Abstract

Objective

To determine the prevalence and correlation of various risk factors [radiation dose, periodontal status, alcohol and smoking] to the development of osteoradionecrosis (ORN).

Patients and Methods

The records of 1023 patients treated with IMRT for oral cavity cancer (OCC) and oropharyngeal (OPC) between 2004 and 2013 were retrospectively reviewed to identify patients who developed ORN. Fisher exact tests were used to analyze patient characteristics between ORN patients with OCC and OPC. Paired Wilcoxon tests were used to compare the dose volumes to the ORN and contralateral non-ORN sites. To evaluate an association between ORN and risk factors, a case-control comparison was performed. One to 2 ORN-free patients were selected to match each ORN patient by gender, tumor site and size. General estimation equations models were used to compare the risk factors in ORN cases and matched controls.

Results

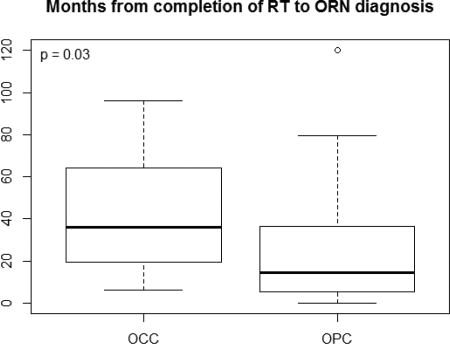

44 (4.3%) patients developed ORN during a median follow-up time of 52.5 months. In 82% of patients, ORN occurred spontaneously. Patients with OPC are prone to develop ORN earlier compared to patients with OCC (P=0.03). OPC patients received a higher Dmax compared to OCC patients (P=0.01). In the matched case-control analysis the significant risk factors on univariate analysis were poor periodontal status, history of alcohol use and radiation dose (P=0.03, 0.002 and 0.009, respectively) and on multivariate analysis were alcohol use and radiation dose (P=0.004 and 0.026, respectively).

Conclusion

In our study, higher radiation dose, poor periodontal status and alcohol use are significantly related to the risk of developing ORN.

Keywords: Osteoradionecrosis, Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, Oral cancer, Oropharyngeal cancer, Head and neck cancer, Prevalence, Risk factors

Introduction

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) of the jaw is a well-known complication of radiation therapy to the head and neck. ORN is defined as an area of exposed necrotic bone in an area previously irradiated that fails to heal over a period of 3–6 months. However, cases with radiographic evidence of necrosis with intact mucosa have been described [1–5].

Head and neck cancers are sensitive to radiotherapy (RT), which is being increasingly used with the rising prevalence of human papilloma virus positive squamous cell carcinoma. The treatment mainstay in these cases remains radiation therapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy [6, 7]. Since the advent of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in the treatment of head and neck cancer patients, the associated co-morbidities of radiation therapy have been minimized by limiting radiation exposure to healthy tissue and maximizing loco-regional tumor control [8–10]. Earlier studies looking at the rate of ORN in patients treated in the era of IMRT have reported a reduced prevalence compared to patients treated with conventional radiotherapy [11–14].

Various risk factors have been suggested to be associated with the development of ORN. The local risk factors include tumor site, tumor stage, proximity of the tumor to bone, radiation field, dose of radiation, poor oral hygiene, and associated trauma, such as dental extraction/surgery before or after RT. Systemic factors include co-morbidities, smoking and drinking alcohol, immunodeficient status, and infection [15– 20]. The aims of this study are: (1) to report the current prevalence of ORN in patients with oral cavity cancer (OCC) and oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) treated with IMRT between 2004 and 2013 in our institution; and (2) to evaluate the correlation between various risk factors [radiation dose, periodontal status, alcohol and smoking] and the development of ORN.

Patients and Methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s (MSKCC) Institutional Review Board. We reviewed the records of all oral cavity cancer (OCC) and oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) patients treated with IMRT in our institution between 2004 and 2013 to identify patients who developed ORN. ORN is defined as either clinically exposed necrotic bone that failed to heal over a period of 3 months or patients with radiographic evidence of necrosis with intact mucosa. The following clinical information was reviewed: demographic data, tumor site, tumor diagnosis, tumor stage, and radiation dose to the primary tumor, dental events, ORN stage, social history (alcohol and smoking history), history of diabetes mellitus, follow-up data, and management of patients who developed ORN.

Radiation treatment

All patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer diagnosed during the period of 2004 to 2013 were treated with IMRT using a dose-painting technique. All areas of gross disease received 66–70 Gy and regions of elective nodal radiation received 50–60 Gy. Uninvolved low anterior neck received 45–50 Gy. For patients receiving postoperative radiation, the dose to the surgical bed dose was typically 60 Gy.

Follow-up period

The follow-up period was calculated from the completion of RT to the patient’s last clinical visit with MSKCC’s Department of Radiation Oncology or Dental Service. Follow-up was calculated up until July 31, 2016. The follow-up period for all patients spans 4 – 140 months with a median time of 52.5 months. The time from completion of RT to ORN diagnosis was also noted.

ORN definition and grading

ORN is an area of clinically exposed necrotic bone that failed to heal over a period of 3–6 months in an area previously irradiated. However, there is a subset of ORN that presents with clinically intact mucosa along with radiographic evidence of bone loss [3–5]. We included both subsets in our cohort. For the sake of consistency with the literature we adopted a modified version of the Glanzmann and Graetz grading system [21].

The ORN grading (adopted modified Glanzmann and Graetz grading) used is as follows:

0 – Radiographic ORN with intact mucosa

1 – Exposed necrotic bone without signs of infection for at least 3 months

2 – Exposed necrotic bone with signs of infection or sequestrum, but not grades 3 – 4

3 – ORN resulting to pathologic fracture or ORN treated with surgical resection, with satisfactory result

4 – ORN refractory to surgical resection

Dosimetry of ORN site, contralateral non-ORN site and statistical analysis

Using the MSKCC radiation treatment planning software, the mean (Dmean) and maximum point radiation doses (Dmax) of the ORN region and contralateral non-ORN region of the jaw were calculated via dosimetric contour as previously described [22]. A case-control comparison was performed with one to two ORN-free patients selected to match each ORN patient by gender, primary tumor site and size. Statistical analysis was performed using generalized estimating equation logistic regression to compare the risk factors (radiation dose, pre-RT periodontal status, alcohol and smoking post-RT history) in ORN cases and matched controls. Fisher exact tests were used to analyze patient characteristics between ORN patients with oral cavity cancer (OCC) and oropharyngeal cancer (OPC). Paired Wilcoxon tests were used to compare the dose volumes (Dmean and Dmax) to the ORN and contralateral non-ORN sites in patients who developed ORN unilaterally.

Dental evaluation and management of ORN

Patients referred to the Dental Service of MSKCC prior to radiation therapy underwent comprehensive clinical and radiographic evaluation and dental intervention if indicated. Pre-radiation whole-mouth saliva and inter-incisal opening measurements were obtained. Radiation mouth guards were fabricated for patients to help reduce the dose and toxicity from backscatters in patients with significant metal dental restorations. All patients were prescribed aggressive fluoride regimen. Patients were evaluated at mid-RT, and at various time points post-RT.

Conservative management through close observation, prescription of 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse for local debridement, antibiotics (typically, Augmentin 875 mg BID) and pain medication when indicated were utilized. Subsequently, if the exposed necrotic bone becomes increasingly mobile, the sequestrum was passively removed [treatment option I]. Pentoxifylline 400 mg and tocopherol 400 IU BID were prescribed to some patients in combination with 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse for local debridement [treatment option II]. Segmental mandibulectomy was employed after all other treatment options failed and the lesions progressed to involve the basal bone of the mandible and/or had a pathologic fracture [treatment option III]. Hyperbaric oxygen was instituted in one patient for management of ORN [treatment option IV]. Outcomes of management were assessed in four categories: complete resolution (complete mucosal coverage of prior exposed bone), partial resolution (reduction in size of exposed bone), no resolution and progression (increase in size of exposed bone).

Results

Clinical analysis and prevalence

Between January 2004 and December 2013, 1023 oral cavity (OCC; n=299) cancer and oropharyngeal cancer (OPC; n=724) patients were treated with IMRT in our institution. The medical and dental records of all 1023 patients were reviewed. Forty-four (4.3%) patients treated within that time-period developed ORN. Thirty-two (4.4%) of these had a diagnosis of OPC and 12 (4%) had OCC. Thirty-six patients presented with clinical ORN “clinically exposed necrotic bone” and eight patients with “radiographic ORN” with intact mucosa. If cases of radiographic ORN with intact mucosa were excluded, the rate of ORN would be 36/1023 (3.5%). Of the patients that developed ORN, 34 were males, 10 were females, with ages ranging from 20 to 82 (median 59.5 years). Most patients consumed alcohol semi-regularly or regularly (33/44, 75%) and 11/44 (25%) were active smokers at the time of development of ORN. One patient had a medical history of diabetes mellitus.

Primary tumor sites were base of tongue (n=18, 41%), tonsil (n=14, 32%), floor of mouth (n=4, 9%), oral tongue (n=6, 14%), buccal mucosa (n=1, 2%) and gingiva (n=1, 2%). One patient had adenoid cystic carcinoma (2%) and the remaining patients had squamous cell carcinoma (98%). Tumor sizes were: T1 (n=11, 25%), T2 (n=18, 41%), T3 (n=5, 11%), T4 (n=9, 20%) and nodal status were: N0 (n=5, 11%), N1-2B (n=32, 73%), N2C (n=4, 9%) and N3 (n=2, 5%). The majority of the patients had a tumor stage IVA (n=29, 66%), followed by stage III (n=8, 18%).

Posterior mandible is the most common site, OPC patients are prone to develop ORN earlier compared to OCC patients

The mandible was involved in all 44 ORN patients. One patient developed ORN in both ipsilateral posterior mandible and posterior maxilla and three patients developed ORN in both contralateral sites of the posterior mandible, making a total of 48 ORN sites (47 mandibular sites and 1 maxillary site). ORN cases were found in the posterior region with the exception of an anterior mandibular site. The median time from completion of RT to the diagnosis of ORN was 19.1 months (range: 0 – 120.2 months). The median duration was longer in patients with OCC compared to patients with OPC (36.1 vs. 14.6 months) [P=0.03]. ORN occurred spontaneously (i.e without history of trauma or dentoalveolar procedures) in 36 of 44 (82%) patients. ORN occurred spontaneously in 26/32 (81%) OPC patients and 10/12 (83%) of OCC patients (P=1.00). Six patients had post-radiation dental extraction and two underwent extractions 4 weeks before beginning RT (two OCC and six OPC patients). The grades of ORN were: grade 0 (8, 18%), grade 1 (6, 14%), grade 2 (22, 50%) and grade 3 (8, 18%). Four of the grade 3 ORN cases had pathologic fractures. The four patients with pathologic fracture had tumor stages of T4AN1, T4AN0, T3N1 and T1N1. Three of the eight patients with grade 3 ORN had dental extractions as a precipitating factor. A summary of the patient characteristics and comparison of time to ORN between the OCC and OPC groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (n = 44)

| Characteristics | OCC (%∞) n=12 |

OPC (%∞) n=32 |

Total (%∞) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age yrs (median, range) | 59 (20,82) | 60 (39,74) | 59.5 (20,82) | 0.99 |

|

| ||||

| Gender | 0.42 | |||

| Male | 8 (67) | 26 (81) | 34 (77) | |

| Female | 4 (33) | 6 (19) | 10 (23) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor site | ||||

| Tonsil | - | 14 | 14 (32) | |

| Base of Tongue | - | 18 | 18 (41) | |

| Floor of mouth | 4 | - | 4 (9) | |

| Oral Tongue | 6 | - | 6 (14) | |

| Buccal mucosa | 1 | - | 1 (2) | |

| Gingiva | 1 | - | 1 (2) | |

|

| ||||

| Pathologic diagnosis | 0.27 | |||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 11 (92) | 32 (100) | 43 (98) | |

| Adenoid cystic carcinoma | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

|

| ||||

| T classification* | 0.59 | |||

| T1 | 5 (42) | 6 (19) | 11 (26) | |

| T2 | 4 (33) | 14 (45) | 18 (42) | |

| T3 | 1 (8) | 4 (13) | 5 (12) | |

| T4 | 2 (17) | 7 (23) | 9 (21) | |

|

| ||||

| N classification* | <0.001 | |||

| N0 | 5 (42) | 0 (0) | 5 (12) | |

| N1-2B | 6 (50) | 26 (84) | 32 (74) | |

| N2C | 0 (0) | 4 (13) | 4 (9) | |

| N3 | 1 (8) | 1 (3) | 2 (5) | |

|

| ||||

| Tumor stage* | ||||

| Stage I | 1 | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Stage II | 2 | 0 | 2 (5) | |

| Stage III | 4 | 4 | 8 (19) | |

| Stage IVA | 4 | 25 | 29 (67) | |

| Stage IVB | 1 | 2 | 3 (7) | |

|

| ||||

| Radiation to the primary tumor site | <0.001 | |||

| ≥70 Gy | 2 (17) | 32 (100) | 34 (77) | |

| ≥66 Gy, <70 Gy | 7 (58) | 0 | 7 (16) | |

| ≥60 Gy, <66 Gy | 3 (25) | 0 | 3 (7) | |

|

| ||||

| Max radiation dose (Gy) to ORN site (n=42) | 0.01 | |||

| Median (range) | 67.4 (60.7, 74.9) | 72.7 (44.3, 80.9) | 70.6 (44.3, 80.9) | |

|

| ||||

| Mean radiation dose (Gy) to ORN site (n=42) | 0.52 | |||

| Median (range) | 61.6 (47.2, 62.9) | 58.3 (28.2,74.6) | 59.4 (28.2, 74.6) | |

|

| ||||

| ORN (sites) patients | 0.27 | |||

| Anterior Mandible | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| Posterior Mandible | 11 (92) | 32 (100) | 43 (98) | |

|

| ||||

| Clinical/Radiographic ORN | 0.66 | |||

| Clinical ORN | 9 (75) | 27 (84) | 36 (82) | |

| Radiographic ORN | 3 (25) | 5 (16) | 8 (18) | |

|

| ||||

| Duration (mos.) from completion of RT to ORN diagnosis | 0.03 | |||

| Median (range) | 36.1 (6.2,96.2) | 14.6 (0,120.2) | 19.1 (0,120.2) | |

|

| ||||

| ORN Grade | 0.30 | |||

| Grade 0 | 3 (25) | 5 (16) | 8 (18) | |

| Grade 1 | 1 (8) | 5 (16) | 6 (14) | |

| Grade 2 | 4 (33) | 18 (56) | 22 (50) | |

| Grade 3 | 4 (33) | 4 (12) | 8 (18) | |

|

| ||||

| Trigger | 1.00 | |||

| Spontaneous | 10 (83) | 26 (81) | 36 (82) | |

| Extraction | 2 (17) | 6 (19) | 8 (18) | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking | 0.66 | |||

| Current | 2 (17) | 9 (28) | 11 (25) | |

| Former | 8 (66) | 16 (50) | 24 (55) | |

| Never | 2 (17) | 7 (22) | 9 (20) | |

|

| ||||

| Alcohol use | 0.62 | |||

| Current | 8 (66) | 25 (78) | 33 (75) | |

| Former | 2 (17) | 4 (13) | 6 (14) | |

| Never | 2 (17) | 3 (9) | 5 (11) | |

|

| ||||

| Follow-up period (months) | 0.18 | |||

| Median (range) | 63.2 (27.4,118.3) | 50.4 (4.1,140.3) | 52.5 (4.1,140.3) | |

43 patients assessed,

Percentages approximated

Dmax of ORN patients with OPC was significantly higher compared to ORN patients with OCC, majority of ORN patients received >60 Gy to the ORN site

All patients who developed ORN received ≥ 60 Gy of radiation to the primary tumor site. The majority of patients (34/44, 77%) received ≥ 70Gy of radiation to the primary tumor site, 7 patients had ≥ 66 < 70 Gy and 3 patients received ≥ 60 < 66 Gy. Dosimetric analysis was conducted in 42 patients (dosimetric data for the other two patients were not available). The Dmax calculated in the ORN region of the jaw ranged from 44.3 – 80.9 Gy (average=69.9 Gy). While, the Dmean calculated in the ORN region of the jaw ranged from 28.2 – 74.6 Gy (average=57.4 Gy). The median and mean Dmax difference between the ORN and contralateral non-ORN regions were 6.1(0.8, 23.9) Gy and 13.2(7.4, 18.9) Gy (P< 0.000004), respectively. The median and mean Dmean difference between the ORN and contralateral non-ORN regions were 13.5(1.2, 28.4) Gy and 14.6(8.3, 20.9) Gy (P< 0.000012), respectively (Table 2). The Dmax of ORN patients with OPC was significantly higher compared to ORN patients with OCC (P=0.01). The ORN regions of the jaw received radiation doses >60 Gy in 96% (44/46). Seven patients had higher Dmax in the non-ORN site compared to the ORN site. The primary tumor site coincided with non-ORN site in three OPC patients, in an OPC patient (T2N2C) the bilateral neck was radiated and the remaining three patients were treated for oral tongue cancer. Patients with grade 3 ORN had an average Dmax of 71.4 Gy (range: 60.7–78.4 Gy).

Table 2.

Difference in dosimetry between ORN site and contralateral site (N = 39)

| Dose measurement | Median Difference (IQR) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum dose(Gy) | 6.1 (.8, 23.9) | 13.2 (7.4, 18.9) | 0.000004 |

| Mean dose(Gy) | 13.5 (1.2, 28.4) | 14.6 (8.3, 20.9) | 0.000012 |

P-values calculated with paired Wilcoxon tests.

By univariate analysis poor periodontal status, alcohol use post-RT and high mean radiation dose were significant factor and by multivariate analysis alcohol use post-RT and high mean radiation dose remained significant

Thirty-nine ORN patients were matched with 78 ORN-free patients based on primary tumor site, tumor size, gender and age. Patient matching characteristics are presented in online Supplemental Table 1. For periodontal status, patient pre-RT panoramic radiograph were scored 0 – 3 (0 = no bone loss, 1 = mild bone loss, 2 = moderate bone loss, 3 = severe bone loss). Pre-RT radiographs were available for 18 ORN patients and matched with 36 controls. Smoking and alcohol history after completion of RT were retrieved in 39 ORN patients and matched with 78 controls. The Dmean to the ORN sites in 37 ORN patients were matched to the Dmean to the ipsilateral molar region in 74 ORN-free controls. Matched patient prognostic characteristics are presented in online Supplemental Table 2. By univariate analysis (Odds Ratio, 95% CI, P-value), for periodontal status (≥1 vs 0) (5.71, 1.2 – 27.1, 0.03), current smoking history post-RT (3.04, 0.93 – 9.91, 0.07), current alcohol history post-RT (3.38, 1.57 – 7.29, 0.002) and mean radiation dose (1.07, 1.02 – 1.13, 0.009). By multivariate analysis (Odds Ratio, 95% CI, P), alcohol use and radiation dose remained significant (3.22, 1.47 – 7.07, 0.004 and 1.07, 1.01 – 1.13, 0.026, respectively). The odds of developing ORN for post-RT alcohol drinkers are 3.22 times the odds of nondrinkers, keeping radiation dose constant. On average there is a 7% increase in the odds of developing ORN for a 1 Gy increase in radiation dose, keeping alcohol status constant. Univariate and multivariate analysis presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3.

Univariate GEE Logistic Regression

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| T stage | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) | 0.40 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.89 |

|

| ||

| Periodontal Status: ≥1 vs 0 (n = 18 cases, 36 controls) | 5.71 (1.2, 27.1) | 0.03 |

| Current smoking: yes vs. no | 3.04 (0.93, 9.91) | 0.07 |

| Current alcohol: yes vs. no | 3.38 (1.57, 7.29) | 0.002 |

| Mean Radiation Dose (Gy) (n = 37 cases, 74 controls) | 1.07 (1.02, 1.13) | 0.009 |

Table 4.

Multivariate GEE Logistic Regression (n = 37 cases, 74 controls)

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Current alcohol: yes vs. no | 3.22 (1.47, 7.07) | 0.004 |

| Mean Radiation Dose (Gy) (n = 37 cases, 74 controls) | 1.07 (1.01, 1.13) | 0.026 |

Keeping mean radiation dose constant, the odds of developing ORN for current alcohol drinkers are 3.22 times the odds for non-current alcohol drinkers. Holding current alcohol status constant, there is on average a 7% increase in the odds of developing ORN for a one-unit increase in radiation dose Gy.

Patients with grade 0 ORN “radiographic ORN” (n=8) were managed with 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse, antibiotics and pain medication when indicated. Of the 36 patients who developed clinical ORN “clinically exposed necrotic bone” only 27 patients have follow-up information after commencement of management of ORN. Fourteen patients received treatment option I, outcomes as at last follow-up were: complete resolution (n=10), partial resolution (n=1), no resolution (n=2) and progression (n=1, pathologic fracture). Six patients received treatment option II, outcomes as at last follow-up were: complete resolution (n=1), partial resolution (n=4) and progression (n=1, requiring segmental mandibulectomy). Seven patients received treatment option III, outcome was: complete resolution (n=7) (Figure 1). One patient was managed with hyperbaric oxygen and 0.12% chlorhexidine rinse. The patient achieved complete resolution of ORN after 80 dives of hyperbaric oxygen (40 dives before extraction and 40 dives after extraction). Therapeutic outcomes of patients by ORN stage and therapy options are presented in Table 5.

Figure 1.

Clinical pictures and radiographs of a patient who underwent partial mandibulectomy for the management of a grade 3 ORN. Pre-radiation cropped panoramic radiograph (A), Post-radiation cropped panoramic radiographs showing an area of ORN with pathologic fracture (B), Pre-surgrey extraoral picture showing the reduced maximal mouth opening of the patient (C), Pre-surgery intraoral picture (D), Post-surgery panoramic radiograph (E), Post-surgery extraoral picture (F) and Post-surgery intraoral picture (G)

Table 5.

Therapeutic outcomes of patients by ORN stage and therapy options

| ORN stage | Therapy options instituted (n) | Outcomes (n) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1 | Option 1 (4) | CR (4) |

|

| ||

| 2 | Option 1 (9) | CR (6), PR (1) and NR (2) |

| Option 2 (5) | CR (1) and PR (4) | |

| Option 4 (1) | CR (1) | |

|

| ||

| 3 | Option 1 (1) | P (1) |

| Option 2 → 3 (1) | P → CR (1) | |

| Option 3 (6) | CR (6) | |

CR – complete resolution, PR – partial resolution, NR – no resolution, P - progressed

Discussion

Of 1023 patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer treated with IMRT during a 10-year period, 44 patients (4.3%) developed ORN over a median follow-up of 52.5 months (range: 4.1 – 140.3 months). The majority (36, 82%) of the ORN lesions occurred spontaneously without any precipitating trauma or dental events. Six patients (0.78%) developed grade 3 ORN, requiring mandibular resection and/or complicated by pathologic fracture.

Earlier studies focusing on patients treated with IMRT for head and neck cancers reported very low prevalence of ORN. Studies by Ben-David et al. reported the lack of ORN in 176 patients treated with IMRT at a median follow-up of 34 months [11]. Also, studies by Studer et al. and Huang et al., reported only 1 patient in both studies developing ORN in 204 and 71 patients treated with IMRT, respectively [12, 13]. In a similar study from our institution, only 2 out of 168 patients developed ORN, with a median follow-up of 37.4 months [14]. However, recent studies with larger patient sample have reported higher prevalence of ORN; 21/334 (6.3%) and 36/531 (6.8%) patients developing ORN in patients treated with IMRT at a median follow-up of 31 months in patients treated for T1/T2 and mean follow-up of 38 months, respectively [23, 24].

The prevalence of ORN has decreased from 11.8% before 1968 to 5.4% between 1968 and 1992 and to 3% after 1997 [18]. Reduction in the prevalence of ORN can be attributed to the evolution of radiation therapy modalities from conventional/2-D RT to 3-D conformal RT to the current use of IMRT. The study by Tsai et al. demonstrated a reduction in ORN from 13% to 6% comparing 3-D conformal RT to IMRT [23]. Proton beam radiation therapy / intensity modulated proton therapy (PBRT/IMPT) are now been utilized in the management of head and neck cancers [25–27]. Recent studies have shown that PBRT has a greater tissue-sparing capability in comparison to IMRT due to its inert property of the Bragg peak [27, 28]. Therefore, could reduce the rate of radiation-related toxicities. Our recent study, comparing the mean radiation dose and dosimetric distribution to the mandible in patients treated for ipsilateral head and neck tumors between PBRT versus IMRT shows that PBRT has a far-better tissue-sparing capability compared to IMRT and the mean radiation dose to the contralateral side of the mandible received zero - negligible dose of radiation [28].

To answer the question of our second aim, we dosimetrically contoured the ORN site to calculate the Dmean and Dmax, reviewed the patients alcohol and smoking history post-RT and evaluated the patient pre-RT panoramic radiographs to assess the periodontal status. Chang et al. stated that radiation doses greater or equal to 70 Gy were predictive of ORN [29]. Similarly, Gomez et al., claimed that maximum doses greater than 70 Gy and mean doses greater than 40 Gy were predictive of increased subsequent dental events and extractions [14]. The study by Tsai et al., suggested that reducing the radiation dose below 50 Gy may lessen the risk of ORN [23]. These previous studies evaluated the whole mandible calculating the Dmean and Dmax received by the mandible, however, in our study we contoured the specific ORN site. After dosimetrically analyzing the ORN site it revealed an average Dmax of 69.9 Gy (range: 44.3–80.9 Gy) and the average Dmean to the region was 57.4 Gy (range: 28.2–74.6 Gy). The ORN-affected regions of the jaw in this study received over 60 Gy in 96%, suggesting >60 Gy as a threshold for ORN risk, in keeping with previous literature [30]. In this cohort of ORN patients, the radiation dose to the ORN-affected regions received a significantly higher dose compared to the contralateral non-ORN regions. Also, the mean radiation dose to the ORN site was significantly higher compared to the mean radiation dose of the ipsilateral molar region in ORN-free controls with a 7% increase in the odds of developing ORN for a Gy unit of radiation dose.

Poor dental health has been implicated as a risk factor in the development of ORN. Patients with post-RT dental extractions are at an increased risk of developing ORN [20, 31–33]. However, in this study 82% of the patients who developed ORN had no prior traumatic event or dentoalveolar procedure prior to development of ORN. By univariate analysis poor periodontal status predispose patients to the development of ORN. These findings highlight the importance of close surveillance and follow-up visits after completion of RT. As such, at MSKCC, all patients scheduled to undergo head and neck RT are referred to the Dental Service for evaluation. During this visit, a thorough oral and dental evaluation is performed including panoramic and bitewing radiographs (and selected periapical radiographs as needed) and measurement of resting and stimulated salivary function and interincisal mouth opening. Treatment of dental caries and periodontal disease is initiated as soon as possible. Dental extractions are completed at least 10–14 days prior to commencement of RT. Patients are counseled regarding the potential oral/dental effects and complications of RT. In addition, patients are provided detailed oral hygiene instructions and nutritional counseling. Prescription is issued for high-potency fluoridated toothpaste. The patients are then followed once during mid-treatment and periodically (every 4 months for the first 2 years and biannually, thereafter) after completion of RT.

Our study identified that patients with oropharyngeal cancer are prone to develop ORN earlier than patients with oral cavity cancer (P=0.03). This difference may be explained by the significantly higher Dmax of ORN patients with OPC compared to ORN patients with OCC (P=0.01). Patients with OCC are usually treated with surgical resection followed by adjuvant RT. In contrast, OPC are treated primarily with concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Thus, the total dose to the primary site is typically lower in patients with OPC compared to those with OCC.

Continual smoking and alcohol use have been shown to increase the risk of ORN in irradiated patients. The study by Tsai et al. demonstrated a 32% increased risk of development of ORN in smokers [23]. Oh et al. demonstrated that patients who continued smoking or alcohol use are at risk of failing conservative management and are more prone to having a surgical intervention [17]. A recent study by Chronopoulos et al. showed that patients who continued smoking or alcohol use were more likely to develop a severe grade of ORN [19]. In our study 75% of patients with ORN still continued alcohol use and 25% continued smoking. Patients that continued to drink alcohol after radiation were predisposed to develop ORN and are 3.22 times more likely to develop ORN compared to non-drinkers.

In this study we included cases of radiographic ORN with intact mucosa, a subset of ORN that is underdiagnosed due to the absence of clinical bone exposure [3–5]. This subset of ORN can be complicated by tooth mobility, tooth loss and even pathologic fracture [5]. It is important to have this subset in a staging system. A clinical guideline for the early identification of this condition was proposed [5]. The same proposal can also be applied to clinical ORN aiding its early identification.

Conclusion

In summary, 4.3% of 1023 oral and oropharyngeal cancer patients treated with IMRT over a ten-year period developed ORN during a median follow-up of 52.5 months. The prevalence of ORN in this study is comparable to recent reports of ORN in the setting of IMRT. The average Dmax to the ORN sites contoured was 69.9 Gy and in 96% of ORN sites dosimetrically contoured received over 60 Gy suggesting that radiation doses >60 Gy to the bone is positively related to the risk of developing ORN. Patients with OPC were shown to develop ORN earlier compared to patients with OCC. ORN can occur spontaneously without any precipitating dentoalveolar trauma. Radiation dose to the jaw > 60Gy, poor periodontal status and alcohol use after RT are significantly related to the risk of developing ORN.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

-

The prevalence of ORN in OCC & OPC patients treated with IMRT is 4.3%

-

-

OPC patients are prone to develop ORN earlier compared to OCC patients

-

-

High radiation dose, poor periodontal status and alcohol use are associated with ORN

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: All authors declare that there are no financial conflicts associated with this study and that the funding source has no role in conceiving and performing the study.

References

- 1.Marx RE. Osteoradionecrosis: a new concept of its pathophysiology. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1983;41:283–8. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein JB, Wong FL, Stevenson-Moore P. Osteoradionecrosis: clinical experience and a proposal for classification. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;45:104–10. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(87)90399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Store G, Boysen M. Mandibular osteoradionecrosis: clinical behaviour and diagnostic aspects. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25:378–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He Y, Liu Z, Tian Z, Dai T, Qiu W, Zhang Z. Retrospective analysis of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible: proposing a novel clinical classification and staging system. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:1547–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Owosho AA, Kadempour A, Yom SK, Randazzo J, Jillian Tsai C, Lee NY, et al. Radiographic osteoradionecrosis of the jaw with intact mucosa: Proposal of clinical guidelines for early identification of this condition. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:e93–6. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kimple RJ, Harari PM. Is radiation dose reduction the right answer for HPV-positive head and neck cancer? Oral Oncol. 2014;50:560–4. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen AM, Zahra T, Daly ME, Farwell DG, Luu Q, Gandour-Edwards R, et al. Definitive radiation therapy without chemotherapy for human papillomavirus-positive head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2013;35:1652–6. doi: 10.1002/hed.23209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lohia S, Rajapurkar M, Nguyen SA, Sharma AK, Gillespie MB, Day TA. A comparison of outcomes using intensity-modulated radiation therapy and 3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy in treatment of oropharyngeal cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140:331–7. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.6777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Setton J, Caria N, Romanyshyn J, Koutcher L, Wolden SL, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy in the treatment of oropharyngeal cancer: an update of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82:291–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vergeer MR, Doornaert PA, Rietveld DH, Leemans CR, Slotman BJ, Langendijk JA. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy reduces radiation-induced morbidity and improves health-related quality of life: results of a nonrandomized prospective study using a standardized follow-up program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.07.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben-David MA, Diamante M, Radawski JD, Vineberg KA, Stroup C, Murdoch-Kinch CA, et al. Lack of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible after intensity-modulated radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: likely contributions of both dental care and improved dose distributions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.11.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Studer G, Graetz KW, Glanzmann C. In response to Dr. Merav A. Ben-David et al. ("Lack of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible after IMRT," Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007:In Press) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;68:1583–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang K, Xia P, Chuang C, Weinberg V, Glastonbury CM, Eisele DW, et al. Intensity-modulated chemoradiation for treatment of stage III and IV oropharyngeal carcinoma: the University of California-San Francisco experience. Cancer. 2008;113:497–507. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez DR, Estilo CL, Wolden SL, Zelefsky MJ, Kraus DH, Wong RJ, et al. Correlation of osteoradionecrosis and dental events with dosimetric parameters in intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:e207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee IJ, Koom WS, Lee CG, Kim YB, Yoo SW, Keum KC, et al. Risk factors and dose-effect relationship for mandibular osteoradionecrosis in oral and oropharyngeal cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1084–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mendenhall WM. Mandibular osteoradionecrosis. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4867–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oh HK, Chambers MS, Martin JW, Lim HJ, Park HJ. Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible: treatment outcomes and factors influencing the progress of osteoradionecrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1378–86. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahl MJ. Osteoradionecrosis prevention myths. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:661–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chronopoulos A, Zarra T, Troltzsch M, Mahaini S, Ehrenfeld M, Otto S. Osteoradionecrosis of the mandible: A ten year single-center retrospective study. J Cranio-maxillo-facial Surg. 2015;43:837–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo TJ, Leung CM, Chang HS, Wu CN, Chen WL, Chen GJ, et al. Jaw osteoradionecrosis and dental extraction after head and neck radiotherapy: A nationwide population-based retrospective study in Taiwan. Oral Oncol. 2016;56:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glanzmann C, Gratz KW. Radionecrosis of the mandibula: a retrospective analysis of the incidence and risk factors. Radiother Oncol. 1995;36:94–100. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(95)01583-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansen HJ, Maritim B, Bohle GC, 3rd, Lee NY, Huryn JM, Estilo CL. Dosimetric distribution to the tooth-bearing regions of the mandible following intensity-modulated radiation therapy for base of tongue cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;114:e50–4. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai CJ, Hofstede TM, Sturgis EM, Garden AS, Lindberg ME, Wei Q, et al. Osteoradionecrosis and radiation dose to the mandible in patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:415–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Studer G, Bredell M, Studer S, Huber G, Glanzmann C. Risk profile for osteoradionecrosis of the mandible in the IMRT era. Strahlenther Onkol. 2016;192:32–9. doi: 10.1007/s00066-015-0875-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozak KR, Adams J, Krejcarek SJ, Tarbell NJ, Yock TI. A dosimetric comparison of proton and intensity-modulated photon radiotherapy for pediatric parameningeal rhabdomyosarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:179–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simone CB, 2nd, Ly D, Dan TD, Ondos J, Ning H, Belard A, et al. Comparison of intensity-modulated radiotherapy, adaptive radiotherapy, proton radiotherapy, and adaptive proton radiotherapy for treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101:376–82. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romesser PB, Cahlon O, Scher E, Zhou Y, Berry SL, Rybkin A, et al. Proton beam radiation therapy results in significantly reduced toxicity compared with intensity-modulated radiation therapy for head and neck tumors that require ipsilateral radiation. Radiother Oncol. 2016;118:286–92. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owosho AA, Yom SK, Han Z, Sine K, Lee NY, Huryn JM, et al. Comparison of mean radiation dose and dosimetric distribution to tooth-bearing regions of the mandible associated with proton beam radiation therapy and intensity-modulated radiation therapy for ipsilateral head and neck tumor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang DT, Sandow PR, Morris CG, Hollander R, Scarborough L, Amdur RJ, et al. Do pre-irradiation dental extractions reduce the risk of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible? Head Neck. 2007;29:528–36. doi: 10.1002/hed.20538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Studer G, Gratz KW, Glanzmann C. Osteoradionecrosis of the mandibula in patients treated with different fractionations. Strahlenther Onkol. 2004;180:233–40. doi: 10.1007/s00066-004-1171-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thorn JJ, Hansen HS, Specht L, Bastholt L. Osteoradionecrosis of the jaws: clinical characteristics and relation to the field of irradiation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:1088–93. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.9562. discussion 93-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray CG, Herson J, Daly TE, Zimmerman S. Radiation necrosis of the mandible: a 10 year study. Part I. Factors influencing the onset of necrosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1980;6:543–8. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(80)90380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray CG, Herson J, Daly TE, Zimmerman S. Radiation necrosis of the mandible: a 10 year study. Part II. Dental factors; onset, duration and management of necrosis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1980;6:549–53. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(80)90381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.