Abstract

Background

PET using O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine (18F-FET) is an established method for brain tumour diagnostics, but data processing varies in different centres. This study analyses the influence of methodological differences between two centres for tumour characterization with 18F-FET PET using the same PET scanner.

Methodological differences between centres A and B in the evaluation of 18F-FET PET data were identified for (1) framing of PET dynamic data, (2) data reconstruction, (3) cut-off values for tumour delineation to determine tumour-to-brain ratios (TBR) and tumour volume (Tvol) and (4) ROI definition to determine time activity curves (TACs) in the tumour. Based on the 18F-FET PET data of 40 patients with untreated cerebral gliomas (20 WHO grade II, 10 WHO grade III, 10 WHO grade IV), the effect of different data processing in the two centres on TBRmean, TBRmax, Tvol, time-to-peak (TTP) and slope of the TAC was compared. Further, the effect on tumour grading was evaluated by ROC analysis.

Results

Significant differences between centres A and B were found especially for TBRmax (2.84 ± 0.99 versus 3.34 ± 1.13; p < 0.001), Tvol (1.14 ± 1.28 versus 1.51 ± 1.44; p < 0.001) and TTP (22.4 ± 8.3 min versus 30.8 ± 6.3 min; p < 0.001) and minor differences for TBRmean and slope. Tumour grading was not influenced by different data processing.

Conclusions

Variable data processing of 18F-FET PET in different centres leads to significant differences especially for TBRmax and Tvol. A standardization of data processing and evaluation is needed to make 18F-FET PET comparable between different centres.

Keywords: Brain tumours, FET PET, Tumour-to-brain ratios, Dynamic FET PET

Background

PET using the amino acid O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine (18F-FET) has received increasing attention for brain tumour diagnostics due to logistic advantages of 18F labelling (half-life, 109.8 min) compared with l-[methyl-11C]-methionine (11C-MET) PET, efficient radiosynthesis and high in-vivo stability [1–6]. Multiple studies have demonstrated the clinical potential of 18F-FET PET to determine the extent of cerebral gliomas for biopsy guidance, treatment planning, detection of tumour recurrence, estimation of prognosis in newly diagnosed and untreated gliomas and treatment monitoring [7–12]. 18F-FET uptake in the tumour is usually expressed by mean and maximum tumour-to-brain ratios (TBRmean, TBRmax) within a scan period between 20 and 40 min after injection. Furthermore, the time-activity curves (TACs) of 18F-FET uptake typically show differences in high-grade and low-grade gliomas or nonneoplastic lesions which provide valuable additional information for tumour grading or differential diagnosis [13–15]. Thus, continuously increasing 18F-FET uptake is more frequently observed in low-grade gliomas and nonneoplastic lesions, while kinetics with an early peak of 18F-FET uptake in the first 10–20 min after injection followed by a decreasing TAC is a common finding in more aggressive tumours like high-grade glioma or brain metastases [10, 16, 17]. TBR and dynamic parameters of 18F-FET uptake may be influenced on the one hand by the spatial resolution of the PET scans which is dependent on the scanner type, reconstruction algorithms and data filtering and on the other hand by the definition of the region of interest (ROI) in the tumour and the brain. There is some controversy about the diagnostic accuracy of TAC analysis for tumour grading raising the question whether discrepant results in different centres may be caused by differences in the methodology, patient population or other reasons such as neuropathological interpretation.

In the present study, methodological differences between two large centres in Germany (A = Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, Germany; B = Forschungszentrum Jülich, Germany) with a high number of 18F-FET PET investigations (> 500/year) and multiple publications in the field were identified. Based on a balanced group of 20 patients with high-grade glioma of WHO grade III and IV (HGG) and 20 patients with low-grade glioma of WHO grade II (LGG) [18] who were investigated with the same scanner used in both centres, the influence of methodological differences between the two centres on common parameters for tumour characterization with 18F-FET PET was evaluated. This analysis may be helpful to develop a more standardized approach in order to make the data between different centres more comparable.

Methods

Patient population

The data of 40 adults, previously untreated patients with brain tumours who were investigated with 18F-FET PET at the Forschungszentrum Jülich between June 2006 and April 2014, were selected randomly from our data base and included in this study. Histopathological diagnosis was available for all patients obtained either by biopsy or tumour resection which was performed within 3 months after 18F-FET PET. Diagnosis was astrocytoma WHO grade II in 20 cases, anaplastic astrocytoma WHO grade III in 10 cases and glioblastoma WHO grade IV in 10 cases according to Louis et al. [18]. All patients were investigated within a prospective study evaluating the diagnostic value 18F-FET PET in cerebral gliomas which was approved by the university ethics committee and federal authorities (study no. 2438, University of Düsseldorf). All subjects gave prior written informed consent for their participation in the 18F-FET PET study and evaluation of their data for scientific purposes.

18F-FET PET

The amino acid 18F-FET was produced via aminopolyether-activated nucleophilic 18F-fluorination and applied as described previously [19]. Dynamic PET data were acquired in list mode for 40 min after intravenous injection of approx. 200 MBq 18F-FET. The measurements were performed on an ECAT Exact HR+ scanner in 3D mode (Siemens Medical Systems, Knoxville, TN, USA: 32 rings, axial field of view 15.5 cm, image resolution 5.5 mm) which is routinely used for 18F-FET PET in both centres. For attenuation correction, transmission scans with three 68Ge/68Ga rotating line sources were measured. Raw PET data were corrected for random and scattered coincidences as well as dead time.

Data processing

Methodological differences between centres A and B were identified for the framing of dynamic PET data and data reconstruction (Table 1). Therefore, the PET data were processed in two different ways according to the individual approach established in centre A and centre B. For centre A, the dynamic data set was framed into time intervals of 6 × 10 s, 4 × 30 s, 1 × 2 min, 3 × 5 min and 2 × 10 min and the data were reconstructed by filtered back projection (FBP) using a 5-mm Hann filter. For centre B, the framing was 5 × 1 min, 5 × 3 min and 4 × 5 min followed by iterative reconstruction (ITR) (ordered-subset expectation maximization, 6 iterations, 16 subsets). 18F-FET uptake in the tissue was expressed as standardized uptake value (SUV) by dividing the radioactivity (kBq/ml) in the tissue by the radioactivity injected per gram of body weight. An example of a brain tumour for the time interval from 20 to 40 min after injection for the different data processing in centres A and B is shown in Fig. 1. Corresponding evaluation of a Jaszczak phantom with the two methods is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of methodology centre A and centre B

| Centre A | Centre B | |

|---|---|---|

| LMU | FZJ | |

| Scanner | ECAT Exact HR+ PET | ECAT Exact HR+ PET |

| Framing | 6 × 10”, 4 × 30”, 1 × 2’, 3 × 5’, 2 × 10’ | 5 × 1’, 5 × 3’, 6 × 5’ |

| Reconstruction | FBP (5-mm Hann filter) | Iterative 6i/16s |

| Definition of tumour volume (cut-off) | TBR > 1.8 | TBR > 1.6 |

| ROI for TAC definition | 90% isocontour in different slices | TBR > 1.6 in slice with FET maximum |

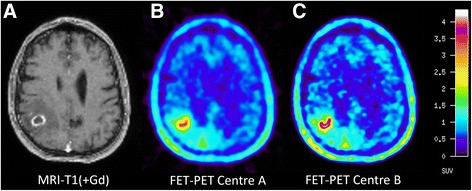

Fig. 1.

Glioblastoma in the right parietal lobe. Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI (a) shows a ring-enhancing lesion. FET PET image based on the method of centre A (b) shows lower noise but the image based on the method of centre B (c) shows a sharper demarcation of the metabolically active tumour parts

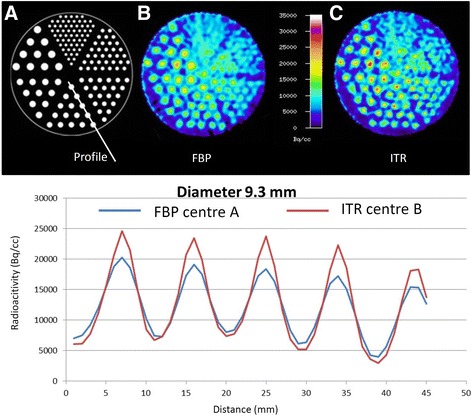

Fig. 2.

Jasczack phantom (a) with tubes of different size filled with radioactivity and reconstructed according to the procedure in centre A (b, blue profile line) and centre B (c, red profile line). The method of centre A shows about 20% lower maximum values in the tubes with a diameter of 9.3 mm which is mainly due to reconstruction by filtered back projection in centre A instead of iterative reconstruction (centre B)

Definition of tumour ROI

Further differences between the two centres were identified for the definition of the region of interest (ROI) for the tumour which was used to determine the tumour volume (Tvol) and the TBRmax and TBRmean. For the two data sets generated by the different data processing in centres A and B, the definition of these tumour ROIs was based on the summed images of 18F-FET uptake from 20 to 40 min after injection in the slice with the maximal 18F-FET uptake in the tumour. The background ROI was placed in the contralateral hemisphere to the tumour in an area of normal-appearing brain tissue including white and grey matter, identically for centres A and B. For the data set of centre A, the tumour volume (Tvol) was delineated using a cut-off of the TBR > 1.8 which is based on the clinical experience in that centre [16, 20]. For the data set of centre B, Tvol was delineated using a cut-off of the TBR > 1.6 based on a previous biopsy controlled study [8]. TBRmax and TBRmean were calculated by dividing the mean and maximum SUV in the tumour ROI by the mean SUV of the background region in the normal brain tissue. An example is shown in Fig. 3.

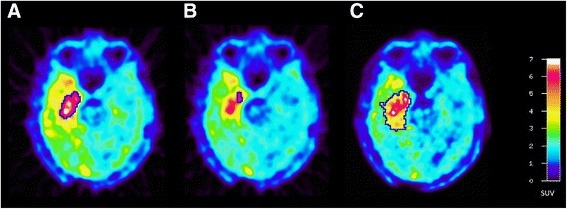

Fig. 3.

ROI definition in a patient with a glioblastoma in the right temporal lobe. a The tumour volume as delineated by TBR > 1.8 based on data reconstruction of centre A. b The 90% isocontour of the 10–30-min image for TAC generation in centre A and c the tumour volume as delineated by a TBR > 1.6 in centre B which is also used TAC generation

For analysis of dynamic PET data, all TACs were corrected for radioactive decay of 18F. Centre B used a single tumour ROI which was placed in the slice with maximal tracer uptake in the 20–40-min summation images and which was defined by the cut-off TBR > 1.6 as described above. In centre A, multiple slices of the tumour area were screened and a 90% isocontour ROI of the local tumour maxima was created in the individual slices of the summation image 10–30 min p.i. and TACs were recorded for each slice of the tumour region (Fig. 3b). The TAC with the most negative slope was identified, and the most negative slope being present in at least two adjacent slices was selected for further TAC evaluation. In order to compare the TACs produced by the two different centres quantitatively, the time-to-peak (TTP; time in minutes from the beginning of the dynamic acquisition up to the maximum SUV of the lesion) was determined based on different ROIs determined for centres A and B. Furthermore, we quantified the slope of the TAC in the late phase of 18F-FET uptake by fitting a linear regression line to the late phase of the curve (10–40 min p.i.). The slope was expressed in change of SUV per hour.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are provided as mean and standard deviation. To compare the results obtained with the different approaches in the two centres based on the same raw data, the paired t test and Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used. The signed rank test was used when variables were not distributed normally. P < 0.05 was considered significant. The diagnostic performance of the different parameters to differentiate between LGG (WHO grade II) and HGG (WHO grade III and IV) was assessed by analyses of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves using the histological confirmation as reference. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was used to compare the results obtained with different methodologies. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot software (SigmaPlot v11.0, Systat Software). No correction for multiple testing was included.

Results

Static PET data

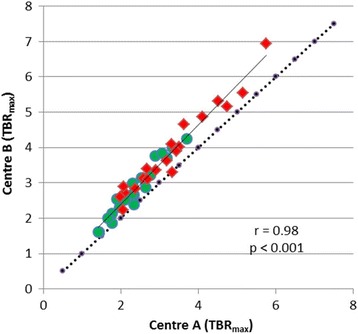

TBRmax values as determined by the different methodologies of centres A and B showed a significant correlation (r = 0.98, p < 0.001), but there was a deviation from the line of unity towards higher TBRmax values for centre B (Fig. 4). The mean values of TBRmax in centre A were significantly lower than that in centre B (A/TBRmax 2.84 ± 0.99 versus B/TBRmax 3.34 ± 1.13, p < 0.001) (Table 2). This is also reflected by the lower peak values in the profile of count rates across the tubes with a diameter of 9.3 mm in the Jaszczak phantom (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4.

Correlation of TBRmax from centres A and B. There is a significant correlation but a deviation from line of unity indicating higher TBRmax values for centre B. High-grade tumours are indicated by red symbols and low-grade tumour by green symbols

Table 2.

Comparison of 18F-FET parameters in centre A and centre B based on the same data set

| Centre A | Centre B | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison of mean values of FET PET parameters | |||

| TBRmax | 2.84 ± 0.99 | 3.34 ± 1.13 | < 0.001 |

| TBRmean | 2.20 ± 0.41 | 2.16 ± 0.41 | < 0.04 |

| Tvol (ml) | 1.14 ± 1.28 | 1.51 ± 1.44 | < 0.001 |

| TTP (min) | 22.4 ± 8.3 | 30.8 ± 6.3 | < 0.001 |

| Slope (SUV/h) | −0.06 ± 0.92 | 0.73 ± 0.69 | < 0.001 |

| Comparison of accuracy in differentiating HG and LG gliomas (AUC in ROC analysis) | |||

| TBRmax | 0.77 | 0.78 | n.s. |

| TBRmean | 0.78 | 0.76 | n.s. |

| Tvol | 0.78 | 0.76 | n.s. |

| TTP | 0.73 | 0.78 | n.s. |

| Slope | 0.76 | 0.72 | n.s. |

n.s. = not significant

ROC analysis yielded a similar AUC for the differentiation of high-grade and low-grade gliomas using the TBRmax values determined with the different approaches (AUC TBRmax centre A = 0.77 and AUC TBRmax centre B = 0.78) (Table 2).

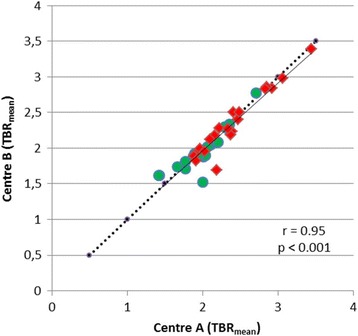

TBRmean values as determined by the different methodologies of centres A and B showed a significant correlation (r = 0.95, p < 0.001), which was nearly congruent with the line of unity (Fig. 5). The mean values of TBRmean were nearly identical although a weak significance was noted in the paired t test (A/TBRmean 2.20 ± 0.41 versus B/TBRmean 2.16 ± 0.41, p < 0.04) (Table 2). ROC analysis yielded a similar AUC for the differentiation of high-grade and low-grade gliomas using the TBRmean values determined with the different approaches (AUC TBRmean centre A = 0.78 and AUC TBRmean centre B = 0.76) (Table 2).

Fig. 5.

Correlation of TBRmean from centres A and B. There is a significant correlation which is close to the line of unity. High-grade tumours are indicated by red symbols and low-grade tumour by green symbols

Tvol values calculated according to the different methodologies of centres A and centre B showed a significant correlation (r = 0.99, p < 0.001), but there was a significant difference of the mean values (Tvol A 1.14 ml ± 1.28 ml versus Tvol B 1.51 ml ± 1.43 ml), which leads to relevant differences in the definition of the “biological tumour volume”.

Dynamic PET data

TTP values as determined by the different methodologies of centres A and B showed a significant correlation (r = 0.61, p < 0.001), but the correlation coefficient was considerably smaller than for the parameters mentioned above. There was a significant difference of the mean values (TTP A 22.4 ± 8.3 min versus TTP B 30.8 ± 6.3 min, p < 0.001).

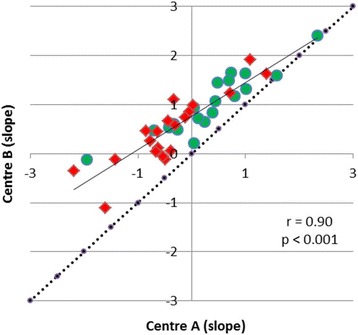

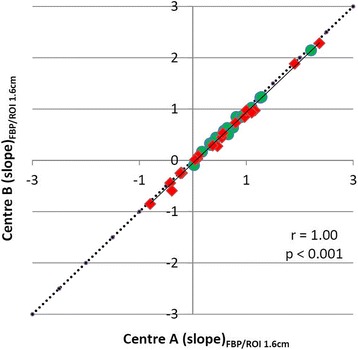

Slope values calculated according to methodology of centres A and B showed a significant correlation (r = 0.90, p < 0.001) (Fig. 6). There was a significant difference of the mean values (slope A −0.06 ± 0.92 SUV/h versus slope B 0.73 ± 0.69 SUV/h). For both TTP and slope, ROC analysis yielded a similar AUC for the differentiation between HGG and LGG determined with the two different approaches (Table 2). Comparison of the slope values in both centres with framing as the only variable using the same reconstruction method (FBP) and ROI size (Ø 1.6 cm) for both data sets showed a correlation close to the line of unity (Fig. 7). Thus, an influence of different data framing in centres A and B could be excluded.

Fig. 6.

Correlation of slope of the TAC of 18F-FET uptake from 10 to 40 min p.i. There is a significant correlation but a deviation from line of unity indicating lower slope values for centre A. High-grade tumours are indicated by red symbols and low-grade tumour by green symbols

Fig. 7.

Correlation of slope of the TAC of 18F-FET uptake from 10 to 40 min p.i., comparing the effect of different framing in centres A and B. All data were reconstructed by FBP according to centre A and evaluated with a circular ROI with fixed a diameter of 1.6 cm. There is a highly significant correlation which virtually excludes an influence of different data framing. High-grade tumours are indicated by red symbols and low-grade tumour by green symbols

Discussion

PET using radiolabelled amino acids is gaining increasing interest for the diagnostics of brain tumours because conventional MRI is limited in differentiating tumour tissue from nonspecific tissue changes, especially after therapy [21]. Recently, the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) working group—an international effort to develop new standardized response criteria for clinical trials in brain tumours—has recommended the additional use of amino acid PET imaging for brain tumour management [5]. The longest established amino acid tracer 11C-MET has been replaced in many neuro-oncology centres by the more convenient 18F-FET, and several thousand 18F-FET PET scans have been performed in some centres in recent years [22]. The broad clinical use of 18F-FET PET requires comparable quantitative parameters, but as yet, the reported cut-off values of different parameters like TBRmean, TBRmax, TTP, slope and Tvol for tumour grading or differentiation of recurrent tumour from treatment related changes appear to vary among different centres. It remains unclear whether diverging results are caused by the composition of the study population, differences in the technical equipment or differences in data processing or a combination thereof.

In this study, we have identified methodological differences between two centres in Germany which have a high frequency of 18F-FET PET investigations and contributed to the clinical evaluation of 18F-FET PET through numerous publications (for review, see [3, 5]). Since in both centres, the previous publications on 18F-FET PET studies were performed with the same PET scanner, differences in the technical equipment between the centres can be excluded. A comparison of data processing, however, identified methodological differences between the centres concerning the framing of PET data, data reconstruction, tumour delineation and ROI definition to evaluate tracer kinetics in the tumour. The effects of these methodological differences on quantitative parameters of FET PET were examined in a collective of 40 brain tumour patients.

One frequently used parameter for brain tumour characterization is the TBRmax which showed approximately 15% lower values when generated with the methodology of centre A than with that of centre B. In agreement with these findings, we observed lower peak values in a phantom study when data were reconstructed according to the method of centre A. In accordance with these findings, the reported average TBRmax values in primary brain tumours are lower in centre A than in centre B (HGG: A/TBRmax 3.3 ± 1.2 versus B/TBRmax 3.6 ± 1.4, LGG: A/TBRmax 2.1 ± 1.0 versus B/TBRmax 2.4 ± 1.0) [23, 24]. Nevertheless, the cut-off values of the TBRmax for differentiating between HGG and LGG in those studies were similar (cut-off: A/TBRmax 2.7, B/TBRmax 2.5), and the accuracy of differentiating between HGG and LGG based on the TBRmax appears to be similar to both centres. For the differentiation of recurrent tumours from treatment-related changes which is a frequent clinical question, the reported cut-off value for TBRmax was 2.0 in centre A and 2.3 in centre B which might also reflect the difference in data processing in the two centres [12, 25]. TBRmean values generated with the methodology of centres A and B showed a small but significant difference in the paired t test (A/TBRmean 2.20 ± 0.41 versus and B/TBRmean 2.16 ± 0.41, p < 0.04), but this difference would no longer be significant if a correction for multiple testing were applied.

A major difference between both centres was observed for the definition of the biological tumour volume. The approach of centre A led to approximately 25% smaller tumour volumes than that of centre B which is of substantial importance since 18F-FET PET is increasingly used when planning therapeutic interventions such as surgery and radiotherapy. It has to be considered that the approach of centre A is based on clinical experience while the approach of centre B was developed on the basis of a biopsy-controlled study which from a scientific point of view has to be regarded as more reliable [8]. On the other hand, that study is based on 52 biopsies in 31 patients only, which appears not sufficient to establish a clinical standard. Furthermore, only patients with newly diagnosed brain tumours were included, and the optimal threshold might be different for pretreated patients who can present slight unspecific tracer uptake at the primary tumour site. Therefore, further biopsy-controlled studies are needed to clarify this clinically important aspect.

The evaluation of dynamic 18F-FET PET by the approach of centre A yielded shorter TTP values and lower values for the slope in the late phase of the TAC. A detailed analysis showed that the different framing procedures in centres A and B did not influence the dynamic parameters (Fig. 7) and also the ROI definition by 90% isocontour instead of TBR > 1.6 caused only minor differences. The decisive difference was caused by the more extensive search for tumour areas with negative slope in the entire tumour volume in centre A. This approach appears to be advantageous but is technically more challenging. On the other hand, we did not detect a significant difference between the two approaches for the differentiation between HGG and LGG by ROC analysis in this group of patients.

An important reason for the differences in TBRmax and Tvol observed in both centres is the different spatial resolution of the PET scans which is caused by the different reconstruction methods. It appears that the use of FBP in centre A is a major cause of the observed differences which is also evident from the phantom study (Fig. 2). This observation is in line with previous studies comparing the difference of FBP to OSEM on quantification of glucose metabolism which all report higher SUVs for OSEM as compared to FBP [26–28]. Since in newer PET systems, data processing is generally based on iterative reconstruction differences between centres which may become smaller in the future. In any case, the spatial resolution of PET scans should be comparable when applying threshold values for the definition of ROIs in the tumour area with FET PET. It is therefore necessary to adapt the reconstruction parameters in order to achieve a similar spatial resolution in various PET systems. Kinetic parameters are less strongly influenced by spatial resolution but are altered by the selection of specific tumour regions.

It needs to be considered that owing to the lack of molecular data for histological analysis, tumour classification was based on the WHO classification from 2007 instead of the new one from 2016, which includes molecular parameters [18, 29]. Therefore, the AUC values obtained for tumour grading in this study might not be directly applicable to the current classification, and an influence on the comparison of the AUC values for centres A and B cannot be excluded.

Conclusions

The differences in data processing between the two centres lead to considerable differences especially for TBRmax, slope, TTP and Tvol. Although there was a strong linear correlation between TBRmax and Tvol values of both centres, the absolute values cannot directly be compared. Absolute TBRmean values, by contrast, seem comparable between both centres. However, concerning the evaluation of dynamic 18F-FET PET, both centres achieved comparable high accuracy to discriminate between HGG and LGG. A standardization of data processing and protocols for 18F-FET-PET is needed in order to make clinical results comparable.

Authors’ contributions

CPF, NLA, GB, BS, NJS, FMM, PB, JCT and KJL designed the study and wrote the protocol. CPF and GS performed the PET studies. CPF, ERK, NG and KJL analysed the data. CPF, NLA and KJL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients were investigated within a prospective study evaluating the diagnostic value 18F-FET PET in cerebral gliomas which was approved by the university ethics committee and federal authorities (study no. 2438, University of Düsseldorf). All subjects gave prior written informed consent for their participation in the 18F-FET PET study and evaluation of their data for scientific purposes. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Suchorska B, Albert NL, Tonn JC. Usefulness of PET imaging to guide treatment options in gliomas. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2016;18:4. doi: 10.1007/s11940-015-0384-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galldiks N, Langen KJ, Pope WB. From the clinician’s point of view—what is the status quo of positron emission tomography in patients with brain tumors? Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17:1434–1444. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galldiks N, Langen KJ. Applications of PET imaging of neurological tumors with radiolabeled amino acids. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;59:70–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herholz K, Langen KJ, Schiepers C, Mountz JM. Brain tumors. Semin Nucl Med. 2012;42:356–370. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Albert NL, Weller M, Suchorska B, Galldiks N, Soffietti R, Kim MM, et al. Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology working group and European Association for Neuro-Oncology recommendations for the clinical use of PET imaging in gliomas. Neuro-Oncology. 2016;18:1199–1208. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wester HJ, Herz M, Weber W, Heiss P, Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R, Schwaiger M, et al. Synthesis and radiopharmacology of O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine for tumor imaging. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galldiks N, Langen K, Holy R, Pinkawa M, Stoffels G, Nolte K, et al. Assessment of treatment response in patients with glioblastoma using [18F]fluoroethyl-L-tyrosine PET in comparison to MRI. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1048–1057. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.098590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauleit D, Floeth F, Hamacher K, Riemenschneider MJ, Reifenberger G, Muller HW, et al. O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET combined with MRI improves the diagnostic assessment of cerebral gliomas. Brain. 2005;128:678–687. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen NL, Suchorska B, Schwarz SB, Eigenbrod S, Lutz J, Graute V, et al. [18F]fluoroethyltyrosine-positron emission tomography-based therapy monitoring after stereotactic iodine-125 brachytherapy in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Mol Imaging. 2013;12:137–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jansen NL, Suchorska B, Wenter V, Schmid-Tannwald C, Todica A, Eigenbrod S, et al. Prognostic significance of dynamic 18F-FET PET in newly diagnosed astrocytic high-grade glioma. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:9–15. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.144675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galldiks N, Dunkl V, Stoffels G, Hutterer M, Rapp M, Sabel M, et al. Diagnosis of pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma using O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:685–695. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2959-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galldiks N, Stoffels G, Filss C, Rapp M, Blau T, Tscherpel C, et al. The use of dynamic O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-l-tyrosine PET in the diagnosis of patients with progressive and recurrent glioma. Neuro-Oncology. 2015;17(9):1293–1300. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calcagni ML, Galli G, Giordano A, Taralli S, Anile C, Niesen A, et al. Dynamic O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (F-18 FET) PET for glioma grading: assessment of individual probability of malignancy. Clin Nucl Med. 2011;36:841–847. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182291b40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pöpperl G, Kreth FW, Mehrkens JH, Herms J, Seelos K, Koch W, et al. FET PET for the evaluation of untreated gliomas: correlation of FET uptake and uptake kinetics with tumour grading. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:1933–1942. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0534-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weckesser M, Langen KJ, Rickert CH, Kloska S, Straeter R, Hamacher K, et al. O-(2-[18F]fluorethyl)-L-tyrosine PET in the clinical evaluation of primary brain tumours. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:422–429. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1705-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jansen NL, Graute V, Armbruster L, Suchorska B, Lutz J, Eigenbrod S, et al. MRI-suspected low-grade glioma: is there a need to perform dynamic FET PET? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:1021–1029. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ceccon G, Lohmann P, Stoffels G, Judov N, Filss CP, Rapp M, et al. Dynamic O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine positron emission tomography differentiates brain metastasis recurrence from radiation injury after radiotherapy. Neuro-Oncology. 2017;19:281–288. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, Burger PC, Jouvet A, et al. The 2007 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:97–109. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0243-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamacher K, Coenen HH. Efficient routine production of the 18F-labelled amino acid O-2-18F fluoroethyl-L-tyrosine. Appl Radiat Isot. 2002;57:853–856. doi: 10.1016/S0969-8043(02)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suchorska B, Jansen NL, Linn J, Kretzschmar H, Janssen H, Eigenbrod S, et al. Biological tumor volume in 18FET-PET before radiochemotherapy correlates with survival in GBM. Neurology. 2015;84:710–719. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, Cloughesy TF, Sorensen AG, Galanis E, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1963–1972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langen KJ, Tonn JC, Weller M, Galldiks N. Letter to the editor: “the role of imaging in the management of progressive glioblastoma. A systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline” [J Neurooncol 2014; 118:435-460] J Neuro-Oncol. 2014;120:665–666. doi: 10.1007/s11060-014-1594-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albert NL, Winkelmann I, Suchorska B, Wenter V, Schmid-Tannwald C, Mille E, et al. Early static (18)F-FET-PET scans have a higher accuracy for glioma grading than the standard 20-40 min scans. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:1105–1114. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rapp M, Heinzel A, Galldiks N, Stoffels G, Felsberg J, Ewelt C, et al. Diagnostic performance of 18F-FET PET in newly diagnosed cerebral lesions suggestive of glioma. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:229–235. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.109603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pöpperl G, Gotz C, Rachinger W, Gildehaus FJ, Tonn JC, Tatsch K. Value of O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET for the diagnosis of recurrent glioma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31:1464–1470. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1590-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Etchebehere EC, Macapinlac HA, Gonen M, Humm K, Yeung HW, Akhurst T, et al. Qualitative and quantitative comparison between images obtained with filtered back projection and iterative reconstruction in prostate cancer lesions of (18)F-FDG PET. Q J Nucl Med. 2002;46:122–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visvikis D, Cheze-LeRest C, Costa DC, Bomanji J, Gacinovic S, Ell PJ. Influence of OSEM and segmented attenuation correction in the calculation of standardised uptake values for [18F]FDG PET. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:1326–1335. doi: 10.1007/s002590100566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramos CD, Erdi YE, Gonen M, Riedel E, Yeung HW, Macapinlac HA, et al. FDG-PET standardized uptake values in normal anatomical structures using iterative reconstruction segmented attenuation correction and filtered back-projection. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:155–164. doi: 10.1007/s002590000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:803–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]