Abstract

Background and purpose

There is increasing evidence that several commonly performed surgical procedures provide little advantage over nonoperative treatment, suggesting that doctors may sometimes be inappropriately optimistic about surgical benefit when suggesting treatment for individual patients. We investigated whether attitudes to risk influenced the choice of operative treatment and nonoperative treatment.

Methods

946 Swedish orthopedic surgeons were invited to participate in an online survey. A radiograph of a 4-fragment proximal humeral fracture was presented together with 5 different patient characteristics, and the surgeons could choose between 3 different operative treatments and 1 nonoperative treatment. This was followed by an economic risk-preference test, and then by an instrument designed to measure 6 attitudes to surgery that are thought to be hazardous. We then investigated if choice of non-operative treatment was associated with risk aversion, and thereafter with the other variables, by regression analysis.

Results

388 surgeons responded. Nonoperative treatment for all cases was suggested by 64 of them. There was no significant association between risk aversion and tendency to avoid surgery. However, there was a statistically significant association between suggesting to operate at least 1 of the cases and a "macho" attitude to surgery or resignation regarding the chances of influencing the outcome of surgery. Choosing nonoperative treatment for all cases was associated with long experience as a surgeon.

Interpretation

The discrepancy between available evidence for surgery and clinical practice does not appear to be related to risk preference, but relates to hazardous attitudes. It appears that choosing nonoperative treatment requires experience and a feeling that one can make a difference (i.e. a low score for resignation). There is a need for better awareness of available evidence for surgical indications.

The surgeon’s decision to recommend surgical or non-surgical treatment may not be based solely on evidence. An increasing number of well-designed studies show no benefit—or marginal benefit—of surgical treatment over non-surgical treatment for certain orthopedic procedures such as meniscectomy in middle-aged patients and osteosynthesis of clavicular, distal radial, or proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients (Arora et al. 2011, Robinson et al. 2013, Sihvonen et al. 2013, Rangan et al. 2015, Thorlund et al. 2015, Kise et al. 2016). Unnecessary operations draw resources from areas in healthcare where patients could benefit more. Still, these surgical treatments are common.

There are several possible reasons for why orthopedic surgeons recommend surgical treatment in cases where non-surgical treatments may be preferable. Seeing the radiographs of a displaced fracture that the surgeon knows that he can reduce and fix makes it counterintuitive to reason that nonoperative treatment would be equally effective. In this situation, the surgeon may tend not to believe in the results of the studies mentioned above, referring to study weaknesses such as inclusion criteria that are too narrow or too wide. As statistical mean values are usually reported, and all patients are different, it can always be argued that a certain patient would be an exception. Moreover, when the surgeon feels unable to decide whether a patient would benefit from surgery, he or she might feel compelled to operate in order not to deprive the patient of the possible benefit.

The surgeon’s task is to find the right treatment for each individual patient by weighing up the expected benefits against the expected risks and disadvantages (Verra et al. 2016). In this decision-making process, it is likely that general risk preferences play a role. Furthermore, surgeons’ decisions to operate could possibly be associated with hazardous attitudes to surgery. Recently, Bruinsma et al. (2015) reported that about one-third of practicing orthopedic and trauma surgeons in an international sample showed high levels of hazardous attitudes. In another study (Kadzielski et al. 2015), a correlation was found between high levels of these hazardous attitudes and the incidence of complications after surgery. These findings seem to suggest that hazardous attitudes may have some role in explaining why orthopedic surgeons operate too much. We tried to determine whether risk preferences and hazardous attitudes of orthopedic surgeons are associated with the likelihood of recommending surgical treatment

Our primary hypothesis was that surgeons who are averse to risk would be more likely to suggest non-surgical treatment than surgeons who are risk-neutral or risk-seeking. Our secondary hypothesis was that surgeons with a tendency to self-overestimation (macho attitudes) or other hazardous attitudes would prefer surgical treatment to non-surgical treatment.

Methods

In order to collect information about surgeons’ individual risk preferences and hazardous attitudes, an online survey was conducted. From the 1,147 members of the Swedish Orthopedic Association, 201 were excluded because their workplace would not be expected to deal with adult humeral fractures. The remaining 946 surgeons were invited by e-mail to anonymously participate in an online survey with the aim of studying the decision-making process in orthopedic surgery.

The survey was in 4 parts and took about 6–8 minutes to answer.

Measurement of tendency to operate

In the first part of the survey, a frontal radiograph of a moderately displaced 4-fragment proximal humeral fracture was presented (Figure 1). Alongside the frontal radiograph, 5 different patient descriptions were presented, ranging from a healthy and physically active 64-year-old, well-educated man to a sickly woman of 83 (Table 1). For each patient description, the respondent was asked to choose between 4 treatments: osteosynthesis, prosthesis, reverse prosthesis, or no surgery. Thus, 3 treatment recommendations involved a surgical procedure and 1 recommendation did not. The number of cases recommended for surgery was summed up to give a measure of tendency to operate. The measure took on values from 0 to 5, and the greater the value, the greater was the doctor’s tendency to operate. In addition, the responses were categorized as no surgery versus any kind of surgical procedure.

Figure 1.

The radiograph shown in the survey; the same for all 5 patient descriptions.

Table 1.

Treatment choices of the 354 surgeons included in the final analysis. The cases are presented in order of age. In the survey, the order was different

| Osteo- synthesis |

Hemi- arthroplasty |

Reverse shoulder prosthesis |

Non- operative treatment |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64-year-old man. Married. Works as an organizational consultant. | ||||

| Goes to the gym now and then. Plays tennis every week. Healthy. | 76% | 3% | 3% | 18% |

| 69-year-old married lady. Former history teacher. Likes picking | ||||

| mushrooms and travelling. Orally treated diabetes. | 51% | 10% | 5% | 34% |

| 73-year-old man. Married. Plays golf. Hobby carpenter. Hunting. | ||||

| Smokes. Drinks some alcohol. Slight hypertension. | 39% | 12% | 4% | 45% |

| 80-years-old woman. Lives alone without home help. | ||||

| Likes walking. Plays bridge. Healthy. | 17% | 12% | 9% | 62% |

| 83-year-old woman. Lives alone without home help. Slight disability | ||||

| of the other arm after stroke. | 13% | 13% | 9% | 65% |

Surgical experience

In the second part of the survey, the surgeon’s experience was estimated from the number of years spent working in an orthopedic department (resident; 0–5, 6–10, or >10 years as a consultant) and from the number of humeral fractures operated during the previous year (0–5, 6–10, 11–20, > 20 operations per year). The surgeon was also asked to register as "male" or "female" and to state which hospital he or she was working at.

Measurement of risk preferences

The third part of the survey focused on risk preferences, using a risk-preference elicitation task according to Sutter et al. (2013). The task consisted of a series of binary choices between receiving a secure amount of money increasing from 0 SEK to 10,000 SEK in steps of 1,000 SEK and a 50:50 gamble with outcomes of 10,000 SEK or 0 SEK. We eliminated 20 respondents who gave inconsistent answers or who most likely did not reveal their true preferences (by either always choosing safe option or always choosing a gamble in all 11 items). The answers to the risk task were summarized into a binary variable indicating whether an individual was averse to risk (i.e. preferred a safe option of receiving less than 5,000 SEK rather than a 50% chance of winning 10,000 SEK).

Surgeon hazardous attitude scale

The fourth part of the survey focused on hazardous attitudes. We used an instrument based on "the hazardous attitude scale aviation" developed by the US Federal Aviation Administration and the Canadian Air Transportation Administration (Hunter 1995, 2009). The instrument was designed to measure 6 hazardous attitudes that adversely influence judgement: macho attitude, impulsiveness, anti-authority, resignation, worry/anxiety, and self-confidence. According to Hunter (2009), an adaptation of the instrument for driving cars could predict the risk of traffic accidents in American college students, although the original reference was a conference presentation. The instrument has also been adapted for American orthopedic surgeons and has been shown in a study of 31 surgeons to correlate with the rate of patient readmission for any particular surgeon (Kadzielski et al. 2015). We translated that version to Swedish, with adaptation to the Swedish healthcare system. The surgeons were presented with 30 statements (5 statements for each attitude) and asked to choose one alternative on a 5-item Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). The points for the 5 statements for each attitude were summed, giving values between 5 and 25. A typical statement regarding macho attitude was "I like technically challenging surgeries" (see Supplementary data).

Statistics, primary hypothesis

The predefined primary hypothesis was that tendency to operate was associated with risk preferences, as measured by the risk task according to Sutter et al. (2013). To account for the count nature of the variable indicating tendency to operate and due to intuitive interpretation of the results (as opposed to odds ratio in logistic regression (Zou et al. 2004)), Poisson regression was conducted. The analysis plan was to take account of the similarity of doctors working in the same hospital due to local surgical culture or hospital routines. The hypothesis was therefore tested using a Poisson regression model with robust standard errors clustered at the hospital level. A binary variable describing risk preferences was used as a single explanatory variable. One of the main assumptions of Poisson regression is equidispersion. The likelihood ratio test fails to reject the hypothesis of equidispersion (μ = 2.76, var =3.21; p = 0.2).

Explorative analysis

In order to further explore which personal traits might be associated with one’s decision to operate, we expanded the set of covariates in the Poisson regression with the tendency to operate as a dependent variable. The covariates included all 6 attitudes from the modified surgeon hazardous attitude scale, risk aversion, sex, and time working as an orthopedic specialist.

The tendency to operate can be operationalized in different ways. It might be that surgeons are more inclined to do surgery or less inclined; hence, the best way to measure such a tendency to operate is on an ordinal scale, as in the primary analysis. However, it can be claimed that for a given fracture, none of the surgeries is needed in any of the cases listed in the survey, and hence either doctors suggest surgery in cases in which nonoperative treatments could also be suggested or they avoid surgery as long as nonoperative treatment can give similar results. Thus, doctors who would suggest surgery to any patient in the survey may have similar attitudes, which are quite different from the attitudes of those who are very conservative and do not suggest surgery in any of the cases. To investigate the tendency to operate, defined in a more conservative way (operate or not at all), we summarized the tendency to operate into a binary variable that took on a value of 1 if a surgeon recommended at least one surgery in any of 5 cases, or 0 otherwise. We therefore conducted similar regression analysis on the binary variable using the same covariates as for the count variable. All analyses were performed using STATA software. Tests were two-tailed, and any p-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

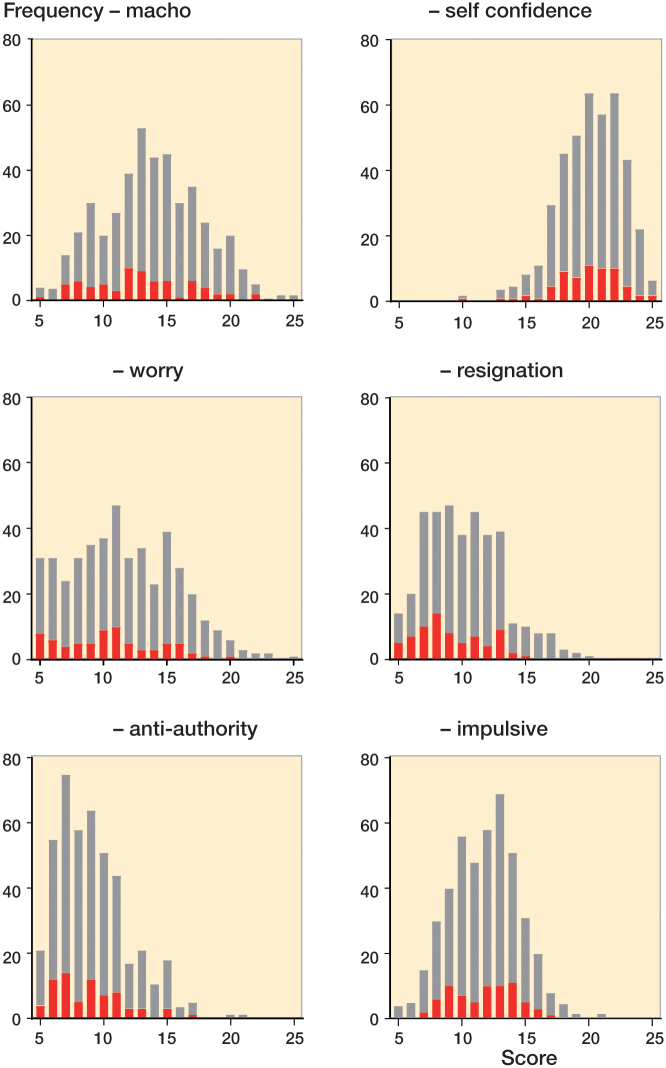

We collected 388 responses. 14 surgeons submitted unfinished surveys and were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 374 surgeons, 20 revealed inconsistencies in their risk task answers, leaving 354 surgeons with complete and consistent data (from 62 hospitals). 17% of them were women. On average, our respondents conducted 2 shoulder fracture operations per year. The majority of respondents had spent more than 5 years working at an orthopedic department. 64 surgeons recommended nonoperative treatment for all cases. 51% of the surgeons in the sample could be classified as being averse to risk. Visual inspection showed a reasonable dispersion of the attitude measurements, with a tendency of a floor effect—especially regarding worry (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of hazardous attitudes. Possible values range from 5 (lowest Likert score for all questions) to 25 (highest score for all questions). Number of respondents who recommended nonoperative treatment for all cases is shown in red.

Primary hypothesis

Surgeons who were averse to risk recommended surgery for an average of 2.7 of the 5 case descriptions, while surgeons who were either risk-neutral or risk-seeking recommended 2.8 on average. The Poisson regression model with clustered standard errors at the hospital level showed that the rate of recommending one more surgery for risk-averse surgeons was 4% lower than for risk-neutral or risk-seeking surgeons, but this result was not statistically significant (p = 0.6) (Table 2, model 1, see Supplementary data). Thus, we found no support for our primary hypothesis that risk-averse surgeons are less likely to recommend surgical treatment.

Tendency to operate as a count variable

The results from the Poisson regression with an extended set of covariates are presented in Table 2 as model 2 (see Supplementary data). For a 1-unit increase on a macho attitude scale, the rate of suggesting 1 more surgery increased by 4%, keeping everything else constant. Variables indicating other hazardous attitudes (self-confidence, impulsiveness, anti-authority, worry, and resignation) were not statistically significant in this model. Furthermore, neither sex of the surgeon nor experience was significantly associated with the number of surgeries suggested.

In addition, we conducted multi-level mixed-effects Poisson regression to account for differences in the baseline tendency to operate between hospitals. We accounted for the fact that the doctors from the same hospital might be more alike than doctors from different hospitals, due to common rules, routines, and workplace practice. Thus, hospital was treated as a random effect. We used the following predictor variables: risk-averse, macho, self-confidence, impulsiveness, anti-authority, worry, resignation, experience, and female as fixed effects. The hospital random effects were assumed to be independent from fixed effects and to account for variability between hospitals in characteristics that were not measured by fixed effects (unobservable). The estimated incidence rate ratios in the mixed-effects model were similar to those from the Poisson regression (Table 3, see Supplementary data). Furthermore, using the likelihood ratio test, we rejected the hypothesis that the variance component of hospital random effects was zero (p = 0.001) and hence that the data were structured hierarchically. In other words: hospital-associated factors influenced the decisions.

Tendency to operate as a binary variable

For surgeons with risk-neutral or risk-seeking preferences, 86% recommended surgery in at least 1 out of the 5 cases, while this proportion amounted to 79% among risk-averse surgeons.

Risk-averse surgeons had lower rates of suggesting any operation than risk-neutral or risk-seeking surgeons. This effect was similar regardless of the inclusion of variables measuring hazardous attitudes and doctor’s characteristics, but was not statistically significant (model 1 and model 2 in Table 4, see Supplementary data). For risk-averse surgeons, the rate of recommending any surgery was 8% lower than for risk-neutral or risk-seeking surgeons (p = 0.07).

Macho attitude was again positively associated with a tendency to operate (Table 4, model 2, see Supplementary data). For a 1-unit increase on the macho attitude scale, the incidence ratio that a surgeon recommended at least 1 surgery increased by 2%. These findings show that the effect of macho attitude on tendency to recommend surgery was robust in this study. Resignation attitude had a similar effect to that of macho attitude: for a 1-unit increase on the resignation attitude scale, the incidence ratio that a surgeon recommended at least one surgery increased by 2%. Moreover, a 1-unit increase on the scale for impulsivity decreased the incidence ratio of suggesting any surgery by 2%, but this was not statistically significant (p = 0.06). Thus, it appears that surgeons who feel that they have little control over their destiny have a higher tendency to operate.

Experienced surgeons were less likely to recommend any surgery. The incidence rate for surgeons with at least 10 years of experience was 13% lower than the incidence rate for resident surgeons. The remaining variables were not associated in a statistically significant way with the tendency to operate.

Treatment suggestions for the different fracture cases

The choice of nonoperative treatment varied considerably across patient cases, ranging from 18% for the tennis-playing 64-year-old man to 65% for the sickly old lady. For each increase in age, the choice of nonoperative treatment increased also. Similarly, for each increase in age, the choice of osteosynthesis increased. Arthroplasty was seldom suggested (Table 1).

Discussion

Our primary hypothesis was that surgeons with aversion to risk would be less prone to recommend operations for proximal humeral fractures. This hypothesis was not supported. The exploratory analysis, however, suggested that attitudes that were considered to be hazardous had a strong influence on the choice of treatment, although in a more complex way than expected. Regardless of the specification of the analytical model, macho attitude was strongly associated with a tendency to operate.

Another personality trait thought to be hazardous, namely resignation, was unexpectedly associated with a preference for operative treatment. The explanation could be that an operation is seen as the standard choice. It appears that both those who like doing surgery (macho), and those who have a fatalistic attitude (resignation) follow the routines to operate.

Surgeons with more experience tended to operate less. Experience involves memories of failed cases, which might reduce surgical optimism. Experience might also date back to a time when nonoperative treatment was the norm.

It must be noted that these observations are only exploratory, and that traits other than macho attitude showed statistically significant associations only for the binary variable (operate any case: yes or no). However, some of the associations were quite strong. For a 1-unit increase in the macho attitude scale, the rate of suggesting one more surgery increased by 4%. As the macho scale answers ranged from 5 to 25, this suggests that this attitude has a profound influence.

We originally planned to use a count variable as a measure of the tendency to operate (operating 0 to 5 cases). Using this variable, only macho attitude came out as being statistically significant. The finding of more associations with the binary variable (operate any case) suggests a categorical difference. It is a more dramatic position to completely rule out surgery for these cases, and this position appeared to be associated with several personality traits. In contrast, if one does not rule out surgical treatment, choosing which cases were suitable appeared to be less sensitive to personality, except for a macho attitude.

In the real world, many patients similar to our 5 hypothetical cases undergo surgery, but there is not much support for this in the literature (Olerud et al. 2011). Indeed, there is evidence to the contrary (Launonen et al. 2015, Rangan et al. 2015). In spite of several attempts in large-scale multicenter randomized trials, no benefit of surgery has been shown (Rangan et al. 2015). Moreover, there is no support in the literature for any differences in strength of indication between our 5 hypothetical cases, even though it might seem obvious that a frail elderly person should not be exposed to surgery if it can be avoided. Indeed, the choice of nonoperative treatment in our study was directly related to patient age, as has also been reported previously (Hageman et al. 2015).

The rate of complete and consistent responses to the survey was 37%. This is a comparatively high rate. The fact that 51% of the respondents recommended nonoperative treatment for patients over 65 years of age seems to reflect the choice of treatment in the national Swedish fracture register (2016), where on average 55% of AO type 11C fractures were treated nonoperatively (https://stratum.registercentrum.se). Because of the similarities of the healthcare systems in the countries of the Nordic Orthopedic Federation, the respondents in the survey can be regarded as being representative of the readership of Acta Orthopedica.

In conclusion, it appears that attitudes strongly influence the decision to operate. Increased general awareness of the results of recent high-quality studies and systematic reviews might reduce this influence.

Supplementary data

Table 2–4, and the "surgeon hazardous attitude scale" (including the Swedish translation) are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1298353.

We are grateful to all our colleagues for their time and effort in responding to the survey: thank you very much!

AM: planning, adaptation of questionnaires to Swedish conditions, creation of survey website, collection and handling of all raw data, interpretation of results, and writing and revision of the manuscript. GT: planning, choice of risk estimation instrument, interpretation of results, and revision of the manuscript. KP: planning, choice of risk estimation instrument, statistical evaluation, interpretation of results, and writing and revision of the manuscript. PA: original idea, planning, adaptation of the questionnaires to Swedish conditions, interpretation of results, writing of the first draft, and revision of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

References

- Arora R, Lutz M, Deml C, Krappinger D, Haug L, Gabl M.. A prospective randomized trial comparing nonoperative treatment with volar locking plate fixation for displaced and unstable distal radial fractures in patients sixty-five years of age and older. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93(23): 2146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinsma W E, Becker S J, Guitton T G, Kadzielski J, Ring D.. How prevalent are hazardous attitudes among orthopaedic surgeons? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473(5): 1582–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hageman M G, Jayakumar P, King J D, Guitton T G, Doornberg J N, Ring D.. The factors influencing the decision making of operative treatment for proximal humeral fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24(1): e21–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D R. Airman research questionnaire: methodology and overall results. http://wwwdticmil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a300583pdf. 1995.

- Hunter D R. Dealing with hazardous attitudes. In: http://wwwavhfcom/html/Evaluation/GMasonHazAttitudeScale/Hazard_Attitude_Traininghtm. 2009.

- Kadzielski J, McCormick F, Herndon JH, Rubash H, Ring D.. Surgeons’ attitudes are associated with reoperation and readmission rates. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473(5): 1544–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kise N J, Risberg M A, Stensrud S, Ranstam J, Engebretsen L, Roos E M.. Exercise therapy versus arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for degenerative meniscal tear in middle aged patients: randomised controlled trial with two year follow-up. BMJ 2016; 354: i3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launonen AP, Lepola V, Flinkkila T, Laitinen M, Paavola M, Malmivaara A.. Treatment of proximal humerus fractures in the elderly: a systemic review of 409 patients. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(3):280–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olerud P, Ahrengart L, Ponzer S, Saving J, Tidermark J.. Hemiarthroplasty versus nonoperative treatment of displaced 4-part proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20(7): 1025–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangan A, Handoll H, Brealey S, Jefferson L, Keding A, Martin B C, et al. Surgical vs nonsurgical treatment of adults with displaced fractures of the proximal humerus: the PROFHER randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015; 313(10): 1037–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson C M, Goudie E B, Murray I R, Jenkins P J, Ahktar M A, Read E O, et al. Open reduction and plate fixation versus nonoperative treatment for displaced midshaft clavicular fractures: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95(17): 1576–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itala A, Joukainen A, Nurmi H, et al. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(26): 2515–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter M, Kocher M G, Glätzle-Rüetzler D, Trautmann S T.. Impatience and uncertainty: Experimental decisions predict adolescents’ field behavior. American Economic Review. 2013; 103(1): 510–31. [Google Scholar]

- Thorlund J B, Juhl C B, Roos E M, Lohmander L S.. Arthroscopic surgery for degenerative knee: systematic review and meta-analysis of benefits and harms. Br J Sports Med 2015; 49(19): 1229–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verra W C, Witteveen K Q, Maier A B, Gademan MG, van der Linden H M, Nelissen R G.. The reason why orthopaedic surgeons perform total knee replacement: results of a randomised study using case vignettes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2016; 24(8): 2697–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol 2004; 159(7): 702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.