Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Recent health care reforms aim to increase patient access, reduce costs, and improve health care quality as payers turn to payment reform for greater value. Cardiologists need to understand emerging payment models to succeed in the evolving payment landscape. We review existing payment and delivery reforms that affect cardiologists, present 4 emerging examples, and consider their implications for clinical practice.

OBSERVATIONS

Public and commercial payers have recently implemented payment reforms and new models are evolving. Most cardiology models are modified fee-for-service or address procedural or episodic care, but population models are also emerging. Although there is widespread agreement that payment reform is needed, existing programs have significant limitations and the adoption ofnew programs has been slow. New payment reforms address some of these problems, but many details remain undefined.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Early payment reforms were voluntary and cardiologists’ participation is variable. However, conventional fee-for-service will become less viable, and enrollment in new payment models will be unavoidable. Early participation in new payment models will allow clinicians to develop expertise in new care pathways during a period of relatively lower risk.

The US health care system needs to address an unsustainable trajectory of high costs and middling outcomes. The United States has the highest per capita health expenditures in the world but ranks last among developed nations in care quality, efficiency, and equity.1,2 Recent government health care reforms, including the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Re-authorization Act (MACRA), aim to improve value.3,4

The fee-for-service (FFS) payment model contributes to escalating healthcare expenditures and inconsistent quality.5–8 Most policymakers believe payment reform is necessary to improve care, and public and private payers are experimenting with a range of payment models that better align payments with value. This review explores existing and emerging payment and delivery reforms that affect cardiologists and considers their definitions and implications for clinical practice (eAppendix in the Supplement). Four examples are described, including a commercial incentive program, an episode payment model, a physician-led accountable care organization (ACO), and a health system participating in multiple models.

MACRA

The MACRA legislation represents the most significant revision of federal health care payment policy in decades.4 Before MACRA, Medicare FFS payments were adjusted based on the sustainable growth rate formula, in which FFS payment updates were tiedto the economy’s state.9,10 Because Medicare spending consistently exceeded economic growth, the sustainable growth rate triggered annual reimbursement cuts. Congress deferred these cuts, but by 2015, compounded deferrals reached 21% and caused uncertainty.10 MACRA repealed the sustainable growth rate and established a new incentive program.4

Payment Models Framework

Payers are moving away from the FFS payment model. The Department of Health and Human Services announced its goal to shift 30% of Medicare payments to alternative payment models (APMs) by 2016 and 50% by 2018, which was met in early 2016, nearly a year ahead of schedule.11,12 Commercial payers also aim to tie 75% of payment to value by 2020.13

The Department of Health and Human Services groups these models into 4 categories, ranging from FFS (category 1) to population-based payment (category 4) (Table 1).14 Payment reforms may affect cardiologists directly—as with the Physician Quality Reporting System 15 and Meaningful Use16—or indirectly, as with the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program.17 We focus on reforms directed to cardiologists and offer examples in each category.

Table 1.

Department of Health and Human Services Payment Taxonomy Framework

| Characteristic | Category 1: FFS Without Links to Quality |

Category 2: FFS With Links to Quality |

Category 3: APMs Built on FFS Architecture |

Category 4: Population and Personal Payments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Service-based reimbursement | A portion of reimbursement tied to quality and efficiency outcomes | Payments remain tied to individual service volume; increased accountability for quality and efficiency; incentives for population health management | Reimbursement based on attributed patient population over a defined period; accountability for cost and quality |

| Examples | FFS | PQRS; value-based payment modifier; hospital readmissions penalty; MIPS | Medicare Shared Savings ACOs (tracks 1, 2a, and 3a)b; BPCI, CCJR bundled payments; AMI EPMa; medical homes; Next Generation ACOa,b; Comprehensive Primary Care Plusa | Pioneer ACO (years 3–5)b |

Abbreviations: ACOs, accountable care organizations; AMI EPM, Acute Myocardial Infarction Episode Payment Model; APMs, alternative payment models; BPCI, Bundled Payments for Care Improvement; CCJR, Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement; FFS, fee-for-service; MIPS, Merit-Based Incentive Payment System; PQRS, Physician Quality Reporting System.

These models qualify for the APM pathway in the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act proposed rule.

Multiple variations of ACOs exist, allowing each to establish a leadership and administrative infrastructure and to include gain sharing only or may have downside risk.

Category 1 (FFS Payment Model)

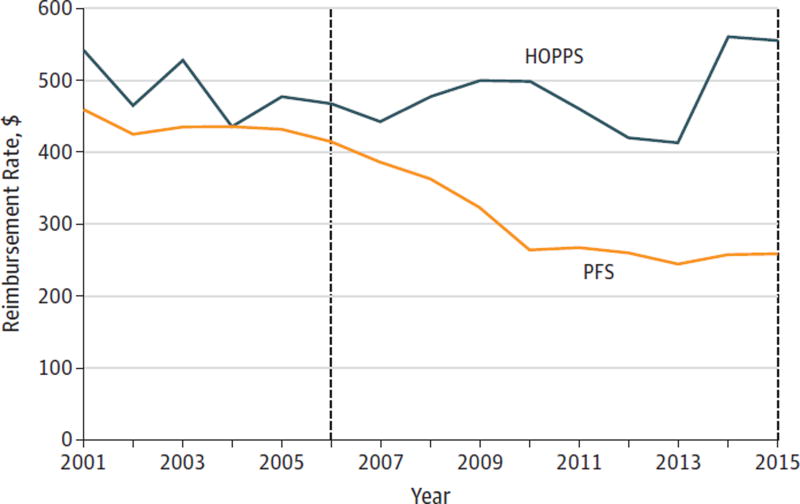

Fee-for-service has been the predominant payment model for decades, but future developments will make it undesirable. Medicare FFS reimbursements have decreased for many cardiovascular services on an inflation-adjusted basis (Figure). They will further erode because scheduled fee increases will not keep pace with historical inflation rates.4 By contrast, hospital-based outpatient reimbursement rates for echo and nuclear cardiology services have recently increased, resulting in a large reimbursement difference between clinic- and hospital-based outpatient cardiology practices. The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 recognizes this disparity and imposes site-neutral payments on new hospital outpatient departments.18,19

Figure. Combined Medicare Reimbursement for Echo and Nuclear Imaging in Office and Hospital Settings (2001–2015).

Reimbursement rates were adjusted for inflation based on Consumer Price Indices taken from the Bureau of Labor Statistics: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/cpi_dr.html. The first vertical line (2006) represents the Deficit Reduction Act of 2006. The second vertical line (2015) represents the passage of the Medicare Access and Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act. PFS indicates physician fee schedule; HOPPS, Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System.

Commercial payers are also constraining FFS payments. Employers are under pressure to decrease health care expenditures, and people who independently purchase health insurance report the cost as an important factor in plan selection.20 Because the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act defines minimal coverage standards, insurers primarily compete on cost. Consequently, commercial insurers have constructed narrow networks of clinicians willing to accept discounted FFS fees.21 An estimated 39% of networks, 55% of which were in large urban markets, were considered narrow in 2015, and these consistently had lower premiums than broad network plans.

Category 2(FFS With Links to Quality)

MACRA establishes 2 alternative pathways: the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and the APM program. Most cardiologists are expected to participate in MIPS (eFigure 1 in the Supplement).22 The Merit-Based Incentive Payment System combines several existing pay-for-performance programs—Physician Quality Reporting System, Meaningful Use, and Value-Based Modifier—and adds 1 focused on clinical practice improvement. In this combined program, practices will be assigned a composite score composed of 4 categories: quality (50%), resource use (10%), advancing care information (Meaningful Use) (25%), and clinical practice improvement (15%). The relative weighting of these categories will change over time.23

Base physician fee rates will increase by 0.5% per year through 2019 but then will not increase until 2026. In 2017, physicians’ composite performance will be calculated and used to adjust FFS payments in 2019. The adjustment magnitude will increase from ±5% in 2019 (performance year 2017) to ±9% in 2022 (performance year 2020) (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Category 3 (APMs Built on an FFS Architecture)

Bundled payments are an example of a category 3 payment model. Clinicians receive a lump sum payment for a group of services related to a procedure or care episode instead of individual payments for encounters, services, tests, and procedures. Table 2 and Table 3 provide cardiac examples of each type. Bundled payments aim to reward clinicians who offer efficient, high-quality care. Payers are guaranteed cost-savings because bundled payments are set at a discount to expected FFS payments. Clinicians may keep a portion of the savings if services cost less than the bundled payment, but may lose money if services cost more.

Table 2.

Applications of Cardiology-Relevant Procedure Bundles From Public and Private Payers

| Characteristic | Medicare Acute Care Episode |

Cleveland Clinic and Boeing/Lowe’s/Walmart |

Integrated Healthcare Association |

Medicare Bundled Payments for Care Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Valve surgery | Valve surgery | Cardiac catheterization | PCI, pacemaker, ICD, valve surgery, CABG |

| Dates | Demonstration conducted from 2009–2012 | Partnerships with Cleveland Clinic established in 2010 (Lowe’s) and 2012 (Boeing and Walmart) | Pilot launched in 2012 | Program announced first participants in January 2013 and began in April 2013 |

| Patient cohort | Medicare beneficiaries | Covered Boeing, Lowe’s, or Walmart employees | Aetna, Blue Shield of California, and CIGNA PPO beneficiaries | Medicare beneficiaries |

| Duration | 90 d after discharge | Variable duration | 30 d after procedure | Variable duration: 30, 60, or 90 d after discharge |

| Services covered | All related Medicare Part A and Part B services, including any readmissions | All services and medications related to surgery, including medically necessary services delivered in Cleveland after discharge, plus travel and lodging for the employee and a relative | All related facility charges, imaging services, and professional fees, including those due to complications | Clinicians choose 1 of 4 options, which determine the scope and duration of the bundle. These types include (1) hospital stay, (2) hospital stay and postacute care, (3) postacute care only, or (4) hospital stay paid prospectively |

| Payment | Prospective payment with both gainsharing and downside risk | Prospective payment with both gainsharing and downside risk | Prospective payment with both gainsharing and downside risk | Retrospective payment in models 1, 2, and 3. Prospective payment in model 4. Both nonrisk-bearing (gainsharing only) and risk bearing (gain sharing and downside risk) options are possible for all models |

Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery by pass grafting; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPO, preferred provider organization.

Table 3.

Examples of HF Episode Bundles

| Characteristic | Arkansas Healthcare Payment Improvement Initiative |

Medicare Bundled Payments for Care Improvementa |

|---|---|---|

| Launch date | July 2012 | April 2013 |

| Patient cohort | Arkansas BCBS, QualChoice, and Medicaid beneficiaries | Medicare beneficiaries |

| Trigger | HF hospitalization (eligible DRG 291-3) | HF hospitalization (eligible DRG 291-3) |

| Duration | Episode begins on day of inpatient admission and ends 30 d following discharge | Duration depends on model selected, ranging from inpatient stay only to 30, 60, or 90 d following discharge |

| Services covered | All HF-related inpatient, emergency department, and outpatient costs | Clinicians choose 1of 4 bundle types, which determine the services and length of care covered. These types include (1) hospital stay only, (2) hospital stay and postacute care, (3) postacute care only, or (4) hospital stay paid prospectively |

| Payment | FFS service payments billed and received as normal. At conclusion of period, clinician either receives incentive payment or must issue a refund. 2-Sided model with risk bearing and gainsharing split equally between payer and hospital. Risk/gain cannot exceed 10% of allowable claims | Models 1, 2, and 3 make retrospective payments. Model 1 pays a discounted rate for Part A services. Models 2 and 3 pay normal rates but are subject to postepisode reconciliation. Model 4 provides a discounted prospective payment. For all models, clinicians can elect to participate in either phase 1, which is not financially risk-bearing, or phase 2, which is risk-bearing |

Abbreviations: BCBS, Blue Cross Blue Shield; DRG, diagnosis-related group; FFS, fee-for-service; HF, heart failure.

Medicare episode bundles also exist for acute myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, cardiac arrhythmia, and chest pain.24

One Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services version of this model is the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative.25,26 It offers protection from gainsharing rules and improves clinician alignment (eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Participation has been limited because existing models have high upfront costs, reduce reimbursement, add administrative complexity, and introduce conflicting incentives when some patients are in bundles while others remain in FFS. Procedural bundles may be easier to manage than episode bundles, particularly for bundles that cover longer durations. To boost participation, the Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services has established a “facilitator convener” program to provide administrative and technical assistance to participating clinicians.27 Participating Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative practices often enter these bundled arrangements with goals to develop the knowledge, skills, and infrastructure needed for success before bundles become mandatory.

Most current ACOs are also category 3 models. Accountable care organizations are delivery and payment reforms that share accountability for care cost and quality across the health care system. Medicare defines ACOs as “groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health-care clinicians, who come together voluntarily to give coordinated high quality care.”28 Participation is voluntary for patients and clinicians. In Medicare Shared Savings ACO models, clinicians bill insurers on an FFS basis and outcomes and expenses are compared with regional and national benchmarks. Accountable care organization clinicians who successfully improve quality and reduce costs are eligible to receive bonus payments and shared savings. In ACO models that accept financial risk, ACO clinicians who exceed spending benchmarks may owe money back.

Accountable care organizations have steadily increased since 2010, from 64 at the start of 2011 to 838 in 2016.29 Public and commercial versions exist and they can be health system or physician administered. Early experience with ACOs has been mixed because few have successfully earned performance payments30 and nearly half of those that did had below-average quality performance.31 In 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced 18 new Next Generation ACOs that will incorporate “preferred clinicians” to encourage value-driven primary care physician (PCP)–specialist relationships.29,31

Category 4(Population-Based Payments)

While the category 2 and category 3 models improve on FFS by incorporating incentives for enhanced value, they remain linked to individual services. For example, bundled payments constrain spending within an episode of care but do not include incentives to limit episode frequency. Accountable care organizations, including most Medicare Shared Savings Programs, continue to pay clinicians on an FFS basis. By decoupling payments from specific services, population models allow clinicians to determine the most effective means of improving health.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services intends to shift clinicians toward population-based payment models that link delivery and payment reforms (categories 3 and 4). The MACRA APM pathway includes category 3 and 4 models, and practices are required to achieve a minimum revenue or patient count threshold to be eligible. MACRA APM participants are exempt from MIPS reporting requirements, receive a 5% bonus through 2024, and have higher base fee rate increases after 2026.23 Although many practices prefer the APM pathway to MIPS, only 10% of Medicare clinicians are expected to qualify in the first year. Only a few APMs qualify for the pathway; of these, only selected ACO models that accept financial risk and the recently announced Acute Myocardial Infarction and Coronary Artery Bypass Graft bundles32 are directly pertinent to cardiologists.

Category 4 models are better established in primary care than in cardiology and often combine delivery and payment reforms. The Patient-Centered Medical Home(PCMH) is an enhanced primary care model that emphasizes comprehensive, patient-centered, coordinated, accessible, and high-quality care.33,34 Public and commercial PCMH models exist, each with distinct accreditation programs and payment models.

Patient-Centered Medical Home clinicians are increasingly paid through APMs. Some primary care practices receive payments on top of FFS to support enhanced care coordination or other high-value services (category 3). Others are paid a fixed per patient per month amount for all primary care services instead of FFS payments for individual services (category 4). Additionally, many PCMHs receive bonus payments tied to cost and quality performance and have a direct financial stake in managing cardiology services.33–35

To enhance PCP and specialty collaboration, the American College of Physicians developed the PCMH Neighbor36 concept and partnered with the National Committee for Quality Assurance to create the Patient-Centered Specialty Practice Program.37 These models extend the PCMH framework to specialty practices.38 Recognized Patient-Centered Specialty Practice Program practices agree to a bidirectional “care compact” that guides communication between clinicians and with patients.36,39 These models are developing and few cardiology practices currently participate, in part because there is no consistent payment model to support them.

In the future, some ACO types will move away from FFS payments entirely. Instead, they will receive population-based payments (category 4). This payment and delivery reform model is in-tended for ACOs with advanced care coordination capabilities across care settings.29,31,40,41

4 Examples of New Payment Models That Affect Cardiology

Payment models can be challenging to conceptualize, and we present 4 examples to illustrate different approaches to improving value. These include a commercial incentive program, an episode payment model, a physician-led ACO, and a health system that participates in multiple models.

Physician Group Incentive Program (Category 2 Model)

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan created the Physician Group Incentive Program (PGIP) in 2005 to shift clinicians toward a more collaborative, cost-conscious, and preventive culture.42 The program supports clinical registries and provides periodic performance reporting while linking primary care and specialty payment to population-level outcomes. Approximately 69% of primary care and 82% of cardiology practices in Michigan currently participate.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan–designated PCMHs are eligible to receive a value-based reimbursement (VBR) of up to 130% of the standard fee schedule for evaluation and management codes. Specialists are eligible for a VBR of up to 110% of the standard fee schedule on most procedure codes. Cardiology VBR is tied to a weighted contribution of several population-level measures, including cost (15%), cost difference from the prior year (10%), an “efficiency” score (30%), a global quality score (30%), and the cost of cardiac diagnostic procedures (15%). To fund the program, statewide physician fees were frozen in 2009; all subsequent fee increases must come through incentive payments.43

The Physician Group Incentive Program is novel in many respects. It shifts the emphasis away from burdensome pre-authorization requirements and toward shared accountability for outcomes and costs across a clinician community. Performance feedback comes from 1of more than 40 physician organizations, and discussions about use and quality occur among peers. Physician organizations nominate specialists to be eligible for VBR, and specialty VBR is based on population-level performance, not practice-specific performance, which means nominated specialists share incentives with their clinical colleagues. A recent analysis showed that PGIP practices had higher performance in 11 of 14 quality measures and 1.1% lower total spending than non-PGIP practices.44

Acute Myocardial Infarction Episode Payment Model (Category3)

Building on promising results from prior bundled payment pilots,45–48 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced the first mandatory APM for cardiac conditions in July2016.49 The acute myocardial infarction bundled payment includes hospitalization and all Medicare services in the 90 days following discharge. The model distinguishes between medical and interventional management and accounts for patient complexity (Table 4).

Table 4.

Core Features of the Mandatory Acute Myocardial Infarction Episode Payment Model

| Characteristic | Features | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Condition | Acute myocardial infarction: medical management (MS-DRG 280- 282); interventional management (MS-DRG 246–251) | Intracardiac procedures and CABG are excluded |

| Participants | All hospitals located in 98 randomly selected metropolitan statistical areas | Selected rural hospitals and current BPCI participants are excluded |

| Payment model | Bundled payment: admission through 90 d after discharge; 2-sided risk model; and retrospective reconciliation | All inpatient and outpatient Medicare charges are included |

| Bundle amount | Payment determined by medical vs interventional management; blend of own historical spending and regional spending; and quality performance | Minimum quality score required for payment. Payment shifts toward regionally determined rates over time |

| Amount at risk | Year 1 gain: 5% and loss: none; Year 2 gain: 5% and loss: 5%; Year 3 gain: 10% and loss: 10%; Year 4 gain: 20% and loss: 20%; Year 5 gain: 20% and loss: 20% | Financial risk is limited for selected rural hospitals |

| Quality metrics | Composite quality score: hospital 30 d, all-cause risk-standardized mortality; excess days in acute care after hospitalization; Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Clinicians and Systems Survey; and voluntary hybrid hospital 30-d, all-cause risk-standardized mortality rate | Each measure requires a minimum No. of cases |

Abbreviations: BPCI, Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MS-DRG, Medicare Severity Diagnosis-Related Group.

This model takes a “virtual bundling” approach (eg, retrospective reconciliation).50 The hospital and participating clinicians are paid individual FFS payments at standard Medicare payment rates, but actual expenditures are compared with the target price at the end of each performance year. The target payment amount is determined by a combination of each hospital’s historical charges and average regional charges; the target payment is then adjusted for quality performance. Hospitals with charges below the target price may receive incentive payments, but those with charges above may owe money back. Hospitals may align participating clinicians through gain-sharing agreements that distribute gains and losses.

Strong clinical leadership and substantial investments are needed to successfully redesign care processes, improve quality, and decrease costs.45 Financial risk increases when hospitals have a low volume of care episodes and a fair distribution of gains and losses between the hospital and independent clinicians may prove contentious.48A recent analysis suggests that the bundle will have small effects for most hospitals, but those at the extremes could experience large gains or losses.51

MD Value Care (Category 3 Model)

MD Value Care was established as a physician-led ACO in 2014, and participants expressed a desire to remain independent and succeed in a rapidly changing payment landscape. The ACO participates in Medicare’s Shared Savings Program and serves 14 000 beneficiaries. It is composed of 5 PCP groups and 15 specialty practices, including 1 cardiology group in the greater Richmond, Virginia, area. The ACO requires all participants to maintain certified electronic health records. Any shared savings are invested in infrastructure improvements or shared between participating physicians according to a predetermined formula.

In physician-led ACOs, the greatest savings opportunities may come from shifting testing and treatment to low-cost settings and avoiding emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Thus, MD Value Care participants have focused on improving communication and coordination, enhancing access to outpatient care, and formalizing comanagement agreements through care compacts. MD Value Care cardiologists have not experienced a negative effect on patient referrals or testing volume and report that ACO participation has expanded their referral base while allowing them to gain experience with APMs (oral communication; Ann Honeycutt, executive director of Virginia Cardiovascular Specialists; July 21, 2016).

In 2014—the only year performance data are available for MD Value Care—the ACO met or exceeded the average ACO performance for most quality measures but accrued 1.8%greater costs than its benchmark. Consequently, it did not receive shared savings in its first year.52 While large numbers of both physician- and hospitalled ACOs have yet to reach savings benchmarks, more physicianled ACOs have succeeded.53

Henry Ford Physician Network (Multiple Models)

The Henry Ford Physician Network(HFPN) was launched as a commercial ACO (category 3) in 2010 in response to downward pressure on FFS reimbursement and as a strategic initiative to develop value-oriented competencies.54 The HFPN also participates in PGIP (category2) and has been selected to participate in Medicare’s Next Generation ACO program (category 4).29 The network comprises 1200 employed physicians in the Henry Ford Medical Group and the Henry Ford Hospital and serves 40 000 to 50 000 covered patients. Unlike earlier Medicare ACO programs, the Next Generation ACO will allow the HFPN to reduce copays for ACO-participating specialists.

Many of the Henry Ford value strategies are administratively driven. To improve system performance, the HFPN has established care registries, implemented case management for frequent users, incorporated electronic health record decision support, and established analytic capabilities to identify and address unwarranted care variations. To simplify the complexity of simultaneous participation in multiple programs (ie, FFS modifiers, PGIP, and the commercial ACO), HFPN has prioritized several performance metrics and incorporated them into physician compensation contracts. Physicians in HFPN are eligible for a 15% incentive tied to productivity, patient satisfaction, and quality metrics. The HFPN has reduced its read-mission rate by approximately 10% and achieved savings for 3 consecutive years within its commercial ACO.

Limitations of Existing and Emerging Payment Models

Most policymakers agree that payment reform is needed, but existing models have important limitations. Many cardiologists are unfamiliar with these programs, and bonus payments available in current federal programs may not offset the burden of reporting.55 Many physicians report that claims-based metrics are unreliable, too general, and delivered too infrequently or too late to be actionable. Within MIPS, proposed process-oriented quality performance measures may not be appropriate for cardiologists who heavily emphasize imaging or interventions.56 Many hospitals view bundled payments as discounted FFS rather than an opportunity for improved value or gainsharing. While payment models have proliferated, they have not been coordinated across payers, a factor that muddles incentives and increases inefficiency.

Primary care physicians increasingly receive feedback on care provided by cardiologists they refer to, but feedback on care quality is limited (if any is offered). These data are intended to incentivize PCPs to refer to lower-cost cardiologists, but PCPs often lack the data necessary to assess value. Further, many PCPs have limited specialty referral options owing to geographic or market factors, or because they are constrained by organizational or insurance considerations. Cardiologists themselves rarely receive actionable feedback on how they might improve.

Payment reform may undermine collaboration if it is perceived as a zero-sum game. Incentives are misaligned when PCPs are paid through APMs while cardiologists remain in FFS. In this scenario, cardiologists lack financial incentives to change. Within ACOs, cardiologists may resist substantial practice changes if shared savings in-adequately offset decreased revenues.57 At the same time, specialists who control high-cost testing and interventions may be best positioned to improve value.

Employed cardiologists are often unaware of their APM (or even ACO)participation and performance feedback often goes to the employer, not the cardiologist. They may not perceive changes to their operations or practice if these changes are administratively driven. By contrast, participants in physician-led ACOs may be more engaged in practice improvement because they are directly responsible for operations. Outside of ACOs, the PGIP program is one of the few commercial programs that engages cardiologists in population health, but individual clinicians have little control over population-level outcomes.

Practice Implications

Falling Medicare and commercial FFS payments, the large Medicare FFS payment gradient for imaging services, and the administrative complexity and financial risk of emerging payment models have accelerated hospital acquisitions of cardiology practices. A 2012 survey of 2500 cardiology practices saw hospital ownership triple from 8% to 24% between 2007 to 2012.58 A 2012 survey among hospital administrators found that 40% acquired or considered acquiring a cardiology practice, and 46% reported that 1 or more cardiology practices were already integrated within their organization.59 By 2013, 53% of cardiology practices reported being fully owned and employed by a hospital, and an additional 25% indicated they were exploring hospital integration.30,60 A 2016 search of 17 855 American College of Cardiology physician members revealed that at least 67% are employed by health systems.

Alternative payment models exist on a spectrum of increasing complexity and financial risk. No single APM will work in every care setting or geographical location. A critical factor in APM participation is how practices are able to administratively manage complex payment structures and assume financial risk. The proportion of revenue derived from APMs must reach a minimum threshold to justify the significant staffing, operational, and administrative changes required for success.61,62 Consequently, many independent practices will find category 2 models more feasible, while integrated delivery networks, health systems, and ACOs may more readily participate in more advanced APMs (categories 3 and 4).

Conclusions

The US health care system is in a time of historic change. As the FFS model becomes less viable, participation in APMs will be unavoidable.12,63 Cardiologists must understand these emerging models and lead in their development to ensure that they are clinically driven, patient-centered, and avoid unintended consequences such as restricted access to services or a provision of un-needed care.

The FFS payment model has often generated perverse incentives, and existing and emerging payment models aim to shift the emphasis from volume to value. Early models have not performed as well as hoped. They have imposed substantial administrative burdens, have not been adequately transparent, and have often not delivered clear incentives at the physician level. New approaches are needed that encourage closer collaboration and coordination across the health system.

Patients are best served when they have continued access to a team of care clinicians with mutually aligned care processes grounded in evidence-based best practice and shared decision making. Ineffective and inefficient care results when PCPs and specialists have differing views on appropriate testing and treatment. To succeed in this new landscape, PCPs and cardiologists need near real-time data on quality and cost performance, and they must closely coordinate care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was funded by the Merkin Family Foundation (Northridge, California) and by grant 1 R01 HL113550 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Additional Contributions: We thank all of the individuals who were interviewed for this project, and especially the leadership of MD Value Care, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, and the Henry Ford Provider Network for sharing their experience and data with us.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Farmer and Ms Darling had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Farmer, Darling, George, Hagan, McClellan.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Farmer, Darling, George.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Farmer, Darling, Casale, Hagan, McClellan.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Darling, George, Casale, Hagan, McClellan.

Study supervision: Farmer, McClellan.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for the Disclosure of Potential Conflict of Interest, and Dr Darling reports grants from the Richard Merkin Family Foundation during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The Merkin Family Foundation and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Davis K, Stremikis K, Squires D, Schoen C, The Commonwealth Fund [Accessed January 27, 2016];Mirror, mirror on the wall: how the performance of the US health care system compares internationally. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/fund-report/2014/jun/1755_davis_mirror_mirror_2014.pdf. Published June 2014.

- 2.The World Bank. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Health expenditure, total (% of GDP) http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS.

- 3.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 22, 2016];Affordable Care Act website. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/American-Indian-Alaska-Native/AIAN/Affordable_Care_Act.html. Updated July 31, 2015.

- 4. [Accessed January 27, 2016];H.R.2—Medicare access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015. Congress.Gov website. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2/text.

- 5.Miller HD. From volume to value: better ways to pay for health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(5):1418–1428. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolf SH, Aron L, National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. US health in international perspective: shorter lives, poorer health [Accessed January 28, 2016];Panel on understanding cross-national health differences among high-income countries. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13497/us-health-in-international-perspective-shorter-lives-poorer-health. Published January 9, 2013.

- 7.Conrad DA, Grembowski D, Hernandez SE, Lau B, Marcus-Smith M. Emerging lessons from regional and state innovation in value-based payment reform: balancing collaboration and disruptive innovation. Milbank Q. 2014;92(3):568–623. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Commission on Physician Payment Reform. [Accessed January 28, 2016];Report of the National Commission on Physician Payment Reform. http://physicianpaymentcommission. org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/physician_payment_report.pdf. Published March 2013.

- 9.US Government Publishing Office. [Accessed July 18, 2016];Public law 105-33: Balanced Budget Act of 1997. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-105publ33/content-detail.html.

- 10.Wynne B. May the era of Medicare's doc fix (1997–2015) rest in peace: now what? [Accessed July 18, 2016];Health Affairs Blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2015/04/14/may-the-era-of-medicares-doc-fix-1997-2015-rest-in-peace-now-what/. Published April 14, 2015.

- 11.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed July 21, 2016];HHS reaches goal oftying 30percent of Medicare payments to quality ahead of schedule. http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2016/03/03/hhs-reaches-goal-tying-30-percent-medicare-payments-quality-ahead-schedule.html. Published March 3, 2016.

- 12.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed July 21, 2016];Better, smarter, healthier: in historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Published January 26, 2015.

- 13.Evans M. [Accessed July 22, 2016];Major providers, insurers plan aggressive push to new payment models. Modern Healthcare. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20150128/NEWS/301289934. Published January 28, 2015.

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 22, 2016];Better care. smarter spending. healthier people: paying providers for value, not volume. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-01-26-3.html. Published January 26, 2015.

- 15.Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services. [Accessed August 22, 2016];Physician quality reporting system. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/index.html. Updated August 8, 2016.

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 21, 2016];Electronic health records (EHR) incentive programs. https://www.cms.gov/regulations-and-guidance/legislation/ehrincentiveprograms/. Updated September 2, 2016.

- 17.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 21, 2016];Readmissions reduction program. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Updated April 18, 2016.

- 18. [Accessed February 2, 2016];H.R. 1314: Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015. Congress.Gov website. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1314/text.

- 19. [Accessed February 9, 2016];Outlook 2016: hospital payments, Medicare reforms among top concerns. Bloomberg BNA. http://www.bna.com/hospital-payments-medicare-n57982066164/. Published January 13, 2016.

- 20.Scott G, Thomas S, Betts D. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Survey of US health care consumers. Deloitte website. 2015 http://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/health-care-consumer-engagement.html.

- 21.McKinsey Center of US Health System Reform. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Hospital networks: evolution of the configurations on the 2015 exchanges. http://healthcare.mckinsey.com/sites/default/files/2015HospitalNetworks.pdf. Published April 2015.

- 22.Center for Clinical Standards and Quality, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 8, 2016];CMS quality measure development plan: supporting the transition to the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS)and alternative payment models (APMs) https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/Final-MDP.pdf. Published May 2, 2016.

- 23.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 15, 2016];Medicare program; merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS)and alternative payment model (APM) incentive under the physician fee schedule, and criteria for physician-focused payment models. Federal Register. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2016-05-9/pdf/2016-10032.pdf. [PubMed]

- 24.Horner J, Wagner E, Tufano J. Electronic consultations between primary and specialty care clinicians: early insights. [Accessed March 1, 2016];The Commonwealth Fund. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Issue%20Brief/2011/Oct/1554_Horner_econsultations_primary_specialty_care_clinicians_ib.pdf. Published October 2011. [PubMed]

- 25.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed April 8, 2016];Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/. Updated October 4, 2016.

- 26.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Bundled Payments for Care Improvement Initiative (BPCI) fact sheet. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-08-13-2.html. Updated April 18, 2016.

- 27.Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation. [Accessed July 21, 2016];Bundled payments for care improvement application model 2—designated awardee/awardee convener sub-proposal. https://innovation.cms.gov/files/x/bpci-md2da.pdf.

- 28.Muhlestein D, Hall C. ACO quality results: good but not great. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Health Affairs Blog. http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2014/12/18/aco-quality-results-good-but-not-great/. Published December 18, 2014.

- 29.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed April 8, 2016];Next Generation accountable care organization model (NGACO Model) https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-01-11.html. Published January 1, 2016.

- 30. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Med Axiom 2013 annual integration report. http://www.medaxiom.com/clientuploads/PDFs/HIS_2013_download.pdf.

- 31.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Next generation ACO Model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Next-Generation-ACO-Model/. Updated September 27, 2016.

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 19, 2016];Notice of proposed rulemaking for bundled payment models for high-quality, coordinated cardiac and hip fracture care. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2016-Fact-sheets-items/2016-07-25.html. Published July 25, 2016.

- 33.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. [Accessed January 28, 2016];Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/practice_management/pcmh/initiatives/PCMHJoint.pdf. Published March 7, 2007.

- 34.Nielsen M, Gibson A, Buelt L, Grundy P, Grumbach K. Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative. [Accessed January 28, 2016];The patient-centered medical home's impact on cost and quality: annual review of evidence. 2013–2014 https://www.pcpcc.org/resource/patient-centered-medical-homes-impact-cost-and-quality. Published January 2015.

- 35.Edwards ST, Bitton A, Hong J, Landon BE. Patient-centered medical home initiatives expanded in 2009-13: providers, patients, and payment incentives increased. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(10):1823–1831. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American College of Physicians. The patient-centered medical home neighbor—the interface of the patient-centered medical home with specialty/subspecialty practices. [Accessed January 28, 2016];American College of Physicians position paper 510101020. https://www.acponline.org/system/files/documents/advocacy/current_policy_papers/assets/pcmh_neighbors.pdf.

- 37.National Committee for Quality Assurance. [Accessed January 28, 2016];Patient-centered specialty practice recognition. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.05.002. http://www.ncqa.org/Programs/Recognition/Practices/PatientCenteredSpecialtyPracticePCSP.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.National Committee of Quality Assurance. [Accessed April 12, 2016];White paper: patient-centered specialty practice recognition. https://www.ncqa.org/Portals/0/Newsroom/2013/PCSP%20Launch/PCSPR%202013%20White%20Paper%203.26.13 %20formatted.pdf.

- 39.American College of Physicians. [Accessed January 28, 2016];High value care coordination (HVCC) toolkit. https://hvc.acponline.org/physres_care_coordination.html.

- 40.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed July 21, 2016];Pioneer ACO model. https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Pioneer-aco-model/. Updated September 27, 2016.

- 41.Rajkumar R, Conway PH, Tavenner M. CMS—engaging multiple payersin payment reform. JAMA. 2014;311(19):1967–1968. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.About the physician group incentive program. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Blue Cross Blue Shield Blue Care Network of Michigan website. http://www.bcbsm.com/providers/value-partnerships/physician-group-incentive-prog.html.

- 43. [Accessed February 9, 2016];Rewarding value in health care: physician group incentive program. Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan website. https://www.bcbsm.com/content/dam/public/Clinicians/Documents/physician-group-incentive-program-basics.pdf.

- 44.Lemak CH, Nahra TA, Cohen GR, et al. Michigan's fee-for-value physician incentive program reduces spending and improves quality in primary care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(4):645–652. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 19, 2106];Evaluation of the Medicare acute care episode (ACE) demonstration: final evaluation report. https://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/ACE-EvaluationReport-Final-5-2-14.pdf. Published May 31, 2013.

- 46.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 19, 2016];Demonstration projects—Medicare heart bypass summary. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Demonstration-Projects/DemoProjectsEvalRpts/downloads/Medicare_Heart_Bypass_Summary.pdf.

- 47.McCarthy D, Mueller K, Wrenn J. Geisinger health system: achieving the potential of system integration through innovation, leadership, measurement, and incentives. [Accessed August 19, 2016];The Commonwealth Fund website. http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/Files/Publications/Case%20Study/2009/Jun/McCarthy_Geisinger_case_study_624_update.pdf.

- 48.Toward Accountable Care Consortium. [Accessed August 19, 2016];The bundled payment guide for physicians. http://www.tac-consortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Bundled-Payment-Guide.pdf.

- 49.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 19, 2016];42 CFR Parts510 and 512: Medicare program; advancing care coordination through episode payment models (EPMs); cardiac rehabilitation incentive payment model; and changes to the comprehensive care for joint replacement model (CJR) https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/advancing-care-coordination-nprm.pdf. Published July 20, 2016.

- 50.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed August 19, 2016];Bundled payments for care improvement initiative (BPCI): background on model 2 for prospective participants. https://innovation.cms.gov/Files/x/BPCI_Model2Background.pdf. Published February 7, 2014.

- 51.Seidman J. [Accessed August 19, 2016];New cardiac bundles could produce some big winners and losers. http://avalere.com/expertise/managed-care/insights/new-cardiac-bundles-could-produce-some-big-winners-and-losers. Published August 11, 2016.

- 52. [Accessed February 2, 2016];Medicare shared savings program accountable care organizations performance year 2014 results. Data.CMS.gov website. https://data.cms.gov/ACO/Medicare-Shared-Savings-Program-Accountable-Care-O/ucce-hhpu.

- 53.Mostashari F, Sanghavi D, McClellan M. Health reform and physician-led accountable care: the paradox of primary care physician leadership. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1855–1856. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Henry Ford Health System. [Accessed January 27, 2016];Accountable care organization. https://www.accenture.com/us-en/success-henry-ford-health-system-accountable-care-organization.aspx.

- 55.Casalino LP, Gans D, Weber R, et al. US physician practices spend more than $15.4 billion annually to report quality measures. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(3):401–406. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.US Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare program; merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) and alternative payment model (APM) incentive under the physician fee schedule, and criteria for physician-focused payment models. [Accessed July 15, 2016];42 CFR parts 414 and 495. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=CMS-2016-0060-0068. Published May 9, 2016. [PubMed]

- 57.Kocher R, Chigurupati A. The coming battle over shared savings—primary care physicians versus specialists. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):104–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1604994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.The evolution of the CV practice landscape. [Accessed January 27, 2016];American College of Cardiology website. http://www.acc.org/membership/member-benefits-and-resources/acc-member-publications/cardiosurve/newsletter/archive/2012/12/the%20evolution%20of%20the%20cv%20practice%20landscape.

- 59. [Accessed July 22, 2016];Survey says: cardiologist employment is on the rise. https://www.advisory.com/research/cardiovascular-roundtable/cardiovascular-rounds/2012/09/cardiologist-employment-on-the-rise. Published September 19, 2012.

- 60. [Accessed February 9, 2016];Merritt Hawkins. 2013 Physician inpatient/outpatient revenue survey. http://www.merritthawkins.com/uploadedFiles/MerrittHawkins/Pdf/mha2013revenuesurveyPDF.pdf.

- 61.Friedberg MW, Chen PG, White C, et al. Effectsofhealth care payment models on physician practice in the United States. [Accessed January 27, 2016];The RAND Corporation website. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR800/RR869/RAND_RR869.pdf.

- 62.Shortell SM. [Accessed May 10, 2016];How30 percent became the “tipping point.” NEJM Catalyst. http://catalyst.nejm.org/how-30-percent-became-the-tipping-point/. Published August 8, 2016.

- 63.Health Care Transformation Task Force. [Accessed on April 8, 2016];Major health care players unite to accelerate transformation of US health care system: leaders. http://www.hcttf.org/releases/2015/1/28/major-health-care-players-unite-to-accelerate-transformation-of-us-health-care-system. Published January 28, 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.