Summary

Background

Interstitial lung disease is common in patients with sickle cell anemia (SCA). Fibrocytes are circulating cells implicated in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis and airway remodeling in asthma. In this study, we tested the hypotheses that fibrocyte levels are: (1) increased in children with SCA compared to healthy controls, and (2) associated with pulmonary disease.

Procedure

Cross-sectional cohort study of children with SCA who participated in the Sleep Asthma Cohort Study.

Results

Fibrocyte levels were obtained from 45 children with SCA and 24 controls. Mean age of SCA cases was 14 years and 53% were female. In children with SCA, levels of circulating fibrocytes were greater than controls (P < 0.01). The fibrocytes expressed a hierarchy of chemokine receptors, with CXCR4 expressed on the majority of cells and CCR2 and CCR7 expressed on a smaller subset. Almost half of fibrocytes demonstrated α-smooth muscle actin activation. Increased fibrocyte levels were associated with a higher reticulocyte count (P = 0.03) and older age (P = 0.048) in children with SCA. However, children with increased levels of fibrocytes were not more likely to have asthma or lower percent predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 sec/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) or FEV1 than those with lower fibrocyte levels.

Conclusions

Higher levels of fibrocytes in children with SCA compared to controls may be due to hemolysis. Longitudinal studies may be able to better assess the relationship between fibrocyte level and pulmonary dysfunction.

Keywords: sickle cell anemia, fibrocytes, asthma

INTRODUCTION

Interstitial lung disease is a common cause of death in adults with sickle cell anemia (SCA).1,2 Although the pathogenesis is not well defined, interstitial lung disease may be the result of a progressive lung disease that begins in childhood.3 Asthma is present in 30% of children with SCA and an even greater percent demonstrate an obstructive pattern on pulmonary function testing.4,5 Children with SCA also show a progressive decline in lung function over time.3,6 In contrast to children, adults with SCA typically demonstrate a restrictive pattern on pulmonary function testing, in part secondary to pulmonary fibrosis.7,8 The contribution of obstructive lung disease in childhood to restrictive lung disease in adulthood among patients with SCA is not known. However, airway remodeling and a decline in pulmonary function are known to occur in some patients with obstructive lung disease in the general population.9

Dysregulated repair of injured tissue causes remodeling of the airway, interstitial space, and vasculature in fibrotic lung diseases.10,11 Although resident fibroblasts and myofibroblasts contribute to this process, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells, termed fibrocytes, have also been implicated in lung fibrosis.12,13 Fibrocytes express chemokine receptors, including CXCR4, CCR2, and CCR7 that allow them to migrate to damaged organs along chemokine gradients, where they differentiate into fibroblasts and myofibroblasts and contribute to scarring.14,15 Levels of circulating fibrocytes have been associated with airway remodeling in asthma and pulmonary fibrosis in SCA.12,13 In patients with asthma, levels of circulating fibrocytes are associated with decline in forced expiratory volume in 1 sec (FEV1).12 In the NY1DD mouse model of SCA, fibrocyte levels were increased compared to controls and expressed an activated phenotype.13 The interruption of fibrocyte migration to the lung decreased lung collagen content and improved lung compliance.13 Similar to the sickle cell mice, levels of circulating fibrocytes were increased and more likely to express an activated phenotype in adult patients with SCA compared to controls.13

In this prospective study of children with SCA, we extend the findings in our previous study of adults and examine the potential association between level of circulating fibrocytes and pulmonary disease. We tested the hypotheses that fibrocyte levels are: (1) increased in children with SCA compared to healthy controls, and (2) associated with pulmonary disease.

METHODS

Study Design

Children between 4 and 20 years of age with HbSS or HbSβ-thalassemia0 were enrolled in St. Louis, Missouri, as part of the Sleep and Asthma Cohort Study. Controls were African American children without SCA, asthma, or other lung disease. The Sleep Asthma Cohort Study was a prospective, observational cohort study funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute whose primary aim was to evaluate the contribution of abnormal lung function and sleep abnormalities to SCA-related morbidity. Institutional review board approval was obtained. At time of enrollment, informed consent was obtained in writing from parents, and children assented or were consented according to institutional policies.

Data collection included questionnaires, pulmonary function tests, and peripheral blood tests. Pulmonary function testing was performed by Sleep Asthma Cohort-certified technicians, according to American Thoracic Society guidelines, with procedures adopted from the Child Asthma Research and Education Network.16 In this study, asthma was defined as an answer of “yes” to the following question at the time of study consent: “Has a doctor ever said that the participant has asthma?”

Circulating fibrocytes were identified by co-expression of the leukocyte marker CD45 and the fibroblast marker collagen I on quantitative FACS analysis as previously described.17,18 Blood samples from children with SCA were collected and shipped overnight at 4°C to the laboratory at the University of Virginia.

Statistical Analysis

Fibrocyte distribution was skewed, with a long right tail. To account for the nonnormal distribution, SCA subjects were divided into two categories, above and below the Tukey inner fence, which is data value of the third quartile plus 1.5 times the inter-quartile range of fibrocyte values. This cutoff value in children with SCA exceeded all values in control subjects. Student t-test and Mann-Whitney U were used to determine the association between fibrocyte groups and continuous variables with normal and nonnormal distributions. χ2 tests were used for analysis of fibrocyte groups and dichotomous variables. Data analysis was performed in SPSS (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

RESULTS

Demographics and Fibrocyte Levels in Children With SCA and Healthy Controls

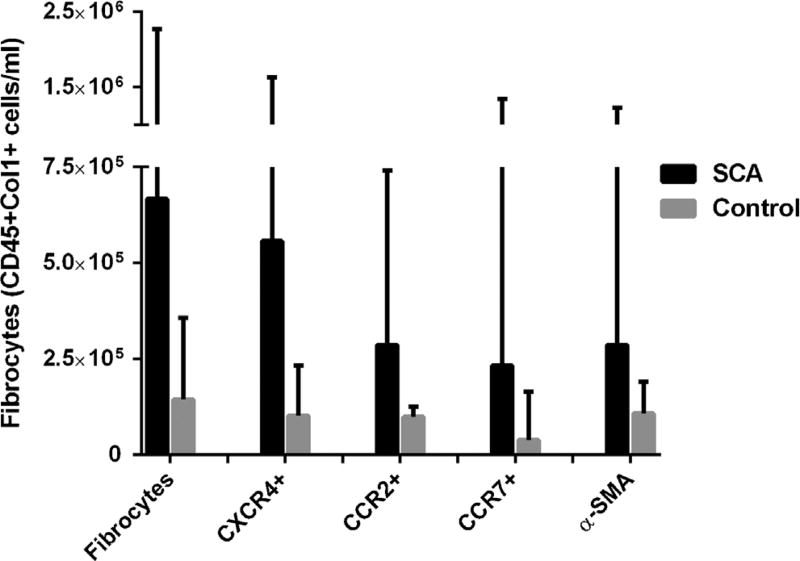

Fibrocyte levels were obtained from 45 children with SCA and 24 healthy, African American controls that participated in the SAC study and underwent pulmonary function testing (Table 1). The amount of time between pulmonary function testing and fibrocyte measurement was a mean of 0.5 ± 0.7 years. Compared to control subjects, children with SCA were older and had lower FEV1, forced vital capacity (FVC), and total lung capacity (TLC). Median levels of circulating fibrocytes were higher in children with SCA than controls (5.8 × 105 vs. 1.4 × 105, P < 0.01) (Fig. 1). The fibrocytes expressed a chemokine hierarchy, with CXCR4 expressed on 81% of fibrocytes and CCR2 and CCR7 expressed on a smaller subset. The activation marker α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), which demonstrates fibrocyte differentiation to a myofibroblast, was expressed in 43% of fibrocytes in children with SCA.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Healthy Controls and Children With Sickle Cell Anemia With and Without High Levels of Circulating Fibrocytes

| Children with SCA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Controls (n = 24) | SCD (n = 45) | P | Low fibrocyte (n = 39) |

High fibrocyte (n = 6) |

P | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 11 (2) | 14 (5) | <0.01 | 14 (5) | 18 (4) | 0.049 |

| Gender, % female | 50 | 53 | 0.8 | 51 | 67 | 0.5 |

| Pulmonary function tests | ||||||

| FEV1 (% predicted), mean (SD) | 98 (14) | 91 (13) | 0.03 | 90 (14) | 97 (9) | 0.3 |

| FVC (% predicted), mean (SD) | 104 (14) | 96 (13) | 0.01 | 95 (13) | 102 (11) | 0.2 |

| FEV1/FVC (% predicted), mean (SD) | 88 (2) | 89 (2) | 0.10 | 83 (6) | 83 (14) | 0.97 |

| TLC (% predicted), mean (SD) | 105 (14) | 85 (18) | <0.01 | 83 (18) | 94 (9) | 0.2 |

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| Hemogloblin (g/dl), mean (SD) | — | 8.0 (1) | — | 8.1 (1) | 7.4 (0.7) | 0.1 |

| WBC (cells/µl), mean (SD) | — | 12.8 (4) | — | 12.7 (4) | 13.2 (4) | 0.8 |

| Reticulocyte %, mean (SD) | — | 12.8 (6) | — | 11.9 (5) | 19.1 (8) | 0.005 |

| Oxygen saturation %, mean (SD) | — | 97 (3) | — | 96.7 (3) | 95.8 (2) | 0.5 |

| SCD characteristics | ||||||

| Pain episodes, median (IQR) | — | 0.40 (0.9) | — | 0.41 (0.9) | 0.18 (0.8) | 0.4 |

| Acute chest syndrome, (IQR) | — | 0.28 (0.4) | — | 0.30 (0.4) | 0.17 (0.2) | 0.2 |

| Hydroxyurea, % yes | — | 52 | — | 50 | 75 | 0.3 |

| Asthma characteristics | ||||||

| Asthma, % yes | — | 47 | — | 50 | 67 | 0.5 |

| Serum IgE, median (IQR) | — | 82 (159) | — | 89 (153) | 50 (320) | 0.9 |

| Eosinophil %, mean (SD) | — | 3.7 (3) | — | 3.7 (4) | 4.2 (2) | 0.7 |

SCA, sickle cell anemia; SD, standard deviation; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 sec; FVC, forced vital capacity; TLC, total lung capacity; IQR, inter-quartile range; WBC, white blood cell. Bold, P values < 0.5.

Fig. 1.

Median level of circulating fibrocytes (CD45+Col1+) in children with sickle cell anemia (SCA; black bars) and controls (gray bars). α-SMA, α-smooth muscle actin.

Association of Fibrocyte Levels, Clinical, and Laboratory characteristics

Children with SCA and increased fibrocyte levels had higher reticulocyte counts and were older compared to children with SCA and lower fibrocyte levels (Table 1). There was no association between fibrocyte level and pulmonary function tests, including lung volumes, asthma diagnoses, or other characteristics of an allergic diathesis. Percent predicted FEV1, FVC, FEV1/FVC, or TLC was also not significantly lower in patients with high levels of CXCR4+, CCR2+, or CCR7+ fibrocytes (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, the association between fibrocyte levels and a clinical phenotype, including lung disease, was assessed in children with SCA for the first time. Compared to healthy controls, fibrocyte levels were higher in children with SCA. The majority of fibrocytes in these children expressed the chemokine receptor CXCR4 and nearly half expressed α-SMA, a marker of differentiation to a myofibroblast. Children with SCA and increased fibrocyte levels had higher reticulocyte counts and were older than children with lower levels, but no association was found between higher fibrocyte level and pulmonary dysfunction or asthma. Higher levels of fibrocytes in children with SCA were similar to those in adults (median 5.8 × 105 vs. 3.5 × 105 fibrocytes/ml)13 and also suggest that factors related to the pathology of SCA cause the increased levels of fibrocytes.

In patients with SCA, hemolysis and resultant hypoxia may be responsible for the increased fibrocyte levels. Fibrocytes enter the circulation from the bone marrow and migrate to organs based on a chemokine axes.19 CXCR4 is expressed on the majority of fibrocytes, whereas CCR2 and CCR7 are expressed on a smaller subset. Prior studies show that CXCR4+ fibrocytes migrate to areas of injury, such as the lung, in response to the chemokine, CXCL12.20 In the case of CCR2 or CCR7 expression on fibrocytes, migration may be along a CCL7 or CCL19 chemokine gradient.20 Animal studies demonstrate that hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) may increase CXCR4 expression on fibrocytes.21 Thus, hypoxia may lead to CXCR4 expression and promote the entry of fibrocytes into circulation, presumably via a CXCL12 chemokine gradient.

Higher circulating fibrocyte levels in children with SCA were associated with increased reticulocyte counts. A shortened red cell life span, largely due to hemolysis, increases erythropoiesis and causes a reticulocytosis in children with SCA in response to lower oxygen carrying capacity.22 Low oxygen tension, sensed in the kidneys, causes the up-regulation of the transcription factor HIF-1α, which promotes the synthesis of erythropoietin and leads to the production of reticulocytes.23 Since increased HIF-1α expression also promotes CXCR4 expression on fibrocytes,21 the relationship between fibrocyte level and reticulocyte count may be secondary to the hypoxia-driven HIF-1α expression in children with SCA. Studies in murine models of SCA are needed to further examine the potential mechanistic link between HIF-1α, erythropoiesis, and fibrocyte level.

Older age was also associated with higher fibrocyte values. Although more severe lung and/or hypoxia in older children could explain the relationship with higher fibrocyte levels, the lack of an association between fibrocytes and any measure of pulmonary disease makes this less likely. Another possible explanation for the association of older age and higher fibrocytes is that age may be collinear with reticulocyte count. In the current study, older age and higher reticulocyte count were significantly associated. Other studies of children with SCA have also demonstrated that reticulocyte count increases with age.24 Finally, a type 1 error due to small sample size could explain the association of increased fibrocyte level and older age.

Fibrocyte levels were not associated with measures of lung function in children with SCA. In animal models, including the NY1DD sickle cell mouse model, there is evidence that fibrocytes migrate to the lungs and contribute to fibrosis.13 Increased fibrocyte levels have also been associated with progressive lung disease in patients with asthma and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.12,18 Given the abundant evidence that fibrocytes contribute to the pathogenesis of airway remodeling and pulmonary fibrosis, we anticipated that increased fibrocytes would be associated with decreased pulmonary function and/or asthma in this study. However, the cross-sectional study design may have affected our ability to detect an association between fibrocyte levels and pulmonary dysfunction or asthma. A one-time fibrocyte measurement, inherent to the cross-sectional design, may be less optimal if there are fluctuations in circulating fibrocyte levels over time. Longitudinal fibrocyte measurements may be better able to determine the relationship between fibrocyte level and pulmonary disease, if any exists. A longitudinal study design would also allow for the development of more severe lung disease in children. Potentially, pulmonary dysfunction did not have time to develop, despite increased fibrocyte levels, due to the younger age of participants.

Limitations were present in this study. First, the small sample size may have affected our ability to detect associations between fibrocyte levels and pulmonary function. However, those P values did not approach statistical significance, so we think a type 2 error is less likely. Second, fibrocyte levels were not drawn at the same time as laboratory measures or pulmonary function testing and, potentially, the time that elapsed between fibrocyte measurements and other tests could have impeded our ability to detect associations. Additionally, the children who participated in this study were a convenience sample of children enrolled in the SAC study from the St. Louis site. This group of children may not be representative of all children with SCA.

In summary, levels of circulating fibrocytes were higher in children with SCA compared to healthy controls. The underlying pathophysiology of SCA, increased hemolysis, hypoxia, and erythropoiesis, may be the cause of higher fibrocyte values. Given the preponderance of human and animal data that suggest fibrocytes contribute to airway remodeling in asthma pulmonary fibrosis, as well as other pathologies such as pulmonary hypertension,25 further investigation of the role of fibrocytes in the development of a progressive lung disease in children and adults with SCA with longitudinal studies is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Lisa Garrett, a research nurse coordinator at Washington University in St. Louis, who contributed significantly to the study. Dr. Field is a consultant and receives research support from NKT Therapeutics as well as research support from Astellas. Dr. Strieter is employed by Novartis.

Funding source: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Numbers: RO1 HL098526, R01 HL079937.

Conflict of interest: JJF is a consultant for NKT Therapeutics. He receives research funding from NKT Therapeutics and Astellas. RMS is employed by Novartis.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SCA

Sickle cell anemia

- FEV1

Forced expiratory volume in 1 sec

- FVC

Forced vital capacity

- TLC

Total lung capacity

- α-SMA

Alpha-smooth muscle actin

- HIF-1α

Hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha

References

- 1.Powars D, Weidman JA, Odom-Maryon T, Niland JC, Johnson C. Sickle cell chronic lung disease: prior morbidity and the risk of pulmonary failure. Medicine. 1988;67:66–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powars DR, Chan LS, Hiti A, Ramicone E, Johnson C. Outcome of sickle cell anemia: a 4-decade observational study of 1056 patients. Medicine. 2005;84:363–376. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000189089.45003.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasavda N, Woodley C, Allman M, Drasar E, Awogbade M, Howard J, Thein SL. Effects of co-existing alpha-thalassaemia in sickle cell disease on hydroxycarbamide therapy and circulating nucleic acids. Brit J Haematol. 2012;157:249–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd JH, Macklin EA, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR. Asthma is associated with acute chest syndrome and pain in children with sickle cell anemia. Blood. 2006;108:2923–2927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-011072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koumbourlis AC, Zar HJ, Hurlet-Jensen A, Goldberg MR. Prevalence and reversibility of lower airway obstruction in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 2001;138:188–192. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.111824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field JJ, DeBaun MR, Yan Y, Strunk RC. Growth of lung function in children with sickle cell anemia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:1061–1066. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klings ES, Wyszynski DF, Nolan VG, Steinberg MH. Abnormal pulmonary function in adults with sickle cell anemia. Am J Respirat Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1264–1269. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-125OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anthi A, Machado RF, Jison ML, Taveira-Dasilva AM, Rubin LJ, Hunter L, Hunter CJ, Coles W, Nichols J, Avila NA, Sachdev V, Chen CC, Gladwin MT. Hemodynamic and functional assessment of patients with sickle cell disease and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respirat Crit Care Med. 2007;175:1272–1279. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1498OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies DE, Wicks J, Powell RM, Puddicombe SM, Holgate ST. Airway remodeling in asthma: new insights. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:215–225. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strieter RM. Mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis: conference summary. Chest. 2001;120:77S–85S. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.1_suppl.s77-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strieter RM. What differentiates normal lung repair and fibrosis? Inflammation, resolution of repair, and fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:305–310. doi: 10.1513/pats.200710-160DR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang CH, Huang CD, Lin HC, Lee KY, Lin SM, Liu CY, Huang KH, Ko YS, Chung KF, Kuo HP. Increased circulating fibrocytes in asthma with chronic airflow obstruction. Am J Respirat Crit Care Med. 2008;178:583–591. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200710-1557OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Field JJ, Burdick MD, DeBaun MR, Strieter BA, Liu L, Mehrad B, Rose CE, Jr, Linden J, Strieter RM. The role of fibrocytes in sickle cell lung disease. PloS. 2012;7:e33702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomperts BN, Strieter RM. Fibrocytes in lung disease. J Leuk Biol. 2007;82:449–456. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0906587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strieter RM, Keeley EC, Hughes MA, Burdick MD, Mehrad B. The role of circulating mesenchymal progenitor cells (fibrocytes) in the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. J Leuk Biol. 2009;86:1111–1118. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0309132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strunk RC, Szefler SJ, Phillips BR, Zeiger RS, Chinchilli VM, Larsen G, Hodgdon K, Morgan W, Sorkness CA, Lemanske RF., Jr Relationship of exhaled nitric oxide to clinical and inflammatory markers of persistent asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehrad B, Burdick MD, Zisman DA, Keane MP, Belperio JA, Strieter RM. Circulating peripheral blood fibrocytes in human fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.11.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moeller A, Gilpin SE, Ask K, Cox G, Cook D, Gauldie J, Margetts PJ, Farkas L, Dobranowski J, Boylan C, O’Byrne PM, Strieter RM, Kolb M. Circulating fibrocytes are an indicator of poor prognosis in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respirat Crit Care Med. 2009;179:588–594. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1534OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metz CN. Fibrocytes: a unique cell population implicated in wound healing. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:1342–1350. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-2328-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:438–446. doi: 10.1172/JCI20997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehrad B, Burdick MD, Strieter RM. Fibrocyte CXCR4 regulation as a therapeutic target in pulmonary fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:1708–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertles JF, Milner PF. Irreversibly sickled erythrocytes: a consequence of the heterogeneous distribution of hemoglobin types in sickle-cell anemia. J Clin Invest. 1968;47:1731–1741. doi: 10.1172/JCI105863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Semenza GL. HIF-1: mediator of physiological and pathophysiological responses to hypoxia. J App Physiol. 2000;88:1474–1480. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.4.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown AK, Sleeper LA, Miller ST, Pegelow CH, Gill FM, Waclawiw MA. Reference values and hematologic changes from birth to 5 years in patients with sickle cell disease. Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:796–804. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1994.02170080026005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeager ME, Nguyen CM, Belchenko DD, Colvin KL, Takatsuki S, Ivy DD, Stenmark KR. Circulating fibrocytes are increased in children and young adults with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:104–111. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00072311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]