Abstract

Background

In a flipped classroom approach, learners view educational content prior to class and engage in active learning during didactic sessions.

Objective

We hypothesized that a flipped classroom improves knowledge acquisition and retention for residents compared to traditional lecture, and that residents prefer this approach.

Methods

We completed 2 iterations of a study in 2014 and 2015. Institutions were assigned to either flipped classroom or traditional lecture for 4 weekly sessions. The flipped classroom consisted of reviewing a 15-minute video, followed by 45-minute in-class interactive sessions with audience response questions, think-pair-share questions, and case discussions. The traditional lecture approach consisted of a 55-minute lecture given by faculty with 5 minutes for questions. Residents completed 3 knowledge tests (pretest, posttest, and 4-month retention) and surveys of their perceptions of the didactic sessions. A linear mixed model was used to compare the effect of both formats on knowledge acquisition and retention.

Results

Of 182 eligible postgraduate year 2 anesthesiology residents, 155 (85%) participated in the entire intervention, and 142 (78%) completed all tests. The flipped classroom approach improved knowledge retention after 4 months (adjusted mean = 6%; P = .014; d = 0.56), and residents preferred the flipped classroom (pre = 46%; post = 82%; P < .001).

Conclusions

The flipped classroom approach to didactic education resulted in a small improvement in knowledge retention and was preferred by anesthesiology residents.

What was known and gap

Residency programs are looking for optimal approaches to teach didactic content.

What is new

A flipped classroom approach with video viewing and 45-minute in-class sessions with active learning was compared to a traditional lecture.

Limitations

Single specialty, single education topic may limit generalizability.

Bottom line

The flipped classroom resulted in a small positive effect on retention at 4 months and was preferred by learners.

Introduction

Determining the most effective and engaging teaching approach remains an important challenge in graduate medical education. Didactic sessions have traditionally been provided in lecture format. The flipped classroom approach reverses this traditional method, with learners completing preclassroom “homework,” and classroom time is used for interactive learning and problem solving. A goal of the flipped classroom is to depart from a passive, teacher-centered approach in favor of learner-centered active learning.1,2

Empirical studies of the flipped classroom in other health professions education have found beneficial effects,3,4 including knowledge gain.5,6 Supporting evidence in medical education is scarce, and most studies involved medical students.7 Published reports in the graduate medical education literature are limited to single site studies.8,9

We examined the flipped classroom in anesthesiology residents at multiple institutions. We hypothesized that it would result in improved knowledge acquisition and retention, compared to traditional lectures, and that learners would prefer the flipped classroom.

Methods

Setting and Participants

Participants consisted of 182 postgraduate year 2 (PGY-2) residents preparing for the American Board of Anesthesiology (ABA) Basic Examination during academic years 2014–2015 and 2015–2016. Eight institutions participated in the study. The University of North Carolina, University of Kentucky, University of Wisconsin, The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, and University of Colorado participated in both academic years. The Medical University of South Carolina, Stony Brook University School of Medicine, and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center joined for the second year.

Design

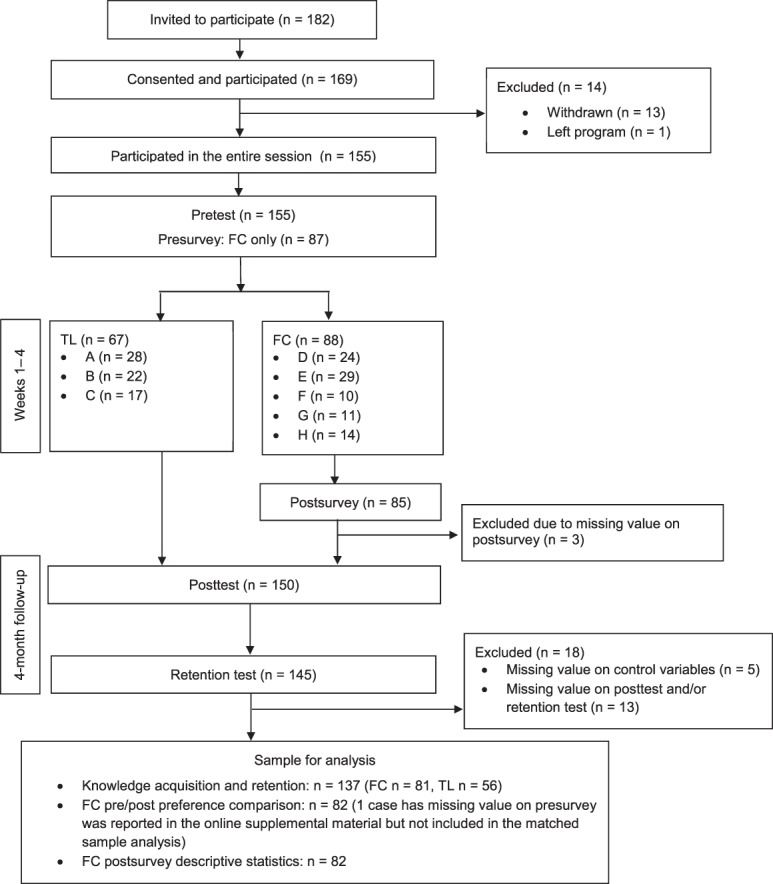

This was a prospective, controlled, multicenter, educational research study. Institutions were assigned to an intervention group based on program size so as to obtain similar numbers of participants across groups, without knowledge of background data. Educational content was delivered for each teaching method (flipped classroom or traditional lecture) in 4 consecutive weekly sessions. A pretest was administered before the intervention, a posttest immediately following the intervention, and a retention test 4 months later (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Research Design and Analysis

Abbreviations: FC, flipped classroom group; TL, traditional lecture group.

Note: The pretest was administered the week preceding the start of the educational block. Each educational session was followed up with a survey to determine how the residents prepared for the session. The posttest was administered at the conclusion of the educational block. Following the last educational session, residents completed attitudinal surveys. The retention test was administered 4 months after the conclusion of the educational sessions. Institutions were deidentified in figure 1 to protect the confidentiality of the participants.

Interventions

Three educators developed the educational sessions. To maintain consistency among content, the same educator developed all materials (flipped classroom and traditional lecture) for a given topic. Materials were peer-reviewed by all educators participating in the first year of the study and were utilized by all sites during both study years. The materials and test questions covered the anesthesia-specific pharmacology portion of the ABA Basic Content Outline.10

Two educators from each institution facilitated all educational sessions. Each facilitator reviewed a podcast, explained the flipped classroom concept, reviewed the educational materials, and discussed content with the first author (S.M.M.) if needed.

Traditional lectures consisted of 55-minute lectures utilizing PowerPoint (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA), followed by 5 minutes for resident questions. Notes were provided for consistency of delivery. For flipped classroom sessions, a 15-minute video was created as a preclass videocast with Snagit (TechSmith, Okemos, MI), consisting of PowerPoint slides with voiceover narrative covering foundational information on the topic. We utilized videos for the prework, as it is believed that the new generation of learners prefers this to reading assignments.11 Flipped classroom learners were asked to preview the videos before the 45-minute in-class sessions. Flipped classroom time was interactive, with educators utilizing audience response questions, think-pair-share questions, and case discussions. To standardize these sessions, slide-based presentations were provided that contained questions in these active learning formats. Video assignments (flipped classroom only) and reading recommendations (both groups) were made available through a learning management system.

Educational sessions were delivered over the same 1-month period each academic year, across all institutions, with 1 group using the flipped classroom and the other using the traditional lecture (Figure 1). Residents received a survey and the pretest 1 week before the sessions began, which gathered data on demographics and experience with and attitudes toward the flipped classroom. Immediately following each educational session, residents received a survey inquiring about their session attendance, video reviewing (flipped classroom only), and amount of time spent reading. At the end of the intervention, residents received the posttest and a survey inquiring about their perceptions of the teaching methods. Residents received a retention test 4 months after the intervention.

Outcomes

A 40-item multiple-choice test was developed to measure the knowledge benchmark (pretest), acquisition (posttest), and retention (4-month retention test). Design and assessment of test questions involved a modified Delphi technique,12,13 with question writing and review by 6 expert anesthesiologist educators to promote content validity.14 Questions were piloted with 26 PGY-2 residents who did not participate in the study. The questions were psychometrically assessed using Rasch analysis and modified as necessary for final use.15 The same test with varied question order was utilized for the pretest, posttest, and retention test, as research found no difference in examinees' performance between identical form and parallel form repeated testing.16 To examine residents' attitudes toward the flipped classroom versus traditional lectures, the authors developed a survey, which was pilot tested and underwent slight modifications.

Each study site was reviewed by its Institutional Review Board and declared exempt or approved.

Statistical Analysis

Primary outcome measures were residents' knowledge acquisition and retention as measured by percentage of correct answers on the posttest and retention test. Linear mixed model was used to assess statistical significance of the effect of each teaching method and time (repeated tests) on knowledge acquisition and retention (ie, percentage of correct answers in posttest and retention test). The statistical model included teaching method, time, and interactions as independent variables. Percentage of correct answers in pretest, age, sex, United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) scores, and the flipped classroom experience were included in the model to control for baseline between-group differences. The correlated nature of error terms due to repeated assessments within each study participant was modeled using an unstructured covariance matrix.

Secondary outcome measures were resident attitudes toward the flipped classroom, and these surveys were only filled out by the residents who experienced this approach. The McNemar-Bowker test was used to track residents' preference. Group comparison on demographics that did not involve repeated measures used an independent t test (ie, time reading prior to class, age, USMLE scores) or a chi-square test (ie, sex, flipped classroom experience). A P value of .05 or less was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Given the sample of 142 residents (n = 83 for flipped classroom, n = 59 for traditional lecture) for knowledge acquisition and retention analysis, the effect size of the flipped classroom relative to the traditional lecture should be of value greater than d = 0.50 with probability (power) 0.90 in order to determine a statistical significance at the .05 level.

Results

Of 182 eligible PGY-2 residents, 169 (93%) consented to participate, 155 (85%) participated in the entire intervention, and 142 (78%; n = 83 for flipped classroom; n = 59 for traditional lecture) completed all 3 knowledge tests. The flipped classroom group (n = 82) also completed both pretest and posttest surveys of their perceptions of this learning model.

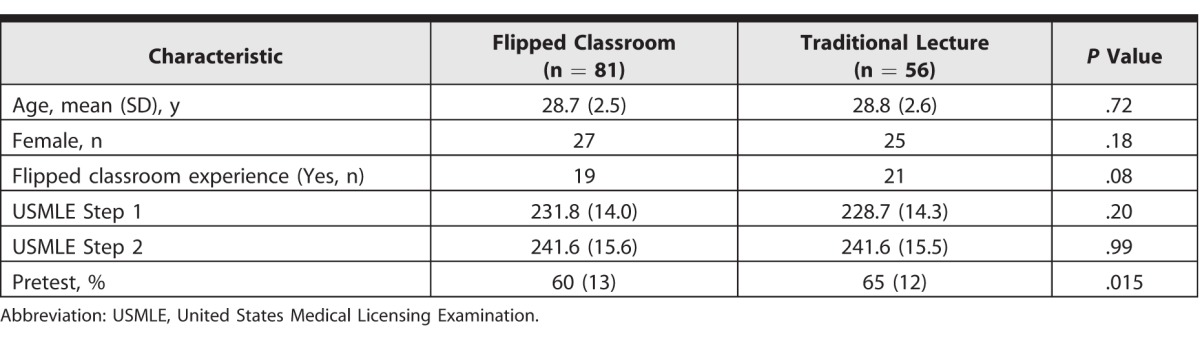

There was no group difference in preclass reading time (P = .10; see the Table for baseline characteristics). Seventy-three of 83 (88%) flipped classroom residents watched at least 75% of the 4 assigned videos prior to class. Two flipped classroom and 3 traditional lecture residents had missing values on some covariates; their data were deleted from the analysis for effect size estimation. The pretest percentage correct was higher for the traditional lecture than for the flipped classroom.

Table.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Teaching Method Group

Knowledge Acquisition and Retention

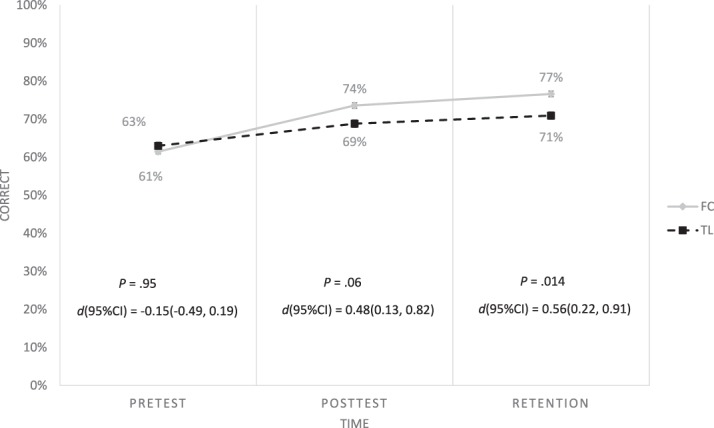

After statistically adjusting for the difference in pretest performance and other control variables in the mixed effects model, the between-group difference on pretest percentage correct was no longer significant (flipped classroom adjusted mean = 61%; traditional lecture adjusted mean = 63%; P = .95). Mixed effects modeling revealed significant interaction (P = .003) between teaching method (flipped classroom and traditional lecture) and time (posttest and retention test), controlling for covariates. As depicted in Figure 2, the effect of the teaching method appears to vary by time. The flipped classroom did not show a difference in knowledge acquisition (posttest adjusted mean = 5%; P = .06; d = 0.48), but demonstrated improved knowledge retention, compared to traditional lecture (retention adjusted mean = 6%; P = .014; d = 0.56).

Figure 2.

Adjusted Means (Least Squares Means) of the Percentage Correct on the Knowledge Test Over Time

Abbreviations: FC, flipped classroom group; TL, traditional lecture group.

Note: Pretest, posttest, and retention stand for adjusted means (least squares mean) of the percentage correct on the pretest, posttest, and 4-month follow-up retention test, respectively. Adjusted mean is the mean of the percentage correct on the test after adjusting for difference in pretest and covariates. Therefore, the adjusted means of pretest percentage correct are different from the means of pretest percentage correct summarized in the Table. Error bars shown are standard error of the adjusted mean obtained from the mixed effect model; effect size d = effect size Cohen's d; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval of d.

Attitudes Toward Flipped Classroom

McNemar-Bowker tests revealed a preference for the flipped classroom (pre = 46%; post = 82%; P < .0001). A frequency Table of residents' preintervention and postintervention preferences and a summary of postintervention survey results with regard to attitude toward teaching methodologies are provided as online supplemental material.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report of a multi-institutional prospective trial in a residency setting comparing the effects of the flipped classroom to a traditional lecture format, with regard to knowledge change and learner preference. While we did not find a difference in knowledge acquisition between the 2 methods, the flipped classroom improved knowledge retention after 4 months (d = 0.56), compared to the traditional lecture, demonstrating a modest beneficial effect.17 The residents who experienced the flipped classroom demonstrated a strong preference to this method. The higher knowledge score at 4 months in the flipped classroom group may have been related to its engaging nature that led to enhancement of triggers during the clinical learning of similar topics over the ensuing 4 months until the retention test, thus amplifying the knowledge gained in the intervention.

A recent review found a small effect (median d = 0.08) of the flipped classroom on knowledge and skill in medical students.7 The flipped classroom may be a useful teaching method in graduate medical education, with its competing demands on learner time and improvement in remote access to content.18–20

Similar to medical students,21–24 residents preferred the flipped classroom. The postintervention survey suggested that residents found the flexibility of watching prerecorded lectures on their own time helpful, believed they would retain more information, and felt the flipped classroom better prepared them for board examinations and clinical practice.

One criticism of determining the utility of the flipped classroom literature is the difficulty to assess if learners are compliant with preclass assignments. Our residents were compliant with a rate of 88%. Factors that may have contributed to our high compliance rate include the fact that participants were volunteers and the curriculum prepared them for a high-stakes examination. However, Heitz et al23 found a one-third noncompliance rate in their learners.

Our study has a few limitations. We assessed the flipped classroom in a single specialty and with only 1 educational topic, making it difficult to generalize the findings to other specialties and topics. Additionally, we solely utilized multiple-choice questions for knowledge assessment. A more profound effect in knowledge gain might be demonstrated through testing involving higher-order thinking such as case analysis, simulations, and workplace-based assessment.

Future research should investigate whether the positive effect of the flipped classroom can be replicated in other specialties and explore why learning appears to continue following the flipped classroom method of teaching.

Conclusion

Our findings revealed anesthesiology residents' preference for the flipped classroom and a beneficial effect of this teaching method on knowledge retention.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Prober CG, Heath C. . Lecture halls without lectures—a proposal for medical education. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366 18: 1657– 1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prober CG, Khan S. . Medical education reimagined: a call to action. Acad Med. 2013; 88 10: 1407– 1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McLaughlin JE, Griffin LM, Esserman DA, et al. . Pharmacy student engagement, performance, and perception in a flipped satellite classroom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013; 77 9: 196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gilboy MB, Heinerichs S, Pazzaglia G. . Enhancing student engagement using the flipped classroom. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015; 47 1: 109– 114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wong TH, Ip EJ, Lopes I, et al. . Pharmacy students' performance and perceptions in a flipped teaching pilot on cardiac arrhythmias. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014; 78 10: 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McLaughlin JE, Rhoney DH. . Comparison of an interactive e-learning preparatory tool and a conventional downloadable handout used within a flipped neurologic pharmacotherapy lecture. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2015; 7 1: 12– 19. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen F, Lui MA, Martinelli SM. . A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education. Med Educ. 2017; 51 6: 585– 597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khandelwal A, Nugus P, Elkoushy MA, et al. . How we made professionalism relevant to twenty-first century residents. Med Teach. 2015; 37 6: 538– 542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tune JD, Sturek M, Basile DP. . Flipped classroom model improves graduate student performance in cardiovascular, respiratory, and renal physiology. Adv Physiol Educ. 2013; 37 4: 316– 320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. American Board of Anesthesiology. Primary certification in anesthesiology. http://www.theaba.org/PDFs/BASIC-Exam/Basic-and-Advanced-ContentOutline. Accessed May 31, 2017.

- 11. Martin SK, Farnan JM, Arora VM. . FUTURE: new strategies for hospitalists to overcome challenges in teaching on today's wards. J Hosp Med. 2013; 8 7: 409– 413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morgan PJ, Lam-McCulloch J, Herold-McIlroy J, et al. . Simulation performance checklist generation using the Delphi technique. Can J Anaesth. 2007; 54 12: 992– 997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hand WR, Bridges KH, Stiegler MP, et al. . Effect of a cognitive aid on adherence to perioperative assessment and management guidelines for the cardiac evaluation of noncardiac surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2014; 120 6: 1339– 1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Messick S. . Meaning and values in test validation: the science and ethics of assessment. Educ Res. 1989; 18 2: 5– 11. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rasch G. . Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feinberg RA, Raymond MR, Haist SA. . Repeat testing effects on credentialing exams: Are repeaters misinformed or uninformed? Educ Meas Issues Pract. 2015; 34 1: 34– 39. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen J. . A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992; 112 1: 155– 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. King AB, Mcevoy MD, Fowler LC, et al. . Disruptive education: training the future generation of perioperative physicians. Anesthesiology. 2016; 125 2: 266– 268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McEvoy MD, Lien CA. . Education in anesthesiology: is it time to expand the focus? A A Case Rep. 2016; 6 12: 380– 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kain ZN, Fitch JC, Kirsch JR, et al. . Future of anesthesiology is perioperative medicine: a call for action. Anesthesiology. 2015; 122 6: 1192– 1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Belfi LM, Bartolotta RJ, Giambrone AE, et al. . “Flipping” the introductory clerkship in radiology: impact on medical student performance and perceptions. Acad Radiol. 2015; 22 6: 794– 801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Evans KH, Thompson AC, O'Brien C, et al. . An innovative blended preclinical curriculum in clinical epidemiology and biostatistics: impact on student satisfaction and performance. Acad Med. 2016; 91 5: 696– 700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Heitz C, Prusakowski M, Willis G, et al. . Does the concept of the flipped classroom extend to the emergency medicine clinical clerkship? West J Emerg Med. 2015; 16 6: 851– 855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liebert CA, Lin DT, Mazer LM, et al. . Effectiveness of the surgery core clerkship flipped classroom: a prospective cohort trial. Am J Surg. 2016; 211 2: 451– 457.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.