Abstract

Following burn injury, a key factor for patients susceptible to opportunistic infections is immune suppression. Butyrate levels are important in maintaining a functional immune system and these levels can be altered after injury. The acid sphingomyelinase (Asm) lipid signaling system has been implicated in a T cell actions with some evidence of being influenced by butyrate. Here, we hypothesized that burn-injury changes in butyrate levels would mediate Asm activity and, consequently, T cell homeostasis. We demonstrate that burn injury temporally decreases butyrate levels. We further determined that T cell Asm activity is increased by butyrate and decreased after burn injury. We additionally observed decreased T cell numbers in Asm-deficient, burn-injured, and microbiota-depleted mice. Finally, we demonstrate that butyrate reduced T cell death in an Asm-dependent manner. These data suggest that restoration of butyrate after burn injury may ameliorate the T cell lost observed in burn-injured patients by Asm regulation.

Keywords: Burn injury, T cells, Butyrate, Acid sphingomyelinase, Apoptosis

1. Introduction

Following burn injury, the development of bacterial infections and sepsis is the leading cause of mortality [1, 2]. While a disrupted skin barrier contributes significantly to infectious complications after burn, a major underlying factor is thermal-injury induced immune dysfunction. With improvements in wound care, early burn excision, and antibiotic administration, wound infections have decreased while nosocomial infections have become the primary cause for mortality in burn-injured patients, particularly during the state of immunosuppression [2, 3]. Consequently, there is a need to understand the factors that control burn-related immune dysfunction and susceptibility to nosocomial infections.

Multiple factors contribute to immunosuppression following burn-injury. These include altered frequency of regulatory T cells, increased levels of cytokines, immune cell apoptosis, and alteration in lipid mediators [4–6]. It is unknown whether these mechanisms have an underlying common mediator. Recent data has implicated the gut microbiota in playing a critical role in local (intestinal) [7, 8] and systemic immune homeostasis [9–11]. Intestinal microbiota serves multiple functions, including the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFA), the primary nutrient of the colonocyte [12, 13]. The SCFA butyrate has been shown to promote accumulation of regulatory T cells [14, 15]. The role of butyrate in inflammation and immunity is further supported by a study demonstrating butyrate administration can protect against inflammatory bowel disease [15]. While alterations in the microbiota, and butyrate, can affect the systemic immune response, the reciprocal action occurs as well. Alterations in the immune response can shift the composition of the microbiota. It has previously been shown that loss of T-bet in innate immune cells alters the microbiota [16]. Similarly, loss of NLRP6 inflammasome, specifically in colonic epithelial cells, can increase inflammation and drive shifts in the composition of the microbiota [17]. In both of these instances, the shifts in the microbiota resulted in worsened autoimmune colitis. Taken a step further, a recent clinical study examined the fecal material from patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome, due to infection, trauma, or burn, and demonstrated a loss of anaerobes and reduction in organic acids [18]. Further, burn injury has been shown to induce a dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiome, increase intestinal permeability and increase bacterial translocation [19, 20], suggesting that the gut may be a potential source of bacterial infection. While it is known that trauma and burn injury alter the gut microbiota, it is unknown how these changes affect immune responsiveness. Specifically, it is unknown how changes in intestinal butyrate following burn injury affect the immune response.

In addition to altering intestinal microbiota, trauma and burn injury can alter the acid sphingomyelinase (Asm) lipid signaling system. Sphingolipids are a major component of the cell membrane. Asm is an enzyme that is ubiquitously expressed and converts the cell membrane phospholipid sphingomyelin to ceramide [21, 22]. The Asm/ceramide system plays a role in cell adhesion, migration, and T cell apoptosis [23–29]. Additionally, Asm activity has been shown to be induced by butyrate in a colon cancer cell model [30]. Here, we sought to further explore the link between Asm and butyrate in the microbiota and the potential role in immune suppression.

A function of the gut microbiota is to produce short chain fatty acids (SCFA), the primary nutrient of the colonocyte [13]. Specifically, members from the Firmicute phylum and the Clostridiale family produce butyrate [31], a crucial SCFA for immune system regulation. We previously demonstrated that burn injury significantly reduces the Firmicute phylum, in particular the gnavus and eutactus species, both known butyrate producers [20], particularly on post burn day (PBD) 6. As it is known that the microbiota and Asm system are altered following burn injury, it is unknown how butyrate, may impact Asm activity. Further, it is unknown if alterations in Asm caused by butyrate alter the T cell homeostasis following burn injury. In this study, we hypothesized that potential burn-injury altered butyrate levels would mediate Asm activity and T cell numbers.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Mice

Male CF-1 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) at five weeks of age and allowed to acclimate for one to two weeks prior to conducting experiments. For genetargeted experiments, acid sphingomyelinase (Asm) knock-out homebred mice and their wild-type littermates were utilized as previously described [32, 33]. All mice were housed in standard environmental conditions and fed with a pellet diet and water ad libitum. All murine experiments were conducted between 7 am and 10 am using protocols approved by the Institution Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC number 08-09-19-01) of the University of Cincinnati.

2.2. Scald burn injury

Male CF-1 mice underwent a full-thickness scald injury on their dorsal surface as previously described [34]. Briefly, mice were weighed and subsequently anesthetized with 4.5% inhaled isoflurane in oxygen. Hair was clipped from their dorsal surface and they were placed in a template exposing 28% of their total body surface area. They were immersed in 90.0°C water for 9 s, resulting in a full-thickness scald injury. Following injury, mice received intraperitoneal resuscitation with 1.5 mL sterile saline. The mice were allowed to recover on a 42.0°C heating pad for 3 h following scald injury. Sham treated mice underwent the above procedure, except they were not immersed in water.

2.3. Butyric acid measurements

Mice were subjected to sham or scald injury as described above. On PBD 1–8, stool samples were collected from the cecum and butyric acid levels were analyzed as previously described [35]. Briefly, stool samples were weighed and diluted at a ratio of 1:5 in 25% meta-phosphoric acid. The samples were centrifuged at 16,000g for 15 min at 4.0°C, filtered through 0.45 μm syringe tip filter (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA), and then stored at −80.0°C until ready for analysis. Butyrate concentrations were performed by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using a Rezex ROA-organic acid H+ (8%) 300 × 7.8 mm analytical column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) at 65.0°C. A 0.01 N sulfuric acid mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.7 mL/min was used. A UV detector set at wavelength 210 nm monitored the effluent. Butyric acid levels were compared to standards ranging from 1 to 100 mM. Concentrations were corrected for dilution and fecal weight and expressed as μmol per gram of wet weight feces [35, 36].

2.4. Asm activity

Spleens were harvested from uninjured mice and T cells were separated on an AutoMACS as described by the manufacturer (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). The isolated T cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in vitro with or without 100 μM sodium butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Separately, spleens were harvested from sham or PBD 6 mice and T cells isolated by AutoMACS. All samples were frozen at −80°C until ready for Asm analysis. Asm activity was quantified as previously described [37] in which the release of 14C-phosphorylcholine from [14C]-sphingomyelin was used to determine Asm activity.

2.5. Microbiota reduction via antibiotic treatment

Mice underwent oral gavage with a broad-spectrum antimicrobial cocktail of 200 μL for ten days as described previously [38]. For the first three days, mice were treated with 1 mg/kg amphotericin B (Sigma-Aldrich). Subsequently, on days four through ten, mice were gavaged with an antimicrobial cocktail consisting of 50 mg/kg vancomycin hydrochloride (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL), 100 mg/kg neomycin sulfate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), 100 mg/kg metronidazole (Acros Organics, NJ) and 1 mg/kg amphotericin B. Additionally, 1 g/L of ampicillin (Sandoz Inc., Princeton, NJ) was added to their drinking water. Control mice were gavaged with equal volume of sterile saline.

2.6. Flow cytometry analysis of surface antigens

Analyses of cell surface antigen expression were performed as previously described [39] on harvested spleens. Flow cytometry data acquisition and analysis were performed on an Attune Acoustic Focusing Cytometer using Attune Cytometric Software v2.1. The following antibodies were used: CD4 (Clone: RM4-5, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), CD8 (Clone: 53-6.7, BD Biosciences), CD44 (Clone: IM7, BD Biosciences), and CD62L (Clone: MEL-14, BD Biosciences). Naïve T cells were identified on flow cytometry with CD62LHi/CD44Lo antigen expression.

2.7. T Cell apoptosis determination

For T cell apoptosis measurements, splenocytes were isolated from CF-1 mice and cultured for 24 h. Cells were incubated at 37°C with 0 μM, 0.1 μM, 1 μM, 10 μM, 100 μM, or 1000 μM concentrations of butyrate (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 nM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich). To evaluate phosphatidyl serine exposure, cells were then labeled for Annexin V (BD Pharminogen) as previously described [40]. In a subsequent experiment, splenocytes were harvested from Asm WT or KO mice. These cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C with one of the following treatments: A) (—) butyrate/(—) dexamethasone, B) 100 μM butyrate, C) 1 nM dexamethasone or D) 100 μM butyrate and 1 nM dexamethasone. Again, cells were analyzed for Annexin V labeling by flow cytometry, as described above.

2.8. Statistical analyses

Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s t Test (for two groups) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc analysis (for more than two groups) using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (Graphpad Software, La Jolla, CA). The mean and standard error of the mean were calculated in experiments containing multiple data points. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Cecal butyric acid concentration is reduced following scald injury

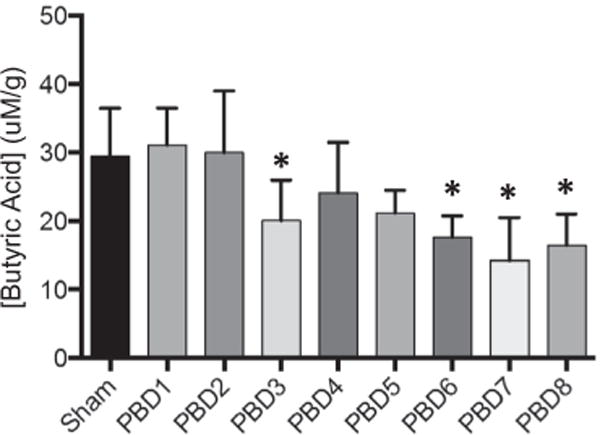

As burn can induce changes butyrate-producing bacteria, we hypothesized that butyrate levels are altered after burn injury. In Fig. 1, we demonstrate there is a significant reduction in cecal butyrate levels on PBD3, and on PBD6 (41.4% compared to sham), which continued on PBD7 and PBD8 (51.6% and 43.9% reduction, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Cecal butyric acid concentration is reduced following scald injury. Mice were weighed and then underwent 28% TBSA scald injury. Mice were sacrificed on PBD 1 through 8 and cecal material was collected for butyric acid analysis. The sample size was 6–7 mice per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison, *p < 0.05 as compared to sham.

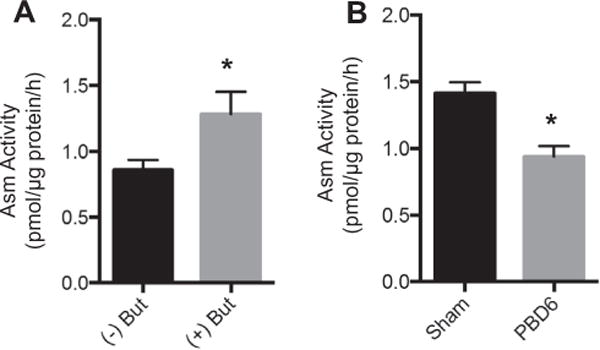

3.2. Altered butyrate levels are associated with changes in acid sphingomyelinase activity

As butyrate levels are reduced following scald injury, we sought to investigate the effect of altered butyrate levels on Asm activity in T cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, exogenously added butyrate increases Asm activity in splenic T cells (Fig. 2A). Additionally, we observed that Asm activity is decreased by 33.5% in splenic T cells isolated from burn-injured mice as compared to sham (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Acid sphingomyelinase (Asm) activity is reduced with the absence of butyrate and after scald injury. (A) Splenic T cell Asm activity following 1 h incubation in vitro with or without 100 μM butyrate was determined. (B) Mice underwent sham or scald injury. On PBD6, splenic T cells were isolated and analyzed for Asm activity. Sample size was 6–9 mice per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s T-test, *p < 0.05 as compared to sham group. Asm — acid sphingomyelinase. But — Butyrate, PBD — post burn day.

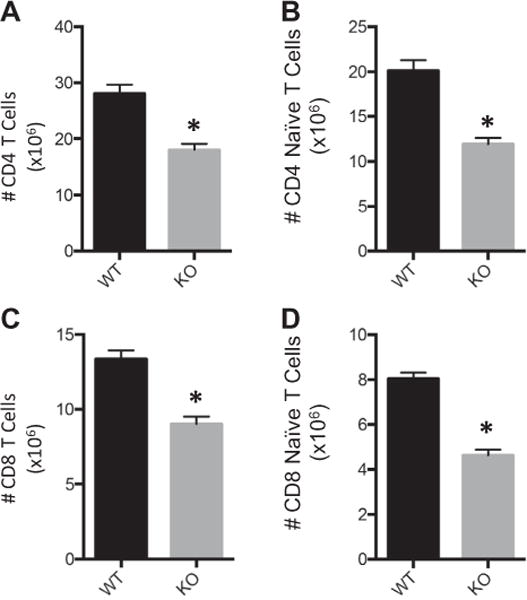

3.3. T Cell populations are reduced in Asm knockout mice

We next sought to elucidate the role of Asm in maintaining T cell populations. We hypothesized that total and naïve T cell populations would be reduced in Asm deficient mice. We observed that Asm KO mice have a significant reduction in total CD4 and CD8 T cell numbers (Fig. 3A and C). Additionally, we observed that Asm KO spleens had a lower proportion of total CD4 and CD8 T cells (17.9 ± 2.8% vs 13.8 ± 1.1%, p = 0.001 and 8.6 ± 1.2 vs 6.9 ± 0.3, p = 0.001, respectively). Further, there is a significant reduction in the number of CD4 and CD8 naïve T cells (Fig. 3B and D). We did not observe significant changes in the proportions of naïve CD4 or CD8 T cells.

Fig. 3.

Reduced T cell populations observed in Asm knockout mice. Splenic T cells were harvested from Asm wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice and the number of (A) Total CD4 T cells, (B) CD4 Naïve T cells, (C) Total CD8 T cells, (D) CD8 Naïve T cells were enumerated and characterized by flow cytometry. Sample size was 20 WT mice and 7 Asm KO mice. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s T-test, *p < 0.05 as compared to WT group.

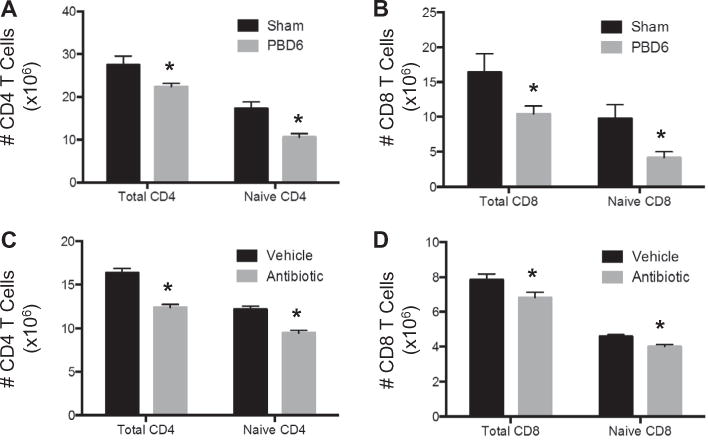

3.4. T Cell populations are decreased after burn injury or antibiotic treatment

To determine the impact of burn-injury on T cell numbers, splenic T cell numbers were determined on PBD6. Here, we demonstrate decreased total and naïve CD4 and CD8 splenic T cells in burn-injured mice as compared to sham (Fig. 4A and B). Of note, the proportion of total and naïve CD4 numbers from injured mice were observed to be decreased (Total: 27.5 ± 8.0% vs 22.4 ± 3.1%, p = 0.021, Naïve: 62.7 ± 9.8 vs 47.3 ± 12.5%, p = 0.0006). Similarly, the proportion of total and naïve CD8 numbers from injured mice were observed to be decreased (Total: 11.2 ± 8.5% vs 4.7 ± 2.9%, p = 0.007, Naïve: 55.1 ± 14.4% vs 36.9 ± 10.8%, p = 0.0005). In addition, we observed decreased total and naïve CD4 and CD8 splenic T cell numbers in antibiotic treated versus vehicle treated mice (Fig. 4C and D). With the antibiotic treatment, there was a 27% reduction in both splenic mass and leukocyte counts, but no significant changes in total or naïve CD4 or CD8 T cell proportions.

Fig. 4.

T cell populations are decreased after either burn injury or antibiotic treatment. On PBD6, splenic T cells from sham or scald injured mice were enumerated and characterized by flow cytometry for (A) total and naïve CD4 T cells and (B) total and naïve CD8 T cells. Mice underwent antibiotic or sterile saline gavage for 10 days. For the first three days, mice were gavaged with amphotericin (1 mg/kg). On days 4–10, mice were gavaged with a cocktail consisting of vancomycin (50 mg/kg), neomycin (100 mg/kg), metronidazole (100 mg/kg) and amphotericin (1 mg/kg). Ampicillin (1 g/L) was added to their drinking water. Splenic T cells from vehicle or antibiotic treated mice were enumerated and characterized by flow cytometry for (C) total and naïve CD4 cells and (D) total and naïve CD8 T cells. Sample size was 15–17 mice per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s T-test, *p < 0.05 as compared to sham. PBD — post burn day.

3.5. Butyrate protects against dexamethasone mediated T-cell apoptosis

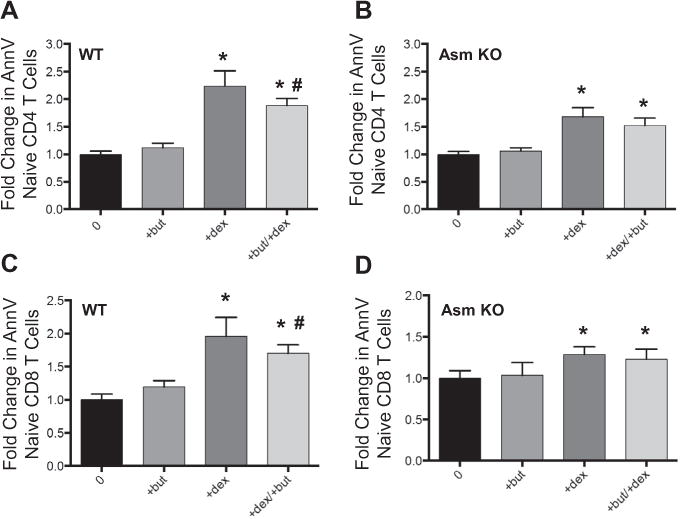

We next investigated the impact of butyrate on T cell apoptosis and hypothesized that increased butyrate would reduce T cell loss. As glucocorticoid induced death is involved in the pathogenesis of thermal injury and is regulated by the intrinsic apoptotic pathway in T cells [41, 42], we used an in vitro model of dexamethasone mediated T cell apoptosis. We demonstrated that supplementation of butyrate reduced dexamethasone induced T cell apoptosis in CD4 and CD8 splenic T cells by approximately 20–30% (Fig. 5A and B). We next sought to investigate the role of Asm in the protective effects of butyrate on T cell loss using Asm deficient and WT mice. When WT mice are treated with 1nM dexamethasone, there is a 2.2-fold increase in the loss of naïve CD4 T cells. Supplementation with 100 μM of butyrate in naïve CD4 T cells of ASM WT mice produced a significant reduction in corticosteroid induced T cell loss (Fig. 6A). Similarly, when Asm KO mice are treated with dexamethasone, there is a 1.6-fold increase in T cell loss. However, when butyrate is added, there is not a significant reduction in corticosteroid induced cell death (Fig. 6B). A significant reduction in cell death with butyrate supplementation was also observed in naïve CD8 T cells isolated from Asm WT mice, but not in Asm KO mice (Fig. 6C and D).

Fig. 5.

Butryate protects against dexamethasone mediated T cell death. Splenic T cells were isolated from CF-1 mice and cultured for 24 h with 1 nM dexamethasone and the indicated concentrations of butyrate. The percentage of Annexin V labeling was determined by flow cytometry for (A) naïve CD4 T cells and (B) naïve CD8 T cells. Sample size was 4 mice per group. The percent annexin V labeling for control, untouched splenocytes ranged from 20 to 30%. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison, *p < 0.05 as compared to sham. AnnV — Annexin V.

Fig. 6.

Butyrate protects against T cell loss in an Asm dependent manner. Splenic T cells were isolated from acid sphingomyelinase (Asm) WT or KO mice. Cells were incubated with either ±100 μM butyrate and ±1 nM dexamethasone. Cells were enumerated and characterized by flow cytometry for (A) Asm WT Naïve CD4 T cells, (B) Asm KO Naïve CD4 T cells, (C) Asm WT Naïve CD8 T cells and (D) Asm KO Naïve CD8 T cells. Sample size was 8 mice per group. Data were normalized to sham values and expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were made using ANOVA with Tukey post-hoc comparison, *p < 0.05 as compared to sham, #p < 0.05 as compared to dexamethasone group.

4. Discussion

In this study, we tested the hypothesis that defects in the microbiota following burn injury would affect the systemic immune response in an Asm-butyrate dependent manner. The intestinal microbiota is involved in local and systemic immune responses, promoting optimal immune function [7–11, 43–45]. Alterations in the microbiota can lead to pathologic disease states such as Clostridium difficile colitis or inflammatory bowel disease [46]. Additionally, use of antibiotics in the neonatal period can alter the intestinal microbiota and has been associated with increased expression of asthma and autoimmune diseases [47, 48]. Earley et al. demonstrate burn injury induces a dramatic dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiome in humans and mice and suggest that potential mechanisms for the shifts in bacterial communities is increased intestinal inflammation and reduction in antimicrobial peptides [19]. Similarly, Kuethe et al., demonstrate alterations in intestinal microbiota and colonic permeability [20]. Specifically, significant reductions were observed in the butyrate producing species, gnavus and eutactus. Consistent with the reductions in butyrate-producing bacteria following [20], we demonstrate that colonic butyrate levels are significantly reduced after burn injury.

We next sought to investigate the effects of the changes in the intestinal microbiota and cecal butyrate have on systemic immunity. It is known that T cell loss and apoptosis are associated with systemic immunosuppression [4, 5]. Here we observe reductions in T cell numbers following burn injury and with antibiotic-induced reduction in the gut microbiota. This is consistent with previous work that alterations in the gut microbiota can dramatically alter systemic immune response. Previous research has shown that mice colonized with segmented filamentous bacterium (SFB) have dramatically increased levels of endogenous CD4+ T cells capable of secreting IL-17 [7, 8]. Additionally, microbiota play a critical role in the accumulation of T regulatory cells in the colonic lamina propria [49, 50], which play a critical role in intestinal and systemic immune homeostasis. One intriguing mechanism for how shifts in the microbiota can affect immune responses is the observation that certain strains of gut bacteria produce butyrate and transfer of butyrate producing bacteria promotes accumulation of regulatory T cells [14, 15]. These data demonstrate the relevance of the gut microbiota to human immunity and that manipulation of the microbiota, and subsequently butyrate, can have a profound effect on the inflammatory response.

Additionally, we demonstrate that following burn injury and in the absence of butyrate, Asm activity is reduced in T cells. Importantly, we show that using transgenic ASM KO mice, that reduction in Asm activity is associated with reduced T cell numbers. This data is consistent with previous reports that have shown the acid sphingomyelinase/ceramide lipid signaling system to play a role in T cell apoptosis [24–29]. Previously, butyrate has been shown to play a role in the homeostasis of the immune system [14, 15]. It has been shown that butyrate modulates the immune response by increasing T cell antibody production in splenocytes [30]. Our data further support the connection between butyrate, Asm and systemic immunity. In an in vitro assay we demonstrate that increased butyrate levels are associated with increased Asm activity. Consequently, we sought to investigate the role of Asm in the protective effects of butyrate on T cell loss. Using transgenic mice, we saw that addition of butyrate was able to protect against T cell loss in Asm WT, but not Asm KO mice. In summary, our data demonstrate that burn injury drives a loss of butyrate-producing gut bacteria, promoting a dysfunctional systemic immunity. Therefore, we conclude that butyrate protects against total and naive T cell loss in an Asm dependent manner. Altogether, the data suggest that restoration of the intestinal microbiota may ameliorate the susceptibility to infection observed in burn-injured patients. Further, we postulate that restoration of butyrate would increase Asm activity, promoting an increase in T cell numbers and thereby protect against the immunosuppression observed after burn injury.

A limitation of this study is the lack of data delivering in vivo butyrate as a direct gain of function study. Future studies will be aimed at increasing systemic butyrate to ameliorate the immuno-suppressive changes caused by alterations to the microbiota after burn-injury. Innovative research will be necessary as previous research has either been inconclusive or does not demonstrate systemic increases in butyrate. A recent clinical study demonstrated that butyrate enemas do not enhance systemic levels; rather they are increased in the portal system and cleared hepatically [51]. Luceri et al. were unable to demonstrate increases in butyrate in rectal or colonic biopsies following administration of high concentration of butyrate enemas and suggest it is rapidly used by colonic epithelium [52]. Similarly, Guillemot et al. describe the reduction in SCFA associated with diversion colitis but were unable to demonstrate effective increases in butyrate via SCFA irrigations [53]. Further investigation is necessary to determine the optimal mechanism of butyrate administration to restore the microbiota after pathologic injury. The goal of the present study was to determine changes in butyrate after injury, how this may mediate Asm levels, and how butyrate and Asm influence naïve T cell homeostasis. A limitation to this study is that Asm-deficient mice have significant changes in the T cell compartment already at baseline. Thus, a more appropriate transgenic mouse to test how Asm influences T cell homeostasis after injury would be one with a T cell specific Asm deficiency. These mice are under development, but will require significant time in order to generate sufficient numbers.

Susceptibility to nosocomial infections remains a persistent clinical problem in burn-injured patients with significant mortality [1, 2]. This current study provides an unexplored link between burn injury induced changes to butyrate and T cell homeostasis. This is of importance as it has been demonstrated that T cells are critical in bacterial clearance and survival during sepsis and infections. A recent clinical study demonstrated that decreased naive T cell numbers is associated with increased mortality and susceptibility to nosocomial infections [54]. Thus, future investigations upon increasing gut butyrate and/or Asm activity may lead to increased T cell numbers after injury and reduced susceptibility to opportunistic infections.

5. Conclusions

In summary, burn injury drives a reduction of butyrate levels in the gut. This loss likely contributes to decreased T cell numbers, potentially mediated through an Asm-dependent manner. These data may have broad implications beyond trauma and burn injury as multiple diseases including autoimmune, asthmatic and allergic response can alter the gut microbiota [55, 56]. This may prompt further investigations in the gut butyrate levels and its role in pathologic versus protective immune responses.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Shriners Hospitals for Children #85310-CIN-14 (CCC). The project described was supported by Award Number T32 GM08478 (TCR) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Coban YK. Infection control in severely burned patients. World J Critic Care Med. 2012;1:94–101. doi: 10.5492/wjccm.v1.i4.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pruitt BA, Jr, McManus AT. The changing epidemiology of infection in burn patients. World J Surg. 1992;16:57–67. doi: 10.1007/BF02067116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.S. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance. National nosocomial infections surveillance (NNIS) system report, data summary from, through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 1992;32(2004):470–485. doi: 10.1016/S0196655304005425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hotchkiss RS, Tinsley KW, Swanson PE, Schmieg RE, Jr, Hui JJ, Chang KC, Osborne DF, Freeman BD, Cobb JP, Buchman TG, Karl IE. Sepsis-induced apoptosis causes progressive profound depletion of B and CD4+ T lymphocytes in humans. J Immunol. 2001;166:6952–6963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotchkiss RS, Chang KC, Grayson MH, Tinsley KW, Dunne BS, Davis CG, Osborne DF, Karl IE. Adoptive transfer of apoptotic splenocytes worsens survival, whereas adoptive transfer of necrotic splenocytes improves survival in sepsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6724–6729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031788100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fullerton JN, O’Brien AJ, Gilroy DW. Lipid mediators in immune dysfunction after severe inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2014;35:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Rakotobe S, Lecuyer E, Mulder I, Lan A, Bridonneau C, Rochet V, Pisi A, De Paepe M, Brandi G, Eberl G, Snel J, Kelly D, Cerf-Bensussan N. The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity. 2009;31:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivanov, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, Tanoue T, Imaoka A, Itoh K, Takeda K, Umesaki Y, Honda K, Littman DR. induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichinohe T, Pang IK, Kumamoto Y, Peaper DR, Ho JH, Murray TS, Iwasaki A. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:5354–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lathrop SK, Bloom SM, Rao SM, Nutsch K, Lio CW, Santacruz N, Peterson DA, Stappenbeck TS, Hsieh CS. Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature. 2011;478:250–254. doi: 10.1038/nature10434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu HJ, Ivanov, Darce J, Hattori K, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Littman DR, Benoist C, Mathis D. Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity. 2010;32:815–827. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cummings JH, Macfarlane GT. Colonic microflora: nutrition and health. Nutrition. 1997;13:476–478. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cummings JH, Macfarlane GT. Role of intestinal bacteria in nutrient metabolism. J Parent Enteral Nutr. 1997;21:357–365. doi: 10.1177/0148607197021006357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, Liu H, Cross JR, Pfeffer K, Coffer PJ, Rudensky AY. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504:451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, Takahashi M, Fukuda NN, Murakami S, Miyauchi E, Hino S, Atarashi K, Onawa S, Fujimura Y, Lockett T, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Tomita M, Hori S, Ohara O, Morita T, Koseki H, Kikuchi J, Honda K, Hase K, Ohno H. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrett WS, Lord GM, Punit S, Lugo-Villarino G, Mazmanian SK, Ito S, Glickman JN, Glimcher LH. Communicable ulcerative colitis induced by T-bet deficiency in the innate immune system. Cell. 2007;131:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elinav E, Strowig T, Kau AL, Henao-Mejia J, Thaiss CA, Booth CJ, Peaper DR, Bertin J, Eisenbarth SC, Gordon JI, Flavell RA. NLRP6 inflammasome regulates colonic microbial ecology and risk for colitis. Cell. 2011;145:745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamada T, Shimizu K, Ogura H, Asahara T, Nomoto K, Yamakawa K, Hamasaki T, Nakahori Y, Ohnishi M, Kuwagata Y, Shimazu T. Rapid and sustained long-term decrease of fecal short-chain fatty acids in critically Ill patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Parent Enteral Nutr. 2015;39:569–577. doi: 10.1177/0148607114529596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Earley ZM, Akhtar S, Green SJ, Naqib A, Khan O, Cannon AR, Hammer AM, Morris NL, Li X, Eberhardt JM, Gamelli RL, Kennedy RH, Choudhry MA. Burn injury alters the intestinal microbiome and increases gut permeability and bacterial translocation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuethe JW, Armocida SM, Midura EF, Rice TC, Hildeman DA, Healy DP, Caldwell CC. Fecal microbiota transplant restores mucosal integrity in a murine model of burn injury. Shock. 2016;45:647–652. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulbins E, Kolesnick R. Raft ceramide in molecular medicine. Oncogene. 2003;22:7070–7077. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grassme H, Jekle A, Riehle A, Schwarz H, Berger J, Sandhoff K, Kolesnick R, Gulbins E. CD95 signaling via ceramide-rich membrane rafts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:20589–20596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Ruiz C, Colell A, Mari M, Morales A, Calvo M, Enrich C, Fernandez-Checa JC. Defective TNF-alpha-mediated hepatocellular apoptosis and liver damage in acidic sphingomyelinase knockout mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:197–208. doi: 10.1172/JCI16010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin T, Genestier L, Pinkoski MJ, Castro A, Nicholas S, Mogil R, Paris F, Fuks Z, Schuchman EH, Kolesnick RN, Green DR. Role of acidic sphingomyelinase in Fas/CD95-mediated cell death. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8657–8663. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rivera IG, Ordonez M, Presa N, Gomez-Larrauri A, Simon J, Trueba M, Gomez-Munoz A. Sphingomyelinase D/ceramide 1-phosphate in cell survival and inflammation. Toxins. 2015;7:1457–1466. doi: 10.3390/toxins7051457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samuel GH, Lenna S, Bujor AM, Lafyatis R, Trojanowska M. Acid sphingomyelinase deficiency contributes to resistance of scleroderma fibroblasts to Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;67:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeidan YH, Hannun YA. The acid sphingomyelinase/ceramide pathway: biomedical significance and mechanisms of regulation. Curr Mol Med. 2010;10:454–466. doi: 10.2174/156652410791608225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tischner D, Theiss J, Karabinskaya A, van den Brandt J, Reichardt SD, Karow U, Herold MJ, Luhder F, Utermohlen O, Reichardt HM. Acid sphingomyelinase is required for protection of effector memory T cells against glucocorticoid-induced cell death. J Immunol. 2011;187:4509–4516. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gomez-Munoz A, Gangoiti P, Arana L, Ouro A, Rivera IG, Ordonez M, Trueba M. New insights on the role of ceramide 1-phosphate in inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013. 1831:1060–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu J, Cheng Y, Jonsson BA, Nilsson A, Duan RD. Acid sphingomyelinase is induced by butyrate but does not initiate the anticancer effect of butyrate in HT29 and HepG2 cells. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1944–1952. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500118-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frankel WL, Zhang W, Singh A, Klurfeld DM, Don S, Sakata T, Modlin I, Rombeau JL. Mediation of the trophic effects of short-chain fatty acids on the rat jejunum and colon. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:375–380. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horinouchi K, Erlich S, Perl DP, Ferlinz K, Bisgaier CL, Sandhoff K, Desnick RJ, Stewart CL, Schuchman EH. Acid sphingomyelinase deficient mice: a model of types A and B Niemann-Pick disease. Nat Genet. 1995;10:288–293. doi: 10.1038/ng0795-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirschnek S, Paris F, Weller M, Grassme H, Ferlinz K, Riehle A, Fuks Z, Kolesnick R, Gulbins E. CD95-mediated apoptosis in vivo involves acid sphingomyelinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27316–27323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002957200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tschop J, Martignoni A, Reid MD, Adediran SG, Gardner J, Noel GJ, Ogle CK, Neely AN, Caldwell CC. Differential immunological phenotypes are exhibited after scald and flame burns. Shock. 2009;31:157–163. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31817fbf4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huda-Faujan N, Abdulamir AS, Fatimah AB, Anas OM, Shuhaimi M, Yazid AM, Loong YY. The impact of the level of the intestinal short chain fatty acids in inflammatory bowel disease patients versus healthy subjects. Open Biochem J. 2010;4:53–58. doi: 10.2174/1874091X01004010053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES, Yadava K, Sichelstiel AK, Sprenger N, NgomBru C, Blanchard C, Junt T, Nicod LP, Harris NL, Marsland BJ. Gut microbiota metabolism of dietary fiber influences allergic airway disease and hematopoiesis. Nat Med. 2014;20:159–166. doi: 10.1038/nm.3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ziobro R, Henry B, Edwards MJ, Lentsch AB, Gulbins E. Ceramide mediates lung fibrosis in cystic fibrosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;434:705–709. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Croswell A, Amir E, Teggatz P, Barman M, Salzman NH. Prolonged impact of antibiotics on intestinal microbial ecology and susceptibility to enteric Salmonella infection. Infect Immun. 2009;77:2741–2753. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00006-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caldwell CC, Kojima H, Lukashev D, Armstrong J, Farber M, Apasov SG, Sitkovsky MV. Differential effects of physiologically relevant hypoxic conditions on T lymphocyte development and effector functions. J Immunol. 2001;167:6140–6149. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kasten KR, Tschop J, Goetzman HS, England LG, Dattilo JR, Cave CM, Seitz AP, Hildeman DA, Caldwell CC. T-cell activation differentially mediates the host response to sepsis. Shock. 2010;34:377–383. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181dc0845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erlacher M, Michalak EM, Kelly PN, Labi V, Niederegger H, Coultas L, Adams JM, Strasser A, Villunger A. BH3-only proteins Puma and Bim are rate-limiting for gamma-radiation- and glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of lymphoid cells in vivo. Blood. 2005;106:4131–4138. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jing D, Bhadri VA, Beck D, Thoms JA, Yakob NA, Wong JW, Knezevic K, Pimanda JE, Lock RB. Opposing regulation of BIM and BCL2 controls glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Blood. 2015;125:273–283. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-576470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kau AL, Ahern PP, Griffin NW, Goodman AL, Gordon JI. Human nutrition, the gut microbiome and the immune system. Nature. 2011;474:327–336. doi: 10.1038/nature10213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hill DA, Artis D. Intestinal bacteria and the regulation of immune cell homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:623–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO. A dominant, coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:19256–19261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812681106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohkusa T, Koido S. Intestinal microbiota and ulcerative colitis. J Infect Chemother. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2015.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Renz H, Brandtzaeg P, Hornef M. The impact of perinatal immune development on mucosal homeostasis and chronic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:9–23. doi: 10.1038/nri3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walker WA. Initial intestinal colonization in the human infant and immune homeostasis. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;63(Suppl. 2):8–15. doi: 10.1159/000354907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, Suda W, Nagano Y, Nishikawa H, Fukuda S, Saito T, Narushima S, Hase K, Kim S, Fritz JV, Wilmes P, Ueha S, Matsushima K, Ohno H, Olle B, Sakaguchi S, Taniguchi T, Morita H, Hattori M, Honda K. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, Taniguchi T, Takeda K, Hori S, Ivanov, Umesaki Y, Itoh K, Honda K. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Beek CM, Bloemen JG, van den Broek MA, Lenaerts K, Venema K, Buurman WA, Dejong CH. Hepatic uptake of rectally administered butyrate prevents an increase in systemic butyrate concentrations in humans. J Nutr. 2015;145:2019–2024. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.211193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Luceri C, Femia AP, Fazi M, Di Martino C, Zolfanelli F, Dolara P, Tonelli F. Effect of butyrate enemas on gene expression profiles and endoscopic/histopathological scores of diverted colorectal mucosa: a randomized trial. Digest Liver Dis. 2016;48:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guillemot F, Colombel JF, Neut C, Verplanck N, Lecomte M, Romond C, Paris JC, Cortot A. Treatment of diversion colitis by short-chain fatty acids. Prospective and double-blind study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:861–864. doi: 10.1007/BF02049697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Venet F, Filipe-Santos O, Lepape A, Malcus C, Poitevin-Later F, Grives A, Plantier N, Pasqual N, Monneret G. Decreased T-cell repertoire diversity in sepsis: a preliminary study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:111–119. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182657948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erb KJ. Can helminths or helminth-derived products be used in humans to prevent or treat allergic diseases? Trends Immunol. 2009;30:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zaccone P, Burton OT, Cooke A. Interplay of parasite-driven immune responses and autoimmunity. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]