ABSTRACT

Obesity is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for breast cancer development. However, the molecular basis of obesity-related breast carcinogenesis remains elusive. In this study, we have shown that obesity reduces the level of the tumor suppressor p16INK4A protein in breast adipocytes, which showed active features and strong procarcinogenic potential both in vitro and in orthotopic tumor xenografts compared to mature adipocytes from lean women. Furthermore, obesity triggered epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in breast ductal epithelial cells. Interestingly, specific downregulation of p16INK4A increased the expression/secretion levels of various adipokines, including leptin, and activated breast adipocytes from lean women. Consequently, like breast adipocytes from obese women, p16-deficient adipocytes induced EMT in normal primary breast luminal cells in a leptin-dependent manner and enhanced tumor growth. Additionally, we have shown that p16INK4A negatively controls leptin at the mRNA level through microRNAs 141 and 146b-5p (miR-141 and miR-146b-5p), which bind the leptin mRNA at a specific sequence in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR). These results show that obesity activates breast stromal adipocytes through p16 downregulation, which upregulates leptin and promotes procarcinogenic processes.

KEYWORDS: adipocytes, breast cancer, obesity, p16

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related death in women worldwide (1, 2). In recent years, multiple reports have shown obesity as a serious risk factor for the development of breast cancer (3). However, the link between obesity and this deadly disease remains unclear. Therefore, unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying obesity-related breast carcinogenesis may help improve the prevention of breast cancer and/or the treatment of patients.

Adipocytes, which accumulate with obesity, are the major components in the breast microenvironment, and along with their secreted factors, they represent key players in stroma-epithelium interactions (4). As an important paracrine mediator, the adipokine leptin, encoded by the LEP gene, has been correlated with breast cancer occurrence (5–7). Leptin exerts its biological functions through binding to its receptor (obesity receptor [OBR]), which activates multiple downstream signaling pathways such as JAK2/STAT3, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT (8). Through autocrine, endocrine, and paracrine effects, leptin may modulate many aspects of breast tumorigenesis from initiation and primary tumor growth to metastatic progression. Moreover, leptin is able to shape the tumor microenvironment within the mammary gland by inducing multiple concurrent events, such as migration of endothelial cells, angiogenesis, and recruitment of macrophages and monocytes (6, 9).

It is still unclear how the expression/secretion of these adipokines is regulated. In breast stromal fibroblasts, it has been shown that tumor suppressor genes, such as p16INK4A (p16), play major roles in repressing the expression/secretion of several cancer-promoting cytokines (10).

p16 is a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor (CDKI) encoded by the CDKN2A gene (11, 12). In the absence of p16, both mice and humans are predisposed to cancer, and the gene is frequently inactivated in many tumor types, which shows the important role of this gene in tumor suppression (13–16). Additionally, p16 has a non-cell-autonomous tumor-suppressive function and also regulates the expression of several genes (17, 18). We have recently shown that p16 negatively regulates AUF1 through positive control of microRNA (miRNA) 141 (miR-141) and miR-146b-5p, which repress AUF1 expression (17, 19, 20). miR-141 and miR-146b-5p are two important tumor suppressor microRNAs which control several cancer-related genes and processes, such as the prometastatic epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process (19, 21, 22).

We have shown in the present report that adipocytes from obese women are active and express low levels of p16. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that p16 downregulation activates breast stromal adipocytes and enhances their procarcinogenic effects in a leptin-dependent manner. This p16-dependent repression of leptin is mediated through miR-141 and miR-146b-5p. Additionally, we provide clear evidence that obesity induces EMT in breast epithelial cells both in vitro and in vivo.

RESULTS

Generation and characterization of mature adipocytes from cancer-free breast tissues.

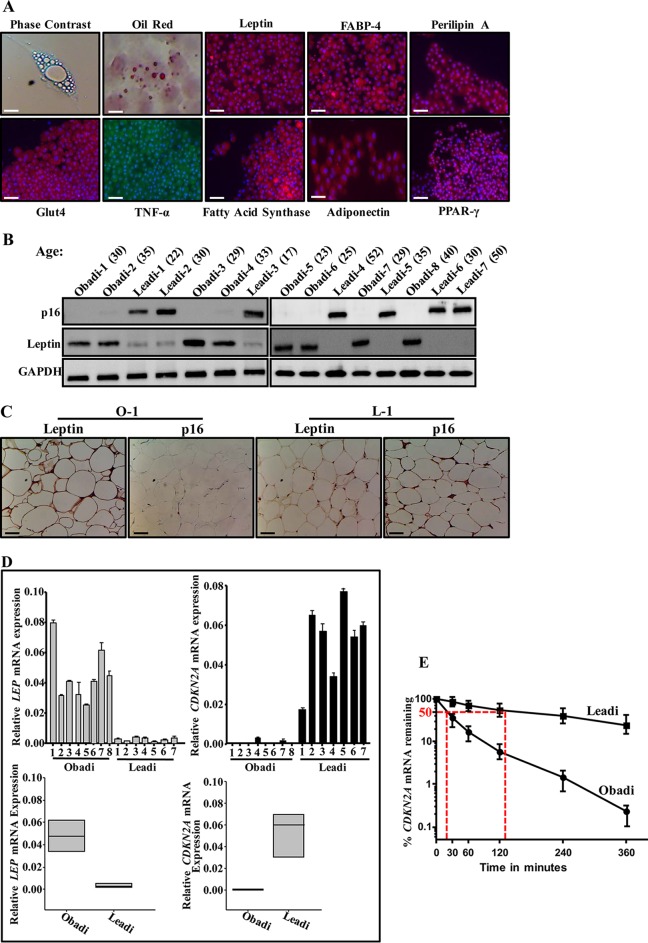

Adipose tissues were obtained from 15 breast tissues derived from healthy cancer-free women who underwent mammoplasty (8 obese patients, having a body mass index [BMI] of ≥30, and 7 lean patients, having a BMI of <30) with mean ages of 30.5 and 32.2, respectively. Adipose tissues were processed, and preadipocytes were cultured; when confluent, they were induced to differentiate into mature adipocytes. Under these conditions, cells became larger, and the cytoplasm gradually increased and accumulated small lipid droplets, which were visualized by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 1A). These adipocytes also stained positive for other differentiated-adipocyte markers, namely, leptin, FABP4, perilipin A, GLUT-4, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), fatty acid synthase, adiponectin, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPAR-γ) (Fig. 1A). This indicates that adipocytes were well separated from the other stromal cells and differentiated and therefore were considered to be highly homogenous with minimal contamination.

FIG 1.

Breast adipocytes from obese females express low levels of p16 and high levels of leptin. (A) Mature adipocytes were subjected to cytospins, stained with Oil Red O or fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and then used for immunofluorescence utilizing the indicated antibodies. (B) Cell extracts were prepared from the indicated adipocytes and used for immunoblotting. (C) Immunohistochemistry for the indicated FFPE adipose tissues using antibodies against the indicated proteins. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D) Total RNA was prepared from the indicated adipocytes and utilized to assess the level of the indicated genes by qRT-PCR (upper panels) and the mean values of all Obadi and all Leadi cells (lower panels). Error bars represent means ± SD from three independent experiments. (E) Breast adipocytes from three lean and three obese females were treated with actinomycin D for the indicated periods of time. Total RNA was prepared, and the remaining amount of the CDKN2A mRNA was assessed by qRT-PCR. The values at time zero were considered 100%. The dashed lines reveal the half-life (50% mRNA remaining) using regression analysis. Error bars represent means ± SD from three independent experiments.

p16 is downregulated in breast stromal adipocytes derived from obese cancer-free females.

The p16 expression was first assessed in differentiated adipocytes derived from obese women (Obadi-1 to -8 cells) and lean women (Leadi-1 to -7 cells), which were used simultaneously at low passage numbers (2 to 4 passages postdifferentiation). Whole-cell extracts were prepared, and specific anti-p16 antibody was utilized for immunoblotting using anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) antibody as an internal control. Figure 1B shows that the level of p16 is much lower in all Obadi cells than in Leadi cells, independently of the age of the females. In contrast, the level of leptin was higher in all Obadi cells than in Leadi cells (Fig. 1B). Similarly, p16 was found downregulated and leptin was upregulated in 15 adipose tissues derived from obese women compared to levels in those derived from lean women (Fig. 1C).

Next, we assessed the level of the CDKN2A and LEP mRNAs in the same cells by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR). To this end, total RNA was prepared, and specific primers for CDKN2A, LEP, and GAPDH (used for normalization) were utilized for amplification. The data in Fig. 1D show a strong decrease in the CDKN2A mRNA level in Obadi cells compared with the level in Leadi cells, while the level of the LEP mRNA was higher in Obadi than in Leadi cells. This shows that the levels of the CDKN2A and LEP mRNAs reflect that of the corresponding proteins in normal adipocytes, indicating that the decrease in the p16 protein level in Obadi cells is due, at least in part, to a decrease in the level of its corresponding transcript. In addition, these results indicate the presence of a negative correlation between p16 and leptin in breast stromal adipocytes (BSAd).

To investigate whether obesity has a role in the stability of the CDKN2A mRNA in BSAd, three Obadi and three Leadi cell cultures were treated with the transcription inhibitor actinomycin D and then reincubated for different periods of time (0 to 6 h). Total RNA was prepared, and the mRNA level of CDKN2A was assessed by qRT-PCR. Figure 1E shows that the CDKN2A mRNA is more stable in Leadi cells than in Obadi cells. Indeed, while the CDKN2A mRNA half-life in Leadi cells was 135 min, it was only 18 min in Obadi cells. This shows that obesity plays a major role in the destabilization of the CDKN2A mRNA in normal human BSAd.

Obadi cells have higher migration, invasion, and proliferation capabilities and secrete higher levels of adipokines than Leadi cells.

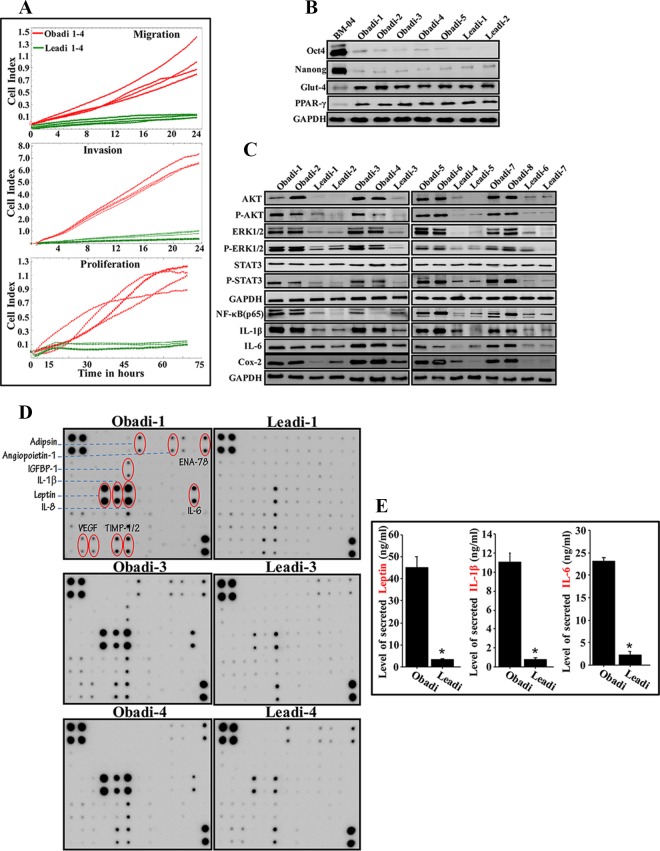

Next, the migration and invasion as well as proliferation capabilities of Obadi and Leadi cells (4 each) were assessed using an xCelligence system. The experiment shown in Fig. 2A demonstrates that Obadi cells have stronger migration/invasion and proliferation capabilities than Leadi cells. To confirm that these cells are indeed mature adipocytes and did not dedifferentiate to mesenchymal stem cells, we assessed the expression levels of some relevant markers. Figure 2B shows that five Obadi and two Leadi cells expressed very low levels of the pluripotency markers Oct4 and Nanog compared to the levels in mesenchymal stem cells (BM-04). On the other hand, while BM-04 cells expressed very low levels of the mature adipocyte markers Glut-4 and PPAR-γ, Obadi and Leadi cells expressed high levels of these two proteins (Fig. 2B).

FIG 2.

Breast adipocytes from obese females are active. (A) Adipocytes (Obadi-1 to -4 and Leadi-1 to -4) were seeded in SFM in the upper wells of the CIM plates, and the migration/invasion abilities were assessed for 24 h. For proliferation, adipocytes were seeded in complete medium in the E-plate, and the proliferation rate was assessed by the xCELLigence RTCA system. (B and C) Cell extracts were prepared from the indicated adipocytes and used for immunoblotting. (D) SFCM from the indicated adipocytes was applied onto human adipokine array membranes. The circles indicate cytokines with higher levels in Obadi than in Leadi adipocytes. (E) SFCM from three Obadi and three Leadi cells was utilized to assess the level of the indicated adipokines by ELISA. Error bars represent means ± SD of values from three Obadi and three Leadi cells from three different experiments. *, P ≤ 0.00021.

Figure 2C shows that the expression levels of total and active/phosphorylated forms of the proinvasive/migratory and proliferative protein kinases AKT and extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2) (23, 24) were very high in Obadi cells compared to levels in Leadi cells. In addition, the expression level of phospho-STAT3 (P-STAT3), the transmitter of leptin signaling (25), but not total STAT3 was higher in Obadi cells than in Leadi cells (Fig. 2C).

Furthermore, serum-free conditioned medium (SFCM) was collected from three Obadi and three Leadi cells and then applied to Ray Bio human adipokine antibody arrays. Great differentials in the levels of various adipokines were observed between Obadi and Leadi cells, including, leptin, interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-8, IL-6, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Fig. 2D). This result was confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), which showed that Obadi cells secrete higher levels of leptin, IL-1β, and IL-6 than Leadi cells (Fig. 2E). Figure 2C shows that the levels of the NF-κB (p65), IL-1β, IL-6, and Cox-2 proteins were significantly higher in Obadi than in Leadi cells, which shows the proinflammatory status of Obadi cells. Together, these results imply that breast adipocytes derived from obese women are active and may exhibit procarcinogenic effects.

Obadi cells enhance the migratory and the invasive abilities of primary human breast luminal cells in a paracrine fashion.

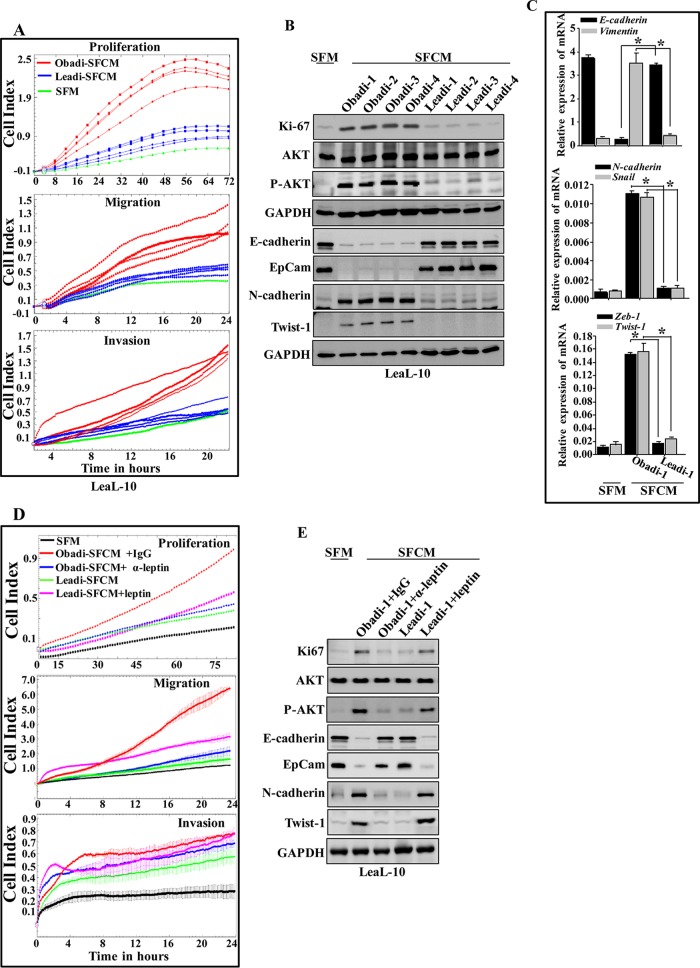

To confirm the active status of Obadi cells, we investigated the possible paracrine procarcinogenic effects of Obadi cells on normal breast luminal cells (LeaL-10 cells). To this end, SFCM from four Obadi and four Leadi cells was collected after 48 h of incubation and applied onto exponentially growing LeaL-10 cells for 24 h (serum-free medium [SFM] was used as a negative control), and their proliferation rates as well as their migration/invasion capabilities were measured. Figure 3A shows that cells treated with SFCM from Obadi cultures (Obadi-SFCM) strongly increased the proliferation rate as well as the migration/invasion capacities of LeaL-10 cells compared to levels with Leadi-SFCM treatment, which had only a minor effect on their proliferation compared to treatment with SFM. Furthermore, SFCM from Obadi cells strongly increased the level of Ki-67 compared to treatment with SFM, whereas SFCM from Leadi cells had no effect. In addition, whereas SFCM from both types of adipocytes had no effect on the expression level of total AKT, SFCM from Obadi cells strongly enhanced the level of the active/phosphorylated form of this protein kinase. However, SFCM from Leadi cells had only a slight effect on the phosphorylation of AKT (Fig. 3B). This indicates that Obadi cells enhance the proliferation and migration/invasion abilities of normal breast luminal cells through the activation of AKT in a paracrine manner.

FIG 3.

Breast adipocytes from obese females promote EMT and tumor growth. LeaL-10 cells were exposed to SFM or SFCM from four Obadi and four Leadi cells for 24 h. (A) The migration/invasion and proliferation capabilities were assessed. The graphs are representative of different experiments. (B) Cell lysates were prepared and used for immunoblotting. (C) Total RNA was prepared from LeaL-10 cells grown in 3D cultures and used to assess the level of the indicated transcripts by qRT-PCR. Error bars represent means ± SD of values from three different experiments. *, P ≤ 2.33 × 10−5. (D and E) LeaL-10 cells were exposed to SFM, SFCM from Obadi-1 cells containing either antileptin or anti-IgG antibodies, or SFCM from Leadi-1 cells containing the human leptin protein for 24 h and then were utilized to assess the migration/invasion and proliferation capabilities (the graphs are representative of different experiments) or the levels of the indicated proteins by immunoblotting.

Obadi cells stimulate EMT in normal breast luminal cells in a leptin-dependent manner.

Upon exposure of LeaL-10 cells to SFCM from Obadi cells, the levels of the epithelial markers E-cadherin and epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCam) were strongly reduced, and the levels of the mesenchymal N-cadherin and Twist-1 proteins were potently increased compared to levels with SFM treatment (Fig. 3B). However, SFCM from Leadi cells had only marginal effects on the levels of these proteins (Fig. 3B).

To simulate the in vivo situation and the presence of the basement membrane, LeaL-10 cells were grown in three-dimensional (3D) cultures in a network containing a mesh (basement membrane mimic), which separated cells from Obadi-SFCM, Leadi-SFCM, or SFM for 48 h, and then RNA was purified and used for qRT-PCR. Figure 3C shows a clear decrease in the expression of E-cadherin and a clear increase in the expression of N-cadherin, vimentin, Snail, Zeb-1, and Twist-1 in cells cultured with Obadi-SFCM compared to levels in control cells (SFM). However, the expression levels of these EMT-related transcripts did not change in cells cultured with Leadi-SFCM compared to levels in control cells. This indicates that secreted factors can penetrate the basement membrane and affect luminal cells cultured in 3D. Together, these results indicate that Obadi cells enhance the carcinogenesis of normal breast luminal cells through induction of the EMT process in a paracrine manner.

In an attempt to investigate the possible role of leptin in the paracrine pro-EMT effect of Obadi cells in luminal cells, SFCM from Obadi cells was challenged with either anti-IgG antibody or antileptin neutralizing antibody and applied onto the LeaL-10 cells for 24 h. Figure 3D and E show that leptin inhibition suppressed the effect of Obadi-SFCM in enhancing the migration/invasion as well as the proliferative abilities of LeaL-10 cells. In addition, the EMT-triggering effect of Obadi-SFCM was normalized by inhibiting leptin (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, adding pure recombinant human leptin protein to Leadi-SFCM strongly enhanced the migration/invasion as well as proliferation abilities of LeaL-10 cells compared to those with Leadi-SFCM treatment (Fig. 3D) and activated the EMT process in LeaL-10 cells (Fig. 3E). This shows that the paracrine procarcinogenic effects of Obadi cells is mediated through increased leptin secretion.

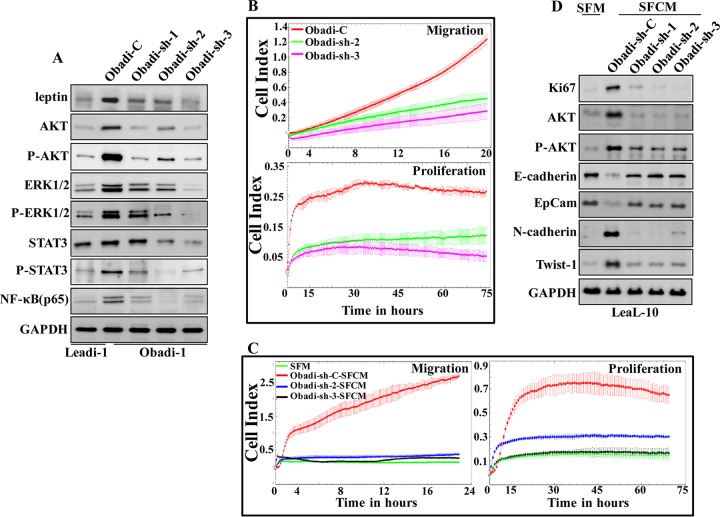

To investigate the possible role of leptin in the activation of mature adipocytes, leptin was downregulated in Obadi-1 cells using a specific short hairpin RNA (shRNA), and a scrambled sequence was used as control. The generated cells (Obadi-sh and Obadi-C, respectively) were used to prepare whole-cell lysates, and the level of the leptin protein was assessed by immunoblotting using whole-cell lysates from Leadi-1 cells as a control. Figure 4A shows a strong reduction in the level of the leptin protein in Obadi-sh cells compared to levels in their control counterparts, with the level in Obadi-sh cells level similar to that observed in Leadi-1 cells. Figure 4B shows that downregulation of leptin in Obadi-1 cells decreased their migration and proliferation compared to those of their control counterparts. Furthermore, the levels of AKT/P-AKT, ERK/P-ERK1/2, STAT3/P-STAT3, and NF-κB (p65) were also reduced in Obadi-sh cells compared to those in Obadi-C cells and reached levels similar to those observed in Leadi-1 cells (Fig. 4A). This implies that leptin activates the proliferative and migratory abilities of adipocytes through the activation of the STAT3, AKT, and ERK1/2 pathways.

FIG 4.

Obadi cells stimulate EMT in normal breast luminal cells through leptin. (A) Obadi-1 cells were transfected separately with either one of three different sequences of shRNAs targeting LEP (Obadi-sh-1, -2, or -3) or the control plasmid (Obadi-C), and cell lysates were used for immunoblotting. (B) The graphs are representative of different experiments. (C and D) LeaL-10 cells were exposed to SFM or SFCM from Obadi-sh or Obadi-C cells for 24 h and then collected, and the migration and proliferation capabilities were assessed (the graphs are representative of different experiments) or utilized to prepare cell lysates to assess the levels of the indicated proteins by immunoblotting.

Next, SFCM was collected from Obadi-sh-2, Obadi-sh-3, and Obadi-C cells and applied onto LeaL-10 cells for 24 h in order to test the paracrine effects. SFM was used as a negative control. Figure 4C shows that while SFCM from Obadi-C cells strongly increased the proliferation rate and the migration capability of LeaL-10 cells, SFCM from Obadi-sh-2 and Obadi-sh-3 decreased these abilities. Additionally, while SFCM from Obadi-C cells induced EMT, SFCM from Obadi-sh cells had an effect similar to that of SFM (Fig. 4D). Similar results were obtained for the proliferative marker Ki-67 and the proinvasive kinase AKT (Fig. 4D). This indicates that leptin stimulates the procarcinogenic effects of breast stromal adipocytes.

Obadi cells stimulate breast cancer xenograft growth in mice.

SCID female mice (n = 20) were randomized into five groups, and breast cancer orthotopic xenografts were created under nipple by coimplantation of MDA-MB-231 cells (2 × 106) with Obadi or Leadi cells (2 × 106). As a control MDA-MB-231 cells (2 × 106) were injected alone. Although all mice coinjected with MDA-MB-231 and adipocytes developed tumors 2 weeks after injection, tumors containing Obadi cells (T-Obadi) grew faster than those containing Leadi cells (T-Leadi) (Fig. 5A). However, injection of MDA-MB-231 alone did not result in any tumors. These results show that Obadi cells can promote breast cancer formation and growth in SCID mice.

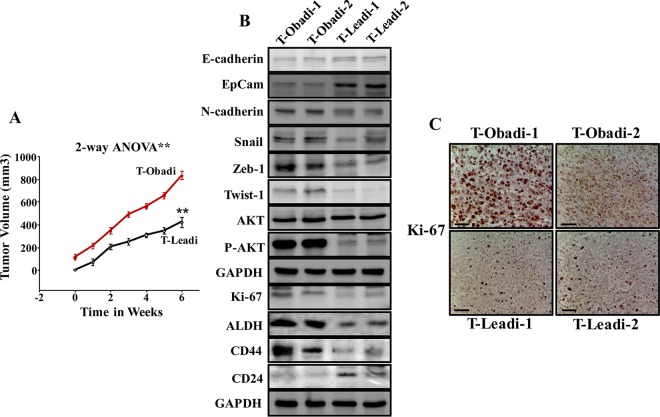

FIG 5.

Obadi cells stimulate breast cancer xenograft growth in mice. (A) Breast cancer xenografts were created by coinjecting MDA-MB-231 cells with either Obadi or Leadi cells under the nipple of SCID mice. The graph shows time-dependent tumor growth. Error bars represent means ± SD for four mice. Two-way ANOVA was performed to compare results between the Obadi and Leadi groups. **, P = 0.000128. (B) Tumors were excised, and whole-tissue lysates were prepared and utilized for immunoblotting. (C) Immunohistochemistry for the indicated FFPE tissues using anti-Ki-67 antibody. Scale bars, 50 μm.

To further elucidate the role of Obadi cells in tumor growth, whole-cell extracts were prepared from T-Obadi-1, T-Obadi-2, T-Leadi-1, and T-Leadi-2 cells, and the levels of various EMT-related proteins were assessed by immunoblotting. While the levels of the epithelial markers E-cadherin and EpCam were much higher in T-Leadi than in T-Obadi tumors, the levels of the mesenchymal N-cadherin, Snail, Zeb-1, and Twist-1 proteins were much higher in T-Obadi than in T-Leadi tumors. In addition, whereas the total levels of the AKT protein were similar in all four tumors, the level of the phosphorylated form of the protein was much higher in T-Obadi tumors than in T-Leadi tumors. Also, the level of the Ki-67 protein was much higher in T-Obadi than in T-Leadi tumors (Fig. 5B and C), which explains the faster growth of T-Obadi tumors.

Induction of EMT results in cells that have acquired many of the attributes of stem cells (23); therefore, we assessed the levels of the main mammary stem cell markers aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), CD44, and CD24 by immunoblotting. Figure 5B shows that while the levels of the ALDH and CD44 proteins were much higher in T-Obadi than in T-Leadi tumors, the level of the CD24 protein was lower in T-Obadi than in T-Leadi tumors. This indicates an Obadi-dependent increase in markers of mammary cancer stem cells (CSC) within the formed orthotopic tumor xenografts although immunoblotting does not reveal what cell type these changes occurred in. Together, these results show that adipocytes from obese females are active and procarcinogenic both in vitro and in vivo.

Obesity promotes EMT in breast ductal epithelial cells.

To investigate the possible effect of adipocytes on breast ductal epithelial cells in vivo, 10 formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast tissues (five from obese and five from lean women) were utilized to assess the expression of EMT markers by immunofluorescence. Figure 6A shows that while ducts in breast tissues originating from lean women (L-2) stained positive for EpCam and negative for vimentin, ducts obtained from obese women (O-1) stained positive for vimentin but expressed low levels of EpCam. The level of Ki-67 was also higher from breast ducts of obese women than from those of lean ones (Fig. 6B).

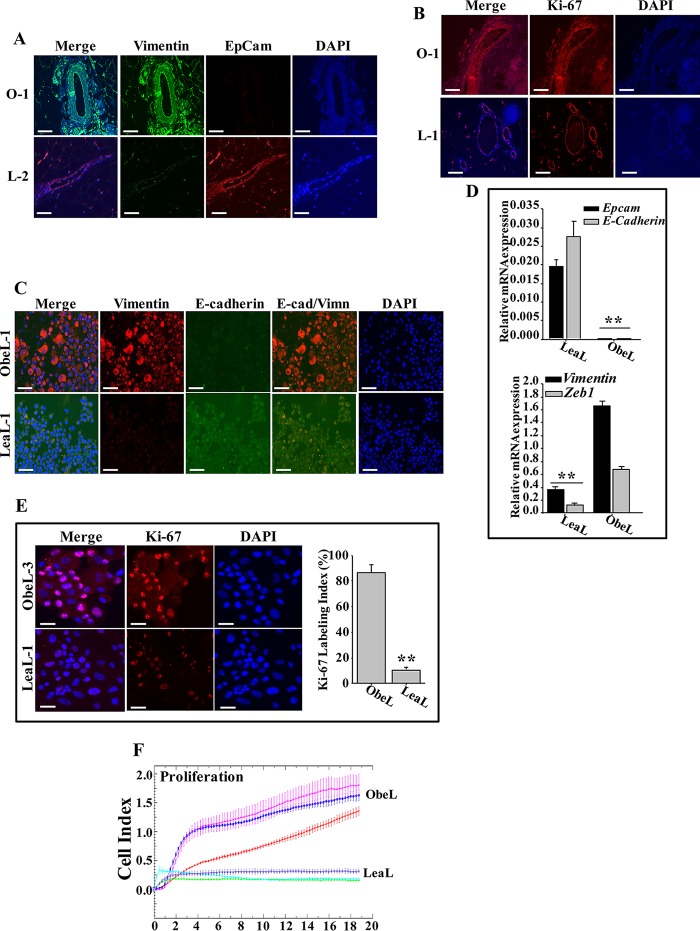

FIG 6.

Obesity promotes EMT in breast epithelium. (A and B) Immunofluorescence for the indicated FFPE breast tissues. Scale bar, 50 μm. (C and E) Normal breast luminal cells were subjected to cytospins and used for immunofluorescence. Scale bars, 50 μm. The histogram shows the mean Ki-67 labeling index for three ObeL and three LeaL cells. Error bars represent means ± SD of values from three independent experiments. **, P ≤ 0.000457. (D) Total RNA from three LeaL and three ObeL luminal cells was utilized to assess the level of the indicated genes by qRT-PCR. Values are the means ± SEM (n = 3). Error bars represent means ± SD of values from three independent experiments. **, P = 0.000174. (F) Three ObeL and three LeaL cells were seeded in complete medium in the E-plate, and the proliferation rate was assessed. The graph is representative of different experiments.

Next, we assessed EMT in breast ductal luminal cells isolated from three obese (ObeL cells) and three lean (LeaL cells) women by immunofluorescence. Figure 6C shows that ObeL-1 cells stained positive for vimentin but not for E-cadherin. However, LeaL-1 cells stained negative for vimentin but positive for E-cadherin. The mRNA level of EMT-related markers was also assessed in ObeL and LeaL cells by qRT-PCR. Figure 6D shows that while the levels of the epithelial markers E-cadherin and EpCam were higher in LeaL cells than in ObeL cells, the levels of the mesenchymal markers vimentin and Zeb-1 were higher in ObeL than in LeaL cells. Ki-67 was also 9-fold higher in ObeL than in LeaL cells (Fig. 6E). In addition, the proliferation rate of ObeL cells was much higher than that of LeaL cells (Fig. 6F).

Together, these data indicate that obesity triggers EMT in breast ductal epithelial cells in vivo and in primary normal luminal cells in vitro.

Downregulation of p16 activates mature breast adipocytes and enhances their inflammatory response.

To investigate the possible role of p16 downregulation in the activation of mature adipocytes, p16 was downregulated in three Leadi cells using a specific shRNA, and a scrambled sequence was used as a control. The generated cells (Leadi-sh and Leadi-C, respectively) were used to prepare whole-cell lysates, and the level of the p16 protein was assessed by immunoblotting. Figure 7A shows a strong reduction in the level of p16 and upregulation of leptin in Leadi-sh cells compared to levels in their control counterparts.

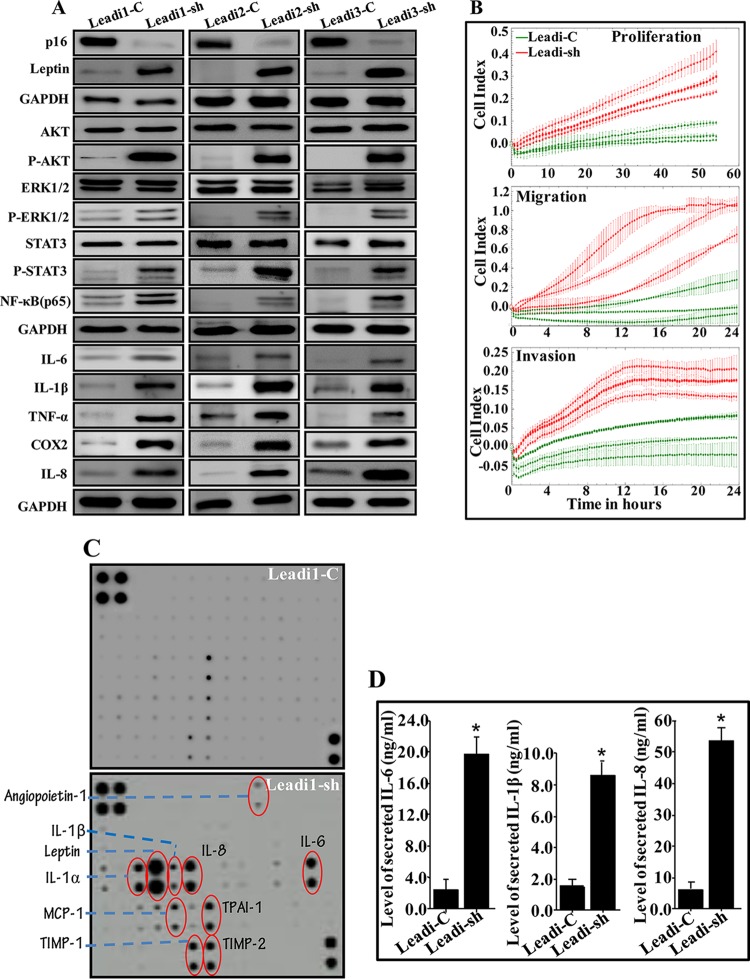

FIG 7.

p16 downregulation activates Leadi cells. (A) Mature adipocytes from three Leadi cells were transfected with either an shRNA targeting CDKN2A (Leadi-sh) or the control plasmid (Leadi-C), and cell lysates were prepared and used for immunoblotting. (B) Cells were tested for their proliferation and migration/invasion capacities. The graphs are representative of different experiments. (C) SFCM from the indicated cells was collected after 48 h and applied onto human adipokine antibody array membranes. The circles indicate cytokines with higher levels in Leadi1-sh than in Leadi1-C cells. (D) SFCM was collected from three Leadi-C and three Leadi-sh cells and then utilized to assess the level of the highly secreted adipokines by ELISA. Error bars represent means ± SD of values from three Leadi-C and three Leadi-sh cells from three independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.0012.

Furthermore, downregulation of p16 in Leadi cells increased their proliferation, migration, and invasion compared to levels in the controls (Fig. 7B). While downregulation of p16 had no effect on the levels of total AKT, ERK1/2, and STAT3, the levels of the active/phosphorylated forms of these kinases were strongly increased (Fig. 7A). Figure 7A also shows that the levels of NF-κB (p65), IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, Cox-2 and IL-8 were significantly higher in Leadi-sh cells than in Leadi-C cells. Similarly, the adipokine array shows that p16 downregulation strongly increased the levels of several secreted adipokines, including leptin, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-8, TPAI-1, MCP-1, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 (Fig. 7C). This result was confirmed by ELISA, which showed that downregulation of p16 in Leadi cells increased the secretion of IL-6, IL-1β, and IL-8 compared to levels in control cells (Fig. 7D). This suggests that p16 represses the expression/secretion of procarcinogenic/proinflammatory proteins in breast stromal adipocytes.

p16-deficient adipocytes stimulate EMT in primary normal breast luminal cells in a leptin-dependent manner.

To confirm the active status of p16-defective Leadi cells, we investigated the paracrine effect of Leadi-sh cells on normal breast luminal cells. Figure 8A shows that while SFCM from Leadi-C cells had only a slight effect, SFCM from Leadi-sh adipocytes strongly increased the proliferation rate and the migration/invasion capabilities of LeaL-10 cells. Additionally, while SFCM from Leadi-C cells had only marginal effects, SFCM from Leadi-sh cells strongly induced the EMT process compared to the effect with SFM (Fig. 8B). This indicates that p16 represses the procarcinogenic effects of adipocytes by inhibiting the paracrine pro-EMT process.

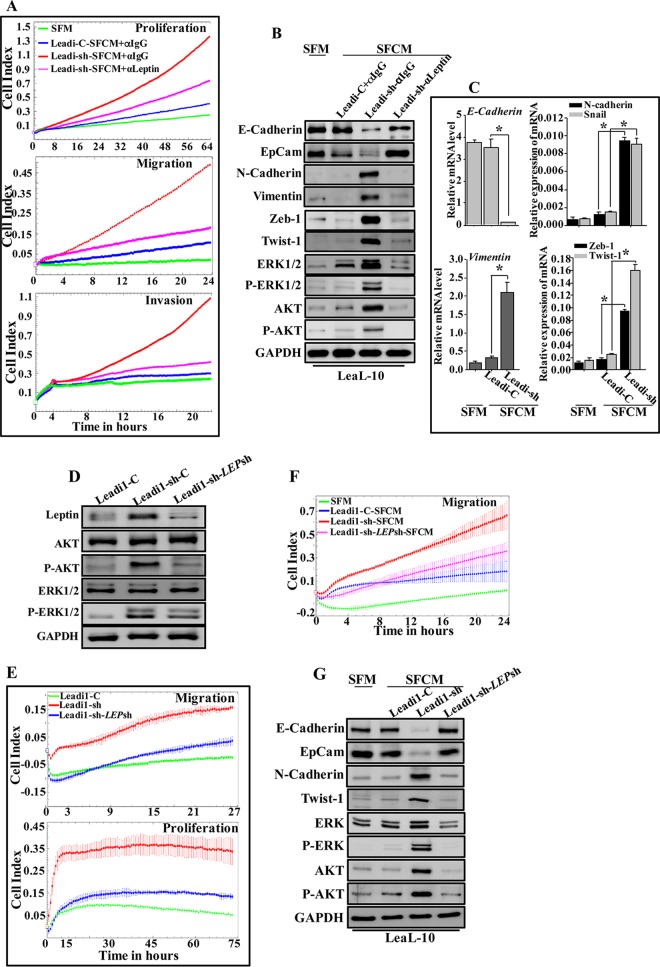

FIG 8.

p16-deficient adipocytes stimulate EMT in a leptin-dependent manner and enhance tumor growth in vivo. LeaL-10 cells were cultured with either SFM or SFCM from Leadi-C or Leadi-sh cells containing either antileptin or anti-IgG antibodies for 24 h. (A) Cell proliferation, migration, and invasion capabilities were assessed. Values are representative of different experiments. (B) Cell lysates were prepared from the indicated cells and used for immunoblotting. (C) The experiment shown was performed as described in the legend to Fig. 3E. (D) Leadi1-sh cells were transfected with either specific leptin shRNA (Leadi1-sh-LEPsh) or the control plasmid (Leadi1-sh-C), and whole-cell lysates were prepared and used for immunoblotting. (E) Leadi1-C, Leadi1-sh-C, and Leadi1-sh-LEPsh cells were seeded in either complete medium in the E-plate to assess their proliferation rate or in SFM in the CIM plate to assess their migration capacity. Each assay was performed in triplicate. The graphs are representative of different experiments. (F) LeaL-10 cells were cultured with either SFM or SFCM from Leadi1-sh-C or Leadi1-sh-LEPsh cells for 24 h, and the migration capability was assessed. The graph is representative of independent experiments. (G) Cell lysates were prepared from the indicated cells and used for immunoblotting.

Next, LeaL-10 cells were grown in 3D cultures in a network containing a mesh, which separated cells from Leadi-sh-SFCM, Leadi-C-SFCM, or SFM for 48 h, and then RNA was purified and used for qRT-PCR. Figure 8C shows a clear decrease in the expression of E-cadherin and a clear increase in the expression levels of N-cadherin, vimentin, Snail, Zeb-1, and Twist-1 in cells cultured with Leadi-sh-SFCM compared to levels in control cells (SFM). However, the expression levels of these EMT-related transcripts did not change in cells cultured with Leadi-C-SFCM compared to control cell levels. This indicates that Leadi-sh-SFCM-secreted factors can penetrate the basement membrane and affect luminal cells grown in 3D.

In an attempt to investigate the possible implication of leptin in the paracrine pro-EMT effect of p16-deficient BSAd, SFCM from Leadi-sh cells was challenged with either anti-IgG antibody or with antileptin neutralizing antibody and applied onto the LeaL-10 cells for 24 h. Figure 8B shows that leptin inhibition suppressed the effect of Leadi-sh-SFCM in triggering EMT and enhancing the migratory/invasive and proliferative abilities of LeaL-10 cells. This shows that the paracrine procarcinogenic effects of p16 deficiency are mediated through increased leptin secretion from BSAd.

To further confirm the implication of leptin in the paracrine pro-EMT effect of p16-deficient BSAd, Leadi1-sh cells were first transfected with a plasmid bearing leptin-shRNA-3 (Leadi1-sh-LEPsh) or scrambled sequence (Leadi1-sh-C) as a control. Figure 8D shows a strong reduction in the level of the leptin protein in Leadi1-sh-LEPsh cells compared to the control level. Figure 8E shows that downregulation of leptin in Leadi1-sh cells decreased their migration and proliferation abilities compared to those of their control counterparts and became similar to those of Leadi1-C cells. Furthermore, while downregulation of leptin had no effect on the level of total AKT and ERK1/2, the levels of the active/phosphorylated forms of these kinases were strongly decreased (Fig. 8D). This implies that p16 represses the proliferative/migratory abilities of adipocytes through targeting leptin and the inhibition of the AKT and ERK1/2 pathways.

We next showed that exposure of LeaL-10 cells to SFCM from Leadi1-sh-LEPsh decreased their migration ability compared to that of Leadi1-sh-C cells and resulted in a level similar to that observed upon exposure to SFCM from Leadi1-C cells (Fig. 8F). Additionally, the levels of the epithelial markers E-cadherin and EpCam were strongly increased, and the levels of the mesenchymal marker proteins N-cadherin and Twist-1 were potently reduced compared to levels in cells treated with SFCM from Leadi1-sh (Fig. 8G). This shows that the paracrine procarcinogenic effects of p16 deficiency are mediated through increased leptin secretion from BSAd.

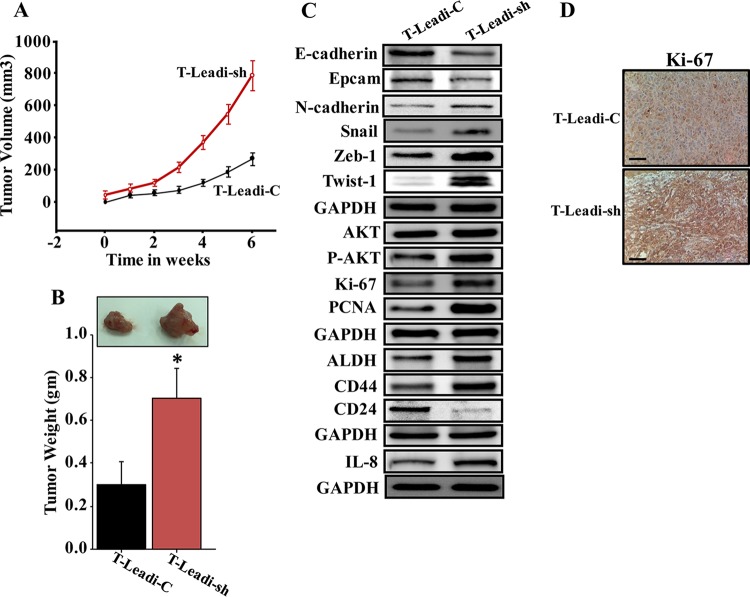

p16-deficient Leadi cells stimulate the growth of orthotopic xenografts in mice.

To investigate the effect of p16 downregulation in Leadi cells on tumor growth in vivo, 15 SCID female mice were randomized into three groups, and breast cancer xenografts were created under nipple by coimplantation of MDA-MB-231 cells (2 × 106) with Leadi-sh (T-Leadi-sh) or Leadi-C cells (T-Leadi-C) (2 × 106). As a control 2 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells were injected alone. Although all mice coinjected with MDA-MB-231 and adipocytes developed tumors 2 weeks after injection, T-Leadi-sh tumors grew faster (Fig. 9A) and formed bigger tumors (Fig. 9B) than T-Leadi-C tumors. No tumors were obtained by injecting MDA-MB-231 cells alone. These results show that p16 downregulation in Leadi cells stimulates their procarcinogenic effects and promotes breast cancer formation in vivo. Interestingly, Leadi-sh adipocytes increased the expression of the proliferative markers Ki-67 and PCNA and enhanced EMT and stemness in breast cancer cells (Fig. 9C and D). Together, these data indicate that downregulation of p16 in Leadi cells activates these cells and enhances their procarcinogenic effects in vivo.

FIG 9.

p16-deficient Leadi cells stimulate the growth of orthotopic xenografts in mice. Breast cancer xenografts were created by coinjecting MDA-MB-231 cells with either Leadi-sh or Leadi-C cells under the nipple of SCID mice. (A) The graph shows the time-dependent tumor growth. Error bars represent means ± SD. (B) Representative tumor size (top) and tumor weight (bottom). Error bars represent means ± SD of values from four mice. *, P = 0.014. (C and D) The experiment is as described in the legends of Fig. 5B and C.

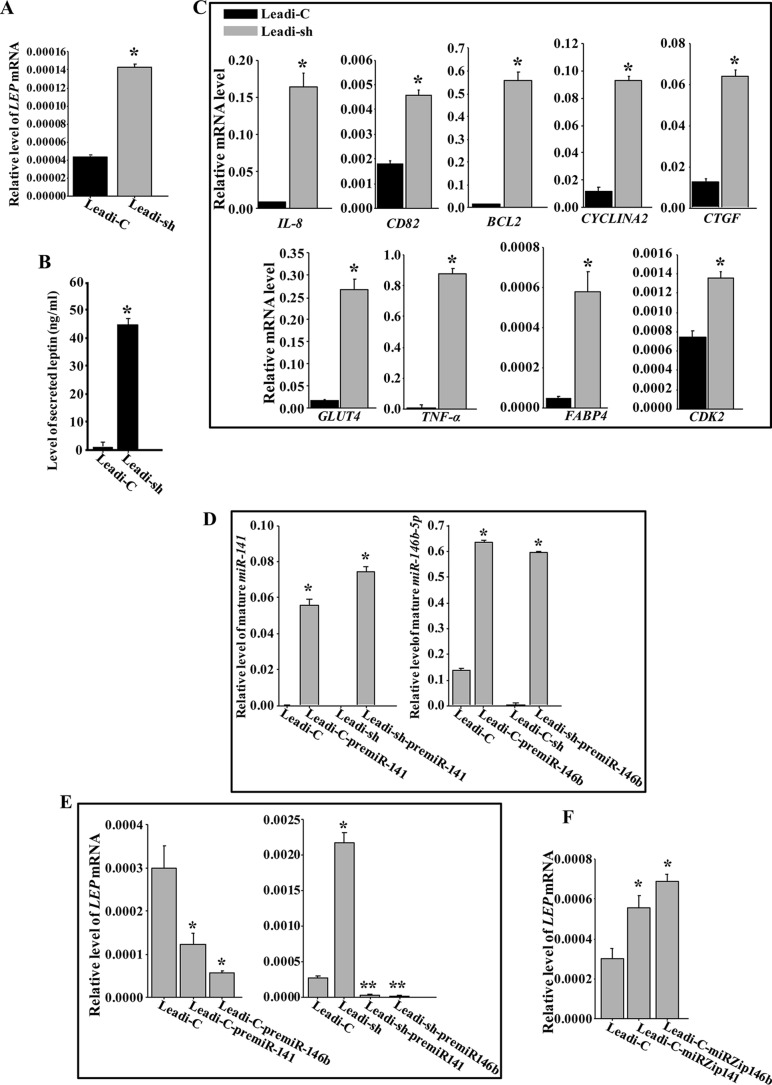

p16 negatively regulates the expression of leptin.

To further elucidate the molecular and functional link between p16 and leptin, we assessed the level of the LEP mRNA in Leadi-sh and Leadi-C adipocytes by qRT-PCR. Figure 10A shows that the downregulation of p16 increased the level of the LEP mRNA 3.5-fold, suggesting that p16 represses the expression of leptin at the transcriptional/posttranscriptional level. Moreover, p16 downregulation significantly increased the secreted level of leptin (45-fold) (Fig. 10B). Furthermore, downregulation of p16 in Leadi cells significantly upregulated several leptin targets, including IL-8, TNF-α, and BCL-2.

FIG 10.

p16 suppresses the expression and secretion of leptin through targeting miR-141 and miR-146b-5p. (A and C to F) Total RNA from Leadi-sh and Leadi-C cells expressing the indicated constructs was utilized to assess the indicated transcripts by qRT-PCR. (B) SFCM from the indicated cells was used to assess the level of the secreted leptin by ELISA. Error bars represent means ± SD of values from three independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.0002; **, P ≤ 0.000022.

miR-141 and miR-146b-5p mediate the p16-negative regulation of leptin in adipocytes.

To investigate the possible implication of miR-141 and miR-146b-5p microRNAs in the p16-dependent negative regulation of leptin, Leadi-C and Leadi-sh cells were transfected with plasmids bearing pre-miR-141, pre-miR-146b-5p, or an empty vector used as control. Figure 10D shows that ectopic expression of pre-miR-141 or pre-miR-146b-5p in Leadi-C or Leadi-sh cells increased the expression of the mature forms of these miRNAs. The expression of pre-miR-141 or pre-miR-146b-5p reduced the level of the LEP mRNA 3-fold in Leadi-C and 27-fold in Leadi-sh cells (Fig. 10E). This indicates that miR-141 and miR-146b-5p are potential negative regulators of leptin and mediate the p16-dependent negative regulation of the gene.

To further evaluate the contribution of miR-141 and miR-146b-5p in the negative regulation of leptin, miR-141 and miR-146b-5p were inhibited by specific anti-miRNAs (miRZips) in Leadi-C cells, which express both miRNAs, and a nonspecific sequence was used as a control. Figure 10F shows that the inhibition of miR-141 or miR-146b-5p increased the level of the LEP mRNA in Leadi-C cells. These results indicate that, like p16, miR-141 and miR-146b-5p negatively regulate leptin expression.

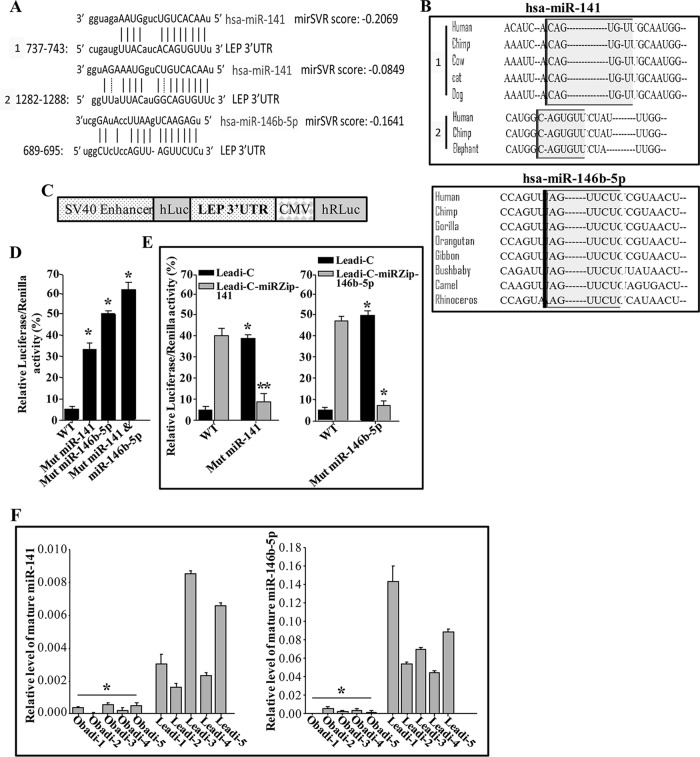

miR-141 and miR-146b-5p control LEP mRNA expression via its 3′ UTR.

The analysis of miRNA databases showed that the LEP 3′ untranslated region (UTR) contains two potential binding sites for miR-141 located at bases 737 to 743 (mirSVR score, −0.2069) and 1282 to 1288 (mirSVR score, −0.0849) and one potential binding site for miR-146b-5p located at bases 689 to 695 (mirSVR score, −0.1641) (Fig. 11A). These regions are highly conserved among different species (Fig. 11B).

FIG 11.

miR-141 and miR-146b-5p repress the expression of leptin. (A) Sequence alignment of human (Homo sapiens [hsa]) miR-141 and miR-146b-5p binding sites in the LEP 3′ UTR. (B) The binding sites of miR-141 and miR-146b-5p in the LEP 3′ UTR in different species. (C) Schematic representation of the luciferase/Renilla reporter vector bearing the LEP 3′ UTR. SV40, simian virus 40; CMV, cytomegalovirus; hLuc and hRLuc, humanized luciferase and humanized Renilla luciferase, respectively. (D and E) Leadi-C adipocytes expressing the indicated constructs were transfected with the luciferase/Renilla reporter vector bearing either the wild-type (WT) LEP 3′ UTR or a mutated sequence for one of the binding sites of miR-141 (residue 737) or miR-146b-5p. The reporter activity was assessed at 48 h posttransfection. Data (means ±SEs; n = 4) are presented as percent change in reporter activity compared with that of the wild-type 3′ UTR (*) or that of the control cells (**). * and **, P < 0.0004. (F) Total RNA from the indicated adipocytes was utilized to assess the levels of the indicated mature miRNAs by qRT-PCR. Error bars represent means ± SD of values from three independent experiments. *, P ≤ 0.000905.

Next, we evaluated the potential contribution of the miR-141 and miR-146b-5p binding sites in the LEP mRNA 3′ UTR to the control of LEP expression. To this end, intact LEP 3′ UTR or mutated sequence for these binding sites was inserted into a luciferase/Renilla reporter vector (Fig. 11C) and introduced into Leadi-C cells. Figure 11D shows that the reporter activity fused to the mutated sequence of the LEP 3′ UTR was significantly increased in Leadi-C cells compared to that of the wild-type sequence. Interestingly, the reporter activity was further increased by mutating the sequences of both the miR-141 and miR-146b-5p binding sites.

Furthermore, the reporter activity was increased compared to the level in the control cells when miR-141 or miR-146b-5p was inhibited in Leadi-C cells (Fig. 11E). This effect was abolished by mutating the putative miR-141 or miR-146b-5p binding sites within the 3′ UTR of the LEP mRNA (Fig. 11E). This indicates that the effect of miR-141 and miR-146b-5p on LEP is mediated through interaction with their seed sequence in the LEP 3′ UTR.

miR-141 and miR-146b-5p levels are reduced in Obadi cells.

Next, total RNA was prepared from five Obadi and five Leadi cells, and the levels of mature miR-141 and miR-146b-5p miRNAs were assessed by qRT-PCR. Figure 11F shows a clear decrease in the levels of these two miRNAs in all Obadi cells compared to those in Leadi cells. This indicates an obesity-related reduction in the levels of miR-141 and miR-146b-5p.

DISCUSSION

Numerous findings have indicated that excess body adiposity is an important risk factor for breast cancer. Three major mechanistic connections have been proposed to explain this link between obesity and increased cancer risk: sex hormone metabolism, insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signaling, and adipose tissue dysfunction (24). Notably, all these signals are interconnected and converge on inflammatory pathways (26). At the cellular level, several studies have underscored the important role of adipocytes and their secreted adipokines in breast carcinogenesis (27). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying this functional interplay remain largely elusive. In the present report, we have first shown that BSAd from obese females (BMI of ≥30) are active, with higher proliferative as well as migratory/invasive capacities than adipocytes from lean females (BMI of <30). These effects were explained by the upregulation/activation of the proinvasive/migratory and proliferative protein kinases AKT and ERK1/2 (23, 24) in Obadi cells, which remained as mature adipocytes, expressing low levels of the mesenchymal stem cell markers Nanog and Oct4. This indicates that Obadi cells acquired higher proliferative and invasive capacities without dedifferentiation, which was previously shown to enhance the proliferative ability of mature adipocytes (28, 29). We have next shown that Obadi cells exhibit proinflammatory features. Indeed, the master inflammation regulator NF-κB was upregulated in all BSAd from obese females, which consequently secreted higher levels of several proinflammatory adipokines such as leptin, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β than BSAd from lean women. This parallels the fact that obesity is tightly linked to inflammation, which is a hallmark of local fat deposition (30–32). Moreover, increasing evidence indicates that obesity is associated with a chronic proinflammatory state, and adipose tissue is being considered a major immunologically active endocrine organ (33, 34). We have also shown that Obadi cells can enhance the prometastatic EMT process in primary luminal cells in a leptin-dependent manner. In addition to leptin, the other inflammatory cytokines IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and IL-1β are also known to play major roles in promoting EMT and tumorigenesis, which strengthens the link between obesity, inflammation, and cancer development (26, 35).

The procarcinogenic effects of Obadi cells were also confirmed in orthotopic tumor xenografts, where they promoted tumor growth and the EMT process. Furthermore, we provide clear evidence that mammary epithelia from obese women undergo EMT-related changes relative to epithelia from lean females. Together, these findings provide the first direct proof that obesity activates breast adipocytes, which acquire protumorigenic potential. This connection between body adiposity and in-breast dysfunction could be due to the fact that the amount of fat in the breast is proportional to the total body fat mass (36), in addition to the well-known obesity-related systemic effects that may also affect the pathophysiology of the breast (37). In line with these findings, Strong et al. have recently shown that adipose stem cells isolated from obese patients can enhance the tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells and alter their gene expression profiles (38).

Additionally, we have used different molecular and cellular approaches to show that the tumor suppressor protein p16 plays key roles in suppressing the procarcinogenic effects of BSAd. First, we have shown for the first time that the p16 level is reduced in all Obadi cells as well as breast adipose tissues taken from obese women relative to levels in their respective control Leadi cells and tissues from lean women. Second, p16 knockdown in Leadi cells was sufficient to activate these adipocytes and enhance their proangiogenic effects as well as their tumorigenicity both in vitro and in vivo. Third, we have shown that p16 negatively regulates the expression/secretion of leptin, which is responsible for the paracrine procarcinogenic effects of p16-defective adipocytes.

We have also shown that p16 was downregulated in Obadi cells owing to higher turnover of the corresponding mRNA. This result raised an important question as to how obesity affects the expression of p16 in breast stromal adipocytes. Since obesity causes both in-breast and systemic inflammation (37), p16 downregulation in breast adipocytes could result from local and/or systemic obesity-dependent effects via inflammation/cancer-related cytokines. Indeed, the circulating levels of IL-6 and leptin, two major obesity- and cancer-related factors, were shown to be highly correlated with BMI in rodents and humans (39, 40). Thereby, IL-6 or leptin could be responsible for p16 downregulation in breast adipocytes in obese females. As a case in point, we have recently shown that paracrine IL-6 can downregulate p16 in breast stromal fibroblasts in a STAT3-dependent manner (41).

Importantly, specific p16 downregulation transformed Leadi cells to Obadi-like cells, with proinflammatory and -carcinogenic features. Indeed, like Obadi cells, p16-defective Leadi (Leadi-sh) cells expressed higher levels of NF-κB and its major inflammation-related target genes, including Cox-2, leptin, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-1β. This suggests that p16 also has anti-inflammatory functions in breast stromal adipocytes through repression of several inflammation-related genes, including leptin (42, 43). This corroborates previous findings which showed that p16 induction into the synovial tissues suppressed rheumatoid arthritis in animal models. Furthermore, p16 has anti-inflammatory functions in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts in vitro (44, 45). Moreover, we have recently shown that p16 represses the expression/secretion of IL-6 in breast stromal fibroblasts (10).

We have also shown that Leadi-sh cells became more migratory/invasive and proliferative and also triggered EMT in normal primary breast luminal cells in a paracrine manner. These procarcinogenic effects were confirmed in vivo in orthotopic tumor xenografts, wherein Leadi-sh cells promoted tumor growth and EMT compared to levels in control cells. These results clearly show the functional similarities between Leadi-sh and Obadi cells and the important role of p16 in their procarcinogenic effects both in vitro and in vivo. This also shows that p16 possesses a non-cell-autonomous tumor suppression function in BSAd. Furthermore, we present here the first indication that the procarcinogenic paracrine effects of p16-defective adipocytes are leptin dependent and that p16 negatively controls the expression/secretion of leptin through miR-141 and miR-146b-5p. In fact, there is high complementarity between mature miR-141/miR-146b-5p and the leptin 3′ UTR, which was responsive to both miRNAs. In line with these findings, we have shown the presence of an inverse correlation between the expression of p16/miR-141/miR-146b-5p and the level of their target leptin in various Obadi and Leadi cells. Intriguingly, Obadi cells express almost undetectable levels of miR-141 and miR-146b-5p, indicating that the level of these two tumor suppressor microRNAs is also affected by obesity in BSAd. miRNA profiling studies have identified several miRNAs which are differentially expressed in adipogenesis and associated with obesity in various adipose depots (46, 47). Furthermore, miR-141 was found downregulated in visceral adipose tissue of obese females (48), and miR-146b-5p was downregulated in monocytes during obesity (49). However, no study to date has analyzed the expression of these two microRNAs in BSAd.

The tumorigenicity of Obadi and Leadi-sh cells was further confirmed by evidence of their ability to enhance stemness both in vitro and in vivo. These cells promoted mammary stem cell features (expressing high levels of CD44 and low levels of CD24 [CD44high/CD24low] and ALDHhigh) in primary mammary luminal cells and in breast cancer cells in orthotopic tumor xenografts.

Together, the present results indicate that breast adipocytes from obese females are active procarcinogenic cells which express very low levels of the tumor suppressor protein p16, a negative regulator of leptin through miR-141 and miR-146b-5p. Therefore, the expression level of p16 and/or miR-141/miR-146b-5p in breast adipocytes could be utilized as a molecular biomarker for obesity and obesity-related procarcinogenic effects in the breast. This suggests that p16 and its downstream target tumor suppressor miRNAs could be exploited as predictive markers for breast cancer development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue collection.

Breast adipose tissues were collected from reduction mammoplasty according to the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center (KFSHRC; approval RAC 2140017). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Generation of primary differentiated adipocytes and luminal cells from breast tissues.

The obtained tissues were immediately digested with collagenase to separate preadipocytes from the stroma vascular fraction. Differentiated adipocytes were obtained as previously described (50). Preadipocytes were first cultured in special medium (preadipocyte growth medium [PAGM]) containing fetal calf serum (0.05 ml/ml), endothelial cell growth supplement (0.004 ml/ml), epidermal cell growth factor (10 ng/ml), hydrocortisone (1 μg/ml), and heparin (90 μg/ml) and used until confluence. Preadipocytes were then stimulated to differentiate by replacement of the preadipocyte medium with serum-free preadipocyte differentiation medium (SFPADM), supplemented with d-biotin (8 μg/ml), insulin (0.5 μg/ml), dexamethasone (400 ng/ml), 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX; 44 μg/ml), l-thyroxine (9 ng/ml), and ciglitazone (3 μg/ml). Differentiated adipocytes were then cultured using adipocyte nutrition medium (ANM) containing fetal calf serum (0.03 ml/ml), d-biotin (8 μg/ml), insulin (0.5 μg/ml), and dexamethasone (400 ng/ml). All supplements were purchased from PromoCell GmbH, Germany, and were utilized according to their instructions.

Normal breast luminal cells were obtained from the same tissues and were cultured as previously described (51).

Cell lines, cell culture, and chemicals.

MDA-MB-231 cells were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA) and cultured according to the instructions of the company. Mesenchymal stem cells (BM-04) were developed in the laboratory. Human superleptin antagonist (MBS400098) and IgG were purchased from MyBioSource. Blocking antibodies were used at 2.5 μg/ml. Recombinant human leptin protein (MBS197016) was purchased from MyBioSource and used at 45 ng/ml.

Cellular lysate preparation and immunoblotting.

Cellular lysate preparation and immunoblotting were performed as previously described (52). Antibodies directed against E-cadherin (HECD-1), N-cadherin, AKT (C73H10), P-AKT (Thr308), ERK (137F5), P-ERK (E10), EpCam (VU1D9), NF-κB(p65), STAT3, P-STAT3, and Snail (C15D3) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). GAPDH (FL-335) was from Santa Cruz (USA). p16 was from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Leptin, vimentin (RV202), Twist-1, IL-8, Fas, Ki-67, IL-1β, and IL-6 were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Zeb-1 (4C4) was from Abnova (Taipei, Taiwan). p53 (DO-1), ALDH1/2 (H-85), CD24 (C-20), and Cox2 (clone 29) were from Santa Cruz Biotech (Dallas, TX). CD44 was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and TNF-α (4H31) was from Novus Biologicals.

RNA purification and quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA containing miRNAs was purified using an miRNeasy minikit (Qiagen, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions and treated with RNase-free DNase. One microgram of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA utilizing either an Advantage RT-PCR kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA) or miScript II RT kit (Qiagen, United Kingdom) for mature miRNAs. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed in triplicate using 4 μl of cDNA mixed with 2× FastStart Essential DNA Green qPCR mastermix (Roche, New York, NY) and 0.3 μM forward and reverse primers. Amplifications were performed utilizing a LightCycler 96 real-time PCR detection system (Roche) using the following cycle conditions: 95°C for 10 min (1 cycle); 95°C for 10 s, 59°C for 20 s, and 72°C for 30 s (45 cycles). GAPDH expression levels were used for normalization, and gene expression differences were calculated using the threshold cycle (CT). The obtained values were plotted as means ± standard deviations (SD). Three independent experiments were performed for each reaction. Primer sequences are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequence of the primers utilized for qRT-PCR

| Target | Forward sequence | Reverse sequence |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | 5′-GAGTCCACTGGCGTCTTC-3′ | 5′-GGGGTGCTAAGCAGTTGGT-3′ |

| CDKN2A | 5′-CAACGCACCGAATAGTTACG-3′ | 5′-CAGCTCCTCAGCCAGGTC-3′ |

| LEP | 5′-TTTGGCCCTATCTTTTCTATGTCC-3′ | 5′-TGGAGGAGACTGACTGCGTG-3′ |

| CXCL8 (IL-8) | 5′-GATCCACAAGTCCTTGTTCCA-3′ | 5′-GCTTCCACATGTCCTCACAA-3′ |

| CD82 | 5′-TGGGCTCAGCCTGTATCAAAGTCA-3′ | 5′-AGATGAAACTGCTCTTGTCGGCCA-3′ |

| BCL2 | 5′-TTTCTCATGGCTGTCCTTCAGGGT-3′ | 5′-AGGTCTGGCTTCATACCACAGGTT-3′ |

| CYCLINA2 | 5′-ATGAGCATGTCACCGTTCCTCCTT-3′ | 5′-TCAGCTGGCTTCTTCTGAGCTTCT-3′ |

| CDK2 | 5′-AGATGGACGGAGCTTGTTGTTATCGCA-3′ | 5′-TGGCTTGGTCACATCCTGGAAGAA-3′ |

| CTGF | 5′-TCAAGACCTGTGCCTGCCATTACA-3′ | 5′-ACTCTCTGGCTTCATGCCATGTCT-3′ |

| GLUT4 | 5′-CTGTAACTTCATTGTCGGCATGG-3′ | 5′-AGGCAGCTGAGATCTGGTCAAAC-3′ |

| TNF-α | 5′-CCCAGGGACCTCTCTCTAATC-3′ | 5′-ATGGGCTACAGGCTTGTCACT-3′ |

| FABP4 | 5′-ACGAGAGGATGATAAACTGGTGG-3′ | 5′-GCGAACTTCAGTCCAGGTCAAC-3′ |

| CDH1 (E-cadherin) | 5′-CCAGAAACGGAGGCCTGAT-3′ | 5′-CTGGGACTCCACCTACAGAAAGTT-3′ |

| CDH2 (N-cadherin) | 5′-CCTCCAGAGTTTACTGCCATGAC-3′ | 5′-GTAGGATCTCCGCCACTGATTC-3′ |

| VIM (vimentin) | 5′-TTCCAAACTTTTCCTCCCTGAACC-3′ | 5′-TCAAGGTCATCGTGATGCTGAG-3′ |

| ZEB1 | 5′-GGCAGAGAATGAGGGAGAAG-3′ | 5′-CTTCAGACACTTGCTCACTACTC-3′ |

| TWIST1 | 5′-GGACAAGCTGAGCAAGATTCAGA-3′ | 5′-GTGAGCCACATAGCTGCAG-3′ |

| Snail | 5′-CCTCAAGATGCACATCCGAAG-3′ | 5′-ACATGGCCTTGTAGCAGCCA-3′ |

| Mature miR-141 | UAACACUGUCUGGUAAAGAUGG | |

| Mature miR-146b-5p | UGAGAACUGAAUUCCAUAGGCU |

Transfection/viral infection.

pLKO1-CDKN2A-shRNA (specific downregulation of p16) (Addgene), pLKO.1-miRZip146b-5p (inhibitor of miR-146b-5p), pLKO.1-miRZip141 (inhibitor of miR-141), pCDH-miR-141 (expressing pre-miR-141), pCDH-miR-146b-5p (expressing pre-miR-146b-5p) (all from System Biosciences), pGFP-C-LEPshLenti plasmid (specific downregulation of leptin), and their control plasmids were used at 1 μg/ml each for transfection of 293FT cells. Lentiviral supernatants were collected at 48 h posttransfection. Culture medium was removed from the target cells and replaced with the lentiviral supernatant and incubated for 24 h in the presence of 1 μg/ml Polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). Transduced cells were selected after 48 h with puromycin.

Analysis of mRNA stability.

Exponentially growing cells were challenged with actinomycin D (5 μg/ml) for various periods of time (0 to 6 h); then total RNA was purified, and the level of the CDKN2A mRNA was assessed using qRT-PCR. Nonlinear regression analysis (Prism; GraphPad Software) was used to assess mRNA decay kinetics, considering the values at time zero as 100%. The time corresponding to 50% remaining mRNA was considered the mRNA half-life.

miRNA target prediction.

miRNA targets were predicted using algorithms, including miRanda human miRNA targets, miRDB, RNA22, and miROrg. To identify the genes commonly predicted by these different algorithms, the results of predicted targets were intersected using miRWalk.

Dual-luciferase reporter assay.

Cells were plated at 1 × 105 cells/well on six-well plates and transfected with 3 μg of the luciferase/Renilla reporter vector containing either human wild-type LEP 3′ UTR (871 bp) sequence, mutated sequence of the miR-141 or miR-146b-5p seed sequence, or a control sequence with no AU-rich conserved elements (GeneCopoeia). Transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 2000, as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). At 24 h posttransfection, cells were seeded in a 96-well plate, and firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were consecutively measured using a dual-luciferase assay as recommended by the manufacturer (GeneCopoeia). The firefly luciferase signal was normalized to that of the Renilla luciferase signal for each individual analysis. The mean and standard error (SE) were calculated from three wells for each 3′ UTR activity, and results are presented as fold change over the level of the nonstimulated control.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and quenched in 100 mM glycine for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were then blocked in 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and incubated with primary antibody, washed, and incubated with the Alexa Fluor 594- or 488-conjugated antibody (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). Nuclei were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories, Inc.), and images were captured using a FLoid Cell Imaging Station (Life technologies). Antibodies against leptin, perilipin A, Glut-4, and Ki-67 were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA); FABP-4 was from Life Span Biosciences (Seattle, WA), TNF-α was from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO), and fatty acid synthase (C20G5), adiponectin, PPAR-γ (C26H12), and E-cadherin (HECD-1) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). The percentage of Ki-67-labeled cells (labeling index [LI]) was determined for at least 500 cells per data point and is expressed as the mean and standard error of triplicate determinations.

Oil Red O staining.

Cells were subjected to cytospins, fixed with 10% formalin for 1 h at room temperature (RT), and washed with distilled H2O and then with 60% isopropanol for 5 min. Cells were then stained with 0.3% Oil Red O solution in isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 5 min at RT, washed, and counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Immunohistochemistry.

Formalin-fixed/paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues were utilized for immunohistochemistry as previously described (54). Tissues were incubated overnight with anti-Ki-67, anti-p16 (EPR1473), or antileptin (Abcam), anti-EpCam (D13B) (Cell Signaling), or antivimentin (Abcam) antibody at a dilution of 1:500, followed by either peroxidase-conjugated (Dako) or Alexa Fluor-conjugated antibodies. Sites of antibody binding were visualized by the deposition of the brown polymer of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine chromogen (DAB; Novocastra Laboratories, Ltd., Buffalo Grove, IL).

Cell migration, invasion, and proliferation.

Cell migration, invasion, and proliferation assays were performed in label-free real-time settings using xCELLigence real-time cell analysis (RTCA) technology (Roche, Germany) that measures impedance changes in a meshwork of interdigitated gold microelectrodes located at the well bottom (E-plate) or at the bottom side of a microporous membrane (CIM plate 16) (55, 56). Cell migration and invasion were assessed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, 2 × 104 cells in serum-free medium were added to the upper wells of the CIM plate either uncoated (migration) or coated with a thin layer of Matrigel (BD Biosciences) basement membrane matrix diluted 1:20 in serum-free medium (invasion). Complete medium was used as a chemoattractant in the lower chambers. Subsequently, the plates were incubated in the RTCA plate for 24 h, and the impedance value of each well was automatically monitored by the xCELLigence system and expressed as the cell index (CI) value, which represents cell status based on the measured electrical impedance change divided by a background value. Each assay was performed in triplicate.

For the proliferation assay, exponentially growing cells (2 × 104) were seeded in an E-plate with complete medium in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Cell proliferation was assessed for 48 h. All data were recorded and analyzed by the RTCA software. The cell index was used to measure the change in the electrical impedance divided by background value, which represents cell status. Each assay was biologically performed in triplicate (53).

Conditioned medium.

Cells were cultured in serum-free medium (SFM) for 48 h, and then the medium was collected and centrifuged. Conditioned medium (CM) was used either immediately or frozen at −80°C until needed.

Adipokine array.

Serum-free conditioned medium was applied on an adipokine antibody array membrane (AAH-ADI-1; RayBiotech, Inc., Norcross, GA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the membranes were incubated with 1 ml of SFCM overnight and then washed and reincubated with biotin-conjugated anticytokines. Subsequently, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin secondary antibodies and visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system. Membranes were then imaged by charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera (ImageQuant LAS 4000; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA).

ELISA.

ELISAs were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. IL-6 and VEGF-A were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and leptin, IL-8, and IL-1β were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The optical density (OD) at 450 nm on a standard ELISA plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used. These experiments were performed in triplicate.

Tumor xenografts.

Animal experiments were approved by the KFSHRC institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) and were conducted according to relevant national and international guidelines. SCID mice were randomized into three groups, and breast cancer xenografts were created by coimplantation of the MDA-MB-231 cells (2 × 106) with adipocytes (4 × 106) under the nipple in the mammary fat pad. As controls, 2 × 106 MDA-MB-231 cells were injected separately. The growth of the tumors was then monitored weekly. Tumor size was measured with a caliper using the following formula: length × width × height. Six weeks after the injections the animals were scarified, and tumors were excised and weighed.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad software. The results are presented as means ± SD or standard errors of the means (SEM) of at least three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) as well as a two-tailed Student t test, and P values of 0.05 and less were considered statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Ibrahim S. Al-Mssallem for his great support and the initiation of this project. We are thankful to the Research Center administration for their continuous help and support.

This work was performed under RAC proposal 2140017 and was supported in part by a KACST grant under the National Comprehensive Plan for Science and Technology, KACST 14-BIO159-20.

REFERENCES

- 1.Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. 2016. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends—an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 25:16–27. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. 2015. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yung RL, Ligibel JA. 2016. Obesity and breast cancer: risk, outcomes, and future considerations. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol 14:790–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hefetz-Sela S, Scherer PE. 2013. Adipocytes: impact on tumor growth and potential sites for therapeutic intervention. Pharmacol Ther 138:197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ando S, Barone I, Giordano C, Bonofiglio D, Catalano S. 2014. The multifaceted mechanism of leptin signaling within tumor microenvironment in driving breast cancer growth and progression. Front Oncol 4:340. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ando S, Catalano S. 2011. The multifactorial role of leptin in driving the breast cancer microenvironment. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8:263–275. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saxena NK, Sharma D. 2013. Multifaceted leptin network: the molecular connection between obesity and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 18:309–320. doi: 10.1007/s10911-013-9308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cirillo D, Rachiglio AM, la Montagna R, Giordano A, Normanno N. 2008. Leptin signaling in breast cancer: an overview. J Cell Biochem 105:956–964. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman G, Gonzalez-Perez RR. 2014. Leptin-cytokine crosstalk in breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 382:570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Ansari MM, Hendrayani SF, Shehata AI, Aboussekhra A. 2013. p16(INK4A) represses the paracrine tumor-promoting effects of breast stromal fibroblasts. Oncogene 32:2356–2364. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh J, Enders GH, Dynlacht BD, Harlow E. 1995. Tumour-derived p16 alleles encoding proteins defective in cell-cycle inhibition. Nature 375:506–510. doi: 10.1038/375506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherr CJ. 2001. The INK4a/ARF network in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2:731–737. doi: 10.1038/35096061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharpless NE, Bardeesy N, Lee KH, Carrasco D, Castrillon DH, Aguirre AJ, Wu EA, Horner JW, DePinho RA. 2001. Loss of p16Ink4a with retention of p19Arf predisposes mice to tumorigenesis. Nature 413:86–91. doi: 10.1038/35092592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaPak KM, Burd CE. 2014. The molecular balancing act of p16INK4a in cancer and aging. Mol Cancer Res 12:167–183. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rocco JW, Sidransky D. 2001. p16(MTS-1/CDKN2/INK4a) in cancer progression. Exp Cell Res 264:42–55. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine AJ. 1997. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell 88:323–331. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Khalaf HH, Mohideen P, Nallar SC, Kalvakolanu DV, Aboussekhra A. 2013. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a physically interacts with transcription factor Sp1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 4 to transactivate microRNA-141 and microRNA-146b-5p spontaneously and in response to ultraviolet light-induced DNA damage. J Biol Chem 288:35511–35525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun P, Nallar SC, Raha A, Kalakonda S, Velalar CN, Reddy SP, Kalvakolanu DV. 2010. GRIM-19 and p16INK4a synergistically regulate cell cycle progression and E2F1-responsive gene expression. J Biol Chem 285:27545–27552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.105767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Khalaf HH, Aboussekhra A. 2014. MicroRNA-141 and microRNA-146b-5p inhibit the prometastatic mesenchymal characteristics through the RNA-binding protein AUF1 targeting the transcription factor ZEB1 and the protein kinase AKT. J Biol Chem 289:31433–31447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.593004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Khalaf HH, Colak D, Al-Saif M, Al-Bakheet A, Hendrayani SF, Al-Yousef N, Kaya N, Khabar KS, Aboussekhra A. 2011. p16INK4a positively regulates cyclin D1 and E2F1 through negative control of AUF1. PLoS One 6:e21111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burk U, Schubert J, Wellner U, Schmalhofer O, Vincan E, Spaderna S, Brabletz T. 2008. A reciprocal repression between ZEB1 and members of the miR-200 family promotes EMT and invasion in cancer cells. EMBO Rep 9:582–589. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, Barry SC, Tsykin A, Farshid G, Vadas MA, Khew-Goodall Y, Goodall GJ. 2008. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol 10:593–601. doi: 10.1038/ncb1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, Campbell LL, Polyak K, Brisken C, Yang J, Weinberg RA. 2008. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Renehan AG, Zwahlen M, Egger M. 2015. Adiposity and cancer risk: new mechanistic insights from epidemiology. Nat Rev Cancer 15:484–498. doi: 10.1038/nrc3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buettner C, Pocai A, Muse ED, Etgen AM, Myers MG Jr, Rossetti L. 2006. Critical role of STAT3 in leptin's metabolic actions. Cell Metab 4:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crespi E, Bottai G, Santarpia L. 2016. Role of inflammation in obesity-related breast cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol 31:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Divella R, De Luca R, Abbate I, Naglieri E, Daniele A. 2016. Obesity and cancer: the role of adipose tissue and adipo-cytokines-induced chronic inflammation. J Cancer 7:2346–2359. doi: 10.7150/jca.16884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Matteis R, Zingaretti MC, Murano I, Vitali A, Frontini A, Giannulis I, Barbatelli G, Marcucci F, Bordicchia M, Sarzani R, Raviola E, Cinti S. 2009. In vivo physiological transdifferentiation of adult adipose cells. Stem Cells 27:2761–2768. doi: 10.1002/stem.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenwald M, Perdikari A, Rulicke T, Wolfrum C. 2013. Bi-directional interconversion of brite and white adipocytes. Nat Cell Biol 15:659–667. doi: 10.1038/ncb2740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stienstra R, van Diepen JA, Tack CJ, Zaki MH, van de Veerdonk FL, Perera D, Neale GA, Hooiveld GJ, Hijmans A, Vroegrijk I, van den Berg S, Romijn J, Rensen PC, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Kanneganti TD. 2011. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100255108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr. 2003. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI200319246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng T, Lyon CJ, Bergin S, Caligiuri MA, Hsueh WA. 2016. Obesity, inflammation, and cancer. Annu Rev Pathol 11:421–449. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012615-044359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dixit VD. 2008. Adipose-immune interactions during obesity and caloric restriction: reciprocal mechanisms regulating immunity and health span. J Leukoc Biol 84:882–892. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0108028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grant RW, Dixit VD. 2015. Adipose tissue as an immunological organ. Obesity 23:512–518. doi: 10.1002/oby.21003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou C, Liu J, Tang Y, Liang X. 2012. Inflammation linking EMT and cancer stem cells. Oral Oncol 48:1068–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schautz B, Later W, Heller M, Muller MJ, Bosy-Westphal A. 2011. Associations between breast adipose tissue, body fat distribution and cardiometabolic risk in women: cross-sectional data and weight-loss intervention. Eur J Clin Nutr 65:784–790. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iyengar NM, Hudis CA, Dannenberg AJ. 2015. Obesity and cancer: local and systemic mechanisms. Annu Rev Med 66:297–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050913-022228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strong AL, Ohlstein JF, Biagas BA, Rhodes LV, Pei DT, Tucker HA, Llamas C, Bowles AC, Dutreil MF, Zhang S, Gimble JM, Burow ME, Bunnell BA. 2015. Leptin produced by obese adipose stromal/stem cells enhances proliferation and metastasis of estrogen receptor positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res 17:112. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0622-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, Ranganathan G. 2001. Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280:E745–E751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maffei M, Halaas J, Ravussin E, Pratley RE, Lee GH, Zhang Y, Fei H, Kim S, Lallone R, Ranganathan S, Kern PA, Friedman JM. 1995. Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight-reduced subjects. Nat Med 1:1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hendrayani SF, Al-Khalaf HH, Aboussekhra A. 2014. The cytokine IL-6 reactivates breast stromal fibroblasts through transcription factor STAT3-dependent up-regulation of the RNA-binding protein AUF1. J Biol Chem 289:30962–30976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.594044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iikuni N, Lam QL, Lu L, Matarese G, La Cava A. 2008. Leptin and Inflammation. Curr Immunol Rev 4:70–79. doi: 10.2174/157339508784325046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandez-Riejos P, Najib S, Santos-Alvarez J, Martin-Romero C, Perez-Perez A, Gonzalez-Yanes C, Sanchez-Margalet V. 2010. Role of leptin in the activation of immune cells. Mediators Inflamm 2010:568343. doi: 10.1155/2010/568343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taniguchi K, Kohsaka H, Inoue N, Terada Y, Ito H, Hirokawa K, Miyasaka N. 1999. Induction of the p16INK4a senescence gene as a new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med 5:760–767. doi: 10.1038/10480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nasu K, Kohsaka H, Nonomura Y, Terada Y, Ito H, Hirokawa K, Miyasaka N. 2000. Adenoviral transfer of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor genes suppresses collagen-induced arthritis in mice. J Immunol 165:7246–7252. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGregor RA, Choi MS. 2011. microRNAs in the regulation of adipogenesis and obesity. Curr Mol Med 11:304–316. doi: 10.2174/156652411795677990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ortega FJ, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Pardo G, Sabater M, Hummel M, Ferrer A, Rodriguez-Hermosa JI, Ruiz B, Ricart W, Peral B, Fernandez-Real JM. 2010. MiRNA expression profile of human subcutaneous adipose and during adipocyte differentiation. PLoS One 5:e9022. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Capobianco V, Nardelli C, Ferrigno M, Iaffaldano L, Pilone V, Forestieri P, Zambrano N, Sacchetti L. 2012. miRNA and protein expression profiles of visceral adipose tissue reveal miR-141/YWHAG and miR-520e/RAB11A as two potential miRNA/protein target pairs associated with severe obesity. J Proteome Res 11:3358–3369. doi: 10.1021/pr300152z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hulsmans M, Van Dooren E, Mathieu C, Holvoet P. 2012. Decrease of miR-146b-5p in monocytes during obesity is associated with loss of the anti-inflammatory but not insulin signaling action of adiponectin. PLoS One 7:e32794. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernyhough ME, Vierck JL, Hausman GJ, Mir PS, Okine EK, Dodson MV. 2004. Primary adipocyte culture: adipocyte purification methods may lead to a new understanding of adipose tissue growth and development. Cytotechnology 46:163–172. doi: 10.1007/s10616-005-2602-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ghebeh H, Sleiman GM, Manogaran PS, Al-Mazrou A, Barhoush E, Al-Mohanna FH, Tulbah A, Al-Faqeeh K, Adra CN. 2013. Profiling of normal and malignant breast tissue show CD44high/CD24low phenotype as a predominant stem/progenitor marker when used in combination with Ep-CAM/CD49f markers. BMC Cancer 13:289. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Al-Mohanna MA, Al-Khalaf HH, Al-Yousef N, Aboussekhra A. 2007. The p16INK4a tumor suppressor controls p21WAF1 induction in response to ultraviolet light. Nucleic Acids Res 35:223–233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams CJ, Pike AC, Maniam S, Sharpe TD, Coutts AS, Knapp S, La Thangue NB, Bullock AN. 2012. The p53 cofactor Strap exhibits an unexpected TPR motif and oligonucleotide-binding (OB)-fold structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:3778–3783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113731109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ghebeh H, Barhoush E, Tulbah A, Elkum N, Al-Tweigeri T, Dermime S. 2008. FOXP3+ Tregs and B7-H1+/PD-1+ T lymphocytes co-infiltrate the tumor tissues of high-risk breast cancer patients: implication for immunotherapy. BMC Cancer 8:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knopfova L, Benes P, Pekarcikova L, Hermanova M, Masarik M, Pernicova Z, Soucek K, Smarda J. 2012. c-Myb regulates matrix metalloproteinases 1/9, and cathepsin D: implications for matrix-dependent breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Mol Cancer 11:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-11-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jurmeister S, Baumann M, Balwierz A, Keklikoglou I, Ward A, Uhlmann S, Zhang JD, Wiemann S, Sahin O. 2012. MicroRNA-200c represses migration and invasion of breast cancer cells by targeting actin-regulatory proteins FHOD1 and PPM1F. Mol Cell Biol 32:633–651. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06212-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]