Abstract

The genomic program for development operates primarily by the regulated expression of genes encoding transcription factors and components of cell signaling pathways. This program is executed by cis-regulatory DNAs (e.g., enhancers and silencers) that control gene expression. The regulatory inputs and functional outputs of developmental control genes constitute network-like architectures. In this PNAS Special Feature are assembled papers on developmental gene regulatory networks governing the formation of various tissues and organs in nematodes, flies, sea urchins, frogs, and mammals. Here, we survey salient points of these networks, by using as reference those governing specification of the endomesoderm in sea urchin embryos and dorsal–ventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo.

Development of animal body plans proceeds by the progressive installation of transcriptional regulatory states, transiently positioned in embryonic space. The underlying mechanism is the localized expression of genes encoding sequence-specific transcription factors at specific times and places. The units of control are clusters of DNA sequence elements that serve as target sites for transcription factors, which usually correspond to enhancers, although there are other kinds of cis-regulatory DNA modules as well, such as silencers and insulators. We refer to all of these regulatory DNAs as “cis-regulatory modules.” Each module is typically 300 bp or more in length and contains on the order of 10 or more binding sites for at least four transcription factors (1, 2). In general, a particular cis-regulatory module produces a specific pattern of gene expression in space or time, and multiple modules can produce complex patterns of gene expression (3). Because each module is regulated by multiple transcription factors and each transcription factor interacts with multiple modules, it is possible to represent developmental patterns of gene expression as an interlocking network (for reviews and discussion, see refs. 2 and 4–7).

Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) are logic maps that state in detail the inputs into each cis-regulatory module, so that one can see how a given gene is fired off at a given time and place. They also provide specifically testable sets of predictions of just what target sites are hardwired into the cis-regulatory DNA sequence. The specific linkages constituting these networks provide a causal structure/function answer to the question of how any given aspect of development is ultimately controlled by heritable genomic sequence information. The architecture reveals features that can never be appreciated at any other level of analysis but that turn out to embody distinguishing and deeply significant properties of each control system. These properties are composed of linkages of multiple genes that together perform specific operations, such as positive feedback loops, which drive stable circuits of cell differentiation (4, 7, 8).

Comparison of Diverse Developmental Systems

This Special Feature contains works that consider different aspects of GRNs in a variety of systems. The dorsal–ventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo is controlled by the graded distribution of a maternal transcription factor, Dorsal (reviewed in ref. 9). As we discuss below, this gradient initiates a GRN that governs the differentiation of the mesoderm, neurogenic ectoderm, and dorsal ectoderm during gastrulation. A work by Ochoa-Espinosa et al. (8) in this issue of PNAS describes the network underlying segmentation of the Drosophila embryo. There are parallels between segmentation and dorsal–ventral patterning. Both networks begin to function while the embryo is still a syncytium, so intercellular signaling plays only a limited role in the initial spatial interactions. Characteristic of these networks are dynamic and transient patterns of gene expression in which changes of regulatory state and boundaries of expression patterns are governed by multiple tiers of transcriptional repression.

Two other developmental specification systems that are considered in this collection of works rely on the early use of intercellular signals: the sea urchin embryonic endomesoderm, briefly discussed below, and the dorsal axial structures of the Xenopus embryo, which is discussed by Koide et al. in ref. 10. In both networks, specific regulatory states are placed in the proper spatial domains of the embryo in response to localized intercellular signals. Signal transduction and feedback “lockdown” loops are seen in both networks (4, 7, 10), although, at the level of morphological phenomenology, Xenopus and sea urchin embryos would appear to develop rather differently. Postembryonic GRNs are the subjects of two other works in this Special Feature. Singh and Medina (11) present an analysis of mammalian B cell differentiation, and Inoue et al. (12) focus on vulval cell specification in larval Caenorhabditis elegans. Both networks are bolstered by direct cis-regulatory analysis. This Special Feature is, to our knowledge, the first time a collection of GRNs has been presented in a manner that permits direct comparisons, as we discuss below.

Two other selections in the Special Feature (13, 14) are focused on the genomic design of cis-regulatory modules such as those that compose the GRNs considered in this collection. In the first, Papatsenko and M.L. (13) demonstrate a statistical correlation between different classes of target sites and distinct transcriptional responses to higher as opposed to lower levels of the Dorsal regulator in Drosophila embryos. They also show how differences in the organization of binding sites can produce distinct patterns of gene expression. In the second of these works, Istrail and E.H.D. (14) make an initial effort to “parse” cis-regulatory modules into combinations drawn from a small repertoire of continuous and discrete logic functions using both Drosophila and sea urchin cases.

We turn now to our specific examples, the GRNs underlying specification of endomesoderm in the sea urchin embryo and dorsal–ventral patterning in Drosophila. Both of these networks have been derived from, and are supported by, large-scale experimental efforts.

Specification of Endomesoderm in the Strongylocentrotus purpuratus Embryo

The sea urchin embryo is simply constructed compared with the Drosophila embryo, because its role is to build only a microscopic swimming larva composed mainly of single layers of differentiated cells, rather than a multilayered, metameric, juvenile form of the adult body plan. In most sea urchins, the much more complex adult body plan is constructed only later, after the larva begins to feed. Consequently, the process of embryogenesis in these sea urchins is one in which the underlying GRN is organized to install differentiated cells in the right places in the embryo as directly as possible. Development begins with a stereotyped cleavage pattern. In response to intercellular signaling, between the 16- and ≈128-cell stages, the lineages that will give rise to the gut of the larva, its biomineral skeleton, and a set of other distinct mesodermal cell types have largely been separated out from the lineages that will form the ectodermal wall of the larva. The endoderm, skeletal, and other mesodermal components (here endomesoderm) establish definitive regulatory states during this period and then proceed to delineate further spatial subdivisions. Within these, by 1 day after fertilization, differentiation gene batteries have begun to be expressed (for review, see ref. 15). The morphogenetic movements of gastrulation follow these embryo-wide events of territorial and cell fate specification, which include regional activation of genes required for cell motility and other gastrular functions. The network shown in Fig. 1 represents the genomic regulatory code that controls the entire endomesodermal specification process up to 24–30 h, from the initial interpretation early in development of maternal asymmetries inherited from the egg cytoarchitechture to the activation of differentiation genes.

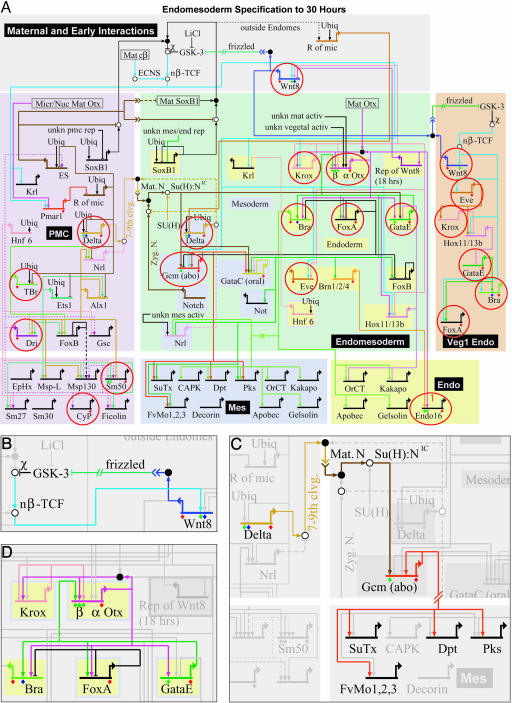

Fig. 1.

GRN for endomesoderm specification in sea urchin embryos. (A) GRN for period from initiation of zygotic regulatory control shortly after fertilization to just before gastrulation (≈4–30 h). The short horizontal lines represent relevant cis-regulatory modules of indicated genes on which the color-coded inputs impinge. The sources of these inputs are other genes of the GRN, as indicated by the thin colored lines. Small open and filled circles represent protein–protein interactions that occur off the DNA and are not included explicitly in the GRN, the objective of which is to display the predicted genomic regulatory organization responsible for spatial and temporal expression of the genes it includes. For symbolism, explanations, and access to the biotapestry software by which the GRN is built and maintained, see http://sugp.caltech.edu/endomes/webStart/bioTapestry.jnlp, where the current version of GRN is posted or contact E.H.D. The red circles indicate genes for which genomic cis-regulatory modules have been isolated and shown to generate the relevant spatial and temporal patterns of gene expression of the endogenous genes. (B) The cis-regulatory programming of the wnt8 loop, from ref. 24. Experiments demonstrate that the cis-regulatory system includes Tcf sites that are required to maintain expression and that respond to the β-catenin–Tcf input (nβ-TCF); as is well known, reception of the Wnt8 signal ligand causes intracellular formation of nuclear β-catenin–Tcf complex in the recipient cells. Thus, the endomesodermal cells are engaged in a self-stimulating, positive reinforcement of expression of Tcf-responsive genes (see A). (C) The cis-regulatory programming responsible for reception by adjacent presumptive mesodermal cells of a Delta signal emitted by skeletogenic cells and for activation of pigment cell differentiation genes (29); these are SuTx (Sulfotransferase), Dpt (Dopachrome tautomerase), Pks (Polyketide synthetase), and FvMo (Flavine-containing monoxigenase). The Delta signal is received by a Notch receptor that together with a Supressor of Hairless [Su(H)] transcription factor already present in these cells transmits a permissive input to the cis-regulatory module of the gcm regulatory gene. These relationships were established experimentally in gene transfer studies by using a mutant Su(H) factor and by mutational analysis of the gcm cis-regulatory module (A. Ransick and E.H.D., unpublished data). After activation, gcm locks itself on by autoregulation. (D) Endoderm specification feedback loop. As discussed in the text and in more detail elsewhere (4, 19, 56), this “kernel” of the GRN is conserved without significant change in starfish, a very distantly related echinoderm. It has the functions of initially activating regulatory genes in the presumptive endoderm as a function of krox and β-otx activation; thereby activating a pleiotropic endoderm regulator, gatae, then locking in gatae expression by establishment of feedback to a β-otx cis-regulatory module, and stably activating the gut regulatory genes foxa and brachury.

The network consists of almost 50 genes. The large pastel areas in Fig. 1 symbolize the regulatory states of the skleletogenic (lavender) and mesoderm/endoderm (green) spatial domains, wherein genes that contribute to mesodermal specification in particular are shown on blue backgrounds and genes that execute endoderm specification are shown on yellow backgrounds. The tan area on the right represents a late-specified endodermal region that invaginates at the end of gastrulation and produces posterior portions of the gut. In all these areas, most of the named genes encode transcription factors; the remainder are differentially expressed signaling components. At the bottom of the diagram, the smaller rectangles enclose samples of the respective sets of differentiation genes, i.e., genes that encode skelotogenic, mesodermal (mainly pigment cell), and gut effector proteins. The network image shows the transcription factor inputs (vertical arrows and barred lines) that impinge on the relevant cis-regulatory modules, which are symbolized by the short horizontal lines overlying the names of the respective genes. From each gene the color-coded thin lines display the outputs to other genes in the network (the mode of presentation and its significance are discussed in refs. 4–7 and 16; for updates, contact E.H.D. or see the web site http://sugp.caltech.edu/endomes/webStart/bioTapestry.jnlp, where much of the underlying experimental data also are posted). Evidence on which the network is based includes the temporal expression of all of the genes in the network (obtained by quantitative PCR); spatial expression of these genes (obtained by whole-mount in situ hybridization); and the results of a large-scale perturbation analysis, in which expression of each gene was taken out of the system (usually by use of antisense morpholino-substituted oligonucleotides), and the effects on all other relevant genes were measured by quantitative PCR. However, for other essential supporting information, where the causal evidence is too unique to be easily tabularized, specific publications must be consulted (also listed on the web site). For example, such evidence includes the effects of ectopic expression of given regulatory genes on spatial specification events (e.g., refs. 17 and 18).

Authentication and Completeness. Completeness is the fraction of regulatory genes actually involved in the process that is included explicitly in the network as shown. Completeness can be addressed only with the aid of genomic sequence information, which provides the possibility of computational screens and the possibility of reference to the complete regulatory gene repertoire. Authenticity is the level at which the interactions pictured in the network have been demonstrated to represent cis-regulatory transactions encoded in the genomic sequence. We argue that there is only one way to authenticate a GRN, and that is by means of direct experimental manipulation of individual cis-regulatory modules. Much of the architecture of the sea urchin network in Fig. 1 is based directly on cis-regulatory experimentation, and the same is to a large extent true of all of the GRNs included in this Special Feature. Thus, with respect to authentication, these networks are among the standards in this young field.

With regard to the GRN in Fig. 1, the issue of completeness is not yet fully addressed. However, because the genome sequence of Strongylocentrotus purpuratus is now becoming available (obtained by the Human Genome Sequence Center of Baylor University; National Center for Biotechnology Information Trace Repository), we have been able to determine the temporal and spatial expression of hundreds of predicted regulatory genes. It has turned out that the number of new genes that are specifically expressed in early endomesodermal domains of the embryo can be counted on the fingers of one hand for each territory. Thus, indications are that the current version of the network is not very incomplete, although we are aware of several places where linkages and gene targets are missing and of several spatial patterns of expression that are not yet completely explained. A large-scale effort has been mounted with respect to authentication of the endomesoderm network, as indicated by the thin red circles in Fig. 1. For every one of the circled genes, a small (several hundred base pairs) DNA fragment has been recovered that, when associated with a reporter gene and introduced into sea urchin eggs, reproduces the developmental pattern of expression of the endogenous gene. The circled genes include most of the key nodes of the network. Just the fact that all of the predicted cis-regulatory modules in the circles have been experimentally demonstrated to exist provides the basic level of authentication: the GRN indeed represents a genomic regulatory system, in which the DNA sequence elements contain the causal basis for the gene expression patterns that drive the developmental process. The next level of analysis is to determine whether each cis-regulatory module responds in the same way as the associated gene in the living embryo when challenged by experimental perturbations. The final level is to show by mutation that the module contains the target site(s) for the inputs predicted in the network (or, if not, to correct the network architecture). Different cis-regulatory modules circled in Fig. 1 are at different stages of experimental manipulation (see legend). But for some modules, the analysis is complete, e.g., the β-otx module (19), for which all of the predicted inputs were demonstrated by both perturbation and cis-regulatory mutation. Where the evidence is in, the predictions of the network shown in Fig. 1 have been substantiated at the cis-regulatory level.

GRN and How to Understand Development. There are three ways in which the GRN provides a qualitatively different and innovative kind of understanding not otherwise accessible. First, it explains, in the causal terms of the explicit genomic regulatory code, much of the phenomenology of early embryogenesis discovered in the course of years of painstaking experimental embryology. Take, for example, the essential role of maternal β-catenin nuclearization. The work of McClay and others (20–23) has shown that nuclearization of this transcriptional cofactor is necessary to specify the future endomesoderm and that subsequent expression of the wnt8 gene in these same cells both requires the initial β-catenin nuclearization and is in turn required for endomesoderm development. A glance at the network tells us why this is, what functions are executed, and how these functions are programmed in the relevant genomic cis-regulatory modules. The β-catenin/Tcf transcriptional input is required for several genes that function early on in different regions of the endomesoderm, as shown by the thin blue lines emanating from the “nβ-Tcf” symbol (i.e., nuclearized β-catenin-Tcf transcription factor) at the upper left of Fig. 1 A. The cis-regulatory module driving the wnt8 gene itself is among these target genes (24). This relationship sets up a positive loop, because the Wnt8 gene product acts as an intercellular ligand that in recipient cells results in further β-catenin nuclearization (Fig. 1B). Another prominent signaling phenomenon in this embryo is the dependence of mesodermal specification on a Delta/Notch interaction between the skeletogenic cells and the adjacent endomesodermal precursors (25–27). The explanation, in terms of the genomic regulatory code, is that the relevant delta cis-regulatory module (28) is controlled by the skeletogenic lineage regulatory system, which prevents expression of its participant genes (i.e., including delta) anywhere except in this domain (5, 7, 16, 17). Thereby we can account for the localization of the Delta signal. The network shows, furthermore, that in the recipient cells, the Notch receptor transcriptional complex directly activates a regulatory gene (gcm) that in turn locks itself stably on (A. Ransick and E.H.D., unpublished data), and gcm also provides positive regulatory input into downstream genes that encode pigment cell differentiation proteins (Fig. 1C; see also ref. 29). Throughout the network, the input/output regulatory relationships explain what happens in terms of the cis-regulatory DNA sequence code. Thereby the network at last closes the conceptual and evidential gap between the static genomic program for development and the dynamic progression of spatial regulatory states.

The second way in which the GRN provides a different kind of insight is in respect to its own modular structure. It is composed of multigenic assemblages of components that work together to accomplish given regulatory tasks, of which Fig. 1 B and C provide specific examples. A particularly interesting example is shown in Fig. 1D, which portrays a feedback loop that undoubtedly constitutes the driving regulatory input that initiates, and then stabilizes and promotes, the state of endoderm specification (4). We refer to a subcircuit such as this one, which performs a dedicated and specific role, as a “kernel” of the network. After early inputs activate the endomesoderm krox gene, the Krox transcription factor activates the otx gene, the products of which provide positive inputs into other endoderm regulators, including the pleiotropic, endoderm-specific gatae gene. But the gatae gene product in turn feeds back on the otx gene, locking the endoderm regulatory state in an “on” position (4, 19). The modular organization of the network is just becoming possible to perceive. But it is of potentially large importance for modeling its function, for reconstructing (or redesigning) it in the laboratory, and for understanding its evolution.

Dorsal–Ventral Patterning of the Drosophila Embryo

Dorsal–Ventral Specification and Development of Organogenic Territories. Dorsal–ventral patterning is implemented by the graded distribution of a maternal transcription factor, Dorsal, and culminates in the differentiation of specialized tissues, including cardiac mesoderm, the ventral midline of the nerve cord, and the amnioserosa (9). During a period of just 90 min, from syncytial stages to the onset of gastrulation, the dorsal–ventral axis is subdivided into three basic tissues: mesoderm, neurogenic ectoderm, and dorsal ectoderm (30). Each of these tissues generates multiple cell types during gastrulation, ≈3–5 h after fertilization. Dorsal regions of the mesoderm form cardiac tissues (reviewed in ref. 31). Ventral regions of the neurogenic ectoderm form the mesectoderm or ventral midline, which is essential for the patterning of the neurons that comprise the ventral nerve cord (reviewed in ref. 32). Finally, the dorsal-most regions of the dorsal ectoderm form a contractile extraembryonic membrane called the amnioserosa, which is essential for the process of germband elongation after gastrulation (33).

The dorsal–ventral patterning network is composed of nearly 60 genes (Fig. 2). Twelve of the genes encode proteins that are active in the perivitelline matrix surrounding the plasma membrane of the oocyte. They are responsible for creating an activity gradient of the Spitz ligand on the surface of the unfertilized egg, with peak levels in ventral regions and lower levels in more dorsal regions (34). After fertilization, Spitz interacts with the Toll receptor, which triggers an intracellular signaling cascade that releases the Dorsal transcription factor from the Cactus inhibitor in the cytoplasm (reviewed in ref. 35). This regulated nuclear transport is restricted to ventral and lateral regions of the early embryo and is thought to mirror the extracellular gradient of the active Spitz ligand.

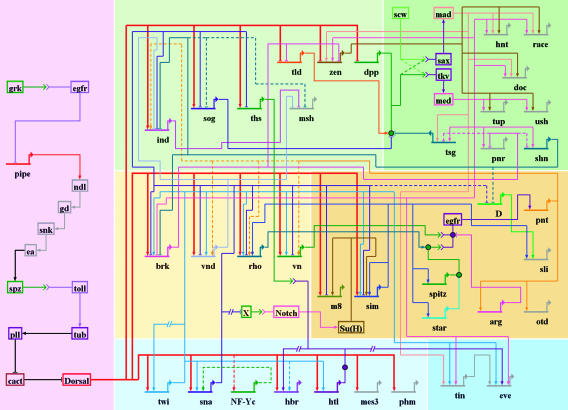

Fig. 2.

The dorsal–ventral GRN in Drosophila. The overall presentation is similar to that in Fig. 1. The diagram represents regulatory inputs and outputs for 46 genes expressed in the early embryo, from 2 to 5 h after fertilization. During this 3-h window, the syncytial embryo undergoes cellularization, mesoderm invagination, and the rapid phase of germband elongation. The color coding, from bottom to top, represents the three primary embryonic tissues as follows: mesoderm (Bottom, blue), ventral neurogenic ectoderm (Middle, yellow), and dorsal neurogenic ectoderm plus dorsal ectoderm (Top, yellow). The light shading to the left of the diagram represents syncytial stages, between 2 and 3 h after fertilization. The darker shading to the right represents cellularized embryos undergoing gastrulation. Dorsal–ventral patterning is initiated by the graded distribution of the Dorsal transcription factor. Peak levels of Dorsal enter nuclei in ventral (bottom) regions of the embryo, intermediate levels in lateral regions that form the ventral neurogenic ectoderm, and low levels in the dorsal neurogenic ectoderm. This Dorsal nuclear gradient is formed by the differential activation of the Toll signaling pathway (35), which in turn depends on the localized transcription of pipe in ventral follicle cells of the egg chamber (57). The pipe gene is probably repressed by EGF signaling, which is restricted to dorsal follicle cells because of the asymmetric position of the oocyte nucleus (58). Localized transcription of pipe in ventral follicle cells leads to a serine protease cascade on the ventral surface of the growing oocyte (ndl, gd, snk, and ea) that cleaves an inactive precursor form of the Spatzle (spz) ligand (59). The active ligand is thought to be deposited in a graded fashion along the ventral and lateral surface of the unfertilized egg. After fertilization, the Spz gradient leads to the Dorsal nuclear gradient within the syncytial embryo. High levels of Dorsal activate several genes in ventral regions that constitute the presumptive mesoderm, including twist (twi), snail (sna), NF-YC (a specialized component of the general NF-Y CCAAT binding complex), the FGF Heartless receptor (Htl), and Heartbroken (Hbr; also called Dof and Stumps), which transduces FGF signaling within the cell (30, 36). Twi is an activator that works in concert with Dorsal to activate sna expression in the mesoderm (9), and there is evidence that Twi also helps activate htl and hbr (36). Dorsal, Twi, and Sna regulate a large number of genes during the syncytial phases of dorsal–ventral patterning, including brk, vnd, rho, and vn, which are selectively activated in ventral regions of the neurogenic ectoderm (60). Dorsal and Twi work in a synergistic fashion to activate these genes, whereas the Sna repressor excludes their expression from the ventral mesoderm. Low levels of the Dorsal gradient activate short gastrulation (sog) and thisbe (ths) throughout the neurogenic ectoderm, in both dorsal and ventral regions (9, 30). Both genes encode secreted signaling molecules; Sog inhibits Dpp signaling (61), whereas Ths is related to FGF8 and activates FGF signaling in the dorsal mesoderm during gastrulation (see below). Low levels of Dorsal also repress tolloid (tld), zerknullt (zen), and decapentaplegic (dpp), which are required for the patterning of the dorsal ectoderm after cellularization (9). Definitive tissues begin to arise from each of the generic embryonic territories at the onset of gastrulation. The shading highlights the tinman (tin) and even-skipped (eve) genes, which gives rise to derivatives of the dorsal mesoderm such as visceral and cardiac muscles (31). eve is activated by Twi, Tin, Ets-containing transcription factors induced by FGF signaling, and Smad transcription factors induced by Dpp signaling after the internal dorsal mesoderm comes into contact with the dorsal ectoderm after gastrulation (31, 62). The shading in the central neurogenic ectoderm highlights a positive feedback system that is coordinated by the regulatory gene sim. sim is activated by Dorsal, Twi, and Su(H), the transcriptional effector of Notch signaling (44, 45). An unknown Notch signal emanating from the mesoderm induces sim expression in the ventral-most row of cells in the neurogenic ectoderm. Sim activates several components of the EGF signaling pathway, including rho, star, and spitz (47–49). Rho and Star are required for the processing of the Spitz ligand (63), which activates a ubiquitous EGF receptor (egfr). Activation of EGF signaling leads to the induction of pointed p1 (pnt) expression, which activates orthodenticle (otd) in the ventral midline (51, 52). EGF signaling and pnt either directly or indirectly maintain the expression of several genes in the neurogenic ectoderm that were previously activated by Dorsal plus Twi, including ind and vnd, which encode regulatory proteins that pattern the future ventral nerve cord (53, 55). Sim also participates in the activation of slit (sli), which encodes a signaling molecule required for the proper organization of the neurons that comprise the nerve cord (50). Finally, the shading on top (right) highlights the differentiation of two derivatives of the dorsal ectoderm: the dorsal epidermis and amnioserosa. A Dpp activity gradient is created in the dorsal ectoderm from the combined action of the Sog inhibitor emanating from the neurogenic ectoderm and the Tld protease, which releases Dpp from Sog at the dorsal midline (61). Dpp works together with a ubiquitous bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling molecule called Screw (Scw). Peak levels of Dpp and Scw signaling at the dorsal midline lead to the phosphorylation and nuclear transport of two Smad transcription factors, Mad and Medea (med) (64). Mad and Medea, along with the Zen homeodomain regulator, activate a number of genes required for the differentiation and function of the amnioserosa, including hindsight (hnt) and Doc (a Tbx6 transcription factor) (65). Lower levels of Dpp plus Scw signaling activate a number of regulatory genes throughout the dorsal ectoderm, including tailup (tup), u-shaped (ush), pannier (pnr), and schnurri (shn) (66). These genes respond to lower levels of Mad plus Medea, or as drawn in the diagram, respond solely to a particular activator complex containing Medea. Shn functions as a repressor that maintains the boundary between the neurogenic ectoderm and dorsal ectoderm by repressing brk (43) and neurogenic genes such as msh, which is expressed in the dorsal-most regions of the neurogenic ectoderm (53).

GRN. The Dorsal nuclear gradient leads to the differential expression of nearly 50 genes across the dorsal–ventral axis (e.g., see ref. 30). Roughly half the genes encode sequence-specific transcription factors, whereas the other half encodes components of cell signaling pathways. For example, high levels of Dorsal activate regulatory genes such as twist (twi) and snail (sna) (9) but also activate two components of the FGF signaling pathway, the FGF receptor Heartless (Htl) and the cytoplasmic effector Heartbroken (Hbr)/stumps/Dof (36). Cis-regulatory modules have been identified, and in many cases characterized, for about half of the zygotically expressed genes shown in the network.

Twi is an immediate early target gene of the Dorsal gradient (e.g., see ref. 37). It is activated by high levels of the gradient in ventral regions that form mesoderm. The Twi protein is synthesized in the presumptive mesoderm but diffuses approximately four to five “cell” diameters into ventral regions of the neurogenic ectoderm in the syncytial embryo (38, 39). Twi regulates nearly half of the known Dorsal target genes, including most of those activated in the mesoderm and ventral regions of the neurogenic ectoderm. Dorsal and Twi function in an additive fashion to activate a number of genes in the ventral mesoderm before the onset of gastrulation (e.g., see ref. 36). The Sna repressor is also deployed during the initial phases of the dorsal–ventral network. Like Twi, Sna regulates a large number of Dorsal target genes, particularly those expressed in the neurogenic and dorsal ectoderms (e.g., see ref. 3). In principle, these genes can be activated in the mesoderm by high levels of Dorsal but are kept off by the Sna repressor. Thus, dorsal–ventral patterning begins with an interlocking set of three transcription factors, Dorsal, Twi, and Sna.

There are two overall features of the dorsal–ventral patterning network that we wish to emphasize, because they reveal differences and similarities with the sea urchin endomesoderm network discussed above. First, during the early phases of development, there is the extensive use in the Drosophila dorsal–ventral patterning network of transcriptional repressors to establish boundaries of gene expression (Fig. 2 Left). In the sea urchin network, although there are negative feedbacks and cross-regulations within territories, the boundaries are set by lineage and signaling interfaces. Second, during this initial phase, there are very few examples of positive autofeedback or positive cross-regulatory feedback loops such as that in Fig. 1D. We argue that this specific circuitry has evolved to generate dynamic and transient patterns of gene expression in syncytial embryos, which essentially lack intercellular signaling mechanisms. In contrast, after cellularization, the circuitry exhibits autoregulation and positive feedback loops involving intercellular signaling pathways (Fig. 2 Right). These loops implement stable networks of cellular differentiation during gastrulation, and they are essentially similar to those seen in the sea urchin endomesoderm network.

Repression and Formation of Gene Expression Boundaries. Transcriptional repression plays a pervasive role in the initial patterning of the embryo. Four of the seven regulatory genes activated by the Dorsal gradient in syncytial embryos encode sequence-specific repressors (Sna, Brinker, Vnd, and Ind). The Sna repressor creates a boundary between the presumptive mesoderm and neurogenic ectoderm by excluding the expression of at least seven different Dorsal target genes (e.g., see ref. 3). Sna is transiently expressed in the mesoderm and lost from the mesoderm during gastrulation (40). The Brinker repressor helps create a boundary between the neurogenic and dorsal ectoderms by repressing Dpp signaling components that are required for the differentiation of specialized dorsal tissues such as the amnioserosa (41, 42). Brinker maintains this boundary by repressing the Schnurri gene (43), which encodes a repressor that establishes the dorsal limits of neurogenic genes (e.g., msh).

Regulatory Circuitry Following Cellularization. Stable circuits of autoregulation and positive feedback loops are not seen until the onset of gastrulation. The regulatory gene sim coordinates a subcircuit, or kernel, within the dorsal–ventral network that is essential for the patterning of the neurogenic ectoderm. Sim is activated by a combination of Dorsal, Twi, and Notch signaling (44, 45). Because of this requirement for Notch, sim expression is not detected until the completion of cellularization. The Sna repressor keeps sim off in the ventral mesoderm (45) and restricts the pattern to the ventral-most cells of the neurogenic ectoderm. Sna also represses an unknown inhibitor of Notch signaling (44, 45). As a result, a Notch signal originates from the ventral mesoderm and activates the Supressor of Hairless [Su(H)] transcription factor at the leading edge of the neurogenic ectoderm that is adjacent to the mesoderm. Once sim is activated in this single line of cells, it maintains its own expression through autoregulation (46). The Sim transcription factor also activates genes that encode components of the EGF signaling pathway, including star, rhomboid (rho; late expression), and spz, which activates the EGF receptor in ventral regions of the neurogenic ectoderm (e.g., see refs. 47–49). Sim and EGF signaling regulate a number of genes required for the differentiation and patterning activities of the ventral midline, including orthodenticle and slit (50).

The EGF signaling circuit “locks down” localized patterns of gene expression within the neurogenic ectoderm that are initially established by transient regulators such as Dorsal and Sna. In particular, EGF signaling maintains expression of the Pointed transcription factor, which, in turn, sustains the expression of vnd, rho, and vn (51). It would appear that the EGF/Pointed pathway replaces the transient Dorsal gradient to maintain differential patterns of vnd, and possibly ind, within the neurogenic ectoderm (52). The vnd gene encodes a transcription factor that is required for the specification of medial neuroblasts, whereas Ind is required for intermediate neuroblasts within the ventral nerve cord (reviewed in ref. 53). Vnd functions as a repressor to form the ventral limit of the ind expression pattern (54), and, similarly, Ind delineates the msh expression pattern, which specifies the lateral neuroblasts (53). The sequential and interlocking patterns of vnd, ind, and msh also are seen in the vertebrate neural tube (reviewed in ref. 55).

Future Prospects

GRNs provide a means of understanding evolution of body plans. For example, after half a billion years of independent evolution, the regulatory kernel from the sea urchin endomesoderm network (Fig. 1D) is exactly retained in the genome of a starfish (56). It is similarly used in both systems to create the embryonic endoderm, although much else of the regulatory wiring has changed since divergence. Evolutionary changes in GRNs that control developmental processes must be the basis for morphological change. But to explicitly demonstrate this fundamental principle will require the synthesis of many more high-quality GRNs governing diverse developmental processes in a variety of animal groups. Furthermore, as even the beginnings of comparative GRN analysis suggest, such efforts will produce fascinating insights into the structure and organization of network architecture itself.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dmitri Papatsenko for creating Fig. 2 and Angela Stathopoulos and Rob Zinzen for access to unpublished results. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HD37105.

Abbreviation: GRN, gene regulatory network.

References

- 1.Small, S., Blair, A. & Levine, M. (1992) EMBO J. 11, 4047–4057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidson, E. H. (2001) Genomic Regulatory Systems: Development and Evolution (Academic, San Diego).

- 3.Gray, S., Szymanski, P. & Levine, M. (1994) Genes Dev. 8, 1829–1838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson, E. H., Rast, J. P., Oliveri, P., Ransick, A., Calestani, C., Yuh, C.-H., Minokawa, T., Amore, G., Hinman, V., Arenas-Mena, C., et al. (2002) Science 295, 1669–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson, E. H., McClay, D. R. & Hood, L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1475–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolouri, H. & Davidson, E. H. (2002) BioEssays 24, 1118–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oliveri, P. & Davidson, E. H. (2004) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochoa-Espinosa, A., Yucel, G., Kaplan, L., Pare, A., Pura, N., Oberstein, A., Papatsenko, D. & Small, S. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4960–4965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stathopoulos, A. & Levine, M. (2002) Dev. Biol. 246, 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koide, T., Hayata, T. & Cho, K. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4943–4948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh, H. & Medina, K. L. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4949–4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue, T., Wang, M., Ririe, T., Fernandes, J. & Sternberg, P. W. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4972–4977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Papatsenko, D. & Levine, M. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4966–4971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Istrail, S. & Davidson, E. H. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4954–4959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson, E. H., Cameron, R. A. & Ransick, A. (1998) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 125, 3269–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson, E. H., Rast, J. P., Oliveri, P., Ransick, A., Calestani, C., Yuh, C.-H., Minokawa, T., Amore, G., Hinman, V., Arenas-Mena, C., et al. (2002) Dev. Biol. 246, 162–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveri, P., Carrick, D. M. & Davidson, E. H. (2002) Dev. Biol. 246, 209–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveri, P., McClay, D. R. & Davidson, E. H. (2003) Dev. Biol. 258, 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yuh, C.-H., Dorman, E. R., Howard, M. L. & Davidson, E. H. (2004) Dev. Biol. 269, 536–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Logan, C. Y., Miller, J. R., Ferkowicz, M. J. & McClay, D. R. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emily-Fenouil, F., Ghiglione, C., Lhomond, G., Lepage, T. & Gache, C. (1998) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 125, 2489–2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weitzel, H. E., Illies, M. R., Byrum, C. A., Xu, R., Wikramanatake, A. H. & Ettensohn, C. A. (2004) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 131, 2947–2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wikramanayake, A. H., Huang, L. & Klein, W. H. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 9343–9348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minokawa, T.& Davidson, E. H. (2005) Dev. Biol., in press.

- 25.Sherwood, D. R. & McClay, D. R. (1997) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 124, 3363–3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sherwood, D. R. & McClay, D. R. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 1703–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sweet, H. C., Hodor, P. G.& Ettensohn, C. A. (1999) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 126, 5255–5265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Revilla-i-Domingo, R., Minokawa, T. & Davidson, E. H. (2004) Dev. Biol. 274, 438–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calestani, C., Rast, J. P. & Davidson, E. H. (2003) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 130, 4587–4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stathopoulos, A., Van Drenth, M., Erives, A., Markstein, M. & Levine, M. (2002) Cell 111, 687–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaffran, S. & Frasch, M. (2002) Circ. Res. 91, 457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kasai, Y., Stahl, S. & Crews, S. (1998) Gene Expression 7, 171–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frank, L. H. & Rushlow, C. (1996) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 122, 1343–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peri, F., Technau, M. & Roth, S. (2002) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 129, 2965–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belvin, M. P. & Anderson, K. V. (1996) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 393–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stathopoulos, A., Tam, B., Ronshaugen, M., Frasch, M. & Levine, M. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 687–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang, J. & Levine, M. (1993) Cell 72, 741–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kosman, D., Ip, Y. T., Levine, M. & Arora, K. (1991) Science 254, 118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leptin, M. (1991) Genes Dev. 5, 1568–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alberga, A., Boulay, J. L., Kempe, E., Dennefeld, C. & Haenlin, M. (1991) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 111, 983–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rushlow, C., Colosimo, P. F., Lin, M.C., Xu, M. & Kirov, N. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 340–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, H., Levine, M. & Ashe, H. L. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 261–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pyrowolakis, G., Hartmann, B., Muller, B., Basler, K. & Affolter, M. (2004) Dev. Cell 7, 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morel, V. & Schweisguth, F. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 377–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cowden, J. & Levine, M. (2002) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 129, 1785–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nambu, J. R., Lewis, J. O., Wharton, K. A., Jr., & Crews, S. T. (1991) Cell 67, 157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee, C. M., Yu, D. S., Crews, S. T. & Kim, S. H. (1999) Int. J. Dev. Biol. 43, 305–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Golembo, M., Raz, E. & Shilo, B. Z. (1996) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 122, 3363–3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chang, J., Kim, I. O., Ahn, J. S. & Kim, S. H. (2001) Int. J. Dev. Biol. 45, 715–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zinn, K. & Sun, Q. (1999) Cell 97, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Golembo, M., Yarnitzky, T., Volk, T. & Shilo, B. Z. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 158–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gabay, L., Scholz, H., Golembo, M., Klaes, A., Shilo, B. Z. & Klambt, C. (1996) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 122, 3355–3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.von Ohlen, T. & Doe, C. Q. (2000) Dev. Biol. 224, 362–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiss, J. B., Von Ohlen, T., Mellerick, D. M., Dressler, G., Doe, C. Q. & Scott, M. P. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 3591–3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cornell, R. A., Ohlen, T. V. (2000) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 10, 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hinman, V. F., Nguyen, A., Cameron, R. A. & Davidson, E. H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 13356–13361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Amiri, A. & Stein, D. (2002) Curr. Biol. 12, R532–R534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nilson, L. A. & Schupbach, T. (1999) Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 44, 203–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roth, S. (1994) Curr. Biol. 4, 755–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Markstein, M., Zinzen, R., Markstein, P., Yee, K. P., Erives, A., Stathopoulos, A. & Levine, M. (2004) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 131, 2387–2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Podos, S. D. & Ferguson, E. L. (1999) Trends Genet. 15, 396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Halfon, M. S., Grad, Y., Church, G. M., Michelson, A. M. (2002) Genome Res. 12, 1019–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee, J. R., Urban, S., Garvey, C. F. & Freeman, M. (2001) Cell 107, 161–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raftery, L. A. & Sutherland, D. J. (2003) Trends Genet. 19, 701–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reim, I., Lee, H. H. & Frasch, M. (2003) Development (Cambridge, U.K.) 130, 3187–3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wharton, S. J., Basu, S. P. & Ashe, H. L. (2004) Curr. Biol. 14, 1550–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]