Abstract

The soluble carrier (SLC) family plays an important role in cell metabolism. The purpose of the current study was to screen SLCs as potential prognostic factors in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). A total of 509 patients with ccRCC from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) cohort were enrolled in this study. The expression profile of SLCs was obtained from the TCGA RNAseq database. Metadata of the TCGA cohort, including age, sex, TNM stage, tumor grade, American Joint Committee on Cancer stage, laterality, and overall survival, were collected. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to analyze the relative factors. Prognosis-associated genes were further validated in a Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC) cohort consisting of 178 patients. Among a total of 364 SLC transporters, 61 were independent predictors of ccRCC patient overall survival. Among the 61 SLC transporters, 26 were significantly downregulated and 23 were significantly upregulated in tumor tissues compared with non-malignant kidney tissues. Analyses of two open source, RNA expression data sets on sunitinib response revealed that SLC10A2 was downregulated in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant samples. We validated SLC10A2 expression in the FUSCC cohort and showed that SLC10A2 expression was an independent prognostic predictor of overall survival of ccRCC (hazard ratio=0.432, 95% CI: 0.204-0.915). Our results identified a number of associations of SLC gene expression with prognosis of ccRCC patients, indicating that these genes may represent possible oncogenes that could serve as therapeutic targets of ccRCC.

Keywords: biomarker, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, prognosis, soluble carriers, transporters.

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for approximately 2% of all malignancies in adults 1. The majority of RCC cases are the clear cell RCC (ccRCC) subtype. Despite extensive efforts towards improving diagnosis and treatment strategies for ccRCC, more than 30% of patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis and 20-40% of RCC patients who undergo radical surgical procedures eventually develop metastasis 2. Important prognostic models for ccRCC, including SSIGN 3, 4, ccA/ccB 5, clearcode34 6, and S3-score 1, have provided insight into the molecular predictors of poor outcome in ccRCC. Notably, members of the soluble carrier (SLC) gene family are involved in each of these models 1, 6.

To date, a total of 378 SLC members categorized into 51 families have been identified 7. SLC family genes encode passive transporters, ion coupled transporters and exchangers, and represent a major portion of human transporter-related genes 8. Rapidly proliferating cancer cells require enhanced anabolic pathways to support cell mitosis 9. Consistent with the increased amino acid and glucose uptake in cancer cells, elevated expression of nutrient transporter proteins is associated with aggressive and highly malignant cancers 10. Despite the important role of amino acids, glucose and iron transporters in cancer, the SLC family has not been well examined in ccRCC. In the present study, we analyzed the potential prognostic association of SLC expression in a ccRCC cohort from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and validated the results in the Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC) cohort, another Asian cohort.

Material and Methods

Patients and samples

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center (FUSCC), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before the study. Expression of SLC family members (IlluminaHiSeq) and metadata of the ccRCC patient TCGA cohort were downloaded from the Cancer Genomics Browser of the University of California Santa Cruz (https://genome-cancer.ucsc.edu/). A total of 364 SLC members were included in the analysis. The detail annotations of these genes have been reviewed in the website of bioparadigms (http://slc.bioparadigms.org). In the TCGA ccRCC cohort, only patients with fully characterized ccRCC tumors, intact overall survival (OS), and disease-free survival (DFS) data, and complete RNAseq data were included. OS was defined as time from the date of diagnosis to the date of death or last follow-up. Patients without events or death at the time of the last follow-up were recorded as censored. Sixteen patients were excluded because of non-ccRCC pathology reported in a previous study 1. A final 509 patients were enrolled in the present study. Demographic and clinical parameters, including age, sex, tumor size, TNM, Fuhrman grade, AJCC stage, laterality and OS were collected.

In the FUSCC validation cohort, a total of 178 ccRCC patients from 2007 to 2011 who underwent radical nephrectomy or nephron-sparing nephrectomy were retrospectively enrolled. Tissue samples were collected once resected and stored at -70°C in the tissue bank of FUSCC. A central review of pathology was performed by an experienced pathologist. Clinicopathological characteristics were obtained from electronic records. Patients were regularly followed up by telephone, mail, or in the clinic once every 3 months.

SLC gene expression in sunitinib resistance

Two open source, RNA expression data sets on sunitinib response were downloaded from the GEO database (GSE64052 and GSE65615) 11, 12. Gene expression data and metadata were processed by MeV software 13. The samples were separated into sunitinib-treated and untreated groups and t tests were used to compare differences.

Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was isolated from 178 frozen ccRCC tumors from the FUSCC validation cohort using TRIzol® reagent (15596-026, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The PrimeScript RT reagent kit (K1622, Thermo Scientific, Lithuania) was used to synthesize first-strand cDNA. SYBR Green real-time PCR assays were performed using an ABI 7900HT (Applied Biosystems, USA). The expression levels of SLCs were normalized to the level of β-actin 14. The primers for qRT-PCR analysis were synthesized by Sangon (Shanghai, People's Republic of China). The primers sequences are as follows: SLC10A2 (ASBT), forward primer, 5′-TGGGTTTCTTCCTGGCTAGACT-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-TGTTCTGCATTCCAGTTTCCAA-3′ 15; and β-actin: forward primer: 5′-AGCGAGCATCCCCCAAAGTT-3′, reverse primer: 5′-GGGCACGAAGGCTCATCATT-3′.

Statistical analysis

R project and SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois) were used to perform statistical analysis. Survival curves were constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method and plotted with Graphpad Prism 6. Log-rank tests were used to assess the differences between the groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional HR of all SLCs expression and OS for patients with ccRCC in the TCGA cohort were analyzed. We used a paired t test to compare tumor and normal SLC expression data. A t test was used to compare expression data between sunitinib-resistant and non-resistant groups. T test was used compare continuous variables while χ2 test was applied in category variables. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of ccRCC patients in TCGA and FUSCC cohorts

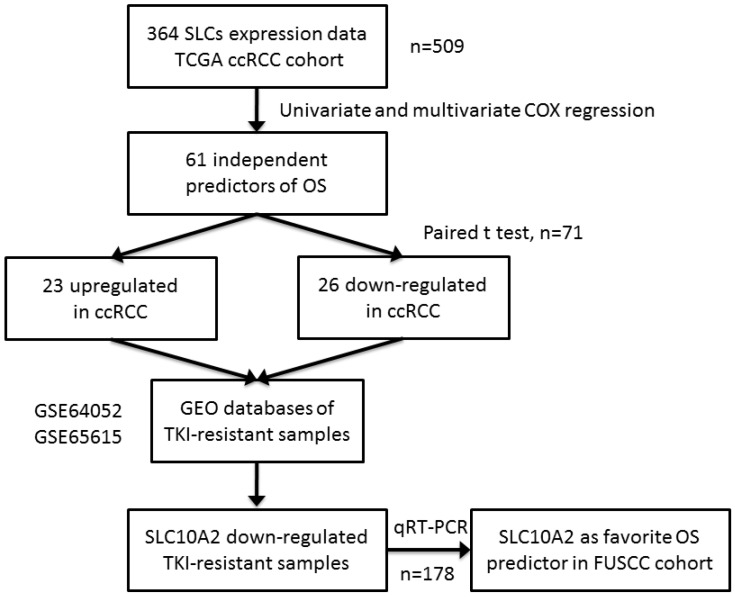

The workflow of this study is shown in Figure 1. The TCGA cohort comprised 328 (64.4%) male patients and 181 (35.6%) female patients. The median age of the 509 ccRCC patients was 61 years, with a range from 26 to 90 years. TNM, tumor size, nuclear grade, stage, laterality are shown in Table 1. The median follow-up time was 35.8 months and 162 patients died during follow-up.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the experimental design and main procedures. To identify a robust prognostic of gene expression signature of SLCs in ccRCC, we used TCGA dataset of 509 samples as a discovery set. A list of 364 SLCs was brought into univariate and multivariate Cox hazard ratio model and 61 SLCs were independent prognostic factors of OS. They were compared in 71 paired normal and cancer tissue with paired t test. 26 were downregulated and 23 were upregulated in tumor tissues compared with normal kidney tissues. The 49 SLCs were compared in TKI-resistant versus non-resistant tissues in GEO database and only SLC10A2 were consistent with TKI-resistant status. At last, we used qRT-PCR validated SCL10A2 as a favorable predictors of OS in FUSCC cohort.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologial Characterisics of patients with ccRCC in TCGA and FUSCC cohort

| Variables | TCGA cohort(N=509) | FUSCC cohort(N=178) | p1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Age, median(range) | 61(26 to 90) | 56(25 to 86) | <0.0012 | ||

| Gender | 0.360 | ||||

| Male | 328 | 64.4 | 122 | 68.5 | |

| Female | 181 | 35.6 | 56 | 31.5 | |

| Tumor size, mean(range) | 1.68(0.4 to 4.0) | 5.00(1.0 to 16.0) | <0.0012 | ||

| Laterality | 0.270 | ||||

| Left | 239 | 47 | 82 | 46.1 | |

| Right | 269 | 52.8 | 94 | 52.8 | |

| bilateral | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 1.1 | |

| Grade | 0.051 | ||||

| 1 | 12 | 2.4 | 9 | 5.1 | |

| 2 | 222 | 43.6 | 72 | 40.4 | |

| 3 | 197 | 38.7 | 81 | 45.5 | |

| 4 | 74 | 14.5 | 16 | 9 | |

| Gx | 4 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| pT | <0.001 | ||||

| T1 | 258 | 50.7 | 126 | 70.8 | |

| T2 | 63 | 12.4 | 23 | 12.9 | |

| T3 | 178 | 35 | 25 | 14 | |

| T4 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 2.2 | |

| N | <0.001 | ||||

| N0 | 228 | 44.8 | 169 | 94.9 | |

| N1 | 17 | 3.3 | 2 | 1.1 | |

| Nx | 264 | 51.9 | 7 | 3.9 | |

| M | <0.001 | ||||

| M0 | 406 | 79.8 | 171 | 96.1 | |

| M1 | 78 | 15.3 | 6 | 3.4 | |

| Mx | 25 | 4.9 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Stage | <0.001 | ||||

| I | 253 | 49.7 | 125 | 70.2 | |

| II | 51 | 10 | 20 | 11.2 | |

| III | 125 | 24.6 | 25 | 14 | |

| IV | 80 | 15.7 | 8 | 4.5 | |

1 χ2 test or indicated otherwise.

2 t test.

TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; FUSCC, Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center

The FUSCC cohort comprised 122 (70.3%) male patients and 56 (29.7%) female patients. The median age of the 178 ccRCC patients was 56 years, with a range from 25 to 86 years. The detailed clinical data are shown in Table 1. The median follow-up time was 50.2 months and 40 patients died during follow-up.

Screening candidate prognostic genes in the SLC family in the TCGA cohort

We first conducted univariate Cox proportion hazard ratio analysis for screening 364 SLC family members as well as clinicopathological variables as prognostic factors. Age, laterality, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage, Fuhrman grade, pathological T stage, M stage, tumor necrosis, preoperative white blood cell count, and 199 SLC genes were significantly associated with overall survival (OS) of ccRCC patients in the TCGA cohort (all P < 0.05; Supplementary Table 1). Only variables that were significantly associated with prognosis in previous univariate Cox regression (P < 0.01), which included a total of 165 SLC genes, were used to build a reduced multivariate model. Backward stepwise multivariate Cox regression demonstrated that in the final model, age (hazard ratio [HR]=1.045, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.025-1.065), T stage (HR=0.110, 95% CI: 0.059-0.206), AJCC stage (HR=16.099, 95% CI: 7.687-33.718), tumor necrosis (HR=2.676, 95% CI: 1.438-4.980), and 61 SLC members were independent prognostic factors (all P < 0.05; Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox hazard ratio regression model of clinical parameters and soluble carrier super family expression in TCGA ccRCC cohort

| Parameters | HR | 95%CI | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.045 | 1.025-1.065 | 0.000 |

| T | 0.110 | 0.059-0.206 | 0.000 |

| M | 0.365 | 0.133-1.002 | 0.050 |

| stage | 16.099 | 7.687-33.718 | 0.000 |

| Necrosis | 2.676 | 1.438-4.980 | 0.002 |

| SLC2A13 | 0.382 | 0.228-0.640 | 0.000 |

| SLC4A5 | 0.536 | 0.342-0.840 | 0.007 |

| SLC4A8 | 0.502 | 0.322-0.782 | 0.002 |

| SLC5A5 | 0.321 | 0.234-0.441 | 0.000 |

| SLC5A6 | 0.439 | 0.241-0.799 | 0.007 |

| SLC6A7 | 0.618 | 0.454-0.841 | 0.002 |

| SLC7A9 | 1.463 | 1.101-1.944 | 0.009 |

| SLC6A15 | 1.225 | 1.056-1.421 | 0.007 |

| SLC6A19 | 0.812 | 0.730-0.903 | 0.000 |

| SLC9A3R2 | 0.437 | 0.263-0.725 | 0.001 |

| SLC9A5 | 2.087 | 1.344-3.242 | 0.001 |

| SLC10A2 | 0.788 | 0.695-0.893 | 0.000 |

| SLC10A3 | 0.458 | 0.209-1.006 | 0.052 |

| SLC10A5 | 1.660 | 1.230-2.239 | 0.001 |

| SLC10A6 | 0.791 | 0.626-0.999 | 0.049 |

| SLC11A2 | 0.189 | 0.089-0.401 | 0.000 |

| SLC12A4 | 0.050 | 0.018-0.137 | 0.000 |

| SLC12A7 | 4.223 | 2.484-7.180 | 0.000 |

| SLC12A8 | 1.323 | 1.100-1.590 | 0.003 |

| SLC13A4 | 0.478 | 0.369-0.619 | 0.000 |

| SLC14A1 | 0.775 | 0.628-0.956 | 0.017 |

| SLC16A8 | 2.721 | 1.843-4.015 | 0.000 |

| SLC17A1 | 2.007 | 1.623-2.482 | 0.000 |

| SLC17A5 | 0.234 | 0.128-0.426 | 0.000 |

| SLC17A7 | 2.325 | 1.755-3.082 | 0.000 |

| SLC18A3 | 1.106 | 1.025-1.194 | 0.009 |

| SLC20A1 | 4.324 | 2.090-8.946 | 0.000 |

| SLC22A2 | 1.320 | 1.136-1.535 | 0.000 |

| SLC22A20 | 1.905 | 1.367-2.655 | 0.000 |

| SLC24A6 | 5.529 | 1.980-15.443 | 0.001 |

| SLC25A14 | 2.330 | 1.041-5.216 | 0.040 |

| SLC25A19 | 0.129 | 0.060-0.278 | 0.000 |

| SLC25A23 | 0.334 | 0.198-0.565 | 0.000 |

| SLC25A27 | 1.588 | 1.180-2.136 | 0.002 |

| SLC25A28 | 4.264 | 1.776-10.237 | 0.001 |

| SLC25A29 | 0.449 | 0.269-0.749 | 0.002 |

| SLC25A35 | 4.743 | 2.572-8.745 | 0.000 |

| SLC25A37 | 2.606 | 1.674-4.057 | 0.000 |

| SLC25A39 | 10.389 | 4.152-25.994 | 0.000 |

| SLC25A46 | 0.317 | 0.142-0.709 | 0.005 |

| SLC26A1 | 0.349 | 0.248-0.491 | 0.000 |

| SLC26A8 | 0.614 | 0.443-0.852 | 0.003 |

| SLC30A1 | 2.376 | 1.377-4.102 | 0.002 |

| SLC35A3 | 3.246 | 1.655-6.368 | 0.001 |

| SLC35B2 | 4.723 | 2.089-10.679 | 0.000 |

| SLC35B4 | 6.985 | 3.063-15.931 | 0.000 |

| SLC35D3 | 0.534 | 0.320-0.892 | 0.016 |

| SLC35E4 | 5.431 | 2.774-10.631 | 0.000 |

| SLC35F1 | 0.744 | 0.544-1.016 | 0.063 |

| SLC35F3 | 1.191 | 1.023-1.386 | 0.025 |

| SLC35F5 | 4.297 | 1.990-9.281 | 0.000 |

| SLC38A10 | 5.816 | 2.615-12.936 | 0.000 |

| SLC38A11 | 0.693 | 0.569-0.846 | 0.000 |

| SLC38A6 | 2.046 | 1.087-3.850 | 0.027 |

| SLC39A3 | 0.156 | 0.069-0.352 | 0.000 |

| SLC39A9 | 11.986 | 3.674-39.103 | 0.000 |

| SLC40A1 | 0.371 | 0.242-0.569 | 0.000 |

| SLC43A3 | 1.507 | 0.968-2.346 | 0.069 |

| SLC44A1 | 0.484 | 0.224-1.047 | 0.065 |

| SLC44A4 | 1.285 | 1.086-1.521 | 0.003 |

| SLC45A2 | 0.572 | 0.458-0.716 | 0.000 |

| SLC45A4 | 0.678 | 0.441-1.042 | 0.077 |

| SLC46A2 | 1.378 | 0.990-1.918 | 0.057 |

| SLC47A1 | 0.608 | 0.466-0.792 | 0.000 |

| SLCO2A1 | 2.505 | 1.697-3.700 | 0.000 |

| SLCO4C1 | 1.529 | 1.168-2.001 | 0.002 |

| SLCO5A1 | 0.617 | 0.455-0.835 | 0.002 |

*Parameters that were significant (p<0.01) in univariate cox regression model entered the multivariate model. Backward Cox regression procedure was used to build the multivariate model;

P<0.05 were indicated as bold type

Comparison of prognostic SLC gene expressions in tumor and adjacent kidney tissues

71 paired normal and tumor tissues in TCGA database were enrolled in the following analysis. A paired t test showed that among the 61 prognostic SLC genes, 26 were downregulated and 23 were upregulated in tumor tissues compared with normal kidney tissues (all P < 0.05; Table 3). Twelve genes were upregulated in tumor tissues and associated with poor prognosis (Table 3). Gene ontology analysis showed that these genes were associated with energy metabolism and small molecular transportation (detailed in Supplementary Table 2). Eleven upregulated SLC genes were associated with favorable outcome of ccRCC (Table 3). The gene ontology analyses are detailed in Supplementary Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparision of ccRCC tumors versus adjacent normal tissues in SLCs

| Gene Name | Normal(N=71) | Tumor(N=71) | Fold change | P* | Tumor expression | HRa | Survival association | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||||

| SLC2A13 | 10.204 | 0.635 | 9.422 | 0.672 | 0.582 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.382 | favourable |

| SLC4A5 | 5.558 | 0.598 | 6.246 | 0.669 | 1.610 | 0.000 | upregulated | 0.536 | favourable |

| SLC4A8 | 7.642 | 1.503 | 4.821 | 0.809 | 0.142 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.502 | favourable |

| SLC5A5 | 0.385 | 0.479 | 0.807 | 0.731 | 1.341 | 0.000 | upregulated | 0.321 | favourable |

| SLC5A6 | 8.755 | 0.269 | 8.645 | 0.551 | 0.926 | 0.089 | down regulated | 0.439 | favourable |

| SLC6A15 | 2.694 | 1.299 | 1.313 | 2.319 | 0.384 | 0.000 | down regulated | 1.225 | poor |

| SLC6A19 | 9.841 | 3.900 | 6.768 | 3.642 | 0.119 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.812 | favourable |

| SLC6A7 | 0.326 | 0.417 | 0.653 | 0.579 | 1.255 | 0.000 | upregulated | 0.618 | favourable |

| SLC7A9 | 7.693 | 3.520 | 8.114 | 1.797 | 1.339 | 0.384 | upregulated | 1.463 | poor |

| SLC9A3R2 | 11.025 | 0.527 | 10.640 | 1.071 | 0.766 | 0.006 | down regulated | 0.437 | favourable |

| SLC9A5 | 2.770 | 0.747 | 3.379 | 0.931 | 1.526 | 0.000 | upregulated | 2.087 | poor |

| SLC10A2 | 5.943 | 3.612 | 7.542 | 2.903 | 3.029 | 0.001 | upregulated | 0.788 | favourable |

| SLC10A5 | 3.207 | 0.969 | 3.588 | 1.381 | 1.303 | 0.039 | upregulated | 1.660 | poor |

| SLC10A6 | 1.647 | 0.824 | 4.115 | 1.348 | 5.532 | 0.000 | upregulated | 0.791 | favourable |

| SLC11A2 | 10.643 | 0.265 | 9.898 | 0.463 | 0.597 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.189 | favourable |

| SLC12A4 | 10.279 | 0.377 | 10.773 | 0.472 | 1.408 | 0.000 | upregulated | 0.050 | favourable |

| SLC12A7 | 11.044 | 0.449 | 11.885 | 0.756 | 1.791 | 0.000 | upregulated | 4.223 | poor |

| SLC12A8 | 7.729 | 0.725 | 6.235 | 2.053 | 0.355 | 0.000 | down regulated | 1.323 | poor |

| SLC13A4 | 1.678 | 0.709 | 1.626 | 1.002 | 0.965 | 0.668 | down regulated | 0.478 | favourable |

| SLC14A1 | 9.823 | 1.744 | 6.655 | 1.440 | 0.111 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.775 | favourable |

| SLC16A8 | 1.589 | 0.609 | 1.922 | 0.743 | 1.260 | 0.003 | upregulated | 2.721 | poor |

| SLC17A1 | 8.239 | 3.517 | 7.703 | 2.262 | 0.690 | 0.265 | down regulated | 2.007 | poor |

| SLC17A5 | 10.316 | 0.460 | 10.121 | 0.452 | 0.874 | 0.014 | down regulated | 0.234 | favourable |

| SLC17A7 | 3.830 | 0.756 | 2.589 | 0.970 | 0.423 | 0.000 | down regulated | 2.325 | poor |

| SLC18A3 | 0.126 | 0.219 | 1.733 | 2.561 | 3.047 | 0.000 | upregulated | 1.106 | poor |

| SLC20A1 | 9.739 | 0.819 | 9.347 | 0.546 | 0.762 | 0.001 | down regulated | 4.324 | poor |

| SLC22A2 | 12.165 | 0.830 | 11.981 | 1.703 | 0.880 | 0.406 | down regulated | 1.320 | poor |

| SLC22A20 | 1.668 | 0.665 | 1.267 | 1.093 | 0.757 | 0.009 | down regulated | 1.905 | poor |

| SLC24A6 | 9.610 | 0.560 | 9.401 | 0.510 | 0.866 | 0.023 | down regulated | 5.529 | poor |

| SLC25A14 | 6.558 | 0.226 | 6.819 | 0.473 | 1.199 | 0.000 | upregulated | 2.330 | poor |

| SLC25A19 | 7.333 | 0.451 | 7.597 | 0.618 | 1.201 | 0.002 | upregulated | 0.129 | favourable |

| SLC25A23 | 11.591 | 0.265 | 11.270 | 0.557 | 0.801 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.334 | favourable |

| SLC25A27 | 6.012 | 0.722 | 5.426 | 1.157 | 0.666 | 0.000 | down regulated | 1.588 | poor |

| SLC25A28 | 8.857 | 0.223 | 9.194 | 0.449 | 1.264 | 0.000 | upregulated | 4.264 | poor |

| SLC25A29 | 9.428 | 0.516 | 7.762 | 0.758 | 0.315 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.449 | favourable |

| SLC25A35 | 7.546 | 0.447 | 5.770 | 0.633 | 0.292 | 0.000 | down regulated | 4.743 | poor |

| SLC25A37 | 8.177 | 0.391 | 8.693 | 0.753 | 1.430 | 0.000 | upregulated | 2.606 | poor |

| SLC25A39 | 11.626 | 0.388 | 10.775 | 0.825 | 0.555 | 0.000 | down regulated | 10.389 | poor |

| SLC25A46 | 9.719 | 0.271 | 9.534 | 0.441 | 0.880 | 0.002 | down regulated | 0.317 | favourable |

| SLC26A1 | 7.260 | 1.512 | 7.080 | 1.480 | 0.883 | 0.447 | down regulated | 0.349 | favourable |

| SLC26A8 | 1.085 | 0.753 | 0.974 | 0.670 | 0.926 | 0.324 | down regulated | 0.614 | favourable |

| SLC30A1 | 9.423 | 0.496 | 8.738 | 0.797 | 0.622 | 0.000 | down regulated | 2.376 | poor |

| SLC35A3 | 9.031 | 0.347 | 8.450 | 0.584 | 0.668 | 0.000 | down regulated | 3.246 | poor |

| SLC35B2 | 10.440 | 0.311 | 10.409 | 0.442 | 0.979 | 0.630 | down regulated | 4.723 | poor |

| SLC35B4 | 9.897 | 0.338 | 9.776 | 0.414 | 0.919 | 0.054 | down regulated | 6.985 | poor |

| SLC35D3 | 0.106 | 0.236 | 0.121 | 0.254 | 1.010 | 0.736 | upregulated | 0.534 | favourable |

| SLC35E4 | 5.838 | 0.683 | 6.252 | 0.683 | 1.333 | 0.000 | upregulated | 5.431 | poor |

| SLC35F3 | 4.163 | 0.796 | 4.289 | 2.109 | 1.091 | 0.652 | upregulated | 1.191 | poor |

| SLC35F5 | 10.989 | 0.416 | 10.350 | 0.502 | 0.642 | 0.000 | down regulated | 4.297 | poor |

| SLC38A10 | 11.228 | 0.270 | 11.475 | 0.707 | 1.187 | 0.005 | upregulated | 5.816 | poor |

| SLC38A11 | 6.429 | 0.952 | 4.900 | 1.073 | 0.346 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.693 | favourable |

| SLC38A6 | 7.186 | 0.500 | 7.535 | 0.629 | 1.274 | 0.000 | upregulated | 2.046 | poor |

| SLC39A3 | 8.554 | 0.394 | 8.042 | 0.723 | 0.701 | 0.000 | down regulated | 0.156 | favourable |

| SLC39A9 | 11.540 | 0.170 | 10.931 | 0.365 | 0.656 | 0.000 | down regulated | 11.986 | poor |

| SLC40A1 | 11.979 | 0.368 | 12.193 | 0.734 | 1.160 | 0.014 | upregulated | 0.371 | favourable |

| SLC44A4 | 10.762 | 0.714 | 7.992 | 1.768 | 0.147 | 0.000 | down regulated | 1.285 | poor |

| SLC45A2 | 1.580 | 0.779 | 2.314 | 1.551 | 1.664 | 0.000 | upregulated | 0.572 | favourable |

| SLC47A1 | 10.669 | 1.642 | 11.761 | 1.775 | 2.132 | 0.000 | upregulated | 0.608 | favourable |

| SLCO2A1 | 10.732 | 1.249 | 11.441 | 1.227 | 1.634 | 0.001 | upregulated | 2.505 | poor |

| SLCO4C1 | 11.011 | 0.531 | 11.150 | 1.221 | 1.101 | 0.325 | upregulated | 1.529 | poor |

| SLCO5A1 | 1.377 | 1.034 | 2.368 | 1.221 | 1.987 | 0.000 | upregulated | 0.617 | favourable |

*P paired t test, two side. P<0.05 were indicated as bold type

a Hazard ratio of overall survival

SLC gene expression in sunitinib resistance

We next analyzed SLC gene expression in sunitinib resistance by analyzing two open source, RNA expression data sets on sunitinib response from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (GSE64052 and GSE65615) as described in Materials and Methods. In a previous study by Zhang 11, human RCC cell lines were implanted into the flanks of nude mice to establish a xenograft mouse model and mice were treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; sunitinib or sorafenib). Gene expression analysis was performed using the GPL570 platform. Two groups of tumors (14 TKI treated and 15 untreated) were compared by t test. Mean values were used in cases in which different probes represent a single gene. The results showed that SLC25A37 was upregulated in TKI-treated xenografts compared with untreated tumors, while eight genes, SLC10A2, SLC17A1, SLC22A2, SLC25A19, SLC25A37, SLC38A6, SLC40A1, and SLC44A4, were decreased in TKI-treated xenografts (all P < 0.05; Supplementary Table 3).

Stewart et al. 12 performed RNAseq in 75 sunitinib-treated and 47 untreated ccRCC samples to investigate the effect of VEGF targeted therapy (sunitinib) on metastatic ccRCC. Our analyses revealed that 12 genes were significantly increased in sunitinib-treated samples compared with untreated samples (all P < 0.05; Supplementary Table 3). Eight genes were decreased in sunitinib-treated samples (all P < 0.05; Supplementary Table 3).

SLC10A2 expression is a prognostic factor for OS in the FUSCC cohort

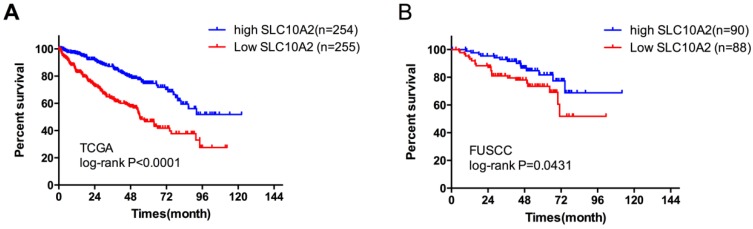

Evaluation of both datasets described above revealed that only SLC10A2 was significantly downregulated in TKI-treated samples. Our previous results showed that SLC10A2 was upregulated in ccRCC compared with adjacent kidney tissues in paired TCGA samples. High SLC10A2 expression was associated with good prognosis of ccRCC. We divided the TCGA cohort into low- and high-expression groups according to the median SLC10A2 expression level. In a multivariate regression model, tumor stage (odds ratio [OR]=0.545, 95% CI: 0.398-0.745) and necrosis (OR=0.352, 95% CI: 0.195-0.634) were associated with SLC10A2 expression (Table 4). Therefore, we next validated the prognostic predictor role of SLC10A2 in the FUSCC cohort. A total of 37 patients deceased with a mean follow up time 87.2 months. In multivariate Cox regression model, we found that stage (HR=4.654, 95%CI: 2.029-10.674) and low SLC10A2 expression (HR=0.432,95%CI: 0.204-0.915) were associated with poor prognosis for OS (Table 5). We divided the cohort into low- and high-expression groups according to the median expression level of SLC10A2 and the Kaplan-Meier curves are shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Multivariate regression analysis of clinicopathological paramters and SCL10A2 in TCGA cohort

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.991 | (0.975-1.007) | 0.276 |

| Sex | 1.261 | (0.830-1.915) | 0.277 |

| Grade | 0.545 | (0.398-0.745) | 0.000 |

| Laterality | 1.226 | (0.827-1.817) | 0.311 |

| Tumor size | 0.694 | (0.781-1.450) | 0.694 |

| Necrosis | 0.352 | (0.195-0.634) | 0.001 |

| AJCC Stage | 0.881 | (0.728-1.067) | 0.196 |

Sex, female vs male. Laterality, left vs right. P<0.05 were indicated as bold type. SCL10A2 were dichotomized as two group with median expression value.

Table 5.

Multivariate Cox hazard ratio regression model of clinical parameters and SLC10A2 in FUSCC ccRCC cohort

| Parameters | HR | 95%CI | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.755 | (0.347-1.639) | 0.477 |

| T | 1.042 | (0.543-2.002) | 0.901 |

| M | 0.332 | (0.062-1.768) | 0.196 |

| Stage | 4.654 | (2.029-10.674) | <0.001 |

| Necrosis | 4.087 | (0.701-23.824) | 0.118 |

| SLC10A2 | 0.432 | (0.204-0.915) | 0.028 |

*P<0.05 were indicated as bold type. T, M, were pathological stage, stage was AJCC stage. SLC10A2 were used -delta CT to beta-actin

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots of survival in the TCGA and FUSCC cohorts according to SLC10A2 expression. A. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival (OS) according to SLC10A2 expression level in the TCGA cohort. B. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS according to SLC10A2 expression level in the FUSCC cohort.

Discussion

In the present study, we comprehensively demonstrated that gene expressions of SLC family members were correlated with the outcome of ccRCC patients. A total of 364 SLC members categorized into 49 families were investigated in this study. Our results showed that 61 of these genes were independent prognostic factors for OS of ccRCC patients. Among the 61 genes, we found that 49 showed differential expression between benign and malignant tissues. Moreover, SLC10A2 was associated with TKI response in two separate studies. We validated this finding in the FUSCC cohort to confirm that SLC10A2 was an independent predictor of ccRCC outcome.

SLCs comprise a superfamily encoding transporter-related genes. Transporters are the gatekeepers for all cells, controlling uptake and efflux of crucial metabolism compounds 8. It has been well established that tumor cells have different metabolism patterns compared with normal tissues. For instance, 18F-FDG has been used as a marker of tumors for enhanced glucose uptake of tumor cells 16.

In the multivariate analysis of TCGA and FUSCC cohort, significant parameters were different. Such as T stage and necrosis in TCGA and only T stage in FUSCC. We did not include necrosis in FUSCC analysis because we cannot fully access the necrosis criteria of TCGA. In analysis of TCGA, more parameters were included, this may also affect the results.

Our results showed that SLC9A5, SLC10A5, SLC12A7, SLC16A8, SLC18A3, SLC25A14, SLC25A28, SLC25A37, SLC35E4, SLC38A10, SLC38A6, and SLCO2A1 were upregulated in ccRCC and associated with poor prognosis, indicating that these genes may represent possible oncogenes that could serve as therapeutic targets of ccRCC. No reports have been published on the association between the above genes and prognosis of ccRCC until now. These genes are dysregulated in ccRCC and have multiple functions regarding amino acid, nucleoside, inorganic, and organic anion transduction and as mitochondrial carriers 17. SLCs have been reported to be associated with chemotherapeutic drug transport in pancreatic, colorectal, and hepatocyte cancers 18-20. Further study on drugs that modulate SLCs may help to further the development of anti-cancer drugs.

In our analyses of sunitinib resistance in ccRCC, we identified SLC10A2 as a possible target. SLC10 is an influx transporter of bile acids, steroidal hormones, various drugs, and several other substrates 21. SLC10A2, also called apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT) 22, is highly expressed in the intestine and participates in bile acid recycling 23. In proximal tubule cells, ASBT facilitates bile acid reclaiming from primary urine 21. Previous studies showed that ASBT is regulated by the glucocorticoid receptor 24, vitamin D receptor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α 25, and caudal-type homeobox-1 and -2 26. ASBT is also upregulated by vitamin D, glucocorticoids, and ampicillin and inhibited by statins and dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers 21. Because ASBT expression was associated with prognosis and sunitinib response, and given that therapeutic drugs regulating ASBT already exist, further research on this gene and tumor phenotypes of ccRCC is warranted.

Although previous literature has shown that the SLC family plays an important role in the prognosis of various cancers 18, 19, no study has examined their role in RCC. Our work indicates a correlation between ccRCC outcome and this gene family. However, the underlying mechanism still remains unclear and should be the subject of future studies.

A major strength of the present study is that the data were obtained from two large populations with a long follow-up. The TCGA ccRCC cohort is not a clinical trial population, with diminished selection bias, and thus could be more representative as a “real-world” population. Another strength is that comprehensive analysis of SLC in TKI treatment was conducted in two open source GEO databases.

However, certain limitations should be noted. The prognosis of ccRCC is affected by many factors such as tumor stage, operation performance, and response to TKI therapy. These factors could not all be included in the multivariate prognostic model. In particular, the TCGA cohort does not include information on TKI therapy. The two GEO data sets were acquired by different platforms with different experiment settings. Inconsistent results could thus not be simply considered as insignificant. The validation cohort has a smaller case numbers than TCGA cohort. Because we did not get such resources as TCGA group did to recruit more patients with RNA sequencing in a period of time. The mechanisms of SLC10A2 were not included in this article. Further clinical study and/or meta-analyses are needed to confirm our results.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that the expression of several SLCs predicted the clinical outcome of ccRCC patients. We found a considerable variability in the gene expression of SLC transporters between tumor and normal human kidney tissues. SLC10A2 was identified as an independent prognostic factor of overall survival of ccRCC and SLC10A2 expression was decreased in sunitinib-resistant ccRCC. Further studies investigating the role and mechanism of SLC transporters in ccRCC are needed.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary tables.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the contributors to the Cancer Genome Atlas project, Gan Hualei for central review of the pathology results in FUSCC. This paper is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy.

Grant Support

This work was supported by National natural science foundation of China, (Grants No. 81502192 to Wan Fangning, 81472377, 81272837 to Ye Dingwei, 81370073 to Zhu Yao and 81202004 to Zhang Hailiang,). Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning grant (2014zyjb0102) to Dingwei Ye.

References

- 1.Buttner F, Winter S, Rausch S, Reustle A, Kruck S, Junker K, Survival Prediction of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Based on Gene Expression Similarity to the Proximal Tubule of the Nephron. European urology; 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang L, Li L, Zeng J, Gao Y, Chen YL, Wang ZQ. et al. Inhibitory effect of silibinin on EGFR signal-induced renal cell carcinoma progression via suppression of the EGFR/MMP-9 signaling pathway. Oncology reports. 2012;28:999–1005. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ficarra V, Martignoni G, Lohse C, Novara G, Pea M, Cavalleri S. et al. External validation of the Mayo Clinic Stage, Size, Grade and Necrosis (SSIGN) score to predict cancer specific survival using a European series of conventional renal cell carcinoma. The Journal of urology. 2006;175:1235–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00684-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank I, Blute ML, Cheville JC, Lohse CM, Weaver AL, Zincke H. An outcome prediction model for patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma treated with radical nephrectomy based on tumor stage, size, grade and necrosis: the SSIGN score. The Journal of urology. 2002;168:2395–400. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brannon AR, Reddy A, Seiler M, Arreola A, Moore DT, Pruthi RS. et al. Molecular Stratification of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma by Consensus Clustering Reveals Distinct Subtypes and Survival Patterns. Genes & cancer. 2010;1:152–63. doi: 10.1177/1947601909359929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks SA, Brannon AR, Parker JS, Fisher JC, Sen O, Kattan MW. et al. ClearCode34: A prognostic risk predictor for localized clear cell renal cell carcinoma. European urology. 2014;66:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thwaites DT, Anderson CM. The SLC36 family of proton-coupled amino acid transporters and their potential role in drug transport. British journal of pharmacology. 2011;164:1802–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hediger MA, Romero MF, Peng JB, Rolfs A, Takanaga H, Bruford EA. The ABCs of solute carriers: physiological, pathological and therapeutic implications of human membrane transport proteinsIntroduction. Pflugers Archiv: European journal of physiology. 2004;447:465–8. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1192-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCracken AN, Edinger AL. Targeting cancer metabolism at the plasma membrane by limiting amino acid access through SLC6A14. The Biochemical journal. 2015;470:e17–9. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu SL, Yang ZY, Zhou ZR, Yu XJ, Ping B, Zhang YJ. Role of SUV(max) obtained by 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with a solitary pancreatic lesion: predicting malignant potential and proliferation. Nuclear medicine communications. 2013;34:533–9. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e328360668a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang L, Wang X, Bullock AJ, Callea M, Shah H, Song J. et al. Anti-S1P Antibody as a Novel Therapeutic Strategy for VEGFR TKI-Resistant Renal Cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21:1925–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart GD, O'Mahony FC, Laird A, Eory L, Lubbock AL, Mackay A. et al. Sunitinib Treatment Exacerbates Intratumoral Heterogeneity in Metastatic Renal Cancer. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21:4212–23. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saeed AI, Sharov V, White J, Li J, Liang W, Bhagabati N. et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. BioTechniques. 2003;34:374–8. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Song B, Wang Y, Xi Y, Kudo K, Bruheim S, Botchkina GI. et al. Mechanism of chemoresistance mediated by miR-140 in human osteosarcoma and colon cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:4065–74. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyata M, Yamakawa H, Hamatsu M, Kuribayashi H, Takamatsu Y, Yamazoe Y. Enterobacteria modulate intestinal bile acid transport and homeostasis through apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (SLC10A2) expression. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2011;336:188–96. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.171736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jhaveri K, Linden H. Measuring tumor metabolism by 18F-FDG PET predicts outcome in a multicenter study: a step off in the right direction. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2015;56:1–2. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.151175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jong NN, McKeage MJ. Emerging roles of metal solute carriers in cancer mechanisms and treatment. Biopharmaceutics & drug disposition. 2014;35:450–62. doi: 10.1002/bdd.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Mattia E, Toffoli G, Polesel J, D'Andrea M, Corona G, Zagonel V. et al. Pharmacogenetics of ABC and SLC transporters in metastatic colorectal cancer patients receiving first-line FOLFIRI treatment. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2013;23:549–57. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328364b6cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohelnikova-Duchonova B, Brynychova V, Hlavac V, Kocik M, Oliverius M, Hlavsa J. et al. The association between the expression of solute carrier transporters and the prognosis of pancreatic cancer. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2013;72:669–82. doi: 10.1007/s00280-013-2246-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le Vee M, Jouan E, Noel G, Stieger B, Fardel O. Polarized location of SLC and ABC drug transporters in monolayer-cultured human hepatocytes. Toxicology in vitro: an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2015;29:938–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2015.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Claro da Silva T, Polli JE, Swaan PW. The solute carrier family 10 (SLC10): beyond bile acid transport. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2013;34:252–69. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lionarons DA, Boyer JL, Cai SY. Evolution of substrate specificity for the bile salt transporter ASBT (SLC10A2) Journal of lipid research. 2012;53:1535–42. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M025726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dranoff JA, Nathanson MH. Regulation of bile acid transport: beyond molecular cloning. Hepatology. 1999;29:1912–3. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rose AJ, Berriel Diaz M, Reimann A, Klement J, Walcher T, Krones-Herzig A. et al. Molecular control of systemic bile acid homeostasis by the liver glucocorticoid receptor. Cell metabolism. 2011;14:123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawson PA, Lan T, Rao A. Bile acid transporters. Journal of lipid research. 2009;50:2340–57. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900012-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma L, Juttner M, Kullak-Ublick GA, Eloranta JJ. Regulation of the gene encoding the intestinal bile acid transporter ASBT by the caudal-type homeobox proteins CDX1 and CDX2. American journal of physiology Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2012;302:G123–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00102.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables.