Abstract

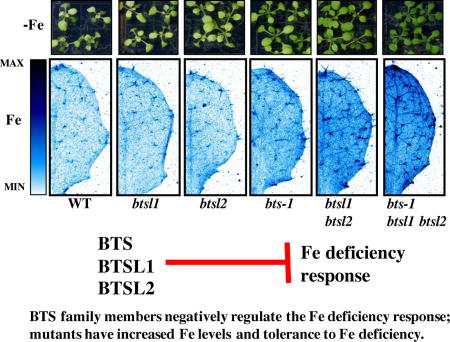

Iron (Fe) is required for plant health, but it can also be toxic when present in excess. Therefore, Fe levels must be tightly controlled. The Arabidopsis thaliana E3 ligase BRUTUS (BTS) is involved in the negative regulation of the Fe deficiency response and we show here that the two A. thaliana BTS paralogs, BTS LIKE1 (BTSL1) and BTS LIKE2 (BTSL2) encode proteins that act redundantly as negative regulators of the Fe deficiency response. Loss of both of these E3 ligases enhances tolerance to Fe deficiency. We further generated a triple mutant with loss of both BTS paralogs and a partial loss of BTS expression that exhibits even greater tolerance to Fe-deficient conditions and increased Fe accumulation without any resulting Fe toxicity effects. Finally, we identified a mutant carrying a novel missense mutation of BTS that exhibits an Fe deficiency response in the root when grown under both Fe-deficient and Fe-sufficient conditions, leading to Fe toxicity when plants are grown under Fe-sufficient conditions.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Iron (Fe) is essential for plant growth, crop yields and human health. Many people, particularly those in developing countries, rely on plants for dietary Fe. Unfortunately, Fe has a limited solubility in many neutral or basic soils and therefore Fe is not readily accessible in the rhizosphere1. This low solubility leads to a restricted Fe content in many plants and is a major factor contributing to the widespread prevalence of Fe deficiency anemia for people with plant-based diets. Thus, increasing plant Fe acquisition and storage may have profound impacts on plant and human nutrition. In order to manipulate plants to increase bioavailable Fe, it is first imperative we understand the genes and mechanisms governing Fe homeostasis in plants. When faced with low Fe conditions, non-graminaceous plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis) employ a classic response to boost Fe mobilization and uptake from the soil. Root plasma membrane H+-ATPases release protons to acidify and thus increase Fe solubility in the soil2. In addition to acidification, Fe3+ is reduced to Fe2+ by the membrane-bound ferric-chelate reductase enzyme FERRIC OXIDASE REDUCTASE 2 (FRO2) in Arabidopsis3. Fe deficiency also induces root secretion of phenolic compounds, particularly coumarins, which serve as direct Fe3+ reductants and also as Fe3+ and Fe2+ chelating compounds to improve Fe mobilization and reduction4–7. This series of mechanisms is known as the reduction strategy or alternatively Strategy I1. Reduced Fe is transported into the root by the plasma-membrane divalent cation transporter IRON-REGULATED TRANSPORTER 1 (IRT1)8–11.

These activities to boost Fe mobilization under Fe-deficient conditions are controlled by several transcription factors in Arabidopsis. One major transcription factor identified in a well-characterized Fe deficiency network is a bHLH protein called FER-LIKE IRON DEFICIENCY-INDUCED TRANSCRIPTION FACTOR (FIT)12–14. Like IRT1 and FRO2, FIT is induced in the root epidermis in Fe deficiency and expression of IRT1 and FRO2 requires FIT12–14. Other bHLH transcription factors which are induced in Fe-deficient conditions are those of the bHLH1b subfamily (bHLH38, bHLH39, bHLH100, bHLH101) and evidence suggests that FIT activity and activation of downstream Fe deficiency targets depends on heterodimerization of FIT with one of these bHLH transcription factors14–17. FIT also controls MYB10 and MYB72, two other transcription factors essential for growth of plants on low Fe conditions12, 18, 19.

Another set of transcriptional changes upon Fe deficiency occurs in the vasculature. A major player identified in this network is another bHLH transcription factor called POPEYE (PYE)20. PYE expression is highest in the root pericycle, but PYE protein is localized to the nuclei of all cells in Fe-deficient roots, suggesting that PYE may move throughout the root, linking it to the FIT network. PYE has been shown to negatively regulate the expression of known Fe deficiency targets NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 4 (NAS4), FERRIC REDUCTASE OXIDASE 3 (FRO3), and ZINC-INDUCED FACILITATOR (ZIF1). Like FIT, PYE may require other bHLH proteins as binding partners to interact with downstream targets. Yeast two hybrid, bimolecular fluorescence complementation, and pulldown analyses have demonstrated that PYE can interact with bHLH104, bHLH115, and bHLH105 or IAA-LEUCINE RESISTANT 3 (ILR3), three bHLH transcription factors belonging to bHLH subclade IVc (of which only bHLH115 has increased expression under Fe-deficiency)20–24. By coexpression analysis with PYE, a gene encoding a RING E3 ligase with three hemerythrin/HHE Fe-binding domains called BRUTUS (BTS) was also classified into this network. BTS is thought to act indirectly with PYE because although it does not itself interact with PYE, it interacts with the same three IVc bHLH transcription factors as PYE20. BTS was subsequently demonstrated to be a functional RING E3 ligase in vitro, and although it has not been confirmed in planta, the three IVc bHLH transcription factors are proposed as targets for proteasomal degradation after ubiquitination by BTS23. Two of these putative targets, bHLH104 and ILR3 (bHLH105), were recently identified as positive regulators of the Fe deficiency response because loss-of-function mutants exhibit decreased tolerance to Fe deficiency22. Further, bHLH104 and ILR3 regulate downstream expression of bHLH38/39/100/101 and PYE, genes from both the FIT and PYE networks22. bts knockdown mutants, on the other hand, exhibit increased tolerance to Fe deficiency and thus negatively regulate Fe uptake20, 22, 23. While a full length BTS construct can complement bts-1 mutant phenotypes under low Fe conditions, a deletion construct lacking the RING domain fails to complement the mutant, suggesting the E3 ligase activity of BTS is critical for BTS’ repressive role in the Fe deficiency response25. Interestingly, complete loss-of-function bts mutants exhibit embryo lethality26.Taken together, current data suggests a model where BTS acts as a negative regulator by targeting transcription factors important in positive regulation of the Fe deficiency response for degradation.

Understanding the balance between positive and negative regulation of the Fe deficiency response is essential for efforts to engineer plants with more Fe that do not experience Fe toxicity. Although plants are often challenged with Fe deficiency, no environment remains constant and Fe availability in the rhizosphere depends on many factors. When sufficient Fe is available, it is crucial for plants to effectively suppress the Fe deficiency response to avoid excessive uptake.

We found that in addition to BTS, two closely related RING E3 ligases that we named BRUTUS LIKE1 and BRUTUS LIKE2 are important in negative regulation of the Fe deficiency response. The double btsl1 btsl2 mutant has increased Fe concentrations and tolerance to Fe deficiency compared to wild type and the triple bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 mutant has even higher concentrations of Fe and tolerance to Fe deficiency, but without excessive Fe accumulation leading to Fe toxicity. Additionally, we identified a novel allele of BTS in a mutagenesis screen for altered Fe accumulation. This mutant, bts-3, contains a point mutation in the RING E3 ligase domain of BTS, suggesting its E3 ligase activity may be impaired. We sought to explore the unique nature of this missense mutant compared to the other bts mutants, which are either embryo lethal or have a reduction in steady-state transcript levels and likely represent partial-loss-of BTS function. bts-3 is more tolerant than wild type to Fe-deficient conditions. Further, bts-3 is sensitive to Fe-sufficient conditions and accumulates excessive Fe. Using microarray analysis, we demonstrated that these bts-3 phenotypes are associated with expression of the Fe deficiency response in the root under both Fe-sufficient and Fe-deficient growth conditions, despite accumulation of high concentrations of Fe in the root. Our characterization of btsl1, btsl2, and bts mutants increases our understanding of the role of BTS family members as negative regulators of the Arabidopsis Fe deficiency response.

Results

Identification of two BTS paralogs in Arabidopsis

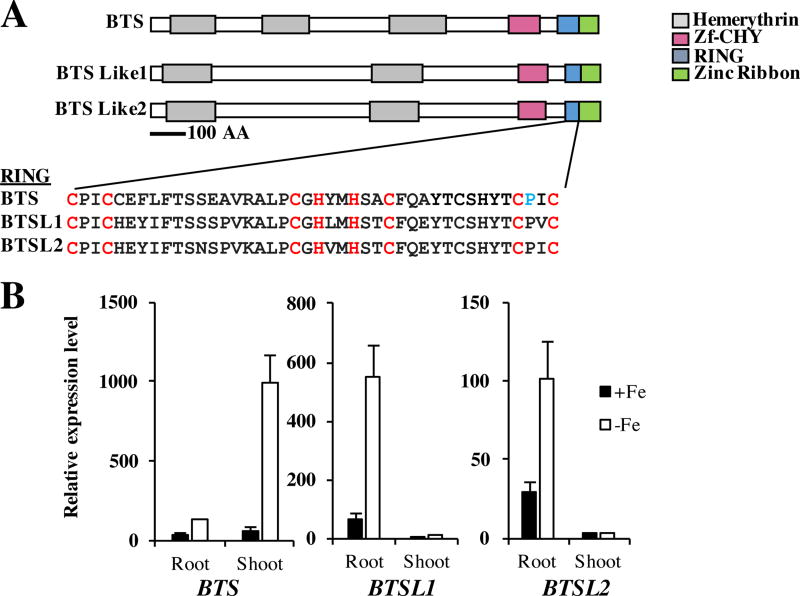

To determine if there are any other proteins which may play a similar or overlapping role to BTS, we used the Ensembl Plants bioinformatics tool to identify genes encoding proteins in Arabidopsis containing both putative hemerythrin and RING domains27. This analysis identified two BTS paralogs, At1g74770 (BTSL1) and At1g18910 (BTSL2) (Figure 1A). Using an amino acid alignment and identity matrix calculated by ClustalW of the proteins encoded by BTS, BTSL1 and BTSL2, we determined that BTSL1 and BTSL2 exhibit 72% amino acid identity and BTSL1 and BTSL2 each have 38% amino acid identity with BTS28. Analysis of domain architecture predicted by NCBI CD-Search revealed that while BTS contains three putative hemerythrin domains, BTSL1 and BTSL2 each contain two (Figure 1A)29. Each E3 ligase also contains a C-terminal Zf-CHY, RING, and Zinc ribbon domain. The RING domain of each protein has a conserved octet of Cys and His residues that form a canonical C3H2C3 RING structure for Zn2+ coordination and predicted RING E3 ligase enzymatic activity (Figure 1A). These proteins were also identified in a phylogenetic analysis of hemerythrin domain containing proteins in a study examining the role of the BTS orthologs in rice, Oryza sativa Haemerythrin motif-containing Really Interesting New Gene (RING)- and Zinc-finger proteins 1 and 2 (OsHRZ1 and OsHRZ2)30.

Figure 1. BTS, BTSL1, and BTSL2 are a family of closely-related RING E3 ligases regulated by Fe deficiency.

A. BTS, BTSL1 and BTSL2 have very similar protein domain architectures including hemerythrin domains and a C-terminal RING E3 ligase domain. The RING domain is highly conserved among family members. Conserved Cys and His Zn2+-binding residues for each C3H2C3 type RING are shown in red. The BTS Pro residue shown in blue is mutated to Leu in bts-3 plants. Protein domain structure was predicted by NCBI’s conserved domain database29.

B. qPCR of BTS, BTSL1 and BTSL2 expression in roots and shoots of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium and then transferred to +Fe or −Fe medium for 3 days. Expression is relative to EF1α. Error bars represent SE (n=3).

All three genes of the BTS family in Arabidopsis exhibit significantly increased expression in roots of plants exposed to Fe-deficient conditions compared to those grown under Fe-sufficient conditions (Figure 1B). BTS and BTSL2 are expressed at similar levels in the roots and both exhibit approximately a 3-fold increase in expression in Fe-deficient conditions compared to Fe-sufficient conditions. BTSL1, on the other hand, exhibits an 8-fold increase in expression in Fe-deficient conditions. In the shoot, we found significant expression of BTS, which, like in roots, is increased in response to Fe-deficient growth conditions (approximately a 16-fold induction) (Figure 1B). BTSL1 and BTSL2 were not significantly expressed in shoots, regardless of Fe status.

Knockdown of BTS family E3 ligases increases tissue Fe concentrations and tolerance to Fe deficiency

A previously identified bts-1 T-DNA insertion mutant has steady state mRNA levels 70% of those in wild type, and is more tolerant to Fe deficiency than wild type20, 23. Because BTSL1 and BTSL2 are also expressed under Fe-deficient conditions in the root, we wanted to determine if loss of BTSL1 and BTSL2 would affect tolerance to Fe deficiency. We obtained T-DNA insertion lines for each gene (Supplemental Figure 1A). The T-DNA insertion in exon two of BTSL1 in SALK_015054 results in complete loss of full-length BTSL1 transcript (Supplemental Figure 1B). In BTSL2, sequencing revealed that although the entire open reading frame is present, the T-DNA insertion in SAIL_615_H01 results in a chimeric transcript containing segments of T-DNA, promoter, and the 5’UTR fused upstream of the BTSL2 open reading frame. This chimeric transcript contains several alternative start sites, making it unlikely that the native translation product is produced in this line (Supplemental Figure 1B).

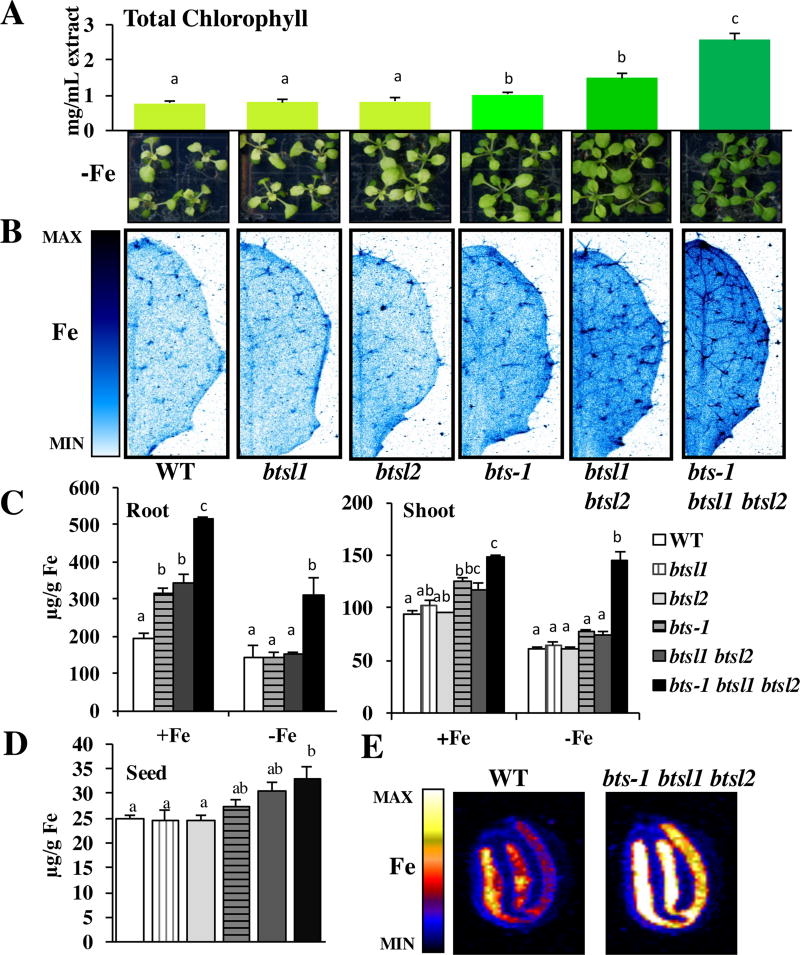

Compared to wild type shoots which exhibit chlorosis when grown under Fe-deficient conditions, bts-1 plants were greener and contained significantly more chlorophyll (a 44% increase compared to wild type) (Figure 2A), and as demonstrated previously, had longer roots than wild type when grown vertically under Fe-deficient growth conditions (Supplemental Figure 2A). By the same parameters, btsl1 and btsl2 single mutants were indistinguishable from wild type (Figure 2A, Supplemental Figure 2A). However, due to their high amino acid identity, we hypothesized that BTSL1 and BTSL2 function redundantly and thus we generated the double btsl1 btsl2 mutant. Like bts-1, btsl1 btsl2 had greener shoots, higher chlorophyll levels (a 92% increase compared to wild type), and increased root length when plants were grown under Fe-deficient conditions (Figure 2A, Supplemental Figure 2A) compared to wild type. Further, bts-1 and the btsl1 btsl2 double mutant had significantly higher Fe concentrations in roots (65% and 78% respectively) and shoots (33% and 25% respectively) of plants grown under Fe-sufficient conditions compared to wild type (Figure 2C). To assess whether both reduction of BTS and loss of BTSL1 and BTSL2 expression can further increase Fe content and tolerance to Fe deficiency, we created the triple bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 mutant. Compared to the single bts-1 mutant and the btsl1 btsl2 double mutant alone, the triple bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 mutant exhibited additional tolerance to Fe deficiency as seen by visibly greener shoots, significantly increased chlorophyll concentrations (236% increase compared to wild type), and longer roots when plants were grown on Fe-deficient conditions (Figure 2A, Supplemental Figure 2A). The triple mutant also had significantly higher Fe concentrations in roots and shoots of plants grown under both Fe regimes compared to wild type (Figure 2C). In addition, we found that triple mutant seeds have significantly higher concentrations of Fe than wild type (32% increase) (Figure 2D). Imaging Fe in situ in intact seeds revealed that although seed Fe concentrations are increased significantly in the triple mutant, Fe localization is not perturbed from wild type and is associated with the embryonic vasculature as previously described (Figure 2E)31.

Figure 2. bts and btsl1/2 mutants have increased Fe concentrations and tolerance to Fe deficiency.

A. Chlorophyll levels were measured on plants grown for 10 days on B5 and then transferred to −Fe medium for 7 days (n=3). Representative images of plants shown below. B. Representative SXRF scans showing Fe localization in leaf #5 of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 and then transferred to +Fe medium for 3 days. C. Root and shoot ICP-MS measurements of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 and then transferred to +Fe or −Fe medium for 3 days (n=3) D. Seed ICP-MS measurements from soil grown plants (n=5). E. Representative SXRF scan showing Fe localization in mature, dry seed. In panels A, C, and D, lower case letters indicate significant differences at p<0.05 (ANOVA with Tukey’s). Error bars indicate SE.

Increased Fe concentrations and storage in these mutants is not associated with Fe toxicity

Because increased Fe accumulation can be toxic to plants, we assessed btsl1, btsl2, bts-1, btsl1 btsl2, and bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 for signs of Fe toxicity, such as stunted root growth or necrosis, when plants were grown under Fe-sufficient conditions. None of these mutants appeared different from wild type under these conditions (Supplemental Figure 2B). Thus, increased Fe concentrations in these mutants enhances tolerance to Fe-deficient growth conditions, but does not negatively impact growth under Fe-sufficient conditions. Because of this, we were interested in where these mutants store Fe to detoxify it. To address this question, we imaged Fe in vivo in intact leaves of our mutants compared to wild type plants grown under Fe-sufficient conditions. This in vivo elemental imaging also demonstrated increased Fe levels in mutants (Figure 2B), supporting data obtained by the bulk quantification of Fe concentrations in digested whole leaves (Figure 2B and Figure 2C). From a two-dimensional perspective, in wild type, btsl1 and btsl2 single mutants, Fe is distributed relatively evenly throughout the leaf surface with some enrichment in the main vein and in trichomes. In bts-1 and btsl1 btsl2, Fe accumulation is increased throughout the leaf, the central vein, and trichomes compared to wild type. The triple mutant exhibits a further increase in Fe throughout the leaf compared to bts-1 and btsl1 btsl2 and increased enrichment of Fe in the central vein and trichomes and in minor veins (Figure 2B). These data suggest these regions are sites of Fe accumulation/storage in Arabidopsis leaves.

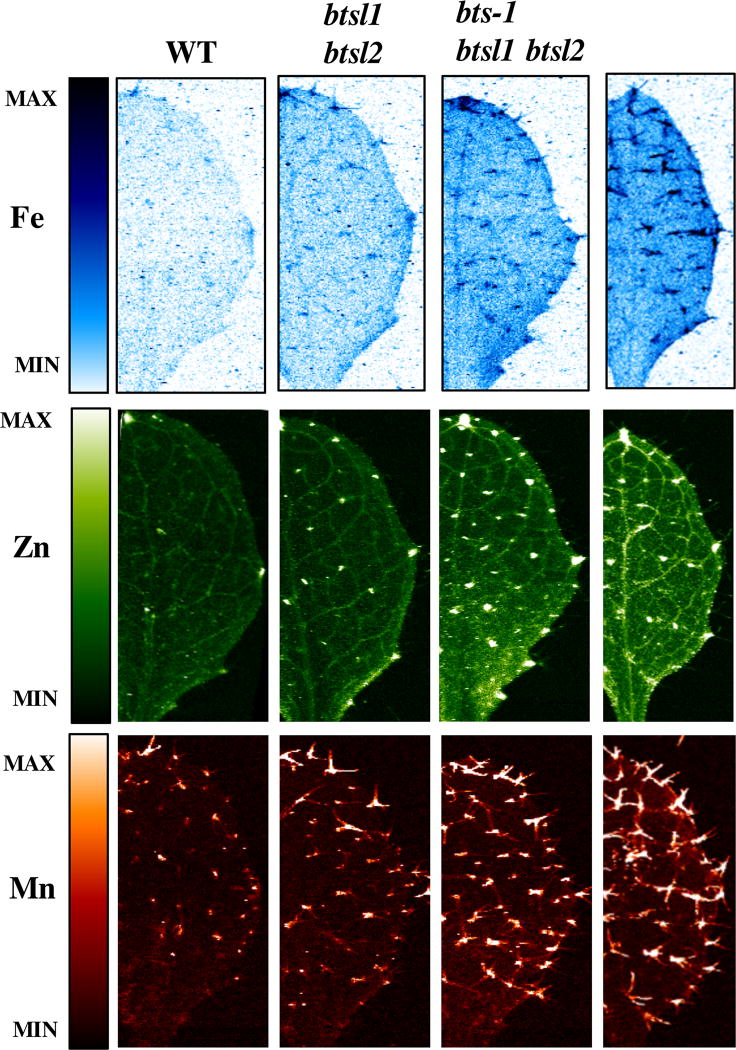

Elemental imaging of leaves from plants grown under Fe-deficient conditions demonstrates that in wild type, trichomes are depleted of Fe and no enrichment can be seen in the main vein as in plants grown under Fe-sufficient conditions (Figure 3 top panel). The double mutant has less Fe in the trichomes of plants exposed to Fe-deficient conditions compared to Fe-sufficient conditions, but still contains Fe in trichomes and the main vein, which is not seen in wild type (Figure 2B and Figure 3). In agreement with increased total leaf Fe concentrations (Figure 2C), the triple mutant has even more Fe in the trichomes, the main vein, and throughout the leaf tissue compared to the double mutant (Figure 3).

Figure 3. bts and btsl1/2 mutants store more Fe, Zn and Mn in veins, hydathodes and trichomes than wild type.

SXRF scans showing Fe, Zn, and Mn localization in leaf #5 of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium and then transferred to −Fe medium for 3 days.

BTS family E3 ligase mutants also have increased concentrations of other metals

Because metals share and compete for uptake transporters, we wanted to determine if our mutants had higher concentrations of other essential micronutrient metals, particularly those transported by IRT1: Zn and Mn8, 32. We found that in roots, the double btsl1 btsl2 and triple bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 mutants had significantly higher Zn concentrations compared to wild type and bts-1 (Supplemental Figure 3A). In shoots, the double and triple mutants had significantly higher concentrations of Zn compared to wild type and bts-1 and the triple mutant had significantly higher concentrations of Mn compared to wild type, bts-1, and btsl1 btsl2 (Supplemental Figure 3A). None of the mutants had elevated concentrations of Cu, a metal not transported by IRT1, in either roots or shoots. In seeds, we found significantly higher concentrations of Mn and Zn in bts-1, btsl1 btsl2, and bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 compared to wild type (51%, 35%, and 46% increases of Mn compared to wild type, respectively and 22%, 36%, and 60% increases of Zn compared to wild type, respectively) (Supplemental Figure 3B).

We imaged Zn and Mn in vivo in intact leaves in shoots of the double and triple mutants compared to wild type (Figure 3 middle and bottom panels). We found that in wild type leaves, Zn enrichment is mainly found in hydathodes and veins. In btsl1 btsl2 and bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 mutants, Zn accumulates in the hydathodes, and more is seen in the veins and at the base of trichomes. Mn is found mainly at the base of the trichomes in wild type and in the double and triple mutants, it can be seen in the stalk and branches of trichomes. These increases we see in Zn and Mn at specific sites in the leaf are in agreement with the increases in Zn and Mn concentrations we observe in digested whole leaf samples (Supplemental Figure 3A).

Identification of bts-3, an Fe overaccumulating BTS mutant

In an attempt to uncover additional regulators of the Fe deficiency response, we screened leaves from over 6,000 EMS mutagenized Arabidopsis plants following a high throughput elemental profiling approach we previously used33 to successfully identify mutants with altered elemental profiles (aka ionome)34–38. In this screen, we identified a mutant that accumulated significantly more Fe than wild type. The mutant was backcrossed twice and the mutation determined to be recessive. Bulk segregant analysis with microarray-based detection of genetic markers on phenotyped pools of F2 plants from a bts-3 × Ler outcross, following our previously developed approach39–41, placed the causal mutation in a 1 Mb interval centered at 6 Mb on chromosome 3. Fine mapping of F2 recombinants using SNP-based markers was used to narrow down the mutation to a region of chromosome 3 between 6237000 and 6342000. Sequencing in this region revealed a C to T mutation at base pair 5753 of BTS genomic DNA. The single base pair change in this bts-3 mutant confers a Pro to Leu change at amino acid 1174 in the RING domain of BTS (Figure 1A).

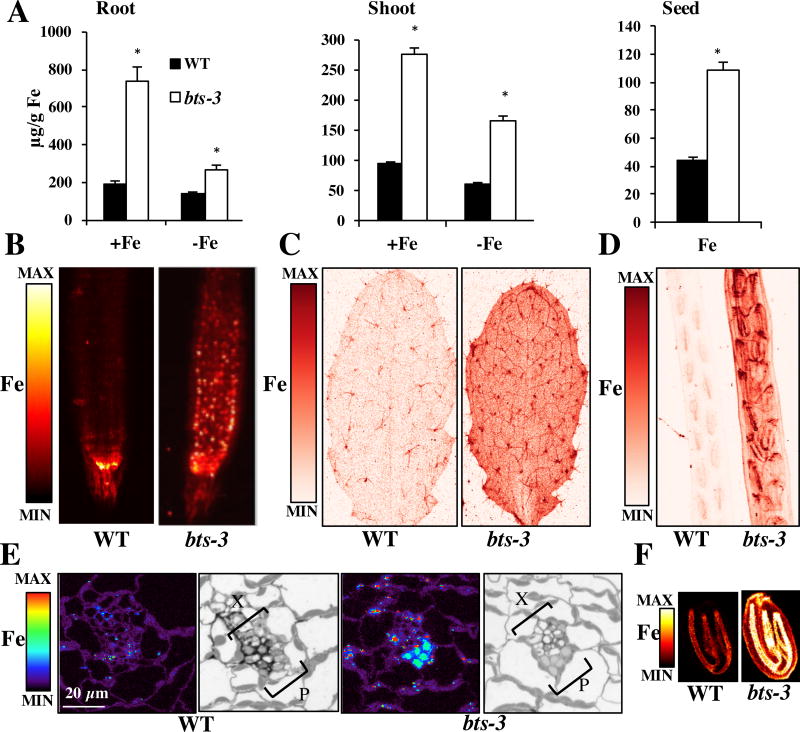

Elemental analysis revealed that bts-3 contained significantly higher concentrations of Fe in roots and shoots when grown under Fe-sufficient and Fe-deficient conditions compared to wild type confirming the results obtained in the original screen (Figure 4A). bts-3 seeds have Fe concentrations that are more than double than those of wild type, (a 244% increase) compared to the 32% increase in seed Fe of the bts-1 bts1 btsl2 triple mutant compared to wild type (Figure 4A, Figure 2D). bts-3 also had significantly higher concentrations of Fe in roots of plants grown under Fe-sufficient conditions and in shoots of plants grown under both Fe conditions compared to the triple mutant (Figure 2C and Figure 4A). We also performed in vivo elemental imaging on intact tissues and we found that increased Fe accumulation occurs in both roots and shoots in bts-3 compared to wild type (Figure 4B–C), confirming our analysis of the total Fe concentration in whole roots and leaves (Figure 4A). In roots, where Fe uptake from the rhizosphere occurs, Fe in wild type was mainly localized to a distinct portion of the root meristem, perhaps the quiescent center (Figure 4B). In bts-3 roots, however, Fe was dispersed beyond this region in puncta, which may represent vacuolar Fe storage sites. In Fe-sufficient leaves, Fe was also greatly increased, particularly in the vasculature (including the central vein and minor veins) and trichomes (Figure 4C). We also examined bts-3 alongside the previously imaged Fe-deficient leaves and found that bts-3 leaves have increased Fe storage in trichomes and throughout the leaf tissue compared to the double and triple mutants (Figure 3). Because our two-dimensional analysis revealed an increase in Fe associated with the vasculature in bts-3, we wanted to determine where Fe accumulates at the cellular level. Elemental imaging of manually cross-sectioned primary vasculature revealed that bts-3 has higher levels of Fe in phloem compared to wild type (Figure 4E). Finally, in vivo elemental imaging of seeds within green siliques and of dry seed demonstrated that Fe is associated with the vasculature of the embryo at a much higher concentration in bts-3 seed compared to wild type (Figure 4D, Figure 4F). Higher resolution elemental imaging reveals that Fe also accumulates in the seed coat of bts-3 (Figure 4F).

Figure 4. bts-3 has high concentrations of Fe in roots, leaves, and seeds.

A. ICP-MS measurements of roots and shoots of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium and then transferred to +Fe or −Fe medium for 3 days (n=3). ICP-MS measurements of seeds from soil-grown plants (n=5 plants). *p<0.05 between genotypes (student’s t-test). Error bars indicate SE. B. Representative SXRF scans of root tips of plants grown for 7 days on B5 medium and then transferred to −Fe medium for 3 days. C. SXRF scan of leaf #8 showing Fe in red. D. SXRF scan showing Fe (red), Zn (green), Mn (blue) localization in developed, green siliques. E. SXRF scan showing Fe localization in resin-embedded shoot primary vein cross sections. Plants were grown on B5 medium for 2 weeks. Bright field light microscopy images of adjacent sections stained with toluidine blue are shown for reference. X indicates xylem and P indicates phloem F. SXRF images show Fe localization to the vasculature in individual seeds.

bts-3 also accumulates high concentrations of other metals

We wanted to determine if bts-3 had increased concentrations of other metals in addition to Fe. Bulk analysis of digested whole leaves revealed increases in Mn and Zn concentrations compared to wild type in both roots and shoots of bts-3 plants (Supplemental Figure 3A). Compared to the triple mutant, bts-3 had similar concentrations of Zn in roots and shoots, but significantly higher concentrations of Mn in both tissues (Supplemental Figure 3A). In comparison with our in vivo imaging of Zn and Mn accumulation in shoots, we found that like the triple mutant, bts-3 had Zn enrichment in the veins, hydathodes, and at trichome bases (Figure 3). bts-3 trichomes had higher levels of Mn compared to trichomes of the triple mutant (Figure 3). In seeds, bts-3 had significantly higher concentrations of Mn and Zn compared to wild type (Supplemental Figure 3C). We note that concentrations of Mn and Zn in wild type seeds were different for seeds shown in Supplemental Figure 3B compared to Supplemental Figure 3C. This is likely due to variation in metal content of the soil and/or water, as these experiments were performed independently.

bts-3 is sensitive to Fe supply, but thrives in Fe-deficient conditions

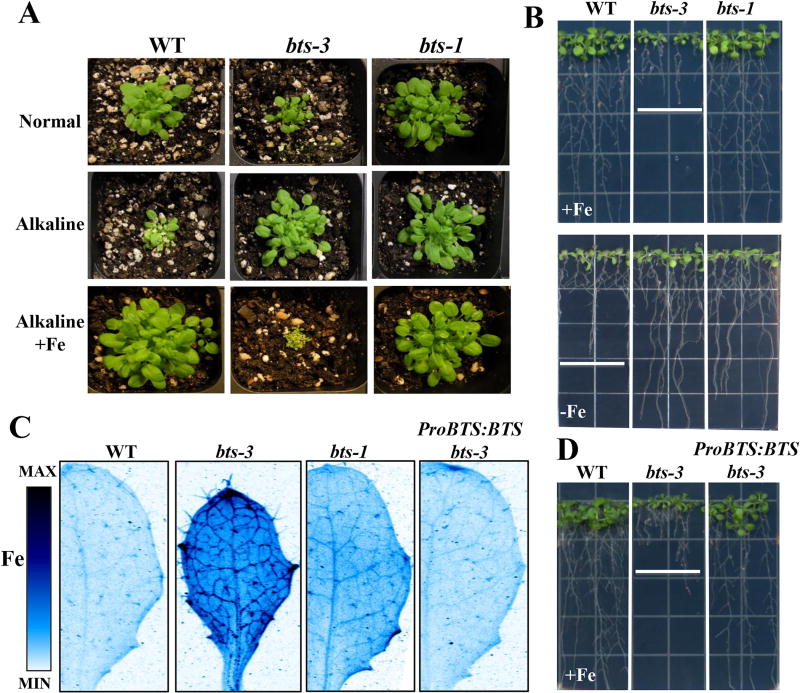

We next examined the effect of increased Fe accumulation in bts-3 plants grown under Fe-deficient and Fe-sufficient conditions. When bts-3 plants were grown on normal, Fe-sufficient soil, they were smaller than wild type and bts-1 plants (Figure 5A). However, when plants were grown on Fe-deficient alkaline soil, both bts-1 and bts-3 plants were larger and greener than wild type, which is small and chlorotic. The chlorosis that developed in wild type plants grown on alkaline soil could be rescued by watering plants with exogenous Fe. However, when bts-1 and bts-3 plants were watered with the same amount of Fe, bts-3 plants did not grow beyond the seedling stage, while bts-1 plants were visibly unaffected by Fe addition. In addition, we observed that bts-3 had visibly shorter roots and small shoots compared to wild type plants grown on Fe-sufficient plates (Figure 5B). Although our bulk and imaging analyses of Fe revealed increased shoot Fe concentrations of bts-1 plants grown under Fe-sufficient conditions (Fig 2C & Figure 5C), bts-1 did not display the short root phenotype, highlighting the unique phenotype of bts-3 (Figure 5B, See also Supplemental Figure 2B for comparison to previously discussed mutants of this study). On the other hand, in Fe-deficient conditions, bts-3 grew longer roots than wild type (Figure 5A, Supplemental Figure 2A), similar to bts-1 mutants.

Figure 5. bts-3 is tolerant to Fe-deficient growth conditions, but sensitive to Fe sufficient conditions and this phenotype can be complemented by BTS expression.

A. Plants were grown for 2 weeks on normal, alkaline, and alkaline +Fe soil. B. Plants were grown vertically for 5 days on B5 medium and then transferred to +Fe or −Fe medium for 7 days. C. SXRF scans showing Fe localization in leaf #5 of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium and then transferred to +Fe medium for 3 days. ProBTS:BTS bts-3 is the complementation line where the BTS gene driven by its own promoter is expressed in the bts-3 mutant. D. Plants were grown vertically for 5 days on B5 medium and then transferred to +Fe or −Fe medium for 7 days.

We could restore to wild type levels bts-3 Fe sensitivity, leaf size, and Fe levels/localization when we transformed the mutant with a complementation construct containing the wild type Col-0 allele of BTS driven by its native promoter, which we named ProBTS:BTS bts-3 (Figure 5C–D). This complementation line confirmed that the recessive mutation in BTS is responsible for the Fe-related phenotypes of bts-3. Mn and Zn were also restored to wild type levels and distribution patterns in complemented lines (Supplemental Figure 4).

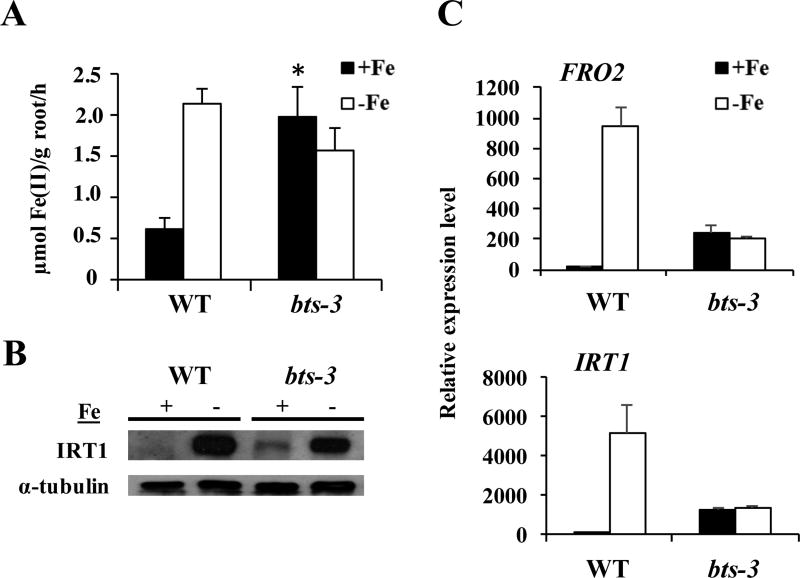

bts-3 roots exhibit the Strategy I Fe deficiency response regardless of Fe growth conditions

Because bts-3 accumulates more Fe than wild type, experiences Fe toxicity when grown under Fe-sufficient conditions, and thrives in Fe-deficient conditions, we hypothesized that bts-3 has a constitutively active Fe deficiency response. At the transcriptional level, bts-3 exhibits increased expression of FRO2 and IRT1 in Fe-sufficient conditions compared to WT and decreased expression in Fe-deficient conditions compared to WT (Figure 6A). Assays of ferric-chelate reductase activity showed that unlike wild type, where significant Fe reduction occurred only in Fe-deficient conditions, bts-3 reduced Fe3+ regardless of Fe status (Figure 6B). We also examined ferric chelate reductase activity in the bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 Fe accumulating triple mutant; although we see an increase in ferric chelate reductase activity in Fe-deficient conditions compared to wild type, there is no increase in Fe reduction in the triple mutant in Fe-sufficient conditions compared to wild type (Supplemental Figure 5). By western blotting, we showed that in wild type, IRT1 protein is only present in Fe-deficient conditions (Figure 6C). In bts-3 however, IRT1 protein accumulation occurs in Fe-sufficient conditions as well as in Fe-deficient conditions. Although this IRT1 accumulation in bts-3 plants grown under Fe-sufficient conditions is aberrant compared to wild type, IRT1 protein levels still exhibit Fe regulation because concentrations in Fe-deficient conditions are higher than concentrations in Fe-sufficient conditions.

Figure 6. The Strategy I Fe deficiency response is on under +Fe conditions in bts-3.

A. qPCR of FRO2 and IRT1 expression in roots of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium and then transferred to +Fe or −Fe medium for 3 days. Expression is relative to EF1α. Error bars represent SE (n=3).

B. Root ferric chelate reductase assay of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium before transfer to +Fe or −Fe medium for 3 days. *p<0.05 comparison between genotypes on +Fe conditions (Student’s t-test). Error bars indicate SE (n=3).

C. Representative IRT1 western blot of roots of plants as grown in panel A. α-tubulin was used as a loading control.

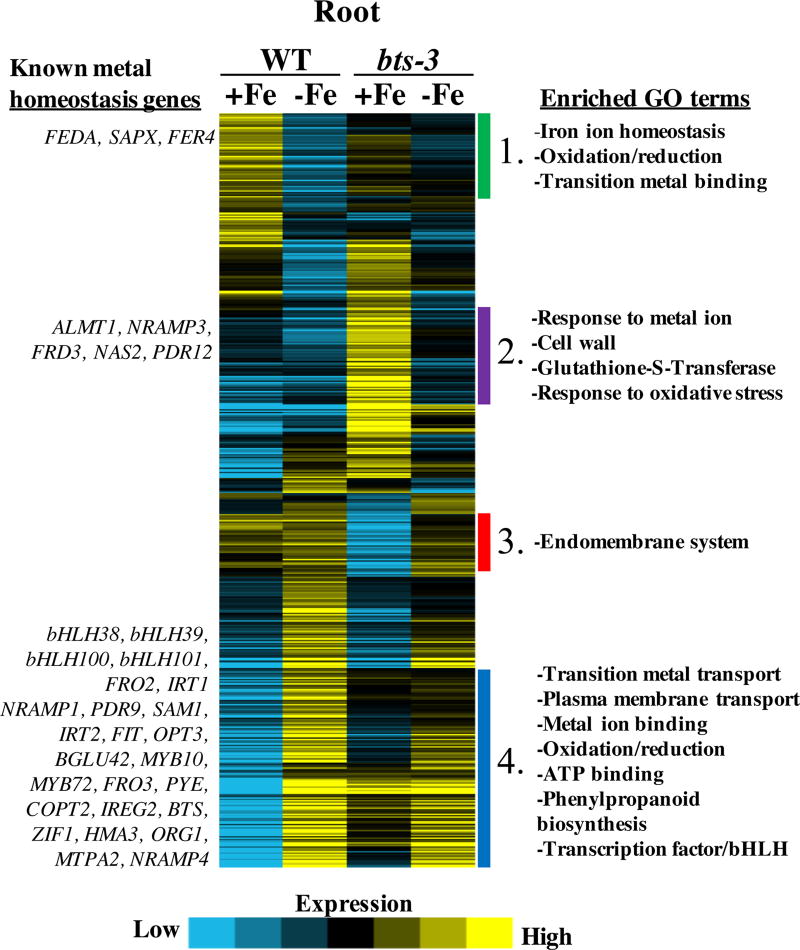

The bts-3 transcriptome varies dramatically from wild type

Because we found the Fe uptake response to be active in bts-3 roots regardless of Fe status, we wanted to understand at what level BTS might be acting, i.e. how upstream BTS acts and if BTS misregulation affects only a subset or multiple subsets of Fe-regulated genes. We were also interested in studying the transcriptome of the bts-3 mutant to determine how high/toxic Fe concentrations influence gene expression. To address these questions, we performed a microarray analysis comparing roots of wild type to bts-3 plants exposed to either Fe-sufficient or Fe-deficient growth conditions. We performed hierarchical clustering analysis on genes that were at least 1.5-fold upregulated or downregulated by Fe in either wild type or mutant. From top to bottom of heat map (Figures 7), four major defined subsets of genes were found in the cluster analyses: 1) genes which were more highly expressed in Fe-sufficient conditions compared to Fe-deficient conditions in wild type, 2) genes which were more highly expressed in bts-3 in Fe-sufficient conditions compared to all other genotypes/treatments, 3) genes which were expressed at lower levels in bts-3 Fe-sufficient conditions compared to other genotypes/treatments, and 4) genes which were more highly expressed in Fe-deficient conditions compared to Fe-sufficient conditions in wild type (Figure 7). We also performed Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis on each of these subsets to understand general features of BTS misregulation42, 43. We will briefly discuss major findings of each subset that are most relevant to our understanding of the role of BTS in Fe homeostasis.

Figure 7. Heat map of genes regulated by Fe in roots of wild type and bts-3 plants.

Microarray analysis of plants grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium and then transferred to +Fe or −Fe medium for 3 days. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed on genes which were 1.5 fold up or down regulated in response to Fe treatment in either genotype. Subsets 1–4 are numbered and enriched GO terms (right) and known metal homeostasis genes (left) are shown. The heat map was made with Java TreeView and GO terms predicted by DAVID 6.742, 43, 60.

Subset 1: Genes upregulated in Fe-sufficient wild type roots exhibited reduced expression in Fe-sufficient bts-3 roots

The subset of genes that were more highly expressed in the roots in Fe-sufficient conditions compared to Fe-deficient conditions in wild type were enriched in the following GO terms: Fe ion homeostasis, oxidation/reduction, and transition metal binding, In general, expression of these genes was not increased to reflect higher Fe levels in bts-3 (Figure 7). Included in this subset of genes were FERREDOXIN (FEDA), STROMAL ASCORBATE PEROXIDASE, (SAPX), and FERRITIN, (FER4) (encoding the major Fe storage protein, FER). Although bts-3 roots contained significantly more Fe than wild type roots in Fe-sufficient conditions, expression of many Fe sufficiency induced genes within this subset did not increase accordingly and were actually reduced compared to wild type. When plants were grown on Fe-deficient medium, expression of the genes within this subset was low in wild type roots, but slightly increased in bts-3 roots, which corresponded to the higher Fe concentration in bts-3 roots compared to wild type roots under Fe deficiency. However, bts-3 roots grown under Fe deficiency still contained more Fe than wild type roots under Fe sufficiency, and expression of these genes did not reach wild type levels. As a whole, the bts-3 root did not display an Fe-sufficient gene expression profile that corresponded simply with its Fe status.

Subsets 2 and 3: High concentrations of Fe in bts-3 roots corresponded with major transcriptional remodeling in Fe-sufficient conditions

There were a large number of genes that did not exhibit strong changes in expression levels in response to Fe treatment in wild type and were expressed at similar levels to wild type in bts-3 grown under Fe-deficient conditions but had increased expression in bts-3 grown under Fe-sufficient conditions (Figure 7, Subset 2). Enriched GO terms included response to metal ion, cell wall, glutathione-S-transferases, and response to oxidative stress. Included in this subset were known metal homeostasis genes, including genes encoding Fe transporters called NATURAL RESISTANCE-ASSOCIATED MACROPHAGE PROTEIN 3 (NRAMP3) and FERRIC REDUCTASE DEFECTIVE 3 (FRD3), an Al transporter ALUMINUM-ACTIVATED MALATE TRANSPORTER 1 (ALMT1), a Pb transporter PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE 12 (PRD12), and the gene encoding the enzyme for synthesis of the Fe chelator nicotianamine, NICOTIANAMINE SYNTHASE 2 (NAS2).

Subset 3 includes genes that were relatively unchanged by Fe status in wild type and expressed at similar levels to wild type in bts-3 Fe-deficient plants, but significantly downregulated in bts-3 Fe-sufficient roots (Figure 7). The significantly enriched GO term in this subset was endomembrane system.

Subset 4: bts-3 roots expressed Fe deficiency responsive genes regardless of Fe status

In subset 4, many genes that were induced only in Fe-deficient conditions in wild type were expressed in bts-3 roots grown under both Fe regimes (Figure 7, Supplemental Figure 6A). In most cases, expression of these genes did not reach the level of induction seen in wild type Fe-deficient roots, but they were still elevated compared to wild type Fe-sufficient roots. Further, many of the Fe deficiency responsive genes exhibited dampened expression in bts-3 roots compared to wild type roots in plants grown under Fe-deficient conditions. In addition, bts-3 Fe-deficient roots showed increased expression of these genes in Fe-deficient conditions compared to bts-3 roots in Fe-sufficient conditions. Taken together, this indicates that bts-3 roots did have some ability to regulate transcription in response to Fe status, but it was still greatly perturbed compared to wild type because roots were unable to completely repress gene expression in Fe-sufficient conditions as wild type roots did. For example, two known upstream Fe deficiency responsive genes, FIT and PYE, encoding bHLH transcription factors, exhibited increased expression in bts-3 Fe-sufficient conditions compared to wild type. Similarly, other transcription factors involved in the Fe deficiency response that are normally induced only under Fe deficiency also showed expression in roots of bts-3 plants grown under Fe-sufficient conditions. These were bHLH38, bHLH39, bHLH100, bHLH101, MYB10, and MYB72. FIT is required for activation of downstream targets FRO2 and IRT1, which as previously mentioned are responsible for Fe reduction and uptake in the root. These genes were also induced in bts-3 Fe-sufficient roots. PYE targets FRO3 and ZIF1 were also constitutively activated in bts-3. The downstream targets of MYB10 and MYB72, NAS2 and BETA GLUCOSIDASE 42 (BGLU42), were also induced regardless of Fe status in the bts-3 mutant. Other Fe deficiency responsive genes that were activated in Fe-sufficient conditions in bts-3 included NRAMP1, NRAMP4, IRT2, ZIP8, COPPER TRANSPORTER 2 (COPT2), IRON REGULATED 2 (IREG2), OBP3-RESPONSIVE GENE 1 (ORG1), and HEAVY METAL ATPASE 3 (HMA3). Finally, BTS itself and BTSL1 and BTSL2 were also expressed in bts-3 roots regardless of Fe status. Only a small number of Fe deficiency responsive genes exhibited normal expression in bts-3 roots, such as At1g47400 and At3g56360, but the function of these genes is currently unknown. Select bHLH TFs were analyzed by qPCR to validate the results of the microarray (Supplemental Figure 6B).

Discussion

Characterization of BTS paralogs in the Fe deficiency response

We characterized the role of two new E3 ligases in the Fe-deficiency response, BTSL1 and BTSL2. We found that like BTS, BTSL1 and BTSL2 were expressed in roots of plants grown under Fe-deficient conditions. Single btsl1 and btsl2 mutants did not exhibit any Fe phenotypes compared to wild type, suggesting a redundant function for these two highly related E3 ligases. Because of this, we made a btsl1 btsl2 double mutant and found increased Fe levels and increased tolerance to Fe deficiency compared to wild type. To assess whether reduction of BTS expression in the previously identified bts-1 mutant could further increase Fe content and tolerance to Fe deficiency in btsl1 btsl2 plants, we created the bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 triple mutant. This triple mutant indeed exhibited a further increase in Fe levels and tolerance to Fe deficiency, without any resulting Fe toxicity. Overall, these results demonstrate the importance of these three E3 ligases in the regulation of the Fe-deficiency response. As noted, all three genes exhibited increased expression in Fe-deficient conditions compared to Fe-sufficient conditions in roots, while only BTS was significantly expressed in Fe-deficient conditions in the shoots. Future studies should further examine the unique role of BTS in shoots.

Identification of a novel BTS allele

In our screen for plants with altered Fe concentrations, we identified a bts mutant with a novel phenotype. Previous bts alleles emb2454-1 and emb2454-2 were identified in a screen for essential genes in Arabidopsis and exhibited embryo lethality and are thus putative complete loss-of-function alleles26. To date, only partial loss-of-function alleles have been used to examine the role of BTS in post-embryonic development. The bts-1 line exhibits a steady state level of BTS mRNA approximately 70% that of wild type when grown under Fe-sufficient conditions. In bts-1, normal BTS protein is predicted, but at lower levels. bts-3 has a proline to leucine mutation at amino acid 1174 in the BTS RING domain. Our data suggests this protein variant is perturbed in its function, resulting in a phenotype distinct from the reduction in function of BTS found in the bts-1 mutant. This unique mutant allowed us to further explore the role of BTS.

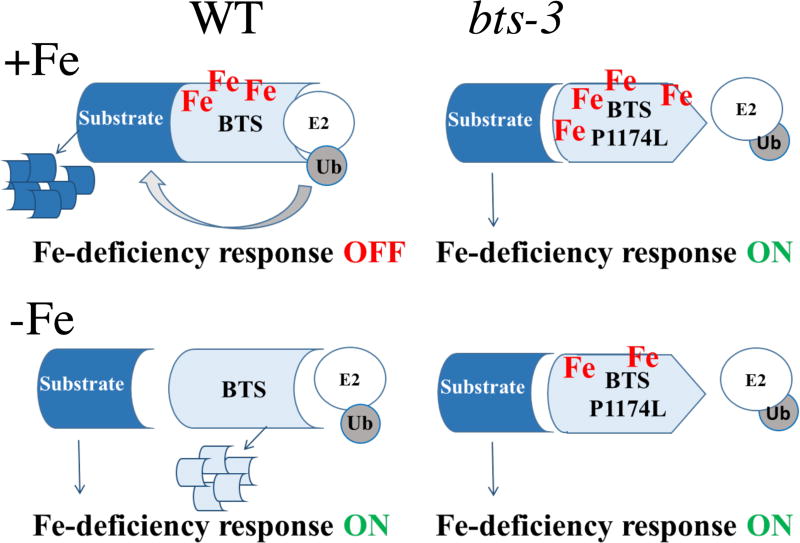

Possible models for BTS action in the root

The fact that bts-3 performs better in Fe-deficient conditions compared to wild type supports the idea that BTS is a negative regulator of the Fe deficiency response. Given that BTS is an E3 ligase, it is likely that BTS acts in the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of positive regulator(s) of the Fe deficiency response, as has been suggested previously22, 23, 25. Because BTS is an E3 ligase containing Fe-binding hemerythrin domains, we were interested in whether it acts in a similar manner to the Fe sensor identified in mammals, FBXL5. FBXL5 mRNA exhibits constitutive expression, but FBXL5 protein stability is controlled by Fe binding to the hemerythrin domains, where Fe binding stabilizes FBXL5 protein so that it can assemble with other subunits to form a complete SCF ubiquitin ligase and perform its function to ubiquitinate IRP2, leading to proteasomal degradation of IRP244, 45. In low Fe conditions, the hemerythrin domain is destabilized, resulting in FBXL5 degradation. If BTS acts in an analogous manner, Fe binding to hemerythrin domains would stabilize BTS protein, allowing for its activity in Fe-sufficient conditions (Figure 8). If target proteins are positive regulators of the Fe deficiency response, BTS could degrade these regulators when Fe becomes available after a period of Fe deficiency. The expression of BTS in Fe-deficient conditions would allow for a quick transition to Fe availability via Fe-mediated BTS protein stabilization. This could allow a rapid “switching off” of the Fe deficiency response when Fe uptake is no longer needed. In a scenario where BTS protein is mutated so that it is unstable and/or enzymatically inactive, as we believe to be the case in bts-3, a loss of ubiquitin ligase activity would result in lack of degradation of target proteins. Notably, there is strong support in the literature that the Pro to Leu change renders BTS P1174L incapable of interacting with its partner E2 enzyme because the conserved Pro has previously been identified as a residue important for this interaction in specific E2–E3 pairs46–51. This hypothesis is outlined in the model shown in Figure 8. Lack of degradation and resulting accumulation of positive regulators of the Fe deficiency response would result in a constitutive activation of the Fe deficiency response and excessive Fe uptake and resulting toxicity, as we see in bts-3 (Figure 7). This can also explain why bts-3 performed better than wild type in Fe-deficient conditions. Because bts-3 plants always take in Fe, even when there is sufficient Fe available for growth, they have stored Fe available when faced with low Fe conditions.

Figure 8. Model of BTS activity in roots of wild type vs. bts-3.

In wild type, Fe binding via HHE domains may stabilize BTS protein, allowing for assembly of E3 ligase machinery and subsequent target degradation. If the target is a positive regulator of the Fe deficiency response, the Fe deficiency response is turned off. In −Fe conditions, lack of Fe binding to HHE domains may lead to BTS protein degradation and accumulation and action of positive regulators of the Fe deficiency response. In bts-3, if the mutation prevents interaction with E2 enzymes, BTS protein cannot act as an E3 ligase, regardless of Fe status. In this case, its target would always be able to induce the Fe deficiency response.

Although protein levels and ubiquitination status of putative BTS targets have not been studied in bts mutants in planta, protein interaction studies and in vitro cell-free degradation experiments suggest that BTS targets may include bLH104, bHLH115, and ILR320, 23. bHLH104 and ILR3 have been shown to be positive regulators of the Fe deficiency response because loss-of-function mutants of these genes are sensitive to Fe-deficient conditions22. Further, these transcription factors have been shown to directly bind to promoters and influence expression of Fe deficiency responsive genes: bHLH38, bHLH39, bHLH100, bHLH101, and PYE22. We show that in bts-3 roots, these genes and others are expressed regardless of Fe status, supporting the hypothesis that BTS acts upstream to control expression of these genes. As mentioned previously, bHLH1b subgroup transcription factors can form dimers with FIT. We demonstrated that downstream targets of FIT, IRT1 and FRO2, are constitutively expressed and their protein products function to reduce and transport Fe into the root irrespective of Fe status of the plant (Figure 6, Figure 7).

Besides the possibility that BTS functions in a similar manner to FBXL5 with Fe binding to hemerythrin domains leading to protein stability (Figure 8), another study suggests the opposite is true. Protein stability assays using a wheat germ in vitro translation system suggest that BTS is less stable in the presence of Fe and thus the authors propose that BTS is active in Fe-deficient conditions, when BTS gene expression is induced23. This in vitro data further suggests that this Fe-dependent destabilization is dependent on specific Fe binding residues within the hemerythrin domains. However, MG132 proteasomal inhibitor sensitivity of this putative protein destabilization was not shown and thus it is difficult to conclude whether BTS degradation is occurring in response to Fe or whether Fe simply negatively regulates the translation of BTS protein in the wheat germ extract system. The authors of this study suggest that if BTS is more stable in Fe-deficient conditions, BTS acts under these conditions to “fine-tune” regulators of the Fe deficiency response23. A fine-tuning capability may serve to inhibit excessive Fe accumulation by preventing uncontrolled action of positive regulators of the Fe deficiency response. It is well known that Fe levels are tightly controlled because excess Fe can be very toxic to plants and therefore, this idea of fine-tuning is plausible. Alternatively, BTS may function in the constitutive turnover of positive regulators of the Fe deficiency response in order to keep them “fresh” so they can continually bind to target promoters to activate Fe deficiency responsive genes when processive transcriptional cycles are needed The requirement for “fresh” transcription factor production to replace “fatigued” transcription factors to promote continuous gene expression has been suggested for FIT protein regulation52. Alternatively, constant degradation of positive regulators by BTS may be necessary to ensure that once synthesized, positive regulators can be rapidly removed upon Fe resupply to prevent excess accumulation.

Unfortunately, we and others have been unable to detect full-length BTS protein in Fe-sufficient vs. Fe-deficient conditions in planta, making it difficult to conclude how BTS protein stability/activity is physiologically regulated by Fe availability23.

Conclusions

Considering the models discussed, if a plant is reduced in its ability to fine-tune or appropriately regulate protein stability of positive regulators of the Fe deficiency response in Fe-deficient conditions, an increased activation of the Fe deficiency response and resulting increased tolerance to Fe-deficient conditions may occur. Our bts-1, btsl1 btsl2, and bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 mutant phenotypes seem to fit this scenario. Because they probably do not completely lack their BTS E3 ligase activity due to the presence of some full-length BTS transcript in these mutants, we propose they retain some capacity to negatively regulate the Fe deficiency response. Proper balance of both positive and negative regulation of the Fe deficiency response is essential, especially from an applied perspective. The triple bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 mutant we created represents what we consider an ideal Fe accumulator: it takes in more Fe than wild type to allow for enhanced growth and tolerance to Fe deficiency, but still retains the capacity to sufficiently repress Fe uptake in Fe-sufficient growth conditions to avoid toxicity.

BTS orthologs are found across many plant species including crop plants such as rice and soybean and thus represent a potential target for enhancing tolerance to Fe deficiency and increasing Fe bioavailability for human consumption. In rice, RNAi knockdown of BTS orthologs, the HRZs, was demonstrated to increase tolerance to growth on Fe-deficient calcareous soils and increase Fe concentration in seeds without a yield penalty30. Besides genetic knockdowns and modifications, perhaps natural variants of these genes in crop species may be identified and used in traditional breeding efforts to generate cultivars with more Fe. We hope that the work described here will lead to greater understanding of plant Fe homeostasis to inform efforts for improved crops.

Experimental Methods

Plant growth conditions

For plate grown plants, seeds were surface sterilized and stratified for three days at 4°C in the dark. Gamborg’s B5 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) was supplemented with 1mM MES, 0.5% sucrose, 0.6% type M agar, and adjusted to pH 5.8. +Fe and −Fe plates were made with macronutrients and micronutrients at 2 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.75 mM K2SO4, 0.65 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM KH2PO4, 10 µM H3BO3, 0.1 µM MnSO4, 0.05 µM CuSO4, 0.05 µM ZnSO4, 0.005 µM (NH3)6Mo7O24, 1mM MES, 0.6% agar, adjusted to pH 6.0 and supplemented with either 50 µM Fe(III)-EDTA for +Fe plates or 300 µM ferrozine [3-(2-pyridyl)-5,6-diphenyl-1,2,4-triazine sulfonate (HACH Chemical)] for −Fe plates as described53, 54. Alkaline soil was generated by adding approximately 7.8 gm CaO/kg soil to achieve a soil pH of 7.5–8. To supplement plants grown on alkaline soil, 500 µM FeEDDHA was added. All plants in this study were grown at 21°C under a 16 hour light/8 hour dark cycle.

Mutant lines

BTS/At3g18290 (bts-1), BTSL1/At1g74770 (btsl1), and BTSL2/At1g18910 (btsl2) T-DNA insertion lines were obtained from ABRC (SALK_016526, SALK_015054, SAIL_615_HO1, respectively). Homozygous lines were identified using gene-specific primers and a T-DNA specific border primer. Location of T-DNA insertions are shown in Supplemental Figure 1. bts-3 was identified in an EMS mutagenesis screen and backcrossed twice. btsl1 btsl2 was generated by crossing btsl and btsl2 and identifying a homozygous double mutant. btsl1 btsl2 was crossed with bts-1 to generate the bts-1 btsl1 btsl2 mutant and a homozygous triple mutant was identified.

Array Mapping

The Fe over accumulating mutant was crossed to Ler and F2 plants were scored for sensitivity to Fe sufficient growth conditions. Two pools of plants were created, one with the Fe sensitivity mutant phenotype and one with the wild type phenotype. DNA extracted from the two pools was hybridized to the AtSNPTile array and the mapping was performed as described in Becker et al.39. The array files are available on GEO.

Plasmid construction and plant transformation

The endogenous promoter complementation line was generated by amplifying the region including 1.9 kb upstream of the BTS ATG and the entire BTS gene and is named ProBTS:BTS bts-3. This construct was subcloned into pCR8 (Invitrogen) and finally into pEARLEY GATE 301 using Gateway LR Clonase II (Invitrogen). Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 was transformed with the above construct and bts-3 plants were transformed using the floral dip method55. Transformants were isolated using BASTA selection at 25 mg/mL.

Chlorophyll assay

Plants were grown for 10 days on B5 medium and then transferred to −Fe medium for 7 days. The shoots were harvested and assayed for chlorophyll concentration by heating plants in 95% ethanol at 80°C as previously described56.

Elemental concentration analysis

Root and shoot tissues were collected from plants and to remove trace surface metals, tissues were incubated for 5 mins in 5 mM CaSO4, 5 mins in 10 mM EDTA, and rinsed with deionized water. Root and shoot tissues were dried before analysis by incubation in open Eppendorf tubes at 70°C for 24 hours. Seeds were harvested when fully dried. Dry tissues (shoot, root and seed) were transferred into Pyrex test tubes (16 × 100 mm). After weighing the appropriate number of samples (these masses were used to calculate the rest of the sample masses after Danku et al. 57, trace metal grade nitric acid (J. T. Baker Instra-Analyzed; Avantor Performance Materials; Scientific & Chemical Supplies Ltd, Aberdeen, UK) spiked with indium internal standard was added to the tubes (1.00 mL). They were then digested in dry block heaters (DigiPREP MS, SCP Science; QMX Laboratories, Essex, UK) at 115°C for 4 hours. The digested samples were diluted to 10.0 mL with 18.2 MΩcm Milli-Q Direct water (Merck Millipore, Watford, UK) and aliquots transferred to 96-well deep well plates using adjustable multichannel pipette (Rainin; Anachem Ltd, Luton, UK) for analysis. Elemental analysis was performed with an inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) (PerkinElmer NexION 300D equipped with Elemental Scientific Inc. autosampler and Apex HF sample introduction system; PerkinElmer LAS Ltd, Seer Green, UK and Elemental Scientific Inc., Omaha, NE, USA, respectively) in the standard mode. Twenty elements (Li, B, Na, Mg, P, S, K, Ca, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, As, Se, Rb, Sr, Mo, and Cd) were monitored. Separate liquid reference materials composed of pooled samples of the digested tissues (shoot, root and seed) were prepared before the beginning of sample runs and were used throughout the samples runs. They were run after every ninth sample in all ICP-MS sample sets, respectively, to correct for variation between and within ICP-MS analysis runs57. Sample concentrations were calculated using external calibration method within the instrument software. The calibration standards (with indium internal standard and blanks) were prepared from single element standards (Inorganic Ventures; Essex Scientific Laboratory Supplies Ltd, Essex, UK) solutions.

Synchrotron X-Ray Fluorescence

Two-dimensional SXRF analysis was performed at various X-ray microprobe beamlines: X26A (leaves in Figure 2B, Figure 3, and Supplemental Figure 4) and X27A (dry seeds in Figure 2E) of National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS), Beamline 2–3 of Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) (roots, leaves, and siliques of Figure 3B–D), XFM of the Australian Synchrotron, (dry seeds in Figure 4F), and beamline 2-ID-D of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) (Leaf tissue sections of Figure 4E). More details and metadata are found in the Supplemental Methods.

Real-time quantitative PCR

RNA was prepared from plants grown on B5 medium for 2 weeks before transfer to +Fe or −Fe media for 3 days. RNA extraction was performed using TRIzol® (Life Technologies) and the RNEasy mini kit and protocol (Qiagen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on Step One Plus Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems Version 2.2.3) using SYBR Premix ExTaq reagents and protocol (Takara). Each sample was run in triplicate. Relative transcript levels were calculated by normalizing to EF1a housekeeping expression.

Microarray analysis

RNA was extracted from three biological replicates as described above from root tissue from plants grown on B5 medium for two weeks before transfer to either +Fe or −Fe medium for 3 days. RNA was labeled and hybridized to the Arabidopsis Gene 1.0 ST Arrays (Affymetrix) by the Dartmouth Genomics and Microarray Laboratory. Raw data was RMA normalized using Affymetrix Expression Console software and downstream analyses were performed using BRB-Array Tools Version 4.2.1. BRB-ArrayTools is an integrated software package for the analysis of DNA microarray data which was developed by the Biometric Research Branch of the Division of Cancer Treatment & Diagnosis of the National Cancer Institute under the direction of Dr. Richard Simon. Differentially expressed genes were identified between two classes using a random-variance t-test with a p-value cutoff of 0.01. The random-variance t-test is an improvement over the standard separate t-test as it permits sharing information among genes about within-class variation without assuming that all genes have the same variance58. We also used a cutoff of 1.5 fold change up or down in response to Fe treatment for either wild type or bts-3. Biological replicates for root and shoot arrays were averaged for analysis of gene expression in each tissue. Hierarchical clustering was employed to generate heat maps for subsets of significant genes using the open source software Cluster/Treeview59, 60. GO term enrichment using the DAVID Go Ontology program Functional Annotation Clustering tool using an enrichment cutoff of >1.3 as previously described42, 43. Microarray data was made publically available in the GEO repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo).

Ferric chelate reductase assay

Plants were grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium and then transferred to either +Fe or −Fe media for 3 days. 5 plants were pooled for root Fe(III)-chelate reductase activity measurements, as previously described54.

Protein isolation and immunodetection

Wild type and bts-3 plants were grown for 2 weeks on B5 medium and transferred to +Fe or −Fe media for 3 days. Total protein was extracted from roots using protein extraction buffer: 50 mM Tris, pH8, 5% glycerol, 4%SDS, 1%PVPP, 2 mM Pefabloc (Roche), 1× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche). SDS-PAGE followed by western electroblotting was performed and blots were probed with an IRT1 antibody or α-tublulin antibody (AbCam).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession numbers At3g18290 (BTS), At1g74770 (BTSL1), and At1g18910 (BTSL2).

Supplementary Material

Significance to Metallomics.

Iron (Fe) deficiency commonly limits plant growth. If Fe homeostasis were understood, it might be feasible to engineer plants better able to grow in soils now considered marginal and to increase crop biomass on soils now in cultivation. Furthermore, as most people rely on plants as their dietary source of Fe, plants that serve as better sources of this essential nutrient would improve human health. In this study, we characterize the role of three closely related negative regulators of the Fe deficiency response. A triple mutant has increased tolerance to Fe deficient growth conditions and increased Fe accumulation without resulting toxicity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brett Lahner and Elana Yakubov for performing the ICP-MS analysis and plant growth and harvesting, respectively, for the screen of EMS mutagenized plants. In memoriam, we thank John Danku for all the ICP-MS analyses included in this manuscript. Microarray analysis was carried out at the Geisel School of Medicine in the Genomics Shared Resource, which was established by equipment grants from the NIH and NSF and is supported in part by a Cancer Center Core Grant (P30CA023108) from the National Cancer Institute. We thank Amanda Socha for help with RNA extraction for microarray analysis and Carol Ringelberg for her help with microarray data analysis. We thank Suzana Car for her help with SXRF experiments at NSLS. We thank Sue Wirick and William Rao for their help at X26A and Ryan Tappero for his help at X27A. X26A is supported by the Department of Energy (DOE) - Geosciences (DE-FG02-92ER14244 to The University of Chicago - CARS). Use of the NSLS was supported by DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886. X27A is supported in part by the U.S. Department of Energy - Geosciences (DE-FG02-92ER14244 to The University of Chicago - CARS) and Brookhaven National Laboratory– Department of Environmental Sciences. Use of the NSLS was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886. We thank Sam Webb and Benjamin Kocar for their help at Beamline 2–3 at SSRL. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH. We thank Suna Kim and Louisa Howard for the help with preparing leaf sections for Figure 4E. We thank Tony Lanzirotti for his help at APS. Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.We thank Martin DeJonge and Daryl Howard for their help at XFM. This research was undertaken on the XFM beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, Victoria, Australia. This work was supported by grants to M.L.G. from the US National Science Foundation (DBI 0701119, IOS-0919941), the US National Institutes of Health (R01GM078536), the US Department of Energy (DE-FG-2-06ER15809), and the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P42 ES007373) and an NSF Plant Genome grant (DBI 0701119) to D.E.S. and M.L.G. M.N.H. was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, a Nell Mondy Fellowship from Sigma Delta Epsilon-Graduate Women in Science, and a Dartmouth Graduate Alumni Research Award.

References

- 1.Hindt MN, Guerinot ML. Getting a sense for signals: Regulation of the plant iron deficiency response. BBA Mol. Cell. Res. 2012;1823:1521–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santi S, Schmidt W. Dissecting iron deficiency-induced proton extrusion in Arabidopsis roots. New Phytol. 2009;183:1072–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson NJ, Procter CM, Connolly EL, Guerinot ML. A ferric-chelate reductase for iron uptake from soils. Nature. 1999;397:694–697. doi: 10.1038/17800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez-Celma J, Lin WD, Fu GM, Abadia J, Lopez-Millan A, Schmidt W. Mutually exclusive alterations in secondary metabolism are critical for uptake of insoluble iron compounds by Arabidopsis and. Medicago truncatula, Plant Physiol. 2013;162:1473–1485. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.220426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid NB, Giehl RF, Doll S, Mock HP, Strehmel N, Scheel D, Kong X, Hider RC, von Wiren N. Feruloyl-CoA 6'-Hydroxylase1-dependent coumarins mediate iron acquisition from alkaline substrates in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014;164:160–172. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.228544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt H, Günther C, Weber M, Spörlein C, Loscher S, Böttcher C, Schobert R, Clemens S. Metabolome analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana roots identifies a key metabolic pathway for iron acquisition. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e102444. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fourcroy P, Siso-Terraza P, Sudre D, Saviron M, Reyt G, Gaymard F, Abadia A, Abadia J, Alvarez-Fernandez A, Briat JF. Involvement of the ABCG37 transporter in secretion of scopoletin and derivatives by Arabidopsis roots in response to iron deficiency. New Phytol. 2014;201:155–167. doi: 10.1111/nph.12471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eide D, Broderius M, Fett J, Guerinot ML. A novel iron-regulated metal transporter from plants identified by functional expression in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:5624–5628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vert G, Grotz N, Dedaldechamp F, Gaymard F, Guerinot ML, Briat J-F, Curie C. IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and plant growth. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1223–1233. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriques R, Jásik J, Klein M, Martinoia E, Feller U, Schell J, Pais MS, Koncz C. Knock-out of Arabidopsis metal transporter gene IRT1 results in iron deficiency accompanied by cell differentiation defects. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002;50:587–597. doi: 10.1023/a:1019942200164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varotto C, Maiwald D, Pesaresi P, Jahns P, Francesco S, Leister D. The metal ion transporter IRT1 is necessary for iron homeostasis and efficient photosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2002;31:589–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colangelo EP, Guerinot ML. The essential bHLH protein FIT1 is required for the iron deficiency response. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3400–3412. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.024315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jakoby M, Wang H-Y, Reidt W, Weissharr B, Bauer P. FRU(BHLH029) is required for induction of iron mobilization genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2004;577:528–534. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan YX, Zhang J, Wang DW, Ling HQ. AtbHLH29 of Arabidopsis thaliana is a functional ortholog of tomato FER involved in controlling iron acquisition in strategy I plants. Cell Res. 2005;15:613–621. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H-Y, Klatte M, Jacoby M, Baumlein H, Weisshaar B, Bauer P. Iron deficiency-mediated stress regulation of four subgroup Ib bHLH genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2007;226:897–908. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0535-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan Y, Wu H, Wang N, KLi J, Zhao W, Du J, Wang D, Ling H-Q. FIT interacts with AtbHLH38 and AtbHLH39 in regulating iron uptake gene expression for iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Cell Res. 2008;18:385–397. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang N, Cui Y, Liu Y, Fan H, Du J, Huang Z, Yuan Y, Wu H, Ling HQ. Requirement and functional redundancy of Ib subgroup bHLH proteins for iron deficiency responses and uptake in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant. 2013;6:503–513. doi: 10.1093/mp/sss089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer CM, Hindt MN, Schmidt H, Clemens S, Guerinot ML. MYB10 and MYB72 are required for growth under iron-limiting conditions. Plos Genet. 2013;9:e1003953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamioudis C, Hanson J, Pieterse CM. β-Glucosidase BGLU42 is a MYB72-dependent key regulator of rhizobacteria-induced systemic resistance and modulates iron deficiency responses in Arabidopsis roots. New Phytol. 2014;204:368–379. doi: 10.1111/nph.12980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long TA, Tsukagoshi H, Busch W, Lahner B, Salt DE, Benfey PN. The bHLH transcription factor POPEYE regulates response to iron deficiency in Arabidopsis roots. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2219–2236. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.074096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rampey RA, Woodward AW, Hobbs BN, Tierney MP, Lahner B, Salt DE, Bartel B. An Arabidopsis basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper protein modulates metal homeostsis and auxin conjugate responsiveness. Genetics. 2006;174:1841–1857. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.061044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Liu B, Li M, Feng D, Jin H, Wang P, Liu J, Xiong F, Wang J, Wang H-B. The bHLH Transcription Factor bHLH104 Interacts with IAA-LEUCINE RESISTANT3 and Modulates Iron Homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2015;3:787–805. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.132704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selote D, Samira R, Matthiadis A, Gillikin JW, Long TA. Iron-binding E3 ligase mediates iron response in plants by targeting basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:273–286. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.250837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Zhang H, Ai Q, Liang G, Yu D. Two bHLH transcription factors, bHLH34 and bHLH104, regulate iron homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:2478–2493. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matthiadis A, Long TA. Further insight into BRUTUS domain composition and functionality. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016;11:e1204508. doi: 10.1080/15592324.2016.1204508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McElver J, Tzafrir I, Aux G, Rogers R, Ashby C, Smith K, Thomas C, Schetter A, Zhou Q, Cushman MA. Insertional mutagenesis of genes required for seed development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2001;159:1751–1763. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.4.1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kersey P, Allen J, Christensen M, Davis P, Falin L, Grabmueller C, Hughes D, Humphrey J, Kerhornou A, Khobova J. Ensembl Genomes 2013: scaling up access to genome-wide data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:546–552. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marchler-Bauer A, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Geer LY, Geer RC, He J, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lanczycki CJ, Lu F, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Wang Z, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Zheng C, Bryant SH. CDD: NCBI's conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D222–226. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobayashi T, Nagasaka S, Senoura T, Itai RN, Nakanishi H, Nishizawa NK. Iron-binding haemerythrin RING ubiquitin ligases regulate plant iron responses and accumulation. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2792. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim SA, Punshon T, Lanzirotti A, Li L, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, Kaplan J, Guerinot ML. Localization of iron in Arabidopsis seed requires the vacuolar membrane transporter VIT1. Science. 2006;314:1295–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.1132563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Korshunova YO, Eide D, Clark WG, Guerinot ML, Pakrasi HB. The IRT1 protein from Arabidopsis thaliana is a metal transporter with a broad substrate range. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;40:37–44. doi: 10.1023/a:1026438615520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahner B, Gong J, Mahmoudian M, Smith EL, Abid KB, Rogers EE, Guerinot ML, Harper JF, Ward JM, McIntyre L, Schroeder JI, Salt DE. Genomic scale profiling of nutrient and trace elements in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1215–1221. doi: 10.1038/nbt865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baxter I, Hosmani PS, Rus A, Lahner B, Borevitz JO, Muthukumar B, Mickelbart MV, Schreiber L, Franke RB, Salt DE. Root suberin forms an extracellular barrier that affects water relations and mineral nutrition in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000492. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tian H, Baxter IR, Lahner B, Reinders A, Salt DE, Ward JM. Arabidopsis NPCC6/NaKR1 is a phloem mobile metal binding protein necessary for phloem function and root meristem maintenance. Plant Cell. 2010;22:3963–3979. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.080010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chao D-Y, Gable K, Chen M, Baxter I, Dietrich CR, Cahoon EB, Guerinot ML, Lahner B, Lu S, Markham JE, Morrissey J, Han J, Gupta SDSD, Harmon JM, Jaworski JG, Dunn TM, Salt DE. Sphingolipids in the root play an important role in regulating the leaf ionome in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2011;23:1061–1081. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.079095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borghi M, Rus A, Salt DE. Loss-of-function of constitutive expresser of Pathogenesis Related Genes5 affects potassium homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamiya T, Borghi M, Wang P, Danku JM, Kalmbach L, Hosmani PS, Naseer S, Fujiwara T, Geldner N, Salt DE. The MYB36 transcription factor orchestrates Casparian strip formation. Proc. Natl. Sci. U.S.A. 2015;112:10533–10538. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507691112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker A, Chao DY, Zhang X, Salt DE, Baxter I. Bulk segregant analysis using single nucleotide polymorphism microarrays. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15993. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chao DY, Silva A, Baxter I, Huang YS, Nordborg M, Danku J, Lahner B, Yakubova E, Salt DE. Genome-wide association studies identify Heavy Metal ATPase3 as the primary determinant of natural variation in leaf cadmium in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chao DY, Chen Y, Chen J, Shi S, Chen Z, Wang C, Danku JM, Zhao FJ, Salt DE. Genome-wide association mapping identifies a new arsenate reductase enzyme critical for limiting arsenic accumulation in plants. PLoS Biol. 2014;12:e1002009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salahudeen AA, Thompson JW, Ruiz JC, Ma HW, Kinch LN, Li Q, Grishin NV, Bruick RK. An E3 ligase possessing an iron-responsive hemerythrin domain is a regulator of iron homeostasis. Science. 2009;326:722–726. doi: 10.1126/science.1176326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vashisht AA, Zumbrennen KB, Huang X, Powers DN, Durazo A, Sun D, Bhaskaran N, Persson A, Uhlen M, Sangfelt O, Spruck C, Leibold EA, Wohlschlegel JA. Control of iron homeostasis by an iron-regulated ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2009;326:718–721. doi: 10.1126/science.1176333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deshaies RJ, Joazeiro CA. RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:399–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.101807.093809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng N, Wang P, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Structure of a c-Cbl–UbcH7 Complex: RING domain function in ubiquitin-protein ligases. Cell. 2000;102:533–539. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mace PD, Linke K, Feltham R, Schumacher FR, Smith CA, Vaux DL, Silke J, Day CL. Structures of the cIAP2 RING domain reveal conformational changes associated with ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) recruitment. J Biol. Chem. 2008;283:31633–31640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yin Q, Lamothe B, Darnay BG, Wu H. Structural basis for the lack of E2 interaction in the RING domain of TRAF2. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10558–10567. doi: 10.1021/bi901462e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin Q, Lin SC, Lamothe B, Lu M, Lo YC, Hura G, Zheng L, Rich RL, Campos AD, Myszka DG, Lenardo MJ, Darnay BG, Wu H. E2 interaction and dimerization in the crystal structure of TRAF6. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:658–666. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Spratt DE, Julio Martinez-Torres R, Noh YJ, Mercier P, Manczyk N, Barber KR, Aguirre JD, Burchell L, Purkiss A, Walden H, Shaw GS. A molecular explanation for the recessive nature of parkin-linked Parkinson’s disease. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1983. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sivitz A, Grinvalds C, Barberon M, Curie C, Vert G. Proteasome-mediated turnover of the transcriptional activator FIT is required for plant iron-deficiency responses. Plant J. 2011;66:1044–1052. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marschner H, Römheld V, Ossenberg-Neuhaus H. Rapid method for measuring changes in pH and reducing processes along roots of intact plants. Z Pflanzenphysiol. 1982;105:407–416. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yi Y, Guerinot ML. Genetic evidence that induction of root Fe(III) chelate reductase activity is necessary for iron uptake under iron deficiency. Plant J. 1996;10:835–844. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.10050835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harmutk L. Chlorophyls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;34:350–382. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Danku JC, Lahner B, Yakubova E, Salt D. In: Plant Min. Nutr. 17. Maathuis FJM, editor. Vol. 953. Humana Press; 2013. pp. 255–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wright GW, Simon RM. A random variance model for detection of differential gene expression in small microarray experiments. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2448–2455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO, Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saldanha AJ. Java Treeview--extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3246–3248. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.