Abstract

Individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) associated with biomass smoke inhalation tend to be women born in rural areas with lifelong exposure to open fires while cooking, but can also include persons with prenatal and childhood exposure. Compared with individuals with COPD due to tobacco smoking, individuals exposed to biomass smoke uncommonly have severe airflow obstruction, low diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) or emphysema in high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) but cough, phlegm and airway thickening and air trapping are very common. Autopsies of patients with COPD from biomass smoke exposure show increased pulmonary artery small vessel intimal thickening which may explain pulmonary hypertension, in addition to emphysema and airway disease. Research on similarities and differences in lung damage produced by exposure to biomass fuel smoke while cooking vs. smoking tobacco may provide new insights on COPD. As a public health problem, COPD caused by inhalation of smoke from burning solid fuel is as relevant as COPD caused by smoking tobacco but mainly affects women and children from disadvantaged areas and countries and requires an organized effort for its control. Improved vented biomass stoves are currently the most feasible intervention, but even more efficient stoves are necessary to reduce the biomass smoke exposure and reduce incidence of COPD among this population.

Keywords: copd, indoor pollution, biomass, tobacco smoking, improved biomass stove

Introduction

Nearly one-half of the world’s population continues to be exposed to biomass smoke, during cooking or heating with solid fuels such as dung, wood, agricultural residues and coal.1,2 This exposure is most prevalent in less developed countries and rural areas, with indoor levels of particulate matter often reaching levels several times higher than accepted, safe air pollution standards. Biomass smoke has a variety of pollutants1,3-5 resembling those found in tobacco smoke. Tobacco smoke can be considered to be an addictive form of biomass smoke with both forms of smoke including carcinogens. Exposure to poverty-related biomass smoke6 has been associated with a variety of health effects.7-12 In 2010, 3.2 million deaths, and 111 million disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) were attributed to solid fuel use worldwide.13 Because the exposure is principally domestic, it predominantly affects women and infants, but may also affect men particularly when biomass is used for household heating. The use of biomass fuel can be attributed to a population’s geographic isolation and poor availability of cleaner fuels creating a low position on the energy or fuel ladder.4 This position can improve with economic development, reducing the use of biomass fuel and increasing the use of cleaner fuels such as liquid petroleum gas or electricity. An alternative or complementary model of energy use is the multiple fuel model in which a community simultaneously employs fuels high and low on the energy ladder. This may occur within the same family.14 For example, in Mexico, homes with available gas stoves may still use open fires once or twice a week to cook tortillas or special dishes.

Among the adverse health effects described, COPD and chronic bronchitis are most prevalent7,8.10,15,16, ; comprising the current third leading cause of global mortality and responsible for 2.9 million deaths in 2010.17 COPD also ranks fifth among the main causes of years lived with disability18 and ninth in global causes of DALY´s.19

In the 2010 Global Burden of Disease study, 1.1 million COPD-related deaths were attributed to tobacco smoking, and 850,000 to indoor pollution, but in women slightly more deaths were attributed to indoor pollution than to smoking (445,000 vs. 417,000 deaths).20 It is of interest that estimates for smoking-related deaths due to COPD are rising, whereas those related to indoor pollution are decreasing.

In a recent meta-analysis, risk of exposure to biomass smoke for COPD in women attained an odds ratio of between 2 and 37-10 with less evidence of an effect in men, as expected, because exposure is related to traditionally female-dominated domestic tasks. Use of cleaner fuels or improved biomass stoves for cooking and heating reduces exposure,21 is cost-effective,22 and would likely exert a significant positive impact on health.23 Unfortunately, because of economic conditions and cultural circumstances, the use of solid fuels, which are burnt inefficiently and produce increased amounts of pollutants, continues.24

Comparing COPD caused by smoking and COPD caused by exposure to biomass smoke is very relevant, and not only because of the global magnitude of exposure to biomass smoke. The pathogenesis of the disease and predisposing factors could differ; thus, clinical characteristics, response to treatment and disease prognosis could also differ.25 Analyzing in detail the pathogenesis of COPD and chronic bronchitis associated with biomass smoke may also identify key pathways for the development of COPD from different exposures.

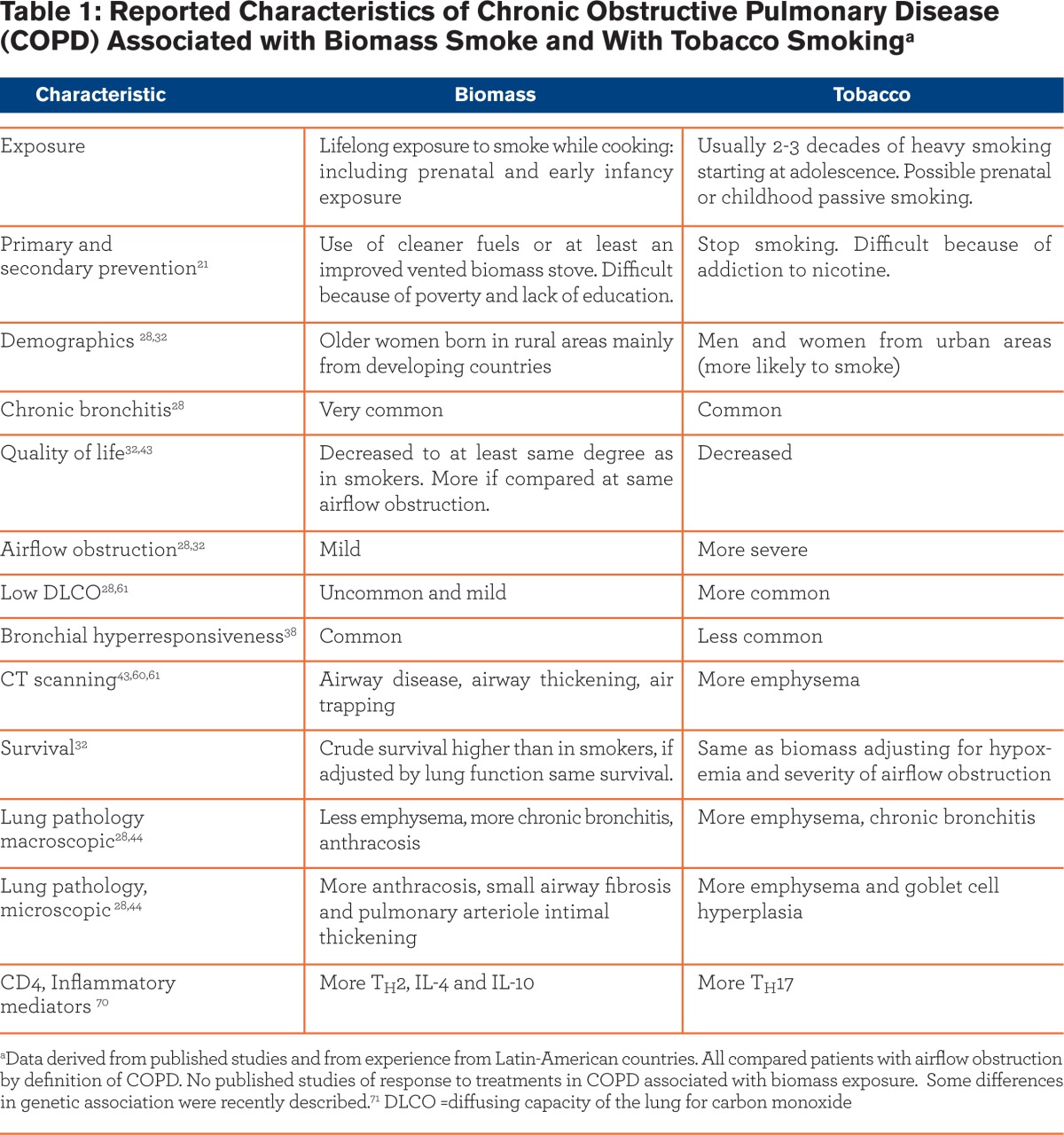

Although information is scarce, over the past few years, a clearer picture of the main characteristics of the persons with biomass smoke-associated COPD (BSCOPD) has emerged, which allows for comparison with many aspects of the better understood individual with COPD caused by tobacco/cigarette smoking (TSCOPD), (See Table 1) forming 2 clearly separable COPD phenotypes.

Some of the differences between individuals with COPD who smoke and those who cook over open fires derive from the cultural and socioeconomic characteristics associated with the use of biomass as fuel and from the specific progression of the smoking epidemic in a given geographic area. Specifically, women in a community may be exposed only to biomass smoke if the majority of households cook with biomass open fires, and smoking in women is still uncommon. Thus, that community’s tobacco smoking epidemic would be at a stage in which the majority of smokers are men.26 Later, a combined exposure of biomass smoke and tobacco smoke is possible if socioeconomic conditions and geographic isolation persist with little ascent on the energy ladder (towards using cleaner fuels), while the tobacco smoking epidemic advances further to include women. For example, in Mexico, that combination is observed in women born in rural areas who migrate to cities, where tobacco smoking by women has increased.

Exposure to biomass fuel creates clinical characteristics in individuals with COPD or chronic bronchitis that may be somewhat different from the typical characteristics found in individual’s with COPD who have inhaled tobacco smoke. It is important to identify both of these. Interactions between exposures are complex, because exposure to biomass smoke increases the risk of airflow obstruction in smokers.27 Combined exposures are rising, as the smoking epidemic reaches women in developing countries.

General Description of the Patients with BSCOPD

A detailed description of the clinical characteristics of women with BSCOPD was recently published.28

Due to the circumstances of exposure, patients with BSCOPD or chronic bronchitis are commonly women born in rural areas who have a lifetime exposure to biomass smoke while cooking. Their exposure includes prenatal and childhood exposure,29 potentially causing an adverse impact on lung development and recurring respiratory infections during infancy,30 which may increase the risk of airway injury and disease later in life. As adults, these women may have migrated to urban areas, or even to a different country.31 Although customs for cooking vary from country to country and within different areas of the same country, kitchens in developing countries tend to be similar with poor ventilation, especially in cold areas, stoves comprised of unvented, open fires, and walls smudged with stove smoke. The kitchen is often the room in the house where everyone sleeps often creating a prolonged exposure, as open fires may additionally be used for household heating. The type of biomass burned tends to change over time. As forests near the village recede, the quality of the biomass decreases, causing a descent on the energy ladder to crop residues, and later dung or garbage. As these biomass are burned, pollution and health risks increase. Gathering and carrying the biomass is also the women´s responsibility, which progressively adds to their burden of domestic activities.

Exposure to biomass smoke leads to chronic irritation and is clearly and consistently associated with respiratory symptoms. Cough, phlegm8,16,28,32 and symptoms of chronic bronchitis are prevalent in women exposed to biomass smoke. Although meta-analyses based on case-control and cross-sectional studies confirm the association between biomass exposure and airflow obstruction,7-10 more evidence exists for an association between biomass smoke inhalation and chronic bronchitis or respiratory symptoms than for spirometric abnormalities.16

Irritation of the eyes and nose mucosa can also be present.33-37 Bacterial colonization of sputum is similar to that described in smokers.28 Dyspnea is common in women arriving at referral hospitals.28,32

Wheezing may be present,28,32 and is consistent with studies finding more methacholine hyperresponsiveness in women with BSCOPD than in smokers.38 The relationship of asthma with exposure to biomass smoke is controversial. Some studies have found an increased risk of asthma in those exposed to biomass smoke,39,40 but results have been inconsistent. Bronchial hyperreactivity (BHR) can be present in any disease producing airflow obstruction, and is not necessarily due to bronchial asthma.41 On physical examination, low-pitched crackles may be heard. Chest roentgenogram may be normal or with increased bronchovascular markings. In a formal comparison, no significant differences between individuals exposed to biomass smoke and smokers were found, with the exception that biomass exposed individuals exhibited more common features of pulmonary hypertension.28 Yet less common in Latin America is an interstitial lung disease pattern, which is likely associated with inhalation of, not only biomass smoke, but also fibrogenic dusts.11,12

In developing countries, the presence of bronchiectasis and tuberculosis (TB) must be ruled out as a cause of chronic respiratory symptoms or airflow obstruction, especially in countries where prevalence for these illnesses is high.42 In one study, cylindrical bronchiectasis was identified via HRCT in 14% of BSCOPD patients . Yet, no bronchiectasis was found in those exposed to tobacco, with patients matched by age and severity of airflow obstruction.43 However, the former may be present in autopsies28,44 and has been identified in one half of patients with moderate or severe COPD.45 It is worth noting that exposure to biomass smoke, as well as exposure to tobacco smoke, may be an important risk factor for developing TB46-48 and lung infections49-52 although evidence for an increase in risk for TB is scarce and controversial.53,54 The presence of TB is also associated with irreversible airflow obstruction.55

Exposure to biomass smoke was described as a risk factor for cor pulmonale in a series of articles by Padmavati, et al,56,57 who were puzzled by the frequency of the disease in women with no cardiovascular risks.57,58 In fact, abnormalities of small pulmonary arterioles with intimal thickening may lead to pulmonary hypertension in individuals exposed to biomass smoke to a greater degree than in smokers.28,44 Patients with BSCOPD are commonly hypoxemic, contributing to pulmonary hypertension32,57 which is mainly mild or moderate. However, some individuals may develop more severe pulmonary hypertension and need to be identified and treated.59 Pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale may b leading causes of complications and death in BSCOPD.

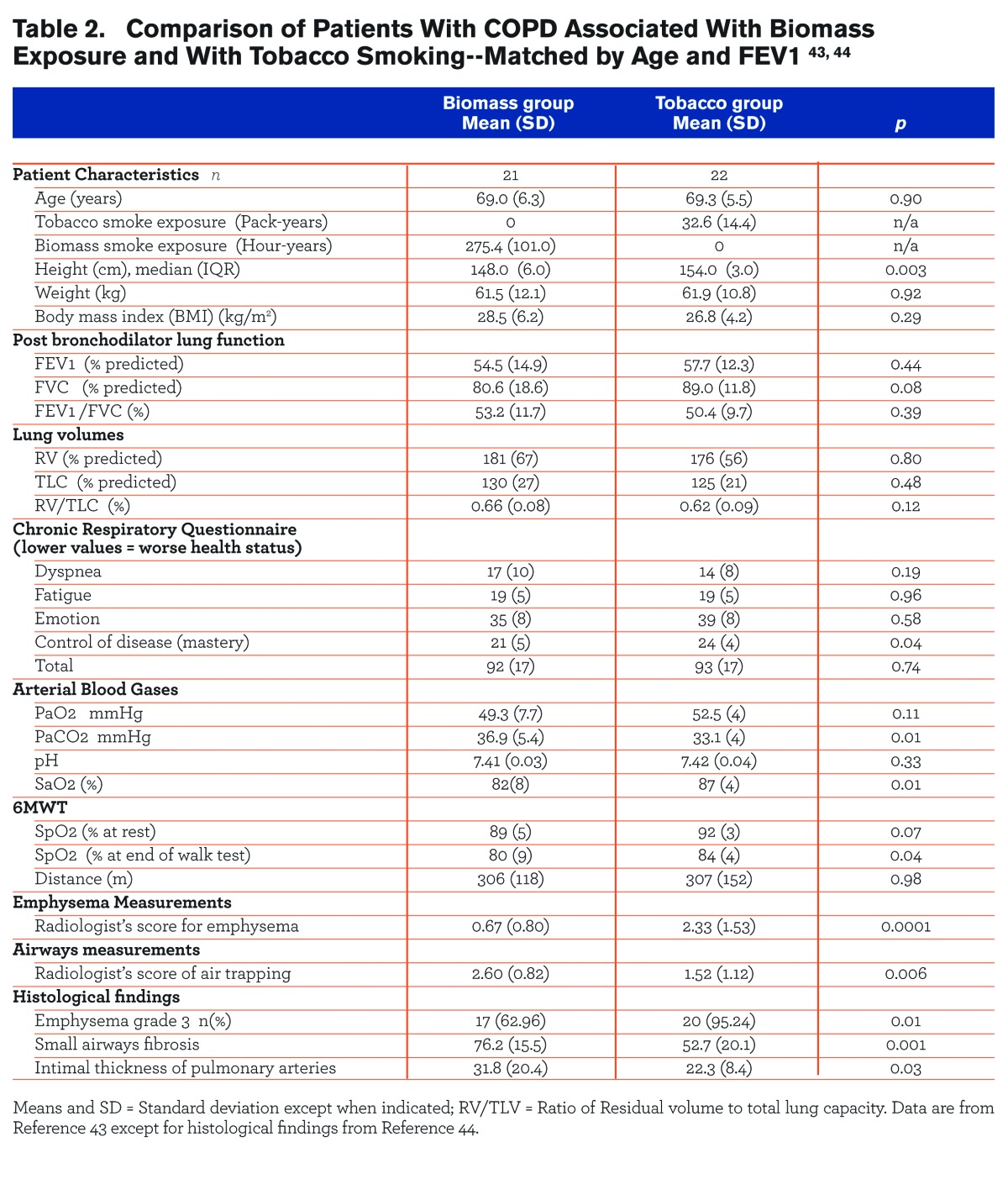

In a comparison of individuals with BSCOPD and individuals with TSCOPD, in which all exhibited airflow obstruction, Ramirez-Venegas et al, found similarities and important differences.32 Airflow obstruction in women exposed to biomass was less severe than in smokers,42 but their quality of life (QOL) was similarly affected.32 In fact, on matching by age and severity of airflow obstruction, women exposed to biomass smoke had a lower QOL and more hypoxemia than smokers.43

In addition, evidence from computed tomography (CT) scanning43,60,61 and DLCO43,61 shows that the clinical presence of emphysema is particularly unusual in women exposed to biomass smoke. However, in lung pathology, emphysema is present in never-smoking women dying of COPD, exposed to biomass,44 but it was milder than in smokers. Other alterations in lung morphology have been described differently in persons exposed to biomass smoke than in persons exposed to tobacco smoke.28,44 Specifically, those exposed to tobacco smoke exhibit more goblet cell hyperplasia and those exposed to biomass smoke exhibit more anthracosis (in airways and in blood vessel walls), small airway fibrosis and intimal thickening in small pulmonary arterioles.44

In Mexico, women exposed to biomass smoke tend to be of short stature and overweight. These traits are reflective of a general high prevalence of obesity, and a link between short stature and indigenous ancestry, both common in deprived communities. The combination of obesity and COPD adds to the burden of COPD, including adding the long list of comorbidities associated with obesity such as hypoxemia, sleep apnea, diabetes, and cardiovascular risks among many others. Treatment for these comorbidities strains the health system to an even greater extent and requires health personnel receive additional education and training on simultaneous comorbid conditions.

The crude survival rate of male smokers with COPD was lower than in women smokers and in those exposed to biomass, but differences disappeared after adjusting for forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1 ) and oxygen saturation (SaO2).32 Specifically, irreversible airflow obstruction in never-smokers with lifelong exposure to biomass creates a similar risk for death as that of the typical smoker with COPD, once adjustments have been carried out for hypoxemia and lung function. QOL is worse in BSCOPD if adjusted for airflow obstruction and age.

A summary of differences and similarities among these different expressions of COPD is depicted in Table 2 and was assembled from the Camp, et al, and Rivera, et al studies. In the Camp et al study at the same age and FEV1, individuals in both groups had similar QOL and dyspnea, but women with BSCOPD were more hypoxemic.

Pathogenesis

Scarce information is available on the possible differences in pathogenesis between damage caused by tobacco smoke and that due to biomass smoke.62-66 Exposure to biomass smoke induces oxidative stress in animal models67,68 and also in individuals with COPD63 to as great a degree as exposure to tobacco smoke creates. Specifically, in comparison with healthy individuals, individuals with BSCOPD have increased levels of malonylaldehide and superoxide dismutase which correlates inversely with FEV1 .63 In addition, both individuals exposed to tobacco and those exposed to biomass showed increased elastolytic activity of macrophages62 and of serum C-reactive protein.69 Recently a group of individuals with TSCOPD were compared with a group of individuals with BSCOPD. Both groups showed an increased proportion of T helper 2 cells (TH2) and T helper 17 cells (TH17) as compared with controls. However, there were some quantitative differences, with the TSCOPD group having a higher blood percentage of TH17 cells (10.3% vs. 3.5%) and the BSCOPD group having more TH2 cells (4.4% vs. 2.5%) and serum concentrations of interleukin 4 (IL-4) and interleukin 10 (IL-10).70 Whether or not these mild or moderate differences in inflammatory responses are relevant and whether they may explain the differences in the clinical and pathological presentations of COPD due to smoking or biomass, or whether the differences depend on susceptibility, or on the type and dose of smoke exposure, has yet to be determined. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, the genetic form of COPD is uncommon in Mexico, and not present in women with wood smoke exposure and chronic bronchitis28 however, some differences between BSCOPD and TSCOPD in the pattern of gene association were recently described.71 In addition, exposure to biomass smoke and its associated gene promoter methylation increase the risk of airflow obstruction in smokers.27 This finding may explain additive risks between exposures to tobacco smoke and to biomass smoke.

Prevention

Prevention must focus on reduction of exposure, by using a cleaner fuel higher on the energy ladder. If costs prohibit this, an improved biomass stove, which is vented to the exterior, is more energy-efficient, and permits the consumption of less wood per the same energy released, creating less pollution, should be used. In a short-term intervention study, a reduction in respiratory symptoms and a decrease in FEV1 decline was observed in women regularly using an improved biomass stove.21 The use of vented coal stoves has decreased the risk of COPD in China.72 The use of improved wood stoves, often implemented in official government programs with lots of publicity and with little or no community participation, has sadly decreased over time and has been abandoned altogether in some communities. Several factors contributed to this including the lack of perception of a health risk with open fires among the targeted population, preference for open fire stoves as a traditional way to cook and the requirement of maintenance of the improved stove at the individual level, which often created follow-up expenses for the household. The reduction of pollutants with improved biomass stoves may be as much as one-half73 however, this may be insufficient for significantly decreasing or eliminating some adverse health effects that depend on the exposure-health risk response.74,75 Without doubt, the use of cleaner fuels or the development of improved biomass stoves, more efficient than current models and with more community acceptance for use over the long term, is required.

Treatment

Recommendations for patients with BSCOPD include receiving treatment based on current COPD guidelines76-78 and avoiding further exposure to biomass smoke if possible. Initial evaluation and follow-up, a prescription of bronchodilators, rehabilitation, oxygen for hypoxemic patients, antibiotics in case of infectious exacerbations, vaccination against influenza and pneumococcus, and other measures are recommended based on current COPD guidelines. However, scientific evidence of treatment effectiveness in BSCOPD is lacking. It is contradictory that these large, dispossessed populations of COPD patients lack relevant clinical trials to prove the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the recommended measures. Conversely, many trials have been conducted with tobacco smokers in developed or middle-income countries, often leading to therapeutic recommendations. Guidelines usually list a variety of interventions and medicines that may have proven effectiveness, but each country, according to its resources, should propose specific guidelines that take into account the cost-effectiveness of medicines and interventions. International agencies could be of assistance with this important activity.

Perspective

Information related to biomass smoke exposure and its health effects is lacking key components. The majority of observational studies lack quantitative measures of exposure. Upon review, no randomized clinical trials describing therapeutic interventions with this group of patients were found. Additionally, to our knowledge, no longitudinal study to observe the health impact of exposure on a cohort of individuals has been published or initiated: epidemiological information to date derives from cross-sectional or case-control studies. Pathogenic studies are also needed. In summary, exposure to biomass smoke predominantly and inequitably affects women, to whom domestic activities are usually assigned, and small children, adding to the burden of poverty. Reducing or eliminating exposure is challenging, but would likely improve health significantly not only through the reduction of lung disease but through the improvement of other quality of life measures, many of which may be unexpected.

Abbreviations

diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, DLCO; high resolution computed tomography, HRCT; disability-adjusted life-years, DALYs; biomass smoke-associated COPD, BSCOPD; tobacco smoke-associated COPD, TSCOPD; bronchial hyperactivity, BHR; quality of life, QOL; computed tomography, CT; T helper cell 2, TH2 ; T helper cell 17, TH17 ; Interleukin-4, IL-4; Interleukin-10, IL-10. Forced expiratory volume at 1 sec FEV1; Forced vital capacity, FVC; Partial presence of oxygen in arterial blood, Pa O2; Partial pressure of oxygen in the blood, PaCO2; arterial oxygen saturation obtained by blood gases, SaO2; arterial oxygen obtained by pulse oximetry, SpO2

References

- 1. Naeher LP,Brauer M,Lipsett M,et al. Woodsmoke health effects: a review. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19(1):67-106. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08958370600985875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bruce N,Rehfuess E,Mehta S,Hutton G,Smith K. Indoor air pollution. In: Jamison D, Breman J, Measham A, etal, eds. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed Washington: Oxford University Press and The World Bank; 2006;793-815. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Balmes JR. When smoke gets in your lungs. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2010;7(2):98-101. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/pats.200907-081RM [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith KR. Biofuels, air pollution, and health. 1 ed. New York: Plenum Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spengler JD,Samet J. A perspective on indoor and outdoor air pollution. In: Samet J, Spengler JD, eds. Indoor Air Pollution: A Health Perspective. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press; 1991:1-29. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Owusu Boadi K,Kuitunen M. Factors affecting the choice of cooking fuel, cooking place and respiratory health in the Accra metropolitan area, Ghana. J Biosoc Sci. 2006;38(3):403-412. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0021932005026635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith K,Mehta S,Maeusezahl-Feuz M. Indoor air pollution from household use of solid fuels: Comparative quantification of health risks. In: Ezzati M, Lopez A, Rodgers A, Murray C, eds. Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004:1435-1493. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurmi OP,Semple S,Simkhada P,Smith WC,Ayres JG. COPD and chronic bronchitis risk of indoor air pollution from solid fuel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010;65(3):221-228. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.124644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Po JY,FitzGerald JM,Carlsten C. Respiratory disease associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2011;66(3):232-239. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.147884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hu G,Zhou Y,Tian J,et al. Risk of COPD from exposure to biomass smoke: a metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;138(1):20-31. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Torres-Duque C,Maldonado D,Perez-Padilla R,Ezzati M,Viegi G. Biomass fuels and respiratory diseases: a review of the evidence. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(5):577-590. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/pats.200707-100RP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bruce N,Perez-Padilla R,Albalak R. Indoor air pollution in developing countries: a major environmental and public health challenge. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(9):1078-1092. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lim SS,Vos T,Flaxman AD,et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224-2260. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Masera OR,Saatkamp BD,DM K. From linear fuel switching to multiple cooking strategies: a critique and alternative to the energy ladder model. World Dev. 2000;28:2083-2103. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00076-0 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perez-Padilla R,Regalado J,Vedal S,et al. Exposure to biomass smoke and chronic airway disease in Mexican women. A case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(3Pt1):701-706. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.154.3.8810608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Regalado J,Perez-Padilla R,Sansores R,et al. The effect of biomass burning on respiratory symptoms and lung function in rural Mexican women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(8):901-905. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200503-479OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lozano R,Naghavi M,Foreman K,et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095-2128. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vos T,Flaxman AD,Naghavi M,et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163-2196. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murray CJ,Vos T,Lozano R,et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197-2223. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation; Global burden of disease study 2010 (GBD 2010) data downloads. 2012;Global Health Data Exchange Web site. http://ghdx.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/global-burden-disease-study-2010-gbd-2010-data-downloads Published March 2013 Accessed October 25, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Romieu I,Riojas-Rodriguez H,Marron-Mares AT,Schilmann A,Perez-Padilla R,Masera O. Improved biomass stove intervention in rural Mexico: impact on the respiratory health of women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(7):649-656. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200810-1556OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hutton G,Rehfuess E,Tediosi F,Weiss S. Evaluation of the Costs and Benefits of Household Energy and Health Interventions at Global and Regional Levels: Summary . Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mortimer K,Gordon SB,Jindal SK,Accinelli RA,Balmes J,Martin WJII. Household air pollution is a major avoidable risk factor for cardiorespiratory disease. Chest. 2012;142(5):1308-1315. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barnes DF OK,Smith KR,van der Plas R . What Makes People Cook With Improved Biomass Stoves? A Comparative International Review of Stove Programs . Washington DC: The World Bank; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diette GB,Accinelli RA,Balmes JR,et al. Obstructive lung disease and exposure to burning biomass fuel in the indoor environment. Glob Heart. 2012;7(3):265-270. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2012.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thun M,Peto R,Boreham J,Lopez AD. Stages of the cigarette epidemic on entering its second century. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):96-101. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sood A,Petersen H,Blanchette CM,et al. Wood smoke exposure and gene promoter methylation are associated with increased risk for COPD in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(9):1098-1104. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201002-0222OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moran-Mendoza O,Perez-Padilla JR,Salazar-Flores M,Vazquez-Alfaro F. Wood smoke-associated lung disease: a clinical, functional, radiological and pathological description. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(9):1092-1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Eisner MD,Anthonisen N,Coultas D,et al. An official American Thoracic Society public policy statement: Novel risk factors and the global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(5):693-718. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200811-1757ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith KR,Samet JM,Romieu I,Bruce N. Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute lower respiratory infections in children. Thorax. 2000;55(6):518-532. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thorax.55.6.518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diaz JV,Koff J,Gotway MB,Nishimura S,Balmes JR. Case report: a case of wood-smoke-related pulmonary disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(5):759-762. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramirez-Venegas A,Sansores RH,Perez-Padilla R,et al. Survival of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease due to biomass smoke and tobacco. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(4):393-397. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200504-568OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Diaz E,Smith-Sivertsen T,Pope D,et al. Eye discomfort, headache and back pain among Mayan Guatemalan women taking part in a randomised stove intervention trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61(1):74-79. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.043133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ellegard A. Tears while cooking: an indicator of indoor air pollution and related health effects in developing countries. Environ Res. 1997;75(1):12-22. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/enrs.1997.3771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Saha A,Kulkarni PK,Shah A,Patel M,Saiyed HN. Ocular morbidity and fuel use: an experience from India. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(1):66-69. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/oem.2004.015636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Alim MA,Sarker MA,Selim S,Karim MR,Yoshida Y,Hamajima N. Respiratory involvements among women exposed to the smoke of traditional biomass fuel and gas fuel in a district of Bangladesh. Environ Health Prev Med. 2013;19(2):126-134. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12199-013-0364-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sukhsohale ND,Narlawar UW,Phatak MS. Indoor air pollution from biomass combustion and its adverse health effects in central India: an exposure-response study. Indian J Community Med. 2013;38(3):162-167. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0970-0218.116353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gonzalez-Garcia M,Torres-Duque CA,Bustos A,Jaramillo C,Maldonado D. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in women with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related to wood smoke. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:367-373. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S30410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mishra V. Effect of indoor air pollution from biomass combustion on prevalence of asthma in the elderly. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111(1):71-78. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.5559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schei MA,Hessen JO,Smith KR,Bruce N,McCracken J,Lopez V. Childhood asthma and indoor woodsmoke from cooking in Guatemala. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2004;14(suppl1):S110-117. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.jea.7500365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Aubier M,Cockcroft DW. Bronchial hyperreactivity other than that seen in asthma [in Spanish]. Rev Fr Mal Respir. 1994;11(2):179-187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Moreira MA,Moraes MR,Silva DG,et al. Comparative study of respiratory symptoms and lung function alterations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease related to the exposure to wood and tobacco smoke [in Spanish]. J Bras Pneumol. 2008;34(9):667-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Camp PG,Ramirez-Venegas A,Sansores RH,et al. COPD phenotypes in biomass smoke- versus tobacco smoke-exposed Mexican females. Eur Respir J. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rivera RM,Cosio MG,Ghezzo H,Salazar M,Perez-Padilla R. Comparison of lung morphology in COPD secondary to cigarette and biomass smoke. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(8):972-977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Martinez-Garcia MA,de la Rosa Carrillo D,Soler-Cataluna JJ,et al. Prognostic value of bronchiectasis in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(8):823-831. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201208-1518OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kolappan C,Subramani R. Association between biomass fuel and pulmonary tuberculosis: a nested case-control study. Thorax. 2009;64(8):705-708. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thx.2008.109405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mishra VK,Retherford RD,Smith KR . Cooking with biomass fuels increases the risk of tuberculosis. Natl Fam Health Surv Bull. 1999 (13):1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Perez-Padilla R,Perez-Guzman C,Baez-Saldana R,Torres-Cruz A. Cooking with biomass stoves and tuberculosis: a case control study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001;5(5):441-447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ezzati M,Kammen DM. Quantifying the effects of exposure to indoor air pollution from biomass combustion on acute respiratory infections in developing countries. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(5):481-488. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.01109481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mishra V,Retherford RD. Cooking smoke increases the risk of acute respiratory infection in children. Natl Fam Health Surv Bull. 1997(8):1-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pandey MR,Boleij JS,Smith KR,Wafula EM. Indoor air pollution in developing countries and acute respiratory infection in children. Lancet. 1989;1(8635):427-429. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90015-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith KR. Indoor air pollution and acute respiratory infections. Indian Pediatr. 2003;40(9):815-819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shetty N,Shemko M,Vaz M,D'Souza G. An epidemiological evaluation of risk factors for tuberculosis in South India: a matched case control study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(1):80-86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Slama K,Chiang CY,Hinderaker SG,Bruce N,Vedal S,Enarson DA. Indoor solid fuel combustion and tuberculosis: is there an association? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis . 2010;14(1):6-14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Menezes AMB,Hallal PC,Perez-Padilla R,et al. Tuberculosis and airflow obstruction: evidence from a multi-centre survey in Latin America. Eur Respir J. 2007;30:1-6. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00083507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Padmavati S,Pathak SN. Chronic Cor Pulmonale in Delhi. Circulation. 1959;20:343-352. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.20.3.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sandoval J,Salas J,Martinez-Guerra ML,et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and cor pulmonale associated with chronic domestic woodsmoke inhalation. Chest. 1993;103(1):12-20. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.103.1.12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Pandey M,Basnyat B,Neupane R. Chronic bronchitis and cor pulmonale in Nepal . Kathmandu: Mrigendra Medical Trust; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Weitzenblum E,Chaouat A. Severe pulmonary hypertension in COPD: is it a distinct disease? Chest . 2005;127(5):1480-1482. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.127.5.1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Moreira MA,Barbosa MA,Queiroz MC,et al. Pulmonary changes on HRCT scans in nonsmoking females with COPD due to wood smoke exposure [in Spanish]. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39(2):155-163. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132013000200006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gonzalez-Garcia M,Maldonado Gomez D,Torres-Duque CA,et al. Tomographic and functional findings in severe COPD: comparison between the wood smoke-related and smoking-related disease[in Spanish]. J Bras Pneumol. 2013;39(2):147-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Montano M,Beccerril C,Ruiz V,Ramos C,Sansores RH,Gonzalez-Avila G. Matrix metalloproteinases activity in COPD associated with wood smoke. Chest. 2004;125(2):466-472. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.2.466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Montano M,Cisneros J,Ramirez-Venegas A,et al. Malondialdehyde and superoxide dismutase correlate with FEV(1) in patients with COPD associated with wood smoke exposure and tobacco smoking. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22(10):868-874. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/08958378.2010.491840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sussan TE,Ingole V,Kim JH,et al. Source of biomass cooking fuel determines pulmonary response to household air pollution. Am J Resp Cell Mol Biol. 2014;50(3):538-548. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1165/rcmb.2013-0201OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mehra D,Geraghty PM,Hardigan AA,Foronjy R. A comparison of the inflammatory and proteolytic effects of dung biomass and cigarette smoke exposure in the lung. PloS One. 2012;7(12):e52889. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lal K,Dutta KK,Vachhrajani KD,Gupta GS,Srivastava AK. Histomorphological changes in lung of rats following exposure to wood smoke. Indian J Exp Biol. 1993;31(9):761-764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Liu PL,Chen YL,Chen YH,Lin SJ,Kou YR. Wood smoke extract induces oxidative stress-mediated caspase-independent apoptosis in human lung endothelial cells: role of AIF and EndoG. Am J Physiol. 2005;289(5):L739-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ramos C,Pedraza-Chaverri J,Becerril C,et al. Oxidative stress and lung injury induced by short-term exposure to wood smoke in guinea pigs. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2013;23(9):711-722. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15376516.2013.843113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Aksu F,Capan N,Aksu K,et al. C-reactive protein levels are raised in stable Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients independent of smoking behavior and biomass exposure. J of Thorac Dis. 2013;5(4):414-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Vargas-Rojas M,Solleiro-Villavicencio H,Ramírez-Venegas A,Velázquez-Uncal M,Quintana R,Sansores-Martínez R. Differences in the polarization of the inflammatory response of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) secondary to smoking and to biomass smoke exposure (abstract). Poster presented at: European Respiratory Society Annual Congress; September 8, 2013; Barcelona, Spain. 2013:Poster595. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pérez-Rubio G,Falfán-Valencia R,Ramírez-Venegas A,et al. Genetic differences in COPD secondary to wood smoke and tobacco smoking (abstract). Poster presented at: European Respiratory Society Annual Congress; September 8, 2013 Barcelona,Spain. 2013:Poster1401. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Chapman RS,He X,Blair AE,Lan Q. Improvement in household stoves and risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Xuanwei, China: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2005;331:1050. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38628.676088.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zuk M,Rojas L,Blanco S,et al. The impact of improved wood-burning stoves on fine particulate matter concentrations in rural Mexican homes. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):224-232. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.jes.7500499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Smith KR,McCracken JP,Weber MW,et al. Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9804):1717-1726. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60921-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Smith KR,Peel JL. Mind the gap. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(12):1643-1645. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1002517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Celli BR,MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932-946. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.04.00014304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Vestbo J,Hurd SS,Agusti AG,et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(4):347-365. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Sansores R,Ramirez-Venegas A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [in Spanish]. Neumol Cir Torax. 2012;71(S1):1-89. [Google Scholar]