Abstract

T lineage commitment occurs in a discrete, stage-specific manner during thymic ontogeny. Intrathymic precursor transfer experiments and the identification of CD4+8+ double-positive (DP), Vα14Jα18 natural T (iNKT) cells suggest that commitment to this lineage might occur at the DP stage. Nevertheless, this matter remains contentious because others failed to detect Vα14Jα18-positive iNKT cells that are CD4+8+. In resolution to this issue, we demonstrate that retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γ (RORγ)0/0 thymi, which accumulate immature single-positive (ISP) thymocytes that precede the DP stage, do not rearrange Vα14-to-Jα18 gene segments, suggesting that this event occurs at a post-ISP stage. Mixed radiation bone marrow chimeras revealed that RORγ functions in an iNKT cell lineage-specific manner. Further, introgression of a Bcl-xL transgene into RORγ0/0 mice, which promotes survival and permits secondary rearrangements of distal Vα and Jα gene segments at the DP stage, rescues Vα14-to-Jα18 recombination. Similarly, introgression of a rearranged Vα14Jα18 transgene into RORγ0/0 mice results in functional iNKT cells. Thus, our data support the “T cell receptor-instructive (mainstream precursor) model” of iNKT cell lineage specification where Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement, positive selection, and iNKT cell lineage commitment occur at or after the DP stage of ontogeny.

Keywords: RORγ, Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement, lineage specification, T cell ontogeny

Commitment and differentiation to T lineage lymphocytes occur in the thymus gland from a pluripotent lymphocyte progenitor. The T lineage consists predominantly of αβ T cells and a minor population of γδ cells. Amongst the αβ T cells are the conventional CD4+8– and CD4–8+ lymphocytes as well as several minor subsets, including CD4+25+ Treg and NK1.1+ natural T cells. Lineage decision (i.e., the decision to become γδ or αβ) occurs early, whereas commitment to CD4+8– and CD4–8+ lineages, which are specified by interactions with antigen-presenting molecules, occurs late in thymic ontogeny. These cell-fate specifications during thymic ontogeny of T lymphocytes depend on specific environmental cues, which signal heritable activation and repression of genes.

Natural T cells comprise a heterogeneous subset amongst which Vα14Jα18 T (iNKT) lymphocytes predominate. They are CD1d-restricted, innate-like T lymphocytes that express a restricted T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire, which consists of the invariant Vα14Jα18 α-chain that predominantly pairs with the Vβ8.2 β-chain (1). iNKT cell function, albeit elusive, appears to be immunoregulatory in nature (2, 3). Its ontogeny proceeds through the very same early stages (CD3–4–8– triple-negative, TN1–4) as do the developing conventional T lymphocytes (4–9). Although it is contentious at which stage commitment to iNKT cell lineage occurs (discussed below), positive selection of this T cell subset relies on the interaction of precursor cells with CD1d1 expressed by CD4+8+ double-positive (DP) thymocytes (10–13). Immature iNKT cells express their TCR and undergo maturation-dependent expression of NK1.1 and DX5, yielding two immediate precursors (DX5–NK1.1– and DX5+NK1.1–) of mature (DX5+NK1.1+ and DX5–NK1.1+) iNKT cells (5–7).

TCR Vα and Jα gene segments undergo ordered primary and secondary recombination events during immature CD8 single-positive (ISP) and DP stage, with proximal segments rearranging before the distal ones (14). Initiation of TCR rearrangement is a tightly regulated process and is kept under the control of two cis-acting elements, the T early α promoter (15, 16) and the TCRα enhancer (17). Selection-induced programmed cell death of TCR-positive, DP thymocytes expressing the proximal Vα and Jα recombinants, however, limits the progression of rearrangements along the Jα locus and constricts the repertoire of positively selected T cells in RORγ0/0 thymocytes (14).

Retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γ (RORγ) and its thymus-specific isoform (RORγt), which differ only in their 5′ exons, owing to their expression from distinct promoters, are critical for thymocyte development (18, 19). RORγ is expressed at low levels in ISP cells but primarily in immature DP thymocytes (14, 16, 20). It binds to the T early α promoter and is predicted to regulate TCRα gene rearrangement (16). RORγ0/0 mice exhibit ≈9-fold expansion of ISP cells, as well as a reduction in DP (60–80%) and CD4+8– and CD4–8+ single-positive (>90%) thymocytes (14, 18). RORγ regulates the survival window of DP thymocytes through induction of antiapoptotic Bcl-xL and allows rearrangement through more distal 5′ Vα-to-3′ Jα segments (14, 18).

Numerous studies using various mutant mouse models have demonstrated unique requirements for the development of iNKT cells when compared with conventional T lymphocytes, suggesting that they may constitute a distinct T cell lineage (8, 21–27). Although much has been learned regarding the factors that drive differentiation, the developmental origin of this cell lineage remains less clearly defined. Purified, genetically tagged CD3– DP thymocytes from either WT or CD1d-deficient mice, when injected intrathymically into W T hosts, beget Vα14Jα18+CD4+ and CD4–8– double-negative iNKT cells. Further, CD1 tetramer [tetrameric, α-galactosylceramide (αGalCer)-loaded CD1d1]-positive, DP iNKT cells were identified in this study (4). Our studies of thymocyte-specific NF-κB signaling-deficient mice revealed a CD24HIGH (HSA) CD1 tetramer-positive thymocyte, which also expressed Nur77, a marker for negative selection (23). These data suggest that iNKT cells may be derived from the DP compartment but could also reflect the presence of an already precommitted precursor in the sorted CD3– DP population. Nevertheless, other studies have identified CD4+ thymocytes as the first CD1 tetramer-positive cells and failed to identify DP iNKT cells (5, 6). Thus, whether iNKT cells are derived from a distinct precursor or are selected from a common T cell precursor pool still remains unclear. Consequently, we have sought to resolve this issue by using RORγ0/0 mice as a model.

We hypothesized that the thymocyte precursor in which Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement occurs would specify the iNKT cell lineage. Our data are consistent with the “TCR-instructive (mainstream precursor) model” (reviewed in ref. 28) of iNKT cell development in which Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement, and hence commitment to the iNKT cell lineage, occurs at the DP stage.

Experimental Procedures

Mice. C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. B6-Vα14tg (29), B6-Jα180/0 (30), B6.129-RORγ0/0, B6-RORγ0/0; (18), and B6-IκBαΔNtg (23, 31) mice were generously provided by A. Bendelac (University of Chicago, Chicago), M. Taniguchi (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan), D. R. Littman (New York University, New York), and M. R. Boothby (Vanderbilt University), respectively. B6.129-CD1d10/0 mice are described in ref. 12. B6.129-RORγ0/0;Vα14tg mice were generated by introgressing the rearranged Vα14Jα18 transgene into the knockout animal through breeding. All mice were bred and maintained in compliance with Vanderbilt's Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee regulations.

(18), and B6-IκBαΔNtg (23, 31) mice were generously provided by A. Bendelac (University of Chicago, Chicago), M. Taniguchi (Chiba University, Chiba, Japan), D. R. Littman (New York University, New York), and M. R. Boothby (Vanderbilt University), respectively. B6.129-CD1d10/0 mice are described in ref. 12. B6.129-RORγ0/0;Vα14tg mice were generated by introgressing the rearranged Vα14Jα18 transgene into the knockout animal through breeding. All mice were bred and maintained in compliance with Vanderbilt's Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee regulations.

Antibodies and Reagents. All antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences. αGalCer was generously provided by Kirin Brewery (Gunma, Japan). Preparation and use of CD1 tetramer are described in ref. 32.

Flow Cytometry. Splenocytes of individual, age-matched (3–7 weeks old) mice were stained for four-color flow cytometric analysis by using the following antibodies: anti-B220-FITC, anti-CD8α-FITC, anti-CD4-PE, anti-CD3ε-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-CD1d (1B1)-biotin, streptavidin-allophycocyanin, and CD1 tetramer-allophycocyanin. iNKT cells were analyzed within electronically gated B220– splenic and hepatic or CD8α– thymic populations. Flow cytometry was performed with a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson), and the data were analyzed by using flowjo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

ELISA. Each mouse was injected i.p. with 5 μgof αGalCer or with vehicle (0.1% Tween 20 in PBS) as the control. Two hours later, serum was collected, and IL-2 and IL-4 responses were monitored by ELISA as described in refs. 24 and 32.

Generation of Radiation Bone Marrow (BM) Chimeras. Recipient mice were irradiated twice with 500 rads from a Cs source 4 hr apart, rested for 6 hr, and transfused i.v. with 2–2.5 × 107 donor BM cells in PBS. Mice were maintained under antibiotic treatment (sulfamethoxasole and trimethoprim oral suspension, Alpharma, Baltimore) from 2 days before transfer until 2 weeks after transfer. Animals were kept under sterile conditions and analyzed 4–8 weeks posttransplantation.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR. Total thymic RNA was extracted by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription (RT) was performed on 1 μg of RNA by using the Omniscript RT Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative PCR was conducted by using 1 μl of cDNA resulting from the above RT reaction. TaqMan MGB (Applied Biosystems) forward Vα14 (5′-CACTGCCACCTACATCTGTGT-3′), reverse Jα18 (5′-AGTCCCAGCTCCAAAATGCA-3′), and Vα14Jα18 reporter (5′-CCTAAGGCTGAAC-CTC-3′) primers, as well as the proprietary β-actin primers (Applied Biosystems assay Mn00607939_s1), were used. Data were collected on a Stratagene Mx3000P thermocycler. Cycle threshold values were obtained by using Stratagene mx3000p software. Data are represented as percent Vα14Jα18 expression levels in each sample relative to β-actin transcripts detected in the same sample.

RT-PCR. RT was performed on total RNA as described above. PCR was performed by using the cDNA template resulting from the above RT reaction and forward (F) and reverse (R) primers: Vα14F (5′-TGGGAGATACTCAGCAACTCTGG-3′), Jα18R (5′-CAGGTATGACAATCGCTGAGTCC-3′), Vα3F (5′-CCCAGTGGTTCAAGGAGTGA-3′), Vα8F (5′-TCACAGACAACAAG-AGGACC-3′), CαR (5′-TGGCGTTGGTCTCTTTGAAG-3′), β-actinF (5′-AGAGGGAAATC-GTGCGTGAC-3′), and β-actinR (5′-CAATAGTGATGACCTGGCCGT-3′). PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Results and Discussion

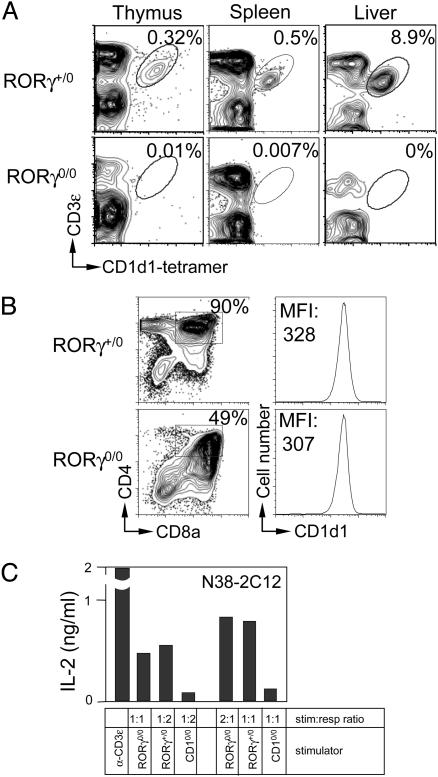

RORγ Deficiency Impairs iNKT Cell Ontogeny. RORγ plays an important role in conventional T cell development (14, 18). Its role in iNKT cell ontogeny hitherto remains undefined. Lineage-specific phenotyping (23) using CD1 tetramer revealed that RORγ0/0 mice do not contain any detectable iNKT cells in the thymus, spleen, and liver (Fig. 1A). This deficit could be a consequence of altered CD1d1 expression on DP RORγ0/0 thymocytes, thereby disrupting positive selection of iNKT cells. Our analysis of CD1d1 expression (Fig. 1B) and function (Fig. 1C) indicates that these aspects are intact in RORγ0/0 mice. Note that the RORγ0/0 thymus, as compared with the WT thymus, contains only ≈40–50% DP thymocytes (refs. 14 and 18 and Fig. 1B) and, hence, requires twice as many cells to activate iNKT hybridomas (Fig. 1C). Because RORγ0/0 mice express functional CD1d1 molecules, we conclude that RORγ deficiency impairs iNKT cell development by a mechanism distinct from defective positive selection of this lineage.

Fig. 1.

RORγ-deficient mice lack iNKT cells. (A) Thymic, splenic, and liver RORγ+/0 and RORγ0/0 iNKT cells were identified by using CD3ε-specific mAb in conjunction with CD1 tetramer and analyzed by flow cytometry. CD8αLOW thymocytes as well as B220LOW splenic and hepatic leukocytes were electronically gated, and CD3ε+CD1 tetramer-positive cells were identified. Numbers within plots refer to the percentage of iNKT cells among total leukocytes. The data represent at least three independent experiments. (B) Thymic RORγ+/0 and RORγ0/0 cells were reacted with CD1d-, CD4-, and CD8α-specific mAbs and analyzed by flow cytometry. DP cells were gated (Left), and the level of CD1d1 expression was analyzed (Right). Numbers within plots refer to the percentage of DP thymocytes and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD1d1. (C) Freshly isolated RORγ+/0 and RORγ0/0 thymocytes were incubated with N38-2C12 iNKT hybridoma. After 12–15 hr, IL-2 secreted into the coculture medium was monitored as a function of iNKT hybridoma activation by using ELISA. Plate-bound anti-CD3ε mAb and CD1d0/0 stimulators were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Data in B and C are representative of two independent experiments. stim:resp, simulator-to-responder ratio.

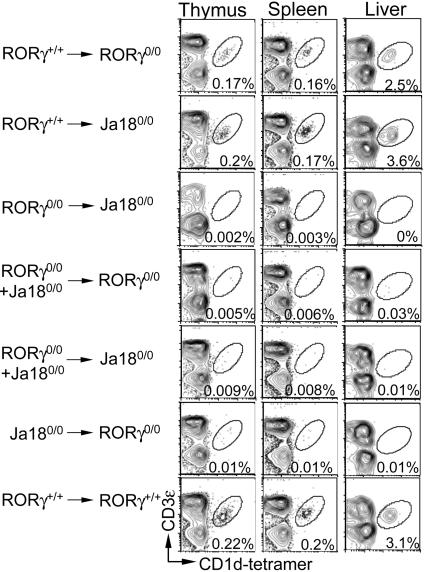

RORγ Plays a Cell-Autonomous Role in iNKT Cell Ontogeny. To determine the mechanism by which RORγ regulates iNKT cell ontogeny, we prepared a series of reciprocal BM chimeras by using RORγ0/0 and Jα180/0 mice (which develop conventional T cells but do not develop iNKT cells). Because RORγ+/+ → RORγ0/0 (Fig. 2, first row) and RORγ+/+ → Jα180/0 (Fig. 2, second row) radiation BM chimeras reconstitute iNKT cell ontogeny, we concluded that RORγ must play a haematopoietic cell-intrinsic role during development. In support of this conclusion, RORγ0/0 → Jα180/0 (Fig. 2, third row) BM chimeras did not develop iNKT cells. To determine whether RORγ plays an iNKT cell or T lymphocyte-autonomous role, we generated mixed RORγ0/0 + Jα180/0 → RORγ0/0 (Fig. 2, fourth row) and RORγ0/0 + Jα180/0 → Jα180/0 (Fig. 2, fifth row) BM chimeras. In this system, Jα180/0 BM chimeras (which develop RORγ-competent T cells but do not develop iNKT cells) should provide any T cell-derived, RORγ-induced factor(s). We found that the mixed BM chimeras do not reconstitute iNKT cell development (Fig. 2). Similar data were obtained when B6-IκBαΔNtg mice [which, akin to Jα180/0 mice, do not develop iNKT cells (23)] were used as donors for mixed radiation BM chimeras generated in RORγ0/0 animals (data not shown). Therefore, we conclude that RORγ plays an iNKT cell-autonomous role in this ontogenetic process.

Fig. 2.

RORγ plays a cell-intrinsic role during iNKT cell ontogeny. Radiation BM chimeras were generated as described in Materials and Methods. Thymii, spleens, and livers were collected 4 weeks posttransplantation (in the data shown) and analyzed as described in the legend of Fig. 1 A. Numbers within plots refer to percentage of iNKT cells among the total leukocytes. In all experiments, Jα180/0 → RORγ0/0 and RORγ+/+ → RORγ+/+ radiation BM chimeras were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Data are representative of three similar experiments.

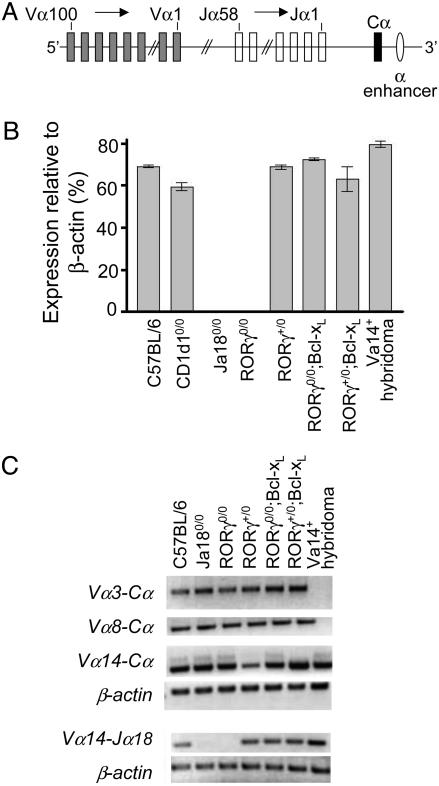

RORγ Deficiency Precludes Vα14-to-Jα18 Gene Rearrangement. RORγ0/0 mice rearrange only the proximal, not the distal, Vα and Jα gene segments because of premature death of DP thymocytes (14). Whether RORγ0/0 thymocytes recombine Vα14-to-Jα18 gene segments hitherto remains unknown. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis using specific primers for the Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement found in iNKT cells revealed that RORγ0/0 thymocytes, akin to Jα180/0 thymocytes, do not rearrange Vα14 and Jα18 gene segments (Fig. 3B). To exclude the possibility that the Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement occurs in RORγ0/0 thymocytes but is undetectable because the lineage is not further expanded by positive selection, we used CD1d10/0 thymocytes as a sensitivity control for the assay to detect preexisting but unselected Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangements. The results using whole CD1d10/0 thymus (whose DP thymocyte content is >80%) show that Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement is detectable in CD1d10/0 thymocytes at levels similar to WT (Fig. 3B), which is consistent with a published report (4). Thus, the Vα14Jα18 iNKT cell precursor is less likely to exist in RORγ0/0 thymocytes. Nevertheless, although Vα14, as well as Vα3 and Vα8, segments recombine with perhaps more proximal Jα segments (Fig. 3C), the Vα14 segment does not recombine with the more distal Jα18 element (Fig. 3B). This finding is consistent with an earlier report that demonstrated that the major limitation to successful Vα-to-Jα rearrangement in RORγ0/0 mice is not the Vα element but the proximity of a particular Jα segment to Vα elements (14) (see Fig. 3A for a schematic rendition of the Vα locus). This study, in which recombination as far upstream as the Vα19 locus to all Jα segments was analyzed, revealed that rearrangement occurred as far as the Jα30 segment (ref. 14 and Y.-W. He, personal communication). Note that Jα18 is farther away from the Vα locus than is Jα30 (Fig. 3A). Thus, we conclude that RORγ deficiency precludes Vα14-to-Jα18 gene rearrangement and impairs iNKT cell ontogeny before lineage specification.

Fig. 3.

Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement occurs within DP thymocytes. (A) Schematic rendition of the germ-line organization of mouse Vα locus. Note that the Vα and Jα segments are numbered 5′ to 3′ in a descending order (adapted from ref. 46). (B) Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement was assessed by quantitative real-time PCR by using TaqMan MGB primers and probes as described in Materials and Methods. Positive and negative controls were a Vα14 iNKT hybridoma DN32.D3 and Jα180/0 thymocytes, respectively. β-actin was used as an endogenous control for each sample. Error bars represent standard errors of data collected from three independent experiments. (C) Conventional RT-PCR was used to assess the indicated Vα-to-Cα and Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangements. β-actin was used as the positive control. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

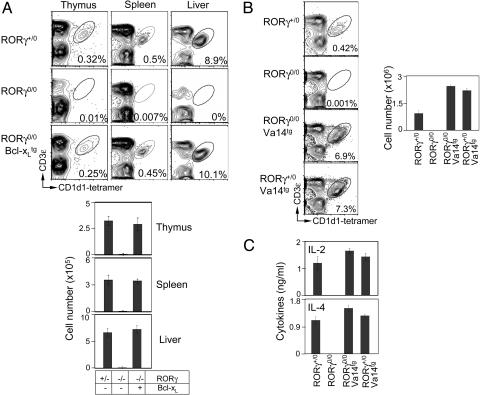

Vα14-to-Jα18 Gene Rearrangement Occurs at the DP Stage and Specifies the iNKT Cell Lineage. Previous studies have shown that enforced expression of the Bcl-xL transgene in RORγ0/0 (RORγ0/0;Bcl-xLtg) mice promotes survival of TCR-positive DP thymocytes, restoring them to numbers equivalent to those in RORγ+/+ mice (14, 18). The resulting RORγ0/0;Bcl-xLtg thymocytes have rearranged Vα elements to the most distal Jα segments in addition to the proximal ones (14). We found that RORγ0/0;Bcl-xLtg thymocytes recombine Vα14-to-Jα18 gene segments (Fig. 3B). Consequently, iNKT cell ontogeny is also restored in RORγ0/0;Bcl-xLtg mice (Fig. 4A). These data suggest an essential role of RORγ in the survival of the cellular substrate in which Vα14-to-Jα18 gene recombination occurs.

Fig. 4.

Introgression of Bcl-xL and the Vα14Jα18 transgene into RORγ0/0 mice rescues iNKT cell development. (A and B) RORγ+/0, RORγ0/0, and RORγ0/0;Bcl-xLtg (A) and RORγ+/0;Vα14tg and RORγ0/0;Vα14tg (B) iNKT cells were analyzed as described in the legend of Fig. 1 A. Absolute numbers of thymic iNKT cells (B Right) were calculated from total leukocyte number and percentage of gated CD3ε+CD1 tetramer-positive cells (B Left). Vα14tg (29) thymii are lymphopenic; therefore, RORγ0/0;Vα14tg mice have up to 3- to 5-fold lower thymic cellularity when compared with RORγ+/0 control. (C) Serum cytokine response of RORγ+/0, RORγ0/0, RORγ0/0;Vα14tg, and RORγ+/0;Vα14tg mice to in vivo activation of iNKT cells was measured by ELISA after 2 hr of αGalCer or vehicle administration. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

To affirm the conclusion that impaired iNKT cell ontogeny in RORγ0/0 mice is owed exclusively to the lack of Vα14-to-Jα18 gene rearrangement, we introgressed the rearranged Vα14Jα18 transgene into RORγ0/0 (RORγ0/0;Vα14tg) mice. Akin to RORγ0/0;Bcl-xLtg mice but unlike RORγ0/0 animals, RORγ0/0;Vα14tg mice develop functional iNKT cells (Fig. 4 B and C). Based on these findings and the fact that RORγ is a highly DP stage-specific transcription factor, we propose that Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement and iNKT cell lineage specification are DP stage-specific events.

Concluding Remarks

It is currently thought that the first iNKT cells to emerge in the thymus are CD4+ and CD24LOW (5, 6). That conclusion notwithstanding, intrathymic transfer of CD3ε–CD4+8+ DP thymocytes from WT or CD1d10/0 mice into CD1d1+/+ recipients yields iNKT cells (4). We previously identified a putative CD1 tetramer-positive thymic precursor that expresses CD24 in mice severely deficient in thymocyte-specific NF-κB signaling (23). These latter studies suggest that commitment to the iNKT cell lineage might occur at the DP stage. Nevertheless, interpretation of these findings is complicated by inherent limitations of adoptive cell transfer and immunophenotyping experiments. The genetic system described here overcomes the limitations of previous studies, and the data support the hypothesis that the iNKT cell precursor emerges from CD4+8+ DP thymocytes. Thus, our findings are consistent with the “TCR-instructive (mainstream precursor) model” (reviewed in ref. 28) in which commitment to the CD1d1-restricted iNKT cell lineage, akin to MHC class II-restricted CD4+8– and MHC class I-restricted CD4–8+ T lymphocyte lineages, occurs at or after the DP stage through positive selection by specific self-ligands.

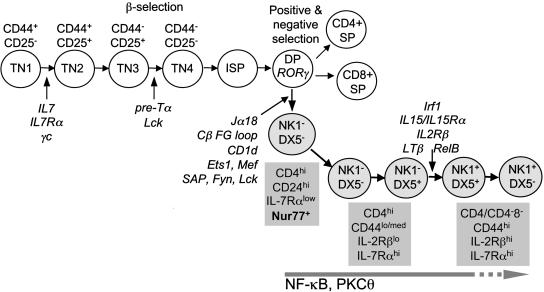

Early steps in the ontogeny of iNKT lymphocytes and conventional T cells are common to both lineages (Fig. 5). The common progression of the two lineages through early ontogenesis is also reflected in similar-to-identical signaling requirements (IL-7Rα, Jak3, and common γ-chain) for the development of their precursors before Tcrα rearrangement (reviewed in refs. 4 and 27). Our data further suggest that Vα14-to-Jα18 rearrangement represents part of a general rearrangement process along the Tcrα locus that is independent of precommitment to the iNKT cell lineage itself. Nevertheless, it is after Vα14 and Jα18 rearrangement and Vα14Jα18 TCR expression on the cell surface that the iNKT cell lineage begins to acquire unique TCR signaling features, which are clearly distinct from the ones acquired by conventional T cells. Fyn, which is required for iNKT cell ontogeny, is dispensable for conventional T cell development. Further, Fyn appears to be the first iNKT cell-specific signal that acts in a distinct manner within this lineage during thymic development (33–35). RORγ and Fyn perhaps act on the same precursor, which we predict to be the DP thymocytes, based on previous data (33–35) and data presented here.

Fig. 5.

A putative ontogenetic pathway for iNKT cells. Early steps in the ontogeny of iNKT lymphocytes and conventional T cells are common to both lineages. The ontogenetic programming of the unique features of iNKT cell function occurs at the CD4+8+ DP stage and begins with the rearrangement of the Vα14Jα18 TCR α-chain and after its interaction with the positively selecting ligand CD1d-self lipid complex. Stage-specific iNKT cell markers (gray boxes) and lineage-specific differentiation signals are indicated. Several iNKT cell markers, e.g., CD4, CD44, CD122 (IL-2Rβ), CD127 (IL-7Rα), and CD161 (NK1.1), indicated in gray boxes, as well as CD5, CD24 (HSA), DX5, and Ly49A/D and C/I (data not shown), are developmentally regulated.

We propose that the ontogenetic programming of the unique features of iNKT cell function occurs at the stage that begins with the rearrangement of the Vα14Jα18 TCR α-chain and after its interaction with the positively selecting ligand, CD1d-self lipid complex (Fig. 5). The distinct requirement for IL-15/IL-15 receptor (36–38), lymphotoxin-β (39), Fyn (33–35), SAP (40–42), and PKCθ (24) signaling, as well as Ets (43), T-bet (26), AP-1 (44), and NF-κB (21–23) transcription factors for iNKT but not for conventional T lymphocyte ontogeny, underscores the impact of Vα14Jα18 TCR/CD1d interaction in this process. Our previous data have suggested that the Vα14Jα18 iNKT cell receptor is organized and/or interfaces its ligand(s) in a manner distinct from the αβ TCR of conventional T lymphocytes (45). Thus, the identification of the earliest precursor that begets the iNKT cell lineage will allow the dissection of the unique cellular, biochemical, and molecular programming of this T lymphocyte subset.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. A. Bendelac, M. R. Boothby, D. R. Littman, and M. Taniguchi for genetically altered mice; Drs. A. Bendelac and K. Hayakawa (Fox Chase Cancer Center, Cheltenham, PA) for iNKT cell hybridomas; Kirin Brewery for generous supplies of αGalCer; Y. A. Oh and K. Richter for help with RNA preparation and RT-PCR; and A. J. Joyce and M. McReynolds for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI49460 (to M. R. Boothby); AI050953, NS044044, and HL068744 (to L.V.K.); and AI042284 (to S.J.); and grants from the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (to S.J.) and the Human Frontiers in Science Program (to S.J.).

Author contributions: J.S.B. and S.J. designed research; J.S.B. and T.H. performed research; J.S.B. and T.H. analyzed data; A.K.S. and L.V.K. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; S.J. wrote the paper; J.S.B. revised the manuscript and wrote the first draft response to the critiques; L.V.K. edited the manuscript, the revised manuscript, and the draft of the response to the critiques; and S.J. revised/edited the manuscript and wrote/edited the response to the critiques.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: RORγ, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptor γ; DP, double positive; iNKT, Vα14Jα18 natural T; TCR, T cell receptor; αGalCer, α-galactosylceramide; BM, bone marrow; RT, reverse transcription.

Note Added in Proof. During the review of this manuscript, it came to our attention that T. Egawa et al. (47), using an identical and complementary system, reached a conclusion similar to the one described here regarding the origin and lineage commitment of iNKT cells.

References

- 1.Bendelac, A., Bonneville, M. & Kearney, J. F. (2001) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1, 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Kaer, L. (2004) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5, 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilson, S. B. & Delovitch, T. L. (2003) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3, 211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gapin, L., Matsuda, J. L., Surh, C. D. & Kronenberg, M. (2001) Nat. Immunol. 2, 971–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benlagha, K., Kyin, T., Beavis, A., Teyton, L. & Bendelac, A. (2002) Science 296, 553–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pellicci, D. G., Hammond, K. J., Uldrich, A. P., Baxter, A. G., Smyth, M. J. & Godfrey, D. I. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 195, 835–844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gadue, P. & Stein, P. L. (2002) J. Immunol. 169, 2397–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kronenberg, M. & Gapin, L. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 557–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDonald, H. R. (2002) Science 296, 481–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendelac, A. (1995) J. Exp. Med. 182, 2091–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smiley, S. T., Kaplan, M. H. & Grusby, M. J. (1997) Science 275, 977–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendiratta, S. K., Martin, W. D., Hong, S., Boesteanu, A., Joyce, S. & Van Kaer, L. (1997) Immunity 6, 469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, Y.-H., Chiu, N. M., Mandal, M., Wang, N. & Wang, C.-R. (1997) Immunity 6, 459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo, J., Hawwari, A., Li, H., Sun, Z., Mahanta, S. K., Littman, D. R., Krangel, M. S. & He, Y. W. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson, A., de Villartay, J. P. & MacDonald, H. R. (1996) Immunity 4, 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villey, I., de Chasseval, R. & de Villartay, J. P. (1999) Eur. J. Immunol. 29, 4072–4080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sleckman, B. P., Bardon, C. G., Ferrini, R., Davidson, L. & Alt, F. W. (1997) Immunity 7, 505–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun, Z., Unutmaz, D., Zou, Y. R., Sunshine, M. J., Pierani, A., Brenner-Morton, S., Mebius, R. E. & Littman, D. R. (2000) Science 288, 2369–2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winoto, A. & Littman, D. R. (2002) Cell 109, S57–S66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He, Y. W., Deftos, M. L., Ojala, E. W. & Bevan, M. J. (1998) Immunity 9, 797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elewaut, D., Shaikh, R. B., Hammond, K. J., De Winter, H., Leishman, A. J., Sidobre, S., Turovskaya, O., Prigozy, T. I., Ma, L., Banks, T. A., et al. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197, 1623–1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sivakumar, V., Hammond, K. J., Howells, N., Pfeffer, K. & Weih, F. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197, 1613–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanic, A. K., Bezbradica, J. S., Park, J. J., Matsuki, N., Mora, A. L., Van Kaer, L., Boothby, M. R. & Joyce, S. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 2265–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanic, A. K., Bezbradica, J. S., Park, J. J., Van Kaer, L., Boothby, M. R. & Joyce, S. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 4667–4671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt-Supprian, M., Tian, J., Grant, E. P., Pasparakis, M., Maehr, R., Ovaa, H., Ploegh, H. L., Coyle, A. J. & Rajewsky, K. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 4566–4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Townsend, M. J., Weinmann, A. S., Matsuda, J. L., Salomon, R., Farnham, P. J., Biron, C. A., Gapin, L. & Glimcher, L. H. (2004) Immunity 20, 477–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanic, A. K., Park, J. J. & Joyce, S. (2003) Immunology 109, 171–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald, H. R. (2002) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14, 250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendelac, A., Hunziker, R. D. & Lantz, O. (1996) J. Exp. Med. 184, 1285–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawano, T., Cui, J., Koezuka, Y., Toura, I., Kaneko, Y., Motoki, K., Ueno, H., Nakagawa, R., Sato, H., Kondo, E., et al. (1997) Science 278, 1626–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boothby, M. R., Mora, A. L., Scherer, D. C., Brockman, J. A. & Ballard, D. W. (1997) J. Exp. Med. 185, 1897–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsuki, N., Stanic, A. K., Embers, M. E., Van Kaer, L., Morel, L. & Joyce, S. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 5429–5437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eberl, G., Lowin-Kropf, B. & MacDonald, H. R. (1999) J. Immunol. 163, 4091–4094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gadue, P., Morton, N. & Stein, P. L. (1999) J. Exp. Med. 190, 1189–1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gadue, P., Yin, L., Jain, S. & Stein, P. L. (2004) J. Immunol. 172, 6093–6100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lodolce, J. P., Boone, D. L., Chai, S., Swain, R. E., Dassopoulos, T., Trettin, S. & Ma, A. (1998) Immunity 9, 669–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennedy, M. K., Glaccum, M., Brown, S. N., Butz, E. A., Viney, J. L., Embers, M., Matsuki, N., Charrier, K., Sedger, L., Willis, C. R., et al. (2000) J. Exp. Med. 191, 771–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsuda, J. L., Gapin, L., Sidobre, S., Kieper, W. C., Tan, J. T., Ceredig, R., Surh, C. D. & Kronenberg, M. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 966–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elewaut, D., Brossay, L., Santee, S. M., Naidenko, O. V., Burdin, N., De Winter, H., Matsuda, J., Ware, C. F., Cheroutre, H. & Kronenberg, M. (2000) J. Immunol. 165, 671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nichols, K. E., Hom, J., Gong, S. Y., Ganguly, A., Ma, C. S., Cannons, J. L., Tangye, S. G., Schwartzberg, P. L., Koretzky, G. A. & Stein, P. L. (2005) Nat. Med. 11, 340–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pasquier, B., Yin, L., Fondaneche, M. C., Relouzat, F., Bloch-Queyrat, C., Lambert, N., Fischer, A., de Saint-Basile, G. & Latour, S. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201, 695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chung, B., Aoukaty, A., Dutz, J., Terhorst, C. & Tan, R. (2005) J. Immunol. 174, 3153–3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walunas, T. L., Wang, B., Wang, C. R. & Leiden, J. M. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 2857–2860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams, K. L., Zullo, A. J., Kaplan, M. H., Brutkiewicz, R. R., Deppmann, C. D., Vinson, C. & Taparowsky, E. J. (2003) J. Immunol. 170, 2417–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stanic, A. K., Shashidharamurthy, R., Bezbradica, J. S., Matsuki, N., Yoshimura, Y., Miyake, S., Choi, E. Y., Schell, T. D., Van Kaer, L., Tevethia, S. S., et al. (2003) J. Immunol. 171, 4539–4551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang, C. & Kanagawa, O. (2001) J. Immunol. 166, 2597–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Egawa, T., Eberl, G., Taniuchi, I., Benlagha, K., Giessmann, F., Hennighausen, L., Bendelac, A. & Littman, D. R. (2005) Immunity, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]