Abstract

Background: Desmosine (DES) and isodesmosine (IDES) have been widely discussed as potential biomarkers of COPD. However, their clinical utility and validity remains unproven.

Aim: This study aims to progress DES/IDES evaluation as a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) biomarker by investigating its urinary excretion in a large sample cohort with respect to a) which factors influence DES/IDES levels in a population of healthy control individuals and COPD individuals; b) whether DES/IDES levels enable the differentiation between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals; c) whether DES/IDES can be used to differentiate between fast and slow decliners in lung function.

Methods: Urinary DES and IDES were quantified in 365 individuals (147 healthy control individuals and 218 COPD individuals) from the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Indentify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) study (NCT00292552) by employing a validated liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method.

Results: Age, gender, body mass index (BMI) and smoking have a significant (p<0.05) influence on DES/IDES urinary excretion and need to be corrected for when investigating DES/IDES as a disease biomarker. Urinary DES/IDES allowed a statistically relevant differentiation (p<0.05) between stable COPD individuals and healthy control individuals, however, assay sensitivity and specificity were low (62% and 73%, respectively). Furthermore, urinary DES/IDES does not allow the differentiation of fast and slow decliners in lung function.

Conclusions: The present results suggest that while urinary DES/IDES excretion is related to COPD, it is not a sensitive or specific biomarker for COPD diagnosis or prognosis.

Keywords: desmosine, isodesmosine, COPD, biomarker, urine, ECLIPSE

Introduction

This article contains supplemental material.

Desmosine (DES) and isodesmosine (IDES) are 2 positional isomers that crosslink tropoelastin fibers within mature elastin.1 Elastic fibers are present in lung structures including alveoli, alveolar ducts, airways, vasculature and pleura. Thus, when elastin degradation takes place (e.g., as a result of emphysema), DES/IDES (free forms) and DES/IDES-containing peptides (bound forms) are released.2 For this reason, the measurement of DES/IDES has been extensively discussed as a potential indicator of elevated lung elastin turnover as well as a potential marker of the effectiveness of agents with the potential to reduce elastic fiber breakdown.3-5 This is of particular interest in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a disease characterized by the presence of airflow obstruction mainly caused by chronic bronchitis and/or emphysema.6 Up to now, airflow obstruction reflected by a reduced forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) has been the gold standard marker of COPD progression, response to therapy, and prediction of mortality.7 However, it has proven to be a weak indicator of future exacerbations, unable to predict lung function decline as well as ineffective for developing treatment regimes that can significantly reduce mortality rates or alter the disease course.8,9 For this reason, there is an increasing need for biomarkers that provide more specific information regarding disease activity and the underlying pathological processes of COPD.10,11 In this respect, the development of biomarkers that enable differentiation of individuals with a slow versus fast decline in lung function would be of particular importance for the recognition and treatment of the early stages of the disease.12,13 In the last few years, a few studies have been performed in order to investigate the usefulness of urinary DES and IDES in differentiating COPD individuals from healthy control individuals,14-17 in differentiating slow from fast decliners in lung function,18,19 in predicting COPD exacerbations,20,21 as well as in assessing the effect of different treatment regimens on disease progression.22,23 However, in spite of the efforts made so far, the clinical utility and validity of urinary DES/IDES measurements remains unproven and DES/IDES is still far from being considered a reliable biomarker for COPD diagnosis or prognosis. This is due to the lack of standardized methodologies for the quantification of DES and IDES, as well as a lack of consensus on what should be quantified (free or total DES, IDES or DES+IDES) and in which biological fluid (urine, plasma, sputum). In addition, most studies used a low sample size and did not consider possible confounding factors unrelated to COPD. Only the studies of Lindberg et al24 and Huang et al20 were performed with more than 50 individuals and Lindberg et al considered confounding factors. There is thus a need for large-scale studies in well characterized samples using fully validated analytical methods in well-matched cohorts to see whether the level of DES/IDES may be used to address relevant questions in COPD. In the present work, we employed a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method validated according to the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency guidelines for the measurement of free urinary DES/IDES25 in 365 individuals from the Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Indentify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints (ECLIPSE) cohort (NCT00292552).26 The aims of the present work were to investigate whether a) there are confounding factors influencing urinary DES/IDES levels in a population of smoking and non-smoking individuals with and without COPD; b) urinary DES/IDES levels enable the differentiation between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals; c) urinary DES/IDES levels can be used to differentiate between COPD individuals with a fast or slow decline in lung function.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

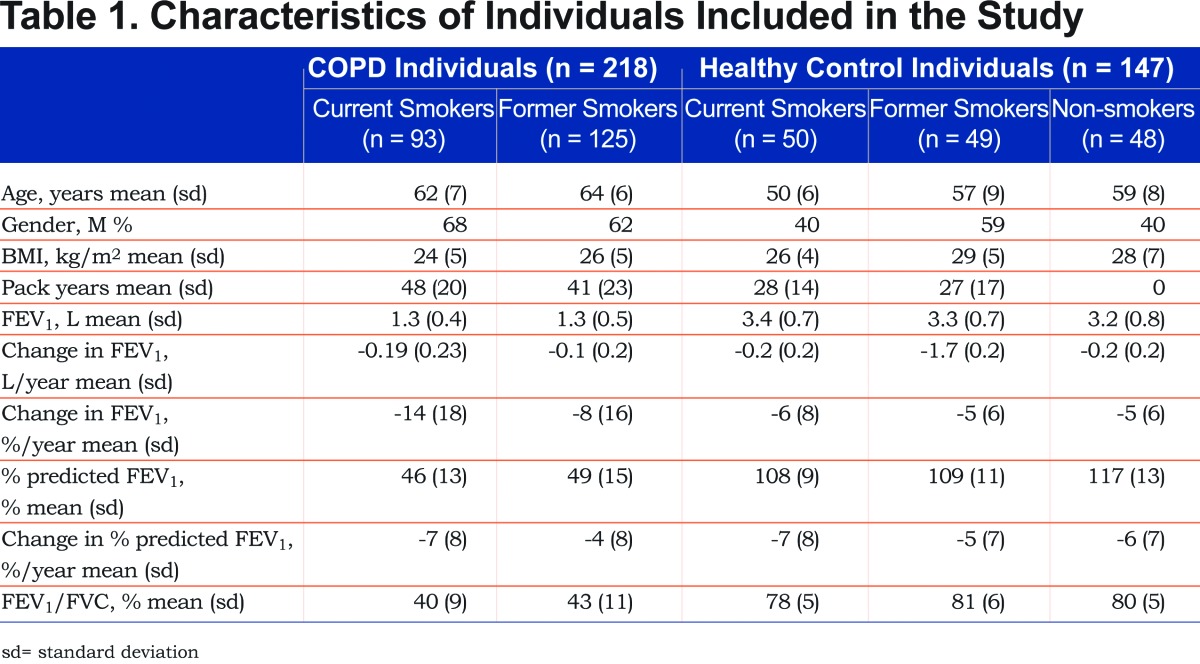

Urine samples were obtained from 365 individuals at the 1 year study visit from the ECLIPSE (NCT00292552, GlaxoSmithKline Study No. SCO104960) cohort.26 (The ECLIPSE study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines and was approved by the relevant ethics and review boards at the participating centers.) These individuals comprise 218 individuals with COPD (17% with chronic bronchitis, 125 former smokers and 93 current smokers) and 147 control individuals (48 non-smokers, 49 former smokers, 50 current smokers). A detailed group description can be found in Table 1. COPD individuals were on average slightly older than healthy control individuals as well as comprising more males (64% versus 46%). COPD individuals were current and former smokers, while healthy control individuals were divided into non-, former and current smokers. COPD individuals who reported an exacerbation during the 4 weeks preceding enrollment were excluded. Lung function decline was defined as the change in FEV1 over time expressed as %/year (change in FEV1 [L/year] / FEV1 [L]*100).

Determination of Urinary DES and IDES

Free urinary DES and IDES were determined as described before.25 Briefly, DES/IDES was extracted from 0.5 mL urine using an Oasis HLB solid phase extraction cartridge (Waters, Manchester, UK) and heptafluorobutyric acid as an ion-pairing reagent. Purified DES and IDES were separated by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Agilent, 1200 series) on a reversed phase column (Atlantis® dC18, Waters). Both isomers were quantified by selected reaction monitoring on a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent, G6410B) in the positive ion mode. D4-DES and D4-IDES were used as internal standards. Urine creatinine was determined with the ADVIA®Chemistry system and the Creatinine_2 test (Siemens, Munich, Germany).

Statistical Methods

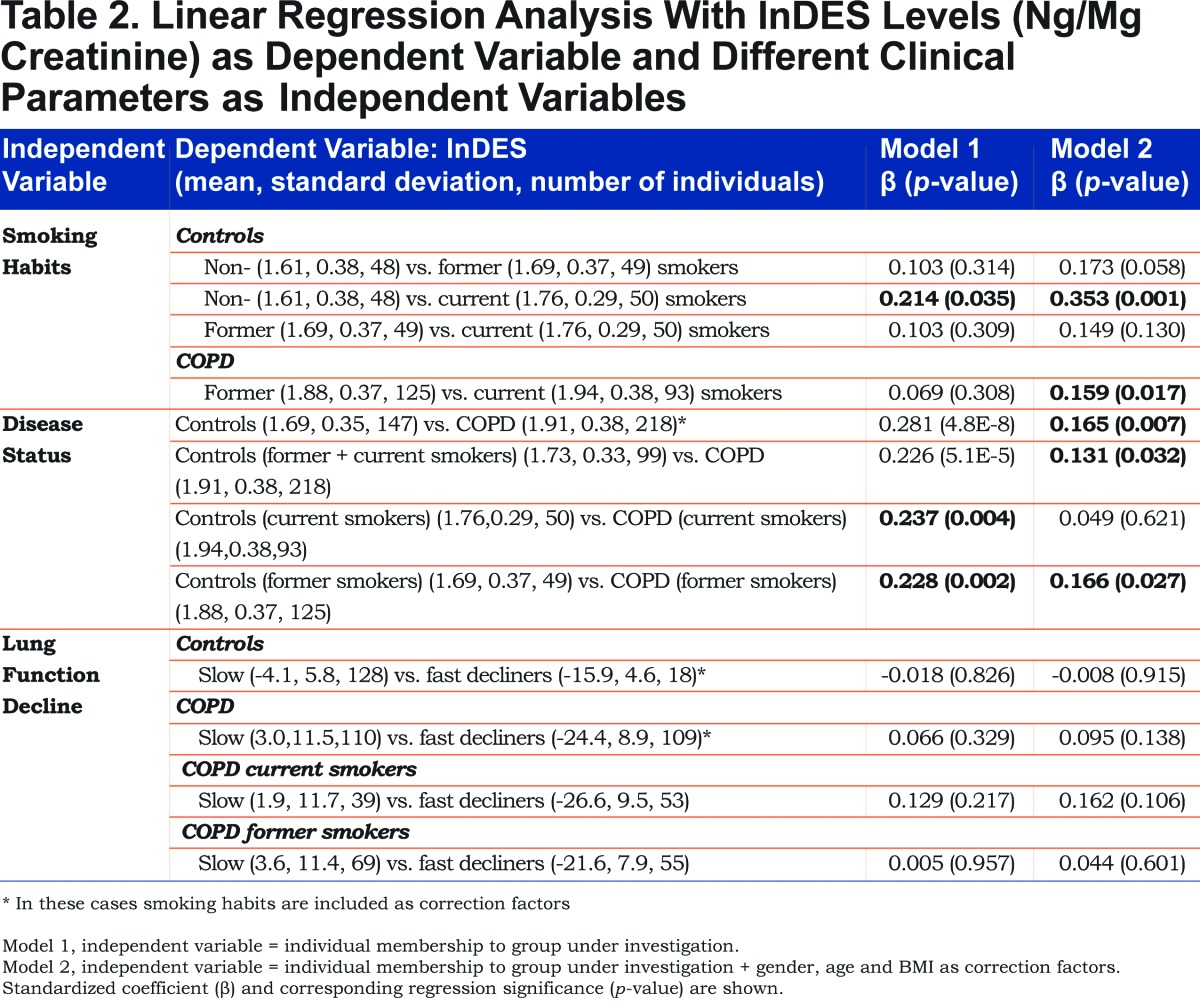

Linear regression was used to investigate the relationship between the natural logarithm of desmosine (lnDES, DES expressed in ng DES / mg creatinine) as dependent variable and the membership of the different individuals to the groups under investigation (current smokers, non-smokers, former smokers, COPD individuals, healthy control individuals, slow decliners, fast decliners; see Table 2 for details) as independent variables. The relationship between the dependent variable and the independent variables was investigated with 2 models. In Model 1, the independent variable (smoking habits, disease status, lung function decline) had 2 categories based on whether it belonged to the group under investigation or not (values of 1 and 0, respectively). In Model 2, gender, age, body mass index (BMI) and smoking habits (when applicable) were corrected for to account for possible confounding factors. The standardized coefficient (β) is indicative of the difference between the mean lnDES values in the 2 categories of an independent variable. The resulting p-values were employed to investigate the significance in differentiating between the 2 categories of the independent variable. The influence of possible confounding factors (gender, age, BMI and smoking habits) on lnDES urinary excretion was investigated by linear regression using lnDES as dependent variable and the confounding factors as independent variables. All statistical analyses, box plots and ROC curves were performed with SPSS (IBM, Statistics 22).

Results

Urinary DES and IDES levels were measured in 365 individuals including COPD patients (current and former smokers), and healthy control individuals (current, former and non-smokers) with slow or fast decline in lung function. While DES and IDES were quantified separately, we observed a constant DES to IDES ratio of 1.5 (n=365, RSD = 10%) for the investigated individuals independent of their health status and decline in lung function in agreement with other studies.19,27 We will therefore only refer to the DES data for simplicity reasons. The mean levels of urinary DES in the different groups are given in Table 2.

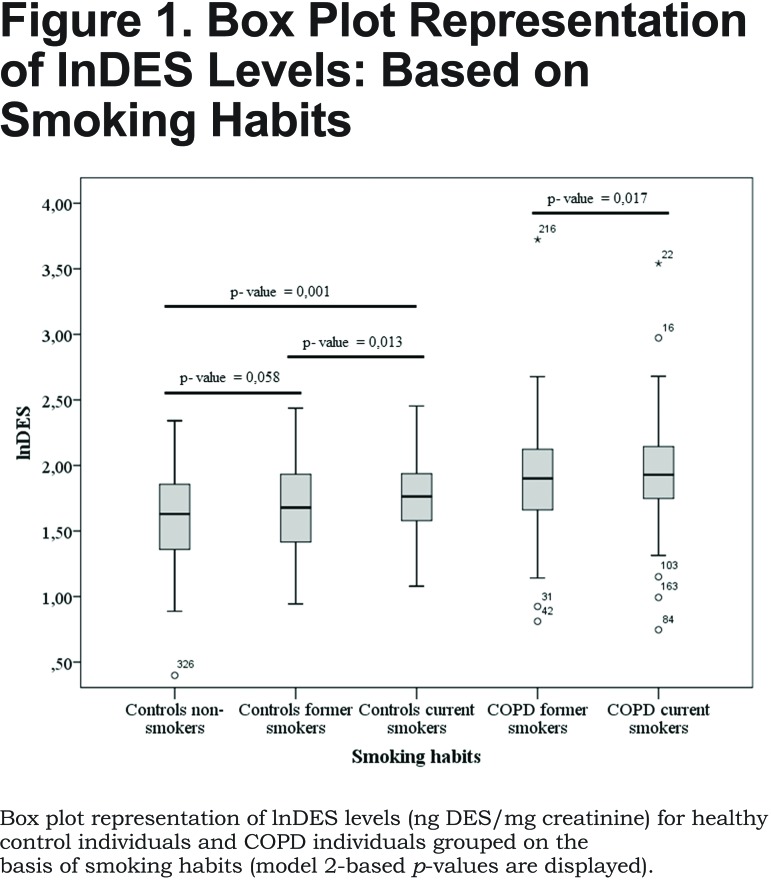

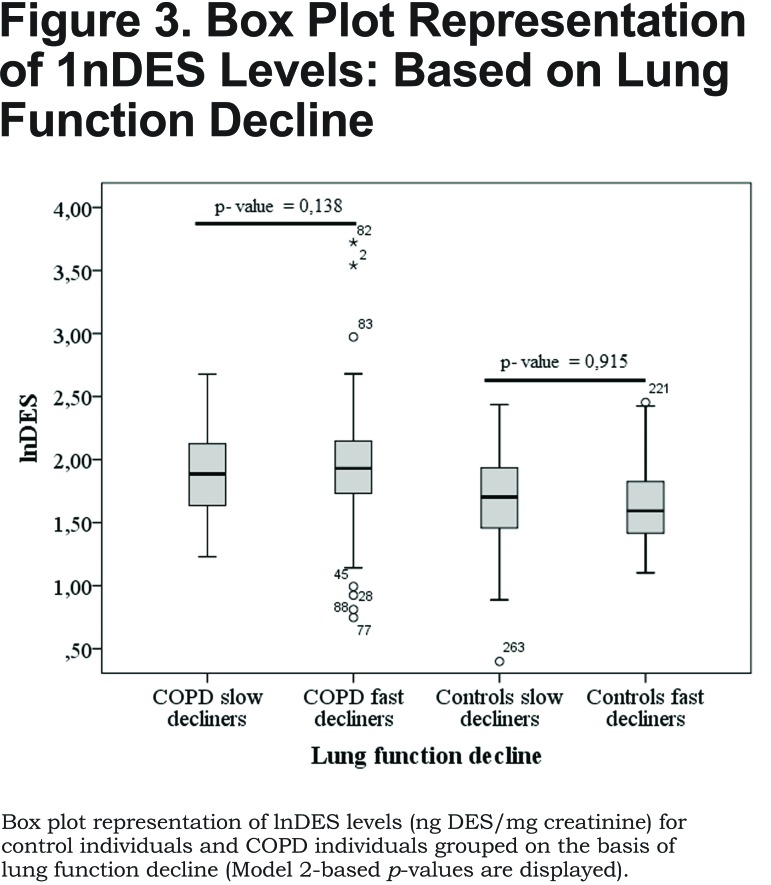

Based on smoking habits, no statistically relevant differences in lnDES (p=0.308, Table 2, Model 1) were observed between former and current smokers among the COPD individuals. Statistically relevant differences were observed between non- and current smokers among the healthy control individuals, although significance was low (p=0.035, Table 2, Model 1). DES urinary excretion allowed a statistically significant differentiation between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals independent of the smoking habits (p = 4.8 x 10-8, ''disease status'' in Table 2, Model 1). However, DES urinary levels could not be used to differentiate slow and fast decliners in lung function independently of their health status or smoking habits (p>0.05, ''lung function decline'' in Table 2, Model 1). Similar results were obtained for different definitions of lung function decline (change in FEV1 [L/year] or change in % predicted FEV1 [%/year]).

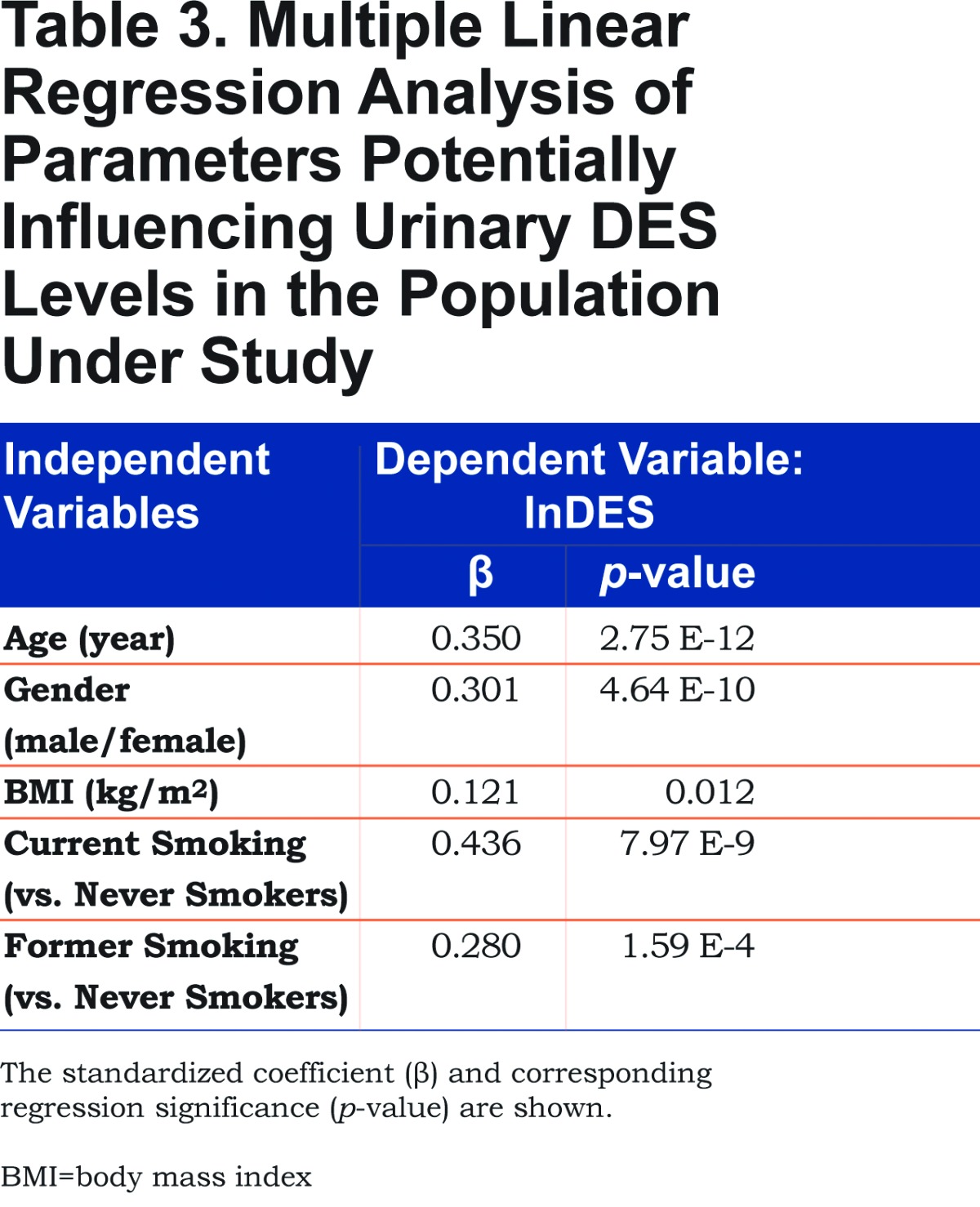

A previous study showed that age, gender and BMI may have an influence on urinary excretion of DES and illustrated the importance of adequately correcting for these factors (especially age).24 Thus, we investigated whether factors such as age, gender, BMI or smoking habits may influence urinary DES excretion and thus need to be corrected for. The influence of age, gender, BMI and smoking habits on urinary DES excretion in individuals with and without COPD was evaluated by multiple linear regression analysis (Table 3). Results show that all of these factors have an influence on urinary DES levels (p<0.05) with a major contribution of age, gender and smoking habits (current versus former and never-smoker).

After correcting for confounding factors (gender, age, BMI and smoking habits, Model 2), a statistically relevant difference was observed between COPD current and former smokers (p=0.017, Table 2, Model 2). In healthy control individuals the only statistically relevant difference was observed between non- and current smokers (p=0.001, Table 2, Model 2) as already observed before correcting for gender, age and BMI. After correction for gender, age, BMI and smoking habits, statistically relevant differences were also observed between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals (p=0.007, Table 2, Model 2) although significance was lowered due to the confounding effect of age, gender and BMI on urinary DES excretion. If individuals are grouped based on smoking habits, statistically relevant differences were still observed between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals with the exception of current smokers (p=0.621, Table 2, Model 2) due to the general influence of current smoking on DES excretion (Table 3) especially in healthy control individuals (Table 2, compare Models 1 and 2). In spite of the correction for confounding factors, no statistically relevant differences were observed between slow and fast decliners in lung function (lung function decline, Table 2, Model 2). Similar results were obtained for different definitions of lung function decline (change in FEV1 [L/year] or change in % predicted FEV1 [%/year]) (Table 1SI and Figure 1SI in the online supplementary data (1.8MB, pdf) ).

Discussion

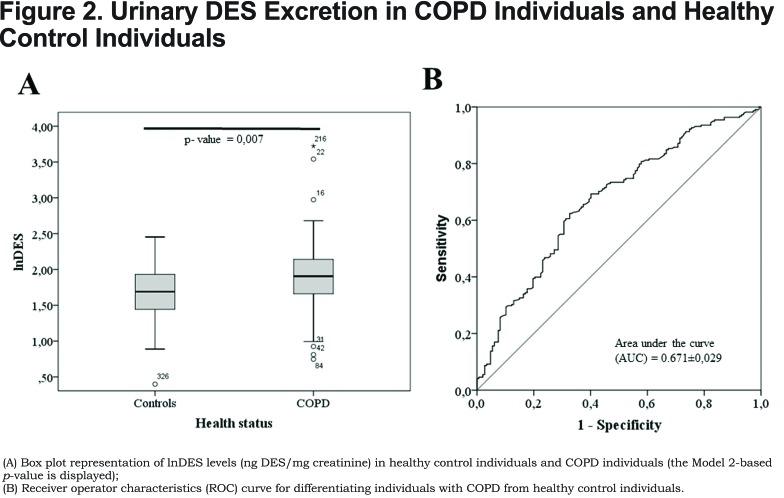

The present study, comprising a large number of COPD individuals and control individuals, shows that a) gender, age, BMI and smoking habits have a strong influence on DES urinary excretion and need to be considered as confounding factors when investigating urinary DES as a disease biomarker; b) urinary DES excretion is related to COPD enabling the differentiation of COPD individuals and healthy control individuals, although assay sensitivity and specificity are low (62% and 73%, respectively); c) urinary DES excretion cannot be used as a prognostic biomarker to predict the decline of FEV1 in COPD since it does not allow the differentiation between COPD individuals with fast and slow decline in lung function.

In COPD, lung elastin degradation can take place as a consequence of exposure to cigarette smoke, among other factors.28 For this reason, it is important to investigate whether smoking influences DES urinary excretion and whether smoking habits need to be taken into account when using DES as a COPD biomarker. Our results show a trend towards higher DES values in both control individuals and COPD individuals when comparing non-, former and current smokers (Table 2, Figure 1). However, differences among the groups were only statistically significant in healthy control individuals when comparing current and non-smokers (p=0.035, Table 2, Model 1). These results are in line with previous publications reporting a trend towards increased urinary DES/IDES excretion in relation to smoking without reaching statistically significant values.15,20,29 Lindberg and co-workers24 observed that urinary DES/IDES was significantly associated with smoking habits after correction for age, gender and BMI in 349 individuals. We obtained similar results with a statistically significant difference between former and current smokers among COPD individuals after correction for gender, age and BMI (p=0.017, Table 2, Model 2). In the case of healthy control individuals, correction for these factors led to a more significant differentiation between non-smokers and current smokers (p = 0.001), between non-smokers and former smokers (p = 0.058), and between former and current smokers (p=0.130) albeit that statistical significance (p < 0.05) was not reached in the 2 latter cases (Table 2, Model 2). Thus, it can be concluded that current smoking has a considerable effect on urinary DES/IDES excretion (Tables 1 and Table 2) in COPD individuals and even more so in healthy control individuals. Smoking and COPD are both contributing to elastin degradation, thus, if DES values are not corrected for smoking habits misleading results may be obtained for urinary DES excretion in relation to COPD.

Gender, age, and BMI are further confounding factors influencing urinary DES excretion (Table 3) and need to be taken into account when investigating the utility of urinary DES as a COPD biomarker. Thus, differences between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals (Figure 2A) were evaluated before and after correction for these factors (Table 2, Models 1 and 2, respectively). Our results show statistically significant differences between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals (Table 2). However, it has to be pointed out that the difference between healthy control individuals and COPD individuals is lower after correction for gender, age, BMI and smoking habits due to the additional effect of current smoking on urinary DES excretion. Furthermore, in spite of the statistically relevant difference observed between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals (p-value=0.007, Table 2, Model 2), there is considerable overlap between groups (Figure 2A) resulting in an assay with rather low sensitivity and specificity (62% and 73%, respectively, Figure 2B). Previous studies produced contradictory results in this respect. While a few studies observed statistically relevant differences between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals,15,17,27,29 Huang and co-workers20 reported no elevation of urinary DES in stable COPD (only in COPD during exacerbations). These discrepancies may be due to the high inter-individual variability of urinary DES excretion (Figure 2), the influence of confounding factors, the highly variable excretion of urinary DES over time (especially for COPD individuals),30 as well as differences in sample size between studies.

Finally, we investigated the capability of urinary DES to reflect lung function decline by comparing individuals with fast lung function decline (fast decliners, with a decline in FEV1 [%/year] of more than 12%) with those having slow lung function decline (slow decliners, with a decline in FEV1 [%/year] of less than 12%). We observed a trend towards higher DES urinary excretion in COPD fast decliners when compared to COPD slow decliners (Table 2, Figure 3). However, differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05, Table 2), independent of smoking habits. Control individuals even showed a trend towards increasing DES urinary excretion in slow decliners when compared to fast decliners (Table 2, Figure 3), but this effect was not statistically significant (p > 0.05, Table 2). In this respect, previous studies showed contradictory results. According to Gottlieb and co-workers,19 the mean urinary excretion of DES was 36% higher (30% after adjustment for age and lean body mass) in individuals with fast lung function decline (n=10) than in individuals with slow lung function decline (n=8). However, in spite of the observed differences, a large variability of DES excretion in the group of fast decliners resulted in a considerable overlap with the group of slow decliners. On the other hand, Boutin and co-workers18 observed a statistically lower excretion of urinary DES in fast decliners (n=9) when compared to slow decliners (n=11). Considering the rather small number of individuals and the large inter-individual variability, it is hard to draw definitive conclusions from these studies.

A potential limitation of our study is the use of single-point urine samples, which are less representative than urine collected over 24 hours. In addition, as urinary DES excretion in COPD individuals can vary over time,30 assessing DES excretion over the complete 3-year period of the ECLIPSE study might lead to better correlations with lung function decline. However, it was our aim to see whether fast and slow decliners could be discriminated from each other using a single urinary DES measurement, as this is much easier to implement in clinical practice. Another limitation might be not taking into account the effect decreased renal function has on desmosine excretion into urine. However, close relationships between desmosine concentrations in urine and plasma were reported by Lindberg et al in another comparable COPD cohort.24 Furthermore, we expressed desmosine in ng DES / mg creatinine. Finally, within the group of COPD individuals, 83% were diagnosed as having emphysema, while the rest are individuals in which other pathological processes may lead to a different urinary DES excretion pattern. However, considering only the emphysema group among the COPD individuals did not lead to a statistically significant relation between urinary DES levels and lung function decline. One possible explanation could be that other elastin-containing tissues contribute to desmosine excreted in urine, as only 19% has been estimated to result from elastin turnover in the lung.31 Another possible explanation could be that we did select too many COPD patients with rather mild emphysema. The selection of emphysema in our study was based on the ECLIPSE definition, including individuals with more than 10% of lung volume with a density of -950 Hounsfield units or less during a maximal inspiratory breath hold.32 This has led to the rather high 83% prevalence of emphysema in our COPD group. We further did not observe any association between DES excretion and loss in lung density.

In summary, our study shows that there is no need to quantify DES and IDES separately, as there is a constant ratio between both isomers independent of health status or decline in lung function. Our results corroborate the findings of Lindberg et al24 regarding the effect of gender, age, BMI or smoking habits on urinary DES excretion. After correction for these confounding factors, a statistically significant difference between COPD individuals and healthy control individuals was observed (p=0.007), although current smoking seems to be the main factor affecting DES excretion, as there is no statistically significant difference between current smokers whether they have COPD or not. These results emphasize the need to correct for confounding factors (especially current smoking) when investigating urinary DES excretion as a COPD biomarker. Our data show further that a single measurement of urinary DES excretion cannot predict lung function decline in stable COPD individuals.

Abbreviations

desmosine, DES; isodesmosine, IDES; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, LC-MS/MS; Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate Endpoints, ECLIPSE; body mass index, BMI; forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FEV1; natural logarithm of desmosine, lnDES; high performance liquid chromatography, HPLC; receiver operator characteristics, ROC

Funding Statement

Dutch Technology Foundation (STW) perspectief program P12-04

References

- 1. Foster JA,Curtiss SW. The regulation of lung elastin synthesis. Am J Physiol. 1990;259(2):L13-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chrzanowski P,Keller S,Cerreta J,Mandl I,Turino GM. Elastin content of normal and emphysematous lung parenchyma. Am J Med. 1980;69(3):351-359. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0002-9343(80)90004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Turino GM,Lin YY,He J,Cantor JO,Ma S. Elastin degradation: An effective biomarker in COPD. COPD. 2012;9(4):435-438. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2012.697753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Casaburi R,Celli B,Crapo J,et al. The COPD biomarker qualification consortium (CBQC). COPD. 2013;10(3):367-377. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2012.752807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luisetti M,Stolk J,Iadarola P. Desmosine, a biomarker for COPD: Old and in the way. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(4):797-798. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00172911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Viegi G,Pistelli F,Sherrill DL,Maio S,Baldacci S,Carrozzi L. Definition, epidemiology and natural history of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2007;30(5):993-1013. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00082507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kristan SS. Blood specimen biomarkers of inflammation, matrix degradation, angiogenesis, and cardiac involvement: A future useful tool in assessing clinical outcomes of COPD patients in clinical practice? . Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 2013;61(6):469-481. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00005-013-0237-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sin DD,Vestbo J. Biomarkers in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(6):543-545. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/pats.200904-019DS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Russell RE. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Getting it right. Does optimal management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease alter disease progression and improve survival?Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20(2):127-131. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/mcp.0000000000000030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Faner R,Tal-Singer R,Riley JH,et al. Lessons from ECLIPSE: A review of COPD biomarkers. Thorax. 2014;69(7):666-672. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pelaia G,Busceti MT,Maselli R,et al. Application of proteomics and peptidomics to COPD. Biomed Res Int. 2014. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/764581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tashkin DP. Variations in FEV1 decline over time in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its implications. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19(2):116-124. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835d8ea4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higashimoto Y,Iwata T,Okada M,Hiroaki S,Fukuda K,Tohda Y. Serum biomarkers as predictors of lung function decline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2009;103(8):1231-1238. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2009.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Albarbarawi O,Barton A,Lin ZS,et al. Measurement of urinary total desmosine and isodesmosine using isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2010;82(9):3745-3750. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac100152f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cocci F,Miniati M,Monti S,et al. Urinary desmosine excretion is inversely correlated with the extent of emphysema in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34(6):594-604. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1357-2725(02)00015-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Devenport NA,Reynolds JC,Parkash V,Cook J,Weston DJ,Creaser CS. Determination of free desmosine and isodesmosine as urinary biomarkers of lung disorder using ultra performance liquid chromatography-ion mobility-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B-Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879(32):3797-3801. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ma S,Turino GM,Lin YY. Quantitation of desmosine and isodesmosine in urine, plasma, and sputum by LC-MS/MS as biomarkers for elastin degradation. J Chromatogr B-Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879(21):1893-1898. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Boutin M,Berthelette C,Gervais FG,et al. High-sensitivity NanoLC-MS/MS analysis of urinary desmosine and isodesmosine. Anal Chem. 2009;81(5):1881-1887. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac801745d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gottlieb DJ,Stone PJ,Sparrow D,et al. Urinary desmosine excretion in smokers with and without rapid decline of lung function - the normative aging study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154(5):1290-1295. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.154.5.8912738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Huang JTJ,Chaudhuri R,Albarbarawi O,Barton A,Grierson C,Rauchhaus P,et al. Clinical validity of plasma and urinary desmosine as biomarkers for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 2012;67(6):502-8. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fiorenza D,Viglio S,Lupi A,et al. Urinary desmosine excretion in acute exacerbations of COPD: A preliminary report. Respir Med. 2002;96(2):110-114. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/rmed.2001.1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dahl R,Titlestad I,Lindqvist A,et al. Effects of an oral MMP-9 and-12 inhibitor, AZD1236, on biomarkers in moderate/severe COPD: A randomised controlled trial. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012;25(2):169-177. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pupt.2011.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stockley R,De Soyza A,Gunawardena K,et al. Phase II study of a neutrophil elastase inhibitor (AZD9668) in patients with bronchiectasis. Respir Med. 2013;107(4):524-533. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2012.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lindberg CA,Engstrom G,de Verdier MG,et al. Total desmosines in plasma and urine correlate with lung function. Eur Respir J. 2012;39(4):839-845. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00064611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ongay S,Hendriks G,Hermans J,et al. Quantification of free and total desmosine and isodesmosine in human urine by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: A comparison of the surrogate-analyte and the surrogate-matrix approach for quantitation. J Chromatogr A. 2014;1326:13-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2013.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vestbo J,Anderson W,Coxson HO,et al. Evaluation of COPD longitudinally to identify predictive surrogate end-points (ECLIPSE). Eur Respir J. 2008;31(4):869-873. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00111707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma S,Lin YY,Turino GM. Measurements of desmosine and isodesmosine by mass spectrometry in COPD. Chest. 2007;131(5):1363-1371. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-2251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Slowik N,Ma S,He J,et al. The effect of secondhand smoke exposure on markers of elastin degradation. Chest. 2011;140(4):946-953. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-2298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Viglio S,Iadarola P,Lupi A,et al. MEKC of desmosine and isodesmosine in urine of chronic destructive lung disease patients. Eur Respir J. 2000;15(6):1039-1045. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.01511.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ferrari F,Fumagalli M,Piccinini P,et al. Micellar electrokinetic chromatography with laser induced detection and liquid chromatography tandem mass-spectrometry-based desmosine assays in urine of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A comparative analysis. J Chromatogr A. 2012;1266:103-109. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2012.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stone PJ,Gottlieb DJ,Oconnor GT,et al. Elastin and collagen degradation products in urine of smokers with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary-disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(4):952-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vestbo J,Edward LD,Scanlon PD,et al. Changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second over time in COPD. N Eng J Med. 2011;365(13):1184-1192. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This article contains supplemental material.