Among men who have sex with men, urethral lymphogranuloma venereum was diagnosed 15 times less often than anorectal LGV. Genital-anal contact seems not the only mode of transmission. Other modes like oral-anal transmission should be considered.

Abstract

In contrast to anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), few urogenital LGV cases are reported in men who have sex with men. Lymphogranuloma venereum was diagnosed in 0.06% (7/12,174) urine samples, and 0.9% (109/12,174) anorectal samples. Genital-anal transmission seems unlikely the only mode of transmission. Other modes like oral-anal transmission should be considered.

Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is an invasive ulcerative sexually transmitted infection (STI) caused by the Chlamydia trachomatis (Ct) LGV biovar (ompA genovars L1, L2 and L3).1 Since 2003 an LGV epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM) is ongoing in Europe, North America, and Australia.2 LGV is associated with high-risk behavior, reflected in high rates of STI co-infections like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (in up to 82.2% of the cases) and hepatitis C.3–6 It is still unknown whether the increased frequency of STI coinfections found in HIV-infected MSM is due to increased susceptibility associated with immunodeficiency and/or immune restoration, or a network factor associated with risk behavior.4

Recent reports suggest an increase of LGV diagnoses in Europe in recent years.7–9 Mainly anorectal infections have been diagnosed, whereas the frequency of urogenital and pharyngeal LGV diagnoses seems rare.10–13 Assuming that most anorectal infections are caused by receptive genital-anal contact, the discrepancy between the frequency of anorectal and urethral infections remains unexplained.

In a previous study, alternative transmission modes for the transmission of anorectal infections were suggested, such as fisting and/or sharing of sex toys.2 Yet, in a more recent systematic study, we found no evidence in support of this hypothesis.4 Tissue tropism of L2b (the most frequently found strain among MSM) with a predilection to infect anorectal mucosa as opposed to urogenital mucosa was thought to be another explanation for the discrepancy in the frequency of urethral as opposed to anorectal infections, yet we could not prove this.14

Currently, most guidelines do not recommend routine testing for urethral LGV,15,16 except for the European International Union against STI LGV guideline.17 Earlier, we reported 2.1% LGV positivity rate in MSM with a concurrent anorectal LGV infection and a 6.8% urethral LGV positivity in their sexual partners.18 This suggested that urethral LGV infections are a possible link in the ongoing transmission of LGV in MSM. To indicate its contribution to the current LGV epidemic, we aimed to determine the positivity rate of urethral LGV among MSM.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

In the STI outpatient clinic of Amsterdam, the Netherlands, MSM are offered free screening for Ct (urethral and pharyngeal), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Ng) (urethral and pharyngeal), syphilis, hepatitis B, and using an opt-out strategy for HIV.19,20 If the client reports receptive anal sex in the previous 6 months, additionally, anorectal Ct and Ng infections are tested. All clinical findings, diagnoses, and subsequent treatment are recorded in an electronic patient database along with patient characteristics and information on sexual behavior.

Prospectively, urine samples were collected from all MSM visiting the STI outpatient clinic between March 2014 and July 2015 and were screened for Ct by amplification with a very sensitive molecular screening assay (Aptima Combo test, Hologic, USA). Positive samples were genotyped using an in-house pmpH quantitative polymerase chain reaction to differentiate between LGV and non-LGV type infections.21,22 If the pmpH test was nontypable (mainly due to insufficient DNA), or tested positive for a non-LGV infection, the result was considered negative for an LGV infection. The same strategy was used for Ct-positive anorectal samples. MSM without an anorectal test were excluded.

Statistical Analysis and Data Collection

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.19 (SPSS, Chicago, Ill). We analyzed whether determinants of MSM with an anorectal LGV infection deffered from MSM with a urethral LGV infection, using Fisher test. Tests were 2-sided and considered significant at P less than 0.05. Sexual preference and number of sexual partners referred to the period 6 months before consultation. HIV status was based on self-reported history of HIV. Urethral symptoms were defined as discharge, dysuria, and/or pruritus. Anorectal symptoms were defined as discharge and/or a burning sensation. A concurrent STI diagnosis was defined as Ct (non-LGV) or LGV at another anatomical location (eye/pharyngeal/urogenital/anorectal), Ng and/or infectious syphilis diagnosed at the same consultation. Men with a concurrent anorectal LGV and urogenital LGV infection were categorized in the urethral LGV infection group.

RESULTS

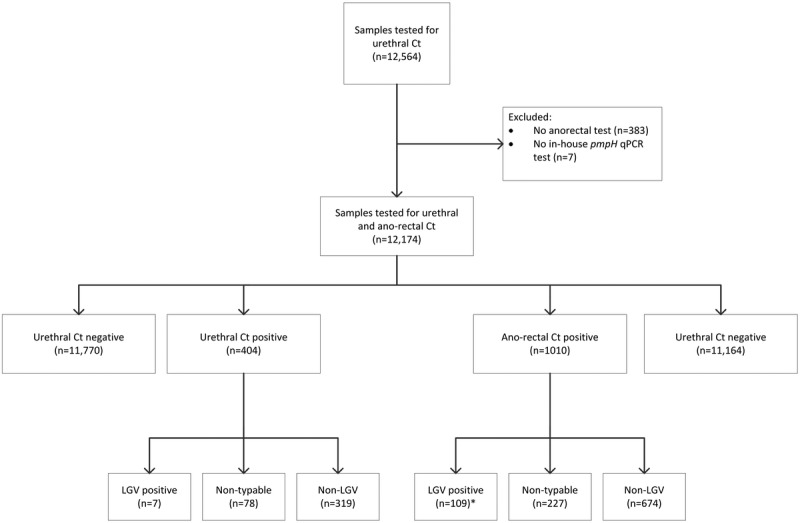

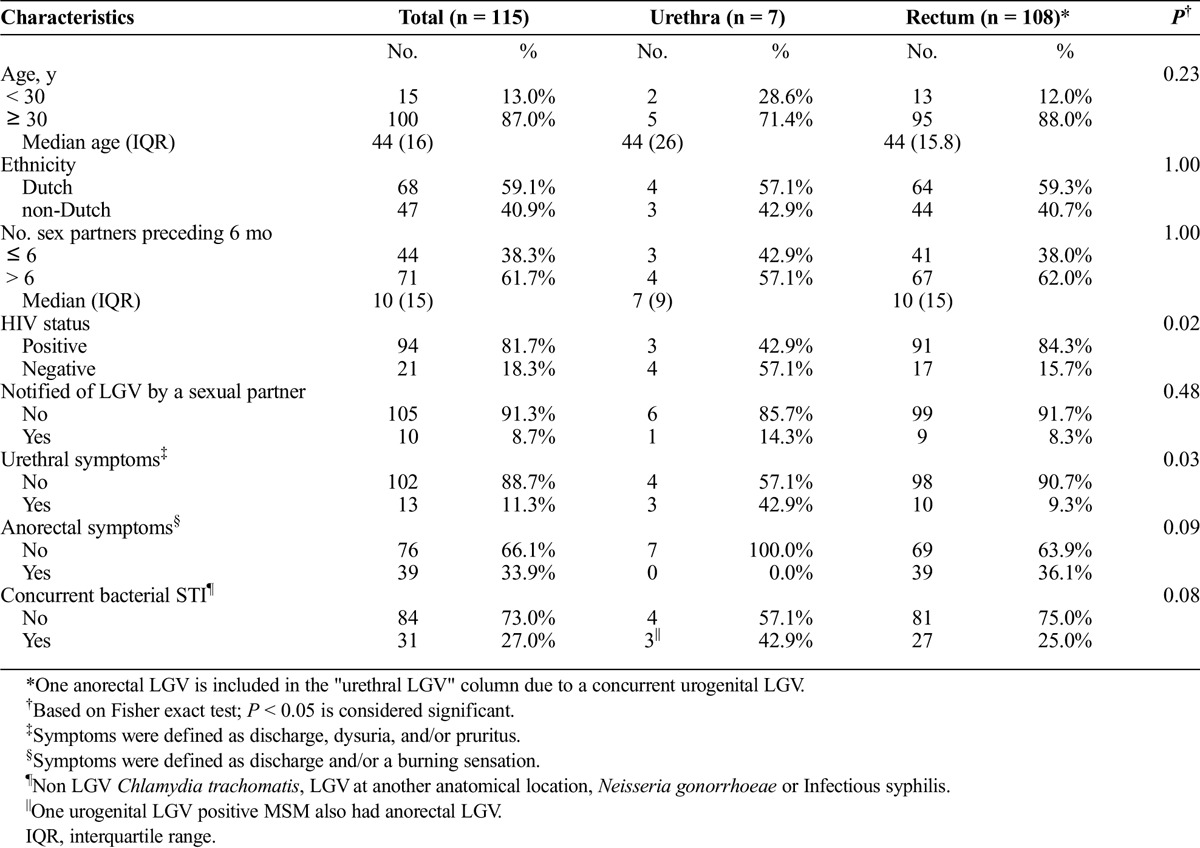

During the inclusion period, 12,564 screening tests were performed for urethral Ct infections (Fig. 1). In 383 visits, no anorectal test was performed, and in 7 Ct-positive tests, no pmpH quantitative polymerase chain reaction was executed; these were all excluded from the analyses. In 12,174 tests, 404 (3.3%) tested positive for urethral Ct, of which 319 (78.9%) were negative for an LGV type infection, 78 (19.3%) were nontypable and 7 (1.7%) tested LGV-positive. In total, 1010 (8.0%) samples tested positive for anorectal Ct, of which 674 (66.7%) were negative for an LGV type infection, 227 (22.5%) were nontypable and 109 (10.8%) tested LGV-positive. Overall, we found a urethral LGV positivity rate of 0.06% (7/12,174; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.02–0.12) and an anorectal positivity rate of 0.9% (109/12,174; 95% CI, 0.74–1.08). Of those 7 with urethral LGV, 4 had urethral symptoms, 1 had a concurrent anorectal LGV infection, 3 were HIV co-infected, and 1 was notified for LGV. Of the 108 with anorectal LGV, 39 (36.1%) had anorectal symptoms, 91 (84.3%) were HIV coinfected, and 9 (8.3%) were notified for LGV (Table 1). Compared with MSM with urethral LGV, those with anorectal LGV were significantly more often HIV coinfected (P = 0,02).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart of 12,564 visits during which C. trachomatis (Ct) tests were performed in men who have sex with men at the STI outpatient clinic in Amsterdam, March 2014 to July 2015. *One patient with anorectal LGV had a urethral LGV co-infection; therefore, he was included in the urethral LGV group.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of 115 MSM With an LGV Infection Visiting the STI Outpatient Clinic in Amsterdam March 2014 to July 2015, by Anatomical Site

DISCUSSION

The observed positivity rate of urethral LGV infections (0.06%) is 15 times lower compared with the positivity rate of anorectal LGV infections of 0.9% found among MSM at the STI clinic. Therefore, it seems likely that other modes of transmission are needed to explain the current LGV epidemic in MSM. As thought earlier, transmission via toys is not supported based on epidemiological data.2 Nor does tissue tropism seem a likely explanation for the discrepancy found in the rate of anorectal and urethral LGV infections.14

A strength of this study is the high number and unbiased population of MSM that was prospectively tested for both urethral and anorectal LGV because all clients were included irrespective of symptoms, notification, or prioritization based on sexual risk assessment.

The number of pmpH nontypable samples from the urethral and anorectal location was high: respectively, 19.3% (78/404) and 22.5% (227/1010). We considered nontypable samples LGV negative because it is known that these samples have a low bacterial load and LGV types are successful growers.23 Nevertheless, a chance remains that we have missed LGV infections. However, in an earlier study using a genotyping Reverse Hybridization Assay, we showed that at least one third of the pmpH nontypable samples were non-LGV types.23 Moreover, because there was no significant difference in the ratio of nontypable samples from urethral or anorectal locations, the discrepancy between anatomical locations remains unexplained.

In a 2014 convenience sample study from Madrid, Spain, 13,585 samples, including 2420 urethral samples, were tested in 8407 clients of whom 3282 MSM. In total, 10 (2.6%) of 338 urethral Ct-positive samples were LGV positive.11 This is slightly higher than the 1.7% found here. In a 2013 German convenience sample study, 1883 MSM rectal and pharyngeal specimens were tested for LGV and 522 urethral samples were obtained; 8 were Ct-positive of which none were LGV-positive.12 In a 2009 prospective multicentre study from the United Kingdom, 4825 urethral and 6778 rectal samples from consecutive MSM attending for sexual health screening were screened for LGV.13 The LGV positivity in rectal samples was 0.90% (95% CI, 0.69%–1.16%) and in urethral samples 0.04% (95% CI, 0.01%–0.16%), very comparable to our results. None of the 3 studies tested such a number of MSM both for anorectal and urethral LGV infections as done here. Moreover, we compared characteristics of MSM with LGV at different anatomical locations. As found earlier,9 men with urethral LGV were significantly less often HIV coinfected as opposed to men with anorectal LGV, respectively, 42.9% and 84.3% (P = 0.02), indicating that the latter is a population with higher risk taking behavior. Unfortunately, the number of urethral LGV cases is too small to look into risk behavior in closer detail.

The low prevalence of cases found here does not justify routine screening for urethral LGV. Yet, clinicians should be aware of possible treatment failures as we described earlier in a case series of MSM with advanced inguinal LGV with bubo formation that were likely caused by missed and/or undertreated urethral LGV infections.24 Apart from direct consequences for individual patients, missed urethral LGV infections likely also contribute to ongoing transmission.

As we described earlier,9 a considerable part of LGV diagnosis found in this study were asymptomatic: approximately 36% of the anorectal infections, and 4 of the 7 urethral LGV infections. Because LGV requires prolonged treatment and follow-up compared with non-LGV chlamydia infections, this finding stresses the clinical importance to exclude LGV in high-risk groups, irrespective of complaints.

With the skewed anorectal/urethral LGV ratio of 15:1, it seems unlikely that urethral LGV infections are responsible for all anorectal LGV transmissions. Recently, we suggested that oral infections may have a role in LGV transmission via ano-oral sex.25 Schachter et al26 demonstrated in early work that neonates with an initial chlamydia conjunctivitis or pneumonia, subsequently shedded Ct from the vagina and rectum. They suggested that the vagina and conjunctivae are exposed to chlamydia at birth and that pneumonia and gastrointestinal infection occur later via oropharyngeal transmission. This paradigm could possibly also account as an explanation for the unanswered findings in the current LGV epidemic in MSM. Apart from genital-anal transmission, oropharyngeal infection may occur via ano-oral sex (also known as rimming).25 Subsequently, LGV organisms pass through the gastrointestinal tract to cause anorectal LGV proctitis. Whether this paradigm proves right remains to be seen, and its contributing factor to the LGV epidemic in MSM needs to be addressed in future research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest and Sources of Funding: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.de Vrieze NH, de Vries HJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum among men who have sex with men. An epidemiological and clinical review. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014; 12:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieuwenhuis RF, Ossewaarde JM, Götz HM, et al. Resurgence of lymphogranuloma venereum in Western Europe: An outbreak of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar l2 proctitis in The Netherlands among men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 39:996–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rönn MM, Ward H. The association between lymphogranuloma venereum and HIV among men who have sex with men: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van der Bij AK, Spaargaren J, Morré SA, et al. Diagnostic and clinical implications of anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum in men who have sex with men: A retrospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 2006; 42:186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Götz HM, van Doornum G, Niesters HG, et al. A cluster of acute hepatitis C virus infection among men who have sex with men—results from contact tracing and public health implications. AIDS 2005; 19:969–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van de Laar TJ, van der Bij AK, Prins M, et al. Increase in HCV incidence among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam most likely caused by sexual transmission. J Infect Dis 2007; 196:230–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Childs T, Simms I, Alexander S, et al. Rapid increase in lymphogranuloma venereum in men who have sex with men, United Kingdom, 2003 to September 2015. Euro Surveill 2015; 20:30076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vargas-Leguas H, Garcia de Olalla P, Arando M, et al. Lymphogranuloma venereum: A hidden emerging problem, Barcelona, 2011. Euro Surveill 2012; 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vrieze NH, van Rooijen M, Schim van der Loeff MF, et al. Anorectal and inguinal lymphogranuloma venereum among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Trends over time, symptomatology and concurrent infections. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89:548–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korhonen S, Hiltunen-Back E, Puolakkainen M. Genotyping of Chlamydia trachomatis in rectal and pharyngeal specimens: Identification of LGV genotypes in Finland. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88:465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez-Domínguez M, Puerta T, Menéndez B, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characterization of a lymphogranuloma venereum outbreak in Madrid, Spain: Co-circulation of two variants. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20:219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haar K, Dudareva-Vizule S, Wisplinghoff H, et al. Lymphogranuloma venereum in men screened for pharyngeal and rectal infection, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19:488–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ward H, Alexander S, Carder C, et al. The prevalence of lymphogranuloma venereum infection in men who have sex with men: Results of a multicentre case finding study. Sex Transm Infect 2009; 85:173–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Versteeg B, van Rooijen MS, Schim van der Loeff MF, et al. No indication for tissue tropism in urogenital and anorectal Chlamydia trachomatis infections using high-resolution multilocus sequence typing. BMC Infect Dis 2014; 14:464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White J, O'Farrel N, Daniels D, et al. 2013 UK National Guideline for the management of lymphogranuloma venereum: Clinical Effectiveness Group of the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (CEG/BASHH) Guideline development group. Int J STD AIDS 2013; 24:593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; 64:1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Vries HJ, Zingoni A, Kreuter A, et al. 2013 European guideline on the management of lymphogranuloma venereum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Vrieze NH, van Rooijen M, Speksnijder AG, et al. Urethral lymphogranuloma venereum infections in men with anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum and their partners: The missing link in the current epidemic? Sex Transm Dis 2013; 40:607–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heijman TL, van der Bij AK, de Vries HJ, et al. Effectiveness of a risk-based visitor-prioritizing system at a sexually transmitted infection outpatient clinic. Sex Transm Dis 2007; 34:508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heijman TL, Stolte IG, Thiesbrummel HF, et al. Opting out increases HIV testing in a large sexually transmitted infections outpatient clinic. Sex Transm Infect 2009; 85:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morre SA, Spaargaren J, Fennema JS, et al. Real-time polymerase chain reaction to diagnose lymphogranuloma venereum. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11:1311–1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morre SA, Ouburg S, van Agtmael MA, et al. Lymphogranuloma venereum diagnostics: From culture to real-time quadriplex polymerase chain reaction. Sex Transm Infect 2008; 84:252–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quint KD, Bom RJ, Quint WG, et al. Anal infections with concomitant Chlamydia trachomatis genotypes among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. BMC Infect Dis 2011; 11:63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oud EV, de Vrieze NH, de Meij A, et al. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and management of inguinal lymphogranuloma venereum: Important lessons from a case series. Sex Transm Infect 2014; 90:279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Vries HJ. The enigma of lymphogranuloma venereum spread in men who have sex with men: Does ano-oral transmission plays a role? Sex Transm Dis 2016; 43:420–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schachter J, Grossman M, Holt J, et al. Infection with Chlamydia trachomatis: Involvement of multiple anatomic sites in neonates. J Infect Dis 1979; 139:232–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]