Abstract

Objectives

Approximately one in five stroke survivors suffer from difficulties with speech reception in noise, despite normal audiometry. These deficits are treatable with personal frequency-modulated systems (FMs). This study aimed to evaluate long-term benefits in speech reception in noise, after daily 10-week use of personal FMs, in non-aphasic patients with stroke with auditory processing deficits.

Design

This was a prospective non-randomised controlled trial study. Patients were allocated to an intervention care group or standard care subjects group according to their willingness to use the intervention or not.

Setting

Tertiary care setting.

Participants

Nine non-aphasic subjects with ischaemic stroke, normal/near-normal audiometry and auditory processing deficits and with reported difficulties understanding speech in background noise were recruited in the subacute stroke stage (3–12 months after stroke).

Interventions

Four patients (intervention care subjects) used the FMs in their daily life over 10 weeks. Five patients (standard care subjects) received standard care.

Primary outcome measures

All subjects were tested at baseline (visit 1) and 10 weeks later (visit 2) on a sentences in noise test with the FMs (aided) and without the FMs (unaided).

Results

Speech reception thresholds showed clinically and statistically significant improvements in intervention but not in standard care subjects at 10 weeks in aided and unaided conditions.

Conclusions

10-week use of FMs by adult patients with stroke may lead to benefits in unaided speech in noise perception. Our findings may indicate auditory plasticity type changes and require further investigation.

Trial registration number

Pre-results; NCT02889107.

Keywords: auditory plasticity, frequency modulated systems, speech in noise, auditory processing

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to investigate long-term benefits of frequency-modulated systems use in stroke subjects in order to determine potential value in running a large-scale intervention trial.

Recruited patients had detailed auditory assessment.

The study has small numbers and lacks randomisation.

Extent of lesion effects was not investigated.

Introduction

Stroke can affect all levels of the auditory pathway1 and manifests with pure-tone detection deficits on audiometry,2 3 auditory processing deficits4 5 and perceptual difficulties in the domains of speech, sound recognition and localisation.6 Approximately one in five of stroke survivors report severe difficulties with speech recognition in the presence of background noise, despite the presence of normal audiometry.7 These deficits are treatable with personal frequency-modulated (FM) systems, with a robust immediate improvement of 9 dB in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)when using the FM system.7 This is a clinically significant improvement as 6 dB is the cut-off value for the patient to seek clinical intervention.8

Personal FM systems are wireless listening devices that pick up the speaker's voice and transmit it to a receiver in the listener's ear, thus reducing the negative effects of noise, distance and reverberation. FM systems are used to improve speech in noise perception in patients with listening difficulties due to disordered auditory processing, such as children with developmental disorders9 10 and adults with neurological disorders11 12 including stroke7 with good immediate benefits. Long-term benefits of FM systems have predominantly been investigated on paediatric populations. Children with disordered auditory processing who used FMs 5 months in the classroom showed an improved unaided (ie, with no FM device) speech in quiet performance by 3.8 dB, suggesting the possibility of bottom-up driven auditory neuroplasticity;9 however, due to the lack of controls, maturation effects could not be entirely excluded. Dyslexic children who used FMs over 1 year similarly showed improved phonological awareness and reduced variability of subcortical responses to sound.10

The potential neuroplasticity-type benefits of prolonged FM system use are of particular interest for stroke survivors with acquired auditory processing deficits. The central auditory nervous system maintains the capacity to be altered in response to auditory stimulation or deprivation throughout life.13 Language-based rehabilitation leads to plasticity-type benefits for aphasic stroke subjects,14 and it would be reasonable to expect similar benefits in less impaired (ie, non-aphasic) patients with stroke with speech reception impairments who receive an intervention that promotes better access to speech.

The present study thus aimed to evaluate the potential benefits in speech perception of personal FM systems, when used daily over 10 weeks by non-aphasic patients with stroke with auditory processing deficits, in order to investigate whether plasticity occurs after prolonged use of FM systems.

We hypothesised that improvement in unaided speech in background noise performance, shown on a behavioural task, would occur in patients with stroke who used the FM systems for a period of time, but not in a control group of patients with stroke who did not use these and received standard care.

Methods

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02889107).

Study design

This study was conducted prospectively with a non-randomised controlled design. We further aimed to establish how many eligible patients would be willing to use the FMs daily, in order to inform a subsequent trial, the SD of the primary outcome measure, in order to calculate sample size for a subsequent trial and the number of patients willing to use this intervention, follow-up rate and adherence/compliance rate to the intervention.

Participants of our previous study7 were asked whether they would be willing to use the FM systems at home for 10 weeks. Four out of nine (44%) agreed to use the FM (subjects 1, 4, 6 and 9—table 1) and formed the intervention subjects group, while five out of nine (56%) who did not wish to use the FM but were willing to come back for a reassessment 10 weeks later formed the standard care group (subjects 2, 3, 5, 7 and 8—table 1).

Table 1.

Lesion description, age, sex, PTA (average in dB HL at 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000 Hz) and HFA (average in dB HL at 4000, 6000 and 8000 Hz)

| Participant | Age | Sex | PTA | HFA | Lesion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (1) | 64 | M | 22.5 | 28.1 | Paramedial right thalamus |

| I (9) | 32 | M | 15 | 11.6 | Right insula infarct |

| I (4) | 52 | M | 25 | 26 | Left medulla oblongata, occipital lobe, hippocampus and right cerebellum infarct |

| I (6) | 32 | M | 5.5 | 6.6 | Right temporal lobe infarct |

| SC (3) | 44 | M | 8.3 | 11.6 | Right putamen/corona radiata infarct |

| SC (5) | 53 | F | 25 | 28.3 | Right superior parietal lobule infarct |

| SC (2) | 24 | M | 18.3 | 16.6 | Left frontotemporal and insula infarct |

| SC (7) | 78 | M | 25 | 30.1 | Left occipito-temporal infarct |

| SC (8) | 64 | M | 22.5 | 28.1 | Right temporal infarct |

A Mann-Whitney U test showed no statistically significant difference for age, PTA and HFA of intervention and the standard care group.

dB, decibel; F, female; HFA, high-frequency average; HL, hearing level; I, intervention; M, male; PTA, pure-tone average; SC, standard care.

Participants

All recruited subjects were right-handed adults (age range 24–78 years) with a clinical history of ischaemic stroke verified by brain MRI in the subacute stroke stage (table 1). They had normal/near-normal pure-tone audiogram (PTA) average thresholds (better than 25 dB hearing level) and reported difficulties on the speech in noise subscale of the Amsterdam Inventory for Auditory Disability (AIAD)(z score >2).6 They had abnormal performance (in one ear or both) in the speech in babble15 and in at least one more non-speech auditory processing test.16 17 No subject had severe aphasia (cut-off of 93.8 on the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB) test18), significant psychiatric illnesses, other neurological disorders except stroke or severe concurrent medical illnesses.

Baseline assessments

All participants had a brain MRI within 48 hours after the stroke. They had audiological and other baseline assessments over a single test session after recruitment, at 3–12 months after stroke (subacute stage), that included:

Outcome assessment tools, testing methods and outcome measures

Outcome assessments were conducted during visit 1 within 1 week from the baseline assessments, and visit 2 at 10 weeks later. The outcome assessment tool was the Bamford-Kowal-Bench (BKB) sentence test20 presented against a 20-talker babble noise, conducted within the ‘crescent of sound’ booth.21 Repetition of at least three keywords per sentence is required for correct performance. The level of the sentences and the background noise are adaptively varied to estimate the speech reception threshold (SRT) which is the SNR for 50% correct performance.

The AB-York Crescent of Sound is a sound-attenuated booth with audio stands in a semicircular arc at a 1.45° m radius from the participant's chair.21

The BKB sentences were presented from the loudspeaker positioned at 0° azimuth to the participant with the babble coming:

from the same loudspeaker at 0°at the front;

from the loudspeaker 90° to the left (−90°);

from the loudspeaker 90° to the right (+90°).

The test was conducted with the participant using the FM (aided condition) or not using the FM (unaided condition). Testing for each of the three locations was repeated twice. Each participant completed 12 runs of the sentences in noise test as follows:

Aided condition: The FM transmitter microphone was positioned on a stand 12 cm in front from the 0° azimuth loudspeaker and the participant wore the personal binaural FM systems in their ears. Two runs of the test were conducted for the babble noise coming from each of the three locations: straight-ahead (0° azimuth), left (−90°) and right (+90°) loudspeaker.

Unaided condition: The same protocol as per the aided condition with the babble noise coming from each of three locations ×2 runs, but with the participant not wearing the binaural FM systems.

The order of the tests was done randomly across participants. A different sentence list was used in each test run.

The primary outcome measure for this test was the SRT obtained for speech and noise presented from 0° (S0°N0°), speech presented at 0° and noise 90° to the left (S0°N−90°) and speech presented at 0° and noise 90° to the right (S0°N+90°).

Intervention

Intervention subjects

At visit 1, all four intervention subjects were provided with the Phonak iSense Micro receiver and the ZoomLink+ transmitter. The FM receiver gain is varied proportionally to the noise level at the microphone of the FM transmitter. The default FM receiver gain is set to +10 for noise up to 57 dB sound pressure level (SPL) and with a maximum gain of +24 for noise of ∼75 dB SPL.22 When speech is not present at the FM microphone, the receiver is muted.

Intervention subjects were instructed how to check function of the system and asked to change batteries every 2 weeks. They were advised to use the FM system for 7 days a week and about 6 hours daily over the next 10 weeks. Patients were asked to use the FM at home with family members and with multiple media devices such as music players, radio, television and their computer. They were also asked to use the FM in social situations such as family outings (with their significant others wearing the microphone), restaurants, public houses as well as small group meetings at work and so on. Written instruction was provided together with standard listening strategies handout.

Standard care subjects

At visit 1, all standard care subjects were given an oral explanation of their listening difficulties and a standard listening strategies advice handout. They were retested at visit 2, 10 weeks later from visit 1.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using STATA 11. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted. In addition, bootstrapping procedures, which facilitate parametric statistical analyses on non-normally distributed data sets, were used to address the limitation of the small sample size. Such procedures estimate statistical parameters based on a large number of random samples (with replacement) from an original data set. Bootstrapped ANOVA and ANCOVA were thus conducted23 24 to determine a statistically significant difference between the intervention and standard care groups on the SRTs in noise at the baseline time point and at 10 weeks. Bootstrapped z-statistic and p values (bias corrected, accelerated with 1000 replications) were calculated. ANCOVA was performed to control for age and side of lesions, and to examine the differences between the intervention and standard care groups on postintervention scores, while controlling for baseline scores of the same measure. The independent variable, study group, included two levels: intervention group and standard care group. The dependent variable was the SRT in noise scores and covariates were age and side of lesion.

A Mann Whitney test was used to compare the primary outcomes between the intervention and standard care groups at baseline and 10 week time point.

Results

There were no drop outs to the study, and all recruited subjects came back for retest 10 weeks later. All four intervention subjects complied with the daily use of the FMs. According to their own reports the FMs were used for a minimum of 4 hours every day.

The simple and bootstrapped one-way ANOVA showed no statistically significant difference between the intervention and standard care groups on the SRTs in noise at visit 1 time point. There was no difference between groups with respect to the SRTs in noise when the babble was presented at either the left or the right side, in aided and unaided condition (tables 2 and 3). A series of simple and bootstrapped univariate ANOVAs were calculated to examine the differences between the intervention and comparison groups on visit 2 (post intervention) scores. Simple and bootstrapped ANOVA showed a statistically significant improvement in SRT in noise when the noise was coming from left and right for aided and unaided conditions at visit 2 time point in the intervention group compared with those who received standard care. However, when a series of simple and bootstrapped univariate ANCOVA were calculated to control for baseline outcomes, age and side of lesions, a statistically significant improvement in SRT in noise was observed only when the noise was coming from left for aided and unaided conditions at visit 2 time point in the intervention group compared with those who received standard care (tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

ANCOVA and ANOVA. Intervention versus standard care

| ANCOVA and ANOVA Intervention vs standard care |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | MS |

F-statistic |

p-Value |

||||

| ANCOVA | ANOVA | ANCOVA | ANOVA | ANCOVA | ANOVA | ||

| S0N−90 unaided | Visit 1 | 9.6 | 0.13 | 1.1 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.91 |

| Visit 2 | 47.8 | 140.4 | 5.5 | 21.2 | 0.04* | 0.002* | |

| S0N+90 unaided | Visit 1 | 5.1 | 14.0 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 0.33 | 0.06 |

| Visit 2 | 12.9 | 37.2 | 3.1 | 11.6 | 0.13 | 0.01* | |

| S0N−90 aided | Visit 1 | 5.9 | 0.12 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.60 | 0.90 |

| Visit 2 | 57.76 | 149.2 | 5.2 | 13.1 | 0.05* | 0.008* | |

| S0N+90 aided | Visit 1 | 3.6 | 8.2 | 0.3 | 0.89 | 0.83 | 0.37 |

| Visit 2 | 42.5 | 121.1 | 1.88 | 7.1 | 0.24 | 0.03* | |

The analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model included age and side of stroke as covariates.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; MS, mean square.

*(in bold) statistically significant at p at or < 0.05

Table 3.

Bootstrapped ANCOVA and ANOVA. Intervention versus standard care

| Bootstrapped ANCOVA and ANOVA Intervention vs standard care |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bootstrapped SE |

Bootstrapped z-statistic |

Bootstrapped p-value |

|||||

| Condition | ANCOVA | ANOVA | ANCOVA | ANOVA | ANCOVA | ANOVA | |

| S0N−90 unaided | Visit 1 | 4.4 | 2.5 | 0.1 | −0.02 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| Visit 2 | 4.1 | 1.7 | −1.8 | −4.4 | 0.05* | 0.000* | |

| S0N+90 unaided | Visit 1 | 4.1 | 1.1 | −0.6 | −2.2 | 0.6 | 0.07 |

| Visit 2 | 8.1 | 2.4 | −0.5 | −3.2 | 0.6 | 0.002* | |

| S0N−90 aided | Visit 1 | 6.6 | 1.9 | −0.2 | 0.13 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Visit 2 | 4.9 | 1.1 | −2.0 | −6.8 | 0.04* | 0.000* | |

| S0N+90 aided | Visit 1 | 5.5 | 1.8 | −0.2 | −1.05 | 0.8 | 0.3 |

| Visit 2 | 8.7 | 3.3 | −0.9 | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.02* | |

The analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model included age and side of stroke as covariates.

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

*(in bold) statistically significant at p at or < 0.05

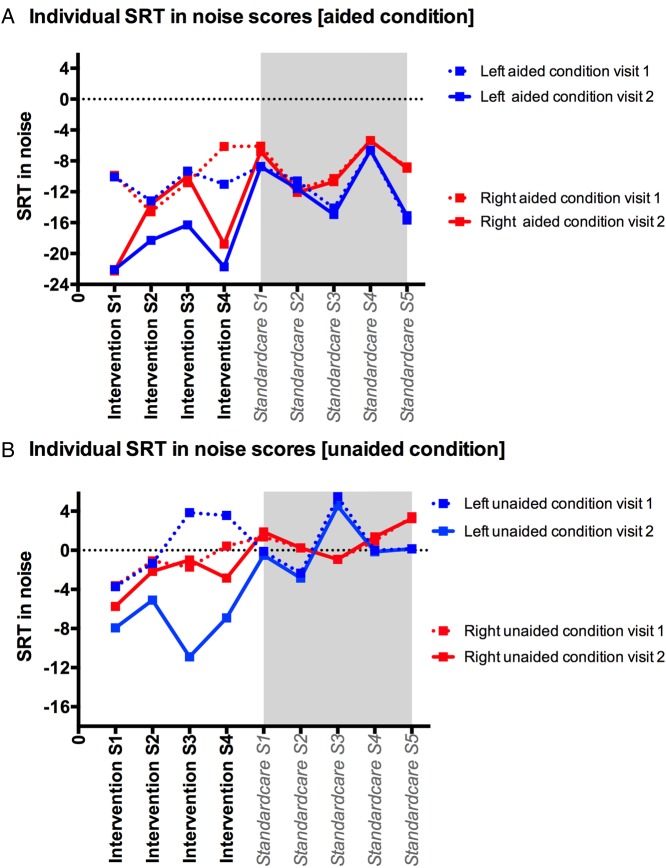

Figure 1 shows the SRT individual scores for intervention and standard care subjects at visit 1 and visit 2, in aided and unaided conditions.

Figure 1.

(A and B) Speech reception threshold (SRT) at visit 1 and visit 2 in aided (A) and unaided conditions (B) for noise coming 90° to the left and for noise coming 90° to the right. SRT, speech reception threshold; S, subject.

A series of Mann-Whitney U tests were performed in the different speaker-testing positions, these were for baseline visit and 10-week visit to assess differences in the primary outcomes of SRT in noise between intervention and standard care groups. The results are summarised in table 4.

Table 4.

The results of the Mann-Whitney U test for baseline and 10-week speech reception threshold in noise

| Condition | Group | Intervention | Standard care | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (variance) | ||||

| S0N−90 unaided | Baseline | 1.1 (13.9) | −1.4 (2.8) | 0.81 |

| 10 week | −7.4 (5.8) | −0.15 (7.2) | 0.01* | |

| S0N+90 unaided | Baseline | −1.4 (2.8) | 0.9 (2.6) | 0.054 |

| 10 week | −2.5 (4.8) | 1.3 (2.5) | 0.01* | |

| S0N−90 aided | Baseline | −10.5 (2.8) | −10.6 (13.9) | 1.0 |

| 10 week | −20 (7.8) | −11.6 (14.0) | 0.01* | |

| S0N+90 aided | Baseline | −10.3 (12.1) | −8.7 (7.1) | 0.32 |

| 10 week | −16.2 (29.6) | −8.9 (7.5) | 0.05 |

*Denotes significance (p-value at or <0.01 was accepted to indicate statistically significant results).

Discussion

Forty-four per cent of eligible stroke subjects for the FM intervention (ie, with preserved peripheral hearing but with speech in noise reported difficulties and test deficits) were willing to use the FM systems daily. In addition to the immediate benefit in terms of improved speech in noise reception threshold in the aided condition (with FM system), the intervention subjects showed a further substantial benefit for speech in noise test performance even in the unaided condition after a period of 10 weeks daily FM use in the versus no benefit in the standard care subjects. The benefit exceeded 6 dB which is the cut-off value for patients to clinically seek such intervention8 when the noise was on their left side. The study has small case numbers, and findings ought to be interpreted with caution. Low study numbers affect precision of measurements, and even a nominally statistically significant finding may not reflect a true effect.25 Furthermore, groups were not randomly allocated, thus being prone to selection bias, while willingness for randomisation and the factors influencing patient preference and thus group allocation26 were not determined. An additional limitation was that we could not investigate the effect of extent of brain lesion on results. However, the study purpose was to determine if there is potential value in running a large-scale intervention trial.

Taking the methodological caveats into consideration, it would be useful to consider the study's findings implications. Improved SRTs when using the FM system after prolonged daily FM use could be attributed to acclimatisation-type effects (ie, getting used to the device effects), such as improved perception of high-frequency phonemes over time.27 However, such benefits—if any—tend to be small.28 The findings of a robust improvement in SRTs in the unaided condition in the FMs intervention group may thus indicate that a brain plasticity mechanism is involved.

In the presence of normal pure-tone audiometric thresholds and in the absence of aphasia, our stroke subjects had degraded speech encoding (as indicated by their abnormal speech in babble test results) and self-reported difficulties with speech in noise due to their-stroke related auditory processing deficits as evidenced by their abnormal results in other non-speech auditory processing tests. This resulted in impaired identification of lexical items in stored knowledge. Additionally, the increased effort required for speech discrimination because of background noise would be expected to reduce their information processing capacity and thus the short-term memory required for speech recall and understanding.29 It has been proposed30 that each level of the auditory cortical hierarchy attempts to predict the sensory representation of the speech signal of interest at the level below by transmitting a top-down prediction, with prediction error information (ie, the incoming signal differing from the prediction) transmitted back to the higher level, leading to a recalibration of the higher level representations. This updating of predictions at higher level is heavily dependent on attention mechanisms influenced by the degree of salience of the stimulus and the listening context.31 It is thus postulated that in our patients with stroke, auditory processing deficits reduced the clarity of incoming speech and the brain (attention) responds by decreasing the sensory precision or postsynaptic gain. This was to some extent redressed when stroke subjects used the FM system within the crescent of sound, as demonstrated by the immediate improvement in SRTs in the aided versus the unaided condition in visit 1. It may further be postulated that prolonged use of the FMs over 10 weeks, with active listening to salient speech (assuming that cases used the FM system to listen to speech of interest to them) led to attention optimising the synaptic gain that represents the precision of the bottom-up sensory information (prediction error) during the hierarchical inference process within the auditory brain. Candidate brain regions where this effect could take place include primary auditory cortex area, or Broca's and inferior frontal gyrus, that is, the areas showing a relative specialisation for phonological encoding32 or subcortical areas, in accordance with the results of Hornickel et al.10

This is the first study to investigate potential auditory plasticity following a prolonged use of FM systems in adult patients with acquired stroke brain lesions. However, this study has methodological limitations that do not allow to draw definitive conclusions. The findings presented here should motivate further work with a larger randomised clinical trial to investigate the true effect size of prolonged FM-use benefits, the effect of type and extent of brain lesion and of cognitive and linguistic factors, as well as the mechanism for any benefits. Further research is required to look into this promising intervention that may benefit ∼17% of the stroke population.7

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants and our colleagues at Queen Square.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the design, results analysis, interpretation and write-up of the paper. NK conducted the tests. The paper was drafted by NK and D-EB, finalised by D-EB and approved by all authors.

Funding: This study was funded by the British Medical Association Helen Lawson grant. The FM systems were kindly provided by Phonak.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The National Hospital for Neurology Ethics Committee approved the study (Project number 11/0469; REC 11/LO/1675).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.3hg4k.

References

- 1.Häusler R, Levine R. Auditory dysfunction in stroke. Acta Otolaryngol 2000;120:689–703. 10.1080/000164800750000207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Formby C, Phillips DE, Thomas RG. Hearing loss among stroke patients. Ear Hear 1987;8:326–32. 10.1097/00003446-198712000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Halloran R, Worrall LE, Hickson L. The number of patients with communication related impairments in acute hospital stroke units. Int J Speech Langu Pathol 2009;11:438–49. 10.3109/17549500902741363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rey B, Frischknecht R, Maeder P, et al. Patterns of recovery following focal hemispheric lesions: relationship between lasting deficit and damage to specialized networks. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2007;25:285–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bamiou DE, Musiek FE, Stow I, et al. Auditory temporal processing deficits in patients with insular stroke. Neurology 2006;67:614–19. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000230197.40410.db [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamiou DE, Werring D, Cox K, et al. Patient-reported auditory functions after stroke of the central auditory pathway. Stroke 2012;43:1285–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.644039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koohi N, Vickers D, Chandrashekar H, et al. Auditory rehabilitation after stroke: treatment of auditory processing disorders in stroke patients with personal frequency-modulated (FM) systems. Disabil Rehabil 2016;39:586–93.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McShefferty D, Whitmer WM, Akeroyd MA. The just-meaningful difference in speech-to-noise ratio. Trends Hear 2016;20:2331216515626570 10.1177/2331216515626570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston KN, John AB, Kreisman NV, et al. Multiple benefits of personal FM system use by children with auditory processing disorder (APD). Int J Audiol 2009;48:371–83. 10.1080/14992020802687516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hornickel J, Zecker SG, Bradlow AR, et al. Assistive listening devices drive neuroplasticity in children with dyslexia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012;109:16731–6. 10.1073/pnas.1206628109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis MS, Hutter M, Lilly DJ, et al. Frequency-modulation technology as a method for improving speech perception in noise for individuals with multiple sclerosis. J Am Acad Audiol 2006;17:605–16. 10.3766/jaaa.17.8.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rance G, Corben LA, Du Bourg E, et al. Successful treatment of auditory perceptual disorder in individuals with Friedreich ataxia. Neuroscience 2010;171:552–5. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musiek FE, Shinn J, Hare C. Plasticity, auditory training, and auditory processing disorders. Semin Hear 2002;23:263–76. 10.1055/s-2002-35862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattioli F, Ambrosi C, Mascaro L, et al. Early aphasia rehabilitation is associated with functional reactivation of the left inferior frontal gyrus: a pilot study. Stroke 2014;45:545–52. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spyridakou C, Luxon LM, Bamiou DE. Patient-reported speech in noise difficulties and hyperacusis symptoms and correlation with test results. Laryngoscope 2012;122:1609–14. 10.1002/lary.23337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musiek FE, Shinn JB, Jirsa R, et al. Gin (gaps-in-noise) test performance in subjects with confirmed central auditory nervous system involvement. Ear Hear 2005;26:608–18. 10.1097/01.aud.0000188069.80699.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goll JC, Crutch SJ, Loo JH, et al. Non-verbal sound processing in the primary progressive aphasias. Brain 2010;133:272–85. 10.1093/brain/awp235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shewan CM, Kertesz A. Reliability and validity characteristics of the western aphasia battery (WAB). J Speech Hear Dis 1980;45:308–24. 10.1044/jshd.4503.308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meijer AGW, Wit HP, TenVergert EM, et al. Reliability and validity of the (modified) Amsterdam inventory for auditory disability and handicap. Int J Audiol 2003;42:220–6. 10.3109/14992020309101317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bench J, Bamford J. Speech-hearing tests and the spoken language of hearing-impaired children. London: Academic Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitterick PT, Lovett RE, Goman AM, et al. The AB-York crescent of sound: an apparatus for assessing spatial-listening skills in children and adults. Cochlear Implants Int 2011;12: 164–9. 10.1179/146701011X13049348987832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfe J, Schafer EC, Heldner B, et al. Evaluation of speech recognition in noise with cochlear implants and dynamic FM. J Am Acad Audiol 2009;20:409–21. 10.3766/jaaa.20.7.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher N, Hall P. Bootstrap algorithms for small samples. Journal of statistical planning and inference 1991;27:157–69. 10.1016/0378-3758(91)90013-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barber JA, Thompson SG. Analysis of cost data in randomized trials: an application of the non-parametric bootstrap. Stat Med 2000;19:3219–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technology Assessment 2003;27:1–173. 10.3310/hta7270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Button KS, Ioannidis JP, Mokrysz C, et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013;14:365–76. 10.1038/nrn3475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis RJ, Munro KJ. Benefit from, and acclimatization to, frequency compression hearing aids in experienced adult hearing-aid users. Int J Audiol 2015;54:37–47. 10.3109/14992027.2014.948217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dawes P, Munro KJ, Kalluri S, et al. Acclimatization to hearing aids. Ear Hear 2014;35:203–12. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3182a8eda4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabbitt PMA. Mild hearing loss can cause apparent memory failures which increase with age and reduce with IQ. Acta Otolaryngol 1991;476:167–75; discussion 176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S, Sedley W, Nourski KV, et al. Predictive coding and pitch processing in the auditory cortex. J Cogn Neurosci 2011;23:3084–94. 10.1162/jocn_a_00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feldman H, Friston KJ. Attention, uncertainty, and free-energy. Front Hum Neurosci 2010;4:215 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papoutsi M, de Zwart JA, Jansma JM, et al. From phonemes to articulatory codes: an fMRI study of the role of Broca's area in speech production. Cereb Cortex 2009;19:2156–65. 10.1093/cercor/bhn239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.