Abstract

Background and purpose

To minimize the risk of hematogenous periprosthetic joint infection (HPJI), international and Dutch guidelines recommended antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures. Unclear definitions and contradictory recommendations in these guidelines have led to unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions. To formulate new guidelines, a joint committee of the Dutch Orthopaedic and Dental Societies conducted a systematic literature review to answer the following question: can antibiotic prophylaxis be recommended for patients (with joint prostheses) undergoing dental procedures in order to prevent dental HPJI?

Methods

The Medline, Embase, and Cochrane databases were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), reviews, and observational studies up to July 2015. Studies were included if they involved patients with joint implants undergoing dental procedures, and either considered HPJI as an outcome measure or described a correlation between HPJI and prophylactic antibiotics. A guideline was formulated using the GRADE method and AGREE II guidelines.

Results

9 studies were included in this systematic review. All were rated “very low quality of evidence”. Additional literature was therefore consulted to address clinical questions that provide further insight into pathophysiology and risk factors. The 9 studies did not provide evidence that use of antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the incidence of dental HPJI, and the additional literature supported the conclusion that antibiotic prophylaxis should be discouraged in dental procedures.

Interpretation

Prophylactic antibiotics in order to prevent dental HPJI should not be prescribed to patients with a normal or an impaired immune system function. Patients are recommended to maintain good oral hygiene and visit the dentist regularly.

Worldwide, the number of patients with artificial joint prostheses has been increasing for decades. Prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) occur in approximately 0.3–2% of the patients, and infection rates continue to rise (Zimmerli and Sendi 2010, Dale et al. 2012). PJI is caused by bacterial contamination perioperatively or via hematogenous routes. Hematogenous PJIs (HPJIs) are responsible for about one-third of the PJI cases and are thought to occur mainly as late PJIs (> 2 years post-implantation), but the proportion of HPJIs in early PJI (< 3 months post-implantation) is in fact unknown (Hamilton and Jamieson 2008, Zimmerli and Sendi 2010). Bacteria causing HPJI originate from distant anatomic sites such as the skin, the urinary tract, and to a lesser extent the oral cavity (10% of all HPJIs) (Ainscow and Denham 1984, Zimmerli and Sendi 2010). The hypothesis that transient bacteremia from the oral cavity can cause HPJIs in humans seems plausible, but it is mainly based on animal experiments and human studies in which bacteremia is used as a surrogate marker for the risk of HPJI (Blomgren 1981, Southwood et al. 1985, Watters et al. 2013).

To reduce the risk of HPJI due to oral bacteremia, several national guidelines recommend antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures. Interestingly, however, the literature is inconsistent with regard to the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing the incidence of HPJI of dental origin (Lockhart et al. 2008, Young et al. 2014). Due to the lack of convincing supporting evidence, and possibly the fear of legal consequences, the AAOS/ADA guideline recommendations have been contradictory and confusing, and have resulted in defensive healthcare practices. European guidelines have often adopted the AAOS/ADA guidelines, but they tend to recommend antibiotic prophylaxis less frequently.

In the Netherlands, the 2010 guidelines advised the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in cases involving dental procedures in “infected” oral pathology and in patients with “reduced immune capacity” (Swierstra et al. 2011). These poorly defined indications were confusing. As a result, physicians formulated their own regional guidelines with varying indications for antibiotics, which has possibly led to unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions (Walenkamp 2013).

The Dutch Orthopaedic and Dental Societies therefore appointed a joint committee to formulate new and better-defined guidelines for the prudent use of antibiotics for prophylaxis. This committee conducted a systematic literature review to answer the following question: can antibiotic prophylaxis be recommended for patients (with joint prostheses) undergoing dental procedures in order to prevent dental HPJI?

Methods

The committee consisted of orthopedic surgeons (GW, JH, and DM), a dental practitioner (TG), an oral maxillofacial surgeon (OMFS) (FR) and an OMFS resident (WR). The committee was supported by a medical literature specialist of the Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists who formulated the systematic literature searches, supported the literature quality assessment by the committee, and ensured that the recommendations were formulated according to the AGREE II guidelines.

A systematic literature review was performed using the electronic Medline, Embase, and Cochrane databases. The search parameters were concentrated on literature published between 1980 and 2015 in English, German, French, or Dutch. Only systematic reviews and original randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for full-text analysis, provided that they reported on patients with joint implants (e.g. knee, hip, shoulder) who were undergoing dental treatment, and either considered HPJI as one of the outcome measures or described a direct correlation between HPJI and antibiotic prophylaxis. The search strategy was followed and the results were analyzed according to criteria that were specified a priori (Guideline Committee 2015). All the committee members individually screened the articles for title and abstract, and, if they were eligible, read the full text. Since this search provided just 1 publication that was eligible, a second, similar search and analysis was performed, this time including observational studies. Finally, additional literature was found through the reference lists of the publications selected. 2 investigators (GW and WR) extracted information from the included trials on: (1) study characteristics (i.e. design, follow-up course) and inclusion and exclusion criteria; (2) overall participant demographics (e.g. prosthesis type, joint age); (3) methods of diagnosing dental HPJI (e.g. questionnaires, microbiological tests) and outcome measures (e.g. incidence of PJI and HPJI, type of dental treatment, use of prophylactic antibiotics). Relative risk reduction in dental HPJI due to antibiotics was the primary outcome measure. The final systematic literature searches were performed up to July 2015.

The GRADE method was used to determine the risk of bias of the studies included. In light of the limited quantitative and qualitative results presented by the systematic review, we formulated several additional questions that might provide further insight into the pathophysiology of dental HPJI, risk factors, and risk procedures (Table 1). These questions were answered using literature from additional searches.

Table 1.

Additional clinical considerations

| 1. | Which bacteria are able to cause HPJI, in what numbers are they required, and can antibiotic prophylaxis influence bacteremia? |

| 2. | Is there an increased risk of HPJI in the first 2 years postoperatively? |

| 3. | Is bleeding during dental treatment an indicator of a higher risk of HPJI? |

| 4. | Are prophylactic antibiotics indicated in patients with an impaired immune status? |

| 5. | What are the risks and benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis for HPJI? |

| 6. | Is antibiotic prophylaxis a cost-effective means of preventing HPJI? |

| 7. | Is dental screening indicated before and/or after prosthesis placement? |

| 8. | Is an antibacterial mouthwash indicated before dental treatment? |

| 9. | What are the international recommendations on antibiotic prophylaxis and dental HPJI? |

To increase the support for the guidelines and reduce possible bias, the draft guidelines were sent to 7 relevant Dutch medical societies. With the help of their comments, a definitive guideline was written and accepted by the Dutch Orthopaedic and Dental Societies in February 2016. After that, more recent studies and reviews were included to ensure the completeness of this article.

Results

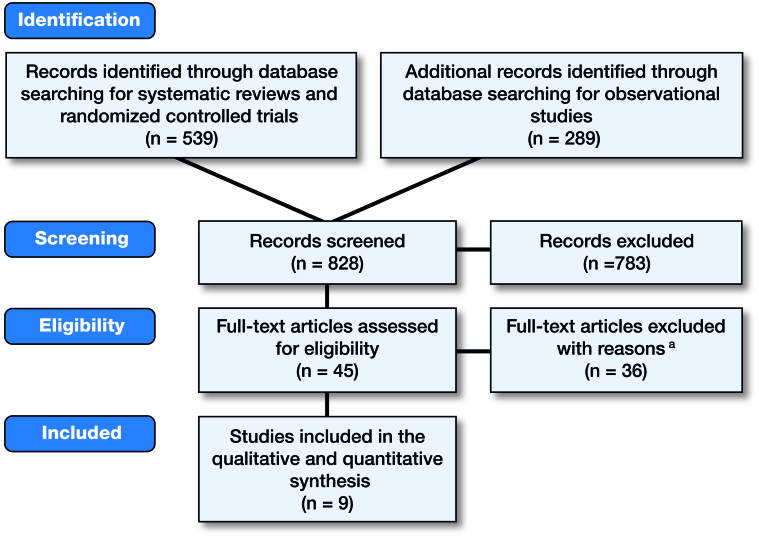

In the systematic literature review, 828 studies were screened regarding title and abstract, of which 45 were selected for critical appraisal of the full text. Following the exclusion of 36 full-text articles for systematic reasons (Table 2, see Supplementary data), 9 eligible studies remained: 6 as a result of the systematic searches and 3 by checking the references of the studies included (Figure). Study characteristics are presented in Table 3. The incidence of PJI varied in these studies between 1.2% and 2.0% and the incidence of HPJI varied between 0.1% and 1.7%. Based on indirect evidence, the incidence of dental HPJI ranged from 0.03% to 0.2%. None of the studies found a significant reduction in dental HPJI associated with antibiotic prophylaxis.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the studies included

| Study reference | Study design | Joint type (no. of patients) | Incidence of DHPJI | Conclusion on effect of prophylactic antibiotics on HPJI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jacobsen and Murray 1980 | Retrospective | Hips (n = 1,885) | 0.05% | The recommended prophylactic antibiotics should be based on drug sensitivity. |

| observational | ||||

| Ainscow and Denham 1984 | Prospective | Hips (n = 885) | No significant influenceof dental treatment on incidence of HPJI | Prophylactic antibiotics would not haveprevented the HPJI cases. |

| observational | Knees (n = 115) | |||

| Waldman et al. 1997 | Retrospective | Knees (n = 3,490) | 0.2% | Indicated before extensive dental treatment in patients with systemic disease that com- promises host defense mechanisms against infection. |

| observational | ||||

| LaPorte et al. 1999 | Retrospective | Hips (n = 2,973) | 0.1% | Indicated before extensive dental treatment in patients with systemic disease that com promises host defense mechanisms against infections. |

| observational | ||||

| Cook et al. 2007 | Retrospective | Knees (n = 3,013) | 0.03% | n.m. |

| observational | ||||

| Uçkay et al. 2009 | Prospective | Hips (n = 4,002) | No significant influence of dental treatment on incidence of HPJI | n.m. |

| observational | Knees (n = 2,099) | |||

| Berbari et al. 2010 | Prospective | Hips (n = 328) | No significant influence of dental treatment on incidence of HPJI | Prophylactic antibiotics do not reduce the risk of DHPJI. |

| case-control | Knees (n = 350) | |||

| Swan et al. 2011 | Retrospective | Knees (n = 1,641) | No significant influence of dental treatment on incidence of HPJI | n.m. |

| case-control | ||||

| Skaar et al. 2011 | Retrospective | Hips (n = 468) | No significant influence of dental treatment on incidence of HPJI | Prophylactic antibiotics do not reduce the risk of DHPJI. |

| case-control | Knees (n = 501) | |||

| Other (n = 31) |

DHPJI: dental treatment-related hematogenous prosthetic joint infection; n.m.: not mentioned.

Due to methodological limitations of the individual study designs, all studies were assigned an a priori ranking of “low quality of evidence” and were finally downgraded to “very low quality of evidence” on the basis of inconsistency and indirectness of evidence (Table 4, see Supplementary data). Because of this very low quality, the risk of bias across studies was not assessed and no meta-analysis was performed.

Discussion

The purpose of this new guideline was to provide recommendations on the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in the prevention of dental HPJI. Based on this systematic review, we conclude that there is no evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis has a positive or negative impact on the incidence of dental HPJI.

However, decisive studies are deemed unfeasible due to the low incidence of dental HPJI and the difficulties of matching HPJI bacteria to the oral flora. Thus, extra literature searches were performed on additional clinical questions that were necessary for the formulation of this guideline (Table 1):

1. Which bacteria are able to cause HPJI, in what numbers are they required, and can prophylactic antibiotic treatment prevent bacteremia?

PJIs were predominantly caused by Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase-negative species. Oral bacteria such as Peptostreptococcus species, Actinomyces species and beta-hemolytic Streptococcus accounted for 10% (Uçkay et al. 2008, Berbari et al. 2010). Animal studies showed that bacteremia could lead to HPJI, but the required number of bacteria (colony forming units (CFU)) was high (> 1,000 CFU/mL) and often resulted in sepsis (Blomgren 1981, Zimmerli et al. 1985, Poultsides et al. 2008).

Based on the risk of subsequent bacteremia, dental procedures are often categorized into “low-risk” (e.g. dental filling, endodontic treatment) and “high-risk” (e.g. dental extraction, periodontal treatment) (Berbari et al. 2010). However, everyday oral activity leads to bacteremia as well; for example, the incidence of bacteremia after mastication and interdental flossing can range from 8% to 51% and from 20% to 58%, respectively (Kotzé 2009). Guntheroth (1984) calculated the 1-month cumulative exposure to bacteremia on the basis of incidence and duration of bacteremia after mastication, tooth brushing, and eventually dental extraction. Out of a total of 5,376 min of bacteremia, only 6 of them were attributable to the extraction. In 296 patients, the duration of bacteremia after tooth brushing or dental extraction was less than 20 min, and the serum concentration did not exceed 104 CFU/mL (Lockhart et al. 2008). The beneficial effect of antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental procedures on the incidence, duration, and extent of a bacteremia remains unclear (Lockhart et al. 2008, Duvall et al. 2013, Young et al. 2014). The eventual clinical relevance will depend on the amount of reduction of these bacteremia parameters, but the literature indicates that there is an unknown risk reduction of an already very low risk of dental HPJI. Moreover, it must be realized that bacteremia is used as a surrogate marker for HPJI, but that there is little evidence that bacteremia truly relates directly to the incidence of dental HPJI.

2. Is there an increased risk of HPJI in the first 2 postoperative years?

In animal experiments, the susceptibility of prostheses to infections is the highest in the first postoperative weeks and decreases rapidly thereafter (Blomgren 1981, Southwood et al. 1985). Since the follow-up of these experiments is short, they do not provide information on long-term susceptibility. In 1993, Osmon et al. presented to the Musculo Skeletal Infection Society (MSIS) an incidence of HPJI in humans of 0.14 per 100 prosthesis years in the first 2 postoperative years, and 0.03 thereafter. These unpublished data were cited by Hanssen et al. (1996), and they have since then been used in the consecutive AAOS guidelines and copied by other authors. Deacon et al. (1996) confirmed that 50% of the HPJI occurred in the first 2 years. More recent studies in humans have not confirmed the supposed higher risk in the first 2 years, but have even found an increased susceptibility in higher joint ages of >2 or >5 years (Hamilton and Jamieson 2008, Uçkay et al. 2009, Berbari et al. 2010, Huotari et al. 2015).

3. Is bleeding during dental treatment an indicator of a higher risk of HPJI?

For a long time, bleeding during dental treatment was considered a marker for the risk of bacteremia, and therefore HPJI. This was first identified—though unsupported by literature—by a panel of experts from the American Heart Association (Dajani et al. 1997, Dinsbach 2012). Indeed, in the event of generalized oral bleeding there was an 8-fold increased risk of bacteremia after tooth brushing in patients with higher dental plaque and calculus scores (Lockhart et al. 2008). Roberts (1999) found that dental manipulations of the gingiva (including mastication) and subsequent alternating positive and negative pressure in the capillaries might lead to bacteremia, but that bleeding itself was not an independent predictor. The positive capillary pressure could possibly even prevent bacteria from entering the circulation.

4. Are prophylactic antibiotics indicated in patients with an impaired immune function?

Patients with an impaired immune system (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, leukopenia) are thought to have an increased risk of HPJI (Uçkay et al. 2009, Olsen et al. 2010, Parvizi and Gehrke 2013). However, in cases involving dental treatments and HPJI, these risk factors have not yet been confirmed (Seymour et al. 2003, Berbari et al. 2010). It is our perception that patients with an impaired immune system will have comparable daily bacteremias analogous to those in healthy individuals, as there is no evidence to suggest that there may be a higher incidence of HPJI in these patients.

5. What are the risks and benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis?

Only rough calculations were possible for the Dutch setting, due to the lack of exact data. For example, we calculated a prevalence of patients with hip and knee prostheses in the Netherlands ranging from 400,000 to 800,000, of which 300,000–600,000 would require antibiotic prophylaxis every year. Internationally reported variables had the same magnitude of uncertainties. These included: HPJI after dental procedures, the repercussions of HPJI (e.g. morbidity, mortality) (Jacobson et al. 1991), the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis (Tsevat et al. 1989), and risks associated with antibiotics (e.g. drug interactions, bacterial resistance) (Macy 2014, NICE 2014). Sendi et al. (2016) confirmed these uncertainties, but they were able to calculate a number needed to treat of 625–1,250 patients. We could not calculate a reliable risk-benefit ratio.

6. Is antibiotic prophylaxis a cost-effective means of preventing HPJI?

Lockhart et al. (2013) concluded that the individual costs of antibiotic prophylaxis in relation to dental procedures were low, but that the potential total costs for American healthcare were high. In 1991, the cost of preventing 1 case of dental HPJI was calculated to be $480,000 per year (Jacobson et al. 1990). Several authors have compared the cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis with penicillin with that of no prophylaxis. They concluded that for the prevention of dental HPJI, the regime of no prophylaxis was more cost-effective (Tsevat et al. 1989, Jacobson et al. 1991, Deacon et al. 1996, Skaar et al. 2015). Antibiotic prophylaxis was only cost-effective when the risk of HPJI after dental treatment was at least 1.2% (Slover et al. 2014), or when one assumes a prophylactic antibiotic effectiveness of 100% in cases with evident oral infections (Gillespie 1990). However, these assumptions are unrealistic since the risk is probably lower and the 2 studies that are relevant did not show a prophylactic effectiveness of 100% (Berbari et al. 2010, Skaar et al. 2011).

7. Is dental screening indicated before and/or after prosthesis placement?

Over the last decades, there has been increasing awareness of the association between oral cavity diseases (e.g. gingivitis, periodontitis) and systemic diseases (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, cardiovascular diseases). Some studies have shown a higher incidence of bacteremia in patients with gingivitis or periodontitis after daily dental activities or dental treatment than in healthy individuals (Forner et al. 2006, Brennan et al. 2007, Tomás et al. 2012). Lockhart et al. (2009) could not confirm these results. It is plausible that the beneficial relation between a healthy oral condition and general health also applies to HPJI (Bartzokas et al. 1994, Lockhart 1996, Seymour et al. 2003, Forner et al. 2006), and in the absence of side effects it seems reasonable to recommend good oral hygiene and regular dental check-ups.

As with endocarditis prophylaxis, radiotherapy, and intensive chemotherapy treatment, some authors have suggested preoperative dental screening prior to orthopedic implant placement. Interestingly, in 1 study chronic oral foci were left untreated in leukemic and autologous stem cell transplantation patients receiving intensive chemotherapy. The authors concluded that these foci did not lead to an increase in infectious complications during intensive chemotherapy (Schuurhuis et al. 2016). It is likely that these cancer patients would be more susceptible to infectious complications than patients who are planned for arthroplasty. Only 1 study reported on the efficacy of dental screenings before arthroplasty. Out of 100 patients, 23 had untreated oral pathologies before arthroplasty. None of them developed PJI within 90 days after implant placement (Barrington and Barrington 2011), but the study may have been too underpowered to be conclusive.

8. Is antibacterial mouthwash indicated before dental treatment?

The antibacterial effect of chlorhexidine could reduce the oral bacterial loads. Several randomized trials have found a significant reduction in the incidence of bacteremia after using antibacterial mouthwash. The authors advised using 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash before dental procedures (Tomás et al. 2007, Ugwumba et al. 2014). On the other hand, other studies have found that chlorhexidine does not reduce the incidence of bacteremia (Lockhart 1996, Duvall et al. 2013). Given the cost implications and the limited but real side effects associated with chlorhexidine mouthwash (e.g. burning sensation, dental/lingual discoloration), more decisive studies are necessary before it can be recommended for routine use.

9. What are the international recommendations on antibiotic prophylaxis and dental HPJI?

Finally, we conducted an analysis of considerations and recommendations from international guidelines and expert opinions on possible indications for antibiotic prophylaxis, dental treatment before arthroplasty, and the need for good oral health in order to prevent HPJI. To be well-informed, we focused particularly on the arguments used in favor of antibiotic prophylaxis. In summary, other guidelines also tend not to recommend antibiotic prophylaxis, but they often include specific risk patients in whom prophylaxis may be justified (Table 5, see Supplementary data).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we are convinced that HPJI can occur, and also after dental procedures. Nonetheless, the “very low level of evidence” found in our systematic literature review suggests that there is no convincing proof in the literature that antibiotic prophylaxis is helpful in preventing dental HPJI. At present, we cannot justify recommending antibiotic prophylaxis in so many prosthesis patients undergoing dental procedures, since the efficacy in preventing or reducing HPJI is not sufficiently evident. This is supported by the answers (A) to the 9 additional questions:

A1:Bacteremia is common after dental treatment, but it is also very frequent in daily life. The effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on bacteremia and dental HPJI remains unclear.

A2:The literature is indecisive regarding the duration of increased susceptibility. It is likely that there is a higher susceptibility to HPJI in the postoperative phase; however, it is unclear whether this phase would last up to 2 years. The recent literature even shows an inverse relationship of there being more HPJI with increasing prosthesis age.

A3:There is no correlation between bleeding during a dental procedure and increased risk of HPJI.

A4:Even in patients with an impaired immune system function, antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment is not indicated for prevention of HPJI.

A5:It was not possible to perform a reliable risk-benefit analysis with the available Dutch data and the international literature.

A6:Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental treatment in patients with a joint arthroplasty is not cost-effective.

A7:Preoperative dental screening before arthroplasty cannot be recommended based on the literature. However, it is advisable to inform patients on the effect of oral health on systemic diseases and on prevention of oral diseases by good daily oral hygiene and regular dental care.

A8:There is insufficient evidence for us to advise using antibacterial mouthwash before dental treatment to prevent HPJI.

A9: Although prevailing opinions and guidelines increasingly tend to advise against the use of prophylactic antibiotics, they often offer exceptions on the basis of inconsistent literature.

The results of this extended literature search have failed to lead to sufficient arguments in favor of antibiotic prophylaxis. They have shown that risk factors such as joint age and bleeding during dental procedures, which are often presented in guidelines as reasons for administering prophylactic antibiotics, appear to be unsupported by the literature and are even illogical from a pathophysiological standpoint. Since there are increasing indications that oral health affects aspects of the general health, we consider regular dental control to be beneficial; this might help to reduce even a minimal risk of dental HPJI, and would have no serious side effects or increase in costs.

In other countries, guidelines also tend not to recommend antibiotic prophylaxis, but often include specific risk patients in whom prophylaxis may be justified. However, daily bacteremia is frequent in both healthy individuals and risk patients, and dental treatment contributes only a small fraction to the overall bacteremia. It is also probable that bacteremia can cause dental HPJI only in septic patients. In septic patients, whether or not they have joint arthroplasty, the medical specialist may prescribe antibiotics for therapeutic rather than prophylactic reasons; this also includes patients with an impaired immune system. In a reverse case scenario involving oral infections (e.g. abscess or apical periodontitis), a dentist could recommend antibiotics for therapeutic rather than prophylactic purposes. Exceptions made in most guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis are unnecessary, and only lead to over-defensive and inconsistent healthcare, where imprudent use of antibiotics has already led to bacterial resistance throughout the world.

The strength of the current guideline is the combination of expertise and consensus from orthopedic surgeons, dental practitioners, and oral maxillofacial surgeons. Especially when evidence is lacking or the research is impossible to perform, expert consensus from the professions concerned is essential for guidelines to receive broad support and, in this case, to discourage clinicians from prescribing prophylactic antibiotics unnecessarily.

In summary, we conclude that: (1) there is no indication that antibiotic prophylaxis should be prescribed before dental procedures in order to prevent HPJI in patients with a joint implant;

(2) nor is there any indication for antibiotic prophylaxis in patients in whom an impaired immune system is supposed or confirmed; and (3) patients should be advised to maintain good oral hygiene and to visit the dentist regularly.

Supplementary data

Tables 2, 4, and 5 are available as supplementary data in the online version of this article, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17453674.2017.1340041

All the authors are members of the joint committee assigned by the Dutch Orthopedic and Dental Societies. WR: analysis and interpretation of literature, drafting of the guideline, and drafting of the present article. GW: head of committee, coordination of analysis and interpretation of the literature, drafting of the guideline, and drafting of the present article. DM, JH, TG, and FR: contributed to data analysis, formulated recommendations, reviewed the guideline, and worked on the manuscript.

We thank Sabrina Muller, Knowledge Institute of Medical Specialists, for her advice and for coordination of the development of this guideline.

No funding was received regarding this study and guideline. There are no competing interests.

Acta thanks Tina Wik and other anonymous reviewers for help with peer review of this article.

Flow diagram showing analysis of the literature. a There were various reasons for exclusion, which are listed in Table 2.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ainscow D A, Denham R A.. The risk of hematogenous infection in total joint replacements. J Bone Joint Surg 1984; 66 (4): 580–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington J W, Barrington T A.. What is the true incidence of dental pathology in the total joint arthroplasty population? J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (6 Suppl): 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartzokas C A, Johnson R, Martin M V, Pearce P K, Saw Y.. Relation between mouth and hematogenous infection in total joint replacements. Br Med J 1994; 309(6953): 506–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berbari E F, Osmon D R, Carr A, Hanssen A D, Baddour L M, Greene D, Kupp L I, Baughan L W, Harmsen W S, Mandrekar J N, Therneau T M, Steckelberg J M, Virk A, Wilson W R.. Dental procedures as risk factors for prosthetic hip or knee infection: a hospital-based prospective case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50 (1): 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgren G. Hematogenous infection of total joint replacement. An experimental study in the rabbit. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1981; 52: 1–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan M T, Kent M L, Fox P C, Norton H J, Lockhart P B.. The impact of oral disease and nonsurgical treatment on bacteremia in children. J Am Dent Assoc 2007; 138 (1): 80–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J L, Scott R D, Long W J.. Late hematogenous infections after total knee arthroplasty: experience with 3013 consecutive total knees. J Knee Surg 2007; 20 (1): 27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dajani A S, Taubert K A, Wilson W, Bolger A F, Bayer A, Ferrieri P, Gewitz M H, Shulman S T, Nouri S, Newburger J W, Hutto C, Pallasch T J, Gage T W, Levison M E, Peter G, Zuccaro G. jr.. Prevention of bacterial endocarditits: recommendations by the American Heart Association. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 25(6): 1448–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale H, Fenstad A M, Hallan G, Havelin L I, Furnes O, Overgaard S, Pedersen A B, Kärrholm J, Garellick G, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Mäkelä K, Engesæter L B.. Increasing risk of prosthetic joint infection after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (5): 449–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon J M, Pagliaro A J, Zelicof S B, Horowitz H W.. Prophylactic use of antibiotics for procedures after total joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78 (11): 1755–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinsbach N A. Antibiotics in dentistry: Bacteremia, antibiotic prophylaxis, and antibiotic misuse. Gen Dent 2012; 60 (3): 200–7; quiz 8-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall N B, Fisher T D, Hensley D, Hancock R H, Vandewalle K S.. The comparative efficacy of 0.12% chlorhexidine and amoxicillin to reduce the incidence and magnitude of bacteremia during third molar extractions: a prospective, blind, randomized clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013; 115 (6): 752–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forner L, Larsen T, Kilian M, Holmstrup P.. Incidence of bacteremia after chewing, tooth brushing and scaling in individuals with periodontal inflammation. J Clin Periodontol 2006; 33 (6): 401–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie W J. Infection in total joint replacement. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1990; 4 (3): 465–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guideline committee. Full database review search. Journal [serial online]. 2015 Date [cited 2016 01/09]. Available from: http://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/antibioticaprofylaxe_bij_gewrichtsprothese/antibioticaprofylaxe_bij_gewrichtsprothese.html#verantwoording. [Google Scholar]

- Guntheroth W G. How important are dental procedures as a cause of infective endocarditis? Am J Cardiol 1984; 54 (7): 797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton H, Jamieson J.. Deep infection in total hip arthroplasty. Can J Surg 2008; 51 (2): 111–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanssen A D, Osmon D R, Nelson C L.. Prevention of deep periprostic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78 (3): 458–71. [Google Scholar]

- Huotari K, Peltola M, Jämsen E.. The incidence of late prosthetic joint infections: a registery based study of 112,708 primary hip and knee replacements. Acta Orthop 2015; 86 (3): 321–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen P L, Murray W.. Prophylactic coverage of dental patients with artificial joints: a retrospective analysis of thirty-three infections in hip prostheses. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1980; 50 (2): 130–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J J, Schweitzer S, DePorter D J, Lee J J.. Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with joint prostheses? A decision analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 1990; 6 (4): 569–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson J J, Schweitzer S O, Kowalski C J.. Chemoprophylaxis of prosthetic joint patients during dental treatment. A decision-utility analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1991; 72 (2): 167–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotzé M J. Prosthetic joint infection, dental treatment and antibiotic prophylaxis. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2009; 1 (1): e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPorte D M, Waldman B J, Mont M A, Hungerford D S.. Infections associated with dental procedures in total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1999; 81 (1): 56–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart P B. An analysis of bacteremias during dental extractions. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of chlorhexidine. Arch Intern Med 1996; 156 (5): 513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart P B, Brennan M T, Sasser H C, Fox P C, Paster B J, Bahrani-Mougeot F K.. Bacteremia associated with toothbrushing and dental extraction. Circulation 2008; 117 (24): 3118–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart P B, Brennan M T, Thornhill M, Michalowicz B S, Noll J, Bahrani-Mougeeot F K, Sasser H.. Poor oral hygiene as a risk factor for infective endocarditis-related bacteremia. J Am Dent Assoc 2009; 140 (10): 1238–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart P B, Blizzard J, Maslow A L, Brennan M T, Sasser H, Carew J.. Drug cost implications for antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2013; 115 (3): 345–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macy E. Penicillin and beta-lactam allergy: Epidemiology and diagnosis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2014; 14 (11): 476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE. Drug allergy: diagnosis and management of drug allergy in adults, children and young people. https://wwwniceorguk/guidance/cg183/resources/guidance-drug-allergy-diagnosis-and-management-of-drug-allergy-in-adults-children-and-young-people-pdf (access 1-04-2015) 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen I, Snorrason F, Lingaas E.. Should patients with hip joint prosthesis receive antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment? J Oral Microbiol 2010; 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvizi J, Gehrke T. Proceedings of the International Consensus Meeting on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Data Trace Publishing Company, Maryland, USA, Maryland 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Poultsides L A, Papatheodorou L K, Karachalios T S, Khaldi L, Maniatis A, Petinaki E, Malizos K N.. Novel model for studying hematogenous infection in an experimental setting of implant-related infection by a community-acquired Methicillin-resistent S. aureus strain. J Orthop Res 2008; 26(10): 1355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts G J. Dentists are innocent! “Everyday” bacteremia is the real culprit: a review and assessment of the evidence that dental surgical procedures are a principal cause of bacterial endocarditis in children. Pediatr Cardiol 1999; 20 (3): 317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuurhuis J M, Span L F, Stokman M A, van Winkelhoff A J, Vissink A, Spijkervet F K.. Effect of leaving chronic oral foci untreated on infectious complications during intensive chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 2016; 114 (9): 972–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sendi P, Uçkay I, Suva D, Vogt M, O. B, M. C. . Antibiotic prophylaxis during dental procedures in patients with prosthetic joints. J Bone Joint Infect 2016; 1: 42–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour R A, Whitworth J M, Martin M.. Antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with joint prostheses - still a dilemma for dental practitioners. Br Dent J 2003; 194 (12): 649–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaar D D, O’Connor H, Hodges J S, Michalowicz B S.. Dental procedures and subsequent prosthetic joint infections: findings from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. J Am Dent Assoc 2011; 142 (12): 1343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaar D D, Park T, Swiontkowski M F, Kuntz K M.. Cost-effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis for dental patients with prosthetic joints: Comparisons of antibiotic regimens for patients with total hip arthroplasty. J Am Dent Assoc 2015; 146 (11): 830–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slover J D, Philips M S, Iorio R, Bosco J.. Is routine antibiotic prophylaxis cost effective for total joint replacement patients? J Arthroplasty 2014; 30 (4): 543–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwood R, Rice J, McDonald P, Hakendorf P, Rozenbilds M.. Infection in experimental hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg 1985; 67-B (2): 229–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan J, Dowsey M, Babazadeh S, Mandaleson A, Choong P F.. Significance of sentinel infective events in haematogenous prosthetic knee infections. ANZ J Surg 2011; 81 (1-2): 40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swierstra B A, Vervest A M, Walenkamp G H, Schreurs B W, Spierings P T, Heyligers I C, van Susante J L, Ettema H B, Jansen M J, Hennis P J, de Vries J, Muller-Ploeger S B, Pols M A.. Dutch guideline on total hip prosthesis. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (5): 567–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás I, Alvarez M, Thomás M, Medina J, Otero J L, Diz P.. Effect of a Chlorhexidine mouthwash on the risk of postextraction bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007; 28 (5): 577–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás I, Diz P, Tobías A, Scully C, Donos N.. Periodontal health status and bacteraemia from daily oral activities: systematic review/meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2012; 39 (3): 213–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsevat J, Durand-Zaleski I, Pauker S G.. Cost-effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures in patients with artificial joints. Am J Public Health 1989; 79 (6): 739–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uçkay I, Pittet D, Bernard L, Lew D, Perrier A, Peter R.. Antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive dental procedures in patients with arthroplasties of the hip and knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90 (7): 833–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uçkay I, Lübbeke A, Emonet S, Tovmirzaeva L, Stern R, Ferry T, Assal M, Bernard L, Lew D, Hoffmeyer P.. Low incidence of haematogenous seeding to total hip and knee prostheses in patients with remote infections. J Infect 2009; 59 (5): 337–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugwumba C U, Adeyemo W L, Odeniyi O M, Arotiba G T, Ogunsola F T.. Preoperative administration of 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthrinse reduces the risk of bacteremia asscociated with intra-alveolar tooth extraction. J Cranio Maxillo Facial Surg 2014; 42 (8): 1783–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman B J, Mont M A, Hungerford D S.. Total knee arthroplasty infections associated with dental procedures. Clin Orthop Rel Res 1997; (343): 164–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walenkamp G H. [Current guidelines for antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with a joint prosthesis are inadequate]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor tandheelkunde 2013; 120 (11): 589–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watters W 3rd, Rethman M P, Hanson N B, Abt E, Anderson P A, Carroll K C, Futrell H C, Garvin K, Glenn S O, Hellstein J, Hewlett A, Kolessar D, Moucha C, O’Donnell R J, O’Toole J E, Osmon D R, Evans R P, Rinella A, Steinberg M J, Goldberg M, Ristic H, Boyer K, Sluka P, Martin W R 3rd, Cummins D S, Song S, Woznica A, Gross L.. Prevention of Orthopaedic Implant Infection in Patients Undergoing Dental Procedures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013; 21 (3): 180–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young H, Hirsh J, Hammerberg E M, Price C S.. Dental disease and periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014; 96 (2): 162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Sendi P.. Antibiotics for prevention of periprosthetic joint infection following dentistry: time to focus on data. Clin Infect Dis 2010; 50 (1): 17–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerli W, Zak O, Vosbeck K.. Experimental hematogenous infecteion of subcutaneously implanted foreign bodies. Scand J Infect Dis 1985; 17 (3): 303–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.