Abstract

Background

Improved understanding and management of health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) represents one of the greatest unmet needs for patients with head and neck (H&N) malignancies. The purpose of the current study is to prospectively measure HR-QOL associated with different anatomical (H&N) surgical resections.

Methods

A prospective analysis of HR-QOL was performed in patients undergoing surgical resection with flap reconstruction for stage II or III H&N malignancies. Patients completed the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire 30 and EORTC H&N Cancer Module 35 preoperatively, and at set postoperative time points. Scores were compared with a paired t-test.

Results

75 patients were analyzed. The proportion of the cohort not alive at 2 years was 53%. Physical, role, and social functioning scores at 3 months were significantly lower than preoperative values (p<.05). At 12 months postoperatively, none of the function or global QOL scores differed from preoperative levels, whereas 5 of the symptom scales remained below baseline. At one year postoperatively maxillectomy, partial glossectomy, and oral lining defects had better function and less symptoms than mandibulectomy, laryngectomy, and total glossectomy. From 6 to 12 months postoperatively, partial glossectomy and oral lining defects had greater global QOL than laryngectomies (p<.05).

Conclusion

Postoperative HR-QOL is associated with the anatomic location of the H&N surgical resection. Preoperative teaching should be targeted for common ablative defects with postoperative expectations adjusted appropriately. Because surgery negatively impacts HR-QOL in the immediate post-operative period, the limited survivorship should be reviewed with patients.

Introduction

Despite recent advances in the treatment of head and neck malignancies, the rate of disease-specific morbidity and mortality remains high.1–3 Furthermore, while the availability of microvascular reconstruction has been viewed as a major advance in the field, the resultant surgical sequelae continue to be a source of diminished postoperative function and health-related quality of life (HR-QOL).4–10 Improved understanding and management of the HR-QOL issues surrounding head and neck cancer perhaps represents the greatest unmet need for patients.

Previous analysis of HR-QOL in the head and neck literature has grouped patients together in a variety of ways. For example, the HR-QOL outcomes associated with specific reconstructive flaps have been compared.11,12 Alternatively, incongruent defects have been analyzed together despite observable differences in clinical outcomes. Categorization of mandibulectomies and partial glossectomies together can lead to a loss of granularity about HR-QOL specific for each procedure.13–15 While these approaches provide some insight into the patient experience, they do not capture the different and subtle functional impairments created by tumor resections in distinct anatomical areas.

It is crucial that both the surgeon and patient have a clear understanding of the anticipated impact of surgery on HR-QOL, alleviation of symptoms, and their projected evolution during the postoperative period. The purpose of the current study is to objectively measure the HR-QOL associated with common head and neck surgical defects. Specifically, the hypothesis is that HR-QOL varies between oncologic head and neck surgical resections. As part of the multidisciplinary team caring for these complex patients, the findings will be useful for plastic surgeons to counsel and adjust expectations.

Methods

After Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained, patients undergoing surgical resection and reconstruction for stage II or III head and neck malignancies at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center were recruited preoperatively and postoperatively. The oncologic and reconstructive procedures were performed at the discretion of the operating surgeons. Patients who were less than 21, did not speak English, were unable to comprehend the content of the questions due to psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairment, or could not complete the preoperative questionnaires were excluded. Patients were recruited from February 2008 until February 2013. Demographic and clinical characteristics were either self reported or collected via chart review. Surgical defects were categorized into the following six categories: partial glossectomy, mandibulectomy, oral lining, maxillectomy, total glossectomy, and laryngectomy.

Patients completed a series of patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires to measure HR-QOL. Questionnaires were administered at four time points: pre-operatively, 3 months (±1 month), 6 months (±1), and 9 months (−1 and +3) post-operatively. Questionnaires solicited a variety of demographic and clinical information including quality of life, health status, general well-being, pain, and psychosocial status. All questionnaires were completed either in clinic or by a mail. The questionnaires are well established, validated instruments used to evaluate patient-reported HR-QOL and symptomatology. The response rate was not tracked uniquely for this study because of an overlapping study that included some of the same patients. The response rate for that study was 39%.

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire-30 Version 3.0 (EORTC QLQ-30) assesses health-related quality of life in cancer patients. It is comprised of 30-items with multi-item scales that evaluate five functional domains (physical functioning, role, emotional, social, and cognitive functioning) and three multi-item symptom scales (fatigue, pain, and emesis). Six single items assess financial impact, dyspnea, sleep disturbance, appetite, diarrhea, and constipation.16

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire Head and Neck Cancer Module-35 (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) was designed to be used in conjunction with the EORTC QLQ-C30.17,18 The head and neck module consists of 35 items that comprise seven multi-item scales including pain, swallowing, senses (taste and smell), speech, social eating, social contact, sexuality and 11 single items scored on four-point Likert-scale. In addition there are five dichotomous items scored in a yes/no format.

Statistical Analysis

EORTC30 and 35 scores were calculated as outlined in the scoring manual.19 Mean scores for different EORTC items were compared at multiple time points and for each surgical defect location, using a paired student t-test.

Results

A total of 75 patients were evaluated from February 2008 until February 2013. Table 1 demonstrates the demographic and treatment characteristics of the cohort. Seventy-three percent of the patients were male with a mean age of 60 years. Table 2 depicts the distribution of surgical defects. Partial glossectomy was the most common (25%), followed by mandibulectomy (23%), and oral lining (16%). A variety of reconstructive techniques were used. The radial forearm free flap was most frequent (40%), along with the rectus abdominis (25%), ALT (11%) and fibula (9%) (Table 3). Amongst the different types of surgical defects evaluated, there were no significant differences in the proportion of patients who had a prior resection or postoperative radiotherapy; however, there were differences in proportions of chemotherapy and preoperative radiation therapy between some groups (Table 4). The proportion of the cohort not alive at 1 and 2 years was 28% and 53% respectively.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (n=75)

| % | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age years mean (range) | 60 (27–87) |

|

| |

| Sex | |

| Male | 73 |

| Female | 27 |

|

| |

| Radiation Therapy | |

| None | 23 |

| Pre-op | 30 |

| Post-op | 35 |

| Both | 11 |

|

| |

| Chemotherapy | |

| None | 51 |

| Pre-op | 27 |

| Post-op | 14 |

| Both | 9 |

|

| |

| Prior Resection | |

| Yes | 34 |

| No | 66 |

|

| |

| Prior Reconstruction | |

| Yes | 10 |

| No | 90 |

|

| |

| N stage | |

| N0 | 15 |

| N≥1 | 85 |

Table 2.

Surgical defects (n=75)

| Defect Type | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Partial Glossectomy | 19 (25) |

| Mandibulectomy | 17 (23) |

| Oral Lining | 12 (16) |

| Maxillectomy | 11 (15) |

| Total Glossectomy | 8 (11) |

| Laryngectomy | 8 (11) |

Table 3.

Distribution of flap types (n= 75)

| Flap Type | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Radial forearm | 30 (40) |

| Rectus abdominis | 19 (25) |

| Anterolateral thigh | 8 (11) |

| Fibula | 7 (9) |

| Pectoralis major | 5 (7) |

| Other | 4 (5) |

| Scapular osteocutaneous | 2 (3) |

Table 4.

Clinical Characteristics (n = 75)

| Prior Resection (%) | Any Chemotherapy (%) | Preoperative Radiation Therapy (%) | Postoperative Radiation Therapy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial glossectomy | 31.6 | 58.8 | 22.2 | 61.1 |

| Oral lining | 25.0 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 41.7 |

| Maxilectomy | 36.4 | 40.0 | 10.0 | 70.0 |

| Mandibulectomy | 35.3 | 62.5 | 56.3 | 18.8 |

| Total glossectomy | 25.0 | 85.7 | 71.4 | 28.6 |

| Laryngectomy | 37.5 | 87.5 | 37.5 | 62.5 |

| p value | = 0.9 | = 0.01 | = 0.02 | = 0.16 |

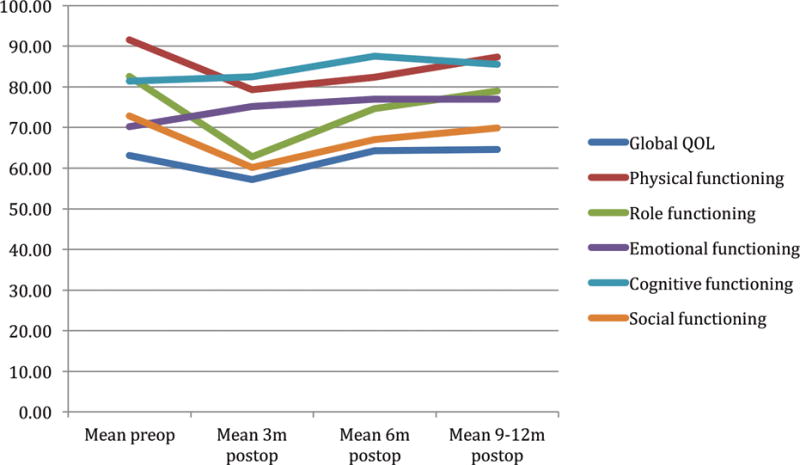

PRO scores using the EORTC 30 global QOL and function scales over the first postoperative year are shown in Figure 1. Physical, role, and social functioning scales reached a nadir at 3 months, which was significantly lower than preoperative values (p<0.05). In contrast, the global health scale, as well as emotional and cognitive function scales did not differ from preoperative to 3 months postoperatively (p=1.00). At 12 months postoperatively, function and global QOL scores did not differ significantly from baseline scores.

Figure 1.

EORTC 30 Global health status* and Function scales# by time

#A high score for a functional scale represents a high / healthy level of functioning

*A high score for the global health status / QOL represents a high QOL

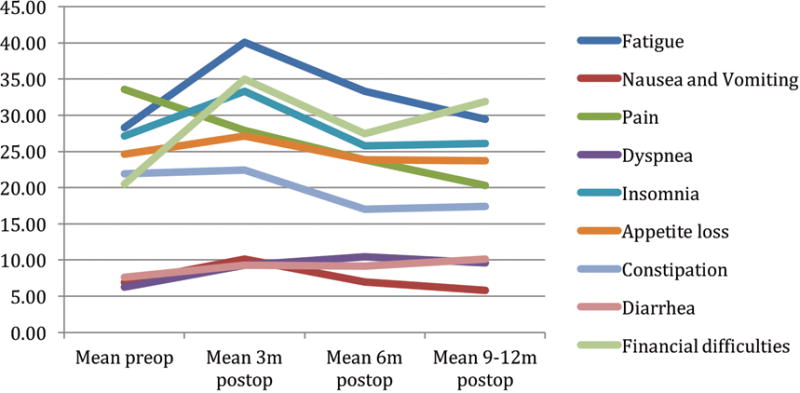

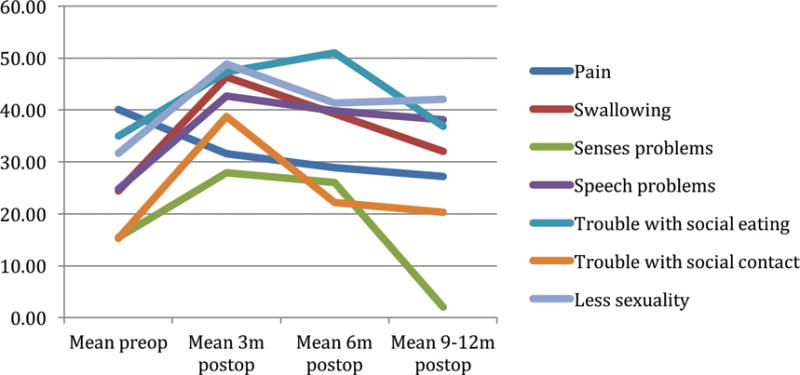

Many of the EORTC 30 and 35 symptom scale scores illustrated in figures 2 and 3 mirror the function scales. That is, at 3 months postoperatively, patients reported greater symptomatology than preoperative levels. Only 2 of 9 symptom scales were significantly lower at 3 months using the EORTC 30, whereas 12 of 18 were significantly lower using the disease specific head and neck EORTC 35 (p<.05). At 12 months postoperatively, all of EORTC 30 symptoms scales reached preoperative levels while five of EORTC 35 did not.

Figure 2.

EORTC 30 Symptom scales by time*

*A high score for a symptom scale / item represents a high level of symptomatology / problems

Figure 3.

EORTC 35 Symptom scales by time*

*A high score for a symptom scale / item represents a high level of symptomatology / problems

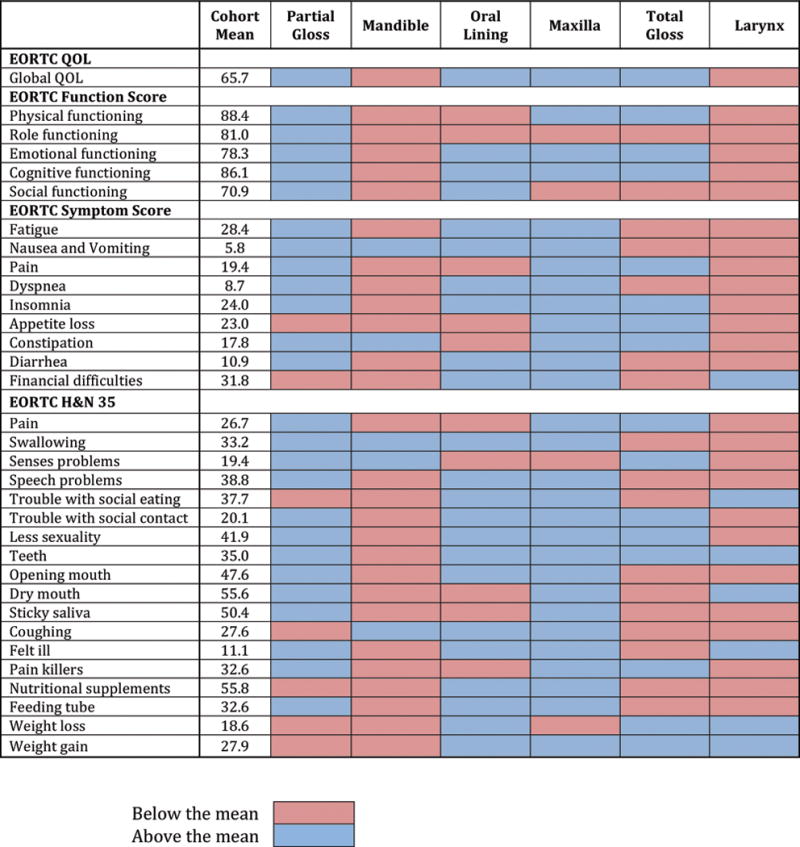

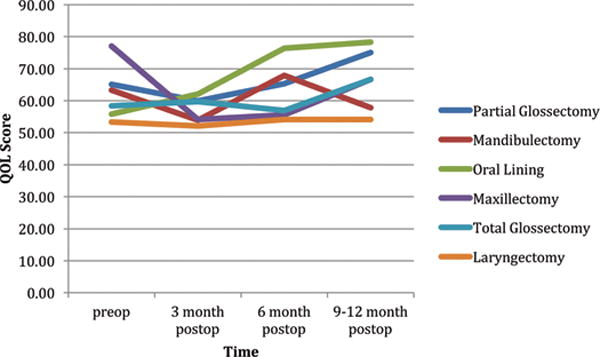

PROs by defect type for the EORTC 30 function and the EORTC 30 and 35 symptom scales are shown in Figure 4. At one year postoperatively maxillectomy, partial glossectomy, and oral lining defects had worse function and more symptoms in 4, 7, and 10 of 33 items, respectively. In contrast, mandibulectomy, laryngectomy, and total glossectomy had worse function and more symptoms in 28, 26, and 17 of 33 items, respectively. Patient reported global QOL from 6–12 months postoperatively was significantly greater for partial glossectomy and oral lining defects compared to laryngectomy (p<.05).(Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Heat map of PRO scores for each surgical defect compared with the cohort average at one year postoperatively.

Figure 5.

EORTC global QOL by anatomical surgical resection over time

* Global QOL from 6–12 months postoperatively was significantly greater for partial glossectomy and oral lining defects compared to laryngectomy (p<.05)

Discussion

In addition to providing optimal oncologic outcomes, surgical interventions should aim to reduce physical and psychological symptoms while maintaining or improving HR-QOL. The accurate assessment of postoperative HR-QOL after oncologic surgery with reconstruction for head and neck cancer patients provides an opportunity for plastic surgeons to transmit higher quality information to future patients. Better preoperative information about expectations is important because it may improve PROs.20 For example, in breast reconstruction, patient satisfaction with preoperative information was the strongest predictor of satisfaction with the overall outcome, stronger even than the method of reconstruction and whether or not complications had occurred.21 Lastly, measurement of HR-QOL outcomes can be used to highlight patients who are doing particularly poorly following surgery (e.g. longer than expected return to baseline function) for additional interventions such as speech, physical or occupational therapy.

The current prospectively followed cohort is representative of a variety of head and neck surgical defects (Tables 2). To our knowledge, no study has objectively measured HR-QOL associated with the commonly performed anatomical head and neck resections. This method of analysis was chosen since from a clinical perspective, flap selection appears intuitively less critical than the impact imparted by removal of a unique functional structure. For example, the same surgical defect (e.g. total glossectomy) could be reconstructed using a variety of flap types (e.g. ALT, radial forearm, rectus abdominis) depending upon the patient’s body habitus or surgeon preference. In support of the study hypothesis, the location of a surgical defect uniquely predicted HR-QOL. For example, when compared over 6–12 months postoperatively, patients undergoing laryngectomies had the lowest global QOL and these values were significantly lower than either oral lining or partial glossectomy defects (Figure 5). Furthermore, mandibulectomy, laryngectomy, and total glossectomy defects exhibited substantially more symptoms and worse function compared to other surgical defects at one year (Figure 4). These objective findings can be used by the oncologic team to inform patients about anticipated postoperative HR-QOL and functional recovery. Furthermore, preoperative teaching should be targeted specifically for each ablative procedure so that postoperative expectations can be adjusted appropriately.

Previous works have evaluated HR-QOL following head and neck cancer reconstruction in different ways including utilizing other PRO instruments. Using the EORTC 30&35, worse HR-QOL was associated with greater extent of mandible and floor of mouth resections; however, other common head and neck resections including laryngectomy and glossectomy were not evaluated.11 Alternatively, microsurgical versus pedicle flap reconstructions have been compared using the EORTC 30 and 35 or the University of Washington-QOL (UW-QOL) questionnaires, demonstrating superior outcomes with free flaps.12,22 The value added by the current analysis is that it includes a modern cohort of patients undergoing flap reconstructions analyzed in a more clinically intuitive and useful manner.

While there are exceptions, it should be communicated to patients that surgery negatively impacts HR-QOL in the early post-operative period (Figures 1, 2, and 3). At 3 months, the cohort reported significantly worse scores than preoperative levels in 17 of 33 EORTC 30 and 35 items (p<.05). Gradual improvements were generally seen by 1 year, with scores remaining below preoperative levels in only 5 of 33 EORTC 35 items (p<.05). Other studies have similarly reported a decrease in HR-QOL in the immediate postoperative period with improvement over time.12,23–26 Physical recovery from surgery, rehabilitation, adapting and coping mechanisms may explain patient progress. In light of these finding, it is important to consider the limited survival time for patients with stage II and III head and neck cancer who undergo major resection with reconstruction. Table 4 illustrates that over 25 percent of patients at 1 year and more than 50 percent at 2 years are not alive. These curtailed survival data likely reflect the large proportion of patients treated for recurrent or advanced disease at a quaternary cancer hospital so may not be broadly applicable to all patients. 27 However, in the interest of shared decision-making, patients and physicians should balance tradeoffs of HR-QOL with anticipated survivorship.

The EORTC 30 and 35 were chosen as the PRO instruments for this study based on their development methodology, robust psychometric properties and consistency across studies.28,29 However, investigators need to be aware of each questionnaires limitations. The value of condition specific, as opposed to generic measures, was highlighted in this study by the greater sensitivity of the EORTC 35 to detect clinical symptoms at 3 and 12 months compared with the EORTC 30. In addition, a review of head and neck PRO instruments found that they inadequately assess midface symptoms as well as facial appearance.30 Moreover, the EORTC 30 and 35 and UW-QOL were developed using classic test theory (CTT) rather than Rasch analysis. A weakness of questionnaires derived with CTT is that they can only be used for population level research. In contrast, because Rasch can provide information on interval as opposed to ordinal level change, it can be incorporated into clinical practice to track individual patient’s HR-QOL over time.31 The FACE-Q is a condition specific PRO instrument developed for aesthetic surgery using Rasch, with a module currently being developed for patients with head and neck cancer called FACE-Q oncology. This questionnaire intends to address some of the aforementioned deficiencies.32

Though the study provides important insights, it has limitations. As previously mentioned, while psychometrically valid questionnaires were used, some potential symptoms may not have been evaluated. Additionally, longer follow-up, would enhance understanding of how HR-QOL evolves over time. While the current sample size compares favorably to recent literature on PROs in head and neck surgery, a larger sample size would improve generalizability, decrease both measured and unmeasured biases amongst groups as well as allow for relevant subgroup analyses such as the impact of flap type on outcome.

Conclusion

Postoperative HR-QOL is associated with the anatomic location of the head and neck surgical resection. Preoperative teaching should be targeted for each ablative defect with postoperative expectations adjusted accordingly. Because surgery negatively impacts HR-QOL in the immediate post-operative period with a prolonged return to baseline levels, the limited survivorship of these patients needs to be reviewed during preoperative consultation.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure

No specific funding was used for this research

References

- 1.Momeni A, Kim RY, Kattan A, Tennefoss J, Lee TH, Lee GK. The effect of preoperative radiotherapy on complication rate after microsurgical head and neck reconstruction. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2011;64:1454–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh B, Cordeiro PG, Santamaria E, Shaha AR, Pfister DG, Shah JP. Factors associated with complications in microvascular reconstruction of head and neck defects. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1999;103:403–11. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199902000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suh JD, Sercarz JA, Abemayor E, et al. Analysis of outcome and complications in 400 cases of microvascular head and neck reconstruction. Archives of otolaryngology–head & neck surgery. 2004;130:962–6. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.8.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urken ML. Advances in head and neck reconstruction. The Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1473–6. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200309000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hidalgo DA, Pusic AL. Free-flap mandibular reconstruction: a 10-year follow-up study. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2002;110:438–49. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200208000-00010. discussion 50-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dassonville O, Poissonnet G, Chamorey E, et al. Head and neck reconstruction with free flaps: a report on 213 cases. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies. 2008;265:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s00405-007-0410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dean NR, Wax MK, Virgin FW, Magnuson JS, Carroll WR, Rosenthal EL. Free flap reconstruction of lateral mandibular defects: indications and outcomes. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012;146:547–52. doi: 10.1177/0194599811430897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozec A, Poissonnet G, Chamorey E, et al. Radical ablative surgery and radial forearm free flap (RFFF) reconstruction for patients with oral or oropharyngeal cancer: postoperative outcomes and oncologic and functional results. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2009;129:681–7. doi: 10.1080/00016480802369260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urken ML, Weinberg H, Buchbinder D, et al. Microvascular free flaps in head and neck reconstruction. Report of 200 cases and review of complications. Archives of otolaryngology–head & neck surgery. 1994;120:633–40. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1994.01880300047007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Disa JJ, Pusic AL, Hidalgo DH, Cordeiro PG. Simplifying microvascular head and neck reconstruction: a rational approach to donor site selection. Annals of plastic surgery. 2001;47:385–9. doi: 10.1097/00000637-200110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang QG, Shi S, Li M, Zhang X, Liu FY, Sun CF. Free flap reconstruction versus non-free flap reconstruction in treating elderly patients with advanced oral cancer. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2014;72:1420–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villaret AB, Cappiello J, Piazza C, Pedruzzi B, Nicolai P. Quality of life in patients treated for cancer of the oral cavity requiring reconstruction: a prospective study. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2008;28:120–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hikosaka M, Ochiai H, Fujii M, et al. QOL after head and neck reconstruction: evaluation of Japanese patients using SF-36 and GOHAI. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2011;38:730–4. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Netscher DT, Meade RA, Goodman CM, Alford EL, Stewart MG. Quality of life and disease-specific functional status following microvascular reconstruction for advanced (T3 and T4) oropharyngeal cancers. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2000;105:1628–34. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200004050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markkanen-Leppanen M, Makitie AA, Haapanen ML, Suominen E, Asko-Seljavaara S. Quality of life after free-flap reconstruction in patients with oral and pharyngeal cancer. Head & neck. 2006;28:210–6. doi: 10.1002/hed.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85:365–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bjordal K, de Graeff A, Fayers PM, et al. A 12 country field study of the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3.0) and the head and neck cancer specific module (EORTC QLQ-H&N35) in head and neck patients. EORTC Quality of Life Group. European journal of cancer. 2000;36:1796–807. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hjermstad MJ, Fossa SD, Bjordal K, Kaasa S. Test/retest study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality-of-Life Questionnaire. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1995;13:1249–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.5.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group . In: EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual. 3rd. EORTC, editor. Burssels: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Snell L, et al. Measuring and managing patient expectations for breast reconstruction: impact on quality of life and patient satisfaction. Expert review of pharmacoeconomics & outcomes research. 2012;12:149–58. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ho AL, Klassen AF, Cano S, Scott AM, Pusic AL. Optimizing patient-centered care in breast reconstruction: the importance of preoperative information and patient-physician communication. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013;132:212e–20e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829586fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozec A, Poissonnet G, Chamorey E, et al. Free-flap head and neck reconstruction and quality of life: a 2-year prospective study. The Laryngoscope. 2008;118:874–80. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e3181644abd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogers SN, Humphris G, Lowe D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. The impact of surgery for oral cancer on quality of life as measured by the Medical Outcomes Short Form 36. Oral oncology. 1998;34:171–9. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(97)00069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rogers SN, Lowe D, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. The University of Washington head and neck cancer measure as a predictor of outcome following primary surgery for oral cancer. Head & neck. 1999;21:394–401. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199908)21:5<394::aid-hed3>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers SN, Lowe D, Fisher SE, Brown JS, Vaughan ED. Health-related quality of life and clinical function after primary surgery for oral cancer. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2002;40:11–8. doi: 10.1054/bjom.2001.0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Graeff A, de Leeuw JR, Ros WJ, Hordijk GJ, Blijham GH, Winnubst JA. A prospective study on quality of life of patients with cancer of the oral cavity or oropharynx treated with surgery with or without radiotherapy. Oral oncology. 1999;35:27–32. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(98)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salvatori P, Paradisi S, Calabrese L, et al. Patients’ survival after free flap reconstructive surgery of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective multicentre study. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2014;34:99–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djan R, Penington A. A systematic review of questionnaires to measure the impact of appearance on quality of life for head and neck cancer patients. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2013;66:647–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pusic A, Liu JC, Chen CM, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures in head and neck cancer surgery. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2007;136:525–35. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Albornoz CR, Pusic AL, Reavey P, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life outcomes in head and neck reconstruction. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2013;40:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cano SJ, Klassen A, Pusic AL. The science behind quality-of-life measurement: a primer for plastic surgeons. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009;123:98e–106e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31819565c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Schwitzer JA, Scott AM, Pusic AL. FACE-Q scales for health-related quality of life, early life impact, satisfaction with outcomes, and decision to have treatment: development and validation. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015;135:375–86. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]