Abstract

Breast cancer affects 1 in 8 women across the United States, and low-income minority breast cancer survivors are at increased risk of job loss compared to higher-income whites. Employer accommodations, such as schedule flexibility, have been associated with job retention in higher-income whites, but the role of such accommodations in job retention among low-income minorities is not well understood. We longitudinally studied 267 employed women aged 18–64 who were undergoing treatment for early-stage breast cancer and spoke English, Chinese, Korean, or Spanish. We categorized patients by income (low vs. middle and high) and by race or ethnicity, and compared post-treatment job retention. Job retention was lowest among low-income women (57 percent), and among Chinese women (68 percent), followed by Koreans (73 percent), Latinas (78 percent), blacks (85 percent), and whites (98 percent). Women who had accommodating employers were more than twice as likely to retain their jobs. Low-income women were less likely to have accommodating employers, however. More uniform implementation of accommodations across low and high paying jobs could reduce disparities in employment outcomes among workers with a cancer diagnosis. Additional research is needed to better understand the barriers employers, particularly employers of low-income workers, may face in providing accommodations.

Breast cancer is a common survivable malignancy with the potential for short- and long-term employment loss and financial instability. Nearly 1 in 8 women are diagnosed with breast cancer in the United States, of whom 58 percent are working age (18–64 years).(1, 2) Advances in early detection and management of breast cancer have led to improvements in overall survival; 90 percent of women diagnosed today are expected to be alive in 5 years.(2)

Approximately 70–80 percent of breast cancer survivors return to work 3–18 months after diagnosis, and receipt of employer accommodations is among the strongest predictors of work continuation 1–2 years following diagnosis.(3–5) When surveyed 18 months after a breast cancer diagnosis, women who reported having had an accommodating employer had twice the odds of working compared to women who did not have an accommodating employer.(3) The role of employer accommodations in the post-treatment employment outcomes of low-income minority breast cancer survivors remains poorly understood, however. In a longitudinal study of low-income, Medicaid-insured breast cancer survivors in California, all of whom were working prior to diagnosis, only 60 percent were employed 3 years later.(6) Latinas comprised the majority of the sample and took longer to return to work than did non-Latina whites. After 5 years of follow-up a concerning trend emerged: 43 percent of those not working 6 months after diagnosis never returned to work.(7)

Job loss can have devastating financial consequences, including increased risk of bankruptcy, debt, or both.(8) Workplace accommodations can positively influence work outcomes of patients with a cancer diagnosis. For example, schedule flexibility is associated with a tremendous improvement in job retention.(9) Sick leave also is critical to cancer patients undergoing treatment. Those who take time off during treatment but lack sick leave may risk losing their jobs. In contrast, patients who receive workplace accommodations and are able to continue working during active treatment are likely to retain employment and work more hours.(9, 10)

Cancer is a condition covered under the Americans with Disabilities Act Amendments Act of 2008, which requires that eligible employers provide “reasonable accommodations,” defined as any modification or adjustment to a job or the work environment that enables an employee with a disability to perform essential job functions. Reasonable accommodations may include modifications to the physical workspace, (such as providing a ramp), modifications to an employee’s schedule to allow for medical appointments or incorporating breaks, and modifications or reassignment of job tasks. However, the Americans with Disabilities Act only applies to government employers and private employers with 15 or more employees, excluding workers employed by small businesses. The US Department of Labor estimates that 40 percent of Americans who work for small private employers (those with fewer than 15 employees) are in the lowest 25 percent of wage earners.(11) Thus, the exclusion disproportionately affects low-income workers. Only 21 percent of those in the lowest 10 percent of wage earners have paid sick leave.(12) Likewise, immigrant and minority workers are less likely to be employed in accommodating settings or to have benefits such as sick leave.(9) In addition, larger employers can avoid providing “reasonable accommodations” if these accommodations result in an “undue hardship” to the employer, a condition that is not clearly defined by the law.

The majority of studies of employment outcomes in breast cancer survivors have included primarily US-born, white, middle-income and insured women. Breast cancer’s effects on low-income women and on immigrants and minorities are understudied. To address this gap, we studied the relationship between income and job retention among women of different socioeconomic and racial and ethnic backgrounds undergoing adjuvant (that is, curative) treatment for breast cancer.

Study Data and Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We used data from the Breast Cancer and the Workforce study, a prospective, longitudinal study of disparities in employment outcomes among women undergoing treatment for stage I–III breast cancer in New York City. Participants were recruited between September 2010 and May 2016 from four hospitals and clinics serving residents of diverse and underserved neighborhoods in New York City (including two community cancer clinics, a county hospital, and a community hospital) and from a National Cancer Institute-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. Women from racial and ethnic minority and immigrant groups were oversampled. The Institutional Review Boards at all recruitment sites approved this study. All participants gave their informed consent.

Eligible participants were women aged 18–64 who were able to provide informed consent in English, Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin), Korean, or Spanish; undergoing active treatment for stage I–III (that is, curable) breast cancer; and working for pay (full time or part time) before diagnosis. Active treatment was defined as currently undergoing chemotherapy or radiation therapy or having undergone definitive surgery for breast cancer no more than 60 days before study enrollment. Potential participants were approached at oncology visits by bilingual or multilingual research staff.

Participants completed two surveys online or in a computer-assisted telephone interview, depending on their preference. The baseline survey was completed within 2 weeks of enrollment and the follow-up survey approximately 4 months after treatment completion. All study materials were translated and pilot tested.(13)

Measures

The primary outcome was job retention 4 months after completion of treatment. Participants were considered to have retained a job if they reported that they were working full-time or part-time (regardless of whether or not they had changed employers), on paid sick leave, on unpaid sick leave, or on disability leave. All other responses were classified as “job not retained,” including participants who reported that they were not working and looking for a job, not working and not looking for a job, otherwise not working, or retired. In light of the importance of employer accommodations as a predictor of job retention, participants also were asked how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: “My employer/job is good at accommodating my illness and need for treatment.” Responses to this question were dichotomized.

All data were self-reported at baseline except job retention which was self-reported at follow-up. Household income was classified as a percentage of the Federal Poverty Level, which takes into account household size and secular trends. Participants reported the number of family members who lived with them. Household income was approximated using the midpoint of the dollar range the participant selected in response to the question, “Which category is closest to your household’s total combined income in the last year?” Income was categorized as low income (<200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level), middle income (200–400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level) or high income (>400 percent of the Federal Poverty Level) using the Poverty Guidelines described by Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation for the year prior to the participant’s survey.(14) Income level was dichotomized as low versus middle and high combined for multivariable analyses.

Participants reported employer size and job tenure. Job type was classified using the Bureau of Labor Statistics 2010 Standard Occupational Codes using patient responses to two open-ended questions: “What is your job title?” and “What kind of work do you do?” and two multiple-choice questions regarding occupation and industry.(15) Based on the distribution of data within our sample, groups were further collapsed to yield a total of three categories: managerial or professional; office or sales; and transportation, production, or service.

Additional demographic data included race or ethnicity, place of birth, age, and family structure (whether the participant was married or partnered versus single and the total number of people in household). Type of health insurance was coded into three categories: private insurance provided through the participant’s job, other private insurance (e.g. provided through a spouse’s job), and publicly-provided insurance (e.g. Medicaid, Emergency Medicaid, and Medicare). Education was categorized as less than or equal to a high-school diploma or more than high school (including vocational school or part of college completed). Acculturation was measured in participants who spoke a language other than English or had done so as children using an index based on language use and preference.(16)

Participants self-reported comorbid medical conditions using the Charlson Comorbidity Index modified for patient report.(17, 18) Additional clinical and treatment data (breast cancer stage, treatments received, and date of last treatment) were abstracted from medical records.

Analysis

Chi-squared tests were used to test differences in categorical demographic, employment, and clinical characteristics of the three income groups and of the five racial or ethnic groups. Mean age was compared across groups using analysis of variance. Analyses focused on having an accommodating employer and job retention. For each outcome, we fit two sets of logistic regression models. In the first set, we evaluated the relationship between each baseline characteristic and the outcome (having an accommodating employer or job retention) adjusted for income. In the second set, we evaluated the relationship between each baseline characteristic and the outcome adjusted for race or ethnicity. Based on these findings, we then fit a multivariable logistic regression model for each of the two outcomes to identify independent correlates and predictors of having an accommodating employer and job retention. The final models included variables that were statistically significant (two-sided p <0.05) in one or both sets of adjusted analyses. Due to sample size considerations and concerns about collinearity, not all variables were used in the multivariable models.(19) All analyses were conducted in SAS v9.4. All p-values are two-sided, and p-values <0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, a longitudinal survey, though best for studying causal relationships, is vulnerable to non-response bias with regard to both the baseline and the follow-up survey. An analysis of the characteristics of those who did and did not complete surveys is included as an online appendix (Appendix Exhibit 1).(20) No significant differences in race or ethnicity, or in age, were found between those who enrolled in the study but did not complete a baseline survey and those who completed a baseline survey. Overall participants who were lost to follow-up were similar to those who completed a follow-up survey. However, we found statistically significant differences between these groups based on income, education, and whether or not the participant’s earnings were salaried. For all three characteristics, those who did not complete the survey were more likely to not retain their jobs, indicating that our analyses may underestimate the impact of these characteristics on job retention. Additionally, participants with higher cancer stage and those without any comorbid medical conditions were more likely to be lost to follow-up. Neither characteristic was associated with the study outcomes.

Second, our study sample was recruited in New York City, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to populations living in rural or smaller urban communities.

Results

Of 319 participants who completed a baseline survey and reached the follow-up window (starting 3 months after the date of last treatment and ending 2 months later), 267 (84 percent) completed a follow-up survey (for an analysis of the characteristics of those who did and did not complete follow-up surveys, see Appendix Exhibit 1).(20) The average time to follow up was 121 days after date of last treatment for breast cancer.

We successfully recruited a racially and ethnically diverse sample of women. Overall, 20 percent of the sample was black, 19 percent was Chinese, 10 percent was Korean, 31 percent was Latina, and 20 percent was non-Latina white.

Eighty-five participants (32 percent of the sample) were low-income, 67 were middle-income (25 percent), and 115 were high-income (43 percent). Approximately 81 percent of participants retained their jobs at follow-up (including 6 participants who changed employers). Job retention varied significantly across income groups: 57 percent of those in the low-income group retained their jobs at follow-up compared to 90 percent and 95 percent of the middle- and high-income groups, respectively (p<0.0001). Significant differences in job retention also were found across racial and ethnic groups. Job retention was 68 percent among Chinese participants, 73 percent among Koreans, 78 percent among Latinas, 85 percent among blacks, and 98 percent among non-Latina whites (p=<0.005).

Participant characteristics varied significantly by income (Exhibit 1) and by race and ethnicity (Exhibit 2). No significant differences were found in cancer or treatment characteristics across income or racial and ethnic groups, so we did not adjust for these characteristics in our models.

Exhibit 1. Study participant characteristics by income group.

Study participant characteristics by income group

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from the Breast Cancer and the Workforce study

| Low-income (<200%

FPL) n=85 |

Middle-income (200–400%

FPL) n=67 |

High-income (>400%

FPL) n=115 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | ||

| Characteristic | ||||

| Age (mean, range) | 50.3 27.7–64.9 |

51.6 32.3–64.6 |

47.3 24.9–64.5 |

0.004 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 16.5% | 15.4% | 20.9% | <0.001 |

| Chinese | 20.0 | 13.4 | 20.9 | |

| Korean | 9.4 | 11.9 | 8.7 | |

| Latina | 51.8 | 29.9 | 16.5 | |

| Non-Latina white | 2.4 | 19.4 | 33.0 | |

| Foreign borna | 83.5% | 58.2% | 41.2% | <0.001 |

| Less-acculturated | 74.1% | 46.3% | 18.3% | <0.001 |

| Single-income household | 76.5% | 52.2% | 40.9% | <0.001 |

| Married or long-term partnera | 51.8% | 56.7% | 69.9% | 0.026 |

| More than high-school educationa,b | 48.8% | 71.6% | 92.2% | <0.001 |

| Job typea | ||||

| Managerial or professional specialty | 9.5% | 37.9% | 74.8% | <0.001 |

| Office or sales | 22.6 | 25.8 | 14.8 | |

| Transportation, production, service | 67.9 | 36.4 | 10.4 | |

| Number of employees in workplacea | ||||

| Fewer than 15 | 42.5% | 25.0% | 17.7% | 0.004 |

| 15–49 | 7.5 | 9.4 | 8.0 | |

| 50 or more | 50.0 | 65.6 | 74.3 | |

| Salaried earningsa | 30.1% | 37.9% | 71.4% | <0.001 |

| Job tenure >2 yearsa | 71.3% | 91.0% | 87.8% | 0.001 |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Employer-sponsored | 28.2% | 61.2% | 77.4% | <0.001 |

| Private, other | 11.8 | 13.4 | 17.4 | |

| Public or no insurance | 60.0 | 25.4 | 5.2 | |

| Employer was accommodatinga | 45.1% | 59.7% | 67.5% | 0.007 |

| Stage II or III breast cancer | 56.5% | 55.2% | 56.5% | 0.986 |

| Mastectomy | 45.9% | 49.3% | 48.7% | 0.897 |

| Axillary dissection | 34.1% | 31.3% | 34.8% | 0.890 |

| Received chemotherapya | 84.7% | 83.6% | 87.7% | 0.707 |

| Received radiationa | 74.1% | 70.2% | 75.4% | 0.733 |

| Number of comorbid conditions (≥1) | 30.6% | 22.4% | 20.0% | 0.209 |

Notes:

Data missing for >=1 participant. Percentages calculated over complete data.

More than high school education could include technical/vocational school, Associate’s Degree, or some or all of a Bachelor’s Degree.

Exhibit 2. Study participant characteristics by race/ethnicity.

Study participant characteristics by race or ethnicity

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from the Breast Cancer and the Workforce study

| Black n=55 |

Chinese n=50 |

Korean n=26 |

Latina n=83 |

Non-Latina white n=53 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, range) | 49.9 35.6–64.6 |

48.8 33.1–64.3 |

47.4 32.6–64.5 |

49.6 25.8–64.9 |

49.7 24.9–64.4 |

0.778 |

| Income | ||||||

| Low (<200% FPL) | 25.5% | 34.0% | 30.8% | 53.0% | 3.8% | <0.001 |

| Middle (200–400% FPL) | 30.9 | 18.0 | 30.8 | 24.1 | 24.5 | |

| High (>400% FPL) | 43.6 | 48.0 | 38.5 | 22.9 | 71.7 | |

| Foreign borna | 36.4% | 86.0% | 92.0% | 74.7% | 17.0% | <0.001 |

| Less-acculturated | 1.8% | 60.0% | 76.9% | 71.1% | 9.4 % | <0.001 |

| Single-income household | 67.3% | 42.0% | 53.9% | 65.1% | 39.6% | 0.004 |

| Married or long-term partnera | 43.6% | 79.6% | 73.1% | 53.7% | 66.0% | 0.001 |

| More than high-school educationa,b | 72.7% | 66.0% | 80.8% | 61.0% | 96.2% | <0.001 |

| Job typea | ||||||

| Managerial or professional specialty | 50.9% | 46.9% | 34.6% | 28.1% | 67.9% | <0.001 |

| Office or sales | 20.0 | 16.3 | 34.6 | 18.3 | 18.9 | |

| Transportation, production, service | 29.1 | 36.7 | 30.8 | 53.7 | 13.2 | |

| Number of employees in workplacea | ||||||

| Fewer than 15 | 10.9% | 27.7% | 70.8% | 25.6% | 26.4% | <0.001 |

| 15–49 | 5.5 | 8.5 | 8.3 | 11.5 | 5.7 | |

| 50 or more | 83.6 | 63.8 | 20.8 | 62.8 | 67.9 | |

| Salaried earningsa | 41.8% | 68.0% | 40.0% | 41.5% | 59.2% | 0.011 |

| Job tenure >2 yearsa | 85.5% | 81.6% | 83.3% | 82.7% | 84.9% | 0.983 |

| Health insurance | ||||||

| Employer-sponsored | 63.6% | 60.0% | 42.3% | 51.8% | 66.0% | <0.001 |

| Private, other | 9.1 | 14.0 | 19.2 | 7.2 | 30.2 | |

| Public | 27.3 | 26.0 | 38.5 | 41.0 | 3.8 | |

| Employer was accommodatinga | 52.7% | 44.0% | 68.0% | 61.3% | 69.8% | 0.060 |

| Stage II or III breast cancer | 61.8% | 56.0% | 53.9% | 54.2% | 54.7% | 0.918 |

| Mastectomy | 38.2% | 50.0% | 50.0% | 57.8% | 39.6% | 0.139 |

| Axillary dissection | 32.7% | 32.0% | 23.1% | 38.6% | 34.0% | 0.685 |

| Received chemotherapya | 96.4% | 80.0% | 80.8% | 85.5% | 82.7% | 0.119 |

| Received radiationa | 78.2% | 80.0% | 57.7% | 71.1% | 75.0% | 0.252 |

| Number of comorbid conditions (≥1) | 21.8% | 20.0% | 38.5% | 30.1% | 13.2% | 0.070 |

Notes:

Data missing for >=1 participant. Percentages calculated over complete data.

More than high school education could include technical/vocational school, Associate’s Degree, or some or all of a Bachelor’s Degree.

Accommodating Employers

Controlling for race and ethnicity only, participants were more likely to report that their employer had been accommodating if they were more acculturated (based on English language use and preference) or had longer job tenure, and were less likely to report their employer had been accommodating if they were in the low-income group (for a full list of the odds of employer accommodation based on participant characteristics, see Appendix Exhibit 2).(20) After controlling for income rather than race and ethnicity, none of the characteristics examined were significantly associated with having an accommodating employer.

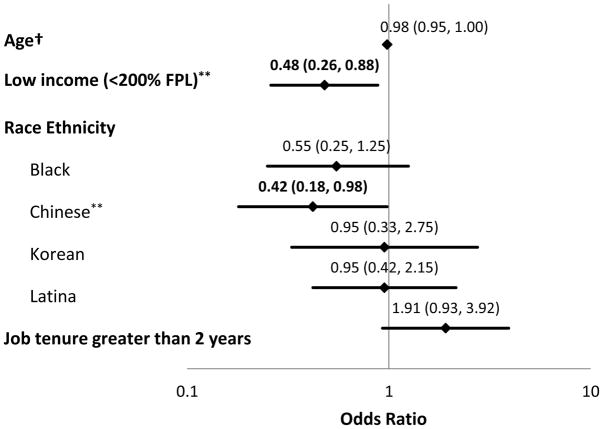

In a multivariable analysis, low-income and being Chinese were independently associated with lower probabilities of having an accommodating employer (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3. Model describing the odds of having an accommodating employer.

Independent predictors of having an accommodating employer

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from the Breast Cancer and the Workforce study

Notes: Diamond indicates point estimate for odds ratio; horizontal line indicates 95% confidence interval.

Corresponding data are included above each data point as OR (95% confidence interval). FPL: Federal Poverty Level †Odds ratio corresponds to a one-year increase in age.

**p <0.05

| Covariate | data points | position on y-axis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | upper limit | 1.004 | 8 |

| odds ratio | 0.98 | 8 | |

| lower limit | 0.95 | 8 | |

| Low Income (<200% FPL) | upper limit | 0.88 | 7 |

| odds ratio | 0.48 | 7 | |

| lower limit | 0.26 | 7 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | upper limit | 1.25 | 5 |

| odds ratio | 0.55 | 5 | |

| lower limit | 0.25 | 5 | |

| Chinese | upper limit | 0.98 | 4 |

| odds ratio | 0.42 | 4 | |

| lower limit | 0.18 | 4 | |

| Korean | upper limit | 2.75 | 3 |

| odds ratio | 0.95 | 3 | |

| lower limit | 0.33 | 3 | |

| Latina | upper limit | 2.15 | 2 |

| odds ratio | 0.95 | 2 | |

| lower limit | 0.42 | 2 | |

| Job tenure greater than 2 years | upper limit | 3.92 | 1 |

| odds ratio | 1.91 | 1 | |

| lower limit | 0.93 | 1 | |

Job Retention

Controlling for race and ethnicity, job retention was higher among participants who were more acculturated, more educated, worked for large employers, had access to private health insurance, earned a salaried income, or reported that their employer was accommodating (for a full list of the odds of job retention based on participant characteristics, see Appendix Exhibit 2).(20) Job retention was lower for those who were older, in the low-income group, were the sole providers of household income, or worked in either office or sales jobs or in transportation, production, and service jobs.

Controlling for income, only having private health insurance and having an accommodating employer were significantly correlated with job retention, while older age was inversely correlated with job retention.

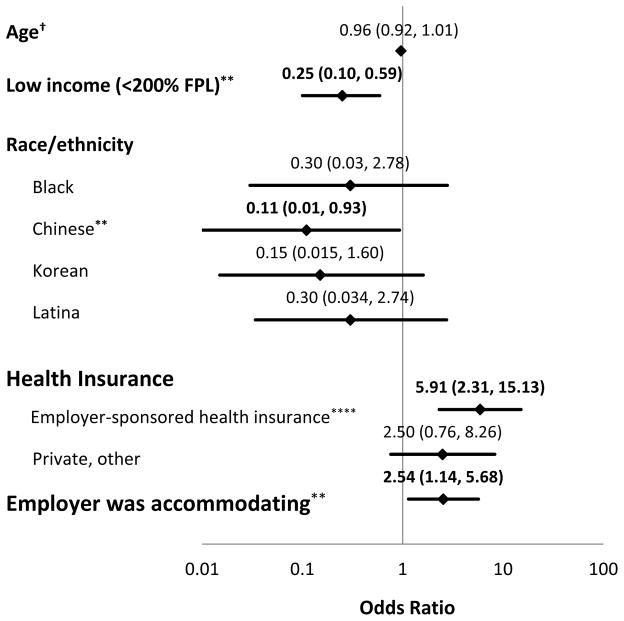

In a multivariable analysis, having an accommodating employer and employer-sponsored health insurance were independently associated with significantly higher probabilities of job retention, whereas having low income and being Chinese were associated with significantly lower probabilities of job retention (Exhibit 4).

Exhibit 4. Model describing the odds of job retention.

Independent predictors of job retention among study participants

Source: Authors’ analysis of data from the Breast Cancer and the Workforce study

Notes: Diamond indicates point estimate for odds ratio; horizontal line indicates 95% confidence interval.

Corresponding data are included above each data point as OR (95% confidence interval). FPL: Federal Poverty Level †Odds ratio corresponds to a one-year increase in age.

**p <0.05, ***p <0.01, ****p <0.001

| Covariate | data points | position on y-axis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | upper limit | 1.01 | 11 |

| odds ratio | 0.96 | 11 | |

| lower limit | 0.92 | 11 | |

| Low Income (<200% FPL) | upper limit | 0.59 | 10 |

| odds ratio | 0.25 | 10 | |

| lower limit | 0.1 | 10 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | upper limit | 2.78 | 8 |

| odds ratio | 0.3 | 8 | |

| lower limit | 0.03 | 8 | |

| Chinese | upper limit | 0.93 | 7 |

| odds ratio | 0.11 | 7 | |

| lower limit | 0.01 | 7 | |

| Korean | upper limit | 1.6 | 6 |

| odds ratio | 0.15 | 6 | |

| lower limit | 0.015 | 6 | |

| Latina | upper limit | 2.74 | 5 |

| odds ratio | 0.3 | 5 | |

| lower limit | 0.034 | 5 | |

| Health insurance | |||

| Employer sponsored | upper limit | 15.13 | 3 |

| odds ratio | 5.91 | 3 | |

| lower limit | 2.31 | 3 | |

| Other private | upper limit | 8.26 | 2 |

| odds ratio | 2.5 | 2 | |

| lower limit | 0.76 | 2 | |

| Employer was acccommodating | upper limit | 5.68 | 1 |

| odds ratio | 2.54 | 1 | |

| lower limit | 1.14 | 1 | |

Sensitivity analyses of job retention on year of study enrollment, comorbidity burden, and retirement did not substantially alter our findings (for detailed results of the sensitivity analyses, see Appendix Exhibits 3–5).(20)

Appendix Exhibit 1.

Participant characteristics by baseline and follow-up survey completion

| Follow-up survey not

completed, n=52 |

Follow-up survey

completed, n=267 |

p-value | Consented, baseline survey

not completed, n=83 |

Baseline survey

completed, n=319 |

p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Characteristic | ||||||||||

| Age (mean, range) | 49.2 | (28.4–62.6) | 49.3 | (24.8–64.9) | 0.936 | 47.6 | (31.2–60.6) | 49.3 | (24.9–64.9) | 0.436 |

| Income | ||||||||||

| Low (<200% FPL) | 26 | 51.0% | 85 | 31.8% | ||||||

| Middle (200–400% FPL) | 11 | 21.6 | 67 | 25.1 | ||||||

| High (>400% FPL) | 14 | 27.5 | 115 | 43.1 | 0.026 | |||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Black | 11 | 21.2% | 55 | 20.6% | 20 | 24.1% | 66 | 20.7% | ||

| Chinese | 10 | 19.2 | 50 | 18.7 | 19 | 22.9 | 59 | 18.5 | ||

| Korean | 4 | 7.7 | 26 | 9.7 | 11 | 13.3 | 60 | 18.8 | ||

| Latina | 21 | 40.4 | 83 | 31.1 | 29 | 34.9 | 104 | 32.6 | ||

| Non-Latina white | 6 | 11.5 | 53 | 19.9 | 0.560 | 4 | 4.8 | 30 | 9.4 | 0.418 |

| Birthplace | ||||||||||

| Foreign born | 38 | 73.1% | 157 | 59.0% | ||||||

| US born | 14 | 26.9 | 109 | 40.1 | 0.057 | |||||

| Acculturation | ||||||||||

| Low | 26 | 50.0% | 115 | 43.1% | ||||||

| High | 26 | 50.0 | 152 | 56.9 | 0.357 | |||||

| Single-income household | ||||||||||

| No | 23 | 44.2% | 120 | 44.9% | ||||||

| Yes | 29 | 55.8 | 147 | 55.1 | 0.925 | |||||

| Married or long-term partner | ||||||||||

| No | 18 | 35.3% | 104 | 39.3% | ||||||

| Yes | 33 | 64.7 | 161 | 60.75 | 0.596 | |||||

| > High school education | ||||||||||

| No | 22 | 42.3% | 71 | 26.7% | ||||||

| Yes | 30 | 57.7 | 195 | 73.3 | 0.024 | |||||

| Job type | ||||||||||

| Managerial, professional | 17 | 37.0% | 119 | 44.9% | ||||||

| Office/sales | 15 | 32.6 | 53 | 20.0 | ||||||

| Transportation, production, service | 14 | 30.4 | 93 | 35.1 | 0.160 | |||||

| Number of employees in workplace | ||||||||||

| <15 | 17 | 33.3% | 70 | 27.2% | ||||||

| 15–49 | 4 | 7.8 | 21 | 8.2 | ||||||

| 50+ | 30 | 58.8 | 166 | 64.6 | 0.674 | |||||

| Earnings type | ||||||||||

| Non-salaried | 35 | 67.3% | 131 | 50.2% | ||||||

| Salaried | 17 | 32.7 | 130 | 49.8 | 0.024 | |||||

| Job tenure | ||||||||||

| ≥2 years | 44 | 84.6% | 219 | 83.6% | ||||||

| <2 years | 8 | 15.4 | 43 | 16.4 | 0.854 | |||||

| Health insurance | ||||||||||

| Employer-sponsored | 26 | 50.0% | 154 | 57.7% | ||||||

| Private, other | 8 | 15.4 | 39 | 14.6 | ||||||

| Public | 18 | 34.6 | 74 | 27.7 | 0.551 | |||||

| Employer was accommodating | ||||||||||

| No | 16 | 38.1% | 109 | 41.4% | ||||||

| Yes | 26 | 61.9 | 154 | 58.6 | 0.682 | |||||

| Cancer stage | ||||||||||

| I | 11 | 26.2% | 117 | 43.8% | ||||||

| II or III | 31 | 73.8 | 150 | 56.2 | 0.031 | |||||

| Mastectomy | ||||||||||

| No | 25 | 54.4% | 139 | 52.1% | ||||||

| Yes | 21 | 45.7 | 128 | 47.9 | 0.774 | |||||

| Axillary Dissection | ||||||||||

| No | 25 | 62.5% | 177 | 66.3% | ||||||

| Yes | 15 | 37.5 | 90 | 33.7 | 0.637 | |||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||||

| None | 2 | 5.1% | 38 | 14.2% | ||||||

| Received | 37 | 94.9 | 229 | 85.8 | 0.115 | |||||

| Radiation therapy | ||||||||||

| None | 8 | 19.5% | 70 | 26.3% | ||||||

| Received | 33 | 80.5 | 196 | 73.7 | 0.352 | |||||

| Comorbid conditions (Katz index) | ||||||||||

| None | 46 | 88.5% | 203 | 76.0% | ||||||

| One or more | 6 | 11.5% | 64 | 24.0% | 0.048 | |||||

FPL: Federal Poverty Level

Appendix Exhibit 3.

Sensitivity analysis: impact of enrollment year on job retention.

| Characteristic | Odds of job retention | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | 0.96 | 0.13 |

|

| ||

| Income <200% FPL | 0.25 | 0.002 |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 0.30 | 0.28 |

| Chinese | 0.11 | 0.048 |

| Latina | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| Korean | 0.15 | 0.11 |

|

| ||

| Health insurance | ||

| Employer-sponsored | 6.13 | 0.002 |

| Private, other | 2.48 | 0.13 |

|

| ||

| Employer was accommodating | 2.35 | 0.04 |

|

| ||

| Enrollment year (reference is 2010–2011) | ||

| 2012–2013 | 1.003 | 0.997 |

| 2014–2016 | 0.61 | 0.55 |

FPL: Federal Poverty Level

Discussion

Using primary data collected from a racially and ethnically diverse cohort of women with a new diagnosis of breast cancer, we found that women with very low household incomes were at high risk of having unaccommodating employers, likely leading to their high risk of job loss. Specifically, low-income women were only half as likely as higher-income women to have accommodating employers and only one-fourth as likely to retain their jobs. However, women who had accommodating employers were more than twice as likely to retain their jobs, even after controlling for income. Improving access to employer accommodations could play an important role in abrogating the disparity in job retention after a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Chinese women were less likely to have accommodating employers and to retain their jobs compared to non-Latina whites. Other racial and ethnic groups did not differ significantly from non-Latina whites in this regard. The reasons for this disparity are unclear, and additional research is needed to better understand the specific circumstances that may impact the access to accommodations and work trajectories of Chinese breast cancer survivors.

Job retention also was associated with having private health insurance. Women with private health insurance provided through their employers were nearly 6 times as likely to retain their jobs compared to those who were publicly insured, even after controlling for employer accommodations and income. Employer-sponsored health insurance has been linked to greater attachment to the work force in breast cancer survivors, and it is possible that a preference to continue to receive insurance through an employer may partly explain our findings.(21) However, in our surveys we asked participants who reported having health insurance provided through their employer to tell us whether or not fear of losing that insurance was a factor in whether or not they continued to work. There was no significant relationship between job retention and participant response to this question. Having private insurance may be an indicator of having a better job with respect to job characteristics not measured in our study. Another possibility is that those with private insurance had better access to rehabilitation services, which could conceivably be related to recovery and work performance.

Low-income women in our study were a relatively homogeneous group across most measured characteristics, with the exception of differences in race and ethnicity within this income group. Low-income women were more likely to be foreign-born; work in transportation, production, or service; and to work for smaller employers. They also were less likely to have accommodating employers or private health insurance, both characteristics that were independently associated with decreased job retention.

Our study sample was drawn largely from medical oncology practices, and the majority of the sample underwent chemotherapy. We previously have shown that receipt of chemotherapy can have a powerful impact on job retention in the long term, with clinically meaningful and statistically significant differences in job retention as long as 5 years after diagnosis between women who did and did not receive chemotherapy.(7) Other groups have reported similar findings.(5) The impact of chemotherapy on job loss occurs early; women who take time off during treatment are at highest risk of job loss in the long term.(7) Chemotherapy may contribute to job loss due to chronic and persistent side effects as well as acute, self-limited toxicities that require time off from work. In this study, employer accommodations may have abrogated the negative impact of chemotherapy on job retention.

Although working for an employer with fewer than 15 workers was not significantly associated with having an accommodating employer or job retention, nearly half of low-income women in our study were not protected under the Americans with Disabilities Act because they worked for small employers. Increasing access to employer accommodations could be achieved through policy changes that expand the Americans with Disabilities Act. Such an expansion could ensure that low-income workers employed by small firms are able to continue to work both during and after treatment. However, an expansion must be balanced against the potential hardship imposed on small employers. Tax credits could be used to offset the added costs incurred by small businesses seeking to accommodate their employees. Providing financial incentives to businesses that accommodate their employees may be more acceptable than imposing penalties for their absence. In addition, temporary workers could be used to assist during the absence of an employee undergoing treatment. Additional research is needed to better understand the barriers employers may face in providing accommodations to ill workers.

Regardless of their number of employees, employers can seek an exemption under the Americans with Disabilities Act if they deem that accommodating an employee would result in an “undue hardship.” However, there is no clear legal definition of the circumstances that constitute such a hardship. In 2015 the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which enforces the Americans with Disabilities Act, received 922 claims of cancer-related discrimination, representing 3.4 percent of all claims and likely the proverbial “tip of the iceberg” in light of employee concerns about fear of retaliation.(22) Increased oversight is needed to ensure that the concept of “undue hardship” is not abused by employers to avoid providing reasonable accommodations.

As income disparities in the United States widen, concomitant disparities in outcomes such as job retention following diagnosis and treatment of a serious illness may also widen. Improved access to accommodations could prevent job loss and its downstream effects. Action steps that may expedite access to accommodations can be taken at the policy level, by expanding the Americans with Disabilities Act, and at the patient level. Patients may benefit from tools that help them communicate more effectively with their employers to obtain needed accommodations and keep working.

Conclusion

Our study provides strong evidence of a disparity in job accommodations and retention affecting women whose household incomes are below 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level. Although the majority of our study participants were from racial and ethnic minority and immigrant groups, differences in income level and related characteristics, such as access to employer accommodations, appear to be more salient determinants of job retention than race or ethnicity. We are following the study cohort for an additional two years to evaluate the impact of breast cancer on long-term job retention. Breast cancer survivors who do not continue to work during or after treatment completion are likely to suffer long-term job loss. Therefore, job protections are critical to an already-vulnerable population of low-income women.

Additional research is needed to understand the employment trajectories of breast cancer survivors living in other parts of the country, particularly non-urban areas. Local differences in regulations and labor market conditions may affect the impact of breast cancer on job retention.

At the policy level, an expansion of the Americans with Disabilities Act may increase access to accommodations among low-income workers, improving their likelihood of long-term job retention and limiting their financial vulnerability as a result of a serious illness.

Appendix Exhibit 2.

Odds of employer accommodation and job retention adjusted for income, race/ethnicity

| Odds of having an accommodating employer | Odds of job retention | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted for income group | Adjusted for race/ethnicity | Adjusted for income group | Adjusted for race/ethnicity | |

| Characteristic | Odds ratio | Odds ratio | Odds ratio | Odds ratio |

| Age | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.95** | 0.95** |

| Income | ||||

| Low (<200% FPL) | N/A | 0.54 | N/A | 0.16*** |

| Middle (200–400% FPL) | N/A | Ref | N/A | ref |

| High (>400% FPL) | N/A | 1.52 | N/A | 2.19 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Latina white | Ref | N/A | Ref | N/A |

| Black | 0.61 | N/A | 0.25 | N/A |

| Chinese | 0.44 | N/A | 0.08** | N/A |

| Korean | 1.24 | N/A | 0.11 | N/A |

| Latina | 1.15 | N/A | 0.28 | N/A |

| Birthplace | ||||

| Foreign born | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| US born | 0.81 | 0.95 | 1.57 | 1.77 |

| Acculturation based on language preference | ||||

| Non-English | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| English | 1.20 | 2.31*** | 1.66 | 3.32** |

| Single-income household | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.36 | 1.02 | 1.06 | 0.49** |

| Relationship status | ||||

| Not partnered | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Married or long-term partner | 0.92 | 1.07 | 0.56 | 0.98 |

| Education level | ||||

| High school or equivalent or less | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| More than high school | 0.64 | 0.87 | 1.45 | 2.59** |

| Job type | ||||

| Managerial, professional | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Office/sales | 0.997 | 0.65 | 0.73 | 0.34** |

| Transportation, production, service | 1.33 | 0.72 | 0.67 | 0.22*** |

| Number of employees in workplace | ||||

| <15 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 15–49 | 1.02 | 1.44 | 0.54 | 1.02 |

| ≥50 | 0.97 | 1.47 | 1.60 | 2.65** |

| Type of earnings | ||||

| Not salaried | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Salaried | 0.90 | 1.30 | 0.93 | 2.12** |

| Job tenure | ||||

| <2 years | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| ≥2 years | 1.79 | 2.13** | 1.18 | 2.03 |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Public | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Employer-sponsored | 0.66 | 1.17 | 5.60*** | 11.68**** |

| Private, other | 1.42 | 2.03 | 2.512 | 3.49** |

| Employer was accommodating | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | N/A | N/A | 2.47** | 2.96** |

| Number of comorbid conditions | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| One or more | 0.72 | 0.63 | 1.01 | 0.90 |

| Cancer stage | ||||

| I | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| II or III | 1.24 | 1.27 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| Mastectomy | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.16 | 1.12 | 0.72 | 0.93 |

| Axillary Dissection | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Yes | 1.48 | 1.45 | 0.99 | 0.96 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Received | 1.80 | 1.84 | 1.12 | 1.09 |

| Radiation therapy | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Received | 1.10 | 1.23 | 0.98 | 0.95 |

p <0.05,

p <0.01,

p <0.001

FPL: Federal Poverty Level

Appendix Exhibit 4.

Sensitivity analysis: impact of comorbidity burden on job retention.

| Characteristic | Odds of job retention | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | 0.96 | 0.10 |

|

| ||

| Income <200% FPL | 0.24 | 0.002 |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 0.29 | 0.28 |

| Chinese | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| Korean | 0.14 | 0.10 |

| Latina | 0.29 | 0.28 |

|

| ||

| Health insurance | ||

| Employer-sponsored | 5.75 | 0.003 |

| Private, other | 2.39 | 0.16 |

|

| ||

| Employer was accommodating | 2.64 | 0.02 |

|

| ||

| One or more comorbid condition | 1.27 | 0.62 |

FPL: Federal Poverty Level

Appendix Exhibit 5.

Sensitivity analysis: Odds of job retention with retired participants excluded

| Characteristic | Odds of job retention | p-value |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | 0.98 | 0.31 |

|

| ||

| Income <200% FPL | 0.23 | 0.002 |

|

| ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Black | 0.40 | 0.43 |

| Chinese | 0.13 | 0.07 |

| Latina | 0.34 | 0.34 |

| Korean | 0.18 | 0.16 |

|

| ||

| Health insurance | ||

| Employer-sponsored | 6.49 | 0.0002 |

| Private, other | 2.85 | 0.10 |

|

| ||

| Employer was accommodating | 2.75 | 0.02 |

FPL: Federal Poverty Level

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2015–2016. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, Inc; 2015. [cited 2016 August 24]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-046381.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2016. [cited 2016 August 24]. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2013/sections.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo Z. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(3):345–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.4929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satariano WA, DeLorenze GN. The likelihood of returning to work after breast cancer. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(3):236–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagsi R, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, Li Y, Janz NK, Griggs JJ, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on long-term employment of survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(12):1854–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blinder V, Patil S, Thind A, Diamant A, Hudis C, Basch E, et al. Return to work in low-income Latina non-Latina White breast cancer survivors: A three-year longitudinal study. Cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1002/cncr.26478. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blinder V, Patil S, Eberle C, Griggs J, Maly RC. Early predictors of not returning to work in low-income breast cancer survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140(2):407–16. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2625-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banegas MP, Guy GP, Jr, de Moor JS, Ekwueme DU, Virgo KS, Kent EE, et al. For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(1):54–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support on missed work after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119(1):213–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0389-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumark D, Bradley CJ, Henry M, Dahman B. WORK CONTINUATION WHILE TREATED FOR BREAST CANCER: THE ROLE OF WORKPLACE ACCOMMODATIONS. Industrial & labor relations review. 2015;68(4):916–54. doi: 10.1177/0019793915586974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US and states, NAICS sectors, small employment sizes less than 500. United States Census Bureau; 2013. [cited 2016 August 24]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/data/tables/2013/econ/susb/2013-susb-annual.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor. Employee Benefits in the United States--March 2011, USDL-11-1112. 2011 [cited 2012 May 15]. Available from: http://www.bls.gov/ncs/ebs/sp/ebnr0017.pdf.

- 13.Eremenco SL, Cella D, Arnold BJ. A comprehensive method for the translation and cross-cultural validation of health status questionnaires. Eval Health Prof. 2005;28(2):212–32. doi: 10.1177/0163278705275342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Federal Poverty Guidelines Used to Determine Financial Eligibility for Certain Federal Programs. Washington, DC: Office of The Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2016. [cited 2016 August 21]. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/poverty-guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galvin J. 2010 SOC User Guide. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, on behalf of the Standard Occupational Classification Policy Committee (SOCPC); 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marin G, Sabogal F, Marin B, Otero-Sabogal R, Perez-Stable E. Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1987;9(2):183–205. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Diseases. 1987;40(5):373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz JN, Chang LC, Sangha O, Fossel AH, Bates DW. Can comorbidity be measured by questionnaire rather than medical record review? Med Care. 1996;34(1):73–84. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–9. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 21.Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo ZH, Bednarekr HL. Employment-contingent health insurance, illness, and labor supply of women: evidence from married women with breast cancer. Health Econ. 2007;16:719–37. doi: 10.1002/hec.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Enforcement and Litigation Statistics. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA) Charges. [cited 2016 October 25]. Available from: https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/ada-receipts.cfm.