Abstract

Background

The flipped classroom model for didactic education has recently gained popularity in medical education; however, there is a paucity of performance data showing its effectiveness for knowledge gain in graduate medical education.

Objective

We assessed whether a flipped classroom module improves knowledge gain compared with a standard lecture.

Methods

We conducted a randomized crossover study in 3 emergency medicine residency programs. Participants were randomized to receive a 50-minute lecture from an expert educator on one subject and a flipped classroom module on the other. The flipped classroom included a 20-minute at-home video and 30 minutes of in-class case discussion. The 2 subjects addressed were headache and acute low back pain. A pretest, immediate posttest, and 90-day retention test were given for each subject.

Results

Of 82 eligible residents, 73 completed both modules. For the low back pain module, mean test scores were not significantly different between the lecture and flipped classroom formats. For the headache module, there were significant differences in performance for a given test date between the flipped classroom and the lecture format. However, differences between groups were less than 1 of 10 examination items, making it difficult to assign educational importance to the differences.

Conclusions

In this crossover study comparing a single flipped classroom module with a standard lecture, we found mixed statistical results for performance measured by multiple-choice questions. As the differences were small, the flipped classroom and lecture were essentially equivalent.

What was known and gap

The flipped classroom has attracted a good deal of attention, yet there is a lack of information on added learning benefits compared with a traditional lecture format.

What is new

A randomized crossover study in emergency medicine compared a 50-minute lecture from an expert educator and a flipped classroom module.

Limitations

Single specialty study limits generalizability; a single lecture may be insufficient to detect differences.

Bottom line

Differences between the 2 formats were small; the flipped classroom and traditional lecture were essentially equivalent.

Introduction

The flipped classroom model has shown benefits to knowledge gain in undergraduate education.1 In this model, lecture material is consumed at home, and in-class time is focused on application, simulation, case-based discussion, or problem solving. Medical education leaders have recently supported the flipped classroom,1,2 leading health professions schools to adopt this approach in preclinical, clinical, and graduate medical education.3–9

The theoretical benefits of a flipped classroom are rooted in social constructivism and active learning.10,11 Social collaboration enables modeling, scaffolding, and feedback that engage students' preconceptions and build on their existing understanding of a topic. This focuses learning toward Bloom's higher levels of analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.12,13

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Review Committee for Emergency Medicine recently changed the weekly educational requirements to allow 1 hour of conference credit for asynchronous learning.14 This shift helped pave the way for emergency medicine residencies in the United States to adopt a flipped classroom approach. Though it has been widely embraced and shows theoretical promise in graduate medical education,15–17 data regarding knowledge gain performance remain sparse. The objective of this study was to explore the difference in knowledge gain performance between a flipped classroom and a traditional lecture module for emergency medicine trainees.

Methods

Setting and Sample

All emergency medicine residents at the University of California, San Francisco–Fresno; Los Angeles County/University of Southern California; and University of California, San Francisco/San Francisco General Hospital were eligible to participate. Each program has a half-day of protected didactic time once a week. Only those who could attend conference on the intervention day were included. The interventions occurred on a different day at each site in October 2014, November 2014, and January 2015.

Instructional Materials

We selected 2 commonly encountered emergency department chief complaints that are a part of the standard-setting American Board of Emergency Medicine Model of the Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine: acute low back pain and acute headache.18 A group of experienced residency faculty (2 program directors and 2 assistant program directors) used a modified Delphi technique to develop learning objectives for each subject. The lecturer (S.P.S.), module developers (J.C., S.S., R.T., J.S.), and local facilitators had no prior knowledge of the assessment instruments.

Flipped Classroom Modules

This curriculum consisted of a 20-minute preparatory video and 30 minutes of in-class discussion for each subject. The videos were professionally recorded and edited by Hippo Education and consisted of a combination of audiovisual formats: (1) full screen of lecturer; (2) split screen with lecturer and PowerPoint (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) presentation; and (3) full screen of PowerPoint with audio voiceover. The videos were hosted on YouTube.com.

The in-class curriculum consisted of faculty-led, case-based discussions written by experienced program faculty (J.C., S.S., R.T., J.S.) with questions on clinical presentation, evaluation, diagnosis, management, and disposition. Faculty members led small groups of 5 to 12 learners through outlined discussions of common cases. Facilitators received no special training apart from a detailed instructor handout.

Standard Lecture Modules

Based on consensus objectives, an author (S.P.S.) prepared a 50-minute PowerPoint-based live lecture for each subject, recorded the short video lectures for the flipped classroom modules, and gave the live lectures at all 3 sites. The sessions included PowerPoint slides, audience interaction, humor, and the Socratic teaching method. To ensure standardization across sites, the lectures were based on the same PowerPoint presentation.

Intervention

We randomized participants to receive the flipped classroom model for 1 subject and the standard lecture for the other. Each participant received an e-mail with a link to the 20-minute online video for their designated flipped classroom subject. The e-mail was sent 5 days and 1 to 3 days prior to the conference date.

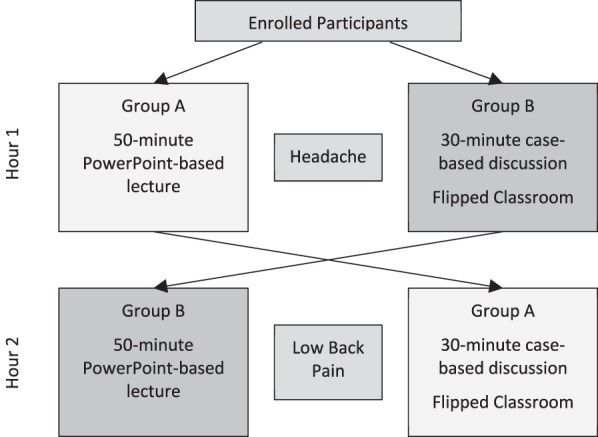

On the day of the interventions, participants received either a standard lecture or the flipped classroom faculty-led discussion for the first subject. The following hour they crossed over and received the other format for the second subject (see Figure). Pretests and immediate posttests were administered on paper on the day of the intervention, and 90-day retention tests were administered on paper or electronically several months later.

Figure.

Crossover Methodology

Validity Evidence for Interpretation of Assessment

Based on feasibility and current practice in formative evaluation of residents, 4 unique 10-item tests were developed: 1 pretest and 1 posttest for each of the 2 subjects. The same posttest was used for both the immediate and 90-day retention tests for each subject. The assessments were developed according to the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing.19 To strengthen evidence of content validity, 2 authors (P.J. and D.J.) with extensive item-writing experience for emergency medicine board review courses developed 60 multiple-choice, National Board of Medical Examiners–style examination questions (30 for each subject). The item writers had access to and mapped their questions to the module objectives, but were blinded to the lecture content, video material, and discussion guides in order to minimize potential bias. We pilot tested the items with 17 second-, third-, and fourth-year residents, some of whom participated in the final study. Cronbach's alpha was used as a measure of internal consistency of each parallel test form to strengthen internal structure evidence.

From the 30 items for each subject, 2 parallel forms of 10-item examinations were assembled, with resulting alpha coefficients of 0.54 and 0.44 for the headache examinations and 0.86 and 0.80 for the back pain examinations, respectively. The 2 parallel forms possessed equivalent difficulty levels for headache (0.76 and 0.82) and for back pain (0.62 and 0.68) by averaging the individual item difficulty on each form. The validity of the 2 forms was established by matching the objectives covered and the diagnoses as described by the content experts who developed the items.

The Institutional Review Board at each site approved the study.

Measures and Analysis

The primary outcome, knowledge gain performance, was determined by change in test scores.

Mean scores for each module under each condition were collected at 3 times: preintervention, immediate postintervention, and at the 90- to 120-day postintervention. The immediate posttest and 90- to 120-day retention examinations were identical for each subject.

A repeated measure analysis of variance with a 2 × 3 design was used to assess the difference between the 2 teaching modalities in performance on the knowledge tests.

A prospective power analysis indicated that to detect a moderately high effect size (f = 0.3) with an 85% power at an alpha level of .05, there needed to be a total sample size of 70 subjects and 35 subjects in each study group (flipped versus lecture).

Results

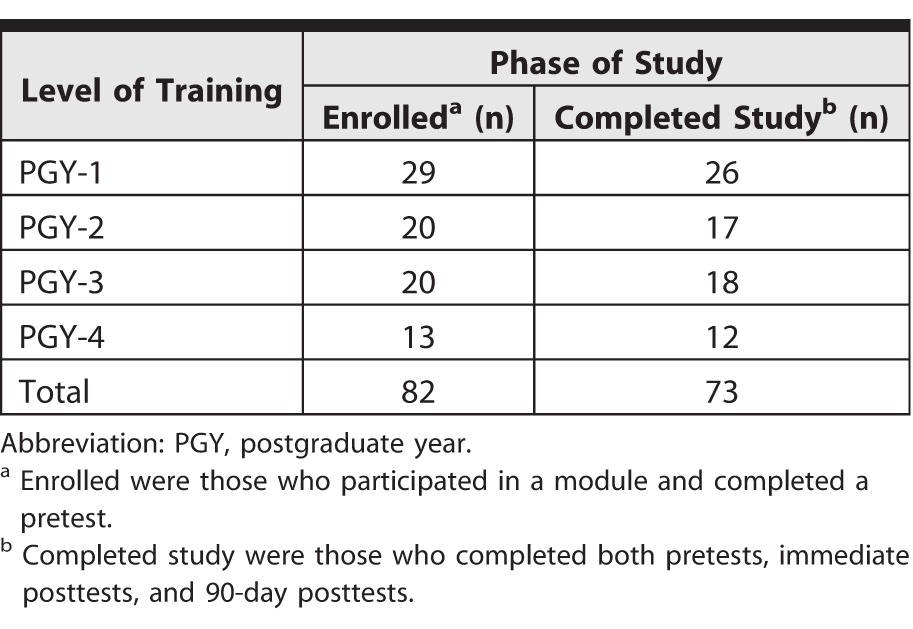

A total of 82 residents enrolled (participated in a module and completed a pretest). Only participants completing the pretest, posttest, and retention test were included in the final analysis (n = 73, 89%). Participant demographics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant Flow Through Study

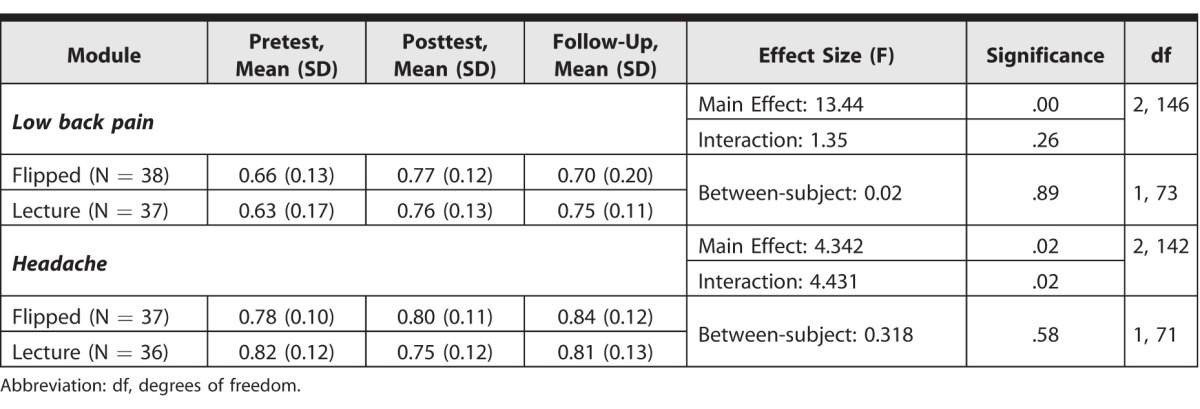

Descriptive information is displayed in Table 2. For the back pain module, there was a significant effect of testing date (ie, preintervention, postintervention, or 90-day), but the interaction effect did not reach statistical significance. Overall mean test scores were significantly different for the pretest, immediate posttest, and 90-day test, but there were no significant differences in performance between the lecture and flipped classroom format.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics

For the headache module, both the effect of testing date and the interaction effect reached statistical significance (Table 2). Overall mean test scores were significantly different for pretest, immediate posttest, and 90-day test administrations, and there were significant differences in performance for a given test date between the flipped classroom and lecture formats. Test performance steadily increased across the 3 testing dates for residents in the flipped classroom format. The difference was less than 1 of the 30 examination items.

Discussion

In a crossover trial comparing a single flipped classroom module with a standard lecture for knowledge gain performance and retention, we found mixed statistical results that are essentially equivalent. Mean test score variation could only be attributed to differences in teaching method for the headache module. The differences between the groups on both modules were less than a single examination item, making it difficult to assign practical significance. At a minimum, performance in the flipped classroom was no worse than that in the standard lecture. This finding may be useful in light of other potential theoretical benefits of the flipped classroom.

Our study fits into a landscape of flipped classroom studies with mixed results. Studies in undergraduate education have shown a significant effect,2 while use of the flipped classroom in health professions education studies have shown mixed results.5,20–22 An extensive search of the PubMed and ERIC databases found no studies describing knowledge gain data in graduate medical education. Several possibilities exist to explain why the flipped classroom format we studied showed these results. A recent study found that the flipped classroom does not result in greater learning gains compared with a traditional classroom when both use an active learning, constructivist approach. Learning gains in either format may be a result of the active learning style of instruction rather than the order in which the instructor participated in the learning process.23

Most studies that demonstrate benefit involve implementation of the flipped classroom over an entire course rather than single days of instruction. It may be that the effect of the flipped classroom is too small to see on any given day, but there may be a cumulative effect to improve learning sustainability.24

It may be difficult to detect differences in knowledge gain performance with high-performing learners who have high academic achievement regardless of classroom design.25 Medical residents generally perform well on multiple-choice tests regardless of instructional conditions, thus obscuring and overruling most of the differences in effects of educational interventions.26

Our study has several limitations. While 10-question multiple-choice tests are common in graduate medical education to evaluate curricular goals and are a feasible way to rapidly test, the number of items on the assessment limits its reliability and generalizability. Our study was not powered for subgroup analysis, and it is unclear whether certain levels of trainees fared better in the flipped classroom modules. Comparisons between formats could be confounded by differences not related to the flipped classroom format itself. Though the same lecturer gave all live lectures based off identical PowerPoint slide decks, it is possible material was covered in varying depths at different sites. Although we had a significant dropout rate, almost 90% of enrolled participants completed the retention test, which is comparable to that of other published studies.27

There may be other benefits to a flipped classroom related to social interaction, self-regulation, and scheduling flexibility that we did not measure. Also important are studies that determine the parts of in-class discussion that are highest yield for different stages of learners, the ideal length and importance of the at-home videos, and the most effective design, features, and layout of the videos.28

Conclusion

In a crossover study comparing a single flipped classroom module with a standard lecture in emergency medicine programs, the differences found were small, and the flipped classroom and standard lecture were essentially equivalent.

References

- 1. Prober CG, Heath C. . Lecture halls without lectures—a proposal for medical education. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366 18: 1657– 1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mehta NB, Hull AL, Young JB, et al. . Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education. Acad Med. 2013; 88: 1418– 1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McLaughlin JE, Roth MT, Glatt DM, et al. . The flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Acad Med. 2014; 89 2: 236– 243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nematollahi S, St John PA, Adamas-Rappaport WJ. . Lessons learned with a flipped classroom. Med Educ. 2015; 49 11: 1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morgan H, McLean K, Chapman C, et al. . The flipped classroom for medical students. Clin Teach. 2015; 12 3: 155– 160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leung JY, Kumta SM, Jin Y, et al. . Short review of the flipped classroom approach. Med Educ. 2014; 48 11: 1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vincent DS. . Out of the wilderness: flipping the classroom to advance scholarship in an internal medicine residency program. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2014; 73 11 suppl 2: 2– 3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ramar K, Hale CW, Dankbar EC. . Innovative model of delivering quality improvement education for trainees—a pilot project. Med Educ Online. 2015; 20: 28764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sadosty AT, Goyal DG, Hern HG Jr et al. . Alternatives to the conference status quo: summary recommendations from the 2008 CORD Academic Assembly Conference Alternatives workgroup. Acad Emerg Med. 2009; 16 suppl 2: 25– 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vygotsky LS. . Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Haidet P, Morgan RO, O'Malley K, et al. . A controlled trial of active versus passive learning strategies in a large group setting. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2004; 9 1: 15– 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sherbino J, Chan T, Schiff K. . The reverse classroom: lectures on your own and homework with faculty. CJEM. 2013; 15 3: 178– 180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bloom BS, Engelhart MD, Furst EJ, et al. . Analysis, Synthesis, and Evaluation sections. : Bloom BS, . Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York, NY: David McKay; 1956: 144–161; 162–183; 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, Review Committee for Emergency Medicine. Frequently asked questions: emergency medicine. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/FAQ/110_emergency_medicine_FAQs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2017.

- 15. Young TP, Bailey CJ, Guptill M, et al. . The flipped classroom: a modality for mixed asynchronous and synchronous learning in a residency program. West J Emerg Med. 2014; 15 7: 938– 944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rose E, Claudius I, Tabatabai R, et al. . The flipped classroom in emergency medicine using online videos with interpolated questions. J Emerg Med. 2016; 51 3: 284– 291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tan E, Brainard A, Larkin GL. . Acceptability of the flipped classroom approach for in-house teaching in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Australas. 2015; 27 5: 453– 459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Counselman FL, Borenstein MA, Chisholm CD, et al. . The 2013 model of the clinical practice of emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2014; 21 5: 574– 598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, National Council on Measurement in Education, et al. Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whillier S, Lystad RP. . No differences in grades or level of satisfaction in a flipped classroom for neuroanatomy. J Chiropr Educ. 2015; 29 2: 127– 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Belfi LM, Bartolotta RJ, Giambrone AE, et al. . “Flipping” the introductory clerkship in radiology: impact on medical student performance and perceptions. Acad Radiol. 2015; 22 6: 794– 801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wong TH, Ip EJ, Lopes I, et al. . Pharmacy students' performance and perceptions in a flipped teaching pilot on cardiac arrhythmias. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014; 78 10: 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jensen JL, Kummer TA, d M Godoy PD. Improvements from a flipped classroom may simply be the fruits of active learning. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015; 14 1:ar5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. van Vliet EA, Winnips JC, Brouwer N. . Flipped-class pedagogy enhances student metacognition and collaborative-learning strategies in higher education but effect does not persist. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015; 14 3pii:ar26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lape NK, Levy R, Yong DH, et al. . Probing the flipped classroom: a controlled study of teaching and learning outcomes in undergraduate engineering and mathematics. https://www.asee.org/file_server/papers/attachment/file/0005/6431/ASEE_2015_NSF_Grantees_poster_session_DRAFT3_040515.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2017.

- 26. ten Cate TJ, Kusurkar RA, Williams GC. . How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education: AMEE Guide No. 59. Med Teach. 2011; 33 12: 961– 973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cook DA, Dupras DM, Thompson WG, . Web-based learning in residents' continuity clinics: a randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med. 2005; 80 1: 90– 97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guo PJ, Kim J, Rubin R. . How video production affects student engagement: an empirical study of MOOC videos. https://groups.csail.mit.edu/uid/other-pubs/las2014-pguo-engagement.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2017.