Abstract

Background and purpose

Clindamycin has not been compared with other antibiotics for prophylaxis in arthroplasty. Since 2009, the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR) has been collecting information on the prophylactic antibiotic regime used at every individual operation. In Sweden, when there is allergy to penicillin, clindamycin has been the recommended alternative. We examined whether there were differences in the rate of revision due to infection depending on which antibiotic was used as systemic prophylaxis.

Patients and methods

Patients who had a total knee arthroplasty (TKA) performed due to osteoarthritis (OA) during the years 2009–2015 were included in the study. Information on which antibiotic was used was available for 80,018 operations (55,530 patients). Survival statistics were used to calculate the rate of revision due to infection until the end of 2015, comparing the group of patients who received cloxacillin with those who received clindamycin as systemic prophylaxis.

Results

Cloxacillin was used in 90% of the cases, clindamycin in 7%, and cephalosporins in 2%. The risk of being revised due to infection was higher when clindamycin was used than when cloxacillin was used (RR =1.5, 95% CI: 1.2–2.0; p = 0.001). There was no significant difference in the revision rate for other causes (p = 0.2).

Interpretation

We advise that patients reporting allergic reaction to penicillin should have their allergic history explored. In the absence of a clear history of type-I allergic reaction (e.g. urticaria, anaphylaxis, or bronchospasm), we suggest the use of a third-generation cephalosporin instead of clindamycin as perioperative prophylaxis when undergoing a TKR. No recommendation can be given regarding patients with type-1 allergy.

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is the most common reason for revision within 2 years after a primary TKA (Graves et al. 2014, Singh et al. 2016). Prophylactic systemic antibiotics are an important part of the bundle of recommended preventive measures, with antibiotics from the beta-lactam group being the first choice due to their efficiency against Staphylococcus aureus (Parvizi et al. 2013, Kapadia et al. 2015). The effect of beta-lactams as prophylactic antibiotics has been proven in randomized controlled trials in total hip arthroplasty (Ericson et al. 1973, Hill et al. 1981, AlBuhairan et al. 2008, Voigt and Mosier 2015), and it is reasonable to anticipate their effectiveness in knee arthroplasty as well. In Sweden, the penicillinase-resistant penicillin cloxacillin has been the first choice of perioperative antibiotic since the 1970s (Ericson et al. 1973, The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 2016), whereas cephalosporins are widely used in other countries (Trampuz and Zimmerli 2006, de Beer et al. 2009, Stuyck et al. 2014, Chandrananth et al. 2016). Since the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics such as cephalosporins contributes to the selection of resistant bacteria, national Swedish guidelines recommend limitation of their use where proper antibiotic alternatives with a narrower spectrum are available (SBU 2010). In geographic areas with high prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin may be added to the prophylaxis (Parvizi et al. 2013, Kapadia et al. 2015).

Between 5% and 10% of hospitalized patients report that they are allergic to penicillin—women more often than men (Solensky 2003, Borch et al. 2006, Macy et al. 2009). On testing for type-I hypersensitivity, however, most of these patients prove negative (Solensky 2003, Mirakian et al. 2015). In the case of beta-lactam allergy, clindamycin is recommended as a prophylactic antibiotic, both in national and international guidelines (Stefánsdóttir et al. 2014, Kapadia et al. 2015), even though the effect of clindamycin as perioperative prophylaxis has not—to our knowledge—been proven, either in randomized studies or in registry studies.

The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (SKAR), which was established in 1975, is the oldest national arthroplasty register and has been shown to have a high degree of completeness and validity (Robertsson et al. 2014). Having focused on a minimal dataset, the SKAR added several variables in 2009, including type of antibiotic prophylaxis, height, weight, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification (ASA), to the report form that is filled out in the operation room. Thus, it has become possible to analyze possible effects of these variables on outcomes.

We investigated whether there was any difference in the rate of revision due to infection, depending on which antibiotic was used as perioperative prophylaxis.

Patients and methods

The study population consisted of 82,752 knees in 56,650 patients who were operated on with a primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) for osteoarthritis (OA) during the years 2009–2015. Those with ASA grade IV or V were excluded (0.2%), as were those who did not have complete reporting regarding antibiotic prophylaxis, body mass index (BMI), and ASA grade (3.1%). This left 80,018 primary TKA operations performed at 79 orthopedic departments on 55,350 patients. The mean age at primary operation was 69 (22–101) years and 57% were women. The patients were divided into 4 groups depending on their BMI: < 25, 25–29.9, 30–39.9, and >40.

On the form that is filled out in the operation room for every patient, the following information regarding antibiotic prophylaxis is provided: the type, the dose, the exact timing of the first dose, how many doses are planned, and for how many days.

The primary outcome variable was revision due to infection, with revision being defined as a second surgery in which a component is exchanged, removed, or added (Robertsson et al. 2014). The diagnosis of infection was made by the treating doctors. Reporting a revision to the SKAR however includes providing the registry with copies of medical records, and thereby the possibility of re-evaluating the cause of revision. In an earlier study, high accordance was found between reported infection and the widely used Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) criteria for PJI (Holmberg et al. 2015, Parvizi et al. 2011).

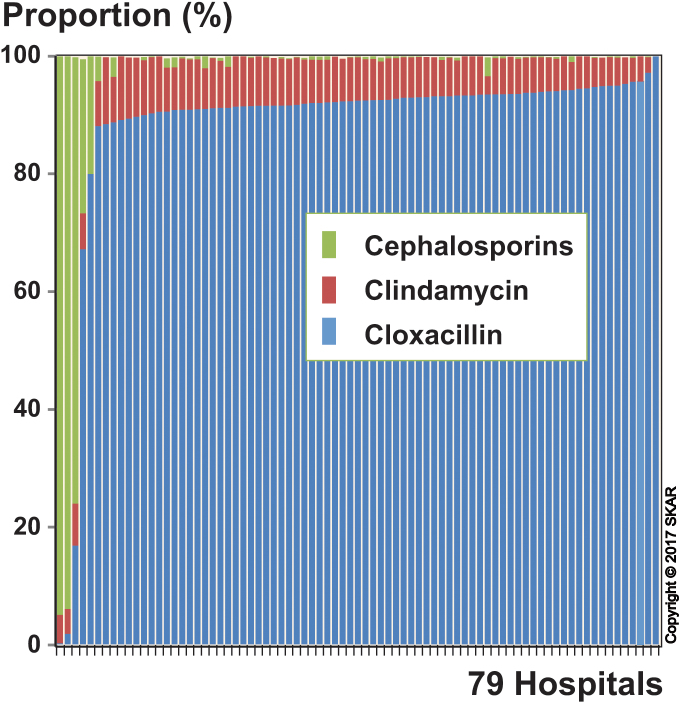

In 99.9% of the operations, the perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis consisted of cloxacillin (90.3%), clindamycin (7.2%), or cephalosporins (2.4%). The cephalosporins used were the second-generation cephalosporin cefuroxime (90%) and the third-generation cefotaxime (10%). Vancomycin was used in only 0.04% of the operations. Cloxacillin was used at most hospitals, whereas 83% of the cephalosporin use was at 4 departments (Figure 1). We decided not to compare cloxacillin with cephalosporins due to the low number of departments using cephalosporins, which might lead to bias due to unknown confounding co-variables. The use of clindamycin was relatively equally spread among the hospitals (Figure 1). Both knees in bilaterally operated patients were included in the study, as this has been found not to affect the results (Robertsson and Ranstam 2003). Even so, we performed analyses excluding the first-operated and second-operated knee in turn, and this did not alter the findings.

Figure 1.

For each of the hospitals, the proportion of the total number of arthroplasties in which a particular antibiotic was used. The hospitals have been sorted according to the proportional use of cloxacillin (low to high).

Male sex is a known risk factor for revision due to PJI (Jämsen et al. 2009, Namba et al. 2013). High BMI has also been identified as a risk factor for PJI, although the BMI limits for increasing risk vary between studies (Namba et al. 2005, McElroy et al. 2013, Inacio et al. 2014). Other factors known to affect the complication rate are ASA grade and age (Namba et al. 2013, Belmont et al. 2014). The patients were followed until the end of 2015, giving a follow-up time with respect to revision of up to 7 years.

Statistics

For descriptive statistics, we used means and proportions. The cumulative revision rate curves were calculated using the life table method with 1-month intervals. Cox regression was used to compare the risk in patients receiving cloxacillin and clindamycin, adjusting for differences in age, sex, ASA class, and BMI. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Wilson quadratic equation with Greenwood and Peto effective sample-size estimates (Dorey et al. 1993). The curves were cut off when 40 knees remained at risk. Any p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. The proportional-hazards assumption of the Cox regression model was assessed by visual inspection (log-minus-log plot).

Ethics, funding, and conflict of interests

The data gathering of the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register was approved by the Ethics Board of Lund University (LU 20-02) The study was supported by grants from the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR), from the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, and from Stiftelsen för bistånd åt rörelsehindrade i Skåne. No competing interests declared.

Results

The completeness in the reporting of the antibiotic propylaxis used, ASA class, and BMI improved over the period, from 86% in 2009 to 99% in 2015. Cloxcillin was used as perioperative prophylaxis in 72,223 operations, clindamycin in 5,771, and cephalosporins in 1,938, whereas other antibiotics were used in only 86 cases. Use of clindamycin was more than twice as common in females than in males, and cephalosporins were also more commonly used in women (Table). The prophylaxis was administered within 15–45 minutes before surgery in 83% of the cloxacillin group, 81% of the clindamycin group, and 79% of the cephalosporin group. The length of the planned prophylaxis was ≤24 hours in 98% of the cloxacillin group, in 97% of the clindamycin group, and in 91% of the cephalosporin group. The planned number of cloxacillin doses was most often 2 g × 3 (68%) and 2 g × 4 (27%). For clindamycin, they were 600 mg ×3 (79%) and 600 mg ×2 (13%), and for cephalosporin they were 1.5 g × 4 (48%) and 1.5 g × 3 (41%). In all the groups, antibiotic prophylaxis was started preoperatively in more than 99% of cases. Bone cement was used for fixation in 95% of the operations in both the cloxacillin group and the clindamycin group, and in 99% of them in the cephalosporin group. The cement contained gentamicin in 99.8% of all cases. The mean length of follow-up was 3.3 years in the cloxacillin group and 3.2 years in the clindamycin group.

Type of antibiotic used as perioperative prophylaxis, according to sex. Number and percentage of operations

| Women |

Men |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cloxacillin | 40,238 | 87.7 | 31,994 | 93.7 | 72,232 | 90.3 |

| Clindamycin | 4,356 | 9.5 | 1,415 | 4.1 | 5,771 | 7.2 |

| Cephalosporin | 1,241 | 2.7 | 697 | 2.1 | 1,938 | 2.4 |

| Other | 51 | 0.1 | 35 | 0.1 | 86 | 0.1 |

| Total | 45,886 | 100 | 34,141 | 100 | 80,027 | 100 |

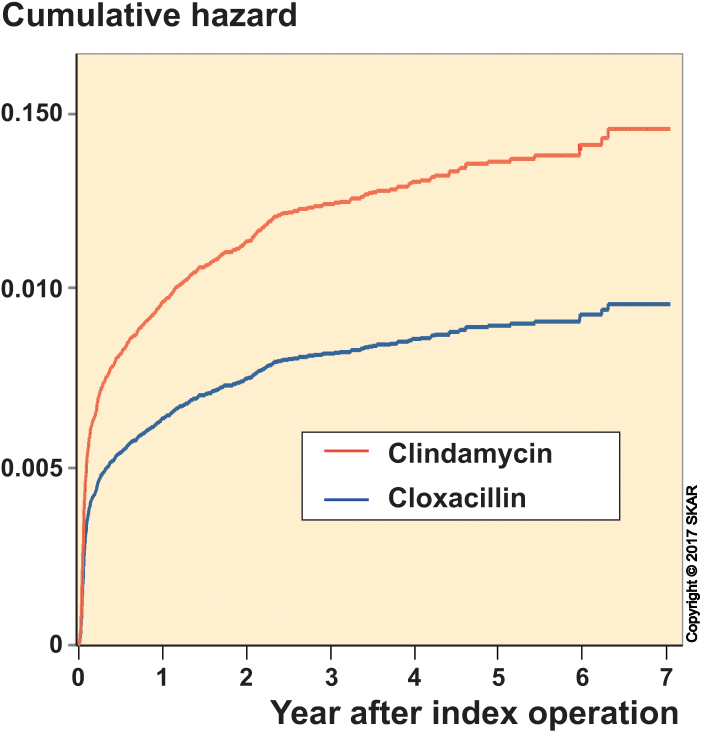

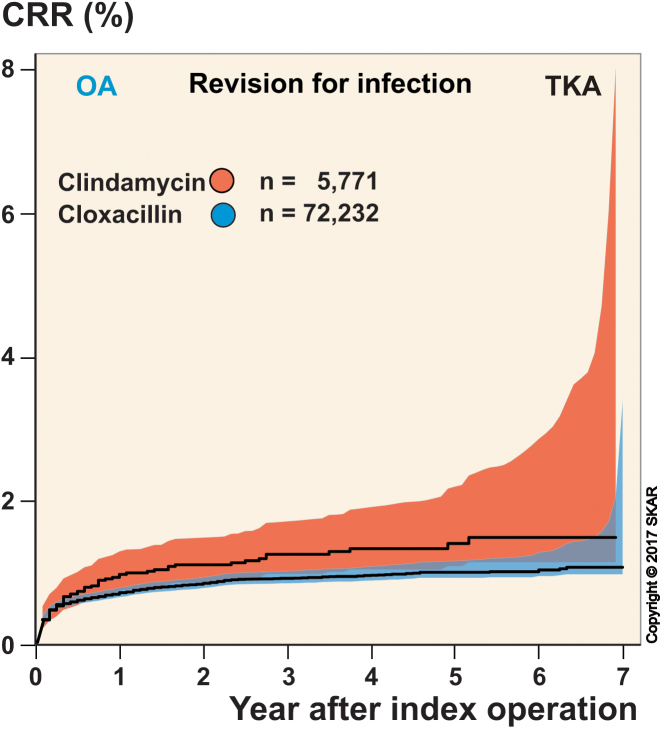

With revision due to infection as an endpoint, there were 723 revisions, of which 59% occurred within the first 3 months and 79% occurred within the first year. Cox regression showed that patients who received clindamycin had a higher risk of revision than those who received cloxacillin, with a risk ratio (RR) of 1.5 (95% CI: 1.2–2.0). The cumulative hazard from the Cox regression is shown in Figure 2 and the unadjusted risk of revision is shown in Figure 3. Men had a higher risk than women, while ASA grade-I patients had lower risk and ASA grade-III patients had higher risk than ASA grade-II patients. Age did not statistically significantly affect the risk of revision for infection, but BMI was a significant factor—showing that patients with BMI 30–39.9 and BMI >40 had higher risk than those with BMI 20–29.9. Patients with BMI <25 did not differ significantly from those with BMI 25–29.9, but had lower risk than those with a BMI of 30 and over. With revision due to causes other than infection as an endpoint, there were 956 revisions—of which only 4% occurred within the first 3 months and 25% occurred within the first year. Cox regression showed that there was no statistically significant difference in risk of revision in the cloxacillin and clindamycin groups (p = 0.2). Unlike when using revision for infection as endpoint, men had lower risk than women, the risk decreased with increasing age, and BMI class had no significant effect on the risk. However, as when using revision for infection as endpoint, the ASA grade-II patients had lower risk than ASA grade-III patients, and although the difference in risk between ASA grade-I and ASA grade-II patients was not statistically significant, the ASA grade-I patients had significantly lower risk than ASA grade-III patients.

Figure 2.

Cumulative hazard of being revised for infection after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and ASA grade.

Figure 3.

Unadjusted cumulative revision rate (CRR).

Discussion

To our knowledge, clindamycin has not previously been compared to drugs with proven prophylactic effect against infection in arthroplasty surgery. The finding that patients who received clindamycin had a 50% higher risk of revision due to infection than patients who received cloxacillin is important, as a considerable number of patients are given clindamycin—in our study, 7%. The randomized clinical trials that evaluated the effect of prophylactic systemic antibiotics were from the 1970s and 1980s (Ericson et al. 1973, AlBuhairan et al. 2008, Voigt and Mosier 2015), and it is unlikely that such studies will be reproduced. Our study shows that registry-based studies are a valid alternative, and can provide information on the present performance of prophylactic antibiotics.

There have been concerns that registries underestimate prosthetic joint infections (Witsø 2015). However, the main strength of our study is that the use of clindamycin was evenly distributed among the orthopedic units performing TKR, minimizing the risk of selection—as both groups would be affected by any under-reporting to the same extent. The same applies regarding the operational environment and regarding some of the factors known to affect the risk of infection, such as diabetes and smoking. A possible limitation of the study is that the registry does not have an exact definition of infection, and relies on the treating doctor’s ability to correctly diagnose infection. However, in an earlier study we found good conformity between reported infection and the MSIS criteria (Holmberg et al. 2015). As the main outcome variable in our study was revision, those infections treated with debridement without exchange of the tibial insert or with suppressive antibiotic therapy would be missed. We have no reason to believe that there could be differences in the choice of implant or type of treatment for infection related to the choice of perioperative antibiotic. It can also be postulated that patients with allergy are more prone to infection. However, we have not found any support for this hypothesis in the literature.

The reasons for the inferior effect of clindamycin compared to cloxacillin are not clear. The fact that clindamycin is a bacteriostatic drug, whereas beta-lactams are bactericidal, may be of importance. In addition, clindamycin is distributed intracellularly to a high degree, giving dilution (from the larger volume of distribution) that is much higher than that for cloxacillin (Ghafourian et al. 2006). The dose of clindamycin used in Sweden was 600 mg, 2 or 3 times. It is possible that a higher dose of 900 mg, as has been recommended (Meehan et al. 2009), might have had better effect. Bacterial resistance might also be a contributing factor, even though the proportion of Staphylococcus aureus strains in Sweden that are resistant to clindamycin is low (the Public Health Agency of Sweden).

We are not aware of any other prophylactic randomized or registry-based studies using clindamycin in orthopedic surgery. Clindamycin has been found to be inferior to cephalosporin as a prophylactic antibiotic in head and neck free tissue transfer (Pool et al. 2016).

A higher proportion of women received clindamycin, probably due to the higher incidence of self-reported allergy to penicillin in women. This is supported by a reported incidence rate of penicillin allergy among women of 11%, which is consistent with the level of clindamycin use in our study (Macy et al. 2009). It is also known that women are prescribed antibiotics more often than men (Mor et al. 2015).

The prevalance of MRSA is very low in Sweden (the Public Health Agency of Sweden), and the main reason for using clindamycin as perioperative prophylaxis is therefore reported allergy to penicillin. Even though between 5% and 10% of hospitalized patients report allergy to penicillin (Borch et al. 2006, Macy et al. 2009), almost all of these have negative results when tested for type-I hypersensitivity (Solensky 2003, Mirakian et al. 2015). Immediate type-I reactions are mediated by IgE and generally occur within 1 hour of a given dose, and symptoms include pruritic rash, urticaria, and anaphylaxis (Mirakian et al. 2015). This type of reaction is very rare, with a reported incidence of 0.015–0.04% (Solensky 2003). Delayed reactions of type II–IV can cause a wide array of manifestations. The T-cell-mediated type-IV reactions mainly cause cutaneous symptoms ranging from a mild rash to severe muco-cutaneous reactions such as Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) (Mirakian et al. 2015, Romano et al. 2016). Cross-reactivity between penicillins and cephalosporins has been reported, and earlier studies have indicated an incidence of 10%. However, the true incidence of cross-reactivity is lower, ranging from 0% to 6% in more recent studies. Furthermore, the incidence is higher for first-generation cephalosporins than for those of the second and third generations (Pichichero and Casey 2007, Park et al. 2010, Ahmed et al. 2012, Terico and Gallagher 2014).

There is no evidence to support the view that vancomycin would perform better than clindamycin. On the contrary, a higher infection rate has been reported when using vancomycin than when using cefazolin or clindamycin (Ponce et al. 2014). In England, teicoplanin is the first choice in cases of penicillin allergy—and is even used frequently in other cases as well, which is probably related to the higher prevalence of MRSA in England than in Scandinavia (Hickson et al. 2015).

For patients who report having penicillin allergy, or have penicillin allergy stated in their medical record, a thorough investigation of the allergic history is recommended. Patients with suspected type-I reactions (that is, urticaria, anaphylaxis, or bronchospasm) should not be given beta-lactam antbiotic without previous allergic testing. Testing, consisting of a combination of serology and skin tests followed by drug provocation, can safely rule out type-I allergy in many patients, and can be recommended where feasible (Solensky 2003, Mirakian et al. 2015). For patients who have experienced severe skin reactions such as SJS and TEN, or other life-threatening reactions, beta-lactams are best avoided altogether. All other patients with self-reported penicillin allergy can, with reasonable safety precautions, be given second- or third-generation cephalosporin, which is in accordance with international guidelines and the proceedings of the international consensus meeting (Bratzler et al. 2013, Parvizi et al. 2013). Even though the effect of cephalosporins has been proven in an RCT on hip arthroplasty (Hill et al. 1981) and not in knee arthroplasty, we have no reason to believe that the effect would differ between these types of operation.

We found no difference in the rate of revision due to causes other than infection depending on which antibiotic was used as prophylaxis. In the frequently cited study from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register, Engesaeter et al. (2003) reported finding a correlation between aseptic revision rate and prophylactic antibiotic treatment, both systemically and in bone cement. Among possible explanations, they postulated that low-grade infections were wrongly diagnosed as aseptic loosening. The operations included in the Norwegian study were performed during the years 1987–2001 and concerned hip arthroplasty. Furthermore, it is possible that orthopedic surgeons today have a higher degree of awareness regarding infection, resulting in fewer undiagnosed infections.

The effect of sex, ASA grade, and BMI on infection rate was as expected, whereas we did not find any correlation between age and infection rate.

It is reasonable to believe that our findings can be extended to hip arthroplasty, but there is a need for a separate study.

We conclude that clindamycin is inferior to cloxacillin as perioperative infection prophylaxis. The number of patients who receive clindamycin could be reduced by thorough analysis of the allergic history, and those without type-I allergy could safely be given a second- or third-generation cephalosporin. However, for those with suspected type-I allergy, the possibilities of hospitals to perform testing vary. As there is no evidence to support the idea that it is better to replace cloxacillin with antibiotic(s) other than clindamycin, we cannot give any clear recommendations regarding testing or treatment of these cases.

The study was conceived by OR, AWD, and AS. OR performed the analyses and wrote the initial draft. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and to revision of the manuscript. All the authors approved the final manuscript.

We thank all our contact surgeons and associated staff at the various hospitals in Sweden for their dedicated registration work over the years.

Acta thanks Geert Walenkamp for help with peer-review of this study.

References

- Ahmed K A, Fox S J, Frigas E, Park M A.. Clinical outcome in the use of cephalosporins in pediatric patients with a history of penicillin allergy. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2012; 158(4): 405–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlBuhairan B, Hind D, Hutchinson A.. Antibiotic prophylaxis for wound infections in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90(7): 915–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beer J, Petruccelli D, Rotstein C, Weening B, Royston K, Winemaker M.. Antibiotic prophylaxis for total joint replacement surgery: results of a survey of Canadian orthopedic surgeons. Can J Surg 2009; 52(6): E229–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmont P J, Goodman G P, Waterman B R, Bader J O, Schoenfeld A J.. Thirty-day postoperative complications and mortality following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96(1): 20–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borch J E, Andersen KE, Bindslev-Jensen C.. The prevalence of suspected and challenge-verified penicillin allergy in a university hospital population. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2006; 98(4): 357–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bratzler D W, Dellinger E P, Olsen K M, Perl T M, Auwaerter P G, Bolon M K, Fish D N, Napolitano L M, Sawyer R G, Slain D, Steinberg J P, Weinstein R A.. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Heal Pharm 2013; 70(3): 195–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrananth J, Rabinovich A, Karahalios A, Guy S, Tran P.. Impact of adherence to local antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines on infection outcome after total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Hosp Infect 2016; 93(4): 423–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorey F, Nasser S, Amstutz H.. The need for confidence intervals in the presentation of orthopaedic data. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993; 75(12): 1844–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engesaeter L B, Lie S A, Espehaug B, Furnes O, Vollset S E, Havelin L I.. Antibiotic prophylaxis in total hip arthroplasty: effects of antibiotic prophylaxis systemically and in bone cement on the revision rate of 22,170 primary hip replacements followed 0-14 years in the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop Scand 2003; 74(6): 644–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson C, Lidgren L, Lindberg L.. Cloxacillin in the prophylaxis of postoperative infections of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1973; 55(4): 808–13, 843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves S, Steiger R De, Lewis P, Williams S, Bergman N, Cunningham J. The Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Arthroplasty Register. Hip and Knee Arthroplasty: Annual Report 2014; 1-235. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen E, Belden K, Silibovsky R, Vogt M, Arnold W, Bicanic G, Bini S, Catani F, Chen J, Ghazavi M, Godefroy KM, Holham P, Hosseinzadeh H, Kim KI, Kirketerp-Møller K, Lidgren L, Lin JH, Lonner JH, Moore CC, Papagelopoulos P, Poultsides L, Randall RL, Roslund B, Saleh K, Salmon JV, Schwarz E, Stuyck J, Dahl AW, Yamada K.. Perioperative antibiotics. J Orthop Res 2014; 32(S1): S31–S59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickson CJ, Metcalfe D, Elgohari S, Oswald T, Masters J P, Rymaszewska M, Reed M R, Sprowson A P.. Prophylactic antibiotics in elective hip and knee arthroplasty: an analysis of organisms reported to cause infections andnational survey of clinical practice. Bone Joint Res 2015; 4(11): 181–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Flamant R, Mazas F, Evrard J.. Prophylactic cefazolin versus placebo in total hip replacement. Report of a multicentre double-blind randomised trial. Lancet 1981; 1(8224): 795–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg A, Thórhallsdóttir V G, Robertsson O, W-Dahl A, Stefánsdóttir A.. 75% success rate after open debridement, exchange of tibial insert, and antibiotics in knee prosthetic joint infections. Acta Orthop 2015; 86(4): 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inacio M C S, Kritz-Silverstein D, Raman R, Macera C A, Nichols J F, Shaffer R A, Fithian D C.. The impact of pre-operative weight loss on incidence of surgical site infection and readmission rates after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29(3): 458–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jämsen E, Huhtala H, Puolakka T, Moilanen T.. Risk factors for infection after knee arthroplasty. A register-based analysis of 43,149 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91(1): 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapadia BH, Berg RA, Daley JA, Fritz J, Bhave A, Mont MA.. Periprosthetic joint infection. Lancet. 2015; 6736(14): 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy E, Schatz M, Lin C, Poon K-Y.. The falling rate of positive penicillin skin tests from 1995 to 2007. Perm J 2009; 13(2): 12–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy M J, Pivec R, Issa K, Harwin S F, Mont M A.. The effects of obesity and morbid obesity on outcomes in TKA. J Knee Surg 2013; 26(2): 83–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehan J, Jamali A A, Nguyen H.. Prophylactic antibiotics in hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91(10): 2480–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirakian R, Leech SC, Krishna M T, Richter A G, Huber P A J, Farooque S, Khan N, Pirmohamed M, Clark A T, Nasser S M. Management of allergy to penicillins and other beta-lactams. Clin Exp Allergy 2015; 45(2): 300–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mor A, Frøslev T, Thomsen R W, Oteri A, Rijnbeek P, Schink T, Garbe E, Pecchioli S, Innocenti F, Bezemer I, Poluzzi E, Sturkenboom M C, Trifirò G, Søgaard M.. Antibiotic use varies substantially among adults: a cross-national study from five European Countries in the ARITMO project. Infection 2015; 43(4): 453–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba R S, Paxton L, C Fithian D, Lou Stone M.. Obesity and perioperative morbidity in total hip and total knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20(7 Suppl 3): 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namba R S, Inacio M C, Paxton E W.. Risk factors associated with deep surgical site infections after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95(9): 775–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park M A, Koch C A, Klemawesch P, Joshi A, Li J T.. Increased adverse drug reactions to cephalosporins in penicillin allergy patients with positive penicillin skin test. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2010; 153(3): 268–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, Bauer TW, Springer BD, Della Valle CJ, Garvin KL, Mont MA, Wongworawat MD, Zalavras CG.. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469(11): 2992–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Gehrke T, Franklin B. Proceedings of the International Consensus Meeting on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichichero M E, Casey J R.. Safe use of selected cephalosporins in penicillin-allergic patients : A meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007; 136(3): 340–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponce B, Raines B T, Reed R D, Vick C, Richman J, Hawn M.. Surgical site infection after arthroplasty: comparative effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96(12): 970–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pool C, Kass J, Spivack J, Nahumi N, Khan M, Babus L, Teng M S, Genden E M, Miles B A.. Increased surgical site infection rates following clindamycin use in head and neck free tissue transfer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016; 154(2): 272–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J.. No bias of ignored bilaterality when analysing the revision risk of knee prostheses: analysis of a population based sample of 44,590 patients with 55,298 knee prostheses from the national Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003; 4: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertsson O, Ranstam J, Sundberg M, W-Dahl A, Lidgren L.. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register: a review. Bone Joint Res 2014; 3(7): 217–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano A, Gaeta F, Arribas Poves M F, Valluzzi R L.. Cross-reactivity among beta-lactams. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2016; 16(3): 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SBU Antibiotikaprofylax vid kirurgiska ingrepp. Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services. Stockholm; 2010. Available from: http://www.sbu.se/200 [Google Scholar]

- Singh J, Politis A, Loucks L, Hedden D R, Bohm E R.. Trends in revision hip and knee arthroplasty observations after implementation of a regional joint replacement registry. Can J Surg 2016; 59(5): 304–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solensky R. Hypersensitivity reactions to beta-lactam antibiotics. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2003; 24(3): 201–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefánsdóttir A, Erichsen Andersson A, Höglund Karlsson I, Staaf A, Stenmark S, Tammelin A. Infektionsförebyggande arbete kan aldrig avslutas. Lakartidningen. 2014. Available from: www.lakartidningen.se/Opinion/Debatt/2014/08/Nationellt-projekt-for-att-halvera-antalet-protesrelaterade-infektioner/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terico A T, Gallagher J C.. Beta-lactam hypersensitivity and cross-reactivity. J Pharm Pract 2014; 27(6): 530–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Public Health Agency of Sweden 2015 Swedres | Svarm: Consumption of antibiotics and occurrence of antibiotic resistance in Sweden [Internet]. 2015. Available from; www.sva.se/globalassets/redesign2011/pdf/om_sva/publikationer/swedres_svarm2015.pdf [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register Annual report 2016. Lund; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Trampuz A, Zimmerli W.. Antimicrobial agents in orthopaedic surgery: Prophylaxis and treatment. Drugs 2006; 66(8):1089–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt J, Mosier M.. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of antibiotics and antiseptics for preventing infection in people receiving primary total hip and knee prostheses. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59(11): 6696–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witsø E. The rate of prosthetic joint infection is underestimated in the arthroplasty registers. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (3): 277–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]