Abstract

Background

Renal cell carcinoma forming a venous tumor thrombus (VTT) in the inferior vena cava (IVC) has a poor prognosis. Recent investigations have been focused on prognostic markers of survival. Thrombus consistency (TC) has been proposed to be of significant value but yet there are conflicting data. The aim of this study is to test the effect of IVC VTT consistency on cancer specific survival (CSS) in a multi-institutional cohort.

Methods

The records of 413 patients collected by the International Renal Cell Carcinoma-Venous Thrombus Consortium were retrospectively analyzed. All patients underwent radical nephrectomy and tumor thrombectomy. Kaplan-Meier estimates and Cox regression analyses investigated the impact of TC on CSS in addition to established clinicopathological predictors.

Results

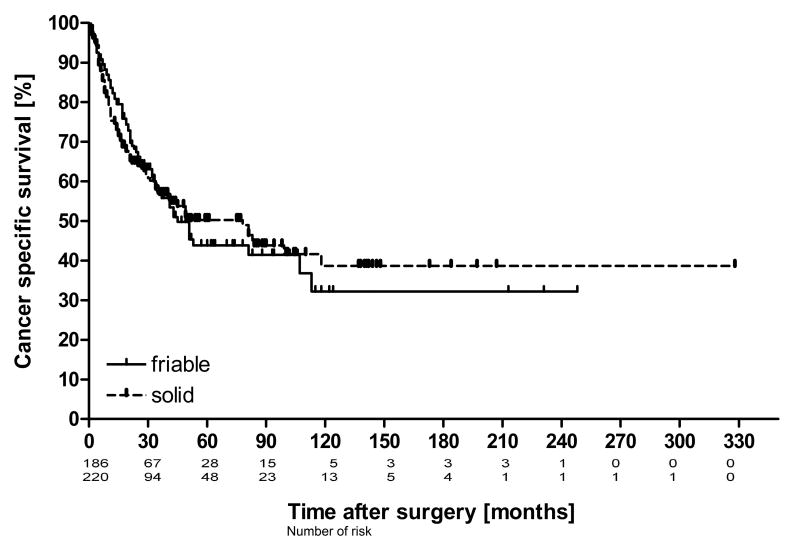

VTT was solid in 225 patients and friable in 188 patients. Median CSS was 50 months in solid and 45 months in friable VTT. TC showed no significant association with metastatic spread, pT stage, perinephric fat invasion and higher Fuhrman grade. Survival analysis and Cox regression rejected thrombus consistency as prognostic marker for CSS.

Conclusions

In the largest cohort published so far, TC seems not to be independently associated with survival in RCC patients and should therefore not be included in risk stratification models.

Keywords: Venous tumor thrombus, Renal cell carcinoma, Thrombus consistency, Cancer specific survival

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) represents roughly 3% of cancers worldwide [1] and its estimated incidence is approximately 12/100000 in the US and Europe [2,3]. In 4-10% of patients RCC forms a venous tumor thrombus (VTT) and invades the inferior vena cava [4] (IVC). VTT is considered to be an independent adverse prognostic parameter [5]. Although approximately 44% of patients with RCC and VTT present with synchronous metastases resulting in a reduced 5-year CSS between 17% and 36% surgery remains the first treatment option [6]. In those cases nephrectomy plus thrombectomy may result in improved survival and better effect of subsequent targeted therapy [7,8]. Recently, tumor thrombus consistency gained attention for its prognostic value:

In a retrospective study cohort of 174 patients, friable thrombus consistency was an independent predictor of survival and was associated with a significantly poorer CSS and overall survival (OS) [9].

At present two studies have been published trying to validate these results: A retrospective analysis of 200 patients confirmed significantly shorter OS for patients with friable thrombus consistency but failed to demonstrate significance of thrombus consistency in predicting survival independently. Solely in the subgroup of non-metastasized patients thrombus consistency was of predictive value [10].

Conversely, in another cohort of 147 patients thrombus consistency was not related to survival [11].

Given these apparent controversies, we aimed to evaluate the prognostic effect of tumor thrombus consistency in patients with IVC involvement in the largest multi-institutional cohort of IVC patients available.

Material and methods

Patients

The patients of our study were collected retrospectively by the International Renal Cell Carcinoma-Venous Thrombus Consortium (IRCCVTC). Prior to data collection all of the participating centers provided local ethics committee approval for their site. Data were submitted according to the IRCCVTC criteria and were cleared for data inconsistencies [12,13]. We retrospectively enrolled 477 patients who underwent radical nephrectomy and IVC tumor thrombectomy of hard or elastic VTT from 1975 to 2014 in 16 European und US centers. Patient records incomplete for tumor thrombus level, TNM staging, Fuhrman grade and perinephric fat invasion were excluded from analysis.

Definition of variables

Thrombus consistency was classified binarily as friable or solid depending on the surgeon's intraoperative discovery of pliable and slithery or hard and barely compressible thrombotic tissue.

Thrombus level was defined according to Mayo classification [14]. Only inferior vena cava tumor thrombus patients (level I-IV) were part of the study. TNM staging corresponded to the 2009 system [15]. Renal cell carcinomas were of clear cell, papillary or chromophobe histological subtype [16]. Other renal neoplasms were excluded from study cohort [17]. Type 1 and 2 papillary RCC were not distinguished.

Follow up

Follow-up was conducted according to local standards. Date of last follow-up and date of death was available for survival analysis. Cause of death was specified to distinguish cancer specific from cancer independent death.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of IVC tumor thrombus consistency in categorical clinicopathological variables was assessed using Chi square test or Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were analyzed by T test. Survival was calculated from the date of surgery to last follow-up or death. Tumor-independent death was censored. Survival analysis was performed with Kaplan-Meier estimates and variables were compared using log rank test according to Peto-Pike. The clinicopathologic variables thrombus consistency, thrombus level, pT stage, presence of metastasis, Fuhrman grade and perinephric fat invasion were selected for evaluation of their prognostic significance on cancer specific survival. To assess the variable's impact on survival univariable and multivariable analysis were performed using Cox proportional hazard regression model. All tests were two-sided and a p value of p<0.05 was considered significant. Data were analyzed using Bias software (epsilon, Frankfurt, Germany) [18].

Results

Of 477 patients enrolled, 413 patients fulfilled all aforementioned criteria and were available for analysis. There were 225 patients (54%) with solid and 188 patients (46%) with friable tumor thrombus in the inferior vena cava. Clinical and pathological features separated for solid and friable tumor thrombus consistency are shown in Table 1. Neither friable nor solid tumor thrombus showed significant association with the histological subtype, presence of nodal or distant metastases, pT stage, and higher Fuhrman grade, IVC wall invasion or perinephric fat invasion. The median cancer specific survival of the whole study cohort was 50 months (range 0 -328 months). Over the analyzed period of 32 years cancer specific death occurred in 172 patients (42%). 5-year cancer specific survival probability was 47.6%. Kaplan-Meier curves of cancer specific survival in patients with friable and solid caval tumor thrombus are presented in Figure 1. Clinicopathologic variables and their influence on survival are shown in Table 2. Log rank test revealed no significant difference in cancer specific survival between patients with friable or solid IVC tumor thrombus. There were significant differences in survival rates between patients with and without a positive nodal status, distant metastasis, perinephric fat invasion and IVC wall invasion. Metastatic disease had a poor 5-year CSS of 26% significantly different from non-metastatic disease with 62% [HR = 3.1, CI: (2.4, 4.2), log rank test]. In univariable Cox regression analysis thrombus consistency failed to be of significance in prediction of cancer specific survival, whereas all other selected variables pretended to be of predictive value (Table 3). Multivariable Cox regression analysis confirmed thrombus level, nodal status and distant metastases as predictive variables for cancer specific survival. Similar results were shown in sub analyses, limited to non-metastatic and metastatic. Furthermore the latest subgroup of patients operated between 2006 and 2014 were analyzed the same way and demonstrated similar results (data not shown).

Table 1. Characteristics of RCC patients with IVC TT of RCC (at least pT3b stage) and descriptive statistics.

| All patients | Friable IVC TT | Solid IVC TT | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. of patients | 413 | 188 | 225 | |

| pT stage | p = 0.9a | |||

| pT3b | 251 | 112 | 139 | |

| pT3c | 130 | 61 | 69 | |

| pT4 | 32 | 15 | 17 | |

| Fuhrmann grade | p=0.2b | |||

| 1 | 9 | 4 | 5 | |

| 2 | 96 | 39 | 57 | |

| 3 | 194 | 83 | 111 | |

| 4 | 114 | 62 | 52 | |

| VTT level (Mayo classification) | p = 0.03a | |||

| 1 | 113 | 48 | 65 | |

| 2 | 136 | 75 | 61 | |

| 3 | 85 | 37 | 48 | |

| 4 | 79 | 28 | 51 | |

| Histological subtype | p = 0.4a | |||

| Clear cell RCC | 371 | 169 | 202 | |

| Papillary RCC | 29 | 11 | 18 | |

| Chromophobe RCC | 13 | 8 | 5 | |

| Nodal status | p = 0.8a | |||

| N0 / Nx | 297 | 134 | 163 | |

| N+ | 116 | 54 | 62 | |

| Distant metastasis | p = 0.2a | |||

| M0 / Mx | 303 | 145 | 158 | |

| M1 | 110 | 43 | 67 | |

| Perinephric fat invasion | p = 0.5a | |||

| Yes | 266 | 124 | 142 | |

| No | 147 | 64 | 83 | |

| IVC wall invasion | P = 0.2 a | |||

| Yes | 119 | 60 | 59 | |

| No | 294 | 128 | 166 | |

| Sex | p = 0.5a | |||

| Male | 278 | 123 | 155 | |

| Female | 135 | 65 | 70 | |

| Age | p = 0.49c | |||

| Mean | 61,5 | 61,0 | 61,9 | |

| Median | 62 | 61 | 63 | |

| Range | 20-84 | 20-84 | 23-84 |

Chi2 test,

Fisher's exact test,

T test.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of Cancer specific survival probability in patients with RCC and VTT involving the IVC [n = 413] stratified by thrombus consistency. Censored events are vertically marked. Log rank test showed no significant difference in survival probability between friable [n = 188] and solid [n = 255] VTT (p = 0.79).

Table 2.

Clinical features and cancer specific survival. Kaplan-Meier estimates and d Peto-Pike's log rank test.

| Variable | No. of patients | Actuarial 5-yr CSS (%) | Median CSS (months) | p valued |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombus consistency | p = 0.8 | |||

| Friable | 188 | 43,86 | 45 | |

| Solid | 225 | 49,55 | 50 | |

| pT stage | p < 0.001 | |||

| pT3b | 251 | 55,85 | 113 | |

| pT3c | 130 | 39,51 | 35 | |

| pT4 | 32 | 11,36 | 17 | |

| Fuhrmann grade | p < 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 9 | 25,4 | 26 | |

| 2 | 96 | 71,35 | >118 | |

| 3 | 194 | 44,67 | 51 | |

| 4 | 114 | 29,97 | 25 | |

| VTT level | p < 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 113 | 67,91 | >118 | |

| 2 | 136 | 48,94 | 51 | |

| 3 | 85 | 34,72 | 31 | |

| 4 | 79 | 32,2 | 30 | |

| Histological subtype | p = 0.005 | |||

| cRCC | 371 | 49,58 | 53 | |

| pRCC | 29 | 26,48 | 20 | |

| chRCC | 13 | 38,1 | 49 | |

| Nodal status | p < 0.001 | |||

| N0 / Nx | 297 | 55,15 | 84 | |

| N+ | 116 | 26,18 | 21 | |

| Distant metastasis | p < 0.001 | |||

| M0 / Mx | 303 | 56,55 | 99 | |

| M1 | 110 | 19,84 | 15 | |

| Perinephric fat invasion | p < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 266 | 36,71 | 34 | |

| No | 147 | 67,64 | 118 | |

| IVC wall invasion | p < 0.01 | |||

| Yes | 119 | 31,42 | 32 | |

| No | 294 | 51,72 | 81 | |

| Sex | p = 0.2 | |||

| Male | 278 | 50,03 | 78 | |

| Female | 135 | 42,56 | 41 | |

| Age | p = 0.1 | |||

| <60 | 170 | 41,54 | 43 | |

| ≥60 | 243 | 52,19 | 81 |

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses predicting cancer specific survival in the whole study cohort (N = 413).

| Variables | Univariable analyses | Multivariable analyses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | p value | HR | (95% CI) | p value | |

| Thrombus consistency | 1.04 | 0.77-1.41 | p = 0.8 | 1.01 | 0.74-1.38 | p = 0.9 |

| Thrombus level | 1.42 | 1.24-1.63 | p < 0.001 | 1.23 | 1.05-1.44 | p = 0.01 |

| pT stage | 1.88 | 1.52-2.34 | p < 0.001 | 1.28 | 0.99-1.65 | p = 0.06 |

| nodal status | 0.41 | 0.30-0.56 | p < 0.001 | 0.58 | 0.42-0.82 | p = 0.001 |

| distant metastasis | 0.31 | 0.22-0.42 | p < 0.001 | 0.45 | 0.32-0.63 | p < 0.001 |

| Perinephric fat invasion | 0.44 | 0.31-0.62 | p < 0.001 | 1.13 | 0.43-0.89 | p = 0.01 |

| Fuhrmann grade | 1.48 | 1.21-1.81 | p < 0.001 | 0.62 | 0.91-1.40 | p = 0.3 |

| IVC wall invasion | 0.59 | 0.42-0.82 | p < 0.01 | 0.99 | 0.64-1.151 | p = 0.9 |

Discussion

Locally advanced renal cell carcinoma with venous tumor thrombus is a grave disease with an unfavorable prognosis. Even if staging at diagnosis reveals no sign of metastases in our N0M0 subgroup it is accompanied with cancer specific death in approximately 29% of cases. Surgical resection remains the only treatment option for cure in non-metastatic disease and is also part of a multimodal treatment approach in metastatic disease because targeted therapy alone is considered to be less effective [7,8,19-21]. However in most patients with IVC involvement of RCC survival is limited. Taken into account the high risk of tumor recurrence or progression in patients with RCC and IVC despite surgery prognostic markers to identify patients in need for further treatment or closer follow up would be beneficial. In view of recently published data [9-11] the current study aimed to validate if thrombus consistency could serve as a significant and relevant prognostic marker for survival. Interestingly in our large multi-institutional cohort of 413 patients thrombus consistency neither is significantly involved in cancer specific survival analyzing Kaplan-Meier curves nor contributes significantly to survival in univariable and multivariable Cox regression. Dividing the study population into metastasized and non-metastasized patients demonstrated the same results for each subgroup.

Our results support recently published data by Antonelli et al. where tumor consistency also failed to serve as a predictive marker for survival in a smaller cohort of 147 patients [11]. These observations are in contrast to Bertini et al. who were able to show a significantly decreased cancer specific survival in patients with friable tumor thrombus in their study cohort of 174 patients with renal vein or IVC tumor thrombus. This unfavourable prognostic parameter was significant for their whole study cohort and for the non-metastasized subgroup.

The different prognostic relevance of tumor thrombus consistency between our data and Bertini et al. might result from inhomogeneous distribution of clinicopathologic features and from inclusion of level 0 VTT (renal vein tumor thrombus only). In the data set of Bertini et al. the friable thrombus consistency group was significantly associated with aggressive tumor characteristics such as nodal metastases, distant metastases or perinephric fat invasion whereas solid VTT was significantly associated with level 0 VTT which is known to be of significantly improved outcome compared to level I or higher VTT [21,22]. In our cohort of level I-IV VTT there was homogeneous distribution of these characteristics between friable and solid thrombus consistency group. Metastatic disease has been proven to be the strongest predictive factor for survival [7,9-11,22,23] and perinephric fat invasion has been considered to be an independent adverse prognostic marker in metastasized patients [11]. Our results support the hypothesis that poor outcome in patients with friable thrombus consistency as reported by Bertini et al. might rather be biased by the dominating impact of these unfavorable tumor characteristics than caused by friable thrombus related lack of cell adhesion molecules [10,11].

The other previously published study by Weiss et al. with 200 patients reported that friable thrombus consistency was solely significant in multivariable analysis of OS in non-metastasized patients [10]. These results might indicate again the dominating impact of metastatic disease on survival. Furthermore the inclusion of 137 level 0 VTT patients associated with solid thrombus consistency in 70% might bias the favorable survival in the solid thrombus consistency group [10].

In accordance to previously published data our study confirmed the impact of different clinicopathologic variables on survival: Thrombus level I and II showed a significantly increased survival compared to level III and IV and multivariable analysis confirmed thrombus level as independent prognostic marker in non-metastasized patients [7,13,24,25]. As reported by Bertini et al. and Weiss et al. predictive value of pT stage was restricted to univariable analysis [9,10]. In multivariable analysis redundancy of the variables thrombus level and perinephric fat invasion in pT stage analysis might bias the results. In non-metastasized tumor patients Fuhrman grade and thrombus level were independent predictors of poor survival indicating the tumor's capacity to invasive growth or metastatic spread [7]. IVC wall invasion deteriorated CSS significantly as previously reported by Hatcher et al. but was no independent predictor for survival in multivariable analysis [26].

In summary metastatic spread such as nodal involvement or distant metastases is the most decisive variable for survival exceeding almost all variables of locally advanced RCC: In the current study population, once metastasized, 5-year CSS probability is reduced by 60% compared to the non-metastasized group.

To complete the analysis of the impact of venous tumor thrombus consistency on RCC patients we further investigated how thrombus consistency would influence the surgical technique: Multivariable analysis revealed that thrombus consistency was no independent predictor for the necessity of cavectomy, cavotomy or Pringle maneuver whereas thrombus level - as commonly recognized [27,28] - proved to be of significant predictive value (data not shown).

Our study had several limitations determined by retrospective analysis and multi-institutional approach. IRCCVTC databank included 477 patients but due to missing data and non-RCC histopathology only 413 patients met all criteria mandatory for multivariable analysis. In contrast to previous publications where thrombus consistency was classified by histopathological re-evaluation [9-11], IRCCVTC data was limited to surgeons' intraoperative description of thrombus consistency. This might be negligible since Bertini has provided statistical measure of interrater-agreement between surgeons' description and retrospective histopathologic re-evaluation in a subgroup of 61 patients showing an excellent agreement (κ = 0.83) equal to the interrater-agreement between two pathologists (κ = 0.78) [9]. Our results might be biased by innovations in diagnostics, surgical treatment and targeted therapy during the analyzed period. Treatment of mRCC has changed dramatically with approval of targeted therapy in 2006. In our cohort 201 (49%) of patients had their date of surgery between 2006 and 2014 when targeted therapy was available. Of these 104 patients had solid and 97 had friable VTT. To exclude targeted therapy to have a relevant impact we performed additional analysis of this subgroup demonstrating similar results. Therefore we assume equal influence of targeted therapy on CSS in the friable VTT and solid VTT subgroup. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, this study provides the largest number of patients with RCC and VTT with IVC involvement analyzed for the impact of thrombus consistency on survival so far.

Conclusions

Our large multi-institutional and international study cohort provided unique data to define the role of thrombus consistency in RCC with VTT involving the IVC. Survival analysis showed no difference in survival between friable and solid thrombus consistency. Furthermore thrombus consistency was not of significance in prediction of survival. Traditionally used prognostic markers such as perinephric fat invasion, thrombus level or Fuhrman grade were shown to be of much stronger relevance. Our data confirmed once more metastatic disease as strongest independent predictor of poor survival. At present prognostic nomograms and models integrating clinical, pathological and molecular variables increasingly aim to guide cancer treatment. In RCC with VTT and IVC involvement the variable thrombus consistency failed to predict CSS and should therefore not be introduced in risk stratification models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: P30 CA008748

Funding Sources: No funding has been granted for the study.

Members of the International Renal Cell Carcinoma-Venous Thrombus Consortium (IRCCVTC):

Axel Haferkamp a, Umberto Capitanio b, Joaquín A. Carballido c, Venancio Chantada d, Thomas Chromecki e, Gaetano Ciancio f, Siamak Daneshmand g, Christopher P. Evans h, Paolo Gontero i, Javier González j, Markus Hohenfellner k, William C. Huang l, Theresa M. Koppie m, Danny Lascano n, John A. Libertino o, Estefanía Linares Espinós p, Adam Lorentz q, Juan I. Martínez-Salamanca c, Alon Y. Mass l, Viraj A. Master q, James M. McKiernan n, Francesco Montorsi b, Giacomo Novara r, Padraic O'Malley s, Sascha Pahernik k, Joan Palou t, José Luis Pontones Moreno u, Raj S. Pruthi v, Oscar Rodriguez Faba t, Paul Russo w, Douglas S. Scherr s, Shahrokh F. Shariat x, Martin Spahn y, Carlo Terrone z, Derya Tilki h, Dario Vázquez-Martul d, Cesar Vera Donoso u, Daniel Vergho y, Eric M. Wallen v, Richard Zigeuner e

- Department of Urology and Pediatric Urology, University Medical Center Mainz, Mainz, Germany

- Department of Urology, Hospital San Raffaele, University Vita-Salute, Milano, Italy

- Department of Urology, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

- Department of Urology, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña, Coruña, Spain

- Department of Urology, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria

- Miami Transplant Institute, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

- USC/Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, California, USA

- Department of Urology, UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento, California, USA

- Department of Urology, A.O.U. San Giovanni Battista, University of Turin, Turin, Italy

- Department of Urology, Hospital Central de la Cruz Roja San José y Santa Adela, Madrid, Spain

- Department of Urology, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany;

- Department of Urology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, USA

- Department of Urology, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA

- Department of Urology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, USA

- Department of Urology, Lahey Clinic, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA

- Department of Urology, Hospital Universitario Infanta Sofía, Madrid, Spain

- Department of Urology, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA

- Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology, University of Padua, Padua, Italy

- Department of Urology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, USA

- Department of Urology, Fundació Puigvert, Barcelona, Spain

- Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe, Valencia, Spain

- Department of Urology, UNC at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA

- Department of Surgery, Urology Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA

- Department of Urology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- Department of Urology, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany

- Division of Urology, Maggiore della Carita Hospital, University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara, Italy

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The participating centers provided local ethics committee approval for their site.

References

- 1.European Network of Cancer Registries. Eurocim version 4.0. European incidence database V2.3, 730 entity dictionary (2001) Vol. 2001. Lyon: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet] Vol. 2013. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; [accessed on 30/March/2015]. 2013. Available from: http://globocan.iarc.fr. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall VF, Middleton RG, Holswade GR, Goldsmith EI. Surgery for renal cell carcinoma in the vena cava. J Urol. 1970;103:414–420. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)61970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zisman A, Wieder JA, Pantuck AJ, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus extension: biology, role of nephrectomy and response to immunotherapy. J Urol. 2003;169:909–916. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000045706.35470.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilki D, Hu B, Nguyen HG, et al. Impact of synchronous metastasis distribution on cancer specific survival in renal cell carcinoma after radical nephrectomy with tumor thrombectomy. J Urol. 2015;193:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haferkamp A, Bastian PJ, Jakobi H, et al. Renal cell carcinoma with tumor thrombus extension into the vena cava: prospective long-term followup. J Urol. 2007;177:1703–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkali Z, Van Poppel H. A critical analysis of surgery for kidney cancer with vena cava invasion. Eur Urol. 2007;52:658–662. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertini R, Roscigno M, Freschi M, et al. Impact of venous tumour thrombus consistency (solid vs friable) on cancer-specific survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weiss VL, Braun M, Perner S, et al. Prognostic significance of venous tumour thrombus consistency in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) BJU Int. 2014;113:209–217. doi: 10.1111/bju.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonelli A, Sodano M, Sandri M, et al. Venous tumor thrombus consistency is not predictive of survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma: A retrospective study of 147 patients. Int J Urol. 2015;22:534–539. doi: 10.1111/iju.12738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Salamanca JI, Linares E, Gonzalez J, et al. Lessons learned from the International Renal Cell Carcinoma-Venous Thrombus Consortium (IRCC-VTC) Curr Urol Rep. 2014;15:404. doi: 10.1007/s11934-014-0404-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tilki D, Nguyen HG, Dall'Era MA, et al. Impact of histologic subtype on cancer-specific survival in patients with renal cell carcinoma and tumor thrombus. Eur Urol. 2014;66:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neves RJ, Zincke H. Surgical treatment of renal cancer with vena cava extension. Br J Urol. 1987;59:390–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1987.tb04832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobin LH, Gospodariwicz M, Wittekind C, editors. UICC International Union Against Cancer. 7th. Vol. 2009. Wiley-Blackwell; 2009. TNM classification of malignant tumors; pp. 255–257. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, et al. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Vol. 2004. Lyons: IARC Press; 2004. p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of Renal Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1469–1489. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f2d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ackermann H. BIAS - A PROGRAM PACKAGE FOR BIOMETRICAL ANALYSIS OF SAMPLES. Comput Stat Data Anal. 1991;11:223–224. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flanigan RC, Mickisch G, Sylvester R, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with metastatic renal cancer: a combined analysis. J Urol. 2004;171:1071–1076. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110610.61545.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heng DY, Wells JC, Rini BI, et al. Cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastases from renal cell carcinoma: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur Urol. 2014;66:704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moinzadeh A, Libertino JA. Prognostic significance of tumor thrombus level in patients with renal cell carcinoma and venous tumor thrombus extension Is all T3b the same? J Urol. 2004;171:598–601. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000108842.27907.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner B, Patard JJ, Mejean A, et al. Prognostic value of renal vein and inferior vena cava involvement in renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2009;55:452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zargar-Shoshtari K, Sharma P, Espiritu P, et al. Caval tumor thrombus volume influences outcomes in renal cell carcinoma with venous extension. Urol Oncol. 2015;33:112 e123–119. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HL, Zisman A, Han KR, et al. Prognostic significance of venous thrombus in renal cell carcinoma Are renal vein and inferior vena cava involvement different? J Urol. 2004;171:588–591. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000104672.37029.4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sosa RE, Muecke EC, Vaughan ED, Jr, McCarron JP., Jr Renal cell carcinoma extending into the inferior vena cava: the prognostic significance of the level of vena caval involvement. J Urol. 1984;132:1097–1100. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatcher PA, Anderson EE, Paulson DF, et al. Surgical management and prognosis of renal cell carcinoma invading the vena cava. J Urol. 1991;145:20–23. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38235-6. discussion 23-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agochukwu N, Shuch B. Clinical management of renal cell carcinoma with venous tumor thrombus. World J Urol. 2014;32:581–589. doi: 10.1007/s00345-014-1276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Psutka SP, Leibovich BC. Management of inferior vena cava tumor thrombus in locally advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ther Adv Urol. 2015;7:216–229. doi: 10.1177/1756287215576443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.