Summary

Here, we define the landscape and dynamics of active regulatory DNA in cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) by ATAC-seq. Analysis of 111 human CTCL and control samples revealed extensive chromatin signatures that distinguished leukemic, host, and normal CD4+ T cells. We identify three dominant patterns of transcription factor (TF) activation that drive leukemia regulomes, as well as TF deactivations that alter host T cells in CTCL patients. Clinical response to histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) is strongly associated with a concurrent gain in chromatin accessibility. HDACi causes distinct chromatin responses in leukemic and host CD4+ T cells, reprogramming host T cells toward normalcy. These results provide a foundational framework to study personal regulomes in human cancer and epigenetic therapy.

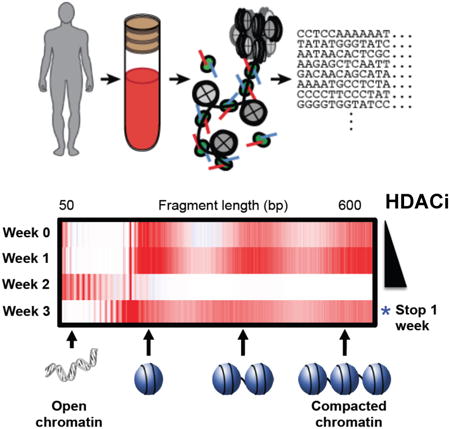

Graphical abstract

Qu et al. show that the accessible chromatin landscape distinguishes leukemic from host T cells in cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) patients as well as T cells from healthy individuals. The clinical response of CTCL to HDAC inhibitors strongly associates with a concurrent gain in chromatin accessibility.

Introduction

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) is a heterogeneous group of T cell neoplasms with primary involvement of the skin. Mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS) constitute the majority of CTCLs and is believed to originate from skin-tropic mature CD4+ T cells (Willemze et al., 2005). In the early stages, patients often have skin-restricted disease and in advanced stages of MF, the malignant T cells can involve the lymph node, viscera, and/or blood compartments. SS is the leukemic subtype of CTCL where patients present with generalized skin erythema. CTCL is the first clinical indication approved by FDA for treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi), such as vorinostat and romidepsin, highlighting the power of therapies that target the epigenome (New et al., 2012; Rodriguez-Paredes and Esteller, 2011). However, only a subset of CTCL patients (30-35%) respond to HDACi, and molecular and predictive biomarkers of clinical response to HDACi are needed. Despite CTCL being the first disease targeted by HDACi therapy, the landscape of CTCL epigenome in vivo and its response to therapy are not known. Moreover, it is appreciated that CTCL comprises a complex interplay between malignant T cells and the host immune system. The way in which CTCL reprograms host immunity and potential dynamic response of these interacting systems to therapy are unclear. Systematic analysis of the epigenomic landscape from primary clinical samples is needed to address these issues.

Assay of Transposase Accessible Chromatin with sequencing (ATAC-seq) is a recently introduced and sensitive method to map open chromatin sites, predict transcription factor binding, and determine nucleosome position from as few as 500 cells (Buenrostro et al., 2013; Lara-Astiaso et al., 2014; Lavin et al., 2014), or even in single cells (Buenrostro et al., 2015; Cusanovich et al., 2015). This technology enables clinicians to track the epigenomic state of patient-derived samples in real time and affords a “personal regulome”—a summary of gene regulatory events in a snapshot of time within a single individual (Qu et al., 2015). In this study, we developed a systematic approach to characterize chromatin dynamics in CTCL using ATAC-seq, and addressed the regulatory dynamics in leukemic epigenomes from CTCL patients treated with HDACi.

Results

Landscape of DNA accessibility in normal CD4+, CTCL leukemia, and host T cells

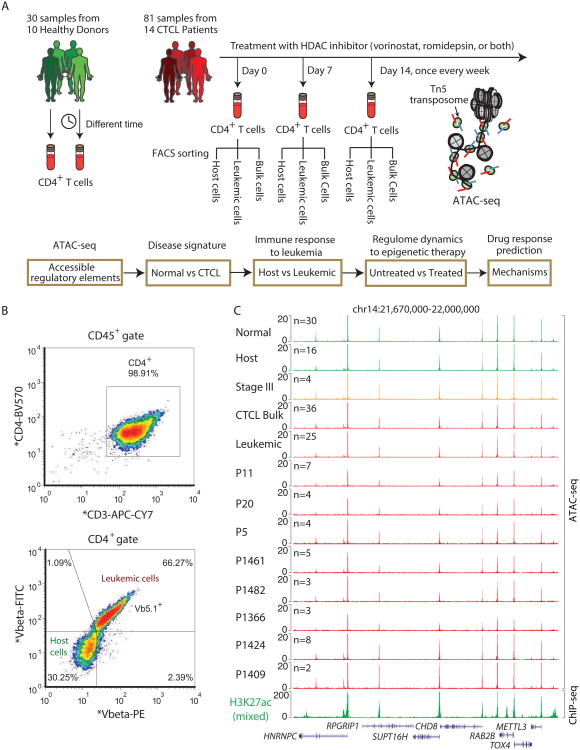

We generated and analyzed 111 high-resolution personal regulomes, 81 from 14 patients with CTCL and 30 from 10 healthy donors, of a single cell type—human CD4+ T cells—that comprised over 6 billion measurements (Figure 1A, Table S1). We interrogated the landscapes of chromatin accessibility in these samples and developed methods to integrate diverse sources of genomic and epigenomic information to address the regulatory dynamics in leukemic epigenomes from CTCL patients treated with HDACi (Figure 1A). 13 of 14 patients had Sézary syndrome, (stage IV, significant leukemic T cells); one patient had stage III MF, where the disease was not blood-predominant (Table S2). Because MF/SS is typically characterized by a dominant CD4+ T cell clone bearing a unique T cell receptor, we purified leukemic T cells from patients (defined by CD4+, CD26-, and T cell receptor V-beta clone+) vs. non-leukemic host CD4+ T cell (defined by CD4+, V-beta clone-) from the same patients by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) (Figure 1B). Thereafter, we refer to the non-malignant CD4+ T cells from CTCL patients as “host T cells”. Bulk CD4+ T cells were also obtained using RosetteSep Human CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Cocktail. Leukemic, host and bulk T cells were obtained from 9 out of 14 patients who had detectable V-beta clone, and only bulk T cells were obtained for the remaining 5 patients without detectable V-beta clone. Although number and proportion of leukemic and host T cells varies depending on the stage and drug response of each individual, we were able to obtain at least 50,000 CD4+ T cells per sample (Figure 1B). To provide additional comparative framework, we also analyzed 30 longitudinally-collected ATAC-seq profiles of CD4+ T cell obtained from 10 healthy donors (Qu et al., 2015).

Figure 1. Landscape of DNA accessibility in normal CD4+, CTCL, leukemic and host cells.

(A) Schematic outline of study design shows 30 samples from 10 healthy donors and 81 samples from 14 CTCL patients under HDACi therapy (Top), with bioinformatics pipeline for data analysis (Bottom). Host and leukemic cells were isolated from FACS based on CD3+CD4+Vβ- and CD3+CD4+Vβ+, respectively. ATAC-seq was then performed on normal CD4+, CTCL, leukemic and host cells.

(B) CD3+, CD4+, leukemic (Vβ+) and non-leukemic host (Vβ-) T cells sorted from FACS.

(C) Normalized ATAC-seq profiles at a locus in normal, host, stage III, bulk CTCL, and leukemic samples and bulk cells from individual patient, together with normalized H2K27ac ChIP-seq profile.

See also Figure S1, Tables S1 and S2.

We performed ATAC-seq to map the location and accessibility of regulatory elements genome-wide. Each library was sequenced to obtain, on average, more than 55 million paired-end reads (Table S1). With this dataset we identified a total of 71,464 peaks of DNA accessibility; visual inspection and quantitative analysis indicate this data are of high quality with strong signal to background ratio (Figure 1C). ATAC-seq signal in multiple patients aligned very well with the active enhancer mark histone H3K27ac (Spearman correlation = 0.68-0.77, p<10-10)(Limbach et al., 2016), indicating that detected regions of DNA are open and accessible. Correlation and clustering analysis of all the accessible sites recapitulate the group classification of the clinical samples—separating healthy donors, CTCL bulk, and leukemic and host cells (Figure S1). Interestingly, samples from the one patient with stage III MF clustered together with those from normal donors, in agreement with the clinical stage classification where malignant T cells in stage III MF are located predominantly in the skin or lymph node but not in the peripheral blood. Non-leukemic host CD4+ T cell samples also clustered together adjacent to normal T cell samples from healthy donors. These results demonstrate the feasibility of obtaining high quality epigenomic data from primary cancer samples using standard clinical infrastructure.

Epigenomic signatures of CTCL leukemic and non-leukemic host cells

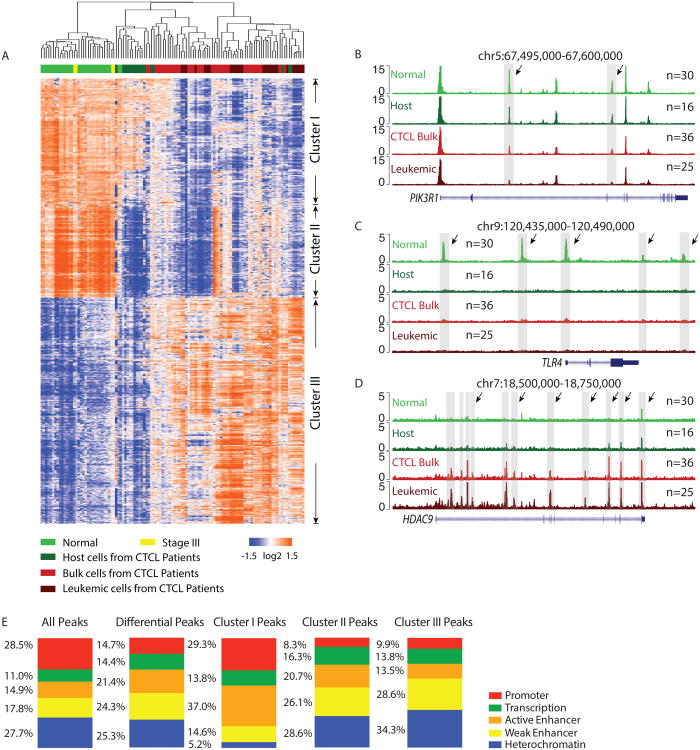

To identify differences in regulatory DNA activity among leukemic, host, bulk, and normal cells, we applied pair-wise comparison of the corresponding samples using DESeq. We discovered 7498 elements of differential DNA accessibility across the genome (Figure 2A). Known sites related to inter-individual variability among healthy donors (Qu et al., 2015) were removed from further consideration. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the differential peaks reveals three distinct clusters of regulatory elements, suggesting potential normal and leukemic epigenetic signatures that distinguish healthy, leukemic, and host T cells in CTCL patients.

Figure 2. Epigenomic signatures of CTCL leukemic and host cells.

(A) Heatmap of 7498 regulatory elements with differential activity. Each column is a sample; each row is an element. Samples and elements are organized by two dimensional unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Color scale shows relative ATAC-seq signal as indicated. Top: Samples were categorized into five groups, normal, stage III patient, host cells, bulk cells, and leukemic cells from CTCL patients. Samples from the same group are labeled with the same color.

(B, C, D) Normalized ATAC-seq profiles at the PIK3R1 (B), TLR4 (C), and HDAC9 (D) locus in normal, host, bulk CTCL and leukemic cells. Shaded regions are representative peaks in cluster I (B), II (C) and III (D), respectively.

(E) Distribution of genomic features of all, differential, cluster I, II and III regulatory element. 5 genomic features were studied, promoter, transcription, active enhancer, weak enhancer, and heterochromatin.

See also Figures S2 and S3.

We used GREAT to assess the genomic features that are enriched in each cluster of peaks (Figure S2). Cluster I comprised of 1995 elements that are more accessible in normal and host CD4+ cells compared to bulk and purified CTCL leukemic cells; these elements may reflect normal epigenomic signature of T cell homeostasis that is lost in the malignant T cells. GREAT analysis revealed that elements in this cluster are highly enriched in immune related gene ontology functions, immune system morphology, and hematopoietic system diseases (Figure S2, FDR<0.05 for each), suggesting they are critical for proper function of human T cells. Several signaling pathways are enriched in cluster I peaks such as IL-23-mediated (p=6.1E-12), NFAT-dependent (p=5.0E-10) and PDGF (p=6.1E-10) pathways, which have been reported in driving hematopoietic cancers including CTCL(da Silva Almeida et al., 2015). In addition, IL2 signaling pathway events mediated by PI3K (p=2.3E-8) was also found as significant, consistent with prior transcriptome analysis of Sézary syndrome which identified PI3K/AKT as the top dysregulated signaling pathway (Lee et al., 2012). Two intragenic elements in PIK3R1, encoding the regulatory subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase are up-regulated in healthy donor and non-leukemic host cells, and repressed in CTCL bulk and leukemic samples, exemplify elements in cluster I (Figure. 2B).

Cluster II comprised of 1696 elements that are highly accessible in CD4+ T cells from healthy donors, but are less accessible in both the leukemic and host non-leukemic cells. This behavior suggests these elements as a disease-specific signature, and identifies elements that are reprogrammed in host immune cells in leukemic patients. Prime examples of elements in cluster II include the promoter and several distal elements of gene TLR4 (Figure 2C). The protein encoded by this gene is a member of the Toll-like receptor (TLR) family, which plays a fundamental role in pathogen recognition and activation of innate immunity. Consistently, TLR4 mRNA is strongly expressed in normal CD4+ T cells and significantly down regulated in host cells and leukemic cells from CTCL patients (Figure S3A)(Lee et al., 2012; Quinn et al., 2015). Compared to cluster I enriched features, cluster II elements are enriched for more general immune functions which are not specific to lymphocytes or leukocytes (Figure S2), suggesting loss of accessibilities of peaks in cluster II may cause general immunodeficiency diseases, but not necessarily leukemia, which was regulated primarily by peaks in cluster I. Mouse phenotype and disease ontology analysis show that cluster II peaks are enriched in immune related diseases but none of which is specific to leukemic cells in SS (Figure S2). These results further indicate the generalized disease-relevant function of cluster II elements, however peaks in cluster I maybe the drivers for CTCL specifically.

Cluster III consists of 3807 elements, which are highly accessible in bulk CTCL and leukemic cells but not in host CD4+ T cells and normal cells from healthy donors. Cluster III may thus represent a leukemic signature associated with abnormal growth or differentiation. Gene ontology terms show that peaks in cluster III are highly enriched terms relevant with cell development and differentiation (Figure S2). Examples of Cluster III include multiple elements in the HDAC9 locus, encoding a histone deacetylase homolog that is a component of co-repressor complexes, that become strongly accessible in bulk and purified CTCL leukemia cells (Figure 2D), suggesting a signature of malignant T cells. HDACs regulate chromatin remodeling and gene expression as well as the functions of more than 50 transcription factors and nonhistone proteins. Transcriptome analysis shows that, among all the HDACs, HDAC9 is the only gene with significant differential expression between host and leukemic cells (Figure S3B) (Lee et al., 2012). It has also been reported that HDAC9 proved particularly important in regulating Foxp3-dependent suppression in Treg cells, and HDACi therapy in vivo enhanced Treg-mediated suppression of homeostatic proliferation, decreased inflammatory bowel disease through Treg-dependent effects (Tao et al., 2007). These results suggest the chromatin accessible elements on HDAC9 may play significant role in driving disease progression in this T cell malignancy.

We next checked the genomic distribution of all, differential and cluster peaks, by overlapping each peak list with regions of features in T cells defined in Epignomic Roadmap. Promoter and active enhancers are highly enriched in cluster I peaks suggesting these peaks may have greater influence on gene expression (Figure 2E).

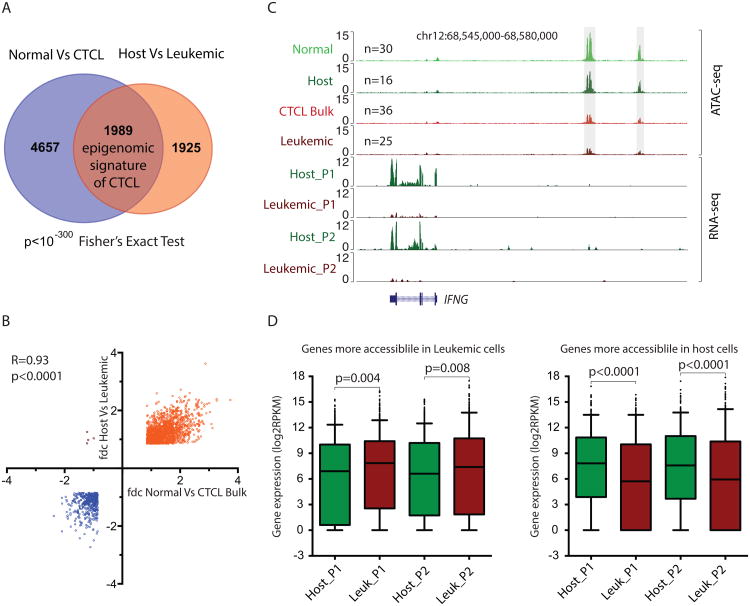

DNA accessibility change is correlated with differential messenger RNA expression in CTCL

We next examined whether the normal and leukemic chromatin signatures in DNA accessibility correlate with that of the gene expression. We purified host and leukemic cells from bulk T cells obtained from the CTCL patients using FACS, and performed chromatin accessibility analysis by ATAC-seq and compared with whole transcriptome analysis by RNA-seq for both cells. Accessible sites that are (i) differential between total CD4+ cells of healthy donor and CTCL patients, and (ii) also coordinately differential between leukemic and host CD4+ T cells purified from CTCL patients were defined as the “CTCL signature”. This analysis identified 1989 elements that represent the epigenomic signature of CTCL (Figure 3A, Figure S3C); 1557 elements are more accessible in normal and host cells; 432 elements more accessible in bulk CTCL and leukemic cells (Figure 3B). A quantitative comparison of each pair suggests the fold changes between normal and leukemic epigenomic signature are highly consistent.

Figure 3. DNA accessibility change is correlated with differential messenger RNA expression in CTCL.

(A) Overlap of differential peaks in normal versus bulk CTCL samples and differential peaks in host versus leukemic samples defines a leukemic signature.

(B) Scatter plot of the average fold change of the leukemic signature peaks in host versus leukemic cells versus that of normal versus CTCL bulk cells. Orange indicates peaks are more accessible in normal and host samples, and blue indicates those are more accessible in CTCL and leukemic cells. 4 outlier dots indicate peaks are more accessible in host cells and CTCL bulk cells.

(C) Normalized ATAC-seq profiles at the IFNG locus in normal, host, bulk CTCL and leukemic cells, and normalized RNA-seq profiles in host and leukemic cells from two individual patients at the same locus.

(D) Box plots (line in the box shows median, upper and lower border of the box indicate the upper and lower quartile, lines below and above the box indicate 5 and 95 percentile, data points beyond the limit of lines mean minimum to 5 percentile and 95 percentile to maximum) of mRNA expression levels in the leukemic and host cells from two CTCL patients, of the genes that are more accessible in leukemic cells (left) or host cells (right). p value estimated from Student t-test.

See also Figure S3.

The IFNG locus emerged as a prime example of intersection of predicted regulatory divergence in normal and leukemic cells (Figure 3C). IFNG encodes interferon gamma, a soluble cytokine that is secreted by cells of both the innate and adaptive immune systems, and is a key regulator of immune response and Th1 cell differentiation (Platanias, 2005). Interferon gamma is currently being used in combination therapy to treat CTCL patients (Jawed et al., 2014). We then ask whether the epigenomic profiling is generally correlated with gene expression. By comparing the genome-wide RNA-seq data in host vs. leukemic cells obtained from an independent study(Lee et al., 2012), we found that, on average, gene loci that gain ATAC-seq signal showed significant increase of gene expression level (p<0.008, Student T-test); gene loci that lose ATAC-seq signal also had decreased expression (p<0.0001, Student T-test) (Figure 3D), indicating a high correlation of epigenetic and RNA profiling.

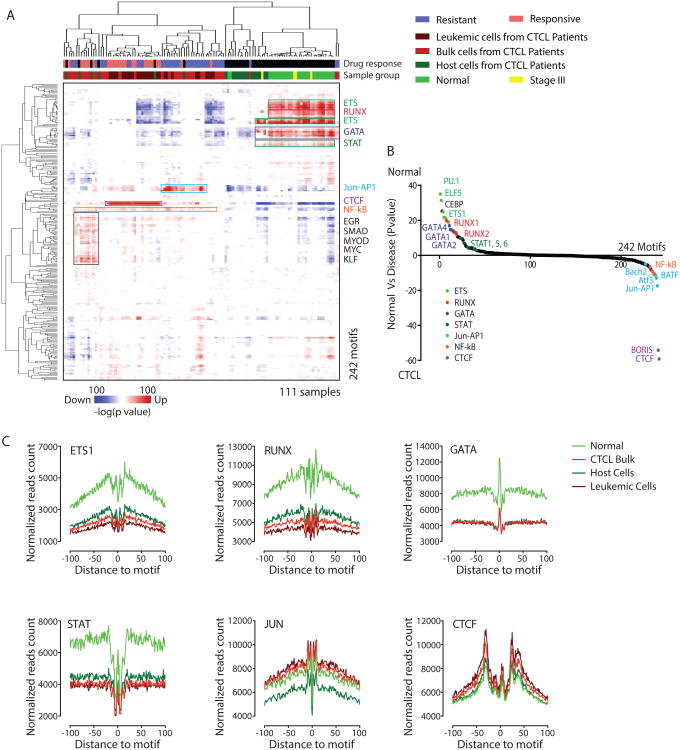

Transcription factor occupancy networks in CTCL

One of the main advantages of the ATAC-seq is that this technology can potentially inform the transcriptional regulatory network in the disease. Because transcription factor (TF) binding to their cognate DNA sequences, termed motifs, often obligates nucleosome eviction and creation of an accessible DNA site, integration of known TF motifs with DNA accessibility data from ATAC-seq can predict a genome-wide regulatory network in any state of interest (Qu et al., 2015). We applied this analytical technique to identify CTCL-specific differences in gene regulatory network from ATAC-seq data. We first obtained a total of 242 vertebrate TF motifs from Jasper database (Mathelier et al., 2016), identified their genome-wide distribution using HOMER and overlaid these sites with differential ATAC-seq peaks in Figure 2A. We then used Genomica to select statistically significant motifs that are enriched or depleted in each sample, producing a patient specific regulatory network (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Transcription factor occupancy networks in CTCL.

(A) Enrichment of known transcription factors' motifs in differential accessible elements for all the samples. Each row is a motif and each column is a sample. Values in the matrix indicate the significance, in terms of −log(p value), of the enrichment estimated from Genomica. Top ranked motifs were annotated on the right. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was performed. Top: first color bar indicates whether a sample was drug responsive or resistant; second color bar indicate the category of each sample, normal, host cells, stage III, bulk CTCL cells, leukemic cells.

(B) Ranking of the most differential motifs between normal versus disease samples. The top ones were the most enriched motifs in normal samples and the bottom ones most enriched in disease samples.

(C) Visualization of ATAC-seq footprint for motifs ETS1, RUNX, GATA, STAT, JUN and CTCF, in normal, host cells, bulk CTCL cells and leukemic cells. ATAC-seq signal across all these motifs' binding sites in the genome were aligned on the motif and averaged.

Our analysis revealed distinct patterns of TF access of DNA in CTCL and host cells (Figure 4A, B). In bulk CTCL and purified leukemia samples, we observed nearly uniform activation of NF-κB, together with activation of one of three TF motif patterns: (i) Jun-AP1, (ii) CTCF, or (iii) a motif set that includes EGR, SMAD, MYC, and KLF. Each CTCL sample showed NF-κB activation, but the three companion TF motifs are coordinately enriched in only a subset of CTCL samples and appeared mutually exclusive, indicating the transcriptional logic of CTCL can be patient specific. These results may highlight the core transcriptional circuitry in CTCL. The broad activation of NF-κB is consistent with the recent discovery in CTCL of activating somatic mutations in TNF receptor 2, downstream signaling components and NFKB2 itself that activates NF-κB activity (Choi et al., 2015; Ungewickell et al., 2015). NF-κB and c-Jun are onco-proteins that regulate many types of cancers including CTCL (Woollard et al., 2016), suggesting that our unbiased results are consistent with previous discoveries. In contrast, the primary role of CTCF is thought to be in regulating the 3D structure of chromatin (Phillips and Corces, 2009); dysregulation of chromosome neighborhoods can also cause cancer through altered gene expression(Flavahan et al., 2016). Regulators with CTCF like motif have been reported in regulating leukemia and other cancers (Dolnik et al., 2012; Yoshida et al., 2013), and CTCF mutations were noted in a subset of CTCLs (Choi et al., 2015). Finally, one of the most interesting discoveries is that motif patterns could be associated with patients' drug response. We noticed 89.5% of samples (17 out of 19) enriched with CTCF were from patients subsequently responsive to the HDACi romidepsin and 88.2% of samples (15 out of 17) enriched with Jun-AP1 were from patients resistant with HDACi drugs. While our sample set is not sufficiently powered to address this question, this initial observation suggests patient specific regulome may inform drug response.

Conversely, DNA access at TF motifs for ETS, RUNX, GATA, and STAT are strongly enriched in normal CD4+ T cells but are lost in both leukemic and host non-leukemic CD4+ T cells. These TFs are involved in a wide variety of functions including the regulation of cellular differentiation, cell cycle control, cell migration, cell proliferation, apoptosis and angiogenesis (Sharrocks, 2001). For example, the STAT transcription factor family is well known in mediating many aspects of cancer inflammation and immunity(Yu et al., 2009). STAT3 activation restrains antitumor immune responses by antagonizing NF-κB and STAT1-mediated expression of anti-tumor T helper 1 (Th1) cytokines such as IL-12 and interferon-gamma (IFNγ), which are necessary for both innate and T cell-mediated antitumor immunity (Yu et al., 2009). It is notable that the depletion of ETS/RUNX/GATA/STAT activity occurred in both purified leukemic cells and host CD4+ cells from CTCL patients (Figure 4A). This result suggests that there is broad reprogramming of T cell homeostasis in CTCL patients that is shared in the leukemic compartment and host immune response. Quantitative ranking of TF motif enrichments between normal and disease samples largely recapitulated the dominant regulators identified above (Figure 4B). We found ETS, CEBP, RUNX, GATA and STAT are the top motifs enriched specifically in normal T cells but not CTCL, while CTCF, Jun-AP1, NF-κB, and BATF are the top motifs specifically activated in CTCL.

Analysis of our ATAC-seq revealed the “TF footprint” on genomic DNA directly from clinical CTCL samples and primary human T cells (Figure 4C). DNA sequences that directly occupied by DNA-binding proteins are protected from transposition, analogous to DNase digestion footprints. For the most differential motifs in normal vs disease comparisons, we observed their footprints under each condition (Figure 4C). We found TFs enriched in normal T cells, such as ETS1, RUNX, GATA and STAT, show deeper “footprints” and higher DNA accessibility flanking their motifs in normal cells compare to leukemic cells. In contrast, the “footprints” of the TFs enriched in leukemic cells, such as JUN and CTCF, show the opposite trend. The degree of TF footprint loss is greater than that of footprint gain of the respective TFs. Collectively, the results from the orthogonal footprint analysis are consistent with the motif enrichment analysis using Genomica.

Personal chromatin dynamics with HDACi treatment

HDACi (here vorinostat and romidepsin) are thought to induce therapeutic effects in cancer by modulation of gene expression--particularly induction of tumor suppressor gene--by increasing histone acetylation and DNA accessibility. However, only a subset, ∼43% (6 out of 14 included in this study) of CTCL patients demonstrates clinical response to HDACi, while other patients with similar disease by stage and existing molecular criteria are resistant. The basis for this therapeutic heterogeneity is not known. HDACi treatment is currently given without any ability to visualize its impact on CTCL epigenome or on gene transcription. We profiled personal regulomes of HDACi treatment in real time in order to evaluate ahead of time the potentially optimal therapeutic approach, before major changes in cell composition. We focused our analysis on patients who showed eventual clinical response to HDACi to those who did not (“non-responders” thereafter); the latter may have stable disease vs. progressive disease, which we do not have sufficient power to distinguish on a molecular level at present.

We found that clinical response to HDACi is correlated with a dynamic change in CTCL DNA accessibility. Patients with clinical response in the blood compartment showed global increase of DNA accessibility during HDACi treatment, while patients resistant to HDACi did not (Figure S4A). We found 62%, 5%, and 33% of cluster I, II and III peaks defined in Figure 2A, respectively, were responsive to romidepsin in CTCL patients (Figure S4B). The romidepsin-responsive peaks in cluster I are enriched in immune relevant GO terms (Figure S4C), suggesting T cells were activated during drug treatment and turning leukemic cells towards normal.

We plotted the CTCL leukemic count versus the DNA accessibility (defined as the RPKM normalized ATAC-seq reads count of all peaks) of their bulk CD4+ T cell, before and during HDACi therapy for all the available patients. We separated patients into two groups, those treated with vorinostat or romidepsin. Patients that did not respond to HDACi, such as P11 on vorinostat or P1409 on romidepsin, showed negligible changes in DNA accessibility (Figures 5A, 5B). The CTCL counts of patients P20 and P5 actually increased while on vorinostat treatment over 4 weeks, and the chromatin accessibility significantly decreased (Figure 5A). In contrast, when patient P11 was subsequently treated with romidepsin and had CTCL count reduction of almost 30%, the ATAC-seq profile showed significant increase in DNA accessibility. Similar results were also observed on patient P1461 (Figure 5B). These results suggest that the dynamics of the chromatin accessibility during HDACi treatment can be patient-specific and may predict clinical outcome. Summarizing our entire set of patients, we found that the decrease in CTCL count in response to HDACi is strongly correlated with the quantitative gain of in DNA accessibility as measured by ATAC-seq (Figure 5C). These results suggest that CTCL patient's clinical response to HDACi is associated with a specific and dynamic pattern of chromatin decompaction.

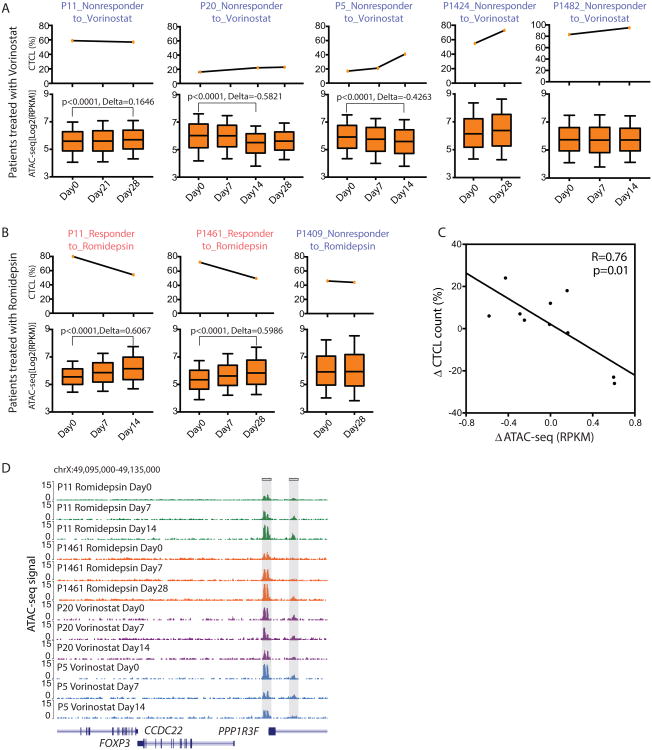

Figure 5. Personal chromatin dynamics with HDACi treatment.

(A, B) Percentage of CTCL counts (Top) and chromatin states indicated by ATAC-seq signal (Bottom) of patients during vorinostat (A) or romidepsin (B) treatment from 0 to 5 weeks. Box plot: line in the box shows median, upper and lower border of the box indicate the upper and lower quartile, lines below and above the box indicate 10 and 90 percentile. Clinical responders were colored in pink, and nonresponders were colored in dark blue. p values were estimated from Student T-test. Delta means the average RPKM fold change between a treated state versus untreated state (Day0).

(C) Dot-plot of delta percentage of CTCL counts versus delta ATAC-seq signal in the form of RPKM. Solid line was fit from liner regression, and p value and correlation R were estimated from Pearson Correlation analysis.

(D) Normalized ATAC-seq profiles at the FOXP3 locus of patients P11, P1461, P20 and P5 at different time points during HDACi treatment. Shaded regions are peaks identified gradually opened up during the HDACi treatment for responsive patients (P11 and P1461), and kept unchanged or even closed up for resistant patients (P20 and P5).

See also Figures S4, S5, and S6.

Several notable genes demonstrate HDACi-responsiveness in CTCL patients. FOXP3 is a master regulator of the regulatory pathway in the development and function of Treg cells (Fontenot et al., 2003; Fontenot et al., 2005; Hori et al., 2003). For responsive patients P11 and P1461, two FOXP3 enhancers were gradually opened up during the drug treatment, while that of the other two drug resistant patients P20 and P5, kept unchanged or even closed up, suggesting FOXP3 might be a critical regulator in drug response (Figure 5D). As another example, IFIT3 is an interferon-induced protein that is up-regulated in pancreatic and hypopharynx cancers (Niess et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2013). Figure S4D show how its enhancer became accessible during drug treatment in clinical responders but remained unchanged or even compacted in clinical non-responders.

We also investigated whether HDACi induced DNA accessibility around tumor suppressor genes anticipated HDACi therapeutic effect. In HDACi responders (e.g. P11 and P1461 on romidepsin), many elements flanking tumor suppressor genes became accessible during drug treatment, while in non-responders DNA accessibility of tumor suppressors actually decreased (Figure S5A). The promoter of TP53, a well-known tumor suppressor gene, illustrates this dynamic selectively in HDACi responders (Figure S5B).

Furthermore, we adapted a previously described Hidden Markov Model analysis tool ChromHMM (Ernst and Kellis, 2012) to check which chromatin states in primary T cells were enriched in the top 5000 altered sites under vorinostat and romidepsin therapy. This analysis revealed that peaks mostly altered under romidepsin treatment were highly enriched in promoters and active enhancers compared that with vorinostat (Figure S6), suggesting peaks altered by romidepsin may have greater influence on gene expression.

Enhancer cytometry and cell-type specific response to HDACi therapy

CD4+ T cells are heterogeneous, and consist of multiple subtypes, including naive and memory T cell populations. Memory CD4+ T cells can be further divided based on their differentiation into cytokine-polarized T helper 1 (Th1), Th2, Th17, and T regulatory (Treg) cells. We recently developed “enhancer cytometry” wherein we can accurately enumerate the frequency of cell types in complex cellular mixtures based on DNA accessibility data (Corces et al., 2016), and we applied this method to deconvolve the composition of subtypes of T cells in normal and CTCL samples, including purified leukemic and host cells from CTCL patients (Figure 6A).

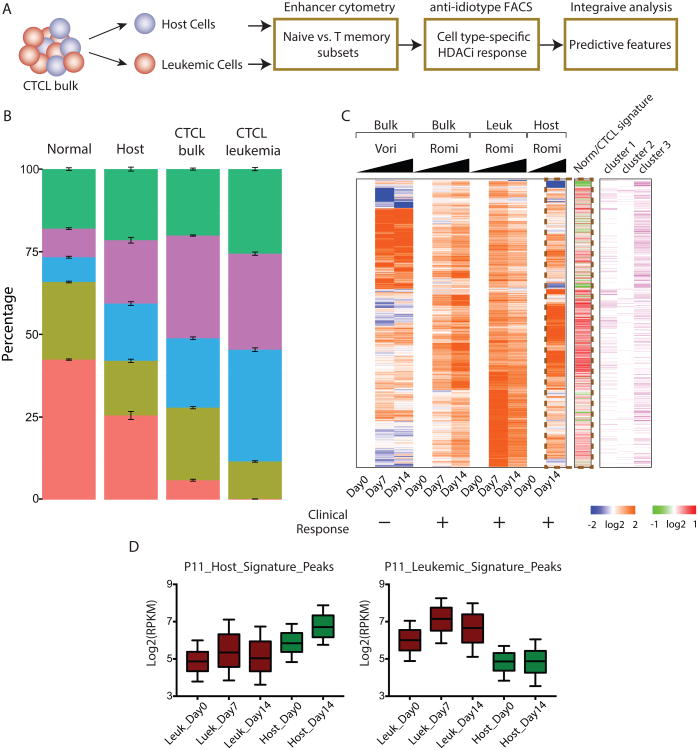

Figure 6. Enhancer cytometry and cell-type specific response to HDACi therapy.

(A) Schematic outline of study design of cell-type specific response to HDACi therapy.

(B) Enhancer cytometry analysis from CIBERSORT using T subtype cell ATAC-seq signature as eigenvectors to evaluate the T subtype cell composition in mixture of normal, host, CTCL and leukemic cells. Error bars represents standard error of mean (SEM) from all the samples in each category. Each T subtype cell was colored differently.

(C) Left: heatmap of relative fold changes of treated states versus their corresponding untreated states (Day0) of the top 5000 altered peaks in patient P11 treated with vorinostat or romidepsin as indicated. Middle: average fold change of the corresponding peaks in normal versus CTCL samples. Right: whether a corresponding peak belongs to cluster I, II or III defined in Figure 2A. Time points at the bottom indicate when samples were ATAC-seqed. + means clinical responsive and – means resistant.

(D) Box plots (line in the box shows median, upper and lower border of the box indicate the upper and lower quartile, lines below and above the box indicate 10 and 90 percentile) of host signature peaks (left) and leukemic signature peaks (right) in leukemic (dark red) and host (dark green) cells of patient P11 under treatment with romidepsin.

See also Figure S7.

We first isolated human blood naive and memory Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg cells using FACS and performed ATAC-seq to determine the landscape of chromatin accessibility of each cell type in healthy subjects. We then compute the contribution of each signature to aggregate leukemic cell profiles. Interestingly, bulk CTCL and leukemic samples demonstrated a significantly lower percentage of naive T cell and concomitant increase in memory T cell compared with normal or host cells, indicating that CTCL cells are highly similar to memory T cells at the epigenomic level (Figure 6B). Further fractionation of memory T cell profiles showed that CTCL cells demonstrate an increase in Th2 and Treg profiles relative to normal cells. An excess of Treg cells in cancer patients can prevent the immune system from destroying cancer cells (Josefowicz et al., 2012), and the adoption of a Treg-like regulome in CTCL cells may facilitate evasion of anti-tumor immunity. In host T-cells of CTCL patients, Th1 frequency is reduced and Th2 frequency is increased (Figure 6B). This result suggests the balance of T cell homeostasis is disrupted in CTCL patients, either directly or indirectly, with the repression of Th1 cell signature and enrichment of Th2 signature. This observation is also consistent with the down-regulation of IFNG (Figure 3C), which is a key effector in Th1 cell differentiation and anti-tumor immunity(Platanias, 2005).

We next sought to deconvolute the composition of host and leukemic cells in bulk CTCL samples. As a positive control, enhancer cytometry reported that host cells were predominant in purified host samples, and leukemic cells were dominant in purified leukemic samples, as expected (Figure S7). Enhancer cytometry of bulk CD4+ T cells from patients P11 and P1424 was also consistent with their clinical course (Figures 5A, 5B), independently confirming the findings from flow cytometry based on a small number of cell surface markers (Figure S7).

An important question in epigenetic therapy of cancer is the target cell identity. Is it the leukemic cells, the non-malignant host CD4+, or both that are altered in response to HDACi? Patient P11 provides a case study. P11 was treated with vorinostat with no clinical response, and then treated with romidepsin with positive response. We were able to obtain ATAC-seq profiles from bulk CD4+ cells during vorinostat treatment, and bulk, purified leukemic and host CD4+ cells during romidepsin treatment. Visualizing the top 5000 most differentially altered elements in DNA accessibility illustrated three key points (Figure 6C). First, the chromatin accessibility landscape of P11 responded differently to vorinostat vs. romidepsin, indicating drug-specific molecular effects. Second, romidepsin induced distinct patterns of DNA accessibility in leukemic vs. host CD4+ T cells (Figure 6C). Intriguingly, the HDACi-induced change in host CD4+ T cells was much more correlated with the chromatin signature that distinguishes normal vs. CTCL cells (Pearson correlation 0.36 for host cells and -0.04 for leukemic cells), suggesting the host CD4+ cells may be more relevant in HDACi's ability to normalize the chromatin state in CTCL patients (Figure 6C, dotted box). Third and most importantly, we observed that a baseline state of DNA accessibility appears to predict the elements that respond to HDACi. When we compared the romidepsin response to the three clusters of DNA elements that distinguished normal, host CD4+, and CTCL cells (defined in Figure 2A), we observed that, in CTCL cells, romidepsin increased DNA accessibility in cluster III elements, which are more accessible in CTCL than normal or host cells. Similarly in host CD4+ cells, romidepsin increased accessibility more in cluster I elements, which are accessible in normal and host CD4+ cells but lost in CTCL. This same point is reinforced by quantitative analysis of DNA elements that are differentially accessible in leukemic cells or host cells (Figure 6D). Host signature elements have higher accessibility in host cells than CTCL cells at baseline (as expected), and host elements increased accessibility in response to romidepsin only in host cells but not leukemic cells. Conversely, leukemic signature elements have higher accessibility in leukemic cells than host cells, and romidepsin treatment increase their accessibility in leukemic but not host cells (Figure 6D). In other words, HDACi accentuate the existing pattern of DNA accessibility in each given cell type, rather than switch on inaccessible sites in either CTCL or host cells.

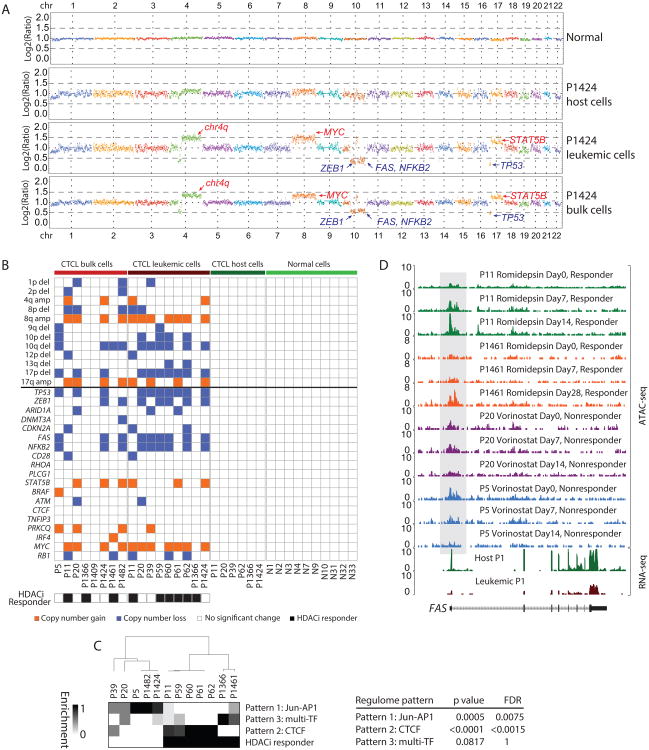

Integration of genomic and epigenomic landscapes in CTCL

Genome and exome sequencing of CTCL and Sézary syndrome discovered chromosomal copy number variations (CNV) in patients with the diseases(Almeida et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2015). We used a method to detect chromosomal CNV from ATAC-seq background reads(Denny et al., 2016), and integrated genomic and epigenomic analyses in CTCL. For each sample, we pinpointed the genomic amplifications and deletions from ATAC-seq, which recapitulated chromosomal CNVs such as 10q and 17p deletion and 8q and 17q amplification, confirms discoveries from exome and whole genome DNA sequencing (Almeida et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2015)(Figures 7A, 7B). Recurrently mutated genes in CTCL, such as FAS, MYC, NFKB2, STAT5B, and TP53 were also discovered (Figures 7A, 7B). In addition, we integrated the chromatin accessibility profile and response to HDACi for each sample with genomic CNV. We found that none of the CNVs can predict clinical response to HDACi (FDR>0.05), but in contrast, the chromatin regulome profile significantly predicted HDACi response (p<0.05, FDR<0.05, Chi-Square Test, Figure 7C). Presence of the CTCF pattern and absence Jun-AP1 pattern are both predictive of HDACi response. At the level of individual genes, FAS encoding a cell surface death receptor whose expression in tissue culture experiments has been proposed to explain the efficacy of epigenetic therapy in CTCL(Wu and Wood, 2011). However, we found genomic deletion of FAS locus is not sufficient to predict HDACi clinical response (Figure 7B), because only a subset of patients with intact FAS locus de-repressed the gene upon HDACi. We show that HDACi can indeed increase chromatin accessibility at FAS promoter in CTCL from human patients, and each patient that had increased chromatin accessibility at FAS experienced subsequent clinical response to HDACi (Figure 7D). These results highlight the unique prognostic and mechanistic insights that are potentially gained by integration of genomic and epigenomic analysis of CTCL.

Figure 7. Integration of genomic and epigenomic landscape in CTCL.

(A) Human chromosomal diagram showing the areas of DNA copy number gain and loss identified by ATAC-seq in normal (donor 1) and host, leukemic and bulk cells from patient P1424. Selected implicated driver genes are shown.

(B) Distribution of recurrent chromosomal (Top) and gene (Bottom) copy number variants in CTCL patients (bulk, leukemic, and host cells) and normal donors. Orange boxes indicate copy number gain, blue boxes copy number loss, and white boxes no significant change. Patients with black boxes are HDACi drug responders.

(C) Association of CTCL regulome pattern discovered in Figure 4A and HDACi response. Left: two dimensional unsupervised hierarchical clustering of patients based on their enrichment of each regulome pattern. Right: association of CTCL regulome pattern and HDACi response, p value estimated from Chi-Square Test, and FDR from Bonferroni correction.

(D) Normalized ATAC-seq profiles at the FAS locus of patients P11 (green), P1461 (orange), P20 (purple) and P5 (blue) at different time points during HDACi treatment. Shaded regions are peaks identified gradually opened up during the HDACi treatment for responsive patients (P11 and P1461), and kept unchanged or even closed up for resistant patients (P20 and P5). Normalized RNA-seq profiles in host and leukemic cells from patient 1 at the same locus are also shown.

Discussion

Here we surveyed the landscape of active regulatory DNA in CTCL using the sensitive method of ATAC-seq. Because only ∼1% of the human genome is accessible in any given cell type, the identity and pattern of DNA accessibility is highly informative of cell identity, activity state, and regulatory programs. In CTCL, we found distinct patterns of DNA accessibility in both leukemic and host CD4+ T cells that differ from CD4+ T cells in healthy individuals. These DNA elements are coordinately associated with genes that intimately control T cell growth, immunity, and homeostasis, adding to the concept that CTCL is both a neoplasm and a systemic disease that alters host immune functions.

In CTCL, the gene regulatory network is altered with nearly ubiquitous activation of the NF-κB, plus one of three mutually exclusive sets of DNA bindings factors Jun-AP1, CTCF, and a set of TFs that includes MYC. Because inhibitors to several of these factors or their upstream regulators have been developed, such as JNK inhibitors (Zhang et al., 2012), Aza-C for CTCF (Flavahan et al., 2016), or BRD4 inhibitors for Myc deactivation (Filippakopoulos et al., 2010), knowledge of the dominant regulators in each patient sample may afford rational matching of patients to targeted therapies. In host CD4+ T cells, we found systemic deactivation of programs that confer immune functions driven by STAT, GATA, ETS, and RUNX factors. The net effect of these regulatory perturbations is an expansion of memory Treg and Th2 regulomes in CTCL leukemic cells and host cells, at the expense of naive T cells and Th1 subsets.

The nearly complete loss of naive regulome signatures in leukemic cells suggests that CTCL may derive from founder memory T cell clones. Since memory T cells are long-lived and share self-renewal properties with hematopoietic stem cells, these data may indicate a model of lymphoma evolution that mirrors the process observed in myeloid leukemia(Corces-Zimmerman et al., 2014; Jan et al., 2012). Namely, memory T cells may serve as a reservoir for the accumulation of cancer-causing mutations, which eventually lead to frank lymphoma. Our findings using DNA accessibility and enhancer cytometry are consistent with extensive literature on immune profile of CTCL(Dulmage and Geskin, 2013), and are advantageous in that multiple insights--including TF drivers not available from previous assays—can be learned from a single regulome profile. Personal regulome analysis of acute myeloid leukemia has identified prognostic features and therapeutic targets (Corces et al., 2016; Mazumdar et al., 2015), our results with CTCL further demonstrates the feasibility and potential insights from application of cutting edge epigenomic technology on patient samples for precision medicine.

Despite the fact that CTCL is the first clinical indication that led to the approval of HDACi for human use, the chromatin dynamics of CTCL patients being treated with HDACi are not known. We combined CTCL purification, based on the clonal T cell receptor V-beta idiotype, and ATAC-seq profiling to track CTCL patients throughout treatment with HDACi vorinostat or romidepsin. We were fortunate to identify an illustrative patient who had a positive clinical response to romidepsin and whose CTCL had a V-beta clone that we were able to sort and purify. Our results held two surprises that ran contrary to the conventional thinking of epigenetic treatment of cancer. First, we found that the HDACi romidepsin had profound effects on the DNA accessibility of CTCL and host CD4+ T cells, and it was the change in host T cells that was more aligned with normalizing the chromatin signature toward normalcy. Thus, the host immune system may be equally important as the cancer cell for epigenetic therapy. Recent studies of EZH2 and DNA methyltransferase inhibitors have shown an important role of de-repressing host immunity against cancer in preclinical models (Chiappinelli et al., 2015; Peng et al., 2015). Our results in CTCL patient are consistent with this concept and suggest HDACi as another possible agent to manipulate host immunity in cancer.

Second, we found that clinical response to HDACi is associated with a global increase in CTCL DNA accessibility, and HDACi appears to accentuate the status quo pattern of DNA accessibility rather than evoke new accessible elements. In our patient series, clinical response segregated with vorinostat vs. romidepsin. It is unclear whether a higher dose of vorinostat could have induced DNA accessibility or clinical response. Nonetheless, HDACi therapy is currently given in a set regimen without evaluating the effect on CTCL chromatin state. Functional feedback on the therapeutic target, as is currently practiced for measuring blood culture for antimicrobial therapy or clotting time for dosing anti-coagulation therapy, greatly improves the precision and likelihood of reaching the therapeutic goal. Our findings provide the rationale for potentially monitoring the chromatin state of cancer cells and host cells during epigenetic therapy of cancer. Moreover, we found that existing accessible elements, rather than dormant tumor suppressor genes or off-lineage regulators, are preferentially induced by HDACi therapy in CTCL and host cells. This finding may explain the observation that restoration of host immunity occurs with HDACi therapy. Our results are based on a small number of observations, and thus should be evaluated for replication in additional patients in future studies.

Star Methods

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact Howard Y. Chang at howchang@stanford.edu

Method Details

Patients

Following informed consent per the Declaration of Helsinki, Sézary syndrome (SS) patient samples were collected under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University Medical Center. Patient characteristics are described in Table S2. All samples were obtained from patients with either clinical stage III or IV MF or SS. All diagnoses were confirmed by a board-certified dermatopathologist. Clinical staging and assessment of response to treatment are as defined by CTCL international consensus criteria (Olsen et al., 2011).

Cell isolation

Normal donors were recruited under a Stanford University IRB-approved protocol. Informed consent was obtained. Standard blood draws in green-top tube were obtained for each time point. 1-5mL of whole blood was enriched for CD4+ cells using RosetteSep Human CD4+ T Cell Enrichment Cocktail (StemCell Technology) as described (Buenrostro et al., 2013). PBMCs were prepared by Ficoll-Hypaque density-gradient centrifugation. PBMCs were stained with fluorochrome-labeled anti–human monoclonal antibodies (Biolegend Inc) to CD45 (clone HI30), CD4 (clone RPA-T4), and CD3 (clone HIT3a). T-cell receptor (TCR) Vβ clonality was determined with the TCR Vβ Repertoire Kit (Beckman-Coulter). Antibody-stained patient lymphocytes were sorted into CD3+CD4+Vβ+ and CD3+CD4+Vβ- fractions with the use of an Influx flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson) (Dummer et al., 1996). At least 50,000 CD4+ T cells were enriched by negative selection without ex vivo expansion. For CD4+ T helper cell subtypes, cells were sorted as previously described(Morita et al., 2011). Briefly, naive cells were sorted as CD4+CD25-CD45RA+, Th1 cells as CD4+CD25-CD45RA-CXCR3+CCR6-, Th2 cells as CD4+CD25-CD45RA-CXCR3-CCR6-, Th17 cells as CD4+CD25-CD45RA-CXCR3-CCR6+, and Treg cells as CD4+CD25+CD127lo. >95% post-sort purities were confirmed prior to ATAC-seq.

ATAC-seq

ATAC-seq was performed as described(Buenrostro et al., 2013), and 2×50 paired-end sequencing performed on Illumina NextSeq500 to yield on average 55M reads/sample.

Primary data processing and peak calling

Adapter sequences trimming, mapping to Hg19 using Bowtie2(Langmead and Salzberg, 2012) (with option --very-sensitive), and PCR duplicate removal were as described(Buenrostro et al., 2013). Mapped reads were shifted +4/-5bp depending on the strand of the read, so that the first base of each mapped read representing the Tn5 cleavage position. All mapped reads were then extended to 50bp centered by the cleavage position. Reads mapped to repeated regions and chromosome M were removed. Peak calling was performed using MACS2 (Zhang et al., 2008) with options -f BED, -g hs, -q 0.01, --nomodel, --shift 0. Peaks in each sample were called for QC purpose. Samples were then grouped into 5 categories, Normal, Host, Stage3, BulkCTCL and Leukemic. Reads from the same category were concatenated, on which peak calling was performed using the same options. Peaks in each category were further filtered, and high quality peaks with FDR<10E-7 were obtained. Peaks for all the categories were then merged together into a unique peak list, and number of raw reads mapped to each peak at each condition was quantified using intersectBed function in BedTools (Quinlan and Hall, 2010). Peak raw counts were quartile normalized using DESeq(Simon Anders, 2010) package in R. Peak intensity was defined as log2 of the normalized counts. After these steps, an N×M data matrix was obtained where N indicates the number of merged peaks, M indicates the number of samples, and value Di,j indicates the peak intensity of peak i (i=1 to N) in sample j (j=1 to M). For each pairs of samples, Pearson correlation was calculated based on the log2 normalized counts of all the peaks. Unsupervised correlation of the Pearson correlation matrix was performed using Cluster 3.0 (de Hoon et al., 2004), and visualized in Java Treeview.

Data quality control

ATAC-seq data quality measure was comprehensively studied in our previous work (Qu et al., 2015). The ability of using ATAC-seq to detect accessible sites was proved by comparing ATAC-seq signal with DNaseI hypersensitivity sequencing (DHSseq), which serves as a gold standard assay and positive control for open chromatin. We found that ATAC-seq was highly reproducible between replicates. From an irreproducibility discovery rate (IDR) analysis(Landt et al., 2012), which was an ENCODE-specified method to evaluate data reproducibility across replicates, we found that the number of reproducible peaks plateau between 11-12 million mappable reads, irrespective of the IDR cutoff (Qu et al., 2015). In this study, we have on average 26 million uniquely mapped reads (Table S1), suggesting the sequencing in this study was deep enough to confidently capture the majority of the regions of interest. We then using several metrics to evaluate the quality of each sample, including the number of raw reads, overall alignment rate, final mapped reads, final mapped rate, percentage of reads mapped to chrM, percentage of reads mapped to repeat regions (black list), percentage of reads filtered out by low MAPQ score, percentage of PCR duplicates, TSS enrichment score (reads that enriched at +/-2kb around TSS versus the background), read length distribution and number of peaks (Table S1). We then end up with 111 high quality samples.

Significance analysis

Samples were grouped into 5 categories, Normal (30 samples), Host (16 samples), StageIII (4 samples), CTCL Bulk (36 samples) and CTCL Leukemic (25 samples). Data normalization and significant analysis was performed by pair-wise comparing the 5 categories using DESeq (Simon Anders, 2010), with p value < 0.01, FDR < 0.01, log2 fold change > 1, peak average log2 intensity > 4, and standard deviation < 2. With that we obtained 7498 differential accessible peaks. Unsupervised clustering was performed using software Cluster 3.0 and visualized in Treeview. The ATAC-seq signal in each category was normalized by sequencing depth. Significant analysis on Normal versus CTCL Bulk and Host versus Leukemic was also performed in DESeq with same cutoffs. Gene ontology and other enriched functions of cis-regulatory regions were predicted using GREAT(McLean et al., 2010).

Genomic segmentation analysis

Genomic location classification was defined by chromHMM in Epigenomic Roadmap Consortium (Roadmap Epigenomics et al., 2015) on Naïve T cells. A chromHMM 25-state classification was then combined to 5 states, promoter, transcription, active enhancer, weak enhancer and heterochromatin. All merged peaks, differential peaks and peaks in each cluster in Figure 2A were then overlaid with these 5 genomic segments, e.g. if the center of a peak resides in promoter, then this peak was assigned to promoter, and same for all the other segments.

Integrative analysis of chromatin accessibility (ATAC-seq) and gene expression (RNA-seq) profiles

We analyzed public datasets from a transcriptome analysis of Sezary syndrome (Lee et al., 2012) to validate the positive correlation between the ATAC-seq signals with the mRNA expressions of the genes nearby. Nearby genes were defined from GREAT (McLean et al., 2010). RNA-seq reads were aligned to the human reference sequence National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) build GRCh37/hg19 with TopHat (Trapnell et al.). A combination of RefSeq, UCSC genes, and Gencode databases were used as reference annotations. Multiple isoforms of a same gene were collapsed so that only values of fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads of each gene were calculated with a self-developed script (K.Q.). Boxplot of gene expression difference in Figure 3D was performed using Prism 7, and p values were estimated from Student T-test.

Regulatory network and TF footprinting analysis

Input motifs set was obtained from jaspar (http://jaspar.genereg.net/) on vertebrates. We searched for input motifs in each significant differential peak using HOMER (Heinz et al., 2010), and generated a peak versus motif matrix, where each row is a peak and each column is a motif. Value 1 in the matrix represents this motif is found in the peak and value 0 represents NOT. From peak significant analysis, we had a peak by sample matrix where each row is a peak and each column is a sample, and values in the matrix represent the peak intensity in the corresponding sample. We then mean-centered the values in each peak to obtain the relative fold changes of each peak across all the samples. By integrating this two matrixes into Genomica (Segal et al., 2004), using the ModuleMap algorithm, we were able to ask whether and to what extend a motif was enriched in each sample, and obtain a motif by sample matrix, where each row is a motif, each column is a sample, and the values in this matrix represent the significance of enrichment by −log(p value). If the average fold change of a motif in a sample was positive, then this motif was defined as positive enriched in the sample; and if that of a motif in a sample was negative, then this motif was defined as negative enriched in the sample. The top enriched/depleted between normal and disease was defined as the −log(p value) differences between normal samples and disease samples (here CTCL Bulk and Leukemic samples). The higher this value is, the more enriched this motif is in normal samples, and the lower this value is, the more enriched this motif is in disease samples. The genome-wide motif footprinting analysis was performed using PIQ v1.2 (Sherwood et al., 2014). For footprinting, we adjusted the read start sites to represent the center of the transposon's binding event (see above). Previous descriptions of the Tn5 transposase show that the transposon binds as a dimer and inserts two adaptors separated by 9 bp (Adey et al., 2010). Therefore, we modified the reads' aligned file in sam format by offsetting +4bp for all the reads aligned to the forward strand, and -5bp for all the reads aligned to the reverse strand. We then converted a shifted base sam file to bam format and had the bam file sorted using samtools. We concatenated ATAC-seq reads each category of samples (Normal, Host, CTCL Bulk and Leukemic) and randomly selected 100M reads from each group and made merged bam files. PIQ takes a sorted bam file and a list of motif position weight matrix (PWM) file as inputs. We took default settings and run PIQ as instructed here: https://bitbucket.org/thashim/piq-single. PIQ predicted the genomic occupation of 242 motifs with binding affinity estimated by purity scores. We filtered the PIQ predictions using a purity score cutoff at 0.7, and overlaid these predictions with randomly selected 100M reads in each category. We then averaged the overlaid read counts of 200bp genomic region centered by the motif sites for motif footprints.

Drug response analysis

To evaluate how the entire chromatin responds to HDACi anti-cancer drugs, we used an in house generated script (K.Q.) to calculate the RPKMs of all the chromatin accessible sites, and see how they were changed during the drug treatment. The top 5000 most altered peaks in terms of RPKM fold changes, either gain or lose accessibility, were selected and the fold changes of treated states versus their corresponding untreated states (Day0) of the same patient were plotted (Figure 6C, Figure S4A). Samples were ordered according to their drug treatment time points, and unsupervised clustering was performed on the peaks using software Cluster 3.0 and visualized in Treeview. The average fold changes of the corresponding peak in normal versus CTCL samples was also plotted, together with whether a peak belonged to cluster 1, 2, or 3 defined in Figure 2A. An entire list of tumor suppressor genes (1217 genes) was obtained from Tumor Suppressor Gene Database(Zhao et al., 2013), and a list of 1301 peaks -5kb to 2kb around the promoters of these genes were defined as tumor suppressor peaks. Drug response of these tumor suppressor peaks was analyzed and plotted in a similar way (Figure S5A). The clinical response of leukemic (Sézary) cells with HDACi therapy was assessed using flow cytometric analysis conducted as part of clinical care practice (Stanford Hospital Clinical Laboratory, Stanford, CA).

Enhancer cytometry analysis

CIBERSORT (Newman et al., 2015) with “Custom Signature Gene” option was used to deconvolve the composition of subtype T cells in bulk CTCL samples. ATAC-seq on primary Naïve, Th1, Th2, Treg and Th17 cells were performed and data was processed in a same way as above. Reads in each cell type were concatenated and peaks were called using MACS2 as above. Only high quality peaks in each cell type were kept and merged to a T cell subtype peak list. Peak intensities in subtype T cells as well as Bulk CTCL and other samples were obtained using BedTools. Peaks mapping to chromosome X and promoter/TSS regions were manually removed. Manual removal of peaks improves the predictive capabilities of CIBERSORT (Corces et al., 2016). Peak intensity matrix in subtype T cells was used as the reference sample file, and phenotype class file was manually generated for CIBERSORT to obtain a custom gene signature. Peak intensity matrix in Bulk CTCL and other samples was used as the mixture file in CIBERSORT, which then deconvolved the composition of T subtypes in each sample in the mixture file. Predicted percentages of each T subtype cells in each sample were grouped into Normal, Host, CTCL bulk and CTCL leukemic samples, and histogram was performed in R.

Copy number variation analysis

Copy number variation analysis was performed according to (Denny et al., 2016). ATAC-seq reads from the same patient or healthy donor at each category (bulk, host or leukemic) were concatenated to address the chromosomal copy number of the patient or donor. Each chromosome was divided into windows size of 1Mbp at sliding step of 500Kbp. Within each window, reads mapped to ATAC-seq peaks were removed, remaining only the background reads. The average coverage for window was defined as follows:

We then performed 3 normalizing steps to estimate the copy number of each sliding window in each sample: (1] by sequencing depth from each concatenated sample; (2] by the median coverage of the normal samples and calculated the Log2 ratio over that median coverage; and (3] by the median coverage of each sample itself. We defined a copy number gain or loss by Z-score greater than 2. Regulome patterns were defined in Figure 4A, and the enrichment of each pattern for each patient was defined as the number of samples in each pattern divided by the total number of samples of the same patient in all the patterns.

Data and Software Availability

GEO accession

Raw reads and called peaks for all samples are available through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO] via accession GSE85853.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Student T-tests were applied in Figures 3D, 5A, 5B, S3A.

Chi-Square Test and Bonferroni correction were applied in Figure 7C.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Sequencing quality and statistics of all the samples, Related to Figure 1.

Table S2. Demographic information of all the samples from the donors and patients, Related to Figure 1.

Significance.

Cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) is a heterogeneous group of T cell neoplasms, and is the first FDA-approved indication for epigenetic treatment with HDAC inhibitors (HDACi). However the landscape of CTCL epigenome and its dynamic response to therapy in vivo are not known. Here we characterized the accessible chromatin landscapes in clinical CTCL samples and their dynamic response to HDACi. The pattern of accessible chromatin can predict clinical response to HDACi where DNA mutations do not. Regulome profiling in cancer may thus provide unique prognostic and mechanistic insights.

Highlights.

Regulome signatures distinguish CTCL leukemic, CTCL host, and normal CD4+ T cells.

CTCL regulomes show three dominant patterns of transcription factor activity.

Specific chromatin dynamics are associated with clinical response to HDACi.

HDACi accentuates pre-existing DNA access in CTCL leukemic and host CD4+ T cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Chang and Greenleaf labs for discussions, Grant Ognibene and Illisha Rajasansi for coordinating and collecting patients' samples, and all the patients for participation. This work was supported by Haas Family Foundation (to Y.H., H.Y.C.), NIH grant P50-HG007735 (to. H.Y.C., W.J.G.), R35-CA209919 (H.Y.C.), Stanford Cancer Institute (to Y.H., H.Y.C.), National Natural Science Foundation of China grant 91640113 (to K. Q.), the Chinese Government 1000 Youth Talent Program (to K. Q.), the research start-up from the University of Science and Technology of China (to K. Q.). H.Y.C. is a scientific co-founder of Epinomics and a member of its scientific advisory board. W.G.J. is a scientific co-founder of Epinomics and a member of its scientific advisory board. P.G.G. is a co-founder and employee of Epinomics. H.Y.C. is a member researcher of Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. We thank the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China for providing supercomputing resources for this project.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: LCZ, YHK, HYC conceived the project. LCZ, RA, ATS performed all cell sorting. RL, LCZ, ATS, PGG performed ATAC-seq experiment. NS, ZR, HU collected patients' samples and clinical information. KQ, YJ and CJ performed all data analysis. WJG provided analysis methods. KQ and HYC wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adey A, Morrison HG, Asan, Xun X, Kitzman JO, Turner EH, Stackhouse B, MacKenzie AP, Caruccio NC, Zhang X, et al. Rapid, low-input, low-bias construction of shotgun fragment libraries by high-density in vitro transposition. Genome biology. 2010;11:R119. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-r119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida ACD, Abate F, Khiabanian H, Martinez-Escala E, Guitart J, Tensen CP, Vermeer MH, Rabadan R, Ferrando A, Palomero T. The mutational landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma and Sezary syndrome. Nature genetics. 2015;47:1465–+. doi: 10.1038/ng.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro JD, Giresi PG, Zaba LC, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nature methods. 2013;10:1213–1218. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Litzenburger UM, Ruff D, Gonzales ML, Snyder MP, Chang HY, Greenleaf WJ. Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals principles of regulatory variation. Nature. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature14590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiappinelli KB, Strissel PL, Desrichard A, Li H, Henke C, Akman B, Hein A, Rote NS, Cope LM, Snyder A, et al. Inhibiting DNA Methylation Causes an Interferon Response in Cancer via dsRNA Including Endogenous Retroviruses. Cell. 2015;162:974–986. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Goh G, Walradt T, Hong BS, Bunick CG, Chen K, Bjornson RD, Maman Y, Wang T, Tordoff J, et al. Genomic landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma. Nature genetics. 2015;47:1011–1019. doi: 10.1038/ng.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corces MR, Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Greenside PG, Chan SM, Koenig JL, Snyder MP, Pritchard JK, Kundaje A, Greenleaf WJ, et al. Lineage-specific and single-cell chromatin accessibility charts human hematopoiesis and leukemia evolution. Nature genetics. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ng.3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corces-Zimmerman MR, Hong WJ, Weissman IL, Medeiros BC, Majeti R. Preleukemic mutations in human acute myeloid leukemia affect epigenetic regulators and persist in remission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:2548–2553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324297111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusanovich DA, Daza R, Adey A, Pliner HA, Christiansen L, Gunderson KL, Steemers FJ, Trapnell C, Shendure J. Epigenetics. Multiplex single-cell profiling of chromatin accessibility by combinatorial cellular indexing. Science. 2015;348:910–914. doi: 10.1126/science.aab1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Almeida AC, Abate F, Khiabanian H, Martinez-Escala E, Guitart J, Tensen CP, Vermeer MH, Rabadan R, Ferrando A, Palomero T. The mutational landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma and Sezary syndrome. Nature genetics. 2015;47:1465–1470. doi: 10.1038/ng.3442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denny SK, Yang D, Chuang CH, Brady JJ, Lim JS, Gruner BM, Chiou SH, Schep AN, Baral J, Hamard C, et al. Nfib Promotes Metastasis through a Widespread Increase in Chromatin Accessibility. Cell. 2016;166:328–342. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolnik A, Engelmann JC, Scharfenberger-Schmeer M, Mauch J, Kelkenberg-Schade S, Haldemann B, Fries T, Kronke J, Kuhn MW, Paschka P, et al. Commonly altered genomic regions in acute myeloid leukemia are enriched for somatic mutations involved in chromatin remodeling and splicing. Blood. 2012;120:e83–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-401471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulmage BO, Geskin LJ. Lessons learned from gene expression profiling of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. The British journal of dermatology. 2013;169:1188–1197. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dummer R, Heald PW, Nestle FO, Ludwig E, Laine E, Hemmi S, Burg G. Sezary syndrome T-cell clones display T-helper 2 cytokines and express the accessory factor-1 (interferon-gamma receptor beta-chain) Blood. 1996;88:1383–1389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J, Kellis M. ChromHMM: automating chromatin-state discovery and characterization. Nature methods. 2012;9:215–216. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I, et al. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature. 2010;468:1067–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flavahan WA, Drier Y, Liau BB, Gillespie SM, Venteicher AS, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Suva ML, Bernstein BE. Insulator dysfunction and oncogene activation in IDH mutant gliomas. Nature. 2016;529:110–114. doi: 10.1038/nature16490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nature immunology. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Williams LM, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E, Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H, Glass CK. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Molecular cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan M, Snyder TM, Corces-Zimmerman MR, Vyas P, Weissman IL, Quake SR, Majeti R. Clonal evolution of preleukemic hematopoietic stem cells precedes human acute myeloid leukemia. Science translational medicine. 2012;4:149ra118. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, Moskowitz A, Querfeld C. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome): part II. Prognosis, management, and future directions. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2014;70:223 e221–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.08.033. quiz 240-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annual review of immunology. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landt SG, Marinov GK, Kundaje A, Kheradpour P, Pauli F, Batzoglou S, Bernstein BE, Bickel P, Brown JB, Cayting P, et al. ChIP-seq guidelines and practices of the ENCODE and modENCODE consortia. Genome Res. 2012;22:1813–1831. doi: 10.1101/gr.136184.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Astiaso D, Weiner A, Lorenzo-Vivas E, Zaretsky I, Jaitin DA, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Mildner A, Winter D, Jung S, et al. Immunogenetics. Chromatin state dynamics during blood formation. Science. 2014;345:943–949. doi: 10.1126/science.1256271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin Y, Winter D, Blecher-Gonen R, David E, Keren-Shaul H, Merad M, Jung S, Amit I. Tissue-resident macrophage enhancer landscapes are shaped by the local microenvironment. Cell. 2014;159:1312–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CS, Ungewickell A, Bhaduri A, Qu K, Webster DE, Armstrong R, Weng WK, Aros CJ, Mah A, Chen RO, et al. Transcriptome sequencing in Sezary syndrome identifies Sezary cell and mycosis fungoides-associated lncRNAs and novel transcripts. Blood. 2012;120:3288–3297. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-423061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbach M, Saare M, Tserel L, Kisand K, Eglit T, Sauer S, Axelsson T, Syvanen AC, Metspalu A, Milani L, et al. Epigenetic profiling in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from Graves' disease patients reveals changes in genes associated with T cell receptor signaling. Journal of autoimmunity. 2016;67:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathelier A, Fornes O, Arenillas DJ, Chen CY, Denay G, Lee J, Shi W, Shyr C, Tan G, Worsley-Hunt R, et al. JASPAR 2016: a major expansion and update of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic acids research. 2016;44:D110–115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar C, Shen Y, Xavy S, Zhao F, Reinisch A, Li R, Corces MR, Flynn RA, Buenrostro JD, Chan SM, et al. Leukemia-Associated Cohesin Mutants Dominantly Enforce Stem Cell Programs and Impair Human Hematopoietic Progenitor Differentiation. Cell stem cell. 2015;17:675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CY, Bristor D, Hiller M, Clarke SL, Schaar BT, Lowe CB, Wenger AM, Bejerano G. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nature biotechnology. 2010;28:495–501. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita R, Schmitt N, Bentebibel SE, Ranganathan R, Bourdery L, Zurawski G, Foucat E, Dullaers M, Oh S, Sabzghabaei N, et al. Human blood CXCR5(+)CD4(+) T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity. 2011;34:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New M, Olzscha H, La Thangue NB. HDAC inhibitor-based therapies: can we interpret the code? Molecular oncology. 2012;6:637–656. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, Hoang CD, Diehn M, Alizadeh AA. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nature methods. 2015;12:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niess H, Camaj P, Mair R, Renner A, Zhao Y, Jackel C, Nelson PJ, Jauch KW, Bruns CJ. Overexpression of IFN-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 (IFIT3) in pancreatic cancer: cellular “pseudoinflammation” contributing to an aggressive phenotype. Oncotarget. 2015;6:3306–3318. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen EA, Whittaker S, Kim YH, Duvic M, Prince HM, Lessin SR, Wood GS, Willemze R, Demierre MF, Pimpinelli N, et al. Clinical end points and response criteria in mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: a consensus statement of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas, the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium, and the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29:2598–2607. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng D, Kryczek I, Nagarsheth N, Zhao L, Wei S, Wang W, Sun Y, Zhao E, Vatan L, Szeliga W, et al. Epigenetic silencing of TH1-type chemokines shapes tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nature. 2015;527:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature15520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JE, Corces VG. CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell. 2009;137:1194–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nature reviews Immunology. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu K, Zaba LC, Giresi PG, Li R, Longmire M, Kim YH, Greenleaf WJ, Chang HY. Individuality and variation of personal regulomes in primary human T cells. Cell systems. 2015;1:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan AR, Hall IM. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn EM, Coleman C, Molloy B, Dominguez Castro P, Cormican P, Trimble V, Mahmud N, McManus R. Transcriptome Analysis of CD4+ T Cells in Coeliac Disease Reveals Imprint of BACH2 and IFNgamma Regulation. PloS one. 2015;10:e0140049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roadmap Epigenomics C, Kundaje A, Meuleman W, Ernst J, Bilenky M, Yen A, Heravi-Moussavi A, Kheradpour P, Zhang Z, Wang J, et al. Integrative analysis of 111 reference human epigenomes. Nature. 2015;518:317–330. doi: 10.1038/nature14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Paredes M, Esteller M. Cancer epigenetics reaches mainstream oncology. Nature medicine. 2011;17:330–339. doi: 10.1038/nm.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal E, Friedman N, Koller D, Regev A. A module map showing conditional activity of expression modules in cancer. Nature genetics. 2004;36:1090–1098. doi: 10.1038/ng1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrocks AD. The ETS-domain transcription factor family. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2001;2:827–837. doi: 10.1038/35099076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood RI, Hashimoto T, O'Donnell CW, Lewis S, Barkal AA, van Hoff JP, Karun V, Jaakkola T, Gifford DK. Discovery of directional and nondirectional pioneer transcription factors by modeling DNase profile magnitude and shape. Nature biotechnology. 2014;32:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon Anders WH. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome biology. 2010;11 doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]