Significance

Here we reassess the conceptual framework of insect diapause as a dynamic succession of endogenously and exogenously driven changes in physiology (“physiogenesis”) by assaying the gradual dynamics in the transcriptome as insects traverse the diapause developmental program. We show the objectivity and eco-physiological relevance of the different phases of diapause development by describing unique transcriptional profiles in each phase. Accordingly, the concept should serve future researchers as a general platform for the unification of timing scales and the interpretation of various “-omics” data obtained in diverse insect species encountering different ecological situations. We argue such standardized phasing of diapause development is critical for further molecular dissection of the mechanistic basis of insect diapause.

Keywords: insects, diapause, development, transcriptomics, microarrays

Abstract

Insects often overcome unfavorable seasons in a hormonally regulated state of diapause during which their activity ceases, development is arrested, metabolic rate is suppressed, and tolerance of environmental stress is bolstered. Diapausing insects pass through a stereotypic succession of eco-physiological phases termed “diapause development.” The phasing is varied in the literature, and the whole concept is sometimes criticized as being too artificial. Here we present the results of transcriptional profiling using custom microarrays representing 1,042 genes in the drosophilid fly, Chymomyza costata. Fully grown, third-instar larvae programmed for diapause by a photoperiodic (short-day) signal were assayed as they traversed the diapause developmental program. When analyzing the gradual dynamics in the transcriptomic profile, we could readily distinguish distinct diapause developmental phases associated with induction/initiation, maintenance, cold acclimation, and termination by cold or by photoperiodic signal. Accordingly, each phase is characterized by a specific pattern of gene expression, supporting the physiological relevance of the concept of diapause phasing. Further, we have dissected in greater detail the changes in transcript levels of elements of several signaling pathways considered critical for diapause regulation. The phase of diapause termination is associated with enhanced transcript levels in several positive elements stimulating direct development (the 20-hydroxyecdysone pathway: Ecr, Shd, Broad; the Wnt pathway: basket, c-jun) that are countered by up-regulation in some negative elements (the insulin-signaling pathway: Ilp8, PI3k, Akt; the target of rapamycin pathway: Tsc2 and 4EBP; the Wnt pathway: shaggy). We speculate such up-regulations may represent the early steps linked to termination of diapause programming.

The obligatory diapause is a fixed component of the insect’s ontogenetic program, whereas the facultative diapause represents an optional alternative pathway to direct ontogeny. Facultative diapause (herein referred to as “diapause”) is a state of environmentally programmed and centrally regulated developmental arrest, usually accompanied by metabolic suppression, which secures survival over unfavorable seasons and synchronizes the insect life cycle to the seasonality of abiotic environmental factors and biotic interactions (1–5). An improved knowledge of diapause is essential for understanding insect life cycles and for the development of management strategies for economically important insect pests (6) and accurate predictions of insect populations’ responses to climate change (7).

At a specific sensitive stage, insects perceive environmental token stimuli (any stimulus that signals the upcoming seasonal change in advance, most often the photoperiod) that reliably mark seasonal time (calendar) and switch from direct development to the diapause pathway, typically long before the adverse period arrives. (Note: in this paper, “direct development” refers to an ontogenetic pathway without intervening diapause.) It is well established that switching between direct development and diapause is controlled by the decrease or absence of signaling of the basic developmental hormones, juvenoids and/or ecdysteroids (8, 9). However, any further generalizations about insect diapause are strongly complicated by three facts. First, the insect taxon is enormously rich and diverse. It is believed that diapause responses evolve polyphyletically and very rapidly in different insect lineages as they encounter diverse environmental adversity (10–13). Second, different insect species enter diapause in different ontogenetic stages that differ widely in the complexity of body architecture and physiology (9). Third, different insect species enter diapause under various environmental contexts. Thus, hibernation is widespread in polar and temperate regions, aestivation often occurs in Mediterranean and other dry climate zones, and tropical diapauses may respond to seasonality primarily in biotic interactions (14–16). Despite this diversity in insect diapause responses, several phenotypic features occur almost ubiquitously: developmental arrest, metabolic suppression, and environmental stress resistance (17), so that some authors have proposed the notion of a common genetic “toolkit” for diapause (18, 19). According to this scheme, some common diapause-induced gene-expression profiles might be shared across insect (or even across invertebrate) taxa. However, when comparing transcriptional profiles linked to dormancy in three invertebrate species (flesh fly, fruit fly, and nematode), Ragland et al. (20) found little support for the genetic toolkit hypothesis and concluded that there may be many transcriptional strategies for producing physiologically similar dormancy responses. One additional generalization on insect diapause posits that diapausing insects, although developmentally arrested, pass through a stereotypic succession of eco-physiological phases called “diapause development” or “physiogenesis” (1). This generalization also has caused controversies in the past (4, 21, 22); in particular, the separation of and naming of the successive phases remains unstandardized and is sometimes criticized as artificial (for a review, see ref. 23).

We used custom microarrays to compare gene-expression profiles for 1,042 mRNA transcripts in the larvae of the drosophilid fly Chymomyza costata. The genes were arbitrarily selected to cover broadly the major structures and processes known or suggested to be involved in insect diapause expression: biological clocks, hormones and signaling cascades, regulators of the cell division cycle, energy metabolism and detoxification, response to temperature stimulus and cryoprotection, cytoskeleton, biological membranes, and transport systems. In addition to comparing diapause and nondiapause animals, we focused mainly on comparing the successive eco-physiological phases of diapause development, namely, induction, initiation, maintenance, and termination (sensu ref. 23). We also distinguished between the natural (horotelic, sensu ref. 2) and the unnatural (tachytelic, sensu ref. 2) mechanisms of diapause termination stimulated by cold and by a long-day photoperiod, respectively. Our primary aim was to assess whether the phases of diapause development are characterized by specific transcriptional profiles that would demonstrate their physiological relevance objectively. Further, we compare the phase-specific transcriptional responses observed in C. costata with the analogous responses published for other insects with the aim of assessing the scope of evolutionary conservation/convergence in the transcriptional level of diapause regulation (i.e., addressing the applicability of the hypothetical genetic toolkit for diapause).

Results and Discussion

Differences Between Diapause and Nondiapause Early Third Instars.

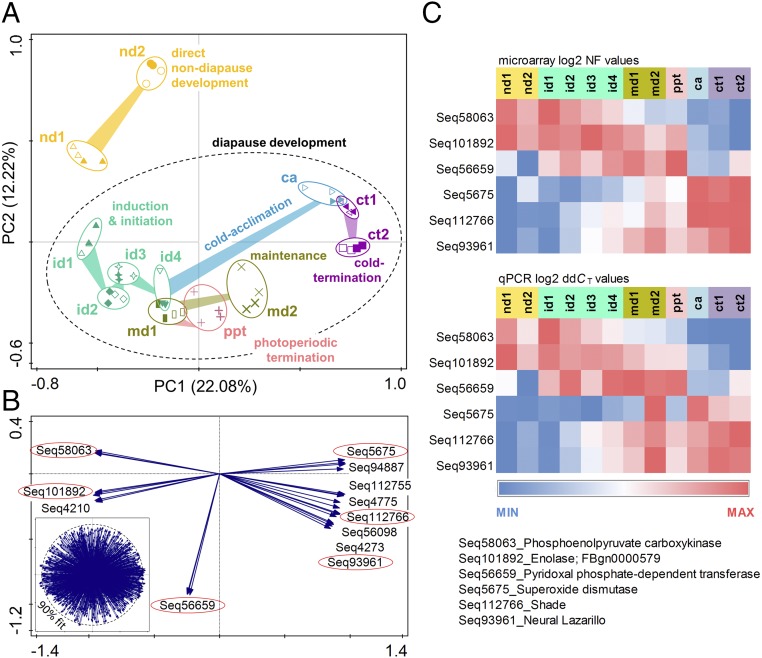

The clusters of transcriptional profiles of larvae destined for direct development and larvae destined for diapause induction and initiation (nd1 and id1 larvae, respectively; for an explanation of abbreviations, see Fig. S1 and Table S1) are clearly separated along the principal component 2 (PC2) axis on the principal component 1 (PC1) vs. PC2 ordination plot of the principal components analysis (PCA) (Fig. 1A). Early third-instar larvae (nd1 and id1) are most sensitive to photoperiodic signal. The nd1 larvae will continue in direct development, whereas the id1 larvae are destined to diapause development (24). We found 79 genes differentially expressed (DE) in the id1 and nd1 samples (Dataset S1, Excel sheet id1 vs. nd1), comprising 7.7% of the total number of 1,042 sequences printed on a custom microarray. In an earlier study (25) we compared the transcriptional profiles of similar larvae (at the same ontogenetic stages) using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and found 1,313 DE sequences, comprising 6.2% of a total 21,327 sequences. Further, the identity of DE sequences showed good overlap between two studies: 37 of 45 (82.2%) up-regulated DE sequences in this study were also up-regulated in the earlier study; similarly, 26 of 34 (76.5%) down-regulated DE sequences in this study were also down-regulated in the earlier study (with a 1.5-fold difference as a threshold for up- or down-regulation). In the RNA-seq study, the short-day–reared, diapause-destined larvae (designated as “id1” in this study) showed down-regulation of several key genes involved in 20-hydroxyecdysone (20HE) biosynthesis and perception, indicating an inhibition of the developmental hormone signaling. The transcriptional pattern further suggested that the hormonal change was translated into the down-regulation of a series of other transcriptional factors, finally resulting in cessation of the cell-division cycle and deep restructuring of metabolic pathways, all robustly reflected in transcriptional patterns (25). Thus, the separation of id1 vs. nd1 clusters on the PC1 vs. PC2 plot (Fig. 1A) is validated by our earlier RNA-seq analysis. Hence, the separation of id1 vs. nd1 clusters can serve as an accurate gauge for the interpretation of the separation between individual phases of nondiapause or diapause development. Direct validation analysis, performed with six selected sequences that exhibited the highest fit to the PCA model (Fig. 1B), showed a very good match between microarray and RT-qPCR methods (Fig. 1C).

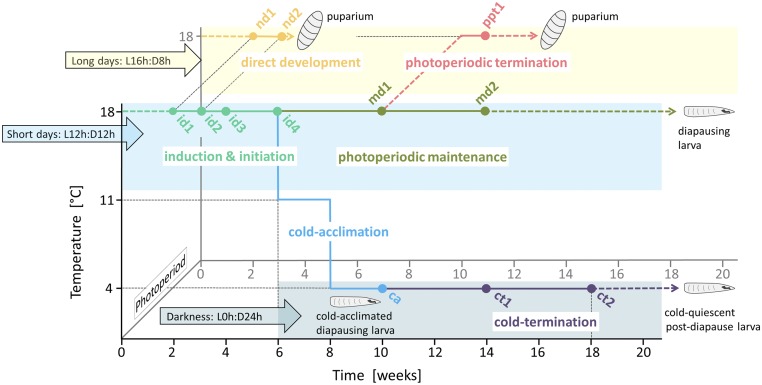

Fig. S1.

The experimental design used to sample the third-instar larvae of C. costata for analysis of gradual changes in their transcriptomic profile during direct and diapause development. Each point represents a sample/treatment (for more details, see SI Text and Table S1). Larvae undergo direct development to puparium under long days and a temperature of 18 °C (nd1, nd2). Larval diapause is induced and initiated under short days and a temperature of 18 °C (id1, id2, id3, id4). Diapause can be maintained (md1, md2) until all larvae die at short days and temperature of 18 °C. Alternatively, diapause can be terminated by exposure to long days and temperature of 18 °C (ppt) or by exposure to low temperatures and constant darkness (ct1, ct2). Low temperatures also trigger cold acclimation (ca).

Table S1.

Samples and description of C. costata third-instar larvae sampled for experiments

| Sample | Phase of ontogeny | Age, days of third instar and/or weeks since egg laying | Conditions, photoperiod and temperature |

| Nd1 | Direct development | 2 d/2 wk | LD/18 °C |

| Nd2 | 9 d/3 wk | ||

| Id1 | Diapause induction and initiation | 2 d/2 wk | SD/18 °C |

| Id2 | 9 d/3 wk | ||

| Id3 | 4 wk | ||

| Id4 | 6 wk | ||

| Md1 | Diapause maintenance | 10 wk | SD/18 °C |

| Md2 | 14 wk | ||

| Ppt | PP termination | 11 wk | SD10w → LD/18 °C |

| Ca | Cold acclimation, termination by cold | 10 wk | SD6w → DD/11 °C8w → DD/4 °C |

| Ct1 | 14 wk | DD/4 °C | |

| Ct2 | 18 wk |

DD, constant darkness; LD, long day; PP, photoperiodic; SD, short day; SD6w → DD, transfer from SD to DD at age 6 wk; SD10w → LD, transfer from SD to LD at age 10 wk.

Fig. 1.

Gradual change in transcriptional profiles associated with direct and diapause development in third-instar C. costata larvae. (A) Results of PCA analysis exhibiting a clear separation of treatment clusters representing direct nondiapause development (nd1, nd2) and diapause development (id1, id2, id3, id4, md1, md2, ppt, ca, ct1, and ct2). The ellipses were arbitrarily drawn around replicated arrays to help resolution. All treatments had four replicates (three biological replicates plus one technical replicate; solid symbols are used to highlight two technical replicates of one entire microarray). For further explanations, see text, Fig. S1, and Table S1. (B) Eigenvectors are shown for sequences that best fit the PCA model (eigenvector loading >90%). Red ellipses highlight six target sequences selected for validation of microarray analysis by RT-qPCR. The Inset shows the distribution and 90% cutoff circle for all 3,126 eigenvectors (1,042 sequences, each represented in triplicate on our custom microarray). (C) Validation of microarray results using RT-qPCR. (Upper) The heat map shows the log2-normalized fluorescence value (NF) of the microarray spot signals of six target sequences. (Lower) The heat map shows log2 relative mRNA abundance (ddCT, mean of five references per target sequence) in RT-qPCR analysis. The blue–red color scale displays a span between the minimum and maximum values in each single row of the heat map.

Separation of Successive Phases of Diapause Development.

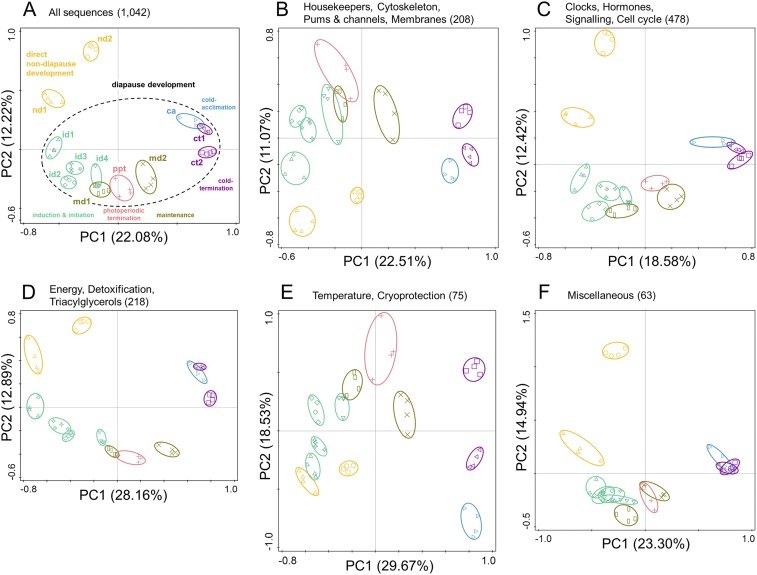

The separation of individual phases of diapause development is obvious in the PCA ordination plot (Fig. 1A). We performed five additional PCA analyses using five different subsets of microarray sequences rather than analyzing all 1,042 sequences together. The results of such subset PCA analyses (Fig. S2) confirmed that the clustering and separation of successive phases of diapause development remain distinct, no matter which subset of sequences is used in the analysis. The specific transcriptional patterns of individual diapause phases are robust and cover different gene categories/ontologies. We discuss the phases of diapause development in their logical order below.

Fig. S2.

Results of additional PCA analyses of transcriptional profiles in larvae of C. costata performed with five different subsets of arrayed sequences. (A) The results of PCA analysis using all 1,042 array sequences (these are the results presented in Fig. 2A and are shown here for comparison). (B–F) The results of PCA analyses using subsets of arrayed sequences. (B) Functional classes: housekeepers, cytoskeleton, pumps and channels, membranes (208 sequences in total). (C) Functional classes: clocks, hormones, signalling, cell cycle (208 sequences in total). (D) Functional classes: energy, detoxification, triacylglycerols (218 sequences in total). (E) Functional classes: temperature, cryoprotection (75 sequences in total). (F) Miscellaneous (63 sequences in total).

Diapause induction and initiation.

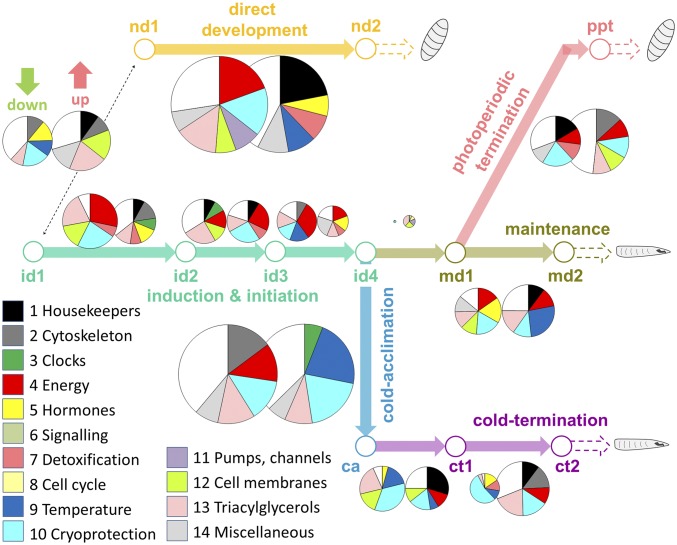

In C. costata, the phases of diapause induction and initiation proceed in immediate succession and are even partially overlapping. Diapause induction is a gradual process in which the environmental token stimuli (photoperiod, thermoperiod) are perceived and, in an interplay with modifying and directly limiting factors (temperature, population density, diet quantity and quality), are transduced into the hormonal changes that cause the expression of a complex diapause phenotype (23, 24). Diapause initiation is characterized by transiently high metabolic activity and continuation of feeding and locomotion (although development is already arrested), securing various needs linked to preparations for the upcoming long period of behavioral inactivity and metabolic suppression (23). The process of diapause induction and initiation culminates at an age of ∼6 wk in C. costata (26). Fig. 2 documents how the transcriptional profile in C. costata larvae changes gradually during the progression through diapause induction and initiation. The quantitative aspect of the gradual transcriptional change can be judged by comparing the sizes of the pie charts (the bigger the pie, the larger is the proportion of DE sequences). Color coding of segments shows the gene functional categories, helping to identify visually the categories with the highest relative proportions of DE sequences and allowing a rough comparison of the qualitative aspect of the gradual transcriptional change (for more details, see Dataset S1). We can see that the magnitude and complexity of the changes gradually decrease with progression of diapause from 1d2 to id4, i.e., (id2 vs. id1), 6.3% DE sequences of a total 1,042 sequences are DE sequences; (id3 vs. id2), 5.2%; and (id4 vs. id3), 3.9%. The qualitative aspect of transcriptional changes also tends to evolve gradually, as indicated by the changes in gene categories that exhibit the highest relative proportion of DE sequences and also by the relatively small overlap of DE sequences between the successive comparisons/phases: i.e., for (id2 vs. id1) vs. (id3 vs. id2), 18.7% of 111 DE sequences overlap, whereas for (id4 vs. id3) vs. (id3 vs. id2), 17.9% of 95 DE sequences overlap (Dataset S1).

Fig. 2.

Separation of the different phases of diapause development in C. costata larvae according to gradual changes in their transcriptional profile. The pie charts indicate quantitative (shown by the relative size of the pie) and qualitative (colors of segments) aspects of the gradual change (down-regulation, left pie; up-regulation, right pie) in the transcriptomic profile during the development of third-instar larva under direct development or diapause-promoting conditions. The size of each pie is directly proportional to the percentage of DE sequences detected (of a total 1,042 arrayed sequences) for the respective treatment comparison (e.g., nd2 vs. nd1). The color of each segment codes for a gene-functional category (see key). Up to five (or six) gene-functional categories with the highest percentage of DE sequences are shown in a specific pie. For more details, see text and Dataset S1.

Diapause maintenance.

The maintenance phase (md1/2) is ecologically the most explicit phase of diapause development. In this phase, the insect maintains the developmental arrest induced in earlier phases. The diapause is maintained despite the environmental conditions potentially being permissive for the continuation of development. The insects usually continue responding to inducing token stimuli that help them maintain diapause/prevent its termination. The maintenance phase is also characterized by extremely slow metabolism securing only the basic homeostatic functions. In our results, the overall static character of the maintenance phase is reflected in a very small number of DE genes: (md1 vs. id4), 0.7% DE sequences. However, we do observe that the number of DE sequences increases markedly during the subsequent phases of maintenance: (md2 vs. md1), 6.3% DE sequences (Fig. 2). In C. costata, diapause is photoperiodically maintained until practically all larvae die (24). We speculate that the increasing number of DE sequences in the later phase of maintenance (md2) may reflect a combination of at least three theoretical factors: (i) the mobilization of alternative energy substrates (when the preferred substrate becomes more limited, the alternative substrate may be recruited, thus requiring the mobilization of different genes); (ii) the need to replenish and metabolize the energy substrates by occasional feeding [we have shown that half of diapausing C. costata larvae die within 2 mo when maintained without food (24), suggesting that occasional feeding is required, and such feeding would also require the recruitment of potentially new gene sets for digestion and metabolism]; and (iii), the need to cope with increasing homeostatic imbalances (with increasing larval age, toxic metabolites may accumulate that could also induce a transcriptional response).

Diapause termination by long photoperiod.

As in many other insects, diapause termination in C. costata requires a specific stimulus: either the lengthening of day (an unnatural stimulus) that leads to tachytelic termination or exposure to cold (a natural stimulus), causing horotelic termination (2, 26). In some other insects, the termination of diapause may be spontaneous, requiring no specific environmental signal (2, 26). In C. costata larvae, the change of the photoperiodic signal from short day to long day resulted in an increase in the relative number of DE sequences: [photoperiod termination (ppt) vs. md1], 8.2% DE sequences (Fig. 2). The rate of ppt-linked change in the transcriptional profile was relatively rapid (i.e., occurring within 1 wk) and was not associated with any overtly observable morphological or behavioral changes. The larvae began their wandering behavior and pupariation only 3–4 wk after transfer to the long photoperiod. Thus, the long photoperiod-induced alteration in 8.2% of the transcriptomic profile represents the result of the perception of a token stimulus (long day) and the transduction of the signal to resuming developmental potential. Additionally, the photoperiodic termination phase is qualitatively different from the gradual changes in the transcriptome associated with diapause maintenance: only 10 of all DE sequences (6.6% of 151) overlap between the maintenance (md2 vs. md1) and photoperiodic termination (ppt vs. md1) phases.

Cold acclimation followed by diapause cold termination.

Cold termination (ct) of diapause is a long process, typically requiring 2- to 3-mo-long exposure to low temperatures in different insects (23). However, the initial temperature step-down from 18 °C to 4 °C is also an important stimulus for another complex phenotypic change, cold acclimation (ca). The larvae of C. costata become cold acclimated (i.e., their freeze-tolerance significantly increases) within relatively short exposures to cold stimuli (27). The cold-acclimation phase in C. costata larvae was characterized by relatively complex changes in the transcriptomic profile: (ca vs. id4), 19.9% DE sequences (Fig. 2), and the gene categories involved in temperature response and cryoprotection were logically those most affected (Dataset S1). We placed a number of sequences involved in the metabolism and transport of proline and trehalose into an arbitrary gene category that we termed “cryoprotection.” Proline and trehalose may play cryoprotective roles when accumulated in high amounts and distributed evenly throughout the larval body during cold acclimation (27, 28).

Next, we observed a relatively complex rearrangement of the transcriptome occurring in deeply diapausing larvae that were kept in constant darkness and at a low temperature, 4 °C (i.e., conditions generally not expected to stimulate any change, i.e. cold termination). The relative proportion of DE sequences was 5.4% for the (ct1 vs. ca) comparison and was 5.2% for the (ct2 vs. ct1) comparison (Dataset S1). Only 16 of all DE sequences (14.5% of 110) overlapped between the early (ct1 vs. ca) and late (ct2 vs. ct1) phases of cold termination, possibly indicating that the late phase of cold termination qualitatively differs from the early phase.

Genetic Toolkit of Diapause.

Since the publication of the pioneering paper of Denlinger and coworkers (29), a number of studies have described differences in gene transcription linked to insect diapause (20, 30–36). Indeed, some authors have attempted to integrate these studies and to detect commonalities in the diapause transcriptional profiles of different species, searching for the hypothetical genetic toolkit of diapause (18, 19). Two genes have been specifically suggested as potential general markers for distinguishing between diapause and direct development, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (pepck), which is up-regulated in diapause, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (pcna), which is down-regulated in diapause (18). The up-regulation of the pepck gene in the diapause context was explained as reflecting the transition between oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor environments, whereas the down-regulation of pcna, again in the diapause context, was linked to the arrest of cell-cycle progression (18). In our study of C. costata, neither pepck (Seq29 and Seq58063) nor pcna (Seq570) transcripts showed responses consistent with the predictions of the genetic toolkit hypothesis. We have found 45 up-regulated and 34 down-regulated DE genes when comparing the early phase of diapause induction (id1) with the corresponding stage of nondiapause development (nd1), in which neither pecpk nor pcna was represented (Dataset S1, Excel sheet: id1 vs. nd1). However, the pepck sequence was significantly up-regulated during direct development (nd2 vs. nd1), 0.59 log2 fold change (FC) (Seq29), and was down-regulated during the cold-acclimation phase (ca vs. id4), −0.96 log2 FC (Seq29) and −1.42 log2 FC (Seq58063). The pcna sequence was significantly up-regulated during direct development (nd2 vs. nd1), 0.77 log2 FC (Seq570). Accordingly, we agree with Ragland et al. (20) that the evolutionary conservation/convergence of different diapause responses is unlikely to be observable at the level of transcriptional patterns of isolated genes. Rather, a genetic toolkit of diapause may be reflected in the activation/inhibition of whole signaling pathways regulating the hallmark diapause-linked physiological phenotypes.

20HE, IS, and TOR signaling pathways.

Larval growth and direct development are stimulated by the developmental hormone 20HE, whereas larval diapause is classically explained by the silencing of 20HE-mediated signaling (9). In addition, the silencing of the insulin (IS) and target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling pathways has often been implicated as an important regulator of insect diapause (37–41). Active IS and TOR pathways promote cell proliferation and organismal growth (42, 43), whereas the silencing of these pathways is linked to the suppression of growth/development and enhanced stress response, phenotypic changes that are also characteristic of insect diapause (44–46) (for more details, see Fig. S3).

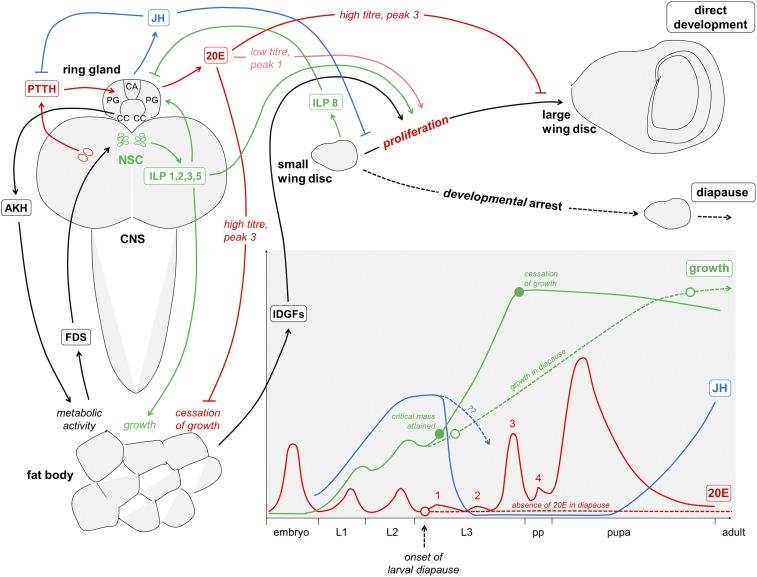

Fig. S3.

Hormonal pathways involved in the regulation of growth and development in D. melanogaster (solid lines) and some alterations linked to larval diapause in C. costata (dashed lines). The graph in lower right corner represents growth (solid green line) and the developmental hormone fluxes (JH, juvenile hormone, solid blue line; and 20E, solid red line) in the hemolymph of D. melanogaster (according to refs. 66 and 76). Larval molts are driven by pulses of circulating 20E, whereas larval (juvenile) character is maintained by high titer of JH. During the early third larval instar (L3) of D. melanogaster ontogeny, metamorphosis to the pupal stage is triggered by the suppression of JH production linked to the attainment of critical mass and, concomitantly, by a first small pulse of 20E (peak 1), which likely stimulates rapid cell proliferation in imaginal discs (77, 78). This early 20E peak 1 is suppressed in C. costata under short days; this suppression might be considered an event linked to the onset of larval diapause (25). Direct development to pupa then is driven, likely similarly in both fly species, by a succession of three 20E pulses linked to wandering (peak 2), pupariation (peak 3), and pupation (peak 4). High titer of 20E during peak 3 suppresses proliferation in imaginal discs and also causes cessation of feeding and growth in peripheral tissues (66). All 20E peaks (1–4) are probably absent in diapause-inducing/initiating larvae of C. costata reared under short days (dashed red line) (25). Although their development is arrested, diapause-initiating C. costata larvae continue to grow until the age of ∼6 wk when the final size of the diapausing larva is attained (dashed green line) (26). Fly larvae produce 20E in their prothoracic glands (PG) under the control of prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) secreted by neurosecretory cells of the brain (79, 80). JH is produced in the corpus allatum gland (CA) (81), and adipokinetic hormone (AKH), which stimulates fat body metabolic activity, is secreted from the corpora cardiaca (CC) (82). The three glands (PG, CA, and CC) are integrated into a single ring gland in fly larvae (80). ILPs are produced in a set of neurosecretory cells (NSC) of the larval brain (83). The ILPs activate proliferation and growth in peripheral tissues (such as the fat body) and imaginal discs (such as the wing disc) (43, 47, 67, 75) via pathways described in more detail in Fig. 3A. In addition, insulin signaling positively influences 20E synthesis in the PG (84, 85), and a specific insulin-like peptide (ILP8) is secreted from small imaginal discs that have not yet completed their growth program. ILP8 inhibits ecdysone production and pupariation, thereby coupling tissue growth with developmental timing (86–88). The growing fat body produces poorly characterized feedback signals (FDS), which act on brain NSC to control the secretion of ILPs (88). The fat body also produces imaginal disc growth factors (IDGFs), which cooperate with insulin to stimulate cell proliferation in imaginal discs (89). Wing discs of diapause-inducing/initiating third instars of C. costata do not receive stimulatory 20E signal (see above). It remains unclear whether and how the other stimulatory axes (IS and IDGF) are changed in diapausing larvae; nevertheless, the cell-division cycle in imaginal discs is inhibited (and/or is not stimulated), and consequently the discs stop growing (54). This cessation of growth is synonymous with the developmental arrest, i.e., diapause (dashed black line). It is known that the IS and 20HE pathways interact functionally, although the mechanistic details of this crosstalk are not sufficiently understood (90). For instance, the synthesis of ecdysone in the fruit fly's PG is positively regulated by insulin (84, 85), which in turn may couple the availability of nutrients (TOR pathway) to developmental timing regulated by ecdysone (75). Similarly, insulin receptors are present in the fruit fly's CA glands, which regulate JH synthesis (91); moreover suppression of insulin signaling correlates with low JH production (92). In summary, the growth of D. melanogaster and probably also C. costata larvae is supported by crosstalk between developmental hormones and active IS and TOR pathways that together promote the growth of tissues and the proliferation in the imaginal discs until the final appropriate size is reached and the program of metamorphosis is initiated (66).

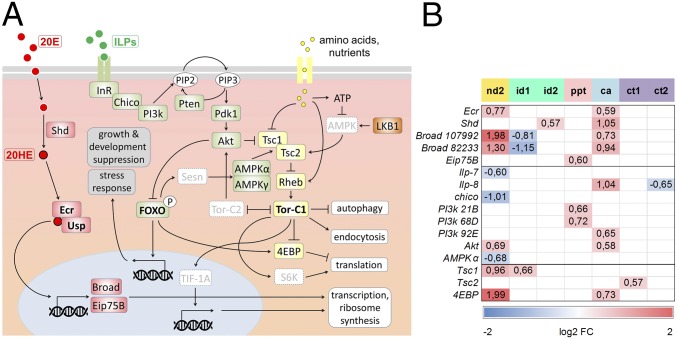

The key molecular components of the 20HE, IS, and TOR signaling pathways are well conserved throughout evolution (43, 46, 47), and a summary of these pathways presented in Fig. 3A documents that our custom array is well-represented with putative C. costata gene probes of the 20HE, IS, and TOR pathways. However, relatively few transcriptional rearrangements were observed in 20HE, IS, and TOR pathways during the diapause development of C. costata larvae (Fig. 3B; for more details, see Dataset S1, Excel sheet: 20HE, IS, TOR). Mechanistic interpretation of microarray results is difficult for general and specific reasons: The correspondence between mRNA abundance and the activity of the protein product is generally limited; many elements of the IS and TOR cascades are regulated via phosphorylation rather than by transcription; our study lacks resolution at the tissue level; and our study relies on the analysis of transcripts in C. costata that were detected as structural homologs of Drosophila melanogaster genes, but no functional validation is available for most of them. Therefore, we provide only a brief description of observed changes that, at this stage, are hypothetically linked to diapause development (SI Results: Extended Discussion Related to Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cooperation of 20HE, IS, and TOR signaling pathways in the regulation of fly larva growth and development. (A) The elements of signaling pathways recognized in D. melanogaster larvae and their putative homologs (highlighted in colored rectangles) represented on our C. costata custom microarray. The 20HE signaling cascade is in red, forkhead box O (FOXO) pathway components are in green, TOR pathway components are in yellow, and the serine-threonine kinase LKB1-activated pathway is shown in brown. White rectangles with gray font indicate elements not represented on our custom microarray. (B) Results of microarray transcriptional analysis in C. costata. Only results in which statistically significant up- or down-regulations of signaling pathway components were observed are shown (the numbers in each box are log2-transformed average FCs in expression). For more details, see SI Results: Extended Discussion Related to Fig. 3 and Dataset S1, Excel sheet: 20HE, IS, TOR.

Wnt signaling pathway.

Cold termination of diapause is a process with an insufficiently understood physiological basis. During diapause termination, developmental potential is covertly restored but need not be overtly realized in the form of resumption of morphogenesis and development (23). In the laboratory, most diapauses can be terminated rapidly after the diapausing animals are treated with developmental hormones, hormone analogs, or some organic solvents (9). During the complex cascades following hormonal treatment, transcriptional changes were described in the pupae of the flesh fly Sarcophaga crassipalpis (20, 48). However, to understand the natural process of horotelic diapause termination in the field (or, in the laboratory, but without artificial manipulation of the endocrine system), we need to know the upstream events preceding the change in hormonal signaling. In diapausing pupae of S. crassipalpis, for instance, the spontaneous increase in ultraspiracle expression during prolonged exposure to cold might represent one of the upstream events that are directly linked to diapause termination (49). Some other genes were identified as potential early regulators of diapause termination in the embryos of Bombyx mori (50, 51) and in the larvae of Wyeomyia smithii (34). In the pupae of Rhagoletis pomonella, the elements of a calcium-dependent branch of the Wnt signaling pathway were found to be moderately up-regulated in late diapause just before termination by cold (52). The Wnt pathway is one of the short-range, organ-autonomous (paracrine) signaling systems controlling final cell numbers in larval imaginal discs and thereby controlling organ size in the adult (53). Because the suppression of imaginal disc proliferation is a hallmark of diapause in C. costata (54), the Wnt pathway is clearly an important candidate for diapause regulation. However, our custom array represents only nine genes putatively belonging to Wnt pathway in C. costata, limiting any speculations about their role in diapause. Two of the Wnt pathway-linked transcripts [Seq59352, basket (JNK) and Seq81736, c-jun] were up-regulated during cold acclimation; this up-regulation seems counterintuitive, because these genes are positive regulators of gene transcription and the cell cycle, respectively. In contrast, the concomitant up-regulation of shaggy (Seq2621) during the maintenance of diapause and cold acclimation may inhibit the Wnt cascade and thus counteract the stimulation of the cell-division cycle potentially caused by up-regulated c-jun. Shaggy is a glycogen synthase kinase 3, GSK-3β, and is a key component of the β-catenin destruction complex. It functions as a negative regulator in the canonical Wnt cascade (53). It remains currently unknown whether the cold-induced transcriptional up-regulation of some positive elements (such as basket and c-jun) of the Wnt pathway, which is counteracted by the up-regulation of negative elements (such as shaggy), is an early component of diapause termination. A concomitant up-regulation in positive and negative elements during the cold-acclimation phase also occurs in the 20HE, IS, and TOR pathways (for more details, see SI Results: Extended Discussion Related to Fig. 3).

SI Results: Extended Discussion Related to Fig. 3

20HE, IS, and TOR Signaling Pathways.

Circulating 20-ecdysone (20E) is converted to the active hormone 20HE upon hydroxylation by P450 monooxygenase Shade (Shd) in peripheral tissues (62). 20HE binds to cytoplasmic receptors consisting of two proteins, the ecdysone receptor (Ecr) and ultraspiracle (USP) (63). The hormone–receptor complex binds to 20HE response elements in the promoter region of target genes and activates transcription cascades of early- and late-response genes (64) linked to molting and/or metamorphosis (i.e. promoting direct development). Broad and Eip75B are among the early-induced genes (65). Insulin-like peptides (ILPs) signal through a single insulin receptor (InR) linked to its substrate Chico, which initiates the phosphorylation transduction cascade involving PI3K, phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1), and the protein kinase Akt (66, 67). The lipid phosphatase PTEN reverses the activity of PI3K and thus inhibits insulin signaling (68). Active Akt phosphorylates (inhibits) FOXO, resulting in its retention in cytoplasm and silencing its transcriptional activity. In contrast, FOXO is activated when ILPs are not signaling. Active FOXO stimulates the translation repressor 4E-binding protein (4EBP) (69), and it also moves to the nucleus where it drives the transcription of a large number of genes involved in suppression of growth, development, aging, and enhanced stress response (37, 39, 44, 45). Active FOXO may also inhibit the TOR pathway via Sestrin (Sesn) and AMPKα and γ, which increase the inhibition of TOR driven by the Tuberous sclerosis 1/Tuberous sclerosis 2 (Tsc1/Tsc2) complex (70). The TOR pathway is stimulated by high concentrations of intracellular amino acids and/or by AMPK, which senses cellular energy (ATP) levels and is activated by LKB1 protein kinase (66). The active Tsc1/Tsc2 complex integrates several signaling pathways (71) and can suppress the small GTPase Ras homolog in brain (Rheb) (72), which in turn activates TOR complex 1 (Tor-C1) (43). The negative feedback loop between Akt and Tor-C1 is mediated by Tor-C2 activity (73). Tor-C1 activity promotes cell and organismal growth by supporting transcription, ribosome synthesis, translation, and endocytosis while suppressing autophagy (43, 67, 74). Tor-C1 inhibits 4EBP while activating the ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) and transcriptional intermediary factor 1A (TIF-1A) (73, 75).

Results of Microarray Analysis in C. costata.

-

i)

The transcriptional changes found in id1 larvae (compared with nd1 larvae) are consistent with silencing of 20HE signaling: down-regulation of Broad, one of the early genes coding for transcription factors that induce response to the 20HE signal in a broad spectrum of secondary genes. They also are consistent with down-regulation of the TOR pathway: up-regulated Tsc1 is a negative regulator of TOR.

-

ii)

The up-regulation of Shd in id2 larvae is hard to reconcile with diapause induction. Shade codes for P450 monooxygenase that is expressed in peripheral tissues and hydroxylates the ecdysone to the active hormone, 20HE.

-

iii)

Photoperiodic termination of diapause (ppt) was associated with up-regulation of one of the ecdysone-induced early genes, Eip75B and two isoforms of PI3K (PI3K 21B, PI3K 68D). These changes, although in line with resuming development, are too isolated to allow speculation about their physiological meaning.

-

iv)

Cold acclimation (ca) was accompanied by transcriptional up-regulation of several elements of 20HE signaling: Ecr, Shd, and Broad. It remains unclear whether such up-regulations are an early part of diapause termination. In cold-acclimated larvae, the transit toward metamorphosis is directly blocked by low temperature. Moreover, other up-regulations linked with cold acclimation, namely PI3K 92E and Akt (suggesting activation of the FOXO pathway), Tsc2 and 4EBP (suggesting inhibition of the TOR pathway and translational activity), and Ilp-8 (suggesting inhibition of ecdysone production), may support blockade of growth and development before diapause becomes terminated by cold.

-

v)

We found only two transcriptional changes in the array-represented elements of the 20HE, IS, and TOR pathways during the 8-wk-long exposure to constant 4 °C: The expression of Tsc2 (inhibitor of TOR pathway) was up-regulated during the early part of cold termination, and the expression of Ilp-8 was down-regulated during the late part of cold termination. Both changes are consistent with diapause termination. The up-regulation of Tsc2 may contribute to the blockade of growth and development, and the down-regulation of Ilp-8 may release the inhibition of ecdysone production that was imposed earlier during the cold-acclimation phase (see point iv above).

Materials and Methods

For a detailed description of materials and methods, see SI Materials and Methods.

Staging of Diapause Development.

Larvae of C. costata (Diptera: Drosophilidae) were cultured under conditions either promoting direct development to the pupa and adult stages or inducing diapause in the fully grown third-instar larval stage (Fig. S1 and Table S1 for a schematic overview of the experimental design). Direct development was promoted under a constant temperature of 18 °C and a long-day photoperiod (16 h light:8 h darkness), whereas diapause was induced by a constant temperature of 18 °C and a short-day photoperiod (12 h light:12 h darkness). Under these conditions, all individuals responded reliably to the photoperiodic signal (24, 26, 55). Larvae were sampled at different phases of their nondiapause or diapause development based on our earlier observations (23, 24, 26).

Analysis of Transcriptomic Patterns Linked to Diapause Development Using Custom Microarrays.

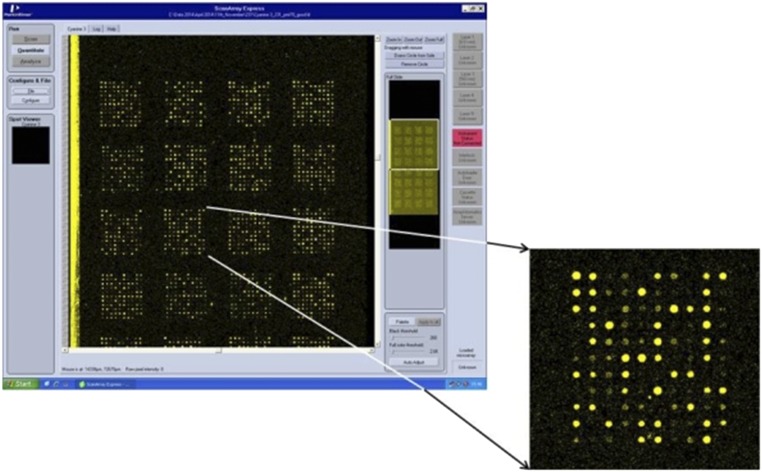

Transcriptomic profiling was based on 1,042 candidate sequences arbitrarily selected from a published Illumina RNA-seq database that contains 21,327 putative mRNA transcripts of C. costata (ArrayExpress accession E-MTAB-3620) (25). The selected genes broadly cover major structures and processes known or suggested to be involved in insect diapause expression. The complete list of the analyzed sequences is given in Dataset S1, Excel sheet: List. All other details on the processing of sampled larvae, extraction of total RNA, conversion of RNA to cDNA and labeling it with cyanine-3-dCTP (Cy3), selection of candidate sequences, designing and synthesis of the probes, printing the custom microarrays, hybridization and scanning of arrays, quantification of fluorescence signal (Fig. S4), technical validation using qPCR (Table S2), and statistical analysis of results are specified in SI Materials and Methods. Differential gene-expression analysis between consecutive time points was performed to assess the gradual dynamics in transcriptomic patterns as the insects traversed diapause or nondiapause development. In addition, unconstrained PCA was used to reveal clustering effects in global transcriptomic profiles of all treatments compared at a single statistical test.

Fig. S4.

An example of a C. costata custom microarray. The PrintScreen from ScanArray Express v. 4.0.0.0004 software (Perkin-Elmer) used to analyze the hybridized microarrays that were previously scanned using a ScanArray Gx Microarray Scanner (PerkinElmer) at a resolution of 5 µm. The microarray has 34 fields, each containing 110 spots (3,740 spots in total). The 3,126 spots are occupied by DNA probes (3 × 1,042 sequences, each printed in technical triplicate). Further details on microarray content and arrangement (including the GAL file) are available from the authors upon request.

Table S2.

Sequences selected for technical validation of microarray results by RT-qPCR

| Sequence ID | FlyBase ID | Gene, D. melanogaster | Primer sequence, 5′→3′ | Product length, bp |

| Target sequences | ||||

| Seq58063_Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase | FBgn0034356 | CG10924 | TATGGCGCAAAGTGGACGTC | 100 |

| ATTGTCACCGAAACCAGGCC | ||||

| Seq101892_Enolase | FBgn0000579 | CG17654 | TCAGGATCATTGGGACGCCT | 158 |

| CTGTGCCGATCTGGTTGACC | ||||

| Seq56659_Pyridoxal phosphate-dependent transferase | FBgn0037186 | CG11241 | GTCCATACAAGGTGTGGGCG | 124 |

| ACGTCCAAAGCCAGTTTGCA | ||||

| Seq5675_Superoxide dismutase | FBgn0003462 | CG11793 | TTTGGGCAAGGGTGGACATG | 71 |

| TGACACCGCAACCAATACGG | ||||

| Seq112766_Shade | FBgn0003388 | CG13478 | CTATGGGCTGGGTCTGTGGA | 176 |

| TAAGAAAGACGCTGCGCAGG | ||||

| Seq93961_Neural lazarillo | FBgn0053126 | CG33126 | GTGCTCTATGTGGCGTCTGG | 87 |

| ACGCCTCCAAGTCGAAGGTA | ||||

| Reference standard sequences | ||||

| Seq4254_beta-Tubulin at 56D | FBgn0003887 | CG9277 | ACATCCCGCCCCGTGGTCTGAA | 257 |

| CTGCTCCTCCTCGAACTCGGAGTC | ||||

| Seq82837_Ribosomal protein L19 | FBgn0002607 | CG2746 | CCGAGAAGCAGCGCAGTAAA | 131 |

| CTTGGCGTGCAGAGCGATAA | ||||

| Seq110583_Ribosomal protein L32 | FBgn0002626 | CG7939 | ATGCTAAGCTGTCGGTGA | 202 |

| GAATCCGGTGGGCAGCAT | ||||

| Seq58622_Ribosomal protein S27A | FBgn0003942 | CG5271 | TGGTCGCACTCTATCCGACT | 89 |

| TCTTGCGTTTCTTGGCACCA | ||||

| Seq79068_Ribosomal protein S11 | FBgn0033699 | CG8857 | GTGAAACCCGGCATCACCAA | 165 |

| GCGTACAATGCCGGTCAGAA | ||||

SI Materials and Methods

Insects.

The C. costata adult flies were originally collected in the wild in 1983, in Sapporo (43.06°N, 141.35°E), Hokkaido, Japan. Since then, the insect culture has been maintained in the laboratory on an artificial diet as described earlier (56). All experiments were conducted in MIR154 incubators (Sanyo Electric). Females laid eggs under a constant temperature of 18 °C and a long-day photoperiod (16 h light:8 h dark); for more details see ref. 24. The egg batches (∼100–200 eggs) collected over 1–2 consecutive days were either kept under long-day conditions or were transferred to short-day conditions (12 h light:12 h dark) at a constant temperature of 18 °C. Embryonic development encompasses ∼3 d at 18 °C at either photoperiod (24, 26).

Sampling.

Third-instar C. costata larvae were sampled at different phases of their nondiapause or diapause development as depicted in Fig. S1 and described in Table S1. Briefly, most larvae undergo molting from the second to the third larval instar on day 12 after egg laying, regardless of photoperiodic conditions. The further developmental destiny of the larvae is determined by the photoperiod. Under long days, larvae start wandering behavior and pupariation on day 22 after egg laying (or on day 10 of the third instar). Under short days, all larvae cease development of primordial adult cells and structures (i.e., induce diapause) approximately between days 2 and 9 of the third-instar stage (54). Larvae next initiate diapause, meaning that they continue feeding and growing until they attain maximum weight (∼2.2–2.3 mg), and the intensity of their diapause gradually increases to a maximum; both processes culminate at age of ∼6 wk (26). In C. costata, the distinction between the phases of diapause induction and initiation is somewhat arbitrary, because the two phases partially overlap. In other insects (for instance those with maternally induced diapause) the two phases are clearly separated, not only in time but also in ontogeny, by an intervening period of direct development (23). After the diapause is induced and initiated, the larvae continue in diapause development along three optional axes. The first is maintaining diapause under constant 18 °C and short days. During the maintenance phase, the larvae do not move and gradually lose weight until most of them die, within ∼7 mo. The second is terminating diapause in response to the photoperiodic signal (this way of termination does not occur in nature); larvae respond to the transfer from short days to long days at any time during the maintenance phase by resuming development and pupariation; typically, larvae require a long time, 20–28 d on average, for postdiapause development and pupariation when diapause is photoperiodically terminated. The third is cold acclimating and, consecutively, terminating diapause by responding to cold (this way of termination occurs in nature). A brief exposure to cold (such as 2 wk at 11 °C followed by 2 wk at 4 °C, as used in this study) is not sufficient to terminate diapause but is fully sufficient to attain high levels of freeze tolerance (24, 28). Long exposure to cold, 2–3 mo on average, is required to terminate diapause in all individuals (26). During the termination phase, larvae lose their sensitivity to the photoperiodic signal, become developmentally synchronized, and shorten the time required for postdiapause development and pupariation to a minimum of 9–10 d on average.

To minimize the potential effect of diurnal fluctuations in gene expression, the larvae were sampled at six different zeitgeber times (ZT) on each sampling day: at ZT 2, 8, 14, 18, 20, and 22 under long days and at ZT 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and 22 under short days. In this way, three subsamples were taken during the photophase and another three subsamples were taken during the scotophase. Each subsample consisted of a pool of four larvae, so that each sample represented a pool of 24 larvae. Each sample was taken in three biological replicates for a total of 72 larvae. In the case of diapause phases that were maintained in constant darkness and 4 °C (i.e., ca, ct1, and ct2), all 24 larvae were taken at a single time, between 8 and 9 AM. All larvae were washed out of the larval diet, transferred into 400 µL of ice-cold RiboZol RNA Extraction Reagent (Amresco) in 1.5-mL microvials, cut immediately into small pieces with scissors, and stored at −80 °C until further processing.

C. costata Custom Microarray Design and Production.

We manually selected 1,042 candidate sequences covering a broad selection of structures and processes likely to be involved in insect diapause expression from a published Illumina RNA-seq database (ArrayExpress accession E-MTAB-3620), which contains 21,327 putative mRNA transcripts of C. costata (25). To extract the relevant coding sequences in C. costata, we used the known protein sequences of D. melanogaster and blasted them against our database. We then ran OligoArray 2.1 (57) to design the microarray probes with the following parameters: length, 50–60 nt; melting temperature (Tm), 88–95 °C, GC composition, 35–65% within 1,500 nt of the 3′ UTR; maximum Tm for structure, <65 °C; and maximum Tm for hybrid, <65 °C. The oligonucleotide probes then were synthesized by Eurogentec with a C6 amino group attached at their 5′ end. The probes were processed to generate single-stranded oligo probes and were covalently attached to the slide surface with end-on orientation to ensure efficient hybridization and increased sensitivity, as previously described (57). The probes were printed on PowerMatrix slides (Full Moon BioSystems) using a QArray 2 machine (Genetix) at the FlyChip facility of the Cambridge Systems Biology Centre, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

Insect Sample Processing.

Total RNA was isolated from samples of larvae stored in RiboZol at −80 °C and diluted to 1 µg/µL in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. Seven micrograms of total RNA were taken from each sample and treated with DNase I (Ambion, Life Technologies) followed by the first-strand cDNA synthesis primed with an Oligo(dT)23-anchored primer (Sigma-Aldrich) using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). The second DNA strand was synthesized using DNA polymerase I and was treated with RNaseH (both from Invitrogen). Next, dsDNA was purified using Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-up System (Promega). One microgram of dsDNA was labeled with Cy3 (PerkinElmer) using Klenow fragment polymerase and the BioPrime DNA Labeling System (Invitrogen). Unincorporated dye was removed using the Illustra AutoSeq G-50 Dye Terminator Removal Kit (GE Healthcare). The volume of Cy3-labeled DNA sample was reduced to 2–5 µL using SpeedVac treatment at room temperature for ∼30 min. Finally, 2 µL of sonicated salmon sperm DNA (Invitrogen) was added to the sample as a blocking agent, and the sample was used immediately for hybridization onto microarrays. There were three levels of replication: (i) technical triplicates of each spot on the microarray, (ii) technical replication of one entire microarray per treatment (A′ or B′), and (iii) biological replication of triplicate samples for each treatment (separate pools of larvae: A, B, and C). The technical replicate (either A′ or B′) was processed in duplicate from the step of DNase treatment of total RNA onward.

Microarray Hybridization, Scanning, and Quantification of Fluorescence Signal.

After the microarrays were pretreated briefly (90 min) at 55 °C in the prehybridization buffer (prepared as 534 mL of distilled water plus 0.6 g BSA, 6 mL 20% SDS, 60 mL 20xSSC; all chemicals from Sigma-Aldrich), the samples of Cy3-labeled DNA were mixed with 140 µL of hybridization buffer [stock: 9.9 mL of distilled water plus 0.1 mL 20% SDS, 5 mL formamide, 5 mL 20× SSC; for the working buffer, 6 µL of BSA solution (40 mg/mL) was added to 1,194 µL of stock buffer; all chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich], loaded on microarrays, and allowed to hybridize overnight at 42 °C. An automatic Hybridization Station HS4800 Pro (Tecan) was used to perform all steps (washing the station, prehybridization, hybridization, rinsing, and drying) in a precisely standardized way. All microarrays were scanned immediately at the end of the hybridization procedure using the ScanArray GX Microarray Scanner (PerkinElmer) at a resolution of 5 µm (for an example of a scan, see Fig. S4). After all microarray fields and spots were manually aligned perfectly to the template grid, the fluorescence signal was quantified using ScanArray Express v. 4.0.0.0004 software (PerkinElmer).

Fluorescence values were normalized between arrays using Quantile normalization [Limma R package (59)]. All log2 normalized fluorescence (NF) values are summarized in Dataset S1, Excel sheet: NF triplicates. Next, mean log2 NF values were calculated by averaging the spot triplicates (Dataset S1, Excel sheet: NF means for PCA analysis), and this dataset was later used for PCA. Next, mean log2 NF values were recalculated by averaging two technical replicates of one entire microarray (Dataset S1, Excel sheet: NF means for log2 FC analysis), and this dataset was later used for differential expression analysis.

Identification of DE Transcripts and Statistical Analysis.

Based on the mean log2 NF values of three biological replicates, we calculated log2 FCs for treatment comparisons representing consecutive time points using the Limma R package (59). We considered the difference to be significant and the sequences to be DE between treatments when the log2 FC was above 0.55 or below −0.55 (equivalent to an absolute FC of 1.5) and a corrected P value (using Benjamini–Hochberg multiple testing correction) below 0.05. All DE sequences for all treatment comparisons are presented in Dataset S1 [11 Excel sheets representing consecutive time point comparisons from (id1 vs. nd1) to (ct2 vs. ct1) plus two additional comparisons: (id4 vs. id1) and (ct2 vs. ca)].

Next we subjected the mean log2 NF values of four replicates (three biological replicates plus one technical replicate) to PCA (Canoco 5; Biometris, Plant Research International, The Netherlands and Petr Smilauer, University of South Bohemia, Budweis, Czech Republic). Mean centering and variance standardization of the data (subtracting the mean and dividing by the SD, respectively) were performed before PCA analysis. The unconstrained PCA helped reveal clustering effects in global transcriptomic profiles of all treatments compared at a single statistical test considering only a single response variable (i.e. no hierarchy). The 2D PC1 vs. PC2 ordination plots were used to visualize the gradual changes in global transcriptomic patterns graphically as the larvae proceeded through phases of diapause or nondiapause development.

Validation of Microarray Results.

We selected six sequences (for the list, see Table S2) for technical validation of microarray analysis results by real-time qPCR using the CFX96 PCR light cycler (Bio-Rad). The relative abundance of mRNA transcripts of selected target sequences was measured in the aliquots of the same total RNA previously subjected to microarray analysis. The 5-µg aliquots of total RNA were treated with DNase I (Ambion) followed by first-strand cDNA synthesis primed with Oligo(dT)23-anchored primer (Sigma-Aldrich) using SuperScript III (Invitrogen). The cDNA products (20 µL) were diluted 25 times with sterile water. PCR reactions (total volume of 20 µL) contained 5 µL of diluted cDNA template and LA Hot Start Plain Master Mix (Top-Bio) and were primed with a pair of gene-specific oligonucleotide primers (Table S2), each supplied in a final concentration of 400 nM. Cycling parameters were 3 min at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. Analysis of melt curves verified that only one product was amplified in each reaction. In addition, we checked the size of the PCR products for each gene by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel in selected samples. Emission of a fluorescent signal resulting from SYBR Green binding to dsDNA PCR products was detected with increasing PCR cycle number. The threshold cycle (CT) for each sample was automatically calculated using the algorithm built in the CFX96 PCR light cycler software. We used five different sequences (for the list, see Table S2) as endogenous reference standards for relative quantification of the target transcript levels (25, 60). Each sample was run in duplicate (two technical replicates), and the mean of the duplicates was used for calculation. Relative ratios of the target mRNA CT levels to the geometric mean of the CT levels of five reference gene mRNAs were calculated as ΔΔCT according to ref. 61.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bettina Fischer (Cambridge Systems Biology Centre, University of Cambridge) for assistance during the production of custom microarrays. This study was supported by Czech Science Foundation Grant 13-01057S.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1707281114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Lees AD. The physiology and biochemistry of diapause. Annu Rev Entomol. 1956;1:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodek I. Role of environmental factors and endogenous mechanisms in the seasonality of reproduction in insects diapausing as adults. In: Brown VK, Hodek I, editors. Diapause and Life Cycle Strategies in Insects. Dr W Junk Publishers; The Hague: 1983. pp. 9–33. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tauber MJ, Tauber CA, Masaki S. Seasonal Adaptations of Insects. Oxford Univ Press; Oxford, UK: 1986. p. 411. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danks HV. 1987. Insect dormancy: An ecological perspective. Terrestrial Arthropods, Monograph series No. 1 (National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa) p 439.

- 5.Saunders DS. In: Insect Clocks. Steel CGH, Vafopoulou X, Lewis RD, editors. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2002. p. 576. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denlinger DL. Why study diapause? Entomol Res. 2008;38:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forrest JRK. Complex responses of insect phenology to climate change. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 2016;17:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams CN. Physiology of insect diapause; the role of the brain in the production and termination of pupal dormancy in the giant silkworm, Platysamia cecropia. Biol Bull. 1946;90:234–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denlinger DL, Yocum GD, Rinehart JP. Hormonal control of diapause. In: Gilbert LI, editor. Insect Endocrinology. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2012. pp. 430–463. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tauber CA, Tauber MJ. Insect seasonal cycles: Genetics and evolution. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1981;12:281–308. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradshaw WE, Holzapfel CM. Phenotypic evolution and the genetic architecture underlying photoperiodic time measurement. J Insect Physiol. 2001;47:809–820. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emerson KJ, Bradshaw WE, Holzapfel CM. Complications of complexity: Integrating environmental, genetic and hormonal control of insect diapause. Trends Genet. 2009;25:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nylin S. Induction of diapause and seasonal morphs in butterflies and other insects: Knowns, unknowns and the challenge of integration. Physiol Entomol. 2013;38:96–104. doi: 10.1111/phen.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masaki S. Summer diapause. Annu Rev Entomol. 1980;25:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denlinger DL. Dormancy in tropical insects. Annu Rev Entomol. 1986;31:239–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.31.010186.001323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolda H. Insect seasonality. Why? Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1988;19:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacRae TH. Gene expression, metabolic regulation and stress tolerance during diapause. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:2405–2424. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0311-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poelchau MF, Reynolds JA, Elsik CG, Denlinger DL, Armbruster PA. Deep sequencing reveals complex mechanisms of diapause preparation in the invasive mosquito, Aedes albopictus. Proc Royal Soc B-Biol Sci. 2013;280:20130143. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yocum GD, et al. Key molecular processes of the diapause to post-diapause quiescence transition in the alfalfa leaf cutting bee Megachile rotundata identified by comparative transcriptome analysis. Physiol Entomol. 2015;40:103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ragland GJ, Denlinger DL, Hahn DA. Mechanisms of suspended animation are revealed by transcript profiling of diapause in the flesh fly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14909–14914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007075107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansingh A. Physiological classification of dormancies in insects. Can Entomol. 1971;103:983–1009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tauber MJ, Tauber CA. Insect seasonality: Diapause maintenance, termination, and postdiapause development. Annu Rev Entomol. 1976;21:81–107. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kostál V. Eco-physiological phases of insect diapause. J Insect Physiol. 2006;52:113–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koštál V, Mollaei M, Schöttner K. Diapause induction as an interplay between seasonal token stimuli, and modifying and directly limiting factors: Hibernation in Chymomyza costata. Physiol Entomol. 2016a;41:344–357. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poupardin R, et al. Early transcriptional events linked to induction of diapause revealed by RNAseq in larvae of drosophilid fly, Chymomyza costata. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:720. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1907-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koštál V, Shimada K, Hayakawa Y. Induction and development of winter larval diapause in a drosophilid fly, Chymomyza costata. J Insect Physiol. 2000;46:417–428. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1910(99)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kostál V, Zahradnícková H, Šimek P. Hyperprolinemic larvae of the drosophilid fly, Chymomyza costata, survive cryopreservation in liquid nitrogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13041–13046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107060108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koštál V, Korbelová J, Poupardin R, Moos M, Šimek P. Arginine and proline applied as food additives stimulate high freeze tolerance in larvae of Drosophila melanogaster. J Exp Biol. 2016b;219:2358–2367. doi: 10.1242/jeb.142158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Denlinger DL, et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Insect Metamorphosis and Diapause. Industrial Publishing & Consulting Inc; Tokyo: 1995. Diapause-specific gene expression; pp. 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayward SAL, Pavlides SC, Tammariello SP, Rinehart JP, Denlinger DL. Temporal expression patterns of diapause-associated genes in flesh fly pupae from the onset of diapause through post-diapause quiescence. J Insect Physiol. 2005;51:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robich RM, Denlinger DL. Diapause in the mosquito Culex pipiens evokes a metabolic switch from blood feeding to sugar gluttony. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15912–15917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507958102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds JA, Hand SC. Embryonic diapause highlighted by differential expression of mRNAs for ecdysteroidogenesis, transcription and lipid sparing in the cricket Allonemobius socius. J Exp Biol. 2009;212:2075–2084. doi: 10.1242/jeb.027367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Urbanski JM, Aruda A, Armbruster P. A transcriptional element of the diapause program in the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, identified by suppressive subtractive hybridization. J Insect Physiol. 2010;56:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emerson KJ, Bradshaw WE, Holzapfel CM. Microarrays reveal early transcriptional events during the termination of larval diapause in natural populations of the mosquito, Wyeomyia smithii. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kankare M, Salminen T, Laiho A, Vesala L, Hoikkala A. Changes in gene expression linked with adult reproductive diapause in a northern malt fly species: A candidate gene microarray study. BMC Ecol. 2010;10:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-10-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meyers PJ, et al. Divergence of the diapause transcriptome in apple maggot flies: Winter regulation and post-winter transcriptional repression. J Exp Biol. 2016;219:2613–2622. doi: 10.1242/jeb.140566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tatar M, et al. A mutant Drosophila insulin receptor homolog that extends life-span and impairs neuroendocrine function. Science. 2001;292:107–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1057987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams KD, et al. Natural variation in Drosophila melanogaster diapause due to the insulin-regulated PI3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:15911–15915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604592103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sim C, Denlinger DL. Insulin signaling and FOXO regulate the overwintering diapause of the mosquito Culex pipiens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6777–6781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802067105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sim C, Denlinger DL. Insulin signaling and the regulation of insect diapause. Front Physiol. 2013;4:189. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sim C, Kang DS, Kim S, Bai X, Denlinger DL. Identification of FOXO targets that generate diverse features of the diapause phenotype in the mosquito Culex pipiens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:3811–3816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502751112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grönke S, Clarke D-F, Broughton S, Andrews TD, Partridge L. Molecular evolution and functional characterization of Drosophila insulin-like peptides. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000857. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Das R, Dobens LL. Conservation of gene and tissue networks regulating insulin signalling in flies and vertebrates. Biochem Soc Trans. 2015;43:1057–1062. doi: 10.1042/BST20150078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sim C, Denlinger DL. Catalase and superoxide dismutase-2 enhance survival and protect ovaries during overwintering diapause in the mosquito Culex pipiens. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57:628–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Storz P. Forkhead homeobox type O transcription factors in the responses to oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:593–605. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martins R, Lithgow GJ, Link W. Long live FOXO: Unraveling the role of FOXO proteins in aging and longevity. Aging Cell. 2016;15:196–207. doi: 10.1111/acel.12427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hay N. Interplay between FOXO, TOR, and Akt. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1965–1970. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujiwara Y, Denlinger DL. High temperature and hexane break pupal diapause in the flesh fly, Sarcophaga crassipalpis, by activating ERK/MAPK. J Insect Physiol. 2007;53:1276–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rinehart JP, Cikra-Ireland RA, Flannagan RD, Denlinger DL. Expression of ecdysone receptor in unaffected by pupal diapause in the flesh fly, Sarcophaga crassipalpis, while its dimerization partner, USP, is downregulated. J Insect Physiol. 2001;47:915–921. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niimi T, Yamashita O, Yaginuma T. A cold-inducible Bombyx gene encoding a protein similar to mammalian sorbitol dehydrogenase. Yolk nuclei-dependent gene expression in diapause eggs. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:1125–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ti X, et al. Demarcation of diapause development by cold and its relation to time-interval activation of TIME-ATPase in eggs of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Insect Physiol. 2004;50:1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ragland GJ, Egan SP, Feder JL, Berlocher SH, Hahn DA. Developmental trajectories of gene expression reveal candidates for diapause termination: A key life-history transition in the apple maggot fly Rhagoletis pomonella. J Exp Biol. 2011;214:3948–3959. doi: 10.1242/jeb.061085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jope RS, Johnson GVW. The glamour and gloom of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Trends Biochem Sci. 2004;29:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kostál V, Simůnková P, Kobelková A, Shimada K. Cell cycle arrest as a hallmark of insect diapause: Changes in gene transcription during diapause induction in the drosophilid fly, Chymomyza costata. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;39:875–883. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riihimaa AJ, Kimura MT. A mutant strain of Chymomyza costata (Diptera, Drosophilidae) insensitive to diapause-inducing action of photoperiod. Physiol Entomol. 1988;13:441–445. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lakovaara S. Malt as a culture medium for Drosophila species. Drosoph Inf Serv. 1969;44:128. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rouillard JM, Zuker M, Gulari E. OligoArray 2.0: Design of oligonucleotide probes for DNA microarrays using a thermodynamic approach. Nucl Acid Res. 2003;31:3057–3062. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dhami P, et al. Genomic approaches uncover increasing complexities in the regulatory landscape at the human SCL (TAL1) locus. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ritchie ME, et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ponton F, Chapuis MP, Pernice M, Sword GA, Simpson SJ. Evaluation of potential reference genes for reverse transcription-qPCR studies of physiological responses in Drosophila melanogaster. J Insect Physiol. 2011;57:840–850. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Petryk A, et al. Shade is the Drosophila P450 enzyme that mediates the hydroxylation of ecdysone to the steroid insect molting hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13773–13778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336088100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hall BL, Thummel CS. The RXR homolog ultraspiracle is an essential component of the Drosophila ecdysone receptor. Development. 1998;125:4709–4717. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.23.4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hill RJ, Billas IM, Bonneton F, Graham LD, Lawrence MC. Ecdysone receptors: From the Ashburner model to structural biology. Annu Rev Entomol. 2013;58:251–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thummel CS. Molecular mechanisms of developmental timing in C. elegans and Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2001;1:453–465. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Edgar BA. How flies get their size: Genetics meets physiology. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:907–916. doi: 10.1038/nrg1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koyama T, Mendes CC, Mirth CK. Mechanisms regulating nutrition-dependent developmental plasticity through organ-specific effects in insects. Front Physiol. 2013;4:263. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao X, Neufeld TP, Pan D. Drosophila PTEN regulates cell growth and proliferation through PI3K-dependent and -independent pathways. Dev Biol. 2000;221:404–418. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miron M, Sonenberg N. Regulation of translation via TOR signaling: Insights from Drosophila melanogaster. J Nutr. 2001;131:2988S–2993S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.11.2988S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee JH, et al. Sestrin as a feedback inhibitor of TOR that prevents age-related pathologies. Science. 2010;327:1223–1228. doi: 10.1126/science.1182228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gao X, Pan D. TSC1 and TSC2 tumor suppressors antagonize insulin signaling in cell growth. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1383–1392. doi: 10.1101/gad.901101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Garami A, et al. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hietakangas V, Cohen SM. Re-evaluating AKT regulation: Role of TOR complex 2 in tissue growth. Genes Dev. 2007;21:632–637. doi: 10.1101/gad.416307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grewal SS. Insulin/TOR signaling in growth and homeostasis: a view from the fly world. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1006–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Teleman AA. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic regulation by insulin in Drosophila. Biochem J. 2009;425:13–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Riddiford LM. Hormones and Drosophila development. In: Bate M, Martinez AA, editors. The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1993. pp. 899–939. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Doctor JS, Fristrom JW. Macromolecular changes in imaginal discs during postembryonic development. In: Kerkut GA, Gilbert LI, editors. Comprehensive Insect Physiology, Biochemistry and Pharmacology. Pergamon; Oxford, UK: 1985. pp. 201–238. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koyama T, Iwami M, Sakurai S. Ecdysteroid control of cell cycle and cellular commitment in insect wing imaginal discs. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;213:155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zitnan D, Sehnal F, Bryant PJ. Neurons producing specific neuropeptides in the central nervous system of normal and pupariation-delayed Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1993;156:117–135. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Harvie PD, Filippova M, Bryant PJ. Genes expressed in the ring gland, the major endocrine organ of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1998;149:217–231. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Richard DS, et al. Juvenile hormone bisepoxide biosynthesis in vitro by the ring gland of Drosophila melanogaster: A putative juvenile hormone in the higher Diptera. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1421–1425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lee G, Park JH. Hemolymph sugar homeostasis and starvation-induced hyperactivity affected by genetic manipulations of the adipokinetic hormone-encoding gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2004;167:311–323. doi: 10.1534/genetics.167.1.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ikeya T, Galic M, Belawat P, Nairz K, Hafen E. Nutrient-dependent expression of insulin-like peptides from neuroendocrine cells in the CNS contributes to growth regulation in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Colombani J, et al. Antagonistic actions of ecdysone and insulins determine final size in Drosophila. Science. 2005;310:667–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1119432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Layalle S, Arquier N, Léopold P. The TOR pathway couples nutrition and developmental timing in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2008;15:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Colombani J, Andersen DS, Léopold P. Secreted peptide Dilp8 coordinates Drosophila tissue growth with developmental timing. Science. 2012;336:582–585. doi: 10.1126/science.1216689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Garelli A, Gontijo AM, Miguela V, Caparros E, Dominguez M. Imaginal discs secrete insulin-like peptide 8 to mediate plasticity of growth and maturation. Science. 2012;336:579–582. doi: 10.1126/science.1216735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Andersen DS, Colombani J, Léopold P. Coordination of organ growth: Principles and outstanding questions from the world of insects. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bryant PJ. Growth factors controlling imaginal disc growth in Drosophila. Novartis Found Symp. 2001;237:182–194, discussion 194–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]