Significance

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) account for a majority of visits to hospitals and clinics in the United States and are typically caused by Gram-positive pathogens. Recently, it was discovered that Gram-positive bacteria use a unique pathway to synthesize the critical cellular cofactor heme. The divergence of the heme biosynthesis pathways between humans and Gram-positive bacteria provides a unique opportunity for the development of new antibiotics targeting this pathway. We report here the identification of a small-molecule activator of coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CgoX) from Gram-positive bacteria that induces accumulation of coproporphyrin III and leads to photosensitization of Gram-positive pathogens. In combination with light, CgoX activation reduces bacterial burden in murine models of SSTI.

Keywords: bacteria, photosensitization, CgoX, heme, antibiotic

Abstract

Gram-positive bacteria cause the majority of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), resulting in the most common reason for clinic visits in the United States. Recently, it was discovered that Gram-positive pathogens use a unique heme biosynthesis pathway, which implicates this pathway as a target for development of antibacterial therapies. We report here the identification of a small-molecule activator of coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CgoX) from Gram-positive bacteria, an enzyme essential for heme biosynthesis. Activation of CgoX induces accumulation of coproporphyrin III and leads to photosensitization of Gram-positive pathogens. In combination with light, CgoX activation reduces bacterial burden in murine models of SSTI. Thus, small-molecule activation of CgoX represents an effective strategy for the development of light-based antimicrobial therapies.

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) are responsible for a majority of visits to hospitals and clinics in the United States, accounting for ∼14 million ambulatory care visits each year (1). Furthermore, ∼10% of hospitalized patients suffer from an SSTI (1). These infections are typically caused by Gram-positive bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Propionibacterium acnes, and Bacillus anthracis, the causative agents of “staph infections,” hospital-acquired infections, acne, and cutaneous anthrax, respectively (1–4). S. aureus and P. acnes are the most prevalent causative agents of SSTIs (1–4). In fact over 90% of the world’s population will suffer from acne over the course of their lifetime, leading to annual direct costs of over $3 billion (1, 2, 5, 6). The threat of these pathogens is compounded by the tremendous rise in antibiotic resistance, reducing the efficacy of the existing antibacterial armamentarium (1, 3, 4). Identifying new drug targets to treat SSTIs is paramount to enable the development of novel therapeutics.

Heme biosynthesis is conserved across all domains of life, and heme is used for a diverse range of processes within cells. Until recently, it was thought that the heme biosynthesis pathway was conserved across all species, limiting its utility as a potential therapeutic target to treat infectious diseases. However, Dailey et al. (7, 8) discovered that Gram-positive bacteria use a distinct pathway to synthesize the critical cellular cofactor heme (Fig. 1A). Specifically, Gram-positive heme biosynthesis diverges at the conversion of coproporphyrinogen III (CPGIII) to coproporphyrin III (CPIII) through a six-electron oxidation by coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CgoX, formally known as HemY), as opposed to being converted to protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) in the classical pathway by a distinct series of enzymes (7, 9, 10). The divergence of the heme biosynthesis machinery between humans and Gram-positive bacteria provides a unique opportunity for the development of antibiotics targeting this pathway as a strategy to treat infections.

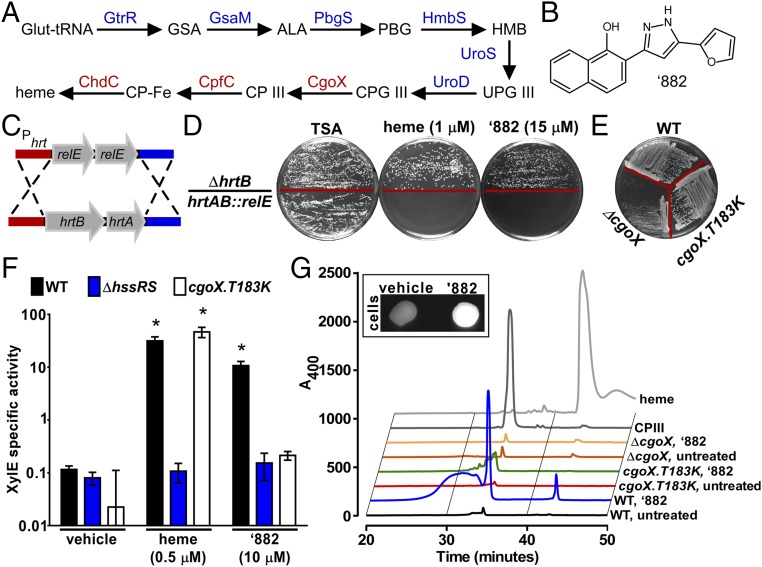

Fig. 1.

‘882 exposure increases CPIII production in S. aureus. (A) The terminal enzymes in the Gram-positive heme biosynthesis pathway (red) are distinct from other organisms. (B) ‘882 is a small molecule that increases heme biosynthesis in S. aureus (11). (C) To create a Phrt suicide strain, the hrtAB genes were replaced with two copies of the E. coli gene encoding the RNA interferase toxin RelE. (D) Upon heme or ‘882 stimulation, toxicity is induced in hrtAB::relE. (E) Strain CgoX.T183K exhibits a normal growth phenotype on tryptic soy agar (TSA), suggesting the CgoX T183K does not restrict CgoX function. (F) Strain CgoX.T183K is unresponsive to ‘882, but retains the ability to respond to heme as measured by Phrt activation. *P < 0.001 compared with vehicle treated for each strain. (G) HPLC analysis of WT, CgoX.T183K, and ΔCgoX ± ‘882. ‘882 increases CPIII production in WT cells but not in CgoX.T183K. (Inset) ‘882-induced CPIII accumulation induces fluorescence in treated cells.

Small-molecule VU0038882 (‘882) was previously identified in a screen for activators of the S. aureus heme-sensing system two-component system (HssRS) (11–13) (Fig. 1B). Upon activation, HssRS induces the expression of the heme-regulated transporter (HrtAB) to alleviate heme toxicity (11–13). HssRS activation is triggered by massive accumulation of heme in ‘882-exposed bacteria (11). In addition to activating HssRS, treatment with ‘882 induces toxicity to bacteria undergoing fermentation by impacting iron–sulfur cluster biogenesis (11, 14). Through a medicinal chemistry approach, the HssRS-activating properties of ‘882 were decoupled from its toxicity, suggesting two distinct cellular targets for this small molecule (11, 14, 15). Before this investigation, the mechanism by which ‘882 activates heme biosynthesis to trigger HssRS had not been uncovered.

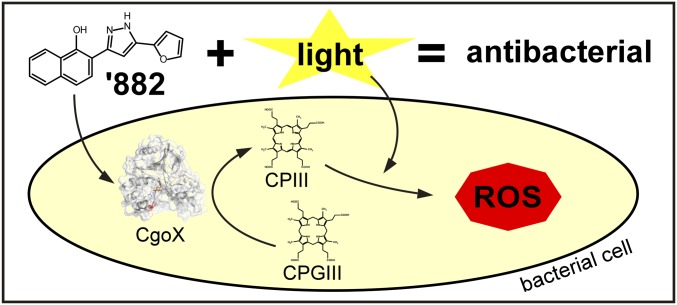

We report here the identification of the cellular target of ‘882 responsible for inducing heme biosynthesis through the use of a Phrt-driven suicide strain. ‘882 activates CgoX from Gram-positive bacteria, an enzyme essential for heme biosynthesis. Activation of CgoX induces accumulation of the product of the reaction, CPIII, a photoreactive molecule of demonstrated utility in treating bacterial infections (6, 16, 17). Photodynamic therapy (PDT) uses a photosensitizing molecule activated by a specific wavelength of light to produce reactive oxygen species that lead to cell death (6). Most US Food and Drug Administration-approved photosensitizers are aminolevulinic acid (ALA) derivatives, which serve as prodrugs through their conversion to porphyrins in the heme biosynthetic pathway (6). Through ‘882-dependent activation of CgoX, CPIII accumulates in a similar manner, inducing photosensitization specifically in Gram-positive bacteria, and ‘882-PDT reduces bacterial burden in murine models of SSTI (Fig. S1). Thus, small-molecule activation of CgoX represents a promising strategy for the development of light-based antimicrobial therapies.

Fig. S1.

Gram-positive bacteria cause the majority of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), resulting in the most common reason for clinic visits in the United States. Recently, it was discovered that Gram-positive pathogens use a unique heme biosynthesis pathway, which implicates this pathway as a target for development of antibacterial therapies. We report here the identification of a small-molecule activator of coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CgoX) from Gram-positive bacteria, an enzyme essential for heme biosynthesis. Activation of CgoX induces accumulation of coproporphyrin III and leads to photosensitization of Gram-positive pathogens. In combination with light, CgoX activation reduces bacterial burden in murine models of SSTI. Thus, small-molecule activation of CgoX represents an effective strategy for the development of light-based antimicrobial therapies.

Results

Construction of an ‘882-Responsive Suicide Strain.

To identify the target of ‘882, a suicide strain was created enabling selection of S. aureus strains that are unresponsive to ‘882. Because ‘882 is not toxic to wild-type (WT) bacteria, a genetic approach was used to engineer toxicity to S. aureus upon treatment with ‘882. S. aureus hrtAB was replaced with two copies of the gene encoding the Escherichia coli RNA interferase toxin RelE under the control of the native hrtAB promoter to inhibit growth upon activation of HssRS (Fig. 1C). Dual copies of relE were used to avoid selection of toxin-inactivating mutations. S. aureus hrtAB::relE grows equivalently to WT in the absence of heme or ‘882. Upon HssRS induction by heme or ‘882, hrtAB::relE is unable to grow (Fig. 1D). A strain lacking the hrtB permease (ΔhrtB) was used to ensure that ‘882 does not induce heme toxicity at tested concentrations. These results establish this suicide strain as a powerful tool to identify suppressor mutants unresponsive to ‘882.

Selection of ‘882-Resistant Suicide Strains.

Isolates of hrtAB::relE exhibiting spontaneous resistance to ‘882 were identified at a frequency of 0.0079%, and the stability of resistance was ensured through serial passage. Genomic DNA was isolated and the hssRS/hrtAB locus was sequenced. Whole-genome sequencing was performed on isolates lacking mutations in hssRS/Phrt to identify mutations conferring resistance to ‘882 in the hrtAB::relE strain background. This analysis revealed a T183K mutation in CgoX, an enzyme required for heme biosynthesis. The CgoX T183K mutation was reconstructed in WT S. aureus (CgoX.T183K), and this strain exhibits normal growth, suggesting the CgoX T183K mutation prevents the response of S. aureus to ‘882 without restricting heme biosynthesis, as seen in a strain lacking CgoX (ΔCgoX) (18) (Fig. 1E). In addition, the T183K mutation abolished ‘882 sensing to the same level as ΔhssRS, whereas heme sensing remained intact (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these results demonstrate that the CgoX T183K mutation prevents ‘882-induced activation of hrtAB in S. aureus.

‘882 Induces CPIII Accumulation.

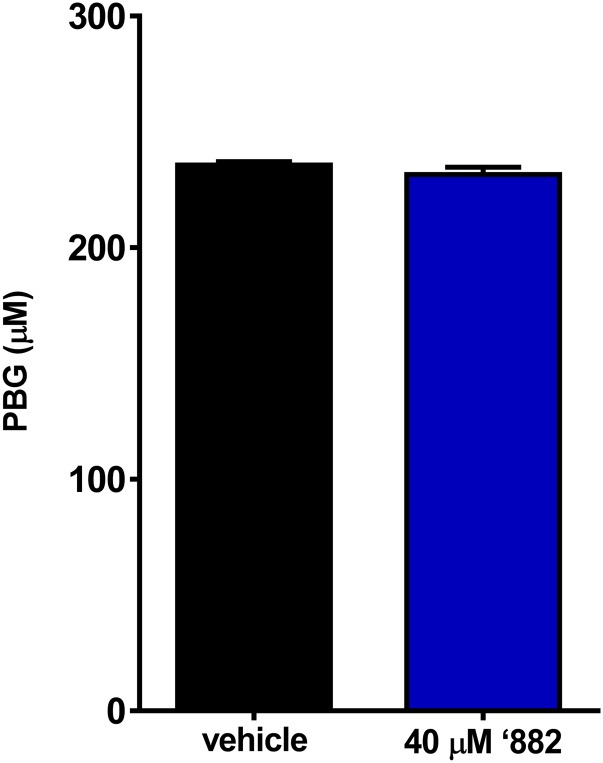

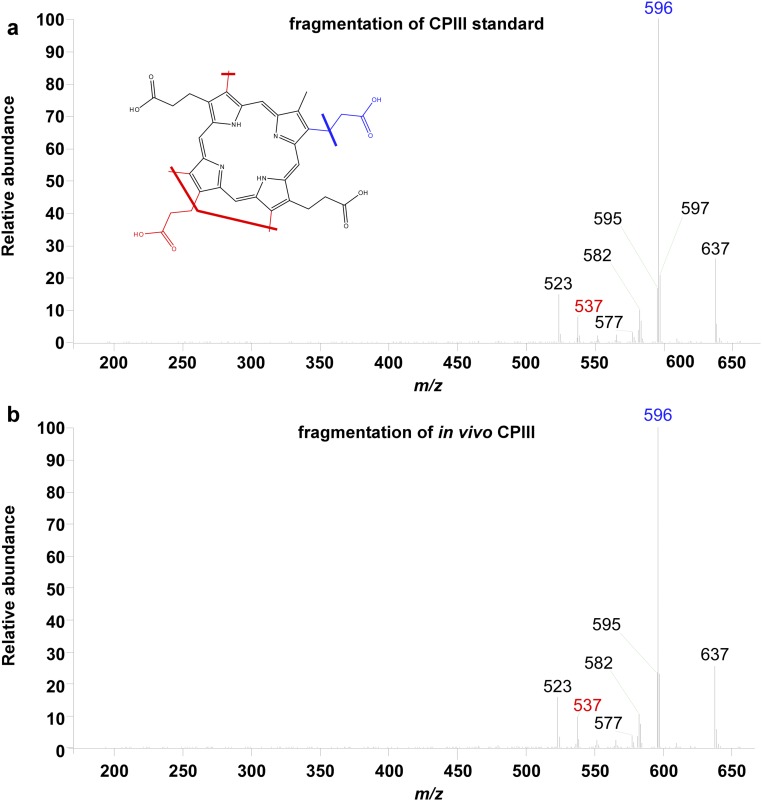

To determine the impact of ‘882 on the heme biosynthesis pathway, intermediates of heme biosynthesis were quantified following ‘882 exposure. Porphobilinogen (PBG), an early heme biosynthetic precursor, is unaffected by ‘882 (Fig. 1A and Fig. S2). In contrast, CPIII, the product of CgoX, is greatly increased following ‘882 treatment (Fig. 1 A and G). Notably, CPIII accumulation is not observed in CgoX.T183K or ΔCgoX upon ‘882 treatment (Fig. 1G). CPIII is the only fluorescent molecule in the heme biosynthesis pathway, and ‘882 exposure triggers dramatic fluorescence in S. aureus (Fig. 1G, Inset). The HPLC fraction corresponding to the elution time of the CPIII standard was analyzed by LC-MS/MS and confirmed to be CPIII (Fig. S3). These results demonstrate that ‘882 exposure leads to accumulation of CPIII in S. aureus and implicate CgoX as a candidate target of the molecule.

Fig. S2.

‘882 does not affect early heme biosynthesis. Porphobilinogen (PBG) was quantified to determine ‘882-induced effects on early heme biosynthesis intermediates. No effect on PBG was seen.

Fig. S3.

‘882 induces accumulation of CPIII. HPLC fractions containing either the CPIII standard (A) or the corresponding fraction from ‘882-treated WT cells (B) were analyzed by LC-MS/MS. MS/MS fragmentation of the peak at m/z 654.340, the mass of CPIII, is shown. The MS/MS fragmentation of this peak in both samples is nearly identical and consistent with expected major fragments, positively identifying the peak within these fractions as CPIII.

‘882 Activates CgoX from Gram-Positive Bacteria in Vitro.

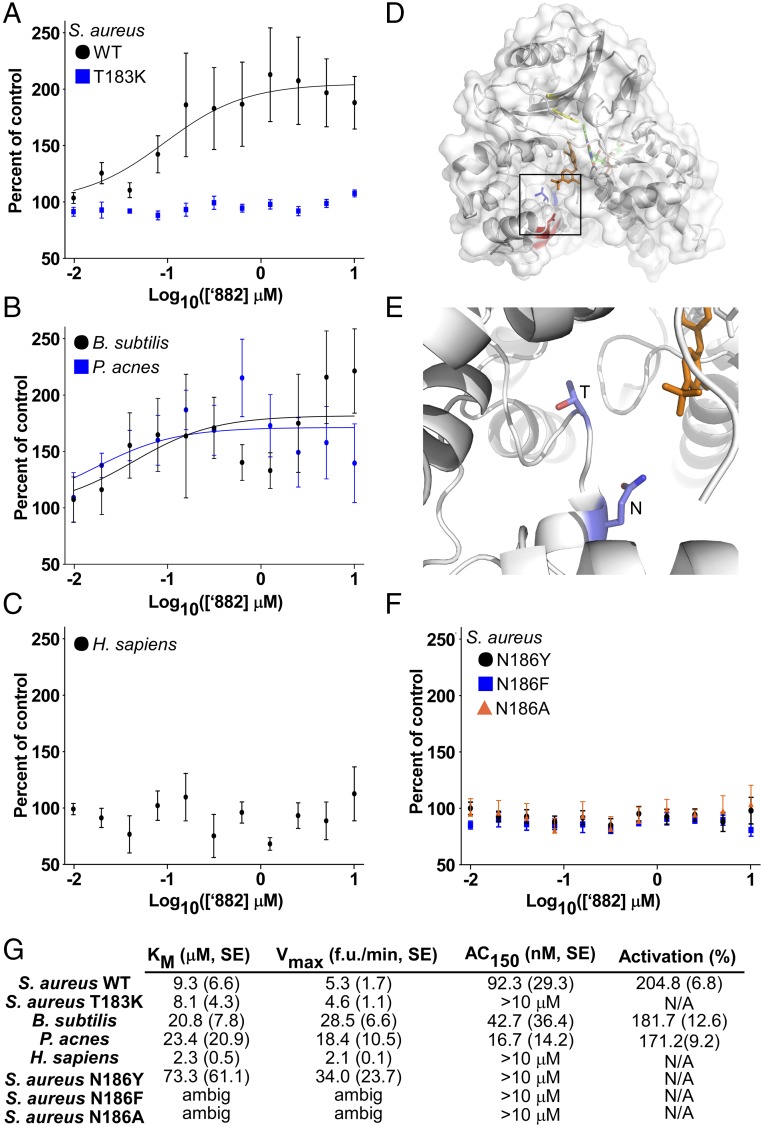

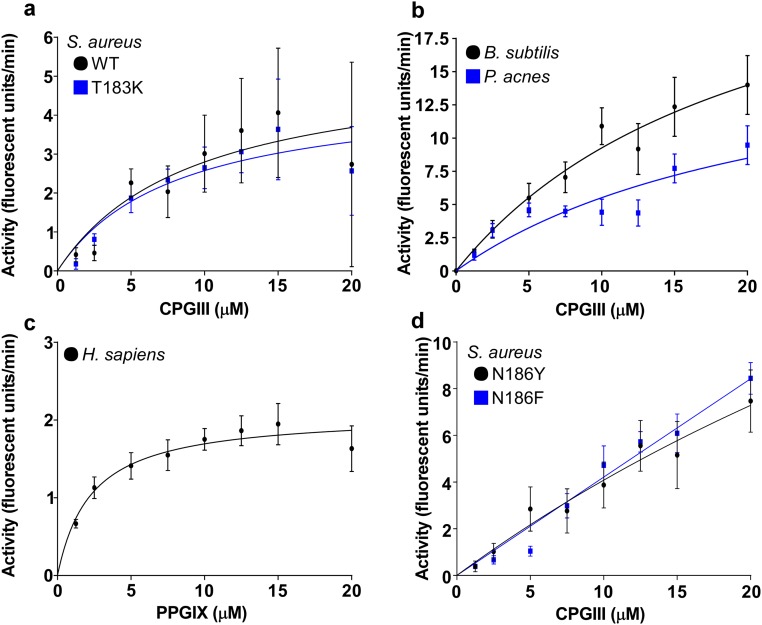

To determine whether ‘882 directly activates S. aureus CgoX, recombinant S. aureus WT CgoX and CgoX T183K were purified. Importantly, these two enzymes display similar Km and Vmax values, demonstrating the T183K mutation does not affect baseline CgoX activity (Fig. 2G and Fig. S4A). Upon treatment with ‘882, WT CgoX displayed 205% activity with an AC150 of 92 nM, whereas the T183K mutant did not respond to ‘882 at concentrations up to 10 μM (Fig. 3 A and G). These data establish ‘882 as a small-molecule activator of CgoX.

Fig. 2.

‘882 activates CgoX from Gram-positive bacteria and identification of a region important for regulation of CgoX. (A, B, and F) CgoX activity was assayed with increasing ‘882 concentrations and 5 μM CPGIII. (C) HemY activity was assayed with increasing ‘882 concentrations and 5 μM PPGIX. (D) The residue of B. subtilis CgoX homologous to S. aureus T183 (blue) is located in a region distinct from the active site (Y366, yellow) (19, 51). B. subtilis CgoX shares 46% identity with S. aureus CgoX. A residue homologous to S. aureus N186 (red) faces a cleft leading into the active site. (E) Magnified view of residues homologous to S. aureus T183 and N186 residues (carbon in light blue, nitrogen in dark blue, and oxygen in red). (G) Km, Vmax, AC150, and activation (in percentage) for each enzyme were determined.

Fig. S4.

Characterization of CgoX activity from Gram-positive bacteria and HemY from H. sapiens. (A–D) Activities of recombinant CgoX from S. aureus (WT, T183K, N186Y, N186F), B. subtilis, P. acnes, and H. sapiens HemY with varying concentrations of coproporphyrinogen III (CPGIII) for Gram-positive CgoX and protoporphyrinogen IX (PPGIX) for H. sapiens HemY to determine Km and Vmax.

Fig. 3.

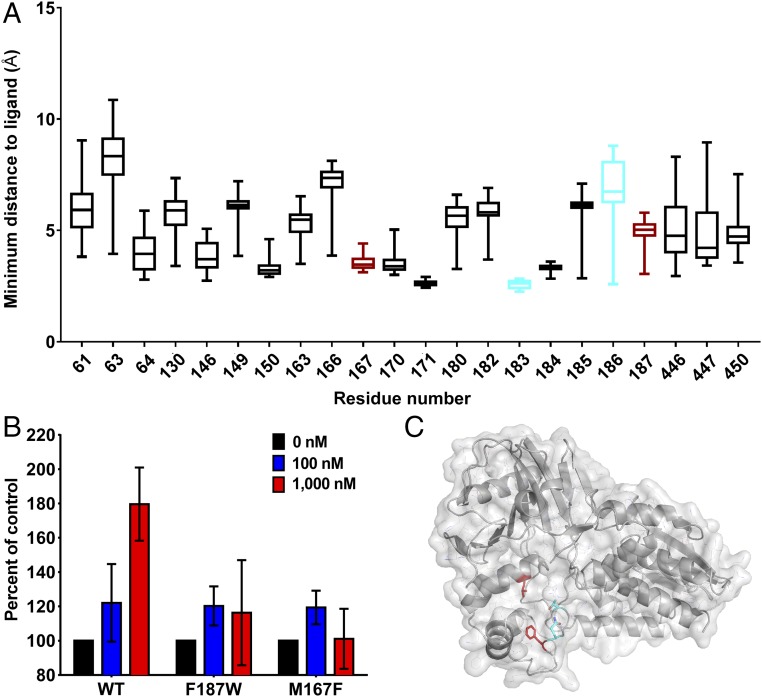

Identification of additional mutations that affect ‘882 activity. (A) Distribution of ligand–residue distances for the subset of protein residue positions for which at least one of the top 100 ligand conformations was within 4 Å, shown as boxplots (box represents 25th and 75th percentile, and the horizontal line inside the box represents the median; vertical bars span between the min and max values). The two residues used to guide the docking are shown in cyan, whereas the two additional residues that were identified by the modeling approach and confirmed to have the desired disruption of ‘882 activity are shown in red. Structural analysis was performed on the B. subtilis crystal structure; homologous residue numbers to the S. aureus sequence are displayed (19). (B) CgoX activity was assayed with ‘882 and 5 μM CPGIII. (C) Structural model highlighting the same four residues as in the boxplot in the B. subtilis structure (19).

To determine whether ‘882 retains activity against CgoX from other Gram-positive organisms, recombinant Bacillus subtilis and P. acnes CgoX were purified (7). Km and Vmax values were determined to characterize baseline activity of the enzymes, and each was tested for ‘882-induced activation (Fig. 2 B and G and Fig. S4B). ‘882 activates CgoX from B. subtilis and P. acnes with AC150 values of 42 and 16 nM, respectively (Fig. 2 B and G). Importantly, human HemY, a protoporphyrinogen oxidase as opposed to a coproporphyrinogen oxidase, did not respond to ‘882 treatment (Fig. 2C and Fig. S4C). These results establish ‘882 as a small-molecule activator of CgoX from Gram-positive bacteria.

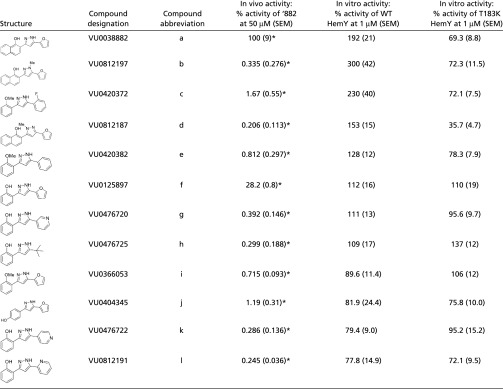

Structure–Activity Relationship Studies of ‘882.

Recently, a series of structural analogs of ‘882 were prepared and screened in a phenotypic HssRS activation assay using a XylE reporter gene to monitor transcription of hrtAB as a response to heme accumulation (15) (Table 1). These analogs were assayed in the CgoX activation assay using WT and T183K mutant enzymes (Table 1). Three analogs, b, d, and l, proved superior or comparable to ‘882 as CgoX activators in vitro. Notably, none of these more potent activators exhibit increased ability to trigger hrtAB expression in S. aureus over that of ‘882, suggesting that these compounds do not have improved bioavailability over ‘882 in staphylococcal cells. In addition, these ‘882 derivatives are also inactive against the T183K mutant, suggesting all four diarylpyrazoles share a common binding site. The remaining eight diarylpryazoles were equally inactive when assayed against CgoX or the T183K mutant. Collectively, these structure–activity relationship studies support activation of CgoX by a common allosteric binding site.

Table 1.

Structural analogs of ‘882 activate HemY

|

Previously published data (15).

Structural Analysis of the ‘882–CgoX Interaction.

To gain insight into the potential binding site of ‘882 within CgoX, the previously solved crystal structure of B. subtilis CgoX was interrogated (19) (Fig. 2D). Based on the location of S. aureus T183 within CgoX, a nearby amino acid, N186, was implicated as potentially important due to its proximity on a short helix facing a cleft leading into the active site (Fig. 2 D and E). The N186 residue was mutated to tyrosine, phenylalanine, or alanine and the activity of the mutant enzyme was examined in the presence or absence of ‘882 (Fig. 2 F and G and Fig. S4D). CgoX N186Y and CgoX N186F exhibit increased baseline activity relative to WT CgoX, suggesting this region is important for positive enzyme regulation (Fig. 2G and Fig. S4D). Consistent with this, all three mutations abolish the ability of CgoX to respond to ‘882 treatment (Fig. 2 F and G). Importantly, the helix containing these residues is in a distinct region from the active site of the molecule (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data support a model whereby ‘882 binds to the region of CgoX containing residues 183–186 and acts as an allosteric modulator of enzyme activity. Mutations in this portion of the enzyme may mimic ‘882-induced changes in tertiary structure leading to enzyme activation.

In Silico Docking Identifies a Functional Domain Important for ‘882 Activation.

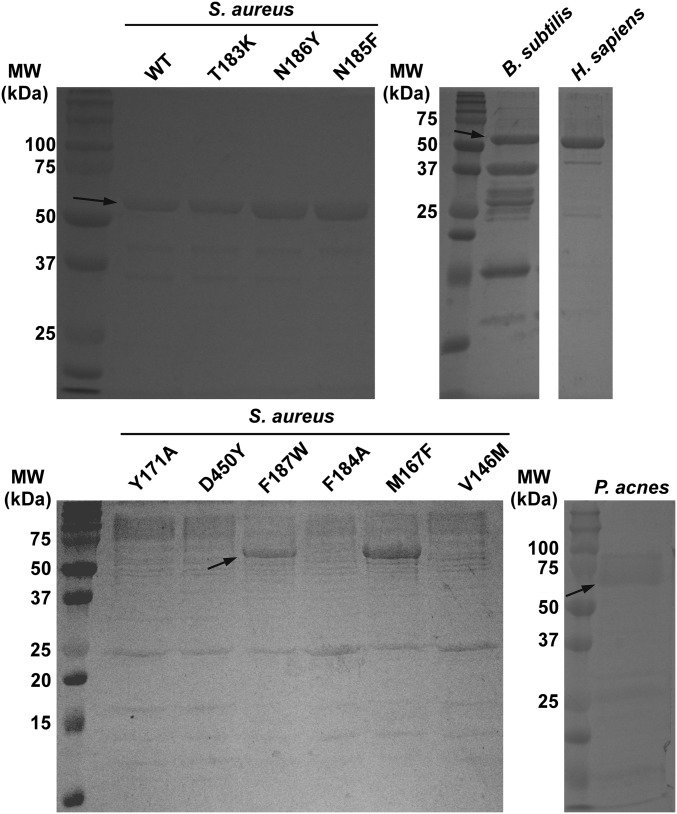

Despite significant efforts, we were unsuccessful in our attempts to solve the complete crystal structure of ‘882 in complex with CgoX from various Gram-positive organisms. A flexible loop encompasses residues 183–186 that were identified in our initial mutational analysis. Importantly, previously published structures of CgoX are also incomplete in this region (19, 20). Therefore, to further our understanding of the functional domain required for ‘882 activity in the absence of a crystal structure, the ‘882–CgoX interaction was modeled by in silico docking to identify additional residues that may be required for ‘882-induced activity of CgoX. Based upon this analysis, six more residues within CgoX were selected for mutational analysis to interrogate their importance for ‘882-dependent activation (Fig. 3A). Mutations were made in S. aureus CgoX, creating the enzyme variants V146M, M167F, Y171A, F184A, F187W, and D450Y. Upon induction, V146M, Y171A, F184A, and D450Y led to unstable enzymes that could not be purified (Fig. S5). CgoX M167F and F187W expressed equivalently to WT (Fig. S5), were purified, and interrogated for ‘882-induced activation. Both mutations inhibited the activation of CgoX by ‘882 (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these data begin to define a pocket within CgoX that appears to be required for ‘882-dependent activation of the enzyme (Fig. 3C).

Fig. S5.

Purity of CgoX or HemY used in biochemical assays. After purification, each protein was analyzed by SDS/PAGE to verify purity.

CgoX Activation Induces Photosensitization of Gram-Positive Bacteria.

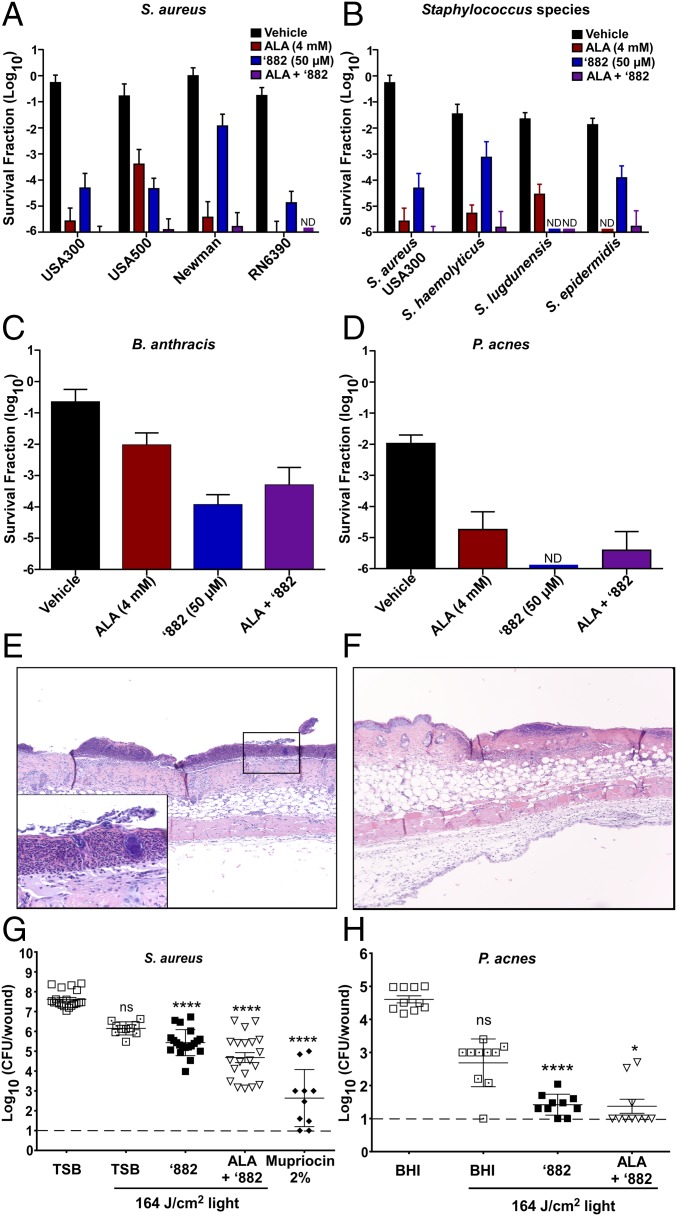

PDT is frequently used to treat bacterial skin infections and involves the use of a photosensitizer and a light source to destroy cells through the production of reactive oxygen species (6). Porphyrin intermediates of the heme biosynthesis pathway are the most common photosensitizers used in clinics. The production of porphyrin intermediates is often up-regulated through the addition of ALA, the first committed precursor in the heme biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1A). A major limitation of ALA-PDT for the treatment of infectious diseases is the lack of specificity of this therapy, which induces photosensitivity in both bacterial and human cells. Due to the specificity of ‘882 for CgoX from Gram-positive bacteria, this molecule should selectively sensitize bacteria to light while avoiding host toxicity. To test this hypothesis, various strains of S. aureus were grown in the presence of ALA, ‘882, or both and exposed to 395-nm light, the absorbance maximum for CPIII as determined experimentally (data not shown). Both ALA and ‘882 treatment led to significant growth inhibition of S. aureus following exposure to 68 J/cm2 light (Fig. 4A). An additive effect was seen when ‘882 and ALA were in combination, likely due to ALA increasing precursor availability for CgoX. Notably, ALA and ‘882 combined decreased S. aureus viability by six logs compared with untreated cells (Fig. 4A). The toxicity of ‘882-PDT is conserved across some of the most important causes of human skin infections, including S. epidermidis, Staphylococcus haemolyticus, Staphylococcus lugdunensis, B. anthracis, and P. acnes (Fig. 4 B–D). These results establish the utility of ‘882-PDT as a potential therapeutic for the treatment of skin infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria.

Fig. 4.

‘882 induces photosensitivity in Gram-positive pathogens. (A–H) S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. haemolyticus, S. lugdunensis, B. anthracis, and P. acnes were exposed to ALA, ‘882, or ALA plus ‘882 in the absence or presence of 68 J/cm2 light dose (395 nm). The survival fraction ± SD (A–D) was calculated by taking the number of surviving CFU of the light-exposed bacteria divided by the CFU of untreated bacteria (n = 9). (E–G) Mice infected with S. aureus USA300 LAC were treated with ‘882 (n = 20), ALA plus ‘882 (n = 20), 2% mupirocin ointment (n = 10), or left untreated in the absence (n = 20) or presence (n = 10) of a total dose of 164 J/cm2. (G) Total log10 bacterial burden per wound ± SEM was quantified 16 h postinfection. (E) Section (10×; TSB 0 J/cm2) shows a severe, neutrophilic epidermitis with a thick serocellular crust including coccal bacterial colonies [see Inset (40×)]. Inflammatory cells are primarily neutrophils and to a lesser extent mononuclear leukocytes and extend into the dermis and dermal adipose. (F) This section (10×; ALA plus ‘882 plus 164 J/cm2) shows a margin of wounded epithelium and the adjacent nontreated epithelium. The treated portion has a layer of neutrophils just below the epidermis. Neutrophils and mononuclear leukocytes are present within the underlying dermal fibrous connective tissue, adipose tissue, and extending into the loose connective tissue below the muscle. (H) Mice infected with P. acnes were treated with either ‘882 or a combination of ALA and ‘882 in the absence or presence of a total dose of 164 J/cm2 (each group = 10). Total log10 bacterial burden per wound ± SEM was enumerated 16 h postinfection. (G and H) Dashed lines indicate the limit of the detection for bacterial burden.

‘882-PDT Decreases Bacterial Burdens in Vivo.

To determine the in vivo efficacy of ‘882-PDT, a murine model of superficial S. aureus skin infection was used, which leads to considerable skin ulceration (21). Mice infected with S. aureus USA300 LAC and treated with ‘882-PDT or ‘882/ALA-PDT exhibited significantly lower bacterial burden per wound following infection compared with untreated animals (Fig. 4G). Histologically, all groups showed varying degrees of inflammation, with neutrophils being the most abundant cells present; however, bacterial burden was noticeably reduced in ‘882-PDT- and ‘882/ALA-PDT-treated samples (Fig. 4 E and F). Topical administration of 2% mupirocin ointment, as a positive control antibiotic, also significantly reduced bacterial burden compared with untreated mice. (Fig. 4G).

To evaluate the broad utility of ‘882-PDT as a therapy for common skin infections, the efficacy of ‘882-PDT in a murine model of P. acnes infection was determined. Both ‘882-PDT and ‘882/ALA-PDT led to a significant decrease in bacterial burden compared with untreated mice, highlighting the utility of ‘882 as a possible compound for the treatment of acne (Fig. 4H). Taken together, these findings establish PDT coupled with small-molecule activation of CgoX as an effective therapeutic strategy to specifically target Gram-positive pathogens.

Discussion

These results define the small-molecule ‘882 as an activator of Gram-positive CgoX. Treatment with ‘882 leads to massive heme accumulation resulting in HssRS activation in S. aureus. Residues required for ‘882-induced CgoX activation have been identified, thereby revealing a functional domain involved in the activation of CgoX. In addition, treatment with ‘882 leads to photosensitization of Gram-positive bacteria, reducing bacterial burdens in vivo. Taken together, these results establish ‘882 as an activator of Gram-positive CgoX and provide proof-of-principle for small-molecule activation of CgoX as a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of bacterial infections.

Synthetic small-molecule activators are rare, with only a handful identified to date (22). Identifying the targets of small molecules is a major obstacle in biomedical research (23–25). Phenotypic high-throughput screens using small-molecule libraries often result in the identification of numerous molecules with unknown targets. Several approaches have been successful in identifying intracellular targets of small molecules (26–32). Here, we report a genetic selection strategy based on the creation of a suicide strain that enables the identification of spontaneous resistant mutants to an activating compound that is typically nontoxic. This strategy can be adapted to a variety of systems where a small molecule activates a specific gene expression program, and may enable the identification of targets for numerous small-molecule activators.

The mechanisms by which heme biosynthesis is regulated in Gram-positive bacteria are largely unknown (9). The identification of ‘882 as an activator of CgoX establishes this molecule as a valuable tool for interrogating the heme biosynthetic pathway in Gram-positive bacteria to further understand the synthesis of this essential cofactor. Interestingly, it has previously been demonstrated that CgoX activity is modulated in vitro to a similar extent by addition of ChdC (previously known as HemQ), the terminal enzyme in the Gram-positive heme biosynthesis pathway (33). This suggests that the interaction of CgoX with ‘882 may not be a random occurrence but may represent an inappropriate hijacking of a normal in vivo regulatory mechanism. The ‘882-dependent activation of heme biosynthesis represents a valuable tool for studying the regulation of heme biosynthesis in Gram-positive bacteria.

Notably, enzyme activators have numerous properties that make them ideal therapeutics (22). Whereas inhibitors often require the ability to inhibit the enzyme by 90%, activators can induce phenotypes with small increases in enzyme activity, indicating that derivatives of ‘882 with slight increases in activity could lead to dramatic increases in CPIII accumulation and therefore antibacterial properties (22). Specifically, this has been seen with small-molecule activators of glucokinase, where a 1.5-fold increase in enzymatic activity has shown significant effects in vivo. These molecules are now used as therapeutics for diabetes (22, 34–36).

In addition, inhibitors often bind active sites of enzymes, which are typically well conserved across homologous enzymes. In contrast, activators often bind allosteric sites, which are less well conserved across enzymes, thus increasing specificity and limiting off-target effects (22, 34, 37). Structural analysis of the ‘882–CgoX interaction has identified a functional domain of CgoX that suggests an allosteric mechanism of action for ‘882-induced activation (Figs. 2 and 3). In addition, we have identified specific residues that when mutated increase activity, further supporting that this portion of the enzyme is important in positive regulation (Fig. 2). Therefore, ‘882 and its derivatives have value as both probes of heme biosynthesis as well as small-molecule photosensitizers for the treatment of bacterial infections.

The use of PDT has begun to expand beyond SSTIs. Gastrointestinal endoscopes have been developed that emit wavelengths that activate porphyrins in patients to detect cancer, and similar strategies have been interrogated for their ability to treat gastrointestinal infections (38, 39). Osteomyelitis and contamination of orthopedic devices are some of the most common invasive bacterial infections, and PDT strategies to combat these infections are being developed (40–46). Finally, PDT-based strategies are in development for a variety of other diseases, including parasitic, dental, and sinus infections (47, 48). One of the key limitations for PDT approaches involving photosensitizers that need to be activated with light at shorter wavelengths (below 500 nm) is the lack of deep-tissue penetration of light at those wavelengths. Therefore, the development of strategies to increase the penetration of light may considerably improve the therapeutic potential of porphyrin-based PDT. As the utility of PDT-based therapies expands, so too will the potential clinical utility of small-molecule activators of CgoX.

The ability of ‘882 to specifically photosensitize Gram-positive bacteria circumvents the nonspecific nature of ALA-PDT, which has limited the value of ALA-PDT for the treatment of infectious diseases (6, 49, 50). Furthermore, this provides proof-of-concept that activation of bacterial porphyrin production through specific activation of CgoX is a viable therapeutic strategy that could be adapted to Gram-negative bacteria and other infectious diseases (6, 16, 47). Therefore, the development of ‘882-PDT has the potential to significantly expand the value of light-based therapies for the treatment of the most common causes of skin infections.

Materials and Methods

Descriptions of growth conditions, strain construction, suicide strain selection experiments, genomic analysis, heme precursor quantification, promoter activity assays, CgoX activity assays, in silico docking studies, photosensitivity assays, superficial skin infection studies, and chemical synthesis can be found in SI Materials and Methods. Bacterial strains, expression constructs, plasmids, and primers used in this study can be found in Tables S1–S4. All research involving animals described in this paper was reviewed and approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Table S1.

Bacterial strains

| Bacterial strain | Description | Source |

| Wild type | S. aureus strain Newman | Ref. 64 |

| Wild type | S. aureus strain USA300 | |

| Wild type | S. aureus strain USA500 | |

| Wild type | S. aureus strain RN6390 | |

| ΔhrtB | In-frame deletion of hrtB in Newman background | Ref. 65 |

| RN4220 | S. aureus cloning intermediate | Ref. 66 |

| hrtAB::relE | S. aureus strain Newman expressing two copies of relE at the hrtAB locus | This study |

| CgoX.T183K | S. aureus strain Newman harboring a T183K mutation in CgoX | This study |

| ΔCgoX | S. aureus strain Newman harboring a transposon interrupting CgoX expression | This study |

| ΔhssRS | In-frame deletion of hssRS in Newman background | Ref. 67 |

| S. epidermidis | Strain NRS6 | BEI |

| S. haemolyticus | HIP05979 (NRS9) | BEI |

| S. lugdunensis | Timothy Foster | |

| B. anthracis | Strain Sterne | Ref. 68 |

| P. acnes | ATCC 6919 | ATCC |

Table S4.

Primers

| Primer name | Sequence |

| SA_cgoX_T183K_T | AGTTTGATGAGTACGTTTCCTAATTTTAAAG |

| SA_cgoX_T183K_B | CTTTAAAATTAGGAAACGTACTCATCAAACT |

| N186Y_T_NWMN1723 | GTTTGATGAGTACGTTTCCTTATTTTAAAGAAAAAGAAGAGGC |

| N186Y_B_NWMN1723 | GCCTCTTCTTTTTCTTTAAAATAAGGAAACGTACTCATCAAAC |

| N186F_T_NWMN1723 | GTTTGATGAGTACGTTTCCTTTTTTTAAAGAAAAAGAAGAGGC |

| N186F_B_NWMN1723 | GCCTCTTCTTTTTCTTTAAAAAAAGGAAACGTACTCATCAAAC |

| SA_Y171A_T | CCTTTAATGGGTGGTATTGCTGGTACCGATATTG |

| SA_Y171A_B | CAATATCGGTACCAGCAATACCACCCATTAAAGG |

| SA_D450Y_T | GCGGTTGGACTACCTTATTGTATTACGCAAGG |

| SA_D450Y_B | CCTTGCGTAATACAATAAGGTAGTCCAACCGC |

| SA_F187W_T | GAGTACGTTTCCTAATTGGAAAGAAAAAGAAGAGGCATTCGG |

| SA_F187W_B | CCGAATGCCTCTTCTTTTTCTTTCCAATTAGGAAACGTACTC |

| SA_F184A_T | GTTTGATGAGTACGGCTCCTAATTTTAAAGAAAAAGAAGAGGC |

| SA_F184A_B | GCCTCTTCTTTTTCTTTAAAATTAGGAGCCGTACTCATCAAAC |

| SA_M167F_T | GAGAATTTAATAGAGCCTTTATTTGGTGGTATTTATGG |

| SA_M167F_B | CCATAAATACCACCAAATAAAGGCTCTATTAAATTCTC |

| SA_V146M_T | GGATGGTGACATTTCTATGGGTGCATTTTTCAGAGC |

| SA_V146M_B | GCTCTGAAAAATGCACCCATAGAAATGTCACCATCC |

| MS001 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGATTTGCTTAGGACGTGCTGC |

| MS001b | GATTTGCTTAGGACGTGCTGC |

| MS019 | GCGTCTTTACAAGCCACATATGGATTCACTTCTCCCTATTTCTTC |

| MS020 | GGGAGAAGTGAATCCATATGTGGCTTGTAAAGACGC |

| MS006 | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGGCCAACTTAAGCCAGG |

| MS006b | GGCCAACTTAAGCCAGG |

| MS023 | GCGGCGCATATGGCGTATTTTCTGGATTTTGACG |

| MS024 | CGCCGCCATATGGCTTTGGTTCAGAGAATGCG |

| pet15_cgoXF1 | GCGGCAGCCATATGGTGACTAAATCAGTGGCTATTATAG |

| pet15_cgoXF2 | GCGGCAGCCATATGCTAGTGACTAAATCAGTGGCTATTATAG |

| pet15_cgoXR | GCTTTGTTAGCAGCCGTTACAACTCTGCGATTACTTC |

| pKOR1_cgoX_FattB | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGTGACTAAATCAGTGGCTATTATAG |

| pKOR1_cgoX_RattB | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTTACAACTCTGCGATTACTTC |

Table S3.

Plasmids

SI Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

Cloning was performed in Escherichia coli DH5α (Invitrogen). Strains, plasmids, and primers used are described in Tables S1–S4. All proteins were expressed using E. coli strain BL21(DE3) pREL (11). All S. aureus and S. epidermidis strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) or agar (TSA), E. coli and B. anthracis were grown in lysogeny broth (LB) or lysogeny broth agar (LBA), and P. acnes in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth or agar, unless otherwise stated.

Strain Construction.

The suicide strain was constructed by allelic replacement as previously described (52). PCR was performed with Phusion Polymerase (Thermo Scientific), unless stated otherwise. The genomic context upstream of hrtAB was amplified using primers MS0001b and MS019, and the downstream fragment was amplified using primers MS020 and MS006b. The fragments were fused by PCR SOEing to create an NdeI site between the upstream and downstream fragments (53). The 3′-adenosine overhangs were added by incubation with ExTaq (TaKaRa) for 20 min at 72 °C. The resulting product was ligated into PCR2.1 according to manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies). relE was amplified from E. coli DH5α using primers MS023 and MS024. The plasmid and PCR products were digested with NdeI (New England Biolabs) and ligated with T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs) to insert the toxin gene between upstream and downstream fragments. The plasmid DNA was isolated from transformants, and a strain harboring two copies of relE in the correct orientation was selected for downstream applications. Using this plasmid as a template, primers MS001 and MS006 were used to amplify the suicide construct. This was inserted into pKORI, and allelic exchange was performed as previously described (52).

S. aureus strain CgoX::ermC was described previously and the CgoX::ermC allele was transduced into strain Newman using the Φ-85 bacteriophage (54, 55). To create an S. aureus strain harboring the T183K mutation in CgoX, cgoX was amplified from the point mutant isolated in the suicide selection using primers pKORI_CgoX_FattB and pKORI_CgoX_RattB. This construct was moved into pKORI and allelic replacement was used as previously described (52).

Suicide Strain Selection.

Overnight bacterial cultures of suicide strain or ΔhrtB were subcultured 1:100 into 5 mL of TSB and grown for 8 h. One hundred microliters of a 1:40,000 dilution were plated on media containing ‘882 (5–15 μM). The resistant colonies were passaged twice on TSA to ensure resistance was genetically stable, and rechallenged by plating on heme or ‘882. The colonies that retained resistance to ‘882 but were sensitive to heme were used for downstream analysis.

Genome Sequencing and Analysis.

Genomic DNA was isolated from mutant strains using the Wizard Genomic Kit (Promega) and sequenced to identify mutations in hssRS/Phrt/relErelE. Strains containing mutations in this locus were eliminated from subsequent analyses. The genomes from strains lacking mutation in this locus were sequenced by Perkin-Elmer on the MiSeq Platform.

Whole-genome sequencing analysis was automated with a tool written in the Python programming language. The input files were the Newman genome (.fas) and the mutations file (.csv). The program iterates through each mutation determining the mutation type and resultant amino acid change, if applicable. The input .csv is preprocessed to combine proximal mutations in the same strain as both must be considered due to their combined codon effect. The script also includes options to specify the organism ID, the base pair radius around the mutation to use for genome matching, an e-value threshold for allowable search results, and a customizable delimiter character for visualization. The program takes into account both strand directions when searching to ensure complete coverage as well as potential missed search matches at the edges of the genome. All mutations are classified based on their effect—silent, substitution, frameshift, truncation, or deletion.

The Bacterial, Archaeal, and Plant Plastid Code (transl_table = 11) was used as our translation table; more information can be found at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Utils/wprintgc.cgi.

Mutations in noncoding regions or that produced silent mutations in the amino acid sequence were removed. Mutations were compared with a control suicide strain not subjected to selection to eliminate mutations present in the parent strain. The genes identified in this analysis were resequenced in the relevant strain to confirm the presence of the mutation.

Heme Precursor Quantification.

Cells were grown in TSB overnight in the presence or absence of 40 μM ‘882. The cells were pelleted and lysed as previously described (11). PBG was quantified from lysate as previously described (56). Briefly, modified Erlich’s reagent was prepared by dissolving 1 g of p-dimethylaminobenzaldehyde (Sigma) in 16 mL of 70% perchloric acid and bringing final the volume to 50 mL with glacial acetic acid. The lysate was mixed with fresh Erlich’s reagent and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. The absorbance at 555 nm was determined and compared with a standard curve using fresh PBG (Frontier Biosciences) to determine the concentration. For HPLC analysis, protoplast lysates were incubated with Dianon HP20 beads for 1 h at 4 °C. Hydrophobic molecules were eluted from the beads with 3 mL of acetone. The samples were protected from light. The hydrophobic molecules were concentrated in vacuo for 24 h at room temperature. The samples were resuspended in 200 μL of 1:1 water/acetonitrile with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. HPLC was performed as previously described (57). Absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 400 nm to identify heme precursor molecule peaks. The fractions corresponding to the retention time of CPIII and heme standards were collected and lyophilized. The lyophilized fractions were resuspended in 100 μL of 1:1 water/acetonitrile and analyzed by LC-MS/MS as previously described (56).

Promoter Activity Assay.

Promoter activity assay was performed as previously described (13). Briefly, phrtAB.XylE was electorporated into the strain CgoX.T183K. The other strains used have been previously described (11). Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 into TSB supplemented with 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol under the following conditions: vehicle (DMSO), 1 μM heme, or 10 μM ‘882. Cells were grown for 6 h and assayed as previously described (12). The experiment was performed in triplicate on three separate days (n = 9). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Student’s t test was performed to determine significance.

S. aureus CgoX Expression Construct.

S. aureus CgoX was amplified from either Newman or the suicide strain resistant to ‘882 containing the T183K mutation using primers pET15_CgoXF1 and pET15_CgoXR and inserted into pET15b using the Gibson Assembly Cloning Kit (New England Biolabs). The point mutations in CgoX were created using Pfu mutagenesis with primers described in Table S4 (58).

Enzyme Expression and Purification.

The plasmids described in Table S2 were transformed into BL21(DE3) pREL. An overnight of a strain harboring each CgoX expression construct was diluted 1:100 into Terrific Broth (Fisher Scientific) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics and 10 μg/mL riboflavin. Cells containing Homo sapiens HemY were grown at 37 °C overnight. The cells containing S. aureus and P. acnes CgoX were grown at 37 °C until they reached an OD600 of 0.7, induced with 0.1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and grown at 30 °C overnight. The cells containing B. subtilis CgoX were grown at 37 °C until they reached an OD600 of 0.7, induced with 0.1 mM IPTG, and grown for 5 h 37 °C. The cells were washed with PBS and stored at −80 °C until protein was harvested. The cells were resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-Mops, pH 8.0, 0.1 M potassium chloride, and 1% sodium cholate hydrate supplemented with 1 mg/mL lysozyme and one Pierce Protease Inhibitor Tablet (Thermo Scientific)], homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer, and passed through an EmulsiFlex (Avestin) four times. Lysate was centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 1 h and filtered with a 0.22-μM filter.

Table S2.

Expression constructs

| Protein | Expression vector | Source |

| Wild-type S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| T183K S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| N186F S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| N186Y S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| Y171A S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| D450Y S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| F187W S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| F184A S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| M167F S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| V146M S. aureus CgoX | pET15b | This study |

| B. subtilis CgoX | pTrcHisA | Ref. 33 |

| H. sapiens HemY | pTrcHisB | Ref. 2 |

| P. acnes CgoX | pTrcHisA | Ref. 69 |

S. aureus and P. acnes CgoX and H. sapiens HemY were purified using HisPur Cobalt Superflow Agarose (Thermo Scientific). The lysate was mixed with agarose and incubated at 4 °C with rotating for 30 min. The lysate and beads were poured into a gravity column followed by washing with 10 column volumes of 5 mM imidazole in the lysis buffer. Proteins were eluted with 250 mM imidazole in lysis buffer in 5 column volumes. B. subtilis protein was purified on an AKTA FPLC (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) with a linear gradient from 0 to 500 mM imidazole in lysis buffer. Glycerol was added to 10% total volume, and protein was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. A fresh aliquot was used each day for assays.

All purified enzymes were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and tested for activity to verify purity (Fig. S5).

CgoX Activity Assay.

Purified CgoX was assayed as previously described (59). The reactions were performed in 300-μL volume and incubated at room temperature for 10 min before initiating the reaction. Reactions were monitored using a Cytation 5 (BioTek), and performed at least twice in triplicate. Km and Vmax values were determined by fitting data using the Michaelis–Menten equation in Prism (GraphPad) using 10.8 μg of protein in each reaction. AC150 and activation (in percentage) values were determined using Response vs. Log (substrate) in Prism (GraphPad). For S. aureus and H. sapiens, 10.8 μg of protein was used to determine the AC150. For B. anthracis and P. acnes, 5.4 μg of protein was used to determine the AC150 to keep reactions in the linear range of the instrument. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Identification of Additional Mutations That Affect ‘882 Activity.

Protoporphyrinogen oxidase structure (PDB ID code 3I6D, chain A) from Bacillus subtilis was used for the structural analysis. Molecular docking simulations with ligand ‘882 were performed using the AutoDock 4.2 and AutoDock tools (60). The protein was prepared for docking by assigning polar hydrogens, solvation parameters, and Kollman united atom charges, whereas Gasteiger charges were assigned to the ligand. Water molecules were removed from the input structure. The ligand was modeled as flexible around rotatable bonds. The grid box was centered around residues T189 and Q192 (S. aureus T183 and N186). Flexible docking was performed by modeling as flexible these two residues, as well as the nearby Y177, F190, and F193. The default grid box size was adjusted to allow a free rotation of the ligand, and set at 70 × 70 × 70, with a grid spacing of 0.375 Å. Grid maps were generated using the AutoGrid program. The Lamarckian genetic algorithm (LGA) was used for the conformer search, with default parameters, including selection window (10 generations), population size (150), and maximum number of energy evaluations (2,500,000) (61). A total of 8,000 docked conformations was generated, and the 100 lowest-energy models were selected for further analysis. Potential mutations at residues, for which at least one ligand conformation (from the top 100) was within 4 Å, were modeled structurally, for selection of mutations to destabilize the interactions between the protein and the ‘882 ligand. Structural models were visualized using the PyMOL software. Two types of mutations were selected for experimental validation: (i) larger amino acid side chains that could sterically hinder ligand binding but that could be accommodated within the protein binding pocket, or (ii) Ala mutations at residues that were found to have substantial ligand interactions in the docking models.

Light Source and Photosensitivity Assays.

A 395-nm wavelength LED (M395L4; Thorlabs) was mounted 4.5 cm above the sample and collimated using a collimation lens (ACP2520-A; Thorlabs). The diode was powered by a T-cube LED driver (LEDD1B M00325270; Thorlabs) producing 179 mW at the sample with a circular spot size 1 cm in diameter covering an area of 0.785 cm2 with an irradiance of 227.9 mW/cm2 with an exposure time of 5–6 min. All light-killing experiments were performed on 3 separate days and averaged.

Overnight cultures of S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. lugdunensis, or B. anthracis were subcultured 1:50 into TSB and either 50 μM ‘882, 4 mM δ-aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride (ALA) (Frontier Biosciences), or a combination of the two. Cultures were grown for 3 h to reach exponential phase of growth. Cell pellets were washed once with ice-cold PBS at two times the original culture volume, centrifuged, and resuspended in the original culture volume with ice-cold PBS. Cells were diluted 1:10 into ice-cold PBS. Twenty-five microliters were transferred into a black 96-well plate with flat, clear bottom and exposed to light to 0 or 68 J/cm2. The bacteria were serially diluted, plated, and CFUs were counted after 20 h of growth on LB agar.

A 5-d anaerobic culture of P. acnes in BHI was removed from the anaerobic chamber (Coy) and subcultured 1:100 into BHI with either 50 μM ‘882, 4 mM δ-aminolevulinic acid hydrochloride (Frontier Biosciences), or a combination of the two. The culture was grown for 24 h under anaerobic conditions. The culture was then removed from the anaerobic chamber, washed once with ice-cold PBS, and diluted 1:10 into PBS. Twenty-five microliters were transferred into a flat-bottom 96-well plate and exposed to light to 0 or 68 J/cm2. The bacteria were serially diluted and plated, and CFUs were counted after 5 d of growth on BHI agar. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Superficial Skin Infection.

All mice were maintained in compliance with Vanderbilt’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee regulations. Animals were infected as previously described using a tape-stripping model of infection (21). Six- to 8-wk-old female BALB/cJ mice were used for both S. aureus and P. acnes infections. Briefly, cultures of S. aureus USA300 LAC and P. acnes were grown overnight and subcultured as described for the in vitro photosensitivity assays including pretreatment with ‘882 and ALA. Approximately 1 × 107 log-phase CFUs were inoculated in 5 μL of PBS directly onto the surface of the fresh wound. Following infection, the mouse was transferred to a nose cone under continuous isoflurane anesthesia and the wound was exposed to the 395-nm LED for 6 min delivering a total energy dose of ∼82 J/cm2. Control mice were either left untreated or were administered a dose of mupirocin ointment 2% (TARO Pharmaceuticals) with a sterile-cotton tipped applicator. Eight hours postinfection, groups of mice were treated with 20 μL of 1 mM ‘882 in 2% Tween 80 in PBS, 20% ALA and 1 mM ‘882 in 2% Tween 80 PBS, 2% Tween 80 PBS vehicle alone, or a second dose of mupirocin ointment. Two to 3 h after application of compounds, groups of mice were challenged with a second dose of light or left untreated for a total dose of 164 J/cm2. Upon completion of the second dose of light treatment, skin samples containing the wound were homogenized using a Bullet Blender (Next Advanced) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The homogenate was serially diluted and plated. Data are represented as mean ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s multiple-comparisons test was performed to determine significance (GraphPad).

Histological Examinations.

Sections of skin were excised after the mice were killed, and then placed in 10% Neutral Buffered Formalin. Fixed tissues were then processed routinely by dehydration and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer sections were trimmed and placed on charged slides for staining with H&E. Skin sections were evaluated for inflammation, presence of neutrophils, mononuclear leukocytes, and bacteria using a previously described semiquantitative scoring system (21).

SI Chemical Synthesis

General Procedures.

All nonaqueous reactions were performed in flame-dried flasks under an atmosphere of argon. Stainless-steel syringes were used to transfer air- and moisture-sensitive liquids. Reaction temperatures were controlled using a thermocouple thermometer and analog hotplate stirrer. Reactions were conducted at room temperature (∼23 °C), unless otherwise noted. Flash column chromatography was conducted using silica gel 230–400 mesh. Analytical TLC was performed on E. Merck silica gel 60 F254 plates and visualized using UV and iodine stain.

Materials.

All solvents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted. Dichloromethane (DCM) and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were used as received in a bottle with a SureSeal. Triethylamine was distilled from calcium hydride and stored over KOH. Deuterated solvents were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Trimethylsilylacetylene was purchased from Oakwood Chemicals. S1 and S3 were prepared using previously described procedures (62, 63). Biotin azide (PEG4 carboxamide-6-azidohexanyl biotin) was prepared by the Vanderbilt Institute of Chemical Biology chemical synthesis core. The preparation and characterization of ‘882 derivatives presented in Table 1 have been previously described (15).

Instrumentation.

1H NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker 400- or 600-MHz spectrometers and are reported relative to deuterated solvent signals. Data for 1H NMR spectra are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ ppm), multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, p = pentet, m = multiplet, br = broad, app = apparent), coupling constants (in hertz), and integration. 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker 100- or 150-MHz spectrometers and are reported relative to deuterated solvent signals. 19F NMR were recorded on a Bruker 376-MHz spectrometer. Low-resolution mass spectrometry (LRMS) was conducted and recorded on an Agilent Technologies 6130 Quadrupole instrument.

SI Experimental Procedures

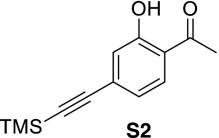

1-(2-Hydroxy-4-((trimethylsilyl)ethynyl)phenyl)ethanone (S2).

1-(2-Hydroxy-4-((trimethylsilyl)ethynyl)phenyl)ethanone (S2).

To a stirred solution of 4-bromo-2-hydroxyacetophenone (S1) (220 mg, 1.02 mmol) in tetrahydrofuran (4 mL) was added triethylamine (284 µL, 2.04 mmol), bis(triphenylphosphine)palladium dichloride (36.0 mg, 0.051 mmol), copper(I) iodide (9.7 mg, 0.051 mmol), and trimethylsilylacetylene (216 µL, 1.53 mmol). The mixture was stirred overnight at room temperature under an atmosphere of argon until judged complete by TLC. The reaction was filtered through Celite, concentrated, and purified by flash chromatography to provide 208 mg (88%) of S2 as white crystals. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.64 (d, J = 8.24 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (d, J = 1.40 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (dd, J = 8.24 Hz, J = 1.52 Hz, 1H), 2.61 (s, 3H), 0.23 (s, 9H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 204.0, 162.1, 131.2, 130.6, 122.5, 121.7, 119.5, 103.7, 98.8, 26.8, −0.1; LRMS calculated for C13H17O2Si+ (M+H)+ m/z: 233.1, measured 233.2.

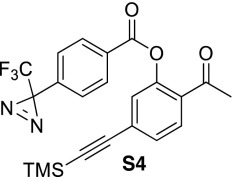

2-Acetyl-5-((trimethylsilyl)ethynyl)phenyl 4-(3-(trifluoromethyl)-3H-diazirin-3-yl)benzoate (S4).

2-Acetyl-5-((trimethylsilyl)ethynyl)phenyl 4-(3-(trifluoromethyl)-3H-diazirin-3-yl)benzoate (S4).

To a stirred solution of phenol S2 (82.0 mg, 0.355 mmol) dissolved in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added triethylamine (54 μL, 0.390 mmol), one crystal of 4-dimethylaminopyridine, and benzoyl chloride S32 (97.0 mg, 0.390 mmol) dissolved in dichloromethane (0.5 mL). The reaction was stirred at room temperature for 1 h until judged complete by TLC analysis. The reaction was diluted with dichloromethane (20 mL), washed with saturated NaHCO3, brine, dried (MgSO4), and concentrated to provide 138 mg (86%) of benzoate S4. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.21 (dt, J = 8.60 Hz, J = 1.80 Hz, 2H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.08 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (dd, J = 8.08 Hz, J = 1.52 Hz, 1H), 7.35–7.31 (m, 3H), 2.51 (s, 3H), 0.25 (s, 9H); 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ -67.9.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the E.P.S. laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript. Core services performed through Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Digestive Disease Research Center were supported by NIH Grant P30DK058404 Core Scholarship. The following reagents were provided by the Network on Antimicrobial Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus for distribution by BEI Resources, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH: Staphylococcus epidermidis strain HIP04645 (NR-45860) and Nebraska Transposon Mutant Library Screening Array (NR-48501). This work was supported by Public Health Service Award T32 GM07347 from the National Institute of General Medical Studies for the Vanderbilt Medical-Scientist Training Program (to M.C.S. and P.L.T.), Grant R01 AI069233 (to M.C.S., L.J.L., and E.P.S.), Grant R01 AI073843 (to M.C.S. and E.P.S.), Grant T32 GM008554-18 (to L.J.L.), Grant T32 GM065086 (to B.F.D.), Grant R01 LM010685 (to P.L.T.), Grant T32 ES007028 (to M.A.), Vanderbilt Vaccine Center startup funds (to R.N. and I.S.G.), Vanderbilt University Medical Center Faculty Research Scholars award (to R.N. and I.S.G.), and Walter Reed Army Institute of Research Grant W81XWH-17-2-0003.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: M.C.S., B.F.D., G.A.S., and E.P.S. have filed a patent for the small-molecule activity reported in this paper.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. F.C.F. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1700469114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tognetti L, et al. Bacterial skin and soft tissue infections: Review of the epidemiology, microbiology, aetiopathogenesis and treatment: A collaboration between dermatologists and infectivologists. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:931–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhate K, Williams HC. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:474–485. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dryden MS. Skin and soft tissue infection: Microbiology and epidemiology. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S2–S7. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(09)70541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Otto M. Community-associated MRSA: What makes them special? Int J Med Microbiol. 2013;303:324–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basra MK, Shahrukh M. Burden of skin diseases. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9:271–283. doi: 10.1586/erp.09.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wan MT, Lin JY. Current evidence and applications of photodynamic therapy in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2014;7:145–163. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S35334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dailey HA, Gerdes S, Dailey TA, Burch JS, Phillips JD. Noncanonical coproporphyrin-dependent bacterial heme biosynthesis pathway that does not use protoporphyrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:2210–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416285112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobo SA, et al. Staphylococcus aureus haem biosynthesis: Characterisation of the enzymes involved in final steps of the pathway. Mol Microbiol. 2015;97:472–487. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choby JE, Skaar EP. Heme synthesis and acquisition in bacterial pathogens. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:3408–3428. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dailey HA, et al. Prokaryotic heme biosynthesis: Multiple pathways to a common essential product. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2017;81:e00048-16. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00048-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mike LA, et al. Activation of heme biosynthesis by a small molecule that is toxic to fermenting Staphylococcus aureus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:8206–8211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303674110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres VJ, et al. A Staphylococcus aureus regulatory system that responds to host heme and modulates virulence. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:109–119. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stauff DL, Torres VJ, Skaar EP. Signaling and DNA-binding activities of the Staphylococcus aureus HssR-HssS two-component system required for heme sensing. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26111–26121. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choby JE, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of iron-sulfur cluster assembly uncovers a link between virulence regulation and metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:1351–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dutter BF, et al. Decoupling activation of heme biosynthesis from anaerobic toxicity in a molecule active in Staphylococcus aureus. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:1354–1361. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maisch T, et al. Photodynamic inactivation of multi-resistant bacteria (PIB)–a new approach to treat superficial infections in the 21st century. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:360–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2010.07577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morimoto K, et al. Photodynamic therapy using systemic administration of 5-aminolevulinic acid and a 410-nm wavelength light-emitting diode for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-infected ulcers in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proctor RA, et al. Small colony variants: A pathogenic form of bacteria that facilitates persistent and recurrent infections. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:295–305. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin X, et al. Structural insight into unique properties of protoporphyrinogen oxidase from Bacillus subtilis. J Struct Biol. 2010;170:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corradi HR, et al. Crystal structure of protoporphyrinogen oxidase from Myxococcus xanthus and its complex with the inhibitor acifluorfen. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38625–38633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606640200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kugelberg E, et al. Establishment of a superficial skin infection model in mice by using Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3435–3441. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3435-3441.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zorn JA, Wells JA. Turning enzymes ON with small molecules. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:179–188. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lomenick B, et al. Target identification using drug affinity responsive target stability (DARTS) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21984–21989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910040106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ziegler S, Pries V, Hedberg C, Waldmann H. Target identification for small bioactive molecules: Finding the needle in the haystack. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:2744–2792. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burdine L, Kodadek T. Target identification in chemical genetics: The (often) missing link. Chem Biol. 2004;11:593–597. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer KL, Daniel A, Hardy C, Silverman J, Gilmore MS. Genetic basis for daptomycin resistance in enterococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:3345–3356. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00207-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaatz GW, Lundstrom TS, Seo SM. Mechanisms of daptomycin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;28:280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peleg AY, et al. Whole genome characterization of the mechanisms of daptomycin resistance in clinical and laboratory derived isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meredith TC, Wang H, Beaulieu P, Gründling A, Roemer T. Harnessing the power of transposon mutagenesis for antibacterial target identification and evaluation. Mob Genet Elements. 2012;2:171–178. doi: 10.4161/mge.21647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H, Claveau D, Vaillancourt JP, Roemer T, Meredith TC. High-frequency transposition for determining antibacterial mode of action. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:720–729. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borden JR, Papoutsakis ET. Dynamics of genomic-library enrichment and identification of solvent tolerance genes for Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:3061–3068. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02296-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luesch H, et al. A genome-wide overexpression screen in yeast for small-molecule target identification. Chem Biol. 2005;12:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dailey TA, et al. Discovery and characterization of HemQ: An essential heme biosynthetic pathway component. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:25978–25986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.142604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimsby J, et al. Allosteric activators of glucokinase: Potential role in diabetes therapy. Science. 2003;301:370–373. doi: 10.1126/science.1084073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonadonna RC, et al. Piragliatin (RO4389620), a novel glucokinase activator, lowers plasma glucose both in the postabsorptive state and after a glucose challenge in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A mechanistic study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5028–5036. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bishop AC, Chen VL. Brought to life: Targeted activation of enzyme function with small molecules. J Chem Biol. 2009;2:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s12154-008-0012-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howitz KT, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi S, Lee H, Chae H. Comparison of in vitro photodynamic antimicrobial activity of protoporphyrin IX between endoscopic white light and newly developed narrowband endoscopic light against Helicobacter pylori 26695. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2012;117:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatogai K, et al. Salvage photodynamic therapy for local failure after chemoradiotherapy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:1130–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cassat JE, Skaar EP. Recent advances in experimental models of osteomyelitis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013;11:1263–1265. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2013.858600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gerber JS, Coffin SE, Smathers SA, Zaoutis TE. Trends in the incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in children’s hospitals in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:65–71. doi: 10.1086/599348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Campoccia D, Montanaro L, Arciola CR. The significance of infection related to orthopedic devices and issues of antibiotic resistance. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2331–2339. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bisland SK, Burch S. Photodynamic therapy of diseased bone. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2006;3:147–155. doi: 10.1016/S1572-1000(06)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bisland SK, Chien C, Wilson BC, Burch S. Pre-clinical in vitro and in vivo studies to examine the potential use of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of osteomyelitis. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2006;5:31–38. doi: 10.1039/b507082a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goto B, et al. Therapeutic effect of photodynamic therapy using Na-pheophorbide a on osteomyelitis models in rats. Photomed Laser Surg. 2011;29:183–189. doi: 10.1089/pho.2010.2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li X, et al. Effects of 5-aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy on antibiotic-resistant staphylococcal biofilm: An in vitro study. J Surg Res. 2013;184:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dai T, Huang YY, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy for localized infections–State of the art. Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther. 2009;6:170–188. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krespi YP, Kizhner V. Phototherapy for chronic rhinosinusitis. Lasers Surg Med. 2011;43:187–191. doi: 10.1002/lsm.21042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gholam P, Kroehl V, Enk AH. Dermatology life quality index and side effects after topical photodynamic therapy of actinic keratosis. Dermatology. 2013;226:253–259. doi: 10.1159/000349992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clark C, et al. Topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid photodynamic therapy for cutaneous lesions: Outcome and comparison of light sources. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:134–141. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun L, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis and computational study of the Y366 active site in Bacillus subtilis protoporphyrinogen oxidase. Amino Acids. 2009;37:523–530. doi: 10.1007/s00726-009-0256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bae T, Schneewind O. Allelic replacement in Staphylococcus aureus with inducible counter-selection. Plasmid. 2006;55:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.plasmid.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horton RM, Cai Z, Ho SM, Pease LR. Gene splicing by overlap extension: Tailor-made genes using the polymerase chain reaction. Biotechniques. 1990;8:528–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fey PD, et al. A genetic resource for rapid and comprehensive phenotype screening of nonessential Staphylococcus aureus genes. MBio. 2013;4:e00537–e12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00537-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazmanian SK, et al. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;299:906–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1081147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fujita H. 2001. Measurement of delta-aminolevulinate dehydratase activity. Curr Protoc Toxicol Chap 8:Unit 8.6.

- 57.Reniere ML, et al. The IsdG-family of haem oxygenases degrades haem to a novel chromophore. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75:1529–1538. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weiner MP, et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of double-stranded DNA by the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1994;151:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90641-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shepherd M, Dailey HA. A continuous fluorimetric assay for protoporphyrinogen oxidase by monitoring porphyrin accumulation. Anal Biochem. 2005;344:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morris GM, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morris GM, et al. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gao H, et al. Discovery of novel VEGFR-2 inhibitors. Part II: Biphenyl urea incorporated with salicylaldoxime. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;90:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bender T, Huss M, Wieczorek H, Grond S, von Zezschwitz P. Convenient synthesis of a [1-14C]Diazirinylbenzoic acid as a photoaffinity label for binding studies of V-ATPase inhibitors. Eur J Org Chem. 2007;2007:3870–3878. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Duthie ES, Lorenz LL. Staphylococcal coagulase; mode of action and antigenicity. J Gen Microbiol. 1952;6:95–107. doi: 10.1099/00221287-6-1-2-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Attia AS, Benson MA, Stauff DL, Torres VJ, Skaar EP. Membrane damage elicits an immunomodulatory program in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000802. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kreiswirth BN, et al. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stauff DL, Skaar EP. Bacillus anthracis HssRS signalling to HrtAB regulates haem resistance during infection. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:763–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sterne M. Avirulent anthrax vaccine. Onderstepoort J Vet Sci Anim Ind. 1946;21:41–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dailey TA, Dailey HA. Human protoporphyrinogen oxidase: Expression, purification, and characterization of the cloned enzyme. Protein Sci. 1996;5:98–105. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560050112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]