SUMMARY

Insulin signaling regulates many facets of animal physiology. Its dysregulation causes diabetes and other metabolic disorders. The spindle checkpoint proteins MAD2 and BUBR1 prevent precocious chromosome segregation and suppress aneuploidy. The MAD2 inhibitory protein p31comet promotes checkpoint inactivation and timely chromosome segregation. Here, we show that whole-body p31comet knockout mice die soon after birth and have reduced hepatic glycogen. Liver-specific ablation of p31comet causes insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, glucose intolerance, and hyperglycemia, and diminishes the plasma membrane localization of insulin receptor (IR) in hepatocytes. MAD2 directly binds to IR and facilitates BUBR1-dependent recruitment of the clathrin adaptor AP2 to IR. p31comet blocks the MAD2–BUBR1 interaction and prevents spontaneous clathrin-mediated IR endocytosis. BUBR1 deficiency enhances insulin sensitivity in mice. BUBR1 depletion in hepatocytes or expression of MAD2-binding-deficient IR suppresses metabolic phenotypes of p31comet ablation. Our findings establish a major IR regulatory mechanism and link guardians of chromosome stability to nutrient metabolism.

INTRODUCTION

Insulin regulates systemic metabolic homeostasis in animals, as well as cell survival, growth, and proliferation in multiple tissues and organs. The main framework of insulin signaling has been established for decades (White, 2003). At the plasma membrane (PM), insulin binds and activates the insulin receptor (IR), a receptor tyrosine kinase that consists of a dimer of two disulfide-linked chains, IRα and IRβ. Activated IR phosphorylates itself and insulin receptor substrate 1/2 (IRS1/2), creating phospho-tyrosine (pY)-containing docking motifs for downstream effectors and adaptors. These proteins activate the PI3K-AKT and MAP kinase pathways to promote cellular glucose uptake, glycogen and protein synthesis, and cell growth and survival (Boucher et al., 2014). Activated IR can be internalized through clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Goh and Sorkin, 2013), thus terminating signaling. Dysregulation of insulin signaling has been linked to human diseases, including diabetes and cancer (Boucher et al., 2014; Pollak, 2012).

In response to kinetochores not properly attached to spindle microtubules, the spindle checkpoint inhibits the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) and delays anaphase onset, thereby suppressing chromosome segregation errors (Jia et al., 2013; London and Biggins, 2014; Musacchio, 2015). The checkpoint proteins MAD2 and BUBR1 can simultaneously bind to CDC20, converting it from an APC/C activator to a subunit of an APC/C-inhibitory complex called the mitotic checkpoint complex (MCC) (Izawa and Pines, 2015). MAD2 is an unusual protein with multiple folded conformers, including the latent, open MAD2 (O-MAD2) and the active, closed MAD2 (C-MAD2) (Luo and Yu, 2008; Mapelli and Musacchio, 2007). Upon checkpoint activation, unattached kinetochores convert O-MAD2 to CDC20-bound C-MAD2. C-MAD2–CDC20 then associates with BUBR1 to form MCC (Kulukian et al., 2009), in which BUBR1 contacts both C-MAD2 and CDC20 (Chao et al., 2012). During checkpoint inactivation, p31comet (also known as MAD2L1BP) specifically binds to C-MAD2 and disrupts the C-MAD2–BUBR1 interaction, thus promoting MCC disassembly and timely anaphase onset (Hagan et al., 2011; Jia et al., 2011; Xia et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2007). The intricate interactions among p31comet, MAD2, and BUBR1 are crucial for proper chromosome segregation and genomic stability.

In this study, we discover a role of the p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 module of mitotic regulators in insulin signaling, thus linking a critical chromosome segregation network to a major pathway regulating metabolic homeostasis.

RESULTS

p31comet Ablation in Mice Causes Neonatal Lethality and Liver Glycogen Shortage

Mad2 overexpression in mice promotes aneuploidy and tumorigenesis through hyperactivation of the spindle checkpoint (Sotillo et al., 2007). To test whether inactivation of p31comet might similarly cause hyperactivation of the checkpoint and promote tumorigenesis, we generated mice with floxed alleles of p31comet (p31F/F), and crossed them with CAG-Cre transgenic mice to delete p31comet in the whole body (Figure S1A–C). Homozygous p31comet knockout (p31−/−) mice were born in the expected Mendelian ratio. Heterozygous p31+/− mice did not show discernible differences from wild-type (WT) littermates (Figure 1A and 1B). p31−/− newborns and embryos at E18.5, however, showed mild growth retardation, and died within 5 hours after birth, in spite of suckling activity. Thus, instead of being susceptible to tumorigenesis, p31−/− mice exhibited neonatal lethality.

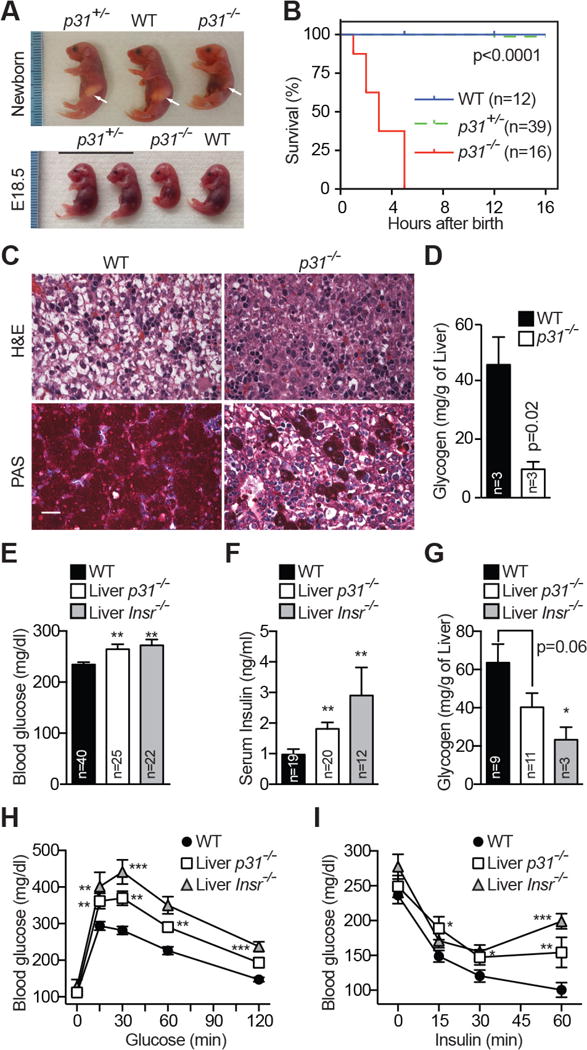

Figure 1. Whole-body and Liver-specific Ablation of p31comet Reveals Its Role in Metabolism.

(A) Wild-type (WT), p31+/−, and p31−/− littermate at E18.5 and birth. Arrows indicate milk spots.

(B) Survival curves of WT, p31+/−, and p31−/− neonates.

(C) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining (magenta) of livers from WT and p31−/− newborns. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(D) Liver glycogen levels of WT and p31−/− newborns.

(E) Fed blood glucose levels of WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− mice. Mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.0001 versus WT; Mean ± SEM (E–I).

(F) Serum insulin concentrations of WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− mice.

(G) Liver glycogen levels of WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− mice.

(H) Glucose tolerance test in 2-month-old male mice. WT, n=21; liver-p31−/−, n=16; liver-Insr−/−, n=9.

(I) Insulin tolerance test in 2-month-old male mice. WT, n=16; liver-p31−/−, n=9; liver-Insr−/−, n=12.

The p31comet protein was expectedly absent in p31−/− MEFs (Figure S1D). The p31comet protein level in p31+/− MEFs was about 65% of that in WT, and these p31+/− cells did not show discernable abnormalities. The p31−/− MEFs proliferated more slowly than WT MEFs did (Figure S1E), and had elevated apoptosis, decreased S-phase population, and increased G2/M population (Figure S1F). Consistent with established mitotic roles of p31comet, p31−/− MEFs exhibited a mitotic delay and abnormal mitotic features, including lagging chromosomes (Figure S1G–I). Consequently, p31−/− MEFs displayed increased polyploidy and aneuploidy (Figure S1J and S1K). These results validate the functions of p31comet in mitotic regulation and in suppressing chromosome instability.

The mitotic and aneuploidy phenotypes of p31−/− MEFs were similar to those reported for MEFs with a hypomorphic allele of Cdc20 (Malureanu et al., 2010). Mice with the same hypomorphic Cdc20 allele were, however, viable (Malureanu et al., 2010). Similarly, partial inactivation of other mitotic regulators, including BUBR1, induces aneuploidy in mice without compromising their viability (Baker et al., 2004). Therefore, mitotic defects and aneuploidy alone in mice do not necessarily lead to neonatal lethality.

We investigated the defects underlying the neonatal lethality of p31−/− mice. The p31+/− mice did not show discernible differences from WT littermates. Despite mild growth retardation, p31−/− embryos and newborns did not show gross morphological and developmental defects. The lung and respiratory muscle in p31−/− animals were normal, and there was evidence of lung inflation. p31−/− mice also showed normal liver development (Figure S2A). However, unlike WT and p31+/− mice, hepatocytes from p31−/− E18.5 embryos and newborns had reduced cytoplasmic vacuolation (Figure 1C and S2A), suggestive of defects in hepatic glycogen storage.

Indeed, liver sections of p31−/− newborn mice showed dramatically reduced periodic acid Schiff (PAS) staining, which detected polysaccharides, including glycogen (Figure 1C). As a control, the skeletal muscle in hind limbs of p31−/− animals exhibited normal PAS staining (Figure S2B). Direct biochemical measurement confirmed that the p31−/− liver had significantly lower glycogen content (Figure 1D). Glycogen storage in the liver is crucial for energy homeostasis of newborn mice, and hypoglycemia is a major cause of neonatal lethality (Girard and Pegorier, 1998). We suspect that the insufficient energy to breathe and inability to transition from placenta to nursing, as consequences of decreased glycogen stores in the liver, are causal factors of neonatal lethality in p31−/− animals. These phenotypes of p31−/− mice closely resemble those of insulin receptor (IR) knockout (Insr−/−) mice (Joshi et al., 1996), although we did not observe muscle hypotrophy in p31−/− mice, as seen with Insr−/− mice.

Liver-specific p31comet Ablation Causes Metabolic Disorders in Mice

Liver-specific insulin receptor knockout (liver-Insr−/−) mice survive to adulthood, and develop severe hepatic insulin resistance and metabolic syndromes (Biddinger et al., 2008; Michael et al., 2000), indicating that insulin resistance in the liver is a major cause of metabolic disorders. We generated liver-specific p31comet knockout mice (liver-p31−/−) by crossing p31F/F mice with Albumin-Cre mice. Liver-p31−/− mice were born in the expected Mendelian ratio, were indistinguishable from WT littermates, and survived to adulthood. Histological analysis did not reveal hepatic developmental defects in liver-p31−/− embryos and mice (Figure S2C and S2D). The hepatic glycogen level of liver-p31−/− E18.5 embryos was reduced, but to a much less extent than p31−/− embryos, allowing liver-p31−/− mice to survive. Clearly, p31comet has functions in non-liver tissues, which help to maintain hepatic glycogen levels. Liver-Insr−/− mice showed normal hepatic architecture, but had scattered focal dysplasia in the periportal area (Figure S2D), as reported previously (Michael et al., 2000).

Two-month old liver-p31−/− mice showed hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in the fed state, although their hyperinsulinemia was less severe compared to liver-Insr−/− mice (Table S1; Figure 1E and 1F). Despite having elevated serum insulin levels, liver-p31−/− mice had a decreased level of hepatic glycogen (Figure 1G and S2D). Again, the hepatic glycogen shortage in liver-p31−/− mice was less severe than that in liver-Insr−/− mice. The hepatic triglyceride levels of liver-p31−/− mice were decreased by about 50% whereas their serum triglyceride levels were moderately increased (Table S1). These results indicate that specific ablation of p31comet in the liver can promote systemic changes in glucose and lipid metabolism.

Liver-Insr−/− mice showed severe glucose and insulin intolerance (Michael et al., 2000) (Figure 1H and 1I). Two-month-old male liver-p31−/− mice also developed glucose and insulin intolerance, albeit to lesser degrees. These data indicate that loss of p31comet in the liver suffices to produce defects in insulin modulation of glucose metabolism. The whole-body p31+/− mice had normal glucose metabolism (Figure S2E), indicating that p31comet is not haploinsufficient.

Liver-Insr−/− mice progressively developed liver dysfunction, but surprisingly did not show severe glucose/insulin intolerance at an older age (Michael et al., 2000). Indeed, the blood glucose levels of 6-month-old liver-Insr−/− and liver-p31−/− mice became normal (Figure S2F). Similar phenotypes of whole-body and liver-specific p31comet and Insr knockout mice implicate p31comet in insulin signaling.

p31comet Regulates Insulin Signaling

In the liver, an important downstream event of insulin signaling is the stimulation of glycogen synthesis by activating glycogen synthase (GS) (Boucher et al., 2014). As expected, insulin treatment stimulated the GS activity in WT hepatocytes, and this stimulation was absent in liver-Insr−/− hepatocytes (Figure 2A). Strikingly, insulin-dependent GS activation was abolished in liver-p31−/− hepatocytes, consistent with the hepatic glycogen shortage in p31−/− mice. Thus, p31comet is required for a crucial branch of insulin signaling in hepatocytes.

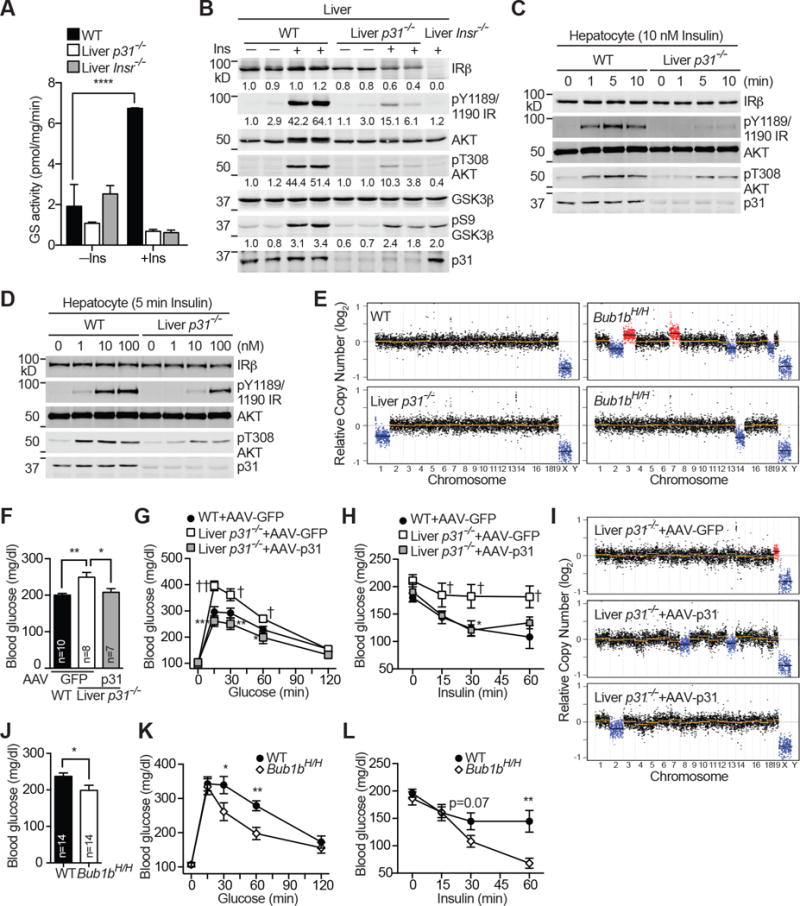

Figure 2. p31comet Ablation Causes Insulin Resistance whereas Bub1b Insufficiency Enhances Insulin Sensitivity.

(A) Glycogen synthase activity of WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− hepatocytes treated without (–) or with (+) insulin (Ins). Mean ± SD (n = 4 independent experiments).

B) Immunoblots of whole liver lysates of WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− mice treated without (−) or with (+) insulin (Ins). Each lane contains lysate from an individual mouse. The relative band intensities are quantified and shown below.

(C & D) Insulin signaling in primary WT and liver-p31−/− hepatocytes treated with 10 nM insulin for the indicated times (C) or increasing concentrations of insulin for 5 min (D). Cell lysates were blotted with the indicated antibodies.

(E) Segmentation plots of euploid (WT) and aneuploid hepatocytes from liver-p31−/− and Bub1bH/H mice.

(F–H) Fed blood glucose levels (F), glucose tolerance test (G), insulin tolerance test (H) of WT and liver-p31−/− mice injected with AAV-GFP or AAV-p31. WT (AAV-GFP), n=10; liver-p31−/− (AAV-GFP), n=8; liver-p31−/− (AAV-p31), n=7; mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 versus liver-p31−/− (AAV-GFP); p†<0.05, ††p<0.01 versus WT (AAV-GFP).

(I) Segmentation plots of aneuploid cells from liver-p31−/− mice injected with AAV-GFP or AAV-p31.

(J–L) Fed blood glucose levels (J), glucose tolerance test (K), insulin tolerance test (L) of WT and Bub1bH/H mice. For GTT and ITT, at least 12 mice in each group were analyzed. Mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01.

To determine at which step p31comet regulated IR signaling, we monitored the status of IR autophosphorylation, activating phosphorylation of AKT (pT308), and inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK3β (pS9) in whole liver lysates (Figure 2B). WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− mice were fasted overnight, and injected with insulin via inferior vena cava. Liver lysates were prepared from these mice and subjected to quantitative immunoblotting. The p31comet protein was reduced by about 80% in liver-p31−/− whole liver lysates (Figure 2B). As hepatocytes make up about 85% of total cells in the liver, the residual p31comet in liver-p31−/− animals was likely from non-parenchymal cells. IR autophosphorylation and AKT pT308 were greatly reduced in both liver-Insr−/− and liver-p31−/− animals. GSK3β pS9 was also reduced in both groups, but to a lesser degree, implicating the existence of IR-independent mechanisms for this phosphorylation. Consistent with the in vivo findings, freshly isolated liver-p31−/− primary hepatocytes showed weakened and delayed IR autophosphorylation and AKT pT308 at multiple time points and over a wide range of insulin concentrations (Figure 2C, 2D, S3A, and S3B). Therefore, p31comet is required for insulin signaling, at the step or upstream of IR autophosphorylation.

Aneuploidy Alone Is Insufficient to Promote Insulin Resistance

The status of aneuploidy in normal hepatocytes is still controversial, and it is formally possible that the insulin signaling defects of liver-p31−/− mice are a secondary consequence of severe aneuploidy in hepatocytes. To assess the extent of hepatic aneuploidy in these mice, we isolated live hepatocytes from WT and liver-p31−/− mice, sorted tetraploid cells, amplified and sequenced genomic DNA from single cells, and analyzed the whole-genome copy number variation. We analyzed hepatocytes from mice harboring hypomorphic alleles of BUBR1 (Bub1bH/H) as a control (Baker et al., 2004). Consistent with a previous study (Knouse et al., 2014), none of the 15 WT hepatocytes were aneuploid whereas about 20% Bub1bH/H (2 out of 10) were aneuploid (Figure 2E and S3C). Only 1 out of 10 p31−/− hepatocytes was aneuploid. Thus, the aneuploidy incidence of p31−/− hepatocytes was surprisingly low.

We tested whether p31comet restoration rescued the metabolic and insulin signaling defects of liver-p31−/− mice. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated expression of p31comet, but not GFP, in the liver rescued the hyperglycemia and glucose/insulin intolerance phenotypes and insulin signaling defects in liver-p31−/− mice (Figure 2F–H and S3D). We performed single-cell sequencing to assess the extent of aneuploidy in hepatocytes from liver-p31−/− mice injected with AAV-GFP or AAV-p31. Only 1 of 40 hepatocytes in the AAV-GFP group was aneuploid, and 2 of 39 hepatocytes in the AAV-p31 group were aneuploid (Figure 2I and S3E). Thus, the extent of aneuploidy in liver-p31−/− hepatocytes is very low (about 5%). p31comet restoration rescues the metabolic defects of p31comet ablation without eliminating aneuploidy, arguing against aneuploidy as the underlying reason for the observed defects.

We next analyzed glucose metabolism and insulin signaling in Bub1bH/H mice. The aneuploidy incidence in Bub1bH/H hepatocytes was higher than that in liver-p31−/− hepatocytes (Figure 2E, S3C, and S3E) (Knouse et al., 2014). Strikingly, Bub1bH/H mice exhibited a reduced blood glucose level in the fed state (Figure 2J), and increased glucose tolerance (Figure 2K) and insulin sensitivity (Figure 2L). In contrast to liver-p31−/− hepatocytes, IR autophosphorylation and AKT phosphorylation in response to insulin were more robust in Bub1bH/H hepatocytes (Figure S3F–I). The fact that another aneuploid mouse model (Bub1bH/H) exhibited opposite insulin signaling phenotypes again argues against aneuploidy as the underlying cause of defective insulin signaling in p31−/− animals. These findings are more consistent with a karyotype-independent regulatory function of p31comet in insulin signaling.

p31comet Prevents Unscheduled Clathrin-mediated Endocytosis of IR

The requirement for p31comet in IR autophosphorylation indicates that p31comet acts upstream in the pathway, possibly at the level of IR itself. Upon insulin stimulation, activated IR at the PM can be internalized by clathrin-dependent or –independent pathways (Goh and Sorkin, 2013). We generated human HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines stably expressing C-terminal GFP-tagged IR and examined the localization of IR-GFP after transfection with control or p31comet siRNAs (Figure 3A). In control cells, IR localized to PM in the absence of insulin, and was internalized upon insulin treatment and co-localized with RAB7, a late endosome marker. In contrast, IR-GFP in p31comet-depleted cells had much weaker PM localization, and was enriched in intracellular compartments (ICs), even without insulin treatment. A large fraction of these IR-positive ICs was positive for RAB7. The GTPase dynamin is essential for clathrin-mediated endocytosis (McMahon and Boucrot, 2011). Addition of dynasore (Macia et al., 2006), a chemical inhibitor of dynamin, blocked the aberrant IR internalization in p31comet-depleted HepG2 cells (Figure 3B and 3C). Co-depletion of the clathrin heavy chain (CLTC) also restored IR at PM in p31comet-depleted cells. Thus, p31comet suppresses unscheduled clathrin-dependent IR internalization in the basal state in HepG2 cells.

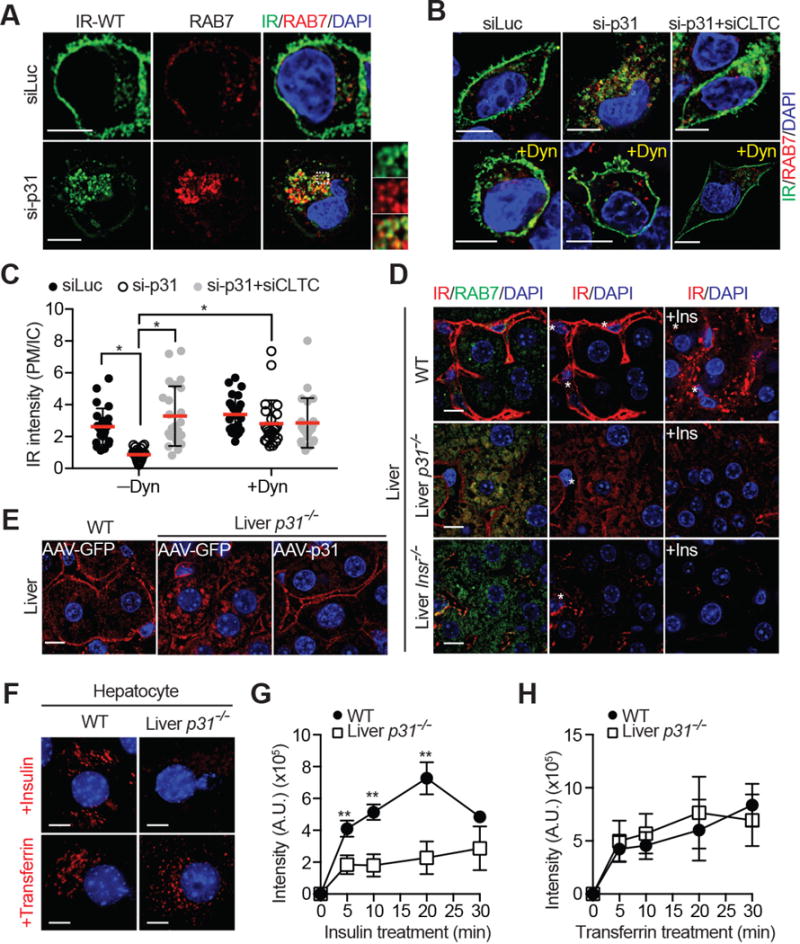

Figure 3. p31comet Suppresses Spontaneous IR Endocytosis in the Absence of Insulin.

(A & B) HepG2 cells stably expressing IR-WT-GFP were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, serum starved, treated without or with 80 μM dynasore (Dyn), and stained with anti-GFP (IR; green) and anti-RAB7 (red) antibodies and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm.

(C) Quantification of the ratios of PM and IC IR-GFP signals of cells in (B) (mean ± SD; *p<0.0001).

(D) Liver sections of WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− mice injected with PBS or insulin (+Ins) were stained with anti-IR (red) and anti-RAB7 (green) antibodies and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm. Asterisks indicate sinusoids.

(E) Liver sections of WT and liver-p31−/− mice injected with AAV-GFP or AAV-p31 were stained with anti-IR (red) antibodies and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm.

(F) Representative images of endocytosis assays with Cy3-insulin and Alexa 568-transferrin in WT and liver-p31−/− hepatocytes at 20 min. The insulin and transferrin signals are shown in red. The DAPI signals are shown in blue. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(G and H) Endocytosis of insulin (G) and transferrin (H) in WT and liver-p31−/− hepatocytes. The intensities of internalized fluorescent signals at the indicated times were quantified (mean ± SD; n=3 independent experiments with >70 cells analyzed at each time point).

We next analyzed the localization of endogenous IR and its regulation by insulin in the liver of WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− mice in vivo (Figure 3D). IR localized to the PM of hepatocytes in the WT liver, and underwent insulin-triggered internalization. The PM staining of IR was absent in liver-Insr−/− hepatocytes, although we could detect residual IR signals in non-parenchymal cells. Even without insulin injection, the PM IR signal in the liver of liver-p31−/− animals was already weak, whereas the IR signal in RAB7-positive ICs was strong. AAV-mediated p31comet expression in liver-p31−/− mice restored the PM IR signal in the liver (Figure 3E). These results establish a role of p31comet in suppressing IR internalization in vivo.

We monitored the kinetics of insulin endocytosis in WT and liver-p31−/− hepatocytes. At several time points, the intensities of internalized, fluorescently labeled insulin in liver-p31−/− hepatocytes were much weaker than those in WT hepatocytes (Figure 3F and 3G). In contrast, the internalization of transferrin, another client of clathrin-mediated endocytosis, was normal in liver-p31−/− hepatocytes (Figure 3F and 3H). These results indicate that p31comet specifically regulates insulin endocytosis, but not all forms of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Both defective insulin endocytosis and insulin-triggered IR autophosphorylation in p31comet-deficient cells can be attributed to the decreased level of functional IR at the PM due to its premature internalization prior to insulin stimulation.

MAD2 Directly Binds to a Canonical MIM Motif in IR

We wondered whether p31comet function in regulating IR internalization involved MAD2. MAD2 had been reported as an IR-binding protein in yeast two-hybrid and proteomic screens (Hutchins et al., 2010; O’Neill et al., 1997). MAD2 binds to MAD1 and CDC20 through the MAD2-interacting motif (MIM) with the consensus of (K/R)ψψXψX3–4P (ψ, a hydrophobic residue; X, any residue; Figure 4A). The C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of IR contained a putative MIM (Figure 4A). A peptide containing this motif (IRMIM-WT) bound efficiently to purified recombinant MAD2 WT and a monomeric mutant R133A (Figure 4B), but did not interact with MAD2 ΔC, a truncation mutant that could not form C-MAD2. A mutant IR peptide (IRMIM-4A) did not interact with MAD2. Immunoprecipitation with a C-MAD2-specific antibody (Fava et al., 2011) confirmed that IR-bound MAD2 formed C-MAD2 (Figure 4C). IRMIM-WT bound to C-MAD2R133A with a dissociation constant of 380 nM (Figure 4D). Thus, IR contains a functional MIM.

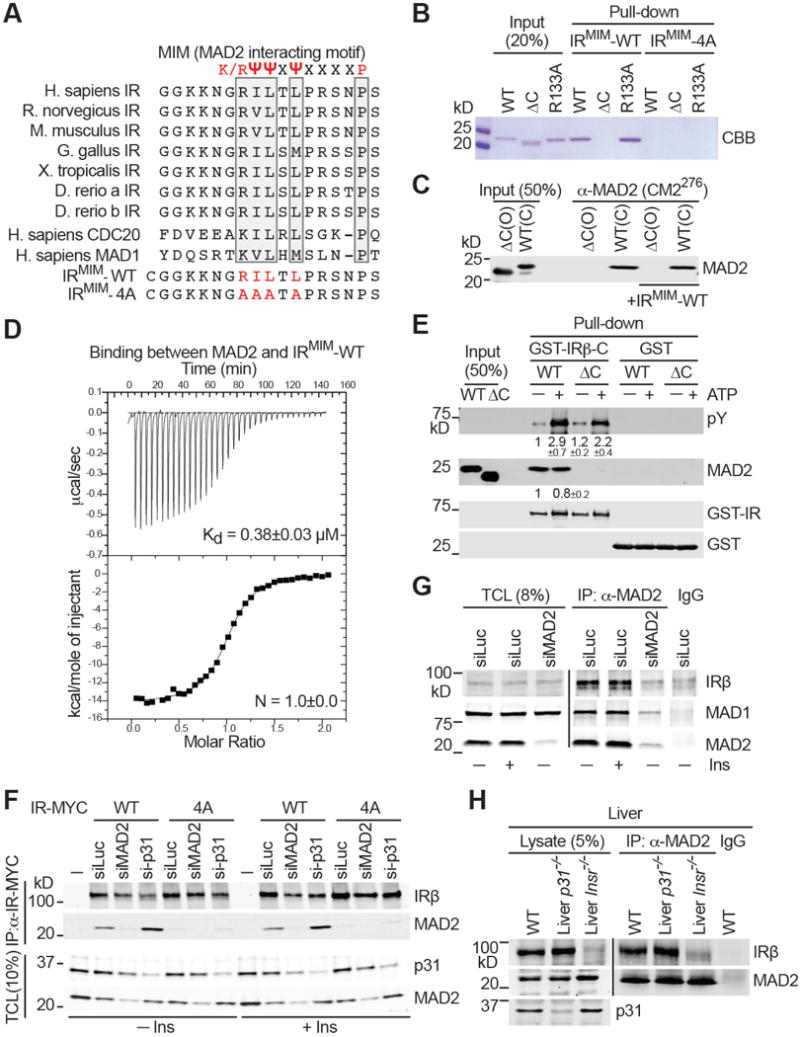

Figure 4. MAD2 Binds to a Canonical MIM in the C-terminal Tail of IR.

(A) Sequence alignment of the C-terminal tail of IR proteins and human CDC20 and MAD1, with the conserved residues in the MAD2-interacting motif (MIM) boxed. The MIM consensus is shown on top. Sequences of IRMIM-WT and IRMIM-4A peptides are also shown.

(B) Beads coupled to IRMIM-WT or IRMIM-4A were incubated with the indicated MAD2 proteins. Input and proteins bound to beads were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie (CBB).

(C) Beads coupled to a C-MAD2-specific antibody were incubated with the indicated MAD2 proteins in the presence or absence of IRMIM-WT. Input and beads-bound proteins were detected with the anti-MAD2 antibody.

(D) ITC analysis of binding between MAD2 and IRMIM-WT, with the Kd and binding stoichiometry (N) indicated.

(E) GST pull-down assays with recombinant GST-IRβ-C and MAD2. Input and beads-bound proteins were blotted with the indicated antibodies. The relative intensities of pY and MAD2 (mean ± SEM; n=3 independent experiments) are shown below.

(F) 293FT cells were co-transfected with IR-WT-MYC or IR-4A-MYC constructs and the indicated siRNAs, serum starved, and treated without (−) or with (+) 100 nM insulin (Ins) for 20 min. The total cell lysate (TCL) and anti-MYC IP were blotted with the indicated antibodies.

(G) HepG2 cells were transfected with siLuc or siMAD2, serum starved, and treated without (−) or with (+) 100 nM insulin (Ins) for 20 min. TCL, anti-MAD2 IP, and IgG IP were blotted with the indicated antibodies.

(H) Total liver lysates from WT, liver-p31−/−, and liver-Insr−/− mice, and anti-MAD2 and IgG IP from these lysates were blotted with the indicated antibodies.

MAD2 WT, but not ΔC, interacted with the cytoplasmic domain of IRβ (IRβ-C) (Figure 4E), indicating that the MIM is not masked in the intact cytoplasmic domain of IR, and is available for MAD2 binding. MAD2 binding did not affect the kinase activity of IR, and vice versa. Furthermore, IR-WT-MYC interacted with endogenous MAD2 in 293FT cells, whereas IR-4A-MYC did not (Figure 4F). Depletion of p31comet enhanced the IR–MAD2 interaction, suggesting that p31comet might promote IR–C-MAD2 disassembly. Endogenous MAD2 and IR interacted with each other in HepG2 cells (Figure 4G) and in whole liver lysates of WT and liver-p31−/− mice (Figure 4H). Unlike in 293FT cells depleted p31comet, we did not observe a significant increase of the IR–MAD2 interaction in liver lysates of liver-p31−/− mice, suggesting that p31comet might not actively promote IR–MAD2 disassembly in hepatocytes.

A previous report showed that insulin-stimulated IR activation reduced the IR–MAD2 interaction in IR-overexpressing CHO cells (O’Neill et al., 1997). In contrast, we found that the IR–MAD2 interaction in vitro and in human cells was not regulated by insulin (Figure 4E–G). Thus, IR binds to MAD2 through a canonical MIM in vitro and in vivo. This interaction is constitutive, and is not regulated by insulin.

p31comet Regulates IR Endocytosis by Counteracting MAD2

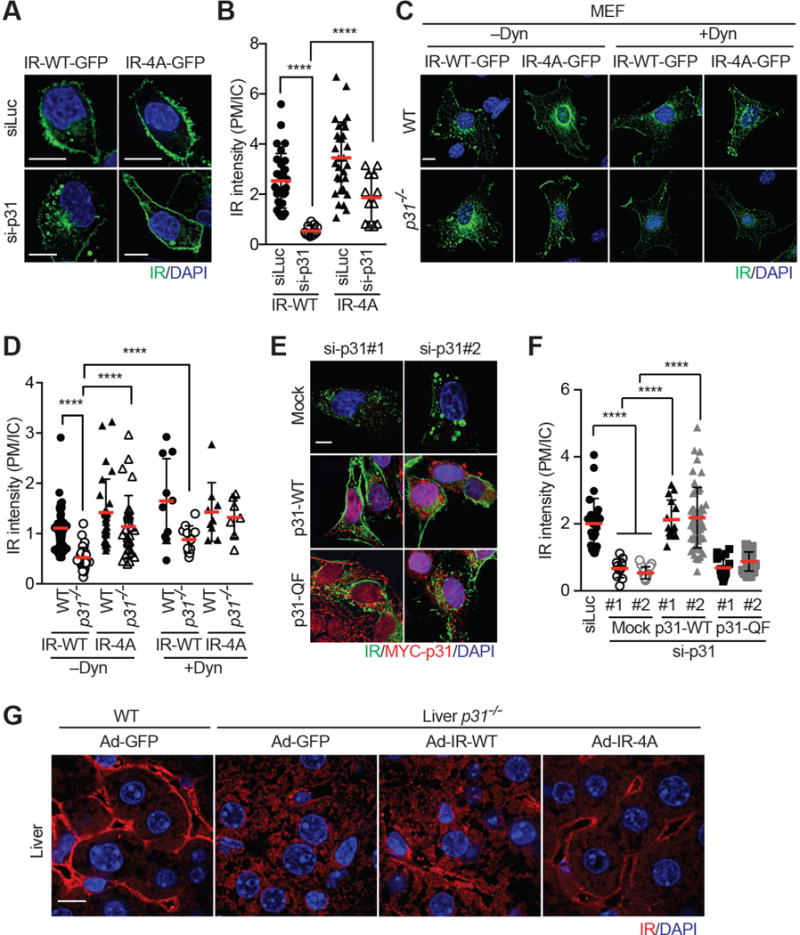

We generated HepG2 cells stably expressing IR-4A-GFP and examined the subcellular localization of this MAD2-binding-deficient mutant. IR-WT localized to the PM in control-depleted cells, but localized to intracellular compartments in p31comet-depleted cells (Figure 5A and 5B). In contrast, IR-4A retained its PM localization even in p31comet-depleted cells. Similar results were obtained in p31−/− MEFs (Figure 5C and 5D). Expression of p31comet WT, but not the MAD2-binding-deficient Q83A/F191A (QF) mutant (Yang et al., 2007), restored IR at the PM of p31comet-depleted cells (Figure 5E and 5F). Adenovirus-mediated expression of IR-4A, but not IR-WT or GFP, in the liver of liver-p31−/− mice restored IR at the PM in hepatocytes (Figure 5G). These results establish the importance of IR–MAD2 and MAD2–p31comet interactions in IR endocytosis, and indicate that p31comet regulates insulin signaling through suppressing MAD2.

Figure 5. p31comet Suppresses Spontaneous IR Endocytosis through Counteracting the IR–MAD2 Interaction.

(A) HepG2 cells stably expressing IR-WT-GFP or IR-4A-GFP were transfected with siLuc or sip31, serum starved, and stained with anti-GFP (IR; green) antibody and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm.

(B) Quantification of the ratios of PM and IC IR-GFP signal intensities in (A) (mean ± SD; ****p<0.0001).

(C) WT and p31−/− MEFs were infected with IR-WT-GFP or IR-4A-GFP retroviruses, serum starved, treated without or with dynasore (Dyn), and stained with anti-GFP (IR; green) antibody and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D) Quantification of the ratios of PM and IC IR-GFP signal intensities in (C) (mean ± SD; ****p<0.0001).

(E) IR-GFP-expressing HepG2 cells were co-transfected with the indicated siRNAs and plasmids, and stained with anti-GFP (IR; green) and anti-MYC (p31comet; red) antibodies, and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(F) Quantification of the ratios of PM and IC IR-GFP signal intensities in (E) (mean ± SD; ****p<0.0001).

(G) Liver sections of WT and liver-p31−/− mice injected with Ad-GFP, Ad-IR-WT, or Ad-IR-4A were stained with anti-IR (red) antibody and DAPI (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm.

p31comet Blocks MAD2–BUBR1-dependent AP2 Recruitment

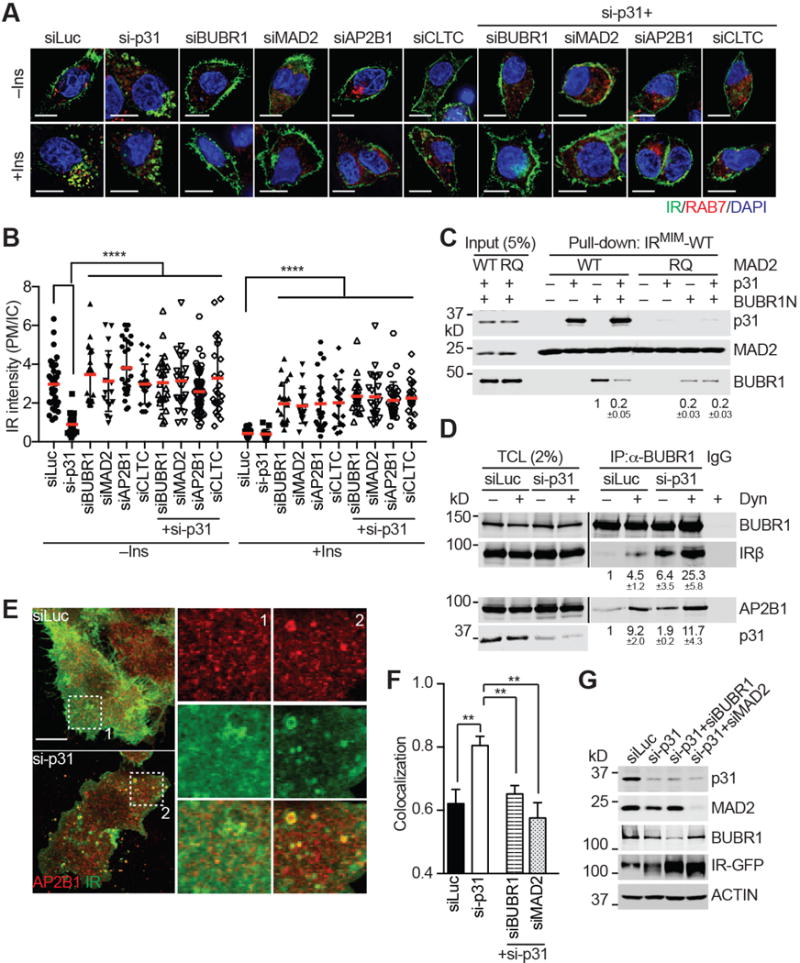

Adaptor Protein 2 (AP2) is crucial for clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and interacts with both clathrin and the cargo (McMahon and Boucrot, 2011). AP2 is a heterotetramer of α, β2, μ2, and σ2 subunits. BUBR1 has been reported to interact with AP2-β2 (AP2B1) (Cayrol et al., 2002). Through its αC dimerization helix, C-MAD2 can directly bind to BUBR1 (Chao et al., 2012). MAD2 might bridge an interaction between IR and BUBR1–AP2, thus promoting clathrin-mediated endocytosis of IR. Consistent with this hypothesis, the aberrant IR endocytosis in p31comet-depleted HepG2 cells required clathrin, AP2, MAD2, and BUBR1 (Figure 6A, 6B, and S4A–C). Depletion of MAD2 or BUBR1 partially blocked IR endocytosis induced by insulin. Thus, MAD2 and BUBR1 are required for untimely IR internalization in cells with a compromised p31comet function and for insulin-triggered IR endocytosis.

Figure 6. p31comet Prevents MAD2- and BUBR1-dependent IR Endocytosis through Blocking AP2 Recruitment.

(A) IR-GFP-expressing HepG2 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, treated without or with 100 nM insulin (Ins) for 5 min, and stained with DAPI (blue) and anti-GFP (IR; green) and anti-RAB7 (red) antibodies. Scale bars, 10 μm.

(B) Quantification of the ratios of PM and IC IR-GFP signal intensities in (A) (mean ± SD; ****p<0.0001).

(C) The indicated proteins were incubated for 1 hr and added to beads coupled to the IRMIM-WT peptide. Proteins bound to beads were blotted with the indicated antibodies. The relative BUBR1 intensities (mean ± SEM; n=3 independent experiments) are shown below.

(D) 293T cells were transfected with plasmids encoding MYC-BUBR1, AP2B1, and IR, and treated with or without dynasore (Dyn). The total cell lysates (TCL), anti-MYC IP, and IgG IP were blotted with the indicated antibodies. The relative intensities of IRβ and AP2B1 (mean ± SEM; n=3 independent experiments) are shown below.

(E) HepG2 cells stably expressing IR-WT-GFP were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and stained with anti-GFP (IR; green) and anti-AP2B1 (red) antibodies. Two boxed regions (1 and 2) were magnified and shown. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(F) Quantification of the Manders’ coefficients of IR and AP2B1 co-localization in (E) (mean ± SEM; siLuc, n=16; si-p31, n=26; si-p31/siBUBR1, n=12; si-p31/siMAD2, n=11; **p<0.005).

(G) Western blot analysis of cell lysates in (E and F).

Recombinant BUBR1 N-terminal domain (BUBR1N) associated with IR-bound MAD2 WT (Figure 6C). It bound much less efficiently to MAD2 R133E/Q134A (RQ), which was monomeric and contained mutations of two critical residues in αC. p31comet diminished the BUBR1N–MAD2 interaction (Figure 6C), without substantially affecting the IR–MAD2 interaction. p31comet bound weakly to MAD2 RQ, and did not further reduce the residual binding between BUBR1N and MAD2 RQ. Thus, p31comet inhibits the interaction between BUBR1 and IR-bound C-MAD2 in vitro. In human cells, MYC-BUBR1 interacted with IR and AP2B1 at a basal level (Figure 6D). These interactions were enhanced when clathrin-mediated endocytosis of IR was blocked with dynasore. Depletion of p31comet further enhanced these interactions, consistent with a role of p31comet in suppressing IR endocytosis.

In keeping with these protein-binding data, BUBR1, p31comet, and MAD2 could be detected on PM in HepG2 cells with total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy (Figure S4D), and the PM co-localization of IR and BUBR1 was increased by dynasore treatment with or without insulin stimulation (Figure S4E and S4F). We then measured the co-localization efficiency of IR and AP2B1 on the cell surface in control and p31comet-depleted cells (Figure 6E–G). In control cells, IR had a diffusive PM staining, with no clear enrichment in the AP2B1 puncta (Figure 6E). The punctate staining pattern of AP2B1 became more pronounced in p31comet-depleted cells, and IR efficiently co-localized with AP2B1 in these surface puncta (Figure 6E and 6F). Co-depletion of BUBR1 or MAD2 in p31comet-depleted cells reduced the co-localization of IR and AP2B1 (Figure 6F and 6G). Therefore, p31comet attenuates clathrin-mediated endocytosis of IR through suppressing MAD2-BUBR1-dependent recruitment of AP2.

The p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 Module Regulates Insulin Signaling

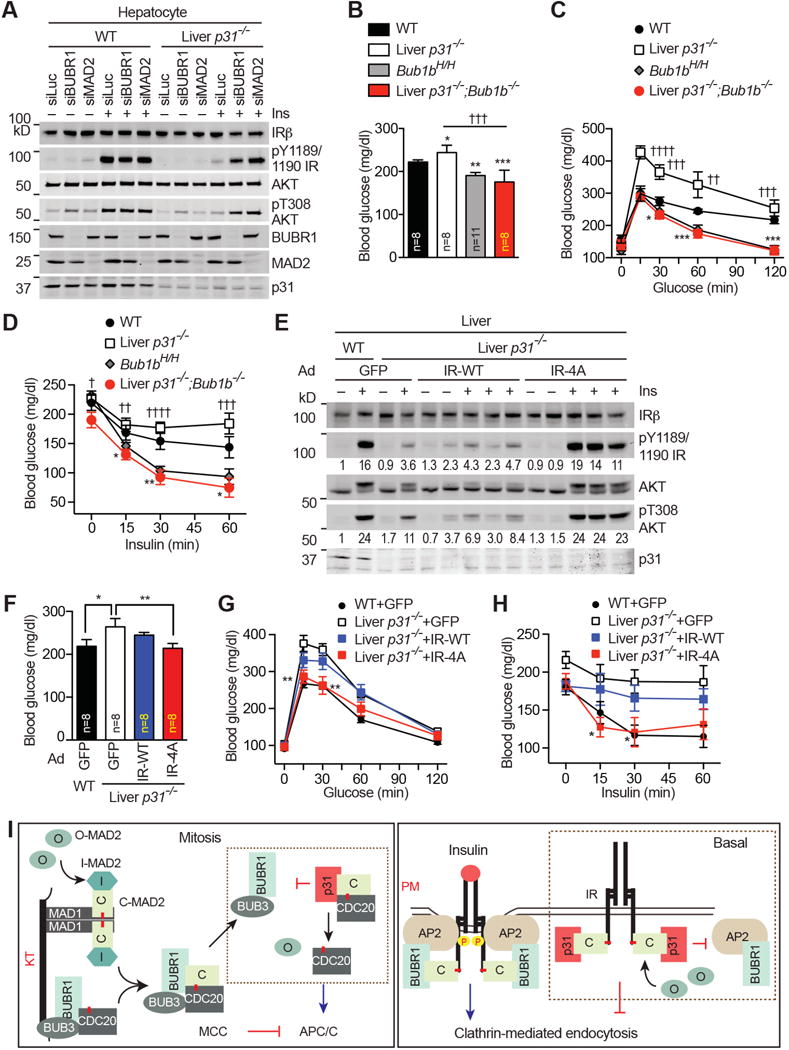

We tested whether the p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 module indeed regulated insulin signaling. Insulin-triggered IR and AKT phosphorylation was markedly reduced in liver-p31−/− hepatocytes, indicative of defective insulin signaling (Figure 7A and S5A). Depletion of BUBR1 or MAD2 from liver-p31−/− hepatocytes significantly restored insulin signaling. Co-depletion of MAD2, BUBR1, AP2B1, or CLTC similarly restored insulin signaling in p31comet-depleted HepG2 cells (Figure S5B and S5C). These results indicate that p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 controls insulin signaling through regulating IR endocytosis.

Figure 7. The p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 Module Controls Insulin Signaling.

(A) Hepatocytes from WT and liver-p31−/− mice were transfected with siRNAs, serum starved, and then treated with 10 nM insulin (Ins) for 5 min. Cell lysates were blotted with the indicated antibodies.

(B–D) Fed blood glucose levels (B), glucose tolerance test (C), and insulin tolerance test (D) of WT, liver-p31−/−, Bub1bH/H, and liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/− mice. At least 8 mice in each group were analyzed. Mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001 versus WT; p†<0.05, ††p<0.01, †††p<0.001, ††††p<0.0001 versus liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/−.

(E) Immunoblots of whole liver lysates of WT and liver-p31−/− mice injected with Ad-GFP, Ad IR-WT or Ad-IR-4A, and treated without or with insulin (Ins). Each lane contains lysate from an individual mouse. The relative band intensities were quantified below.

(F–H) Fed blood glucose levels (F), glucose tolerance test (G), and insulin tolerance test (H) of WT and liver-p31−/− mice injected with Ad-GFP, Ad-IR-WT, or Ad-IR-4A. At least 8 mice in each group were analyzed. Mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 versus liver-p31−/− (Ad-GFP).

(I) Left and right panels depict the roles of the p31comet-MAD2-BUBR1 module in mitosis and insulin signaling, respectively. The red lines in MAD1, CDC20, and IR indicate the MAD2-interacting motif (MIM).

We next generated liver-specific p31comet and BUBR1 double knockout (liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/−) mice, and tested if BUBR1 ablation rescued the metabolic defects of liver-p31−/− mice. Similar to Bub1bH/H mice, liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/−mice were normal at birth, but only attained 40% of normal weight at 3 weeks. Strikingly, liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/−mice showed hypoglycemia in the fed state (Figure 7B), increased glucose tolerance (Figure 7C), and insulin hypersensitivity (Figure 7D), phenotypes similar to those in Bub1bH/H mice and opposite to those of liver-p31−/− mice.

The cell and nuclear sizes of hepatocytes in liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/− mice were larger than those of hepatocytes in the single knockout animals (Figure S5D and S5E). The percentage of hepatocytes with 8N or greater DNA content was higher in liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/− mice (Figure S5F). This increased polyploidization is likely due to the complete loss of Bub1b in the liver. Despite this striking ploidy change, liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/− mice retained insulin and glucose hypersensitivity seen in Bub1bH/H mice. These results do not support a causal link between polyploidization and insulin resistance. We could not perform single-cell sequencing of p31−/−;Bub1b−/− hepatocytes to ascertain their aneuploidy status, as live-cell sorting produced no intact cells.

Because IR-4A does not undergo unscheduled endocytosis caused by p31comet inactivation (Figure 5), we hypothesized that expression of IR-4A might suppress the metabolic phenotypes of liver-p31−/− mice. Expression of IR-4A-GFP, but not IR-WT-GFP, rescued the insulin signaling defects in HepG2 cells depleted of p31comet (Figure S6A and S6B) and in primary hepatocytes isolated from liver-p31−/− mice (Figure S6C and S6D). Adenovirus-mediated expression of IR-4A, but not IR-WT or GFP, restored insulin-stimulated IR autophosphorylation and activating AKT phosphorylation in the liver of liver-p31−/− mice (Figure 7E). Expression of IR-4A also significantly decreased fed blood glucose levels (Figure 7F), and restored glucose tolerance (Figure 7G) and insulin sensitivity (Figure 7H) in liver-p31−/− mice. These results indicate that p31comet regulates insulin signaling through suppressing the functions of the IR–MAD2 interaction in vivo.

DISCUSSION

Combining mouse genetics, cell biological and biochemical methods, and single-cell genomics, we have discovered a critical role for the p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 module of mitotic regulators in insulin signaling through regulating IR endocytosis (Figure 7I).

In the mouse, p31comet deficiency diminishes IR at PM prior to insulin stimulation and causes defective insulin signaling and metabolic syndrome. The insulin signaling defects caused by p31comet ablation are not limited to the liver, as whole-body p31−/− mice exhibit neonatal lethality whereas liver-specific p31−/− mice are viable. Indeed, p31−/− MEFs exhibited defective insulin-induced adipogenesis (Figure S7A and S7B). Insulin signaling, GLUT4 translocation, and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake were defective in the poorly differentiated p31−/− adipocytes (Figure S7C–E).

While we cannot rule out mitotic defects and low extent of aneuploidy as contributing factors to the metabolic defects in p31comet-deficient mice, two complementary lines of evidence argue against aneuploidy as the determining factor. The first line of evidence involves the use of BUBR1-deficient (Bub1bH/H) mice. These mice harbor aneuploidy in hepatocytes, but are more sensitive to insulin, a phenotype opposite to that of liver-p31−/− mice. Furthermore, liver-specific ablation of BUBR1 rescues the metabolic defects of liver-p31−/− mice, despite increasing polyploidization in hepatocytes. These findings support our conclusion that BUBR1 facilitates IR endocytosis and attenuates insulin signaling. It also indicates that aneuploidy or polyploidy alone is insufficient to produce insulin signaling defects caused by p31comet ablation.

The second line of evidence comes from genetic suppression experiments with transgene expression in the liver. The aneuploidy incidence in p31−/− hepatocytes is surprisingly low. Restoring p31comet expression using viral vectors does not eliminate this low-level aneuploidy, but rescues metabolic and insulin signaling defects in liver-p31−/− mice and hepatocytes. Expression of IR-4A similarly rescues the phenotypes of liver-p31−/− mice and hepatocytes. These results indicate that the insulin signaling defects caused by p31comet ablation are not simply an indirect consequence of aneuploidy. Rather, they strongly support our conclusion that p31comet and MAD2 directly regulate insulin signaling through a physical interaction with IR.

We propose that O-MAD2 can bind to IR without the need for MAD1-mediated conformational activation (Figure 7I). IR-bound MAD2 then recruits AP2 to IR through BUBR1 and promotes IR endocytosis. p31comet prevents IR-bound MAD2 from binding BUBR1 and blocks AP2 recruitment to IR, thereby inhibiting clathrin-mediated endocytosis of IR. Insulin-triggered IR autophosphorylation events have been shown to be required for insulin-stimulated IR endocytosis (Goh and Sorkin, 2013). MAD2 and BUBR1 are also required for insulin-stimulated IR endocytosis in cells without genetic inactivation of p31comet. Thus, insulin stimulation might suppress p31comet-mediated blockade of BUBR1–AP2 association with IR. Future experiments are needed to test this intriguing possibility.

The p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 module specifically regulates endocytosis of cell surface receptors that contain the MIM. The MIM is highly conserved in all vertebrate IR (Figure 4A), suggesting that the metabolic function of the p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 module might have been acquired in vertebrates. The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R) does not contain the MIM, and does not bind to MAD2 (O’Neill et al., 1997). On the other hand, IR might not be the only client cell-surface protein regulated by MAD2. For example, MAD2 can bind to another membrane protein, ADAM17, a metalloprotease with myriad functions in cancer biology (Nelson et al., 1999). We have identified a functional MIM in the cytoplasmic tail of ADAM17 (Figure S7F–H). Additional studies are required to establish the functional significance of this interaction and to systematically identify cell surface proteins that interact with MAD2.

BUBR1 insufficiency in mice causes aging-related disorders (Baker et al., 2004), and conversely BUBR1 overexpression extends lifespan and delays aging in mice (Baker et al., 2013). An evolutionarily conserved function of IR/IGF1R signaling in longevity and aging has been widely documented (Bluher et al., 2003; Kimura et al., 1997). We have now linked BUBR1 to insulin signaling. Future experiments are needed to test whether changes in insulin signaling contribute to the aging phenotypes of mice with altered BUBR1 expression.

Liver-specific ablation of p31comet in mice produces metabolic disorders reminiscent of type 2 diabetes, including insulin resistance. The underlying mechanisms of insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes are complex and not fully understood (Samuel and Shulman, 2012). Our findings presented herein implicate premature IR internalization prior to insulin binding as a potential mechanism underlying insulin resistance. It will be interesting to examine IR levels or localization in liver biopsies of human type 2 diabetes patients.

Our results establish a role of mitotic checkpoint regulators in insulin signaling and metabolic homeostasis. Our study provides a striking example of how an entire branch of key regulators in one cellular process can be repurposed to control another. By virtue of its ability to link signaling pathways originating from kinetochores and the plasma membrane, the p31comet–MAD2–BUBR1 module may offer a potential conduit for extracellular hormones to regulate chromosome segregation and karyotypes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation and Phenotypic Analyses of p31−/− and Liver-p31−/− Mice

The strategy of targeting p31comet (Mad2l1bp) is described in Figure S1. The p31F/F mice were crossed with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the Actin promoter to generate the p31−/− mice, and were mated with transgenic mice expressing Cre recombinase under the Albumin promoter to generate liver-p31−/− mice. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for information of mouse crosses and husbandry, and generation of liver-p31−/−;Bub1b−/−mice.

Tissue histology and immunohistochemistry were performed by an on-campus core facility. Hepatic glycogen content was measured with the glycogen assay kit (Sigma). Glucose and insulin tolerance tests, metabolic profiling, glycogen synthase activity assay, and in vivo insulin signaling assay were performed with established protocols. Prism was used for the generation of all curves and graphs and for statistical analyses. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Viral Infection

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and primary hepatocytes were isolated and cultured following standard protocols. 293FT and HepG2 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with fetal bovine serum. Plasmid transfections into 293FT cells and HepG2 were performed with polyethylenimine (PEI; Sigma) and Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen), respectively. siRNA transfections were performed with Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen). Recombinant adenoviruses and adeno-associated viruses were generated at Agilent Technologies and Vector Biolabs, respectively, and were introduced into mice through tail vein injection. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for adipocyte differentiation and glucose uptake assay, generation of stable cell lines, list of siRNAs, and other details.

Single-Cell Whole Genome Sequencing

Hepatocytes were isolated from WT, liver-p31−/− and Bub1bH/H mice and sorted into single cells with flow cytometry. GenomePlex Single Cell Whole Genome Amplification (WGA4; Sigma) was performed. Library generation and sequencing were performed by an on-campus facility. Sequencing reads were aligned against the reference genome. Copy numbers were estimated using HMMCopy with a bin size of 500 kb. The average gene copy number of each chromosome was calculated, and log2 (copy number/average autosome copy number) was used to classify aneuploidy, with cutoff set at 0.15. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblots

Cleared cell lysates were incubated with antibody-conjugated beads. The proteins bound to beads were eluted with SDS sample buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and quantitative Western blotting. Membranes were scanned with the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details and list of antibodies.

Immunofluorescence, Live-cell Imaging, and Metaphase Spreads

Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed on cells grown on coverslips or on liver sections following standard fixation and staining procedures. Cells were imaged with appropriate objectives on various microscopes. Live-cell imaging was performed on MEFs expressing H2B-mRFP. Metaphase spreads were prepared for MEFs, and images were captured with a Zeiss Axioscope upright microscope. Identical exposure times and magnifications were used for all comparative analyses. Images were analyzed with Image J. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details and for the endocytosis assay.

Flow Cytometry

MEFs pulsed with BrdU for were fixed and stained with FITC-anti-BrdU antibody (BD bioscience) and propidium iodide. Hepatocytes were fixed and stained with propidium iodide. Cells were analyzed with FACSCalibur™ or FACS Aria II SORP (BD bioscience). Data were processed with FlowJo (Ashland, OR). See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Protein Binding Assays

Recombinant MAD2 proteins were purified as described (Luo et al., 2004). BUBR1N (residues 1–370) and mouse p31comet were purified with affinity and conventional chromatography. IR peptides were chemically synthesized. GST-IR (residues 1011-1382) was purchased from Promega. The isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) assay of IR-WT binding to MAD2 was performed as described (Xia et al., 2004). Peptide- or protein-bound beads were used to pull down prey proteins following standard procedures. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures for details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Xuemin Zhang for assistance with generating the p31F/F mice, Jan van Deursen for providing the Bub1bH/H mice and other reagents, Mayuko Hara for performing ITC, Bing Li for preparing BUBR1N, Min Kim for advice on adenovirus production, Ralph DeBerardinis for providing 293FT and HepG2 cells, Vanessa Schmid and Rachel Bruce for single cell sequencing, John Shelton and James Richardson for advice on histological analysis, and Xuelian Luo for advice on protein purification. We are grateful to anonymous reviewers for suggesting the genetic suppression experiments. This work is supported in part by grants from the Clayton Foundation (to H.Y.) and the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR001105 to C.X.). H.Y. is an HHMI Investigator.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.C. designed and performed all experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. X.Z. and C.X. analyzed copy number variation in hepatocytes. H.Y. supervised the project, provided suggestions, and edited the paper.

References

- Baker DJ, Dawlaty MM, Wijshake T, Jeganathan KB, Malureanu L, van Ree JH, Crespo-Diaz R, Reyes S, Seaburg L, Shapiro V, et al. Increased expression of BubR1 protects against aneuploidy and cancer and extends healthy lifespan. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:96–102. doi: 10.1038/ncb2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DJ, Jeganathan KB, Cameron JD, Thompson M, Juneja S, Kopecka A, Kumar R, Jenkins RB, de Groen PC, Roche P, et al. BubR1 insufficiency causes early onset of aging-associated phenotypes and infertility in mice. Nat Genet. 2004;36:744–749. doi: 10.1038/ng1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddinger SB, Hernandez-Ono A, Rask-Madsen C, Haas JT, Aleman JO, Suzuki R, Scapa EF, Agarwal C, Carey MC, Stephanopoulos G, et al. Hepatic insulin resistance is sufficient to produce dyslipidemia and susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 2008;7:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluher M, Kahn BB, Kahn CR. Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science. 2003;299:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1078223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher J, Kleinridders A, Kahn CR. Insulin receptor signaling in normal and insulin-resistant states. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6:a009191. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayrol C, Cougoule C, Wright M. The beta2-adaptin clathrin adaptor interacts with the mitotic checkpoint kinase BubR1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:720–730. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao WC, Kulkarni K, Zhang Z, Kong EH, Barford D. Structure of the mitotic checkpoint complex. Nature. 2012;484:208–213. doi: 10.1038/nature10896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fava LL, Kaulich M, Nigg EA, Santamaria A. Probing the in vivo function of Mad1:C-Mad2 in the spindle assembly checkpoint. EMBO J. 2011;30:3322–3336. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard J, Pegorier JP. An overview of early post-partum nutrition and metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans. 1998;26:69–74. doi: 10.1042/bst0260069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh LK, Sorkin A. Endocytosis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a017459. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a017459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan RS, Manak MS, Buch HK, Meier MG, Meraldi P, Shah JV, Sorger PK. p31comet acts to ensure timely spindle checkpoint silencing subsequent to kinetochore attachment. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4236–4246. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-03-0216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins JR, Toyoda Y, Hegemann B, Poser I, Heriche JK, Sykora MM, Augsburg M, Hudecz O, Buschhorn BA, Bulkescher J, et al. Systematic analysis of human protein complexes identifies chromosome segregation proteins. Science. 2010;328:593–599. doi: 10.1126/science.1181348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izawa D, Pines J. The mitotic checkpoint complex binds a second CDC20 to inhibit active APC/C. Nature. 2015;517:631–634. doi: 10.1038/nature13911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Kim S, Yu H. Tracking spindle checkpoint signals from kinetochores to APC/C. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Li B, Warrington RT, Hao X, Wang S, Yu H. Defining pathways of spindle checkpoint silencing: functional redundancy between Cdc20 ubiquitination and p31comet. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:4227–4235. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi RL, Lamothe B, Cordonnier N, Mesbah K, Monthioux E, Jami J, Bucchini D. Targeted disruption of the insulin receptor gene in the mouse results in neonatal lethality. EMBO J. 1996;15:1542–1547. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;277:942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knouse KA, Wu J, Whittaker CA, Amon A. Single cell sequencing reveals low levels of aneuploidy across mammalian tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13409–13414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415287111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulukian A, Han JS, Cleveland DW. Unattached kinetochores catalyze production of an anaphase inhibitor that requires a Mad2 template to prime Cdc20 for BubR1 binding. Dev Cell. 2009;16:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London N, Biggins S. Signalling dynamics in the spindle checkpoint response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:736–747. doi: 10.1038/nrm3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Tang Z, Xia G, Wassmann K, Matsumoto T, Rizo J, Yu H. The Mad2 spindle checkpoint protein has two distinct natively folded states. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:338–345. doi: 10.1038/nsmb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Yu H. Protein metamorphosis: the two-state behavior of Mad2. Structure. 2008;16:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell. 2006;10:839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malureanu L, Jeganathan KB, Jin F, Baker DJ, van Ree JH, Gullon O, Chen Z, Henley JR, van Deursen JM. Cdc20 hypomorphic mice fail to counteract de novo synthesis of cyclin B1 in mitosis. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:313–329. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mapelli M, Musacchio A. MAD contortions: conformational dimerization boosts spindle checkpoint signaling. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:716–725. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon HT, Boucrot E. Molecular mechanism and physiological functions of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:517–533. doi: 10.1038/nrm3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michael MD, Kulkarni RN, Postic C, Previs SF, Shulman GI, Magnuson MA, Kahn CR. Loss of insulin signaling in hepatocytes leads to severe insulin resistance and progressive hepatic dysfunction. Mol Cell. 2000;6:87–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio A. The Molecular Biology of Spindle Assembly Checkpoint Signaling Dynamics. Curr Biol. 2015;25:R1002–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson KK, Schlondorff J, Blobel CP. Evidence for an interaction of the metalloprotease-disintegrin tumour necrosis factor alpha convertase (TACE) with mitotic arrest deficient 2 (MAD2), and of the metalloprotease-disintegrin MDC9 with a novel MAD2-related protein, MAD2beta. Biochem J. 1999;343:673–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill TJ, Zhu Y, Gustafson TA. Interaction of MAD2 with the carboxyl terminus of the insulin receptor but not with the IGFIR Evidence for release from the insulin receptor after activation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10035–10040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak M. The insulin and insulin-like growth factor receptor family in neoplasia: an update. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:159–169. doi: 10.1038/nrc3215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel VT, Shulman GI. Mechanisms for insulin resistance: common threads and missing links. Cell. 2012;148:852–871. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotillo R, Hernando E, Diaz-Rodriguez E, Teruya-Feldstein J, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, Benezra R. Mad2 overexpression promotes aneuploidy and tumorigenesis in mice. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White MF. Insulin signaling in health and disease. Science. 2003;302:1710–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.1092952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia G, Luo X, Habu T, Rizo J, Matsumoto T, Yu H. Conformation-specific binding of p31comet antagonizes the function of Mad2 in the spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 2004;23:3133–3143. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Li B, Tomchick DR, Machius M, Rizo J, Yu H, Luo X. p31comet blocks Mad2 activation through structural mimicry. Cell. 2007;131:744–755. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.