Abstract

Background and purpose

The additional effects of a continuous adductor canal block (ACB) compared with a single-dose local infiltration anesthesia (LIA) after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has not been widely researched. Both methods have good effect individually. We hypothesized that a continuous ACB added to a single-dose LIA would lower pain scores while ambulating on postoperative day 1 (POD1) and postoperative day 2 (POD2).

Patients and methods

69 participants were included in this prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The TKA was performed under spinal analgesia and every participant was given single-dose LIA intraoperatively. Patients were then randomized into 2 groups, treatment group receiving 0.2% ropivacaine and control group receiving normal saline. First a 20 mL bolus was given into the adductor canal and 4 hours later a continuous flow at 6 mL/h was initiated for 2 postoperative days through a catheter placed in the adductor canal.

Results

Worst pain score during movement of the operated knee on POD1 and POD2 was similar between the groups. No other ambulation tests done on POD1 and POD2 showed any statistically significant difference. Morphine consumption on the day of surgery, POD1 and POD2 was similar between the groups.

Interpretation

The results indicate no benefit of continuous infusion ACB added to a single-dose LIA compared with LIA alone on pain while ambulating on POD1 and POD2. Furthermore, the ACB showed no superiority in ambulation ability on the 2 postoperative days.

One of the best predictors for a good outcome after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is early knee mobilization, which can be difficult to acquire if the patient is in pain (Mauerhan et al. 1998, Bong and Di Cesare 2004, Scuderi 2005, Gandhi et al. 2006). Postoperative pain after TKA is moderate to severe (Andersen et al. 2009, Wylde et al. 2011), which delays ambulation (Wu and Richman 2004) and prolongs hospital stay (Essving et al. 2009, Husted et al. 2011). A multimodal analgesia regimen seems to be the most effective way of treating postoperative pain after TKA (Vendittoli et al. 2006, Amantullah 2015) which may include pain medications, local infiltration anesthesia (LIA) and peripheral nerve blocks (PNB). LIA gives good pain control without affecting muscle strength (Kerr and Kohan 2008, Essving et al. 2010) and has been shown to give similar pain scores and shorter lengths of stay when compared with PNB (Spangehl et al. 2015).

After TKA the quadriceps muscle plays a key role for ambulation. Several factors affect its strength, such as PNBs, pain and surgical trauma (Greene and Schurman 2008). PNBs have proved their worth in postoperative pain management after TKA (Amantullah 2015) but one of their biggest disadvantages is reduced muscle strength. Femoral nerve block (FNB) gives good pain relief after TKA (Paul et al. 2010) but affects the quadriceps muscle strength (Jaeger et al. 2013) and may increase the risk of falls (Ilfeld et al. 2010, Johnson et al. 2013). Compared with FNB, adductor canal block (ACB) seems to preserve the quadriceps muscle strength better yet giving similar analgesic effect (Jaeger et al. 2013, Kim et al. 2014, Mudumbai et al. 2014, Wiesmann et al. 2016). For those reasons, ACB has been tried as an alternative to FNB.

The saphenous nerve courses the adductor canal in the medial part of the thigh. A recent study showed that the nerve to vastus medialis (NVM) courses the canal more often than previously thought and most likely plays a major role in the sensory innervation of the knee (Burckett-St Laurant et al. 2016).

Placebo-controlled studies on ACB after TKA have shown promising results regarding pain relief, especially on the day of surgery, and have also been shown to improve patient ambulation (Jaeger et al. 2012, Jenstrup et al. 2012). ACB is a relatively safe procedure (Henningsen et al. 2013) and can lead to lower morphine consumption compared with placebo (Jenstrup et al. 2012, Hanson et al. 2014).

As described above, LIA and ACB seem to work well separately after TKA in randomized controlled trials (RCT) and many of the published studies on ACB have focused on the effects of the block on the day of surgery (Jaeger et al. 2012, Jenstrup et al. 2012, Jaeger et al. 2013). We found only 1 study where ACB was added to a single-dose LIA, where no other blocks were used. The primary end point of that study was worst pain during movement on POD0 (Andersen et al. 2013). We wanted to focus on the analgesic effects of the block on pain and ambulation abilities on POD1 and POD2 by using validated physiotherapy tests. Therefore, this prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial compared the effects of a continuous infusion ACB added to an intraoperative single-dose LIA after TKA. We hypothesized that in addition to LIA, a continuous infusion ACB would lower pain scores while ambulating on POD1 (primary endpoint), enhance ambulation ability, improve pain relief at rest, decrease opioid consumption and shorten the hospital stay (secondary endpoints).

Patients and methods

This prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted at the Akureyri Hospital from October 2015 through May 2016. Eligible participants, screened for inclusion, were patients scheduled for primary unilateral cemented TKA under spinal anesthesia, aged 50–90 years, with ASA physical status I–III. Exclusion criteria were daily intake of opioids (≥ 20 mg/day of oral morphine equivalent for >12 weeks), inability to cooperate, peripheral neuropathy, allergy to any of the study medications and renal insufficiency (creatinine levels >100 μmol/L and >110 μmol/L for women and men respectively).

Randomization and blinding

Randomization was done by a secretary using a computer-generated randomization list (Research randomizer, www.randomizer.org) in a 1:1 ratio with 20 numbers in each block. Every participant received a consecutive study number from 1 to 69 and received the treatment assigned according to the randomization list. The list was stored and only 2 nurses, who prepared the study medications, had access to it. They had no interactions with the patients. All other clinical personnel, participants and outcome assessors were blinded to the intervention. The randomization key was first broken when all enrolled patients had completed the study. After discharge, the participant’s personal information was eliminated from the study number and was therefore not traceable back to the patient.

Interventions

Premedication consisted of 1.5 g acetaminophen and 10–20 mg oxycodone, according to the participant’s weight. Prophylactic medication (ondansetron 4 mg i.v., dexamethasone 8 mg i.v. and haloperidol 1 mg i.v.) for postoperative nausea was given if the patient had a prior history of postoperative nausea.

Spinal anesthesia was induced with bupivacaine 5 mg/mL according to patients’ BMI (BMI <20 = 2.8 mL, BMI 20–35 = 3.2 mL, BMI >35 = 3.4 mL). This was administered at the L2–L3 or L3–L4 vertebral interspaces along with 15 μg of fentanyl. Propofol sedation during surgery was given if required.

Surgical technique and prosthesis selection were left to each of the 4 individual surgeons and all procedures were done in a bloodless field using a femoral tourniquet. 102 mL of LIA was distributed to the posterior capsule, the medial and lateral retinaculum and the subcutaneous tissue according to the method of Guild et al. (2015). The LIA consisted of 200 mg ropivacaine, 30 mg ketorolac and 0.5 mg adrenaline.

According to the randomization list a total amount of 500 mL of study medication, either 0.2% ropivacaine or normal saline, was prepared by either of the 2 un-blinded nurses immediately postoperatively. 480 mL were divided equally into 2 boxes and 20 mL put in a syringe.

The ACB, with placement of a perineural catheter, was performed in the post-anesthesia care unit before the spinal anesthesia had worn off. All the catheters were placed in a sterile fashion by 1 of the 5 attending anesthesiologists. Under ultrasound guidance at mid-thigh level the adductor canal was identified and an 18-gauge Tuohy needle was inserted into the canal. A 20 mL bolus of the study drug was then given. The decision on the bolus volume was based on the amount needed to fill the canal without risking a retrograde flow to the femoral triangle (Lund et al. 2011, Andersen et al. 2015). A 22-gauge epidural catheter was then placed through the Tuohy needle and threaded 5 cm into the canal. The position was confirmed with an injection of 2–3 mL of normal saline. 4 hours after the initial bolus, a continuous infusion of the study drug was initiated at 6 mL/h for 48 hours, calculated to be within the toxic effects of the ropivacaine when taking into account the ropivacaine in LIA and in the initial bolus (Kuthiala and Chaudhary 2011). The catheter was removed on postoperative day 2 (POD2) after the morning physiotherapy (PT) session.

Unless contraindicated, all patients received a standardized analgesic regimen postoperatively consisting of oral acetaminophen 1 g x 4, oral oxycodone 10–20 mg (according to BMI) x 2 and intravenous parecoxib 40 mg x 1. If needed, patients were given additional oral or intravenous pain medication (fast-release oxycodone, ketobemidon, morphine or codeine).

outcome measures

Preoperatively we collected demographic data and registered if patients had a prior TKA of the other knee. We assessed maximum knee flexion, straight leg raise (SLR) and estimated the quadriceps muscle strength of the affected knee (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and preoperative data

| Treatment (n = 35) | Control (n = 34) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age a | 71 (60–87) | 68 (55–85) |

| Sex (male/female) | 17/18 | 16/18 |

| BMI | 31 (22–56) | 31 (23–45) |

| ASA score I/II/III | 2/28/5 | 5/28/1 |

| Preoperative knee flexion | 110 (89–123) | 110 (89–125) |

| Preoperative quadriceps strength | 5 (1–5) | 5 (3–5) |

| Preoperative nausea I/II/III/IV | 1/0/0/0 | 0/0/0/0 |

| Preoperative straight leg raise yes/no | 33/1 | 34/0 |

Data are counts, median (range) or a mean (range)

Primary end point

The primary end point was peak pain level in the operated knee during morning PT session on POD1. Patients were instructed to record their pain, at the time of the assessment, on the numerical rating scale (NRS-11) (Hjermstad et al. 2011), where 0 indicates no pain and 10 indicates worst possible pain.

Secondary end points

In the same way as the primary end point the peak pain level in the operated knee was recorded on POD2. Pain at rest was measured on the NRS-11 scale immediately before the morning PT session on POD1 and POD2. Morphine consumption and additional pain medication was recorded and calculated into Oral Morphine Equivalents (OMEQ) (Svendsen et al. 2011). Time from the end of surgery until first additional pain medication was given was recorded. We documented the day participants were able to climb stairs and when they fulfilled the following criteria for discharge: (a) able to walk with crutches, (b) sufficient oral analgesia, (c) knee flexion ≥70°, (d) ability to climb stairs and (e) no acute medical problems present (if patients failed to meet the criteria before discharge their data were treated as missing). The actual length of stay was also recorded.

All the ambulation ability assessments, apart from the timed up and go (TUG) test (Yeung et al. 2008), were done in the morning of both POD1 and POD2 by 1 of the 4 physiotherapists in the department. These were the degree of active knee flexion, quadriceps muscle strength, SLR and the measurements on the 10-point mobility scale (Jaeger et al. 2013). The TUG test was performed in the morning of POD2. It measures the time it takes the patient to stand up from a chair, walk 3 meters, and return to a sitting position in the chair. The 10-point mobility scale evaluates whether the subject can achieve 5 predefined goals of ambulation with or without help of the physiotherapist. Quadriceps muscle strength was assessed by the ability of the patient to hold the affected limb up with the knee extended against resistance of the examiner (using manual muscle testing (MMT) with 0 = no contraction, 1 = flicker of contraction, 2 = active movement with gravity eliminated, 3 = active movement against gravity but not resistance, 4 = active movement against gravity and some resistance and 5 = normal strength). Finally, the SLR was successful if the participant could hold the lower limb 10 cm from the bed with fully extended knee for 10 seconds.

If there was a sign of irritation, allergy or infection at the catheter site the intervention was stopped and the patient was excluded from further participation.

Statistics

We used G*Power 3 for our power analysis (Faul et al. 2007). 27 participants were required in each group to demonstrate a significant difference of 1 (1.1 SD) on the NRS-11 scale for the primary outcome with a probability of a 2-tailed type I error of 0.05 and a power of 90%. 15 additional subjects were recruited into the study to prevent loss of power due to early withdrawal and to compensate for uncertainty regarding our estimated SD.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS® version 20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). We used the Shapiro–Wilk test to assess normality. Normally distributed variables were compared using Student’s t-test. Pearson’s chi-square test was used for categorical variables but if the minimum expected data count was <5 we used Fisher’s exact test. For the not normally distributed data, we used the Mann–Whitney U-test.

Though the NRS pain-score is commonly thought of as an ordinal scale we decided to follow Dexter and Chestnut (1995) and treat the peak NRS pain score at the PT sessions as normally distributed data. We also ran a Shapiro–Wilk test on the variables, which further confirmed that they were normally distributed. Pain at rest did not follow these rules of normality and is therefore treated as other non-normally distributed data.

All p-values were calculated 2- tailed, and a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics, registration, funding and conflicts of interest

Approval was obtained from the local Regional Ethics Committee of Akureyri Hospital and the Icelandic Data Protection Authority (25.08 2015 nr: 3/2015). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was registered at ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN68176033). The study received funding from Akureyri Hospital Scientific fund (Vísindasjóður Sjúkrahússins á Akureyri) and Akureyri Medical Staff Scientific Fund (Vísindasjóður Læknaráðs, Sjúkrahússins á Akureyri). No competing interest declared.

Results

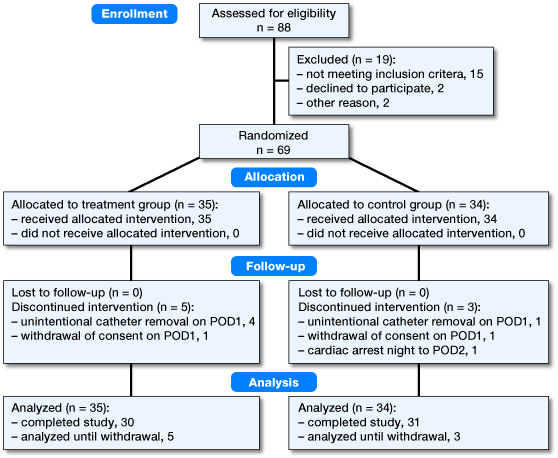

88 patients were approached for participation from October 2015 to May 2016. 69 were included and randomly assigned to treatment (n = 35) or control group (n = 34) (Figure 1). Preoperative measurements and demographic data were similar between the groups (Table 1).

Flow chart of the study.

Peak pain score during PT session on POD1 (primary end point) showed no significant difference between the 2 groups (p = 0.3). For the same measurement on POD2 we found no significant difference (p = 0.9).

The ambulation-ability tests were similar on POD1 and POD2 (Table 2). On POD2 we found significant difference (p = 0.04) on the 10-point mobility scale in favor of the control group. There was 1 participant in the treatment group who showed extremely poor results and when excluded the difference was no longer significant (p = 0.07). The number of individuals reaching discharge criteria on POD2 and the actual length of stay was similar between the groups. The treatment group showed significantly lower pain scores at rest in the morning of POD1 (p = 0.04) but not on POD2 (p = 0.4). Grouping the patients’ pain scores into moderate pain (NRS 3–6) versus strong pain (NRS >7) did not alter our findings. Total morphine consumption and time to first additional pain medication given were similar between the groups (Table 3).

Table 2.

Ambulation abilities

| Treatment | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| POD1: | n = 35 | Pn =34 | |

| POD2: | n = 30 | Pn =31 | p-value |

| Quadriceps strength POD1 | 4 (1–5) | 4 (2–5) | 0.9 |

| Quadriceps strength POD2 | 5 (1–5) | 5 (1–5) | 0.9 |

| Active knee flexion POD1 | 83 (50–100) | 80 (45–100) | 0.8 |

| Active knee flexion POD2 | 90 (30–110) | 90 (65–105) | 0.4 |

| Straight leg raise POD1a | 29/3 | 33/1 | 0.4 |

| Straight leg raise POD2a | 28/1 | 30/1 | 1.0 |

| Climbing stairs POD1a | 5/27 | 1/33 | 0.1 |

| Climbing stairs POD2a | 26/4 | 24/7 | 0.5 |

| TUG test (seconds) POD2 | 24 (0–59) | 25 (0–58) | 0.4 |

| Ready for discharge on POD2a | 26/2 | 25/5 | 0.4 |

| 10-point mobility scale POD1 | 10 (3–10) | 10 (5–10) | 0.6 |

| 10-point mobility scale POD2 | 10 (1–10) | 10 (10–10) | 0.04 |

Data are counts or median (range)

yes/no

Table 3.

Pain scores and morphine consumption

| Treatment | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| POD1: | n = 35 | Pn =34 | |

| POD2: | n = 30 | Pn =31 | p-value |

| NRS during PT session POD1 a | 6 (1–9) | 6 (1–10) | 0.3 |

| NRS during PT session POD2 a | 5 (0–10) | 5 (2–10) | 0.9 |

| NRS at rest POD1 | 1 (0–6) | 3 (0–5) | 0.04 |

| NRS at rest POD2 | 1 (0–6) | 2 (0–5) | 0.4 |

| NRS >3/< 3 at rest POD1 | 4/28 | 8/26 | 0.3 |

| NRS >3/< 3 at rest POD2 | 2/28 | 4/27 | 0.4 |

| Time to additional pain medication (hours) | 7.5 (0.5–47) | 8.0 (0.5–47) | 0.9 |

| OMEQ total POD0 | 38 (15–100) | 53 (15–96) | 0.4 |

| OMEQ total POD1 | 45 (8–130) | 53 (30–145) | 0.3 |

| OMEQ total POD2 | 41 (8–85) | 45 (15–175) | 0.3 |

Data are counts, median (range) or a mean (range)

NRS = Numeric rating scale (for assessment of pain intensity)

PT = Physiotherapy

OMEQ = Oral morphine equivalents

Leakage from the injection site of the catheter developed in 8 participants, 4 in the control group and 4 in the treatment group. No evidence of a visible infection at any catheter site was found during routine follow-up and no falls were recorded in either group.

21 patients who had an earlier TKA done on the other knee were equally distributed between the 2 groups. They were significantly older (p = 0.03) but were similar in other measurements.

Discussion

The aim of this trial was to evaluate the adjunctive effect of a continuous ACB added to a single-dose LIA on pain and ambulation after TKA. Our primary endpoint, pain while ambulating on POD1, was not statistically significantly different between the two groups.

Our results contribute to the decision on whether a continuous ACB should be added to a single-dose LIA after TKA to help with ambulation after the day of surgery. The ACB did not aid in performing the TUG test on POD2 nor did the treatment group show any superiority in other ambulation testing on either POD1 or POD2. These results are comparable to a randomized placebo-controlled trial conducted by Andersen et al. (2013) who observed no difference in pain during movement on POD1 and POD2 in subjects after TKA with continuous ACB added to LIA. In that study no validated physiotherapy testing was used to compare the groups and boluses were used for the ACB instead of infusion.

The effect of ACB on pain and mobilization after TKA has previously been shown to have good effects on POD0 (Jaeger et al. 2012, Jenstrup et al. 2012). The reason why we did not see the same effect of the continuous infusion on POD1 and POD2 is unclear. Andersen et al. (2013) did an ultrasound of the spread of the injectate during the last bolus of ACB on POD2 which showed that 5 out of 8 catheters were displaced out of the canal. Another reason could be that a continuous flow of 6 mL/h is not enough to affect the nerves in the canal.

There are case reports (Chen et al. 2014, Neal et al. 2016) showing that ACB can affect the muscle strength of the quadriceps muscle, which can lead to lower ambulation abilities, but this seems to be rare. Other studies have shown generally better quadriceps functions after TKA in patients who are given ACB compared with placebo (Jaeger et al. 2013, Hanson et al. 2014). We therefore doubt that weakness of the quadriceps muscle is the reason why we found no difference between the 2 groups in ambulation abilities.

Our treatment group showed lower pain scores at rest in the morning of POD1. This finding is not supported in other studies on continuous ACB to placebo (Jenstrup et al. 2012) or to LIA alone (Andersen et al. 2013). Due to multiple tests there is a risk of a type I error. Hence, we do not want to emphasize the single significant result found and must consider it a coincidence. However, as previously mentioned ACB has showed promising effects on POD0 after TKA. The single-shot bolus given after the surgery could be having some residual effects in the morning of POD1 when it comes to pain at rest. If this finding is not a coincidence we doubt its clinical relevance based on the fact that we did not see it resulting in better ambulation abilities or lower morphine consumption on POD1 or POD2.

There are several limitations to this study. To be within the time frame of the study and to fulfill the requirements of the power analysis we had to accept a few deficiencies. 4 orthopedic surgeons performed the operations, though all are experienced with LIA. 5 anesthesiologists performed the ACB, all experienced with ultrasound-guided PNBs and 4 physiotherapists did the ambulation-ability tests. The results therefore reflect the real-life setting, which may weaken the internal validity but on the other hand strengthen the external validity of the trial. We did not use patient-controlled anesthesia, which might have given us more accurate results on the need for additional pain medication. We did not check the success rate of the block, mainly to keep all the staff and the study participants blinded to the treatment group. In that way, we cannot know for sure that the blocks given were all functioning correctly but research has shown about 95% success rates of the adductor canal block (Saranteas et al. 2011, Jenstrup et al. 2012). The disadvantage of giving a continuous-flow ACB rather than boluses is that the patients need to carry a pump, which might affect their ambulation abilities, but should not lead to any bias. The strengths of our trial include its randomized design, the successful blinding process and its consistent approach in standardizing the pre- and postoperative medication. It also was adequately powered for the primary end point.

In conclusion, our results indicate no benefit of continuous-infusion ACB added to a single-dose LIA compared with LIA alone on pain while ambulating on POD1 and POD2. Furthermore, the block showed no superiority in ambulation abilities on these 2 postoperative days. Further research is needed to address the adjunctive effects the block provides to LIA on the day of surgery with primary focus on the ambulation.

SG and JLF contributed substantially to planning and designing the study as well as interpreting the results. SG did the patient recruitment, data collection, statistical testing, statistical and data analysis and prepared the manuscript. JLF helped with data and statistical analysis and revised the manuscript

The authors thank the staff at the anesthesia and orthopedic departments of Akureyri Hospital. We thank Þorlákur Axel Jónsson for his guidance with the statistical part of the work.

Acta thanks Henrik Husted and Johan Rader for help with peer review of this study.

References

- Amantullah D F. Perioperative management in total knee arthroplasty. Current Orthopaedic Practice 2015; 26 (3): 217–23. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen L O, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Husted H, Otte K S, Kehlet H.. Subacute pain and function after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty. Anaesthesia 2009; 64 (5): 508–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen H L, Gyrn J, Moller L, Christensen B, Zaric D.. Continuous saphenous nerve block as supplement to single-dose local infiltration analgesia for postoperative pain management after total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013; 38 (2): 106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen H L, Andersen S L, Tranum-Jensen J.. The spread of injectate during saphenous nerve block at the adductor canal: A cadaver study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015; 59 (2): 238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bong M R, Di Cesare P E.. Stiffness after total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004; 12 (3): 164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckett-St Laurant D, Peng P, Giron Arango L, Niazi A U, Chan V W, Agur A, Perlas A.. The nerves of the adductor canal and the innervation of the knee: An anatomic study. Regional Anesth Pain Med 2016; 41 (3): 321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lesser J B, Hadzic A, Reiss W, Resta-Flarer F.. Adductor canal block can result in motor block of the quadriceps muscle. Regional Anesth Pain Med 2014; 39 (2): 170–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dexter F, Chestnut D H.. Analysis of statistical tests to compare visual analog scale measurements among groups. Anesthesiology 1995; 82 (4): 896–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essving P, Axelsson K, Kjellberg J, Wallgren O, Gupta A, Lundin A.. Reduced hospital stay, morphine consumption, and pain intensity with local infiltration analgesia after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2009; 80 (2): 213–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essving P, Axelsson K, Kjellberg J, Wallgren O, Gupta A, Lundin A.. Reduced morphine consumption and pain intensity with local infiltration analgesia (LIA) following total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2010; 81 (3): 354–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A G, Buchner A.. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007; 39(2): 175–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi R, de Beer J, Leone J, Petruccelli D, Winemaker M, Adili A.. Predictive risk factors for stiff knees in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2006; 21 (1): 46–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene K A, Schurman J R 2nd. Quadriceps muscle function in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23 (7 Suppl): 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guild G N 3rd, Galindo R P, Marino J, Cushner F D, Scuderi G R.. Periarticular regional analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: A review of the neuroanatomy and injection technique. Orthop Clin North Am 2015; 46 (1): 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson N A, Allen C J, Hostetter L S, Nagy R, Derby R E, Slee AE, Arslan A, Auyong D B.. Continuous ultrasound-guided adductor canal block for total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blind trial. Anesth Analg 2014; 118 (6): 1370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henningsen M H, Jaeger P, Hilsted K L, Dahl J B.. Prevalence of saphenous nerve injury after adductor-canal-blockade in patients receiving total knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2013; 57 (1): 112–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjermstad M J, Fayers P M, Haugen D F, Caraceni A, Hanks G W, Loge J H, Fainsinger R, Aass N, Kaasa S.. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: A systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011; 41 (6): 1073–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted H, Lunn T H, Troelsen A, Gaarn-Larsen L, Kristensen B B, Kehlet H.. Why still in hospital after fast-track hip and knee arthroplasty? Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (6): 679–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilfeld B M, Duke K B, Donohue M C.. The association between lower extremity continuous peripheral nerve blocks and patient falls after knee and hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg 2010; 111 (6): 1552–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger P, Grevstad U, Henningsen M H, Gottschau B, Mathiesen O, Dahl J B.. Effect of adductor-canal-blockade on established, severe post-operative pain after total knee arthroplasty: A randomised study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012; 56 (8): 1013–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger P, Zaric D, Fomsgaard J S, Hilsted K L, Bjerregaard J, Gyrn J, Mathiesen O, Larsen T K, Dahl J B.. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for analgesia after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blind study. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2013; 38 (6): 526–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenstrup M T, Jaeger P, Lund J, Fomsgaard J S, Bache S, Mathiesen O, Larsen T K, Dahl J B.. Effects of adductor-canal-blockade on pain and ambulation after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2012; 56 (3): 357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R L, Kopp S L, Hebl J R, Erwin P J, Mantilla C B.. Falls and major orthopaedic surgery with peripheral nerve blockade: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110 (4): 518–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr D R, Kohan L.. Local infiltration analgesia: A technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: A case study of 325 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79 (2): 174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D H, Lin Y, Goytizolo E A, Kahn R L, Maalouf D B, Manohar A, Patt M L, Goon A K, Lee Y Y, Ma Y, Yadeau J T.. Adductor canal block versus femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty: A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Anesthesiology 2014; 120 (3): 540–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuthiala G, Chaudhary G.. Ropivacaine: A review of its pharmacology and clinical use. Indian J Anaesth 2011; 55 (2): 104–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund J, Jenstrup M T, Jaeger P, Sorensen A M, Dahl J B.. Continuous adductor-canal-blockade for adjuvant post-operative analgesia after major knee surgery: Preliminary results. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2011; 55 (1): 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauerhan D R, Mokris J G, Ly A, Kiebzak G M.. Relationship between length of stay and manipulation rate after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13 (8): 896–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudumbai S C, Kim T E, Howard S K, Workman J J, Giori N, Woolson S, Ganaway T, King R, Mariano E R.. Continuous adductor canal blocks are superior to continuous femoral nerve blocks in promoting early ambulation after TKA. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2014; 472 (5): 1377–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal J M, Salinas F V, Choi D S.. Local Anesthetic-Induced myotoxicity after continuous adductor canal block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016; 41 (6): 723–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul J E, Arya A, Hurlburt L, Cheng J, Thabane L, Tidy A, Murthy Y.. Femoral nerve block improves analgesia outcomes after total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology 2010; 113 (5): 1144–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saranteas T, Anagnostis G, Paraskeuopoulos T, Koulalis D, Kokkalis Z, Nakou M, Anagnostopoulou S, Kostopanagiotou G.. Anatomy and clinical implications of the ultrasound-guided subsartorial saphenous nerve block. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2011; 36 (4): 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scuderi G R. The stiff total knee arthroplasty: Causality and solution. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20 (4 Suppl 2): 23–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangehl M J, Clarke H D, Hentz J G, Misra L, Blocher J L, Seamans D P.. The Chitranjan Ranawat Award: Periarticular injections and femoral & sciatic blocks provide similar pain relief after TKA: A randomized clinical trial. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2015; 473 (1): 45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen K, Borchgrevink P, Fredheim O, Hamunen K, Mellbye A, Dale O.. Choosing the unit of measurement counts: The use of oral morphine equivalents in studies of opioid consumption is a useful addition to defined daily doses. Palliat Med 2011; 25 (7): 725–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vendittoli P A, Makinen P, Drolet P, Lavigne M, Fallaha M, Guertin M C, Varin F.. A multimodal analgesia protocol for total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 (2): 282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesmann T, Piechowiak K, Duderstadt S, Haupt D, Schmitt J, Eschbach D, Feldmann C, Wulf H, Zoremba M, Steinfeldt T.. Continuous adductor canal block versus continuous femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty for mobilisation capability and pain treatment: A randomised and blinded clinical trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2016; 136 (3): 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C L, Richman J M.. Postoperative pain and quality of recovery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2004; 17 (5): 455–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wylde V, Rooker J, Halliday L, Blom A.. Acute postoperative pain at rest after hip and knee arthroplasty: Severity, sensory qualities and impact on sleep. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res: OTSR 2011; 97 (2): 139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung T S, Wessel J, Stratford P W, MacDermid J C.. The timed up and go test for use on an inpatient orthopaedic rehabilitation ward. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2008; 38 (7): 410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]