Abstract

Background

Breast cancer (BC) is the most common type of cancer in women. Among many risk factors of BC, mutations in BRCA2 gene were found to be the primary cause in 5–10% of cases. The majority of deleterious mutations are frameshift or nonsense mutations. Most of the reported BRCA2 mutations are protein truncating mutations.

Methods

The study aimed to describe the pattern of mutations including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and variants of the BRCA2 (exon11) gene among Sudanese women patients diagnosed with BC. In this study a specific region of BRCA2 exon 11 was targeted using PCR and DNA sequencing.

Results

Early onset cases 25/45 (55.6%) were premenopausal women with a mean age of 36.6 years. Multiparity was more frequent within the study amounting to 30 cases (66.6%), with a mean parity of 4.1. Ductal type tumor was the predominant type detected in 22 cases (48.8%) among the reported histotypes. A heterozygous monoallelic nonsense mutation at nucleotide 3385 was found in four patients out of 9, where TTA codon was converted into the stop codon TGA.

Conclusion

This study detected a monoallelic nonsense mutation in four Sudanese female patients diagnosed with early onset BC from different families. Further work is needed to demonstrate its usefulness in screening of BC.

Keywords: BRCA2, Monoallelic, Heterozygous, Stop Codon, Breast cancer, Sudanese patients

Background

Breast cancer (BC) is the most commonly diagnosed type of cancer in women, accounting for 25% of all cancer cases in the world; with much more cases recorded in developing countries than developed ones. In 2012, 1.67 million cases of BC resulted in 522,000 deaths [1–3]. In Africa, 324,000 deaths were reported to be caused by BC [1, 2]. The predisposition to BC appears to be affected by several factors, one of them is the high-risk BC gene mutation in BRCA2 (OMIM: 600185) (Gene ID: 675) (RefSeqGene: NG_012772) [4]. Although the incidence rate of gene mutation in BRCA2 is low, it is associated with a high lifetime risk of BC [5, 6]. This lifetime risk is variable among different population [7–10]. BRCA2 is believed to be the primary cause of 5 to 10% of all cases of BC [11]. About 45% of women, who inherited a defective BRCA2 allele, will develop BC when they reach the age of 70 [12, 13]. Mean age at onset of BC for BRCA2 mutation carriers is reported to be 42.8 years [14].

The human BRCA2 gene contains 27 exons, among which exon 11 is the largest one. The coding sequence (RefSeq transcript mRNA: NM_000059) was determined to be 11,385 bp, which codes for a protein of 3418 amino acids (Uniprot: P51587) (RefSeq protein: NP_000050) [15]. A study conducted in Central Sudan from 2001 to 2002 concluded that this gene plays a role in the etiology of BC [16]. In addition, in a genetic analysis performed on secondary school female students in Northern Sudan, some variants were detected in two groups free of BC, one with a family history of BC and the other without familial risks. Two BRCA2 mutations were reported in the group without a family history [17].

It is known that the majority of deleterious mutations in BRCA2 are either a frameshift or nonsense mutations [14, 18, 19]. The nonsense mutations have been reported more within exon 11 of early onset BC cases with high pathogenicity [14, 18]. It is found that about 90% of reported BRCA2 mutations are protein truncating [20]. In addition, the formation of nonsense-mediated RNA decay -as premature terminating inactivation codon- could lead to the production of a toxic partial protein [14]

Heterozygosity of BRCA2 mutations was found to be associated with a distinctive phenotype, which could lead to BRCA2 tumorigenesis, as altered heterozygous BRCA2 does not function well and the wild allele alone is not enough to maintain genomic stability. In other cases, it was suggested to be haploinsufficient. Furthermore, BRCA2 monoallelic carrier mutations were detected in patients with pancreas and breast cancer [21, 22].

Etiologically, scientific literature from African countries showed that reproductive factors more commonly associated with the development of BC are early menarche, pregnancy, and multiparity [23]. The situation is globally similar; as early menarche, late menopause, carriers of BRCA2 damaging variants, and early pregnancy before age of 30 years confer high-risk conditions for BC [24].

Unfortunately, the scientific articles from African countries lacked data about the risk conferred by familial cases as it has not been well investigated, although some studies suggested its etiological companion [16, 23]. This study aimed to screen BRCA2 mutations, taking into consideration the biggest region in the gene, exon 11, to find out and investigate variants or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) among known BC patients.

Methods

Study area

This study was carried out in Khartoum state at the Radiation and Isotope Center in Khartoum (RICK), which is one of the only two oncology centers in Sudan, and it provides oncological services for people from all parts of Sudan.

Sampling

Out of all Sudanese female patients diagnosed with BC (45 patients) attending RICK during March 2015, 10 patients were selected randomly for genetic sequencing and analysis. Four healthy subjects with no family history of BC and another one diagnosed with essential thrombocythemia who are free of BC have been added as controls. Blood specimens were collected using EDTA-vacutainer tubes from the selected patients and controls. The specimens were preserved at −20 °C.

Ethical considerations

All patients were informed and consented to participate in the study before collecting the samples. All patients were consented to publish the results of the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee of Sudan Ministry of Health-Khartoum state.

DNA extraction

For both patients and controls, DNA was extracted by Salting out technique according to the published protocol [25]. In addition, we added proteinase K at 56 °C to enhance white cells membrane breakdown. After 1 h, the DNA was extracted with concentration of 30 ng/ul, dissolved in 100 ul Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer, and kept for overnight at 4 °C, then preserved at −20 °C until use.

PCR amplification

Forty-five patients and five control samples were subjected to amplification using three primers sets (A, B and C) targeting three regions within BRCA2 gene exon 11 as described in (Table 1). This study focused only on the product of the second primer set (primer B) based upon stability and quality of this primer [26]. Primers were synthesized and purchased from Macrogen Incorporation (Seoul, South Korea). Annealing temperature was adjusted using Maxime PCR PreMix Kit i-Taq 20 μl (INTRON Biotechnology, South Korea) on several runs of PCR. The adjusted temperatures are described in (Table 1). Amplification for the targeted regions was done after addition of 15 ul Distilled water, 3 ul sample DNA and 1 ul of each forward and reverse to the ready-to-use master mix volume. PCR mixture was subjected to an initial denaturation step at 96 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 96 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 50 °C for 30 s, followed by a step of elongation at 72 °C for 60 s, the final elongation was at 72 °C for 10 min [26]. The PCR products were checked and analyzed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis at 100 V for 30 to 45 min and then bands were visualized by automated gel photo documentation system (Fig. 1). Only 10 patients and five controls yielded sufficient quality bands, and were subsequently selected for sequencing by the Sanger sequencing technique.

Table 1.

List of primers used to amplify BRCA2 gene selected regions

| PN* | Primer’s nucleotide sequence | PL* | AT* | Selected region | Am* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | F: 5′ AGA CAC AGG TGA TAA ACA AG ‘3 | 20 | 50 | 3020 to 3380 | 361 |

| R: 5′ CAA GGT ATT TAC AAT TTC AA ‘3 | 20 | 50 | |||

| B | F:5′ GCT CTC TGA ACA TAA CAT TAA G ‘3 | 22 | 50 | 3281 to 3731 | 451 |

| R: 5′ CAT TAT GAC ATG AAG ATC AG ‘3 | 20 | 50 | |||

| C | F: 5′ TGA GAC CAT TGA GAT CAC AGC ‘3 | 21 | 55 | 4967 to 5673 | 707 |

| R: 5′ TAG TCA CAA GTT CCT CAA CGC A ‘3 | 22 | 55 |

PN* Primer Name

PL* Primer length in base pair

AT* Annealing Temp

Am* Amplicon size (bp)

Fig. 1.

Illustrates PCR amplification results of the three tested regions (A, B & C) on 2% gel electrophoresis. MW: DNA ladder’s molecular weight where 100 bp was used. C7 to C1 lanes indicate primer C bands. A1 indicates primer A band. B7 down to B1 Lanes indicate primer B bands

Sequencing of BRCA2 gene

Sanger sequencing was performed for the PCR products. Both DNA strands were sequenced by Macrogen Company (Seoul, South Korea).

Bioinformatics analysis

For each sample, the two purified chromatogram (forward and reverse) nucleotide sequences were viewed and checked for quality by FinchTV program version 1.4.0 [27]. The NCBI Nucleotide database was searched for reference sequences. BRCA2 nucleotide sequence (NM_000059.3) was obtained and all regions were analyzed accordingly [10]. Additional high similarity sequences (AY436640.1) and (X95161.1) were obtained from NCBI database and were added as control sequences using nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) [28]. Any apparent changes within the tested sequences were noticed through multiple sequence alignment using BioEdit software [29]. All sequences were translated into amino acid sequences using online Expasy translate tool [30]. The resulted amino acid sequences were compared all together using BioEdit software.

SNP prediction

SIFT-software was used to check for the effect of SNPs on the protein; whether they are damaging or not [31]. Also, SNPs structural and functional impact on resultant protein was predicted by PolyPhen-2; which performs searches in several protein structure databases for 3D protein structures, multiple alignments of homologous sequences and amino acid contact information. [32]

Project hope was used to analyze the structural and conformational variations that have resulted from single amino acid substitutions corresponding to the single nucleotide substitutions [33], then the protein stability was assessed by I-Mutant [34], In addition to web-based applications for rapid evaluation of the disease-causing potential of DNA sequence alterations called MutationTaster2 [35]

Results

Study population characteristics

Patient characteristics, clinical and histological parameters

Forty-five women with BC, who attended RICK-center for treatment and follow-up, were selected for the study, their age ranged between 27 to 80 years (mean age was 45.9 years). Out of 45 patients, 25 (55.6%) were premenopausal women (Early onset cases) with a mean age of 36.6 years. On the other hand, late onset cases - who were 46 years or more - had a mean age of 57.4 years. The majority of women in the study were multiparous 30/45 (66.6%), with an average number of 4.1 parities. Patients were from 17 tribes, Ja’alya, Shaygeya, and Dnagla were the most frequent tribes (Table 2). Familial history of any type of cancer was found in 11 cases; of which six cases had BC in the family. Abortion was detected in 10 cases (22.2%), with an estimated frequency of 1–5 times. Among the married cases (88.8%), three cases were married at less than 20 years of age.

Table 2.

Patients demographic and characteristics

| Variable | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Early (≤45 years) | 25/45 (55.6%) |

| Late (≥46 years) | 20/45 (44.4%) | |

| Family history | Breast cancer | 6/45 (13.3%) |

| Other cancer | 5/45 (11.1%) | |

| No family history of any cancer | 34/45 (75.6%) | |

| Parturition | Multiparous | 30/45 (66.7%) |

| Nulliparous | 13/45 (28.9%) | |

| Primiparous | 2/45 (4.4%) | |

| History of Abortion | Yes | 10/45 (22.2%) |

| No | 35/45 (77.8%) | |

| Marital status | Currently Married | 41/45 (91.1%) |

| Single | 3/45 (6.7%) | |

| Previously married | 1/45 (2.2%) | |

| Tribe | Ja’alya | 5 (11.1%) |

| Shaygeya | 5 (11.1%) | |

| Dnagla | 4 (8.9%) | |

| Noba | 3 (6.7%) | |

| Rezaigat | 3 (6.7%) | |

| Others | 25 (55.5%) | |

| Geographical region | Central Sudana | 21/45 (46.7%) |

| Western Sudan | 15/45 (33.3%) | |

| Northern Sudan | 6/45 (13.3%) | |

| Eastern Sudan | 3/45 (6.7%) | |

| Tumor site | Unilateral | 35/45 (77.8%) |

| Bilateral | 4/45 (8.9%) | |

| Unknown | 6/45 (13.3%) | |

aComprising both Khartoum 16 cases and AlGezirah 5 cases

Available histotype data showed that ductal tumors were the predominant type (detected in 22 cases (48.8%)). Lobular and mucinous were reported in 5 and 2 cases respectively. Papillary adenocarcinoma was detected in only one patient, as a secondary deposit in bone. The right side was affected by the disease in 20 patients (44.4%). Four patients had bilateral disease (Table 2).

Mean age at diagnosis in the group selected for DNA sequencing was 39 years (27 to 57 years). Nine patients were multiparous (mean of parity was 3.5). In this group, while the right-side was predominantly affected, one patient had bilateral breast involvement. Cancer grades were between II to III. Clinical staging showed lymph nodes involvement in five cases. Distal metastasis was noted in the liver in one patient; while bone and lung involvement were documented in another case. Control individuals were free of BC and free of family history involvement. The youngest patient within the study was 27 years old and was the only case free of lymphatic involvement (Table 3).

Table 3.

The highly purified Breast Cancer Patients demographic, clinical, histological parameters with the nonsense mutation

| Patients ID | Age | Family history of BC | grade | Stage and Metastasis | histotype | BC site | Nonsense Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | 51 | second and third degree*1 | NA | T1N1M0 | NA | Rt/Unilateral | |

| B2 | 45 | No | NA | TxNxMx | NA | Bilateral | Detected |

| B13*2 | 27 | No | III | T2N1M0 | Ductal | Lt/Unilateral | |

| B14 | 35 | Second degree | NA | TxNxM1 (Liver) | Lobular | Rt/Unilateral | Detected |

| B18 | 41 | No | II | TxNxMx | Ductal | Rt/Unilateral | |

| B23 | 27 | No | NA | T2N0M0 | NA | Rt/Unilateral | Detected |

| B24 | 39 | No | NA | TxNxMx | NA | Rt/Unilateral | Detected |

| B29 | 37 | No | III | TxNxMx | Ductal | Rt/Unilateral | |

| B39 | 30 | No | II | T4N1Mx | Ductal | Lt/Unilateral | |

| B44 | 57 | No | I | TxNxM1 (Bone/Lung) | Ductal | Rt/Unilateral |

*1Two of the relatives involved by breast cancer

*2This patient was excluded from bioinformatics analysis due to inconsistency and poor quality

Bioinformatics result analysis

The sequencing data was checked for consistency and quality, and one patient’s sequence has been excluded for inconsistency.

By using the multiple sequence alignment tool BioEdit, the analysis of nine tested patients and five controls of the modified sequencing results -compared to NCBI RefSeq transcript mRNA (NM_000059.3) - revealed a single nucleotide change (substitution) within region B at position 3385 yielding a stop codon (TGA) in four patients as (TTA/TGA). The corresponding amino acid sequences appeared as gaps in (Fig. 2); in which the normal amino acid Leucine no longer existed as a result of premature termination (L1053X).

Fig. 2.

a: I. patient. Illustrates the sequencing result of the chromatogram of one of the tested patients with the substitution mutation marked by a small square. The monoallelic change is more apparent. II. Control. Illustrates the sequencing result of the chromatogram of the control with the normal sequence. A - Adenine, G - guanine, T - thymine, C - cytosine. III. Illustrates Bioedit multiple sequences alignment with substitution of thymine by guanine. b: I. This frame illustrates the nucleotide sequence (in small letters) and their corresponding amino-acids sequence (in capital letters) of a selected frame (5' to 3' frame 1) of the tested region (region B) of BRCA2. The dash (−) represents absence of amino-acid (stop codon). This figure was taken from Expasy online translate tool. II. this frame illustrates the amino-acids sequence in a compacted form. The dash (−) represents absence of amino acid. This figure was taken from Expasy online translate tool

Another two single nucleotide changes had been noticed. The first one occurred in two patients with the previously noted L1053X and resulted in Adenine being replaced by Guanine at position 3474 (haplotype), and the corresponding amino acid change was N1083D. This variant was predicted to alter normal protein features in both function and structure -as shown by SIFT sequence and Project Hope. Also it was predicted to decrease protein stability -by I-Mutant. However, it was expected to probably harmless by MutationTaster2 and benign by polyphen-2. The other detected mutation -rs1801406- was silent (K1132 K) and noted in six cases, two of them had both L1053X and N1083D changes, (Table 4).

Table 4.

Detected patients among the refined group to carry the following variants within BRCA2 exon 11 primer B region

| Patient ID | Age | Parturition | Origin | Tribe | Variants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsense | Misense | Silent | |||||

| T3385G | A3474G | A3623G | |||||

| B1 | 51 | 4 | Central-kha | Ja’alya | |||

| B2 | 45 | 4 | Western | Noba | Detected | Detected | |

| B14 | 35 | 2 | Northernb | Ja’alya | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| B18 | 41 | 5 | Central-Kh | Kawahla | |||

| B23 | 27 | 3 | Central-Gc | Ja’alya | Detected | Detected | Detected |

| B24 | 39 | 3 | Western | Detected | |||

| B29 | 37 | 2 | Central-Kh | Bataheen | Detected | ||

| B39 | 30 | 5 | Western | Kenany | Detected | ||

| B44 | 57 | 6 | Western | Mema | Detected | ||

aKhartoum

bRiver-Nile

cAlGezirah

Nonsense mutations

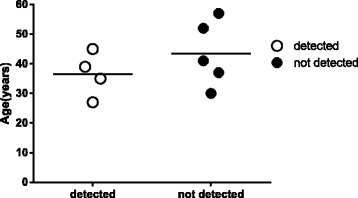

Patients carrying this mutation were premenopausal, with a mean parity of 3.0. The mean age of patients with and without the nonsense mutation was 36.5 and 40.5 years respectively, with a mean difference of four years as illustrated in (Fig. 3). Two patients bearing this SNP were from Ja’alya tribe and one of them had a history of secondary liver deposits (Table 3).

Fig. 3.

The mean age in breast cancer patients with and without the detected nonsense mutation

Discussion

The significant change noted in this study was a monoallelic T3385G stop codon. A variant found with different nomenclatures, c.3158 T > G and n.3386 T > G (Table 5). This SNP was previously identified by Lubiniski in a study aimed to screen familial cases presented with seven different phenotypes including BC and Ovarian Cancer. He studied Ovarian Cancer Cluster Region (OCCR) within the BRCA2 coding sequence. This region was noted more consistently to determine hereditary familial cancer cases. He found termination sequence at position T3386G [18, 36, 37]. The change was similar in both studies (T converted to G) but appears in different positions. However, the resulted-corresponding amino acid sequence provided the same change in both studies (L1053X). Also the mutation has been found as a germline-type but in prostatic cancer cases [38, 39] and one study found this variant within a control subject [40]. The geographic distribution of the variant within detected population has been covered (Table 6).

Table 5.

highlights the stop codon L1053X with different nomenclatures described by ClinVar NCBI database

| The study stop codon | SNP ID | Human Genome Variation Society HGVS | Breast Cancer Information Core BIC | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Accessions | Stop codon position | ||||

| T3385G, L1053X | rs41293477 | c.3158 T > G | U43746.1 | n.3386 T > G | [18] [40] [53] [39] [38] |

| (RefeSeq) NM_000059.3 | c.3385 T > G | ||||

Table 6.

The geographic provenience of the samples previously detected with the mutation L1053X

| SAMPLE geographic provenience | L1053X mutation frequency | Type | Cases | Age | The study highlighted the mutation | Sample source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada, USA and Poland*1 | 1 family (not specified) | Germline | Familial BC | - | Lubinski, et al. 2004 [18] | Research centers |

| UK, USA*2 | 1 control subject (not specified) | - | 54 | Song H, et al. 2014 [40] | Gayther SA, et al. 2007 [54] | |

| Australia | 1 case; as HRM High Resolution Melting Method validation | Method validation | Not specified | - | Hondow HL, et al. 2011 [53] | Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre and the Kathleen Cunningham Foundation Consortium for Research into Familial Breast Cancer (kConFab) |

| UK, Netherlands*3 | 1 case | Germline | Prostate ca | 54.6 | Sandhu SK, et al. 2013 [39] | Fong PC, et al. 2009 [55] |

| UK | 1 case | Germline | Prostate ca with family history of BC and Lung ca | 46 | Kote-Jarai Z, et al. 2011 [38] | Eeles RA, et al.1997 [56] |

*1Cancer centres where the sampling protocols including family pedigree were performed

*2based on large population studies: the population-based SEARCH study UK and the hospital-based Mayo clinic study from USA

*3The centers where the study was performed: at the Royal Marsden National Health Service (NHS) Foundation Trust (United Kingdom) and the Netherlands Cancer Institute (the Netherlands)

The patients carrying the mutation had a mean age of 36 years; similar to what was previously reported in Sudan by Awadelkarim et al. who analyzed 35 patients with breast cancer. In terms of parity and menopausal status of the subjects, both studies showed the same trend as the majority of BC cases were premenopausal and multiparous. Furthermore, patients from Ja’alya tribe were found to have truncating mutations in both studies [16].

Our mutation is located within the central region, which possesses eight functional BRC repeats to bind RAD51 -that is essential for Homologous Recombination (HR)- to facilitate its loading onto single strand DNA, where a repair process is needed [41–44]. Accordingly, any defect of this loading will result in failure of Homologous recombination and the DNA double strand breaks remain altered [45].

From the NCBI database; BRCA2 human has a total of about 10,736 known SNPs, and more than 466 reported truncating mutations. One of these mutations is the K3326X (rs11571833). This mutation has been associated with a 26% increase in the risk of developing breast cancer in European, Latin Americans, and Indian populations. K3326X mutation has been associated with a 2.5 fold increase in risk of squamous lung cancer [46]. Another example of stop codon mutation in BRCA2 is Y3308X (rs4987049) which has been found in Asian, European, Sub-Saharan and African American populations. Other stop mutations in BRCA2 coding region lack frequency data [47]. Seventy Nigerian breast cancer patients with ages younger than 40 years were studied, and one BRCA2 truncating mutation 3034del4 within exon 11 has been reported [48]. The same mutation has been reported in a study of 39 early onset breast cancer (< 40 years) patients in Nigeria. Although 30 variants of BRCA2 were detected, there was only one (3034del4) truncating mutation, located in exon 11 [49].

The N1083D mutation was not previously reported and such a companion is shown in this study by this variant regarding the position to be in continuation -sitting- few steps later after the monoallelic nonsense variant L1053X, so this position proves to be of no significance because it is situated after the nonsense mutation. The other variant, A3623G, was silently expressed as K1132 K, was detected with high frequency among earlier cases, and was involved with three cases detected with the nonsense L1053X including the two N1083D variants. The silent mutation K1132 K was reported among familial cases as the benign non-virulent bearing-characteristic and was found frequently within early onset <50 with mean age 37.5 and more frequently among Asian population and was noticed its high occurrence among a Chinese population [50, 51]. This variant has been recorded with other 13 variants as a recurrent situation among a Belgian population [52].

A technical facility to establish the outcome/resulting truncation inactivation is not available and it is very difficult to handle such a technical assessment. Though all 45 patients’ DNA had been extracted, only 10 patient’s extracts were sequenced owing to financial constraints. Also, due to these financial constraints only the product of one primer with the highest stability was subjected to further analysis in this study. Moreover, the sample size limits the generalizability of this study, but for this variant to be generalized to the Sudanese population, further studies using larger sample size will be needed in the future. In a general context, BRCA genes have not got wide assessment within our geographic region, thus in such scarce way of expression of BC genetic characteristics regarding some countries including Sudan, data presented in our study could be more raised. Most of BRCA2 mutations variants detected within African literature have been gathered in (Table 7) with their corresponding country of origin.

Table 7.

Most of the BRCA2 mutations variants detected within African literature

| BRCA2 variants | Country | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| c. 2826_2829delAATT | South Africa | van der Merwe NC, et al. 2012 [57] | |

| c. 5771_5774delTTCA | |||

| c. 6448dupTA | |||

| c. 7934delG | Founder- | ||

| c.5946delT | |||

| C.8162delG | Schoeman M, et al. 2013 [58] | ||

| c.5999del4 | |||

| c.6174delT | |||

| c.582G > A | Francies FZ, et al. 2015 [59] | ||

| c.5771_5774delTTCA | |||

| c.5213_5216delCTTA | |||

| c.8754 + 1G > A | |||

| c.9097_9098insA | |||

| c.4798_4800delAAT | |||

| c.7712A > G | |||

| c.9875C > T | |||

| c.7934delG founder | founder | Afrikaner population of South Africa | Seymour HJ, et al.2016 [60] |

| c.6621delA | South Africa | ||

| c.6761_6762delTT | |||

| c.5073dupA | Morocco | LAARABI FZ, et al.2011 [61] | |

| c.3381delT | Tazzite A, et al. 2012 [62] | ||

| c.7110delA | |||

| c.7235insG | |||

| c.517-1G > A | |||

| c.6428 C > A | Guaoua S, et al.2014 [63] | ||

| c.745-1G > A | Jouhadi H, et al.2016 [64] | ||

| c.5682insA | Tunisia | Troudi W, et al. 2007 [65] | |

| c.1309del4 | |||

| c.-25G > A | |||

| c.6301 A > C | |||

| c.1595 A > T | |||

| c.7242 A > G | |||

| c.865 A > G | |||

| c.1310_1313del (1538delAAGA) | Fourati A, et al. 2014 [66] | ||

| c.-26G > A | Riahi A, et al.2014 [67] | ||

| c.681 + 56C > T | |||

| c.793 + 65_793 + 65delT | |||

| C.8503 T > C | |||

| 5456delGTAGCA | Hadiji-Abbes N,et al. 2015 [68] | ||

| c.1313dupT | Riahi A, et al.2015 [69] | ||

| c.7654dupT | |||

| c.67 + 62 T > G | |||

| c.8487 + 47C > T | |||

| c.8360G > A | |||

| c.8830A > T | |||

| c.9875C > T | |||

| c.10240A > G | |||

| c.8182G > A | |||

| c.8503 T > C | |||

| c.1542_1547delAAGA | Riahi A, et al. 2017 [70] | ||

| c.5682insA | |||

| c.1309del4 | |||

| c.1310 1313delAAGA | Algeria | Cherbal F, et al. 2010 [71] | |

| c.5722 5723delCT | |||

| c.67 + 14 T > C | |||

| c.67 + 15 T > C | |||

| c.68–14 T > A | |||

| c.68-21 T > G | |||

| c.231 T > G | |||

| c.3555A > T | |||

| c.3868 T > A | |||

| c.5553C > T | |||

| c.5472 T > G | |||

| c.5592C > A | |||

| c.5976A > G | |||

| c.5985C > A | |||

| c.8487 + 19A > C | |||

| c.68-16 T > A | Cherbal F, et al.2012 [72] | ||

| c.475 + 25A > G | |||

| c.794-5A > T | |||

| c.1099G > A | |||

| c.2636C > A | |||

| c.2657A > G | |||

| c.2673C > G | |||

| c.5397A > T | |||

| c.5428G > T | |||

| c.6309A > C | |||

| c.6346C > G | |||

| c.9256G > A | |||

| c.7654dupA | Henouda S, et al.2016 [73] | ||

| c.1528G > T | |||

| Del exons 19–20 | |||

| c.6450del | |||

| c.7462A > G | |||

| c.1504A > C | |||

| c.5939C > T | |||

| c.1627C > A | |||

| c.3195_3198delTAAT | Sudan | Awadelkarim KD, et al.2007 [16] | |

| c.6406_6407delTT | |||

| c.8642_8643insTTTT | |||

| c.122C > T | |||

| c.6101G > A | |||

| c.68-7delT | |||

| 999TCAAA deleted (999del5) | Egypt | Bensam M, et al.2014 [74] | |

| 2256 T > C | |||

| 8934G > A | |||

| c.970G > A | Nigeria | Fackenthal JD, et al.2005 [49] | |

| c.1093A > C | |||

| c.1503A > G | |||

| c.2366 A > T | |||

| c.3014 T > C | |||

| c. 3188A > T | |||

| c. 3199A > G | |||

| c. 3492 T > C | |||

| c. 4299A > C | |||

| c. 4469C > T | |||

| c. 4791G > A | |||

| c. 5646A > G | |||

| c. 5932G > A | |||

| c. 5938C > G | |||

| c. 6741C > G | |||

| c. 7378C > A | |||

| c. 7470A > G | |||

| c. 7547A > G | |||

| c. 9058A > T | |||

| c. 9862G > C | |||

| 3034delACAA | |||

| ex2-11C > T | |||

| ex7-19C > T | |||

| ex11-43 T > C | |||

| ex12-200insC | |||

| ex17-40A > G | |||

| ex18 + 109G > A | |||

| ex21-36C > G | |||

| ex22-70C > T | |||

| ex26 + 106delT | |||

| 1538delAAGA c.1310_1313delAAGA | Zhang J, et al.2012 [75] | ||

| 1222delA | Fackenthal JD, et al.2012 [76] | ||

| 2630del11 | |||

| 3036delACAA | |||

| 4157delC | |||

| 5358delTGTA | |||

| 5369delATTT | |||

| 5469insTA | |||

| 5581delAC | |||

| 7482delAG | |||

| 9045delGAAA | |||

| Q3066X |

Conclusion

This study detected monoallelic L1053X mutation causing the same stop codon in BRCA2 protein sequence at the same position in four Sudanese female BC patients out of nine from different families. This nonsense mutation should be evaluated in further studies in a larger number of BC patients in both hetero-homozygosity re-evaluation and to check the reliability of using this stop codon as a screening tool for early detection of BC.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to acknowledge Al-Neelain University in Khartoum for their generous help in conducting this study. Also, we would like to thank Radiation and Isotope Center in Khartoum for their approval to this work to be done and their kind cooperation for samples collection and we appreciate the contribution of Africa city of Technology (Sudan). Also many thanks for our colleague Hadya Altayib for her beneficial cooperation, and we wish her the success in her project.

Availability of data and materials

Data access

The BRCA2 sequence data from this study have been submitted to the NCBI GeneBank under the following accession numbers and protein identifiers:

| Accession number | Protein ID |

| KT901805 | ALQ44025 |

| KT901806 | ALQ44026 |

| KT901807 | ALQ44027 |

| KT901808 | ALQ44028 |

| KT901809 | ALQ44029 |

| KT901810 | ALQ44030 |

| KT901811 | ALQ44031 |

| KT901812 | ALQ44032 |

| KT901813 | ALQ44033 |

| KT901814 | ALQ44034 |

Funding

No funding has been received for the conduct of this study and/or preparation of this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BC

Breast Cancer

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- BRCA2

Breast Cancer type2

- D

Aspartic acid

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- EDTA

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- G

Guanine

- HR

Homologous Recombination

- K

Lysine

- L

Leucine

- mRNA

Messenger Ribonucleic Acid

- N

Asparagine

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- OCCR

Ovarian Cancer Cluster Region

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- RefSeq

Reference Sequence

- RICK

Radiation and Isotope Center in Khartoum

- SIFT

Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- T

Thymine

- TE buffer

Tris-EDTA

- X

Termination stop codon

- Y

Tyrosine

Authors’ contributions

AAE and MASH made substantial contributions to the conception and the design of the study. AAE, MEMMA, MEME, MMAH did the data collection, work in the lab. AAE, HNA, MASH did analysis and interpretation of data. AAE, MAA, MAT, AAA, MNN, MDD, MMA, MIM, HNA, ME, MMAH drafted the manuscript and revised it critically. MASH gave final approval of the version to be published; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethical committee of Sudan Ministry of Health-Khartoum state.

All patients were informed and consented to participate in the study before collecting the samples.

Consent for publication

All patients were consented to publish the results of the study.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Alsmawal A. Elimam, Email: toteil1@hotmail.com

Mohamed Elmogtba Mouaweia Mohamed Aabdein, Email: mogtaba8788@hotmail.com.

Mohamed El-Fatih Moly Eldeen, Email: elfatihnorth@gmail.com.

Mohamed Adel Taha, Email: mohdil23@hotmail.com.

Mohammed N. Nimir, Email: mohammednimir7@gmail.com

Mohamed D. Dafaalla, Email: mdafaallah200@gmail.com

Musaab M. Alfaki, Email: musabnoor946@live.com

Mohamed A. Abdelrahim, Email: mohd1991@gmail.com

Abdelmohaymin A. Abdalla, Email: shawrma214@gmail.com

Musab I. Mohammed, Email: musab.phyta@gmail.com

Mona Ellaithi, Email: mona.ellaithi@gmail.com.

Muzamil Mahdi Abdel Hamid, Email: mahdi@iend.org.

Mohamed Ahmed Salih Hassan, Email: altwoh20002002@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.Acr. Globocan 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Default.aspx. Accessed 12 Jun 2015 .

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(5):E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Susswein LR, Marshall ML, Nusbaum R, Vogel Postula KJ, Weissman SM, Yackowski L, et al. Pathogenic and likely pathogenic variant prevalence among the first 10,000 patients referred for next-generation cancer panel testing. Genet Med. 2016;18(8):823–832. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldenburg RA, Meijers-Heijboer H, Cornelisse CJ, Devilee P. Genetic susceptibility for breast cancer: how many more genes to be found? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007;63(2):125–149. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266(5182):66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wooster R, Bignell G, Lancaster J, Swift S, Seal S, Mangion J, et al. Identification of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA2. Nature. 1995;378(6559):789–792. doi: 10.1038/378789a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, Narod S, Goldgar D, Devilee P, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The breast cancer linkage consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(3):676–689. doi: 10.1086/301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satagopan JM, Offit K, Foulkes W, Robson ME, Wacholder S, Eng CM, et al. The lifetime risks of breast cancer in Ashkenazi Jewish carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2001;10(5):467–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mavaddat N, Peock S, Frost D, Ellis S, Platte R, Fineberg E, et al. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(11):812–822. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petrucelli N, Daly MB, Pal T. BRCA1- and BRCA2-Associated Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer. 1998 Sep 4 [Updated 2016 Dec 15]. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2016. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1247/.

- 11.Campeau PM, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz MD. Hereditary breast cancer: new genetic developments, new therapeutic avenues. Hum Genet. 2008;124(1):31–42. doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, Risch HA, Eyfjord JE, Hopper JL, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72(5):1117–1130. doi: 10.1086/375033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1329–1333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rebbeck TR, Mitra N, Wan F, Sinilnikova OM, Healey S, McGuffog L, et al. Association of type and location of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with risk of breast and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2015;313(13):1347–1361. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavtigian SV, Simard J, Rommens J, Couch F, Shattuck-Eidens D, Neuhausen S, et al. The complete BRCA2 gene and mutations in chromosome 13q-linked kindreds. Nat Genet. 1996;12(3):333–337. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Awadelkarim KD, Aceto G, Veschi S, Elhaj A, Morgano A, Mohamedani AA, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 status in a central Sudanese series of breast cancer patients: interactions with genetic, ethnic and reproductive factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;102(2):189–199. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9303-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elnour AM, Elderdery AY, Mills J, Mohammed BA, Elbietabdelaal D, Mohamed AO, et al. BRCA 1 & 2 mutations in Sudanese secondary school girls with known breast cancer in their families. Int J Health Sci. 2012;6(1):63–71. doi: 10.12816/0005974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubinski J, Phelan CM, Ghadirian P, Lynch HT, Garber J, Weber B, et al. Cancer variation associated with the position of the mutation in the BRCA2 gene. Familial Cancer. 2004;3(1):1–10. doi: 10.1023/B:FAME.0000026816.32400.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratajska M, Brozek I, Senkus-Konefka E, Jassem J, Stepnowska M, Palomba G, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 point mutations and large rearrangements in breast and ovarian cancer families in northern Poland. Oncol Rep. 2008;19(1):263–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakayori M, Kawahara M, Shiraishi K, Nomizu T, Shimada A, Kudo T, et al. Evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of the stop codon (SC) assay for identifying protein-truncating mutations in the BRCA1and BRCA2genes in familial breast cancer. J Hum Genet. 2003;48(3):130–137. doi: 10.1007/s100380300020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren M, Lord CJ, Masabanda J, Griffin D, Ashworth A. Phenotypic effects of heterozygosity for a BRCA2 mutation. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(20):2645–2656. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skoulidis F, Cassidy LD, Pisupati V, Jonasson JG, Bjarnason H, Eyfjord JE, et al. Germline Brca2 heterozygosity promotes Kras(G12D)-driven carcinogenesis in a murine model of familial pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;18(5):499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brinton LA, Figueroa JD, Awuah B, Yarney J, Wiafe S, Wood SN, et al. Breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for prevention. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(3):467–478. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2868-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friebel TM, Domchek SM, Rebbeck TR. Modifiers of cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(6):dju091. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subbarayan PR, Sarkar M, Ardalan B. Isolation of genomic DNA from human whole blood. BioTechniques. 2002;33(6):1231. doi: 10.2144/02336bm10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dufloth RM, Carvalho S, Heinrich JK, Shinzato JY, dos Santos CC, Zeferino LC, et al. Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Brazilian breast cancer patients with positive family history. Sao Paulo Med J. 2005;123(4):192–197. doi: 10.1590/S1516-31802005000400007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.FinchTV 1.4.0 (Geospiza, Inc.; Seattle, WA, USA). http://jblseqdat.bioc.cam.ac.uk/gnmweb/download/soft/FinchTV_1.4/doc/.

- 28.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hall TA. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser. 1999;41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Expasy translate tool. http://web.expasy.org/translate. Accessed 14 Aug 2015.

- 31.Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2013 Jan;Chapter 7:Unit7.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Venselaar H, Te Beek TA, Kuipers RK, Hekkelman ML, Vriend G. Protein structure analysis of mutations causing inheritable diseases. An e-Science approach with life scientist friendly interfaces. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Capriotti E, Fariselli P, Casadio R. I-Mutant2.0: predicting stability changes upon mutation from the protein sequence or structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W306–W310. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods. 2014;11(4):361–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gayther SA, Mangion J, Russell P, Seal S, Barfoot R, Ponder BA, et al. Variation of risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with different germline mutations of the BRCA2 gene. Nat Genet. 1997;15(1):103–105. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson D, Easton D. Breast cancer linkage consortium. Variation in cancer risks, by mutation position, in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68(2):410–419. doi: 10.1086/318181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kote-Jarai Z, Leongamornlert D, Saunders E, Tymrakiewicz M, Castro E, Mahmud N, et al. BRCA2 is a moderate penetrance gene contributing to young-onset prostate cancer: implications for genetic testing in prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(8):1230–1234. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandhu SK, Omlin A, Hylands L, Miranda S, Barber LJ, Riisnaes R, et al. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for the treatment of advanced germline BRCA2 mutant prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(5):1416–1418. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song H, Cicek MS, Dicks E, Harrington P, Ramus SJ, Cunningham JM, Fridley BL, Tyrer JP, Alsop J, Jimenez-Linan M, Gayther SA, Goode EL, Pharoah PD. The contribution of deleterious germline mutations in BRCA1, BRCA2 and the mismatch repair genes to ovarian cancer in the population. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(17):4703–4709. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bork P, Blomberg N, Nilges M. Internal repeats in the BRCA2 protein sequence. Nat Genet. 1996;13(1):22–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carreira A, Hilario J, Amitani I, Baskin RJ, Shivji MK, Venkitaraman AR, et al. The BRC repeats of BRCA2 modulate the DNA-binding selectivity of RAD51. Cell. 2009;136(6):1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carreira A, Kowalczykowski SC. Two classes of BRC repeats in BRCA2 promote RAD51 nucleoprotein filament function by distinct mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(26):10448–10453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106971108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yuan SS, Lee SY, Chen G, Song M, Tomlinson GE, Lee EY. BRCA2 is required for ionizing radiation-induced assembly of Rad51 complex in vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59(15):3547–3551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moynahan ME, Pierce AJ, Jasin M. BRCA2 is required for homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol Cell. 2001;7(2):263–272. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delahaye-Sourdeix M, Anantharaman D, Timofeeva MN, Gaborieau V, Chabrier A, Vallée MP, et al. A rare truncating BRCA2 variant and genetic susceptibility to upper aerodigestive tract cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov,. 'Reference SNP (Refsnp) Cluster Report: Rs4987049** With Pathogenic,Uncertain Significance Allele **'. N.p., 2015. Web. 15 Sept. 2015.

- 48.Gao Q, Adebamowo CA, Fackenthal J, Das S, Sveen L, Falusi AG, et al. Protein truncating BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in African women with pre-menopausal breast cancer. Hum Genet. 2000;107(2):192–194. doi: 10.1007/s004390000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fackenthal JD, Sveen L, Gao Q, Kohlmeir EK, Adebamowo C, Ogundiran TO, et al. Complete allelic analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants in young Nigerian breast cancer patients. J Med Genet. 2005;42(3):276–281. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anwar SL, Haryono SJ, Aryandono T, Datasena IG. Screening of BRCA1/2 mutations using direct sequencing in Indonesian familial breast cancer cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(4):1987–1991. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.4.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toh GT, Kang P, Lee SSW, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 Germline Mutations in Malaysian Women with Early-Onset Breast Cancer without a Family History. Carter DA, ed. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(4):e2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.De Leeneer K, Coene I, Poppe B, De Paepe A, Claes K. Genotyping of frequent BRCA1/2 SNPs with unlabeled probes: a supplement to HRMCA mutation scanning, allowing the strong reduction of sequencing burden. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11(5):415–419. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.090032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hondow HL, Fox SB, Mitchell G, Scott RJ, Beshay V, Wong SQ, et al. A high-throughput protocol for mutation scanning of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gayther SA, Song H, Ramus SJ, Kjaer SK, Whittemore AS, Quaye L, et al. Tagging single nucleotide polymorphisms in cell cycle control genes and susceptibility to invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3027–3035. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(2):123–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eeles RA, Dearnaley DP, Ardern-Jones A, Shearer RJ, Easton DF, Ford D, Edwards S, Dowe A. Familial prostate cancer: the evidence and the cancer research campaign/British prostate group (CRC/BPG) UK familial prostate cancer study. Br J Urol. 1997;79(Suppl 1):8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1997.tb00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van der Merwe NC, Hamel N, Schneider SR, Apffelstaedt JP, Wijnen JT, Foulkes WD. A founder BRCA2 mutation in non-Afrikaner breast cancer patients of the western cape of South Africa. Clin Genet. 2012;81(2):179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schoeman M, Apffelstaedt JP, Baatjes K, Urban M. Implementation of a breast cancer genetic service in South Africa - lessons learned. South African Med J. 2013;103(8):529–533. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.6814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Francies FZ, Wainstein T, De Leeneer K, Cairns A, Murdoch M, Nietz S, et al. BRCA1, BRCA2 and PALB2 mutations and CHEK2 c.1100delC in different south African ethnic groups diagnosed with premenopausal and/or triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:912. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1913-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seymour HJ, Wainstein T, Macaulay S, Haw T, Krause A. Breast cancer in high-risk Afrikaner families: is BRCA founder mutation testing sufficient? S Afr Med J. 2016;106(3):264–267. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i3.10285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Laarabi FZ, Jaouad IC, Ouldim K, Aboussair N, Jalil A, Gueddari BE, et al. Genetic testing and first presymptomatic diagnosis in Moroccan families at high risk for breast/ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett. 2011;2(2):389–393. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tazzite A, Jouhadi H, Nadifi S, Aretini P, Falaschi E, Collavoli A. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations in Moroccan breast/ovarian cancer families: novel mutations and unclassified variants. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(3):687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guaoua S, Ratbi I, Lyahyai J, El Alaoui SC, Laarabi FZ, Sefiani A. Novel nonsense mutation of BRCA2 gene in a Moroccan man with familial breast cancer. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(2):468–471. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i2.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jouhadi H, Tazzite A, Azeddoug H, Naim A, Nadifi S, Benider A. Clinical and pathological features of BRCA1/2 tumors in a sample of high-risk Moroccan breast cancer patients. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:248. doi: 10.1186/s13104-016-2057-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Troudi W, Uhrhammer N, Sibille C, Dahan C, Mahfoudh W, Bouchlaka Souissi C. et al. Contribution of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to breast cancer in Tunisia. J Hum Genet 2007;52(11):915-20. Epub 2007 Oct 9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Fourati A, Louchez MM, Fournier J, Gamoudi A, Rahal K, El May MV, et al. Screening for common mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes: interest in genetic testing of Tunisian families with breast and/or ovarian cancer. Bull Cancer. 2014;101(11):E36–E40. doi: 10.1684/bdc.2014.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Riahi A, Kharrat M, Lariani I, Chaabouni-Bouhamed H. High-resolution melting (HRM) assay for the detection of recurrent BRCA1/BRCA2 germline mutations in Tunisian breast/ovarian cancer families. Familial Cancer. 2014;13(4):603–609. doi: 10.1007/s10689-014-9740-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hadiji-Abbes N, Trifa F, Choura M, Khabir A, Sellami-Boudawara T, Frikha M. A novel BRCA2 in frame deletion in a Tunisian woman with early onset sporadic breast cancer. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2015;63(4–5):185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Riahi A, Kharrat M, Ghourabi ME, Khomsi F, Gamoudi A, Lariani I, et al. Mutation spectrum and prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in patients with familial and early-onset breast/ovarian cancer from Tunisia. Clin Genet. 2015;87(2):155–160. doi: 10.1111/cge.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riahi A, Ghourabi ME, Fourati A, Chaabouni-Bouhamed H. Family history predictors of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation status among Tunisian breast/ovarian cancer families. Breast Cancer. 2017;24(2):238–244. doi: 10.1007/s12282-016-0693-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cherbal F, Bakour R, Adane S, Boualga K, Benais-Pont G, Maillet P. BRCA1 and BRCA2 germline mutations screening in Algerian breast/ovarian cancer families. Dis Markers. 2010;28(6):377–384. doi: 10.1155/2010/585278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cherbal F, Salhi N, Bakour R, Adane S, Boualga K, Maillet P. BRCA1 and BRCA2 unclassified variants and missense polymorphisms in Algerian breast/ovarian cancer families. Dis Markers. 2012;32(6):343–353. doi: 10.1155/2012/234136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Henouda S, Bensalem A, Reggad R, Serrar N, Rouabah L, Pujol P. Contribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Germline mutations to early Algerian breast cancer. Dis Markers. 2016;2016:7869095. doi: 10.1155/2016/7869095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bensam M, Hafez E, Awad D, El-Saadani M, Balbaa M. Detection of new point mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in breast cancer patients. Biochem Genet. 2014;52(1–2):15–28. doi: 10.1007/s10528-013-9623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang J, Fackenthal JD, Zheng Y, Huo D, Hou N, Niu Q, et al. Recurrent BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in breast cancer patients of African ancestry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):889–894. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2136-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fackenthal JD, Zhang J, Zhang B, Zheng Y, Hagos F, Burrill DR, et al. High prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in unselected Nigerian breast cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(5):1114–1123. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data access

The BRCA2 sequence data from this study have been submitted to the NCBI GeneBank under the following accession numbers and protein identifiers:

| Accession number | Protein ID |

| KT901805 | ALQ44025 |

| KT901806 | ALQ44026 |

| KT901807 | ALQ44027 |

| KT901808 | ALQ44028 |

| KT901809 | ALQ44029 |

| KT901810 | ALQ44030 |

| KT901811 | ALQ44031 |

| KT901812 | ALQ44032 |

| KT901813 | ALQ44033 |

| KT901814 | ALQ44034 |