42 | 7 | 17 | 0.68 |

| Massachusetts | 77 | 14 | 18 | 0.25 |

| New Hampshire | 60 | 5 | 8.3 | 0.48 |

| New Jersey | 232 | 26 | 11 | 0.32 |

| New York | 257 | 51 | 20 | 0.29 |

| Pennsylvania | 567 | 67 | 12 | 0.60 |

| Rhode Island | 18 | 3 | 17 | 0.33 |

| Vermont | 28 | 5 | 18 | 1.02 |

| South | 9,452 | 1,550 | 16 | 1.34 |

| Alabama | 551 | 125 | 23 | 2.71 |

| Arkansas | 349 | 51 | 15 | 1.72 |

| Delaware | 36 | 5 | 14 | 0.58 |

| Florida | 1,235 | 144 | 12 | 0.88 |

| Georgia | 788 | 130 | 16 | 1.26 |

| Kentucky | 457 | 73 | 16 | 1.71 |

| Louisiana | 417 | 81 | 19 | 1.76 |

| Maryland | 205 | 35 | 17 | 0.62 |

| Mississippi | 448 | 99 | 22 | 3.23 |

| North Carolina | 914 | 132 | 14 | 1.40 |

| Oklahoma | 467 | 80 | 17 | 2.02 |

| South Carolina | 467 | 63 | 13 | 1.39 |

| Tennessee | 671 | 97 | 14 | 1.57 |

| Texas | 2,017 | 346 | 17 | 1.17 |

| Virginia | 260 | 55 | 21 | 0.73 |

| West Virginia | 170 | 34 | 20 | 2.16 |

| West | 3,831 | 561 | 15 | 0.76 |

| Alaska | 37 | 4 | 11 | 0.50 |

| Arizona | 520 | 75 | 14 | 1.09 |

| California | 1,574 | 200 | 13 | 0.53 |

| Colorado | 333 | 55 | 17 | 1.07 |

| Hawaii | 56 | 9 | 16 | 0.70 |

| Idaho | 150 | 33 | 22 | 1.90 |

| Montana | 131 | 21 | 16 | 2.23 |

| Nevada | 157 | 21 | 13 | 0.75 |

| New Mexico | 256 | 43 | 17 | 1.98 |

| Oregon | 156 | 23 | 15 | 0.64 |

| Utah | 216 | 37 | 17 | 0.97 |

| Washington | 169 | 22 | 13 | 0.33 |

| Wyoming | 76 | 18 | 24 | 3.06 |

| U.S. Overall | 18,116 | 2,885 | 16 | 0.94 |

Mortality rates are age-adjusted with standardization by the total U.S. population within each age group. Reported rates are an average of the yearly rates from 2010 to 2014 for each state.

Figure 2.

Age-adjusted mean mortality rates from MVCs per 100,000 children, ages 0–14, 2010–2014 (A) and percentage of children that died in a severe MVC, ages 0–14, 2010–2014 (B)

Predictors of state-level mortality

Primary outcome

Based on our step-wise model-building process, we identified several state-level predictors associated with each outcome. In the model for AAMR, the factors that were significantly independently associated with increased mortality rates were a child being unrestrained or inappropriately restrained and the crash occurring on a rural road. For each 1% increase in the percentage of children who were unrestrained or inappropriately restrained, the AAMR increased by 0.038 (95% CI: 0.020, 0.057). Similarly, for each 1% increase in the percentage of crashes occurring on rural roads, the AAMR increased by 0.009 (95% CI: 0.002, 0.017). A protective effect was associated with the percentage of children riding in a vehicle classified as a van/minivan. For each 1% increase in the percentage of children riding in vans, the AAMR decreased by 0.021 (95% CI: 0.001, 0.042). These factors explained 68% of the variability in AAMR by state (Table IV).

Table 4.

State-level predictors of mortality: multivariable linear regression models for age-adjusted mortality rate per 100,000 children and percentage died of those involved in a fatal crash

| Age-adjusted mortality rate per 100,000 children | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor | Change in mortality rate per 100,000 children for each absolute % change in predictor | p-value |

| Percentage of children unrestrained or inappropriately restrained | 0.038 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of crashes on a rural road | 0.009 | 0.016 |

| Percentage of children in vans | −0.021 | 0.057 |

| Percentage of crashes on a U.S. highway | 0.015 | 0.076 |

| Percentage of households with a vehicle | 0.014 | 0.466 |

| Model R2 | 0.68 | |

| Percentage died of those involved in a fatal crash | ||

| Factor | Change in percentage died for each absolute% change in predictor | p-value |

| Percentage of children unrestrained or inappropriately restrained | 0.33 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of crashes on a state highway | −0.13 | <0.001 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in 65–80 mph zones | −0.11 | 0.002 |

| Percentage of crashes on a rural road | 0.05 | 0.012 |

| Change in percentage died | ||

| No state legislation on red light cameras (versus state legislation) | 3.73 | <0.001 |

| Model R2 | 0.67 |

Secondary outcome

In the model for percentage of children that died of those involved in a fatal crash, the factors that were significantly independently associated with increased likelihood of death were, again, a child being unrestrained or inappropriately restrained and the crash occurring on a rural road, as well as absence of state legislation regarding red light cameras. For each 1% increase in the percentage of children who were unrestrained or inappropriately restrained, the percentage of children that died increased by 0.33% (95%CI: 0.21, 0.44). Similarly, for each 1% increase in the percentage of crashes occurring on rural roads, the percentage of children that died increased by 0.05% (95% CI: 0.01, 0.09). In states without legislation in place regarding red light cameras, the percentage of children that died was on average 3.73% higher (95%CI: 1.97, 5.48), compared with states with legislation in place. Protective effects were associated with the percentage of crashes occurring on state highways and percentage of crashes occurring on roads with a speed limit 65 to 80 mph. For each 1% increase in the percentage of crashes occurring on state highways, the percentage of children that died decreased by 0.13% (95% CI: 0.07, 0.20). Similarly, for each 1% increase in the percentage of crashes occurring on roads with a speed limit 65 to 80 mph, the percentage of children that died decreased by 0.11% (95%CI: 0.05, 0.18). Together, these factors explained 67% of the variability in percentage of children that died of those involved in a fatal crash (Table IV).

The state-level variability suggests potential for state and regional improvements in mortality. Further, if the identified risk factors are addressed, the models predict sizable improvements in MVC-related pediatric mortality nationally. For instance, a potential 10% absolute improvement in child restraint use – decreasing the average number of unrestrained or inappropriately restrained children from 20% to 10% nationally – would decrease the national age-adjusted MVC-related mortality rate from 0.94 to 0.56 per 100,000 children. For the current national population of 61.0 million children, this would lead to approximately 232 pediatric deaths averted per year. Over five years, this translates to greater than 1,100 pediatric deaths averted, or nearly 40% of the deaths observed over the 2010–2014 period.

Discussion

We analyzed data from the NHTSA’s Fatality Analysis Reporting System to assess geographic variation of pediatric mortality from MVCs in the U.S. and found substantial variation by state in AAMR as well as percentage of children that die of those involved in a fatal crash. Percentage of nonuse or misuse of restraints was a key predictor for both outcomes. Additional state-level characteristics that predicted increased risk of death included greater percentage of crashes on rural roads and absence of state red light camera legislation. Protective effects were observed for percentage of children riding in vans, percentage of crashes occurring on a state highway, and percentage of crashes occurring on roads with a speed limit 65 to 80 mph. We quantified the potential impact of improving appropriate child restraint use, with a prediction of at least 1,100 deaths averted over the next five years if the prevalence of unrestrained or inappropriately restrained children were reduced from 20% to 10% nationally.

These data are consistent with and extend those from prior reports. The cohort had similar age and sex characteristics compared with prior studies of child passengers involved in MVCs (32,33). Multiple studies have shown increased risk of death in children who are unrestrained or inappropriately restrained (2–4,9). A prior analysis of 2000–2005 FARS data in conjunction with a national sample of police-reported crashes, the National Automotive Sampling System (NASS), estimated risk-adjusted odds of death ranging from 6 to 17 times higher for unrestrained child passengers 8–17y in a tow-away crash, compared with those who were restrained (9). In younger children, another FARS/NASS study found a 28% reduction in risk of death when children 2–6y were restrained with an appropriate child seat, compared with a seat belt (3). In addition, a national survey found that inappropriately restrained children <16y were nearly twice as likely to sustain a clinically significant injury and unrestrained children were >3 times as likely, compared with appropriately restrained children (34). Our findings highlight the importance of appropriate child restraint use; further, we present the results on the state level, where they may be best utilized by policy makers.

Rural roads have been previously associated with increased risk of death in a population-based study in Canada, which found the relative risk of MVC fatality to be five times higher in rural areas, compared with urban areas (13). In addition, rural roads may be associated with other factors not measured in our data, including poorer road quality, decreased lighting/visibility, decreased enforcement of speed limits, objects on the roadside, or distance to the nearest trauma center. Driver familiarity with rural roads may contribute to risk; a study of rural and urban drivers in Utah found that drivers residing in an urban county were nearly three times as likely to die in a crash in a rural area, compared with drivers residing in a rural county (12).

Of 20 different policy-specific variables examined in the analysis, the only one that remained significant in a final model was state-level policy on red light cameras. We found a higher risk of death in states without legislation regarding red light cameras. Prior evaluations of red light cameras have mixed results. A 2005 Cochrane review including 10 controlled before-after studies found that red light cameras are effective in reducing total fatal crashes, with results less conclusive on total collisions and violations (35). More recently, another review published similar findings (36). However, there has been methodological critique of the published studies, with some authors arguing that red light cameras may not improve and may actually increase crashes and injuries (37,38). To date, there are no randomized, controlled trials published on red light cameras. Our findings suggest an association between states that have legislation either permitting or prohibiting red light cameras and lower state MVC-related pediatric mortality; having legislation in place regarding red light cameras may be a proxy for a state’s overall interest in prioritizing legislation and enforcement of traffic safety measures. Notably, other policy-specific variables, including those addressing seat belt and car seat laws, did not have statistically significant associations with the outcomes. This suggests that there may be a gap between legislation and enforcement of these regulations.

We observed protective effects for several variables. Increased percentage of crashes in which the child was riding in a van was associated with decreased mortality, consistent with known better occupant protection in light trucks and vans versus cars (39). However, current evidence suggests that the protective benefit of larger vehicles must be balanced with increased threat of injury to pedestrians and occupants of smaller vehicles (39–41). Protective associations from state highways and roads with speed limits 65 to 80 mph are more challenging to understand. Although several studies demonstrated increased MVC-related mortality associated with increased speed limits after the 1995 repeal of the National Maximum Speed Limit (NMSL) (42–45), one state-level study in Utah did not identify a “major overall effect of NMSL repeal and increased speed limit on crash occurrence on Utah highways (46).” Our estimates represent the independent effect of each factor. For instance, the bivariate correlation between roads with speed limits 65 to 80 mph and the percentage of children that died of those involved in a fatal MVC was positive. However, after adjusting for the other factors in the model – including restraint use – the independent effect of speed limit became protective. This may reflect unmeasured characteristics of roads with high speed limits, such as better maintenance, fewer curves, wider lanes and shoulders, and more expeditious access by emergency medical vehicles (47).

The implications of this work are two-fold. First, the nature of the factors identified as predictive of pediatric mortality from fatal crashes suggests that state policy characteristics are an important mechanism to decrease pediatric deaths from MVCs. Further, full implementation of policies is necessary to ensure child safety – uneven implementation and enforcement may contribute to the state-level variation we observed. Previous research has discussed the potential for a federal intervention in the area of child traffic safety if states are not able to implement policies successfully (17). Absent this, there remains need for close collaboration between the injury prevention community and those enacting and enforcing legislation (48).

The results of this study must be interpreted in the context of the study design. The strength of the FARS dataset is that it includes all MVC occurrences, allowing us to understand the national distribution of MVCs. However, FARS only provides information on crashes with at least one fatality, and the NASS, a national sample of all MVCs, does not provide state-level information. This limited our ability to understand pediatric deaths from MVCs in the context of all MVCs. We addressed this by using two different outcomes: AAMR (which were not dependent on the total number of crashes), and percentage of children that died of those involved in a fatal crash. Although the ecological study design was well-suited to broadly define key policy areas that may improve MVC-related pediatric mortality, we were not able to examine intricacies surrounding some of the variables; for instance, red light cameras are thought to reduce angle crashes only, which was not represented in ouranalysis.

In conclusion, we found substantial geographic variation in likelihood of death for children involved in a fatal MVC. The percentage of children who are unrestrained or inappropriately restrained is a leading predictor of mortality; this supports recommendations from the AAP that uniform enforcement of appropriate child safety restraints is crucial to reduce MVC-related child deaths. In addition, we found that state law surrounding red light cameras may be an influential policy area related to MVC-related pediatric mortality. Further research is required to understand how vehicle type, roadway characteristics, speed limits, and red light camera use may contribute to overall risk of death. However, the results on child restraints are clear: policy and enforcement interventions have the potential for substantial impact on the reduction of MVC-related pediatric mortality.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the American College of Surgeons Resident Research Scholarship (to L.W.) and the U.S. National Institute of Health/National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (5K24AR057827-02 [to E.L.]). A.H. is the PI of a contract (AD-1306-03980) with the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute entitled “Patient-Centered Approaches to Collect Sexual Orientation/Gender Identity in the ED” and a Harvard Surgery Affinity Research Collaborative (ARC) Program Grant entitled “Mitigating Disparities Through Enhancing Surgeons’ Ability To Provide Culturally Relevant Care.”

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AAMR

age-adjusted, MVC-related mortality rate per 100,000 children

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

- FARS

Fatality Analysis Reporting System

- MVC

motor vehicle crash

- NHTSA

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

- NMSL

National Maximum Speed Limit

- SUV

sport utility vehicle

Appendix. Variables included in model-building process

| Variable | Range |

|---|---|

| Passenger-level | |

| Mean age of child passenger | 5.4–8.2 |

| Percentage of child passengers that were female | 36–64 |

| Percentage of children ejected from the vehicle | 0–22 |

| Percentage of children extricated from the vehicle | 0–25 |

| Percentage of children seated in the front seat | 9–29 |

| Percentage of children seated inappropriately in the front seat | 5–19 |

| Percentage of children unrestrained or inappropriately restrained | 2–38 |

| Driver-level | |

| Mean driver age | 29.6–39.7 |

| Percentage of crashes with driver age <20y | 0–28 |

| Percentage of crashes with driver age 20–24y | 0–19 |

| Percentage of crashes with driver age >24y | 66–97 |

| Percentage of crashes with driver under the influence of alcohol | 1–28 |

| Vehicle-level | |

| Mean vehicle years on the road | 6.6–11.8 |

| Percentage of all vehicles in a crash that were cars | 19–63 |

| Percentage of all vehicles in a crash that were vans/minivans | 0–33 |

| Percentage of all vehicles in a crash that were SUVs | 11–49 |

| Percentage of all vehicles in a crash that were pick-up trucks | 6–36 |

| Percentage of all vehicles in a crash that were larger than a pick-up truck | 0–11 |

| Percentage of all vehicles in a crash with disabling damage | 41–100 |

| Percentage of all vehicles in a crash with intrusion | 0–6 |

| Percentage of all vehicles in a crash with rollover mechanism | 5–64 |

| Crash-level | |

| Mean speed limit at crash site | 39–66 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in a 5–20 miles per hour speed limit zone | 0–05 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in a 25–40 miles per hour speed limit zone | 4–55 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in a 45–60 miles per hour speed limit zone | 11–81 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in a 65–80 miles per hour speed limit zone | 0–80 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in a zone with no speed limit | 0–18 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring on an interstate | 0–47 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring on a U.S. highway | 0–51 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring on a state highway | 11–84 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring on a county road | 0–42 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring on a local street | 0–44 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring on other roadway | 0–32 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring on a rural road | 17–100 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring during the day (6a–6p) | 50–79 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring over the weekend (Fri 5p–Mon 6a) | 32–64 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in the winter (Dec–Feb) | 6–68 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in the spring (Mar–May) | 4–39 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in the summer (Jun–Aug) | 11–66 |

| Percentage of crashes occurring in the fall (Sep–Nov) | 7–44 |

| State policy-level | |

| State open container law meeting federal requirements | 0–1 |

| State repeat offender law (for driving under the influence) meeting federal requirements | 0–1 |

| State administrative license suspension on first offense/refusal to submit to a chemical test for driving under the influence | 0–1 |

| State mandatory vehicle or license plate sanctions for driving under the influence | 0–1 |

| State maximum fine for first offense violating state child restraint laws | 10–500 |

| State maximum fine for first offense violating state seat belt laws | 0–200 |

| State maximum allowed speed limit | 55–85 |

| State law stating a preference for seating children in the rear seat | 0–1 |

| State has ≥1 level 1 pediatric trauma center | 0–1 |

| State number of level 1 pediatric trauma centers | 0–5 |

| State has ≥1 level 1 or level 2 pediatric trauma center | 0–1 |

| State number of level 2 pediatric trauma centers | 0–4 |

| State number of level 1 and level 2 pediatric trauma centers | 0–8 |

| State number of level 1 and level 2 pediatric trauma centers per 100,000 children | 0–0.75 |

| State trauma system in place (none, unfunded, funded) | 0–2 |

| State requires children to be in a rear-facing child safety seat when <1y or <20 pounds | 0–1 |

| State red light camera legislation present | 0–1 |

| State red light camera use prohibited | 0–1 |

| State red light camera use limited | 0–1 |

| State red light camera use permitted | 0–1 |

| State red light cameras in current use | 0–1 |

| State speed camera legislation present | 0–1 |

| State speed camera use prohibited | 0–1 |

| State speed camera use limited | 0–1 |

| State speed camera use permitted | 0–1 |

| State speed cameras in current use | 0–1 |

| State law allowing primary enforcement of seat belt laws for children | 0–1 |

Footnotes

The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Portions of this study were presented as an oral presentation at the American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference & Exhibition in San Francisco, California, October 21–25, 2016.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vital signs: Unintentional injury deaths among persons aged 0–19 years - United States, 2000–2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Apr 20;61:270–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee LK, Farrell CA, Mannix R. Restraint use in motor vehicle crash fatalities in children 0 year to 9 years old. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015 Sep;79:S55–60. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott MR, Kallan MJ, Durbin DR, Winston FK. Effectiveness of child safety seats vs seat belts in reducing risk for death in children in passenger vehicle crashes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006 Jun;160:617–21. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.6.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glass RJ, Segui-Gomez M, Graham JD. Child passenger safety: decisions about seating location, airbag exposure, and restraint use. Risk Anal. 2000 Aug;20:521–7. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.204049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braver ER, Whitfield R, Ferguson SA. Seating positions and children’s risk of dying in motor vehicle crashes. Inj Prev. 1998 Sep;4:181–7. doi: 10.1136/ip.4.3.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durbin DR, Jermakian JS, Kallan MJ, McCartt AT, Arbogast KB, Zonfrillo MR, et al. Rear seat safety: Variation in protection by occupant, crash and vehicle characteristics. Accid Anal Prev. 2015 Jul;80:185–92. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quinlan K, Shults RA, Rudd RA. Child passenger deaths involving alcohol-impaired drivers. Pediatrics. 2014 Jun;133:966–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kelley-Baker T, Romano E. Child passengers killed in reckless and alcohol-related motor vehicle crashes. J Saf Res. 2014;48:103–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winston FK, Kallan MJ, Senserrick TM, Elliott MR. Risk factors for death among older child and teenaged motor vehicle passengers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008 Mar;162:253–60. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margolis LH, Foss RD, Tolbert WG. Alcohol and motor vehicle-related deaths of children as passengers, pedestrians, and bicyclists. JAMA. 2000 May 3;283:2245–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartle ST, Baldwin ST, Johnston C, King W. 70-mph speed limit and motor vehicular fatalities on interstate highways. Am J Emerg Med. 2003 Sep;21:429–34. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(03)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donaldson AE, Cook LJ, Hutchings CB, Dean JM. Crossing county lines: the impact of crash location and driver’s residence on motor vehicle crash fatality. Accid Anal Prev. 2006 Jul;38:723–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kmet L, Macarthur C. Urban-rural differences in motor vehicle crash fatality and hospitalization rates among children and youth. Accid Anal Prev. 2006 Jan;38:122–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Durbin DR. Child passenger safety. Pediatrics. 2011 Apr;127:788–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Recommendations to Reduce Injuries to Motor Vehicle Occupants Increasing Child Safety Seat Use, Increasing Safety Belt Use, and Reducing Alcohol-Impaired Driving. public. Heal Pract J Prev Med. 2001;21:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weatherwax M, Coddington J, Ahmed A, Richards EA. Child Passenger Safety Policy and Guidelines: Why Change Is Imperative. J Pediatr Health Care. 2016;30:160–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae JY, Anderson E, Silver D, Macinko J. Child passenger safety laws in the United States, 1978–2010: policy diffusion in the absence of strong federal intervention. Soc Sci Med. 2014 Jan;100:30–7. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United States Department of Transportation. Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) Analytical User’s Manual, 1975–2014. [Internet] [cited 2016 Jun 8]. Available from: ftp://ftp.nhtsa.dot.gov/fars/FARS-DOC/Analytical User Guide/USERGUIDE-2014.pdf.

- 19.United States Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 [Internet] [cited 2016 Jun 28]. Available from: http://factfinder.census.gov/

- 20.United States Census Bureau. Selected Housing Characteristics. 2010–2014 American Community Survey 5-year Estimates. [Internet] [cited 2016 Jun 10]. Available from: http://factfinder.census.gov/

- 21.Governors Highway Safety Association. Highway Safety Law Charts [Internet] [cited 2016 Jun 28]. Available from: http://www.ghsa.org/html/stateinfo/laws/index.html.

- 22.Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. Highway safety topics [Internet] [cited 2016 Jun 28]. Available from: http://www.iihs.org/iihs/topics.

- 23.Rivara FP, Cummings P, Mock C. Injuries and death of children in rollover motor vehicle crashes in the United States. Inj Prev. 2003 Mar;9:76–80. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen IG, Durbin DR, Elliott MR, Senserrick T, Winston FK. Child passenger injury risk in motor vehicle crashes: a comparison of nighttime and daytime driving by teenage and adult drivers. J Saf Res. 2006;37:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson EC, Perkowski P, Villarreal D, Block EFJ, Brown MF, Wright L, et al. Morbidity and mortality of children following motor vehicle crashes. Arch Surg. 2003 Feb;138:142–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Notrica DM, Weiss J, Garcia-Filion P, Kuroiwa E, Clarke D, Harte M, et al. Pediatric trauma centers: correlation of ACS-verified trauma centers with CDC statewide pediatric mortality rates. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012 Sep;73:566–70-2. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318265ca6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carr BG, Nance ML. Access to pediatric trauma care: alignment of providers and health systems. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010 Jun;22:326–31. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283392a48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrosyan M, Guner YS, Emami CN, Ford HR. Disparities in the delivery of pediatric trauma care. J Trauma. 2009 Aug;67:S114–9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181ad3251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nance ML, Carr BG, Branas CC. Access to pediatric trauma care in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009 Jun;163:512–8. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osler TM, Vane DW, Tepas JJ, Rogers FB, Shackford SR, Badger GJ. Do pediatric trauma centers have better survival rates than adult trauma centers? An examination of the National Pediatric Trauma Registry. J Trauma. 2001 Jan;50:96–101. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200101000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly E, Kiemele ER, Reznor G, Havens JM, Cooper Z, Salim A. Trauma systems are associated with increased level 3 trauma centers. J Surg Res. 2015 Oct;198:489–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sauber-Schatz EK, Thomas AM, Cook LJ. Motor Vehicle Crashes, Medical Outcomes, and Hospital Charges Among Children Aged 1–12 Years — Crash Outcome Data Evaluation System, 11 States, 2005–2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2015 Oct 2;64:1–32. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6408a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charyk Stewart T, McClafferty K, Shkrum M, Comeau J-L, Gilliland J, Fraser DD. A comparison of injuries, crashes, and outcomes for pediatric rear occupants in traffic motor vehicle collisions. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Feb;74:628–33. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827d606c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Durbin DR, Chen I, Smith R, Elliott MR, Winston FK. Effects of seating position and appropriate restraint use on the risk of injury to children in motor vehicle crashes. Pediatrics. 2005 Mar;115:e305–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aeron-Thomas AS, Hess S. Red-light cameras for the prevention of road traffic crashes. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2005:CD003862. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003862.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Llau AF, Ahmed NU. The effectiveness of red light cameras in the United States-a literature review. Traffic Inj Prev. 2014;15:542–50. doi: 10.1080/15389588.2013.845751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langland-Orban B, Pracht EE, Large JT. Red Light Cameras Unsuccessful in Reducing Fatal Crashes in Large US Cities. Heal Behav Policy Rev. 2014 Jan 1;1:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Langland-Orban B, Pracht EE, Large JT, Zhang N, Tepas JT. Explaining Differences in Crash and Injury Crash Outcomes in Red Light Camera Studies. Eval Health Prof. 2016 Jun;39:226–44. doi: 10.1177/0163278714542245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ossiander EM, Koepsell TD, McKnight B. Crash fatality and vehicle incompatibility in collisions between cars and light trucks or vans. Inj Prev. 2014 Dec;20:373–9. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-041146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fredette M, Mambu LS, Chouinard A, Bellavance F. Safety impacts due to the incompatibility of SUVs, minivans, and pickup trucks in two-vehicle collisions. Accid Anal Prev. 2008 Nov;40:1987–95. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson M. Safety for whom? The effects of light trucks on traffic fatalities. J Health Econ. 2008 Jul;27:973–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedman LS, Hedeker D, Richter ED. Long-term effects of repealing the national maximum speed limit in the United States. Am J Public Health American Public Health Association. 2009 Sep;99:1626–31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grabowski DC, Morrisey MA. Systemwide implications of the repeal of the national maximum speed limit. Accid Anal Prev. 2007 Jan;39:180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shafi S, Gentilello L. A nationwide speed limit ≤65 miles per hour will save thousands of lives. Am J Surg. 2007 Jun;193:719–22. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farmer CM, Retting RA, Lund AK. Changes in motor vehicle occupant fatalities after repeal of the national maximum speed limit. Accid Anal Prev. 1999 Sep;31:537–43. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vernon DD, Cook LJ, Peterson KJ, Michael Dean J. Effect of repeal of the national maximum speed limit law on occurrence of crashes, injury crashes, and fatal crashes on Utah highways. Accid Anal Prev. 2004 Mar;36:223–9. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(02)00151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ivan JN, Garrick NW, Hanson G. Designing roads that guide drivers to choose safer speeds. Connecticut Cooperative Highway Research Program [Internet] 2009 Available from: http://www.ct.gov/dot/LIB/dot/documents/dresearch/JHR_09-321_JH_04-6.pdf.

- 48.Schieber RA, Gilchrist J, Sleet DA. Legislative and regulatory strategies to reduce childhood unintentional injuries. Future Child. 10:111–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.23 U.S. Code § 154 - Open container requirements. U.S. Congress;

- 50.23 U.S. Code § 164 - Minimum penalties for repeat offenders for driving while intoxicated or driving under the influence. U.S. Congress;