Abstract

Background and purpose

Orthopedics and especially joint replacement surgery have had more than their fair share of unsuccessful innovations that have violated widely endorsed principles for the introduction of new surgical innovations. We aimed to investigate (1) the trends in the use of the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR), the ASR hip resurfacing (ASR HRA) and the ASR XL total hip replacement (ASR XL THR) system with very different market approval processes and (2) whether their use was corroborated by clinical trials published in the peer-reviewed literature.

Methods

The literature was searched for any clinical studies that reported outcomes of the BHR, ASR HRA and ASR XL THRs. Data from 7 national hip arthroplasty registers were collected and the number of annually implanted devices was matched to those reported in the literature.

Results

The cumulative number of implanted and published BHRs grew proportionally with a small lag. The growth of implanted BHRs started to decline at the same time as the ASR HR was introduced. With regard to ASR HRAs, the cumulative proportion of implanted hips and those included in the published studies grew disproportionately after the introduction of the ASR in 2003. For ASR XL THRs, the disproportionality is even higher.

Interpretation

The adoption of ASR hip replacements did not follow the proposed stepwise introduction of orthopedic implants. The adoption and use of any new implant should follow a strict guideline and algorithm even if the theoretical basis or the results of preclinical studies are excellent.

The very foundation of current health care management is to have a robust, evidence-based approach. The IDEAL Collaboration (Idea, Development, Exploration, Assessment, Long-term follow-up) proposes that such an approach is characterized by: “the promotion of unbiased, highly reliable types of evidence” (Barkun et al. 2009). A pragmatic approach taken by Haynes (1999) states that any innovation should work under ideal circumstances (“Can it work?”) as well as the usual circumstances (“Does it work in practice?”). Unfortunately, orthopedics and especially the field of joint replacement surgery have had more than their fair share of unsuccessful innovations that have violated these principles.

A detailed stepwise algorithm for the introduction of new orthopedic implants was established by Malchau (Malchau 2000, Malchau et al. 2011). All new implants should go through a rigorous 4-step introduction process: preclinical step and clinical steps 1–3. The preclinical step includes preclinical testing, i.e., in hip simulators (“Can it work?”). Very similar guidelines related to the catastrophic failure of the 3M Capital Cemented Hip System in England in the 1990s were outlined by the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS) (2001).

In the early 2000s, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States exempted new devices from clinical trials if manufacturers could prove similarity to another product already on the market (Cohen 2012, Day et al. 2016). In the European Union, a similar protocol was followed which granted approval (CE label) for any metal-on-metal (MoM) hip implant as long as the manufacturer was able to show similarity to a product already on the market (Cohen 2012). Due to the similarity between the two approval procedures, in many cases the introduction of MoM implants in the United States and the European Union failed to meet any of the Clinical Step 1 processes outlined by Malchau et al. (2011), namely, open prospective studies (usual circumstances, “Does it work?”). The Articular Surface Replacement (ASR) MoM hip resurfacing (HR) system and the ASR XL total hip replacement (THR) implant (Depuy Orthopaedics, Warsaw, IN), both of which led to catastrophic results, and many other hip resurfacing and large-diameter MoM THR designs were introduced claiming similarity to other MoM implants or their characteristics already on the market (U.S. FDA 2005, 2008). In contrast, the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing (BHR, Smith & Nephew, Warsaw, IN) system and the Conserve+ (Wright, Memphis, TN) implant were the first second-generation MoM hip resurfacing designs on the market to undergo thorough preclinical and clinical testing (U.S. FDA 2006a, 2006b).

Our main hypothesis is that the ASR hip replacement system was adopted into use far too rapidly and lacked the support of clinical results from published studies in the peer-reviewed literature. Hence, in this paper we aim to investigate (1) the trends in the use of the BHR and ASR hip replacements and (2) whether their use was corroborated by clinical trials published in the peer-reviewed literature.

Materials and methods

The MoM hip replacement brands investigated

3 different MoM hip arthroplasty brands were investigated: the BHR implant, the ASR HRA and the ASR XL THR implants.

Identification of studies

We searched for clinical studies in the PubMed and Scopus databases. The search strategies and the PRISMA flow chart of the study selection are shown in Supplementary data, files 1–3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A study was eligible if (1) it included an original patient cohort operated on with either the BHR, ASR HRA or ASR XL THR implants and, (2) the study clearly reported survival rate, revision rate or a failure rate. We defined an original patient cohort as a population of patients followed for a disclosed period and primarily operated on with a certain implant within a certain time interval at a disclosed hospital(s). If more than 1 implant was used and the number of patients for each implant was not given, the study was excluded. Furthermore, a study was excluded if (1) it included patients referred from somewhere other than the hospital(s) where the study was carried out (violation of eligibility criteria 1), or (2) more than 1 implant was used but the revisions were not stratified by the implant.

If a study included a study arm or a subcohort of a study arm that had been included in a previous study with different follow-up periods, both studies were included since these were considered separate reports.

All the records retrieved from the 2 databases using our search strategy were screened. The screening of abstracts was done by two of the authors (AR and LL). All studies that outlined the use of any MoM hip implant or a hip implant under a brand name along with any clinical outcome (patient-reported outcome score, survival rate, failure rate, complication rate, revision rate, deaths, metal ion levels, cross-sectional imaging findings) were selected for full-text review and eligibility assessment. Retrieval and eligibility assessment was done by the first author (AR).

Data extraction

No detailed data extraction was carried out. The only data recorded were the number of hips included, the publication year and the type of implant used.

Registry data

Data were collected from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR), the National Joint Registry for England and Wales (NJR), the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register (SHAR), the Finnish Arthroplasty Register (FAR), the New Zealand Joint Registry (NZJR), the Danish Hip Arthroplasty Register (DHR) and the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register (NAR). The annual reports available in the websites of respective registries were screened and the numbers of BHR, ASR hip resurfacings and ASR XL THR annually implanted were recorded. Data from the FAR were retrieved directly.

Full historical data on the use of the BHR were available from the AOANJRR, SHAR, FAR, NZJR, DHR and NAR. The annual report of the NJR was first published in 2004. Therefore, data on the annual number of implanted BHRs in England and Wales between 1997 and 2002 were lacking. Full historical data on the use of the ASR hip replacements was available from all 7 registries.

Statistics

Data from published studies and registries were collected yearly ending in 2013. Since ASR hip replacements were recalled by the manufacturer in September 2010 and their use halted in 2011 at the latest, further data collection was not deemed feasible. The annual increase in both the implanted hips reported in the registries and the increase in the hips included in the published clinical studies were calculated. For each year, a running cumulative proportion of implanted and reported hips was calculated. This was achieved by dividing the cumulative number of implanted and reported hips in each year by the total cumulative number in the year 2013. Following this, the proportion of both implanted and reported hips was 1.0 in 2013 and smaller in the preceding years. The primary variable of interest was a time series consisting of cumulative number of implanted and reported hips as described above.

Results

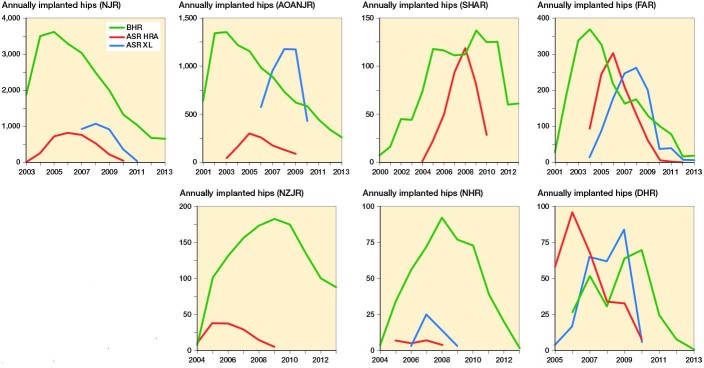

89 studies were identified. The details of all studies included are listed in Supplement 4. In the AOANJRR, NJR, FAR and DHR, the growth in implanted BHRs started to decline at the time the ASR HRA was first introduced. Moreover, the use of the BHR peaked 1 to 2 years prior to the peak in use of the ASR HRA (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Annual implanted Birmingham Hip Resurfacings (BHR), Articular Surface Replacement hip resurfacings (ASR HRA) and ASR XL total hip arthroplasties (ASR XL) in 7 registries between 1999–2013: NJR, AOANJR, SHAR, FAR,) NZJR, NHR, and DHR.

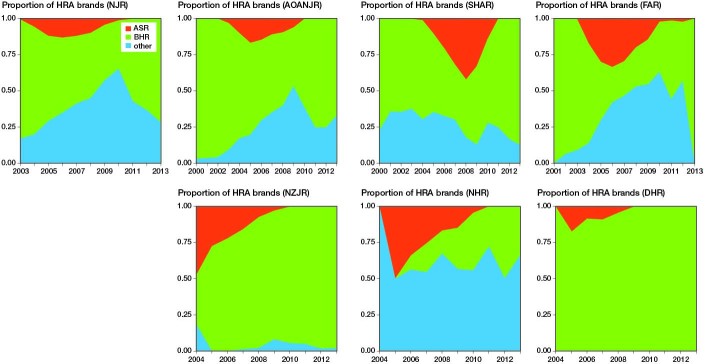

The trend in the use of the BHR was similar across AOANJRR, NJR, SHAR and FAR (Figure 2). In the 3 other registries variable patterns were seen. The proportion of other HR designs, especially the ASR HRA, increased rapidly from 2004. However, in 2010 the proportion of BHRs started to rise and the use of ASR came to an end due to the recall in September 2010.

Figure 2.

Yearly proportion of HRA brands in the registries: NJR, AOANJR, SHAR, FAR, NZJR, NHR, and DHR.

In the studies that reported the results of the 3 implants, the number of hips included in the studies varied greatly from year to year (Supplementary data file 5).

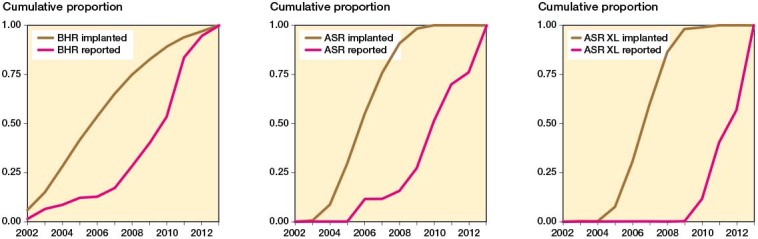

Figure 3 shows the relative proportion of reported and implanted hips annually. In 2013, both cumulative proportions reached 100% or a ratio of 1.0 (see Figure 3). With the BHRs, a steady growth in the hips included in the published studies was seen, but in 2007 a rapid increase occurs which matches the overall growth in implanted hips. With regard to ASR HRAs and ASR XL THRs, the cumulative proportions of implanted hips and those included in the published studies grew disproportionately after the introduction of the ASR in 2003. The first study that included patients operated on with the ASR XL THR was published in 2010 (Langton et al. 2010). In the same year, the ASR hip system was recalled.

Figure 3.

Annual cumulative proportion (brown lines) of implanted Birmingham Hip Resurfacings (BHR), Articular Surface Replacement hip resurfacings (ASR), and ASR XL total hip arthroplasties (ASR XL) according to registries and annual cumulative number of hips reported in the peer-reviewed literature (red lines), i.e., when 50% of the total cumulative number of BHRs were implanted in 2006, approximately 10% of all patients included in the peer-reviewed studies were available in the literature, when 90% of the total cumulative number of ASR HRAs were implanted in 2008, approximately 10% of all patients included in the peer-reviewed studies were available in the literature, and when 95% of the total cumulative number of ASR XL THAs were implanted in 2008, approximately 0% of all patients included in the peer-reviewed studies were available in the literature.

Discussion

An evidence-based approach to the introduction of surgical innovations is fundamental (Table 1) (Haynes 1999, Malchau 2000, McCulloch et al. 2009). This is especially true for joint replacement surgery since “the probability of success of modern innovations is very low due to the long-term success enjoyed by contemporary THA”, as Malchau et al. (2011) stated, and as also stressed by the Balliol Collaboration behind the IDEAL guidelines (McCulloch et al. 2009). Unfortunately, the field of joint replacement surgery has experienced very little success in achieving a rigorous stepwise introduction process (Nieuwenhuijse et al. 2014). The “3M disaster” struck the UK in 1990 (Royal College of Surgeons of England 2001). The 3M Capital Hip was intended to be similar to the Charnley Hip with only slight modifications. These slight modifications had, however, a substantial adverse effect on the survival of the implant, and it was subsequently recalled. The current MoM disaster is the result of an identical series of catastrophic mistakes (Cohen 2011, 2012). The open prospective studies required in Clinical Steps 1 and 2 of the stepwise introduction of implants suggested by Malchau (2000) and the clinical trials in the RCS 2001 recommendation are the responsibility of individual surgeons.

Table 1.

Comparison and suggested equality of 3 different recommendations related to introduction of orthopedic innovations

| Stepwise introduction of new implant technology | Evaluation and stages of surgical innovations | Recommendations about the design and clinical evaluation of hip prosthesis |

|---|---|---|

|

Initial step = preclinical testing “…the preclinical testing might increase both the efficacy and the safety of the innovation,…” |

Stages 0–1 = Innovation “pre-human work and development” “Single digit, highly selected patients” “patient safety can often be improved through iterative animal studies, use of simulators or augmented reality” |

Phase I = Preclinical trials “Full evaluation requires thorough pre-clinical trials, e.g., by radio-stereometric analysis of stem migration,…” |

|

Clinical step 1 = Prospective randomized studies “open prospective and preferably randomized trial that includes a minimum of patients but yields a relevant evaluation” “Results from this first step determine whether further clinical evaluation is worthwhile” |

Stage 2a = Development “attempts to replicate reliably early results should be made” |

Phase II = Clinical trials “Ideally, randomized controlled trials should be carried out to evaluate the performance of prostheses used for total hip replacement.” |

|

Clinical step 2 = Multicenter studies “exposing the new procedure to a broader aspect in the orthopaedic community” |

Stage 2b = Early dispersion and exploration “enough reports have been published for the technology to be generally regarded as safe and it is starting to lose its experimental character” |

|

|

Stage 3 = Assessment “The procedure is now part of many surgeons’ practices “ “results have not been described in previously excluded groups” |

||

|

Clinical step 3 = Register studies “to include a continuous control group by using register studies based on large cohorts to reveal early or unusual and potential clinical catastrophic complications” |

Stage 4 = Long-term implementation and monitoring “surgeons to monitor late or rare outcomes” |

Phase III = Post-marketing surveillance “Three alternatives currently exist: (a) a registry; (b) post-market clinical trials; and (c) ad hoc analysis of adverse incidents and user experience.” “It is therefore recommended that a national hip registry should be established.” |

The FDA approved the BHR through premarket approval (PMA) (U.S. FDA 2006, 2009). The ASR XL THR, on the other hand, gained the 510(k) clearance that relies on “proof of similarity” and is most often obtained by non-clinical tests. Moreover, the 510(k) application must state that devices are substantially equivalent. In 2005, the FDA approved the “ASR Acetabular Cup system”, which introduced a MoM THR with femoral head sizes of 39 to 55 mm (U.S. FDA 2005). The predicate devices in the application, i.e., the devices with which similarity was claimed, were the Pinnacle MoM THR and the TRANSCEND MoM THR. Interestingly, the work by Ardaugh et al. (2013) shows that the ancestry of these 2 devices goes as far back as the McKee–Farrar hip and Ring hip prostheses. As late as 2008, the FDA cleared an extension to the “ASR Acetabular Cup System”, namely the “ASR XL Acetabular System” that introduced femoral head sizes of 55 to 63 mm. The “ASR Acetabular Cup System” was named as a predicate device along with the TRANSCEND MoM THR and the “ASR 300 Acetabular Cup system”, of which the latter had undergone no mechanical or clinical tests (U.S. FDA 2007, Ardaugh et al. 2013). The ASR HRA was not, however, approved by the FDA. Interestingly, the ASR femoral head designed for use in hemiarthroplasty surgery was approved using the previous poorly survived TARA implant as the equivalent device. Controversially, although the ASR HRA was not approved by the FDA, it was granted a CE marking in the European Union (Cohen 2011, House of Commons Science and Technology Committee 2012).

Basically, a conceptual model of a healthy adoption of an innovation is a bell-shaped curve when the potential market share is depicted as described in “Diffusion of Innovations” by Rogers in 1962 and which was also co-adopted in surgical innovations by Wilson (2006). The adoption of the ASR XL THA in some registers was clearly too fast, and in some registers the adoption phase can even be considered to be missing. This is most likely due to the marketing psychology, as large-diameter MoM THRs were marketed as being identical to the BHR and other well-functioning HRs, and hence the adoption would not have been a problem. Moreover, large-diameter bearings with a stem were seen as ideal for reducing dislocation rate, and thus they were easily adopted for those patients unsuitable for hip resurfacing. Clearly, this was a disastrous phase as the hip simulator studies did not reveal the in vivo effects of increased modularity (taper–trunnion interface) and subsequent wear (Matthies et al. 2013).

The use of the BHR decreased quickly after the introduction of the ASR HRA. Moreover, there was a clear shift in the use of the hip resurfacing concept away from the BHR, with numerous studies available at the time, to other HR designs, mainly ASR. The adoption of the ASR hip resurfacing device was quite rapid. Again, this was most likely an industry-driven change since the similarity between the 2 was heavily emphasized, and because similarity was also a crucial step in the approval process. Yet again, this was a disastrous phase as the hip simulator studies did not reveal the in vivo effects of reduced clearance and especially the reduced cup hemisphericity on the wear of the bearing couple in the ASR hip (Underwood et al. 2012, Matthies et al. 2014).

The IDEAL guidelines state that after the first stage (“Idea”) comes stage 2a (“Development”). The collaboration behind the IDEAL guidelines demands that “prospective development studies” are performed in stage 2a (Table 1). This can be considered equal to the demand for open prospective studies proposed by Malchau (2000, 2011). Clearly, phase 2a in the IDEAL guidelines and the first clinical step in the Malchau algorithm was too rapid or even lacking during the shift from the BHR to other HR designs, especially ASR HRA.

When data from the registries and from the literature are combined, obvious conclusions can be drawn. In an optimal situation, the number of studies and patients included would match how much the current innovation is used. The assumption is that as the adoption of an innovation spreads, the more people are likely to report the results of the innovations. However, after a certain level of adoption and spreading, a continuous flow of studies is not needed since the results will most likely be the same. With the BHR there was a sufficient number of studies that included adequate numbers of patients to provide evidence of its use following the years of introduction, at least in male patients. To sum up, in the case of BHR we postulate that there was causality between the registry and literature data meaning that the numbers reported in the registry predicted the numbers reported in the literature.

For the ASR hip replacement, there is basically no evidence supporting its use. The use of ASR hip resurfacing peaked in 2007. Prior to 2007, only 1 study had been published (Siebel et al. 2006). The disproportionality and lack of causality between the actual use and the evidence is even more catastrophic with the ASR XL THR. The concept was adopted extremely quickly violating the IDEAL guidelines and the Malchau algorithm as there was no evidence in the peer-reviewed literature to support their use. Both implants show a clear delay or a lag and the lack of a steady flow of studies in the peer-reviewed literature following the introduction of the implants.

Our study is not without limitations. The use of the ASR was also evident in North America. Since we are lacking openly available registry data from the USA and Canada, the global trends cannot be directly inferred from our data. Second, individual registries show some variation in the use of implants and hence the severity of the violation of the introduction process varies between countries.

To conclude, the introduction of the ASR hip replacement violated the fundamental principles of adoption by an almost complete lack of studies in the peer-reviewed literature following its introduction. The results obtained with hip simulators, the claims of similarity to or equivalence with other implants and theoretical advantages failed catastrophically to substitute for the most fundamental foundation of any innovation: the evidence in the literature. We should learn lessons from these recent mistakes made with hip replacements on a wider scale. The adoption and use of any new innovation should follow strict guidelines and algorithms even if the theoretical basis or the results of preclinical studies are excellent.

Supplementary data

Supplementary files 1–5 are available in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1353794

AR collected the data, analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. LL collected the data and commented on the draft. OL collected the data and commented on the draft. KM commented on the draft. AE collected the data and commented on the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

AE has received a grant and a lecture fee from Depuy. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Acta thanks Arild Aamodt and Marc Nieuwenhuijse for help with peer review of this study.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ardaugh B M, Graves S E, Redberg R F.. The 510(k) ancestry of a metal-on-metal hip implant. N Engl J Med 2013; 368 (2): 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkun J S, Aronson J K, Feldman L S, Maddern G J, Strasberg S M, Balliol Collaboration. Evaluation and stages of surgical innovations. Lancet 2009; 374 (9695): 1089–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. Out of joint: The story of the ASR. BMJ 2011; 342: d2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. Faulty hip implant shows up failings of EU regulation. BMJ 2012; 345: e7163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day C S, Park D J, Rozenshteyn F S, Owusu-Sarpong N, Gonzalez A.. Analysis of FDA-approved orthopaedic devices and their recalls. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016; 98 (6): 517–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes B. Can it work? Does it work? Is it worth it? The testing of healthcare interventions is evolving. BMJ 1999; 319 (7211): 652–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons Science and Technology Committee Regulation of medical implants in the EU and UK. Fifth report of session 2012-13. [Google Scholar]

- Langton D J, Jameson S S, Joyce T J, Hallab N J, Natu S, Nargol A V.. Early failure of metal-on-metal bearings in hip resurfacing and large-diameter total hip replacement: A consequence of excess wear. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92 (1): 38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchau H. Introducing new technology: A stepwise algorithm. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000; 25 (3): 285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malchau H, Bragdon C R, Muratoglu O K.. The stepwise introduction of innovation into orthopedic surgery: The next level of dilemmas. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (6): 825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthies A K, Racasan R, Bills P, Blunt L, Cro S, Panagiotidou A, Blunn G, Skinner J, Hart A J.. Material loss at the taper junction of retrieved large head metal-on-metal total hip replacements. J Orthop Res 2013; 31 (11): 1677–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthies A K, Henckel J, Cro S, Suarez A, Noble P C, Skinner J, Hart A J.. Predicting wear and blood metal ion levels in metal-on-metal hip resurfacing. J Orthop Res 2014; 32 (1): 167–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloch P, Altman D G, Campbell W B, Flum D R, Glasziou P, Marshall J C, Nicholl J, Balliol Collaboration. No surgical innovation without evaluation: The IDEAL recommendations. Lancet 2009; 374 (9695): 1105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency Medical device alert. Metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements: Birmingham hip™ resurfacing (BHR) system (Smith & Nephew orthopaedics). June 25, 2015; MDA/2015/024. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuijse M J, Nelissen R G, Schoones J W, Sedrakyan A.. Appraisal of evidence base for introduction of new implants in hip and knee replacement: A systematic review of five widely used device technologies. BMJ 2014; 349: g5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers E M. Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Royal College of Surgeons of England An investigation of the performance of the 3M™ capital™ hip system. Totton, UK: Hobbs the Printers, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Siebel T, Maubach S, Morlock MM.. Lessons learned from early clinical experience and results of 300 ASR hip resurfacing implantations. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2006; 220 (2): 345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underwood R J, Zografos A, Sayles R S, Hart A, Cann P.. Edge loading in metal-on-metal hips: Low clearance is a new risk factor. Proc Inst Mech Eng H 2012; 226 (3): 217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2005. 510(k) premarket notification: DEPUY ASR MODULAR ACETABULAR CUP SYSTEM. K040627. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2006a. Premarket approval (PMA): BIRMINGHAM HIP RESURFACING (BHR) SYSTEM. P040033. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2006b. Summary of safety and effectiveness data: The birmingham hip resurfacing. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2007. Summary of safety and effectiveness data: DEPUY ASR 300 ACETABULAR CUP SYSTEM. K073413 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2008. 510(k) premarket notification: DEPUY ASR XL MODULAR ACETABULAR CUP SYSTEM. K080991. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2009. Premarket approval (PMA): CONSERVE PLUS TOTAL RESURFACING HIP SYSTEM. P030042. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C B. Adoption of new surgical technology. BMJ 2006; 332 (7533): 112–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.