Case: Severe Fibrosis and Emphysema in Combination with Pulmonary Hypertension

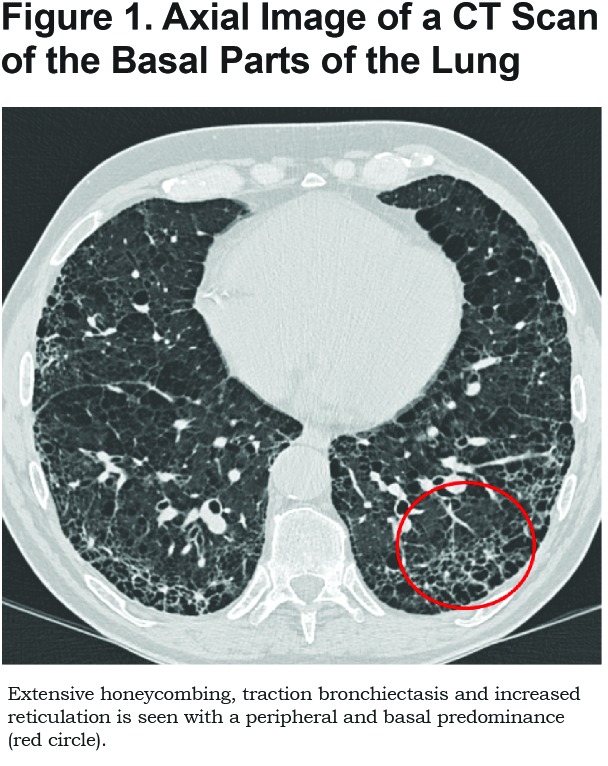

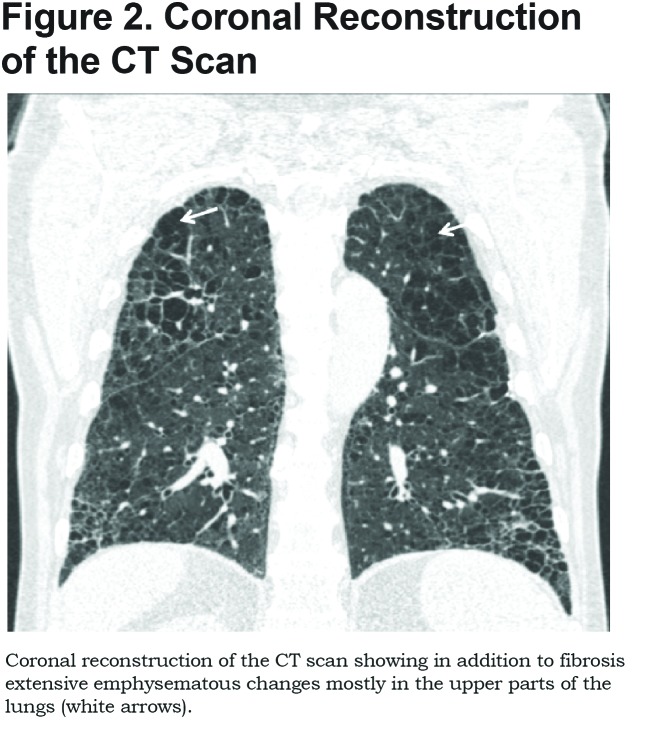

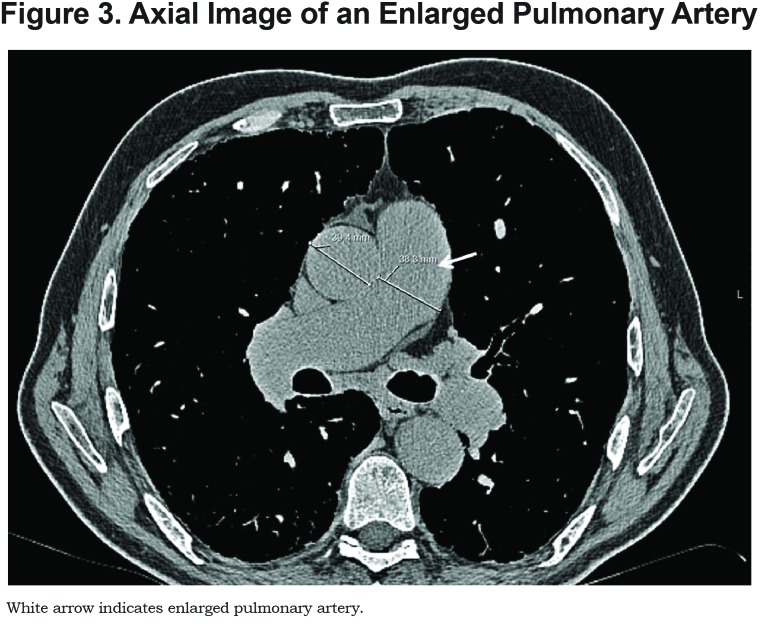

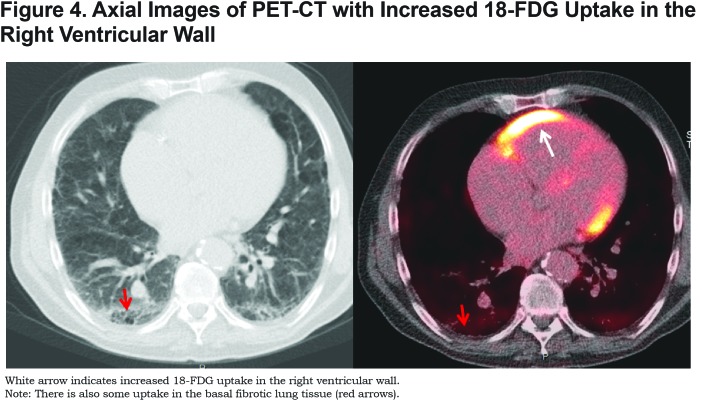

A 62-year old male was referred to our hospital for lung transplantation because of end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). His medical history did not show any other relevant comorbidity. He had quit smoking 1 year previously with a 50 pack year history. Respiratory symptoms mainly consisted of dyspnea on exertion and occasional coughing. His resting arterial blood gas revealed a hypoxia of 58mmHg (normal reference values: 70-100 mmHg). His lung function showed a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of 3.34L (83% of predicted value), vital capacity of 5.54L (106% of predicted value), FEV1/FVC (forced vital capacity) was 58%, and a very low diffusion capacity of 15% of predicted. A 6-minute walking test was performed in which he could walk 181 meters with a saturation drop from 90% at the start to 75% at the end of the test without using extra oxygen during the test. Computed tomography (CT) of the lungs and an 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT were routinely performed as part of the lung transplant screening proceedure. Figure 1 shows an axial image of the CT scan of the basal parts of the lung. Extensive honeycombing, traction bronchiectasis and increased reticulation are seen with a peripheral and basal predominance fitting an usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern. Figure 2 shows a coronal reconstruction of the CT scan showing, in addition to fibrosis, extensive emphysematous changes. Centrilobular and paraseptal emphysema is predominantly found in the upper parts of the lung. A diagnosis of combined pulmonary emphysema and fibrosis (CPFE) was made. The pulmonary artery was enlarged on CT (Figure 3) with a diameter of 38mm suggestive of pulmonary hypertension (wherein a value of >25mm is suggestive of the presence of pulmonary hypertension). At right-heart catheterization, the mean pulmonary artery pressure was raised (higher than 25mmHg as cut off value consistent with the presence of pulmonary hypertension). Figure 4 shows the PET-CT with increased 18-FDG uptake in the right ventricular wall. There is also some uptake in the basal fibrotic lung tissue.

Discussion

In 2005 the term combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE) was coined to describe individuals with a distinct pattern of CT-defined fibrosis and emphysematous changes, a high prevalence of pulmonary hypertension and poor survival.1 The majority of CPFE patients are male and almost all are current or former smokers.2 Interestingly, already in 1974 the combination of pulmonary fibrosis and severe emphysema was described at microscopy images.3

Imaging findings include upper lobe predominant emphysema in combination with lower lobe predominant interstitial fibrotic lung changes. Emphysema is usually of the paraseptal type, but is often present in combination with centrilobular and bullous emphysema.2 As in this case, the interstitial changes mostly follow a UIP pattern (i.e., tractionbronchiectasis, honeycombing and increased reticulation with a basal peripheral predominance), but other patterns have also been described such as non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD) and desquamative interstitial pneumonia with extensive fibrosis (DIP).2,4

Pulmonary hypertension is common in CPFE and occurs in almost half of the patients.4,5 By comparison, for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), pulmonary hypertension occurs in ~20% of individuals. CPFE patients with pulmonary hypertension have a worse prognosis and outcome compared to IPF or emphysema alone and 1-year survival rates of 60% have been reported for CPFE if pulmonary hypertension is present. Further progress of the disease, with severe disturbance of the diffusion capacity, induces hypoxemia especially during exercise, which is similar to what was found in our case. This leads to increased pulmonary hypertension with rapid deterioration and at the end, right ventricular enlargement and failure. Although pulmonary hypertension is formally diagnosed with right heart catheterization, signs of pulmonary hypertension are frequently seen on the chest CT. These signs include pulmonary arterial dilatation and right ventricular enlargement. On a PET-CT, high 18-FDG uptake in the right ventricular wall, as illustrated in this case, might also be a sign of pulmonary hypertension.6

Our case illustrated the typical imaging pattern of CPFE and also illustrated that pulmonary hypertension is often present in CPFE.

Abbreviations

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FEV1; forced vital capacity, FVC; computed tomography, CT; 18-fluorodeoxyglucose, 18-FDG; positron emission tomography, PET; usual interstitial pneumonia, UIP; combined pulmonary emphysema and fibrosis, CPFE; non-specific interstitial pneumonia, NSIP; respiratory bronchiolitis-associated interstitial lung disease, RB-ILD; desquamative interstitial pneumonia, DIP; idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, IPF

References

- 1. Al-Kassimi FA,Alfaleh HF,Alshamiri MQ,et al. Prediction of pulmonary hypertension in patients with or without interstitial lung disease: reliability of CT findings. Radiology. 2011;260(3):875-883. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.11103532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Auerbach O,Garfinkel L,Hammond EC. Relation of smoking and age to findings in lung parenchyma: a microscopic study. Chest. 1974;65(1):29-35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.65.1.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cottin V,Nunes H,Brillet PY,et al. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: a distinct underrecognised entity. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(4):586-593. doi: https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00021005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin H,Jiang S. Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema (CPFE): an entity different from emphysema or pulmonary fibrosis alone. J Thorac Dis. 7(4):767-779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mejia M,Carrillo G,Rojas-Serrano J,et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema: decreased survival associated with severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest. 2009;136:10-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-2306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. de Keizer B,Scholtens AM,van Kimmenade RR,de Jong PA. High FDG uptake in the right ventricular myocardium of a pulmonary hypertension patient. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(18):1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]